- 1 Neurology Service, New Mexico Veterans Affairs Health Care System, Albuquerque, NM, USA

- 2 Department of Neurology, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque, NM, USA

- 3 Office of Program Evaluation, Education, and Research, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque, NM, USA

Objective: Evaluate medical students’ communication and professionalism skills from the perspective of the ambulatory patient and later compare these skills in their first year of residency. Methods: Students in third year neurology clerkship clinics see patients alone followed by a revisit with an attending neurologist. The patient is then asked to complete a voluntary, anonymous, Likert scale questionnaire rating the student on friendliness, listening to the patient, respecting the patient, using understandable language, and grooming. For students who had completed 1 year of residency these professionalism ratings were compared with those from their residency director. Results: Seven hundred forty-two questionnaires for 165 clerkship students from 2007 to 2009 were analyzed. Eighty-three percent of forms were returned with an average of 5 per student. In 64% of questionnaires, patients rated students very good in all five categories; in 35% patients selected either very good or good ratings; and <1% rated any student fair. No students were rated poor or very poor. Sixty-two percent of patients wrote complimentary comments about the students. From the Class of 2008, 52% of students received “better than their peers” professionalism ratings from their PGY1 residency directors and only one student was rated “below their peers.” Conclusion: This questionnaire allowed patient perceptions of their students’ communication/professionalism skills to be evaluated in a systematic manner. Residency director ratings of professionalism of the same students at the end of their first year of residency confirms continued professional behavior.

Introduction

Medical professionalism and communication skills are increasingly recognized as important components of being a physician. Many medical specialties and associations have agreed on the fundamentals of professionalism (Medical Professionalism Project, 2002). Among the many qualities expected of a physician, maintaining appropriate relationships with patients, being honest with patients, and maintaining patient trust are essential for a medical student to master. Being a good doctor requires not only knowledge and technical skills but also communication and professional behavior skills (Stern et al., 2005).

All medical schools including the University of New Mexico School of Medicine teach professionalism and communication skills with patients and their families. The challenge is to determine whether students are learning these skills and apply them during their clerkship rotations. While assessments of student professionalism during the clinical years are common at many medical schools, this is accomplished predominantly by attending and resident overall evaluations. A 2005 professionalism review showed patient evaluations of students, residents, and physicians were included in only 6% of the studies and only 3% of medical student evaluations included observations by their patients (Veloski et al., 2005). Published 360° professionalism evaluations of students frequently utilize forms completed by faculty, residents, other students, nurses, and social workers but often do not include the patient (Musick et al., 2003; Lelliott et al., 2008; Massagli and Carline, 2008).

The lack of patient input is surprising since communication and professionalism is the heart of the doctor-patient relationship. Studies show that patient satisfaction and trust in their doctor affects consistency of their self-care, medication compliance, health outcomes, level of service utilization, choice of future health professionals, and decisions to sue in the face of adverse outcomes (Pichert et al., 1998; Thom et al., 2002; Bonds et al., 2004). In one review of 12,000 patient and family complaints, 20% of patient dissatisfaction resulted from problems in communication and 10% arose from perceived disrespect, two aspects of medical professionalism (Pichert et al., 1998). Another study reported patients with low trust in their doctor were less likely to follow the physician’s recommendations or report symptom improvement at 2 weeks, more likely to report a needed or requested service was not provided, and more likely to report less overall satisfaction with the visit (Thom et al., 2002).

To include the patient’s perspective, we developed a professionalism questionnaire that was given to patients in the general neurology clinic first seen by a medical student. The results of these patients’ evaluations are presented in this article.

Materials and Methods

This prospective study ran from March 2007 to July 2009 in the general neurology clinics at the New Mexico Veterans Affairs (VA) Health Care System. Students at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine spend part of their clerkship year training in VA general neurology clinics and were eligible to participate in the study as approved by the VA research committee and the University of New Mexico Human Research Review Committee.

Our neurology clinics were designed to allow a medical student to initially see a patient alone and conduct a history and physical examination with the expectation of good patient communication and professional behavior during this interaction. After the student left the patient room, they presented their history, exam, differential diagnosis, and management plan to an attending physician. Both student and attending returned to the patient where the attending physician revisited the history, conducted an independent neurologic exam, established the final diagnosis, and developed, often with the student, a plan for workup, and management. At the end of this encounter the student asked their patient to voluntarily evaluate them by completing the questionnaire.

The communication/professionalism form was designed with several goals. First, the form had to be anonymous with respect to the patient but contain the student’s name. This reassured the patient that their student evaluation could not have any negative consequences to their medical care. In this study, instead of the student name, each student was assigned a random number and entered into the database. However, each student received feedback in writing on their full set of patient evaluations at the end of the rotation. Second, the form had to ask important questions about communication and professionalism in a doctor-patient relationship easily understandable from the patient’s perspective. To accomplish this we reviewed the literature on professionalism, interviewed professionals in the fields of general and medical education, and field-tested sample questions to students and patients. Final questions selected came from published, often validated, questionnaires administered to students, residents, and physicians at medical schools in the USA and UK but slightly modified for medical students in our clinic. Third, the form had to be friendly, short, and simple for patients of all ages and backgrounds to understand and complete.

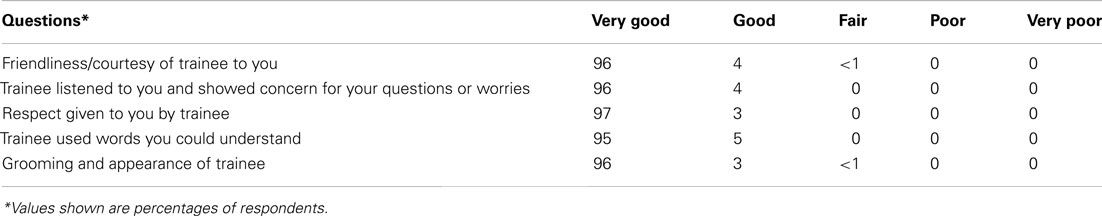

Our communication/professionalism form contained five items (Table 1). Each item was rated on a Likert scale (similar to the other published questionnaires) from 1 (Very Poor) to 5 (Very Good). A comment section was available at the bottom of the form. The name of the medical student was on the form but no patient identifiers were included.

We included a question on student grooming since an effective, trusting patient-doctor relationship involves both verbal and non-verbal communication including the doctor’s clothing, grooming, and cleanliness (Brandt, 2003; Rehman et al., 2005). Even Hippocrates advised that physicians should “be clean in person, well-dressed, and anointed with sweet smelling ungents” (Jones, 1923).

The authors collected the forms weekly and reviewed them for potential serious problems in professionalism. The patients’ evaluations along with those from faculty and residents formed part of the student’s overall professionalism grade.

To determine whether a patient’s evaluation of the student’s professionalism predicted future communication skills and professionalism during their first year of residency, we analyzed a subgroup of students who completed their first year of medical residency by summer of 2010. These students’ clerkship scores were compared with evaluation forms that their first year residency directors sent to the medical school. The residency director form included three questions similar to ones we asked the students and asked the director to compare our student skills with the other residents in: Communicating with patients and families; Listening to and communicating with patients in order to understand the individual; and Sensitivity to patients of all cultures, ages, genders, and disabilities.

Results

One hundred ninety-nine third year students from four medical school classes rotated through the neurology clerkship during the study period. Thirty-four students received no patient evaluations due to an intermittent lack of available professionalism forms and student withdrawal or illness for all or most of the clerkship. Of the 165 students evaluated, 53% were female and 33% were under-represented minorities (Hispanic, Native American, or African American).

Neurology patients who saw a student first completed a total of 752 evaluations on 165 students. Ten evaluations were discarded because they failed to contain the student’s name leaving a total of 742 usable evaluations. None of the discarded evaluations reported negative ratings for the unknown students. The number of patient evaluations on each student ranged from 1 to 14 with an average of 5 per student.

Sixty-four percent of the evaluations (479/742) rated the students very good in all five categories, 261 evaluations (35%) contained good as the lowest rating and 2 evaluations (<1%) contained a fair rating (Table 1). There were no differences in ratings by student gender or ethnicity.

Patients wrote comments on 62% of the forms and all were complimentary. Examples of common patient comments were “Answered my questions and educated me in preventive measures”; “Listened to me and was non-judgmental”; “Appreciated my wife’s presence – that means a lot”; “I wish every person was as caring as he was.” Reasons for a rating other than very good were never included in the evaluation comments.

In an attempt to estimate the percent of neurology patients who completed student evaluations, we identified 665 clinic patients seen by a student in 2008 or 2009. From this independent information, we determined that 553 patients (83%) who were first evaluated by a student completed a professionalism form. As patient evaluations were anonymous, we could not determine which student saw which patient.

At the end of the student’s neurology clerkship, written, and verbal statements from attending physicians and residents at the University and VA hospitals were compared to the student’s evaluation scores. Both ratings were high for all students. No faculty or resident noted poor professionalism regarding students’ interactions with patients, peers, residents, or faculty.

Sixty-six of the 165 students in this study completed 1 year of medical residency by summer of 2010 and we obtained residency director evaluations for 56 (85%). Of these students 52% received professionalism ratings “better than their peers,” 46% were equal to their peers, and only one student (2%) rated “below their peers.”

Discussion

Although tools and evaluation methods for communication/professionalism skills vary widely, an effective surveillance tool for detecting unprofessional behavior are the eyes and ears of patients and family members (Hickson et al., 2007). We systematically utilized the experience of patients in our formal evaluation of student communication/professionalism during the neurology clerkship for third year medical students.

Teaching professionalism and communication skills at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine begins in the first year and is considered important (Phelan et al., 1993). Before their clerkship year, students have listened to lectures, participated in small group discussions, and been critiqued by simulated patients on aspects of professionalism and their communication ability. In addition, students have participated in direct patient care through continuity clinics and a 2-month rotation with a general practitioner or internist so they enter the clerkship year with considerable patient experience.

Advantages of using the communication/professionalism form in the clinic are many. The form recorded the student’s behavior on over 80% of their patient encounters with an average of five patient ratings per student. Since unacceptable behavior is thought to occur spontaneously (Parker, 2006), it might not be identified by observations from a single patient encounter as in patient-student video or simulated patient encounters. Patients with a wide variety of behaviors ranging from stable, emotional, manic, angry, depressed, cognitively impaired, to schizophrenic scored the students’ professional behavior. Spouses or caregivers often completed the form with the patient allowing for an evaluation of how the student interacted with family members. This formal assessment communicates to students certain valued aspects of professionalism. The summary of the patients’ professionalism evaluation allowed the student to receive feedback on their professional behavior and potential areas for improvement. Finally, the student summaries were forwarded to the Dean’s office where they can be incorporated into the Dean’s letter prepared for the student’s residency application.

Limitations of the study include the possibility that when students concluded they behaved non-professionally with a patient, they may not have given the patient a professionalism form. Since the student gave the evaluation form to the patient at the end of the visit, it is possible that the patient could have included the behavior of the attending in the evaluation. However, the high percent of written commentaries by patients were always very specific to the student’s performance and never mentioned the attending suggesting they could separate the two behaviors. It has been observed that, compared to student peers, patients tend to rate medical providers fairly high on Likert scales which may have affected how students were rated (Epstein, 2007).

Evaluations from the attendings and residents who worked with the student regarding their professionalism are typically submitted to the clerkship director. Faculty and resident student professionalism evaluations tend to focus on student-doctor interactions, promptness in attending lectures and clinics, and timely completion of their notes, and seldom focus on direct observations of professional behaviors in interactions with patients, a problem that has been noted by others (Lurie et al., 2006). While we recognize that professionalism involves more than a patient’s assessment of a student’s behavior during an encounter, this perspective helps address the full range of student competencies.

Our ongoing patient communication/professionalism forms are used for both formative evaluations where the students are given feedback on any potential problems and serve as summative evaluations as part of their professionalism grade. If extreme professionalism problems are recognized by patients, they are forwarded to the clerkship director and Dean of Student’s office for possible intervention.

When comparing the patient evaluation regarding a student’s communication/professionalism skills in the clerkship, it was reassuring that the skills were not short-lived and persisted throughout the first year of their residency as measured by an independent evaluation from their residency director.

Since meaningful patient-doctor transactions can best be defined from the patient’s point of view (Duffy et al., 2004), assessments of the quality of medical encounters and communication skills of trainees from the patient’s perspective form a reliable basis for determining whether the earlier pre-clinical professionalism training is successful.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Bonds, D. E., Foley, K. L., Dugan, E., Hall, M. A., and Extrom, P. (2004). An exploration of patients’ trust in physicians in training. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 15, 294–306.

Brandt, L. J. (2003). On the value of an old dress code in the new millennium. Arch Intern. Med. 163, 1277–1281.

Duffy, F. D., Gordon, G. H., Whelan, G., Cole-Kelly, K., Frankel, R., Buffone, N., Lofton, S., Wallace, M., Goode, L., Langdon, L., and Participants in the American Academy of Physicians and Patient’s Conference on Education and Evaluation of Competence in Communication and Interpersonal Skills. (2004). Assessing competence in communication and interpersonal skills: the Kalamazoo II report. Acad. Med. 79, 495–507.

Hickson, G. B., Pichert, J. W., Webb, L. E., and Gabbe, S. G. (2007). A complementary approach to promoting professionalism: identifying, measuring, and addressing unprofessional behaviors. Acad. Med. 82, 1040–1048.

Jones, W. H. S. (1923). Hippocrates. Vol. 2. trans. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 311–312.

Lelliott, P., Williams, R., Mears, A., Andiappan, M., Owen, H., Reading, P., Coyle, N., and Hunter, S. (2008). Questionnaires for 360-degree assessment of consultant psychiatrists: development and psychometric properties. Br. J. Psychiatry 193,156–160.

Lurie, S. J., Norziger, A. C., Meldrum, S., Mooney, C., and Epstein, R. M. (2006). Temporal and group-related trends in peer assessment amongst medical students. Med. Educ. 40, 840–847.

Massagli, T. L., and Carline, J. D. (2008). Reliability of a 360-degree evaluation to assess resident competence. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 86, 845–852.

Medical Professionalism Project. (2002). Medical professionalism in the new millennium: a physicians’ charter. Lancet 359, 520–522.

Musick, D. W., McDowell, S. M., Clark, N., and Salcido, R. (2003). Pilot study of a 360-degree assessment instrument for physical medicine and rehabilitation residency programs. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 82, 394–402.

Phelan, S., Obenshain, S. S., and Galey, W. R. (1993). Evaluation of noncognitive professional traits of medical students. Acad. Med. 68, 799–803.

Pichert, J. W., Miller, C. S., Hollo, A. H., Gauld-Jaeger, J., Federspiel, C. F., and Hickson, G. B. (1998). What health professionals can do to identify and resolve patient dissatisfaction. Jt. Comm. J. Qual. Improv. 24, 303–312.

Rehman, S. U., Nietert, P. J., Cope, D. W., and Kilpatrick, A. O. (2005). What to wear today? Effect of doctor’s attire on the trust and confidence of patients. Am. J. Med. 118, 1279–1286.

Stern, D. T., Frohna, A. Z., and Gruppen, L. D. (2005). The prediction of professional behavior. Med. Educ. 39, 75–82.

Thom, D. H., Kravitz, R. L., Bell, R. A., Krupat, E., and Azari, R. (2002). Patient trust in the physician: relationship to patient requests. Fam. Pract. 19, 476–483.

Keywords: professional conduct, medical ethics, medical education

Citation: Davis LE, King MK, Wayne SJ and Kalishman SG (2012) Evaluating medical student communication/professionalism skills from a patient’s perspective. Front. Neur. 3:98. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2012.00098

Received: 12 May 2012; Accepted: 30 May 2012;

Published online: 20 June 2012.

Edited by:

Patty McNally, Loyola University Chicago, USAReviewed by:

Stephen Scelsa, Beth Israel Medical Center, USAKevin N. Sheth, University of Maryland School of Medicine, USA

Copyright: © 2012 Davis, King, Wayne and Kalishman. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial License, which permits non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in other forums, provided the original authors and source are credited.

*Correspondence: Larry E. Davis, Neurology Service, New Mexico Veterans Affairs Health Care System, 1501 San Pedro Dr. SE, Albuquerque, NM 87108, USA. e-mail: ledavis@unm.edu

Molly K. King1,2

Molly K. King1,2