94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

OPINION article

Front. Neurol., 30 July 2021

Sec. Epilepsy

Volume 12 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2021.720073

This article is part of the Research TopicFeeding the Hungry Brain - Ketone Supplementation in Health and DiseaseView all 7 articles

Epilepsy is a neurological disease characterized by seizures, which affects up to 65 million people worldwide (1). About two-thirds of patients with epilepsy are able to achieve seizure control with current antiseizure medication (ASM) (2), whereas one-third of epilepsy patients are difficult to treat, i.e., patients with drug-resistant epilepsy (DRE). In addition, ASM can induce (serious) adverse events and a significant reduction of the quality of life (QoL), leading to ASM retention rates around 50% (3).

DRE can induce neurobiochemical alterations and emotional and physical dysfunctions. The multifaceted status of DRE patients underscores the emphasis on non-pharmacological options, and therapies that target multiple mechanisms are likely to be more effective to treat DRE (4), thereby acting as a “magic shotgun” rather than a “magic bullet.” If epilepsy surgery is not an option in a patient with DRE, vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) (5) or dietary treatments, such as the ketogenic diet (KD), are valuable alternative options (5–7). Initial studies with dietary treatments report on the classical KD, consisting of 80% fat and 20% protein plus carbohydrate (4:1 KD) or 75% fat and 25% protein plus carbohydrate (3:1 KD) (8). A KD using medium-chain triglycerides (MCTs) leads to more ketones/kcal of energy and a more efficient absorption (9). Therefore, the MCT diet is less restrictive since it consists of a lower amount of fat and a higher intake of protein and carbohydrate (10). The modified Atkins diet (MAD) (11) and the low-glycemic index treatment (LGIT) (12) are other dietary therapies mimicking the seizure reduction result of the KD, but they are less restrictive.

Clinical studies show that both modalities (VNS and KD) lead to a seizure frequency reduction (SFR) by at least 50% in half of the DRE patients. A recent study proposed a treatment algorithm for pediatric DRE, including non-pharmacological treatment options such as VNS and the KD (13).

Interestingly, the KD therapy has some advantages in comparison to VNS: the SFR is slightly higher for patients on the KD (14); the KD is non-invasive, and there are few to no neurotoxic effects when compared to multiple ASM (6). Nevertheless, there are barriers and disadvantages in putting the KD into practice, such as palatability issues, compliance issues, side effects (usually mild), variable response rates, and restrictions to the daily life of the patient (15). Overall, a multidisciplinary team (pediatric neurologist, dietician/nutritionist, and a primary care-giver) is indispensable when dietary treatments are initiated and also during maintenance (16).

Currently, we are unable to pinpoint the mechanism(s) of action of the KD, and it is possible that dietary therapies will be classified as “magic shotguns” (17–20). Therefore, our aim was to elaborate on the newest pathways involved, such as the gut microbiome and serine synthesis.

A high-fat low-carbohydrate KD replicates a “fasting state.” Subsequently, this state results in (1) fatty acid oxidation producing ketone bodies (KBs), (2) production of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), (3) decreased activity of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), and (4) inhibition of the mTOR pathway (17, 21).

First, KBs [i.e., β-hydroxybutyrate (BHB), acetone, and acetoacetate] have been considered the key effectors of the antiseizure effects of the KD by modulating neurotransmissions and altering metabolic, inflammatory, and epigenetic pathways, as reviewed elsewhere (17, 22–26). BHB, one of the KBs, can also enhance oxidative brain metabolism, resulting in the production of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) (27), GABAB activation (24), the induction of synaptic recycling of glutamate loaded vesicles (24, 28), activation of KATP (18), activation of two-pore domain potassium channels (K2P) (20), and the decrease of acid-sensing channels (ASICs) (29), thereby dampening neuronal excitability (20). The effects of the KD on neurotransmission have been validated by clinical studies in which patients on the KD therapy were found to have increased GABA levels in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) (20). Second, the KD-induced increase of PUFAs can decrease neuronal excitability as well (16, 17, 23, 25, 30). Third, the decreased glucose availability of the KD leads to a significant reduction of LDH activity, resulting in neuronal hyperpolarization and decreased seizures. These features were proven to be part of the antiseizure mechanism of action of stiripentol (24, 31). Fourth, the KD can inhibit the mTOR pathway, which (1) can affect epileptogenesis (26, 32) and (2) can reduce the hyperactivation that has been implicated in patients with tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC), cortical developmental malformations, and DRE (33).

Besides replicating a “fasting state,” resulting in production of various effectors, the antiseizure mechanisms of the KD are also thought to result in anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activity, as reviewed by Koh et al. (15). The nutritionally regulated transcription factor peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma, PPARγ, regulates genes involved in anti-inflammatory and antioxidant pathways. The findings of Simeone et al. indeed implicate brain PPARγ2 among the mechanisms by which the KD reduces seizures (34). More specifically, Knowles et al. found that in vivo treatment of rats with a KD increased hippocampal catalase mRNA and protein and that this upregulation required PPARγ2 (35). Hence, it seems that the KD regulates catalase expression through PPARγ2 activation and that catalase may contribute to the antiseizure efficacy of the KD.

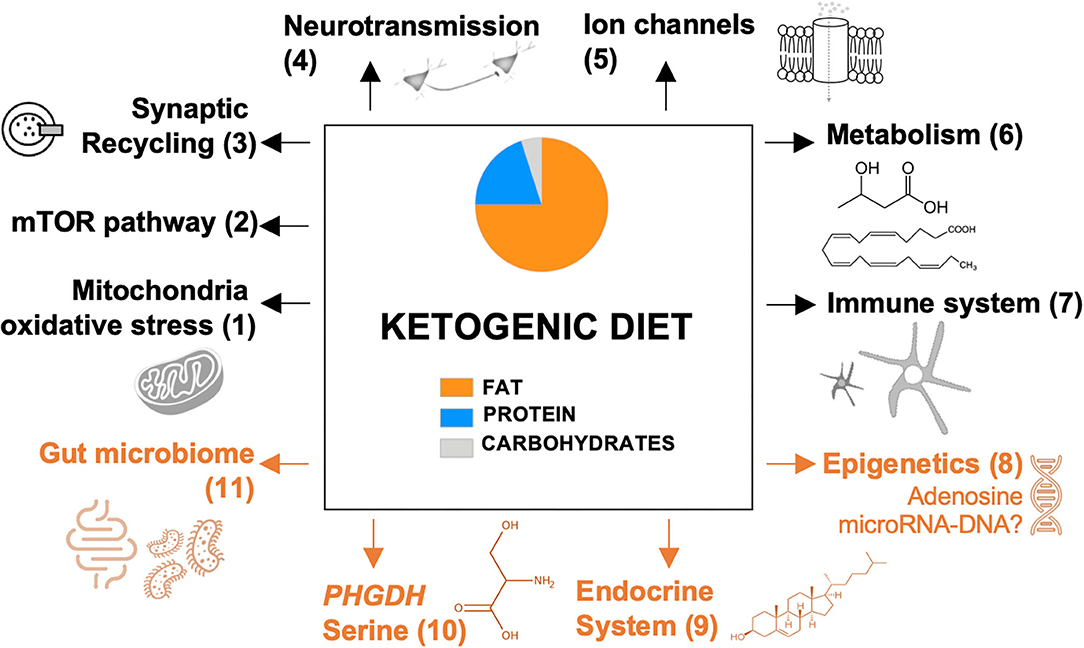

In Figure 1, we provide an overview of ancillary mechanisms of action of the KD. These include KD-induced alterations of the endocrine system, gut microbiome, epigenetic mechanisms, and expression of phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase (PHGDH), the first and rate-limiting enzyme of the de novo serine biosynthesis pathway. Hence, it seems that multiple mechanisms can be induced by the KD and that these might not be mutually exclusive.

Figure 1. Proposed mechanisms of the ketogenic diet. Previously reported pathways are presented in black; recently discovered and novel pathways are presented in orange. Each pathway is numbered, which refers to the reviewing literature focusing on this specific pathway: (1) Gavrilovici and Rho (23); (2) Danial et al. (26); (3) D'Andrea Meira et al. (24); (4) Gavrilovici and Rho (23); (5) Rho (25); (6) Boison (17) and Gavrilovici and Rho (23); (7) Koh et al. (15); (8-11) this review. mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; PHGDH, phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase.

The KD therapy can significantly increase the production of certain neurohormones, such as leptin and cortisol (36, 37). First, leptin receptors are found throughout the brain, and their stimulation leads to antiseizure effects by decreasing pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-1β), increasing an endogenous anticonvulsant (galanin), and acting as an antioxidant by increasing glutathione and decreasing malondialdehyde (37–39). Second, ghrelin, neuropeptide Y, galanin, and cortisol can induce alterations in GABA uptake and serotonin turnover and affect ion channels, thereby decreasing neuronal excitability, although the exact mechanisms need to be explored by future research (20, 40). Third, cortisol is part of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) or stress axis, and targeting this axis can decrease seizures and stress-related comorbidities, e.g., anxiety and depression (41). Consequently, the KD can have beneficial effects in patients with other neurological diseases, diabetes, obesity, reproductive disorders, and other endocrine diseases (42, 43).

The KD was found to target epigenetic mechanisms in several rat models of epilepsy, potentially by increasing adenosine (17, 44) that alters DNA methylation and thereby the expression of genes involved in epileptogenesis, such as the purine ribonucleoside adenosine that functions as a homeostatic regulator of DNA methylation (45). This latter study also correlated the epigenetic mechanisms to the antiseizure activities. In addition, pre-clinical data show that the glucose analog 2-deoxy-D-glucose (2-DG) that inhibits glycolysis and thereby mimics the KD decreases the expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and the principal receptor, TrkB, an important repressor of neuronal genes via NRSF (neuron restrictive silencing factor) induction (46). Thus, a biochemical glycolysis interruption leads to downstream modulation of gene transcription and epileptogenesis (47). Finally, it has been suggested that the KD can change the expression of microRNAs (e.g., mRNA expression decrease of inflammatory interleukines such as IL-1β and IL-6) (15) and of multiple brain genes such as an upregulation of GABA type A receptor subunit alpha 1 (gabra1) (20). However, the evidence is currently not strong enough to unequivocally link the expression of these genes with the observed antiseizure effects.

The study of Newell et al. is the first study to show that the KD affects the gut microbiome (48). The KD therapy inevitably reduces carbohydrate intake and thereby reduces Faecalibacterium, Blautia bacteria, Bifidobacterium, and Eubacterium rectale. The first two bacteria induce fermentation (49) and an elevation of GABA in the hippocampus (50). The latter two bacteria also affect acetate and lactate levels and are involved in regulating the pH and pathogen growth (51). Hence, it seems that specific bacteria can modulate the production of inhibitory neurotransmitters like GABA, possibly by increasing ketogenic gamma-glutamylated amino acids that are substrates for GABA synthesis, which was found to be correlated to the antiseizure effects (52).

Olson et al. were the first to demonstrate that the antiseizure effects of the KD were induced by enrichment of Akkermansia muciniphila and Parabacteroides populations in the gut microbiome in two distinct murine models of different epilepsy types. Furthermore, transplantation of the KD gut microbiota and suppletion of Akkermansia muciniphila and Parabacteroides decreased seizure frequencies even in mice on a normal diet (50).

Clinical data also show that the KD influences gut microbiota composition in children with DRE, resulting in increased levels of Bacteroidetes (53, 54) and proteobacteria (51). However, these studies were not able to elucidate how microbiome alterations correlate to the antiseizure effect of the KD.

To unravel the correlation between the human gut microbiome and neurological diseases including epilepsy, metagenomics holds great potential (55). Understanding how diet can manipulate seizures may suggest novel therapies. In this respect, probiotics could constitute an alternative therapy as suggested by small clinical studies (56).

The KD has recently been shown to induce the expression of genes involved in the serine synthesis, such as PHGDH, in the liver and cerebral cortex of mice (57). The low content of proteins in the KD can result in amino acid stress and thereby induce serine (amino acid) synthesis as a feedback mechanism. In addition, the low amount of glucose of the KD reduces the content of glycolytic intermediate 3-phosphoglycerate (3-PG), which is a substrate of serine synthesis. Henceforth, these two compensating mechanisms can induce the expression of serine synthesis genes, including PHGDH (57) (Supplementary Figure 1).

To date, there are several findings underlining the antiseizure effects of PHGDH activation. First, PHGDH activity is linked with normal brain function. L-serine (synthesized via PHGDH) is a key rate-limiting factor for maintaining steady-state levels of D-serine in the adult brain (58). Hence, L-serine availability in mature neuronal circuits determines the rate of D-serine synthesis in the forebrain and controls N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor function at least in the hippocampus (59). Second, PHGDH malfunctioning/deficiency is associated with DRE (60), and mice with reduced PHGDH expression, induced by a high-lard-content diet resulting in fatty liver disease, have a severe pre-disposition for development of seizures, more specifically increased seizure episodes and decreased seizure thresholds (61). Third, PHGDH activity is linked to anti-inflammatory action. PHGDH has been identified as a key enzyme for steering macrophage polarization toward an anti-inflammatory M2 state (62). Hence, increasing the expression of PHGDH by the KD might additionally polarize microglia toward anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype, thereby resulting in neuroprotection. Interestingly, the gut microbiome plays a crucial role in serine synthesis (63), thereby increasing serine levels in the brain (60, 64). Thus, the KD likely activates PHGDH, which can be linked to the induction of several neuroprotective and antiseizure effects.

The treatment of a complex disease such as epilepsy warrants novel treatment approaches, even in an era of ample available ASM (65). Almost 20 years ago, treatments were developed targeting one specific receptor or mechanism (66). In the last decade, however, focus has been directed toward the development of epilepsy treatments based on multiple mechanisms instead of one (4).

The KD is such a therapy modulating various distinct pathways as underlined by a plethora of pre-clinical data (15, 17–20, 24, 56, 67–70). Clinical data are rather scarce; for example, concentrations of ketone bodies in the blood (71), GABA levels in the CSF (20), and Bacteroidetes and proteobacteria in the gut (51, 53, 54) have been related to the KD therapy. Hence, future studies should investigate if and how certain pathways can be clinically proven to be impacted by the KD.

Even though different mechanisms of the KD have been reviewed the last few years (15, 17, 18, 20, 56) (i.e., focusing on the primary antiseizure mechanisms), we have compiled a comprehensive overview of the ancillary pathways that are affected by the KD and discussed their pre-clinical and clinical evidence in epilepsy treatment. These include KD-induced changes of the endocrine system, epigenetic control, the gut microbiome, and the serine synthesis via PHGDH. Overall, this review and future studies will contribute to the identification of specific pathways of the KD.

JS: conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing (original draft and review and editing), and visualization. KT: conceptualization, writing (review and editing), and supervision. LL: conceptualization, investigation, writing (review and editing), and supervision. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

LL received grants and is a consultant and/or speaker for Zogenix; LivaNova, UCB, Shire, Eisai, Novartis, Takeda/Ovid, NEL, and Epihunter. KT acknowledges receipt of a mandate of IOF, KU Leuven (IOFm/05/022).

The remaining author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2021.720073/full#supplementary-material

1. Singh A, Trevick S. The epidemiology of global epilepsy. Neurol Clin. (2016) 34:837–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2016.06.015

2. Loscher W, Klitgaard H, Twyman RE, Schmidt D. New avenues for anti-epileptic drug discovery and development. Nat Rev Drug Discov. (2013) 12:757–76. doi: 10.1038/nrd4126

3. Schmidt D. Drug treatment of epilepsy: options and limitations. Epilepsy Behav. (2009) 15:56–65. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2009.02.030

4. Cardamone L, Salzberg MR, O'Brien TJ, Jones NC. Antidepressant therapy in epilepsy: can treating the comorbidities affect the underlying disorder? Br J Pharmacol. (2013) 168:1531–54. doi: 10.1111/bph.12052

5. Sourbron J, Klinkenberg S, Kessels A, Schelhaas HJ, Lagae L, Majoie M. Vagus nerve stimulation in children: a focus on intellectual disability. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. (2017) 21:427–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2017.01.011

6. Martin K, Jackson CF, Levy RG, Cooper PN. Ketogenic diet and other dietary treatments for epilepsy. Cochrane database Syst Rev. (2016) 2:CD001903. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001903.pub3

7. Armeno M, Caraballo R. The evolving indications of KD therapy. Epilepsy Res. (2020) 163:106340. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2020.106340

8. Vining EP. Clinical efficacy of the ketogenic diet. Epilepsy Res. (1999) 37:181–90. doi: 10.1016/S0920-1211(99)00070-4

9. Liu YC. Medium-chain triglyceride (MCT) ketogenic therapy. Epilepsia. (2008) 49(Suppl. 8):33–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01830.x

10. Huttenlocher PR, Wilbourn AJ, Signore JM. Medium-chain triglycerides as a therapy for intractable childhood epilepsy. Neurology. (1971) 21:1097–103. doi: 10.1212/WNL.21.11.1097

11. El-Rashidy OF, Nassar MF, Abdel-Hamid IA. Modified Atkins diet vs. classic ketogenic formula in intractable epilepsy. Acta Neurol Scand. (2013) 128:402–8. doi: 10.1111/ane.12137

12. Miranda MJ, Turner Z, Magrath G. Alternative diets to the classical ketogenic diet–can we be more liberal? Epilepsy Res. (2012) 100:278–85. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2012.06.007

13. Sondhi V, Sharma S. Non-pharmacological and non-surgical treatment of refractory childhood epilepsy. Indian J Pediatr. (2020) 87:1062–9. doi: 10.1007/s12098-019-03164-3

14. Wilmshurst JM, Gaillard WD, Vinayan KP, Tsuchida TN, Plouin P, Van Bogaert P, et al. Summary of recommendations for the management of infantile seizures: task force report for the ILAE commission of pediatrics. Epilepsia. (2015) 56:1185–97. doi: 10.1111/epi.13057

15. Koh S, Dupuis N, Auvin S. Ketogenic diet and neuroinflammation. Epilepsy Res. (2020) 167:106454. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2020.106454

16. Goswami JN, Sharma S. Current perspectives on the role of the ketogenic diet in epilepsy management. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. (2019) 15:3273–85. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S201862

17. Boison D. New insights into the mechanisms of the ketogenic diet. Curr Opin Neurol. (2017) 30:187–92. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0000000000000432

18. Simeone TA, Simeone KA, Stafstrom CE, Rho JM. Do ketone bodies mediate the anti-seizure effects of the ketogenic diet? Neuropharmacology. (2018) 133:233–41. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2018.01.011

19. Li R-J, Liu Y, Liu H-Q, Li J. Ketogenic diets and protective mechanisms in epilepsy, metabolic disorders, cancer, neuronal loss, and muscle and nerve degeneration. J Food Biochem. (2020) 44:e13140. doi: 10.1111/jfbc.13140

20. Rudy L, Carmen R, Daniel R, Artemio R, Moisés R-O. Anticonvulsant mechanisms of the ketogenic diet and caloric restriction. Epilepsy Res. (2020) 168:106499. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2020.106499

21. Ricci A, Idzikowski MA, Soares CN, Brietzke E. Exploring the mechanisms of action of the antidepressant effect of the ketogenic diet. Rev Neurosci. (2020) 31:637–48. doi: 10.1515/revneuro-2019-0073

22. Murugan M, Boison D. Ketogenic diet, neuroprotection, and antiepileptogenesis. Epilepsy Res. (2020) 167:106444. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2020.106444

23. Gavrilovici C, Rho JM. Metabolic epilepsies amenable to ketogenic therapies: indications, contraindications, and underlying mechanisms. J Inherit Metab Dis. (2021) 44:42–53. doi: 10.1002/jimd.12283

24. D'Andrea Meira I, Romão TT, Pires do Prado HJ, Krüger LT, Pires MEP, da Conceição PO. Ketogenic diet and epilepsy: what we know so far. Front Neurosci. (2019) 13:5. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2019.00005

25. Rho JM. How does the ketogenic diet induce anti-seizure effects? Neurosci Lett. (2017) 637:4–10. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2015.07.034

26. Danial NN, Hartman AL, Stafstrom CE, Thio LL. How does the ketogenic diet work? Four potential mechanisms. J Child Neurol. (2013) 28:1027–33. doi: 10.1177/0883073813487598

27. Zhang Y, Zhang S, Marin-Valencia I, Puchowicz MA. Decreased carbon shunting from glucose toward oxidative metabolism in diet-induced ketotic rat brain. J Neurochem. (2015) 132:301–12. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12965

28. Hrynevich SV, Waseem TV, Hébert A, Pellerin L, Fedorovich SV. β-Hydroxybutyrate supports synaptic vesicle cycling but reduces endocytosis and exocytosis in rat brain synaptosomes. Neurochem Int. (2016) 93:73–81. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2015.12.014

29. Zhu F, Shan W, Xu Q, Guo A, Wu J, Wang Q. Ketone bodies inhibit the opening of acid-sensing ion channels (ASICs) in rat hippocampal excitatory neurons in vitro. Front Neurol. (2019) 10:155. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2019.00155

30. Hung T-Y, Chu F-L, Wu DC, Wu S-N, Huang C-W. The protective role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma in seizure and neuronal excitotoxicity. Mol Neurobiol. (2019) 56:5497–506. doi: 10.1007/s12035-018-1457-2

31. Sada N, Lee S, Katsu T, Otsuki T, Inoue T. Epilepsy treatment. Targeting LDH enzymes with a stiripentol analog to treat epilepsy. Science. (2015) 347:1362–7. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa1299

32. McDaniel SS, Rensing NR, Thio LL, Yamada KA, Wong M. The ketogenic diet inhibits the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway. Epilepsia. (2011) 52:e7–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2011.02981.x

33. Griffith JL, Wong M. The mTOR pathway in treatment of epilepsy: a clinical update. Future Neurol. (2018) 13:49–58. doi: 10.2217/fnl-2018-0001

34. Simeone TA, Matthews SA, Samson KK, Simeone KA. Regulation of brain PPARgamma2 contributes to ketogenic diet anti-seizure efficacy. Exp Neurol. (2017) 287:54–64. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2016.08.006

35. Knowles S, Budney S, Deodhar M, Matthews SA, Simeone KA, Simeone TA. Ketogenic diet regulates the antioxidant catalase via the transcription factor PPARγ2. Epilepsy Res. (2018) 147:71–4. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2018.09.009

36. Tauseef A, Asghar MS, Zafar M, Lateef N, Thirumalareddy J. Sodium-glucose linked transporter inhibitors as a cause of euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis on a background of starvation. Cureus. (2020) 12:e10078. doi: 10.7759/cureus.10078

37. Thio LL. Hypothalamic hormones and metabolism. Epilepsy Res. (2012) 100:245–51. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2011.07.009

38. Oztas B, Sahin D, Kir H, Kuskay S, Ates N. Effects of leptin, ghrelin and neuropeptide y on spike-wave discharge activity and certain biochemical parameters in WAG/Rij rats with genetic absence epilepsy. J Neuroimmunol. (2021) 351:577454. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2020.577454

39. Oztas B, Sahin D, Kir H, Eraldemir FC, Musul M, Kuskay S, et al. The effect of leptin, ghrelin, and neuropeptide-Y on serum Tnf-?, Il-1β, Il-6, Fgf-2, galanin levels and oxidative stress in an experimental generalized convulsive seizure model. Neuropeptides. (2017) 61:31–7. doi: 10.1016/j.npep.2016.08.002

40. Mehta V, Ferrie CD, Cross JH, Vadlamani G. Corticosteroids including ACTH for childhood epilepsy other than epileptic spasms. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2015) 6:CD005222. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005222.pub3

41. Basu T, Maguire J, Salpekar JA. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis targets for the treatment of epilepsy. Neurosci Lett. (2021) 746:135618. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2020.135618

42. Gupta L, Khandelwal D, Kalra S, Gupta P, Dutta D, Aggarwal S. Ketogenic diet in endocrine disorders: current perspectives. J Postgrad Med. (2017) 63:242–51. doi: 10.4103/jpgm.JPGM_16_17

43. Kuchkuntla AR, Shah M, Velapati S, Gershuni VM, Rajjo T, Nanda S, et al. Ketogenic diet: an endocrinologist perspective. Curr Nutr Rep. (2019) 8:402–10. doi: 10.1007/s13668-019-00297-x

44. Lusardi TA, Akula KK, Coffman SQ, Ruskin DN, Masino SA, Boison D. Ketogenic diet prevents epileptogenesis and disease progression in adult mice and rats. Neuropharmacology. (2015) 99:500–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2015.08.007

45. Williams-Karnesky RL, Sandau US, Lusardi TA, Lytle NK, Farrell JM, Pritchard EM, et al. Epigenetic changes induced by adenosine augmentation therapy prevent epileptogenesis. J Clin Invest. (2013) 123:3552–63. doi: 10.1172/JCI65636

46. Singh-Taylor A, Molet J, Jiang S, Korosi A, Bolton JL, Noam Y, et al. NRSF-dependent epigenetic mechanisms contribute to programming of stress-sensitive neurons by neonatal experience, promoting resilience. Mol Psychiatry. (2018) 23:648–57. doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.240

47. Masino SA, Rho JM. Mechanisms of ketogenic diet action. In: Noebels JL, Avoli M, Rogawski MA, Olsen RW, Delgado-Escueta AV, editors. Jasper's Basic Mechanisms of the Epilepsies [Internet]. 4th ed. Bethesda, MD: National Center for Biotechnology Information (US) (2012).

48. Newell C, Bomhof MR, Reimer RA, Hittel DS, Rho JM, Shearer J. Ketogenic diet modifies the gut microbiota in a murine model of autism spectrum disorder. Mol Autism. (2016) 7:37. doi: 10.1186/s13229-016-0099-3

49. Paoli A, Mancin L, Bianco A, Thomas E, Mota JF, Piccini F. Ketogenic diet and microbiota: friends or enemies? Genes (Basel). (2019) 10:534. doi: 10.3390/genes10070534

50. Olson CA, Vuong HE, Yano JM, Liang QY, Nusbaum DJ, Hsiao EY. The gut microbiota mediates the anti-seizure effects of the ketogenic diet. Cell. (2018) 174:497. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.06.051

51. Lindefeldt M, Eng A, Darban H, Bjerkner A, Zetterström CK, Allander T, et al. The ketogenic diet influences taxonomic and functional composition of the gut microbiota in children with severe epilepsy. NPJ Biofilms Microb. (2019) 5:5. doi: 10.1038/s41522-018-0073-2

52. Chatzikonstantinou S, Gioula G, Kimiskidis VK, McKenna J, Mavroudis I, Kazis D. The gut microbiome in drug-resistant epilepsy. Epilepsia Open. (2021) 6:28–37. doi: 10.1002/epi4.12461

53. Xie G, Zhou Q, Qiu C-Z, Dai WK, Wang HP, Li YH, et al. Ketogenic diet poses a significant effect on imbalanced gut microbiota in infants with refractory epilepsy. World J Gastroenterol. (2017) 23:6164–71. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i33.6164

54. Zhang Y, Zhou S, Zhou Y, Yu L, Zhang L, Wang Y. Altered gut microbiome composition in children with refractory epilepsy after ketogenic diet. Epilepsy Res. (2018) 145:163–8. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2018.06.015

55. Sourbron J, Klinkenberg S, van Kuijk SMJ, Lagae L, Lambrechts D, Braakman HMH, et al. Ketogenic diet for the treatment of pediatric epilepsy: review and meta-analysis. Childs Nerv Syst. (2020) 36:1099–109. doi: 10.1007/s00381-020-04578-7

56. Holmes M, Flaminio Z, Vardhan M, Xu F, Li X, Devinsky O, et al. Cross talk between drug-resistant epilepsy and the gut microbiome. Epilepsia. (2020) 61:2619–28. doi: 10.1111/epi.16744

57. Vazquez A. Dietary and pharmacological induction of serine synthesis genes. bioRxiv [Preprint]. (2020). doi: 10.1101/2020.06.15.151860

58. Yang JH, Wada A, Yoshida K, Miyoshi Y, Sayano T, Esaki K, et al. Brain-specific Phgdh deletion reveals a pivotal role for L-serine biosynthesis in controlling the level of D-serine, an N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor co-agonist, in adult brain. J Biol Chem. (2010) 285:41380–90. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.187443

59. Kim JH, Jang BG, Choi BY, Kwon LM, Sohn M, Song HK, et al. Zinc chelation reduces hippocampal neurogenesis after pilocarpine-induced seizure. PLoS ONE. (2012) 7:e48543. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048543

60. Tabatabaie L, Klomp LWJ, Rubio-Gozalbo ME, Spaapen LJM, Haagen AAM, Dorland L, et al. Expanding the clinical spectrum of 3-phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase deficiency. J Inherit Metab Dis. (2011) 34:181–4. doi: 10.1007/s10545-010-9249-5

61. Sim W-C, Lee W, Sim H, Lee K-Y, Jung S-H, Choi Y-J, et al. Downregulation of PHGDH expression and hepatic serine level contribute to the development of fatty liver disease. Metabolism. (2020) 102:154000. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2019.154000

62. Wilson JL, Nägele T, Linke M, Demel F, Fritsch SD, Mayr HK, et al. Inverse data-driven modeling and multiomics analysis reveals Phgdh as a metabolic checkpoint of macrophage polarization and proliferation. Cell Rep. (2020) 30:1542–52.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.01.011

63. Rudzki L, Stone TW, Maes M, Misiak B, Samochowiec J, Szulc A. Gut microbiota-derived vitamins - underrated powers of a multipotent ally in psychiatric health and disease. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. (2021) 107:110240. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.110240

64. Tabatabaie L, Klomp LW, Berger R, de Koning TJ. L-serine synthesis in the central nervous system: a review on serine deficiency disorders. Mol Genet Metab. (2010) 99:256–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2009.10.012

65. Zarnowska IM. Therapeutic use of the ketogenic diet in refractory epilepsy: what we know and what still needs to be learned. Nutrients. (2020) 12:2616. doi: 10.3390/nu12092616

66. Roth BL, Sheffler DJ, Kroeze WK. Magic shotguns versus magic bullets: selectively non-selective drugs for mood disorders and schizophrenia. Nat Rev Drug Discov. (2004) 3:353–9. doi: 10.1038/nrd1346

67. Lyons L, Schoeler NE, Langan D, Cross JH. Use of ketogenic diet therapy in infants with epilepsy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epilepsia. (2020) 61:1261–81. doi: 10.1111/epi.16543

68. Yu N, Liu H, Di Q. Modulation of immunity and the inflammatory response: a new target for treating drug-resistant epilepsy. Curr Neuropharmacol. (2013) 11:114–27. doi: 10.2174/157015913804999540

69. Auvin S. Non-pharmacological medical treatment in pediatric epilepsies. Rev Neurol (Paris). (2016) 172:182–5. doi: 10.1016/j.neurol.2015.12.009

70. Jackson CF, Makin SM, Marson AG, Kerr M. Non-pharmacological interventions for people with epilepsy and intellectual disabilities. Cochrane database Syst Rev. (2015) 9:CD005502. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005502.pub3

Keywords: epilepsy, ketogenic diet, mechanism, endocrine system, epigenetics, gut microbiome, serine synthesis, phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase

Citation: Sourbron J, Thevissen K and Lagae L (2021) The Ketogenic Diet Revisited: Beyond Ketones. Front. Neurol. 12:720073. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2021.720073

Received: 03 June 2021; Accepted: 29 June 2021;

Published: 30 July 2021.

Edited by:

Kette D. Valente, Universidade de São Paulo, BrazilReviewed by:

Katia Lin, Federal University of Santa Catarina, BrazilCopyright © 2021 Sourbron, Thevissen and Lagae. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lieven Lagae, bGlldmVuLmxhZ2FlQHV6bGV1dmVuLmJl

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.