- 1Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, College of Medicine and Philippine General Hospital, University of the Philippines Manila, Manila, Philippines

- 2Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, St. Luke's Medical Center, Taguig, Philippines

- 3Department of Clinical Epidemiology, College of Medicine, University of the Philippines Manila, Manila, Philippines

- 4Department of Neurosciences, College of Medicine and Philippine General Hospital, University of the Philippines Manila, Manila, Philippines

Background: Despite being known abroad as a viable alternative to face-to-face consultation and therapy, telerehabilitation has not fully emerged in developing countries like the Philippines. In the midst of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, wherein social distancing disrupted the in-clinic delivery of rehabilitation services, Filipinos attempted to explore telerehabilitation. However, several hindrances were observed especially during the pre-implementation phase of telerehabilitation, necessitating a review of existing local evidences.

Objective: We aimed to determine the challenges faced by telerehabilitation in the Philippines.

Method: We searched until March 2020 through PubMed, Scopus, Embase, Cochrane Library, and HeRDIN for telerehabilitation-related publications wherein Filipinos were involved as investigator or population. Because of the hypothesized low number of scientific outputs on telerehabilitation locally, we performed handsearching through gray literature and included relevant papers from different rehabilitation-related professional organizations in the Philippines. We analyzed the papers and extracted the human, organizational, and technical challenges to telerehabilitation or telehealth in general.

Results: We analyzed 21 published and 4 unpublished papers, which were mostly reviews (8), feasibility studies (6), or case reports/series (4). Twelve out of 25 studies engaged patients and physicians in remote teleconsultation, teletherapy, telementoring, or telemonitoring. Patients sought telemedicine or telerehabilitation for general medical conditions (in 3 studies), chronic diseases (2), mental health issues (2), orthopedic problems (2), neurologic conditions (1), communication disorders (1), and cardiac conditions (1). Outcomes in aforementioned studies mostly included telehealth acceptance, facilitators, barriers, and satisfaction. Other studies were related to telehealth governance, legalities, and ethical issues. We identified 18 human, 17 organizational, and 18 technical unique challenges related to telerehabilitation in the Philippines. The most common challenges were slow internet speed (in 10 studies), legal concerns (9), and skepticism (9).

Conclusion: There is paucity of data on telerehabilitation in the Philippines. Local efforts can focus on exploring or addressing the most pressing human, organizational, and technical challenges to the emergence of telerehabilitation in the country.

Introduction

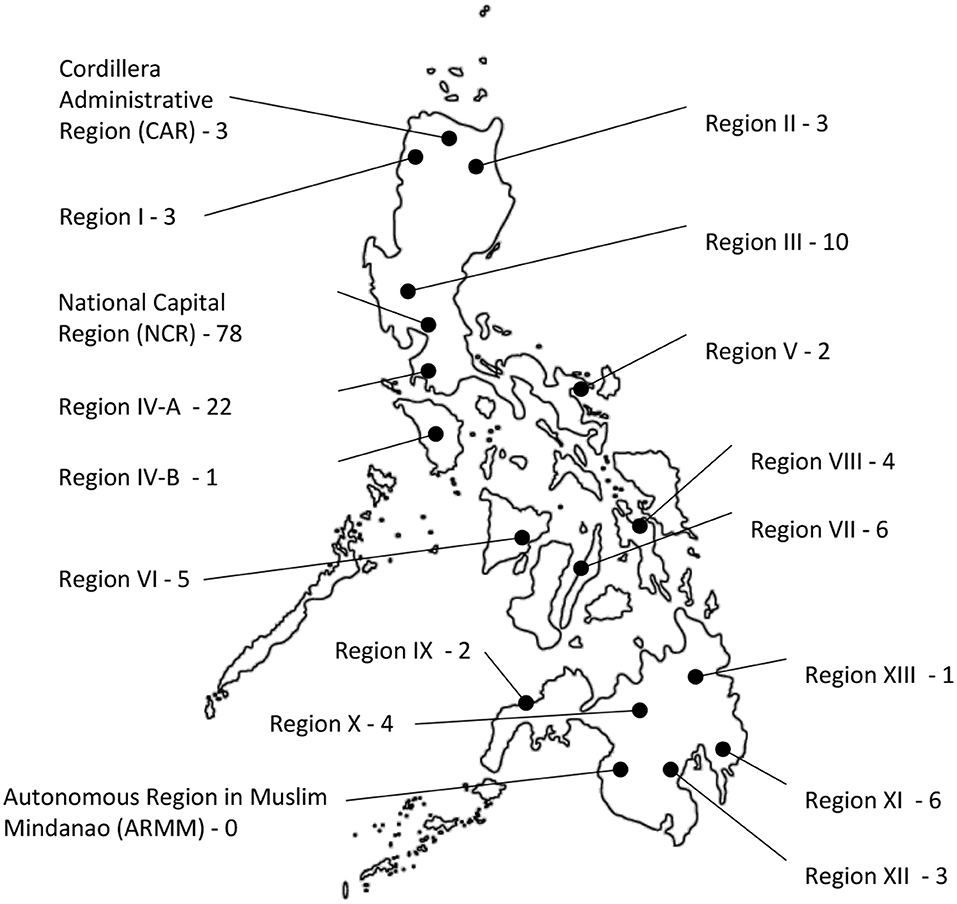

Located in Southeast Asia, the Republic of the Philippines consists of an archipelago of 7,641 islands with a land area of more than 300,000 km2 (1). The country is divided into three large groups of islands, namely, Luzon, Visayas, and Mindanao, and into 17 administrative regions (Figure 1) (2, 3). The Philippine National Statistics Office estimated that the total population in the country would reach 110 million in 2020 (4). As of writing, the country has a gross national income per capita of 3,830 USD and remains to be a lower-middle-income economy according to The World Bank (5, 6). The geographical landscape, administrative organization, and growing imbalance between population and resources are among the reasons that contribute to the difficult distribution of healthcare services in the Philippines (7).

Figure 1. Geographical landscape of the Philippines divided into 17 administrative regions, each with a corresponding number of physiatrists in their place of primary practice.

Of the estimated 1 billion persons with disabilities (PWD) worldwide, 80% come from low- and middle-income countries (8). Based on the 2017 Global Burden of Disease Study, the three leading causes of years lived with disability (YLDs) are low back pain, headache, and depression (9). The World Health Organization states that the total number of YLDs globally is “linked to health conditions for which rehabilitation is beneficial” (10). Rehabilitation is effective in improving or maintaining the functional independence and quality of life of PWD (8, 10). Despite limited reliable data documenting the need for rehabilitation in low- and middle-income countries, unique local experiences can attest to the prevailing unmet needs of the people amidst meager resources (11).

Telemedicine is the delivery of healthcare services through information and communications technology (ICT) to a different, often distant, site (12). As a telemedicine subset, telerehabilitation (telerehab) is an emerging technology that uses electronic means in remotely conducting evaluation, consultation, therapy, and monitoring to provide rehabilitation care for patients in various locations, such as home, community, nearby health facility, and workplace (11–13). Despite its growing body of literature and scope of services in other, mostly developed, countries, telerehabilitation continues to face challenges or barriers to its emergence in less-developed countries like the Philippines, albeit its practical use to address the widening gap between the supply of and demand for rehabilitation services especially during unprecedented times like the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, wherein face-to-face access to rehabilitation services is hampered (14). In this review, we gathered evidences of previous local attempts at telerehabilitation along with other papers that could help us determine the human, organizational, and technical challenges that beset the emergence of telerehabilitation in the country.

Methods

This review employed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) consensus statements (15).

Criteria for Study Selection

We considered studies based on the following inclusion criteria: (a) study investigator or population included Filipinos residing in the Philippines; and (b) intervention or topic included any telecommunication technology or process related to the remote delivery of medical or rehabilitation services (i.e., consultation, therapy, mentoring, and monitoring). Studies on telemedicine that focused on other specializations, such as dermatology, internal medicine, ophthalmology, pathology, or radiotherapy, were excluded. There was no restriction to the study design and year of publication or completion. Papers written in either English or Filipino were included, and those whose full text could not be accessed were not excluded to increase yield.

Search Methods and Data Analysis

We searched the following electronic healthcare databases until March 2020 for relevant studies: MEDLINE by PubMed, Embase, Scopus, Cochrane Library, and Health Research and Development Information Network (HeRDIN), which is the Philippines' national repository of local studies. Both Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and free search terms were used as follows: (“Telemedicine”[Mesh] OR “Telerehabilitation”[Mesh] OR “Remote Consultation”[Mesh] OR “Telenursing”[Mesh] OR telehealth OR telemedicine OR telerehabilitation OR telerehab OR teleneurorehabilitation OR teleconsultation OR teletherapy OR telepractice OR telepsychology OR telenursing) AND (“Philippines”[Mesh] OR Philippine*).

Due to hypothesized limited number of relevant publications from the Philippines, handsearching was done through the gray literature of different local rehabilitation professional organizations, namely, the Philippine Academy of Rehabilitation Medicine (PARM), the Philippine Physical Therapy Association (PPTA), the Philippine Academy of Occupational Therapists, Inc. (PAOT), the Philippine Association of Speech Pathologists (PASP), the Psychological Association of the Philippines (PAP), the Association of Filipino Prosthetists and Orthotists (AFPO), and the Philippine Nurses Association, Inc. (PNA). We contacted members or representatives from aforementioned organizations through text message, phone call, or email to request for relevant information.

We screened the titles and abstracts identified from the search. Relevant articles were obtained in full text (if available) and considered eligible if we could derive the following data for analysis: lead author, date of publication or completion, research design, population/target audience/problem identified, telemedicine or telerehabilitation method/concept, outcomes, and challenges to telemedicine or telerehabilitation cited in the results or discussion part. The challenges or barriers were identified, grouped together when applicable, and categorized according to unique human, organizational, and technical factors, based on consensus among study authors.

Results

Characteristics of Included Studies

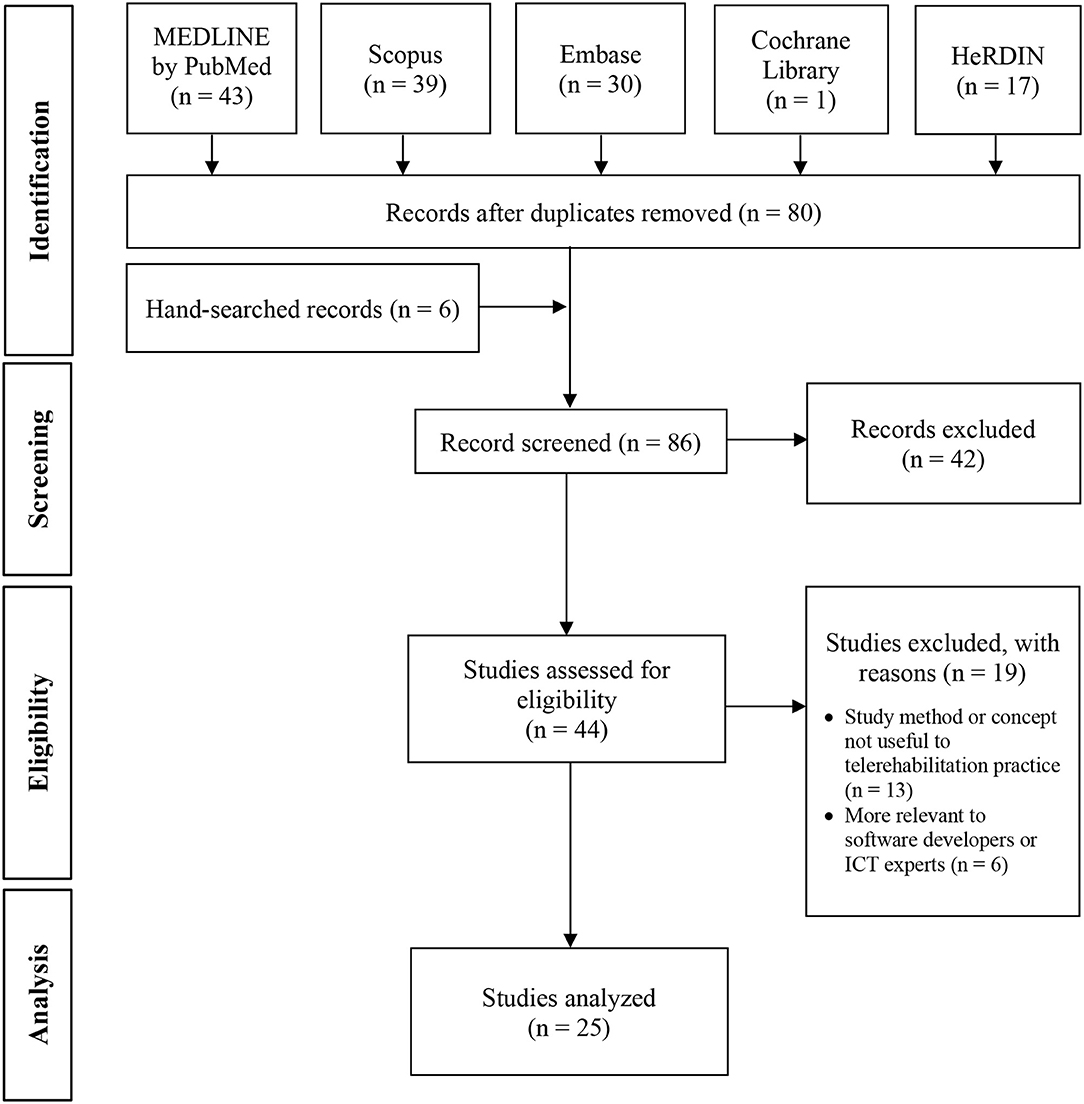

A total of 130 documents were identified from electronic databases and 6 from handsearching (Figure 2). Fifty duplicates were discarded. Out of 86 records screened, 42 were excluded and the rest were assessed for eligibility. Nineteen articles were further excluded because of lack of relevant information. Twenty-five studies were finally analyzed.

Figure 2. Flow diagram of study inclusion. HeRDIN, Health Research and Development Information Network; ICT, Information and communications technology.

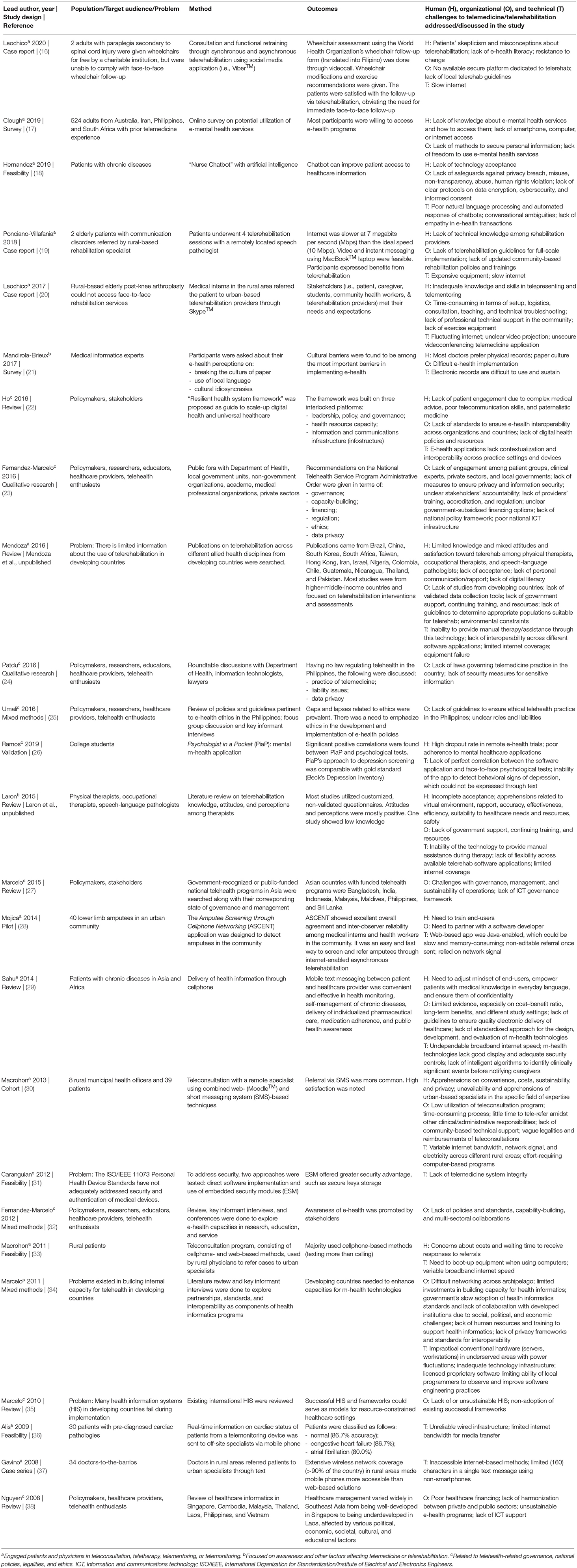

Table 1 presents the study design, population, intervention, comparator (if any), outcomes, and challenges related to telerehabilitation of the 25 included studies (21 published and 4 unpublished). The earliest publication was in 2008, while the latest completed study was in early 2020. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics and Acta Medica Philippina were the most common journals (four studies each). There were eight review papers, six feasibility studies, and four case reports/series among other research designs, which were largely observational. Twelve out of 25 studies engaged patients from remote areas to access healthcare services or information in teleconsultation, teletherapy, telementoring, or telemonitoring. Three studies involved patients with general medical conditions (30, 33, 37), while other studies involved patients with chronic diseases (18, 29), mental health issues (17, 26), orthopedic problems (20, 28), neurologic conditions (16), communication disorders (19), and cardiac disease (36).

Table 1. Studies relevant to telerehabilitation with Filipinos as study lead author, co-author, or population.

Teleconsultation meant that a patient consulted with a remote physician (16, 29). Teletherapy meant that a patient received instructions and home exercises demonstrated or supervised by a remote therapist (19, 20). There was one local study that involved physiatrists, physical therapists, occupational therapists, psychologists, and rehabilitation nurses in multi-disciplinary telerehabilitation sessions with a remote community (20). Another study involved speech-language pathologists (19), while two studies involved psychologists (17, 26). Telementoring meant that a remote specialist gave expert advice to a rural physician or healthcare worker co-located with a patient (20, 30, 33, 37). Telemonitoring meant that a gadget or web-based application facilitated asynchronous remote transmission of health-related information or patient reminders (17, 18, 28, 36). The most common electronic methods of conducting telerehabilitation (i.e., teleconsultation, teletherapy, telementoring, or telemonitoring) used in the local studies were mobile text messaging or short messaging system (SMS) (29, 30, 33, 37), followed by videocall and instant messaging through available social media platforms, such as Viber™ (16), Skype™ (20), or FaceTime™ (19). Two studies conducted teleconsultations through combined web- (i.e., Moodle™) and SMS-based services (30, 33). In general, positive experiences were noted from patients and rural physicians. The concerns raised, however, were mostly related to internet speed and data privacy issues.

The rest of the studies were related to telerehabilitation acceptance (Laron et al., unpublished; Mendoza et al., unpublished), telehealth-related governance (22, 32, 34, 35, 38), national programs or policies (23, 24, 27), legal issues (24), data privacy and security concerns (24, 31, 39) and ethical dilemmas (24, 25). Majority of the authors of these papers were affiliated with the National Telehealth Center of the National Institutes of Health at the University of the Philippines Manila. It was found that no Philippine law specific to telehealth has been approved yet according to Patdu and Tenorio (24). Nonetheless, there were initial efforts to lobby for telehealth by addressing funding, legal, ethical, and administrative challenges (23, 24, 32, 40).

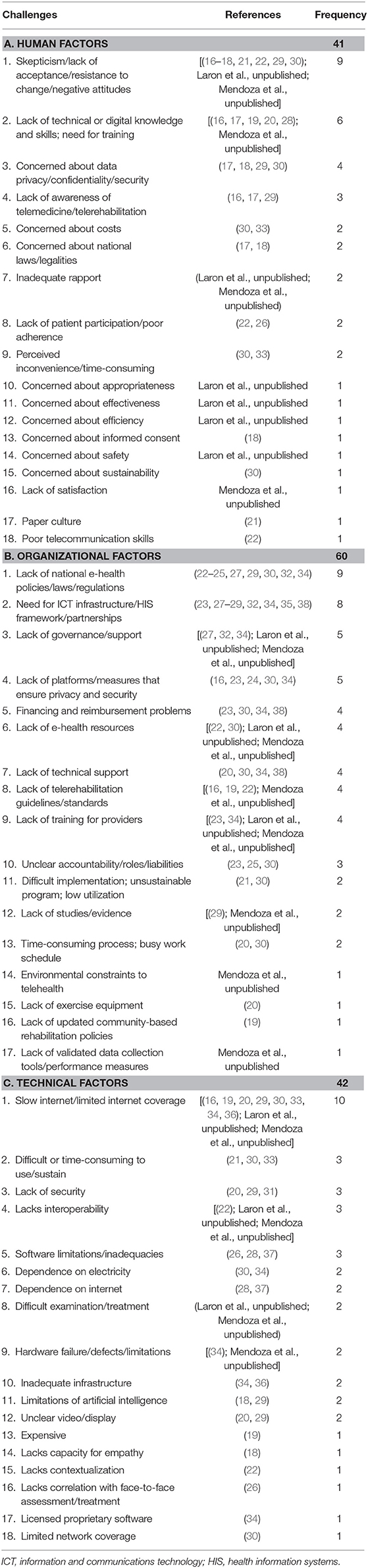

Challenges to Telerehabilitation

While Table 1 contains the human, organizational, and technical challenges cited in each study, Table 2 groups together similar challenges and organizes them into these three categories in order of frequency. In terms of human factors, the most commonly discussed challenges in the included studies were lack of acceptance of telehealth among stakeholders (in 9 studies), lack of knowledge and skills needed in e-health (6), and apprehensions related to data privacy (4). Among the organizational factors, which account for the highest percentage (42%) of the total frequency of citations of identified barriers, the most pressing were the lack of national e-health policies or laws (in 9 studies), health information systems framework (8), governance (5), and data privacy measures (5). Among all individual factors across categories, the internet was the overall number 1 challenge to telehealth in the Philippines, as mentioned in at least 10 studies.

Table 2. Frequency of human, organizational, and technical challenges to telerehabilitation in the Philippines cited in included studies.

Since human factors pertain to internal challenges (or within the person) (41), majority of those listed in Table 2A are interrelated with one another and may contribute to skepticism. Several studies have evaluated or attempted to address the lack of awareness and acceptance of telemedicine among stakeholders. Research fora, stakeholders' meetings, campaigns, and conferences conducted by Fernandez-Marcelo et al. in 2012 stimulated awareness of telehealth in a wider scale locally (32). The National Telehealth Service Program of the Department of Health was an important milestone in spreading telehealth awareness in rural areas, as shown by Macrohon and Cristobal (30, 33) and Gavino et al. (37). Local studies by Leochico and Mojica (20), Leochico and Valera (16), and Mojica et al. (28) in the Philippine General Hospital sprung awareness of telerehabilitation in particular. Two unpublished reviews found positive attitudes and limited experience with telerehabilitation among allied rehabilitation professionals in developing countries (Laron et al., unpublished). However, no published study related to telerehabilitation knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions among healthcare professionals was found from the Philippines. The study by Mandirola-Brieux et al. stated that cultural factors played a role in the acceptance of e-health programs (21). A systematic review on the role of telehealth in African and Asian countries showed that mobile text messaging was the most commonly accepted telehealth method among patients with chronic diseases (29).

There were several factors that were classified into more than one category, depending on the context in which the factor was discussed in individual studies. For instance, challenges related to national laws and guidelines, albeit more commonly discussed as an organizational factor, were contributory to human factors (i.e., apprehensions and various concerns). Meanwhile, issues on data privacy or security were listed under each category. Another recurring theme across all categories was related to technical aspect of e-health, cited as lack of digital knowledge and skills (under human factors), lack of technical support and training (under organizational factors), and technologies that were difficult to use, along with software and hardware issues (under technical factors).

Discussion

Our study found 53 unique, albeit interrelated, challenges in the literature that could affect the emergence of telerehabilitation in the Philippines. This review was driven by the difficulties experienced first-hand by the authors during the pre-implementation and implementation periods of telerehabilitation in local private and public healthcare settings in response to COVID-19. Probably similar to most developing countries without pre-existing telerehabilitation guidelines, rehabilitation providers in the Philippines were generally unprepared and apprehensive to adopt telerehabilitation in their practice. Evidences in this review helped us name the felt barriers to telerehabilitation and telehealth in general and categorized them into human, organizational, and technical factors in order of frequency. Overall, organizational factors accounted for the highest number of citations similar to a previous systematic review (42), while the most commonly cited specific factor across all categories was internet connection, as experienced in low- or middle-income countries (43).

Telerehabilitation literature in the Philippines is limited to feasibility studies and case reports. Despite scarce local evidence and experience, telerehab was deemed feasible even before the pandemic to perform remote teleconsultation, teletherapy, telementoring, or telemonitoring mostly for indigent patients in rural areas. As of writing, however, no local telerehabilitation document exists to operationally define various interchangeable terms, such as telehealth, telemedicine, telerehabilitation, teletherapy, telepractice, and telecare among many others used in the different rehabilitation disciplines. More so, there is no guideline on telerehabilitation principles, scope of services, procedure, and regulations that can be applicable across various rehabilitation professional organizations in the country.

Several success stories of national telerehabilitation programs abroad can inspire the eventual emergence of telerehabilitation in the Philippines. For instance, Canada and Australia use telerehabilitation to enhance access across vast geographical landscapes and minimize economic barriers by reducing travel time and costs (44, 45). Meanwhile, India, a lower-middle-income country (6), has a teleneurorehabilitation program to remotely provide cost-effective services amidst limited medical resources (46). Each country that has adopted telerehabilitation even before the pandemic acts according to the needs of its people and healthcare system.

The rehabilitation needs of the growing population from all over the Philippine archipelago cannot always be addressed face to face because of the barriers of distance, time, costs, manpower, and resources. Center-based rehabilitation services are limited, with more than 50% of the facilities located in urban areas of the National Capital Region (NCR) (47). There are only 216 fellows of good standing recognized by the Philippine Academy of Rehabilitation Medicine, 78 of whom have their primary practice in NCR (Figure 1) (47). Among physical therapists (PTs), there are 5,327 members of the Philippine Physical Therapy Association out of the 14,610 licensed PTs (48). Meanwhile, there are 2,985 occupational therapists, 673 speech-language pathologists, and 53 prosthetists–orthotists in the country (49, 50). Included in these numbers are those who might have migrated abroad, changed career, or retired. The greatest proportion of rehabilitation workforce remaining in the Philippines is based in Luzon (51).

Various local rehabilitation services, such as community-based programs, have been in place to support PWD throughout the country. However, efforts to empower rural communities and PWD have been hampered by several challenges, such as low accessibility, high costs, low utilization, and low sustainability (52). Amidst social distancing due to COVID-19, face-to-face rehabilitation might not adequately and safely cope with the continuing demand of PWD. A potentially viable solution is telerehabilitation, but it is also not without challenges.

In line with the Philippine e-Health Systems and Services Act, feasibility and cost-effectiveness studies should be done prior to implementation of telehealth-related programs in healthcare facilities (53). In addition, awareness campaigns, workforce training, capacity-building, and policy-updating are also important measures to ensure sustainable programs (23, 32). In relation to local telerehabilitation experience, however, these crucial steps were bypassed during the COVID-19 pandemic to urgently come up with interim guidelines.

When planning a telerehabilitation program, it should be emphasized that guidelines vary from one healthcare setting to another, depending on human, organizational, and technical factors. First, human (internal) factors include telerehabilitation awareness, acceptance, readiness, knowledge, and skills [Laron et al., unpublished; (41)]. Local studies on these interrelated human factors among different stakeholders (i.e., patient, family or caregiver, healthcare provider, policymakers, third-party payers) are recommended. Second, to address organizational (external) factors, the following are recommended: lobbying for administrative support and funding, formulation of best practice guidelines, work reorganization, agreement on payment schemes and reimbursements, and measures to protect data privacy and safety of stakeholders (23, 27, 53). Lastly, technical factors should be addressed by improving the quantity and quality of tangible (i.e., telerehabilitation equipment and technical support) and intangible e-health resources (i.e., technical skills, information and communications framework or “infostructure”) (22). Understanding and addressing such factors are key to successful telerehabilitation initiatives.

As evident during the pandemic, videoconferencing has become relatively more feasible locally compared to earlier years. During the first quarter of 2017, Akamai, a recognized cloud data network monitoring internet traffic, reported that the Philippines had the largest quarterly increase in internet speed at 26% in the Asia-Pacific region (54). Still, however, the country had the lowest average connection speed at 5.5 megabits per second (Mbps), compared to the global speed of 7.2 Mbps (54). In addition to its slow speed, the internet in the Philippines has not always been cheap with mobile cellular and fixed broadband services amounting to 22.24 and 51.59 USD per month, respectively (55). Although the country has been working on national reforms toward universal internet access (56), we have yet to see improvements in the technology to facilitate e-health access.

As strengths of this study, we were able to contribute to the limited knowledge of telerehabilitation facilitators and barriers in a developing country. We structured our paper following the PRISMA guidelines. We attempted to increase the number of included studies by handsearching of gray literature. We analyzed 25 studies and extracted the human, organizational, and technical challenges that might be applicable not only in the Philippines but also in other resource-limited countries. In terms of limitations, a more thorough handsearching of gray literature from other institutions across the archipelago and inclusion of studies from other developing countries could have been done. A more objective screening process could have also increased the number of analyzed studies. Although we attempted to control for this limitation by having more than one reviewer screening each study, potential bias toward rehabilitation medicine has excluded studies from other specialties, whose experiences could have also been rich data sources on telehealth challenges. Another factor that might have influenced our results was individual judgment in analyzing the studies and extracting the barriers and categorizing them into human, organizational, and technical factors. Nonetheless, we tried to address this limitation by consensus meetings. Lastly, the challenges cited in this paper were solely based on secondary data; hence, future large-scale descriptive and analytical studies gathering primary data are recommended.

As more stakeholders recognize the value of telerehabilitation, catalyzed by the COVID-19 pandemic, more efforts can be made to address the various challenges besetting the emergence of telerehabilitation in the country. Researches on telerehabilitation and policy changes through Delphi method can help us respond better to the World Health Organization's Rehabilitation 2030 Call to Action to improve access to rehabilitation services (10, 42, 57). A lot of work has yet to be done to address the human, organizational, and technical challenges to telerehabilitation, but we can be guided by existing local and international evidences, along with experts in telehealth and medical informatics, to avoid costly and time-consuming trial-and-error attempts.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author Contributions

CL conceived the idea and wrote the initial drafts and final revisions of the manuscript. AE, SI, and JM made substantial contributions in the content and format of the revised versions. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Dr. Paul Matthew Jiao for designing Figure 1 and contact persons from the different local rehabilitation professional organizations for contributing to our data. Assistance with the publication fee for this open-access article was provided by the University of the Philippines Manila.

References

2. Bravo L, Roque VG, Brett J, Dizon R, L'Azou M. Epidemiology of dengue disease in the Philippines (2000–2011): a systematic literature review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. (2014) 8:e3027. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003027

3. Library of Congress - Federal Research Division. Country Profile: Philippines. (2006). Available online at: https://www.loc.gov/rr/frd/cs/profiles/Philippines-new.pdf (accessed March 31, 2020).

4. Philippine Statistics Authority. Projected Population, by Age Group, Sex, and by Single-Calendar Year Interval, Philippines: 2010 - 2020 (medium assumption). (2010). Available online at: https://psa.gov.ph/sites/default/files/attachments/hsd/pressrelease/Table-4_9.pdf (accessed March 29, 2020).

5. The World Bank Group. Philippines. (2019) Available online at: https://data.worldbank.org/country/philippines?view=chart (accessed March 29, 2020).

6. The World Bank Group. World Bank Country and Lending Groups. (2020). Available online at: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups (accessed March 29, 2020).

7. Jamora RDG, Miyasaki JM. Treatment gaps in Parkinson's disease care in the Philippines. Neurodegen Dis Manag. (2017) 7:245–51. doi: 10.2217/nmt-2017-0014

8. Iemmi V, Gibson L, Blanchet K, Kumar KS, Rath S, Hartley S, et al. Community-based rehabilitation for people with disabilities in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Campbell Syst Rev. (2015) 11:1–177. doi: 10.4073/csr.2015.15

9. James SL, Abate D, Abate KH, Abay SM, Abbafati C, Abbasi N, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. (2018) 392:1789–858. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32279-7

10. World Health Organization. Rehabilitation 2030 a Call for Action: The Need to Scale up Rehabilitation. (2017). p. 1–9. Available online at: https://www.who.int/disabilities/care/NeedToScaleUpRehab.pdf (accessed March 29, 2020).

11. World Health Organization. Rehabilitation in Health Systems: Guide for Action. (2019). Available online at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/325607/9789241515986-eng.pdf?ua=1 (accessed March 31, 2020).

12. Seelman KD, Hartman LM. Telerehabilitation: policy issues and research tools. Int J Telerehabil. (2009) 1:47–58. doi: 10.5195/IJT.2009.6013

13. Brennan D, Tindall L, Theodoros D, Brown J, Campbell M, Christiana D, et al. A blueprint for telerehabilitation guidelines. Int J Telerehabil. (2010) 2:31–4. doi: 10.5195/IJT.2010.6063

14. Boldrini P, Bernetti A, Fiore P. Impact of COVID-19 outbreak on rehabilitation services and Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine (PRM) physicians' activities in Italy: an official document of the Italian PRM society. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. (2020) 56:316–18. doi: 10.23736/S1973-9087.20.06256-5

15. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. (2009) 6:e1000100. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100

16. Leochico CF, Valera M. Follow-up consultations through telerehabilitation for wheelchair recipients with paraplegia: a case report. Spinal Cord Ser Cases. (2020) 6:58. doi: 10.1038/s41394-020-0310-9

17. Clough BA, Zarean M, Ruane I, Mateo NJ, Aliyeva TA, Casey LM. Going global: do consumer preferences, attitudes, and barriers to using e-mental health services differ across countries? J Ment Heal. (2019) 28:17–25. doi: 10.1080/09638237.2017.1370639

18. Hernandez JPT. Network diffusion and technology acceptance of a nurse chatbot for chronic disease self-management support: a theoretical perspective. J Med Investig. (2019) 66:24–30. doi: 10.2152/jmi.66.24

19. Villafania JAP. Feasibility of telerehabilitation in the service delivery of speech-language pathology in the Philippines. In: 11th Pan-Pacific Conference of Rehabilitation (Hong Kong) (2018). Available online at: http://pasp.org.ph/Abstracts (accessed March 31, 2020).

20. Leochico CF, Mojica JA. Telerehabilitation as a teaching-learning tool for medical interns. PARM Proc. (2017) 9:39–43.

21. Mandirola Brieux H-F, Benitez S, Otero C, Luna D, Masud JHB, Marcelo A, et al. Cultural problems associated with the implementation of eHealth. Stud Health Technol Inform. (2017) 245:1213. doi: 10.3233/978-1-61499-830-3-1213

22. Ho K, Al-Shorjabji N, Brown E, Zelmer J, Gabor N, Maeder A, et al. Applying the resilient health system framework for universal health coverage. Stud Health Technol Inform. (2016) 231:54–62. doi: 10.3233/978-1-61499-712-2-54

23. Fernandez-Marcelo PG, Ongkeko AM, Sylim PG, Evangelista-Sanchez AM, Santos AD, Fabia JG, et al. Formulating the national policy on telehealth for the Philippines through stakeholders' involvement and partnership. Acta Med Philipp. (2016) 50:247–63.

24. Patdu ID, Tenorio AS. Establishing the legal framework of telehealth in the Philippines. Acta Med Philipp. (2016) 50:237–46.

25. Umali MJ, Evangelista-Sanchez AM, Lu JL, Ongkeko AM, Sylim PG, Santos AD, et al. Elaborating and discoursing the ethics in eHealth in the Philippines: recommendations for health care practice and research. Acta Med Philipp. (2016) 50:215–22.

26. Ramos RM, Cheng PGF, Jonas SM. Validation of an mhealth app for depression screening and monitoring (psychologist in a pocket): correlational study and concurrence analysis. JMIR mHealth uHealth. (2019) 7:e12051. doi: 10.2196/12051

27. Marcelo A, Ganesh J, Mohan J, Kadam DB, Ratta BS, Kulatunga G, et al. Governance and management of national telehealth programs in Asia. Stud Health Technol Inform. (2015) 209:95–101. doi: 10.3233/978-1-61499-505-0-95

28. Mojica JA, Bundoc JR. Inter-observer reliability in the use of cellphone technology as a community-based limb loss screening tool for prosthesis use. PARM Proc. (2014) 6:45–50.

29. Sahu M, Grover A, Joshi A. Role of mobile phone technology in health education in Asian and African countries: a systematic review. Int J Electron Healthc. (2014) 7:269. doi: 10.1504/IJEH.2014.064327

30. Macrohon BC, Cristobal FL. The effect on patient and health provider satisfaction regarding health care delivery using the teleconsultation program of the Ateneo de Zamboanga University-School of Medicine (ADZU-SOM) in rural Western Mindanao. Acta Med Philipp. (2013) 47:18–22.

31. Caranguian LPR, Pancho-Festin S, Sison LG. Device interoperability and authentication for telemedical appliance based on the ISO/IEEE 11073 personal health device (PHD) standards. In: 2012 Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (San Diego, CA: IEEE), 1270–1273. doi: 10.1109/EMBC.2012.6346169

32. Fernandez-Marcelo PG, Ho BL, Faustorilla JF, Evangelista AL, Pedrena M, Marcelo A. Emerging eHealth directions in the Philippines. Yearb Med Inform. (2012) 7:144–52. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1639446

33. Macrohon BC, Cristobal FL. Rural healthcare delivery using a phone patch service in the teleconsultation program of the Ateneo de Zamboanga University School of Medicine in Western Mindanao, Philippines. Rural Remote Health. (2011) 11:1740. doi: 10.22605/RRH1740

34. Marcelo A, Adejumo A, Luna D. Health informatics for development: a three-pronged strategy of partnerships, standards, and mobile Health. Yearb Med Inform. (2011) 6:96–101. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1638745

35. Marcelo AB. Health information systems: a survey of frameworks for developing countries. Yearb Med Inform. (2010) 19:25–9. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1638684

36. Alis C, del Rosario C, Buenaobra B, Mar Blanca C. Lifelink: 3G-based mobile telemedicine system. Telemed e-Health. (2009) 15:241–7. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2008.0098

37. Gavino AI, Tolentino PAP, Bernal ABS, Fontelo P, Marcelo AB. Telemedicine via short messaging system (SMS) in rural Philippines. In: AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings. (2008). p. 952. Available online at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18998858 (accessed March 31, 2020).

38. Nguyen QT, Naguib RNG, Abd Ghani MK, Bali RK, Lee IM. An analysis of the healthcare informatics and systems in Southeast Asia: a current perspective from seven countries. Int J Electron Healthc. (2008) 4:184–207. doi: 10.1504/IJEH.2008.019792

39. Bitsch JÁ, Ramos R, Ix T, Ferrer-Cheng PG, Wehrle K. Psychologist in a pocket: Towards depression screening on mobile phones. Stud Health Technol Inform. (2015) 211:153–9. doi: 10.3233/978-1-61499-516-6-153

40. Macabasag RL, Magtubo KM, Marcelo PG. Implementation of telemedicine services in lower-middle income countries: lessons for the Philippines. J Int Soc Telemed eHealth. (2016) 4:1–11.

41. Leochico CFD. Adoption of telerehabilitation in a developing country before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. (2020). doi: 10.1016/j.rehab.2020.06.001. [Epub ahead of print].

42. Scott Kruse C, Karem P, Shifflett K, Vegi L, Ravi K, Brooks M. Evaluating barriers to adopting telemedicine worldwide: a systematic review. J Telemed Telecare. (2018) 24:4–12. doi: 10.1177/1357633X16674087

43. World Health Organization (WHO). Telemedicine: Opportunities and Developments in Member States: Report on the Second Global Survey on e-health. Global Observatory for e-health Series – Vol. 2. NLM classification W 26.5. ISBN 9789241564144. ISSN 2220-5462. Geneva (2010).

44. Hailey D, Roine R, Ohinmaa A, Dennett L. Evidence on the Effectiveness of Telerehabilitation Applications. Edmonton, AB: Institute of Health Economics (IHE) (2010). Available online at: http://www.ihe.ca/advanced-search/evidence-on-the-effectiveness-of-telerehabilitation-applications (accessed March 31, 2020).

45. Russell TG. Telerehabilitation: a coming of age. Aust J Physiother. (2009) 55:5–6. doi: 10.1016/s0004-9514(09)70054-6

46. Khanna M, Gowda GS, Bagevadi VI, Gupta A, Kulkarni K, Shyam RPS, et al. Feasibility and utility of teleneurorehabilitation service in India: Experience from a quaternary center. J Neurosci Rural Pract. (2018) 09:541–4. doi: 10.4103/jnrp.jnrp_104_18

47. Mojica JA, Ang-Muñoz CD, Bundoc JR, Leochico CF, Ignacio S. Capacity assessment of healthcare facilities in the Philippines on provision of rehabilitation medicine services for stroke and low back pain. PARM Proc. (2019) 11:4–15.

48. World Confederation for Physical Therapy. WCPT Country Profile 2019: Philippines. Available online at: https://world.physio/sites/default/files/2020-06/CountryProfile2019_AWP_Philippines_0.pdf (accessed March 31, 2020).

49. World Federation of Occupational Therapists. WFOT Human Resources Project 2014. (2014). Available online at: https://www.aota.org/~/media/Corporate/Files/Practice/Intl/2014-Human-Resource-Project.PDF (accessed March 28, 2020).

50. Philippine Association of Speech Pathologists. Directory of Members of the Philippine Association of Speech Pathologists. Available online at: http://pasp.org.ph/directory (accessed March 28, 2020).

51. Carandang K, Delos Reyes R. Workforce Survey 2017: Working Conditions and Salary Structure of Occupational Therapists Working in the Philippines Survey. (2018). Available online at: http://www.tinyurl.com/paotworkforce2017 (accessed March 31, 2020).

53. The Senate and The House of Representatives of the Congress of the Philippines. Philippine Ehealth Systems and Services Act. (2019) Available online at: http://www.congress.gov.ph/legisdocs/basic_17/HB07153.pdf (accessed April 2, 2020).

54. Akamai. Akamai's State of the Internet Q1 2017 Report. (2017). Available online at: https://www.akamai.com/fr/fr/multimedia/documents/state-of-the-internet/q1-2017-state-of-the-internet-connectivity-report.pdf (accessed March 31, 2020).

55. Albert JRG, Serafica RB, Lumbera B. Examining Trends in the ICT Statistics: How Does the Philippines Fare in ICT? Quezon City, Philippines (2016) Available online at: https://dirp4.pids.gov.ph/websitecms/CDN/PUBLICATIONS/pidsdps1616.pdf

56. Alampay E, Alampay JG, Alegre A, Bitanga FJ. Towards Universal Internet Access in the Philippines. (2007) Available online at: http://www.infomediary4d.com/wp-content/uploads/Infomediaries-Philippines.pdf (accessed April 4, 2020).

Keywords: telemedicine, telerehabilitation, barriers, rehabilitation medicine, healthcare delivery, developing country

Citation: Leochico CFD, Espiritu AI, Ignacio SD and Mojica JAP (2020) Challenges to the Emergence of Telerehabilitation in a Developing Country: A Systematic Review. Front. Neurol. 11:1007. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.01007

Received: 24 April 2020; Accepted: 31 July 2020;

Published: 08 September 2020.

Edited by:

Paolo Tonin, Sant'Anna Institute, ItalyReviewed by:

Stefano Carda, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Vaudois (CHUV), SwitzerlandAlessandro Giustini, Istituto di Riabilitazione Santo Stefano, Italy

Copyright © 2020 Leochico, Espiritu, Ignacio and Mojica. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Carl Froilan D. Leochico, Y2RsZW9jaGljb0B1cC5lZHUucGg=

Carl Froilan D. Leochico

Carl Froilan D. Leochico Adrian I. Espiritu

Adrian I. Espiritu Sharon D. Ignacio1,2

Sharon D. Ignacio1,2