95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Neurol. , 03 February 2017

Sec. Movement Disorders

Volume 8 - 2017 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2017.00018

This article is part of the Research Topic Unmet needs in dystonia View all 9 articles

Alberto Albanese1,2*

Alberto Albanese1,2*

Literary reports on dystonia date back to post-Medieval times. Medical reports are instead more recent. We review here the early descriptions and the historical establishment of a consensus on the clinical phenomenology and the diagnostic features of dystonia syndromes. Lumping and splitting exercises have characterized this area of knowledge, and it remains largely unclear how many dystonia types we are to count. This review describes the history leading to recognize that focal dystonia syndromes are a coherent clinical set encompassing cranial dystonia (including blepharospasm), oromandibular dystonia, spasmodic torticollis, truncal dystonia, writer’s cramp, and other occupational dystonias. Papers describing features of dystonia and diagnostic criteria are critically analyzed and put into historical perspective. Issues and inconsistencies in this lumping effort are discussed, and the currently unmet needs are critically reviewed.

Dystonia has been defined by Denny-Brown as “the most striking and grotesque of all neurological disorders” (1). Therefore, it is not surprising that artists have reported the feature of dystonia before doctors were able to categorize its striking phenomenology. Cervical dystonia, the most prevalent dystonia type, has been the object of some famous literary portrayals. The first artistic description dates back to 1315, when Dante Alighieri reported having seen fortune tellers and diviners punished in the Inferno (Circle eight, Bolgia four), by the divine law or retaliation for having looked too far forward, with their head twisted backwards (2):

And when I looked down from their faces, I saw

that each of them was hideously distorted

between the top of the chest and the line of jaw;

for the face was reversed on the neck, and they came on

backwards, starting backwards at their loins,

for to look before them was forbidden. Someone

sometime, in the grip of palsy may have been

distorted so, but never to my knowledge;

Rabelais (circa in 1532) introduced the French neologism torticollis (torty colly in the original old French). Into a similar infernal atmosphere, he described the healing of Epistemon, “who had his head cut off, was finely healed by Panurge, and brought news from the devils, and from the damned people in hell” … “Thus as they went seeking after him, they found him stark dead, with his head between his arms all bloody” … “Panurge took the head and held it warm foregainst his codpiece, that the wind might not enter into it. Eusthenes and Carpalin carried the body to the place where they had banqueted, not out of any hope that ever he would recover, but that Pantagruel might see it. … Then cleansed he his neck very well with pure white wine, and, after that, took his head, and into it synapised some powder of diamerdis, which he always carried about him in one of his bags. Afterwards he anointed it with I know not what ointment, and set it on very just, vein against vein, sinew against sinew, and spondyle against spondyle, that he might not be torticollis (for such people he mortally hated). This done, he gave it round about some fifteen or sixteen stitches with a needle that it might not fall off again; then, on all sides and everywhere, he put a little ointment on it, which he called resuscitative.”

Other artists have described focal dystonias, particularly cervical dystonia, but not as much the generalized cases, that may have appeared too severe to become a narrative subject.

It is of interest to follow the historical order by which different dystonia types were recognized and described. It is also remarkable to note how some fundamental clinical questions have remained actual, and for the most unanswered, until now.

Cervical dystonia has attracted early medical interest. Tulpius (3) gave one of the first descriptions of torticollis; he considered a contraction of the scalene muscles as the most common cause. A first classification was attempted by Heister (4), who distinguished “caput obstipum” from “collum obstipum,” a phenomenological distinction that has been recently proposed anew (5). A prominent role of the sternocleidomastoid muscle was later widely recognized and surgical sections of its tendons started being performed by orthopedic surgeons. A non-surgical approach, based on head repositioning under anesthesia followed by head bandage, later gained diffusion in France and abroad as an alternative to surgical ablations (6). This approach attracted a wide medical audience interested in the management of “muscular torticollis” (then distinguished from torticollis caused by scars or bone anomalies; Table 1). The monumental medical encyclopedia edited by Dr. Fabre reported: “It appears today that the majority of neck muscles may become the starting point of a permanent retraction and may also contribute to some type of head deviations” (7). The complex phenomenology of torticollis was also recognized: “the sternocleidomastoid is not the only muscle that may be involved; the majority of other cervical muscles may be involved, so to produce the attitude of torticollis either by their specific action or by a combined influence” (8). Torticollis became then a matter for neurologists. Pitres recognized that there was no pathognomonic sign to distinguish spasms of hysteric origin from the non-hysteric ones (9). The non-hysterical nature of torticollis was reinforced by the observation that patients with torticollis also had “functional spasms” in other body regions (10).

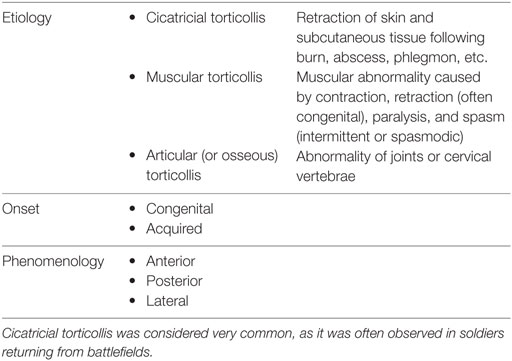

Table 1. Classification of cervical dystonia by the end of nineteenth century (11).

Generalized dystonia was listed for the first time by Gowers under the name of “tetanoid chorea,” one of the several choreatic disorders encompassing also senile chorea, maniacal chorea, functional chorea, and Sydenham’s chorea (12). He had probably also observed idiopathic generalized cases, but later defended that “tetanoid chorea” was a feature of Wilson’s disease (13).

Undoubtedly, 1911 is the founding year of generalized dystonia as an independent nosological entity. Hermann Oppenheim, probably the most famous German neurologist of the time, published the description of dystonia musculorm deformans (altered muscle tone causing deformities), a condition he observed in four unrelated Jewish children who came to Berlin to be seen by him (14). He also added a second Latin descriptor dysbasia lordotica progressiva (progressive gait difficulty with lordosis), as he noted the occurrence of pronounced and progressive lordosis in his patients. A similar phenomenology had been previously observed in a Jewish kindred by Theodor Ziehen, professor of psychiatry in Berlin, who asked his resident Markus Walter Schwalbe to write a dissertation on this peculiar phenomenology. Ziehen presented his observations in Berlin in December 1910 and published the family in 1911 as well (15). Finally, Edward Flatau and Wladyslaw Sterling described the same condition observed in two Polish Jews under the name of “progressive torsion spasm” in 1911 as well (16).

Unquestionably, Oppenheim’s publication is the most prominent of the three. Patient 1 described by Flatau and Sterling was also seen by Oppenheim himself, and Flatau and Sterling repeatedly mention Oppenheim’s seminal publication. Both Oppenheim and Flatau and Sterling underline the organic nature of the disease and reject Schwalbe–Ziehen’s label of hysterical disorder. Their reasoning is however different. Oppenheim considered the phenomenology of Schwalbe–Ziehen’s cases different from that of dystonia musculorum deformans he was describing. He reported: “I find profound differences between these observations and those of my own, also with respect to the account of this affliction given by Ziehen himself. Hence, Schwalbe describes choreiform and tic-like movements.” Flatau and Sterling, instead, used clinical arguments to reject the hysterical nature of the phenomenology they had observed. They reported: “The first boy we first saw in 1909 offered us great diagnostic difficulties. Some colleagues, to whom we presented the case in the hospital, thought of hysteria. We have, however, denied this diagnosis in a more precise analysis, and considered the case as an unknown form of spasm. The longer we have observed the patient, the deeper was the conviction that we were not dealing with any functional disease, but with a disease of its own” … “The clinical picture was so characteristic that when one of us saw the second case in his office, he immediately thought of his similarity with the first.”

The clinical descriptions in Flatau–Sterling publication are particularly interesting, probably because they have appeared later than Oppenheim’s publication. Oppenheim defended that: “the clonic jerks do indeed belong to the clinical picture,” “the hypotonia is a major element of the symptomatology,” and “the tonic cramps are very predominantly connected with the function of standing and walking.” Hence, he proposed to name the disease “dystonia” (i.e., abnormal muscle tone) or “dysbasia” (i.e., abnormal base while standing or walking). Flatau and Sterling reasoning led them to dispute this terminology. They stated: “With the name suggested by Oppenheim (Dysbasia lordotica progressiva and Dystonia musculorum deformans), we cannot be satisfied for the reason that in some, such as our two patients, the disease is as strong in the upper as in the lower extremities, and dysbasia is not the principal symptom. We have also shown that there is no hypotonia in our patients, and we also believe that the word ‘deformans’ contains something stable, which is not true in the case of the essentially mobile spasm.”

Numerous reports followed. In a review of all published cases, Mendel summarized the significant clinical data and introduced the expression “torsion dystonia” to indicate a specific nosologic entity distinguished from other types of involuntary movements, such as hysteria, double athetosis, chorea, and myoclonus (17). During the following decades, different types of hyperkinetic movements (including dystonia) were reported in patients with encephalitis lethargica, Wilson’s disease, or cerebral palsy (then called double athethosis). The issue whether dystonia was a disease entity or instead a syndrome of basal ganglia dysfunction with different possible causes arose. Dystonia became the topic of some dedicated symposia where similarities between focal and generalized dystonia types were mentioned. At the 95th Annual Meeting of the British Medical Association held in Edinburg in 1927, a session was devoted to the “existing confusion on involuntary movements.” Guillain there defended the view that torticollis was not a psychogenic condition (18). In 1929, a session of the Tenth French Congress of Neurology was devoted to “torsion spasms,” with lively discussions about their psychiatric vs. organic origin (19). This issue was gradually settled by the observation that torticollis and torsion spasms (initially defined as pseudo-parkinsonism) could be secondary to encephalitis lethargica (20). In 1940, the Association for Research in Nervous and Mental Diseases extensively discussed the phenomenology of dystonia, its similarity with athetosis, the related EMG reading, and the underlying pathology (21). According to Herz (21), the term dystonia musculorum deformans should be confined to the idiopathic form. He gave the following criteria for the clinical diagnosis of idiopathic dystonia: (a) selective systemic symptoms in the form of dystonic movements and postures; (b) gradual development, without recognizable etiological factors at the onset. He also distinguished early forms occurring shortly after birth, from the juvenile form with the onset between 5 and 15, and the late form after 15 years of age.

Notwithstanding these scholarly observations, torticollis and generalized dystonia were still considered two separate and distinct conditions. Craft neuroses (also called occupational spasms or trade palsies) were also considered a distinct group of “functional disorders which are characterized by a difficulty in performing specific coordinated movements of certain occupations” (22). The best known craft neuroses were writer’s cramp and telegraphists’ cramp.

Writer’s cramp was another medical condition known since 1700 from the work of Bernardino Ramazzini, the father of occupational medicine (23), who stated: “The diseases of persons incident to this work arise from three causes; firstly, constant sitting, secondly the perpetual motion of the hand in the same manner, and thirdly the attention and application of the mind. Constant writing considerably fatigues the hand and whole arm on account of the almost continual and almost tense tension of the muscles and tendons.” In the mid-nineteenth century, Duchenne (24) and Gowers (25) wrote extensively about writer’s cramp. Solly provided an early surgeon’s view and considered writer’s cramp a spinal cord disorder (26). The largest early series was published by Poore (27), whose classification was based on tenderness and measures of faradic response. A comprehensive monograph on telegraphists’ cramp was written by Cronbach (28), who described 17 cases which he had observed in Berlin.

Eye and facial spasms were a yet different condition. A notable artistic description of cranial dystonia was likely provided circa in 1558 by the vivid painting of an elderly woman made by Pieter Brueghel (29). The first medical description of blepharospasm was given in 1906 by a French ophthalmologist (30). Meige is credited to have described cases of blepharospasm and other cranial dystonias (31). Patients had predominantly symmetric dystonic spasms of facial muscles, sometimes associated with dystonic movements of other midline muscle groups. After the original description, little appeared in the literature until 1972, when there were reports of isolated oromandibular dystonia (32) and oromandibular dystonia with blepharospasm (an association then described with the eponym “Meige’s syndrome”) (33). Marsden later used the expression “Brueghel syndrome” to describe a large series of patients and noted that it usually started in the sixth decade with blepharospasm, oromandibular dystonia, or both. Meige’s syndrome later became the preferred expression (34).

Spasmodic dysphonia was probably first described by Traube in the second volume of his textbook (35) and later by Meige (36) and by Macdonald Critchley, who argued whether to call it “spastic” or “dystonic” dysphonia (37). These two terminologies have been used interchangeably until very recently.

The first glimpse to a possible connection among different focal dystonia syndromes was the observation that two patients with “spasmodic torticollis” also had “functional spasms” in other body regions, including the right thigh, the upper limb while writing (writer’s cramp) and the left foot (10). A second contribution toward lumping together different types of spasms came by the observations that ablative surgery was helpful in focal and generalized dystonia regardless of its etiology (38, 39).

Zeman et al. (40) summarized very neatly the features of idiopathic dystonia: “The chief symptoms are dystonic postures and dystonic movements. The latter are true hyperkinesias and are characterized by relatively slow, long-sustained, powerful, non-patterned, contorting activities of the axial and appendicular muscles. The muscles most commonly involved are those of the neck, trunk, and proximal portions of extremities. Involvement of unilateral muscle groups often results in bizarre torsion movements, hence the alternative term ‘torsion dystonia’ for the disease.” … “‘Dystonic posture’ is the term used if the end position of a dystonic movement is maintained for any length of time. Eventually this may lead to contracture deformities.” Zeman et al. (40) reviewed the published cases with autosomal dominant or recessive transmission and distinguished these from sporadic ones. They reported a four-generation family with autosomal dominant inheritance and so discussed phenotypic heterogeneity.

“Within this family there is a considerable variability of expressivity of the disease. For instance, V-14 shows symptoms of dystonia in a very mild form, manifested by temporary limping, torticollis and blepharospasm. At times this patient appears almost normal. On the other hand, three of his siblings are totally crippled and helpless. V-10 has neither spontaneous movements nor the typical dystonic posture. Yet, upon performing certain volitional movements, typical dystonic features can be easily elicited. Certainly in cases like these two, one could take the position that such manifestations do not justify the diagnosis of dystonia. Yet, it would be illogical to consider any other diagnosis in view of the fact that grandmother, father, siblings, and one child are so definitely affected by dystonia. Applying ‘Occam’s razor’ of scientific parsimony, it is certainly the most logical conclusion that this family exhibits ‘formes frustes’ as well as full-fledged cases of dystonia. Obviously, the strict diagnostic criteria as set forth by Herz (21) were not applied to the subject cases.” It was then recognized that “idiopathic torsion dystonia” is a genetic disorder with heterogeneous phenomenology, from focal to generalized within a same family.

The following years witnessed the development of stereotactic and functional neurosurgery, which was applied to dystonia as well as to Parkinson’s disease. At the same time, there were attempts to understand and classify the diverse causes of dystonia. Levodopa, the newly discovered treatment for Parkinson’s disease, was also tried in dystonia (41). Denny-Brown (42) did not contribute much to understanding the phenomenology of dystonia, although he attempted to distinguish dystonia occurring in Huntington’s chorea, athetosis, dystonia musculorum deformans, and parkinsonism. He described possible anatomical correlates of each of these dystonia syndromes; he also performed brain lesions in monkeys and called “dystonia” whatever postural phenomenon he could observe, including postural abnormalities associated with spastic hemiplegia (“cortical dystonia”).

In 1966, Jacob A. Brody, Chief of Epidemiology Branch at NINDS, and Irving S. Cooper, Head of Neurologic Surgery at St. Barnabas Hospital, discussed possible epidemiologic studies utilizing the large population of patients with neurological diseases seen at St. Barnabas Hospital over the years. During the course of their talks, Dr. Cooper mentioned that he had operated on approximately 200 patients with torsion dystonia. Dr. Roswell Eldridge, a trained medical geneticist, had just joined Dr. Brody’s staff, and he sensed a fertile ground for a genetic study of this disease. He then gathered a body of information on torsion dystonias, which provided important insights on the various genetic forms of the disease, their clinical presentation, and geographic and ethnic patterns. On January 9, 1970, Dr. Roswell Eldridge convened a conference on the torsion dystonias at NIH in Bethesda, MD, USA.

When he moved from St. Thomas’s Hospital to King’s College in 1970, David Marsden was already interested in the pathophysiology of movement and had studied the physiology of human tremor. In 1973, he gave a lecture on drug treatment of diseases characterized by abnormal movements at a symposium on “Involuntary movements other than parkinsonism” (43). On that occasion, he reported that “chorea (including hemiballism and orofacial dyskinesia) and generalized torsion dystonia may be considered together, for the abnormal movements of both can be reduced by the same groups of drugs, although neither can be cured,” and that “spasmodic torticollis must also be mentioned briefly, for it is a common problem.” He later became fascinated by dystonia, an involuntary movement with irregular features compared to tremor and with unknown pathophysiology.

In his publication dedicated to the review of 42 patients with dystonia, Marsden recognized that “idiopathic torsion dystonia (dystonia musculorum deformans) is a rare and fascinating disease” (44). This paper contains all the elements for considering dystonia a unique disease. He used Herz’s diagnostic criteria (21) and distinguished three types of onset: the commonest being a difficulty to use one or both arms, the second commonest was an abnormality of gait, whereas in a minority of patients, the initial abnormality was confined to the neck and trunk. In half of the patients, the disease progressed to involve all the limbs and trunk, and in the remaining half, the disease was confined to one portion of the body and never became generalized. Marsden still considered cervical dystonia a separate entity and stated: “the characteristic features of torsion dystonia in adults is that it is usually restricted to one part of the body and that it is usually non-progressive. In these respects adult-onset torsion dystonia strikingly resembles isolated spasmodic torticollis, which we deliberately excluded from the study” (44).

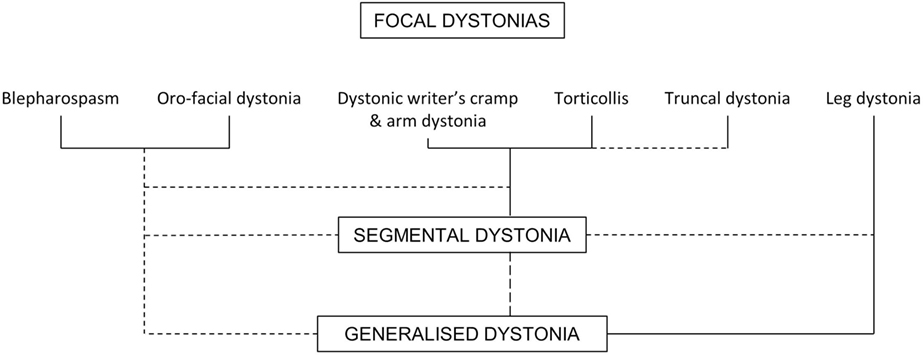

In 1975, Marsden attended the first international conference on dystonia that was convened in New York by Roswell Eldridge and Stanley Fahn. Compared to the conference held in Bethesda 5 years before, this was called international as the faculty originated also from outside the United States. Stanley Fahn, who was at Columbia University in New York, had seen the daughter of Samuel and Frances Belzberg who was affected by generalized dystonia and consulted with Dr. Eldridge, who had extensively reviewed the genetic epidemiology of dystonia at the 1970 conference (45). The Belzberg family supported the creation of the Dystonia Foundation (today Dystonia Medical Research Foundation) and the 1975 international symposium. Stanley Fahn was particularly interested in the phenomenology and classification of dystonia and defended the view that dystonia was a symptom of several different dystonic syndromes, which he attempted to classify (46). At the same meeting, Marsden reported on “the problem of adult-onset idiopathic torsion dystonia and other isolated dyskinesias in adult life (including blepharospasm, oromandibular dystonia, dystonic writer’s cramp, and torticollis, or axial dystonia)” (47). The slide he showed lumping together blepharospasm, orofacial dystonia, writer’s cramp, torticollis, truncal dystonia, and leg dystonia was quite visionary (Figure 1). He probably drafted it at one of the afterhours meetings with his assistants and fellows at The Phoenix and Firkin pub in Denmark Hill (48).

Figure 1. “Possible interrelations between blepharospasm, oromandibular dystonia, dystonic writer’s cramp, and torticollis/axial dystonia (focal dystonias), and idiopathic torsion dystonia of segmental or generalized type. Common associations are shown by solid lines, and rare transitions by dashed lines” modified from (47). Marsden’s handwritten schemes can be found also in other publications, such as the Roberg Wartenberg lecture (49) or the Phoenix and Firkin beermats (48).

The founding of the modern concept of dystonia is considered to have occurred exactly 40 years ago, in 1976, when David Marsden published several reports on dystonia (50–53). One of these accounts, in particular, suggested that blepharospasm could be a variant of adult-onset focal dystonia (53). This was a striking notation, not only due to the vivid picturing of De Gaper, by Pieter Brueghel the Elderly; but also because blepharospasm had not previously entered the spectrum of dystonia, and was not considered a phenomenology of formes frustes or a body part involved in generalized dystonia. Marsden concluded that “(1) blepharospasm and oromandibular dystonia are manifestations of a single illness or syndrome; (2) this is a physical illness, not a manifestation of a psychiatric disorder; (3) this syndrome is related to idiopathic torsion dystonia.”

In the following years at Denmark Hill, the interest in myoclonus melted with that of dystonia and spanned from phenomenology to physiology and experimental animal models. Chorea and dystonia were recognized in patients with Parkinson’s disease (54, 55). Primary writing tremor was described as a condition independent of “myoclonic jerks occurring in dystonia” and of “benign essential tremor” (56).

In 1981, an ad hoc committee established by the Research Group on Extrapyramidal Disorders of the World Federation of Neurology, chaired by André Barbeau (including David Marsden, but not Stanley Fahn) proposed that “hyperkinesias” encompassed tremors, tics, myoclonus, chorea, ballism, athetosis, and akathisia (57). Dystonia was listed under “disorders of posture and tone” aside “torsion spasm,” cogwheel phenomenon, hypertonia (encompassing rigidity and Gegehalten), and hypotonia. This classification did not have follow-up. By the same time, in a parallel publication Marsden listed chorea, dystonia, tremor, myoclonus, and tics under the collective heading of dyskinesias, as distinguished from rigid-akinetic syndromes (58). In a celebrated Robert Wartenberg lecture, delivered in April 1981 in front of the American Academy of Neurology, David Marsden summarized his vision of basal ganglia functions by putting together pathophysiology, anatomy, nosology, and phenomenology (49). Around that time, he conceived and crafted along with Stanley Fahn the intellectual and practical infrastructure for the current thinking on dystonia and other movement disorders. Together, they discerned and promulgated the critical clinical characteristics that distinguish dystonia from other involuntary movements (59).

The focal dystonias were then lumped together, as a coherent clinical set encompassing cranial dystonia (including blepharospasm), oromandibular dystonia, spasmodic torticollis, truncal dystonia, writer’s cramp, and other occupational dystonias (60). Specific publications were dedicated to characterize this newly defined large set of organic diseases called dystonias: “spastic dysphonia” (61), writer’s cramp (62), myoclonus dystonia (63), and tardive dystonia (64). At the same time, neurophysiological studies aimed to identify a common pathophysiology for the dystonia syndromes: a quite challenging task (65, 66).

Is dystonia one or many diseases? The lucid effort of lumping together conditions that were previously considered separate diseases has greatly contributed to the modern era of movement disorders but has left unsolved the issue of whether dystonia is to be regarded today as a single disease entity, a syndrome, a collection of physical signs, or as a somehow heterogeneous collection of syndromes. The cases for lumping different dystonias into a unique disease entity, or by the contrary to split them into separate conditions, have been the object of a recent review (67). There is no unique etiology or pathophysiology for different dystonia syndromes and—although a number of features clearly overlap—we have to admit that clinical features, etiology, and pathophysiology are heterogeneous. Dystonia still remains a mysterious condition notwithstanding a dramatic increase in knowledge.

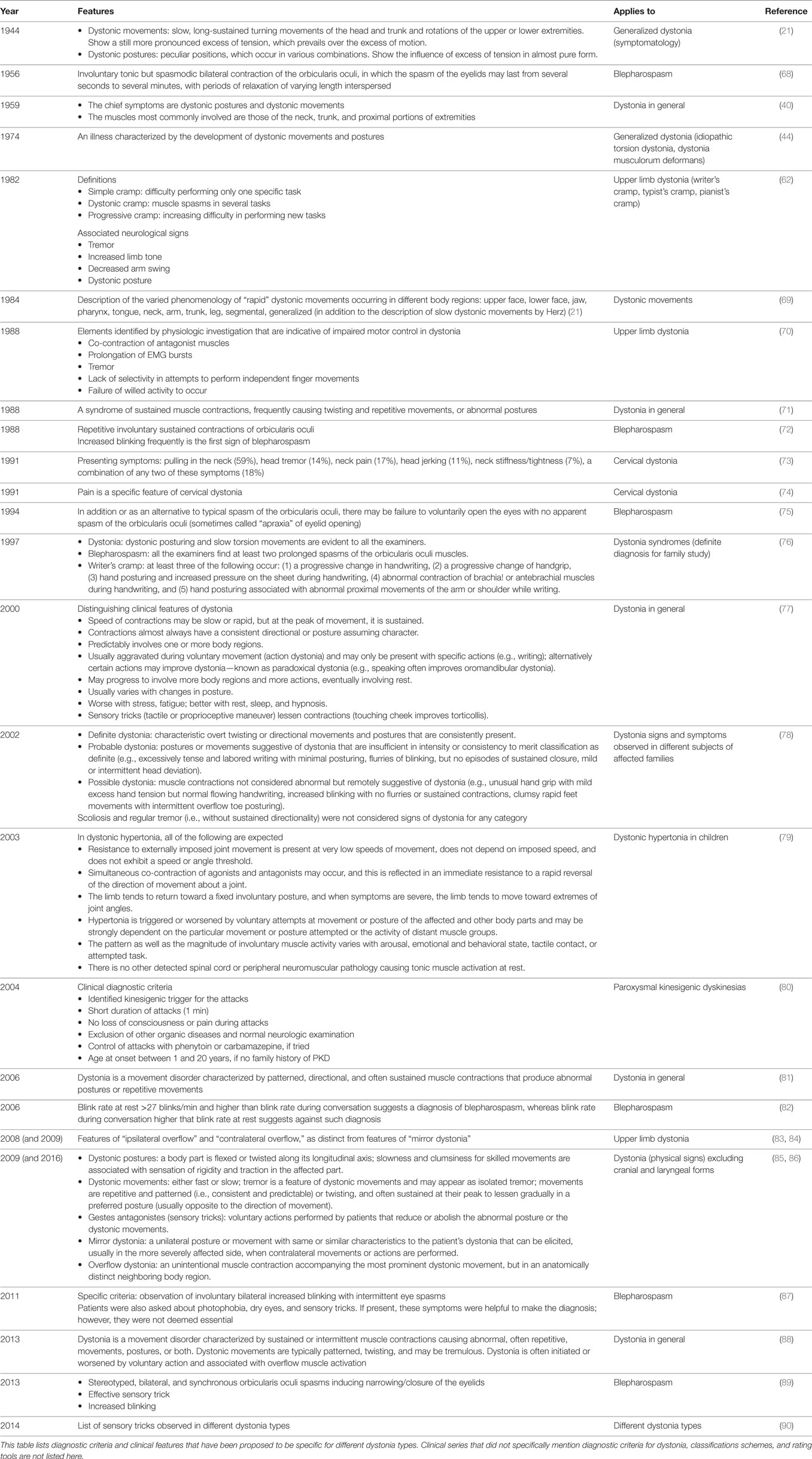

Table 2 summarizes the evolution of observed clinical features of dystonia syndromes. Some observations have been retained over time, the most solid one being the recognition of dystonic movements and postures as the hallmarks features of dystonia, as noted by Herz’s cinematic studies (21). Some observations deal with dystonia in general, while others list features and diagnostic criteria for specific focal dystonia types. These two viewpoints do not necessarily overlap.

Table 2. Features observed in dystonia and diagnostic criteria for different dystonia types have evolved over time.

Ten papers considered the general features of dystonia, defined as a disease, a syndrome, or a collection of physical signs (Table 2). Herz (21) was the first to define diagnostic criteria for dystonia that have been updated in recent years by recognizing five main physical signs of dystonia (85, 86) that can be reliably recognized when the limbs or the neck/trunk are affected. By contrast, these features are difficult to assess in patients with blepharospasm, which has a different phenomenology, or spasmodic dysphonia, where the abnormal movements are hard to see. The five physical signs of dystonia encompass dystonic postures, dystonic movements, tricks/gestes, mirror dystonia, and overflow. When several of these signs occur together in the same patient, a diagnosis of dystonia can be reliably made. As for other medical diagnoses, not all the physical signs have to occur simultaneously, but they need to be in sufficient number to provide a strong diagnostic clue. Some of the general diagnostic criteria for dystonia have been developed for the study of affected families using linkage studies, where the affected or non-affected status provided a discriminant variable (76, 78). In these families, focal phenotypes were considered alternative phenotypes or formes frustes of a same genetic condition.

Six publications defined the features and diagnostic criteria of blepharospasm. This focal form has different features from dystonia affecting the limbs or trunk. Diagnostic criteria for blepharospasm have been proposed only recently, and their specificity is a matter of discussion (89). Four publications reported diagnostic features of upper limb dystonia, and two (unlisted) studied assessed lower limb dystonia without indicating diagnostic criteria (91, 92). It is interesting to note that very few publications have tried to list diagnostic features of cervical dystonia, which is still diagnosed based on clinical experience and often considered an easy diagnostic task.

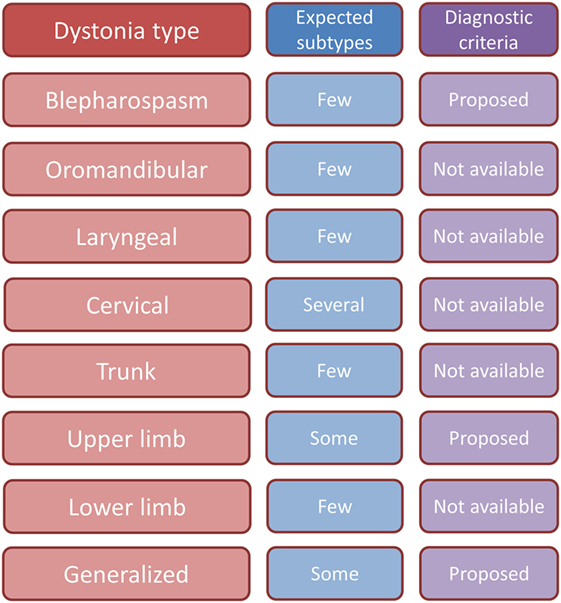

The swing is currently moving back toward recognizing the specific identity of focal dystonia syndromes. A Delphi method approach is being used by the Movement Disorders Society Dystonia Task Force to identify specific criteria for blepharospasm and for cervical dystonia. In the time to come, general diagnostic criteria for dystonia as a whole and specific criteria for focal dystonia syndromes will probably coexist. Clinical trials on focal dystonias require the harmonic implementation of well-defined criteria in multicentric settings. A currently unmet need is the characterization of clinical subtypes of dystonias and the identification of diagnostic criteria for each of them (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Synopsis table of expected clinical subtypes and status of proposed diagnostic criteria for different dystonias.

Based on current knowledge, it remains hard to accept dystonia as a single disease: nosologically, it is a collection of syndromes (93); phenomenologically, it is a collection of physical signs (85). However, there is no combination of physical signs that accommodates for all focal and generalized dystonia types: cranial and laryngeal dystonia have evidently a different phenomenology from limb and trunk dystonia. The physical signs of dystonia may apply to cervical and limb dystonia syndromes and may be used for the purpose of clinical diagnosis. By contrast, specific sets of clinical features and related diagnostic criteria still need to be developed for cranial and laryngeal dystonias.

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and approved it for publication.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

This work is supported by European Cooperation in Science and Technology (COST) Action BM1101 “European network for the study of dystonia syndromes.”

1. Denny-Brown D. Diseases of the basal ganglia. Their relation to disorders of movement. Part II. Lancet (1960) 2(7161):1155–62. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(60)92353-9

4. Heister L. Chirurgie, In welcher alles, was zur Wund-Artzney gehört, Nach der neuesten und besten Art, gründlich abgehandelt, und In vielen Kupffer-Tafeln die neu-erfundene und dienlichste Instrumenten, Nebst den bequemsten Handgriffen der Chirurgischen Operationen und Bandagen vorgestellet werden. Nürnberg: Johann Hoffmanns seel Erben (1731).

5. Reichel G. Cervical dystonia: a new phenomenological classification for botulinum toxin therapy. Basal Ganglia (2011) 1:5–12. doi:10.1016/j.baga.2011.01.001

6. Delore X. Du torticolis postérieur et de son traitement par le redressement forcé et le bandage silicaté. Paris: Masson (1878).

7. Fabre AFH. Dictionnaire des dictionnaires de médecine français et étrangers. Traité complet de médecine et de chirurgie pratiques. Paris: Germer-Baillière (1841).

8. Jaccoud S. Nouveau dictionnaire de medecine et de chirurgie pratiques. Paris: J.-B. Baillière (1864).

9. Pitres A. Leçons cliniques sur l’hystérie et l’hypnotisme faites à l’hôpital Saint-André de Bordeaux. Paris: Octave Doin (1891).

12. Gowers WR. A Manual of Diseases of the Nervous System. 2 ed. (Vol. 2). London: J. & A. Churchill (1888).

13. Gowers WR. On tetanoid chorea and its association with cirrhosis of the liver. Rev Neurol Psychiatry (1919) 4:249–58.

14. Oppenheim H. Über eine eigenartige Krampfkrankheit des kindlichen und jugendlichen alters (Dysbasia lordotica progressiva, Dystonia musculorum deformans). Neurol Centralbl (1911) 30:1090–107.

15. Ziehen T. Ein fall von tonischer Torsionsneurose. Demonstrationen im Psychiatrischen Verein zu Berlin. Neurol Centralbl (1911) 30:109–10.

16. Flatau E, Sterling W. Progressiver Torsionspasm bie Kindern. Z ges Neurol Psychiat (1911) 7:586–612. doi:10.1007/BF02865155

17. Mendel K. Torsiondystonie (dystonia musculorum deformans, Torsionsspasmus). Mschr Psychiat Neurol (1919) 46:309–61. doi:10.1159/000190724

18. Wilson SAK. The tics and allied conditions: opening papers. J Neurol Psychopathol (1927) 30:104–8. doi:10.1136/jnnp.s1-8.30.93

19. Broussolle E, Laurencin C, Bernard E, Thobois S, Danaila T, Krack P. Early Illustrations of geste antagoniste in cervical and generalized dystonia. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov (N Y) (2015) 5:332. doi:10.7916/D8KD1X74

20. Cruchet R. La forme bradykinésique (ou pseudo-parkinsonienne) de l’encéphalomyélite épidémique. Rev Neurol (Paris) (1921) 37:665–72.

21. Herz E. Dystonia. I. Historical review: analysis of dystonic symptoms and physiologic mechanisms involved. Arch Neurol Psychiat (Chicago) (1944) 51:305–18. doi:10.1001/archneurpsyc.1944.02290280003001

22. Thompson HT, Sinclair J. Telegraphists’ cramp. An extract from the report of the departmental committee, general post office, on the subject with additional matter. Lancet (1912) 179:888–1010. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(01)67315-X

24. Duchenne GB. De l’électrisation localisée et de son application à la pathologie et à la thérapeutique. Paris: Baillière et Fils (1872).

25. Gowers WR. Occupational Neuroses. A Manual of Diseases of the Nervous System. 2nd ed. London: Churchill (1892). p. 710–30.

26. Solly S. Clinical lectures on scriveners’ palsy, or the paralysis of writers. Lancet (1864) 84-85(2156, 2161, 2162):709–115.

27. Poore GV. An analysis of ninety-three cases of writer’s cramp and impaired writing power; making, with seventy-five cases previously reported, a total of one hundred and sixty-eight cases. Med Chir Trans (1887) 70:301–33. doi:10.1177/095952878707000121

28. Cronbach E. Die Beschäftigungsneurose der Telegraphisten. Arch Psychiatr Nervenkr (1903) 37:243–93. doi:10.1007/BF02227703

29. Gilbert GJ. Brueghel syndrome: its distinction from Meige syndrome. Neurology (1996) 46:1767–9. doi:10.1212/WNL.46.6.1767

30. de Spéville D. Deux cas de blépharospasme, guéris par des procédés differents. Rec d’Opht (1906) 28:232–5.

31. Meige H. Les convulsions de la face. Une forme clinique de convulsion faciale bilatérale et médiane. Rev Neurol (Paris) (1910) 20:437–43.

32. Altrocchi PH. Spontaneous oral-facial dyskinesia. Arch Neurol (1972) 26:506–12. doi:10.1001/archneur.1972.00490120046004

33. Paulson GW. Meige’s syndrome. Dyskinesia of the eyelids and facial muscles. Geriatrics (1972) 27:69–73.

34. Tolosa ES. Clinical features of Meige’s disease (idiopathic orofacial dystonia): a report of 17 cases. Arch Neurol (1981) 38:147–51. doi:10.1001/archneur.1981.00510030041005

35. Traube L. Spastiche Form der nervosen Helserkeit. Gesammelte Beltrage zur Pathologie und Physiologie. Berlin: Hirschwald (1871).

36. Meige H. Dysphasie syngultuese avec réactions motrices tetaniformes et gestes stéréotypes. Rev Neurol (Paris) (1914) 27:310–5.

37. Critchley M. Spastic dysphonia (“inspiratory speech”). Brain (1939) 62:96–103. doi:10.1093/brain/62.1.96

38. Cooper IS. Anterior choroidal artery ligation for involuntary movements. Science (1953) 118:193. doi:10.1126/science.118.3059.193

39. Cooper IS. Intracerebral injection of procaine into the globus pallidus in hyperkinetic disorders. Science (1954) 119:417–8. doi:10.1126/science.119.3091.417

40. Zeman W, Kaelbling R, Pasamanick B. Idiopathic dystonia musculorum deformans. I. The hereditary pattern. Am J Hum Genet (1959) 11:188–202.

41. Barrett RE, Yahr MD, Duvoisin RC. Torsion dystonia and spasmodic torticollis – results of treatment with l-DOPA. Neurology (1970) 20:107–13. doi:10.1212/WNL.20.11_Part_2.107

43. Marsden CD. Drug treatment of diseases characterized by abnormal movements. Proc R Soc Med (1973) 66(9):871–3.

44. Marsden CD, Harrison MJ. Idiopathic torsion dystonia (dystonia musculorum deformans). A review of forty-two patients. Brain (1974) 97:793–810. doi:10.1093/brain/97.1.793

45. Eldridge R. The torsion dystonias: literature review and genetic and clinical studies. Neurology (1970) 20(Pt 2):1–78. doi:10.1212/WNL.20.11_Part_2.1

46. Fahn S, Eldridge R. Definition of dystonia and classification of the dystonic states. Adv Neurol (1976) 14:1–5.

47. Marsden CD. The problem of adult-onset idiopathic torsion dystonia and other isolated dyskinesias in adult life (including blepharospasm, oromandibular dystonia, dystonic writer’s cramp, and torticollis, or axial dystonia). Adv Neurol (1976) 14:259–76.

48. Quinn N, Rothwell J, Jenner P. Charles David Marsden (15 April 1938–29 September 1998). Biogr Mems Fell R Soc (2012) 58:203–28. doi:10.1098/rsbm.2012.0026

49. Marsden CD. The mysterious motor function of the basal ganglia: the Robert Wartenberg Lecture. Neurology (1982) 32:514–39. doi:10.1212/WNL.32.5.514

50. Marsden CD, Merton PA, Morton HB. Servo action in the human thumb. J Physiol (1976) 257:1–44. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1976.sp011354

51. Marsden CD, Harrison MJ, Bundey S. Natural history of idiopathic torsion dystonia. Adv Neurol (1976) 14:177–87.

52. Marsden CD. Dystonia: the spectrum of the disease. Res Publ Assoc Res Nerv Ment Dis (1976) 55:351–67.

53. Marsden CD. Blepharospasm-oromandibular dystonia syndrome (Brueghel’s syndrome). A variant of adult-onset torsion dystonia? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry (1976) 39:1204–9. doi:10.1136/jnnp.39.12.1204

54. Duvoisin RC, Marsden CD. Note on the scoliosis of parkinsonism. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry (1975) 38:787–93. doi:10.1136/jnnp.38.8.787

55. Parkes JD, Bedard P, Marsden CD. Chorea and torsion in parkinsonism. Lancet (1976) 308(7977):155. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(76)92894-4

56. Rothwell JC, Traub MM, Marsden CD. Primary writing tremor. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry (1979) 42:1106–14. doi:10.1136/jnnp.42.12.1106

57. Barbeau A, Duvoisin RC, Gersterbrand F, Lakke JP, Marsden CD, Stern G. Classification of extrapyramidal disorders. J Neurol Sci (1981) 51:311–27. doi:10.1016/0022-510X(81)90109-X

58. Marsden CD, Schachter M. Assessment of extrapyramidal disorders. Br J Clin Pharmacol (1981) 11(2):129–51. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1981.tb01118.x

59. Marsden CD, Fahn S, editors. Movement Disorders. London: Butterworth Scientific (1982). p. 1–359.

61. Marsden CD, Sheehy MP. Spastic dysphonia, Meige disease, and torsion dystonia. Neurology (1982) 32:1202–3. doi:10.1212/WNL.32.10.1202

62. Sheehy MP, Marsden CD. Writers’ cramp: a focal dystonia. Brain (1982) 105:461–80. doi:10.1093/brain/105.3.461

63. Obeso JA, Rothwell JC, Lang AE, Marsden CD. Myoclonic dystonia. Neurology (1983) 33:825–30. doi:10.1212/WNL.33.7.825

64. Burke RE, Fahn S, Jankovic J, Marsden CD, Lang AE, Gollomp S, et al. Tardive dystonia: late-onset and persistent dystonia caused by antipsychotic drugs. Neurology (1982) 32:1335–46. doi:10.1212/WNL.32.12.1335

65. Rothwell JC, Obeso JA, Day BL, Marsden CD. Pathophysiology of dystonias. Adv Neurol (1983) 39:851–63.

67. Jinnah HA, Berardelli A, Comella C, Defazio G, DeLong MR, Factor S, et al. The focal dystonias: current views and challenges for future research. Mov Disord (2013) 28:926–43. doi:10.1002/mds.25567

70. Cohen LG, Hallett M. Hand cramps: clinical features and electromyographic patterns in a focal dystonia. Neurology (1988) 38:1005–12. doi:10.1212/WNL.38.7.1005

71. Fahn S. Concept and classification of dystonia. Adv Neurol (1988) 50:1–8. doi:10.1212/WNL.50.5_Suppl_5.S1

72. Grandas F, Elston J, Quinn N, Marsden CD. Blepharospasm: a review of 264 patients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry (1988) 51:767–72. doi:10.1136/jnnp.51.6.767

73. Jankovic J, Leder S, Warner D, Schwartz K. Cervical dystonia: clinical findings and associated movement disorders. Neurology (1991) 41:1088–91. doi:10.1212/WNL.41.7.1088

74. Chan J, Brin MF, Fahn S. Idiopathic cervical dystonia: clinical characteristics. Mov Disord (1991) 6:119–26. doi:10.1002/mds.870060206

75. Aramideh M, Ongerboer de Visser BW, Koelman JH, Bour LJ, Devriese PP, Speelman JD. Clinical and electromyographic features of levator palpebrae superioris muscle dysfunction in involuntary eyelid closure. Mov Disord (1994) 9:395–402. doi:10.1002/mds.870090404

76. Bentivoglio AR, Del Grosso N, Albanese A, Cassetta E, Tonali P, Frontali M. Non-DYT1 dystonia in a large Italian family. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry (1997) 62:357–60. doi:10.1136/jnnp.62.4.357

77. Bressman SB. Dystonia update. Clin Neuropharmacol (2000) 23:239–51. doi:10.1097/00002826-200009000-00002

78. Bressman SB, Raymond D, Wendt K, Saunders-Pullman R, de Leon D, Fahn S, et al. Diagnostic criteria for dystonia in DYT1 families. Neurology (2002) 59:1780–2. doi:10.1212/01.WNL.0000035630.12515.E0

79. Sanger TD, Delgado MR, Gaebler-Spira D, Hallett M, Mink JW; Task Force on Childhood Motor Disorders. Classification and definition of disorders causing hypertonia in childhood. Pediatrics (2003) 111:e89–97. doi:10.1542/peds.111.1.e89

80. Bruno MK, Hallett M, Gwinn-Hardy K, Sorensen B, Considine E, Tucker S, et al. Clinical evaluation of idiopathic paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesia: new diagnostic criteria. Neurology (2004) 63:2280–7. doi:10.1212/01.WNL.0000147298.05983.50

81. Geyer HL, Bressman SB. The diagnosis of dystonia. Lancet Neurol (2006) 5:780–90. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70547-6

82. Bentivoglio AR, Daniele A, Albanese A, Tonali PA, Fasano A. Analysis of blink rate in patients with blepharospasm. Mov Disord (2006) 21:1225–9. doi:10.1002/mds.20889

83. Sitburana O, Jankovic J. Focal hand dystonia, mirror dystonia and motor overflow. J Neurol Sci (2008) 266:31–3. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2007.08.024

84. Sitburana O, Wu LJ, Sheffield JK, Davidson A, Jankovic J. Motor overflow and mirror dystonia. Parkinsonism Relat Disord (2009) 15:758–61. doi:10.1016/j.parkreldis.2009.05.003

86. Albanese A, Del Sorbo F. Dystonia and tremor: the clinical syndromes with isolated tremor. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov (N Y) (2016) 6:319.

87. Peckham EL, Lopez G, Shamim EA, Richardson SP, Sanku S, Malkani R, et al. Clinical features of patients with blepharospasm: a report of 240 patients. Eur J Neurol (2011) 18:382–6. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.03161.x

88. Albanese A, Bhatia K, Bressman SB, DeLong MR, Fahn S, Fung VS, et al. Phenomenology and classification of dystonia: a consensus update. Mov Disord (2013) 28:863–73. doi:10.1002/mds.25475

89. Defazio G, Hallett M, Jinnah HA, Berardelli A. Development and validation of a clinical guideline for diagnosing blepharospasm. Neurology (2013) 81:236–40. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e31829bfdf6

90. Ramos VF, Karp BI, Hallett M. Tricks in dystonia: ordering the complexity. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry (2014) 85:987–93. doi:10.1136/jnnp-2013-306971

91. Schneider SA, Edwards MJ, Grill SE, Goldstein S, Kanchana S, Quinn NP, et al. Adult-onset primary lower limb dystonia. Mov Disord (2006) 21:767–71. doi:10.1002/mds.20794

92. McKeon A, Matsumoto JY, Bower JH, Ahlskog JE. The spectrum of disorders presenting as adult-onset focal lower extremity dystonia. Parkinsonism Relat Disord (2008) 14:613–9. doi:10.1016/j.parkreldis.2008.01.012

Keywords: dystonia, movement disorders, history, definition and concepts, phenomenology

Citation: Albanese A (2017) How Many Dystonias? Clinical Evidence. Front. Neurol. 8:18. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2017.00018

Received: 03 November 2016; Accepted: 12 January 2017;

Published: 03 February 2017

Edited by:

Antonio Pisani, University of Rome Tor Vergata, ItalyReviewed by:

Graziella Madeo, National Institutes of Health (NIH), USACopyright: © 2017 Albanese. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Alberto Albanese, YWxiZXJ0by5hbGJhbmVzZUB1bmljYXR0Lml0

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.