95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Neurol. , 22 November 2023

Sec. Neuroepidemiology

Volume 14 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2023.1286129

This article is part of the Research Topic Epidemiology, Evidence-Based Care, and Outcomes in Spinal Cord Injury View all 15 articles

Kenedy Olsen1,2,3

Kenedy Olsen1,2,3 Kathleen A. Martin Ginis1,2,3,4

Kathleen A. Martin Ginis1,2,3,4 Sarah Lawrason1,2,3

Sarah Lawrason1,2,3 Christopher B. McBride5

Christopher B. McBride5 Kristen Walden6

Kristen Walden6 Catherine Le Cornu Levett7

Catherine Le Cornu Levett7 Regina Colistro7

Regina Colistro7 Tova Plashkes7

Tova Plashkes7 Andrea Bass7

Andrea Bass7 Teri Thorson5

Teri Thorson5 Ryan Clarkson5

Ryan Clarkson5 Rod Bitz5

Rod Bitz5 Jasmin K. Ma2,8,9*

Jasmin K. Ma2,8,9*Introduction: Physical Activity (PA) levels for individuals with spinal cord injury (SCI) peak during rehabilitation and sharply decline post-discharge. The ProACTIVE SCI intervention has previously demonstrated very large-sized effects on PA; however, it has not been adapted for use at this critically understudied timepoint. The objective is to evaluate the reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation, and maintenance of the ProACTIVE SCI intervention delivered by physiotherapists and SCI peer coaches during the transition from rehabilitation to community.

Methods: A single-group, within-subjects, repeated measures design was employed. The implementation intervention consisted of PA counseling training, champion support, prompts and cues, and follow-up training/community of practice sessions. Physiotherapists conducted counseling sessions in hospital, then referred patients to SCI peer coaches to continue counseling for 1-year post-discharge in the community. The RE-AIM Framework was used to guide intervention evaluation.

Results: Reach: 82.3% of patients at the rehabilitation hospital were reached by the intervention. Effectiveness: Interventionists (physiotherapists and SCI peer coaches) perceived that PA counseling was beneficial for patients. Adoption: 100% of eligible interventionists attended at least one training session. Implementation: Interventionists demonstrated high fidelity to the intervention. Intervention strategy highlights included a feasible physiotherapist to SCI peer coach referral process, flexibility in timepoint for intervening, and time efficiency. Maintenance: Ongoing training, PA counseling tracking forms, and the ability to refer to SCI peer coaches at discharge are core components needed to sustain this intervention.

Discussion: The ProACTIVE SCI intervention was successfully adapted for use by physiotherapists and SCI peer coaches during the transition from rehabilitation to community. Findings are important for informing intervention sustainability and scale-up.

Physical activity (PA) levels for individuals who have recently incurred a spinal cord injury (SCI) peak during inpatient rehabilitation and sharply decline after discharge (1). This is unsurprising given the substantial readjustment period experienced by individuals with SCI during the transition from hospital to the community. However, patients are often motivated from seeing their progress during the rehabilitation process, leading to greater interest and commitment to being active post-discharge (2). As such, it has been suggested to promote PA immediately following discharge (2). PA interventions that address the unique needs of people with SCI during the transition between hospital to community are crucial yet understudied.

A limited number of studies have examined the effects of PA interventions at the point of discharge among people with SCI. For example, in the ReSpAct trial, PA counseling was implemented by physiotherapists or sport therapists in 18 rehabilitation centers located throughout the Netherlands (3). Prior to being discharged, patients had an initial PA consultation and subsequently received counseling for 13-weeks post-discharge from trained PA counselors. Patients with diverse disabilities (~2% with SCI) who participated in the program exhibited an increase in their PA and sport participation levels following discharge from rehabilitation. Similarly, an intervention in the Netherlands initiated PA counseling during rehabilitation that was continued by physiotherapists or occupational therapists for 3-months after discharge and demonstrated small to medium-sized effects on PA behavior among those living with subacute SCI (4). These findings are promising; however, clinician time is often limited making the feasibility and scalability of therapist-delivered interventions challenging. There is value in examining other interventionist groups to continue PA counseling post-discharge.

The ProACTIVE SCI intervention is a PA counseling intervention that was co-developed by ~300 end-users including healthcare providers and people with SCI. This intervention has previously demonstrated very large effect sizes for increasing PA behavior that were sustained over 6 months in the research setting (5). The intervention was co-developed with both physiotherapists (community, in-patient, and out-patient) and people with SCI who shared their lived experiences of PA across the rehabilitation continuum. Given the need for PA interventions during the transition from rehabilitation to community, we wanted to explore the adoption of the ProACTIVE SCI when delivered by clinicians and peers across this transition.

SCI peers and health service providers have been identified as preferred messengers of PA information (6). SCI peers can communicate the lived experience of a SCI and help those with a new SCI improve or maintain their PA behavior in the community-setting (7). Further, research has shown peer-delivered PA interventions to be as effective as professionally delivered interventions for increasing PA (8). Physiotherapists have the knowledge and confidence to prescribe exercise and encourage their patients to lead physically active lives (9). To date, no studies have explored the implementation of a coordinated, clinician-to-peer PA counseling service at the point of discharge.

Evaluation frameworks can be used to support implementation through systematic development and evaluation of programs and interventions. A widely used evaluation tool is the RE-AIM framework, which assesses the impact of an intervention across five domains: reach (the percentage of individuals who receive or are affected by a program), effectiveness (the positive and negative consequences of a program), adoption (the proportion of settings of intervention agents that adopt a policy or program), implementation (the extent to which a program is delivered as intended or clients' use of the intervention and implementation strategies), and maintenance (the extent to which a behavior or program becomes routine or maintained over time) (10). This framework was developed to evaluate the impact of public health programs, and now is widely used in many contexts as both a planning and evaluation guide for community interventions at the individual and community level (11). The RE-AIM framework has also been previously used to evaluate PA behavior change interventions (12). Using the RE-AIM framework, the purpose of this study was to evaluate the reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation, and maintenance of an evidence-based PA intervention for people with SCI delivered by physiotherapists and SCI peer coaches during the transition from rehabilitation to community.

Interventionists (physiotherapists and SCI peer mentors/SCI peer coaches) were recruited via email from a rehabilitation hospital (GF Strong) and provincial SCI organization (Spinal Cord Injury BC) in Vancouver, BC, Canada. Relevant staff physiotherapists (i.e., those working in the spine or neuromusculoskeletal unit) and SCI peer staff members were contacted by each site's leadership [participant recruitment has been described previously in Ma et al. (5)].

This study used a hybrid implementation-effectiveness study design which is the simultaneous testing of an implementation strategy and a clinical intervention (13). A single-group within-subjects, repeated measures design was used. Details of the study design have been previously reported (14). The implementation evaluation is discussed here. The effectiveness (clinical) study evaluates the impact of the ProACTIVE SCI Intervention on patient PA levels and is reported elsewhere (Olsen et al., in preparation). Ethics approval for the protocol was granted by the Behavioral Research Ethics Board at the University of British Columbia (H19-02694).

Physiotherapists and SCI peer coaches received an initial, in-person 2-h training (March 2020) on how to deliver the ProACTIVE SCI intervention and were provided with PA counseling forms tailored for each setting. A follow-up two-hour training session for dedicated practice and feedback was conducted 1 month later. It was intended to be conducted in-person, but was conducted via Zoom due to the restrictions of the COVID-19 pandemic. Physiotherapists and SCI peer coaches who attended the initial training session were supported by activities delivered by the champions (dedicated individuals who facilitate implementation) including monitoring, feedback, prompts to continue PA counseling, and problem solving. A prompt was added to physiotherapists' patient-oriented discharge summaries to cue the PA conversation as part of their typical workflow. A third training session (November 2020) was added to re-launch the study after research activities were halted due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Four follow-up training/community of practice sessions were completed over the course of 2 years. See Ma et al. (14) for further details.

Following the initial training, physiotherapists conducted PA counseling sessions with patients during rehabilitation. Briefly, counseling sessions, grounded in motivational interviewing and the Health Action Process Approach model, involved a discussion to understand client's readiness for PA, goals, barriers, activity preferences, and access to PA resources to then co-develop a PA plan (15, 16). During initial sessions physiotherapists completed a PA counseling form, which was forwarded to SCI peer coaches who would continue counseling sessions with patients for 1-year post-discharge in the community. However, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, counseling in the community did not occur for a 10-month period (March 2020–November 2020). Physiotherapists continued to send PA counseling referrals during this time, but all counseling was delayed in accordance with Public Health recommendations. In November of 2020 the study was re-launched to include the SCI peer coach PA counseling, and the first community counseling session delivered by a SCI peer coach took place in January 2021.

The RE-AIM framework was used to guide the evaluation of the reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation, and maintenance of the intervention. Descriptions of the RE-AIM elements and how these data were operationalized are described in Table 1.

Client discharge summaries (CDS) were reviewed by physiotherapist champions to monitor which patients received PA counseling and determine intervention reach. Physiotherapists documented the date the form was completed, if a PA counseling conversation was offered (Yes/No), and reasons as to why PA conversations did not occur (if applicable). The total number of patients who received a full or partial PA conversation (numerator), was divided by the total number of patients with SCI admitted to the rehabilitation hospital during the study duration (denominator) to determine a reach percentage.

Individual semi-structured interviews were conducted over the phone or via Zoom 6-months post training with physiotherapists and SCI peer coaches. Implementation interventions require researchers to strategically combine and borrow from established qualitative approaches to meet the specific needs of the study, which is inherently pragmatic in nature (17). Therefore, a pragmatic qualitative approach was used, in which emphasis is placed on the intersubjectivity of findings (i.e., the idea that there is neither complete objectivity nor subjectivity when interpreting results) (18). Further, a pragmatic approach allowed us to prioritize the translation, co-production of knowledge, and applicability of findings to real world settings (18). Interviews explored factors that affected the effectiveness (i.e., patient benefits), implementation (i.e., intervention timing, feasibility, and impact on interventionist time) and maintenance of the intervention (e.g., program sustainability and scale-up to other rehabilitation centers). Analysis of implementation barriers and facilitators reported in these interviews is reported elsewhere (Lin et al., in preparation). Interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim using Zoom audio transcription software. Zoom-produced transcripts were manually checked by the first author (KO) for accuracy. Interviews were coded using an iterative inductive content analysis approach to map onto the elements within the RE-AIM framework (19). NVivo was used to code transcripts (KO). Codes were then compared by a co-author (JM) to provide feedback and engage in discussion to refine the codes. Member checking was used to confirm and refine the interpretation of the findings.

The number of staff who were eligible to participate in the ProACTIVE SCI training was collected using recall from the physiotherapist clinical practice lead (CC-L) at the rehabilitation hospital and the executive director of the provincial SCI peer organization (CM) to determine intervention adoption. The number of interventionists attending the training was collected using attendance sheets. Adoption was calculated by taking the number of interventionists who attended the training sessions (numerator), compared to the total number of individuals who were eligible to attend the training sessions (denominator).

Physiotherapists completed a standardized PA counseling/referral form to document the use of the ProACTIVE SCI intervention components (i.e., discuss current PA levels, goal setting, PA preferences, resources, barriers, and conduct problem-solving and action planning) with patients prior to discharge. SCI peer coaches completed a similar counseling form when conducting PA counseling in the community.

Intervention fidelity (within the implementation domain) was assessed by reviewing the use of the initial intake session forms for both physiotherapists and SCI peer coaches. Each section of the form was marked as “yes” if used, and “no” if left blank. Intervention fidelity was calculated by dividing the summed number of form components completed across the forms (as indicated by “yes”) completed by physiotherapists and SCI peer coaches separately, divided by the total number of times these components could have been used. The higher the completion score (0–100%), the greater the fidelity of delivery. Follow-up SCI peer coach PA counseling forms were evaluated as described above but were also summarized for each follow-up session timepoint.

Given the pragmatic nature of the study, we aimed to recruit all eligible physiotherapists (n = 13) and SCI peer coaches (n = 2). Of note, the SCI peer coaches participating in the study had their regular duties shifted to participate in this role. This limited the recruitment of SCI peer coaches to what was feasible for the organization.

Reach percentages were calculated at the patient level (Table 2). One-hundred and forty-one patients were admitted to the rehabilitation hospital with a SCI during the time of recruitment for the study. Of these, 24 patients did not have a PA conversation due to extenuating circumstances, 42 had a partial PA conversation, and 74 of these patients had a full PA conversation with their physiotherapist. Of these 74 conversations, 28 patients consented to participate in the study and receive further PA counseling.

Analysis of semi-structured interviews resulted in identifying categories within the RE-AIM domains of effectiveness, implementation, and maintenance (Table 3). For effectiveness, both physiotherapists and SCI peer coaches perceived that their patients understood the benefits of PA and receiving PA counseling, as they observed that the information being delivered was effectively used and comprehended by the patients. Four categories were identified related to implementation: (1) physiotherapists found the referral process to the SCI peer organization to be feasible; (2) interventionists identified that there was no single best timepoint for intervening and was instead dependent upon the individual, (3) implementing PA conversations was time efficient for physiotherapists and did not impact their time beyond usual practice; and (4) conducting PA counseling did not change the process of discharge planning for patients, but led to an increase in the use of the SCI PA guidelines by physiotherapists. Three categories were identified within maintenance: (1) resource accessibility and interventionist buy-in are potential barriers to expanding the ProACTIVE SCI intervention to other rehabilitation centers; (2) interventionists anticipated the potential for PA counseling forms to be used among diverse populations beyond SCI; (3) physical activity counseling forms, refresher meetings and ongoing practice sessions are essential implementation intervention components needed to sustain PA counseling delivery.

All practicing physiotherapists in the relevant units at the rehabilitation hospital who were eligible for the training attended the initial ProACTIVE SCI training session in March, 2020. Eighty-five percent of the attendees of the first training session attended the second session. Further, 77% of these physiotherapists attended the refresher training in November 2020. All of the designated SCI BC peer coaches received the ProACTIVE training and attended all training sessions.

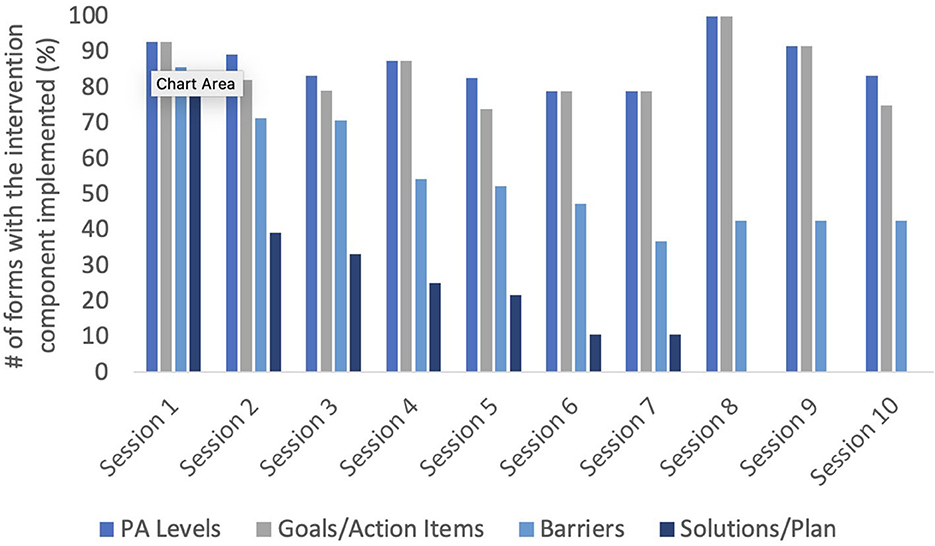

Physiotherapists PA referral/counseling forms showed that the most frequently used components of the forms included: whether the patient was interested in discussing PA, goal setting, activity preferences, resources available, potential barriers, and action planning (Table 4). The least used components of these forms were discussing the benefits of PA, current PA levels, and the SCI PA guidelines (Table 4). PA counseling forms, completed by SCI peer coaches, showed that all sections of the forms were used by peer coaches during initial counseling sessions, but the use of these components decreased over time (Figure 1). Specifically, peer coaches consistently discussed patients' PA and goal setting/action planning across all sessions. Discussing barriers to being active was consistently used during sessions 1–5, and slowly decreased in use for the remaining sessions (i.e., sessions 6–10). Lastly, developing a plan/solution for being active dropped substantially in use between the first and second session, and was only occasionally used (i.e., <30% of the time) beyond the third session. Further, this section was not used at all beyond the seventh follow-up session for any patient.

Figure 1. Frequency of PA counseling behaviors delivered by SCI peer coaches during follow-up counseling sessions over time. Not all patients elected to receive all 10 offered sessions (4 patients attended 2 sessions; 1 patient attended 4 sessions; 4 patients attended 5 sessions; 3 patients attended 7 sessions; and 12 patients attended all sessions). Further, 4 patients withdrew from the study after their second counseling session. Therefore, values are reported as percentages relative to the number of patients who attended the session.

This study aimed to evaluate the reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation, and maintenance of an evidence-based PA intervention for people with SCI that was delivered by physiotherapists and SCI peer coaches during the transition from rehabilitation to community. Results showed that the ProACTIVE SCI intervention reached the majority of patients who were admitted to the rehabilitation hospital, suggesting successful adaptation for use during this transitional period. Implementation was supported by high fidelity to the PA counseling intervention components and interview findings suggest the feasibility of the intervention with respect to minimal impacts on time beyond usual practice or discharge planning. Further, the coordination of program delivery between physiotherapists and SCI peer coaches was deemed feasible. This coordinated referral approach along with core intervention components such as ongoing training with opportunities for practice and a PA counseling form is suggested to be integral to the long-term maintenance of the ProACTIVE SCI intervention. While these finding are context-specific, we suggest strategies for future sites to adopt the ProACTIVE SCI at this critically understudied timepoint. More broadly, findings can support the integration of a clinician to peer mentor/coach referral system that links clients from rehabilitation to community in rehabilitation institutes across Canada.

This intervention reached 82% of patients admitted to the participating rehabilitation hospital. This is in line with previous research examining the delivery of PA counseling interventions to the general population who were using primary care clinics, which found that 77% of patients were reached by the program (12). The high level of reach in the current study could be due to the ease with which patients could receive this program. PA counseling was integrated into the standard of care patients would receive from their physiotherapist by adding a prompt to their existing patient-oriented discharge summaries. Semi-structured interviews with physiotherapists highlighted that integrating PA counseling conversations was time efficient and naturally fit into the scope of their practice, further supporting the high level of patient reach. However, the initial reach of the program did not directly translate to participating in continued PA counseling in the community program. Specifically, less than half of the patients who received a PA counseling session from their physiotherapist consented to participate in the full intervention (i.e., continue the PA counseling in the community). As mentioned, the time following discharge can be an overwhelming readjustment leading to decreases in PA (1). PA often does not take priority after rehabilitation with competing concerns like housing, accessibility, family, and financial considerations (20). Further, individuals with SCI often face barriers like lack of time, energy, and motivation to be physically active post-injury, making it especially challenging to participate in PA (21). While the intervention reach to patients was high in-hospital, it is possible that not all patients are ready to prioritize PA during the transition to community and further examination is warranted to better support this transition (6).

Interviews revealed that both physiotherapists and SCI peer coaches held positive attitudes toward the intervention and highlighted positive perceived benefits for patients participating in PA counseling, including increased planning for PA and increased awareness for managing PA barriers. Theories of behavior change have previously supported the link between attitudes and intention formation, and later behavioral enactment (e.g., Theory of Planned Behavior and the Health Action Process Approach) (22, 23). Interventionists held positive attitudes toward the intervention, which may have contributed to the improved counseling behaviors over time (Shu et al., under review). The importance of attitudes in predicting counseling behaviors has been previously supported. Results of a study that investigated the voluntary delivery of HIV counseling among schoolteachers using the theory of planned behavior showed that intention to deliver this counseling was significantly predicted by attitudes toward the intervention (24).

The ProACTIVE SCI intervention was successfully adopted by all physiotherapists at the rehabilitation hospital and all eligible SCI peer coaches. We used an integrated knowledge translation (IKT) approach whereby physiotherapists and people with SCI were involved in the development, delivery and analysis of the research. This allowed for evidence from both research and practice contexts to bi-directionally inform intervention decision-making, and is consistent with the IKT Guiding Principles for conducting SCI research in partnership (25). Interventions that are designed and implemented together with stakeholders are often more likely to be adopted within existing delivery systems (26). For example, an effectiveness-implementation trial compared the adoption of physical activity programs that were iteratively and interactively developed with stakeholders to programs that were unidirectionally disseminated (26). Comparison of the two program design types demonstrated that the two designs showed similar effects on PA behavior, however, programs that involved end-users in development reported significantly greater adoption rates, intentions to sustain program delivery, and participant reach. Organizations wanting to increase adoption rates and potentially support implementation sustainability should seek to meaningfully engage delivering partners as best practice when designing and implementing programs.

When designing clinical interventions, interventionists need to be able to implement these programs into their standard-of-care practice. In the current study, PA counseling was incorporated into typical patient discharge planning, which resultantly had minimal impact on time beyond usual workload. Incorporating non-treatment PA advice during normal consultations has previously shown to be perceived as more feasible than creating a separate PA counseling session (9).

Beyond incorporating the PA counseling conversation into their regular discharge planning, use of PA counseling forms and referral to SCI peer coaches to continue PA counseling post-discharge were critical aspects of the successful intervention implementation. As highlighted in the interviews, physiotherapists found the structure provided by the counseling forms to be helpful in providing a framework when delivering PA counseling (supported by the high fidelity to the core components outlined in the forms), but also offered flexibility to tailor their delivery to the individual. Transferability of interventions to new contexts is often uncertain, and interventions need to be adapted to be successful and effective (27). A systematic review of the adaptation of programs implemented in community settings found the most common intervention adaptations were adding or removing elements to tailor the program to each individual (28). Similarly, SCI peer coaches delivered PA counseling in the community with high fidelity. However, follow-up counseling sessions often employed fewer components of these forms over time as needed. For example, discussing barriers to PA and providing solutions to these barriers was used less frequently in the later counseling sessions. This is unsurprising, as over time, patients likely needed less problem solving as barriers typically are addressed in the earlier counseling sessions. These findings are in line with a previous examination of the behavior change techniques employed using the ProACTIVE intervention in the research setting, where the time spent delivering behavior change techniques related to goals and planning decreased in the follow-up sessions as compared to the initial session (29).

Interventionists perceived the intervention could be used in other sites as well as among other populations with disability. However, they noted the primary barriers to scaling this intervention to other centers included access to facilities designed to promote accessible PA and interventionist buy-in. Options for PA may be unusable by some clients with SCI due to lack of transportation, building/facility access, inclusiveness amongst programs, or knowledge of staff, as examples (30, 31). With respect to interventionist buy-in, interventionists voiced that maintaining PA counseling as a priority is challenging, though ongoing trainings may help address this challenge. Professionals who are committed to ongoing learning and training have previously been shown to be more effective teachers, and those resistant to receiving training show low levels of program implementation (32). Lastly, while not examined in this study, interventionists foresaw the opportunity for the ProACTIVE SCI intervention to be adapted for use among other populations. Use of physical activity counseling in clinical settings is well-studied among other populations (33–35). However, examination of coordinated referral to peer services from rehabilitation is limited and warrants further study in other clinical populations.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine coordinated PA counseling between physiotherapists and SCI peer coaches at the point of hospital discharge. In Canada, each province has an equivalent SCI advocacy organization. These findings may support the case for modeling this coordinated referral process across the country. Another strength of this work is the integrated knowledge translation approach. Representatives from all involved parties were involved in decision-making from the point of research question inception through to implementation. The importance of this collaborative approach is highlighted by the sustained use of this intervention beyond the project lifecycle as both the rehabilitation hospital and provincial SCI organization have adopted this intervention into standard practice.

As limitations, due to restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic, any new staff hired onto the spine unit at the rehabilitation hospital were not trained to deliver the ProACTIVE SCI intervention. This may have led to fewer patients having PA counseling conversations and subsequently being referred to SCI peer counseling. Despite a break in the study, the majority of patients did receive PA counseling as reflected in the high reach levels observed in this study. Another limitation was in interpreting the fidelity to the intervention by examining use of the PA forms. Analysis of these forms revealed infrequent discussion of the benefits of PA or the SCI PA guidelines. As these sections were summarized in a diagram, there was no text required to record whether these sections were discussed within the referral form. Other form components (e.g., goal setting) require a text entry from the provider. Therefore these sections may have been delivered to patients, but were undocumented. Lastly, reach data was collected by champions who would periodically review client discharge summaries with the group of physiotherapists to report whether they delivered the ProACTIVE SCI intervention with each patient. It is possible that social pressures may have influenced the reporting or even acted as an intervention component (e.g., social influences) itself. Lastly, the intervention was delivered by only two SCI peer coaches. Since completing the study, additional SCI peer coaches have been trained and it would be valuable to examine the implementation and effectiveness of this interventions amongst a greater diversity of SCI peer coaches.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that the ProACTIVE SCI Toolkit can be adapted for use by physiotherapists and SCI peer coaches during the transition from rehabilitation to community, a critical and understudied timepoint for PA intervention. Findings are important for informing intervention sustainability and scale-up to other institutions and interventions. Future studies should continue to monitor program maintenance of the ProACTIVE SCI intervention beyond the 6-month period.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving humans were approved by Behavioral Research Ethics Board at the University of British Columbia (H19-02694). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

KO: Writing—original draft, Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing—review & editing. KM: Conceptualization, Writing—review & editing, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Supervision. SL: Writing—review & editing, Formal analysis, Methodology. CM: Writing—review & editing, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition. KW: Writing—review & editing, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration. CL: Writing—review & editing, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Resources. RCo: Writing—review & editing, Conceptualization. TP: Writing—review & editing, Conceptualization. AB: Writing—review & editing, Conceptualization. TT: Writing—review & editing, Conceptualization, Project administration. RCl: Writing—review & editing, Conceptualization, Project administration. RB: Writing—review & editing, Conceptualization, Project administration. JM: Writing—review & editing, Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was supported in part by a grant from Praxis Spinal Institute (G2021-21).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. van den Berg-Emons RJ, Bussmann JB, Haisma JA, Sluis TA, van der Woude LH, Bergen MP, et al. A prospective study on physical activity levels after spinal cord injury during inpatient rehabilitation and the year after discharge. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. (2008) 89:2094–101. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2008.04.024

2. Rimmer JH. Getting beyond the plateau: bridging the gap between rehabilitation and community-based exercise. PM and R. (2012) 4:857–61. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2012.08.008

3. Hoekstra F, Hoekstra T, van der Schans CP, Hettinga FJ, van der Woude LHV, Dekker R. The implementation of a physical activity counseling program in rehabilitation care: findings from the ReSpAct study. Disabil Rehabil. (2021) 43:1710–21. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2019.1675188

4. Nooijen CFJ, Stam HJ, Bergen MP, Bongers-Janssen HMH, Valent L, van Langeveld S, et al. A behavioural intervention increases physical activity in people with subacute spinal cord injury: a randomised trial. J Physiother. (2016) 62:35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jphys.2015.11.003

5. Ma JK, West CR, Martin Ginis KA. The effects of a patient and provider co-developed, behavioral physical activity intervention on physical activity, psychosocial predictors, and fitness in individuals with spinal cord injury: a randomized controlled trial. Sports Med. (2019) 49:1117–31. doi: 10.1007/s40279-019-01118-5

6. Letts L, Martin Ginis KA, Faulkner G, Colquhoun H, Levac D, Gorczynski P. Preferred methods and messengers for delivering physical activity information to people with spinal cord injury: a focus group study. Rehabil Psychol. (2011) 56:128–37. doi: 10.1037/a0023624

7. Veith EM, Sherman JE, Pellino TA, Yasui NY. Qualitative analysis of the peer-mentoring relationship among individuals with spinal cord injury. Rehabil Psychol. (2006) 51:289–98. doi: 10.1037/0090-5550.51.4.289

8. Ginis KAM, Nigg CR, Smith AL. Peer-delivered physical activity interventions: an overlooked opportunity for physical activity promotion. Transl Behav Med. (2013) 31:434–43. doi: 10.1007/s13142-013-0215-2

9. Shirley D, Van Der Ploeg HP, Bauman AE. Physical activity promotion in the physical therapy setting: perspectives from practitioners and students. Phys Ther. (2010) 90:1311–22. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20090383

10. Glasgow RE, Harden SM, Gaglio B, Rabin B, Smith ML, Porter GC, et al. RE-AIM planning and evaluation framework: adapting to new science and practice with a 20-year review. Front Public Health. (2019) 7:64. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00064

11. Gaglio B, Shoup JA, Glasgow RE. The RE-AIM framework: a systematic review of use over time. Public Health. (2013) 103:e38–e46. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301299

12. Galaviz KI, Estabrooks PA, Ulloa EJ, Lee RE, Janssen I, López y Taylor J, et al. Evaluating the effectiveness of physician counseling to promote physical activity in Mexico: an effectiveness-implementation hybrid study. Transl Behav Med. (2017) 7:731–40. doi: 10.1007/s13142-017-0524-y

13. Curran GM, Bauer M, Mittman B, Pyne JM, Stetler C. Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: Combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Med Care. (2012) 50:217–26. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182408812

14. Ma JK, Walden K, McBride CB, Le Cornu Levett C, Colistro R, Plashkes T, et al. Implementation of the spinal cord injury exercise guidelines in the hospital and community settings: protocol for a type II hybrid trial. Spinal Cord. (2021) 60:53–7. doi: 10.1038/s41393-021-00685-7

15. Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Guildford Press. (2013).

16. Schwarzer R, Lippke S, Luszczynska A. Mechanisms of health behavior change in persons with chronic illness or disability: the health action process approach (HAPA). Rehabil Psychol. (2011) 56:161–70. doi: 10.1037/a0024509

17. Ramanadhan S, Revette AC, Lee RM, Aveling EL. Pragmatic approaches to analyzing qualitative data for implementation science: an introduction. Implement Sci Commun. (2021) 2:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s43058-021-00174-1

18. Morgan DL. Paradigms lost and pragmatism regained: methodological implications of combining qualitative and quantitative methods. J Mix Methods Res. (2007) 1:48–76. doi: 10.1177/2345678906292462

19. Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. (2005) 15:1277–88. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687

20. Van der Ploeg HP, Streppel KR, Van der Beek AJ, Van der Woude LH, Vollenbroek-Hutten MM, Van Harten WH, et al. Successfully improving physical activity behavior after rehabilitation. Am J Health Promot. (2007) 21:153–9. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-21.3.153

21. Williams TL, Smith B, Papathomas A. The barriers, benefits and facilitators of leisure time physical activity among people with spinal cord injury: a meta-synthesis of qualitative findings. Health Psychol Rev. (2014) 8:404–25. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2014.898406

22. Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organiz Behav Hum Decis Proc. (1991) 50:179–211. doi: 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

23. Schwarzer R. Modeling health behavior change: how to predict and modify the adoption and maintenance of health behaviors. Appl Psychol. (2008) 57:1–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-0597.2007.00325.x

24. Kakoko DC, Åstrøm AN, Lugoe WL, Lie GT. Predicting intended use of voluntary HIV counselling and testing services among Tanzanian teachers using the theory of planned behaviour. Soc Sci Med. (2006) 63:991–9. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.02.016

25. Gainforth HL, Hoekstra F, McKay R, McBride CB, Sweet SN, Martin Ginis KA, et al. Integrated knowledge translation guiding principles for conducting and disseminating spinal cord injury research in partnership. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. (2021) 102:656–63. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2020.09.393

26. Harden SM, Johnson SB, Almeida FA, Estabrooks PA. Improving physical activity program adoption using integrated research-practice partnerships: an effectiveness-implementation trial. Transl Behav Med. (2017) 7:28–38. doi: 10.1007/s13142-015-0380-6

27. Evans RE, Craig P, Hoddinott P, Littlecott H, Moore L, Murphy S, et al. When and how do “effective” interventions need to be adapted and/or re-evaluated in new contexts? The need for guidance. J Epidemiol Commun Health. (2019) 73:481–2. doi: 10.1136/jech-2018-210840

28. Escoffery C, Lebow-Skelley E, Haardoerfer R, Boing E, Udelson H, Wood R, et al. A systematic review of adaptations of evidence-based public health interventions globally. Implement Sci. (2018) 13:125. doi: 10.1186/s13012-018-0815-9

29. Hoekstra F, Martin Ginis KA, Collins D, Dinwoodie M, Ma JK, Gaudet S, et al. Applying state space grids methods to characterize counsellor-client interactions in a physical activity behavioural intervention for adults with disabilities. Psychol Sport Exerc. (2023) 1:65. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2022.102350

30. Martin JJ. Benefits and barriers to physical activity for individuals with disabilities: a social-relational model of disability perspective. Disabil Rehabil. (2013) 43:2030–7. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2013.802377

31. Rimmer JH, Riley B, Wang E, Rauworth A, Jurkowski J. Physical activity participation among persons with disabilities: barriers and facilitators. Am J Prev Med. (2004) 26:419–25. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.02.002

32. Helmer J, Bartlett C, Wolgemuth JR, Lea T. Coaching (and) commitment: Linking ongoing professional development, quality teaching and student outcomes. Prof Dev. Educ. (2011) 37:197–211. doi: 10.1080/19415257.2010.533581

33. Goryakin Y, Suhlrie L, Cecchini M. Impact of primary care-initiated interventions promoting physical activity on body mass index: systematic review and meta-analysis. Obesity Rev. (2018) 19:518–28. doi: 10.1111/obr.12654

34. Orrow G, Kinmonth AL, Sanderson S, Sutton S. Effectiveness of physical activity promotion based in primary care: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. (2012) 344:16. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e1389

Keywords: physical activity counseling, spinal cord injury, rehabilitation, physiotherapist, SCI peers

Citation: Olsen K, Martin Ginis KA, Lawrason S, McBride CB, Walden K, Le Cornu Levett C, Colistro R, Plashkes T, Bass A, Thorson T, Clarkson R, Bitz R and Ma JK (2023) Assessing the reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation, and maintenance of the ProACTIVE SCI physical activity counseling intervention among physiotherapists and SCI peer coaches during the transition from rehabilitation to community. Front. Neurol. 14:1286129. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2023.1286129

Received: 30 August 2023; Accepted: 30 October 2023;

Published: 22 November 2023.

Edited by:

Lisa N. Sharwood, University of New South Wales, AustraliaReviewed by:

Birgitta Langhammer, Oslo Metropolitan University, NorwayCopyright © 2023 Olsen, Martin Ginis, Lawrason, McBride, Walden, Le Cornu Levett, Colistro, Plashkes, Bass, Thorson, Clarkson, Bitz and Ma. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jasmin K. Ma, SmFzbWluLk1hQHViYy5jYQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.