94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Neurol., 08 December 2023

Sec. Multiple Sclerosis and Neuroimmunology

Volume 14 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2023.1326738

This article is part of the Research TopicThe contribution of epigenetic and environmental factors in determining disease severity in MSView all articles

Qin Ma1

Qin Ma1 Danillo G. Augusto2

Danillo G. Augusto2 Gonzalo Montero-Martin3,4,5

Gonzalo Montero-Martin3,4,5 Stacy J. Caillier1

Stacy J. Caillier1 Kazutoyo Osoegawa3

Kazutoyo Osoegawa3 Bruce A. C. Cree1

Bruce A. C. Cree1 Stephen L. Hauser1

Stephen L. Hauser1 Alessandro Didonna6

Alessandro Didonna6 Jill A. Hollenbach1

Jill A. Hollenbach1 Paul J. Norman7

Paul J. Norman7 Marcelo Fernandez-Vina3,4

Marcelo Fernandez-Vina3,4 Jorge R. Oksenberg1*

Jorge R. Oksenberg1*Background: The HLA-DRB1 gene in the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) region in chromosome 6p21 is the strongest genetic factor identified as influencing multiple sclerosis (MS) susceptibility. DNA methylation changes associated with MS have been consistently detected at the MHC region. However, understanding the full scope of epigenetic regulations of the MHC remains incomplete, due in part to the limited coverage of this region by standard whole genome bisulfite sequencing or array-based methods.

Methods: We developed and validated an MHC capture protocol coupled with bisulfite sequencing and conducted a comprehensive analysis of the MHC methylation landscape in blood samples from 147 treatment naïve MS study participants and 129 healthy controls.

Results: We identified 132 differentially methylated region (DMRs) within MHC region associated with disease status. The DMRs overlapped with established MS risk loci. Integration of the MHC methylome with human leukocyte antigen (HLA) genetic data indicate that the methylation changes are significantly associated with HLA genotypes. Using DNA methylation quantitative trait loci (mQTL) mapping and the causal inference test (CIT), we identified 643 cis-mQTL-DMRs paired associations, including 71 DMRs possibly mediating causal relationships between 55 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and MS risk.

Results: The results describe MS-associated methylation changes in MHC region and highlight the association between HLA genotypes and methylation changes. Results from the mQTL and CIT analyses provide evidence linking MHC region variations, methylation changes, and disease risk for MS.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic, immune-mediated disease of the central nervous system and common cause of neurological disability in young adults. A substantial body of epidemiologic and experimental research describes the heritable components of MS, including the identification of 233 independent genome-wide risk associations (1). The strongest association maps to the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) region (chr6:28,510,180-33,532,223), accounting in some models for up to 20% of the underlying disease susceptibility. The MHC is a remarkably gene-dense region of the human genome, and 32 out of the 233 independent MS risk associations were identified across the extended locus (1). The main susceptibility signal arises from the HLA-DRB1 gene in the class II segment of the locus and HLA-DRB1*15:01 bearing haplotypes carry an average odds ratio risk of 3.08 that doubles for HLA-DRB1*15:01 homozygous genotypes (2). Additional HLA susceptibility alleles and haplotypes were identified as well as independent protective signals in the telomeric class I region of the locus (3–7).

HLA-encoded molecules are cell surface glycoproteins whose primary role in an immune response is to display and present short antigenic peptide fragments to T cells through specific receptors. Thus, antigen affinity and specificity determined by allelic sequence variation are considered the primary mediators of disease susceptibility. However, HLA expression levels are also important for T cell recognition, hence suggesting a role for epigenetic regulation, as an additional mediator of susceptibility in MS (8–10) and other autoimmune diseases (11–13). Among the different epigenetic signatures, DNA methylation is the best characterized epigenetic modification affecting gene regulation (14). However, due to its architectural complexity, standard whole genome bisulfite sequencing protocols or targeted arrays are inadequate to resolve the methylation landscape of the MHC locus with sufficient specificity and resolution. We utilized a set of validated capture probes to achieve high-throughput and high-resolution sequencing of the entire MHC and combined with bisulfite sequencing to conduct a comprehensive analysis of MHC methylation patterns in blood samples from treatment naïve MS participants and matched healthy controls.

Peripheral blood was sampled by venipuncture from 147 MS participants and 129 healthy controls recruited at the UCSF MS Center as part of the UCSF multiple sclerosis EPIC and ORIGINS studies (15). All MS participants were treatment naive (i.e., no glucocorticoids or disease-modifying MS therapy at any time prior to blood draw) and met clinical and radiographic diagnostic criteria for relapsing–remitting MS (RRMS). Eighty percent of cases were females, the mean age at sample collection was 43 (range from 18 to 65), and the mean Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) was 1.5 (range from 0 to 6.5). Healthy controls were sex and age matched (mean age: 43, range: 24-61), and reported no history of autoimmune disease. All study participants were of white-western European ancestry. The study was approved by the UCSF Institutional Review Board, and informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood using a standard salting-out method. An MHC-targeted bisulfite sequencing (BS-seq) approach was applied to generate base-resolution MHC methylome maps. Briefly, 500 ng genomic DNA was fragmented, end-repaired, A-tailed, and ligated to methylated adaptors. The ligated samples were pooled together to perform MHC capture using validated capture probes (16) and a custom targeted panel from Twist Bioscience following the target enrichment standard hybridization protocol (Twist Bioscience). The pooled fragments were then bisulfite converted using the EZ DNA Methylation Gold kit (Zymo Research) at 64°C for 2.5 h and amplified using the KAPA HiFi HotStart Uracil+ ReadyMix PCR Kit. Libraries were sequenced on HiSeq X 10 platform (Illumina). The sequencing reads were analyzed following an established bioinformatics pipeline. After filtering out low quality reads, the remaining paired reads were uniquely mapped to the reference genome (hg38, UCSC) using Bismark software with parameters: -N 1 -X 1000 --score_min L,0,-0.6. The bisulfite conversion rates were calculated using the lambda DNA. Subsequently, the 5mC level at each CpG site was computed as described. The number of “C” bases from the sequencing reads were counted as methylated (denoted as NC) and the number of “T” bases as unmodified (denoted as NT). The methylation levels were then estimated as NC/ (NC + NT). While previous array-based methods have less than 20% coverage on MHC region, our method can cover ~95% of the locus.

DNA samples were processed for typing all alleles at the 11 classical HLA loci (HLA-A, -C, -B, -DRB3, -DRB4, -DRB5, -DRB1, -DQA1, -DQB1, -DPA1, and -DPB1) using MIA FORA NGS MFLEX HLA Typing Kits (Immucor Inc.) and sequenced using MiniSeq DNA sequencers (Illumina) as described (17). The MIA FORA 5.1 software with IPD-IMGT/HLA Database release version 3.44.0 was used for DNA sequence assembly and HLA genotype assignments.

The metilene package (18) (version 0.2-8) was used to call the differentially methylated regions (DMRs), including only CpGs with at least 3× in coverage. DMRs were defined to have a 5% minimum absolute mean methylation difference, with a maximum distance of 1,000 nt between CpGs within a DMR and a minimum of 3 CpGs per DMR (parameter –M 1000 –m 3 –d 0.1). The Genomic Regions Enrichment of Annotations Tool (GREAT) (19) was employed to predict the DMR functional significance.

The correlations between HLA genotypes and methylation levels on DMRs were tested by ANOVA test in R. The differences in methylation levels between two groups were assessed with the Student’s t-test. The differences in the proportion of the HLA genotypes between two groups were assessed by Fisher’s exact test. Permutation test was performed to estimate the significance of the enrichment of DMRs in the ENCODE Encyclopedia Registry of candidate cis-Regulatory Elements (cCREs) (20). The BEDTools intersectBed function was used to get the overlap between the cCREs and DMRs. To test the statistical significance, the peaks were randomly permuted 1,000 times among human genome by BEDTools shuffleBed function, while retaining the length of each peak to assess the distribution of background overlap.

We used MatrixEQTL (21) to identify cis DNA methylation quantitative trait loci (cis-mQTL) in the ±500 kb genomic region flanking the DMRs. SNPs were pruned and selected using PLINK as those satisfying pairwise correlation R2 < 0.5 in a 250,000 bp window, with a window stride of 25,000 bp. Linear regression analysis was performed between the average methylation level of each DMR, and genotype encoded as 0, 1, or 2 copies of the reference allele in cis (±500 kb) of each DMR, accounting for the effects of age and sex. False discovery rate (FDR) was controlled follow the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure.

The causal inference test (CIT) (22) was used to test for mediation of a known causal association between a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP), and disease status putatively mediated by DNA methylation. Briefly, if we let S denote the SNP genotype, D denote the disease status, and M denote the potential mediator, DNA methylation, then the four component conditions are, (1) S and M are associated, (2) S and D are associated, (3) S is associated with M|D, and (4) S is independent of D|M. Test 4 requires an equivalence test and is implemented using a permutation based approach. A likelihood-based hypothesis testing approach is implemented for assessing causal mediation. The CIT was performed for the identified meQTL-DMR pairs using SNP information, DNA methylation level, and MS status from all subjects. One hundred permutations were performed to generate permutation-based FDR values to quantify uncertainty in the estimate. The permutations were specified the same for all tests to accurately account for dependencies among the tests. Permutation-based FDR values at or under 5% were used as cut off for significance.

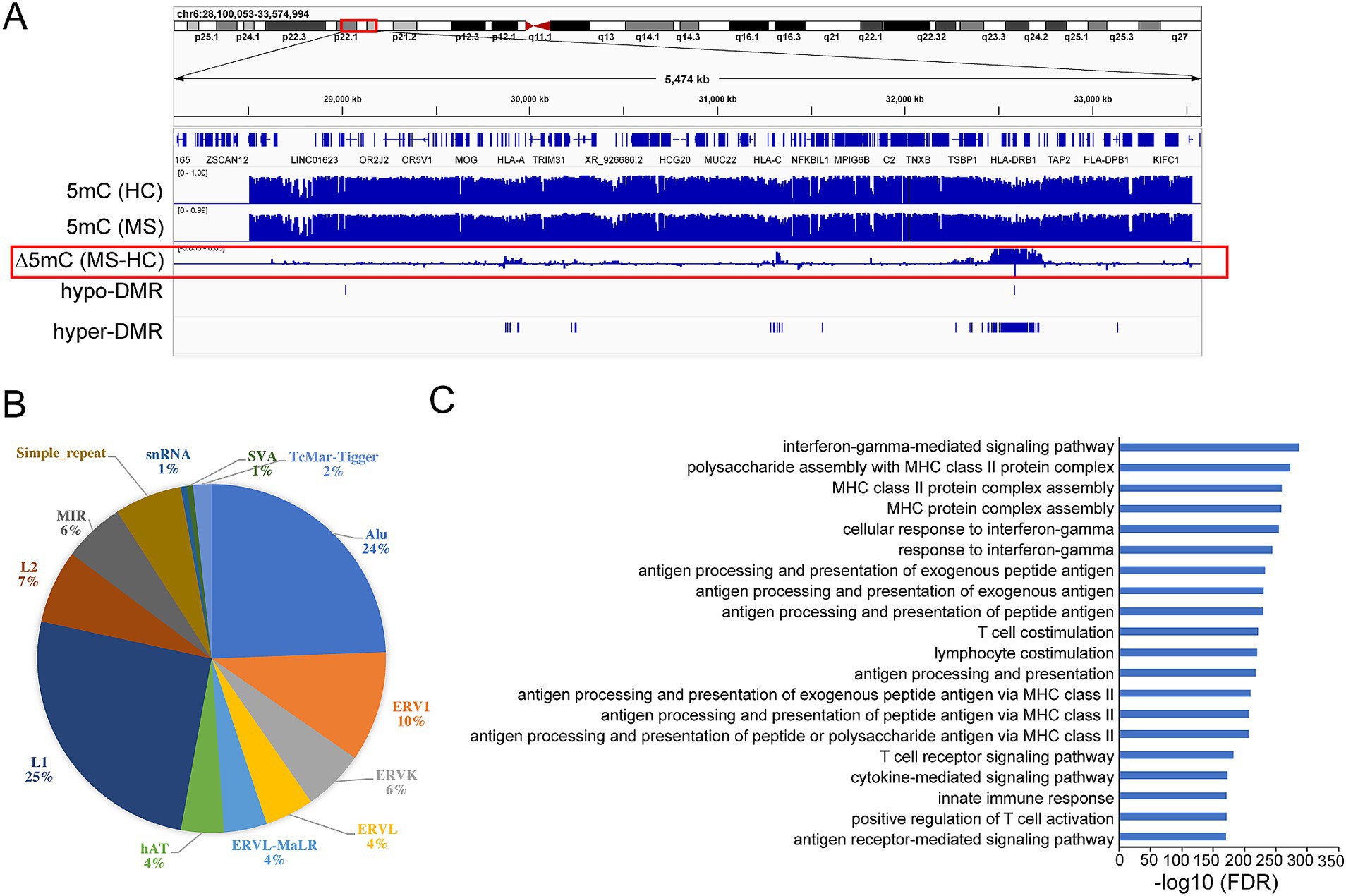

We generated base-resolution MHC (chr6: 28510180-33532223) methylome maps for 147 treatment naïve MS participants and 129 sex/age/ancestry matched healthy controls using targeted bisulfite sequencing. We then compared the methylome profiles between MS and controls to single out MS-associated methylation signatures, identifying 132 significant MHC DMRs (p-value <0.05, greater than 5% methylation difference): 3 DMRs were hypo-methylated and 129 DMRs were hyper-methylated compared to controls (Figure 1A) (Supplementary Table S1). Among the 132 DMRs, 41 hyper-DMRs and 1 hypo-DMR are significantly detected with FDR < 0.05 (Table 1), the latest covering exon 2 and extending into intron 1 of HLA-DRB1, predicted to function as a poised/active promoter and distal enhancer (Supplementary Figures S1A,B). Notably, 31 of the 32 100-kb regions around the established MS variants (1) overlap with the DMRs (Supplementary Table S2), whereas 81% concentrate within the HLA-class II region (Figure 1A) (Supplementary Table S1). One hundred and eight DMRs (82%) overlapped with repetitive elements (Supplementary Table S3). Most of them fall within the LINE-1 (L1) and Alu elements (25% and 24% of DMRs respectively) (Figure 1B). Seventeen DMRs coincide with or locate near non-HLA genes including TSBP1, HCG24, HCP5B, LINC02571, LOC101929163, MIR6891, NFKBIL1, TRIM26, and ZNF311 (Supplementary Table S1). To gain additional insights into the regulatory function of the DMRs, we examined the enrichment in the ENCODE Encyclopedia Registry of candidate cis-Regulatory Elements (cCREs). The DMRs were significantly enriched in proximal enhancer-like signatures (fold change = 5.78, p = 0.002) and H3K4me3 peak regions (fold change = 3.94, p = 0.001). H3K4me3 is highly enriched at active promoters. The data indicate that DMRs are enriched in regulatory regions, especially in enhancer and promoter signals.

Figure 1. DNA methylation changes within MHC region in multiple sclerosis (MS) patients compared to healthy controls (HC). (A) Graphical representation of methylation (5mC) pattern within MHC region. ∆5mC highlighted in red box represents the methylation difference between MS and HC. (B) Pie diagram showing percentage of DMRs overlapping with different families of repetitive elements. (C) Functional annotation of the DMRs by GREAT. FDR: false discovery rate.

The Genomic Regions Enrichment of Annotations Tool (GREAT) was applied to capture the biological functions associated with the DMRs (p-value <0.05). Gene ontology (GO) analysis on the genes overlapping with or located near DMRs indicated, unsurprisingly, an enrichment in immune related pathways, including interferon-gamma, MHC protein complex assembly, antigen processing, and presentation related pathways (Figure 1C).

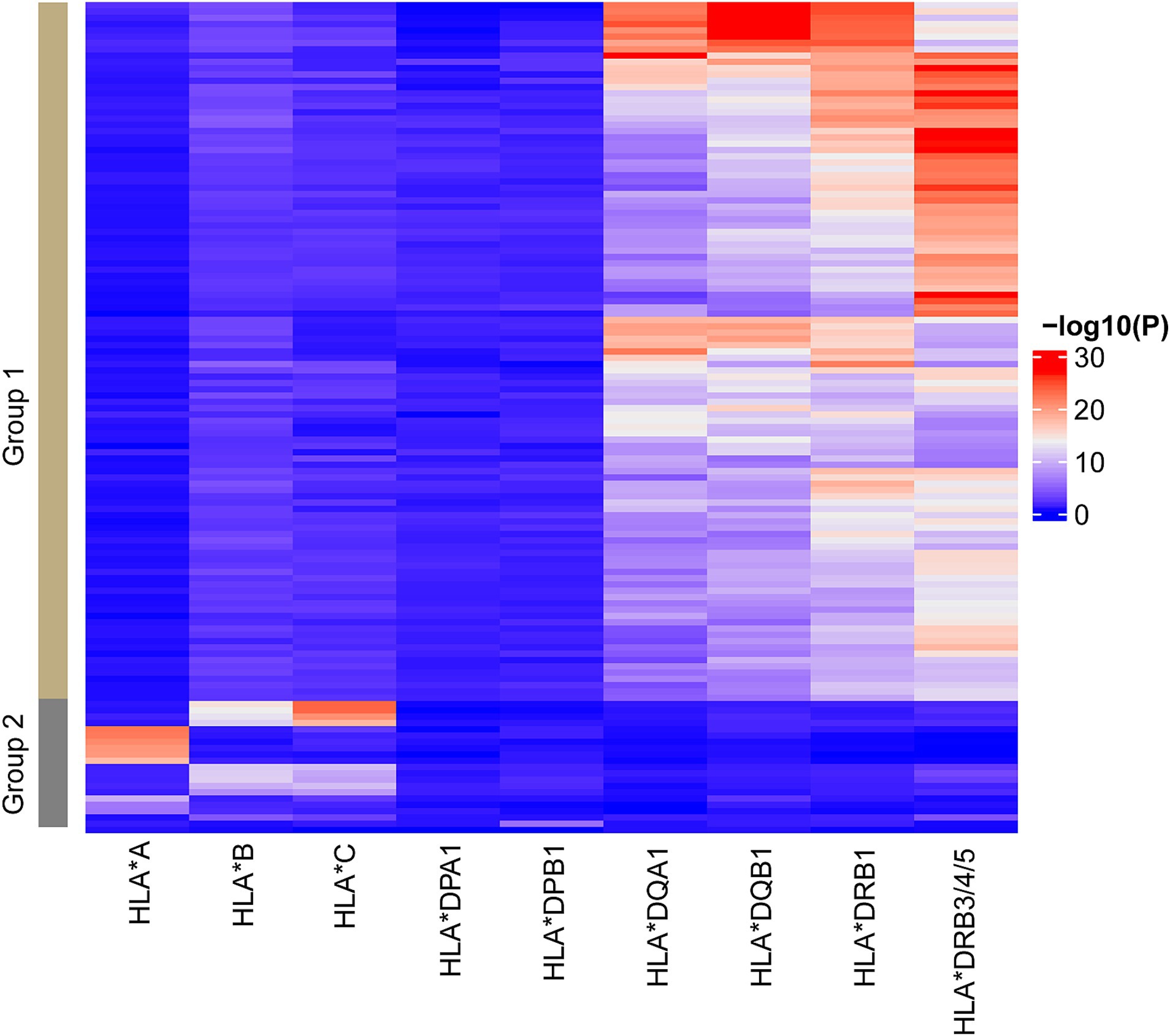

Given the concentration of DMRs in the HLA-class II region, we sought to address the association between HLA genotypes and MS-associated DNA methylation changes. All study participants were genotyped for the 11 classical HLA loci (HLA-A, -B, -C, -DRB3, -DRB4, -DRB5, -DRB1, -DQA1, -DQB1, -DPA1, and-DPB1), revealing significant associations between genotypes and DMR methylation levels (Figure 2 and Supplementary Table S4), specifically 9, 9, 1, and 112 DMRs (p-value <0.05) correlate HLA-A, HLA-B/C, HLA-DPB1 and HLA-DQA1/DQB1/DRB1/DRB3/4/5 genotypes, respectively (Figure 2 and Supplementary Table S4). DMRs clearly segregate into two main clusters, suggesting independent associations with class I and class II genotypes (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The corrections between HLA genotypes and DMRs. Heatmap representing the correlations between HLA genotypes clustered by classical HLA genes and the DMR methylation. The significances of the correlations are colored from blue to red to indicate low to high. The columns represent the HLA genotypes while the rows represent the DMRs. Two main groups of DMRs associated with HLA class I and class II genotypes, respectively, are labeled with group 1 and 2. Similar patterns were identified when separating cases and controls.

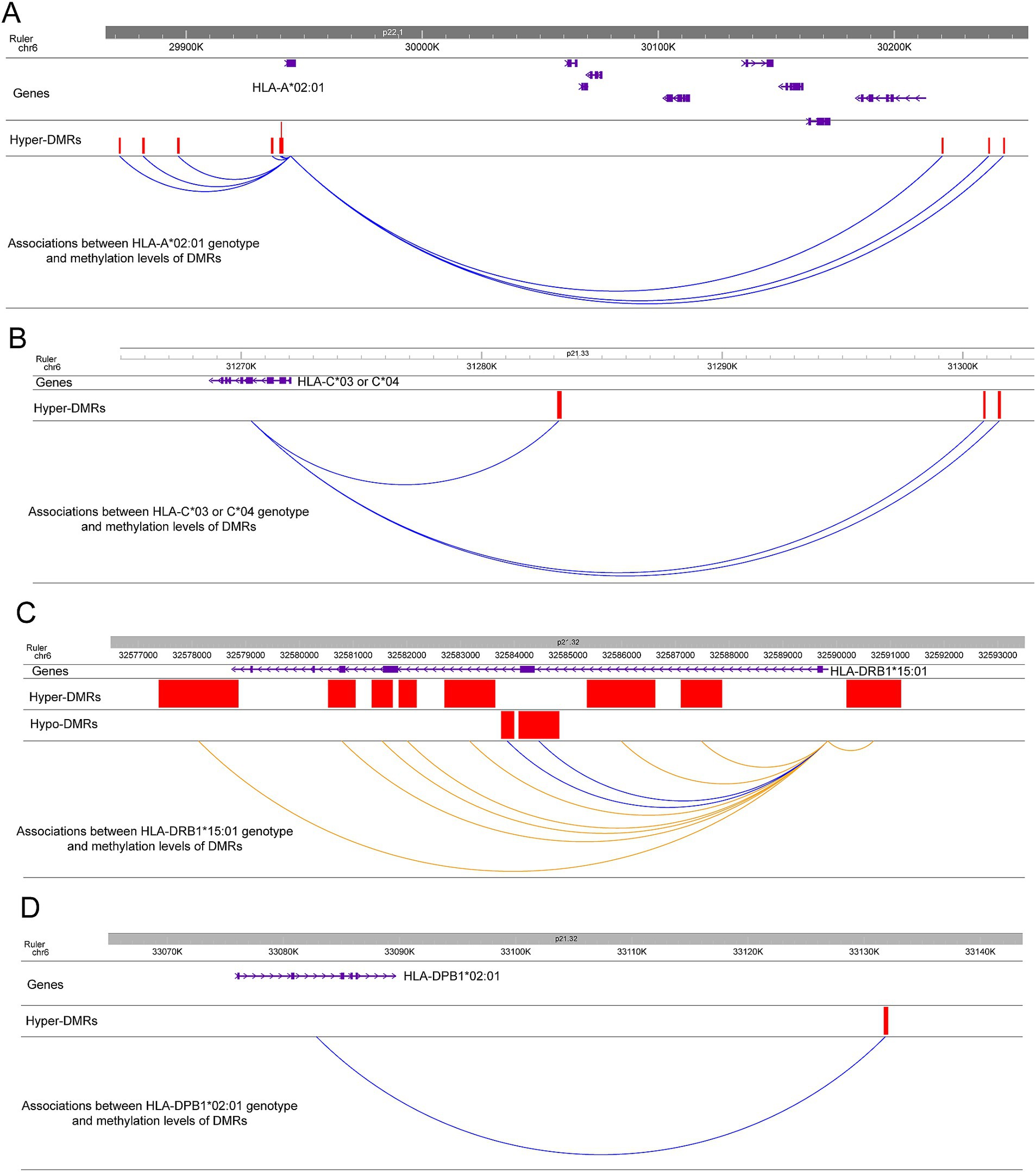

In agreement with previous studies showing that the HLA-A*02:01 genotype has a moderately protective effect in MS (7, 17), the frequency of HLA-A*02:01 is lower in cases compared to controls (30.07% vs. 44.19%, p = 0.017). Interestingly, HLA-A*02:01 carriers show significantly lower methylation levels on the 9 associated hyper-DMRs compared to non-carriers (Figure 3A and Supplementary Figure S2A) with clear dose response to 0, 1, or 2 copies of the allele. Similarly, individuals with the moderately protective HLA-C*03 or HLA-C*04 genotypes (37.06% cases vs. 47.29% controls, p = 0.1) have significantly lower methylation levels on 3 hyper-DMRs near the gene compared to non-carriers (Figure 3B and Supplementary Figure S2B).

Figure 3. Associations between HLA genotypes and methylation levels of DMRs near or at the genes. (A) Associations between HLA-A*02:01 genotype and methylation levels of 9 hyper-DMRs near the gene. The correlations are colored by blue to indicate the HLA-A*02:01 carriers show lower methylation levels on the 9 hyper-DMRs compared to non-carriers. The positions of the DMRs and the gene are also depicted. (B) Associations between HLA-C*03 or HLA-C*04 genotype and methylation levels of 3 hyper-DMRs near the gene. The correlations are colored by blue to indicate the HLA-C*03 or HLA-C*04 carriers show lower methylation levels on the 3 hyper-DMRs compared to non-carriers. The positions of the DMRs and the gene are also depicted. (C) Associations between HLA-DRB1*15*01 genotype and methylation levels of 10 DMRs at the gene. Blue colored correlations indicate the HLA-DRB1*15*01 carriers show lower methylation levels on the 2 hypo-DMRs compared to non-carriers. Orange colored correlations indicate the HLA-DRB1*15*01 carriers show higher methylation levels on the 8 hyper-DMRs compared to non-carriers. The positions of the DMRs and the gene are also depicted. (D) Associations between HLA-DPB1*02:01 genotype and methylation levels of 1 hyper-DMR near the gene. The correlation is colored by blue to indicate the HLA-DPB1*02:01 carriers show lower methylation levels on the hyper-DMR compared to non-carriers. The positions of the DMR and the gene are also depicted.

We next analyzed the correlations between HLA-DRB1 genotypes and methylation levels of 10 DMRs (2 hypo-DMRs, 8 hyper-DMRs) located in the gene (Figure 3C). In this dataset, the frequency of HLA-DRB1*15:01 was significantly higher in MS participants compared to healthy controls, as expected (44.76% vs. 21.71%, p = 2.491e-06). HLA-DRB1*15:01 carriers showed significantly higher methylation levels on 8 hyper-DMRs (Figure 3C and Supplementary Figure S2C) and lower methylation levels on 2 hypo-DMRs compared to non-carriers (Figure 3C and Supplementary Figure S2C). Also in the class II region, the frequency of HLA-DPB1*02:01 was significantly lower in MS participants compared to healthy controls (16.79% vs. 30.95%, p = 0.009). When analyzing the correlation between methylation levels of DMRs and HLA-DPB1 genotypes, we found that the individuals with the HLA-DPB1*02:01 genotype have significantly lower methylation levels on one hyper-DMR 42-kb downstream of HLA-DPB1 gene compared to non-carriers (Figure 3D and Supplementary Figure S2D).

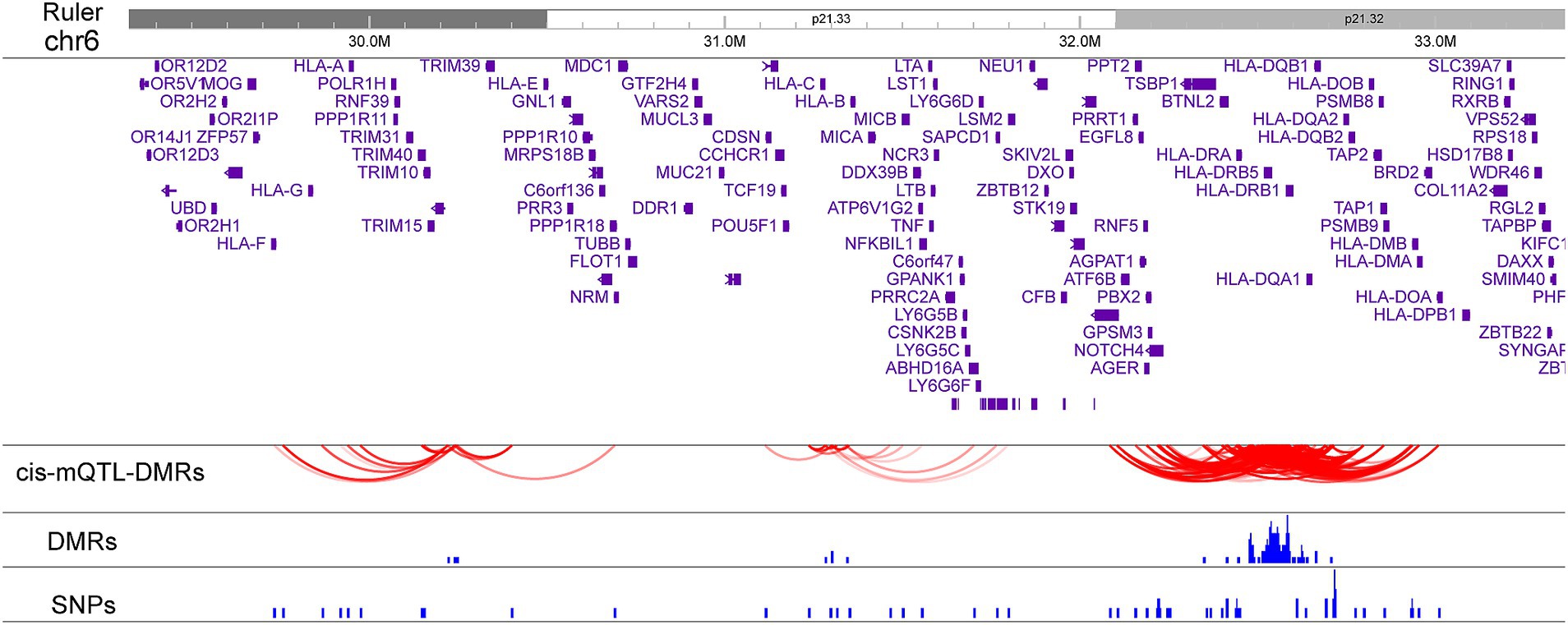

Statistical associations between the DMRs methylation levels and SNPs (linkage disequilibrium R2 < 0.5) located within 500 kb up/downstream of each DMR were tested in the dataset. A total of 8,348 cis-mQTL-DMR paired associations from 485 unique SNPs and 132 DMRs were identified with FDR < 0.05. Causal inference test (CIT) analysis was performed to assess whether DNA methylation directly mediates the relationship between the genetic variants and disease phenotype. Among the 8,348 pairs, 643 cis-mQTL-DMR paired associations were significant (Supplementary Table S5). These 643 cis-mQTL-DMR paired include 55 unique SNPs and 71 unique DMRs. Notably, 46 of the 55 SNPs were associated with MS susceptibility with nominal significance (p < 0.05) in the recent MS GWAS study while 25 of the 55 SNPs are in linkage disequilibrium (LD) (R2 > 0.1) with 8 independent genome-wide significant associations (1) (Supplementary Table S6). In the class I region, rs2156875, a SNP in LD with MS genome-wide significant association rs2523500, behaves as a cis-mQTL affecting the DMR methylation levels in chr6: 31301483-31301548 (Supplementary Figure S3). The MHC class II region contained a high density of cis-DMR-mQTL pairs, with 34 unique SNPs and 64 unique DMRs (Figure 4). Three DMRs near HLA-C, LINC02571, and MIR6891 genes are associated with 11 SNPs located within or near C6orf15, HLA-C, MICB, LINC02571, HCP5, MIR4646, MIR6891, VARS, SAPCD1-AS1, and NFKBIL1 (Figure 4). Another three DMRs located at or near TRIM26 and HLA-L are associated with 10 SNPs located within or near HCG4B, HCG9, HCP5B, HLA-A, HLA-F, IFITM4P, NRM, RPP21, TRIM10, and TRIM40 (Figure 4).

Figure 4. cis-mQTLs associated with MS DMR methylation levels. The plot displays paired associations between cis-mQTLs and DMRs. The positions of the DMRs and SNPs are also depicted.

A long-standing literature suggests that abnormal regulation and expression of HLA genes relates to autoimmune disease risk and phenotype including MS, conceivably operating through enhanced antigen presentation and secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines (23–25). In the present study, base-resolution blood DNA methylation maps of the MHC generated for 147 treatment naïve MS patients and 129 healthy controls by targeted bisulfite sequencing, found significant MS-associated methylation changes that correlate with HLA genotypes. The effect of DNA methylation on gene expression depends on the genomic contexts: transcriptional start sites, regulatory elements, gene bodies, and repeat sequences. Nearly half the identified DMRs overlap with the retrotransposons L1 and Alu elements. Aberrant DNA methylation of interspersed repetitive sequences such as L1 and Alu have been linked to cancer, autoimmunity, and psychiatric diseases (26–29). Important gaps remain in understanding the mechanisms underlying these associations that are conceivably related to the abnormal regulation of neighboring genes. Several studies demonstrated that L1 and Alu elements can regulate the expression of HLA genes and other immune-related genes (30–32). Collectively, these findings support the importance of DNA methylation changes in repetitive elements driving the abnormal regulation of HLA in MS.

The well-established HLA-DRB1*15:01 risk genotype is associated with higher methylation levels on 8 DMRs and lower methylation levels on 2 DMRs across the gene. Notably, the hypomethylated sites map to the most variable exon 2, consistent with a recent report employing the Illumina array-based methodology showing HLA-DRB1*15:01 exon 2 hypomethylation in MS (9). The associations between HLA-DRB1*15:01 genotype and 8 hyper-DMRs have not been reported by previous studies (8, 9, 33). Classically, DNA methylation is negatively associated with gene expression. However, DNA hypermethylation can be also associated with upregulation of gene expression (34, 35). The presence of both hyper-and hypomethylated sites within a single gene, in this case HLA-DRB1 reflects a complex, genomic context dependent cumulative regulation.

With limited coverage on the MHC region, previous array-based methods consistently reported the DMRs at HLA-DRB1 (8, 9, 33). Here, using MHC-targeted BS-seq based method, we were also able to identify an array of DMRs at the MHC class I region and further integrate with HLA genetic data. HLA-A allelic diversity is linked to differences in levels of gene expression due in part to differential methylation patterns (36). Here we found lower methylation levels in 9 DMRs in HLA-A*02:01, an allele consistently associated with MS resistance (5, 7, 37). Interestingly, HLA-A*02:01 and HLA-DRB1*15:01 were, respectively, associated with lower and higher Epstein Barr Virus (EBV) viral load (38), broadly considered a trigger for the development of MS (39), prompting us to suggest a key role for epigenetic regulation of MHC expression in the initiation of MS. Additionally, the 3 hypermethylated sites associated with HLA-C*03 or HLA-C*04 may affect the interaction with killer cell immunoglobulin receptors (KIRs) and of natural killer (NK) cell activity (40–42). Finally, MS GWAS identified two statistically independent effects associated with the HLA-DPB1 gene (1). We report here the higher methylation in 1 DMR is related to lower frequency of HLA-DPB1*02:01 genotype in MS, an allele associated in some studies with disease protection (43). Larger and ancestrally-diverse studies will be required to assess the DMRs associations with other HLA MS-relevant alleles (44–47).

Genetic variations can regulate DNA methylation patterns. We identified 485 cis-mQTLs associated with 132 DMRs. The CIT testing supported causal relationships between 55 genetic variants and MS disease status, with the majority residing in the MHC class II region, mediated by DNA methylation on 71 DMRs. In agreement with MHC region hosts the strongest MS associations, most of the mQTLs involved in the causal mediation relationships are significantly associated with MS. Our analysis shows that DNA methylation levels can mediate MS genetic risk within the MHC, especially the MHC class II region, consistent with previous studies employing the Illumina array-based methodology showing DNA methylation can mediate the genetic risk within MHC in MS (9).

In the present study we also identified 17 DMRs located in or near non-HLA genes. Among them, one DMR located telomeric of DRB1, in intron two of NF-kB inhibitor like 1 (NFKBIL1), a nominated susceptibility gene for MS (1). NFKBIL1 is involved in mRNA processing (48, 49), and the alternative splicing of both human immune-related and viral genes (48). The observed hypermethylation of NFKB1L1 in the MS genome and HLA-independent susceptibility effects (1) provide a steppingstone for mechanistic studies of a key component of the inflammatory response. The understanding of how epigenetic regulation is functionally linked to MS initiation and progression may provide novel diagnostic, prognostic, and intervention opportunities.

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The name of the repository and accession number can be found at: National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/, GSE235106.

The studies involving humans were approved by UCSF Institutional Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

QM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DA: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. GM-M: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. SC: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. KO: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. BC: Resources, Writing – review & editing. SH: Funding acquisition, Resources, Writing – review & editing. AD: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. JH: Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition. PN: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. MF-V: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. JO: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by grants from the National Institute of Health R01NS128277 (JO), National Institutes of Health R01AI169070 (JH), and the Valhalla Foundation (SH). QM is supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the National Multiple Sclerosis Society (FG-2108-38348). The UCSF DNA biorepository is supported by grant RG-1611-26299 (JO) from the National Multiple Sclerosis Society. The authors acknowledge the contributions of the MS-EPIC team for the recruitment of study participants, Rosa Guerrero for sample processing, Adam Santaniello and Adam Renschen for assistance with data management.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2023.1326738/full#supplementary-material

1. International Multiple Sclerosis Genetics Consortium. Multiple sclerosis genomic map implicates peripheral immune cells and microglia in susceptibility. Science. (1979) 2019:365. doi: 10.1126/science.aav7188

2. Sawcer, S, Hellenthal, G, Pirinen, M, Spencer, CC, Patsopoulos, NA, Moutsianas, L, et al. Genetic risk and a primary role for cell-mediated immune mechanisms in multiple sclerosis. Nature. (2011) 476:214–9. doi: 10.1038/nature10251

3. Barcellos, LF, Sawcer, S, Ramsay, PP, Baranzini, SE, Thomson, G, Briggs, F, et al. Heterogeneity at the HLA-DRB1 locus and risk for multiple sclerosis. Hum Mol Genet. (2006) 15:2813–24. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl223

4. Yeo, TW, De Jager, PL, Gregory, SG, Barcellos, LF, Walton, A, Goris, A, et al. A second major histocompatibility complex susceptibility locus for multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. (2007) 61:228–36. doi: 10.1002/ana.21063

5. Brynedal, B, Duvefelt, K, Jonasdottir, G, Roos, IM, Åkesson, E, Palmgren, J, et al. HLA-A confers an HLA-DRB1 independent influence on the risk of multiple sclerosis. PLoS One. (2007) 2:e664. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000664

6. Lincoln, MR, Ramagopalan, SV, Chao, MJ, Herrera, BM, Deluca, GC, Orton, SM, et al. Epistasis among HLA-DRB1, HLA-DQA1, and HLA-DQB1 loci determines multiple sclerosis susceptibility. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. (2009) 106:7542–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812664106

7. Mack, SJ, Udell, J, Cohen, F, Osoegawa, K, Hawbecker, SK, Noonan, DA, et al. High resolution HLA analysis reveals independent class I haplotypes and amino-acid motifs protective for multiple sclerosis. Genes Immun. (2019) 20:308–26. doi: 10.1038/s41435-017-0006-8

8. Graves, MC, Benton, M, Lea, RA, Boyle, M, Tajouri, L, Macartney-Coxson, D, et al. Methylation differences at the HLA-DRB1 locus in CD4+ T-cells are associated with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler J. (2014) 20:1033–41. doi: 10.1177/1352458513516529

9. Kular, L, Liu, Y, Ruhrmann, S, Zheleznyakova, G, Marabita, F, Gomez-Cabrero, D, et al. DNA methylation as a mediator of HLA-DRB1 15:01 and a protective variant in multiple sclerosis. Nat Commun. (2018) 9:2397. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04732-5

10. Kalomoiri, M, Prakash, CR, Lagström, S, Hauschulz, K, Ewing, E, Shchetynsky, K, et al. Simultaneous detection of DNA variation and methylation at HLA class II locus and immune gene promoters using targeted SureSelect methyl-sequencing. Front Immunol. (2023) 14:1251772. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1251772

11. Zhou, F, Shen, C, Xu, J, Gao, J, Zheng, X, Ko, R, et al. Epigenome-wide association data implicates DNA methylation-mediated genetic risk in psoriasis. Clin Epigenetics. (2016) 8:131. doi: 10.1186/s13148-016-0297-z

12. Liu, Y, Aryee, MJ, Padyukov, L, Fallin, MD, Hesselberg, E, Runarsson, A, et al. Epigenome-wide association data implicate DNA methylation as an intermediary of genetic risk in rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Biotechnol. (2013) 31:142–7. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2487

13. Chi, C, Taylor, KE, Quach, H, Quach, D, Criswell, LA, and Barcellos, LF. Hypomethylation mediates genetic association with the major histocompatibility complex genes in Sjögren’s syndrome. PLoS One. (2021) 16:e0248429. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0248429

14. Li, E, and Zhang, Y. DNA methylation in mammals. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. (2014) 6:a019133. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a019133

15. Cree, BAC, Gourraud, PA, Oksenberg, JR, Bevan, C, Crabtree-Hartman, E, Gelfand, JM, et al. Long-term evolution of multiple sclerosis disability in the treatment era. Ann Neurol. (2016) 80:499–510. doi: 10.1002/ana.24747

16. Norman, PJ, Norberg, SJ, Guethlein, LA, Nemat-Gorgani, N, Royce, T, Wroblewski, EE, et al. Sequences of 95 human MHC haplotypes reveal extreme coding variation in genes other than highly polymorphic HLA class i and II. Genome Res. (2017) 27:813–23. doi: 10.1101/gr.213538.116

17. Osoegawa, K, Creary, LE, Montero-Martín, G, Mallempati, KC, Gangavarapu, S, Caillier, SJ, et al. High resolution haplotype analyses of classical HLA genes in families with multiple sclerosis highlights the role of HLA-DP alleles in disease susceptibility. Front Immunol. (2021) 12:644838. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.644838

18. Jühling, F, Kretzmer, H, Bernhart, SH, Otto, C, Stadler, PF, and Hoffmann, S. Metilene: fast and sensitive calling of differentially methylated regions from bisulfite sequencing data. Genome Res. (2016) 26:256–62. doi: 10.1101/gr.196394.115

19. McLean, CY, Bristor, D, Hiller, M, Clarke, SL, Schaar, BT, Lowe, CB, et al. GREAT improves functional interpretation of cis-regulatory regions. Nat Biotechnol. (2010) 28:495–501. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1630

20. Abascal, F, Acosta, R, Addleman, NJ, Adrian, J, Afzal, V, Aken, B, et al. Expanded encyclopaedias of DNA elements in the human and mouse genomes. Nature. (2020) 583:699–710. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2493-4

21. Shabalin, AA. Matrix eQTL: ultra fast eQTL analysis via large matrix operations. Bioinformatics. (2012) 28:1353–8. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts163

22. Millstein, J, Chen, GK, and Breton, CV. Cit: hypothesis testing software for mediation analysis in genomic applications. Bioinformatics. (2016) 32:2364–5. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btw135

23. Cavalli, G, Hayashi, M, Jin, Y, Yorgov, D, Santorico, SA, Holcomb, C, et al. MHC class II super-enhancer increases surface expression of HLA-DR and HLA-DQ and affects cytokine production in autoimmune vitiligo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. (2016) 113:1363–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1523482113

24. Enz, LS, Zeis, T, Schmid, D, Geier, F, van der Meer, F, Steiner, G, et al. Increased HLA-DR expression and cortical demyelination in MS links with HLA-DR15. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. (2020) 7:e656. doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000000656

25. Shamsul Islam, SM, Kim, HA, Choi, B, Jung, JY, Lee, SM, Suh, CH, et al. Differences in expression of human leukocyte antigen class ii subtypes and T cell subsets in behçet’s disease with arthritis. Int J Mol Sci. (2019) 20:5044. doi: 10.3390/ijms20205044

26. Yooyongsatit, S, Ruchusatsawat, K, Noppakun, N, Hirankarn, N, Mutirangura, A, and Wongpiyabovorn, J. Patterns and functional roles of LINE-1 and Alu methylation in the keratinocyte from patients with psoriasis vulgaris. J Hum Genet. (2015) 60:349–55. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2015.33

27. Reszka, E, Jabłońska, E, Lesicka, M, Wieczorek, E, Kapelski, P, Szczepankiewicz, A, et al. An altered global DNA methylation status in women with depression. J Psychiatr Res. (2021) 137:283–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.03.003

28. Li, S, Yang, Q, Hou, Y, Jiang, T, Zong, L, Wang, Z, et al. Hypomethylation of LINE-1 elements in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. J Psychiatr Res. (2018) 107:68–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2018.10.009

29. Casarotto, M, Lupato, V, Giurato, G, Guerrieri, R, Sulfaro, S, Salvati, A, et al. LINE-1 hypomethylation is associated with poor outcomes in locoregionally advanced oropharyngeal cancer. Clin Epigenetics. (2022) 14:171. doi: 10.1186/s13148-022-01386-5

30. Ikeno, M, Suzuki, N, Kamiya, M, Takahashi, Y, Kudoh, J, and Okazaki, T. LINE1 family member is negative regulator of HLA-G expression. Nucleic Acids Res. (2012) 40:10742–52. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks874

31. Saeliw, T, Permpoon, T, Iadsee, N, Tencomnao, T, Hu, VW, Sarachana, T, et al. LINE-1 and Alu methylation signatures in autism spectrum disorder and their associations with the expression of autism-related genes. Sci Rep. (2022) 12:13970. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-18232-6

32. Hunt, KV, Burnard, SM, Roper, EA, Bond, DR, Dun, MD, Verrills, NM, et al. Single-cell analysis of transposable element methylation to link global epigenetic heterogeneity with transcriptional programs. Sci Rep. (2022) 12:5776. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-09765-x

33. Maltby, VE, Lea, RA, Sanders, KA, White, N, Benton, MC, Scott, RJ, et al. Differential methylation at MHC in CD4+ T cells is associated with multiple sclerosis independently of HLA-DRB1. Clin Epigenetics. (2017) 9:71. doi: 10.1186/s13148-017-0371-1

34. Rauluseviciute, I, Drabløs, F, and Rye, MB. DNA hypermethylation associated with upregulated gene expression in prostate cancer demonstrates the diversity of epigenetic regulation. BMC Med Genet. (2020) 13:6. doi: 10.1186/s12920-020-0657-6

35. Smith, J, Sen, S, Weeks, RJ, Eccles, MR, and Chatterjee, A. Promoter DNA Hypermethylation and paradoxical gene activation. Trends. Cancer. (2020) 6:392–406. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2020.02.007

36. Ramsuran, V, Kulkarni, S, Ohuigin, C, Yuki, Y, Augusto, DG, Gao, X, et al. Epigenetic regulation of differential HLA-A allelic expression levels. Hum Mol Genet. (2015) 24:4268–75. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddv158

37. Silva, AM, Bettencourt, A, Pereira, C, Santos, E, Carvalho, C, Mendonça, D, et al. Protective role of the HLA-A*02 allele in Portuguese patients with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. (2009) 15:771–4. doi: 10.1177/1352458509104588

38. Agostini, S, Mancuso, R, Guerini, FR, D’Alfonso, S, Agliardi, C, Hernis, A, et al. HLA alleles modulate EBV viral load in multiple sclerosis. J Transl Med. (2018) 16:80. doi: 10.1186/s12967-018-1450-6

39. Bjornevik, K, Cortese, M, Healy, BC, Kuhle, J, Mina, MJ, Leng, Y, et al. Longitudinal analysis reveals high prevalence of Epstein-Barr virus associated with multiple sclerosis. Science. (2022) 375:296–301. doi: 10.1126/science.abj8222

40. Goodson-Gregg, FJ, Krepel, SA, and Anderson, SK. Tuning of human NK cells by endogenous HLA-C expression. Immunogenetics. (2020) 72:205–15. doi: 10.1007/s00251-020-01161-x

41. Ljunggren, HG, and Kärre, K. In search of the “missing self”: MHC molecules and NK cell recognition. Trends Immunol. (1990) 11:237–44. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(90)90097-s

42. Kulkarni, S, Martin, MP, and Carrington, M. The yin and Yang of HLA and KIR in human disease. Semin Immunol. (2008) 20:343–52. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2008.06.003

43. Anagnostouli, M, Artemiadis, A, Gontika, M, Skarlis, C, Markoglou, N, Katsavos, S, et al. HLA-DPB1*03 as risk allele and hla-dpb1*04 as protective allele for both early-and adult-onset multiple sclerosis in a hellenic cohort. Brain Sci. (2020) 10:374. doi: 10.3390/brainsci10060374

44. Marrosu, MG, Muntoni, F, Murru, MR, Spinicci, G, Pischedda, MP, Goddi, F, et al. Sardinian multiple sclerosis is associated with hla-dr4: a serologic and molecular analysis. Neurology. (1988) 38:1749–53. doi: 10.1212/WNL.38.11.1749

45. Modin, H, Olsson, W, Hillert, J, and Masterman, T. Modes of action of HLA-DR susceptibility specificities in multiple sclerosis [1]. Am J Hum Genet. (2004) 74:1321–2. doi: 10.1086/420977

46. Benedek, G, Paperna, T, Avidan, N, Lejbkowicz, I, Oksenberg, JR, Wang, J, et al. Opposing effects of the HLA-DRB10301-DQB10201 haplotype on the risk for multiple sclerosis in diverse Arab populations in Israel. Genes Immun. (2010) 11:423–31. doi: 10.1038/gene.2010.20

47. Isobe, N, Gourraud, PA, Harbo, HF, Caillier, SJ, Santaniello, A, Khankhanian, P, et al. Genetic risk variants in African Americans with multiple sclerosis. Neurology. (2013) 81:219–27. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31829bfe2f

48. An, J, Nakajima, T, Shibata, H, Arimura, T, Yasunami, M, and Kimura, A. A novel link of HLA locus to the regulation of immunity and infection: NFKBIL1 regulates alternative splicing of human immune-related genes and influenza virus M gene. J Autoimmun. (2013) 47:25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2013.07.010

Keywords: DNA methylation, major histocompatibility complex, multiple sclerosis, differentially methylated regions, DNA methylation quantitative trait loci

Citation: Ma Q, Augusto DG, Montero-Martin G, Caillier SJ, Osoegawa K, Cree BAC, Hauser SL, Didonna A, Hollenbach JA, Norman PJ, Fernandez-Vina M and Oksenberg JR (2023) High-resolution DNA methylation screening of the major histocompatibility complex in multiple sclerosis. Front. Neurol. 14:1326738. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2023.1326738

Received: 23 October 2023; Accepted: 23 November 2023;

Published: 08 December 2023.

Edited by:

Michael Carrithers, University of Illinois, United StatesReviewed by:

Rachele Bigi, Sapienza University of Rome, ItalyCopyright © 2023 Ma, Augusto, Montero-Martin, Caillier, Osoegawa, Cree, Hauser, Didonna, Hollenbach, Norman, Fernandez-Vina and Oksenberg. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jorge R. Oksenberg, am9yZ2Uub2tzZW5iZXJnQHVjc2YuZWR1

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.