95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Hum. Neurosci. , 16 July 2021

Sec. Brain Imaging and Stimulation

Volume 15 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2021.711688

This article is part of the Research Topic Mapping Psychopathology with MRI and Connectivity Analysis View all 12 articles

A commentary has been posted on this article:

Commentary: Targeting the MRI-mapped psychopathology of major psychiatric disorders with neurostimulation

Objectives: To investigate changes in functional connectivity between the vermis and cerebral regions in the resting state among subjects with bipolar disorder (BD).

Methods: Thirty participants with BD and 28 healthy controls (HC) underwent the resting state functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). Resting-state functional connectivity (rsFC) of the anterior and posterior vermis was examined. For each participant, rsFC maps of the anterior and posterior vermis were computed and compared across the two groups.

Results: rsFC between the whole vermis and ventral prefrontal cortex (VPFC) was significantly lower in the BD groups compared to the HC group, and rsFC between the anterior vermis and the middle cingulate cortex was likewise significantly decreased in the BD group.

Limitations: 83.3% of the BD participants were taking medication at the time of the study. Our findings may in part be attributed to treatment differences because we did not examine the effects of medication on rsFC. Further, the mixed BD subtypes in our current study may have confounding effects influencing the results.

Conclusions: These rsFC differences of vermis-VPFC between groups may contribute to the BD mood regulation.

Bipolar disorder (BD) is a severe psychiatric illness characterized by recurrent disturbances in sleep, behavior, perception, cognition, and mood regulation (Goodwin and Geddes, 2007). The cerebellum has long been regarded as a brain structure involved in motor systems (anterior lobe and lobule VI), there is growing contemporary evidence that it influences cognition (posterior lobe) and mood regulation (the vermis; Schutter and Van Honk, 2005; Schmahmann, 2019). The cerebellum’s involvement in mood regulation is consistent with earlier clinical studies that suggested the cerebellum functioned as an emotional pacemaker (Heath, 1977; Heath et al., 1979), as well as contemporary evidence that implicates the cerebellar vermis and fastigial nucleus as the limbic cerebellum (Schmahmann, 2001, 2004). The fastigial nucleus, one of the deep cerebellar nuclei, mediates the connection between the vermis and the cerebellar inferior peduncle and connects to the reticular formation and the limbic system through the inferior peduncle (Schmahmann, 2004). The connections between the vermis and both the reticular and limbic system imply that the vermis plays an important role in the regulation of affect (Stoodley and Schmahmann, 2009; Moulton et al., 2011). Some studies found that multi-episode BD patients have smaller vermal V2 and V3 areas via structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) compared to first-episode patients (DelBello et al., 1999; Mills et al., 2005). These data suggested that the vermis might therefore be subject to atrophy during BD spells. Moreover, mood disorders such as BD have been linked to impairments in anterior limbic brain structures, wherein the cerebellum may modulate mood (Strakowski et al., 2002).

Recent studies of spontaneous resting-state functional connectivity (rsFC) have focused on the BD brain network abnormalities such as abnormal rsFC in the frontotemporal system (Chepenik et al., 2010; Dickstein et al., 2010) and corticolimbic system (Anand et al., 2009). rsFC between the cerebellum and the whole brain can also be defined as the temporal dependency of their neural activation patterns by their coherence in spontaneous fluctuations in resting-state functional MRI (fMRI) signals (Buckner and Vincent, 2007). One recent MRI study found that the cerebellum and basal ganglia are closely correlated with mood states in BD, representing the altered metabolic activity of BD patients’ cerebellum (Johnson et al., 2018). Another resting-state fMRI study also found altered cerebellum-brain region connectivity in unmedicated BD (Chen et al., 2019).

In this study, we utilized a region-of-interest (ROI) based approach to examine rsFC in individuals with BD and healthy control (HC) participants. We selected the vermis as ROI and hypothesized that the BD group would show altered rsFC between vermis and cerebral regions which are involved in mood regulation compared to the HC group.

All BD participants were diagnosed using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (Bell, 1994) and fulfilled DSM-IV criteria for BD in this study. Using DSM-IV criteria, psychologists of our working group recruited all BD patients from the outpatient center of the First Hospital of China Medical University and Mental Health Center of Shenyang between June 2010 and August 2018. Enrolled patients were consistently aged 18–50 years right-handed, and exhibited neither neurological illness nor head trauma involving loss of consciousness exceeding 5 min, nor any major physical disorder or contraindication for fMRI scanning. Psychologists systematically evaluated the presence or absence of Axis I Disorder for the recruited patients and assessed patients’ mood state at scanning according to the DSM-IV Structured Clinical Interview. Psychological examinations of all HCs recruited from the local community were normal, these examinations confirmed no personal histories of mental illness, mood, psychotic, anxiety, or substance misuse disorders in their first-degree family members. Thirty BD patients and 28 HCs were ultimately included in the study population (matched by age and gender, p > 0.05). Symptoms were assessed using the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) and the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS). Twenty-five (83.3%) of the BD participants were taking medication at the time of scanning. Some of the participants in this study also participated in our previous study (Xu et al., 2014). Their behavioral assessment was made by XJ. All participants were approved by the ethics committee of the first hospital of China Medical University and provided a signed, written informed consent.

At the time of scanning, five (16.7%) participants with BD met DSM-IV criteria for a depressive episode and six (20.0%) for a manic/mixed or hypomanic episode, whereas the remaining 19 (63.3%) were euthymic. Detailed demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1.

All fMRI scans were performed using a 3.0-T GE Signa System (GE Signa, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA) in the Department of Radiology, the First Hospital of China Medical University. The clinician asked the patients to remove any metal jewelry or accessories that might interfere with the machine and briefly introduced the procedure of MRI scanning to reduce the anxiety of patients. Foam pads were provided to reduce head motion and scanner noise when patients were lying down. Technician set the parameter of a 3D-SPGR sequence to acquire three-dimensional T1-weighted images in a sagittal orientation with the repetition time (TR) = 7.1 ms, echo time (TE) = 3.2 ms, field of view (FOV) = 24 cm×24 cm, flip angle = 15°, matrix = 256 × 256, slice thickness = 1.8 mm, no gap. The fMRI scanning was performed in darkness, and an observer stood to one side to ensure the patients kept their eyes closed, relaxing, and moving as little as possible. The slices of functional images were positioned approximately along the AC-PC line using a gradient echo-planar imaging (EPI): TR = 2,000 ms, TE = 30 ms, FOV = 24 cm × 24 cm, flip angle = 90°, matrix = 64 × 64, slice thickness = 3 mm, no gap, slices = 35. For each participant, the fMRI scanning lasted 7 min. Image preprocessing was carried out using SPM81 and DPABI (Yan et al., 2016). Preprocessing consisted of slice-time correction, motion correction, spatial normalization, and spatial smoothing full width at half maximum (FWHM = 6 mm). Movement parameters were extracted out by SPM8 for each participant, which can exclude the data sets with more than 2 mm maximum translation along the x, y, or z axes, allowing 2° of maximum rotation about three axes among each image. Further preprocessing consisted of removing linear drift through linear regression and temporal band-pass filtering (0.01–0.08 Hz) to reduce the effects of low-frequency drifts and physiological high-frequency noise.

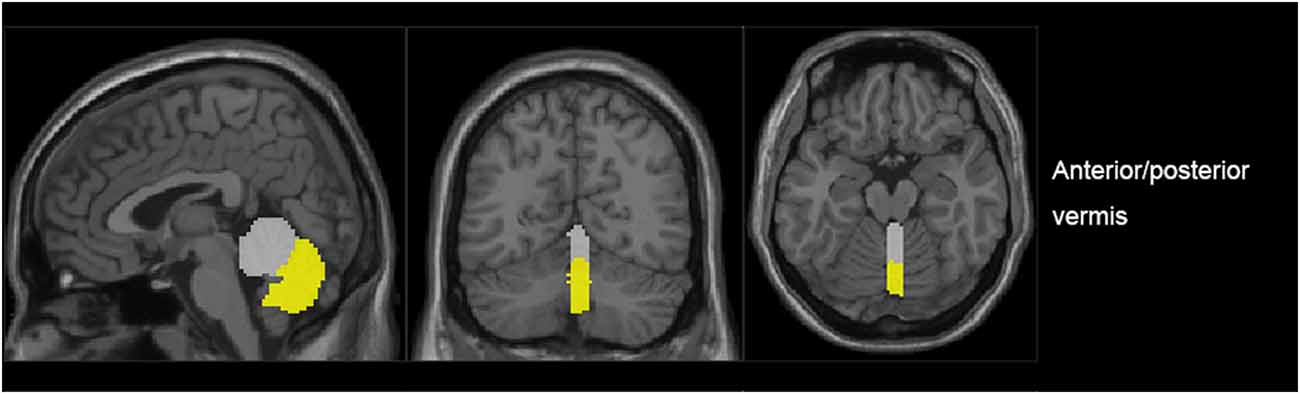

The vermis was divided into anterior vermis (vermis I-V) and posterior vermis (vermis VI-IX) by AAL (Anatomical automatic labelling; Pfefferbaum et al., 2011; Figure 1). For each ROI, the blood oxygen level dependence (BOLD) time series of the voxels within the ROI were averaged to generate the reference time series.

Figure 1. The generated anterior (gray) and posterior (yellow) regions of interest (ROIs) in a representative subject.

A whole-brain mask was created by taking the intersections of the normalized T1-weighted high-resolution images of all participants, which were stripped using the software BrainSuite22.

A regression generalized linear model (GLM) was created for each participant, including a time series regressor for one of the two vermal subregions, and applied to each of eight nuisance covariates (white matter, cerebrospinal fluid, and six motion parameters). Correlation analysis was performed in a voxel-wise manner between the seed ROIs and the whole brain using DPABI. The correlation coefficients were then transformed to z-values using the Fisher r-to-z transformation for more conforming to Gaussian distribution. A one-sample t-test model was used to delineate the functional connectivity of each vermis ROI in the first-level analysis. Direct comparisons were conducted to identify differences in functional connectivity between BD vs. HC in the second-level random-effects analysis.

Statistical significance was determined by a corrected P < 0.05 that combined individual voxel p(uncorrected) < 0.01 with GRF (Gaussian random field) correction for cluster-level inference of p < 0.05 (Bousse et al., 2012). Additional exploratory analyses (ANCOVA) were performed for effects of medications (overall presence or absence of medication) on the regions that showed significant differences between the HC and BD groups. Finally, significant correlations between HDRS, YMRS in the BD group, and the transformed z-scores showing significant group differences were performed using exploratory correlation analyses to identify the relationship between the symptom severity and the strength of connectivity. A two-tailed p level of 0.05 was used as the criterion of statistical significance.

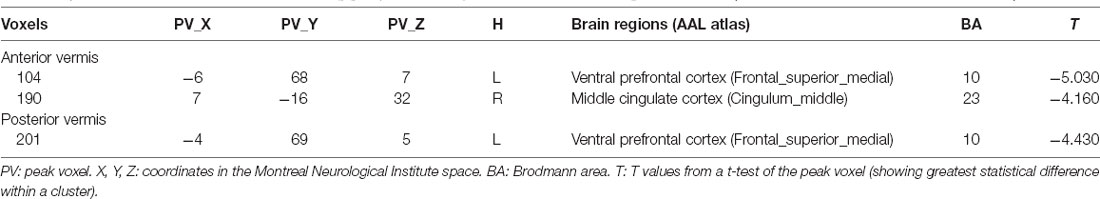

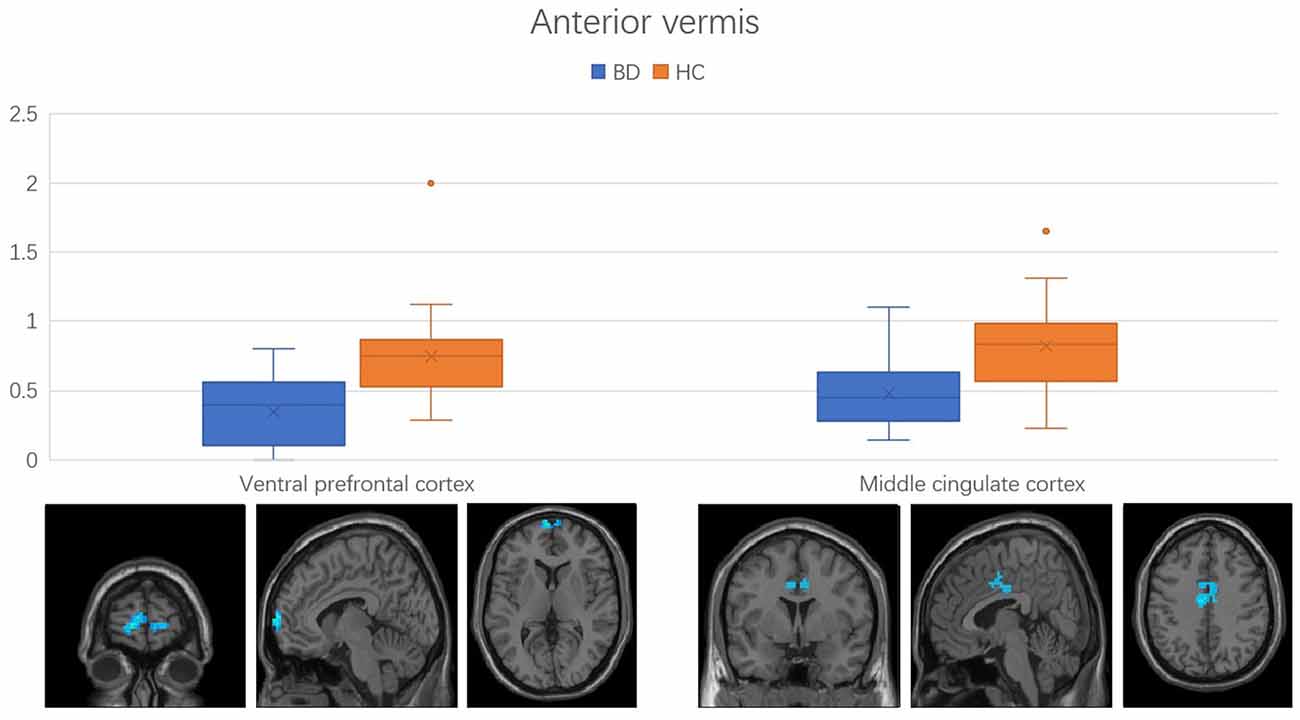

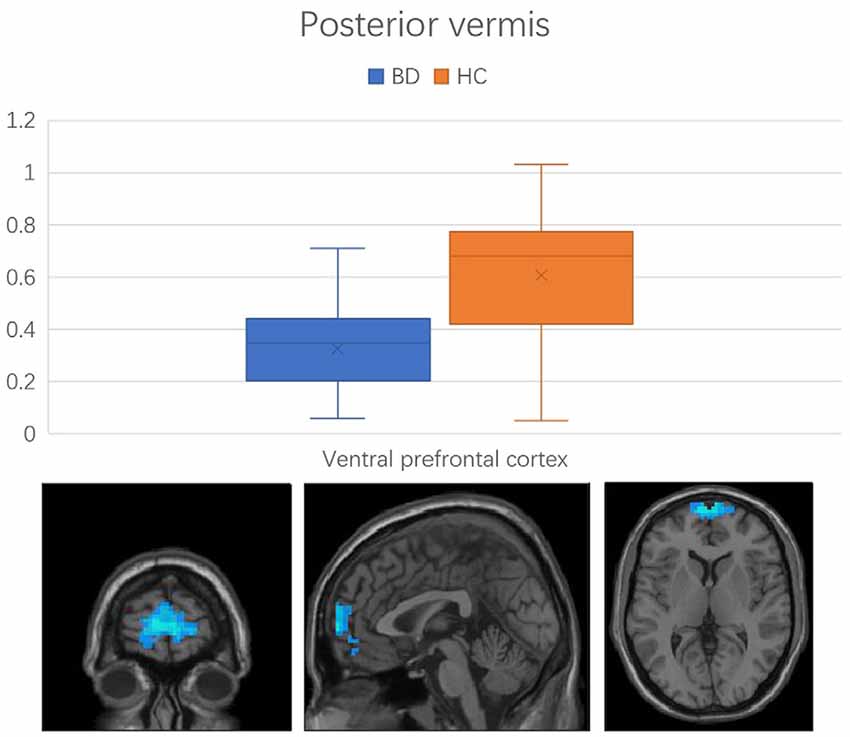

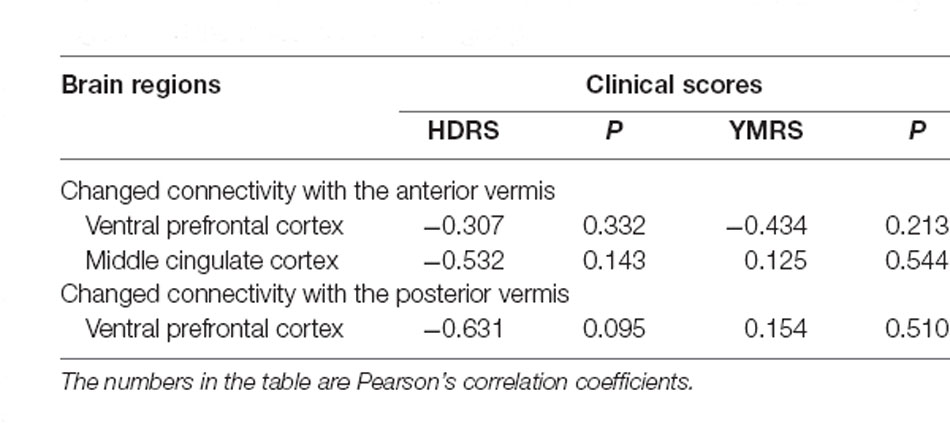

Regions with changed vermal connectivity between the BD and HC groups are shown in Table 2. Compared to the HC group, significant differences in rsFC were observed between the anterior vermis and brain regions that included ventral prefrontal gyrus (VPFC; BA 10) and middle cingulate cortex (BA 24; Figure 2), while the posterior vermis showed significant differences in rsFC with VPFC (BA 10) in the BD group (Figure 3). In addition, there were no significant effects of medication on FC values in the regions that differed between the HC and BD groups (ANCOVA test, p > 0.05). Finally, correlation analysis was performed between the connectivity coefficient within clusters showing significant group differences and behavioral measures as assessed by HDRS, YMRS in the BD group. Analyses of correlations did not show any significant effects between functional connectivity and clinical scores (Table 3).

Table 2. Detailed information for clusters showing group connectivity differences in BD at the given threshold (cluster size > 297 mm3, and P < 0.00014).

Figure 2. Functional connectivity between anterior vermis and ventral prefrontal cortex, middle cingulate cortex in the comparison between bipolar disorder (BD) and healthy controls (HC) groups. Error bars represent the standard deviation of Z values at the peak voxel. BD, bipolar disorder; HC, healthy control.

Figure 3. Functional connectivity between the posterior vermis and ventral prefrontal cortex in the comparison between BD and HC groups. Error bars represent the standard deviation of Z values at the peak voxel. BD, bipolar disorder; HC, healthy control.

Table 3. The correlation between the strength of these changed connectivity regions and the clinical scores in BD group.

The current study examined vermal connectivity in BD patients. We discovered that two cerebral regions (VPFC and middle cingulate cortex) showed decreasing connectivity with the vermis. Previous studies show that these two brain regions exhibited changed neural activity or disturbed connectivity with other cerebral regions. We initially found the connectivity pattern between vermis and these two cerebral regions was similarly disturbed in BD patients.

Previous studies proposed that the vermis can be considered as the “limbic cerebellum,” based on its regional connections with limbic structures (Schmahmann, 2001, 2004). Patients with the cerebellar cognitive affective syndrome can show emotional lability, inappropriate laughing or crying, and changes in affection, suggesting that these cerebellar-limbic connections are involved in the modulation of emotional processing (Levisohn et al., 2000). What’s more, malformations of the posterior vermis have been confirmed to be associated with emotional symptoms (Tavano et al., 2007). These studies implicated the cerebellar vermis, especially the posterior vermis play important roles in mood regulation. Interestingly, the VPFC has now also been shown to play an important role in emotion processes (Kringelbach, 2005). Many fMRI studies have found abnormal activation of the VPFC in BD during tasks (Blumberg et al., 2003; Elliott et al., 2004; Lawrence et al., 2004; Strakowski et al., 2004; Malhi et al., 2005). Abnormal VPFC neural activity and disturbed VPFC-amygdala rsFC were also observed by resting-state studies (Liu et al., 2014; Xu et al., 2014). Trait abnormalities of VPFC in BD are further supported by postmortem histopathological findings such as decreased glial density and reductions in the density of both neurons and glia (Ongur et al., 1998; Rajkowska, 2000, 2002). In our study, the entire vermis showed changed rsFC patterns with the VPFC, establishing that the decreased rsFC of vermis-VPFC plays an important role in the regulation of mood linked to the core psychopathology of BD.

Another changed connectivity region of the anterior vermis, which belongs to the anterior lobe of the cerebellum, is the middle cingulate cortex (BA 24). The function of the anterior cerebellar lobe is mainly associated with motor control (Stoodley and Schmahmann, 2009). The middle cingulate cortex area is the midsection of the cingulate gyrus in its anterior-posterior axis and appears to be involved in both motor control and cognitive tasks such as response selection, error detection, competition monitoring, and working memory (Torta and Cauda, 2011). Previous studies have consistently reported aberrant motor control presentation in BD (Manschreck et al., 2004; Krebs et al., 2010; Deveney et al., 2012; Weathers et al., 2012). Our findings combined with previous studies suggest that the anterior vermis may be involved in the motor control of BD patients, which should be further validated by future studies.

There are several limitations to this study. First, 83.3% of the BD participants were taking medication at the time of the study. Although we did not find significant effects of medication on FC values in this study, our findings may in part be attributed to treatment differences. Second, confounding effects may influence the result of mixed BD subtypes in our current study; future studies that compare subtypes in BD would likely contribute to our understanding of the underlying mechanisms of BD. Thirdly, the sample size is modest. Finally, correlation analyses did not reveal significant relationships between rsFC and symptom measures in BD. In this study, only the HDRS and YMRS symptom measurements were assessed in the BD group. Future studies should include more comprehensive symptom measurements to enhance our understanding of the relationship between symptom severity and functional connectivity as well as state vs. trait-related abnormalities in BD. Because the majority of BD participants in this study were in remitted states, our findings more likely reflect trait-related differences between BD and HC.

In summary, BD patients showed decreased rsFC of vermis and VPFC as compared to the HC group. This resting-state fMRI study suggests that the abnormal rsFC of vermis-VPFC may contribute to mood regulation in BD patients. Further work focusing on this field may contribute to our understanding of BD neuropathphysiology.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by The First Hospital of China Medical University. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Conception and design: GF and WS. Development of methodology: HLiu. Data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation: YT and XJ. Writing, review, and/or revision of the manuscript: HLiu, HLi, and RY. Study supervision: YT, GF, and WS. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This work was supported by National Key R&D Program of China (Grant #2018YFC1311600 and 2016YFC1306900 to YT), Liaoning Revitalization Talents Program (Grant #XLYC1808036 to YT), Science and Technology Plan Program of Liaoning Province (2015225018 to YT), National Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars (81725005 to Fei Wang), Liaoning Education Foundation (Pandeng Scholar to Fei Wang), Innovation Team Support Plan of Higher Education of Liaoning Province (LT2017007 to Fei Wang), Major Special Construction Plan of China Medical University (3110117059 and 3110118055 to Fei Wang), Joint Fund of National Natural Science Foundation of China (U1808204 to Feng Wu), and Natural Science Foundation of Liaoning Province (2019-MS-05 to Feng Wu).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

BD, Bipolar disorder; MRI, Magnetic resonance imaging; rsFC, Resting-state functional connectivity; fMRI, functional MRI; ROI, Region of interest; HC, Healthy control; HDRS, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; YMRS, Young Mania Rating Scale; BOLD, Blood oxygen level dependence; GLM, Generalized linear model; FWHM, Full width at half maximum; VPFC, Ventral prefrontal gyrus.

Anand, A., Li, Y., Wang, Y., Lowe, M. J., and Dzemidzic, M. (2009). Resting state corticolimbic connectivity abnormalities in unmedicated bipolar disorder and unipolar depression. Psychiatry Res. 171, 189–198. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2008.03.012

Bell, C. C. (1994). DSM IV: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. JAMA 272, 828–829. doi: 10.1001/jama.1994.03520100096046

Blumberg, H. P., Martin, A., Kaufman, J., Leung, H. C., Skudlarski, P., Lacadie, C., et al. (2003). Frontostriatal abnormalities in adolescents with bipolar disorder: preliminary observations from functional MRI. Am. J. Psychiatry 160, 1345–1347. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.7.1345

Bousse, A., Pedemonte, S., Thomas, B. A., Erlandsson, K., Ourselin, S., Arridge, S., et al. (2012). Markov random field and Gaussian mixture for segmented MRI-based partial volume correction in PET. Phys. Med. Biol. 57, 6681–6705. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/57/20/6681

Buckner, R. L., and Vincent, J. L. (2007). Unrest at rest: default activity and spontaneous network correlations. Neuroimage 37, 1091–1096. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.01.010

Chen, G., Zhao, L., Jia, Y., Zhong, S., Chen, F., Luo, X., et al. (2019). Abnormal cerebellum-DMN regions connectivity in unmedicated bipolar II disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 243, 441–447. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.09.076

Chepenik, L. G., Raffo, M., Hampson, M., Lacadie, C., Wang, F., Jones, M. M., et al. (2010). Functional connectivity between ventral prefrontal cortex and amygdala at low frequency in the resting state in bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Res. 182, 207–210. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2010.04.002

DelBello, M. P., Strakowski, S. M., Zimmerman, M. E., Hawkins, J. M., and Sax, K. W. (1999). MRI analysis of the cerebellum in bipolar disorder: a pilot study. Neuropsychopharmacology 21, 63–68. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00026-3

Deveney, C. M., Connolly, M. E., Jenkins, S. E., Kim, P., Fromm, S. J., Brotman, M. A., et al. (2012). Striatal dysfunction during failed motor inhibition in children at risk for bipolar disorder. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 38, 127–133. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2012.02.014

Dickstein, D. P., Gorrostieta, C., Ombao, H., Goldberg, L. D., Brazel, A. C., Gable, C. J., et al. (2010). Fronto-temporal spontaneous resting state functional connectivity in pediatric bipolar disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 68, 839–846. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.06.029

Elliott, R., Ogilvie, A., Rubinsztein, J. S., Calderon, G., Dolan, R. J., and Sahakian, B. J. (2004). Abnormal ventral frontal response during performance of an affective go/no go task in patients with mania. Biol. Psychiatry 55, 1163–1170. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.03.007

Goodwin, G. M., and Geddes, J. R. (2007). What is the heartland of psychiatry? Br. J. Psychiatry 191, 189–191. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.036343

Heath, R. G. (1977). Modulation of emotion with a brain pacemaker: treatment for intractable psychiatric illness. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 165, 300–317.

Heath, R. G., Franklin, D. E., and Shraberg, D. (1979). Gross pathology of the cerebellum in patients diagnosed and treated as functional psychiatric disorders. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 167, 585–592. doi: 10.1097/00005053-197910000-00001

Johnson, C. P., Christensen, G. E., Fiedorowicz, J. G., Mani, M., Shaffer, J. J., Jr., Magnotta, V. A., et al. (2018). Alterations of the cerebellum and basal ganglia in bipolar disorder mood states detected by quantitative T1ρ mapping. Bipolar Disord. 20, 381–390. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12581

Krebs, M. O., Bourdel, M. C., Cherif, Z. R., Bouhours, P., Loo, H., Poirier, M. F., et al. (2010). Deficit of inhibition motor control in untreated patients with schizophrenia: further support from visually guided saccade paradigms. Psychiatry Res. 179, 279–284. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.07.008

Kringelbach, M. L. (2005). The human orbitofrontal cortex: linking reward to hedonic experience. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 6, 691–702. doi: 10.1038/nrn1747

Lawrence, N. S., Williams, A. M., Surguladze, S., Giampietro, V., Brammer, M. J., Andrew, C., et al. (2004). Subcortical and ventral prefrontal cortical neural responses to facial expressions distinguish patients with bipolar disorder and major depression. Biol. Psychiatry 55, 578–587. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2003.11.017

Levisohn, L., Cronin-Golomb, A., and Schmahmann, J. D. (2000). Neuropsychological consequences of cerebellar tumour resection in children: cerebellar cognitive affective syndrome in a paediatric population. Brain 123, 1041–1050. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.5.1041

Liu, H., Tang, Y., Womer, F., Fan, G., Lu, T., Driesen, N., et al. (2014). Differentiating patterns of amygdala-frontal functional connectivity in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Schizophr. Bull. 40, 469–477. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbt044

Malhi, G. S., Lagopoulos, J., Sachdev, P. S., Ivanovski, B., and Shnier, R. (2005). An emotional stroop functional MRI study of euthymic bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 7, 58–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2005.00255.x

Manschreck, T. C., Maher, B. A., and Candela, S. F. (2004). Earlier age of first diagnosis in schizophrenia is related to impaired motor control. Schizophr. Bull. 30, 351–360. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007084

Mills, N. P., DelBello, M. P., Adler, C. M., and Strakowski, S. M. (2005). MRI analysis of cerebellar vermal abnormalities in bipolar disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 162, 1530–1533. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.8.1530

Moulton, E. A., Elman, I., Pendse, G., Schmahmann, J., Becerra, L., and Borsook, D. (2011). Aversion-related circuitry in the cerebellum: responses to noxious heat and unpleasant images. J. Neurosci. 31, 3795–3804. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6709-10.2011

Ongur, D., Drevets, W. C., and Price, J. L. (1998). Glial reduction in the subgenual prefrontal cortex in mood disorders. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 95, 13290–13295. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.22.13290

Pfefferbaum, A., Chanraud, S., Pitel, A. L., Müller-Oehring, E., Shankaranarayanan, A., Alsop, D. C., et al. (2011). Cerebral blood flow in posterior cortical nodes of the default mode network decreases with task engagement but remains higher than in most brain regions. Cereb. Cortex. 21, 233–244. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhq090

Rajkowska, G. (2000). Postmortem studies in mood disorders indicate altered numbers of neurons and glial cells. Biol. Psychiatry 48, 766–777. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)00950-1

Rajkowska, G. (2002). Cell pathology in mood disorders. Semin. Clin. Neuropsychiatry 7, 281–292. doi: 10.1053/scnp.2002.35228

Schmahmann, J. D. (2001). The cerebrocerebellar system: anatomic substrates of the cerebellar contribution to cognition and emotion. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 13, 247–260. doi: 10.1080/09540260120082092

Schmahmann, J. D. (2004). Disorders of the cerebellum: ataxia, dysmetria of thought and the cerebellar cognitive affective syndrome. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 16, 367–378. doi: 10.1176/jnp.16.3.367

Schmahmann, J. D. (2019). The cerebellum and cognition. Neurosci. Lett. 688, 62–75. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2018.07.005

Schutter, D. J., and Van Honk, J. (2005). The cerebellum on the rise in human emotion. Cerebellum 4, 290–294. doi: 10.1080/14734220500348584

Stoodley, C. J., and Schmahmann, J. D. (2009). Functional topography in the human cerebellum: a meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies. Neuroimage 44, 489–501. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.08.039

Strakowski, S. M., Adler, C. M., and DelBello, M. P. (2002). Volumetric MRI studies of mood disorders: do they distinguish unipolar and bipolar disorder? Bipolar Disord. 4, 80–88. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2002.01160.x

Strakowski, S. M., Adler, C. M., Holland, S. K., Mills, N., and DelBello, M. P. (2004). A preliminary FMRI study of sustained attention in euthymic, unmedicated bipolar disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology 29, 1734–1740. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300492

Tavano, A., Grasso, R., Gagliardi, C., Triulzi, F., Bresolin, N., Fabbro, F., et al. (2007). Disorders of cognitive and affective development in cerebellar malformations. Brain 130, 2646–2660. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm201

Torta, D. M., and Cauda, F. (2011). Different functions in the cingulate cortex, a meta-analytic connectivity modeling study. Neuroimage 56, 2157–2172. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.03.066

Weathers, J. D., Stringaris, A., Deveney, C. M., Brotman, M. A., Zarate, C. A., Jr., Connolly, M. E., et al. (2012). A developmental study of the neural circuitry mediating motor inhibition in bipolar disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 169, 633–641. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.11081244

Xu, K., Liu, H., Li, H., Tang, Y., Womer, F., Jiang, X., et al. (2014). Amplitude of low-frequency fluctuations in bipolar disorder: a resting state fMRI study. J. Affect. Disord. 152, 237–242. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.09.017

Keywords: bipolar disorder, resting state, functional connectivity, cerebellum, vermis

Citation: Li H, Liu H, Tang Y, Yan R, Jiang X, Fan G and Sun W (2021) Decreased Functional Connectivity of Vermis-Ventral Prefrontal Cortex in Bipolar Disorder. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 15:711688. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2021.711688

Received: 19 May 2021; Accepted: 25 June 2021;

Published: 16 July 2021.

Edited by:

Long-Biao Cui, People’s Liberation Army General Hospital, ChinaReviewed by:

Jie Gong, Xidian University, ChinaCopyright © 2021 Li, Liu, Tang, Yan, Jiang, Fan and Sun. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Guoguang Fan, ZmFuZ3VvZ0BzaW5hLmNvbQ==; Wenge Sun, d2VuZ2VzdW5Ac2luYS5jb20=

† These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.