- 1Laboratory of Neurogenetics, Department of Molecular Neuroscience, UCL Institute of Neurology, London, UK

- 2Laboratory of Neurogenetics, Institute of Translational Pharmacology, National Research Council of Italy, Rome, Italy

Spinocerebellar Ataxia type 6 (SCA6) is an autosomal dominant neurodegenerative disease characterized by late onset, slowly progressive, mostly pure cerebellar ataxia. It is one of three allelic disorders associated to CACNA1A gene, coding for the Alpha1 A subunit of P/Q type calcium channel Cav2.1 expressed in the brain, particularly in the cerebellum. The other two disorders are Episodic Ataxia type 2 (EA2), and Familial Hemiplegic Migraine type 1 (FHM1). These disorders show distinct phenotypes that often overlap but have different pathogenic mechanisms. EA2 and FHM1 are due to mutations causing, respectively, a loss and a gain of channel function. SCA6, instead, is associated with short expansions of a polyglutamine stretch located in the cytoplasmic C-terminal tail of the protein. This domain has a relevant role in channel regulation, as well as in transcription regulation of other neuronal genes; thus the SCA6 CAG repeat expansion results in complex pathogenic molecular mechanisms reflecting the complex Cav2.1 C-terminus activity. We will provide a short review for an update on the SCA6 molecular mechanism.

Introduction

Spinocerebellar Ataxia type 6 (SCA6, OMIM 183086) is a neurodegenerative disease characterized by late onset, slowly progressive, mostly pure cerebellar ataxia sometimes preceded by an episodic phase showing dysarthria, nystagmus and vertigo (Jodice et al., 1997). SCA6 is one of three autosomal dominant disorders due to mutations of CACNA1A gene. The gene encodes for the pore forming α1A subunit of P/Q type calcium channels Cav2.1, responsible for initiation of synaptic transmission at fast synapses (Catterall, 2000). Other auxiliary subunits cooperate in channel regulation (Catterall, 2000). SCA6 is due to small expansions of a CAG repeat stretch in exon 47, expressed only in some of the numerous isoforms of the CACNA1A gene as a polyglutamine sequence at protein level (Zhuchenko et al., 1997). The α1A subunit is a four domain-containing transmembrane protein of about 280 KDa with cytoplasmic N- and C-terminal regions. The cytoplasmic C-terminus, a 75 KDa polypeptide, contains residues involved in channel inactivation and modulation by intracellular signaling proteins (Catterall, 2000). The C-tail plays regulatory roles in the gating and trafficking of the channel, as reported also for the Cav1 family (Catterall, 2010). For Episodic Ataxia type 2 (EA2, OMIM 108500) and Familial Hemiplegic Migraine type 1 (FHM1, OMIM 141500) the molecular mechanism is clearly defined, a loss and a gain of channel function respectively (Guida et al., 2001; Tottene et al., 2002). In SCA6 the type of mutation (the polyglutamine expansion), the protein affected (the pore forming subunit of the P/Q type calcium channel) and the location of the mutation (the cytoplasmic C-terminal tail of the α1A subunit) suggest a more complex pathogenesis of the disease as opposed to a simpler gain of function model. Currently there is no treatment for SCA6, and understanding the underlying mechanism of the disease can be crucial in order to find molecular targets for therapeutic treatments. This review is focused on updating the recent advances in our understanding of molecular mechanisms of SCA6 pathogenesis.

SCA6 as a Polyglutamine Disorder

SCA6 belongs to the group of autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxias (ADCAs) and, as with most ADCAs, the mutation is due to expansions of a polyglutamine repeat motif.

SCA6 shares features in common with other polyglutamine diseases, but differs in several aspects. The CACNA1A gene product is a membrane protein rather than a nuclear or cytoplasmic protein, as is the case in most polyglutamine disorders.

The formation of insoluble aggregates which leads to the production of intranuclear inclusions is the principal pathogenic feature in most of the polyglutamine diseases (Paulson, 1999). In SCA6, aggregates are rare, preferentially located in the cytoplasm as in SCA2 (Huynh et al., 2000; Ishiguro et al., 2010; Takahashi et al., 2013) and very rarely localizing to the nucleus in Purkinje cells (Kordasiewicz et al., 2006; Ishiguro et al., 2010). In SCA6 the normal repeat size ranges from 4 to 18 units (Zhuchenko et al., 1997) while that of the expanded alleles is from 20 to 33 repeats (Jodice et al., 1997; Yabe et al., 1998). Nineteen CAG repeats is considered an “intermediate allele”, predisposing to expansion into the abnormal range (Mariotti et al., 2001) or a susceptibility factor with variable penetrance and expression (Brenman, 2013). The pathological range falls within the distribution of normal alleles in other SCAs and below the threshold for polyglutamine aggregation, which typically is a number of units ranging from 35 to over 100 (Frontali et al., 1999). Furthermore, the small SCA6 repeat expansions are much more stable than in other polyglutamine disorders (Jodice et al., 1997; Zhuchenko et al., 1997).

A significant inverse correlation between age of disease onset and size of expanded alleles has been reported, as in other SCAs (Ishikawa et al., 1997; Zhuchenko et al., 1997; Maruyama et al., 2002), but an even closer correlation has been shown between the age of onset and the sum of CAG repeats in the normal and expanded alleles (Takahashi et al., 2004).

SCA6 as a Channelopathy

It is still unclear whether and how the SCA6 mutation exerts a pathological effect on the calcium channel function, aside from the weak toxic function of the polyglutamine expansion. Several studies attempting to determine the possible altered channel function reached highly variable, often conflicting results.

Matsuyama et al. (1999) studied the effect of 24, 30, or 40 polyglutamine expansions on channel properties in Baby Hamster Kidney (BHK) cells stably expressing α2δ and β1a auxiliary subunits, and first indicated that the 30–40 expanded polyglutamines directly alter channel function, causing a significant 8 mV hyperpolarizing shift in the voltage dependance of inactivation, which reduces the available channel population. This suggested that polyglutamine expansion in SCA6 leads to neuronal cell death and cerebellar atrophy through reduction in Ca2+ influx into Purkinje cells, while Ca2+ channels with 24 polyglutamines or fewer showed normal gating properties. Interestingly, Toru et al. (2000), in another study, detected a 6 mV hyperpolarizing shift in the voltage dependance of inactivation also using the 24 polyQ expanded allele, transfected into the HEK293 human cell expression system together with the human α2δ and β1a subunits. The crucial point of this experiment was that it has been performed using two splice variants of P/Q type Ca2+ channel exon 31+ and exon31− (Bourinet et al., 1999). The alternatively spliced CACNA1A gene exon 31 codes for two aminoacidic residues, asparagine and proline (NP) in the transmembrane domain IV. The resulting isoforms produce channels with distinct kinetics and generate P-type (NP−) and Q-type (NP+) channels expressed respectively in Purkinje and cerebellar granule cells. The negative shifts in voltage dependent inactivation were only observed in the variants of the P type Ca2+ channel NP−. These studies demonstrated that the effect of polyQ expansions on calcium influx results in reducing of Ca2+ entry into Purkinje cells (−NP isoform) and increasing Ca2+ entry into granule cells (+NP isoform). This provides an explanation for the selective Purkinje cell degeneration in SCA6. The hypothesis of SCA6 being a channelopathy was strongly supported by Restituito et al. (2000). They further elucidated the role of the different subtypes of the calcium channel subunits in determining the channel gating consequences of the mutation. In experiments performed in Xenopus oocytes, the SCA6 polyglutamine expansion shifted the voltage dependance of channel inactivation and the rate of inactivation only when expressed with the β4 subunit. In addition the mutation impairs the normal G-protein regulation of P/Q type Ca2+ channels, causing Purkinje cell degeneration through a possible gain-of-function mechanism with increased Ca2+ ion entry. Subsequently, studies in HEK293 cells stably expressing α2δ and β1 subunits showed that SCA6 Ca2+ channels do not have altered channel kinetics, but an increased current density attributable to a greater protein expression in the cellular membrane (Piedras-Rentería et al., 2001). In a follow up of these experiments, Chen and Piedras-Rentería (2007) obtained the same results using β2a or β4 auxiliary subunits, rather than the β1 subunit.

In summary, different model systems reached conflicting results. The isoforms of α1A subunit, the different auxiliary subunits and the cellular system seem to create the difference among the results obtained by different groups. On the other hand, studies performed on transgenic mice expressing polyQ expanded α1A subunit showed unchanged P/Q channel kinetics in cerebellar neurons (Saegusa et al., 2007; Watase et al., 2008).

SCA6 as Transcriptional Dysregulation

Additional studies show a relevant role of the α1A subunit whole intracytoplamic C-terminal tail in SCA6 pathogenesis. Kordasiewicz et al. (2006) found that the C-terminal tail, from both the wild type and the mutant, is cleaved from the full-length protein and transported to the Purkinje cell nuclei equally. The SCA6 glutamine expansion is toxic to the cell only when inserted in its flanking sequence, indicating a mechanism for the pathogenesis of SCA6 which involves the whole C-terminal tail containing a nuclear localization signal and several protein binding sites. Despite the substantial evidence that the C-terminal fragment is conveyed to the nucleus, its potential role in this compartment was unknown. Interestingly, it has been reported that the C-terminus of the α1C subunit (Cav1.2, L-type calcium channel) is cleaved and is also present in cell nuclei where it acts as a transcription factor regulating a wide variety of endogenous genes (Gomez-Ospina et al., 2006). Recently Du et al. (2013) shed light on the origin and the function of this critical protein region. They demonstrated that a second cistron in the CACNA1A gene encodes a transcription factor, corresponding to the C-terminus, which coordinates the expression of neuronal genes involved in Purkinje cells development. They found a cryptic internal ribosomal entry site (IRES) located in a highly conserved sequence of 534 bp upstream the ATG 1960 (nucleotide 6,114 GenBank accession number NM_001127222) in CACNA1A mRNA, mediating the expression of the α1A C-Terminal (α1ACT) fragment. They further investigated the role of the wildtype and mutated α1ACT fragment in regulating gene expression. Through chromatin immunoprecipitation-based cloning experiments TAF1, BTG1, PMCA2 and GRN have been identified as target genes. These genes are abundantly expressed in Purkinje cell, although not uniquely, and they are possibly involved in the neurite outgrowth program. The wild type C-terminus increases the expression of at least these four genes, while the SCA6 mutated C-terminus abolishes this function and impairs the expression of the target genes in Purkinje cells, causing increased cell death and neurodegeneration. These results have been also obtained in vivo, in mice overexpressing α1ACTSCA6. These mice have reduced expression of TAF1, GRN, BTG1, PMCA2 genes and show ataxia and cerebellar cortical atrophy. On the contrary, overexpression of α1ACTWT in α1A−/− mice partially rescues their ataxic symptoms improving the phenotype at behavioral, histological and electrophysiological levels. Consistent with these findings, the TAF, BTG1, PMCA2 and GRN genes expression has increased from 1.5- to 3-fold.

Conclusions

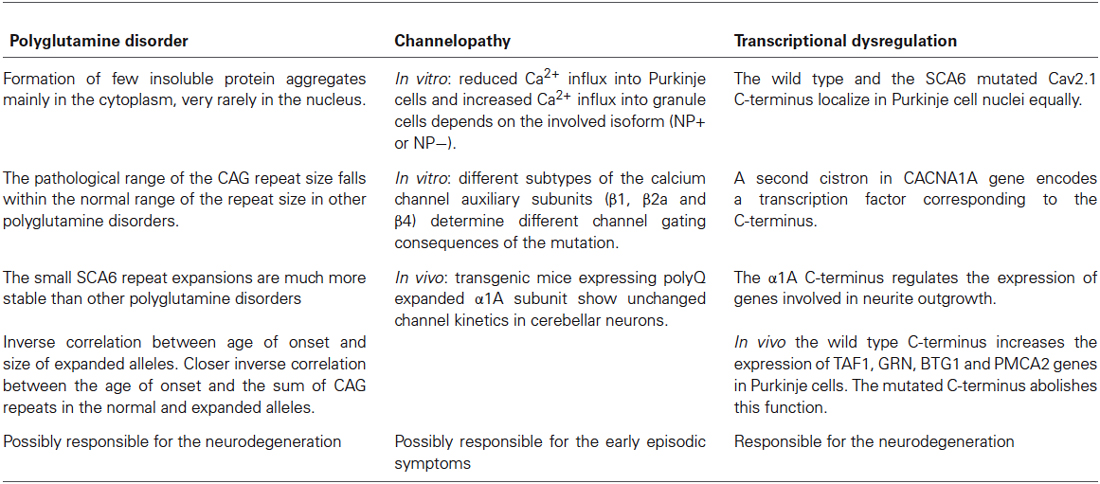

Currently, no therapy is known for SCA6, except for the use of Acetazolamide, a brain carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, that has been successfully used for EA2 but is possibly effective only in the episodic phase of SCA6 (Jen et al., 1998); however, Yabe et al. (2001) suggested that this drug can also temporarily reduce the severity of symptoms during the progression of the disease. Other therapies are in the experimental phase or their use is still controversial (Perlman, 2012) such as the NMDA antagonist (Ogawa et al., 2003; Ogawa, 2004) and branched-chain amino acids (BCAA), which improve neurotransmission among cerebellar neurons by stimulating intracellular glutamate metabolism (Mori et al., 2002). The latter treatment, used for other polyglutamine disorders, is likely to act on the effects of CAG repeat toxicity, in a later phase of the disease. In rare cases with Parkinsonism associated with SCA6, L-dopa has also been used (Khan et al., 2005). These different therapeutical approaches reflect the complex pathogenic mechanism of SCA6, which exhibits features of polyglutamine disease, channelopathy and dysregulation of transcription. The three proposed mechanisms seem to act according to divergent pathogenic pathways, but in some aspects they overlap and probably result in different symptoms occurring in different stages of the disease (see Table 1). The disease progression presumably occurs as the result of the synergy of the three mechanisms which lead to the selective Purkinje cells’ death and neurodegeneration.

It is now clear that the Cav2.1 C-terminal tail has a relevant role in the multifaceted protein activity and that the SCA6 mutation alters most of the protein functions. It is to note that, besides the SCA6 polyglutamine expansion, the α1ACT harbors only mutations associated to EA2 and lacks FHM1 mutations. The properties of the wild type Cav2.1 C-terminal tail are similar to those shown by the analogous protein fragment of Cav1.2 of the L-type voltage-gated calcium channel, which also encodes a transcription factor (Gomez-Ospina et al., 2006). Cav2.1 C-terminus has a potential self-regulatory role, due to the presence of binding sites for proteins modulating channel activity, such as calmodulin, which interacts with most calcium channels (Dunlap, 2007). In contrast, EA2 mutations probably alter channel function, impairing the binding with other channel subunits or auxiliary proteins such as G proteins, SNARE proteins and CaMKII (Catterall, 2010).

Beyond binding sites for proteins regulating channel function, the C-terminus harbors AT-hook domains, corresponding to exon 44, which is present or spliced in different isoforms (Soong et al., 2002). This domain is a tripartite DNA binding motif that is specific for AT-rich sequences typically found in nuclear proteins belonging to the HMG (High Mobility Group), and DNA binding proteins (Aravind and Landsman, 1998). Moreover, the α1ACT harbors several binding sites for proteins regulating cleavage and translocation to the nucleus, where the cleaved fragment, or the α1ACT generated by IRES, exerts its transcriptional activity on genes involved in the neuronal phenotype, in neurogenesis or neurodegeneration. The α1ACTSCA6 abolishes the normal function of the wild type α1ACT, leading to a transcriptional dysregulation, as most of the other polyglutamine disorders (Ross, 2002). More studies are needed to fully understand the mechanisms underlying SCA6, which could possibly reveal pathways involved also in other neurodegenerative disorders and suggest therapeutical targets.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Liana Veneziano was supported by Progetto Bandiera NANOMAX “Nanotechnology-based Diagnostics in Neurological Diseases and Experimental Oncology”, grant from the National Research Council of Italy. Paola Giunti received research support from the European Community Grant FP7- HEALTH-F2-2010-242193 (EFACTS) and she is also supported by the National Institute for Health Research University College London Hospitals Biomedical Research Centre.

References

Aravind, L., and Landsman, D. (1998). AT-hook motifs identified in a wide variety of DNA-binding proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 26, 4413–4421. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.19.4413

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bourinet, E., Soong, T. W., Sutton, K., Slaymaker, S., Mathews, E., Monteil, A., et al. (1999). Splicing of alpha 1A subunit gene generates phenotypic variants of P- and Q-type calcium channels. Nat. Neurosci. 2, 407–415. doi: 10.1038/8070

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Brenman, L. M. (2013). Spinocerebellar Ataxia type 6 (SCA6) phenotype in a patient with an intermediate mutation range CACNA1A allele. J. Neurol. Neurophysiol. 4:144. doi: 10.4172/2155-9562.1000144

Catterall, W. A. (2000). Structure and regulation of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 16, 521–555. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.16.1.521

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Catterall, W. A. (2010). Signaling complexes of voltage-gated sodium and calcium channels. Neurosci. Lett. 486, 107–116. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.08.085

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Chen, H., and Piedras-Rentería, E. S. (2007). Altered frequency-dependent inactivation and steady-state inactivation of polyglutamine-expanded alpha1A in SCA6. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 292, C1078–C1086. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00353.2006

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Du, X., Wang, J., Zhu, H., Rinaldo, L., Lamar, K. M., Palmenberg, A. C., et al. (2013). Second cistron in CACNA1A gene encodes a transcription factor mediating cerebellar development and SCA6. Cell 154, 118–133. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.059

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Dunlap, K. (2007). Calcium channels are models of self-control. J. Gen. Physiol. 129, 379–383. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200709786

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Frontali, M., Novelletto, A., Annesi, G., and Jodice, C. (1999). CAG repeat instability, cryptic sequence variation and pathogeneticity: evidence from different loci. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 354, 1089–1094. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1999.0464

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Gomez-Ospina, N., Tsuruta, F., Barreto-Chang, O., Hu, L., and Dolmetsch, R. (2006). The C terminus of the L-type voltage-gated calcium channel Ca(V)1.2 encodes a transcription factor. Cell 127, 591–606. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.017

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Guida, S., Trettel, F., Pagnutti, S., Mantuano, E., Tottene, A., Veneziano, L., et al. (2001). Complete loss of P/Q calcium channel activity caused by a CACNA1A missense mutation carried by patients with episodic ataxia type 2. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 68, 759–764. doi: 10.1086/318804

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Huynh, D. P., Figueroa, K., Hoang, N., and Pulst, S. M. (2000). Nuclear localization or inclusion body formation of ataxin-2 are not necessary for SCA2 pathogenesis in mouse or human. Nat. Genet. 26, 44–50. doi: 10.1038/79162

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ishiguro, T., Ishikawa, K., Takahashi, M., Obayashi, M., Amino, T., Sato, N., et al. (2010). The carboxy-terminal fragment of alpha(1A) calcium channel preferentially aggregates in the cytoplasm of human spinocerebellar ataxia type 6 Purkinje cells. Acta Neuropathol. 119, 447–464. doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0630-0

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ishikawa, K., Tanaka, H., Saito, M., Ohkoshi, N., Fujita, T., Yoshizawa, K., et al. (1997). Japanese families with autosomal dominant pure cerebellar ataxia map to chromosome 19p13.1-p13.2 and are strongly associated with mild CAG expansions in the spinocerebellar ataxia type 6 gene in chromosome 19p13.1. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 61, 336–346. doi: 10.1086/514867

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Jen, J. C., Yue, Q., Karrim, J., Nelson, S. F., and Baloh, R. W. (1998). Spinocerebellar ataxia type 6 with positional vertigo and acetazolamide responsive episodic ataxia. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 65, 565–568. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.65.4.565

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Jodice, C., Mantuano, E., Veneziano, L., Trettel, F., Sabbadini, G., Calandriello, L., et al. (1997). Episodic ataxia type 2 (EA2) and spinocerebellar ataxia type 6 (SCA6) due to CAG repeat expansion in the CACNA1A gene on chromosome 19p. Hum. Mol. Genet. 6, 1973–1978. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.11.1973

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Khan, N. L., Giunti, P., Sweeney, M. G., Scherfler, C., Brien, M. O., Piccini, P., et al. (2005). Parkinsonism and nigrostriatal dysfunction are associated with spinocerebellar ataxia type 6 (SCA6). Mov. Disord. 20, 1115–1119. doi: 10.1002/mds.20564

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kordasiewicz, H. B., Thompson, R. M., Clark, H. B., and Gomez, C. M. (2006). C-termini of P/Q-type Ca2+ channel alpha1A subunits translocate to nuclei and promote polyglutamine-mediated toxicity. Hum. Mol. Genet. 15, 1587–1599. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl080

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Mariotti, C., Gellera, C., Grisoli, M., Mineri, R., Castucci, A., and Di Donato, S. (2001). Pathogenic effect of an intermediate-size SCA-6 allele (CAG)(19) in a homozygous patient. Neurology 57, 1502–1504. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.8.1502

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Maruyama, H., Izumi, Y., Morino, H., Oda, M., Toji, H., Nakamura, S., et al. (2002). Difference in disease- free survival curve and regional distribution according to subtype of spinocerebellar ataxia: a study of 1,286 Japanese patients. Am. J. Med. Genet. 114, 578–583. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.10514

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Matsuyama, Z., Wakamori, M., Mori, Y., Kawakami, H., Nakamura, S., and Imoto, K. (1999). Direct alteration of the P/Q-type Ca2+ channel property by polyglutamine expansion in spinocerebellar ataxia 6. J. Neurosci. 19:RC14.

Mori, M., Adachi, Y., Mori, N., Kurihara, S., Kashiwaya, Y., Kusumi, M., et al. (2002). Double-blind crossover study of branched-chain amino acid therapy in patients with spinocerebellar degeneration. J. Neurol. Sci. 195, 149–152. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(02)00009-6

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ogawa, M. (2004). Pharmacological treatments of cerebellar ataxia. Cerebellum 3, 107–111. doi: 10.1080/147342204100032331

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ogawa, M., Shigeto, H., Yamamoto, T., Oya, Y., Wada, K., Nishikawa, T., et al. (2003). D-cycloserine for the treatment of ataxia in spinocerebellar degeneration. J. Neurol. Sci. 210, 53–56. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(03)00009-1

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Paulson, H. L. (1999). Protein fate in neurodegenerative proteinopathies: polyglutamine diseases join the (mis)fold. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 64, 339–345. doi: 10.1086/302269

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Perlman, S. L. (2012). Treatment and management issues in ataxic diseases. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 103, 635–654. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-444-51892-7.00046-2

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Piedras-Rentería, E. S., Watase, K., Harata, N., Zhuchenko, O., Zoghbi, H. Y., Lee, C. C., et al. (2001). Increased expression of alpha 1A Ca2+ channel currents arising from expanded trinucleotide repeats in spinocerebellar ataxia type 6. J. Neurosci. 21, 9185–9193.

Restituito, S., Thompson, R. M., Eliet, J., Raike, R. S., Riedl, M., Charnet, P., et al. (2000). The polyglutamine expansion in spinocerebellar ataxia type 6 causes a beta subunit-specific enhanced activation of P/Q-type calcium channels in Xenopus oocytes. J. Neurosci. 20, 6394–6403.

Ross, C. A. (2002). Polyglutamine pathogenesis: emergence of unifying mechanisms for Huntington’s disease and related disorders. Neuron 35, 819–822. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(02)00872-3

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Saegusa, H., Wakamori, M., Matsuda, Y., Wang, J., Mori, Y., Zong, S., et al. (2007). Properties of human Cav2.1 channel with a spinocerebellar ataxia type 6 mutation expressed in Purkinje cells. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 34, 261–270. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2006.11.006

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Soong, T. W., DeMaria, C. D., Alvania, R. S., Zweifel, L. S., Liang, M. C., Mittman, S., et al. (2002). Systematic identification of splice variants in human P/Q-type channel alpha1(2.1) subunits: implications for current density and Ca2+-dependent inactivation. J. Neurosci. 22, 10142–10152.

Takahashi, H., Ishikawa, K., Tsutsumi, T., Fujigasaki, H., Kawata, A., Okiyama, R., et al. (2004). A clinical and genetic study in a large cohort of patients with spinocerebellar ataxia type 6. J. Hum. Genet. 49, 256–264. doi: 10.1007/s10038-004-0142-7

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Takahashi, M., Obayashi, M., Ishiguro, T., Sato, N., Niimi, Y., Ozaki, K., et al. (2013). Cytoplasmic location of α1A voltage-gated calcium channel C-terminal fragment (Cav2.1-CTF) aggregate is sufficient to cause cell death. PLoS One 8:e50121. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050121

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Toru, S., Murakoshi, T., Ishikawa, K., Saegusa, H., Fujigasaki, H., Uchihara, T., et al. (2000). Spinocerebellar ataxia type 6 mutation alters P-type calcium channel function. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 10893–10898. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.15.10893

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Tottene, A., Fellin, T., Pagnutti, S., Luvisetto, S., Striessnig, J., Fletcher, C., et al. (2002). Familial hemiplegic migraine mutations increase Ca(2+) influx through single human CaV2.1 channels and decrease maximal CaV2.1 current density in neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 99, 13284–13289. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192242399

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Watase, K., Barrett, C. F., Miyazaki, T., Ishiguro, T., Ishikawa, K., Hu, Y., et al. (2008). Spinocerebellar ataxia type 6 knockin mice develop a progressive neuronal dysfunction with age-dependent accumulation of mutant CaV2.1 channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 105, 11987–11992. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804350105

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Yabe, I., Sasaki, H., Matsuura, T., Takada, A., Wakisaka, A., Suzuki, Y., et al. (1998). SCA6 mutation analysis in a large cohort of the Japanese patients with late-onset pure cerebellar ataxia. J. Neurol. Sci. 156, 89–95. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(98)00009-4

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Yabe, I., Sasaki, H., Yamashita, I., Takei, A., and Tashiro, K. (2001). Clinical trial of acetazolamide in SCA6, with assessment using the Ataxia Rating Scale and body stabilometry. Acta Neurol. Scand. 104, 44–47. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0404.2001.00299.x

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Zhuchenko, O., Bailey, J., Bonnen, P., Ashizawa, T., Stockton, D. W., Amos, C., et al. (1997). Autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia (SCA6) associated with small polyglutamine expansions in the alpha 1A-voltage-dependent calcium channel. Nat. Genet. 15, 62–69. doi: 10.1038/ng0197-62

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Keywords: CACNA1A, P/Q type calcium channel, CaV2.1, Spinocerebellar Ataxia type 6, SCA6, polyglutamine disorder, channelopathy

Citation: Giunti P, Mantuano E, Frontali M and Veneziano L (2015) Molecular mechanism of Spinocerebellar Ataxia type 6: glutamine repeat disorder, channelopathy and transcriptional dysregulation. The multifaceted aspects of a single mutation. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 9:36. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2015.00036

Received: 01 December 2014; Paper pending published: 06 January 2015;

Accepted: 21 January 2015; Published online: 16 February 2015.

Edited by:

Mauro Pessia, Universtity of Perugia, ItalyReviewed by:

Robert Weissert, University of Regensburg, GermanyErika S. Piedras-Renteria, Loyola University Chicago, USA

Copyright © 2015 Giunti, Mantuano, Frontali and Veneziano. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution and reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Liana Veneziano, Laboratory of Neurogenetics, Institute of Translational Pharmacology, National Research Council of Italy, Via Fosso del Cavaliere, 100 00133 Rome, Italy e-mail: liana.veneziano@ift.cnr.it

† These authors have contributed equally to this work.

Paola Giunti

Paola Giunti Elide Mantuano

Elide Mantuano Marina Frontali

Marina Frontali Liana Veneziano

Liana Veneziano