94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Neurol., 19 October 2021

Sec. Epilepsy

Volume 12 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2021.712773

This article is part of the Research TopicTranslational Epilepsy: An Experimental to Clinical UpdateView all 7 articles

Ping Lu1,2†

Ping Lu1,2† Fengpeng Wang3†

Fengpeng Wang3† Shuixiu Zhou4†

Shuixiu Zhou4† Xiaohua Huang5

Xiaohua Huang5 Hao Sun1

Hao Sun1 Yun-Wu Zhang1

Yun-Wu Zhang1 Yi Yao3

Yi Yao3 Honghua Zheng1,5,6*

Honghua Zheng1,5,6*CNTNAP2 (coding for protein Caspr2), a member of the neurexin family, plays an important role in the balance of excitatory and inhibitory post-synaptic currents (E/I balance). Here, we describe a novel pathogenic missense mutation in an infant with spontaneous recurrent seizures (SRSs) and intellectual disability. Genetic testing revealed a missense mutation, c.2329 C>G (p. R777G), in the CNTNAP2 gene. To explore the effect of this novel mutation, primary cultured neurons were transfected with wild type homo CNTNAP2 or R777G mutation and the morphology and function of neurons were evaluated. When compared with the vehicle control group or wild type group, the neurites and the membrane currents, including spontaneous excitatory post-synaptic currents (sEPSCs) and inhibitory post-synaptic currents (sIPSCs), in CNTNAP2 R777G mutation group were all decreased or weakened. Moreover, the action potentials (APs) were also impaired in CNTNAP2 R777G group. Therefore, CNTNAP2 R777G may lead to the imbalance of excitatory and inhibitory post-synaptic currents in neural network contributing to SRSs.

In the central nervous system, the neuron network relies on effective signal transmission, especially the neurotransmitter transmission between neuron synapses. The balance between excitatory and inhibitory currents (E/I balance) became a hotspot of nervous system disorders' study in recent years (1–6). The relationship between inhibitory and excitatory synaptic transmission does not always remain stable, which may result in a lot of circuit dysfunctions and diseases, such as epilepsy, depression, anxiety, fragile X syndrome, Rett syndrome, Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), schizophrenia, and so on (7, 8). Additionally, studies suggest that gene alterations may be one of the underlying reasons (9). Gene deletion or mutation can change the excitability of neurons. For example, dysregulation of hippocampal inhibition was observed in Cntnap2−/− mouse, which recapitulates the major features of ASD (10).

CNTNAP2 (coding for protein Caspr2) gene locates in the long arm of the seventh autosomal chromosome (7q35) and encodes a protein named Caspr2 (Contactin-Associated-protein-like-2), which is a neuronal glycoprotein. Caspr2 is a transmembrane protein with a short intracellular fragment and a large extracellular component, which benefits interactions with other proteins, such as CNTN2, TAG-1, Kv1 channel, and protein 4.1B (11–13). CNTNAP2 has been confirmed to be involved in several nervous system diseases including epilepsy, ASD, schizophrenia, language difficulties, and intellectual disability (14–21). Moreover, Caspr2 can cluster with the shaker Kv1.1 and Kv1.2 channels in the near lateral region of the flying junction of the axons with myelin sheath, involved in nerve conduction of myelin sheath axons (11, 22), and the process of neuron migration in mouse cortex (23). In CNTNAP2 knockout mice, it was found that the activity of neural network was reduced, the dendrites were smaller, and the number of excitatory and inhibitory synapses was reduced, all of which may be caused by the effects of CNTNAP2 deficiency on the neuronal synapses and dendrites (24).

Here, we describe a novel pathogenic CNTNAP2 mutation in an 8-month-old infant who manifested spontaneous recurrent seizures (SRS) and intellectual disability. Whole exome sequencing revealed a novel pathogenic mutation, c.2329 C>G (p. R777G), in the CNTNAP2 gene, causing the imbalance of excitatory and inhibitory post-synaptic currents in the neural network and contributing to SRSs.

An 8-month-old male infant had been presenting with infantile spasm since the age of 6 months. The seizure frequency was 2–3 clusters per day. He received standard anti-seizure medications (ASMs), including Valproate 30 mg/kg/d, Topiramate 1 mg/kg/d, and Lamotrigine 1 mg/kg/d. However, none of those treatments were effective. He had intellectual disability. He was unable to roll over or crawl alone. The history of his mother's pregnancy and delivery was normal. One of his collateral brothers suffered autism. We received approval from the Medical Ethics Committee of Fujian Medical University Xiamen Humanity Hospital using human materials (Permitted number HAXM-MEC-202000701-012-01). We also received informed consent for research from the participants or guardians.

Genetic testing was performed using targeted exome sequencing at Fuzhou Kingmed for Clinical Laboratory, China. DNA was extracted from blood of the patient using QIAamp Blood DNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN) and was purified by the magnetic bead method. DNA was subsequently amplified by PCR and connected with the upper joint sequence, captured, and purified by the TruSight one sequencing panel (Illumina Inc, USA). The obtained final DNA libraries were sequenced using a NextSeq500 sequencer (Illumina Inc, USA). Candidate mutations were verified by Sanger sequencing.

The human CNTNAP2 cDNA was obtained from Han's Lab, School of Life Sciences, Xiamen University. Wild type pEGFP-N1-CNTNAP2 plasmid was prepared by inserting coding sequence of the human CNTNAP2 gene into the pEGFP-N1 vector. The CNTNAP2 R777G mutation was obtained by PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis with c.2329 C>G.

According to the widely used protocol pioneered by Beaudoin (25), the primary neurons were isolated from the cortex of post-natal 0–1 day C57BL/6 mice in the Laboratory Animal Center of Xiamen University. All efforts were aimed to lessen animals' suffering. All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the protocols of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Xiamen University (Permitted number XMULAC20170255). After 13–14 days' mixture culture, the primary neurons were, respectively, transfected with plasmid of vehicle, wild type CNTNAP2, or CNTNAP2 R777G mutation by Lipofectamine™ 2000 (Thermo) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were then collected for further assay after 24 h.

For the transfected neuronal immunofluorescence observation, the primary transfected neurons with vehicle, wild type CNTNAP2, or CNTNAP2 R777G mutation plasmid were fixed and captured with a Nikon T-P2 DIGITAL SIGHT microscope (Nikon, Japan). High-power field of at least five neurons per section from three independent experiments were selected for quantifying the number of intersections by Nikon NIS-Elements D 4.00.12 Viewer software. A series of concentric circles with radius increasing at 100 pixel (px) and spanning from 100 to 400 px range were plotted with the number of intersections against distance from the neuron center. The number of neurite intersections (branch) with each circle line along the distance from the neuron center was then manually quantified using a set of 12 neuron images in each group.

Artificial Cerebrospinal Fluid (ACSF): 120 mM sucrose, 64 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KCl, 1.25 mM NaH2PO4, 26 mM NaHCO3, 10 mM d-glucose, 10 mM MgSO4, 0.5 mM CaCl2, pH 7.4, 290 mOsm.

Pipette Solution for recording spontaneous excitatory post-synaptic currents (sEPSCs) and spontaneous inhibitory post-synaptic currents (sIPSCs): 140 mM CsCH3SO3, 2 mM MgCl2 6H2O, 5 mM TEA-Cl, 10 mM HEPES, 1 mM EGTA, 2.5 mM Mg-ATP, 0.3 mM Na-GTP, pH 7.4, 290 mOsm. The solution was filtered by 0.22 μm filter membrane after preparation in case the pipette was plugged.

Pipette Solution for recording action potentials (APs): 140 mM K+ gluconate, 4 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM CaCl2, 10 mM HEPES, 1.1 mM EGTA, 0.3 mM Na2-GTP, 2 mM Mg-ATP, pH 7.4, 290 mOsm. The solution was filtered by 0.22 μm filter membrane after preparation in case the pipette was blocked up during whole-cell patch recording.

Cortical neurons were recorded in whole-cell configuration 24 h after transfection. The extracellular solution was ACSF as described previously (26). Patch pipettes were pulled from borosilicate glass and fire-polished to a resistance of 3–5 MΩ. After pouring with pipette solution, neurons were voltage clamped at −70 mV for sEPSCs recording or at −0 mV for sIPSCs. Currents were recorded using pCLAMP 10.3 software with an Axopatch 700B amplifier (Molecular Devices: Axon CNS, MultiClamp 700B, Digidata 1440A, USA). To detect the events of post-synaptic currents, we set threshold of sEPSCs at 5 pA and sIPSCs at 10 pA, respectively. All the events were estimated as the 10%−90% rising time and decay time (ms). Recordings were filtered at 5 kHz and digitized at 20 kHz. The data were low-pass filtered using a 1 kHz cutoff and analyzed with Mini-Analysis 6.0.3 software (Synaptosoft, USA).

Quantitative electrical stimulations were applied to induce the neuronal APs. The input current increased by 10 pA in a stepwise manner. The amount of induced APs in different groups was recorded accordingly. The resting membrane potentials varied from −70 to −75 mV in this experiment. We set −70 mv as holding potential for recording sEPSC and −10 mv for sIPSC. The access resistance was also monitored during the experiment. The access resistance was usually 10–20 MΩ. If the access resistance was <10 MΩ or more than 20 MΩ, the data were excluded in our experiment.

All data were represented as mean ± standard error of mean (SEM). Statistical significance was determined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and by Bonferroni's post-hoc test by GraphPad Prism 6.0 statistical software. p< 0.05 was considered significant.

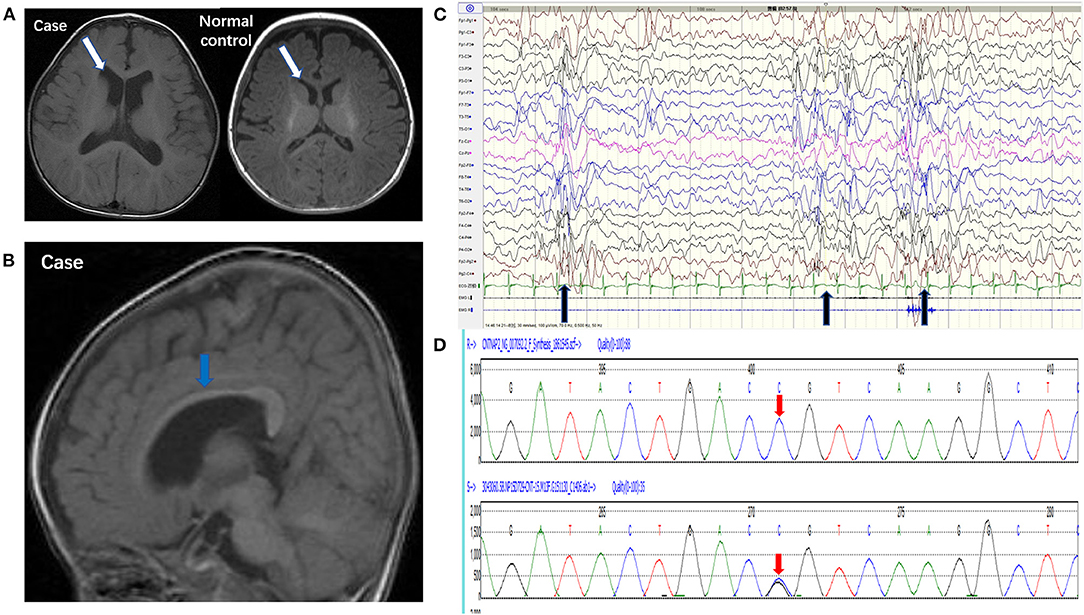

Brain MRI showed that the bilateral ventricular system was mildly enlarged (Figure 1A) and the corpus callosum was dysplastic (Figure 1B). Long-term EEG showed hypsarrhythmia background and frequently multifocal epileptic discharges (Figure 1C). Whole exome sequencing revealed a novel point mutation c.2329 C>G (p. R777G) in the CNTNAP2 gene (Figure 1D).

Figure 1. Pedigrees of the case carrying a CNTNAP2 R777G mutation. (A) 3.0T MRI (axial T1) of the patient (left) and normal control (right) showed mild enlargement of ventricle (white arrow). (B) 3.0T MRI (sagittal T1) showed corpus callosum dysplasia (blue arrow). (C) EEG showed intermittent hypsarrhythmia and superimposed with epileptic discharges at bilateral parieto-occipital area (black arrow). (D) CNTNAP2 DNA from peripheral blood leucocytes of the patient was analyzed by Sanger sequencing (the upper red arrow indicates normal base sequence and the lower red arrow indicates the c.2329 C>G mutation).

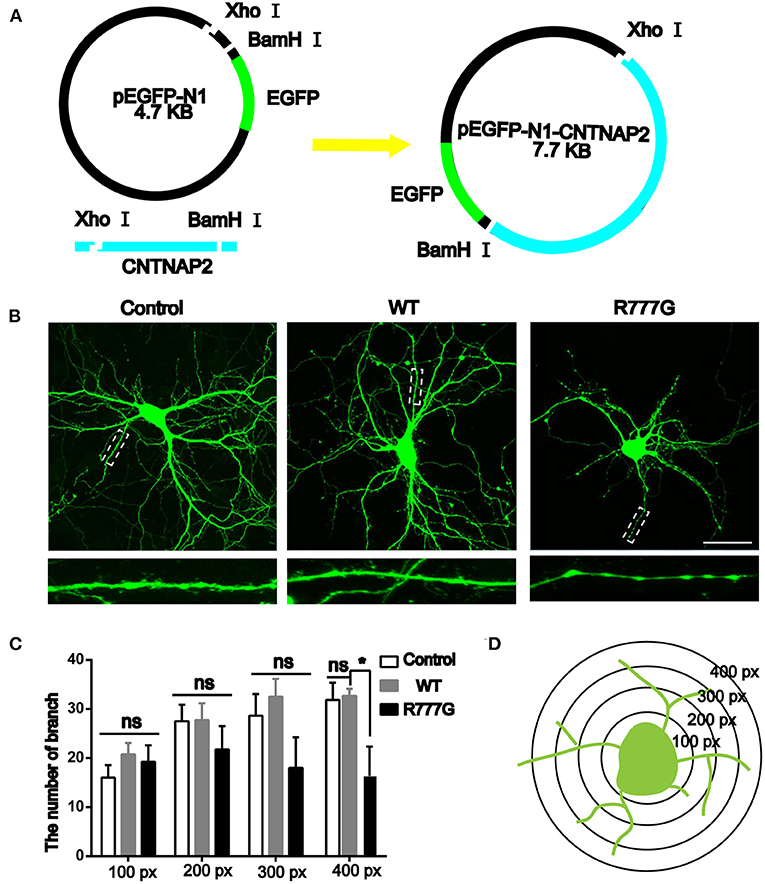

Caspr2 is an adhesion molecule required for the formation of axoglial paranodal junctions surrounding the nodes of Ranvier (27). Therefore, it is probable that this novel mutation affects the function of Caspr2. To determine this, wild type pEGFP-N1-CNTNAP2 or CNTNAP2 R777G mutation plasmid was prepared (indicated in Figure 2A). Then, we overexpressed CNTNAP2 R777G at a level comparable to that of wild type Caspr2 in primary cultured neurons. We found that the number of neurites in CNTNAP2 R777G group was decreased when compared with wild type (WT) group (Figure 2B). The dendrite branches were also reduced with an increasing distance from neuron soma, and the mutation neuron dendrites were sparse, especially distal dendrites (Figure 2C). Figure 2D indicated the schematic diagram of neurite intersections. These results indicate that CNTNAP2 R777G decreases the neurite extension.

Figure 2. Effects of CNTNAP2 R777G on the morphological change of primary cultured neurons. (A) Schematic diagram of the pEGFP-N1-CNTNAP2 plasmid, which can express GFP and Caspr2 simultaneously. (B) Representative fluorescent images of primary cultured neurons transfected with vehicle, wild type or CNTNAP2 R777G plasmid, respectively. The enlarged images below are magnified views of the dotted square regions. (C) The number of neurites intersections in each circle was counted to obtain a statistical diagram of the number of dendrites of primary cultured neurons in different groups, with the radius of 100, 200, 300, and 400 px, respectively. (D) Schematic diagram of neurites intersections. Scale bar: 100 μm. ANOVA and Bonferroni's post-hoc test, *p < 0.05, ns, not significant.

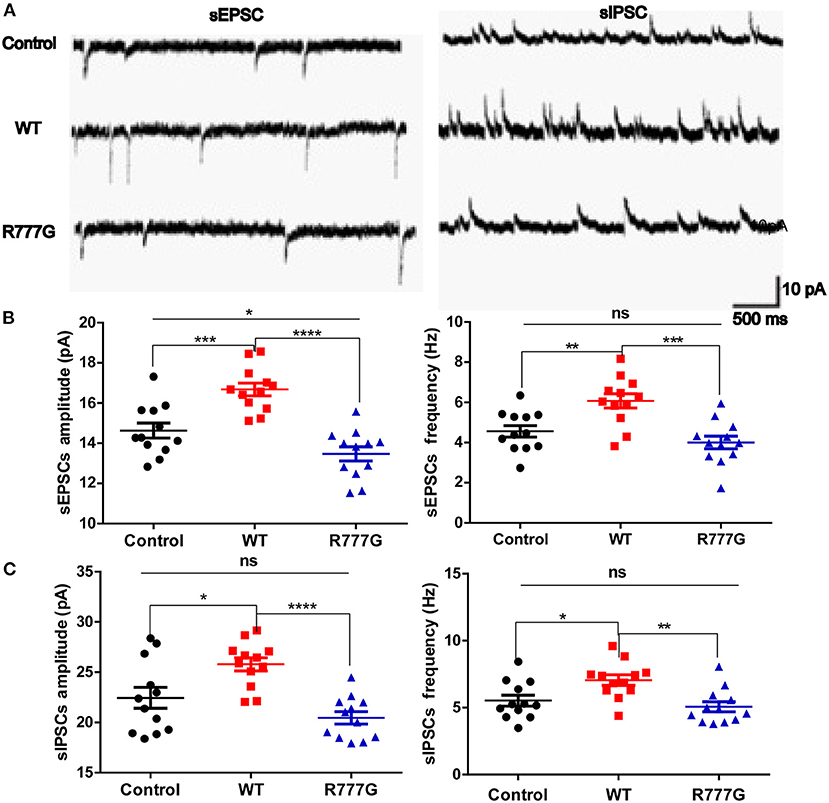

Given that loss of Caspr2 contributed to the aggregates of cytoplasmic glutamate receptor (28, 29), we wondered whether the neuronal excitability was disrupted by CNTNAP2 R777G mutation. We then employed primary cultured neurons with the whole cell patch to analyse the excitability of cells. We variably clamped the membrane potential to differentially record sEPSCs and sIPSCs, which are rough methods of measuring neuron excitability (30, 31). We found that both the amplitude and frequency of sEPSCs in CNTNAP2 WT group were increased whereas CNTNAP2 R777G group showed lower amplitude of sEPSCs when compared with control group (Figures 3A,B), suggesting the important role of Caspr2 in neural excitatory activity. One study reported that loss of Caspr2 would increase post-synaptic excitatory responses (32). In contrast, the novel R777G mutation might negate the function of Caspr2 and compromise its physiological function. However, the amplitude and frequency of sIPSC in Caspr2 WT group also increased compared with control group (Figure 3C). These results might be explained as a compensatory change in CNTNAP2 WT group in response to the increased excitability of neurons. Therefore, these results indicate that CNTNAP2 R777G lost the function of maintaining the normal E/I balance.

Figure 3. CNTNAP2 R777G affects the post-synaptic currents of neurons. (A) The trace of sEPSCs or sIPSCs. (B) The amplitude and frequency of sEPSC in different groups. (C) The amplitude and frequency of sIPSC in different groups. n = 8 for each group. ANOVA and Bonferroni's post-hoc test, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

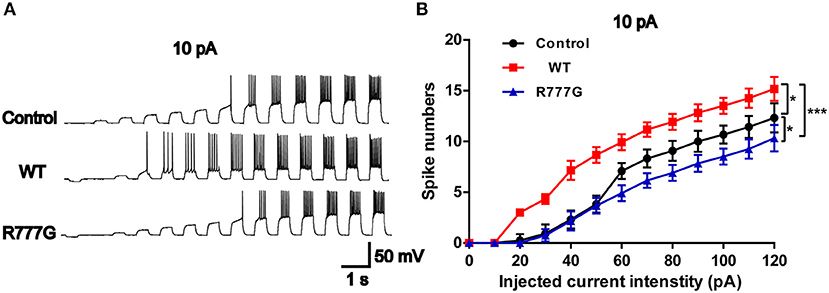

Action potentials is always considered as one of the indicators of neural excitability. All the receptor-mediated sEPSCs and sIPSCs belong to partial synaptic events so that we can evaluate the neural excitability through APs induced by the integration of many synaptic activities (33). Action potentials resulted from transient changes in the permeability of the axon membrane to sodium and potassium ions (34). We recorded neural APs induced by exogenous current and got a cluster of APs when the neurons were stimulated by inputted currents (Figures 4A,B). In the current experimental conditions, the tested neurons exhibited a tonic pattern whereas the phasic pattern of APs was not noted in the tested neurons. As expected, neurons in CNTNAP2 WT group induced more APs than those in other groups, further proving that Caspr2 participate in the formation of neuronal excitation (Figures 4A,B). In addition, APs threshold was detected in three groups, and neurons in CNTNAP2 R777G group showed the highest APs threshold with the fewest number of APs compared with those in other groups (Figures 4A,B). These results suggest that CNTNAP2 R777G mutation impairs the AP of neurons.

Figure 4. CNTNAP2 R777G impairs the action potentials of neurons. (A) The sequential sweeps of APs in different groups evoked with different intensity of injected currents. (B) Evoked action potentials were quantified to compare the neuronal excitability in different groups. n = 4 or 5 for each group. ANOVA and Bonferroni's post-hoc test, *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001.

In this study, we identified a novel pathogenic R777G mutation in CNTNAP2 gene in an atypical infant with SRSs. This CNTNAP2 R777G mutation caused the imbalance of sEPSCs and sIPSCs in the neural network, contributing to SRSs, which was consistent with the literature on CNTNAP2 knockdown experiments. Furthermore, as a susceptible gene of epilepsy, CNTNAP2 mutation or deletion results in the break of E/I balance in neuronal network.

Caspr2 is a member of the axon superfamily that promotes intercellular interactions in the nervous system. Our finding that CNTNAP2 R777G decreases the neurite extension is consistent with other researchers' findings that deletion of Caspr2 resulted in the deficit in dendrite arborization and reduction in the dendritic length and branching of interneuron (35).

Axon and dendrite terminals play key roles in synaptic function in the neural network and the receptor-mediated membrane currents are indicators of neuronal excitability. GABAergic synapses reside on dendritic shafts, soma, and axon initial segments in the formation of predecessor axon-dendrite contacts (36). On the contrary, glutamatergic synapses form almost exclusively on dendritic spines (37). Some researchers also observed that depletion of Caspr2 in neurons decreased synaptic strength in a cell-autonomous fashion, impaired terminal dendrites and spine development, and suppressed neural network activity (24). Additionally, Caspr2 plays an important role in the development and activity of normal neuronal network whereas mutation in CNTNAP2 gene can disorganize normal Caspr2 functions.

Researchers recently observed that deletion of Caspr2 resulted in the reduction of the amplitude of α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole propionate receptor (AMPAR) and N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR)-mediated EPSCs and the amplitude of γ-aminobutyric acid type A (GABAA) receptor-mediated IPSCs (24, 38, 39). In other words, the synaptic transmission was reduced in CNTNAP2-deficient neurons. The synaptic transmission of GABAergic interneuron was also decreased in CNTNAP2 knockout mice (23). It is still unclear what the reason for the sEPSCs alterations in CNTNAP2 R777G group is, which may result from abnormal synapses or decreased neurites induced by CNTNAP2 R777G in neurons. Therefore, these results indicate that CNTNAP2 R777G lost the function of maintaining the normal E/I balance. Although Caspr2 was recently reported to be expressed in both excitatory and inhibitory synapses and effects of Caspr2 depletion were found on excitatory and inhibitory currents (38, 39), the specific types of neurons CNTNAP2 R777G affects needs to be further explored.

Given that Caspr2 can cluster with Kv1.1 and Kv1.2 channels involved in the nerve conduction of myelin sheath axons (11, 22), there is a possibility that this result is due to a change in voltage-gated ion channels, such as Kv1.1 or Kv1.2. CNTNAP2 R777G neurons showed the highest APs threshold with the fewest number of APs compared with other groups, which may result in circuit dysfunctions and diseases. However, how this CNTNAP2 R777G mutation contributes to SRSs in vivo remains elusive.

In conclusion, this study provides clinical and experimental data to demonstrate a novel pathogenic R777G mutation in CNTNAP2 gene in an atypical infant with SRSs. Nevertheless, the findings of the present study are limited. Without a large family showing seizure and enough gene samples from family members, it is difficult to demonstrate that CNTNAP2 R777G was fully responsible for this disease. Additionally, the overexpression system in this study is artificial. It is interesting to investigate whether Cntnap2 R777G mutant mouse develops SRSs in future work.

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available due to privacy restrictions. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to the corresponding author.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Medical Ethics Committee of Xiamen University for our experiments using human materials. We also received informed consent for research from the participants or guardians. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardian/next of kin. All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the protocols of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Xiamen University.

HZ conceived and designed the study. PL, FW, and SZ performed the experiments and analyzed the data. PL, FW, and HZ wrote the paper. YY provided the information on the case. XH, HS, and Y-WZ coordinated the study and provided technical assistance. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

This work was supported by grants from the Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province of China (2018D0022 and 2020J01014). This study was also supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81771164, 91949129, 81771377, 81471160, and U1705285).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

We thank Dr. Jiahuai Han for providing the human CNTNAP2 cDNA.

1. Yizhar O, Fenno LE, Prigge M, Schneider F, Davidson TJ, O'shea DJ, et al. Neocortical excitation/inhibition balance in information processing and social dysfunction. Nature. (2011) 477:171–8. doi: 10.1038/nature10360

2. Selimbeyoglu A, Kim CK, Inoue M. Modulation of prefrontal cortex excitation/inhibition balance rescues social behavior in CNTNAP2-deficient mice. (2017). Sci Transl Med. 9:eaah6733. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aah6733

3. Tatti R, Haley MS, Swanson OK, Tselha T, Maffei A. Neurophysiology and regulation of the balance between excitation and inhibition in neocortical circuits. Biol Psychiatry. (2017) 81:821–31. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2016.09.017

4. Ferguson BR, Gao WJ. Thalamic control of cognition and social behavior via regulation of gamma-aminobutyric acidergic signaling and excitation/inhibition balance in the medial prefrontal cortex. Biol Psychiatry. (2018) 83:657–69. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.11.033

5. Sohal VS, Rubenstein JLR. Excitation-inhibition balance as a framework for investigating mechanisms in neuropsychiatric disorders. Mol Psychiatry. (2019) 24:1248–57. doi: 10.1038/s41380-019-0426-0

6. Dong Z, Chen W, Chen C, Wang H, Cui W, Tan Z, et al. CUL3 deficiency causes social deficits and anxiety-like behaviors by impairing excitation-inhibition balance through the promotion of cap-dependent translation. Neuron. (2020) 105 475.e6–90.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.10.035

7. Bartley AF, Dobrunz LE. Short-term plasticity regulates the excitation/inhibition ratio and the temporal window for spike integration in CA1 pyramidal cells. Eur J Neurosci. (2015) 41:1402–15. doi: 10.1111/ejn.12898

8. Foss-Feig JH, Adkinson BD, Ji JL, Yang G, Srihari VH, Mcpartland JC, et al. Searching for cross-diagnostic convergence: neural mechanisms governing excitation and inhibition balance in schizophrenia and autism spectrum disorders. Biol Psychiatry. (2017) 81:848–61. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.03.005

9. Gatto CL, Broadie K. Genetic controls balancing excitatory and inhibitory synaptogenesis in neurodevelopmental disorder models. Front Synaptic Neurosci. (2010) 2:4. doi: 10.3389/fnsyn.2010.00004

10. Jurgensen S, Castillo PE. Selective dysregulation of hippocampal inhibition in the mouse lacking autism candidate gene CNTNAP2. J Neurosci. (2015) 35:14681–7. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1666-15.2015

11. Poliak S, Salomon D, Elhanany H, Sabanay H, Kiernan B, Pevny L, et al. Juxtaparanodal clustering of Shaker-like K+ channels in myelinated axons depends on Caspr2 and TAG-1. J Cell Biol. (2003) 162:1149–60. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200305018

12. Traka M, Goutebroze L, Denisenko N, Bessa M, Nifli A, Havaki S, et al. Association of TAG-1 with Caspr2 is essential for the molecular organization of juxtaparanodal regions of myelinated fibers. J Cell Biol. (2003) 162:1161–72. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200305078

13. Lu Z, Reddy MVVVS, Liu J, Kalichava A, Liu J, Zhang L, et al. Molecular architecture of contactin-associated protein-like 2 (CNTNAP2) and its interaction with contactin 2 (CNTN2). J Biol Chem. (2016) 291:24133–47. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.748236

14. Friedman JI, Vrijenhoek T, Markx S, Janssen IM, Van Der Vliet WA, Faas BH, et al. CNTNAP2 gene dosage variation is associated with schizophrenia and epilepsy. Mol Psychiatry. (2008) 13:261–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002049

15. Whitehouse AJ, Bishop DV, Ang QW, Pennell CE, Fisher SE. CNTNAP2 variants affect early language development in the general population. Genes Brain Behav. (2011) 10:451–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2011.00684.x

16. Zweier C. Severe intellectual disability associated with recessive defects in CNTNAP2 and NRXN1. Mol Syndromol. (2012) 2:181–5. doi: 10.1159/000331270

17. Ji W, Li T, Pan Y, Tao H, Ju K, Wen Z, et al. CNTNAP2 is significantly associated with schizophrenia and major depression in the Han Chinese population. Psychiatry Res. (2013) 207:225–8. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.09.024

18. Zhao YJ, Wang YP, Yang WZ, Sun HW, Ma HW, Zhao YR. CNTNAP2 Is significantly associated with speech sound disorder in the chinese han population. J Child Neurol. (2015) 30:1806–11. doi: 10.1177/0883073815581609

19. Smogavec M, Cleall A, Hoyer J, Lederer D, Nassogne MC, Palmer EE, et al. Eight further individuals with intellectual disability and epilepsy carrying bi-allelic CNTNAP2 aberrations allow delineation of the mutational and phenotypic spectrum. J Med Genet. (2016) 53:820–7. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2016-103880

20. Saint-Martin M, Joubert B, Pellier-Monnin V, Pascual O, Noraz N, Honnorat J. Contactin-associated protein-like 2, a protein of the neurexin family involved in several human diseases. Eur J Neurosci. (2018) 48:1906–23. doi: 10.1111/ejn.14081

21. Falsaperla R, Pappalardo XG, Romano C, Marino SD, Corsello G, Ruggieri M, et al. Intronic variant in CNTNAP2 gene in a boy with remarkable conduct disorder, minor facial features, mild intellectual disability, and seizures. Front Pediatr. (2020) 8:550. doi: 10.3389/fped.2020.00550

22. Poliak S, Peles E. The local differentiation of myelinated axons at nodes of Ranvier. Nat Rev Neurosci. (2003) 4:968–80. doi: 10.1038/nrn1253

23. Penagarikano O, Abrahams BS, Herman EI, Winden KD, Gdalyahu A, Dong H, et al. Absence of CNTNAP2 leads to epilepsy, neuronal migration abnormalities, and core autism-related deficits. Cell. (2011) 147:235–46. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.040

24. Anderson GR, Galfin T, Xu W, Aoto J, Malenka RC, Südhof TC. Candidate autism gene screen identifies critical role for cell-adhesion molecule CASPR2 in dendritic arborization and spine development. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. (2012) 109:18120–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1216398109

25. Beaudoin GMJ, Lee S-H, Singh D, Yuan Y, Ng Y-G, Reichardt LF, et al. Culturing pyramidal neurons from the early postnatal mouse hippocampus and cortex. Nat Protoc. (2012) 7:1741–54. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.099

26. Li Y, Chen Z, Gao Y, Pan G, Zheng H, Zhang Y, et al. Synaptic adhesion molecule Pcdh-γC5 mediates synaptic dysfunction in Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci. (2017) 37:9259–68. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1051-17.2017

27. Poliak S, Gollan L, Martinez R, Custer A, Einheber S, Salzer JL, et al. Caspr2, a new member of the neurexin superfamily, is localized at the juxtaparanodes of myelinated axons and associates with K+ channels. Neuron. (1999) 24:1037–47. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)81049-1

28. Varea O, Martin-De-Saavedra MD, Kopeikina KJ, Schurmann B, Fleming HJ, Fawcett-Patel JM, et al. Synaptic abnormalities and cytoplasmic glutamate receptor aggregates in contactin associated protein-like 2/Caspr2 knockout neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2015) 112:6176–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1423205112

29. Gao R, Zaccard CR, Shapiro LP, Dionisio LE, Martin-De-Saavedra MD, Piguel NH, et al. The CNTNAP2-CASK complex modulates GluA1 subcellular distribution in interneurons. Neurosci Lett. (2019) 701:92–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2019.02.025

30. Froemke RC, Merzenich MM, Schreiner CE. A synaptic memory trace for cortical receptive field plasticity. Nature. (2007) 450:425–9. doi: 10.1038/nature06289

31. Liu G. Local structural balance and functional interaction of excitatory and inhibitory synapses in hippocampal dendrites. Nat Neurosci. (2004) 7:373–9. doi: 10.1038/nn1206

32. Scott R, Sanchez-Aguilera A, Van Elst K, Lim L, Dehorter N, Bae SE, et al. Loss of Cntnap2 causes axonal excitability deficits, developmental delay in cortical myelination, and abnormal stereotyped motor behavior. Cereb Cortex. (2019) 29:586–97. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhx341

33. Gulledge AT, Kampa BM, Stuart GJ. Synaptic integration in dendritic trees. J Neurobiol. (2005) 64:75–90. doi: 10.1002/neu.20144

35. Gao R, Piguel NH, Melendez-Zaidi AE, Martin-De-Saavedra MD, Yoon S, Forrest MP, et al. CNTNAP2 stabilizes interneuron dendritic arbors through CASK. Mol Psychiatry. (2018) 23:1832–50. doi: 10.1038/s41380-018-0027-3

36. Wierenga CJ, Becker N, Bonhoeffer T. GABAergic synapses are formed without the involvement of dendritic protrusions. Nat Neurosci. (2008) 11:1044–52. doi: 10.1038/nn.2180

37. Lohmann C, Bonhoeffer T. A role for local calcium signaling in rapid synaptic partner selection by dendritic filopodia. Neuron. (2008) 59:253–60. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.05.025

38. Bridi M. S, Park S. M., Huang S.. (2017). Developmental disruption of GABA(A)R-meditated inhibition in Cntnap2 KO mice. eNeuro 4:ENEURO.0162-0117.2017. doi: 10.1523/ENEURO.0162-17.2017

Keywords: spontaneous recurrent seizures, CNTNAP2, c.2329 C>G mutation, missense mutation, E/I balance

Citation: Lu P, Wang F, Zhou S, Huang X, Sun H, Zhang Y-W, Yao Y and Zheng H (2021) A Novel CNTNAP2 Mutation Results in Abnormal Neuronal E/I Balance. Front. Neurol. 12:712773. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2021.712773

Received: 21 May 2021; Accepted: 24 August 2021;

Published: 19 October 2021.

Edited by:

Mohd Farooq Shaikh, Monash University, MalaysiaReviewed by:

Pablo Casillas-Espinosa, Monash University, AustraliaCopyright © 2021 Lu, Wang, Zhou, Huang, Sun, Zhang, Yao and Zheng. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Honghua Zheng, aG9uZ2h1YUB4bXUuZWR1LmNu

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.