95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

MINI REVIEW article

Front. Cell. Neurosci. , 16 September 2015

Sec. Cellular Neuropathology

Volume 9 - 2015 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fncel.2015.00354

This article is part of the Research Topic The role of the Plasminogen activating system in Neurobiology View all 13 articles

Blood proteins at the neurovascular unit (NVU) are emerging as important molecular determinants of communication between the brain and the immune system. Over the past two decades, roles for the plasminogen activation (PA)/plasmin system in fibrinolysis have been extended from peripheral dissolution of blood clots to the regulation of central nervous system (CNS) functions in physiology and disease. In this review, we discuss how fibrin and its proteolytic degradation affect neuroinflammatory, degenerative and repair processes. In particular, we focus on novel functions of fibrin—the final product of the coagulation cascade and the main substrate of plasmin—in the activation of immune responses and trafficking of immune cells into the brain. We also comment on the suitability of the coagulation and fibrinolytic systems as potential biomarkers and drug targets in diseases, such as multiple sclerosis (MS), Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and stroke. Studying coagulation and fibrinolysis as major molecular pathways that regulate cellular functions at the NVU has the potential to lead to the development of novel strategies for the detection and treatment of neurologic diseases.

The plasminogen activation (PA) system is an enzymatic cascade with key regulatory functions in fibrinolysis and degradation of extracellular matrix proteins (Syrovets and Simmet, 2004; Castellino and Ploplis, 2005; Kwaan, 2014). Plasminogen circulates in the blood as an inactive zymogen that is converted into active plasmin by tissue-type plasminogen activator (tPA) or urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA). The serine protease tPA is an immediate-early response gene expressed in the brain (Bignami et al., 1982; Qian et al., 1993; Sappino et al., 1993; Carroll et al., 1994; Tsirka et al., 1995). The activity of tPA is controlled by plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 (PAI-1). Upon activation, plasmin binds its main substrate fibrin(ogen) and degrades insoluble fibrin deposits that form intravascularly during blood clotting, as well as in the central nervous system (CNS) parenchyma after vascular rupture (Cesarman-Maus and Hajjar, 2005; Davalos et al., 2012). Fibrin controls plasmin activity through its capacity to bind plasminogen (Plg) as well as tPA or tPA/PAI-1 complexes to facilitate their proximate interaction (Wagner et al., 1989; Kaczmarek et al., 1993; Kim et al., 2012).

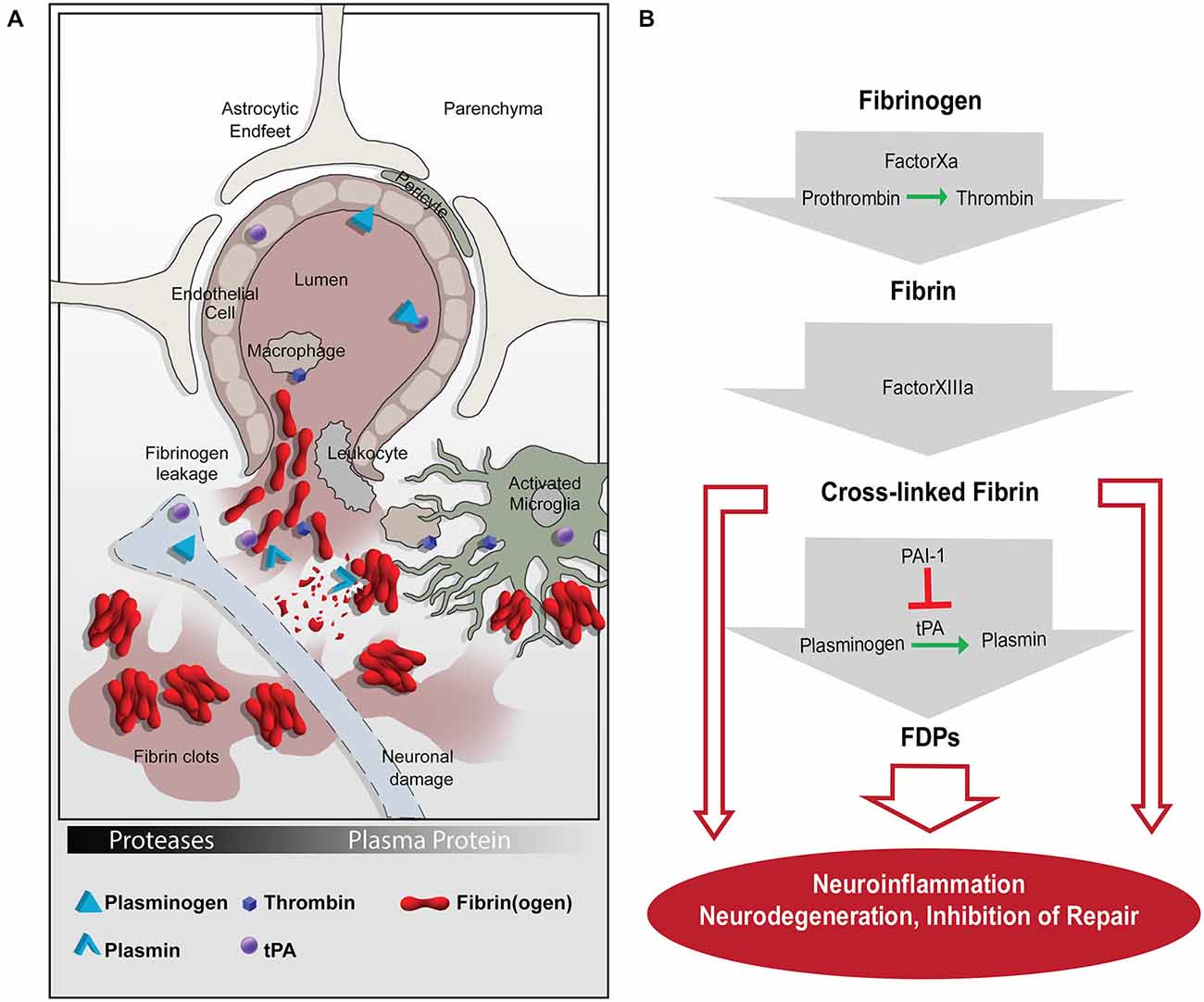

The pivotal fibrinolytic functions of the PA system were discovered in Plg-deficient mice, which show impaired wound healing, severe thrombosis, early lethality and delayed nerve regeneration (Bugge et al., 1995; Akassoglou et al., 2000). Interestingly, this phenotype is rescued by fibrinogen deficiency, suggesting that fibrin(ogen) is the main physiologic substrate for plasmin in vivo (Bugge et al., 1996; Akassoglou et al., 2000). Besides binding plasmin, fibrin(ogen) interacts with cell surface receptors expressed by different cell types in the CNS, including microglia (Adams et al., 2007; Davalos et al., 2012; Ryu et al., 2015), neurons (Schachtrup et al., 2007), astrocytes (Schachtrup et al., 2010) and Schwann cells (Akassoglou et al., 2002; reviewed in Davalos and Akassoglou, 2012; Ryu et al., 2009). Thus, fibrinogen acts as a molecular switch linking the PA system to activation of cell intrinsic signaling pathways involved in immune response and CNS homeostasis/neuronal functions (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The coagulation and proteolytic cascades at the neurovascular interface. (A) Fibrinogen leakage in the central nervous system (CNS) and activation of the plasminogen activation (PA) system occur following blood-brain-barrier (BBB) disruption. The molecular network of fibrin and the PA system enable inflammation and neurodegeneration via activation of microglia, macrophages, and leukocytes. (B) A series of proteolytic events converts extravasated fibrinogen into insoluble fibrin, which can be cleaved into FDPs. Fibrin and FDPs interact with cellular receptors to induce inflammation, degeneration, and repair inhibition in the nervous system. tPA, tissue plasminogen activator; PAI-1, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1; FDPs, fibrin degradation products.

The multifaceted and central functions of fibrin(ogen) in the PA system are highlighted by studies showing that fibrin acts: (1) as a main substrate of plasmin during fibrinolysis; (2) as a feed-back regulator of PA by binding tPA/PAI-1 or Plg directly; and (3) as a signaling molecule for cell activation in the CNS. By highlighting the PA system as a molecular link between coagulation, fibrinolysis and inflammation, this review will focus on cellular mechanisms and molecular signaling pathways driven by fibrin deposition and fibrinolysis in the CNS, specifically at the neurovascular unit (NVU).

Under healthy conditions, plasma proteins like fibrinogen and Plg are not found in the brain parenchyma—a relatively immune-priviledged environment sealed by the selectively permeable blood-brain-barrier (BBB). Activation of the Plg system in the CNS parenchyma occurs in response to BBB disruption in which components from the blood enter the brain milieu (Figure 1). The BBB is an emergent property of the brain vasculature controlled by endothelial cells ensheathed by pericytes and astrocytic endfeet. The brain vasculature with an intact BBB plays essential roles in maintaining flow of nutrients into the brain, as well as protecting the brain from invasinto the brain, as well as protecting the brain from invasion by toxins, pathogens and inflammatory cells (Zlokovic, 2008; Daneman and Prat, 2015).

BBB opening can result from tight junction (TJ) complex disassembly or downregulation, increased transcellular transport, or physical damage to the blood vessel (Stamatovic et al., 2008). Disruption of the BBB is observed in a variety of neurological conditions in humans and in their animal models, such as stroke (Elster and Moody, 1990; Belayev et al., 1996), traumatic brain injury (Tanno et al., 1992; Conti et al., 2004; Shlosberg et al., 2010), epilepsy (Sokrab et al., 1990; Liu et al., 2012) and chronic neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration, including multiple sclerosis (MS; Paterson, 1976; Grossman et al., 1988; Miller et al., 1988; Adams et al., 2004; Gaitán et al., 2011) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD; van Oijen et al., 2005; Ahn et al., 2010; Cortes-Canteli et al., 2010; Oh et al., 2014b). BBB opening is also a hallmark of normal aging (Tucsek et al., 2014; Montagne et al., 2015). Indeed, contrast-enhanced MRI showed an age-dependent BBB breakdown in the hippocampus, a region critical for learning and memory that is affected in neurodegenerative diseases, such as AD (Montagne et al., 2015).

Multiple components of the PA system and in particular tPA function in BBB homeostasis (Vivien et al., 2011). tPA opens the BBB via mechanisms that include activation of platelet-derived growth factor-CC (PDGF-CC) signaling (Su et al., 2008), astrocyte remodeling through plasmin (Niego et al., 2012) and phosphorylation of BBB proteins claudin-5 and occludin (Kaur et al., 2011), as well as through a mechanism independent of its catalytic activity toward Plg (Abu Fanne et al., 2010). tPA may also open the BBB via low density lipoprotein receptor–related protein 1 (LRP-1) signaling (Yepes et al., 2003), which may be mediated by matrix metalloproteinase (MMPs; Wang et al., 2003; Lakhan et al., 2013). In contrast, PAI-1, the primary inhibitor of tPA, enhances barrier tightness in in vitro BBB models (Dohgu et al., 2011). tPA may also regulate the BBB through annexin-2 (Cristante et al., 2013). These studies show that tPA regulates several potentially overlapping pathways involved in BBB dysfunction. Evidence for tPA in maintaining vascular integrity can also be found in the clinic, as tPA treatment for thrombotic stroke increased hemorrhagic risk (Fugate and Rabinstein, 2014). Similarly, anticoagulants, such as clopidogrel, which inhibit platelet functions, increase the risk of brain hemorrhage after a stroke (Morrow et al., 2012).

In addition to the fibrinolytic system, molecular players promoting clot formation also regulate the BBB. Thrombin, the catalyst of fibrin formation, may disrupt the BBB (Lee et al., 1997; Liu et al., 2010) and in a human brain endothelial cell line can induce upregulation of intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1), Vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) and cytokines chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 (CCL2) and CX3CL1 (Alabanza and Bynoe, 2012). Fibrinogen increases endothelial cell permeability in vitro, in part by reducing expression of TJ proteins (Tyagi et al., 2008; Patibandla et al., 2009). The likelihood of BBB opening in response to fibrinogen may be increased under pathological conditions in which fibrinogen/fibrin accumulates on the blood vessel wall and in the parenchyma. A positive feedback loop whereby a precipitating event transiently opens the BBB, leading to the activation of the Plg and coagulation systems in the CNS, the components of which then further act to exacerbates BBB dysfunction can be envisaged. In sum, many pathologies are associated with BBB breakdown, indicated by persistent fibrin deposition inside the CNS. Therefore, fibrin has emerged as a potential target for development of diagnostic tools and therapeutic strategies (Conti et al., 2004; Adams et al., 2007; Craig-Schapiro et al., 2011; Ahn et al., 2014; Davalos et al., 2014).

Insofar as fibrin is necessary to stop hemorrhage, and plasmin can remove fibrin clots that block vital blood flow, the PA system has a beneficial role in the brain. However, dysregulation of the PA and coagulation systems are linked to inflammation, which is a common hallmark of many CNS pathologies, including the autoimmune disease MS (East et al., 2005; Marik et al., 2007; Han et al., 2008), as well as other chronic neuroimmune and neurodegenerative disorders (van Oijen et al., 2005; Paul et al., 2007).

MS is an autoimmune disease in which the myelin-producing oligodendrocytes are targeted for destruction by the immune system. Histopathology of human brain tissue shows focal fibrin deposition in MS plaques, indicative of perivascular inflammation and BBB disruption (Gay and Esiri, 1991; Kirk et al., 2003; Vos et al., 2005; Marik et al., 2007) that is also observed in MS mouse models (Paterson et al., 1987; Adams et al., 2004, 2007). Proteomic analysis of chronic active plaques from MS patients revealed a set of coagulation proteins uniquely present in active plaques, suggesting a role for the coagulation cascade in the development of MS pathology (Han et al., 2008). Indeed, MS lesions have increased levels of PAI-1 and less fibrin degradation and, thus, more sustained fibrin deposition than normal control tissue (Gveric et al., 2003). Fibrin depletion provides protection in a wide range of MS mouse models (Paterson, 1976; Akassoglou et al., 2004; Adams et al., 2007; Yang et al., 2011; Davalos et al., 2012). Studies of other Plg cascade components also support the hypothesis that fibrin deposition is a major instigator of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE). tPA−/− mice have increased disease severity in EAE, which may be due to accumulated fibrin deposits and/or loss of fibrin-independent tPA functions in the CNS (Lu et al., 2002; East et al., 2005). Exacerbation of demyelination in tPA−/− or plg−/− mice after peripheral nerve injury is fibrin-dependent, since fibrin depletion rescues the damaging effects of tPA or Plg deficiency (Akassoglou et al., 2000). Furthermore, PAI-1−/− mice have reduced EAE severity associated with increased fibrinolysis (East et al., 2008). It is important to underscore that fibrin and the tPA/plasmin system act in concert to exert the full effect of vascular-driven neuroinflammation. For example, inflammation and fibrin-induced neurodegeneration are reduced in plg−/− mice, suggesting that multiple molecular players from the coagulation and fibrinolytic systems are needed for a full inflammatory and degenerative response (Hultman et al., 2014).

Emerging evidence suggests a pivotal role of fibrin in the regulation of CNS innate and adaptive immune responses (Davalos et al., 2012; Ryu et al., 2015; Table 1). Fibrin(ogen) interactions with microglia, macrophages, and neutrophils via integrin receptor CD11b/CD18 (also known as Mac-1, Complement Receptor 3 or integrin αMβ2) were identified as direct activation pathways of innate immune response (Davalos and Akassoglou, 2012). Extravascular fibrin deposition stimulates recruitment and perivascular clustering of microglia in EAE lesions (Davalos et al., 2012), while deletion of fibrin or blockade of fibrin signaling protects from microglial activation and axonal damage in EAE (Akassoglou et al., 2004; Adams et al., 2007). A recombinant mutant thrombin analog similarly ameliorated EAE progression, corroborating the regulatory functions of thrombin-mediated fibrinogen/fibrin conversion during neuroinflammation (Verbout et al., 2015). Fibrin-induced activation of microglia via CD11b/CD18 induced secretion of cytokines and chemokines that stimulate recruitment of peripheral monocytes/macrophages (Ryu et al., 2015). Importantly, fibrin in the CNS white matter was sufficient to induce the infiltration and activation of myelin-specific T cells, suggesting a fibrin-induced innate immune-mediated pathway that triggers CNS autoimmunity (Ryu et al., 2015). Potential direct effects of fibrin on T cells might also play a role in autoimmune responses (Takada et al., 2010). Moreover, PA-mediated opening of the BBB and extracellular proteolysis facilitates T-cell extravasation and migration (Cuzner and Opdenakker, 1999; Yepes et al., 2003). Genetic and pharmacologic evidence point to CD11b/CD18 as the major receptor mediating the in vivo proinflammatory effects of fibrin in the CNS (Adams et al., 2007; Davalos et al., 2012; Ryu et al., 2015). In addition to CD11b/CD18, in vitro evidence indicates a role for toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) in fibrin-induced macrophage activation (Smiley et al., 2001). Moreover, in vitro evidence suggests a role for fibrinogen in neutrophil activation (Skogen et al., 1988; Rubel et al., 2001). The relative contributions of these proinflammatory pathways in the CNS in vivo remain to be determined. Overall, fibrin(ogen) and tPA/plasmin can be potent modulators of neuroinflammation.

The PA system plays a critical role in normal cognitive function (e.g., regulation of synaptic plasticity) and neural dysfunction (Melchor and Strickland, 2005). For example, tPA can modulate neurotoxicity as tPA−/− mice exhibit less neuronal death after hippocampal kainate injection or after ethanol withdrawal, both of which induce neurodegeneration (Tsirka et al., 1995; Skrzypiec et al., 2009). Unlike tPA and plasmin, fibrinogen is not present in the healthy brain. However, fibrinogen is detected in the brains of patients with MS (Gay and Esiri, 1991; Kirk et al., 2003; Vos et al., 2005; Marik et al., 2007), schizophrenia (Körschenhausen et al., 1996), HIV-encephalopathy (Dallasta et al., 1999), ischemia (Massberg et al., 1999), AD (Paul et al., 2007; Ryu and McLarnon, 2009) and normal aging (Viggars et al., 2011), all conditions which have transient or long-lasting BBB opening.

AD is a common aging-related neurodegenerative disease of dementia and is characterized by extracellular aggregates of beta-amyloid (Aβ) plaques and intracellular neurofibrillary tangles of tau protein (Huang and Mucke, 2012). Co-localization of microhemorrhages and amyloid plaques in human AD brains suggests that bleeding can precipitate or promote plaque deposition (Cullen et al., 2006). Fibrin deposits colocalize with areas of neurite dystrophy in human AD tissue and AD mouse models (Cortes-Canteli et al., 2015). Individuals with high levels of plasma fibrinogen have an increased risk for developing AD and dementia (van Oijen et al., 2005; Xu et al., 2008). Furthermore, AD patients with two alleles of apoE ε4, which is the strongest genetic risk factor for AD (Mahley and Huang, 2012), have significantly more fibrin deposition than AD patients with ε2 or ε3 apoE alleles (Hultman et al., 2013). Fibrin depletion in AD model mice via genetic and pharmacological methods ameliorates the disease pathology and cognitive impairment (Paul et al., 2007; Cortes-Canteli et al., 2010, 2015). AD model mice lacking one allele for tPA develop more severe Aβ plaque deposition and cognitive impairment (Oh et al., 2014a). This effect may be due to reduced fibrinolysis, but there is also evidence that tPA is neuroprotective via a fibrin-independent mechanism by promoting Aβ degradation (Melchor et al., 2003), perhaps by activating microglia to phagocytose Aβ plaques. The physical association of fibrin and Aβ impairs fibrin degradation, which has the potential to induce chronic inflammation (Ahn et al., 2010; Cortes-Canteli et al., 2010; Zamolodchikov and Strickland, 2012). This interaction seems to be instrumental in the disease process as administration of a peptide that inhibits fibrin-Aβ interaction rescues cognitive decline in AD mice (Ahn et al., 2014). An important question to address is whether Aβ plaques associated with fibrin exacerbate neurodegeneration.

Studies indicate that fibrinogen and the PA system also impacts nervous system repair through regulation of neuron-glia interactions. Regeneration in the CNS may be limited by the development of astrogliosis via fibrin-induced transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) signaling in astrocytes (Schachtrup et al., 2010) or by fibrinogen-mediated inhibition of neurite outgrowth (Schachtrup et al., 2007; Table 1). In the peripheral nervous system, fibrin impedes remyelination by inhibiting Schwann cell migration and differentiation into myelinating cells (Akassoglou et al., 2002, 2003). The increased severity of nerve injury in tPA−/− or plg−/− knock-out mice in the sciatic nerve crush model is rescued by genetic or pharmacological fibrinogen depletion (Akassoglou et al., 2000; Siconolfi and Seeds, 2001), supporting the concept that fibrin accumulation is an important trigger for inhibition of remyelination. While these findings are highly suggestive of new pathways for fibrin and tPA/plasmin in regeneration, more work will be needed to determine their contribution as inhibitors of nervous system repair.

Emerging evidence from the fields of neuroscience, immunology, and vascular biology have aimed the spotlight on fibrin and the fibrinolytic system for their pleiotropic functions in neurological diseases. Although current evidence points to fibrin as a major contributor to neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration, it is possible that other components of the coagulation cascade are activated upon neurologic disease and play a role in CNS diseases via fibrin-dependent and potentially fibrin-independent mechanisms (Akassoglou, 2015). For example, a novel molecular probe for thrombin identified increased thrombin activity in animal models of stroke (Chen et al., 2012) and MS (Davalos et al., 2014). In accordance, depletion of thrombin by anti-coagulants inhibits fibrin formation and is protective in MS animal models (Adams et al., 2007; Han et al., 2008; Davalos et al., 2012). It is now timely for the fields of neuroscience and neurology to explore the contribution of the coagulation cascade in inflammatory, degenerative, and repair processes in the CNS.

Fibrin degradation products (FDPs) are commonly used as biomarkers to assess the severity of trauma after injury, in sepsis, or myocardial infract. Components of the coagulation cascade and FDPs have been detected in MS patients (Aksungar et al., 2008; Han et al., 2008; Liguori et al., 2014), in patients with mild cognitive impairment (Xu et al., 2008), and in human AD (Cortes-Canteli et al., 2015; Zamolodchikov et al., 2015). However, most of these studies have been performed in small population cohorts without availability of imaging data, response to treatments, and disease duration. Studies in large patient cohorts would be required to assess whether components of coagulation or the fibrinolytic cascade correlate with disease progression in neurologic diseases. Although coagulation and fibrinolysis could trigger and perpetuate neurologic disease, animal models of vascular-driven inflammation and neurodegeneration are currently lacking. Inducing neuroinflammation in the CNS in Fibrinogen-induced encephalomyelitis (FIE) by introducing fibrinogen in the brain (Ryu et al., 2015), or perhaps by manipulating PA, or by transgenic or pharmacological models that increase BBB permeability could lead to vascular-driven experimental settings to study disease pathogenesis in the CNS.

Several FDA-approved drugs target different aspects of the coagulation cascade leading to reduced fibrin formation. Although new generation anticoagulants have reduced hemorrhagic effects, target-based drug design would be preferable to selectively inhibit the pathogenic effects of coagulation in the CNS. Indeed, pharmacologic inhibition of fibrin interactions with CD11b/CD18 using a fibrin peptide suppressed EAE pathology without adverse effects in blood clotting (Adams et al., 2007; Davalos and Akassoglou, 2012). Future studies will determine whether pharmacologic reagents can be developed to selectively target the pathogenic effects of fibrin and perhaps other components of the coagulation cascade in the CNS without affecting their beneficial effects in blood clotting.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors are grateful to Gary Howard for excellent editorial assistance, to John Lewis for graphic design, and Jae Kyu Ryu for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by the DFG postdoctoral fellowship to SB, the American Heart Association postdoctoral fellowship to VAR, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke grants NS052189, NS51470, NS082976, the National Multiple Sclerosis Society RG 4985A3, Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, and Conrad N. Hilton Foundation MS Innovation Award to KA.

Akt, Protein kinase B; APC, Antigen-presenting cells; CCL2, Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2; CSPG, Chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan; CXCL10, C-X-C motif chemokine 10; EAE, Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis; EGFR, Epidermal growth factor receptor; ERK1/2, Extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2; FIE, Fibrinogen-induced encephalomyelitis; ICAM-1, Intercellular adhesion molecule 1; MCP-1, Monocyte chemoattractant protein 1; MEK, Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 1; NF-κB, Nuclear factor “kappa-light-chain-enhancer” of activated B-cells; PI3K, Phosphoinositide 3-kinase; ROS, Reactive oxygen species; Smad2, SMAD family member 2; TCR, T-cell receptor; TGFβ, Transforming growth factor beta; TJ, Tight junction; TLR4, Toll-like receptor 4; VCAM-1, Vascular cell adhesion molecule-1; VE, Vascular endothelial.

Abu Fanne, R., Nassar, T., Yarovoi, S., Rayan, A., Lamensdorf, I., Karakoveski, M., et al. (2010). Blood-brain barrier permeability and tPA-mediated neurotoxicity. Neuropharmacology 58, 972–980. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2009.12.017

Adams, R. A., Bauer, J., Flick, M. J., Sikorski, S. L., Nuriel, T., Lassmann, H., et al. (2007). The fibrin-derived gamma377–395 peptide inhibits microglia activation and suppresses relapsing paralysis in central nervous system autoimmune disease. J. Exp. Med. 204, 571–582. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061931

Adams, R. A., Passino, M., Sachs, B. D., Nuriel, T., and Akassoglou, K. (2004). Fibrin mechanisms and functions in nervous system pathology. Mol. Interv. 4, 163–176. doi: 10.1124/mi.4.3.6

Ahn, H. J., Glickman, J. F., Poon, K. L., Zamolodchikov, D., Jno-Charles, O. C., Norris, E. H., et al. (2014). A novel Abeta-fibrinogen interaction inhibitor rescues altered thrombosis and cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease mice. J. Exp. Med. 211, 1049–1062. doi: 10.1084/jem.20131751

Ahn, H. J., Zamolodchikov, D., Cortes-Canteli, M., Norris, E. H., Glickman, J. F., and Strickland, S. (2010). Alzheimer’s disease peptide beta-amyloid interacts with fibrinogen and induces its oligomerization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 107, 21812–21817. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010373107

Akassoglou, K. (2015). Coagulation takes center stage in inflammation. Blood 125, 419–420. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-11-609222

Akassoglou, K., Adams, R. A., Bauer, J., Mercado, P., Tseveleki, V., Lassmann, H., et al. (2004). Fibrin depletion decreases inflammation and delays the onset of demyelination in a tumor necrosis factor transgenic mouse model for multiple sclerosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 101, 6698–6703. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0303859101

Akassoglou, K., Akpinar, P., Murray, S., and Strickland, S. (2003). Fibrin is a regulator of schwann cell migration after sciatic nerve injury in mice. Neurosci. Lett. 338, 185–188. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)01387-3

Akassoglou, K., Kombrinck, K. W., Degen, J. L., and Strickland, S. (2000). Tissue plasminogen activator-mediated fibrinolysis protects against axonal degeneration and demyelination after sciatic nerve injury. J. Cell Biol. 149, 1157–1166. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.5.1157

Akassoglou, K., Yu, W. M., Akpinar, P., and Strickland, S. (2002). Fibrin inhibits peripheral nerve remyelination by regulating schwann cell differentiation. Neuron 33, 861–875. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00617-7

Aksungar, F. B., Topkaya, A. E., Yildiz, Z., Sahin, S., and Turk, U. (2008). Coagulation status and biochemical and inflammatory markers in multiple sclerosis. J. Clin. Neurosci. 15, 393–397. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2007.02.090

Alabanza, L. M., and Bynoe, M. S. (2012). Thrombin induces an inflammatory phenotype in a human brain endothelial cell line. J. Neuroimmunol. 245, 48–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2012.02.004

Belayev, L., Busto, R., Zhao, W., and Ginsberg, M. D. (1996). Quantitative evaluation of blood-brain barrier permeability following middle cerebral artery occlusion in rats. Brain Res. 739, 88–96. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)00815-3

Bignami, A., Cella, G., and Chi, N. H. (1982). Plasminogen activators in rat neural tissues during development and in wallerian degeneration. Acta Neuropathol. 58, 224–228. doi: 10.1007/bf00690805

Bugge, T. H., Flick, M. J., Daugherty, C. C., and Degen, J. L. (1995). Plasminogen deficiency causes severe thrombosis but is compatible with development and reproduction. Genes Dev. 9, 794–807. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.7.794

Bugge, T. H., Kombrinck, K. W., Flick, M. J., Daugherty, C. C., Danton, M. J., and Degen, J. L. (1996). Loss of fibrinogen rescues mice from the pleiotropic effects of plasminogen deficiency. Cell 87, 709–719. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81390-2

Carroll, P. M., Tsirka, S. E., Richards, W. G., Frohman, M. A., and Strickland, S. (1994). The mouse tissue plasminogen activator gene 5’ flanking region directs appropriate expression in development and a seizure-enhanced response in the CNS. Development 120, 3173–3183.

Castellino, F. J., and Ploplis, V. A. (2005). Structure and function of the plasminogen/plasmin system. Thromb. Haemost. 93, 647–654. doi: 10.1160/th04-12-0842

Cesarman-Maus, G., and Hajjar, K. A. (2005). Molecular mechanisms of fibrinolysis. Br. J. Haematol. 129, 307–321. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05444.x

Chen, B., Friedman, B., Whitney, M. A., Winkle, J. A., Lei, I. F., Olson, E. S., et al. (2012). Thrombin activity associated with neuronal damage during acute focal ischemia. J. Neurosci. 32, 7622–7631. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.0369-12.2012

Conti, A., Sanchez-Ruiz, Y., Bachi, A., Beretta, L., Grandi, E., Beltramo, M., et al. (2004). Proteome study of human cerebrospinal fluid following traumatic brain injury indicates fibrin(ogen) degradation products as trauma-associated markers. J. Neurotrauma 21, 854–863. doi: 10.1089/0897715041526212

Cortes-Canteli, M., Mattei, L., Richards, A. T., Norris, E. H., and Strickland, S. (2015). Fibrin deposited in the Alzheimer’s disease brain promotes neuronal degeneration. Neurobiol. Aging 36, 608–617. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.10.030

Cortes-Canteli, M., Paul, J., Norris, E. H., Bronstein, R., Ahn, H. J., Zamolodchikov, D., et al. (2010). Fibrinogen and beta-amyloid association alters thrombosis and fibrinolysis: a possible contributing factor to Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron 66, 695–709. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.05.014

Craig-Schapiro, R., Kuhn, M., Xiong, C., Pickering, E. H., Liu, J., Misko, T. P., et al. (2011). Multiplexed immunoassay panel identifies novel CSF biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis and prognosis. PLoS One 6:e18850. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018850

Cristante, E., McArthur, S., Mauro, C., Maggioli, E., Romero, I. A., Wylezinska-Arridge, M., et al. (2013). Identification of an essential endogenous regulator of blood-brain barrier integrity and its pathological and therapeutic implications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 110, 832–841. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209362110

Cullen, K. M., Kócsi, Z., and Stone, J. (2006). Microvascular pathology in the aging human brain: evidence that senile plaques are sites of microhaemorrhages. Neurobiol. Aging 27, 1786–1796. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.10.016

Cuzner, M. L., and Opdenakker, G. (1999). Plasminogen activators and matrix metalloproteases, mediators of extracellular proteolysis in inflammatory demyelination of the central nervous system. J. Neuroimmunol. 94, 1–14. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(98)00241-0

Dallasta, L. M., Pisarov, L. A., Esplen, J. E., Werley, J. V., Moses, A. V., Nelson, J. A., et al. (1999). Blood-brain barrier tight junction disruption in human immunodeficiency virus-1 encephalitis. Am. J. Pathol. 155, 1915–1927. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)65511-3

Daneman, R., and Prat, A. (2015). The blood-brain barrier. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 7:a020412. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a020412

Davalos, D., and Akassoglou, K. (2012). Fibrinogen as a key regulator of inflammation in disease. Semin. Immunopathol. 34, 43–62. doi: 10.1007/s00281-011-0290-8

Davalos, D., Baeten, K. M., Whitney, M. A., Mullins, E. S., Friedman, B., Olson, E. S., et al. (2014). Early detection of thrombin activity in neuroinflammatory disease. Ann. Neurol. 75, 303–308. doi: 10.1002/ana.24078

Davalos, D., Ryu, J. K., Merlini, M., Baeten, K. M., Le Moan, N., Petersen, M. A., et al. (2012). Fibrinogen-induced perivascular microglial clustering is required for the development of axonal damage in neuroinflammation. Nat. Commun. 3:1227. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2230

Dohgu, S., Takata, F., Matsumoto, J., Oda, M., Harada, E., Watanabe, T., et al. (2011). Autocrine and paracrine up-regulation of blood-brain barrier function by plasminogen activator inhibitor-1. Microvasc. Res. 81, 103–107. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2010.10.004

East, E., Baker, D., Pryce, G., Lijnen, H. R., Cuzner, M. L., and Gverić, D. (2005). A role for the plasminogen activator system in inflammation and neurodegeneration in the central nervous system during experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. Am. J. Pathol. 167, 545–554. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)62996-3

East, E., Gverić, D., Baker, D., Pryce, G., Lijnen, H. R., and Cuzner, M. L. (2008). Chronic relapsing experimental allergic encephalomyelitis (CREAE) in plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 knockout mice: the effect of fibrinolysis during neuroinflammation. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 34, 216–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2007.00889.x

Elster, A. D., and Moody, D. M. (1990). Early cerebral infarction: gadopentetate dimeglumine enhancement. Radiology 177, 627–632. doi: 10.1148/radiology.177.3.2243961

Fugate, J. E., and Rabinstein, A. A. (2014). Update on intravenous recombinant tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. Mayo Clin. Proc. 89, 960–972. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2014.03.001

Gaitán, M. I., Shea, C. D., Evangelou, I. E., Stone, R. D., Fenton, K. M., Bielekova, B., et al. (2011). Evolution of the blood-brain barrier in newly forming multiple sclerosis lesions. Ann. Neurol. 70, 22–29. doi: 10.1002/ana.22472

Gay, D., and Esiri, M. (1991). Blood-brain barrier damage in acute multiple sclerosis plaques. An immunocytological study. Brain 114, 557–572. doi: 10.1093/brain/114.1.557

Grossman, R. I., Braffman, B. H., Brorson, J. R., Goldberg, H. I., Silberberg, D. H., and Gonzalez-Scarano, F. (1988). Multiple sclerosis: serial study of gadolinium-enhanced MR imaging. Radiology 169, 117–122. doi: 10.1148/radiology.169.1.3420246

Gveric, D., Herrera, B., Petzold, A., Lawrence, D. A., and Cuzner, M. L. (2003). Impaired fibrinolysis in multiple sclerosis: a role for tissue plasminogen activator inhibitors. Brain 126, 1590–1598. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg167

Han, M. H., Hwang, S. I., Roy, D. B., Lundgren, D. H., Price, J. V., Ousman, S. S., et al. (2008). Proteomic analysis of active multiple sclerosis lesions reveals therapeutic targets. Nature 451, 1076–1081. doi: 10.1038/nature06559

Huang, Y., and Mucke, L. (2012). Alzheimer mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Cell 148, 1204–1222. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.040

Hultman, K., Cortes-Canteli, M., Bounoutas, A., Richards, A. T., Strickland, S., and Norris, E. H. (2014). Plasmin deficiency leads to fibrin accumulation and a compromised inflammatory response in the mouse brain. J. Thromb. Haemost. 12, 701–712. doi: 10.1111/jth.12553

Hultman, K., Strickland, S., and Norris, E. H. (2013). The APOE varepsilon4/varepsilon4 genotype potentiates vascular fibrin(ogen) deposition in amyloid-laden vessels in the brains of Alzheimer’s disease patients. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 33, 1251–1258. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.76

Ill-Raga, G., Palomer, E., Ramos-Fernández, E., Guix, F. X., Bosch-Morató, M., Guivernau, B., et al. (2015). Fibrinogen nitrotyrosination after ischemic stroke impairs thrombolysis and promotes neuronal death. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1852, 421–428. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2014.12.007

Jennewein, C., Tran, N., Paulus, P., Ellinghaus, P., Eble, J. A., and Zacharowski, K. (2011). Novel aspects of fibrin(ogen) fragments during inflammation. Mol. Med. 17, 568–573. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2010.00146

Kaczmarek, E., Lee, M. H., and McDonagh, J. (1993). Initial interaction between fibrin and tissue plasminogen activator (t-PA). The Gly-Pro-Arg-Pro binding site on fibrin(ogen) is important for t-PA activity. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 2474–2479.

Kaur, J., Tuor, U. I., Zhao, Z., and Barber, P. A. (2011). Quantitative MRI reveals the elderly ischemic brain is susceptible to increased early blood-brain barrier permeability following tissue plasminogen activator related to claudin 5 and occludin disassembly. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 31, 1874–1885. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2011.79

Kim, P. Y., Tieu, L. D., Stafford, A. R., Fredenburgh, J. C., and Weitz, J. I. (2012). A high affinity interaction of plasminogen with fibrin is not essential for efficient activation by tissue-type plasminogen activator. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 4652–4661. doi: 10.1074/jbc.m111.317719

Kirk, J., Plumb, J., Mirakhur, M., and McQuaid, S. (2003). Tight junctional abnormality in multiple sclerosis white matter affects all calibres of vessel and is associated with blood-brain barrier leakage and active demyelination. J. Pathol. 201, 319–327. doi: 10.1002/path.1434

Körschenhausen, D. A., Hampel, H. J., Ackenheil, M., Penning, R., and Muller, N. (1996). Fibrin degradation products in post mortem brain tissue of schizophrenics: a possible marker for underlying inflammatory processes. Schizophr. Res. 19, 103–109. doi: 10.1016/0920-9964(95)00073-9

Kwaan, H. C. (2014). From fibrinolysis to the plasminogen-plasmin system and beyond: a remarkable growth of knowledge, with personal observations on the history of fibrinolysis. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 40, 585–591. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1383545

Lakhan, S. E., Kirchgessner, A., Tepper, D., and Leonard, A. (2013). Matrix metalloproteinases and blood-brain barrier disruption in acute ischemic stroke. Front. Neurol. 4:32. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2013.00032

Lee, K. R., Kawai, N., Kim, S., Sagher, O., and Hoff, J. T. (1997). Mechanisms of edema formation after intracerebral hemorrhage: effects of thrombin on cerebral blood flow, blood-brain barrier permeability and cell survival in a rat model. J. Neurosurg. 86, 272–278. doi: 10.3171/jns.1997.86.2.0272

Liguori, M., Qualtieri, A., Tortorella, C., Direnzo, V., Bagala, A., Mastrapasqua, M., et al. (2014). Proteomic profiling in multiple sclerosis clinical courses reveals potential biomarkers of neurodegeneration. PLoS One 9:e103984. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103984

Liu, D. Z., Ander, B. P., Xu, H., Shen, Y., Kaur, P., Deng, W., et al. (2010). Blood-brain barrier breakdown and repair by Src after thrombin-induced injury. Ann. Neurol. 67, 526–533. doi: 10.1002/ana.21924

Liu, J. Y., Thom, M., Catarino, C. B., Martinian, L., Figarella-Branger, D., Bartolomei, F., et al. (2012). Neuropathology of the blood-brain barrier and pharmaco-resistance in human epilepsy. Brain 135, 3115–3133. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws147

Lu, W., Bhasin, M., and Tsirka, S. E. (2002). Involvement of tissue plasminogen activator in onset and effector phases of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. J. Neurosci. 22, 10781–10789.

Mahley, R. W., and Huang, Y. (2012). Apolipoprotein e sets the stage: response to injury triggers neuropathology. Neuron 76, 871–885. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.11.020

Marik, C., Felts, P. A., Bauer, J., Lassmann, H., and Smith, K. J. (2007). Lesion genesis in a subset of patients with multiple sclerosis: a role for innate immunity? Brain 130, 2800–2815. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm236

Massberg, S., Enders, G., Matos, F. C., Tomic, L. I., Leiderer, R., Eisenmenger, S., et al. (1999). Fibrinogen deposition at the postischemic vessel wall promotes platelet adhesion during ischemia-reperfusion in vivo. Blood 94, 3829–3838.

Melchor, J. P., Pawlak, R., and Strickland, S. (2003). The tissue plasminogen activator-plasminogen proteolytic cascade accelerates amyloid-beta (Abeta) degradation and inhibits Abeta-induced neurodegeneration. J. Neurosci. 23, 8867–8871.

Melchor, J. P., and Strickland, S. (2005). Tissue plasminogen activator in central nervous system physiology and pathology. Thromb. Haemost. 93, 655–660. doi: 10.1160/th04-12-0838

Miller, D. H., Rudge, P., Johnson, G., Kendall, B. E., Macmanus, D. G., Moseley, I. F., et al. (1988). Serial gadolinium enhanced magnetic resonance imaging in multiple sclerosis. Brain 111, 927–939. doi: 10.1093/brain/111.4.927

Montagne, A., Barnes, S. R., Sweeney, M. D., Halliday, M. R., Sagare, A. P., Zhao, Z., et al. (2015). Blood-brain barrier breakdown in the aging human hippocampus. Neuron 85, 296–302. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.12.032

Morrow, D. A., Braunwald, E., Bonaca, M. P., Ameriso, S. F., Dalby, A. J., Fish, M. P., et al. (2012). Vorapaxar in the secondary prevention of atherothrombotic events. N. Engl. J. Med. 366, 1404–1413. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200933

Muradashvili, N., Tyagi, N., Tyagi, R., Munjal, C., and Lominadze, D. (2011). Fibrinogen alters mouse brain endothelial cell layer integrity affecting vascular endothelial cadherin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 413, 509–514. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.07.133

Niego, B., Freeman, R., Puschmann, T. B., Turnley, A. M., and Medcalf, R. L. (2012). t-PA-specific modulation of a human blood-brain barrier model involves plasmin-mediated activation of the Rho kinase pathway in astrocytes. Blood 119, 4752–4761. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-07-369512

Oh, S. B., Byun, C. J., Yun, J. H., Jo, D. G., Carmeliet, P., Koh, J. Y., et al. (2014a). Tissue plasminogen activator arrests Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis. Neurobiol. Aging 35, 511–519. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.09.020

Oh, J., Lee, H. J., Song, J. H., Park, S. I., and Kim, H. (2014b). Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 as an early potential diagnostic marker for Alzheimer’s disease. Exp. Gerontol. 60, 87–91. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2014.10.004

Paterson, P. Y. (1976). Experimental allergic encephalomyelitis: role of fibrin deposition in immunopathogenesis of inflammation in rats. Fed. Proc. 35, 2428–2434.

Paterson, P. Y., Koh, C. S., and Kwaan, H. C. (1987). Role of the clotting system in the pathogenesis of neuroimmunologic disease. Fed. Proc. 46, 91–96.

Patibandla, P. K., Tyagi, N., Dean, W. L., Tyagi, S. C., Roberts, A. M., and Lominadze, D. (2009). Fibrinogen induces alterations of endothelial cell tight junction proteins. J. Cell. Physiol. 221, 195–203. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21845

Paul, J., Strickland, S., and Melchor, J. P. (2007). Fibrin deposition accelerates neurovascular damage and neuroinflammation in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Exp. Med. 204, 1999–2008. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070304

Qian, Z., Gilbert, M. E., Colicos, M. A., Kandel, E. R., and Kuhl, D. (1993). Tissue-plasminogen activator is induced as an immediate-early gene during seizure, kindling and long-term potentiation. Nature 361, 453–457. doi: 10.1038/361453a0

Rubel, C., Fernández, G. C., Dran, G., Bompadre, M. B., Isturiz, M. A., and Palermo, M. S. (2001). Fibrinogen promotes neutrophil activation and delays apoptosis. J. Immunol. 166, 2002–2010. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.3.2002

Ryu, J. K., Davalos, D., and Akassoglou, K. (2009). Fibrinogen signal transduction in the nervous system. J. Thromb. Haemost. 7(Suppl. 1), 151–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03438.x

Ryu, J. K., and McLarnon, J. G. (2009). A leaky blood-brain barrier, fibrinogen infiltration and microglial reactivity in inflamed Alzheimer’s disease brain. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 13, 2911–2925. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00434.x

Ryu, J. K., Petersen, M. A., Murray, S. G., Baeten, K. M., Meyer-Franke, A., Chan, J. P., et al. (2015). Blood coagulation protein fibrinogen promotes autoimmunity and demyelination via chemokine release and antigen presentation. Nat. Commun. 6:8164. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9164

Sappino, A. P., Madani, R., Huarte, J., Belin, D., Kiss, J. Z., Wohlwend, A., et al. (1993). Extracellular proteolysis in the adult murine brain. J. Clin. Invest. 92, 679–685. doi: 10.1172/jci116637

Schachtrup, C., Lu, P., Jones, L. L., Lee, J. K., Lu, J., Sachs, B. D., et al. (2007). Fibrinogen inhibits neurite outgrowth via beta3 integrin-mediated phosphorylation of the EGF receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 104, 11814–11819. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704045104

Schachtrup, C., Ryu, J. K., Helmrick, M. J., Vagena, E., Galanakis, D. K., Degen, J. L., et al. (2010). Fibrinogen triggers astrocyte scar formation by promoting the availability of active TGF-beta after vascular damage. J. Neurosci. 30, 5843–5854. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0137-10.2010

Shlosberg, D., Benifla, M., Kaufer, D., and Friedman, A. (2010). Blood-brain barrier breakdown as a therapeutic target in traumatic brain injury. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 6, 393–403. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2010.74

Siconolfi, L. B., and Seeds, N. W. (2001). Mice lacking tPA, uPA, or plasminogen genes showed delayed functional recovery after sciatic nerve crush. J. Neurosci. 21, 4348–4355.

Skogen, W. F., Senior, R. M., Griffin, G. L., and Wilner, G. D. (1988). Fibrinogen-derived peptide B beta 1–42 is a multidomained neutrophil chemoattractant. Blood 71, 1475–1479.

Skrzypiec, A. E., Maiya, R., Chen, Z., Pawlak, R., and Strickland, S. (2009). Plasmin-mediated degradation of laminin gamma-1 is critical for ethanol-induced neurodegeneration. Biol. Psychiatry 66, 785–794. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.05.021

Smiley, S. T., King, J. A., and Hancock, W. W. (2001). Fibrinogen stimulates macrophage chemokine secretion through toll-like receptor 4. J. Immunol. 167, 2887–2894. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.5.2887

Sokrab, T. E., Kalimo, H., and Johansson, B. B. (1990). Parenchymal changes related to plasma protein extravasation in experimental seizures. Epilepsia 31, 1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1990.tb05352.x

Stamatovic, S. M., Keep, R. F., and Andjelkovic, A. V. (2008). Brain endothelial cell-cell junctions: how to “open” the blood brain barrier. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 6, 179–192. doi: 10.2174/157015908785777210

Su, E. J., Fredriksson, L., Geyer, M., Folestad, E., Cale, J., Andrae, J., et al. (2008). Activation of PDGF-CC by tissue plasminogen activator impairs blood-brain barrier integrity during ischemic stroke. Nat. Med. 14, 731–737. doi: 10.1038/nm1787

Syrovets, T., and Simmet, T. (2004). Novel aspects and new roles for the serine protease plasmin. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 61, 873–885. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-3348-5

Takada, Y., Ono, Y., Saegusa, J., Mitsiades, C., Mitsiades, N., Tsai, J., et al. (2010). A T cell-binding fragment of fibrinogen can prevent autoimmunity. J. Autoimmun. 34, 453–459. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2009.11.017

Tanno, H., Nockels, R. P., Pitts, L. H., and Noble, L. J. (1992). Breakdown of the blood-brain barrier after fluid percussive brain injury in the rat. Part 1: distribution and time course of protein extravasation. J. Neurotrauma 9, 21–32. doi: 10.1089/neu.1992.9.21

Tsirka, S. E., Gualandris, A., Amaral, D. G., and Strickland, S. (1995). Excitotoxin-induced neuronal degeneration and seizure are mediated by tissue plasminogen activator. Nature 377, 340–344. doi: 10.1038/377340a0

Tucsek, Z., Toth, P., Sosnowska, D., Gautam, T., Mitschelen, M., Koller, A., et al. (2014). Obesity in aging exacerbates blood-brain barrier disruption, neuroinflammation and oxidative stress in the mouse hippocampus: effects on expression of genes involved in beta-amyloid generation and Alzheimer’s disease. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 69, 1212–1226. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glt177

Tyagi, N., Roberts, A. M., Dean, W. L., Tyagi, S. C., and Lominadze, D. (2008). Fibrinogen induces endothelial cell permeability. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 307, 13–22. doi: 10.1007/s11010-007-9579-2

van Oijen, M., Witteman, J. C., Hofman, A., Koudstaal, P. J., and Breteler, M. M. (2005). Fibrinogen is associated with an increased risk of alzheimer disease and vascular dementia. Stroke 36, 2637–2641. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000189721.31432.26

Verbout, N. G., Yu, X., Healy, L. D., Phillips, K. G., Tucker, E. I., Gruber, A., et al. (2015). Thrombin mutant W215A/E217A treatment improves neurological outcome and attenuates central nervous system damage in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Metab. Brain Dis. 30, 57–65. doi: 10.1007/s11011-014-9558-8

Viggars, A. P., Wharton, S. B., Simpson, J. E., Matthews, F. E., Brayne, C., Savva, G. M., et al. (2011). Alterations in the blood brain barrier in ageing cerebral cortex in relationship to alzheimer-type pathology: a study in the MRC-CFAS population neuropathology cohort. Neurosci. Lett. 505, 25–30. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.09.049

Vivien, D., Gauberti, M., Montagne, A., Defer, G., and Touzé, E. (2011). Impact of tissue plasminogen activator on the neurovascular unit: from clinical data to experimental evidence. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 31, 2119–2134. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2011.127

Vos, C. M., Geurts, J. J., Montagne, L., van Haastert, E. S., Bö, L., van der Valk, P., et al. (2005). Blood-brain barrier alterations in both focal and diffuse abnormalities on postmortem MRI in multiple sclerosis. Neurobiol. Dis. 20, 953–960. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.06.012

Wagner, O. F., de Vries, C., Hohmann, C., Veerman, H., and Pannekoek, H. (1989). Interaction between plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 (PAI-1) bound to fibrin and either tissue-type plasminogen activator (t-PA) or urokinase-type plasminogen activator (u-PA). Binding of t-PA/PAI-1 complexes to fibrin mediated by both the finger and the kringle-2 domain of t-PA. J. Clin. Invest. 84, 647–655. doi: 10.1172/jci114211

Wang, X., Lee, S. R., Arai, K., Tsuji, K., Rebeck, G. W., and Lo, E. H. (2003). Lipoprotein receptor-mediated induction of matrix metalloproteinase by tissue plasminogen activator. Nat. Med. 9, 1313–1317. doi: 10.1038/nm926

Xu, G., Zhang, H., Zhang, S., Fan, X., and Liu, X. (2008). Plasma fibrinogen is associated with cognitive decline and risk for dementia in patients with mild cognitive impairment. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 62, 1070–1075. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2007.01268.x

Yang, Y., Tian, S. J., Wu, L., Huang, D. H., and Wu, W. P. (2011). Fibrinogen depleting agent batroxobin has a beneficial effect on experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 31, 437–448. doi: 10.1007/s10571-010-9637-2

Yepes, M., Sandkvist, M., Moore, E. G., Bugge, T. H., Strickland, D. K., and Lawrence, D. A. (2003). Tissue-type plasminogen activator induces opening of the blood-brain barrier via the LDL receptor-related protein. J. Clin. Invest. 112, 1533–1540. doi: 10.1172/jci19212

Zamolodchikov, D., Chen, Z. L., Conti, B. A., Renné, T., and Strickland, S. (2015). Activation of the factor XII-driven contact system in Alzheimer’s disease patient and mouse model plasma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 112, 4068–4073. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1423764112

Zamolodchikov, D., and Strickland, S. (2012). Abeta delays fibrin clot lysis by altering fibrin structure and attenuating plasminogen binding to fibrin. Blood 119, 3342–3351. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-11-389668

Keywords: fibrinogen, blood-brain barrier, microglia, autoimmunity, neuroinflammation, neurodegeneration, multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer’s disease

Citation: Bardehle S, Rafalski VA and Akassoglou K (2015) Breaking boundaries—coagulation and fibrinolysis at the neurovascular interface. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 9:354. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2015.00354

Received: 30 July 2015; Accepted: 24 August 2015;

Published: 16 September 2015.

Edited by:

Daniel A. Lawrence, University of Michigan Medical School, USAReviewed by:

Robert Weissert, University of Regensburg, GermanyCopyright © 2015 Bardehle, Rafalski and Akassoglou. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution and reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Katerina Akassoglou, Gladstone Institute of Neurological Disease and Department of Neurology, University of California, San Francisco, 1650 Owens St., San Francisco, CA 94158, USA,a2FrYXNzb2dsb3VAZ2xhZHN0b25lLnVjc2YuZWR1

† These authors have contributed equally to this work.

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.