- 1Center of Nursing Excellence, UCLA Health, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, United States

- 2School of Nursing, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, United States

- 3Department of Neurosurgery, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, United States

Background: Surgical resection is frequently the recommended treatment for drug-resistant temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE), yet many factors play a role in patients' perceptions of brain surgery that ultimately impact decision-making. The purpose of the current study was to explore how people with epilepsy, in their own words, experienced the overall process of consenting to surgery for drug-resistant TLE.

Methods and Materials: Data was drawn from in-person, semi-structured interviews of 19 adults with drug-resistant TLE eligible to undergo epilepsy surgery. A systematic thematic analysis was performed to code, sort and compare participant responses. The mean age of these 12 (63%) women and seven (37%) men was 37.6 years (18–68 years), with average duration of epilepsy of 13 years (2–30 years).

Results: Meeting the neurosurgeon and consenting to surgery represented an important treatment milestone across a prolonged treatment trajectory. Four themes were identified: (1) Understanding the language of risk; (2) Overcoming risk; (3) Family-centered, shared decision-making, and (4) Building decisional-confidence.

Conclusion: Despite living with the restrictions of chronic uncontrolled seizures, considering an elective brain procedure raised unique and complex questions. Personal beliefs and expectations related to treatment outcomes influenced how the consent process was ultimately experienced. Decisions to pursue surgery had frequently been made ahead of meeting the surgeon, with many describing the act of signing as personally empowering. Overall, satisfaction was expressed with the information provided during the surgical visit, despite later inaccurate recall of the facts. These findings support the resultant recommendation that the practice of informed consent be conceptualized as a systematic, structured interdisciplinary process which occurs over time and encompasses three stages: preparation, signing and follow-up after signing.

Introduction

The advantages of epilepsy surgery for seizure control have been established by Class 1 evidence (1, 2). However, electing to under go an irreversible brain procedure represents a complex decisional process for both people with epilepsy (PWE) and clinicians, that includes weighing surgical risks against expectations for seizure freedom and a hopeful future (3). Even in well-selected candidates, and despite illness severity, firmly held beliefs especially fear, influence whether patients will choose or defer surgery (4, 5). Although the risks of permanent, noticeable neurological deficits due to surgery are small (6), physician and patient misperceptions of surgical risk remain a significant barrier to an effective treatment (7, 8).

In general, a central goal of informed consent is to inform and manage risk such that patients feel they have sufficient information about a planned procedure and the alternatives, to make a rational choice (9). Risk management is a process that takes place over time (10), incorporates the contributions of multidisciplinary team members and is foundational to building trust (11, 12). How surgical risks are presented and understood have implications for approaches to providing information about surgery and ultimately signing (or not) an informed consent (12, 13).

Specific to epilepsy surgery, preoperative counseling includes weighing up the substantial risks for morbidity and mortality of uncontrolled seizures vs. the potential risks of the operation. Complication rates associated with epilepsy surgery are reported as “low” and mostly minor and temporary (6). Counseling for epilepsy surgery should be individually tailored to balance the possibilities of seizure-freedom after surgery against potential procedure related cognitive losses (14). The impact of surgery on memory is always a consideration in TLE, leading authors to suggest that memory decline should be viewed as a cost of surgery and not necessarily a surgical risk (14).

The goal of epilepsy surgery is to achieve seizure freedom. However, a potentially life-changing shift from chronic disability to sudden wellness evokes unique psychological and philosophical adjustments described as the concept of ‘burden of normality' (15). In a substantial body of work, Wilson and colleagues illustrate the concept in a theoretical framework comprising the broad, interrelated psychosocial features that shape patient identity and family behavior. This framework that conceptualizes the reversal of disability has significant application to surgical outcomes (16). The identification of key features are frequently neglected by questionnaires related to quality of life (15). Consequently, the role of the epilepsy team in comprehensive patient evaluation is underscored, with specific emphasis on the potential of specialized epilepsy nurses for promoting individualized care and shared decision-making.

Although the complexity of decision-making in epilepsy surgery has been described (14, 17, 18), there appears to be a dearth of studies in the epilepsy literature dedicated to the process of obtaining the informed surgical consent. Signing an informed consent does not guarantee the understanding of information provided, as shown in studies of informed consent in clinical trials research (19) and a qualitative research study of patients who had consented for general surgical treatment (20). What was understood and remembered was mostly subjective and influenced by emotional responses (21). To improve communication, supplemental, high-quality decision-aids have been shown through randomized control trials to be effective in supporting understanding and recall (21, 22). Decision-making shared between patient and physician, actualizes the concept of informed consent (12). Such shared decision-making is especially important when treatment outcomes are uncertain (12), and therefore holds specific relevance for decisions about epilepsy surgery. Underutilization of effective and safe surgical therapy for epilepsy is longstanding and vexing (23, 24). Furthermore, the recently documented decline in number of open resective epilepsy surgeries performed (8), co-incides with the advent of new surgical therapies, such as responsive neurostimulation and stereotactic thermal ablation. In light of expanded therapies, understanding key aspects of surgical decision-making naturally takes on heightened importance.

Conclusions from our larger study of patient perceptions of risks and benefits (3), were that an elective brain procedure for a chronic and frequently life-long condition, raised uniquely complex questions for PWE and their families when surgery was presented as an option. As part of the parent study, the purpose here was to explore how people with pharmaco-resistant TLE experienced the process of signing the informed consent for epilepsy surgery. As an understudied aspect of treatment, exploring personal experiences of this consenting process may offer a new angle on how to overcome underutilization of epilepsy surgery.

Materials and Methods

The techniques of constructivist grounded theory guided the initial design of this qualitative study, the data collection, and initial analysis. The philosophical cornerstones of grounded theory included paving the way to understanding how study participants construct what is meaningful to them and how they act. This methodology was selected as the best way to explain how knowledge was perceived, internalized and recalled (25). We utilized the flexibility of thematic analysis to present the findings (26).

Setting and Background

Data for this manuscript originated from a parent qualitative study (N = 35) where the contextual basis of decision-making centered on how treatment risks and benefits were described (3). In the present study, we focus on the subgroup of 19 participants who had signed an informed consent to undergo a craniotomy and surgical resection of epileptogenic tissue. Study participants were adults seeking treatment for uncontrolled temporal lobe seizures at a leading, academic epilepsy center in the United States. Before they signed the informed consent, the first author, a clinical nurse specialist, invited eligible patients on the surgical waiting list to participate in a semi-structured interview about their understanding of treatment options including surgery. All invited patients in this convenience sample agreed to participate.

Standard consent process. At the time the informed consent was obtained, patients were typically meeting and receiving information about the surgery from the neurosurgeon (IF) for the first time and simultaneously signing a surgical consent form should they wish to proceed. The clinical nurse specialist (SD), who was known to the patients, was present to actively contribute to the consent process by articulating key elements of the clinical history relevant to individual surgical risks and to clarify explanations for the patient, family members and surgeon.

The consent form was a standard document used for surgical procedures at our medical center. Upon signing, the patient agreed that a description of the surgical procedure was provided, the reasons for the surgery had been given, and the risks, benefits and treatment alternatives have all been explained. Patients and any caregivers present were given the opportunity to ask questions about the procedure, the recovery process, and the benefits of surgery. The name of the procedure was repeated several times during the consultation and a copy of the signed consent form was provided to the patient. Five (26%) participants received surgery within a week of signing the informed consent. Of the remaining 14, 12 (63%) participants underwent surgery several weeks later while 2 (11%) eventually opted not to undergo surgery.

Participant Selection, Study Procedure and Data Collection

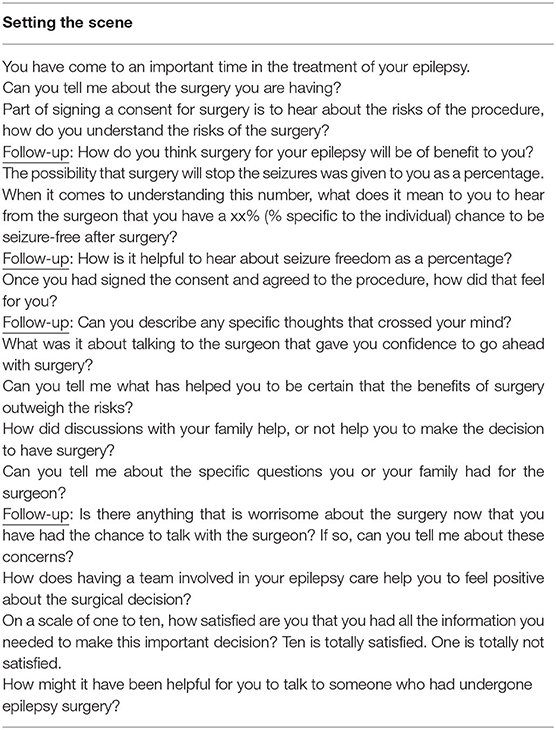

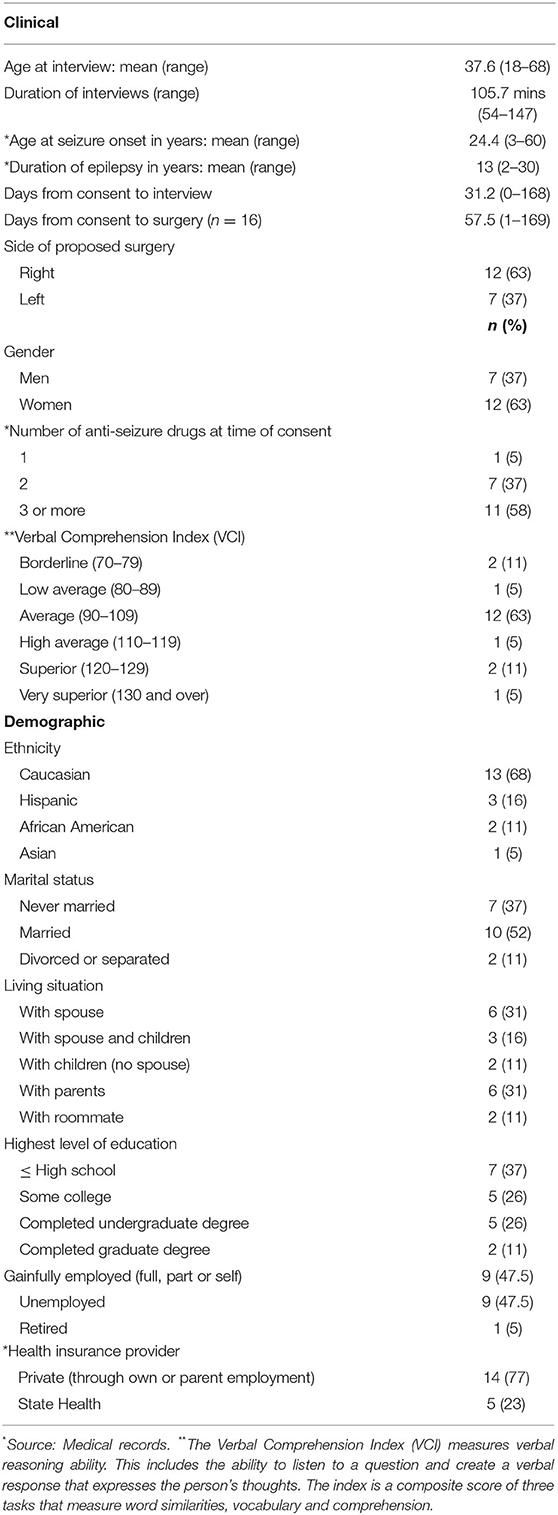

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained prior to recruitment. Participants were English speaking adults with drug-resistant temporal lobe epilepsy, who were legally able to sign their own surgical consent. Patients who had undergone a previous brain resection were excluded to avoid the potential bias that a past experience of signing an informed consent may bring. An in-person research consent was obtained and a time convenient to the participant was scheduled for the interview once the surgical consent had been signed. All interviews were conducted one-on-one in a comfortable, private room in the clinic, by an experienced, female qualitative researcher with a background in neuropsychology, and who was not part of the clinical team. A semi-structured script provided a flexible guide for data collection. Selected questions from the guide are provided in Table 1. Although seven (37%) participants chose to be interviewed on the same day as meeting the surgeon, the interviews were conducted an average of 31.2 days after the consent had been signed.These audio-recorded interviews lasted an average of 105.7 min each (range: 54–147 min). Participants received a honorarium of $50 cash on completion of the interview as a token of appreciation for their time. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample were derived from the medical records (Table 2). The verbal comprehension index (VCI) was obtained from the standardized neuropsychological battery derived from the Weschler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS) version 4. Neuropsychological testing conducted by a licensed psychologist is an essential component of an epilepsy surgery evaluation at our medical center.

Extensive analytic memos were written after each interview to describe analytic hunches, identify commonalties and differences, and inform potential new questions to promote deeper descriptions in future interviews. In addition, observational memos were written by the clinical nurse specialist shortly after the surgical consent was obtained to record her observations of the process. As part of the study, and since she played an active role in this aspect of treatment, the CNS paid special attention to how the information was presented, and observed the emotional responses of the patients and family members who were present.

Data Analysis

Interview scripts were transcribed verbatim by a professional transcriptionist, checked for accuracy and de-identified. Data analysis by the first and second authors followed the principles of a robust, thorough and systematic analysis based on the phases of coding described by Braun and Clarke (26). The data set for the parent study was coded independently by the analytic dyad (SD and HP). Codes were agreed upon, sorted and compared across participants to identify similarities and differences. Reflexive memos in qualitative research contain the clues to recurring ideas in the data and their relationships to one another (27). Our memos contributed to data interpretation, and supported the identification and development of themes. Regular meetings throughout the analytic process boosted interpretations that reflected the data. ATLAS.ti was used to manage and organize the codes and record the reflexive memos (28).

In keeping with the guidelines on data analysis of Braun and Clarke, the ongoing dialogue between the analytic dyad facilitated agreement upon four themes that accurately captured the essence of a rich data set (26). Theoretical saturation was reached once the themes with their properties and dimensions were determined to represent a logical, detailed and complete account of the data.

Results

The sample characteristics, shown in Table 2 included 19 adults with a mean age of 37.6 years (18–68), and drug-resistant temporal lobe epilepsy for an average of 13 years (2–30). Of these 12 (63%) women and seven (37%) men, seizure onsets were localized to the right temporal in 12 (63%) cases. The study participants reported an average of 14.2 years (12–20) of education. Verbal comprehension scores obtained from neurocognitive testing fell within the low to high average range in 14 (74%) cases, two (10%) were within the borderline range and three (16%) were in the superior range. As a component of IQ, these scores reflect verbal reasoning ability, and include a person's ability for comprehension and verbal expression. Interviews were conducted an average of 31 days (0–168) after signing the consent with seven (37%) preferring to interview on the same day, shortly after meeting the surgeon. Surgery itself occurred an average of 57.5 days after consenting (n = 16) (Table 2). Excluded from the latter calculation were two patients who declined surgery and one whose surgery was unusually delayed for 355 days.

Meeting the surgeon and signing the consent form represented an important treatment milestone. Although the surgery followed an extensive evaluation process and was viewed as a positive step, the reality of removing brain tissue lay outside personal experience. Surgery signified an opportunity to achieve seizure freedom and lessen caregiver burden, but the risks of a surgical complication, albeit presented as “low” still meant that fear and uncertainty had to be overcome. A woman in her mid-thirties expressed the existential meaning of “cutting out a piece” of a vital organ and the courage it took to consider elective brain surgery saying:

When I was diagnosed with epilepsy nine years ago, I was totally against surgery because I was scared. It was something totally new, and it made me feel old. Now I'm not scared. I'm ready…Now it's time to move forward and do something.

Despite inherent unknowns, it was also apparent that decisions in favor of surgery were frequently made in advance of meeting the surgeon, and signing the IC was viewed as a simple formality. Yet, having signed the consent, becoming mentally prepared for surgery became all-consuming and was described as “the last thing on my mind when I go to bed, and the first thing on my mind when I wake up.”

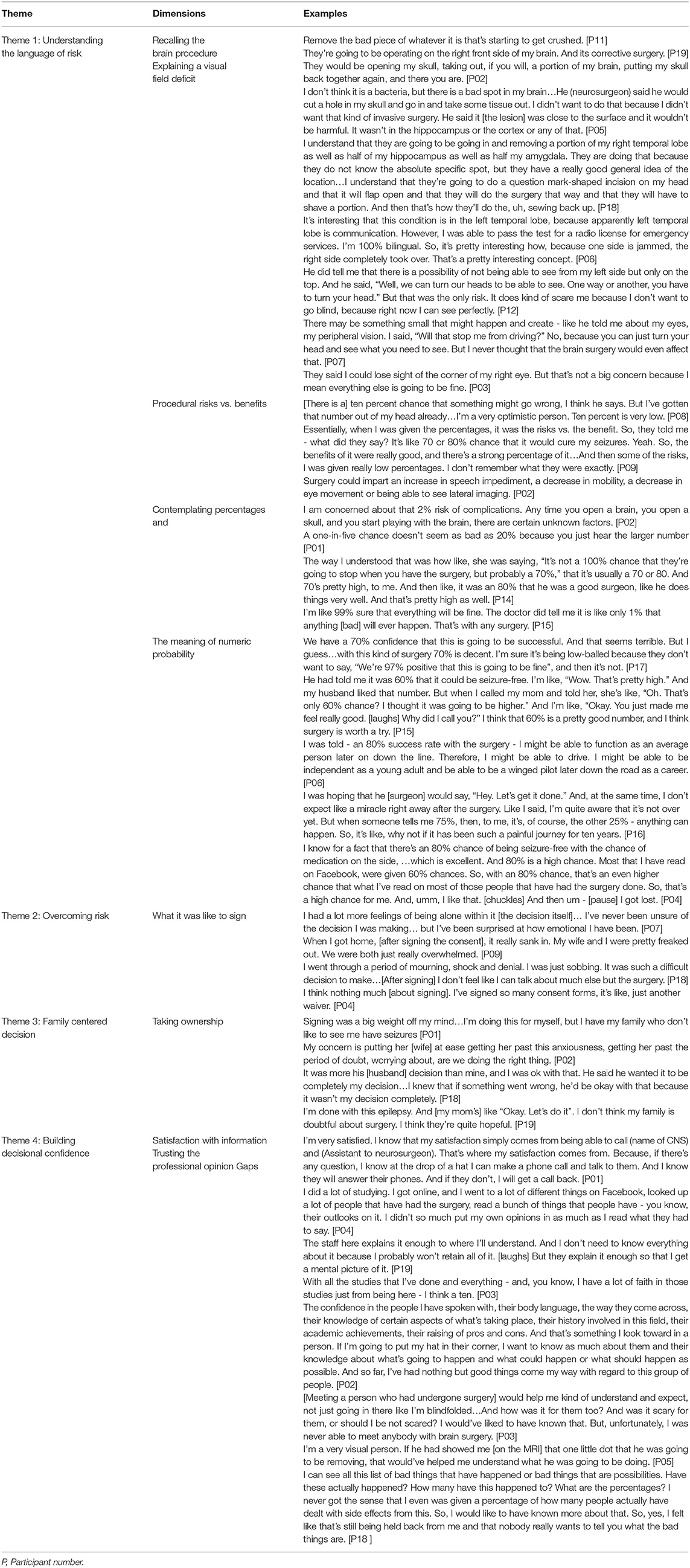

Overall, four themes informed the experiences of signing the IC. The first, understanding the language of risk, included comprehension of the procedure and the surgical risks. The second encompassed how risk was overcome and benefits prioritized. Theme three revolved around the integral nature of family-centered decision-making and emphasized who ultimately owned the surgical decision. In the last theme, decisional confidence and satisfaction with information was captured. Illustrative quotes representing each theme are provided in Table 3.

Theme 1: Understanding the Language of Risk

Recalling the Brain Procedure

Participants' views of the brain as a vital organ influenced how surgical decisions were made. Such views included questioning whether seizures themselves could damage the brain, but also evoked images of the life-long implications should a surgical complication occur. Recall of the procedure consistently included locating the head shave above the ear, in the general region of the temporal lobe, and stating that the skin incision would take the form of a question mark. Although the scar would be behind the hairline, the size of the incision and the amount of tissue to be removed mattered. Participants commonly referred to a “small” incision or a “small” head shave, and resection of a “small” amount of tissue. To underscore a shared experience, participants spoke collectively about their understandings as illustrated in the words of one person who said of herself and her spouse, “We had a picture of ourselves having a dime-size taken out of my brain. By the time I was done talking to the surgeon, we realized we were talking about a much larger section.”

When asked what operation was to be done, participants had frequently forgotten the procedure name, and described the surgery in general terms such as, “lesion extraction,” “corrective,” or “minimally invasive?” In recounting the surgeon's explanation, one participant shared, “I didn't know all the words he was saying about the pieces of the brain, but I know that it's up here [points to left side of head].” Although the surgeon stated that surgery was to be performed on the anterior or front part of the temporal lobe, some participants explained that surgery would be on the right or left “front side”, others referred simply to “removing the part that's causing the seizures”. Seven (37%) participants clearly named the temporal lobe as the site of surgery, and two were also able to correctly name the mesial structures, i.e., the amygdala and hippocampus as implicated in the seizure network.

The specialized memory functions of right and left temporal lobe structures were explained by the surgeon, nevertheless participants' concerns about post-operative changes in memory tended to center around losing memory for important past events, or fears of forgetting loved ones. Especially in the language dominant group (n = 7), word-finding deficits were understood to imply a communication difficulty with one participant imagining that “loss of speech” would mean he would need to relearn language as in childhood. A participant who required a left-sided antero-mesial temporal lobe resection explained her understanding of the brain region and what it meant to her to have surgery in this part, saying that the surgeon “doesn't want to get close to my speech and memory section because they're very strong…, and he does not want to interfere with a part of who I am.” Two participants feared language deficits despite the plan for surgery on the side contralateral to language localization. Concerns about memory loss were expressed across participants especially since poor memory was a pre-existing challenge. Yet for some participants, stopping the seizures raised hopes that memory would improve after surgery to potentially improve learning ability.

The potential for a visual field deficit, was consistently remembered however this deficit was sometimes understood to imply vision loss, blindness, or restricted eye movements. Although participants were uncertain about what a visual deficit meant, the relevance of the deficit was openly dismissed, and expressed as “not a big deal.”

Dying from the procedure was a risk that was always mentioned by the surgeon, however, participants did not initiate further discussion about this possibility. In contrast, fear of dying was expressed during the interviews, with many participants foreseeing deep family grief should death occur. Although viewed as improbable, the possibility of dying was seen as part of the reality of surgery. Some participants spoke about the potential for dying from seizures, but most also thought this was unlikely to happen to them. Participants rationalized that living with post-operative motor or language impairments, might be worse than dying from the procedure. The possibility of weakness or paralysis due to stroke meant “having useless body parts” and being functionally worse off.

Understanding Percentages

Taking into account individual elements of the clinical presentation, two percentages are typically presented during the consent process: the risk of procedural complications and side-effects, and an estimate of seizure-free outcome. The possibility of serious procedural complications for temporal lobe surgery were usually quoted as less than one percent with participants in the present sample given a likely probability of seizure freedom ranging between 60–80%. While participants were generally concerned about surgery on the brain, hesitancy appeared greatest when they, or the family, focused specifically on the possibility of procedural complications rather than the benefits of seizure freedom. In contrast, when the benefits of seizure freedom were uppermost in people's minds, the surgical decision appeared to be made with less hesitation. Anticipating 80% seizure freedom was associated with “cure”, by several participants. One person was disappointed in an estimated 70% seizure-free rate and felt the number was purposefully “low-balled”.

The two percentages (procedural risks and estimated seizure-free outcome) were frequently mis-remembered. Some participants spontaneously explained that risks were quickly forgotten, as they preferred to focus on the belief that everything would go well. Despite incorrectly remembering the risks to be 10–15%, the over-riding take-home message was that surgical risks are “low” or “very, very rare.” Regarding the second percentage routinely discussed during consenting, there was unanimous acceptance that surgery would not offer 100% guarantee of seizure freedom, yet participants were cautiously optimistic. One participant said she was quoted a 25% possibility of seizure freedom which she determined was acceptable to her and represented a “big chance” of control. Regardless of the percentage quoted, participants, in their own minds, anticipated better outcomes. Although most participants were happy to hear percentages, one person preferred to hear a 1-in-5 chance vs. 20% (ie. a percentage), because “the numbers are smaller.”

Overall, hearing the numbers was helpful in decision-making even when the percentages were recalled incorrectly. Clearly, the number itself held meaning beyond the numeric value. As such, the percentage was not a defining entity, but represented a fluid and hopeful measure, especially when compared to past experiences with ineffective anti-seizure drugs.

Theme 2: Overcoming Risk

Participants who expressed little hesitation to undergo surgery tended to minimize procedural risks and focused on the benefits of a positive outcome, that included coming off anti-seizure drugs, driving and “fixing an epileptic self.” A young woman who weighed the benefits of surgery as 99.9% greater than the risks said, “I'm not worried about the risks. Thinking about the pros and cons, will get me nowhere.” Others also admitted to quickly dismissing the surgical risks, preferring to focus on an overall positive outcome as exemplified by the participants who rationalized that a 1–2% risk meant there was a 98% chance of a good outcome leaving “the 2% to be ignored.”

Across the sample, individuals reasoned that their quality of life needed to improve and that, without surgery, seizures and memory were likely to worsen. Perceptions of an optimistic future were guided by faith, including beliefs that surgery was in God's greater plan. When reflecting on their drug-resistant disease, many reasoned they had little choice, and nothing to lose but to go ahead with surgery.

Trust in the surgeon's skill was necessary to overcome a natural fear of brain surgery. When weighed against hard-won personal accomplishments such as academic or work achievements despite epilepsy, participants feared a changed or diminshed self after surgery. While some did not consider themselves to be limited by the seizures, a negative surgical outcome would be life-limiting. Participants in the current sample deliberately identified non-verbal cues that projected the surgeon's considerable experience and his confidence regarding a positive outcome. In addition, participants looked to family members who were present during the clinic visit to affirm trust. Faith in the institution and the team, especially the neurologist were spontaneously and frequently expressed as playing key roles in accepting the surgical option.

What it Was Like to Sign

High risks were naturally associated with brain surgery, making signing the consent an overwhelming experience for some. These emotional responses to knowledge about the surgical risks came as a surprise to the individuals and differed widely across the sample ranging from deep relief and excitement, to feeling overwhelmed and anxious. Excitement centered around seeing surgery as a proactive step after many years of disappointment with medicines. Visceral responses such as losing appetite and crying were reported to last for many days after signing. For some, the act of signing triggered self-reflective thoughts around what was important in life. For younger participants, the act of signing symbolized the assuming of an adult responsibility. While some participants expressed resignation about signing the consent, others viewed the IC as routine, non-binding, and simply a legal formality. A participant with a superior verbal comprehension score was critical that the focus of the clinical encounter was on surgical risks, and expressed her preference for more information on the benefits of surgery for daily living and life-style adjustment. Overall, surgical therapy was viewed with optimism especially when weighed against recurring disappointments of drug failure.

Theme 3: Family-Centered, Shared Decision-Making

All participants ultimately took ownership of the final decision to undergo surgery, but family opinions were both powerful motivators and barriers. Until this point, family members had initiated and supported specialized epilepsy care, but embracing the decision to undergo brain surgery was far more complex. It was apparent that patients and families were observed to process fear of brain surgery in different ways, and to view the need for epilepsy surgery and the inherent risks differently. There were many advantages for family caregivers to be present for the surgical explanation as discussions with the surgeon could be heard first-hand by all concerned. Three participants did not have family members present. For the majority of participants, questions raised by family members contributed positively to the decisional process, to increase confidence in proceeding with surgery. Neverthess, the inherent ambiguities of surgical decision-making were exemplified when a middle-aged, professional man with right TLE reflected upon his family's views of surgery:

“My wife is supportive of the surgery. She feels that there may be benefits. She's also as realistic, as I am, about not seeing it as a panacea or a cure-all but that there are, hopefully, some benefits to doing so. So, she's supportive of it. I don't think my sons have a clear understanding of the course of recovery.”

Owning the decision to have surgery meant taking personal responsibility for the decision and the outcome and appeared to be a way to protect the family should complications occur. The focus for a mother whose seizures began at age 29 years, “was just to survive the surgery” and later to “deal with whether the epilepsy was cured.”

The words of one teenager echoed those of other young people who said, “It's my brain, it's my body?. I'm no longer underage. I feel it's my decision to have surgery because I've gone through the seizures.” However, for one person a shared decision, implied sharing the responsibility for the decision should something go wrong. For most participants, decision-making included the family, and sometimes friends, but the decision took time and was clearly not straightforward. Ultimately, individuals declared that the time was right. There was little to lose by moving forward with a procedure, and participants were motivated by the need to reverse disability.

Theme 4: Building Decisional Confidence

Consenting for epilepsy surgery was the last formal step in a complex treatment process. The consent was viewed as a “formality” by some, and by others as a “symbol of reality.” Agreeing to surgery was based upon an active process of gathering information and building confidence in the decision. Participants spontaneously mentioned their observations of non-verbal cues. Sitting and talking, and making good eye contact were valued and identified as central to communicating the surgeon's confidence in the treatment approach.

The opinions of caregivers mattered. The positive affirmation of caregivers supported the surgical decision. Even when the clinics were perceived to be busy or visits felt rushed, participants rationalized that they were getting the best possible care. It was also apparent that participants and caregivers needed time after signing the consent to review their understanding and expectations, and in some cases to talk to other patients.

“It's calming for me to see that other people have gone through what I'm getting ready to go through and that they come out of it okay, and that they're not having seizures or they're having a lot fewer seizures. And they're on a lot less medication; and they're only having problems with wordplay; and they're still able to walk, talk, function, and, you know, some of the things that I'm curious and afraid of.”

Confidence was drawn from a comprehensive work-up that had been completed at a specialized epilepsy center, where the treatment plan was based on an interdisciplinary consensus. As one young man said, “a group of specialists makes the experience better. Having a team that is rooting for your wellbeing gives hope.”

Satisfaction With Information

When participants were asked to rate their confidence about how well-informed they felt to make the surgical decision, the median score on a scale of 1–10 was eight. One person said she was unable to provide a rating and was not included in the calculation. Although five (30%) participants were perfectly confident that they had all the information they needed, common reasons for less than 100% certainty included poor memory, and not knowing what questions to ask due to unfamiliarity with brain surgery. Lacking expertise in epilepsy surgery, in addition to uncertain expectations reinforced the need for implicit trust in the medical team. One participant (who came from a medical background) felt that risks were “downplayed”; that numbers who had died or suffered complications may have been purposefully withheld. Another felt that 100% certainty was not possible secondary to poor memory. Many people embraced self-education, but some did not know where to look for reliable information. Participants sought out and valued clarification of the surgical explanation from an experienced epilepsy nurse specialist.

Discussion

The aim of this descriptive, qualitative study was to explain what it was like for a sample of patients with drug-resistant epilepsy to experience the informed consent process for anterior temporal lobectomy. Drug-resistant epilepsy constitutes an inherently unclear illness course but agreeing to an elective brain procedure introduces new levels of uncertainty. Despite intrinsic uncertainties, the act of signing a surgical consent was often experienced as empowering in the context of a disempowering condition. Consenting symbolized a personal turning point that represented hope for an independent future. While opinions of family members played a role in treatment decisions, the participants unanimously assumed ownership of the surgical decision. Although detailed recall of the procedure and the risks were often incomplete or inaccurate, participants accepted that surgery was the best therapeutic option, and that risks while small, were not zero.

Distinct challenges confront both the treatment team and the patients when considering epilepsy surgery. While the surgical procedure is guided by underlying pathology it is tailored to the individual talents and lifegoals of the patient. The informed consent represents a collaborative, two-way process between patient and surgeon (12). However, informing patients with temporal lobe epilepsy and baseline memory deficits is uniquely challenging. Variations in levels of health and statistical literacy, and the amount of detail people wish to hear also need to be considered. Data from the semi-structured interviews highlighted what was recalled from the meeting with the surgeon and what was identified as important to the individuals in the current sample.

Prompted by confidence in the consensus decision of a specialized epilepsy team, decisions to proceed with surgery were often made in advance of meeting the neurosurgeon. Signing the consent itself was viewed mostly as a necessary formality but, meeting the surgeon and associated perceptions that they were in the hands of an experienced epilepsy surgeon were vital, and confirmed a sense of caring. Detailed recall of the procedure appeared less important to our study participants than the effective communication of trust. With respect to procedural recall, these findings echoed those of a literature review of 13 internationally conducted studies that addressed the consent process across a range of surgical procedures. The review found that recall and understanding of procedural risks and complications was often low, and especially when information was communicated in traditional verbal ways (21). Making accomodations in the consent process for poor baseline recall is especially relevant in TLE since hippocampal pathology implicates the cognitive and emotional networks of memory and decision-making. One individual suggested that receiving a handout of frequently-asked-questions at the end of the visit, would compensate for a compromised memory. Participants actively listened for confirmation from the surgeon that surgery was a correct and safe treatment approach. They also looked for non-verbal signs that the neurosurgeon was confident about the outcome. Active affirmation from family members present during the clinical visit was simultaneously sought.

Overall, two findings stood out in the current study. Firstly, what was remembered with respect to procedural risks and seizure freedom, was often not accurate, yet participants felt satisfactorily informed. Although participants valued hearing percentages, numerical presentations of risks and benefits were not accurately recalled, and the implications of risks, for example, to memory or visual fields were difficult to imagine. Doubt was reserved due to lack of personal experience with brain surgery and the unknown implications of procedural side-effects or complications. These findings were not unusual, and served to emphasize that anticipating how patients may interpret language and understand the implications is integral to the consent process (11). Recall is only one component of comprehension and treatment decisions made by patients are not necessarily logical or rational (9).

Secondly, personal beliefs, subjective perceptions and expectations weighed strongly in how the consent process was experienced and understood. Once participants agreed that seizure control was unlikely to improve with medicines alone, it was easier for them to accept the surgical option as the definitive treatment. Neurologists who were optimistic about surgical outcomes played a crucial role in encouraging participants to move care forward with their care. Even so, time was required to ponder personal and family implications of surgery, especially the risk of dying from the procedure. Rationalizing fear, and ultimately signing the consent was an emotional event that took courage and faith (9). It was also apparent that the clinical team were not privy to the many intimate reflections that occur in people's minds once the formal step of signing has been taken. Contemplating a changed self after surgery was reflected in our data and has been explored as a common concern of neurosurgical patients (29).

Following data collection for the current study, two (11%) participants declined to proceed with surgery. We suggest a future study to explore perceptions among patients who opted not to proceed with surgery despite having signed a consent. Unfortunately, and to underscore the seriousness of epileptogenic mechanisms, there were two incidents of sudden unexpected death from epilepsy (SUDEP) several months after surgery in just this small sample.

Regarding implications for clinical practice, an enlightening comment was made by one participant drawing attention to her perception of a gap in our approach when she said.

All you hear are the risks and, “This is what we're going to do to you. This is your possibility of cure.” It would have been nice if they said, “And this is what life is going to look like afterwards?” The answer I kept getting was, “It'll be individual. We can't tell you what's going to happen after the surgery.” So, it gave me a sense of even they are wondering how I will react. It's going to be an individual thing.

Thus, anticipating how life might look after surgery is crucial to subjective experience and is especially relevant in situations where the goals of surgery are prophylactic vs. curative. A detailed discussion about life post-resection is generally not part of disclosure. Unfortunately discordant expectations are associated with adjustment difficulties that undermine smooth transistions to wellness (30), highlighting the ethical obligations of the interdisciplinary team in the pre- and post-operative periods. The self-image narrative including personal social worlds is integral to decision-making especially after temporal lobe surgery where the post-surgical results may present unpredictable adjustment difficulties (16). Relevant to the study population, we submit that there is a fine line between subjective perceptions that cannot be controlled by the clinical team, and the ability of individuals to process information. Lack of experience with a given treatment circumstance may lead to risks being over- or-understated (9). One way to overcome misperceptions and information gaps is to conceptualize the practice of informed consent as systematic, structured and progressive with three stages, namely, preparation, signing and follow-up after signing. Such an approach allows time for content to be emotionally processed and clarified. Multiple check-points also enable clinicians to closely evaluate expectations especially in the face of underlying memory and cognitive disability.

Strengths and Limitations

This qualitative study fills an important knowledge gap with respect to what the process of informed consent for surgery was like for a sample of patients with drug-resistant TLE. The availability of verbal comprehension scores represents an important strength for a qualitative study that addresses treatment decision-making. However, a study limitation is that the sample was drawn from a single, specialized epilepsy center located in a large US city. Sampling bias may also be reflected as the study participants all had sufficient medical insurance to access specialized care. Although the study illicited in-depth, personal insights for a sample of people with drug-reistant TLE, it may not be possible to generalize the findings to those with extra-temporal epilepsies given potentially different surgical risks.

Conclusions and Future Research

The nuances of the surgical consent serve to calibrate a balanced picture that comprises an exquisitely complex decisional process. While uncontrolled seizures constitute a serious threat to life, and present greater risks than the surgery itself, the method of information delivery should never be coercive. Obtaining an informed consent does not occur at a single point in time, but takes lengthy preparation and counseling, and is a significant human experience in-and-of itself.

Future research that informs consent decisions may help identify better ways to prepare patients for surgery. Additionally, futher study of how best to train the clinical team is warranted and may serve to mitigate the natural hesitation toward elective brain surgery. Such teaching should include how to present inherent trade-offs, and identify what is important to individual patients and families. Establishing a structured, interdisciplinary approach to surgical preparation may address key reasons surgery is underutilized and also support a rehabilitative approach to epilepsy surgery that is accepted as the standard of best practice.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because this is a qualitative study. The data consists of transcripts of the interviews. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to Sandra R. Dewar PhD, APRN, FAES, FAAN; c2Rld2FyJiN4MDAwNDA7bWVkbmV0LnVjbGEuZWR1.

Ethics Statement

Ethical Approval for the study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board at University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) (#18-001356). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

SD and HP jointly conceived and designed the study, analyzed the data, and drafted the initial manuscript. IF performed all informed consents for surgery and contributed to manuscript discussions and revisions.

Funding

This work was supported by UCLA intramural funding (#405230-1A-19900-HP).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Wiebe S, Blume WT, Girvin JP, Eliasziw M. Effectiveness Efficiency of Surgery for Temporal Lobe Epilepsy Study Group. A randomized, controlled trial of surgery for temporal-lobe epilepsy. New England J Med. (2001) 345:311–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200108023450501

2. Engel J, McDermott MP, Wiebe S, Langfitt JT, Stern JM, Dewar S, et al. Early surgical therapy for drug-resistant temporal lobe epilepsy: a randomized trial. J Am Med Assoc. (2012) 307:922–30. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.220

3. Pieters HC, Dewar SR, Ranit L, Iwaki TJ, Engel J. Surgical decision-making among patients with uncontrolled epilepsy: “Making important decisions about my brain, which I happen to love”. Chronic illness. (2020) 2020:1742395320968622. doi: 10.1177/1742395320968622

4. Anderson CT, Noble E, Mani R, Lawler K, Pollard JR. Epilepsy surgery: factors that affect patient decision-making in choosing or deferring a procedure. Epilepsy Res Treat. (2013) 2013:309284. doi: 10.1155/2013/309284

5. Erba G, Messina P, Pupillo E, Beghi E, Group O. Acceptance of epilepsy surgery among adults with epilepsy–what do patients think? Epilepsy & behavior: E&B. (2012) 24:352–8. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2012.04.126

6. Hader WJ, Tellez-Zenteno J, Metcalfe A, Hernandez-Ronquillo L, Wiebe S, Kwon CS, et al. Complications of epilepsy surgery—a systematic review of focal surgical resections and invasive EEG monitoring. Epilepsia. (2013) 54:840–7. doi: 10.1111/epi.12161

7. Engel J. Why is there still doubt to cut it out? Epilepsy currents. (2013) 13:198–204. doi: 10.5698/1535-7597-13.5.198

8. Cloppenborg T, May TW, Blumcke I, Grewe P, Hopf LJ, Kalbhenn T, et al. Trends in epilepsy surgery: stable surgical numbers despite increasing presurgical volumes. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. (2016) 87:1322–9. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2016-313831

9. Merz JF, Fischhoff B. Informed consent does not mean rational consent: cognitive limitations on decision-making. J Leg Med. (1990) 11:321–50. doi: 10.1080/01947649009510831

11. Parkinson R, Eardley I, Reynard J. The meaning of words–closing the gap in understanding between doctors and patients in 21st century consent. BJU Int. (2020) 126:411–5. doi: 10.1111/bju.15167

12. Bernat JL, McQuillen MP. On shared decision-making and informed consent. AAN Enterprises. (2021). doi: 10.1212/CPJ.0000000000000823

13. Lloyd AJ. The extent of patients' understanding of the risk of treatments. Quality Health Care: QHC. (2001) 10:i14–8. doi: 10.1136/qhc.0100014

14. Baxendale S, Thompson P. Red flags in epilepsy surgery: identifying the patients who pay a high cognitive price for an unsuccessful surgical outcome. Epilepsy Behav. (2018) 78:269–72. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2017.08.003

15. Wilson S, Bladin P, Saling M. The “burden of normality”: Concepts of adjustment after surgery for seizures. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. (2001) 70:649–56. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.70.5.649

16. Wilson S, Bladin PF, Saling MM. The burden of normality: a framework for rehabilitation after epilepsy surgery. Epilepsia. (2007) 48:13–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01393.x

17. Dewar SR, Pieters HC. Perceptions of epilepsy surgery: a systematic review and an explanatory model of decision-making. Epilepsy Behavior. (2015) 44:171–8. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2014.12.027

18. Knowlton RC, Kar J, Miller S, Limdi N, Elgavish R, Gilliam FG, et al. Preference-based quality-of-life measures for neocortical epilepsy surgery. Epilepsia. (2011) 52:1018–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2011.03020.x

19. Meneguin S, Aparecido Ayres J. Perception of the informed consent form by participants in clinical trials. Investigación y Educación en Enfermería. (2014) 32:97–102. doi: 10.17533/udea.iee.v32n1a11

20. Agnew J, Jorgensen D. Informed consent: a study of the OR consenting process in New Zealand. AORN J. (2012) 95:763–70. doi: 10.1016/j.aorn.2010.11.039

21. Sherlock A, Brownie S. Patients' recollection and understanding of informed consent: a literature review. ANZ J Surg. (2014) 84:207–10. doi: 10.1111/ans.12555

22. Pope TM. Informed consent requires understanding: complete disclosure is not enough. Am J Bioeth. (2019) 19:27–8. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2019.1587549

23. Wiebe S, Jette N. Epilepsy surgery utilization: who, when, where, and why? Curr Opin Neurol. (2012) 25:187–93. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e328350baa6

24. Engel J. What can we do for people with drug-resistant epilepsy? The 2016 Wartenberg Lecture. Neurology. (2016) 87:2483–9. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003407

26. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. (2006) 3:77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

27. Corbin JM, Strauss A. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. 4th ed Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. (2015).

29. Fried I. Neurosurgery as a window to the human mind: free will and the sense of self. Acta Neurochir (Wien). (2021) 163:1211–2. doi: 10.1007/s00701-021-04749-8

Keywords: decision-making, epilepsy surgery, informed consent, thematic analysis, qualitative research, patient experiences, surgical risks

Citation: Dewar SR, Pieters HC and Fried I (2021) Surgical Decision-Making for Temporal Lobe Epilepsy: Patient Experiences of the Informed Consent Process. Front. Neurol. 12:780306. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2021.780306

Received: 20 September 2021; Accepted: 04 November 2021;

Published: 08 December 2021.

Edited by:

Samuel Wiebe, University of Calgary, CanadaReviewed by:

Meaghan Lunney, University of Calgary, CanadaKhara Sauro, University of Calgary, Canada

Genevieve Rayner, The University of Melbourne, Australia

Copyright © 2021 Dewar, Pieters and Fried. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sandra R. Dewar, c2Rld2FyJiN4MDAwNDA7bWVkbmV0LnVjbGEuZWR1

Sandra R. Dewar

Sandra R. Dewar Huibrie C. Pieters2

Huibrie C. Pieters2 Itzhak Fried

Itzhak Fried