- Comprehensive Epilepsy Center, Seirei Hamamatsu General Hospital, Hamamatsu, Japan

Introduction: We hypothesized that epilepsy surgery for adult patients with temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) who obtained freedom from seizures could provide opportunities for these patients to continue their occupation, and investigated continuity of occupation to test this postulation.

Methods: Data were obtained from patients who had undergone resective surgery for medically intractable TLE between October 2009 and April 2019 in our hospital. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) ≥16 years old at surgery; (2) post-operative follow-up ≥12 months; (3) seizure-free period ≥12 months. As a primary outcome, we evaluated employment status before and after surgery, classified into three categories as follows: Level 0, no job; Level 1, students or homemakers (financially supported by a family member); and Level 2, working. Neuropsychological status was also evaluated as a secondary outcome.

Results: Fifty-one (87.9%) of the 58 enrolled TLE patients who obtained freedom from seizures after surgery continued working as before or obtained a new job (employment status: Level 2). A significant difference in employment status was identified between before and after surgery (p = 0.007; Wilcoxon signed-rank test). Twenty-eight patients (48.3%) were evaluated for neuropsychological status both before and after surgery. Significant differences in Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-III scores were identified between before and after surgery (p < 0.05 each; paired t-test).

Conclusion: Seizure freedom could be a factor that facilitates job continuity, although additional data are needed to confirm that possibility. Further investigation of job continuity after epilepsy surgery warrants an international, multicenter study.

Introduction

A surgical strategy is currently considered preferable for treating drug-resistant temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) (1, 2), and physicians and patients thus frequently choose surgical treatments for drug-resistant TLE. Some authors have suggested that the unemployment rate is reduced after epilepsy surgery (3–5). We therefore theorized that the surgical strategy should be chosen more frequently for patients with intractable TLE. However, many patients with intractable TLE hesitate to undergo surgery when offered this treatment option. This hesitation is probably because surgery may be associated with cognitive and other permanent changes (6). For example, one report about occupations of epilepsy patients reported that the ability to continue an occupation at the same level was a critical issue for patients such as musicians (7). Consequently, physicians need to consider whether patients will be able to continue their regular activities post-operatively.

A large amount of research into employment and unemployment of individuals with epilepsy already exists (8–13), along with research examining intelligence quotient (IQ) in children with epilepsy (14–20). However, clear answers have been lacking regarding whether patients can continue their occupation post-operatively (12). Job continuity might thus be an important factor that physicians should take into account. In this study, we hypothesized that epilepsy surgery for patients with TLE who obtained freedom from seizures would provide opportunities to continue their occupation. The purpose of this study was to investigate continuity of occupation in adult patients with TLE.

Methods

Patients

Data were obtained from all 78 patients who had undergone resective surgery for medically intractable TLE between October 2009 and April 2019 in our hospital. Of these, 58 patients (24 women, 34 men) fulfilled the following inclusion criteria: 1) age ≥16 years at surgery; 2) follow-up ≥12 months after surgery; 3) a seizure-free (International League Against Epilepsy classification 1: completely seizure-free, no auras) (21) period ≥12 months during follow-up after surgery. Twelve patients <15 years old, six patients who could not obtain freedom from seizures, and three patients who did not fulfill the follow-up criterion were excluded from the primary outcome measurement, but were still analyzed for secondary outcomes.

Epilepsy Surgery

All patients received standardized pre-operative evaluations, comprising electroencephalography (EEG), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), long-term video-EEG, interictal 2-[18F]fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography (18FDG-PET), iomazenil-single-photon emission computed tomography (IMZ-SPECT) and the Wada test, and had been diagnosed with intractable TLE. Based on the results of these examinations, neuropsychological assessment and employment status of every patient, appropriate treatment strategies were discussed at conferences in our comprehensive epilepsy center, with the participation of pediatric neurologists, neurologists, neurosurgeons, neurophysiologists, and neuropsychologists. Some patients with MRI-negative findings, possible bilateral temporal lobe onset, or involvement of a large area of neocortex underwent subdural grid electrode placement and depth electrode insertion on the appropriate region, as necessary. All patients underwent one of the following resective surgeries: anterior temporal lobectomy; hippocampal transection; selective amygdalohippocampectomy; or focus resection. All resected specimens were histopathologically examined except for the case of hippocampal transection.

Primary Outcome Measurement—Employment Status and Occupations

We evaluated employment status in all patients preoperatively and ≥12 months after resective surgery. Employment status was classified into the following 3 categories: Level 0, no job; Level 1, students or homemakers (financially supported by a family member); or Level 2, working. The post-operative employment status used for this study was recorded at the time of last follow-up evaluation at an outpatient clinic.

In accordance with the 2008 ISCO (ISCO-08) by the International Labor Organization, we divided occupations into 10 major groups: 1) Managers; 2) Professionals; 3) Technicians and associate professionals; 4) Clerical support workers; 5) Service and sales workers; 6) Skilled agricultural, forestry and fishery workers; 7) Craft and related trade workers; 8) Plant and machine operators, and assemblers; 9) Elementary occupations; and 10) Armed forces occupations. As housemakers, students, and the unemployed cannot be classified by ISCO-08, we listed these independently.

Secondary Outcome Measurements

Neuropsychological Assessment

Neuropsychological status was evaluated by both the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-III (WAIS-III) and the Wechsler Memory Scale-revised (WMS-R) preoperatively and ≥3 months after resective surgery. From among the 58 patients enrolled in this study, we assessed changes in cognitive function as evaluated by WAIS-III [verbal IQ (VIQ), performance IQ (PIQ), full-scale IQ (FIQ)] and memory function as evaluated by WMS-R before and after surgery in 28 patients (48.3%) who were able to be evaluated both preoperatively and ≥3 months after resective surgery.

Comparison Between Patients With Seizure Freedom and With Residual Seizures

Employment status before and after surgery was compared between patients with seizure freedom compared to a reference group with residual seizures.

Statistical Analysis

Data from employment status were statistically analyzed. Comparison of employment status before and after surgery was also analyzed by Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Age at seizure onset and seizure frequency for each employment status prior to resective surgery were compared using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). We used paired t-tests for comparisons of scores acquired by WMS-R and WAIS-III before and after surgery as neuropsychological examinations. Values of p < 0.05 were considered to indicate significant differences in all analyses. Easy R (EZR) statistical software (Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan) was used for all statistical analyses.

Ethics Approval

The ethics committee at our hospital approved this study protocol in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (permission number: 3349).

Results

Patient Characteristics

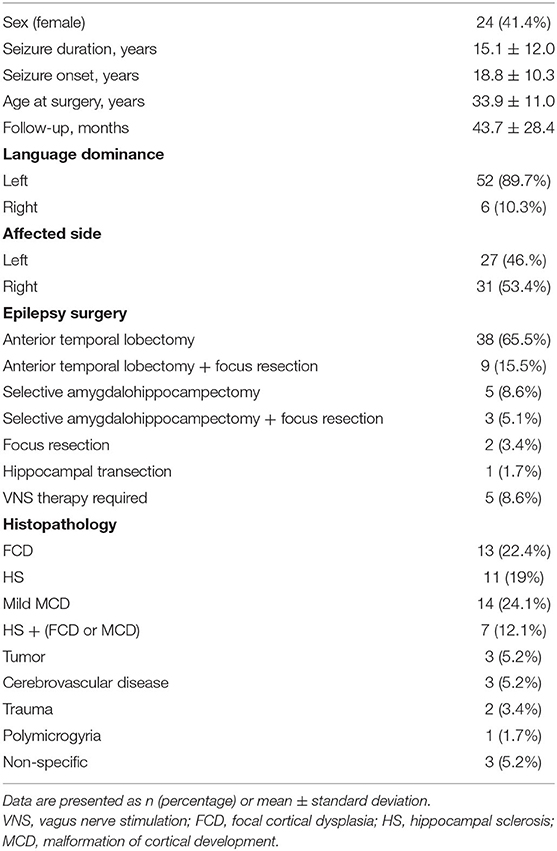

We investigated 58 patients who fulfilled our inclusion criteria. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the enrolled patients.

Only one patient experienced surgical complications, as intracranial hemorrhage, the day after left anterior temporal lobectomy, and underwent evacuation of the hematoma. Forty-four patients had intracranial electrodes inserted to determine the extent of surgical resection with no surgical complications. Two patients had undergone vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) therapy before resective surgery, and three patients underwent implantation of a generator for VNS after resective surgery, because post-operative seizure control proved insufficient. All patients with VNS therapy obtained freedom from seizures for ≥12 months. Age at seizure onset and seizure duration showed no significant effects on employment status prior to resective surgery (p = 0.417, p = 0.655, respectively).

Occupational Continuity as a Primary Outcome Measurement

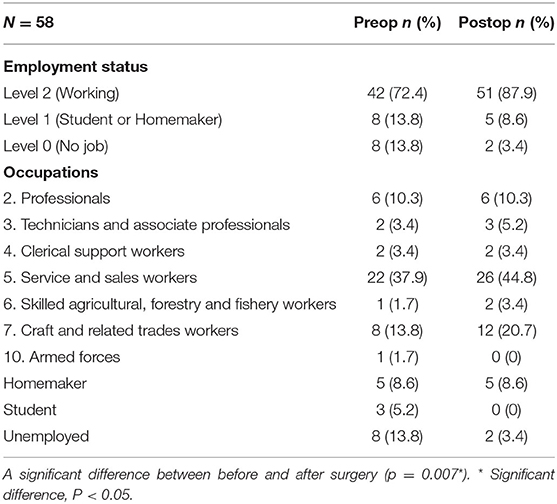

Table 2 shows pre- and post-operative employment status and occupations of the 58 enrolled patients. A significant difference in employment status was seen between before and after surgery (p = 0.007).

Secondary Outcome Measurements

Neuropsychological Assessment and Employment Status

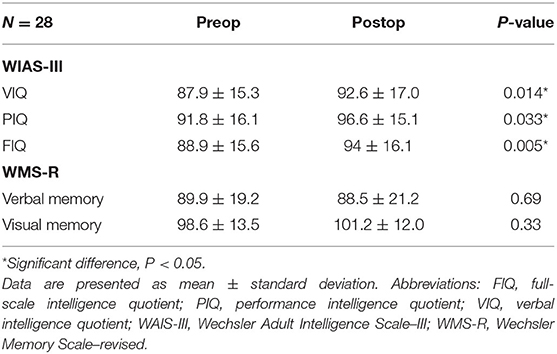

Table 3 shows the results of neuropsychological assessments before and after surgery in the 28 of the 58 enrolled patients who were able to be evaluated using WAIS-III and WMS-R both preoperatively and ≥3 months after resective surgery. Mean duration from surgery to evaluation was 19.8 months. Significant differences in VIQ, PIQ, and FIQ scores were evaluated by WAIS-III before and after surgery. Among the 28 patients, three patients (one student and two with no job before surgery) obtained employment after surgery. No significant relationships were apparent between post-operative employment status and memory outcomes according to visual (p = 0.868) and verbal (p = 0.326) memory scales.

Patients With Residual Seizures

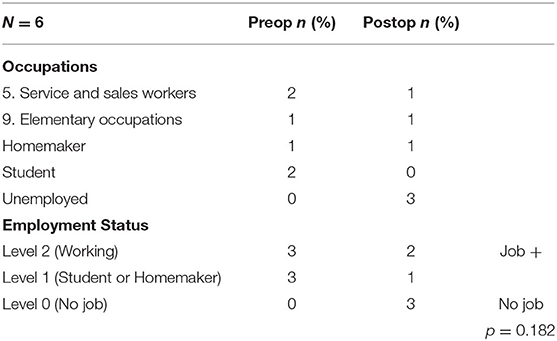

Six patients could not obtain freedom from seizures (Table 4). Among these, two patients who were employed before the surgery lost their job and were unable to obtain other employment. One patient who used to be employed at a company changed his job and was hired as a person with disability at a different company. Two patients who were high school students before the surgery were unable to obtain employment and continued living unemployed with their parents. One patient could continue with housework. As a result, only three patients with residual seizures were able to continue with employment.

Discussion

In this study, 97% of patients who obtained seizure freedom were able to retain their job. Two of the 58 patients (3%) had no job, a rate similar to the Japanese unemployment rate (3.4% in 2018; https://www.macrotrends.net/countries/JPN/japan/unemployment-rate). From this perspective, being seizure-free appears to represent an important factor behind staying employed. Among the 42 patients (72%) who could continue with employment, 34 patients could stay in the same job, but eight patients (19%) changed their job or employer. We are unable to determine in the present study whether there were negative or positive impacts in these eight patients. However, in addition to the fact that 42 patients (72%) did not lose their jobs, six patients (10%) obtained new jobs, and three students obtained jobs after graduation, suggesting that seizure freedom contributed to increased social participation.

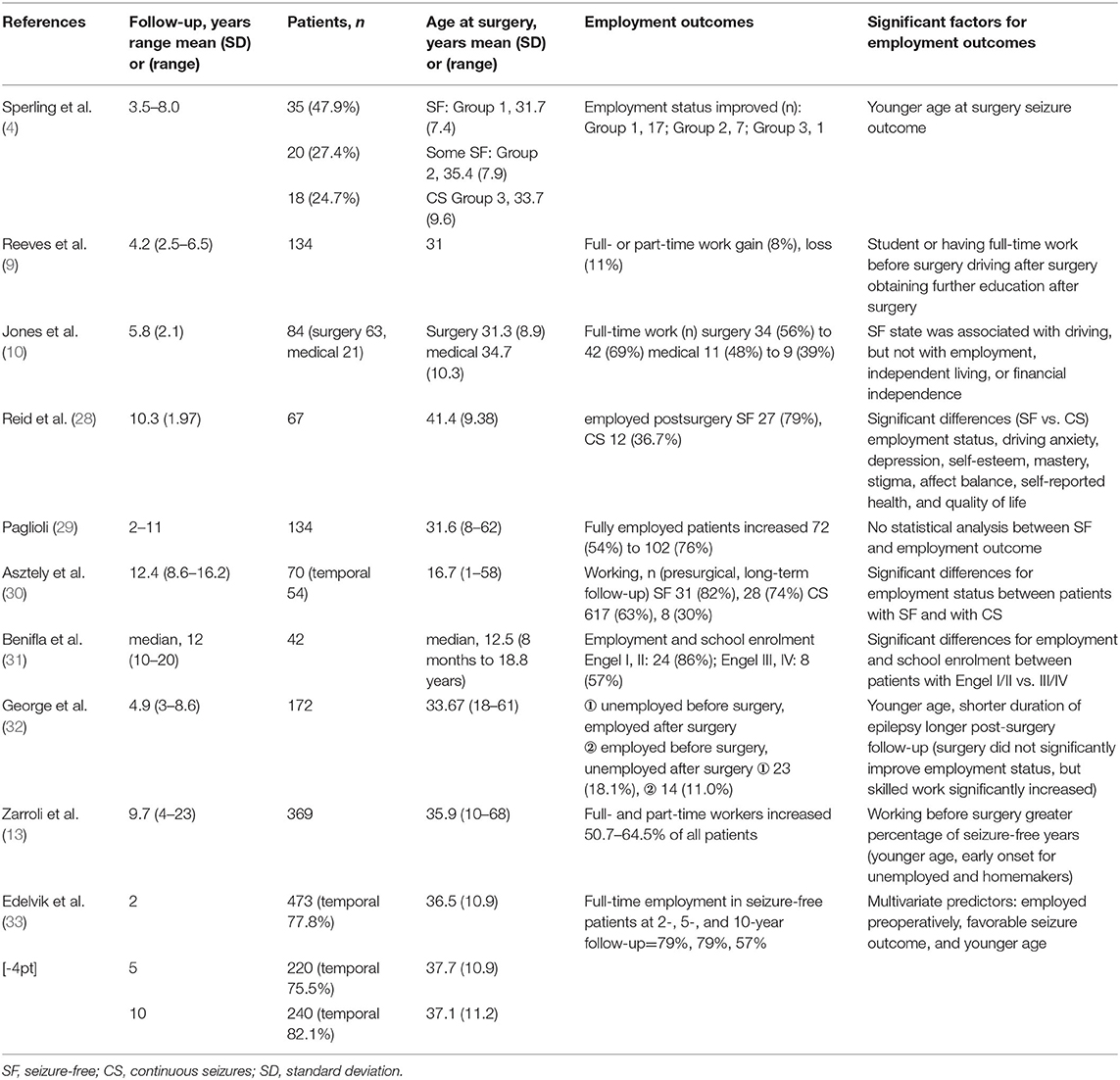

Lifetime employment and a seniority-based wage system have remained fairly well-entrenched in Japan, although recent international trends have slowly been changing the system. In the Japanese system, which involves hiring workers directly out of high school or college and retaining them until mandatory retirement, employer-employee relationships have been likened to the strong bonds of family or parent-child relationships (22, 23). Typical Japanese businesspeople who work for these types of companies used to secure lifetime employment and seniority-based wage structure, but nowadays due to a prolonged economic recession and globalization, the context has been changing. It is not uncommon for many individuals to stay at the same company, as changing jobs is not always advantageous (24–26). The concept of employment continuity is thus important in Japan. This concept could be also important in many East-Asian capitalist countries, as many have used similar systems (25, 27). Therefore, while many studies have assessed relationships between employment and seizure outcomes in Western countries, as shown in Table 5, little information has been accumulated regarding job continuity.

Table 5. Other studies assessing the relationship between employment status and seizure outcome in patients after temporal lobe surgery.

Most studies have reported that good seizure outcomes improved post-surgical employment status. Employment before surgery, younger age at surgery and shorter duration of epilepsy are also significant predictors of good employment status (4, 28, 30, 31, 33). However, George et al. (32) reported that pre- and post-surgical employment status did not differ significantly, although a significant increase was apparent for skilled workers.

The post-operative IQ of patients in this study improved, which might contribute to job retention. However, as we did not analyze correlations between job continuity and improvements in IQ, confirmation of this correlation was beyond the scope of our investigation.

As study limitations, this cross-sectional, observational, non-randomized study was carried out as a retrospective electronic chart review of patients with surgically treated temporal lobe epilepsy in a single institution, and the outcomes were inevitably influenced by the small cohort size, retrospective bias, and regional differences. As differences seem to exist between developed and developing countries (34, 35), further investigation of job continuity after epilepsy surgery warrants an international, multicenter study.

Conclusion

Seizure freedom could be a factor that facilitates job continuity, but additional data are needed to support that assertion. Further investigation of job continuity after epilepsy surgery warrants an international, multicenter study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by The ethics committee at our hospital approved this study protocol in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (permission number: 3349). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

TN, AF, KN, SB, HE, KS, TYamaz, and TO: acquisition of data. TN, AF, TO, and HE: analysis and interpretation of data. TN, AF, and TYamam: epilepsy surgery. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1. Elger CE, Schmidt D. Modern management of epilepsy: a practical approach. Epilepsy Behav. (2008) 12:501–39. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2008.01.003

2. Perucca P, Scheffer IE, Kiley M. The management of epilepsy in children and adults. Med J Aust. (2018) 208:226–33. doi: 10.5694/mja17.00951

3. Silfvenius H. Pre- and post-operative rehabilitation related to epilepsy surgery. Acta Neurochir Suppl (Wien). (1990) 50:100–6. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-9104-0_20

4. Sperling MR, Saykin AJ, Roberts FD, French JA, O'Connor MJ. Occupational outcome after temporal lobectomy for refractory epilepsy. Neurology. (1995) 45:970–7. doi: 10.1212/wnl.45.5.970

6. Sherman EM, Wiebe S, Fay-McClymont TB, Tellez-Zenteno J, Metcalfe A, Hernandez-Ronquillo L, et al. Neuropsychological outcomes after epilepsy surgery: systematic review and pooled estimates. Epilepsia. (2011) 52:857–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2011.03022.x

7. Schulz R, Horstmann S, Jokeit H, Woermann FG, Ebner A. Epilepsy surgery in professional musicians: subjective and objective reports of three cases. Epilepsy Behav. (2005) 7:552–8. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2005.07.009

8. Augustine EA, Novelly RA, Mattson RH, Glaser GH, Williamson PD, Spencer DD, et al. Occupational adjustment following neurosurgical treatment of epilepsy. Ann Neurol. (1984) 15:68–72. doi: 10.1002/ana.410150113

9. Reeves AL, So EL, Evans RW, Cascino GD, Sharbrough FW, O'Brien PC, et al. Factors associated with work outcome after anterior temporal lobectomy for intractable epilepsy. Epilepsia. (1997) 38:689–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1997.tb01238.x

10. Jones JE, Berven NL, Ramirez L, Woodard A, Hermann BP. Long-term psychosocial outcomes of anterior temporal lobectomy. Epilepsia. (2002) 43:896–903. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2002.43201.x

11. Lee SA. What we confront with employment of people with epilepsy in Korea. Epilepsia. (2005) 46 (Suppl. 1):57–8. doi: 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2005.461018.x

12. Locharernkul C, Kanchanatawan B, Bunyaratavej K, Srikijvilaikul T, Deesudchit T, Tepmongkol S, et al. Quality of life after successful epilepsy surgery: evaluation by occupational achievement and income acquisition. J Med Assoc Thai. (2005) 88 (Suppl. 4):S207–13.

13. Zarroli K, Tracy JI, Nei M, Sharan A, Sperling MR. Employment after anterior temporal lobectomy. Epilepsia. (2011) 52:925–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2011.03098.x

14. Levisohn PM. Epilepsy surgery in children with developmental disabilities. Semin Pediatr Neurol. (2000) 7:194–203. doi: 10.1053/spen.2000.9216

15. Olsson I, Danielsson S, Hedström A, Nordborg C, Viggedal G, Uvebrant P, et al. Epilepsy surgery in children with accompanying impairments. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. (2013) 17:645–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2013.06.004

16. Van Schooneveld MM, Braun KP. Cognitive outcome after epilepsy surgery in children. Brain Dev. (2013) 35:721–9. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2013.01.011

17. Viggedal G, Olsson I, Carlsson G, Rydenhag B, Uvebrant P. Intelligence two years after epilepsy surgery in children. Epilepsy Behav. (2013) 29:565–70. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2013.10.012

18. Ramantani G, Kadish NE, Anastasopoulos C, Brandt A, Wagner K, Strobl K, et al. Epilepsy surgery for glioneuronal tumors in childhood: avoid loss of time. Neurosurgery. (2014) 74:648–57; discussion 657. doi: 10.1227/neu.0000000000000327

19. Meekes J, van Schooneveld MM, Braams OB, Jennekens-Schinkel A, van Rijen PC, Hendriks MP, et al. Parental education predicts change in intelligence quotient after childhood epilepsy surgery. Epilepsia. (2015) 56:599–607. doi: 10.1111/epi.12938

20. Skirrow C, Cross JH, Owens R, Weiss-Croft L, Martin-Sanfilippo P, Banks T, et al. Determinants of IQ outcome after focal epilepsy surgery in childhood: A longitudinal case-control neuroimaging study. Epilepsia. (2019) 60:872–84. doi: 10.1111/epi.14707

21. Wieser HG, Blume WT, Fish D, Goldensohn E, Hufnagel A, King D, et al. ILAE Commission Report. Proposal for a new classification of outcome with respect to epileptic seizures following epilepsy surgery. Epilepsia. (2001) 42, 282–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2001.35100.x

23. Ono H. Lifetime employment in Japan: concepts and measurements. J Japanese Int Econ. (2010) 24:1–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jjie.2009.11.003

24. Aihara H, Iki M. Effects of socioeconomic factors on suicide from 1980 through 1999 in Osaka Prefecture, Japan. J Epidemiol. (2002) 12:439–49. doi: 10.2188/jea.12.439

25. Jung E, Cheon B-Y. Economic crisis and changes in employment relations in Japan and Korea. Asian Survey. (2006) 46:457–76. doi: 10.1525/as.2006.46.3.457

26. Kagamimori S, Gaina A, Nasermoaddeli A. Socioeconomic status and health in the Japanese population. Soc Sci Med. (2009) 68:2152–60. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.03.030

27. Budhwar P, Debrah YA. Future research on human resource management systems in Asia. Asia Pacific J Management. (2008) 26:197. doi: 10.1007/s10490-008-9103-6

28. Reid K, Herbert A, Baker GA. Epilepsy surgery: patient-perceived long-term costs and benefits. Epilepsy Behav. (2004) 5:81–7. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2003.10.017

29. Paglioli E, Palmini A, Paglioli E, da Costa JC, Portuguez M, Martinez JV, et al. Survival analysis of the surgical outcome of temporal lobe epilepsy due to hippocampal sclerosis. Epilepsia. (2004) 45:1383–91. doi: 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2004.22204.x

30. Asztely F, Ekstedt G, Rydenhag B, Malmgren K. Long term follow-up of the first 70 operated adults in the Goteborg Epilepsy Surgery Series with respect to seizures, psychosocial outcome and use of antiepileptic drugs. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. (2007) 78:605–9. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2006.098244

31. Benifla M, Rutka JT, Otsubo H, Lamberti-Pasculli M, Elliott I, Sell E, et al. Long-term seizure and social outcomes following temporal lobe surgery for intractable epilepsy during childhood. Epilepsy Res. (2008) 82:133–8. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2008.07.012

32. George L, Iyer RS, James R, Sankara Sarma P, Radhakrishnan K. Employment outcome and satisfaction after anterior temporal lobectomy for refractory epilepsy: a developing country's perspective. Epilepsy & Behavior. (2009) 16:495–500. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2009.08.020

33. Edelvik A, Flink R, Malmgren K. Prospective and longitudinal long-term employment outcomes after resective epilepsy surgery. Neurology. (2015) 85:1482–90. doi: 10.1212/wnl.0000000000002069

34. Jost J, Millogo A, Preux PM. Antiepileptic Treatments in Developing Countries. Curr Pharm Des. (2017) 23:5740–8. doi: 10.2174/1381612823666170809103202

Keywords: occupation continuity, seizure freedom, epilepsy surgery, intelligence quotient, employment

Citation: Nozaki T, Fujimoto A, Yamazoe T, Niimi K, Baba S, Yamamoto T, Sato K, Enoki H and Okanishi T (2021) Freedom From Seizures Might Be Key to Continuing Occupation After Epilepsy Surgery. Front. Neurol. 12:585191. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2021.585191

Received: 20 July 2020; Accepted: 19 January 2021;

Published: 12 February 2021.

Edited by:

Eliane Kobayashi, McGill University, CanadaReviewed by:

Jose F. Tellez-Zenteno, University of Saskatchewan, CanadaVeriano Alexandre, University of São Paulo, Brazil

Copyright © 2021 Nozaki, Fujimoto, Yamazoe, Niimi, Baba, Yamamoto, Sato, Enoki and Okanishi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ayataka Fujimoto, YWZ1amltb3Rvc2NpZW5jZWFjYWRlbXlAZ21haWwuY29t

Toshiki Nozaki

Toshiki Nozaki Ayataka Fujimoto

Ayataka Fujimoto Tomohiro Yamazoe

Tomohiro Yamazoe Keiko Niimi

Keiko Niimi Shimpei Baba

Shimpei Baba Takamichi Yamamoto

Takamichi Yamamoto Hideo Enoki

Hideo Enoki Tohru Okanishi

Tohru Okanishi