- 1Department of Pharmacy, The Third Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Changsha, Hunan, China

- 2Department of Endocrinology, The Third Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Changsha, Hunan, China

Objective: To investigate the clinical features, treatment, and prognosis of fingolimod-associated macular edema (FAME) and to provide a reference for its rational management.

Methods: FAME-related case reports were included in a pooled analysis by searching Chinese and English databases from 2010 to November 31, 2021.

Results: The median age of 41 patients was 50 years (range, 21, 67 years), of whom 32 were women. The median time to onset of FAME was 3 m (range.03, 120), and blurred vision (17 cases) and decreased vision (13 cases) were the most common complaints. A total of 55 eyes were involved in FAME, including the left eye (14 cases), right eye (10 cases), and both eyes (15 cases), of which 46 eyes had best-corrected visual acuity close to normal (20/12-20/60) and 8 eyes had moderate to severe visual impairment (20/80-20/500). Fundus examination in 23 patients showed macular edema (11 cases). Optical coherence tomography (OCT) in 39 patients mainly showed perifoveal cysts (24 cases), ME (23 cases), and foveal thickening (19 cases). Fundus fluorescein angiography (FFA) in 18 patients showed vascular leakage (11 cases). Complete resolution of ME occurred in 50 eyes and recovery of visual acuity occurred in 45 eyes at a median time of 2 m (range 0.25, 24) after discontinuation of fingolimod or administration of topical therapy.

Conclusions: Macular edema is a known complication of fingolimod. All patients using fingolimod require regular eye exams, especially those with a history of diabetes and uveitis and those undergoing cataract surgery.

Introduction

Fingolimod has been approved for the treatment of multiple sclerosis (MS) and relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS) since 2010 (1). Active metabolites of fingolimod bind to the sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) receptor on lymphocytes, resulting in internalization and degradation of the receptor. This action prevents the egression of lymphocytes from lymphoid tissue into the circulation, thereby, sparing the central nervous system from attack by myelin-reactive lymphocytes (2).

The most common adverse events reported with fingolimod are nasopharyngitis, bradycardia, influenza, and headache. Macular edema (ME) is a rare complication of fingolimod. Two-phase 3 clinical trial studies have shown that fingolimod is associated with the development of ME (3, 4). Randomized controlled trials have demonstrated that macular edema is related to fingolimod. The current understanding of fingolimod-related macular edema is based primarily on case reports. However, the severity, visual symptoms, visual acuity, treatment, and prognosis of fingolimod-associated macular edema (FAME) remain unclear, especially in patients who wish to continue treatment with fingolimod. The purpose of this study was to explore the clinical features of FAME and provide evidence for its prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis by pooling and analyzing relevant case reports.

Methods

Search Strategy

The related literature on fingolimod-associated macular edema was searched in Chinese and English databases from 2010 to December 31, 2021, including the Wanfang database, China Knowledge Network, VIP database, Web of Science, SpringerLink, PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, and OVID. Retrieval was performed using a combination of subject words and free words, such as fingolimod, macular edema, vision loss, blurred vision, and retina.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria: case reports or case series of FAME were included. Exclusion criteria: reviews, mechanistic studies, randomized controlled trials, animal studies, and duplicate literature were excluded.

Data Extraction

Two authors independently screened the literature according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and then, the group selected the literature to be included in the analysis. A self-designed data extraction table was used to extract the following information about the patients: nationality, sex, age, history of ophthalmic disease, the purpose of the medication, application of fingolimod, clinical manifestations, ophthalmic-related examinations, treatment, and prognosis.

The Snellen visual acuity classification was used: near normal vision (20/12–20/60), low vision (20/80–20/1,000), and near blindness (≤ 20/1,000). The low vision category was further divided into moderate visual impairment (20/80–20/160), severe visual impairment (20/200–20/400), and profound visual impairment (20/500–20/1,000) (5).

Descriptive statistical analysis was performed on the extracted data.

Results

Basic Information

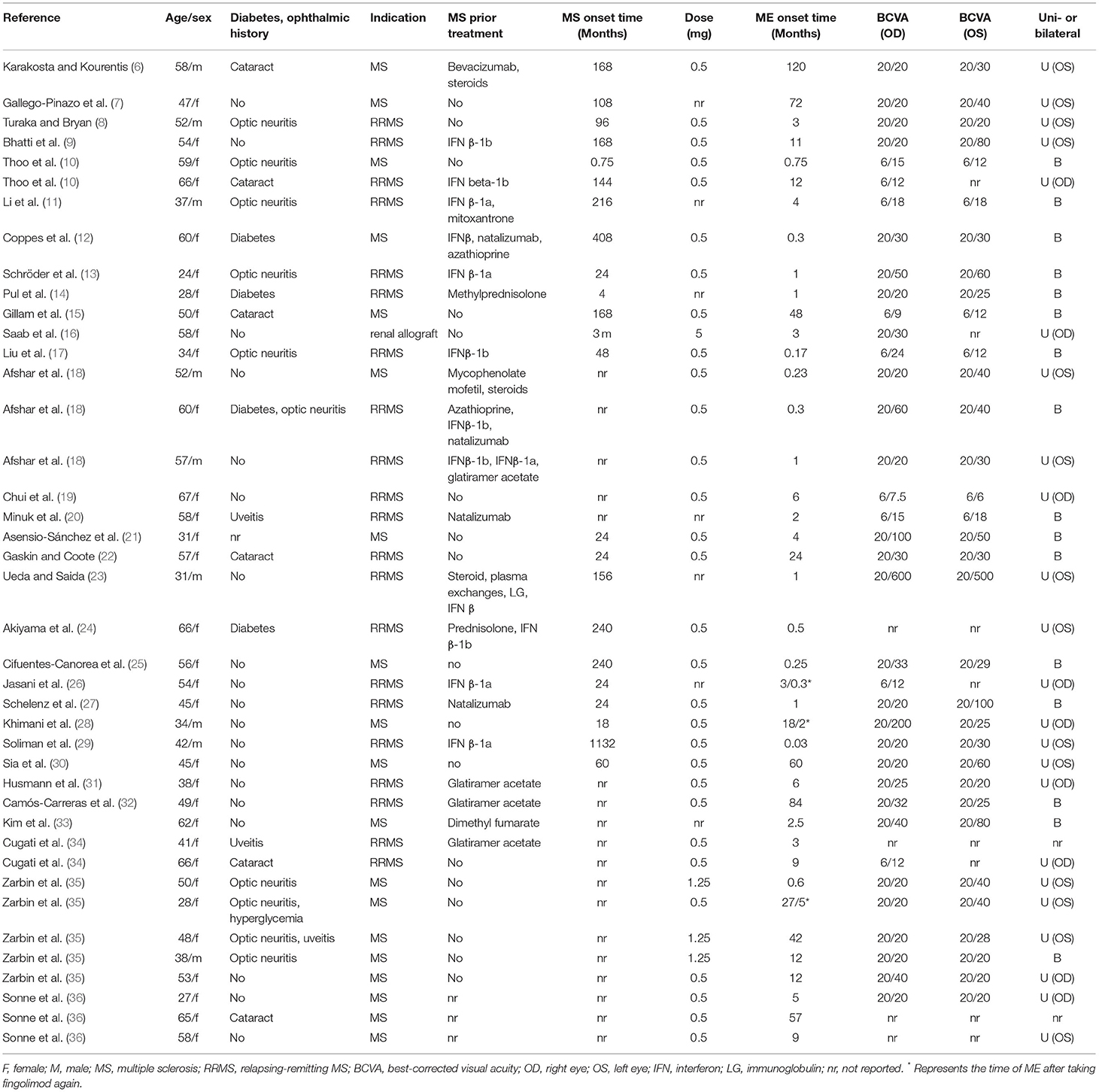

We included 31 studies according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria (6–36). The median age of the 41 patients was 51 years (range 21, 67), including 32 women and 9 men (Table 1). Fingolimod was used to treat MS in 19 patients, RRMS in 21 patients, and renal allograft in 1 patient. Fingolimod was administered at 0.5 mg (30 cases), 5 mg (1 case), 1.25 mg (3 cases,) and not described (7 patients). The median time to the occurrence of MS and RRMS was 78 m (range 0.75, 408). Of these patients, 2 had a history of uveitis, 10 had optic neuritis, 6 had cataracts, and 4 had diabetes. Twenty-one MS or RRMS patients were previously treated, including interferon (12 cases), glatiramer acetate (4 cases), natalizumab (4 cases), steroids (5 cases), azathioprine (2 cases), immunoglobulin (1 case), mitoxantrone (1 case), mycophenolate mofetil (1 case), dimethyl fumarate (1 case), bevacizumab (1 case), and plasma exchanges (1 case). The median time to onset of FAME was 3 m (range 0.03, 120). The median time to onset of ME in patients with diabetes or prior uveitis was 1 m (0.3, 42). Three patients restarted fingolimod and had a re-occurrence of macular edema at 10 d, 2, m and 5 m, respectively. Four patients developed FAME after cataract surgery.

Clinical Manifestations

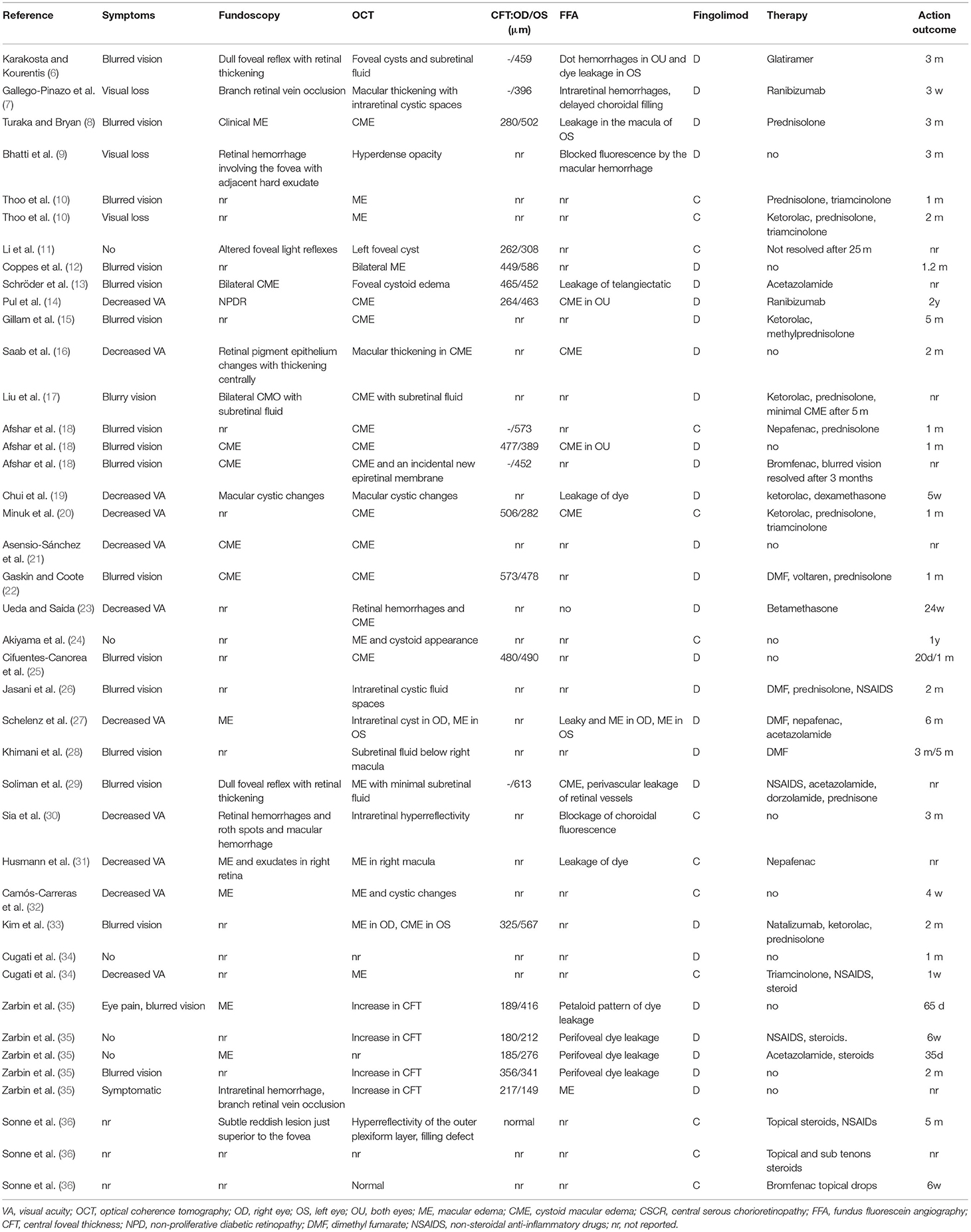

A total of 55 eyes were involved in 41 FAME patients, including the left eye (OS) in 14 patients, right eye (OD) in 10 patients, and both eyes (OU) in 15 patients. FAME patients mainly showed blurred vision (17 cases), decreased visual acuity (VA) (13 cases), eye pain (1 case), and asymptomatic vision (3 cases) (Table 2).

Table 2. Clinical manifestations, ophthalmic examination, treatment, and prognosis of 41 included patients.

Eye Examinations

Among the 55 eyes, 46 eyes had near-normal visual acuity (20/12-20/60), 5 eyes had moderate visual impairment (20/80-20/160), 2 eyes had severe visual impairment (20/200-20/400), and 1 eye had profound visual impairment (20/500-20/1000). The worst visual acuity reported for FAME patients was 20/500 (Table 1). Fundus examination in 23 patients mainly showed macular edema (11 cases), a dull foveal reflex with retinal thickening (4 cases), retinal hemorrhage (3 cases), and exudates (3 cases). Optical coherence tomography (OCT) in 39 patients mainly showed perifoveal cysts (24 cases), ME (23 cases), central foveal thickness (19 cases), subretinal fluid (4 cases), and hyperdense opacity (2 cases). Fundus fluorescein angiography (FFA) in 18 patients showed vascular leakage (11 cases), cystoid macular edema (6 cases), and choroidal filling (3 cases).

Treatment

Fingolimod was discontinued in 28 patients and continued in 13 patients (Table 2). Seven of 24 patients, who discontinued fingolimod, were switched to glatiramer (1 case), natalizumab (2 cases), and dimethyl fumarate (4 cases). For ME, 17 patients received no treatment, and 25 patients received therapy, including steroids (18 cases), non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (11 cases), ketorolac (7 cases), acetazolamide (4 cases), and ranibizumab (2 cases). ME completely resolved in 52 eyes at a median time of 2 m (range 0.25, 24). However, ME did not fully resolve in 3 eyes, and visual recovery was incomplete in 8 of 53 eyes.

Discussion

The incidence of FAME appeared to be dose-dependent, occurring in 0.4% of patients receiving 0.5 mg and 1% of patients receiving 1.25 mg (37). Our study found that FAME occurred mainly 3 m after the initiation of fingolimod, consistent with the phase III MS study and their extensions (14). However, a small proportion of patients develop late-onset ME (more than 12 months) (6, 15, 24, 30, 35), and blurred vision has also been reported as early as 24 h after initiation of the 0.5 mg dose (29). Patients with ME with diabetes or previous uveitis appear to develop it earlier. FAME cases can be unilateral or bilateral and can present with blurred vision, decreased vision, or no symptoms.

The diagnosis of FAME is based on OCT scanning and FFA to rule out any possible cause of ME. FAME is more likely to occur in patients with a history of diabetes, uveitis, or undergoing cataract surgery (38). Foveal thickening, foveal cysts, subretinal fluid, or dye leakage were seen on OCT scan and FFA in patients with FAME. In addition, ME associated with uveitis due to MS should also be excluded (39).

In addition to having a baseline eye exam before starting fingolimod, the FDA also recommends that patients have an eye exam 3 to 4 months after initiating the drug (35). However, the optimal frequency of follow-up periodic re-evaluation has not been determined, but some researchers recommend regular eye exams after 6 months and then annually (35). Patients who had fingolimod therapy, and who are also undergoing ophthalmic surgery, such as cataract surgery, may be at increased risk of developing ME and may benefit from increased monitoring or preventive treatment for ME (10, 15, 22, 34). Patients who have started fingolimod with a history of diabetes mellitus, uveitis, or concomitant medication associated with ME require closer monitoring.

Although the exact pathogenesis of FAME has not been determined, the likely mechanism is the disruption of the inner blood-retinal barrier. Sphingosine 1-phosphate (SIP) is a biologically active sphingolipid metabolite with five G protein-coupled receptors (S1PR 1-S1PR 5) (40). These receptors are found in nearly every cell type in the body, including lymphocytes, endothelial cells, neurons, and astrocytes. S1PR1 signaling is responsible for maintaining cell-to-cell and cell-to-matrix adhesion. Fingolimod downregulates S1P1R and antagonizes S1P2 R/S1P3R, thus, leading to downregulation of adhesion complexes and increased retinal vascular permeability, resulting in ME (41).

No consensus on best management has yet been established for FAME. Most patients with FAME resolve spontaneously after discontinuation of fingolimod. It should be noted that attempts to restart fingolimod resulted in recurrence of ME, which resolved after discontinuation. For patients requiring continued treatment, topical NSAIDs (e.g., nepafenac, bromfenac, and ketorelac), topical corticosteroids (e.g., prednisolone, and dexamethasone), and carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (e.g., acetazolamide) have been used to accelerate the resolution of FAME. More invasive interventions, such as subconjunctival or intravitreal administration of steroids (triamcinolone) or anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (e.g., ranibizumab and bevacizumab), may be required for refractory FAME (42). Some patients may not respond to topical anti-inflammatory therapy. Intravitreal corticosteroids may be an appropriate treatment option for patients with FAME who are refractory to topical anti-inflammatory therapy (34). However, caution must be exercised whenever steroids are used due to steroid-induced effects, such as ocular hypertension, glaucoma, and cataract formation (43). Patients should be informed of the risks and that they require ongoing monitoring. After the resolution of ME, a small proportion of patients had residual vision loss, which may be related to concurrent cataracts, uveitis, or optic neuritis. In addition, retinal damage is also a possible explanation (42). Determination of whether to discontinue fingolimod therapy should include an assessment of the individual patient's potential benefits and risks and their response to topical anti-inflammatory drugs.

In conclusion, ME is a known complication of fingolimod. FAME usually has a better prognosis with discontinuation or topical therapy. Eye exams are required before and after using fingolimod. Patients undergoing cataract surgery and with a history of diabetes and uveitis require closer monitoring.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

CW and SZ conceived of the presented idea. ZD, LS, WS, and CW analyzed and wrote the manuscript. SZ contributed to critical revision of the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Yeh EA, Weinstock-Guttman B. Fingolimod: an oral disease-modifying therapy for relapsing multiple sclerosis. Adv Ther. (2011) 28:270–8. doi: 10.1007/s12325-011-0004-6

2. Chun J, Hartung HP. Mechanism of action of oral fingolimod (FTY720) in multiple sclerosis. Clin Neuropharmacol. (2010) 33:91–101. doi: 10.1097/WNF.0b013e3181cbf825

3. Cohen JA, Barkhof F, Comi G, Hartung HP, Khatri BO, Montalban X, et al. Oral fingolimod or intramuscular interferon for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. (2010) 362:402–15. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907839

4. Kappos L, Radue EW, O'Connor P, Polman C, Hohlfeld R, Calabresi P, et al. A placebo-controlled trial of oral fingolimod in relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. (2010) 362:387–401. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909494

5. Ricca A, Boone K, Boldt HC, Gehrs KM, Russell SR, Folk JC, et al. Attaining functional levels of visual acuity after vitrectomy for retinal detachment secondary to proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Sci Rep. (2020) 10:15637. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-72618-y

6. Karakosta C, Kourentis C. Fingolimod-associated macular edema: a case report of late onset. Eur J Ophthalmol. (2021) 1120672121999632. doi: 10.1177/1120672121999632

7. Gallego-Pinazo R, España-Gregori E, Casanova B, Pardo-López D, Díaz-Llopis M. Branch retinal vein occlusion during fingolimod treatment in a patient with multiple sclerosis. J Neuroophthalmol. (2011) 31:292–3. doi: 10.1097/WNO.0b013e31822bed20

8. Turaka K, Bryan JS. Does fingolimod in multiple sclerosis patients cause macular edema? J Neurol. (2012) 259:386–8. doi: 10.1007/s00415-011-6367-4

9. Bhatti MT, Freedman SM, Mahmoud TH. Fingolimod therapy and macular hemorrhage. J Neuroophthalmol. (2013) 33:370–2. doi: 10.1097/WNO.0b013e31829b42e1

10. Thoo S, Cugati S, Lee A, Chen C. Successful treatment of fingolimod-associated macular edema with intravitreal triamcinolone with continued fingolimod use. Mult Scler. (2015) 21:249–51. doi: 10.1177/1352458514528759

11. Li V, Kane J, Chan HH, Hall AJ, Butzkueven H. Continuing fingolimod after development of macular edema: a case report. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. (2014) 1:e13. doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000000013

12. Coppes OJ, Gutierrez I, Reder AT, Ksiazek S, Bernard J. Severe early bilateral macular edema following fingolimod therapy. Mult Scler Relat Disord. (2013) 2:256–8. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2012.11.004

13. Schröder K, Finis D, Harmel J, Ringelstein M, Hartung HP, Geerling G, et al. Acetazolamide therapy in a case of fingolimod-associated macular edema: early benefits and long-term limitations. Mult Scler Relat Disord. (2015) 4:406–8. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2015.06.015

14. Pul R, Osmanovic A, Schmalstieg H, Pielen A, Pars K, Schwenkenbecher P, et al. Fingolimod associated bilateral cystoid macular edema-wait and see? Int J Mol Sci. (2016) 17:2106. doi: 10.3390/ijms17122106

15. Gillam M, Richardson T. Bilateral fingolimod-associated macular oedema development after cataract surgery. BMJ Case Rep. (2021) 14:e240562. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2020-240562

16. Saab G, Almony A, Blinder KJ, Schuessler R, Brennan DC. Reversible cystoid macular edema secondary to fingolimod in a renal transplant recipient. Arch Ophthalmol. (2008) 126:140–1. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2007.23

17. Liu L, Cuthbertson F. Early bilateral cystoid macular oedema secondary to fingolimod in multiple sclerosis. Case Rep Med. (2012) 2012:134636. doi: 10.1155/2012/134636

18. Afshar AR, Fernandes JK, Patel RD, Ksiazek SM, Sheth VS, Reder AT, et al. Cystoid macular edema associated with fingolimod use for multiple sclerosis. JAMA Ophthalmol. (2013) 131:103–7. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.570

19. Chui J, Herkes GK, Chang A. Management of fingolimod-associated macular edema. JAMA Ophthalmol. (2013) 131:694–6. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.47

20. Minuk A, Belliveau MJ, Almeida DR, Dorrepaal SJ, Gale JS. Fingolimod-associated macular edema: resolution by sub-tenon injection of triamcinolone with continued fingolimod use. JAMA Ophthalmol. (2013) 131:802–4. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.2465

21. Asensio-Sánchez VM, Trujillo-Guzmán L, Ramoa-Osorio R. Cystoid macular oedema after fingolimod treatment in multiple sclerosis. Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol. (2014) 89:104–6. doi: 10.1016/j.oftale.2014.05.004

22. Gaskin JC, Coote M. Postoperative cystoid macular oedema in a patient on fingolimod. BMJ Case Rep. (2015) 2015:bcr2015210415. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2015-210415

23. Ueda N, Saida K. Retinal hemorrhages following fingolimod treatment for multiple sclerosis; a case report. BMC Ophthalmol. (2015) 15:135. doi: 10.1186/s12886-015-0125-9

24. Akiyama H, Suzuki Y, Hara D, Shinohara K, Ogura H, Akamatsu M, et al. Improvement of macular edema without discontinuation of fingolimod in a patient with multiple sclerosis: a case report. Medicine. (2016) 95:e4180. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000004180

25. Cifuentes-Canorea P, Nieves-Moreno M, Sáenz-Francés F, Santos-Bueso E. Early and recurrent macular oedema in a patient treated with fingolimod. Neurologia. (2019) 34:206–7. doi: 10.1016/j.nrleng.2018.09.005

26. Jasani KM, Sharaf N, Rog D, Aslam T. Fingolimod-associated macular oedema. BMJ Case Rep. (2017) 2017:bcr2016218912. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2016-218912

27. Schelenz D, Kleiter I, Schöllhammer J, Rehrmann J, Elling M, Dick HB, et al. Early onset of fingolimod-associated macular edema. Ophthalmologe. (2018) 115:424–8. doi: 10.1007/s00347-017-0526-7

28. Khimani KS, Foroozan R. Central serous chorioretinopathy associated with fingolimod treatment. J Neuroophthalmol. (2018) 38:337–8. doi: 10.1097/WNO.0000000000000592

29. Soliman MK, Sarwar S, Sadiq MA, Jack L, Jouvenat N, Zabad RK, et al. Acute onset of fingolimod-associated macular edema. Am J Ophthalmol Case Rep. (2016) 4:67–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ajoc.2016.09.005

30. Sia PI, Aujla JS, Chan WO, Simon S. Fingolimod-associated retinal hemorrhages and roth spots. Retina. (2018) 8:e80–1. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000002334

31. Husmann R, Davies JB, Ghannam M, Berry B, Kelkar P. Fingolimod-associated macular edema controlled with nepafenac non-steroidal anti-inflammatory opthalmologic applications. Clin Mol Allergy. (2020) 18:3. doi: 10.1186/s12948-020-00119-4

32. Camós-Carreras A, Alba-Arbalat S, Dotti-Boada M, Parrado-Carrillo A, Bernal-Morales C, Saiz A, et al. Late onset macular oedema in a patient with multiple sclerosis treated with fingolimod. Neuroophthalmology. (2020) 45:61–4. doi: 10.1080/01658107.2020.1821065

33. Kim MJ, Bhatti MT, Costello F. Famous. Surv Ophthalmol. (2016) 61:512–9. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2015.12.008

34. Cugati S, Chen CS, Lake S, Lee AW. Fingolimod and macular edema: Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. Neurol Clin Pract. (2014) 4:402–9. doi: 10.1212/CPJ.0000000000000027

35. Zarbin MA, Jampol LM, Jager RD, Reder AT, Francis G, Collins W, et al. Ophthalmic evaluations in clinical studies of fingolimod (FTY720) in multiple sclerosis. Ophthalmology. (2013) 120:1432–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.12.040

36. Sonne SJ, Smith BT. Incidence of uveitis and macular edema among patients taking fingolimod 05 mg for multiple sclerosis. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. (2020) 10:24. doi: 10.1186/s12348-020-00215-1

37. Mandal P, Gupta A, Fusi-Rubiano W, Keane PA, Yang Y. Fingolimod: therapeutic mechanisms and ocular adverse effects. Eye. (2017) 31:232–40. doi: 10.1038/eye.2016.258

38. Olsen TG, Frederiksen J. The association between multiple sclerosis and uveitis. Surv Ophthalmol. (2017) 62:89–95. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2016.07.002

39. Gelfand JM, Nolan R, Schwartz DM, Graves J, Green AJ. Microcystic macular oedema in multiple sclerosis is associated with disease severity. Brain. (2012) 135:1786–93. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws098

40. Spiegel S, Milstien S. Sphingosine-1-phosphate: an enigmatic signalling lipid. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. (2003) 4:397–407. doi: 10.1038/nrm1103

41. Lee JF, Gordon S, Estrada R, Wang L, Siow DL, Wattenberg BW, et al. Balance of S1P1 and S1P2 signaling regulates peripheral microvascular permeability in rat cremaster muscle vasculature. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. (2009) 296:H33–42. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00097.2008

42. Jain N, Bhatti MT. Fingolimod-associated macular edema: incidence, detection, and management. Neurology. (2012) 78:672–80. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318248deea

Keywords: fingolimod, multiple sclerosis, macular edema, visual acuity, vision loss

Citation: Wang C, Deng Z, Song L, Sun W and Zhao S (2022) Diagnosis and Management of Fingolimod-Associated Macular Edema. Front. Neurol. 13:918086. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2022.918086

Received: 12 April 2022; Accepted: 13 June 2022;

Published: 15 July 2022.

Edited by:

Jodie Burton, University of Calgary, CanadaReviewed by:

Bradley Smith, The Retina Institute, United StatesEssam Mohamed Elmatbouly Saber, Benha University, Egypt

Copyright © 2022 Wang, Deng, Song, Sun and Zhao. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shaoli Zhao, emhhb3NsMTE5QDE2My5jb20=; orcid.org/0000-0003-2301-6825

Chunjiang Wang

Chunjiang Wang Zhenzhen Deng

Zhenzhen Deng Liying Song

Liying Song Wei Sun

Wei Sun Shaoli Zhao

Shaoli Zhao