- 1Institute of Cognitive Neuroscience, University College London, London, UK

- 2Speech, Hearing and Phonetic Sciences, University College London, London, UK

A commentary on

Music enrichment programs improve the neural encoding of speech in at-risk children

by Kraus, N., Slater, J., Thompson, E. C., Hornickel, J., Strait, D. L., Nicol, T., et al. (2014). J. Neurosci. 34, 11913–11918. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1881-14.2014

Speech perception problems lead to many different forms of communication difficulties, and remediation for these problems remains of critical interest. A recent study by Kraus et al. (2014b) published in the Journal of Neuroscience, used a randomized controlled trial (RCT) approach to identify how low intensity community-based musical enrichment for “at-risk children” improved neural discrimination of “ba/ga” syllables. In the study, forty-four children aged six to nine years from “gang reduction zones” received 2 hours of musical training each week arranged in two 1 hour sessions. A control group received a single year of training following a one year delay, whilst the experimental group received two full years of training without delay. They found that auditory brainstem responses (ABRs) to the “ba/ga” syllables were changed in the experimental group, but only after more than one year of training. ABRs were not changed in the control group, either following the delay or after the first full year of training. We endorse the use of a randomized control trial (RCT) to evaluate this educational programme, but argue that several additional criteria must be met before firm conclusions can be drawn about the benefits of the intervention.

Kraus et al. argue their results provide evidence that “community music programs may stave off certain language-based challenges” (Kraus et al., 2014b, p. 11915), but this claim is hard to sustain without behavioral data (e.g., of concomitant improvements in speech perception or literacy). For the current paper, it would be necessary to show group differences in behavior that relate to the educational program, and explore the ways that individual differences in neural and behavioral profiles vary with the speech and literacy measures. This is particularly important given that a meaningful musicianship advantage in speech perception can be hard to demonstrate, as the size of the advantage shown for musicians (compared to non-musicians) is small (<1 dB) (Parbery-Clark et al., 2009) and has not been consistently replicated (Fuller et al., 2014; Ruggles et al., 2014). We also note a more recent follow up study (Kraus et al., 2014a) shows no improvement in literacy skills associated with active musical engagement.

There are other important issues: for example, Kraus et al. presented a single pair of synthesized “ba” and “ga” syllables 6000 times, at a rate of 4.35 repetitions per second, to each participant. No naturally occurring human speech sequences occur like this: speech tokens are never identical, and repetition itself is normally avoided as it is low in informational value (change, not repetition, conveys information) and leads to illusory percepts (cf. the verbal transformation effect, Pitt and Shoaf, 2002).

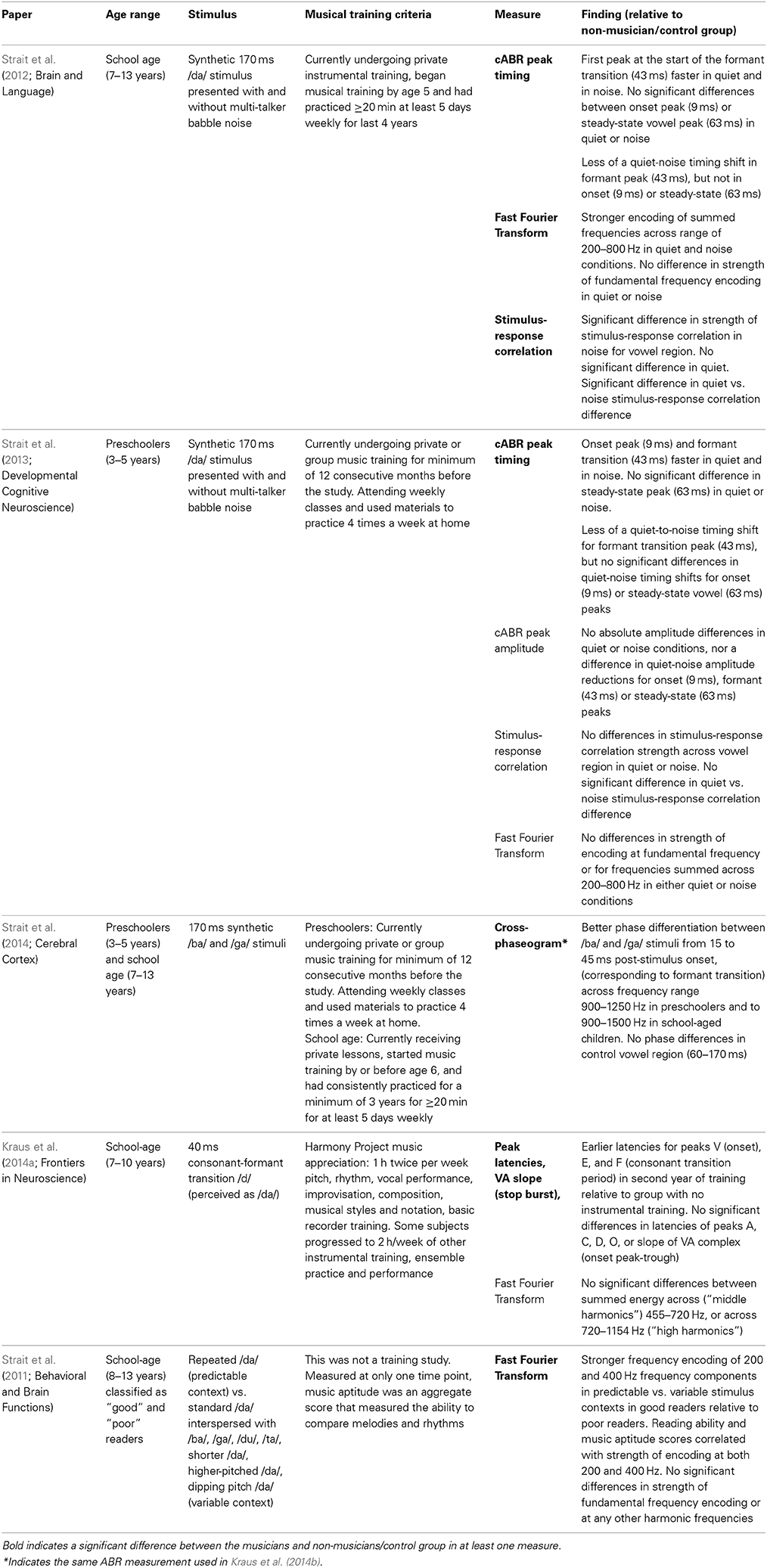

In addition, these items were synthesized speech tokens in which a single acoustic cue (the trajectory of the second format, F2) was manipulated. Notably, the major frequency difference where the F2s are maximally different between ba and ga (900–2480 Hz) are not investigated as the cross-phaseogram measurements are restricted to 900–1500 Hz, due to a lack of phase locking above 1500 Hz (Aiken and Picton, 2008). This frequency “window” restricts the analysis to a range where the whole F2 sweep for “ba” is included, but most of that for “ga” is excluded from the analysis (see Figure in Supplementary Materials, Hornickel et al., 2009). This suggests that the response is not specifically discriminant per se, and may be associated with detection of the presence of “ba” stimuli. A contrast of “ba” with “da,” which has a lower F2 sweep, would be a way to address this. To further develop our understanding of these ABR effects, it is also essential to understand how the measurements used in this study relate to the auditory brain stem and cortex measures used in other investigations, of the effects of musical training. Table 1 shows a summary of the ABR papers on musical training in children which illustrates the wide variety of measures used and their significance across studies.

Table 1. A summary of the ABR papers on musical training in children which illustrates the wide variety of measures used and their significance across studies.

RCTs involve certain design features, which Kraus et al. do not always fully exploit: for example, the difference in the size between the control (n = 18) and the experimental (n = 26) groups is unexplained, and may require a different statistical approach (Keselman and Keselman, 1990). The lack of an active control group prevents us from understanding whether the reported neural changes could be induced by an alternative enrichment activity (which is acknowledged by the authors), or whether a more focused language or literacy intervention would have yielded more effective results. It is also important to stress that while the paper makes specific claims about treatment effects for “impoverished brains” (e.g., individuals from low socio-economic backgrounds), no direct evidence of this impoverishment is provided, nor evidence that the effects on “impoverished” brains are any different to the effects on non-impoverished brains, e.g., by including another control group. RCT methodology requires the reporting of the system used to generate the random allocation sequence, as well as mentioning participant drop-out rates, means, SDs, effect sizes and associated confidence intervals. Although an important first step, this paper falls some way short of suggested recommendations for the reporting of RCTs (Schulz et al., 2010).

To conclude, we have critiqued a recent high impact intervention study examining the effect of musical training on neural responses. Ineffective interventions provide false hope and waste financial resources (Strong et al., 2011) and therefore intervention programmes need to be evaluated rigorously. It is admirable to investigate the potential of community based musical training to improve neural coding of speech, but we argue that a stronger standard of evidence is required before concluding that musical enrichment enhances speech, language and literacy skills.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust (WT074414MA to S.K.S.).

References

Aiken, S. J., and Picton, T. W. (2008). Envelope and spectral frequency-following responses to vowel sounds. Hear. Res. 245, 35–47. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2008.08.004

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Fuller, C. D., Galvin, J. J., Maat, B., Free, R. H., and Başkent, D. (2014). The musician effect: does it persist under degraded pitch conditions of cochlear implant simulations? Front. Neurosci. 8:179. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2014.00179

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Hornickel, J., Skoe, E., Nicol, T., Zecker, S., and Kraus, N. (2009). Subcortical differentiation of stop consonants relates to reading and speech-in-noise perception. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 13022–13027. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901123106

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Keselman, J. C., and Keselman, H. J. (1990). Analysing unbalanced repeated measures designs. Br. J. Math. Stat. Psychol. 43, 265–282.

Kraus, N., Slater, J., Thompson, E. C., Hornickel, J., Strait, D. L., Nicol, T., et al. (2014a). Auditory learning through active engagement with sound: biological impact of community music lessons in at-risk children. Front. Neurosci. 8:351. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2014.00351

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kraus, N., Slater, J., Thompson, E. C., Hornickel, J., Strait, D. L., Nicol, T., et al. (2014b). Music enrichment programs improve the neural encoding of speech in at-risk children. J. Neurosci. 34, 11913–11918. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1881-14.2014

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Parbery-Clark, A., Skoe, E., Lam, C., and Kraus, N. (2009). Musician Enhancement for Speech-In-Noise. Ear Hear. 30, 653–661. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e3181b412e9

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Pitt, M. A., and Shoaf, L. (2002). Linking verbal transformations to their causes. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 28, 150–162. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.28.1.150

Ruggles, D. R., Freyman, R. L., and Oxenham, A. J. (2014). Influence of musical training on understanding voiced and whispered speech in noise. PLoS ONE 9:e86980. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086980

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Schulz, K. F., Altman, D. G., Moher, D., and Group, C. (2010). CONSORT 2010 Statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomized trials. Ann. Intern. Med. 152, 726–732. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-11-201006010-00232

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Strait, D. L., Hornickel, J., and Kraus, N. (2011). Subcortical processing of speech regularities underlies reading and music aptitude in children. Behav. Brain Funct. 7:44. doi: 10.1186/1744-9081-7-44

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Strait, D. L., O'Connell, S., Parbery-Clark, A., and Kraus, N. (2014). Musicians' enhanced neural differentiation of speech sounds arises early in life: developmental evidence from ages 3 to 30. Cereb. Cortex 24, 2512–2521. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bht103

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Strait, D. L., Parbery-Clark, A., Hittner, E., and Kraus, N. (2012). Musical training during early childhood enhances the neural encoding of speech in noise. Brain Lang. 123, 191–201. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2012.09.001

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Strait, D. L., Parbery-Clark, A., O'Connell, S., and Kraus, N. (2013). Biological impact of preschool music classes on processing speech in noise. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 6, 51–60. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2013.06.003

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Strong, G. K., Torgerson, C. J., Torgerson, D., and Hulme, C. (2011). A systematic meta-analytic review of evidence for the effectiveness of the “Fast ForWord” language intervention program. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 52, 224–235. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02329.x

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Keywords: musicianship, speech perception, literacy, intervention, auditory brainstem response (ABR)

Citation: Evans S, Meekings S, Nuttall HE, Jasmin KM, Boebinger D, Adank P and Scott SK (2014) Does musical enrichment enhance the neural coding of syllables? Neuroscientific interventions and the importance of behavioral data. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 8:964. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2014.00964

Received: 10 October 2014; Accepted: 12 November 2014;

Published online: 16 December 2014.

Edited by:

Lynne E. Bernstein, George Washington University, USAReviewed by:

Dorothy Bishop, University of Oxford, UKCopyright © 2014 Evans, Meekings, Nuttall, Jasmin, Boebinger, Adank and Scott. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence:c2FtdWVsLmV2YW5zQHVjbC5hYy51aw==

Samuel Evans

Samuel Evans Sophie Meekings

Sophie Meekings Helen E. Nuttall

Helen E. Nuttall Kyle M. Jasmin

Kyle M. Jasmin Dana Boebinger1

Dana Boebinger1 Patti Adank

Patti Adank Sophie K. Scott

Sophie K. Scott