- 1Iranian Center of Neurological Research, Neuroscience Institute, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

- 2Neuroscience Research Center, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

- 3Department of Headache, Iranian Center of Neurological Research, Neuroscience Institute, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

- 4Neurology Ward, Sina Hospital, School of Medicine, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

- 5Basic and Molecular Epidemiology of Gastrointestinal Disorders Research Center, Research Institute for Gastroenterology and Liver Diseases, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

- 6School of Medicine, Shahrekord University of Medical Sciences, Shahrekord, Iran

- 7Minimally Invasive Surgery Research Centre, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Background: Headache is the most frequent neurological adverse event following SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. We investigated the frequency, characteristics, and factors associated with post-vaccination headaches, including their occurrence and prolongation (≥ 48 h).

Methods: In this observational cross-sectional cohort study, retrospective data collected between April 2021–March 2022 were analyzed. Univariate and multivariate logistic regressions were used to evaluate the effect of clinicodemographic factors on the odds of post-vaccination headache occurrence and prolongation.

Results: Of 2,500 people who were randomly sent the questionnaire, 1822 (mean age: 34.49 ± 11.09, female: 71.5%) were included. Headache prevalence following the first (V1), second (V2), and third (V3) dose was 36.5, 23.3, and 21.7%, respectively (p < 0.001). Post-vaccination headaches were mainly tension-type (46.5%), followed by migraine-like (36.1%). Headaches were mainly bilateral (69.7%), pressing (54.3%), moderate (51.0%), and analgesic-responsive (63.0%). They mainly initiated 10 h [4.0, 24.0] after vaccination and lasted 24 h [4.0, 48.0]. After adjusting for age and sex, primary headaches (V1: aOR: 1.32 [95%CI: 1.08, 1.62], V2: 1.64 [1.15, 2.35]), post-COVID-19 headaches (V2: 2.02 [1.26, 3.31], V3: 2.83 [1.17, 7.47]), headaches following the previous dose (V1 for V2: 30.52 [19.29, 50.15], V1 for V3: 3.78 [1.80, 7.96], V2 for V3: 12.41 [4.73, 35.88]), vector vaccines (V1: 3.88 [3.07, 4.92], V2: 2.44 [1.70, 3.52], V3: 4.34 [1.78, 12.29]), and post-vaccination fever (V1: 4.72 [3.79, 5.90], V2: 6.85 [4.68, 10.10], V3: 9.74 [4.56, 22.10]) increased the odds of post-vaccination headaches. Furthermore, while primary headaches (V1: 0.63 [0.44, 0.90]) and post-COVID-19 headaches (V1: 0.01 [0.00, 0.05]) reduced the odds of prolonged post-vaccination headaches, psychiatric disorders (V1: 2.58 [1.05, 6.45]), headaches lasting ≥48 h following the previous dose (V1 for V2: 3.10 [1.08, 10.31]), and migraine-like headaches at the same dose (V3: 5.39 [1.15, 32.47]) increased this odds.

Conclusion: Patients with primary headaches, post-COVID-19 headaches, or headaches following the previous dose, as well as vector-vaccine receivers and those with post-vaccination fever, were at increased risk of post-SARS-CoV-2-vaccination headaches. Primary headaches and post-COVID-19 headaches reduced the odds of prolonged post-vaccination headaches. However, longer-lasting headaches following the previous dose, migraine-like headaches at the same dose, and psychiatric disorders increased this odd.

1. Introduction

Headache disorders are among the most prevalent and debilitating conditions worldwide, accounting for 1.82 and 5.37% of total disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) and years lost to disability (YLDs), respectively (1–3). Globally, the prevalence of active headache disorders among adults is estimated to be over 50% (4, 5). Since the advent of coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19), caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), an array of associated neurological symptoms, including headaches, have been documented (6–10). Approved and authorized SARS-COV-2 vaccines are the most effective and safest tools for preventing COVID-19-related morbidity and mortality (11). As of January 2023, more than 13 billion SARS-CoV-2 vaccine doses have been administered (12). Nevertheless, concerns over the neurological adverse events (AEs) following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination were disclosed, of which headaches were the most frequent (13–15).

With an estimated incidence rate of 93.696 per 100,000 per year, headaches are the most frequent neurological manifestation following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination (16), affecting approximately 20–40% of individuals (17–20), and even higher in those with a previous history of headache disorders (21–23). According to a recent meta-analysis, SARS-CoV-2 vaccines were associated with a two-fold increased risk of headache within seven days of administration (19). Headaches are also reported as common AEs following other vaccines, including influenza, bivalent meningococcal group B vaccine, quadrivalent meningococcal diphtheria toxoid conjugate vaccine, and quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine (20, 24). Nevertheless, according to the international classification of headache disorders (ICHD-3), no classification or diagnostic features have been specifically defined for vaccine-related headaches so far (25).

Understanding the characteristics of post-vaccination headaches is of immense importance since while headaches are usually considered non-serious, they can also be a sign of life-threatening conditions, including cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT) (26), acute myelitis (27), and intracerebral hemorrhage (28). Although vaccine-related headaches are frequently reported, there are few studies thoroughly describing the characteristics of headaches following the SARS-COV-2 vaccination (19, 23, 29–32). Moreover, while factors associated with post-COVID-19 infection headaches have been widely investigated (33–35), to our knowledge, factors associated with post-SARS-CoV-2 vaccination headaches occurrence (20, 29, 35) and particularly prolongation are much less discussed in the literature, and there are still conflicting findings in this area.

In light of this information, we aimed to investigate the frequency and characteristics of headaches attributed to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination, determine factors associated with developing headaches following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination, and identify the factors related to prolonged headaches (≥ 48 h) among SARS-CoV-2 vaccine receivers. In particular, we sought to investigate which characteristics of the patient’s previous headaches (primary headaches, headaches after COVID-19, and headaches after the previous vaccine doses) could predict the occurrence and prolongation of headaches after receiving the following the 1st (V1), 2nd (V2), and 3rd (V3) dose of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study design

In this Institutional Review Board-approved web-based, population-based cross-sectional cohort study, retrospective data (April 2021–March 2022) were analyzed. Patients gave their informed consent for participation and publishing, according to the Declaration of Helsinki (36). The individuals who were solicited to participate in our study were randomly selected from a pool of patients within the healthcare system who had documented vaccine immunization. From this pool, 2,500 individuals who had received at least one vaccine dose (1st or 2nd or 3rd) in the last month were randomly chosen. The reason for choosing a one-month interval was to ensure that the time between answering the survey and receiving the vaccine was neither too short, as headaches could develop after answering the survey or persist beyond the response date, nor too long, as it could increase recall bias. Additionally, in case of long intervals, respondents may associate headaches attributed to other causes with the vaccine. An anonymous survey was distributed to the targeted vaccinated individuals, using a web-based link compatible with smartphones, tablets, laptops, and desktop PCs. Individuals were invited to volunteer for the survey using text messages and free social media platforms. Using social media platforms during the pandemic was a convenient way to increase participation in research projects (37). The purpose of the survey and the length of time it would take were explained to all invitees. The survey could be submitted after filling out the mandatory questions and filled out only once via the same device. The Alpha and Delta variants were the dominant SARS-CoV-2 variants at the time of this study, during which headache was one of the most common symptoms (38–40). This study accords with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement1 (Supplementary Table S1).

2.2. Study population

Individuals aged ≥18 who had received at least one dose of any SARS-COV-2 vaccine type, were literate enough to fill the questionnaire, and volunteered to fill out the survey were considered eligible to be included, regardless of developing post-vaccination headaches. The following individuals were excluded: (a) pediatrics, (b) people who had a history of receiving a vaccine other than the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in the last 3 months, (c) individuals with a history of substance or alcohol abuse due to their possible association with headaches (41, 42), (d) individuals who were reluctant to participate or did not provide informed consent, (e) those who answered the questions incompletely (responses missing ≥50% (43)), and (f) patients with immunocompromised conditions such as malignancies, solid organ transplantation, or inflammatory rheumatic diseases, as studies suggested different AE profile compared to immunocompetent patients (44).

2.3. Study objectives

There are three objectives of this study:

1. To investigate headache frequency and characteristics attributed to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination.

2. To determine factors associated with developing headaches following the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd doses of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination.

3. To determine factors associated with developing prolonged headaches (defined as headaches ≥48 h) following the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd dose of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination.

2.4. Study measures and definition of terms

The following information was provided, using a standardized checklist: (a) baseline demographic characteristics, (b) history and type of primary headache disorders, (c) COVID-19-related variables, (d) COVID-19-related headaches characteristics, (e) vaccine-related variables, and (f) variables attributed to the post-vaccination headaches (time to onset after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination, duration, intensity, day of experiencing the most severe headache, quality, localization, and lateralization, migraine-like accompanying symptoms, medications used, and resemblance to the either of the primary headache, post-COVID-19 headache, and headaches attributed to the previous vaccine doses).

2.4.1. Headache-related definitions

Below we have provided the definitions of the used terms, as per the ICHD-3 guideline (Definition of Terms – ICHD-3).

Primary headaches: a headache disorder, not resulting from or attributed to another condition.

Headaches attributed to COVID-19 infection: “9. Headache attributed to infection – ICHD-3” is a subset of secondary headaches. The definitions and diagnostic criteria of this classification and its subdivisions, including “9.2 Headache attributed to systemic infection – ICHD-3” and “9.2.2 Headache attributed to systemic viral infection – ICHD-3” are provided in Supplementary Table S2.

Headaches attributed to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination: although post-vaccination headaches do not fully meet the diagnostic criteria for any specific category in the ICHD-3, the category of “8.1 Headache attributed to use of or exposure to a substance – ICHD-3” and its subcategories, including “8.1.9 Headache attributed to occasional use of non-headache medication – ICHD-3” and “8.1.11 Headache attributed to use of or exposure to other substance – ICHD-3” may bear some resemblance to vaccine-related headaches. The definitions and diagnostic criteria of these headaches are provided in Supplementary Table S3. These headaches initiate in a close temporal relationship (usually within minutes up to 12 h, according to the available literature) after exposure and usually resolve within 72 h. It is worth noting that the characteristics of these specific ICHD-3 subcategories (8.1.9 and 8.1.11) are still not well-defined in the existing literature, underscoring the need for further investigation into the characteristics of these headaches as well as headaches attributed to vaccination.

Prolonged post-SARS-CoV-2 vaccination headache: given the current absence of specific criteria for post-vaccination headaches and their duration, existing literature on headaches associated with SARS-CoV-2 vaccination suggests that they generally resolve within 24–36 h from the headache onset (19, 21, 29, 30, 45). On the other hand, post-vaccination headaches lasting more than 72 h are relatively uncommon (29). Furthermore, based on the ICHD-3 guideline, headaches attributed to the use of/exposure to substances typically resolve within 72 h. Thus, it appears that vaccine-related headaches typically resolve within 24 h and do not persist beyond 72 h. Hence, in this study, we classified headaches lasting 48 h or more as “prolonged” headaches.

Resemblance of the patients’ post-vaccination headaches to their prior headaches: subjectively assessed by a general inquiry, based on the patients’ own opinion, without specifically focusing on any particular characteristics.

Headache type: a standardized checklist according to the ICHD-3 was designed to classify the post-COVID-19 and post-SARS-CoV-2 vaccination headaches (25). Based on the patient’s answers to the questions, diagnoses of migraine-like and tension-type headaches (TTH) were performed (25). If the headache did not meet the criteria for specific headaches, it was categorized as undifferentiated.

Headache intensity: categorized based on the 11-point Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) scale as mild (NRS: 1–3, not very disturbing and no or little interfering with the daily work), moderate (NRS: 4–6, uncomfortable and significantly interfering with active daily living but lets the individual do daily work), and severe (NRS: 7–10, disabling or does not allow to perform daily work) (46). NRS is a validated and sensitive scale with a high test–retest reliability for measuring headache pain, where 0 corresponds to “no headache at all” and 10 to “the worst headache possible” (47).

Headache quality: reported as sharp pain, pressing, throbbing/pulsatile sensation, and dull ache.

Headache location: regions in the head, above the orbitomeatal line, and/or nuchal ridge affected by pain.

Headache lateralization: categorized as unilateral and bilateral. Unilateral headaches were defined as headaches affecting either the right or left side, without crossing the midline. Notably, a unilateral headache may just affect the frontal, temporal, or occipital regions of the head rather than the entire right or left side.

Time to onset: temporal relation between occurring new headaches/worsening of pre-existing headaches and exposure to the vaccine/infection. Headaches attributed to the occasional use of non-headache medication usually develop within minutes to hours of intake (8.1.9 Headache attributed to occasional use of non-headache medication – ICHD-3). The corresponding value for headaches attributed to substance exposures is within 12 h of exposure (8.1.11 Headache attributed to use of or exposure to other substance – ICHD-3).

Attack duration: time from onset until termination of a headache attack, meeting criteria for a particular headache type/subtype.

Headache (end) days: number of days affected by headache for any part or the whole of the day.

2.4.2. General definitions

A definite positive history of COVID-19 was defined as having positive microbiologic testing (48). The intensity of COVID-19 was categorized as patients who needed merely outpatient care (home quarantine), those who needed ward admission, and those who received intensive medical care. Based on the most prominent symptoms, COVID-19 manifestations were described as systemic, respiratory, gastrointestinal, and neurological (vertigo, olfactory dysfunction, seizures, altered mental status, stroke, etc.). Vaccine platforms were categorized as inactivated (Sinopharm, Baharat, Barekat, Noora, and Fakhra), vector vaccines (AstraZeneca and Sputnik V), protein subunits (Spikogen, PastoCovac, and Razi-CovPars), and mRNA vaccines (Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna) (49). Fever was defined as a morning oral temperature of >37.2°C or an afternoon temperature of >37.7°C (50).

2.5. Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for numeric variables and as frequency (percentage) for categorical variables. The univariate logistic regression was used to evaluate the unadjusted impact of factors on the odds of outcomes. Moreover, age and sex were used to adjust the effect of factors on the odds of outcomes using multivariate logistic regression. All analyzes were conducted using SPSS (version 26) and R (version 4.2.1). A p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline, COVID-19-related, and vaccine-related characteristics of participants

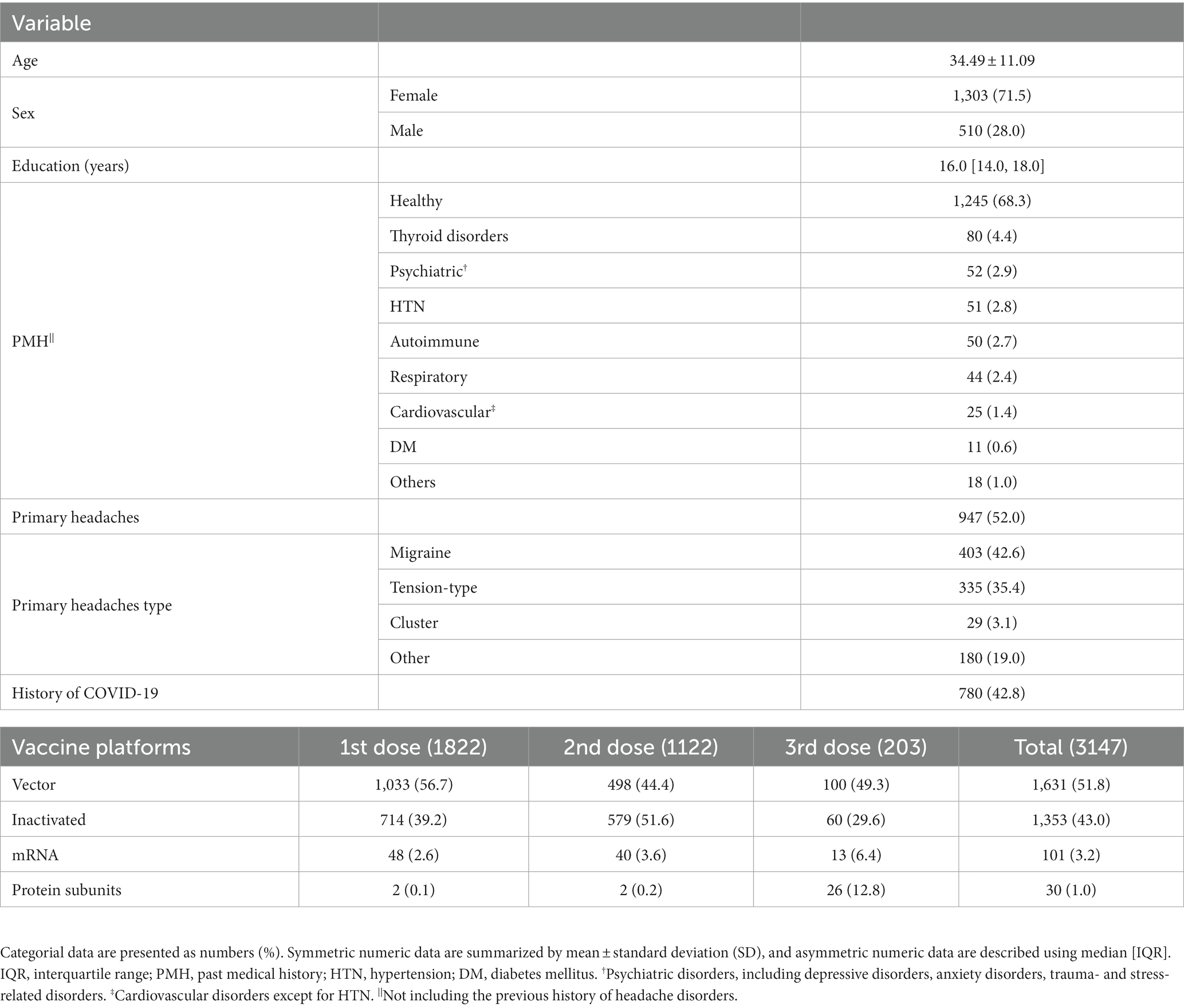

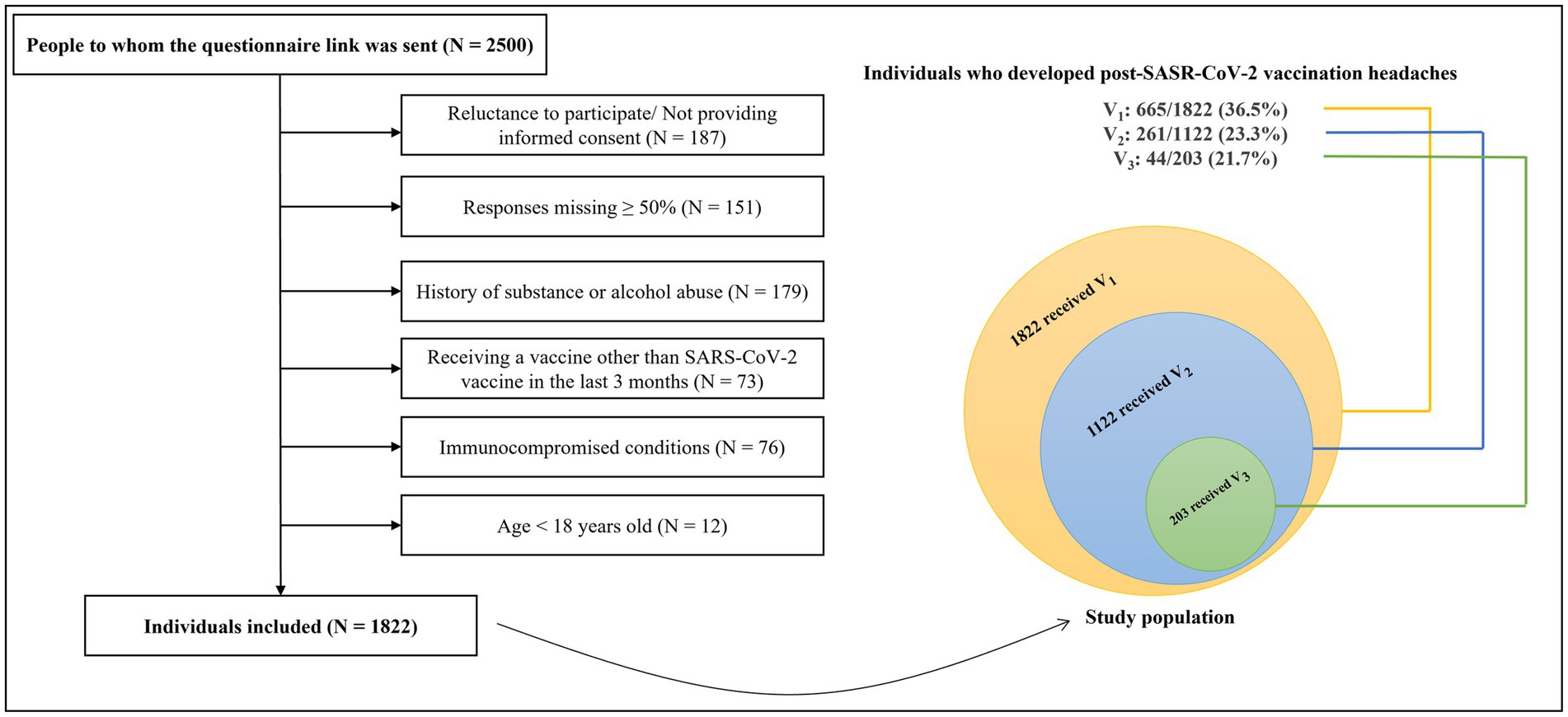

Figure 1 illustrates the participants’ flow diagram. The questionnaire link was randomly sent to 2,500 individuals, of whom 678 individuals did not meet the eligibility criteria for the following reasons: unwilling to participate or not providing informed consent (N = 187), a history of substance or alcohol abuse (N = 179), response missing ≥50% (N = 151), immunocompromised conditions (N = 76), receiving a vaccine other than SARS-CoV-2 during the last three months (N = 73), and age < 18 years old (N = 12). Eventually, 1822 individuals (mean age: 34.49 ± 11.09, female: 71.5%) were included. Among the 1822 responders, all of whom had received the 1st dose, of which 1,122 had received 2 doses, and 203 had received 3 doses, totaling 3,147 vaccination events (1st dose receivers: 1822, 2nd dose receivers: 1122, 3rd dose receivers: 203).

Figure 1. The flow diagram of participants. SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; V1, 1st vaccine dose; V2, 2nd vaccine dose; V3, 3rd vaccine dose; N, number.

Table 1 indicates participants’ baseline characteristics. Most of the participants (68.3%) reported no remarkable past medical history. A history of controlled thyroid disorder was the most frequent comorbidity (4.4%). Previous history of headache disorders was reported by 52.0% of individuals, of whom 42.6 and 35.4% had migraine and TTH, respectively. A positive COVID-19 history was reported by 42.8%. Of 3,147 total administered vaccine doses, Sinopharm (38.5%), AstraZeneca (26.6%), and Sputnik-V (25.3%) were the most injected vaccines. Post-vaccination fever was reported by 29.2% of participants. Supplementary Tables S4, S5 provide information about other COVID-19-related and vaccine-related characteristics.

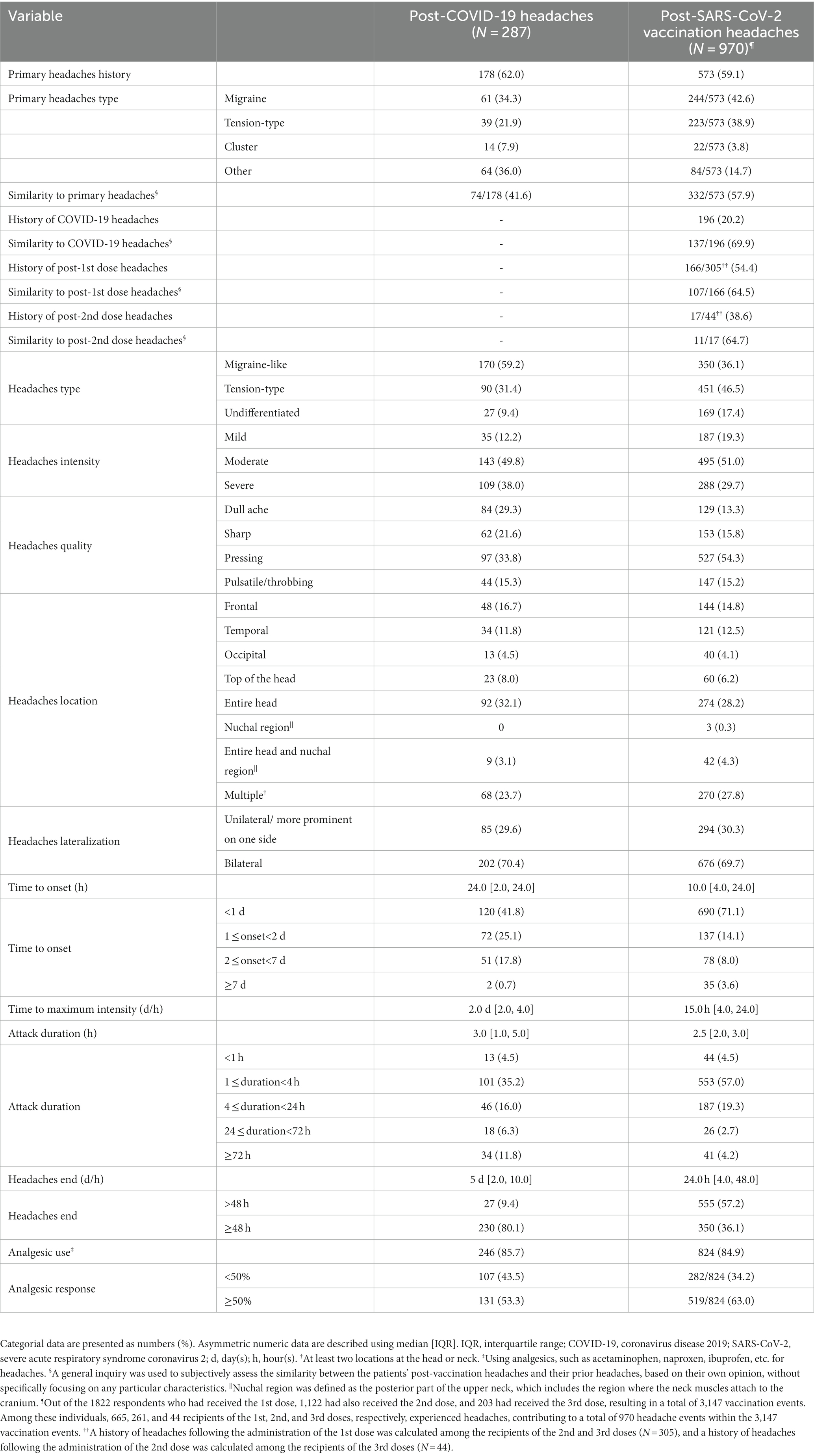

3.2. Headache characteristics attributed to COVID-19 infection

Table 2 shows headache characteristics following COVID-19 infection. Of 780 individuals with a history of COVID-19, 287 (36.8%) reported headaches attributed to COVID-19, of which 59.2 and 31.4% were migraine-like and TTH. The detailed characteristics of headaches attributed to COVID-19 infection are reported in Supplementary Result 1.

3.3. Headache characteristics attributed to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination

Table 2 shows the characteristics of headaches attributed to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. Supplementary Table S6 and Supplementary Results 2 indicate the characteristics of headache attributed to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination for each different vaccine exposure (1st, 2nd, and 3rd SARS-CoV-2 vaccine dose).

The prevalence of headaches attributed to the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd dose of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination was 36.5% (665/1822 1st dose-receivers), 23.3% (261/1122 2nd dose-receivers), and 21.7% (44/203 3rd dose-receivers), respectively (p < 0.001). Considering the total vaccination events, we found a headache prevalence of 30.8% (970/3147 total vaccination events) following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. A history of primary headaches and post-COVID-19 headaches were reported by 59.1 and 20.2% of patients who experienced post-vaccination headaches. More than half (54.4%) of the 2nd and 3rd dose-receivers who developed post-vaccination headaches had a history of headaches following the 1st dose, and 38.6% of the 3rd dose-receivers had a history of headaches following the 2nd dose. Objectively, 57.9, 69.9, and 64.5% of patients reported their post-vaccination headaches were similar to their primary headaches, post-COVID-19 headaches, and headaches following the previous vaccine doses, respectively.

Headaches attributed to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination were mostly TTH (46.5%), followed by migraine-like headaches (36.1%). They were mainly bilateral (69.7%) and moderate (51.0%), with a pressing quality (54.3%), affecting the entire head or multiple regions of the head and/or neck (56.0%). Headache onset was less than 2 days after vaccination in most of the participants (85.2%), with a median of 10 h after vaccination [4.0, 24.0] and the majority (71.1%) initiated in less than a day. Post-vaccination headaches reached their maximum intensity 15 h after vaccination [4.0, 24.0]. The median attack duration was 2.5 h [2.0, 3.0], with most of the patients (57.0%) reporting a duration between 1–4 h. Less than 7 % (6.9%) of the participants experienced attack durations of more than 24 h. The headaches ended 24 h after vaccination [4.0, 48.0], ranging from a half-hour to 21 days, with the majority ending in less than 48 h (57.2%). Of 84.9% of patients who used analgesics for their headaches, 63.0% responded more than 50%.

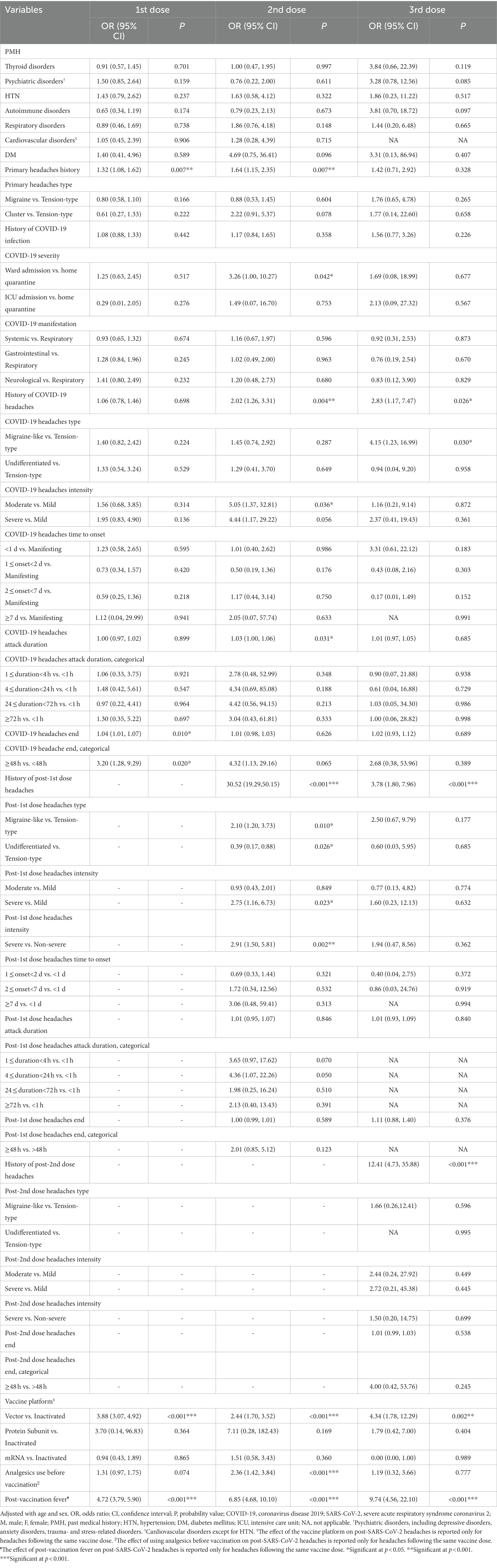

3.4. Factors associated with developing post-SARS-CoV-2 vaccination headaches

The unadjusted impact of variables on developing headaches following the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd doses are shown in Supplementary Table S7. The odds of headache slightly raised with each additional year of age (V1: OR = 1.02 [95% CI: 1.01, 1.02], p = 0.001; V2: OR = 1.03 [1.01, 1.05], p < 0.001). Furthermore, the female sex was associated with increased odds of post-SARS-CoV-2 vaccination headaches (V1: OR = 1.82 [1.45, 2.27], p < 0.001; V2: 1.67 [1.19, 2.33], p = 0.003). Table 3 indicates multivariate logistic regression results after adjusting the effect of each variable on the outcome for age and sex. Accordingly, the factors increasing the odds of post-SARS-CoV-2 vaccination headaches can be categorized as below:

(a) Factors for which significant associations were observed for three doses: headaches following the previous vaccine doses, vector vaccine platform, and post-vaccination fever.

Having a headache after each dose of the vaccine was a strong predictor of headache occurrence following the next vaccine doses; post-1st dose headaches increased the odds of post-2nd dose and 3rd dose headaches by 30.52 ([95% CI: 19.29, 50.1], p < 0.001) and 3.78 times ([1.80, 7.96], p < 0.001). Post-2nd dose headaches increased the odds of post-3rd dose headaches by 12.41 ([4.73, 35.88], p < 0.001). Vector vaccines, compared to inactivated ones, significantly increased the odds of post-SARS-CoV-2 vaccination headaches (V1: aOR = 3.88 [3.07, 4.92], p < 0.001; V2: aOR = 2.44 [1.70, 3.52], p < 0.001; V3: aOR = 4.34 [1.78, 12.29], p = 0.002). Patients who developed a fever after vaccination had significantly increased odds of post-SARS-CoV-2 vaccination headaches (V1: aOR = 4.72 [3.79, 5.90], p < 0.001; V2: aOR = 6.85 [4.68, 10.10], p < 0.001; V3: aOR = 9.74 [4.56, 22.10], p < 0.001).

(b) Factors for which significant associations were observed for two doses: history of primary headaches and post-COVID-19 headaches.

Patients with a previous history of primary headaches had increased odds of post-1st dose and 2nd dose headaches (V1: aOR = 1.32 [1.08, 1.62], p = 0.007; V2: aOR = 1.64 [1.15, 2.35], p = 0.007). However, the type of primary headaches did not significantly affect post-vaccination headaches odds. A history of developing headaches following COVID-19, increased the odds of post-2nd dose and 3rd dose headaches (V2: aOR = 2.02 [1.26, 3.31], p = 0.004; V3: aOR = 2.83 [1.17, 7.47], p = 0.026).

(c) Factors for which significant associations were observed for one dose: COVID-19 severity, some characteristics of post-COVID-19 headaches (migraine-like, moderate intensity, longer attack durations, longer days of having headaches), and some characteristics of headaches after the previous vaccine dose (migraine-like, severe).

Although a history of COVID-19 did not significantly affect post-vaccination headaches odds, compared to patients who were quarantined at home, those who were hospitalized in the ward had higher odds of developing post-2nd dose headaches (aOR = 3.26 [1.00, 10.27], p = 0.042). Individuals whose COVID-19 headache was migraine-like, compared to TTH, had significantly higher odds of developing post-3rd dose headaches (aOR = 4.15 [1.23, 16.99], p = 0.030). Furthermore, compared to the mild intensity, post-COVID-19 headaches with moderate intensity increased the odds of post-2nd dose headache (aOR = 5.05 [1.37, 32.81], p = 0.036). Furthermore, each hour of increased duration of post-COVID-19 headache attacks slightly increased the odds of post-2nd dose headaches (aOR = 1.03 [1.00, 1.06], p = 0.031), and each day that the COVID-19 headache lasted longer slightly increased the likelihood of post-1st dose headaches (aOR = 1.04 [1.01, 1.07], p = 0.010). People whose headaches following COVID-19 lasted more than 48 h were 3.2 times ([1.28, 9.29], p = 0.020) more likely to develop post-1st dose headaches. Individuals with migraine-like post-1st dose headaches had increased odds of developing post-2nd dose headaches (aOR = 2.10 [1.20, 3.73], p = 0.010). Furthermore, patients with severe post-1st dose headaches, compared to non-severe headaches, had increased odds of post-2nd dose headaches (aOR: 2.91 [1.50, 5.81], p = 0.002).

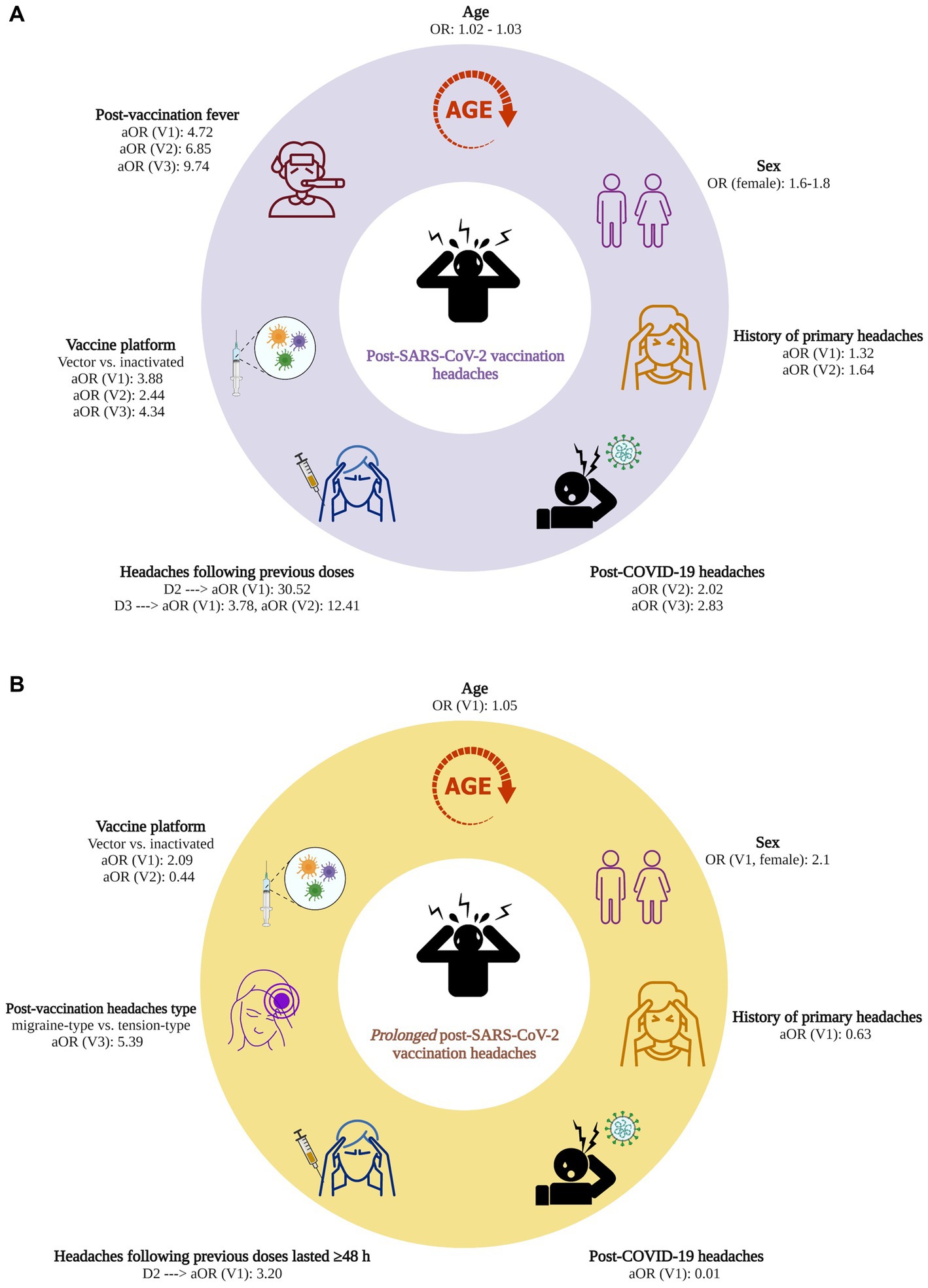

Figure 2A illustrates the factors associated with developing post-SARS-CoV-2 vaccination headaches, for which significant associations were observed for at least two vaccine doses.

Figure 2. (A) Factors associated with post-SARS-CoV-2 vaccination headaches. (B) Factors associated with prolonged (≥ 48 h) post-SARS-CoV-2 vaccination headaches. OR, odds ratio; aOR, adjusted odds ratio; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; V1, 1st vaccine dose; V2, 2nd vaccine dose; V3, 3rd vaccine dose; Created with BioRender.com.

3.5. Factors associated with developing prolonged (≥ 48 h) post-SARS-CoV-2 vaccination headaches

Supplementary Table S8 shows the unadjusted impact of variables on developing prolonged post-SARS-CoV-2 vaccination headaches. Each year of increased age slightly increased the odds of prolonged post-1st dose headaches (OR = 1.05 [1.03, 1.07], p < 0.001). Being female was also associated with increased odds of prolonged post-1st dose headache (OR = 2.13 [1.33, 3.45], p = 0.002). Table 4 displays multivariate logistic regression results after adjusting the effect of each variable on the outcome for age and sex. Accordingly, the factors associated with developing prolonged post-SARS-CoV-2 vaccination headaches can be categorized as below:

(a) Factors increasing the odds of prolonged post-vaccination headaches (associations were observed only for one dose): psychiatric disorders, prolonged headaches after the previous dose, and migraine-like headaches at the same dose.

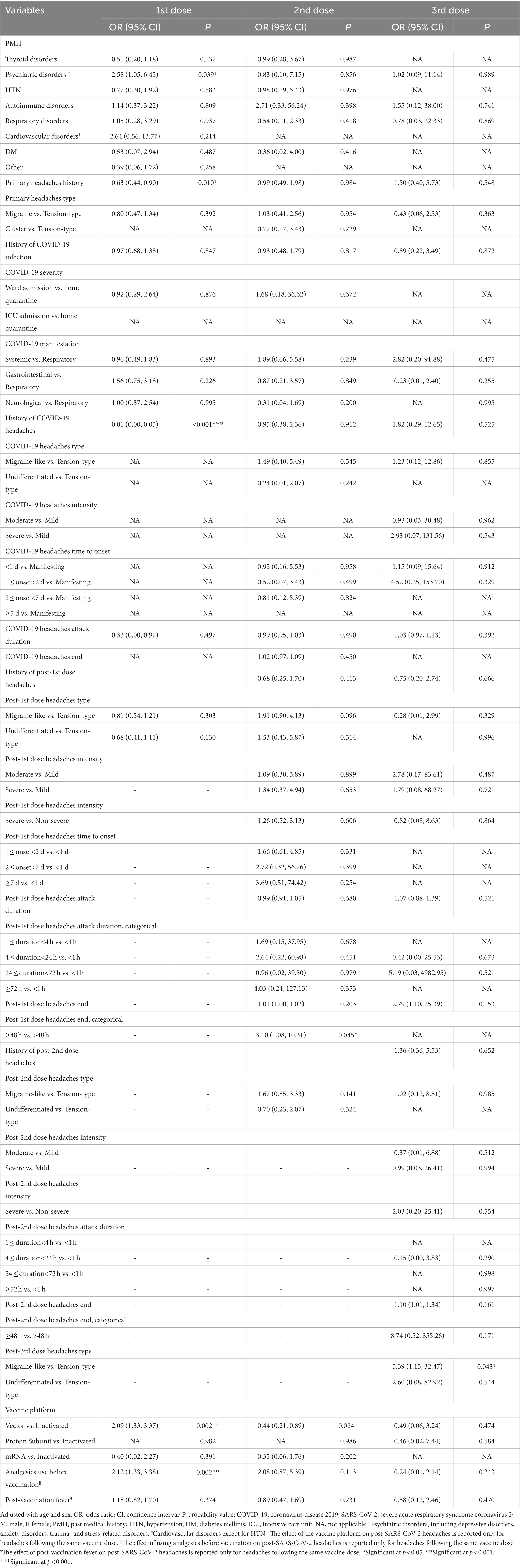

Table 4. Adjusted impact of variables on developing prolonged headache following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination.

Patients with a history of psychiatric disorders [defined as depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, trauma- and stress-related disorders (51)] had increased odds of prolonged post-1st dose headaches (aOR: 2.58 [1.05, 6.45], p = 0.039). Prolonged post-1st dose headaches significantly increased the odds of prolonged post-2nd dose headaches (aOR = 3.10 [1.08, 10.31], p = 0.045). The odds of prolonged post-3rd dose headaches was significantly increased in patients who experienced migraine-like, compared to the TTH, after receiving the 3rd dose (aOR = 5.39 [1.15, 32.47], p = 0.043).

(b) Factors reducing the odds of prolonged post-vaccination headaches (associations were observed only for one dose): history of primary headaches and post-COVID-19 headaches.

Having a history of primary headaches reduced the odds of prolonged post-1st dose headaches (aOR = 0.63 [0.44, 0.90], p = 0.010). Similarly, a history of developing headaches following COVID-19 significantly reduced the odds of prolonged post-1st dose headaches (aOR = 0.01 [0.00, 0.05], p < 0.001).

(c) Factors with inconsistent effects on the odds of prolonged post-vaccination headaches: vaccine platform

Compared to the inactivated vaccine platforms, vector platforms significantly increased the odds of prolonged post-1st dose headaches (aOR = 2.09 [1.33, 3.37], p = 0.002). Nevertheless, they reduced the odds of post-2nd dose headaches (aOR = 0.44 [0.21, 0.89], p = 0.024).

Figure 2B displays the factors significantly associated with prolonged post-vaccination headaches.

4. Discussion

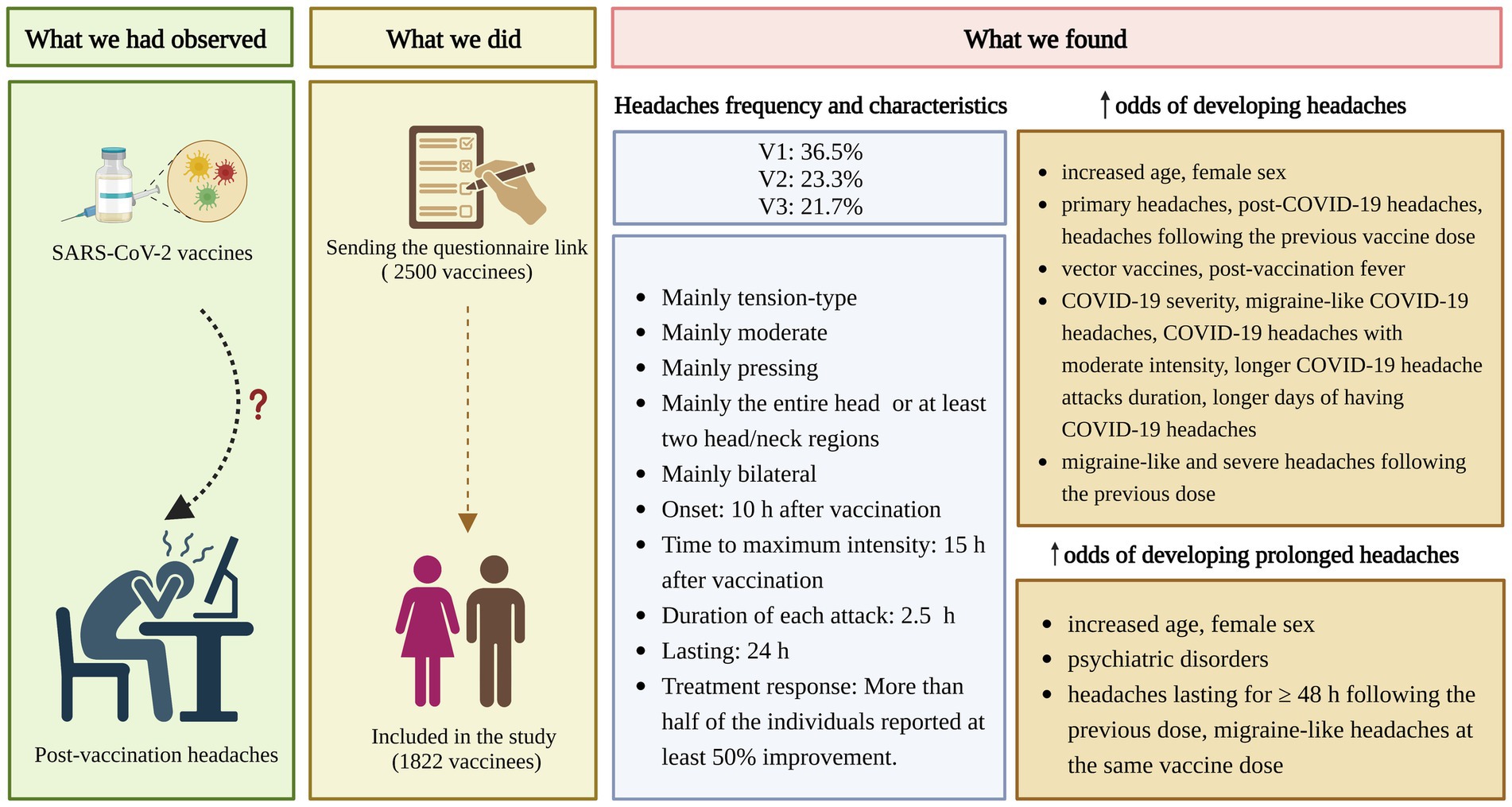

Figure 3 provides an overview of the study with the key findings. We found a total post-SARS-CoV-2 vaccination headache prevalence of 30.8%. The occurrence of post-vaccination headaches decreased with increased exposure (36.5, 23.3, and 21.7% following the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd dose, respectively). More than half (59.1%) of the individuals who developed post-SASR-CoV-2 vaccination headaches reported having primary headaches. Similarity between post-vaccination headaches and primary headaches, post-COVID-19 headaches, and headaches following the previous doses was reported by 57.9, 69.9, and 64.5% of individuals, respectively. Headaches were mostly TTH (46.5%). Headaches were usually moderate (51.0%), bilateral (69.7%), pressing (54.3%), and responsive to analgesics (63.0%), affecting the entire head or multiple regions of the head/neck (56.0%). They usually started 10 h after vaccination, reached their maximum intensity 15 h after vaccination, and ended 24 h later. Each attack duration was nearly 2.5 h. Initiating headaches≥ two days after vaccination and attack durations of≥24 h were not common.

Figure 3. Research summary. COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; V1, 1st vaccine dose; V2, 2nd vaccine dose; V3, 3rd vaccine dose; h, hour; Created with BioRender.com.

Increased age, being female, primary headaches, post-COVID-19 headaches, headaches following previous doses, vector vaccines, and post-vaccination fever increased post-SARS-CoV-2 vaccination headache odds. Other possible associated factors were COVID-19 severity, COVID-19 headaches characteristics (migraine-like, moderate intensity, longer attack duration, and longer days of COVID-19 headaches), and some headaches characteristics after the previous dose (migraine-like and severe headaches). Primary headaches and post-COVID-19 headaches reduced the odds of prolonged post-vaccination headaches. Increased age, being female, psychiatric disorders, prolonged headaches following the previous dose, and migraine-like headaches at the same dose may increase prolonged post-vaccination headaches odds. The effect of vector platforms on prolonged post-vaccination headaches requires further investigation. Notably, the observation that significant associations between specific variables and outcome measures did not apply to all three doses might reflect that vaccine dose has shown to be one of the strongest factors associated with vaccination AEs (52).

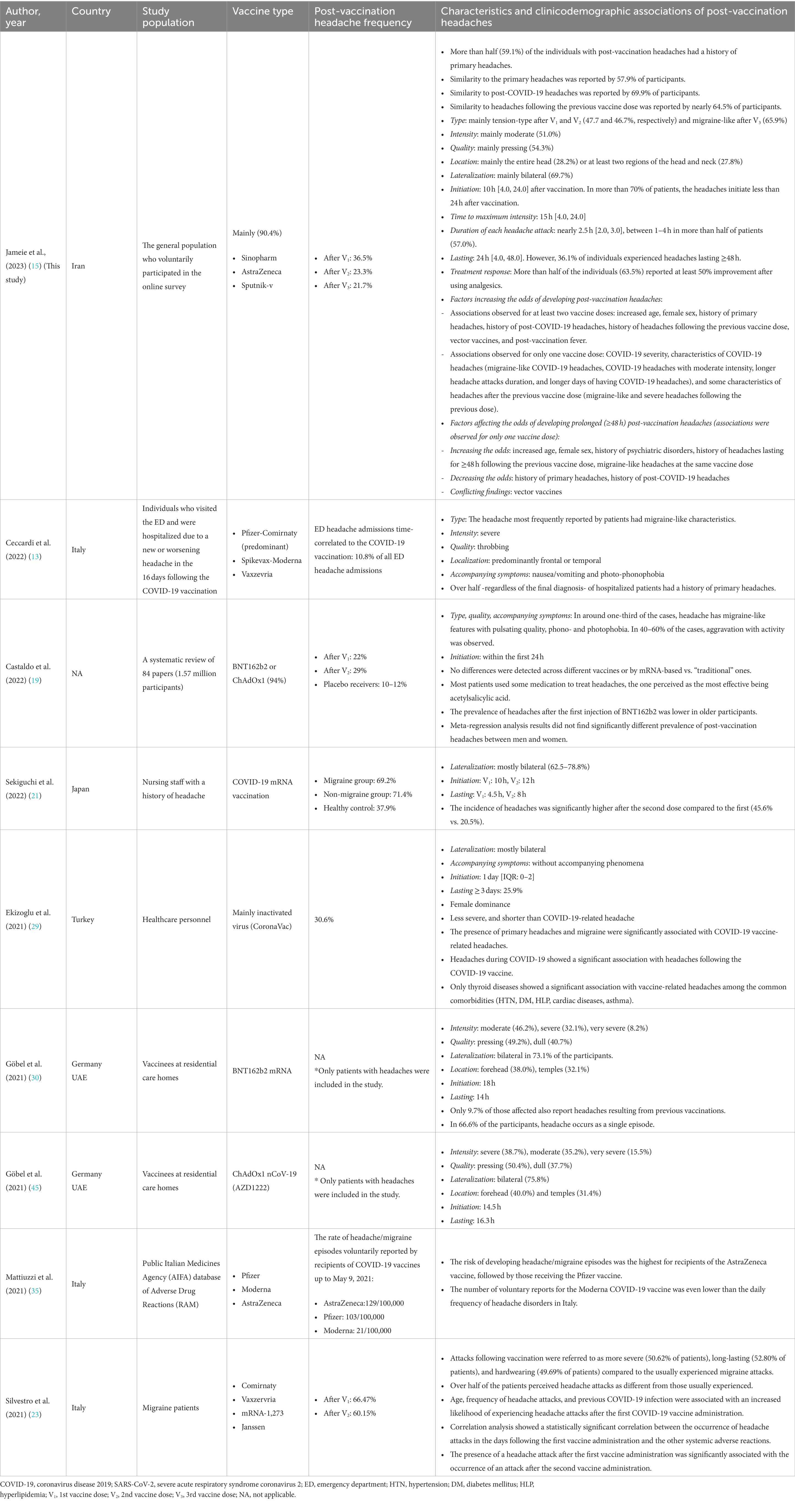

4.1. Prevalence and characteristics of headaches attributed to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination

Table 5 provides an overview of the literature related to post-SARS-CoV-2 vaccination headaches. A meta-analysis by Castaldo et al. on nearly 1.57 million vaccine receivers suggested that SARS-CoV-2 vaccines were associated with a two-fold increased risk of developing headaches within 7 days from the injection (19). The authors found a post-1st dose and 2nd dose headaches prevalence of 22 and 29%, respectively (19), which accords with our findings. Although we found that the occurrence of post-vaccination headaches decreased with increased exposure, to our knowledge, there is no clear evidence as to how the occurrence of post-vaccination headaches alters with further doses. According to Sekiguchi et al. cross-sectional study, the incidence of headaches was significantly higher after the 2nd dose compared to the 1st (21). However, this study was conducted on patients with a history of headaches, and it is not clear if the same applies to the general population (21). Further research is necessary to provide a comprehensive response to this inquiry. Consistent with our findings, Ekizoglu et al. study found a post-vaccination frequency of 30.6% (29). Another cross-sectional study among hospital health workers reported the headache prevalence of 48.8 and 33.5% after the 1st and 2nd dose (53), higher than what we observed. This difference can be justified by different study populations (healthcare workers vs. the general population). Silvestro et al. study on 841 migraine participants found higher post-vaccination headaches prevalence of 66.5 and 60.2% after the 1st and 2nd dose (23), supporting the idea that primary headaches are linked to an increased risk of developing headaches following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination.

In line with our findings, Ekizoglu et al. revealed that post-vaccination headaches are usually bilateral (29). Göbel et al. reported that post-ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccination headaches are usually bilateral, with a pressing character (30). On the other hand, Ceccardi et al. study suggested different headaches characteristics following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination among patients who were admitted to the emergency department (ED) or hospitalized due to post-vaccination headaches; headaches were usually severe with a throbbing quality in this subgroup (13). Additionally, while we found TTH was the predominant headache type following the 1st and 2nd doses, their study indicated that migraine-like headache characteristics were reported by most patients (13), which could be a reflection of the different populations of their study (ED admission) compared to ours (general population). Our study revealed a frequency of 33.8 and 36.8% of migraine-like headaches after the 1st and 2nd doses. These results reflect those of Castaldo et al. meta-analysis, who also found migraine-like characteristics in about one-third of vaccinees who developed headaches (19).

Our finding broadly supports the work of other studies regarding the other characteristics of post-vaccination headaches; post-vaccination headaches usually initiate less than a day after vaccination, and delayed headache onset should be considered a red flag for serious conditions, such as vaccine-induced CVT (26). According to Ekizoglu et al. study, post-vaccination headaches initiated nearly 1 day [0–2] after vaccination (29). Consistently, Castaldo et al. meta-analysis showed that post-vaccination headaches are usually reversible, with onset within a few hours after the vaccination (19). Furthermore, we found that post-vaccination headaches occurred with a median of 10 h following vaccination, emphasizing that very early headache onset should also be investigated. Accordingly, previous studies have also highlighted that in patients with headaches beginning immediately after vaccination, physicians should be aware of other underlying causes, such as CVT (26). Notably, our study indicated that post-vaccination headaches responded well to analgesics in 63.0% of individuals, contrary to the existing knowledge about vaccine-induced CVT, which is usually treatment resistant (19).

4.2. Post-vaccination headaches resemblance to primary headaches and post-COVID-19 headaches

According to Göbel et al., post-vaccination headaches had a distinct phenotypic profile from primary headaches (30). Consistently, more than half of the migraineurs in the Silvestro et al. study reported their post-vaccination headaches were “different” from their primary headaches; they were more severe, long-lasting, and hardwearing (23). Notably, 57.9% of our study participants reported their post-vaccination headaches were “similar” to their primary headaches. This difference in findings may be due to the differences in the definition of our study (without focusing on any particular characteristics) with Silvestro et al. study (asking specifically about differences in intensity, duration, and response to painkillers), necessitating further investigation.

In our study, compared to the COVID-19 headaches, post-vaccination headaches initiated earlier (10 h after vaccination vs. 24 h after the infection) and lasted shorter (24 h after vaccination vs. 5 days after the infection). In alignment with our findings, Ekizoglu et al. study demonstrated that post-vaccination headaches are less severe and shorter than post-COVID-19 headaches (29).

4.3. Factors associated with developing headaches following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination

4.3.1. Age and sex

Although in our study, the odds of headache following vaccination increased slightly with age, the odds of headache in the Silvestro et al. study slightly reduced with increased age, hence the necessity of further investigations in this regard. Similar to our findings, Ekizoglu et al. study suggested female dominance for post-vaccination headaches (29). Consistently, according to Al-Qazaz et al., women experienced significantly greater rates of severe and moderate systemic AEs, including headaches, following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination (54). Nevertheless, the results of a meta-regression analysis to address the effect of sex on post-vaccination headaches did not find a significantly different prevalence of post-vaccination headaches between men and women (19).

4.3.2. Primary headaches

Consistent with the literature (13, 21, 29), we found a significant association between primary headaches and headaches following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. A study by Sekiguchi et al. demonstrated post-vaccination headache frequency of 37.9% in individuals without a headache history, while 69.2 and 71.4% in those with a history of migraine and non-migraine headaches, respectively (21). Consistently, Ekizoglu et al. study identified that post-vaccination headaches occurred in 21.1% of those without a history of headaches, while 38.8% of those with a history of headaches (29). The authors indicated that the presence of primary headaches increased the odds of developing post-vaccination headaches (29).

4.3.3. Post-COVID-19 headaches and headaches following the previous vaccine dose

Our results also reflect those of Silvestro et al., who indicated that developing headaches following COVID-19 increased the odds of developing post-vaccination headaches (23). Ekizoglu et al. also found a significant association between post-COVID-19 headaches and developing headaches following vaccination (29). Although the exact pathophysiology behind this correlation is not well understood, some evidence has suggested similar cytokine-mediated pathomechanisms in these clinical circumstances, which is not unexpected given the role of neuroinflammation in neurological diseases (55–57). Consistent with our findings, Silvestro et al. study indicated that an attack following the 2nd dose was considerably more likely to occur if a headache episode had occurred following the 1st dose (23).

4.3.4. Vaccine platform

Headache frequencies reported after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination varied widely between mRNA, adenovirus vector, and inactivated virus (29). This accords with our observations that post-vaccination headaches are more commonly associated with vector vaccines. In corroboration with our findings, a study by Mattiuzzi et al. reported that post-vaccination headaches occurred more frequently among AstraZeneca recipients, followed by Pfizer recipients (35). Similarly, a study among 334 healthcare workers with a history of COVID-19 reported vaccine type as one of the main predictors of post-vaccination headaches, with the highest rate observed for AstraZeneca and Sputnik V (58). Nevertheless, a recent meta-analysis found no significant difference between vaccine types in terms of developing post-vaccination headaches, suggesting these headaches might be secondary to systemic immunological responses than to vaccine-specific reactions (19). It should be noted that more than 90% of individuals in this study received BNT162b2 or ChAdOx1 (19). Generally, with respect to the conflicting results and diverse platforms used in different countries, further investigations and updated meta-analyses might be required to shed light on the effect of different vaccine platforms on post-vaccination headaches.

4.3.5. Fever

Post-vaccination fever was found to be another factor associated with post-vaccination headaches. According to Göbel et al. study, 30.4% of individuals who developed post-vaccination headaches reported fever. Therefore, the authors suggested that inflammatory mediators may play a role in headaches associated with vaccination (30). Our finding also reflects that of Silvestro et al., who indicated a statistically significant relationship between post-vaccination headache attacks and other systemic AEs (23).

4.4. Factors associated with developing prolonged headaches following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination

To our knowledge, while there are studies evaluating factors associated with prolonged post-COVID-19 headaches (59), no study has been conducted before to specifically investigate the risk factors associated with prolonged headaches following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. Hence, the literature is still very limited in this field. According to our results, a history of psychiatric disorders may increase the odds of long-lasting headaches following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. Notably, epidemiological data indicate that unidirectional/bidirectional causal associations between psychiatric disorders and headaches are possible (51). While we found that a history of primary headaches or headaches following COVID-19 might reduce the odds of developing prolonged post-vaccination headaches, Göbel et al. indicated a longer duration of post-vaccination headaches in patients with a history of migraine compared to those without primary headaches (30). According to the authors, the hyperexcitability of trigeminovascular neurons caused by the primary headaches might be attributed to headaches lasting longer following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination (30). However, it can also be hypothesized that people who have had a previous history of headaches may possess better strategies for effectively managing their post-vaccination headaches, potentially leading to the prevention of prolonged headache episodes. More studies are required to enlighten these issues, as well as the effect of other clinicodemographic features (i.e., age, sex, long-lasting headaches following the previous dose, post-vaccination headache type, and vaccine platform) on prolonged post-vaccination headaches.

4.5. Limitations and strengths

Our study has several limitations. There were disproportionately more women than men in the sample. Furthermore, although random selection facilitated providing a representative sample of vaccine receivers within the healthcare system and reducing the selection bias, people who did not respond to the invitation might have had lower education or lower socioeconomic status, since the utilization of a web-based questionnaire distributed via social media platforms might be less feasible among these groups. This, in turn, may have influenced the reported prevalence of post-vaccination headaches in this study, as individuals with higher education levels may exhibit greater awareness and a higher tendency to report such cases. Additionally, as with previous studies, people with a history of primary headaches or with more severe headaches, as well as those who developed post-vaccination headaches, might have been more willing to engage in this study and, therefore, might be overrepresented. Another possible limitation of the current study, as with other studies, is the possible confounding effect of apprehension about the vaccines’ safety on developing headaches following vaccination.

This study may also be subject to recall bias (responder bias) due to the retrospective recollection retrieved by study participants and the questionnaire-based nature (Recall bias – Catalog of Bias). However, to reduce the recall bias, we tried to define each question and related options clearly to the participant, and the participants also had enough time for adequate recall of long-term memory. Additionally, the questionnaire was designed in chronological events order (history of primary headaches, COVID-19-related headaches, post-1st dose, post-2nd dose, and post-3rd dose headaches). To ensure that no important information from the perspective of the patients was overlooked, open-ended responses were also given and evaluated by an experienced neurologist. To further minimize recall bias, we made an effort to select a reasonable interval (one month) between the last vaccine dose and the distribution of the questionnaires, ensuring it was neither too short nor too long. The strengths of this study include large sample size, a population-based design, the inclusion of different vaccine platforms, and different doses. Of note, since the 3rd dose was taken months apart, the number of events related to this dose was considerably lower. Despite its limitations, this study certainly adds to our understanding of the features and risk factors for post-vaccination headaches and headaches after multiple vaccine doses.

5. Conclusions and further directions

Headaches following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination are common adverse events, typically bilateral, moderate, pressing, and responsive to analgesics. They usually occur with a close temporal relationship (10 h) to vaccination and last for nearly 24 h. Factors increasing the risk of post-vaccination headaches include primary headaches, post-COVID-19 headaches, prior vaccine-related headaches, vector-based vaccines, and post-vaccination fever. Primary and post-COVID-19 headaches decrease the likelihood of prolonged post-vaccination headaches, while longer-lasting prior vaccine-related headaches, migraine-like headaches at the same dose, and psychiatric disorders increase the odds of prolonged headaches after vaccination. Understanding the characteristics and risk factors associated with these headaches can help physicians diagnose these headaches and distinguish them from more serious causes (such as CVT) and may also enhance vaccine acceptance and coverage. While studying the factors associated with developing post-vaccination headaches, future studies should take some possible confounding factors (i.e., apprehension about vaccine AEs) into account. Additionally, it is important to note that not all vaccine types may carry the same risk of headaches. Therefore, continued efforts are needed to determine factors associated with headaches and, specifically, prolonged headaches following vaccination with various SARS-CoV-2 vaccine platforms. In future studies examining vaccine AEs, it is crucial to consider the vaccine dose as a significant factor, as it has been identified as one of the strongest factors associated with AEs. Lastly, given the high prevalence of headaches attributed to vaccination, continued efforts are needed to update the current ICHD-3 classification system to include vaccines as one of the substances listed in 8.1 Headache attributed to use of or exposure to a substance – ICHD-3.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon reasonable request, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the ethics committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran (IR.TUMS.NI.REC.1400.054). Patients gave their written informed consent for participation and publishing, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Author contributions

MT, EJ, and SN: conception and design. MAL, MJ, and NH: analysis. MJ, MAL, and MYP: interpretation of data. MJ and MYP: drafting. MT, EJ, SN, MAL, and NH: revising. All authors approved the final version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate Ms. Zeinab Ghorbani, Ms. Jaleh Salami, and Dr. Mahsa Babaei’s assistance in distributing the online questionnaires, as well as the participation of all those who made this research possible.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2023.1214501/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

CI, Confidence interval; COVID-19, Coronavirus disease 2019; CVT, Cerebral venous thrombosis; V1, 1st vaccine dose; V2, 2nd vaccine dose; V3, 3rd vaccine dose; ICU, Intensive care unit; OR, Odds ratio; P, Probability value; PMH, Past medical history; SARS-CoV-2, Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

Footnotes

References

1. GBD Compare Data Visualization. Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). Seattle, WA: IHME, University of Washington (2020).

2. Steiner, TJ, Stovner, LJ, Vos, T, Jensen, R, and Katsarava, Z. Migraine is first cause of disability in under 50s: Will health politicians now take notice?, Berlin: Springer. (2018). 1–4, 19.

3. Stovner, L, Hagen, K, Jensen, R, Katsarava, Z, Lipton, R, Scher, A, et al. The global burden of headache: a documentation of headache prevalence and disability worldwide. Cephalalgia. (2007) 27:193–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2007.01288.x

4. Stovner, LJ, Hagen, K, Linde, M, and Steiner, TJ. The global prevalence of headache: an update, with analysis of the influences of methodological factors on prevalence estimates. J Headache Pain. (2022) 23:34. doi: 10.1186/s10194-022-01402-2

5. Headache disorders. World Health Organization (2022). Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/headache-disorders (Accessed May 05, 2022).

6. Chen, X, Laurent, S, Onur, OA, Kleineberg, NN, Fink, GR, Schweitzer, F, et al. A systematic review of neurological symptoms and complications of COVID-19. J Neurol. (2021) 268:392–402. doi: 10.1007/s00415-020-10067-3

7. Islam, MA, Alam, SS, Kundu, S, Hossan, T, Kamal, MA, and Cavestro, C. Prevalence of headache in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a systematic review and meta-analysis of 14,275 patients. Front Neurol. (2020) 11:562634. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.562634

8. Togha, M, Hashemi, SM, Yamani, N, Martami, F, and Salami, Z. A review on headaches due to COVID-19 infection. Front Neurol. (2022) 13:942956. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2022.942956

9. Rafati, A, Pasebani, Y, Jameie, M, Yang, Y, Jameie, M, Ilkhani, S, et al. Association of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination or infection with bell palsy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Otolaryngol. (2023) 149:493–504. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2023.0160

10. Waliszewska-Prosół, M, and Budrewicz, S. The unusual course of a migraine attack during COVID-19 infection – case studies of three patients. J Infect Public Health. (2021) 14:903–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2021.04.013

11. COVID-19 Vaccines are Effective. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2022). Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/effectiveness/index.html (Accessed May 05, 2022).

13. Ceccardi, G, di Cola, FS, Di Cesare, M, Liberini, P, Magoni, M, Perani, C, et al. Post COVID-19 vaccination headache: a clinical and epidemiological evaluation. Front Pain Res. (2022) 3:3. doi: 10.3389/fpain.2022.994140

14. Goss, AL, Samudralwar, RD, Das, RR, and Nath, A. ANA investigates: neurological complications of COVID-19 vaccines. Ann Neurol. (2021) 89:856–7. doi: 10.1002/ana.26065

15. Jameie, M, Togha, M, Looha, MA, Hemmati, N, Jafari, E, Nasergivehchi, S, et al. Clinical characteristics and factors associated with headaches following COVID-19 vaccination: A cross-sectional cohort study (P14-12.003). New York: AAN Enterprises (2023).

16. Avasarala, J, McLouth, CJ, Pettigrew, LC, Mathias, S, Qaiser, S, and Zachariah, P. VAERS-reported new-onset seizures following use of COVID-19 vaccinations as compared to influenza vaccinations. Br J Clin Pharmacol. (2022) 88:4784–8. doi: 10.1111/bcp.15415

17. Gee, J, Marquez, P, Su, J, Calvert, GM, Liu, R, Myers, T, et al. First month of COVID-19 vaccine safety monitoring—United States, December 14, 2020–January 13, 2021. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. (2021) 70:283–8. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7008e3

18. Shay, DK. Safety monitoring of the Janssen (Johnson & Johnson) COVID-19 vaccine—United States, march–April 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. (2021) 70:680–4. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7018e2

19. Castaldo, M, Waliszewska-Prosół, M, Koutsokera, M, Robotti, M, Straburzyński, M, Apostolakopoulou, L, et al. Headache onset after vaccination against SARS-CoV-2: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. J Headache Pain. (2022) 23:41. doi: 10.1186/s10194-022-01400-4

20. Caronna, E, van den Hoek, TC, Bolay, H, Garcia-Azorin, D, Gago-Veiga, AB, Valeriani, M, et al. Headache attributed to SARS-CoV-2 infection, vaccination and the impact on primary headache disorders of the COVID-19 pandemic: a comprehensive review. Cephalalgia. (2023) 43:3331024221131337. doi: 10.1177/03331024221131337

21. Sekiguchi, K, Watanabe, N, Miyazaki, N, Ishizuchi, K, Iba, C, Tagashira, Y, et al. Incidence of headache after COVID-19 vaccination in patients with history of headache: a cross-sectional study. Cephalalgia. (2022) 42:266–72. doi: 10.1177/03331024211038654

22. Brandt, RB, Ouwehand, R-LH, Ferrari, MD, Haan, J, and Fronczek, R. COVID-19 vaccination-triggered cluster headache episodes with frequent attacks. Cephalalgia. (2022) 42:1420–4. doi: 10.1177/03331024221113207

23. Silvestro, M, Tessitore, A, Orologio, I, Sozio, P, Napolitano, G, Siciliano, M, et al. Headache worsening after COVID-19 vaccination: an online questionnaire-based study on 841 patients with migraine. J Clin Med. (2021) 10:5914. doi: 10.3390/jcm10245914

24. Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) Publications. Center for disease control and prevention (2022). Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccinesafety/ensuringsafety/monitoring/vaers/publications.html (Accessed May 17, 2022).

25. Arnold, M. Headache classification committee of the international headache society (IHS) the international classification of headache disorders. Cephalalgia. (2018) 38:1–211. doi: 10.1177/0333102417738202

26. García-Azorín, D, Do, TP, Gantenbein, AR, Hansen, JM, Souza, MNP, Obermann, M, et al. Delayed headache after COVID-19 vaccination: a red flag for vaccine induced cerebral venous thrombosis. J Headache Pain. (2021) 22:108. doi: 10.1186/s10194-021-01324-5

27. Vegezzi, E, Ravaglia, S, Buongarzone, G, Bini, P, Diamanti, L, Gastaldi, M, et al. Acute myelitis and ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine: casual or causal association? J Neuroimmunol. (2021) 359:577686. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2021.577686

28. Wolthers, SA, Stenberg, J, Nielsen, HB, Stensballe, J, and Pedersen, HP. Intracerebral haemorrhage twelve days after vaccination with ChAdOx1 nCoV-19. Ugeskr Laeger. (2021) 183

29. Ekizoglu, E, Gezegen, H, Yalınay Dikmen, P, Orhan, EK, Ertaş, M, and Baykan, B. The characteristics of COVID-19 vaccine-related headache: clues gathered from the healthcare personnel in the pandemic. Cephalalgia. (2022) 42:366–75. doi: 10.1177/03331024211042390

30. Göbel, CH, Heinze, A, Karstedt, S, Morscheck, M, Tashiro, L, Cirkel, A, et al. Headache attributed to vaccination against COVID-19 (coronavirus SARS-CoV-2) with the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 (AZD1222) vaccine: a Multicenter observational cohort study. Pain Ther. (2021) 10:1309–30. doi: 10.1007/s40122-021-00296-3

31. Babaee, E, Amirkafi, A, Tehrani-Banihashemi, A, SoleimanvandiAzar, N, Eshrati, B, Rampisheh, Z, et al. Adverse effects following COVID-19 vaccination in Iran. BMC Infect Dis. (2022) 22:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12879-022-07411-5

32. Pourakbari, B, Mirbeyk, M, Mahmoudi, S, Hosseinpour Sadeghi, RH, Rezaei, N, Ghasemi, R, et al. Evaluation of response to different COVID-19 vaccines in vaccinated healthcare workers in a single center in Iran. J Med Virol. (2022) 94:5669–77. doi: 10.1002/jmv.28029

33. Magdy, R, Hussein, M, Ragaie, C, Abdel-Hamid, HM, Khallaf, A, Rizk, HI, et al. Characteristics of headache attributed to COVID-19 infection and predictors of its frequency and intensity: a cross sectional study. Cephalalgia. (2020) 40:1422–31. doi: 10.1177/0333102420965140

34. Trigo, J, García-Azorín, D, Planchuelo-Gómez, Á, Martínez-Pías, E, Talavera, B, Hernández-Pérez, I, et al. Factors associated with the presence of headache in hospitalized COVID-19 patients and impact on prognosis: a retrospective cohort study. J Headache Pain. (2020) 21:94. doi: 10.1186/s10194-020-01165-8

35. Mattiuzzi, C, and Lippi, G. Headache after COVID-19 vaccination: updated report from the Italian Medicines Agency database. Neurol Sci. (2021) 42:3531–2. doi: 10.1007/s10072-021-05354-4

36. Association WM. World medical association declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. (2013) 310:2191–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053

37. Sathish, R, Manikandan, R, Priscila, SS, Sara, BV, and Mahaveerakannan, R. A report on the impact of information technology and social media on COVID–19. 2020 3rd International Conference on Intelligent Sustainable Systems (ICISS). (2020). IEEE.

38. Sheikhi, F, Yousefian, N, Tehranipoor, P, and Kowsari, Z. Estimation of the basic reproduction number of alpha and Delta variants of COVID-19 pandemic in Iran. PLoS One. (2022) 17:e0265489. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0265489

39. Zali, A, Khodadoost, M, Gholamzadeh, S, Janbazi, S, Piri, H, Taraghikhah, N, et al. Mortality among hospitalized COVID-19 patients during surges of SARS-CoV-2 alpha (B.1.1.7) and delta (B.1.617.2) variants. Sci Rep. (2022) 12:23312. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-23312-8

40. Kläser, K, Molteni, E, Graham, M, Canas, LS, Österdahl, MF, Antonelli, M, et al. COVID-19 due to the B.1.617.2 (Delta) variant compared to B.1.1.7 (alpha) variant of SARS-CoV-2: a prospective observational cohort study. Sci Rep. (2022) 12:14016. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-14016-0

41. Panconesi, A, Bartolozzi, ML, Mugnai, S, and Guidi, L. Alcohol as a dietary trigger of primary headaches: what triggering site could be compatible? Neurol Sci. (2012) 33:203–5. doi: 10.1007/s10072-012-1068-z

42. Beckmann, YY, Seçkin, M, Manavgat, Aİ, and Zorlu, N. Headaches related to psychoactive substance use. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. (2012) 114:990–9. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2012.02.041

43. Togha, M, Rafiee, P, Ghorbani, Z, Khosravi, A, Şaşmaz, T, Akıcı Kale, D, et al. The prevalence of headache disorders in children and adolescents in Iran: a schools-based study. Cephalalgia. (2022) 42:1246–54. doi: 10.1177/03331024221103814

44. Rahav, G, Lustig, Y, Lavee, J, Benjamini, O, Magen, H, Hod, T, et al. BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccination in immunocompromised patients: a prospective cohort study. EClinicalMedicine. (2021) 41:101158. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101158

45. Göbel, CH, Heinze, A, Karstedt, S, Morscheck, M, Tashiro, L, Cirkel, A, et al. Clinical characteristics of headache after vaccination against COVID-19 (coronavirus SARS-CoV-2) with the BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine: a multicentre observational cohort study. Brain Commun. (2021) 3:169. doi: 10.1093/braincomms/fcab169

46. Hong, C-K, Joo, J-Y, Shim, YS, Sim, SY, Kwon, MA, Kim, YB, et al. The course of headache in patients with moderate-to-severe headache due to mild traumatic brain injury: a retrospective cross-sectional study. J Headache Pain. (2017) 18:48. doi: 10.1186/s10194-017-0755-9

47. Kwong, WJ, and Pathak, DS. Validation of the eleven-point pain scale in the measurement of migraine headache pain. Cephalalgia. (2007) 27:336–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2007.01283.x

48. Caliendo, AM, and Hanson, KE. COVID-19: Diagnosis. UpToDate (2022). Available at: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/covid-19-diagnosis (Accessed May 5, 2022).

49. Nagy, A, and Alhatlani, B. An overview of current COVID-19 vaccine platforms. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. (2021) 19:2508–17. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2021.04.061

50. UpToDate. Pathophysiology and treatment of fever in adults [internet]. UpToDate. (2022). Available at: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/pathophysiology-and-treatment-of-fever-in-adults (Accessed May 05, 2022).

51. ICHD-3. Headache attributed to psychiatric disorder the international classification of headache disorders 3rd edition: The international classification of headache disorders 3rd edition (2023). Available at: https://ichd-3.org/12-headache-attributed-to-psychiatric-disorder/#:~:text=Headache%20disorders%20occur%20coincidentally%20with,social%20anxiety%20disorder%20and%20generalized (Accessed April 10, 2023).

52. Beatty, AL, Peyser, ND, Butcher, XE, Cocohoba, JM, Lin, F, Olgin, JE, et al. Analysis of COVID-19 vaccine type and adverse effects following vaccination. JAMA Netw Open. (2021) 4:364. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.40364

53. Desalegn, M, Garoma, G, Tamrat, H, Desta, A, and Prakash, A. The prevalence of AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine side effects among Nigist Eleni Mohammed memorial comprehensive specialized hospital health workers. Cross sectional survey. Plos One. (2022) 17:e0265140. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0265140

54. Al-Qazaz, HK, Al-Obaidy, LM, and Attash, HM. COVID-19 vaccination, do women suffer from more side effects than men? A retrospective cross-sectional study. Pharm Pract (Granada). (2022) 20:01–10. doi: 10.18549/PharmPract.2022.2.2678

55. Straburzyński, M, Kuca-Warnawin, E, and Waliszewska-Prosół, M. COVID-19-related headache and innate immune response – a narrative review. Neurol Neurochir Pol. (2023) 57:43–52. doi: 10.5603/PJNNS.a2022.0049

56. Amanollahi, M, Jameie, M, Heidari, A, and Rezaei, N. The dialogue between Neuroinflammation and adult neurogenesis: mechanisms involved and alterations in neurological diseases. Mol Neurobiol. (2023) 60:923–59. doi: 10.1007/s12035-022-03102-z

57. Amanollahi, M, Jameie, M, and Rezaei, N. Neuroinflammation as a potential therapeutic target in neuroimmunological diseases In: Translational Neuroimmunology, vol. 7. Amsterdam: Elsevier (2023). 475–504.

58. Nasergivehchi, S, Togha, M, Jafari, E, Sheikhvatan, M, and Shahamati, D. Headache following vaccination against COVID-19 among healthcare workers with a history of COVID-19 infection: a cross-sectional study in Iran with a meta-analytic review of the literature. Head Face Med. (2023) 19:19. doi: 10.1186/s13005-023-00363-4

Keywords: headache, headache disorders, COVID-19 vaccines, COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, vaccination, adverse event, safety

Citation: Jameie M, Togha M, Azizmohammad Looha M, Jafari E, Yazdan Panah M, Hemmati N and Nasergivehchi S (2023) Characteristics of headaches attributed to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination and factors associated with its frequency and prolongation: a cross-sectional cohort study. Front. Neurol. 14:1214501. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2023.1214501

Edited by:

Catherine Stika, Northwestern University, United StatesReviewed by:

Fitalew Tadele, Debre Tabor University, EthiopiaMarta Waliszewska-Prosół, Wroclaw Medical University, Poland

Copyright © 2023 Jameie, Togha, Azizmohammad Looha, Jafari, Yazdan Panah, Hemmati and Nasergivehchi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mansoureh Togha, togha1961@gmail.com

Melika Jameie

Melika Jameie