95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

MINI REVIEW article

Front. Neurol. , 20 April 2023

Sec. Stroke

Volume 14 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2023.1148697

N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors (NMDARs) play a critical role in excitotoxicity caused by ischemic stroke, but NMDAR antagonists have failed to be translated into clinical practice for treating stroke patients. Recent studies suggest that targeting the specific protein–protein interactions that regulate NMDARs may be an effective strategy to reduce excitotoxicity associated with brain ischemia. α2δ-1 (encoded by the Cacna2d1 gene), previously known as a subunit of voltage-gated calcium channels, is a binding protein of gabapentinoids used clinically for treating chronic neuropathic pain and epilepsy. Recent studies indicate that α2δ-1 is an interacting protein of NMDARs and can promote synaptic trafficking and hyperactivity of NMDARs in neuropathic pain conditions. In this review, we highlight the newly identified roles of α2δ-1-mediated NMDAR activity in the gabapentinoid effects and NMDAR excitotoxicity during brain ischemia as well as targeting α2δ-1-bound NMDARs as a potential treatment for ischemic stroke.

Stroke is the second most common cause of death and the leading cause of morbidity and disability worldwide (1). Ischemic stroke accounts for 85% of stroke patients and results from cerebral ischemia and ischemia-reperfusion injury (2). Brain ischemia causes a complex series of pathophysiological events, including oxidative stress, inflammation, apoptosis, ionic imbalance, and excitotoxicity, with glutamate-gated N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR)-mediated excitotoxicity being a key factor (3–5). NMDARs are fundamental to both the physiology and pathology of the mammalian central nervous system (CNS), with dual roles in neuronal survival and death (6, 7). Normal NMDAR activity is essential for many neurological functions, including neuronal plasticity, brain development, and memory (8). Nevertheless, NMDAR over-activation can cause calcium overload, activating the downstream death-signaling pathways, and ultimately leading to irreversible neuronal death, which is called “excitotoxicity” (9–11). Although a number of animal studies have indicated that NMDAR blockers have neuroprotective effects on ischemic brain injury, NMDAR antagonists have proven largely unsuccessful in clinical trials mainly due to inhibiting physiological functions of NMDARs and intolerable side effects (12, 13). Further elucidating the molecular mechanism leading to pathological NMDAR hyperactivity during brain ischemia is essential for developing effective treatments for ischemic stroke. α2δ-1 (encoded by Cacna2d1), commonly known as a subunit of voltage-gated calcium channels (VGCCs), is a newly identified interacting protein of NMDARs in neuropathic pain (14–16). In this review, we briefly discuss recent findings about α2δ-1-bound NMDARs and their roles in excitotoxicity in ischemic stroke and the potential of targeting α2δ-1-bound NMDARs for treating cerebral ischemia.

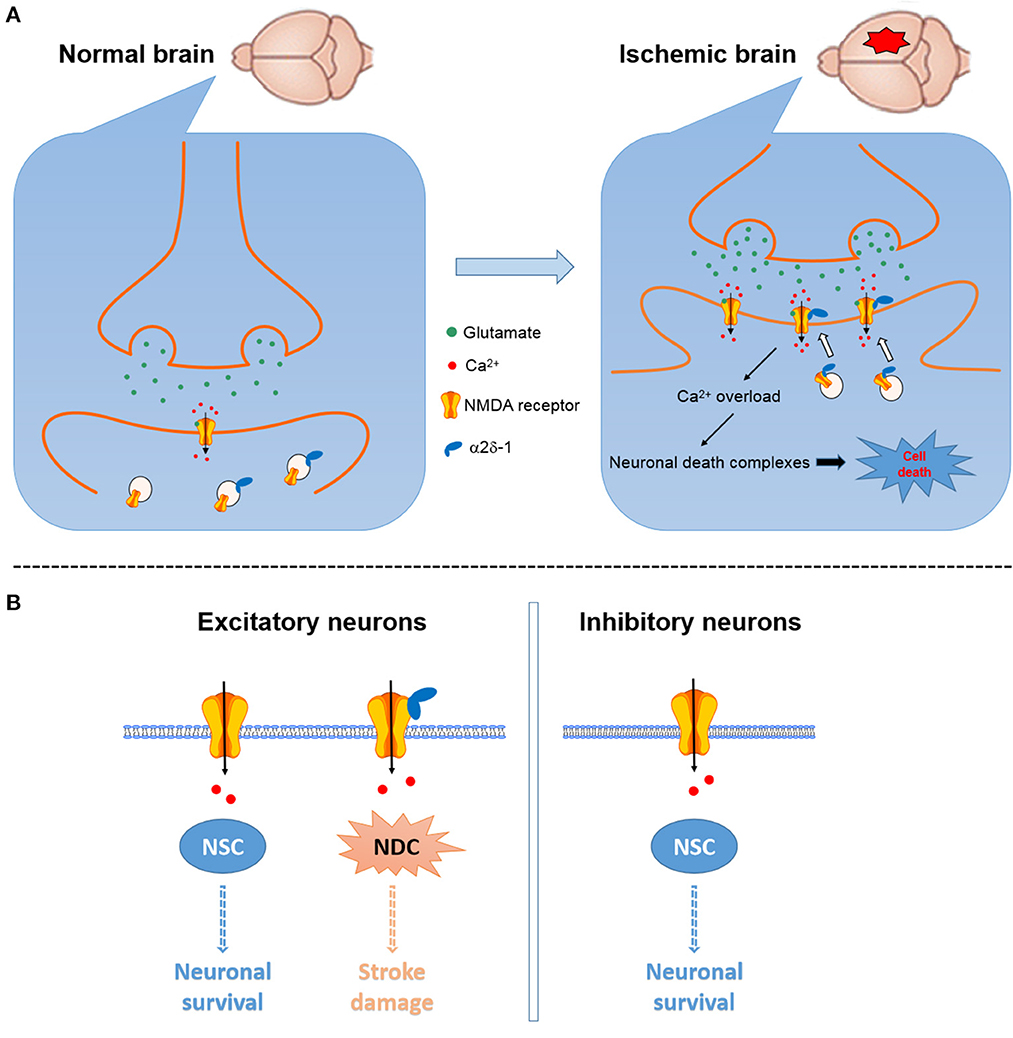

As the main subtype of ionotropic glutamate receptors, NMDARs are heterotetramers formed mostly by two GluN1 subunits and two GluN2 subunits (mainly GluN2A and GluN2B), serving as an important component of the excitatory post-synaptic membrane (17). Some studies suggest that activation of synaptic NMDARs may promote neuronal survival, whereas stimulation of extrasynaptic NMDARs may mediate pro-death effects (11, 18–20). However, this remains a hypothesis, and it is uncertain how the survival and death-signaling proteins are segregated to the subcellular synaptic or extrasynaptic sites (11). In this regard, post-synaptic density-95 (PSD95) is involved in NMDAR-mediated excitotoxic injury in synaptic sites (21). Moreover, it has been hypothesized that GluN2A-containing NMDARs are involved in neuronal survival, whereas GluN2B-containing NMDARs cause neuronal apoptosis and excitotoxicity (22). Contrary to this assumption, GluN2A-containing NMDARs can mediate neuronal death, and GluN2B-containing NMDARs may promote neuronal survival under certain experimental conditions (23). In the adult brain, GluN2A- and GluN2B-containing NMDARs may be preferentially localized at the synaptic and extrasynaptic sites, respectively (8). It is unclear how these NMDARs are differentially involved in the activation of the downstream neuronal survival-signaling complex (NSC) and/or the neuronal death-signaling complex (NDC) (Supplementary Figure 1).

NSC and NDC may be closely associated with the NMDAR channels either through protein–protein interactions or through spatial compartmentalization to synaptic or extrasynaptic sites (13, 24). Targeting protein–protein interactions required for NMDAR-mediated death-signaling pathways may be a promising strategy for effectively treating stroke.

The cytoplasmic C-terminal domains (CTDs) of NMDARs are distinct and contain specific motifs for interactions with a variety of scaffolding proteins, enzymes, and synapse-associated signaling proteins (26, 27). Due to the unique role of CTDs in the downstream intracellular signaling and synaptic retention of NMDARs, the altered binding of proteins with NMDAR subunits has been identified to be closely related to specific downstream signaling pathways and aberrant NMDAR synaptic localization in several disease states, such as cerebral ischemia (28–31).

Protein–protein interactions involving the CTDs of NMDAR subunits in experimental models of cerebral ischemia have been reported (28, 30). The GluN2B/PSD95/neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) complex may play a key role in driving excitotoxic signals in ischemic stroke (21, 32). PSD95 can couple with the CTDs of GluN2B to trigger the pro-death-signaling pathway, and cerebral ischemia may induce the interaction of the downstream nNOS with post-synaptic PSD95 at excitatory synapses, produce a toxic level of NO, and lead to neuronal death (21). Disrupting nNOS-PSD95 interaction via overexpressing the N-terminal amino acid residues 1-133 of nNOS (nNOS-N1 − 133) or a small-molecular inhibitor of nNOS-PSD95 interaction, ZL006, showed potent neuroprotective activity (21). Furthermore, cell-permeable peptides interfering with the PSD95/GluN2B interaction, such as the NA-1, a peptide sequence of the GluN2B CTD (KLSSIESDV), seem to reduce ischemic stroke (33). Moreover, the activation of the GluN2B/CaMKII cascade may increase CaMKII-dependent phosphorylation of acid-sensing ion channels (ASICs) in hippocampal neurons, which can result in an increased intracellular Ca2+ and the subsequent acidotoxic neuronal death (34). In the oxygen-glucose deprivation (OGD) condition, CaMKII inhibition or knockdown can produce a neuroprotective effect (35). Furthermore, death-associated protein kinase 1 (DAPK1) can interact directly with the CTD of GluN2B, which may be a therapeutic target for ischemic stroke (36, 37). Cerebral ischemia may promote the formation of the GluN2B/DAPK1 complex, activate DAPK1-dependent phosphorylation of GluN2B, and enhance the NMDAR channel conductance, leading to neuronal death (36). In a mouse model of experimental stroke, administration of a cell membrane—permeable NR2BCT peptide—can protect neurons against cerebral ischemic insults (36, 38).

Although GluN2B-containing NMDARs, especially the CTD and phosphorylation of GluN2B, have been suggested to play a role in inducing NMDAR-dependent neurotoxicity, the interaction between GluN2A and metabotropic glutamate receptor 1 (mGluR1) C-terminus seems to be also important for excitotoxicity in a rat model of ischemic stroke (30, 39). The disruption of GluN2A/mGluR1 interaction protected neurons against NMDAR-mediated excitotoxicity and reversed NMDAR-mediated regulation of ERK1/2 (39). Both GluN2A and GluN2B subunits may form a complex with transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily M member 4 (TRPM4) at the extrasynaptic site (40).

The VGCCs are fundamental regulators of intracellular calcium homeostasis, which are composed of pore-forming α1, auxiliary β, and α2δ subunits (41, 42). α2δ subunits belong to glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored protein family, which in addition to being the binding site of gabapentinoids α2δ-1 and α2δ-2), were also identified as pain genes in a forward genetic screen (α2δ-3) (43– 46). Among them, α2δ-1 is strongly expressed in many brain regions, including the cerebral cortex and hippocampus, and α2δ-1 is preferentially localized in excitatory neurons (47, 48). However, quantitative proteomic analysis indicates that α2δ-1 has a weak interaction with VGCCs in the brain tissue (49). In addition, α2δ-1 ablation has no effect on the expression pattern of the VGCC α1 subunit or VGCC currents in the brain (50, 51).

Gabapentinoids (i.e., pregabalin, gabapentin, and mirogabalin) are widely used to treat neuropathic pain and epilepsy in clinic (52–54). α2δ-1 and α2δ-2 are the binding target of gabapentinoids (55, 56). Compared with α2δ-2, gabapentinoids have a much higher affinity for α2δ-1 (56). The binding of gabapentinoids to α2δ-1, but not α2δ-2, is mainly responsible for its efficacy in neuropathic pain and epilepsy (15, 45, 47). Furthermore, α2δ-2 seems to be preferentially expressed in inhibitory interneurons, which may be related to the CNS side effects of gabapentinoids. However, gabapentinoids have no evident effect on VGCC activity or VGCC-mediated neurotransmitter release at presynaptic terminals (15, 57–59). Thus, the exact mechanisms underlying gabapentinoid actions are not known until recently.

NMDAR hyperactivity at the spinal cord level plays a central role in the development of chronic pain after nerve injury. Recent studies reveal that α2δ-1 can directly interact with NMDARs, forming a heteromeric complex through its C-terminal domain (15). In contrast, α2δ-1 seems to interact with VGCCs and thrombospondins via the von Willebrand factor type A domain on the N terminus (60). The functional significance of the α2δ-1-NMDAR complex has been demonstrated in various disease conditions, including neuropathic pain caused by traumatic nerve injury, chemotherapy, small-fiber neuropathy, calcineurin inhibitors, genetic and stress-induced hypertension, opioid-induced hyperalgesia and analgesic tolerance, opioid addiction, and ischemic brain injury (16, 25, 61–71) (Supplementary Table 1). Mechanistically, α2δ-1 preferentially binds to phosphorylated NMDARs and promotes surface and synaptic trafficking of NMDARs, and also reduces the Mg2+ block of NMDAR channels to trigger Ca2+ influx (15, 72). In neuropathic pain, the increased synaptic expression of α2δ-1-NMDAR complex is essential for the enhancement of synaptic NMDAR activity, and the synaptic NMDAR hyperactivity can be reversed by interrupting the α2δ-1-NMDAR interaction (15, 16, 64). The importance of the α2δ-1 C-terminus in the induction of neuropathic pain has been shown using α2δ-1 chimera in which the C-terminus is mutated (73).

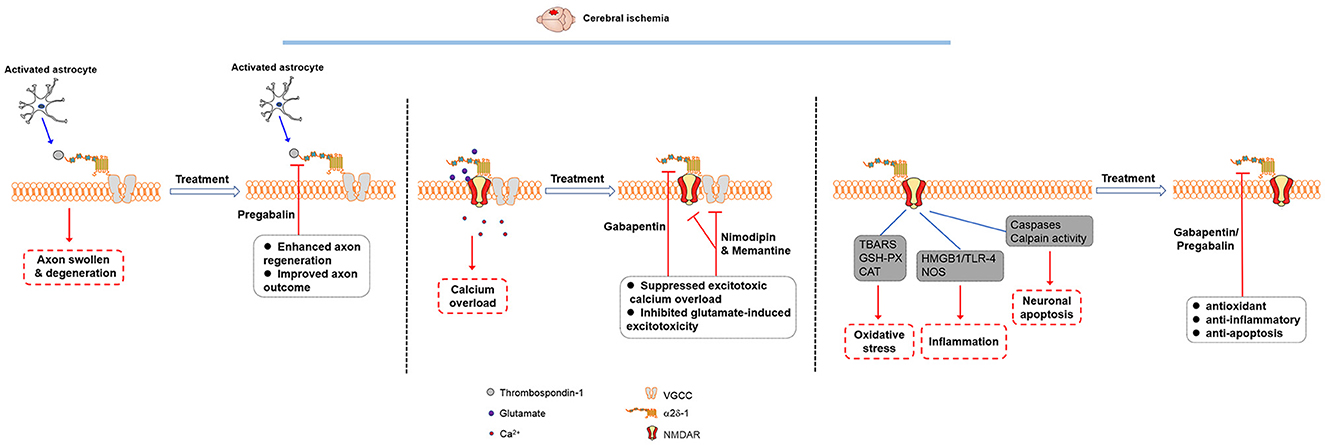

Gabapentin was initially developed as an anticonvulsant, but it is also used to treat neuropathic pain. Gabapentin has been shown to reduce acute ischemic seizures, post-stroke pain, and spreading depression in brain injury (74–76). In an animal model of ischemic injury in the immature brain, gabapentin significantly decreases the severity of brain atrophy and acute seizures (74). The neuroprotective effects of gabapentinoids in ischemic stroke have been shown in various animal models (Supplementary Table 2). In a mouse model of transient focal ischemia, gabapentin pretreatment reduces the infarct volume by 23% independent of peri-infarct depolarization suppression (75). In patients with thalamic pain syndrome, gabapentin reduces the pain severity and the thalamus impairment (76). In the in vitro oxygen-glucose deprivation (OGD) model, gabapentin has a protective effect against neuronal injury (77). Systemic treatment of gabapentin reduces middle cerebral artery occlusion-induced infarct volumes, neurological deficit scores, and apoptosis (25). Furthermore, the neuroprotective effects of pregabalin on cerebral ischemia have been reported in a rodent stroke model, including the suppression of calcium-mediated proteolysis and the damage of oxidative stress, the attenuation of inflammation, and improving axon regeneration and motor outcome (78–81). Gabapentin and pregabalin have been extensively used in patients with chronic pain and anxiety disorders, exhibiting an excellent safety profile (82, 83). Thus, gabapentinoids could be repurposed for treating ischemic stroke in future.

It has been reported that α2δ-1 may bind to thrombospondin, an astrocyte-secreted protein, to promote synaptogenesis (84). Gabapentin may reduce α2δ-1 interaction with thrombospondin and inhibit the new synapse formation (85). Pregabalin treatment induces axon sprouting and functional recovery in a mouse model of cortical stroke (81). However, astrocyte-derived thrombospondin-1 is upregulated in the astroglial peri-infarct scar but not elevated in remote cortical projection areas (81). This interaction may not account for the relatively rapid onset of gabapentinoid effects on acute cerebral ischemia. Another study suggested that the association between thrombospondin and α2δ-1 is rather weak, and no obvious α2δ-1-thrombospondin interaction can be detected on the cell surface (86).

During cerebral ischemia, excessive release of glutamate from presynaptic terminals can result in sustained Ca2+ influx through post-synaptic NMDARs and VGCCs. The neuroprotection by pregabalin was suggested to be associated with targeting VGCCs (78). The levels of α2δ-1 subunit can be detected in serum specimens, and the serum levels of α2δ-1 are significantly higher in ischemic stroke patients (87). Nevertheless, as mentioned above, gabapentinoids have no effect on VGCC activity in vitro and in neural tissues. Moreover, nimodipine, a widely used VGCC antagonist, has no efficacy in stroke patients as L-type Ca2+ channels are mainly distributed in cell bodies and proximal dendrites of neurons (88, 89).

Inhibiting α2δ-1 with gabapentin has a profound inhibitory effect on oxygen-glucose deprivation-induced NMDAR hyperactivity in hippocampal CA1 neurons (25). In a heterologous expression system, gabapentin inhibits NMDAR activity only when α2δ-1 is coexpressed (15). Thus, the action of α2δ-1 in vivo is predominantly related to its association with NMDARs, which account for the protective actions of gabapentinoids in ischemic stroke (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Molecular mechanisms involved in the therapeutic effects of gabapentinoids in cerebral ischemia. The thrombospondin-α2δ-1 interaction may play a role in synaptogenesis, but it is unlikely involved in the gabapentinoid effects on acute cerebral ischemia. Gabapentinoids likely act on α2δ-1-bound NMDARs to reduce excitotoxic Ca2+ overload and glutamate-induced excitotoxicity as well as produce antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-apoptosis effects in cerebral ischemia.

α2δ-1 can readily form a heteromeric protein complex with phosphorylated NMDARs mainly through its C-terminus domain (15, 72). In the striatum, α2δ-1-bound NMDARs account for ~44% NMDARs present on the plasma membrane (90). In Cacna2d1 knockout mice, transient cerebral ischemia does not increase the basal NMDAR currents, suggesting that the α2δ-1 may be essential for ischemia-induced neuronal NMDAR hyperactivity in the brain tissue (25). Accordingly, ischemia can increase the α2δ-1-NMDAR association, and α2δ-1-bound NMDARs mediate brain damage caused by cerebral ischemia or intracerebral hemorrhage (25, 69). Because α2δ-1 is preferentially expressed in excitatory neurons (47), α2δ-1-bound NMDARs may be the critical component for the NMDAR-mediated excitotoxicity (Figure 2). Targeting the α2δ-1-bound NMDARs using specific α2δ-1 C-terminus peptides or inhibitors would not interfere with the physiological, α2δ-1-free NMDAR function. Thus, α2δ-1-bound NMDARs could be targeted for the development of new neuroprotective drugs for treating and preventing ischemic stroke, including patients undergoing major neurological and cardiac surgeries.

Figure 2. Schematic showing the potential role of α2δ-1 in NMDAR-mediated excitotoxicity in cerebral ischemia and reperfusion. (A) Cerebral ischemia can increase α2δ-1 expression and α2δ-1-NMDAR interactions to promote the synaptic trafficking of α2δ-1-bound NMDARs, resulting in NMDAR hyperactivity, calcium overload, and downstream cell death-signaling pathways and eventually neuronal death and brain damage [modified from Luo et al. (25)]. (B) α2δ-1-free NMDARs present in excitatory and inhibitory neurons likely mainly mediate the physiological functions of NMDARs via the neuronal survival-signaling complex (NSC), whereas α2δ-1-bound NMDARs expressed in excitatory neurons may predominantly activate the neuronal death-signaling complex (NDC).

In summary, recent findings about α2δ-1-bound NMDARs have greatly advanced our understanding of the molecular mechanism of excitotoxicity associated with ischemic stroke. Compared with traditional non-selective NMDAR antagonists, treatment with α2δ-1 competing peptides or inhibitors (e.g., gabapentinoids) may represent an effective therapy for ischemic stroke. The subunit composition, synaptic localization, and numbers of NMDARs are not static but are dynamically regulated in response to neuronal activities (11). Further clinical research is needed to determine whether α2δ-1-bound NMDARs are a valid target for treating ischemic stroke.

YL and H-LP contributed to the conception and design of the study. TW and YL wrote the first draft of the manuscript and performed the literature search. H-LP and S-RC critically revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The study in authors' laboratories was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82071324) and the National Institutes of Health (No. NS101880).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2023.1148697/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Figure 1. Potential dual roles of NMDARs in neuronal survival and death. (A) NMDARs present at synaptic and extrasynaptic sites, which may be differentially involved in neuronal survival and death. (B) GluN2A- and GluN2B-containing NMDARs may have a different role in neuronal survival and death-signaling via the activation of downstream neuronal survival-signaling complex (NSC) and the activation of neuronal death-signaling complex (NDC).

Supplementary Table 1. The potential roles of α2δ-1-NMDAR complexes in various disease conditions.

Supplementary Table 2. Therapeutic effects of gabapentinoids in ischemic brain injury.

1. Khoshnam SE, Winlow W, Farzaneh M, Farbood Y, Moghaddam HF. Pathogenic mechanisms following ischemic stroke. Neurol Sci. (2017) 38:1167–86. doi: 10.1007/s10072-017-2938-1

2. Beal CC. Gender and stroke symptoms: a review of the current literature. J Neurosci Nurs. (2010) 42:80–7. doi: 10.1097/JNN.0b013e3181ce5c70

3. Doyle KP, Simon RP, Stenzel-Poore MP. Mechanisms of ischemic brain damage. Neuropharmacology. (2008) 55:310–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.01.005

4. Besancon E, Guo S, Lok J, Tymianski M, Lo EH. Beyond NMDA and AMPA glutamate receptors: emerging mechanisms for ionic imbalance and cell death in stroke. Trends Pharmacol Sci. (2008) 29:268–75. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2008.02.003

5. Lai TW, Zhang S, Wang YT. Excitotoxicity and stroke: identifying novel targets for neuroprotection. Prog Neurobiol. (2014) 115:157–88. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.11.006

6. Paoletti P, Bellone C, Zhou Q. NMDA receptor subunit diversity: impact on receptor properties, synaptic plasticity and disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. (2013) 14:383–400. doi: 10.1038/nrn3504

7. Ogden KK, Traynelis SF. New advances in NMDA receptor pharmacology. Trends Pharmacol Sci. (2011) 32:726–33. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2011.08.003

8. Traynelis SF, Wollmuth LP, McBain CJ, Menniti FS, Vance KM, Ogden KK, et al. Glutamate receptor ion channels: structure, regulation, and function. Pharmacol Rev. (2010) 62:405–96. doi: 10.1124/pr.109.002451

9. Szydlowska K, Tymianski M. Calcium, ischemia and excitotoxicity. Cell Calcium. (2010) 47:122–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2010.01.003

10. Chamorro A, Dirnagl U, Urra X, Planas AM. Neuroprotection in acute stroke: targeting excitotoxicity, oxidative and nitrosative stress, and inflammation. Lancet Neurol. (2016) 15:869–81. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(16)00114-9

11. Wu QJ, Tymianski M. Targeting NMDA receptors in stroke: new hope in neuroprotection. Mol Brain. (2018) 11:15. doi: 10.1186/s13041-018-0357-8

12. Lipton SA. NMDA receptors, glial cells, and clinical medicine. Neuron. (2006) 50:9–11. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.03.026

13. Lai TW, Shyu WC, Wang YT. Stroke intervention pathways: NMDA receptors and beyond. Trends Mol Med. (2011) 17:266–75. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2010.12.008

14. Dolphin AC. Calcium channel auxiliary alpha2delta and beta subunits: trafficking and one step beyond. Nat Rev Neurosci. (2012) 13:542–55. doi: 10.1038/nrn3311

15. Chen J, Li L, Chen SR, Chen H, Xie JD, Sirrieh RE, et al. The alpha2delta-1-NMDA receptor complex is critically involved in neuropathic pain development and gabapentin therapeutic actions. Cell Rep. (2022) 38:110308. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2022.110308

16. Chen Y, Chen SR, Chen H, Zhang J, Pan HL. Increased alpha2delta-1-NMDA receptor coupling potentiates glutamatergic input to spinal dorsal horn neurons in chemotherapy-induced neuropathic pain. J Neurochem. (2019) 148:252–74. doi: 10.1111/jnc.14627

17. Kohr G. NMDA receptor function: subunit composition versus spatial distribution. Cell Tissue Res. (2006) 326:439–46. doi: 10.1007/s00441-006-0273-6

18. Lu W, Man H, Ju W, Trimble WS, MacDonald JF, Wang YT. Activation of synaptic NMDA receptors induces membrane insertion of new AMPA receptors and LTP in cultured hippocampal neurons. Neuron. (2001) 29:243–54. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(01)00194-5

19. Hardingham GE, Fukunaga Y, Bading H. Extrasynaptic NMDARs oppose synaptic NMDARs by triggering CREB shut-off and cell death pathways. Nat Neurosci. (2002) 5:405–14. doi: 10.1038/nn835

20. Okamoto S, Pouladi MA, Talantova M, Yao D, Xia P, Ehrnhoefer DE, et al. Balance between synaptic versus extrasynaptic NMDA receptor activity influences inclusions and neurotoxicity of mutant huntingtin. Nat Med. (2009) 15:1407–13. doi: 10.1038/nm.2056

21. Zhou L, Li F, Xu HB, Luo CX, Wu HY, Zhu MM, et al. Treatment of cerebral ischemia by disrupting ischemia-induced interaction of nNOS with PSD-95. Nat Med. (2010) 16:1439–43. doi: 10.1038/nm.2245

22. Liu YT, Wong TP, Aarts M, Rooyakkers A, Liu LD, Lai TW, et al. NMDA receptor subunits have differential roles in mediating excitotoxic neuronal death both in vitro and in vivo. J Neurosci. (2007) 27:2846–57. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0116-07.2007

23. von Engelhardt J, Coserea I, Pawlak V, Fuchs EC, Kohr G, Seeburg PH, et al. Excitotoxicity in vitro by NR2A- and NR2B-containing NMDA receptors. Neuropharmacology. (2007) 53:10–7. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.04.015

24. Lai TW, Wang YT. Fashioning drugs for stroke. Nat Med. (2010) 16:1376–8. doi: 10.1038/nm1210-1376

25. Luo Y, Ma H, Zhou JJ, Li L, Chen SR, Zhang J, et al. Focal cerebral ischemia and reperfusion induce brain injury through alpha2delta-1-bound NMDA receptors. Stroke. (2018) 49:2464–72. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.118.022330

26. Sanz-Clemente A, Gray JA, Ogilvie KA, Nicoll RA, Roche KW. Activated CaMKII couples GluN2B and casein kinase 2 to control synaptic NMDA receptors. Cell Rep. (2013) 3:607–14. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.02.011

27. Sun Y, Cheng X, Zhang L, Hu J, Chen Y, Zhan L, Gao Z. The functional and molecular properties, physiological functions, and pathophysiological roles of GluN2A in the central nervous system. Mol Neurobiol. (2017) 54:1008–1021. doi: 10.1007/s12035-016-9715-7

28. Gardoni F, Di Luca M. Protein-protein interactions at the NMDA receptor complex: From synaptic retention to synaptonuclear protein messengers. Neuropharmacology. (2021) 190:108551. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2021.108551

29. Weilinger NL, Lohman AW, Rakai BD, Ma EM, Bialecki J, Maslieieva V, et al. Metabotropic NMDA receptor signaling couples Src family kinases to pannexin-1 during excitotoxicity. Nat Neurosci. (2016) 19:432–42. doi: 10.1038/nn.4236

30. Martel MA, Ryan TJ, Bell KF, Fowler JH, McMahon A, Al-Mubarak B, et al. The subtype of GluN2 C-terminal domain determines the response to excitotoxic insults. Neuron. (2012) 74:543–56. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.03.021

31. Buonarati OR, Cook SG, Goodell DJ, Chalmers NE, Rumian NL, Tullis JE, et al. CaMKII versus DAPK1 binding to GluN2B in ischemic neuronal cell death after resuscitation from cardiac arrest. Cell Rep. (2020) 30:1–8.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.11.076

32. Aarts M, Liu Y, Liu L, Besshoh S, Arundine M, Gurd JW, et al. Treatment of ischemic brain damage by perturbing NMDA receptor- PSD-95 protein interactions. Science. (2002) 298:846–50. doi: 10.1126/science.1072873

33. Ballarin B, Tymianski M. Discovery and development of NA-1 for the treatment of acute ischemic stroke. Acta Pharmacol Sin. (2018) 39:661–8. doi: 10.1038/aps.2018.5

34. Gao J, Duan B, Wang DG, Deng XH, Zhang GY, Xu L, et al. Coupling between NMDA receptor and acid-sensing ion channel contributes to ischemic neuronal death. Neuron. (2005) 48:635–46. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.10.011

35. Vieira MM, Schmidt J, Ferreira JS, She K, Oku S, Mele M, et al. Multiple domains in the C-terminus of NMDA receptor GluN2B subunit contribute to neuronal death following in vitro ischemia. Neurobiol Dis. (2016) 89:223–34. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2015.11.007

36. Tu W, Xu X, Peng L, Zhong X, Zhang W, Soundarapandian MM, et al. DAPK1 interaction with NMDA receptor NR2B subunits mediates brain damage in stroke. Cell. (2010) 140:222–34. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.055

37. Wang S, Shi X, Li H, Pang P, Pei L, Shen H, et al. DAPK1 signaling pathways in stroke: from mechanisms to therapies. Mol Neurobiol. (2017) 54:4716–22. doi: 10.1007/s12035-016-0008-y

38. Tu G, Fu TT, Yang FY, Yao LX, Xue WW, Zhu F. Prediction of GluN2B-CT1290–1310/DAPK1 interaction by protein-peptide docking and molecular dynamics simulation. Molecules. (2018) 23:3018. doi: 10.3390/molecules23113018

39. Lai TKY, Zhai DX, Su P, Jiang AL, Boychuk J, Liu F. The receptor-receptor interaction between mGluR1 receptor and NMDA receptor: a potential therapeutic target for protection against ischemic stroke. Faseb J. (2019) 33:14423–39. doi: 10.1096/fj.201900417R

40. Yan J, Bengtson CP, Buchthal B, Hagenston AM, Bading H. Coupling of NMDA receptors and TRPM4 guides discovery of unconventional neuroprotectants. Science. (2020) 370:eaay3302. doi: 10.1126/science.aay3302

41. Catterall WA. Structure and regulation of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. (2000) 16:521–55. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.16.1.521

42. Hoppa MB, Lana B, Margas W, Dolphin AC, Ryan TA. alpha2delta expression sets presynaptic calcium channel abundance and release probability. Nature. (2012) 486:122–5. doi: 10.1038/nature11033

43. Davies A, Kadurin I, Alvarez-Laviada A, Douglas L, Nieto-Rostro M, Bauer CS, et al. The alpha2delta subunits of voltage-gated calcium channels form GPI-anchored proteins, a posttranslational modification essential for function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2010) 107:1654–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908735107

44. Wang M, Offord J, Oxender DL, Su TZ. Structural requirement of the calcium-channel subunit alpha2delta for gabapentin binding. Biochem J. (1999) 342(Pt 2):313–20. doi: 10.1042/bj3420313

45. Field MJ, Cox PJ, Stott E, Melrose H, Offord J, Su TZ, et al. Identification of the alpha(2)-delta-1 subunit of voltage-dependent calcium channels as a molecular target for pain mediating the analgesic actions of pregabalin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2006) 103:17537–42. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409066103

46. Neely GG, Hess A, Costigan M, Keene AC, Goulas S, Langeslag M, et al. A Genome-wide drosophila screen for heat nociception identifies alpha 2 delta 3 as an evolutionarily conserved pain gene. Cell. (2010) 143:628–38. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.09.047

47. Cole RL, Lechner SM, Williams ME, Prodanovich P, Bleicher L, Varney MA, et al. Differential distribution of voltage-gated calcium channel alpha-2 delta (alpha2delta) subunit mRNA-containing cells in the rat central nervous system and the dorsal root ganglia. J Comp Neurol. (2005) 491:246–69. doi: 10.1002/cne.20693

48. Taylor CP, Garrido R. Immunostaining of rat brain, spinal cord, sensory neurons and skeletal muscle for calcium channel alpha(2)-delta (alpha(2)-delta) type 1 protein. Neuroscience. (2008) 155:510–21. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.05.053

49. Muller CS, Haupt A, Bildl W, Schindler J, Knaus HG, Meissner M, et al. Quantitative proteomics of the Cav2 channel nano-environments in the mammalian brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2010) 107:14950–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005940107

50. Felsted JA, Chien CH, Wang DQ, Panessiti M, Ameroso D, Greenberg A, et al. Alpha2delta-1 in SF1(+) neurons of the ventromedial hypothalamus is an essential regulator of glucose and lipid homeostasis. Cell Rep. (2017) 21:2737–47. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.11.048

51. Held RG, Liu C, Ma K, Ramsey AM, Tarr TB, De Nola G, et al. Synapse and active zone assembly in the absence of presynaptic Ca(2+) channels and Ca(2+) entry. Neuron. (2020) 107:667–83.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2020.05.032

52. Dworkin RH, O'Connor AB, Audette J, Baron R, Gourlay GK, Haanpaa ML, et al. Recommendations for the pharmacological management of neuropathic pain: an overview and literature update. Mayo Clin Proc. (2010) 85:S3–14. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2009.0649

53. Toth C. Pregabalin: latest safety evidence and clinical implications for the management of neuropathic pain. Ther Adv Drug Saf. (2014) 5:38–56. doi: 10.1177/2042098613505614

54. Calandre EP, Rico-Villademoros F, Slim M. Alpha(2)delta ligands, gabapentin, pregabalin and mirogabalin: a review of their clinical pharmacology and therapeutic use. Expert Rev Neurother. (2016) 16:1263–77. doi: 10.1080/14737175.2016.1202764

55. Gong HC, Hang J, Kohler W, Li L, Su TZ. Tissue-specific expression and gabapentin-binding properties of calcium channel alpha2delta subunit subtypes. J Membr Biol. (2001) 184:35–43. doi: 10.1007/s00232-001-0072-7

56. Marais E, Klugbauer N, Hofmann F. Calcium channel alpha(2)delta subunits-structure and Gabapentin binding. Mol Pharmacol. (2001) 59:1243–8. doi: 10.1124/mol.59.5.1243

57. Rock DM, Kelly KM, Macdonald RL. Gabapentin actions on ligand- and voltage-gated responses in cultured rodent neurons. Epilepsy Res. (1993) 16:89–98. doi: 10.1016/0920-1211(93)90023-Z

58. Schumacher TB, Beck H, Steinhauser C, Schramm J, Elger CE. Effects of phenytoin, carbamazepine, and gabapentin on calcium channels in hippocampal granule cells from patients with temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia. (1998) 39:355–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1998.tb01387.x

59. Brown JT, Randall A. Gabapentin fails to alter P/Q-type Ca2+ channel-mediated synaptic transmission in the hippocampus in vitro. Synapse. (2005) 55:262–9. doi: 10.1002/syn.20115

60. Taylor CP, Harris EW. Analgesia with gabapentin and pregabalin may involve N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors, neurexins, and thrombospondins. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. (2020) 374:161–74. doi: 10.1124/jpet.120.266056

61. Ma H, Chen SR, Chen H, Zhou JJ, Li DP, Pan HL. alpha2delta-1 couples to NMDA receptors in the hypothalamus to sustain sympathetic vasomotor activity in hypertension. J Physiol. (2018) 596:4269–83. doi: 10.1113/JP276394

62. Zhou JJ, Shao JY, Chen SR, Li DP, Pan HL. Alpha2delta-1-dependent NMDA receptor activity in the hypothalamus is an effector of genetic-environment interactions that drive persistent hypertension. J Neurosci. (2021) 41:6551–63. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0346-21.2021

63. Huang Y, Chen SR, Chen H, Zhou JJ, Jin D, Pan HL. Theta-burst stimulation of primary afferents drives long-term potentiation in the spinal cord and persistent pain via alpha2delta-1-bound NMDA receptors. J Neurosci. (2022) 42:513–27. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1968-21.2021

64. Zhang J, Chen SR, Zhou MH, Jin D, Chen H, Wang L, et al. HDAC2 in primary sensory neurons constitutively restrains chronic pain by repressing alpha2delta-1 expression and associated NMDA receptor activity. J Neurosci. (2022) 42:8918–35. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0735-22.2022

65. Deng M, Chen SR, Chen H, Pan HL. Alpha2delta-1-bound N-Methyl-D-aspartate receptors mediate morphine-induced hyperalgesia and analgesic tolerance by potentiating glutamatergic input in rodents. Anesthesiology. (2019) 130:804–19. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000002648

66. Chen SR, Chen H, Jin D, Pan HL. Brief opioid exposure paradoxically augments primary afferent input to spinal excitatory neurons via alpha2delta-1-dependent presynaptic NMDA receptors. J Neurosci. (2022) 42:9315–29. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1704-22.2022

67. Huang Y, Chen SR, Chen H, Luo Y, Pan HL. Calcineurin inhibition causes alpha2delta-1-mediated tonic activation of synaptic NMDA receptors and pain hypersensitivity. J Neurosci. (2020) 40:3707–19. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0282-20.2020

68. Fu M, Liu F, Zhang YY, Lin J, Huang CL, Li YL, et al. The alpha2delta-1-NMDAR1 interaction in the trigeminal ganglion contributes to orofacial ectopic pain following inferior alveolar nerve injury. Brain Res Bull. (2021) 171:162–71. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2021.03.019

69. Li J, Song G, Jin Q, Liu L, Yang L, Wang Y, et al. The alpha2delta-1/NMDA receptor complex is involved in brain injury after intracerebral hemorrhage in mice. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. (2021) 8:1366–75. doi: 10.1002/acn3.51372

70. Zhang GF, Chen SR, Jin D, Huang Y, Chen H, Pan HL. Alpha2delta-1 upregulation in primary sensory neurons promotes NMDA receptor-mediated glutamatergic input in resiniferatoxin-induced neuropathy. J Neurosci. (2021) 41:5963–78. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0303-21.2021

71. Jin D, Chen H, Chen SR, Pan HL. Alpha2delta-1 protein drives opioid-induced conditioned reward and synaptic NMDA receptor hyperactivity in the nucleus accumbens. J Neurochem. (2023) 164:143–157. doi: 10.1111/jnc.15706

72. Zhou MH, Chen SR, Wang L, Huang Y, Deng M, Zhang J, et al. Protein kinase C-mediated phosphorylation and alpha2delta-1 interdependently regulate NMDA receptor trafficking and activity. J Neurosci. (2021) 41:6415–29. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0757-21.2021

73. Li L, Chen SR, Zhou MH, Wang L, Li DP, Chen H, et al. alpha2delta-1 switches the phenotype of synaptic AMPA receptors by physically disrupting heteromeric subunit assembly. Cell Rep. (2021) 36:109396. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109396

74. Traa BS, Mulholland JD, Kadam SD, Johnston MV, Comi AM. Gabapentin neuroprotection and seizure suppression in immature mouse brain ischemia. Pediatr Res. (2008) 64:81–5. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e318174e70e

75. Hoffmann U Lee JH Qin T Eikermann-Haerter K and Ayata C. Gabapentin reduces infarct volume but does not suppress peri-infarct depolarizations. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. (2011) 31:1578–82. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2011.50

76. Hesami O, Gharagozli K, Beladimoghadam N, Assarzadegan F, Mansouri B, Sistanizad M. The efficacy of gabapentin in patients with central post-stroke pain. Iran J Pharm Res. (2015) 14:95–101.

77. Kim YS, Chang HK, Lee JW, Sung YH, Kim SE, Shin MS, et al. Protective effect of gabapentin on N-methyl-D-aspartate-induced excitotoxicity in rat hippocampal CA1 neurons. J Pharmacol Sci. (2009) 109:144–7. doi: 10.1254/jphs.08067SC

78. Yoon JS, Lee JH, Son TG, Mughal MR, Greig NH, Mattson MP. Pregabalin suppresses calcium-mediated proteolysis and improves stroke outcome. Neurobiol Dis. (2011) 41:624–9. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.11.011

79. Asci S, Demirci S, Asci H, Doguc DK, Onaran I. Neuroprotective effects of pregabalin on cerebral ischemia and reperfusion. Balkan Med J. (2016) 33:221–7. doi: 10.5152/balkanmedj.2015.15742

80. Song Y, Jun JH, Shin EJ, Kwak YL, Shin JS, Shim JK. Effect of pregabalin administration upon reperfusion in a rat model of hyperglycemic stroke: mechanistic insights associated with high-mobility group box 1. PLoS ONE. (2017) 12. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0171147

81. Kugler C, Blank N, Matuskova H, Thielscher C, Reichenbach N, Lin TC, et al. Pregabalin improves axon regeneration and motor outcome in a rodent stroke model. Brain Commun. (2022) 4:fcac170. doi: 10.1093/braincomms/fcac170

82. Shneker BF, McAuley JW. Pregabalin: a new neuromodulator with broad therapeutic indications. Ann Pharmacother. (2005) 39:2029–37. doi: 10.1345/aph.1G078

83. Patel AS, Abrecht CR, Urman RD. Gabapentinoid use in perioperative care and current controversies. Curr Pain Headache R. (2022) 26:139–144. doi: 10.1007/s11916-022-01012-2

84. Risher WC, Eroglu C. Thrombospondins as key regulators of synaptogenesis in the central nervous system. Matrix Biol. (2012) 31:170–7. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2012.01.004

85. Eroglu C, Allen NJ, Susman MW, O'Rourke NA, Park CY, Ozkan E, et al. Gabapentin receptor alpha 2 delta-1 is a neuronal thrombospondin receptor responsible for excitatory CNS synaptogenesis. Cell. (2009) 139:380–92. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.09.025

86. Lana B, Page KM, Kadurin I, Ho S, Nieto-Rostro M, Dolphin AC. Thrombospondin-4 reduces binding affinity of [(3)H]-gabapentin to calcium-channel alpha2delta-1-subunit but does not interact with alpha2delta-1 on the cell-surface when co-expressed. Sci Rep. (2016) 6:24531. doi: 10.1038/srep24531

87. Xiong X, Zhang L, Li Y, Guo S, Chen W, Huang L, et al. Calcium channel subunit alpha2delta-1 as a potential biomarker reflecting illness severity and neuroinflammation in patients with acute ischemic stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. (2021) 30:105874. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2021.105874

88. Tomassoni D, Lanari A, Silvestrelli G, Traini E, Amenta F. Nimodipine and its use in cerebrovascular disease: evidence from recent preclinical and controlled clinical studies. Clin Exp Hypertens. (2008) 30:744–66. doi: 10.1080/10641960802580232

89. Mize RR, Graham SK, Cork RJ. Expression of the L-type calcium channel in the developing mouse visual system by use of immunocytochemistry. Dev Brain Res. (2002) 136:185–95. doi: 10.1016/S0165-3806(02)00350-4

Keywords: NMDA receptors, excitotoxicity, ischemic stroke, α2δ-1, gabapentin, pregabalin

Citation: Wu T, Chen S-R, Pan H-L and Luo Y (2023) The α2δ-1-NMDA receptor complex and its potential as a therapeutic target for ischemic stroke. Front. Neurol. 14:1148697. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2023.1148697

Received: 20 January 2023; Accepted: 30 March 2023;

Published: 20 April 2023.

Edited by:

Heike Wulff, University of California, Davis, United StatesReviewed by:

Shujia Zhu, Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), ChinaCopyright © 2023 Wu, Chen, Pan and Luo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yi Luo, bHVveWk5MjlAYWxpeXVuLmNvbQ==; Hui-Lin Pan, aHVpbGlucGFuQG1kYW5kZXJzb24ub3Jn

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.