95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

PERSPECTIVE article

Front. Hum. Neurosci. , 06 July 2012

Sec. Cognitive Neuroscience

Volume 6 - 2012 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2012.00203

Jürgen Kornmeier1,2* and Zrinka Sosic-Vasic3,4

Jürgen Kornmeier1,2* and Zrinka Sosic-Vasic3,4Repeated learning improves memory. Temporally distributed (“spaced”) learning can be twice as efficient than massed learning. Importantly, learning success is a non-monotonic maximum function of the spacing interval between learning units. Further optimal spacing intervals seem to exist at different time scales from seconds to days. We briefly review the current state of knowledge about this “spacing effect” and then discuss very similar but so far little noticed spacing patterns during a form of synaptic plasticity at the cellular level, called long term potentiation (LTP). The optimization of learning is highly relevant for all of us. It may be realized easily with appropriate spacing. In our view, the generality of the spacing effect points to basic mechanisms worth for coordinated research on the different levels of complexity.

Our ability to store information and to use it in a reflexive way is essential for the successful interaction with our environment. Understanding the mechanisms underlying learning and memory is a central goal in cognitive and neurosciences. A promising strategy in this direction may be to study parameters that optimize learning and memory.

Increasing the number of learning repetitions (e.g., memorizing vocabularies more often) improves memory, which is well known. Less well known may be, however, that massed learning is less efficient than spaced learning: two spaced learning sessions can be twice as efficient as two learning sessions without spacing (“massed” sessions). This means that the same amount of learning time can be twice as efficient if executed with the optimal spacing schedule. This phenomenon is called the “spacing effect”. As early as 1885 the German psychologist Herrmann Ebbinghaus observed in one of his numerous memory experiments that 38 learning repetitions distributed over three days resulted in the same memory performance as with 68 massed repetitions (Ebbinghaus, 1913). “Spacing interval” can mean the time without mental engagement between two presentations of the learning content. In principle, the learner can use this time to rehearse the learning content mentally. Alternatively, the spacing interval can be filled with different learning contents and quantified by their number.

Spacing effects have been found with a variety of test paradigms including free recall, cued recall, and recognition memory (however see Litman and Davachi, 2010), and for a multitude of learning materials, like sense and nonsense syllables, words, word pairs (e.g., vocabulary learning), pictures, arithmetic rules, scientific, and mathematical concepts, or scientific terms (e.g., Ebbinghaus, 1913; Dempster, 1996). Spacing effects occur with multimodal (auditory and visual) stimulation (Janiszewski et al., 2003), with intentional, and also with incidental learning (e.g., Challis, 1993; Toppino et al., 2002). The spacing effect is observed from 4-year-old children (Rea and Modigliani, 1987) up to 76 year old seniors (Balota et al., 1989; Toppino, 1991). It has been also observed in animals such as rodents (Lattal, 1999), Aplysia (Mauelshagen et al., 1998), and even within Drosophila (Yin et al., 1995). Due to this universality, the mechanisms underlying the spacing effect are assumed to be basic and highly automatic (Rea and Modigliani, 1987; Toppino, 1991; Dempster, 1996).

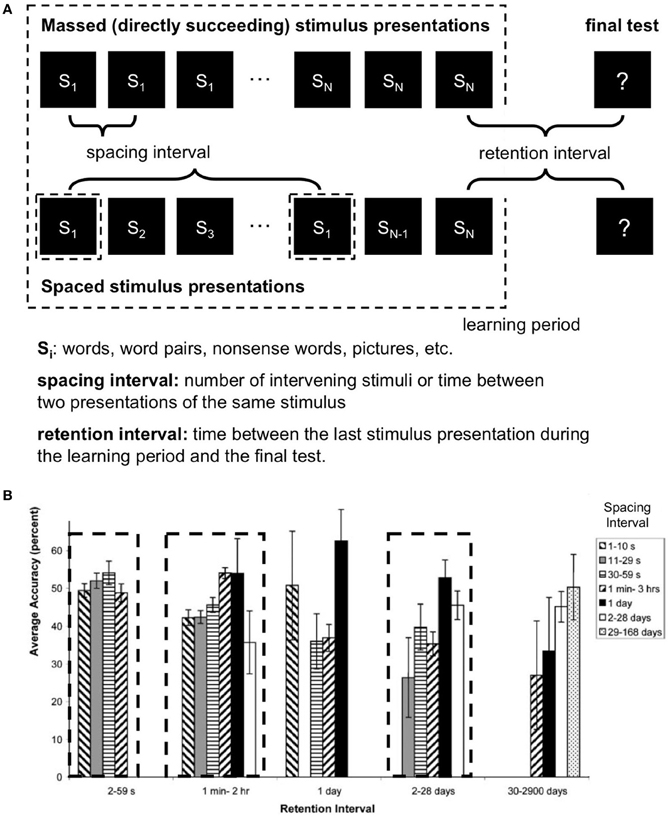

Increasing the spacing interval, i.e., the time between learning repetitions (Figure 1A, Melton, 1970; Toppino and Bloom, 2002; Kahana and Howard, 2005) improves memory performance. However, it turns out that this effect is non-monotonic: After a certain optimal spacing interval, memory performance declines again (Donovan and Radosevich, 1999; Toppino and Bloom, 2002; Cepeda et al., 2009).

Figure 1. (A) Typical spacing paradigm. (B) Spacing effects at different time scales. Average values from 187 studies (after Cepeda et al., 2006, Figure 6, modified). Local maxima of memory performance (accuracy) with certain combinations of spacing and retention intervals are indicated by dashed rectangles. Error bars represent one standard error of the mean. s = seconds; min = minutes; hr = hour.

An also important but rather little noted finding comes from Cepeda et al.'s meta-analysis (2006). To date, most of the studies about spacing effects compared different spacing intervals but kept the time between the last learning unit and a final test (“retention interval,” Figure 1A) constant. Comparisons between studies, however, indicate interdependence between the spacing interval and the retention interval: longer retention intervals are coupled with longer optimal spacing intervals (Bahrick and Phelps, 1987; Dempster, 1987).

Of note, another so far little noted finding is the wide range of spacing intervals from seconds to months (Cepeda et al., 2006). As Cepeda et al. (2006) nicely summarized, there is an interaction between spacing interval and retention interval, suggesting more than one optimal pair of spacing—and retention-values. Thus, a 3D-representation of the dimensions spacing interval, retention interval and memory performance seems to contain several maxima at different time scales (Figure 1B for a 2D visualization of the 3D parameter space).

Most models for the spacing effect are exclusively cognitive without addressing neurobiological aspects (for overviews see Dempster, 1996; Cepeda et al., 2006). In the present opinion paper we want to direct attention to significant parallels between findings at the cognitive level about spacing effects and related findings at the cellular level with synaptic plasticity.

There is a common agreement that learning and memory are neurally implemented by synaptic plasticity, i.e., a change of synaptic strength, resulting in an enhancement or a reduction of signal transmission between two neurons. Two most often discussed mechanisms of synaptic plasticity are long-term potentiation (LTP) and long-term depression (LTD).

LTD is a reduction of synaptic efficacy lasting for hours or longer. It can be induced either by transient strong or persistent weak synaptic stimulations. In protocols with repetitive paired pre- and postsynaptic stimulation the induction of LTD or its opposite LTP (see below) strongly depends on the stimulation frequency and on the order of pre- and postsynaptic stimulation (e.g., Dan and Poo, 2006).

LTP is an enhancement of a chemical synapse between two neurons, lasting from minutes to months or longer. It is typically induced by high frequency stimulation (“HFS”) or by stimulation protocols with simultaneous pre- and postsynaptic neural stimulation (e.g., Cooke and Bliss, 2006). After LTP induction less presynaptic activity is necessary to induce postsynaptic action potentials than before, i.e., the flow of information via this specific synapse is facilitated significantly.

Several features qualify LTP as a widely discussed cellular mechanism for learning and memory:

LTP has been found in animal cell slices (e.g., Lynch, 2003), in nearly all areas of the living mammalian brain (Lynch, 2004), including humans and human cell slices (Cooke and Bliss, 2006). LTP is found in different areas of the brain, like amygdala (Clugnet and LeDoux, 1990), hippocampus, cerebellum, and cortex (e.g., Malenka and Bear, 2004). Detailed LTP mechanisms differ between brain areas in a number of factors, like the contributing neurotransmitters, the intracellular molecular mechanisms and/or contributing membrane receptors, etc. (Malenka and Bear, 2004).

Three major LTP phases have been distinguished (e.g., Abraham, 2003):

Most important for any type of stimulation protocol is, that a certain level of postsynaptic depolarisation (excitatory postsynaptic polarisation, “EPSP”) has to be reached for LTP induction. Which LTP phase will be attained depends on the stimulation protocol. Typically, HFS protocols were used: Trains of 50–100 electrical pulses with a typical frequency of 100 Hz for a certain time interval (e.g., 1 s) are applied repetitive with spacing intervals without stimulation in between. Spacing intervals differ between studies (from 0.5 s to 10 min or even longer, e.g., Albensi et al., 2007).

Standard HFS protocols, however, are highly artificial and somewhat unphysiological, although recent studies indicate visual perceptual learning with typical LTP and LTD protocols (Normann et al., 2007; Beste et al., 2011; Aberg and Herzog, 2012). Interestingly, there is accumulating evidence for a dominating theta-to-alpha rhythm (5–12 Hz) in both the EEG (e.g., Grastyan et al., 1959) and the high-frequency hippocampal discharge bursts (e.g., Graves et al., 1990) of learning animals. Several studies even found more efficient LTP induction with more physiological theta/alpha stimulation train protocols compared to HFS protocols (Albensi et al., 2007). Further, trains of transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) in this frequency range can induce long-lasting changes in the human motor cortical output (Huang et al., 2005; Cooke and Bliss, 2006). Thus LTP can also be induced under physiological conditions.

In summary, the number of pulses, their frequency, the number of stimulation units, their duration and the duration of the spacing intervals between units can differ between studies and seem to be differentially efficient in both cellular LTP and behavioral learning. A number of similarities between LTP and learning on the behavioral level point to a possible aetiological association and are listed in Table 1.

Successful learning depends on several factors. Highly important are (1) the number of learning units and (2) the temporal distance (spacing intervals) between learning units (amongst other factors). The universality of the behavioral spacing effects and the parallels to spacing effects at the LTP level indicate that basic learning mechanisms are at work. Clearly LTP takes place at the level of synapses and molecules, whereas most findings form the spacing literature are from a complex behavioral/system level. Further, we do not know whether LTP induced by spaced stimulations directly contributes to the improved long-term memory seen after spaced studying at the behavioral level. However, the patterns described above suggest an intriguing correlation between synaptic and cognitive processes, worth to be investigated further. Comparison of optimal spacing values for learning tasks from different levels of cognition with optimal spacing intervals between LTP stimulation units may further elucidate the interrelation between low and high level learning in a systematic manner. Related results may help to deepen our understanding of basic learning mechanisms on one hand and provide simple, efficient, and universally applicable learning rules on the other hand.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Thanks for helpful comments and corrections to Harald Atmanspacher and Michael Bach.

Aberg, K. C., and Herzog, M. H. (2012). About similar characteristics of visual perceptual learning and LTP. Vis. Res. 61, 100–106.

Abraham, W. C. (2003). How long will long-term potentiation last? Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 358, 735–744.

Abraham, W. C., Logan, B., Greenwood, J. M., and Dragunow, M. (2002). Induction and experience-dependent consolidation of stable long-term potentiation lasting months in the hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 22, 9626–9634.

Albensi, B. C., Oliver, D. R., Toupin, J., and Odero, G. (2007). Electrical stimulation protocols for hippocampal synaptic plasticity and neuronal hyper-excitability: are they effective or relevant? Exp. Neurol. 204, 1–13.

Bahrick, H. P., and Phelps, E. (1987). Retention of Spanish vocabulary over 8 years. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 13, 344–349.

Balota, D. A., Duchek, J. M., and Paullin, R. (1989). Age-related differences in the impact of spacing, lag, and retention interval. Psychol. Aging 4, 3–9.

Beste, C., Wascher, E., Gunturkun, O., and Dinse, H. R. (2011). Improvement and impairment of visually guided behavior through LTP- and LTD-like exposure-based visual learning. Curr. Biol. 21, 876–882.

Braitenberg, V., and Schütz, A. (1998). Cortex: Statistics and Geometry of Neuronal Connectivity, 2nd Edn. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer.

Cepeda, N. J., Coburn, N., Rohrer, D., Wixted, J. T., Mozer, M. C., and Pashler, H. (2009). Optimizing distributed practice: theoretical analysis and practical implications. Exp. Psychol. 56, 236–246.

Cepeda, N. J., Pashler, H., Vul, E., Wixted, J. T., and Rohrer, D. (2006). Distributed practice in verbal recall tasks: a review and quantitative synthesis. Psychol. Bull. 132, 354–380.

Challis, B. H. (1993). Spacing effects on cued-memory tests depend on level of processing. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Learn. Mem. 19, 389–396.

Clugnet, M. C., and LeDoux, J. E. (1990). Synaptic plasticity in fear conditioning circuits: induction of LTP in the lateral nucleus of the amygdala by stimulation of the medial geniculate body. J. Neurosci. 10, 2818–2824.

Cooke, S. F., and Bliss, T. V. (2006). Plasticity in the human central nervous system. Brain 129, 1659–1673.

Dan, Y., and Poo, M. M. (2006). Spike timing-dependent plasticity: from synapse to perception. Physiol. Rev. 86, 1033–1048.

Dempster, F. N. (1987). Effects of variable encoding and spaced presentations on vocabulary learning. J. Educ. Psychol. 79, 162–170.

Dempster, F. N. (1996). “Distributing and managing the conditions of encoding and practice,” in, Handbook of Perception and Cognition, Vol. 10, eds E. L. Bjork and R. A. Bjork (New York, NY: Academic Press).

Donovan, J. J., and Radosevich, D. J. (1999). A meta-analytic review of the distribution of practice effect. J. Appl. Psychol. 84, 795–805.

Ebbinghaus, H. (1913). Memory, Trans. H. A. Ruger and C. E. Bussenius. New York, NY: Teachers College.

Grastyan, E., Lissak, K., Madarasz, I., and Donhoffer, H. (1959). Hippocampal electrical activity during the development of conditioned reflexes. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 11, 409–430.

Graves, A. B., White, E., Koepsell, T. D., Reifler, B. V., van Belle, G., Larson, E. B., and Raskind, M. (1990). The association between head trauma and Alzheimer's disease. Am. J. Epidemiol. 131, 491–501.

Huang, Y. Y., and Kandel, E. R. (1994). Recruitment of long-lasting and protein kinase A-dependent long-term potentiation in the CA1 region of hippocampus requires repeated tetanization. Learn. Mem. 1, 74–82.

Huang, Y. Z., Edwards, M. J., Rounis, E., Bhatia, K. P., and Rothwell, J. C. (2005). Theta burst stimulation of the human motor cortex. Neuron 45, 201–206.

Janiszewski, C., Noel, H., and Sawyer, A. G. (2003). A meta-analysis of spacing effect in verbal learning: implications for research on advertising repetition and consumer memory. J. Consum. Res. 30, 138–149.

Kahana, M. J., and Howard, M. W. (2005). Spacing and lag effects in free recall of pure lists. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 12, 159–164.

Lattal, K. M. (1999). Trial and intertrial durations in Pavlovian conditioning: issues of learning and performance. J. Exp. Psychol. 25, 433–450.

Litman, L., and Davachi, L. (2010). Distributed learning enhances relational memory consolidation. Learn. Mem. 15, 711–716.

Lynch, G. (2003). Long-term potentiation in the Eocene. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 358, 625–628.

Mauelshagen, J., Sherff, C. M., and Carew, T. J. (1998). Differential induction of long-term synaptic facilitation by spaced and massed applications of serotonin at sensory neuron synapses of Aplysia californica. Learn. Mem. 5, 246–256.

Melton, A. W. (1970). Teh situation with respect to the spacing of repetitions and memory. J. Verbal Learn. Verbal Behav. 9, 596–606.

Normann, C., Schmitz, D., Furmaier, A., Doing, C., and Bach, M. (2007). Long-term plasticity of visually evoked potentials in humans is altered in major depression. Biol. Psychiatry 62, 373–380.

Racine, R. J., Chapman, C. A., Trepel, C., Teskey, G. C., and Milgram, N. W. (1995). Post-activation potentiation in the neocortex. IV. Multiple sessions required for induction of long-term potentiation in the chronic preparation. Brain Res. 702, 87–93.

Raymond, C. R. (2007). LTP forms 1, 2 and 3, different mechanisms for the “long” in long-term potentiation. Trends Neurosci. 30, 167–175.

Rea, C. P., and Modigliani, V. (1987). The spacing effect in 4- to 9-year-old children. Mem. Cogn. 15, 436–443.

Roediger, H. L., and III, Karpicke, J. D. (2006). The power of testing memory. Basic research and Implications for educational practice. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 1, 181–210.

Scharf, M. T., Woo, N. H., Lattal, K. M., Young, J. Z., Nguyen, P. V., and Abel, T. (2002). Protein synthesis is required for the enhancement of long-term potentiation and long-term memory by spaced training. J. Neurophysiol. 87, 2770–2777.

Toppino, T. C. (1991). The spacing effect in young children's free recall: support for automatic-process explanations. Mem. Cogn. 19, 159–167.

Toppino, T. C., and Bloom, L. C. (2002). The spacing effect, free recall, and two-process theory: a closer look. J. Exp. Psychol. 28, 437–444.

Toppino, T. C., Hara, Y., and Hackman, J. (2002). The spacing effect in the free recall of homogeneous lists: present and accounted for. Mem. Cogn. 30, 601–606.

Yin, J. C., Del Vecchio, M., Zhou, H., and Tully, T. (1995). CREB as a memory modulator: induced expression of a dCREB2 activator isoform enhances long-term memory in Drosophila. Cell 81, 107–115.

Keywords: spacing effect, memory, learning, synaptic plasticity, long term potentiation (LTP)

Citation: Kornmeier J and Sosic-Vasic Z (2012) Parallels between spacing effects during behavioral and cellular learning. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 6:203. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2012.00203

Received: 23 May 2012; Accepted: 20 June 2012;

Published online: 06 July 2012.

Edited by:

John J. Foxe, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, USAReviewed by:

Michael Herzog, École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, SwitzerlandCopyright © 2012 Kornmeier and Sosic-Vasic. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits use, distribution and reproduction in other forums, provided the original authors and source are credited and subject to any copyright notices concerning any third-party graphics etc.

*Correspondence: Jürgen Kornmeier, Institute for Frontier Areas of Psychology and Mental Health, Wilhelmstraße 3a, 79098 Freiburg, Germany. e-mail:a29ybm1laWVyQGlncHAuZGU=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.