- 1Department of Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation Science, School of Medicine, University of Maryland, Baltimore, MD, United States

- 2Human Cortical Physiology and Neurorehabilitation Section, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, Bethesda, MD, United States

Introduction

Learning is fundamental to rehabilitation (Krakauer, 2006). The learning of cognitive and motor tasks similar to those in rehabilitative services (i.e., occupational therapy, physical therapy, speech language pathology, recreational therapy, music therapy, etc.) involve the creation (or modification) of neural representations associated with task performance (Dayan and Cohen, 2011). Later accessing these representations allows for performance with greater skill. These neural representations can therefore be referred to as memory traces, and rehabilitation can be thought of as involving the creation and/or modification of memories that can be stored for use in other contexts in the future.

The process of learning is comprised of practice-dependent (i.e., online) and practice-independent (i.e., offline) processes. Skill acquisition during initial practice is typically exhibited by fast improvements in performance (Dayan and Cohen, 2011). After encoding a memory and halting practice, a memory can then undergo consolidation, leading to slower improvements over a period of seconds, days, weeks, or months. The purpose of this paper is two-fold: to identify the currently known mechanisms of consolidation and reconsolidation that impact learning, and to discuss how these findings could impact the design and optimization of interventions and strategies for rehabilitation services. The concepts discussed in this paper are applicable to various forms of learning (e.g., cognitive, motor, visual perceptual) but for simplicity, many of the studies highlighted in this paper involve motor learning.

Consolidation

Consolidation involves the stabilization (Brashers-Krug et al., 1996; Yotsumoto et al., 2009; Censor et al., 2010; Cohen and Robertson, 2011) or enhancement (Karni et al., 1994; Stickgold et al., 2000; Walker et al., 2002; Fischer et al., 2005; Korman et al., 2007; Nishida and Walker, 2007) of performance across a period of wakeful rest or sleep. The time period for consolidation to occur is typically over hours or perhaps longer based on the complexity of the task, which is referred to here as slow consolidation. More recently though, evidence of rapid within-session consolidation has been identified during the seconds of rest between trials of motor practice (Bönstrup et al., 2019, 2020).

Both implicit and explicit learning involve consolidation. While time alone (i.e., regardless of being awake or asleep) is sufficient for implicit aspects of memory, a period of sleep is necessary for slow consolidation of explicit aspects of memory (Robertson et al., 2004; Albouy et al., 2013, 2015).

The degree of consolidation over a sleep period has been associated with the number of occurrences of sleep spindles and slow wave electroencephalographic waveforms, which predominantly occur during non-rapid eye movement sleep over task-related brain regions (Nishida and Walker, 2007; Barakat et al., 2013; Tamaki et al., 2013). However, the number of sleep spindles and slow waves experienced during sleep decreases with age, which may explain the decrease in sleep-based consolidation found in older adults (Brown et al., 2009; Wilson et al., 2012; Fogel et al., 2014; Roig et al., 2014) and in individuals with sleep apnea (Djonlagic et al., 2012, 2015; Landry et al., 2014; Johnson et al., 2019b).

Reconsolidation

When later recalling (or performing) a memory that has been consolidated through slow consolidation, online and offline processes can occur again to further fine tune recall (or performance) of the memory, known as reconsolidation (Nader et al., 2000; Walker et al., 2003; Forcato et al., 2007; Lee, 2008; Sandrini et al., 2015; Amar-Halpert et al., 2017; Herszage and Censor, 2018) but see Hardwicke et al. (2016). Gradual session-by-session improvements of a previously acquired and consolidated task may be promoted by reconsolidation between sessions, which is triggered by practice-induced memory reactivation during the session (Censor et al., 2010) or even the presentation of a task-associated sensory cue without active practice (Bavassi et al., 2019). The process of fine-tuning a memory through reconsolidation necessitates the integration of new task information obtained during reactivation so that memories can remain relevant and effective. Such new information may be in the form of sensorimotor calibrations, contextual cues, or additional declarative information. Less is known about rapid reconsolidation during early skill learning (Bönstrup et al., 2019, 2020).

Interference of Consolidation and Reconsolidation

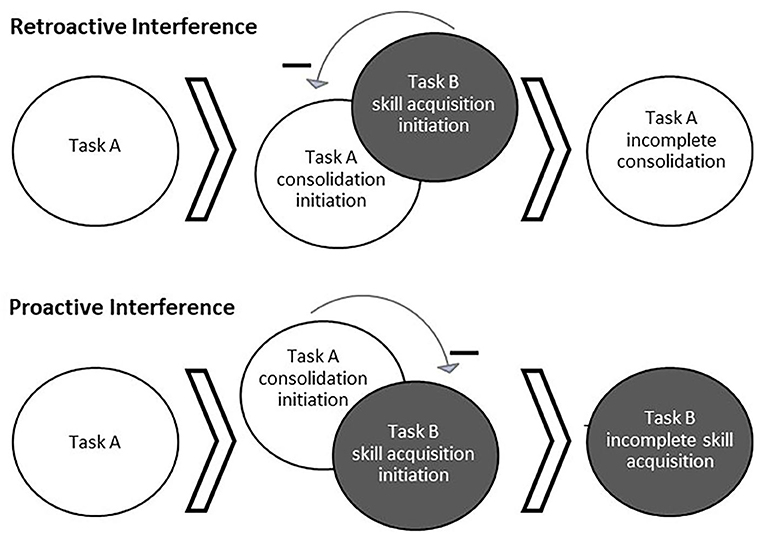

Memories are unstable while undergoing consolidation and reconsolidation and are thus susceptible to interference (Figure 1), making subsequent behavior and sleep between sessions crucial to learning (Walker et al., 2003; Forcato et al., 2007; Lee, 2008; Censor et al., 2010). When motor task A is acquired and the consolidation process has begun, the subsequent learning of a different task, task B, can impair consolidation of task A such that later recall performance of task A is impaired. This is known as retroactive interference (Shadmehr and Brashers-Krug, 1997; Ghilardi et al., 2009). For example, learning two different motor tasks within 5 min, 30 min, or 2.5 h was found to induce forgetting of the first motor task learned relative to a gap of 5.5 or 24 h (Shadmehr and Brashers-Krug, 1997). Alternatively, proactive interference can occur when the consolidation process of an initial task can temporarily impair learning of a different task (Ghilardi et al., 2009; Cantarero et al., 2013). For example, Cantarero et al. (2013) found that transiently increased cortical excitability induced through learning an initial motor skill interfered with immediate learning of a second motor skill. However, no retroactive or proactive interference was found if cortical excitability was allowed to return to baseline over time (Cantarero et al., 2013). It should be noted that interference can occur between different task types (i.e., cognitive and motor) (Brown and Robertson, 2007; Mutanen et al., 2020). The topic of memory modification during instability extends to reconsolidation as well. For example, implementing reward during memory reactivation (wherein no reward was present during initial learning) has been found to disrupt reconsolidation, possibly by creating a competing memory trace (Dayan et al., 2016). Whether interference of skill occurs relates to the degree of memory stability when beginning to learn the subsequent task, as well as the similarity of the tasks.

Figure 1. Behaviorally-induced retroactive and proactive interference. Interference occurs when the processes for learning multiple tasks interact and cause a detriment to the consolidation or acquisition of one of the tasks. Top: Acquisition of a second task (Task B) while a first task (Task A) is still undergoing consolidation can result in interference of Task A consolidation, known as retroactive interference. Bottom: Alternatively, ongoing consolidation of a first task (Task A) can interfere with the acquisition of a second task (Task B), known as proactive interference.

Preventing Interference Effects

An unstable memory can be modulated (and generalized) more easily, whereas a stable memory is harder to modulate. There are two primary factors that have been found to enable memories to stabilize. The first factor is the amount/duration of practice. Increasing the number of repetitions of task A helps to stabilize a memory trace, thereby reducing retroactive interference. However, increased repetitions of Task A can also transiently increase proactive interference to a subsequently learned task (i.e., Task B) as Task A is being consolidated (Krakauer et al., 2005; Shibata et al., 2017). This retroactive protective effect of increased practice duration extends to reconsolidation as well, as increasing the length of time during which the memory is reactivated decreases retroactive interference (de Beukelaar et al., 2014).

Second, the duration between sessions of learning helps to stabilize memories via consolidation. Allowing for several hours between task practice has been shown to decrease both retroactive and proactive interference compared to a period of several minutes between tasks (Walker et al., 2003; Krakauer et al., 2005; Ghilardi et al., 2009). Including a period of sleep between task practice sessions also reduces the proactive and retroactive interference between two tasks and lessens the amount of time required for consolidation compared to waking hours (Ellenbogen et al., 2006, 2009; Abel and Bäuml, 2014), but see Bailes et al. (2020). For reconsolidation, Gabitov et al. (2017) found that learning of a new motor task caused retroactive interference immediately after memory reactivation, but not if an 8-h interval was afforded following memory reactivation. Others have reported that the role of retroactive interference is greatest immediately after memory reactivation (i.e., 0 s) and fades in magnitude over a short period of time (i.e., 20, 40, and 60 s) as the memory is being reconsolidated (de Beukelaar et al., 2016).

Discussion

Consolidation and Reconsolidation During Rehabilitation

While consolidation and reconsolidation are relevant to psychotherapy treatments such as the extinction of fear memories (Monfils et al., 2009; Schiller et al., 2010), it remains to be seen whether rehabilitation services trigger consolidation and reconsolidation. There are long held principles that may make the consolidation and reconsolidation of memories during and after rehabilitation likely. For example, the notion of the “just right challenge,” holds that tasks performed during rehabilitation should be meaningful and difficult (Ayres, 1983; Csikszentmihalyi and LeFevre, 1989; Moneta and Csikszentmihalyi, 1996; Csikszentmihalyi, 2000), and should incorporate learning principles (e.g., practice structure, repetition, feedback, reward) (Poole, 1991; Jarus, 1994). Motor learning concepts such as goal-oriented training or task-specific training are important for skill acquisition during sessions, but interference between-sessions may occur and requires further investigation. That is, individuals receiving goal-oriented training or task-specific training in multiple rehabilitation services (e.g., occupational and physical therapy) may benefit from coordination of scheduling and therapy content. For example, occupational and physical therapies could be scheduled on alternating days, or with several hours of time between the two therapy sessions on a single day.

We propose that future research investigate consolidation and reconsolidation between rehabilitation sessions. Given the overwhelming evidence for the process of memory reconsolidation in declarative and procedural memories, it might be expected that individuals undergoing rehabilitation would also experience reconsolidation between sessions of therapy. For example, regaining independence in performing activities of daily living involves learning processes (Bayona et al., 2005). Importantly, older adults have been shown to benefit from reconsolidation (Corbin, 2017; Tassone et al., 2020) despite the known declines in consolidation related to healthy aging (Brown et al., 2009; Wilson et al., 2012; Fogel et al., 2014; Roig et al., 2014). However, one study found that reconsolidation was impaired in older adults with stroke relative to age-matched subjects without stroke (Censor et al., 2016), while other research has found that individuals with stroke, but not age-matched healthy controls, benefit from sleep-based consolidation of a motor task (Siengsukon and Boyd, 2008, 2009). Thus, further investigation into consolidation and reconsolidation among patient populations is warranted.

Recipients of rehabilitation would also benefit from the continued development of clinical protocols using non-invasive brain stimulation as an adjunct to enhance therapy-related memory consolidation and reconsolidation. Indeed, several studies regarding stroke rehabilitation have found benefits of pairing non-invasive brain stimulation with participation in rehabilitation (Khedr et al., 2005; Chang et al., 2010; Ilić et al., 2016; Rocha et al., 2016). In addition, transcranial direct current stimulation during wake (Reis et al., 2009, 2015; Sandrini et al., 2014) and during post-encoding sleep (Marshall et al., 2004, 2006; Göder et al., 2013; Westerberg et al., 2015), as well as repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation during wake (Turriziani, 2012; Sandrini et al., 2013), have previously been shown to enhance memory consolidation and reconsolidation. Other sensory stimulation techniques such as targeted memory reactivation (Rasch et al., 2007; Oudiette and Paller, 2013; Shimizu et al., 2018; Johnson et al., 2019a, 2020; Hu et al., 2020) and rhythmic auditory stimulation (Ngo et al., 2013; Ong et al., 2016) have been used during post-encoding sleep to enhance consolidation.

In addition to task-specific memory modulation, future research should also focus on how to best induce generalization of skill between therapies in relation to the degree of memory stability and task similarity. For example, Mosha and Robertson (2016) had participants learn a word list and a motor skill, with overlapping rules to task elements, in quick succession and showed that generalization could be induced between the tasks (regardless of learning order) when the first memory was unstable. However, generalization did not occur when the memory for the first task was stabilized through the inclusion of a 2-h consolidation period. That is, generalization can occur to a Task B during instability of Task A, but such generalization can also come at the cost of retroactive interference to Task A (Robertson, 2018; Mutanen et al., 2020).

Conclusions

Rehabilitation often involves learning. We first describe why clinicians should consider memory consolidation and reconsolidation. Secondly, we encourage future research to investigate how consolidation and reconsolidation relate to rehabilitation and translate previous work to decrease interference effects and enhance memory consolidation between rehabilitation sessions. Doing so may aid in the development of efficient and long-lasting interventions that are generalizable to clinically meaningful activities.

Author Contributions

BJ: conceptualization, literature review, and manuscript writing. LC and KW: conceptualization and manuscript writing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research was supported (in part) by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, NINDS.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Abel, M., and Bäuml, K.-H. T. (2014). Sleep can reduce proactive interference. Memory 22, 332–339. doi: 10.1080/09658211.2013.785570

Albouy, G., Fogel, S., King, B. R., Laventure, S., Benali, H., Karni, A., et al. (2015). Maintaining vs. enhancing motor sequence memories: Respective roles of striatal and hippocampal systems. Neuroimage 108, 423–434. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.12.049

Albouy, G., Fogel, S., Pottiez, H., Nguyen, V. A., Ray, L., Lungu, O., et al. (2013). Daytime sleep enhances consolidation of the spatial but not motoric representation of motor sequence memory. PLoS ONE 8:e52805. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052805

Amar-Halpert, R., Laor-Maayany, R., Nemni, S., Rosenblatt, J. D., and Censor, N. (2017). Memory reactivation improves visual perception. Nat. Neurosci. 20, 1325–1328. doi: 10.1038/nn.4629

Ayres, J. (1983). “The art of therapy,” in Sensory Integration and Learning Disabilities, ed J. A. Ayres (Torrance, CA: Western Psychological Services), 256–266.

Bailes, C., Caldwell, M., Wamsley, E. J., and Tucker, M. A. (2020). Does sleep protect memories against interference? a failure to replicate. PLoS ONE 15:e0220419. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0220419

Barakat, M., Carrier, J., Debas, K., Lungu, O., Fogel, S., Vandewalle, G., et al. (2013). Sleep spindles predict neural and behavioral changes in motor sequence consolidation. Hum. Brain Mapp. 34, 2918–2928. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22116

Bavassi, L., Forcato, C., Fernández, R. S., De Pino, G., Pedreira, M. E., and Villarreal, M. F. (2019). Retrieval of retrained and reconsolidated memories are associated with a distinct neural network. Sci. Rep. 9:784. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-37089-2

Bayona, N. A., Bitensky, J., Salter, K., and Teasell, R. (2005). The role of task-specific training in rehabilitation therapies. Top. Stroke Rehabil. 12, 58–65. doi: 10.1310/BQM5-6YGB-MVJ5-WVCR

Bönstrup, M., Iturrate, I., Hebart, M. N., Censor, N., and Cohen, L. G. (2020). Mechanisms of offline motor learning at a microscale of seconds in large-scale crowdsourced data. Npj Sci. Learn. 5, 1–10. doi: 10.1038/s41539-020-0066-9

Bönstrup, M., Iturrate, I., Thompson, R., Cruciani, G., Censor, N., and Cohen, L. G. (2019). A rapid form of offline consolidation in skill learning. Curr. Biol. 29, 1346–1351. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2019.02.049

Brashers-Krug, T., Shadmehr, R., and Bizzi, E. (1996). Consolidation in human motor memory. Nature 382, 252–255. doi: 10.1038/382252a0

Brown, R. M., and Robertson, E. M. (2007). Off-Line processing: reciprocal interactions between declarative and procedural memories. J. Neurosci. 27, 10468–10475. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2799-07.2007

Brown, R. M., Robertson, E. M., and Press, D. Z. (2009). Sequence skill acquisition and off-line learning in normal aging. PLoS ONE 4:e6683. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006683

Cantarero, G., Tang, B., O'Malley, R., Salas, R., and Celnik, P. (2013). Motor learning interference is proportional to occlusion of LTP-like plasticity. J. Neurosci. 33, 4634–4641. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4706-12.2013

Censor, N., Buch, E. R., Nader, K., and Cohen, L. G. (2016). Altered human memory modification in the presence of normal consolidation. Cereb. Cortex 26, 3828–3837. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhv180

Censor, N., Dimyan, M. A., and Cohen, L. G. (2010). Modification of existing human motor memories is enabled by primary cortical processing during memory reactivation. Curr. Biol. 20, 1545–1549. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.07.047

Chang, W. H., Kim, Y.-H., Bang, O. Y., Kim, S. T., Park, Y. H., and Lee, P. K. W. (2010). Long-term effects of rTMS on motor recovery in patients after subacute stroke. J. Rehabil. Med. 42, 758–764. doi: 10.2340/16501977-0590

Cohen, D. A., and Robertson, E. M. (2011). Preventing interference between different memory tasks. Nat. Neurosci. 14, 953–955. doi: 10.1038/nn.2840

Corbin, S. M. P. (2017). The Effects of Healthy Aging On Memory Reconsolidation. https://repository.arizona.edu/handle/10150/625609 (accessed November 05, 2020).

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Happiness, flow, and economic equality. Am. Psychol. 55, 1163–1164. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.10.1163

Csikszentmihalyi, M., and LeFevre, J. (1989). Optimal experience in work and leisure. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 56, 815–822. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.56.5.815

Dayan, E., and Cohen, L. G. (2011). Neuroplasticity subserving motor skill learning. Neuron 72, 443–454. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.10.008

Dayan, E., Laor-Maayany, R., and Censor, N. (2016). Reward disrupts reactivated human skill memory. Sci. Rep. 6, 1–7. doi: 10.1038/srep28270

de Beukelaar, T. T., Woolley, D. G., Alaerts, K., Swinnen, S. P., and Wenderoth, N. (2016). Reconsolidation of motor memories is a time-dependent process. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 10:408. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2016.00408

de Beukelaar, T. T., Woolley, D. G., and Wenderoth, N. (2014). Gone for 60 seconds: reactivation length determines motor memory degradation during reconsolidation. Cortex 59, 138–145. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2014.07.008

Djonlagic, I., Guo, M., Matteis, P., Carusona, A., Stickgold, R., and Malhotra, A. (2015). First night of CPAP: impact on memory consolidation attention and subjective experience. Sleep Med. 16, 697–702. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2015.01.017

Djonlagic, I., Saboisky, J., Carusona, A., Stickgold, R., and Malhotra, A. (2012). Increased sleep fragmentation leads to impaired off-line consolidation of motor memories in humans. PLoS ONE 7:e34106. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034106

Ellenbogen, J. M., Hulbert, J. C., Jiang, Y., and Stickgold, R. (2009). The sleeping brain's influence on verbal memory: boosting resistance to interference. PLoS ONE 4:e4117. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004117

Ellenbogen, J. M., Hulbert, J. C., Stickgold, R., Dinges, D. F., and Thompson-Schill, S. L. (2006). Interfering with theories of sleep and memory: sleep, declarative memory, and associative interference. Curr. Biol. 16, 1290–1294. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.05.024

Fischer, S., Nitschke, M. F., Melchert, U. H., Erdmann, C., and Born, J. (2005). Motor memory consolidation in sleep shapes more effective neuronal representations. J. Neurosci. 25, 11248–11255. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1743-05.2005

Fogel, S. M., Albouy, G., Vien, C., Popovicci, R., King, B. R., Hoge, R., et al. (2014). FMRI and sleep correlates of the age-related impairment in motor memory consolidation. Hum. Brain Mapp. 35, 3625–3645. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22426

Forcato, C., Burgos, V. L., Argibay, P. F., Molina, V. A., Pedreira, M. E., and Maldonado, H. (2007). Reconsolidation of declarative memory in humans. Learn. Mem. 14, 295–303. doi: 10.1101/lm.486107

Gabitov, E., Boutin, A., Pinsard, B., Censor, N., Fogel, S. M., Albouy, G., et al. (2017). Re-stepping into the same river: competition problem rather than a reconsolidation failure in an established motor skill. Sci. Rep. 7:9406. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-09677-1

Ghilardi, M. F., Moisello, C., Silvestri, G., Ghez, C., and Krakauer, J. W. (2009). Learning of a sequential motor skill comprises explicit and implicit components that consolidate differently. J. Neurophysiol. 101, 2218–2229. doi: 10.1152/jn.01138.2007

Göder, R., Baier, P. C., Beith, B., Baecker, C., Seeck-Hirschner, M., Junghanns, K., et al. (2013). Effects of transcranial direct current stimulation during sleep on memory performance in patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 144, 153–154. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.12.014

Hardwicke, T., Taqi, M., and Shanks, D. (2016). Postretrieval new learning does not reliably induce human memory updating via reconsolidation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113:201601440. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1601440113

Herszage, J., and Censor, N. (2018). Modulation of learning and memory: a shared framework for interference and generalization. Neuroscience 392, 270–280. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2018.08.006

Hu, X., Cheng, L. Y., Chiu, M. H., and Paller, K. A. (2020). Promoting memory consolidation during sleep: a meta-analysis of targeted memory reactivation. Psychol. Bull. 146, 218–244. doi: 10.1037/bul0000223

Ilić, N. V., Dubljanin-Raspopović, E., Nedeljković, U., Tomanović-Vujadinović, S., Milanović, S. D., Petronić-Marković, I., et al. (2016). Effects of anodal tDCS and occupational therapy on fine motor skill deficits in patients with chronic stroke. Restor. Neurol. Neurosci. 34, 935–945. doi: 10.3233/RNN-160668

Jarus, T. (1994). Motor learning and occupational therapy: the organization of practice. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 48, 810–816. doi: 10.5014/ajot.48.9.810

Johnson, B. P., Scharf, S. M., Verceles, A. C., and Westlake, K. P. (2019a). Use of targeted memory reactivation enhances skill performance during a nap and enhances declarative memory during wake in healthy young adults. J. Sleep Res. 28:e12832. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12832

Johnson, B. P., Scharf, S. M., Verceles, A. C., and Westlake, K. P. (2020). Sensorimotor performance is improved by targeted memory reactivation during a daytime nap in healthy older adults. Neurosci. Lett. 731:134973. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2020.134973

Johnson, B. P., Shipper, A. G., and Westlake, K. P. (2019b). Systematic review investigating the effects of nonpharmacological interventions during sleep to enhance physical rehabilitation outcomes in people with neurological diagnoses. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 33, 345–354. doi: 10.1177/1545968319840288

Karni, A., Tanne, D., Rubenstein, B. S., Askenasy, J. J., and Sagi, D. (1994). Dependence on REM sleep of overnight improvement of a perceptual skill. Science 265, 679–682. doi: 10.1126/science.8036518

Khedr, E. M., Ahmed, M. A., Fathy, N., and Rothwell, J. C. (2005). Therapeutic trial of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation after acute ischemic stroke. Neurology 65, 466–468. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000173067.84247.36

Korman, M., Doyon, J., Doljansky, J., Carrier, J., Dagan, Y., and Karni, A. (2007). Daytime sleep condenses the time course of motor memory consolidation. Nat. Neurosci. 10, 1206–1213. doi: 10.1038/nn1959

Krakauer, J. W. (2006). Motor learning: its relevance to stroke recovery and neurorehabilitation. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 19, 84–90. doi: 10.1097/01.wco.0000200544.29915.cc

Krakauer, J. W., Ghez, C., and Ghilardi, M. F. (2005). Adaptation to visuomotor transformations: consolidation, interference, and forgetting. J. Neurosci. 25, 473–478. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4218-04.2005

Landry, S., Anderson, C., Andrewartha, P., Sasse, A., and Conduit, R. (2014). The impact of obstructive sleep apnea on motor skill acquisition and consolidation. J. Clin. Sleep Med. Off. Publ. Am. Acad. Sleep Med. 10, 491–496. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.3692

Lee, J. L. C. (2008). Memory reconsolidation mediates the strengthening of memories by additional learning. Nat. Neurosci. 11, 1264–1266. doi: 10.1038/nn.2205

Marshall, L., Helgadóttir, H., Mölle, M., and Born, J. (2006). Boosting slow oscillations during sleep potentiates memory. Nature 444, 610–613. doi: 10.1038/nature05278

Marshall, L., Mölle, M., Hallschmid, M., and Born, J. (2004). Transcranial direct current stimulation during sleep improves declarative memory. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 24, 9985–9992. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2725-04.2004

Moneta, G. B., and Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1996). The effect of perceived challenges and skills on the quality of subjective experience. J. Pers. 64, 275–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1996.tb00512.x

Monfils, M.-H., Cowansage, K. K., Klann, E., and LeDoux, J. E. (2009). Extinction-reconsolidation boundaries: key to persistent attenuation of fear memories. Science 324, 951–955. doi: 10.1126/science.1167975

Mosha, N., and Robertson, E. M. (2016). Unstable memories create a high-level representation that enables learning transfer. Curr. Biol. 26, 100–105. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.11.035

Mutanen, T. P., Bracco, M., and Robertson, E. M. (2020). A common task structure links together the fate of different types of memories. Curr. Biol. 30, 2139–2145. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2020.03.043

Nader, K., Schafe, G. E., and Le Doux, J. E. (2000). Fear memories require protein synthesis in the amygdala for reconsolidation after retrieval. Nature 406, 722–726. doi: 10.1038/35021052

Ngo, H.-V. V., Martinetz, T., Born, J., and Mölle, M. (2013). Auditory closed-loop stimulation of the sleep slow oscillation enhances memory. Neuron 78, 545–553. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.03.006

Nishida, M., and Walker, M. P. (2007). Daytime naps, motor memory consolidation, and regionally specific sleep spindles. PLoS ONE 2:e341. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000341

Ong, J. L., Lo, J. C., Chee, N. I. Y. N., Santostasi, G., Paller, K. A., Zee, P. C., et al. (2016). Effects of phase-locked acoustic stimulation during a nap on EEG spectra and declarative memory consolidation. Sleep Med. 20, 88–97. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2015.10.016

Oudiette, D., and Paller, K. A. (2013). Upgrading the sleeping brain with targeted memory reactivation. Trends Cogn. Sci. 17, 142–149. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2013.01.006

Poole, J. L. (1991). Application of motor learning principles in occupational therapy. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 45, 531–537. doi: 10.5014/ajot.45.6.531

Rasch, B., Büchel, C., Gais, S., and Born, J. (2007). Odor cues during slow-wave sleep prompt declarative memory consolidation. Science 315, 1426–1429. doi: 10.1126/science.1138581

Reis, J., Fischer, J. T., Prichard, G., Weiller, C., Cohen, L. G., and Fritsch, B. (2015). Time- but not sleep-dependent consolidation of tDCS-enhanced visuomotor skills. Cereb. Cortex 25, 109–117. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bht208

Reis, J., Schambra, H. M., Cohen, L. G., Buch, E. R., Fritsch, B., Zarahn, E., et al. (2009). Noninvasive cortical stimulation enhances motor skill acquisition over multiple days through an effect on consolidation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 1590–1595. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805413106

Robertson, E. M. (2018). Memory instability as a gateway to generalization. PLoS Biol. 16:e2004633. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2004633

Robertson, E. M., Pascual-Leone, A., and Press, D. Z. (2004). Awareness modifies the skill-learning benefits of sleep. Curr. Biol. 14, 208–212. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.01.027

Rocha, S., Silva, E., Foerster, Á., Wiesiolek, C., Chagas, A. P., Machado, G., et al. (2016). The impact of transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) combined with modified constraint-induced movement therapy (mCIMT) on upper limb function in chronic stroke: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. Disabil. Rehabil. 38, 653–660. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2015.1055382

Roig, M., Ritterband-Rosenbaum, A., Lundbye-Jensen, J., and Nielsen, J. B. (2014). Aging increases the susceptibility to motor memory interference and reduces off-line gains in motor skill learning. Neurobiol. Aging 35, 1892–1900. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.02.022

Sandrini, M., Brambilla, M., Manenti, R., Rosini, S., Cohen, L. G., and Cotelli, M. (2014). Noninvasive stimulation of prefrontal cortex strengthens existing episodic memories and reduces forgetting in the elderly. Front. Aging Neurosci. 6:289. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2014.00289

Sandrini, M., Censor, N., Mishoe, J., and Cohen, L. G. (2013). Causal role of prefrontal cortex in strengthening of episodic memories through reconsolidation. Curr. Biol. 23, 2181–2184. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.08.045

Sandrini, M., Cohen, L. G., and Censor, N. (2015). Modulating reconsolidation: a link to causal systems-level dynamics of human memories. Trends Cogn. Sci. 19, 475–482. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2015.06.002

Schiller, D., Monfils, M.-H., Raio, C. M., Johnson, D. C., LeDoux, J. E., and Phelps, E. A. (2010). Preventing the return of fear in humans using reconsolidation update mechanisms. Nature 463, 49–53. doi: 10.1038/nature08637

Shadmehr, R., and Brashers-Krug, T. (1997). Functional stages in the formation of human long-term motor memory. J. Neurosci. 17, 409–419. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-01-00409.1997

Shibata, K., Sasaki, Y., Bang, J. W., Walsh, E. G., Machizawa, M. G., Tamaki, M., et al. (2017). Overlearning hyperstabilizes a skill by rapidly making neurochemical processing inhibitory-dominant. Nat. Neurosci. 20, 470–475. doi: 10.1038/nn.4490

Shimizu, R. E., Connolly, P. M., Cellini, N., Armstrong, D. M., Hernandez, L. T., Estrada, R., et al. (2018). Closed-loop targeted memory reactivation during sleep improves spatial navigation. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 12:28. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2018.00028

Siengsukon, C. F., and Boyd, L. A. (2008). Sleep enhances implicit motor skill learning in individuals poststroke. Top. Stroke Rehabil. 15, 1–12. doi: 10.1310/tsr1501-1

Siengsukon, C. F., and Boyd, L. A. (2009). Sleep to learn after stroke: implicit and explicit off-line motor learning. Neurosci. Lett. 451, 1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.12.040

Stickgold, R., James, L., and Hobson, J. A. (2000). Visual discrimination learning requires sleep after training. Nat. Neurosci. 3, 1237–1238. doi: 10.1038/81756

Tamaki, M., Huang, T.-R., Yotsumoto, Y., Hämäläinen, M., Lin, F.-H., Náñez, J. E., et al. (2013). Enhanced spontaneous oscillations in the supplementary motor area are associated with sleep-dependent offline learning of finger-tapping motor-sequence task. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 33, 13894–13902. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1198-13.2013

Tassone, L. M., Benítez, F. A. U., Rochon, D., Martínez, P. B., Bonilla, M., Leon, C. S., et al. (2020). Memory reconsolidation as a tool to endure encoding deficits in elderly. PLoS ONE 15:e0237361. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0237361

Turriziani, P. (2012). Enhancing memory performance with rTMS in healthy subjects and individuals with Mild Cognitive Impairment: the role of the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 6:62. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2012.00062

Walker, M. P., Brakefield, T., Hobson, J. A., and Stickgold, R. (2003). Dissociable stages of human memory consolidation and reconsolidation. Nature 425, 616–620. doi: 10.1038/nature01930

Walker, M. P., Brakefield, T., Morgan, A., Hobson, J. A., and Stickgold, R. (2002). Practice with sleep makes perfect: sleep-dependent motor skill learning. Neuron 35, 205–211. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(02)00746-8

Westerberg, C. E., Florczak, S. M., Weintraub, S., Mesulam, M.-M., Marshall, L., Zee, P. C., et al. (2015). Memory improvement via slow-oscillatory stimulation during sleep in older adults. Neurobiol. Aging 36, 2577–2586. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.05.014

Wilson, J. K., Baran, B., Pace-Schott, E. F., Ivry, R. B., and Spencer, R. M. C. (2012). Sleep modulates word-pair learning but not motor sequence learning in healthy older adults. Neurobiol. Aging 33, 991–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.06.029

Keywords: occupational therapy, physical therapy, neurorehabilitation, motor learning, memory consolidation

Citation: Johnson BP, Cohen LG and Westlake KP (2021) The Intersection of Offline Learning and Rehabilitation. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 15:667574. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2021.667574

Received: 13 February 2021; Accepted: 24 March 2021;

Published: 21 April 2021.

Edited by:

Ryouhei Ishii, Osaka Prefecture University, JapanReviewed by:

Takayuki Tabira, Kagoshima University, JapanLorie Gage Richards, The University of Utah, United States

Copyright © 2021 Johnson, Cohen and Westlake. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Brian P. Johnson, YnJpYW4uam9obnNvbkBzb20udW1hcnlsYW5kLmVkdQ==

Brian P. Johnson

Brian P. Johnson Leonardo G. Cohen

Leonardo G. Cohen Kelly P. Westlake

Kelly P. Westlake