- 1Shanghai Key Laboratory of Forensic Medicine, Key Lab of Forensic Science, Ministry of Justice, Shanghai Forensic Service Platform, Academy of Forensic Science, Shanghai, China

- 2Hongkou District Mental Health Center, Shanghai, China

- 3Shanghai Mental Health Center, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai, China

Few objective indices can be used when evaluating neurocognitive disorders after a traumatic brain injury (TBI). P300 has been widely studied in mental disorders, cognitive dysfunction, and brain injury. Daily life ability and social function are key indices in the assessment of neurocognitive disorders after a TBI. The present study focused on the correlation between P300 and impairment of daily living activity and social function. We enrolled 234 patients with neurocognitive disorders after a TBI according to ICD-10 and 277 age- and gender-matched healthy volunteers. The daily living activity and social function were assessed by the social disability screening schedule (SDSS) scale, activity of daily living (ADL) scale, and scale of personality change following a TBI. P300 was evoked by a visual oddball paradigm. The results showed that the scores of the ADL scale, SDSS scale, and scale of personality change in the patient group were significantly higher than those in the control group. The amplitudes of Fz, Cz, and Pz in the patient group were significantly lower than those in the control group and were negatively correlated with the scores of the ADL and SDSS scales. In conclusion, a lower P300 amplitude means a greater impairment of daily life ability and social function, which suggested more severity of neurocognitive disorders after a TBI. P300 could be a potential indicator in evaluating the severity of neurocognitive disorders after a TBI.

Introduction

In recent years, traumatic brain injury (TBI) has been noticeably increasing, which leads to millions of people suffering from long-term disabilities (1). Some patients with a craniocerebral injury tend to have an abnormal behavior and cognitive and social function impairments, and about 21.7% patients will exhibit symptoms of mental disorders (2). According to the severity of TBI, a psychiatric diagnosis was found in about 49% of patients with severe and moderate TBI and 34% of patients with mild TBI, compared to 18% in the control group (3). Therefore, more attention should be paid on neurocognitive disorders after a TBI, which result in large social and economic burden (4). However, many patients with TBI may not receive an adequate follow-up therapy because of their lack of a consistent concern of the symptoms (5). Some progress has been made in the relationship between TBI and cognitive impairment, but the pathogenesis of neurocognitive disorders after a TBI was still uncertain (6, 7). Few effective methods can be used in the assessment of neurocognitive disorders after a TBI. Although computed tomography (CT) scanning and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can recognize a structural injury in the brain, the results of CT scanning and MRI have little effect on evaluating the severity of functional injury, such as neurocognitive disorders after a TBI. No obvious brain structural changes at the time of assessment could be found in ~67% patients with mild traumatic brain injury, but some patients do exhibit an abnormal behavior and a cognitive impairment (8). Although more details of brain structure and function could be detected by using functional neuroimaging in patients with traumatic brain injury, the results of functional neuroimaging cannot be well-applied in the assessment of neurocognitive disorders after a TBI (9, 10).

Event-related potentials (ERPs) are neurophysiological markers that can reflect human information processing and provide an index of cognitive function, such as memory, attention, concentration, and problem-solving (11–13). The P300 wave is an ERP component recorded by an electroencephalogram (EEG). The P300 is a positive potential that peaks ~250–500 ms after stimulus onset and often serves as an index of cognitive function in the process of decision-making (14–16). Changes in P300 latency and amplitude have been found in patients with mild cognitive impairment (17–20). A longer latency and a smaller amplitude of P300 were demonstrated in schizophrenic patients compared with healthy people. In particular, a longer latency was revealed in patients with the paranoid subtype of schizophrenia than with other subtypes of schizophrenia (21–23). It has been reported that P300 could reflect the improvement of cognition when using atypical antipsychotics in schizophrenic patients (24–27). Prolonged P300 latency was reported in patients with major depressive disorders (MDD) (28); and furthermore, P300 latency was found to be significantly different between mild, moderate, and severe MDD (29). The P300 latency tended to be longer, and the amplitude tended to be smaller in patients with cerebral contusion and intracerebral hematoma (30, 31). Negative changes in ERPs have been found in patients with mild brain injury (32). In recent studies, P300-based brain–computer interfaces provide an additional communication channel for individuals with communication disabilities and new control options for patients with impairments of eye movement or vision (33–35).

Daily life ability and social function are key indices in the assessment of a TBI (36–38). The scales of social disability screening schedule (SDSS) and activity of daily living (ADL) were proved to be associated with the severity of neurocognitive disorders after a TBI (39). Some criteria for the assessment of psychiatric impairment in patients with neurocognitive disorders after a TBI also list daily living activity and social function as important evaluation standards, such as the “Guideline for Assessment of Impairment in the Injured” in China (40), the AMA Guides to the Evaluation of Permanent Impairment, 6th Revision, by the American Medical Association (41), and the AAPL Practice Guideline for the Forensic Evaluation of Psychiatric Disability by the American Association of Psychiatry and Law (42).

In the current study, we aimed to investigate the correlation between visual P300 and impairment of daily living activity and social function, which, to some extent, could reflect the severity of neurocognitive disorders after a TBI.

Materials and Methods

Participants

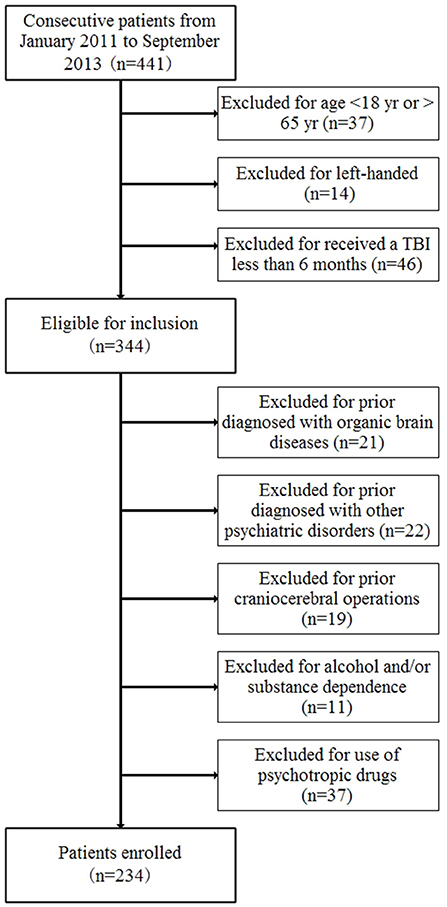

According to the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) criterion F07 and Z87.820, 234 patients with neurocognitive disorders after a TBI were enrolled from January 2011 to September 2013 in the Academy of Forensic Science (Figure 1). The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) age from 18 to 65 years old, (2) a diagnosis of neurocognitive disorders after a TBI according to the ICD-10 criteria, (3) right-handed, and (4) received a traumatic brain injury at least 6 months previously. The exclusion criteria included whether the patient had ever been diagnosed with other psychiatric disorders and organic brain diseases or experienced craniocerebral operations before the current TBI or with alcohol and/or substance dependence or use of psychotropic drugs. The control group comprised of 277 age- and gender-matched healthy volunteers who were made up by staff and students in the Academy of Forensic Science. All the healthy controls were volunteers and met the following inclusion and exclusion criteria: (1) age from 18 to 65 years old, (2) right-handed, (3) no mental disorders, (4) no family history of mental disorders, (5) no organic brain diseases, (6) no significant medical history, and (7) no use of psychotropic drugs. In addition, the subjects were also excluded if there had been any lack of consensus.

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Academy of Forensic Science. All the methods and procedures of the study were performed in accordance with the criteria laid out by the Declaration of Helsinki and other relevant national and international requirements for human research. All participants signed a written informed consent.

Scales and Intelligence Quotient Assessment

Self-reported clinical research forms were used to collect the demographic characteristics and experimental data. The ADL scale, SDSS scale, and scale of personality change following a traumatic brain injury were filled out according to the medical records and interviews by the researchers.

The daily life ability and social function were mainly evaluated by ADL scale, SDSS scale, and scale of personality change following a traumatic brain injury. The ADL scale lists 14 items, and each item is scored from 1 to 4, which provides a simple and feasible method to evaluate the severity of impairment of daily living ability. If the total scores are more than 16, the patients are deemed to have impairment of daily life ability. The higher the score means more severe impairment of daily living ability. The SDSS scales was originally developed by the Disability Assessment Schedule of World Health Organization. The SDSS scale is composed of 10 items, which is used to assess social function. Each item is scored from 0 = healthy or very minor defects to 2 = severe defect. If the total scores are more than 2, it means that the patients have a social dysfunction. A higher score means more severe impairment of a social function. Cronbach's α was 0.88–0.92 (43). The scale of personality change following a traumatic brain injury includes 19 items, which can be used to evaluate the level of personality change (44, 45). Each item is scored from 0 to 3: zero point means absence, one point means occasionally, two points mean sometimes, and three points mean frequently. If the total scores are 7–14, it means a mild personality change, 15–21 means a moderate personality change, and 22–57 means a severe personality change. The Kappa value of diagnostic consistency was 0.86. The sensitivity of scale was 95.5%, and the false positive rate was 2.4% (44).

The Wechsler Intelligence Test (Chinese version) was used to collect the intelligence quotient (IQ) levels of the subjects.

Stimuli and Procedures of Visual P300

The P300 waves were recorded by a Brain Master neurofeedback device (BrainMaster Technologies, Inc.). During the study, the subjects were seated in a dark and quiet room with an ambient temperature between 22 and 24°C. The subjects were instructed to be relaxed, keep awake, and focus on the screen. ERPs were recorded according to the 10–20 system. The reference electrodes were linked to the mastoid process. The impedance of Ag/AgCl surface electrodes was maintained below 5 kΩ. The oddball paradigm was used with the target stimuli randomly interspersed among the non-target stimuli. The target stimuli (circle, 5 cm in diameter) occurred 20% of the time and the non-target stimuli (square, 5 cm in length) 80%, with 300 stimuli presented in total. Each stimulus lasted 500 ms, with a white shape on a black background, and the interval of each stimulus was 500 ms. The subjects were required to press the F button on the keyboard when target stimuli (circle) occurred and press the J button when non-target stimuli (square) occurred.

The P300 component was defined as the positive peak with a latency of 300–500 ms at each electrode after the time of target stimuli onset. The amplitudes were measured as the maximum value of peaks to a pre-stimulus baseline, and the latency was measured from the start of the stimulus. The stimulus artifact of electro-oculogram and electromyography, high-amplitude noise (≥75 μV), and bad block were removed before the analysis. The EEG data were analyzed by the device mentioned above (Figure 2).

Statistical Analyses

Data were analyzed by IBM Statistical Product and Service Solutions, version 22.0 (IBM SPSS 22.0). The statistically significant level was set as P < 0.05. All data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Categorical data were compared by chi-square tests. Student's t-test was used to compare the variables between patients and healthy controls. Pearson's correlation analysis was used to calculate the correlation between parameters.

Results

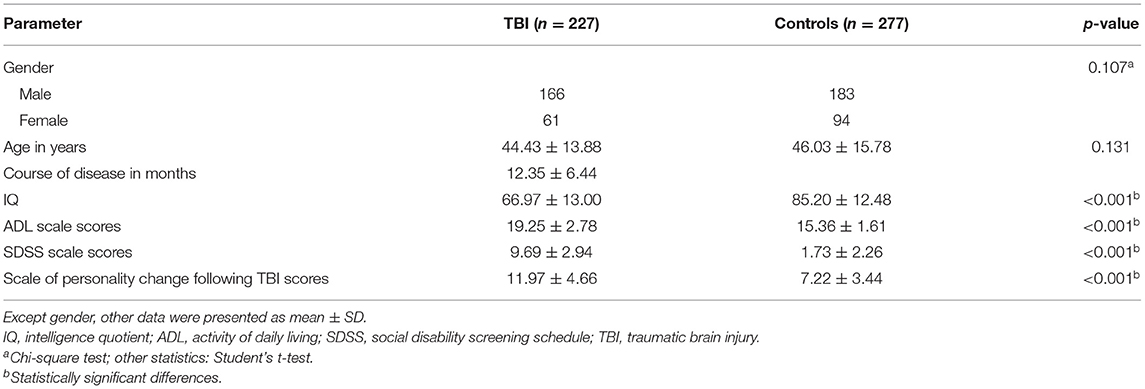

From the 234 patients with neurocognitive disorders after a TBI, 227 (97.01%) completed the study, and seven patients could not cooperate well and did not complete the study. All 277 healthy volunteers accomplished the study. As revealed in Table 1, no statistically significant difference was found between patients and controls in age and gender. The scores of ADL scale, SDSS scale, and scale of personality change following a TBI in the patient group were significantly higher than those in the control group (P < 0.001). The IQ in the patient group was significantly lower than that in the control group (P < 0.001). The button press accuracy of the target stimuli and the non-target stimuli in the patient group was significantly lower than that in the control group (P < 0.05). The response time of button press of the target stimuli and the non-target stimuli in the patient group was significantly longer than that in the control group (P < 0.05).

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics between patients with neurocognitive disorders after TBI and controls.

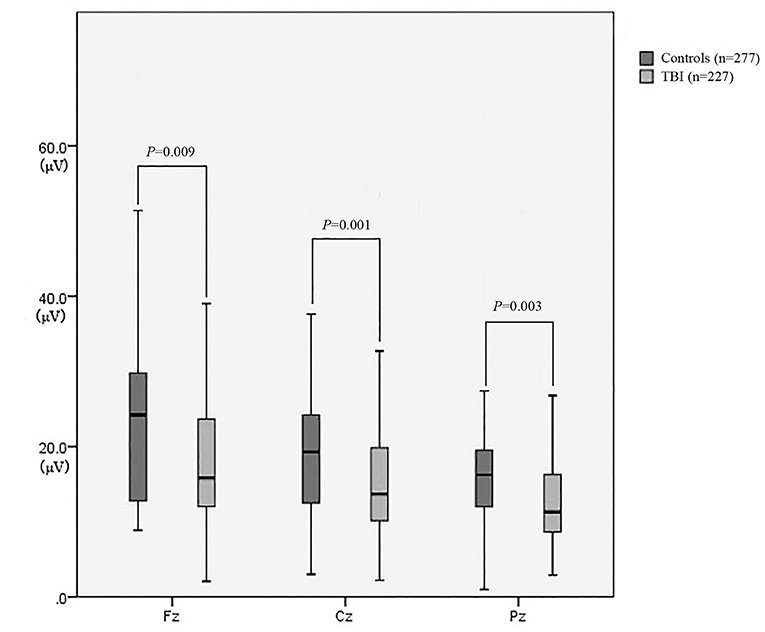

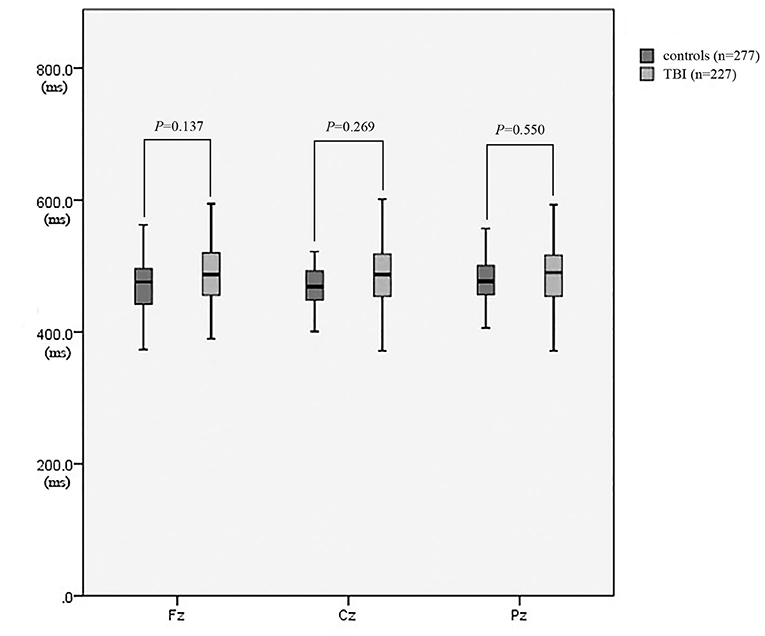

As revealed in Table 2, the amplitudes of Fz, Cz, and Pz in the patient group were significantly lower than those in the control group (P = 0.009, P = 0.001, and P = 0.003, respectively) (Figure 3). There was no significant difference in the latencies of Fz, Cz, and Pz between the patient group and the control group (P > 0.05; Figure 4).

Figure 3. The amplitude of P300 between patients with neurocognitive disorders after TBI and controls.

Figure 4. The latency of P300 between patients with neurocognitive disorders after TBI and controls.

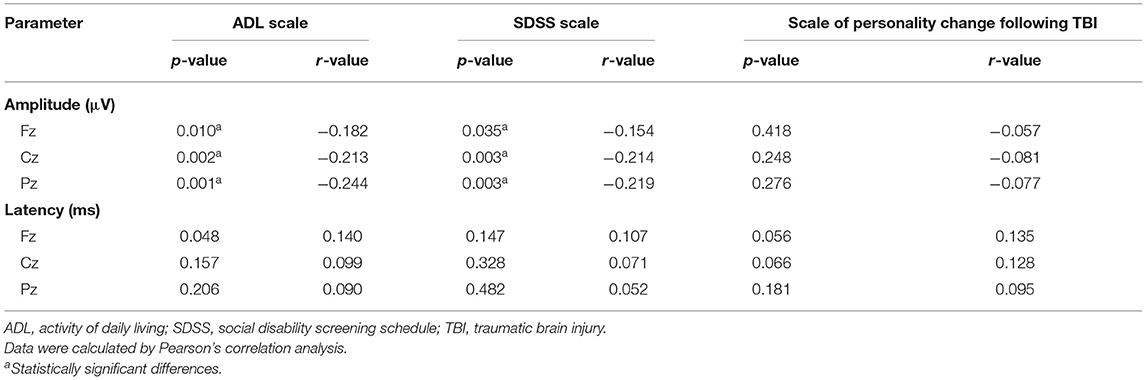

As revealed in Table 3, the amplitudes of Fz, Cz, and Pz in the patient group were negatively correlated with the scores of the ADL and SDSS scales (P < 0.05). There was no correlation between the amplitudes of Fz, Cz, and Pz and the scores of the scale of personality change following a TBI (P > 0.05). The latencies of Fz, Cz, and Pz showed no significant correlation between the scores of the ADL scale, SDSS scale, and scale of personality change following a TBI (P > 0.05).

Table 3. Correlations between P300 and scale scores in patients with neurocognitive disorders after TBI.

Discussion

The severity of neurocognitive disorders after a TBI was associated with lots of factors and difficult to be evaluated. The current study focused on how to evaluate the severity of mental disorders due to TBI through P300. The result showed that the intelligence quotients of patients were lower than those of healthy controls, which meant that patients with neurocognitive disorders after a TBI might suffer a mild intelligence impairment. The accuracy and response time of button press between the patient and control groups were also objective indicators which could reflect the levels of cognitive impairment in patients with neurocognitive disorders after a TBI. Mild intelligence impairment was one of the main symptoms of neurocognitive disorders after a TBI. P300 has been extensively studied in mild cognitive impairment and was regarded as an ideal marker for assessing brain function in cognitive diseases (46, 47). The assessment of P300 amplitudes and latencies might offer valuable information in patients with cognitive impairment (48)—for example, attenuated amplitude and longer latency (19, 49)—which was partly consistent with our findings that the amplitudes of patients were lower than those in healthy controls. The amplitudes of P300 reflect the allocation of attentional resources and the ability of information processing; therefore, the decrease of amplitude may mean a decreased ability of information processing, decreased neuronal efficiency, and impairment of attention (50–53). According to our findings, patients with neurocognitive disorders after a TBI may suffer from impairment of attention and information processing ability, which may lead to the impairment of daily life ability and social function. The latencies of P300 in the current study showed no significant difference between patients and healthy controls. The latencies of P300 were regarded to be related to cognitive performance (51). The latencies of P300 were found to have a significant difference between patients with mild TBI and patients with moderate and severe TBI (54). Although the current study found that the response time of button press in the patient group was significantly longer than those in the control group, a previous study showed that latency in behavioral response time was not correlated with the latency of P300 (55). Therefore, the reason why the current study found no significant difference between patients and healthy controls might be that the cognitive impairment of patients enrolled was mild and the latencies of P300 were associated with the severity of cognitive impairment.

The current study revealed the impairment of daily life ability and social function in patients with neurocognitive disorders after a TBI and the correlation between P300 amplitudes and daily life ability and social function. The impairment of daily life ability and social function was also found in patients with a TBI (56, 57). The daily life ability and social function were regarded as being more appropriate than symptoms when assessing a TBI and could comprehensively assess a TBI (56–58). A further study identified the value of evaluating the daily life ability and social function in patients with neurocognitive disorders after a TBI (39). According to our findings, the lower amplitudes of P300 mean a greater impairment of daily life ability and social function, which suggested more severity of neurocognitive disorders after a TBI. The main reason might be that patients with neurocognitive disorders after a TBI suffered the impairment of ability of information processing, which was mentioned above.

Personality change is also one of the main symptoms in neurocognitive disorders after a TBI, which would lead to the impairment of social function. The current study found that patients with neurocognitive disorders after a TBI did exhibit a personality change, but P300 showed no correlation with the severity of personality change. Personality change in neurocognitive disorders after a TBI includes apathy, affective lability, and aggression (39). Personality change was an acquired disease after a TBI, stress, etc., and the reason of personality change after a TBI is still unknown (59). Failure to regulate emotions might result in a personality change (60). Dysfunction of the frontal lobe was also regarded to be associated with a personality change (61). The P300 amplitude was reported as an abnormally enhanced amplitude in borderline personality disorder (62) and a decrement at the anterior electrode sites in antisocial personality disorder (63), which meant that P300 could also, to some extent, reflect a personality disorder. Therefore, P300 might be one of the indicators which could reveal a personality change in patients with neurocognitive disorders after a TBI but could not show the severity of a personality change.

Limitation

Some limitations should be clarified. First, considering the cooperation of subjects during the ERP tests, the symptoms of patients enrolled in the study were relatively mild. Second, the patients enrolled in the study suffered a mild TBI, and the aim of the study was to explore the severity of neurocognitive disorders after a TBI, so the injury areas were not analyzed. Third, due to the limitation of the ERP device and no analysis of injury areas, only three individual electrodes were used, and the differentiation of P3a and P3b could not be distinguished.

Conclusion

Impairment of daily life ability and social function and personality change were found in neurocognitive disorders after a TBI. The P300 amplitude was positively correlated with an impairment of daily life ability and social function. A lower P300 amplitude means a greater impairment of daily life ability and social function, which suggested more severity of neurocognitive disorders after a TBI. Therefore, P300 could be a potential indicator in evaluating the severity of neurocognitive disorders after a TBI.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the ethics committee of the Academy of Forensic Science. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

HL and NL participated in the design of the study and drafted the manuscript. YX performed the experiments. SZ and CL enrolled patients and healthy volunteers and performed statistical analyses. WC participated in the design of the study and helped in proofreading. WH and QZ conceived the study protocol and participated in the design and coordination of the study. All authors contributed to the final text and approved it.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81801881 and 81001354), the National Key R&D Program of China (2016YFC0800701), and the Science and Technology Committee of Shanghai Municipality (20DZ1200300, 19DZ2292700, and 17DZ2273200).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge all participants of the Academy of Forensic Science, Shanghai Mental Health Center and Hongkou District Mental Health Center, who provided help in this study.

References

1. Schwarzbold M, Diaz A, Martins ET, Rufino A, Amante LN, Thais ME, et al. Psychiatric disorders and traumatic brain injury. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. (2008) 4:797–816. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S2653

2. Deb S, Lyons I, Koutzoukis C, Ali I, McCarthy G. Rate of psychiatric illness 1 year after traumatic brain injury. Am J Psychiatry. (1999) 156:374–8.

3. Fann JR, Burington B, Leonetti A, Jaffe K, Katon WJ, Thompson RS. Psychiatric illness following traumatic brain injury in an adult health maintenance organization population. Arch Gen Psychiatry. (2004) 61:53–61. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.1.53

4. Binder S, Corrigan JD, Langlois JA. The public health approach to traumatic brain injury: an overview of CDC's research and programs. J Head Trauma Rehabil. (2005) 20:189–95. doi: 10.1097/00001199-200505000-00002

5. Seabury SA, Gaudette É, Goldman DP, Markowitz AJ, Brooks J, McCrea MA, et al. Assessment of follow-up care after emergency department presentation for mild traumatic brain injury and concussion: results from the TRACK-TBI Study. JAMA Netw Open. (2018) 1:e180210. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.0210

6. DeKosky ST, Abrahamson EE, Ciallella JR, Paljug WR, Wisniewski SR, Clark RS, et al. Association of increased cortical soluble abeta42 levels with diffuse plaques after severe brain injury in humans. Arch Neurol. (2007) 64:541–4. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.4.541

7. Johnson VE, Stewart W, Smith DH. Widespread τ and amyloid-β pathology many years after a single traumatic brain injury in humans. Brain Pathol. (2012) 22:142–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2011.00513.x

8. Henninger N, Sicard KM, Li Z, Kulkarni P, Dutzmann S, Urbanek C, et al. Differential recovery of behavioral status and brain function assessed with functional magnetic resonance imaging after mild traumatic brain injury in the rat. Crit Care Med. (2007) 35:2607–14. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000286395.79654.8D

9. Levine B, Fujiwara E, O'Connor C, Richard N, Kovacevic N, Mandic M, et al. In vivo characterization of traumatic brain injury neuropathology with structural and functional neuroimaging. J Neurotrauma. (2006) 23:1396–411. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.23.1396

10. Munson S, Schroth E, Ernst M. The role of functional neuroimaging in pediatric brain injury. Pediatrics. (2006) 117:1372–81. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0826

11. Polich J, Herbst KL. P300 as a clinical assay: rationale, evaluation, and findings. Int J Psychophysiol. (2000) 38:3–19. doi: 10.1016/S0167-8760(00)00127-6

12. Goodin D, Desmedt J, Maurer K, Nuwer MR. IFCN recommended standards for long-latency auditory event-related potentials. Report of an IFCN committee. international federation of clinical neurophysiology. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. (1994) 91:18–20. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(94)90014-0

13. Garcia-Larrea L, Cezanne-Bert G. P3, positive slow wave and working memory load: a study on the functional correlates of slow wave activity. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. (1998) 108:260–73. doi: 10.1016/S0168-5597(97)00085-3

14. Sutton S, Braren M, Zubin J, John ER. Evoked-potential correlates of stimulus uncertainty. Science. (1965) 150:1187–8. doi: 10.1126/science.150.3700.1187

15. Polich J, Criado JR. Neuropsychology and neuropharmacology of P3a and P3b. Int J Psychophysiol. (2006) 60:172–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2005.12.012

16. Polich J. Updating P300: an integrative theory of P3a and P3b. Clin Neurophysiol. (2007) 118:2128–48. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2007.04.019

17. Medvidovic S, Titlic M, Maras-Simunic M. P300 evoked potential in patients with mild cognitive impairment. Acta Inform Med. (2013) 21:89–92. doi: 10.5455/aim.2013.21.89-92

18. Lai CL, Lin RT, Liou LM, Liu CK. The role of event-related potentials in cognitive decline in Alzheimer's disease. Clin Neurophysiol. (2010) 121:194–9. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2009.11.001

19. Papaliagkas VT, Kimiskidis VK, Tsolaki MN, Anogianakis G. Cognitive event-related potentials: longitudinal changes in mild cognitive impairment. Clin Neurophysiol. (2011) 122:1322–6. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2010.12.036

20. Howe AS, Bani-Fatemi A, De Luca V. The clinical utility of the auditory P300 latency subcomponent event-related potential in preclinical diagnosis of patients with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease. Brain Cogn. (2014) 86:64–74. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2014.01.015

21. Jeon YW, Polich J. Meta-analysis of P300 and schizophrenia: patients, paradigms, and practical implications. Psychophysiology. (2003) 40:684–701. doi: 10.1111/1469-8986.00070

22. Jeon YW, Polich J. P300 asymmetry in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. (2001) 104:61–74. doi: 10.1016/S0165-1781(01)00297-9

23. Almeida PR, Vieira JB, Silveira C, Ferreira-Santos F, Chaves PL, Barbosa F, et al. Exploring the dynamics of P300 amplitude in patients with schizophrenia. Int J Psychophysiol. (2011) 81:159–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2011.06.006

24. Korostenskaja M, Dapsys K, Siurkute A, Maciulis V, Ruksenas O, Kahkonen S. Effects of olanzapine on auditory P300 and mismatch negativity (MMN) in schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. (2005) 29:543–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2005.01.019

25. Korostenskaja M, Dapsys K, Siurkute A, Dudlauskaite A, Pragaraviciene A, Maciulis V, et al. The effect of quetiapine on auditory P300 response in patients with schizoaffective disorder: preliminary study. Ann Clin Psychiatry. (2009) 21:49–50. doi: 10.1016/S0924-9338(09)71364-1

26. Zhang Y, Lehmann M, Shobeiry A, Hofer D, Johannes S, Emrich HM, et al. Effects of quetiapine on cognitive functions in schizophrenic patients: a preliminary single-trial ERP analysis. Pharmacopsychiatry. (2009) 42:129–34. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1112133

27. Park EJ, Han SI, Jeon YW. Auditory and visual P300 reflecting cognitive improvement in patients with schizophrenia with quetiapine: a pilot study. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. (2010) 34:674–80. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.03.011

28. Zhou L, Wang G, Nan C, Wang H, Liu Z, Bai H. Abnormalities in P300 components in depression: an ERP-sLORETA study. Nord J Psychiatry. (2019) 73:1–8. doi: 10.1080/08039488.2018.1478991

29. Tripathi SM, Mishra N, Tripathi RK, Gurnani KC. P300 latency as an indicator of severity in major depressive disorder. Ind Psychiatry J. (2015) 24:163–7. doi: 10.4103/0972-6748.181726

30. Rousseff RT, Tzvetanov P, Atanassova PA, Volkov I, Hristova I. Correlation between cognitive P300 changes and the grade of closed head injury. Electromyogr Clin Neurophysiol. (2006) 46:275–7.

31. Alberti A, Sarchielli P, Mazzotta G, Gallai V. Event-related potentials in posttraumatic headache. Headache. (2001) 41:579–85. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.2001.041006579.x

32. Potter DD, Jory SH, Bassett MR, Barrett K, Mychalkiw W. Effect of mild head injury on event-related potential correlates of stroop task performance. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. (2002) 8:828–37. doi: 10.1017/S1355617702860118

33. Yu Y, Liu Y, Yin E, Jiang J, Zhou Z, Hu D. an asynchronous hybrid spelling approach based on EEG-EOG signals for Chinese character input. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng. (2019) 27:1292–302. doi: 10.1109/TNSRE.2019.2914916

34. Jin J, Li S, Daly I, Miao Y, Liu C, Wang X, et al. The study of generic model set for reducing calibration time in P300-based brain-computer interface. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng. (2020) 28:3–12. doi: 10.1109/TNSRE.2019.2956488

35. Jin J, Chen Z, Xu R, Miao Y, Wang X, Jung TP. Developing a novel tactile p300 brain-computer interface with a cheeks-stim paradigm. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. (2020) 67:2585–93. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2020.2965178

36. Park HY, Maitra K, Martinez KM. The effect of occupation-based cognitive rehabilitation for traumatic brain injury: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Occup Ther Int. (2015) 22:104–16. doi: 10.1002/oti.1389

37. Duclos C, Beauregard MP, Bottari C, Ouellet MC, Gosselin N. The impact of poor sleep on cognition and activities of daily living after traumatic brain injury: a review. Aust Occup Ther J. (2015) 62:2–12. doi: 10.1111/1440-1630.12164

38. Sirois K, Tousignant B, Boucher N, Achim AM, Beauchamp MH, Bedell G, et al. The contribution of social cognition in predicting social participation following moderate and severe TBI in youth. Neuropsychol Rehabil. (2019) 29:1383–1398. doi: 10.1080/09602011.2017.1413987

39. Zhang Q, Zhou X, Gao D, Tang T, Fan H. Function disorder assessment on patients with mild psychiatric impairment due to road traffic accidents. J Forensic Med. (2014) 30:23–6. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1004-5619.2014.01.005

40. Xia W. The principle of “guideline for assessment of impairment in the injured”. J Forensic Med. (2016) 32:211–4. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1004-5619.2016.03.012

41. Granacher RP. Traumatic Brain Injury: Methods for Clinical and Forensic Neuropsychiatric Assessment. Boca Raton: CRC Press (2003).

42. Gold LH, Anfang SA, Drukteinis AM, Metzner JL, Price M, Wall BW, et al. AAPL practice guideline for the forensic evaluation of psychiatric disability. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. (2008) 36 (4 Suppl):s3–50. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000270799.12573.96

43. Liu Z, Gao B, Yuan S. The rating scale of social ability: development, and testing of reliability and validity. Chin J Clin Psychol. (2005) 13:19–22. doi: 10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2005.01.005

44. Li X, Gao B, Wu D, Liang W, Ding S. Quantitative evaluation of personality changes induced by craniocerebral injury. Chin J Clin Rehabil. (2006) 10:10–12. doi: 10.12307/j.issn.2095-4344.2006.06.004

45. Fan H, Zhang Q, Tang T, Cai W. Personality change due to brain trauma caused by traffic accidents and its assessment of psychiatric impairment. J Forensic Med. (2016) 32:100–4. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1004-5619.2016.02.006

46. Egerhazi A, Glaub T, Balla P, Berecz R, Degrell I. P300 in mild cognitive impairment and in dementia. Psychiatr Hung. (2008) 23:349–57.

47. Polich J, Corey-Bloom J. Alzheimer's disease and P300: review and evaluation of task and modality. Curr Alzheimer Res. (2005) 2:515–25. doi: 10.2174/156720505774932214

48. Pedroso RV, Fraga FJ, Corazza DI, Andreatto CA, Coelho FG, Costa JL, et al. P300 latency and amplitude in Alzheimer's disease: a systematic review. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. (2012) 78:126–32. doi: 10.1590/S1808-86942012000400023

49. Papadaniil CD, Kosmidou VE, Tsolaki A, Tsolaki M, Kompatsiaris IY, Hadjileontiadis LJ. Cognitive MMN and P300 in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease: a high density EEG-3D vector field tomography approach. Brain Res. (2016) 1648 (Pt. A):425–33. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2016.07.043

50. Geisler MW, Morgan CD, Covington JW, Murphy C. Neuropsychological performance and cognitive olfactory event-related brain potentials in young and elderly adults. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. (1999) 21:108–26. doi: 10.1076/jcen.21.1.108.935

51. Hansenne M. The p300 cognitive event-related potential. II. Individual variability and clinical application in psychopathology. Neurophysiol Clin. (2000) 30:211–31. doi: 10.1016/S0987-7053(00)00224-0

52. Ladouce S, Donaldson DI, Dudchenko PA, Ietswaart M. Mobile EEG identifies the re-allocation of attention during real-world activity. Sci Rep. (2019) 9:15851. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-51996-y

53. van der Westhuizen N, Biagio-de Jager L, Rheeder P. P300 event-related potentials in normal-hearing adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am J Audiol. (2020) 29:120–8. doi: 10.1044/2019_AJA-19-00095

54. Soldatovic-Stajic B, Misic-Pavkov G, Bozic K, Novovic Z, Gajic Z. Neuropsychological and neurophysiological evaluation of cognitive deficits related to the severity of traumatic brain injury. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. (2014) 18:1632–7. doi: 10.1002/9780470515167.ch32

55. Segalowitz SJ, Dywan J, Unsal A. Attentional factors in response time variability after traumatic brain injury: an ERP study. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. (1997) 3:95–107. doi: 10.1017/S1355617797000957

56. Whitnall L, McMillan TM, Murray GD, Teasdale GM. Disability in young people and adults after head injury: 5-7 year follow up of a prospective cohort study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. (2006) 77:640–5. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2005.078246

57. Hammond FM, Grattan KD, Sasser H, Corrigan JD, Rosenthal M, Bushnik T, et al. Five years after traumatic brain injury: a study of individual outcomes and predictors of change in function. NeuroRehabilitation. (2004) 19:25–35. doi: 10.3233/NRE-2004-19104

58. Millis SR, Rosenthal M, Novack TA, Sherer M, Nick TG, Kreutzer JS, et al. Long-term neuropsychological outcome after traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil. (2001) 16:343–55. doi: 10.1097/00001199-200108000-00005

59. Weddell RA, Wood RL. Exploration of correlates of self-reported personality change after moderate-severe traumatic brain injury. Brain Injury. (2016) 30:1362–71. doi: 10.1080/02699052.2016.1195921

60. Davidson RJ, Putnam KM, Larson CL. Dysfunction in the neural circuitry of emotion regulation–a possible prelude to violence. Science. (2000) 289:591–4. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5479.591

61. Tateno A, Jorge RE, Robinson RG. Clinical correlates of aggressive behavior after traumatic brain injury. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. (2003) 15:155–60. doi: 10.1176/jnp.15.2.155

62. Meares R, Melkonian D, Gordon E, Williams L. Distinct pattern of P3a event-related potential in borderline personality disorder. Neuroreport. (2005) 16:289–93. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200502280-00018

Keywords: neurocognitive disorders, traumatic brain injury, event-related potential, P300, daily life ability, social function

Citation: Li H, Li N, Xing Y, Zhang S, Liu C, Cai W, Hong W and Zhang Q (2021) P300 as a Potential Indicator in the Evaluation of Neurocognitive Disorders After Traumatic Brain Injury. Front. Neurol. 12:690792. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2021.690792

Received: 06 April 2021; Accepted: 12 August 2021;

Published: 09 September 2021.

Edited by:

Peter Bergold, SUNY Downstate Medical Center, United StatesReviewed by:

Hale Z. Toklu, University of Central Florida, United StatesJing Jin, East China University of Science and Technology, China

Adam Mehlenbacher, Duke University Medical Center, United States

Copyright © 2021 Li, Li, Xing, Zhang, Liu, Cai, Hong and Zhang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Qinting Zhang, emhhbmdxaW50aW5nJiN4MDAwNDA7MTI2LmNvbQ==; Wu Hong, ZHJob25nd3UmI3gwMDA0MDsxMjYuY29t

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Haozhe Li

Haozhe Li Ningning Li

Ningning Li Yan Xing1

Yan Xing1