95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Behav. Neurosci. , 12 April 2021

Sec. Emotion Regulation and Processing

Volume 15 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2021.632906

This article is part of the Research Topic How the Timing, Nature, and Duration of Relationally Positive Experiences Influence Outcomes in Children With Adverse Childhood Experiences View all 9 articles

Ziggi Ivan Santini1*

Ziggi Ivan Santini1* Veronica S. C. Pisinger1

Veronica S. C. Pisinger1 Line Nielsen1

Line Nielsen1 Katrine Rich Madsen1

Katrine Rich Madsen1 Malene Kubstrup Nelausen1

Malene Kubstrup Nelausen1 Ai Koyanagi2,3

Ai Koyanagi2,3 Vibeke Koushede4

Vibeke Koushede4 Sue Roffey5,6

Sue Roffey5,6 Lau C. Thygesen1

Lau C. Thygesen1 Charlotte Meilstrup4

Charlotte Meilstrup4Background: Previous research has suggested that social disconnectedness experienced at school is linked to mental health problems, however, more research is needed to investigate (1) whether the accumulation of various types of social disconnectedness is associated with risk for mental health problems, and (2) whether loneliness is a mechanism that explains these associations.

Methods: Using data from the Danish National Youth Study 2019 (UNG19), nation-wide cross-sectional data from 29,086 high school students in Denmark were analyzed to assess associations between social disconnectedness experienced at school (lack of classmate support, lack of teacher support, lack of class social cohesion, and not being part of the school community) and various mental health outcomes, as well as the mediating role of loneliness for each type of disconnectedness. Multilevel regression analyses were conducted to assess the associations.

Results: Descriptive analyses suggest that 27.5% of Danish high school students experience at least one type of social disconnectedness at school. Each type of social disconnectedness was positively associated with mental health problems (depression symptoms, anxiety symptoms, stress, sleep problems, suicidal ideation, non-suicidal self-injury, eating disorder, body dissatisfaction, and low self-esteem) and negatively associated with mental well-being. In all cases, loneliness significantly mediated the associations. We found a clear dose-response pattern, where each addition in types of social disconnectedness was associated with (1) stronger negative coefficients with mental well-being and (2) stronger positive coefficients with mental health problems.

Conclusion: Our results add to a large evidence-base suggesting that mental health problems among adolescents may be prevented by promoting social connectedness at school. More specifically, fostering social connectedness at school may prevent loneliness, which in turn may promote mental well-being and prevent mental health problems during the developmental stages of adolescence. It is important to note that focusing on single indicators of school social connectedness/disconnectedness would appear to be insufficient. Implications for practices within school settings to enhance social connectedness are discussed.

Mental health problems have been estimated to affect 10–20% of children and adolescents worldwide and account for a large portion of the global burden of disease (Kieling et al., 2011; Polanczyk et al., 2015). Mental health among adolescents is particularly pertinent to prioritize and address as it affects short and long-term health, learning abilities, and lays the foundation for mental health status in adulthood (Harrington and Clark, 1998; Fergusson and Woodward, 2002; Green et al., 2004; Kessler et al., 2005; Hawton et al., 2006; Hawton and Harriss, 2007). Mental health problems compromise quality of life and healthy functioning, and may also lead to suicidal behavior and completed suicides. Suicide is a leading cause of death in adolescents, and therefore a major public health issue (Kokkevi et al., 2012; Kõlves and De Leo, 2016). Intentional self-injury behaviors are highly prevalent among adolescents in Europe, with 27.6% of adolescents having engaged in self-injury behaviors at some point during their lifetime (Brunner et al., 2014). Thus, it is imperative to identify protective factors for mental health among adolescents, particularly in settings where adolescents spend much of their time outside of home—the school setting.

School social connectedness has had an increasingly high profile since the 2003 Wingspread Conference in the USA, which resulted in a National Strategy for Improving School Connectedness1, and there is now compelling evidence demonstrating that a sense of school connectedness can reduce feelings of loneliness and protect mental health (Cavanaugh and Buehler, 2015; Benner et al., 2017). Originally, school connectedness was defined as a student's belief that teachers cared about them and their learning. Goodenow (1993) took this a step further to define school connectedness (or belonging) as “the extent to which students feel personally accepted, respected, included and supported by others in the environment” (p.80). In studies involving adolescent students, several factors pertaining to social connectedness within the school setting are relevant to take into account. For example, peer support involves whether students feel that they can receive help and support from their classmates or other students within the school, and teacher support pertains to whether students feel that they can receive help and support from their teachers (McLaughlin and Clarke, 2010; Kidger et al., 2012). Factors such as class social cohesion (the extent to which students perceive a closeness across all students in their class) (Loukas and Robinson, 2004; van den Bos et al., 2018), and integration into the school community (the extent to which students participate in and feel part of the broader school community, e.g., through extracurricular activities) (Osterman, 2000; Patton et al., 2000) are also relevant to consider when assessing school social connectedness.

The importance of social connectedness and, conversely, social disconnectedness in the etiology of affective and mental health problems among high school students have been documented in numerous scientific reports (Waters et al., 2009). Prior systematic reviews have linked school relational factors (e.g., supportive peer and teacher relationships) or closeness to others and to the school as a whole (e.g., cohesion, aspects of participation, and feelings of membership of the school community) with better mental health (Waters et al., 2009; McLaughlin and Clarke, 2010; Kidger et al., 2012). Addressing social disconnectedness specifically in adolescence and early adulthood is vital from a developmental perspective. This is because adolescents' interactions with others may influence their social cognitions later on (i.e., cognitive processes that determine their actions and reactions to social situations and people around them) (Goossens, 2018), and because people in general tend to establish their closest relationships relatively early in life (social networks are generally formed in adolescence or early adulthood and tend to become smaller as people age) (English and Carstensen, 2014). The importance of social connections for mental health later in life was highlighted by a 32-year longitudinal study reporting that adolescent social connectedness was a far stronger predictor of adult well-being than academic achievement (Olsson et al., 2013). While various aspects of school social disconnectedness have been separately linked to mental health among adolescents, prior work has not investigated the contributions of multiple aspects of school social disconnectedness and their accumulating impact in terms mental health and well-being outcomes.

Furthermore, although measures of social disconnectedness have been clearly linked to mental health outcomes among adolescents, the role of perceived social isolation (i.e., loneliness) in the association between measures of social disconnectedness and mental health outcomes has only been investigated in relatively few studies. Loneliness pertains to the subjective experience of a shortfall in one's social network and resources, or in other words, a perceived discrepancy between desired and actual social relationships (de Jong Gierveld and Havens, 2004). According to theories of human social behavior and function (Goossens, 2018), humans have a strong need and desire to be connected to other people, and when this need is thwarted, they feel lonely. Loneliness signals that important social bonds are lacking or under threat, prompting people to repair social bonds or establish new relationships. Whereas, some individuals manage to reconnect with others and thereby resolve the situation, prolonged or chronic loneliness happens when individuals do not manage to establish or re-establish social ties. This can result in a number of adverse cognitive and physiological processes that are harmful to health and well-being, such as hypervigilance for social threats, maladaptive social cognition, increased self-focus or self-centeredness, greater activity of the stress system, and further social withdrawal (Masi et al., 2011; Cacioppo et al., 2017; Goossens, 2018; Eccles and Qualter, 2020).

Importantly, it has been argued that although mental health may be directly influenced by social disconnectedness (e.g., lack of support), pathways operating indirectly through loneliness may be equally or more important than for example actual support or cohesion (Berkman et al., 2000; Uchino et al., 2012). Adolescence is considered a time period where loneliness is particularly pertinent, with theories suggesting that the adolescent experience of loneliness may be different from that of children or adults, given the developmental changes in identity, autonomy, and individuation, as well as social orientation and reorientation (Heinrich and Gullone, 2006; Laursen and Hartl, 2013; Goossens, 2018). Prolonged or chronic loneliness may put adolescents at heightened risk of developing mental health problems due to its interference with social, cognitive, and physiological developmental processes. However, it is possible that a loneliness trajectory could be prevented by addressing social disconnectedness, which in turn could prevent the onset or amplification of mental health problems. Some cross-sectional (Kong and You, 2013) and longitudinal studies (Fiori and Consedine, 2013; Jose and Lim, 2014) on adolescents have shown that loneliness mediates associations between some types of social connectedness and some mental health and well-being outcomes. Specifically, these studies assessed the mediating role of loneliness in associations between social support (various types) and life satisfaction (Kong and You, 2013), social support (various types) and depressive symptoms/life satisfaction/well-being (Fiori and Consedine, 2013), and social connectedness (various types) and depressive symptoms (Jose and Lim, 2014). However, these studies did not focus on types of social connectedness that pertain specifically to the school context, but broader types of connectedness both within and outside the school setting.

While previous research has investigated associations between single types of school social disconnectedness and mental health measures, little is known about (a) the mediating role of loneliness in associations between specifically school social disconnectedness and mental health, and (b) the cumulative effect of multiple types of social disconnectedness experienced at school on a wide range of mental health outcomes. Therefore, the central aim of this study was to assess whether the accumulation of various types of social disconnectedness (i.e. lack of teacher and peer support, lack of class cohesion, not being part of the school community) is associated with risk for mental health problems, and whether loneliness is a mechanism that explains these associations. To achieve this aim, we conducted a cross-sectional study using data from a nation-wide survey of high school students in Denmark. Denmark is a relevant setting to assess this association as it has seen considerable increases in mental health problems (including suicidal behavior) among adolescents throughout the past 10 years (Due et al., 2014; Jensen et al., 2018; Jeppesen et al., 2020). Based on the literature reviewed, we hypothesized that (1) each type of school social disconnectedness would be independently associated with each mental health outcome, (2) loneliness would mediate these associations, and (3) the accumulation of types of school social disconnectedness would be associated with incremental increases in risk for mental health problems.

Data stem from the Danish National Youth Study 2019 (UNG19), a national survey of high school students. A description of the study design and population is provided elsewhere (Pisinger et al., 2019, 2021). All schools in Denmark (n = 287) offering general high school (STX), preparatory high school (HF), commercial high school (HHX), or technical high school (HTX) examination were invited to participate. All schools received the invitation by mail, and those who did not respond within a week received a reminder mail and then a phone call from the research group. All classes within schools were invited to participate. In total, 88 schools agreed to participate (school response proportion 31%). At school level, 50 (33%) STX schools, 32 (28%) HF schools, 15 (28%) HHF schools, and 19 (35%) HTX schools participated. Of the 43,961 students that were enrolled in the 88 schools, 29,086 students agreed to participate in the survey (student response proportion 66% among invited schools). The student response proportion across all high schools in Denmark was 20%. Data collection took place from 14 January 2019 to 1 April 2019. Additionally, the survey was linked to the Danish Civil Registration System (Pedersen, 2011) and registers at Statistics Denmark to obtain information pertaining to parents' education, employment status, household income, etc. Each citizen in Denmark has a personal registration number, enabling linkage between different registers (Thygesen et al., 2011). All data are pseudonymized, so they cannot be traced back to specific participants.

Mental well-being: The Short Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (SWEMWBS) is a validated measure used to monitor mental well-being in the general population and is based on a conceptualization of mental well-being as feeling good and functioning well. The scale has recently been validated in Denmark (Koushede et al., 2019). SWEMWBS consists of seven positively worded questions pertaining to mental well-being experienced within the past 14 days: (1) I've been feeling optimistic about the future, (2) I've been feeling useful, (3) I've been feeling relaxed, (4) I've been dealing with problems well, (5) I've been thinking clearly, (6) I've been feeling close to other people, (7) I've been able to make up my own mind about things. Response options were: none of the time 1; rarely 2; some of the time 3; often 4; all of the time 5. Because item 6 was too closely associated with loneliness from a conceptual standpoint, we omitted this item. Summing up the scale with item 6 omitted leads to a score between 6 and 30; the higher the score, the higher mental well-being.

Depression symptoms: Depression experienced within the past 14 days was measured using the PHQ-2 scale (Kroenke et al., 2009, 2010). The PHQ-2 is a validated screening tool (Kroenke et al., 2009, 2010), that covers two symptoms central to depression: (1) little interest or pleasure in doing things, and (2) feeling down, depressed, or hopeless. Response options were: not at all 0; several days 1; more than half the days 2; nearly every day 3. The summed up scale ranges from 0 to 6.

Anxiety symptoms (symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder): Anxiety experienced within the past 14 days was measured using the GAD-2 scale (Kroenke et al., 2009, 2010). The GAD-2 is a validated screening tool (Kroenke et al., 2009, 2010), that covers two symptoms central to generalized anxiety disorder: (1) feeling nervous, anxious, or on edge, and (2) not being able to stop or control worrying. Response options were: not at all 0; several days 1; more than half the days 2; nearly every day 3. The summed up scale ranges from 0 to 6.

Stress was assessed using the single-item: “How often are you stressed?” Response options were: never/almost never; monthly; weekly; daily.

Sleep problems was assessed using the single-item: “Within the last 6 months, how often have you experienced sleep problems?” Response options were: seldom or never; almost every month; almost every week; more than once per week; almost every day.

Suicidal ideation was assessed using the single-item: “Did you ever had thoughts of taking your own life?” Suicidal ideation was coded as present if the respondent answered yes, and absent if the respondent answered no.

Non-suicidal self-injury (within the past year) was assessed first by using the single-item: “Have you ever purposefully inflicted harm to yourself (e.g., cut, burned, teared, punched yourself)?” If the respondent answered in the affirmative, the respondent was asked “Within the past year, how often have you purposefully inflicted harm to yourself?” with response options being: I have not inflicted harm to myself within the last year; monthly or less often; weekly; daily or almost daily. Non-suicidal self-injury (within the past year) was coded as present if the respondent answered affirmative to the first item AND anything other than “I have not inflicted harm to myself within the past year” to the second item, and absent if the respondent answered no to the first item OR yes to the first, but affirmative to “I have not inflicted harm to myself within the past year.”

Eating disorder was assessed using the single-item: “Do you have an eating disorder?” An eating disorder was coded as present if the respondent answered yes, and absent if the respondent answered no.

Body dissatisfaction was assessed using the single-item: “On a scale from 1 to 10, how satisfied are you with your body?” Responded options ranged from 1 (very dissatisfied) to 10 (very satisfied). The variable was reversed, so higher values indicated higher levels of body dissatisfaction.

Self-esteem was assessed using the single-item: “To which extent do you agree with the following statement: I am good enough the way I am.” Response options were: completely agree; agree; neither agree nor disagree; disagree; completely disagree.

Four items were used for social disconnectedness experienced at school. These were: support from classmates; support from teachers; class social cohesion; and being part of the school community. Support from classmates was assessed with the item “Can you get help and support from your classmates when you need it?” Response categories were: never; almost never; once in a while; often; very often. Lack of classmate support was categorized into: 1 never/almost never; and 0 for the remaining three categories. Support from teachers was assessed with the item “Can you get help and support from your teachers when you need it?” Response categories were: never; almost never; once in a while; often; very often. Lack of teacher support was categorized into: 1 never/almost never; and 0 for the remaining three categories. Class social cohesion was assessed with the item “Would you say that your class is characterized by a strong social cohesion?” Response categories were: no, quite the opposite; no; yes, to some extent; yes, to a very large extent. Lack of class social cohesion was categorized into: 1 no, quite the opposite/no; and 0 for the remaining two categories. Being part of the school community was assessed using the item “Are you part of the social community at your school?” Response categories were: rarely or never; once in a while; yes, most of the time; yes, always. Not being part of the school community was categorized into: 1 rarely or never; and 0 for the remaining three categories. The rationale for the recoding of the variables was to create binary variables that reflected clear negative response (i.e., no or never to a complete or almost complete extent). The four items were dichotomized in order to enable the generation of a scale that indicates cumulative “Social disconnectedness at school,” with the categories 0–4. A zero reflects not being socially disconnected at school (i.e., not qualifying as disconnected according to criteria), one reflects lacking connectedness in one aspect, two lacking in two aspects, three lacking in three aspects, and four lacking in all four aspects. Cronbach's alpha for the four items was 0.7 indicating acceptable internal consistency.

Loneliness was assessed using the single-item: “Do you feel lonely?” Response categories were: no; yes, sometimes; yes, often; yes, very often.

Demographic characteristics included gender (male, female), age (continuous), and migration background (Danish citizen, immigrant, descendent). Type of school included the four types of high school education: STX; HF; HHF; HTX. Household income was divided into quartiles. Parents' highest achieved education was assessed by using the highest education achieved among the parents. The variable included six categories: primary school; high school; vocational training; higher education 1–2 years; higher education 3–4 years; higher education >4 years. Parents' employment status included three categories: both parents employed; both parents unemployed; one parent unemployed and one parent employed. “Missing” categories were created for parents' highest achieved education and parents' employment status in order to minimize loss of information due to missing data.

The statistical analysis was done with Stata version 13.1 (Stata Corp LP, College Station, Texas). A descriptive analysis was conducted to demonstrate the characteristics of the sample. These analyses included frequencies, proportions, means, and standard deviations (SD).

In all analyses, the following outcomes and models were used: Mental well-being (continuous), depression symptoms (continuous), anxiety symptoms (continuous), stress (ordinal), sleep problems (ordinal), suicidal ideation (binary), non-suicidal self-injury (binary), eating disorder (binary), body dissatisfaction (continuous), self-esteem (ordinal).

First, to assess the role of loneliness in the association between each type of social disconnectedness and all outcomes, a mediation analysis was performed using the khb (Karlson Holm Breen) command in Stata (Kohler et al., 2011; Breen et al., 2013). It decomposes the total effect of a variable into direct and indirect (i.e., mediational) effects. In other words, the total effect is the association between the predictor and outcome (not adjusted for the mediator), the direct effect is the association between the predictor and outcome (adjusted for the mediator), and the indirect effect is the difference between the two (i.e., total effect minus direct effect). This method also allows for the calculation of the mediated percentage, which is interpreted as the percentage of the total effect that can be explained by the mediator (indirect effect/total effect). Each type of social disconnectedness was entered separately in all models predicting mental health outcomes, with loneliness as the mediator.

Next, to assess the association between accumulating types of social disconnectedness and mental health outcomes, linear, oprobit, and logit models were used, with the constructed variable for accumulating types of social disconnectedness used as the predictor variable. All statistical models were based on the sample with no missing data (except where specific “missing” categories were created). Information regarding the proportion of missing data can be found in Supplementary Material. The hierarchical structure of the data (clustering within schools and departments within schools) was taken into account using the mixed (linear multilevel regression), meoprobit (ordinal multilevel regression), or melogit (logit multilevel regression) function in Stata. Results are expressed as coefficients (Coef) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the study sample. The average age of the sample was 17.8 (SD = 1.3) years, and 55.4% were females. 7.3% of the participants reported lack of support from classmates, 12.6% reported lack of support from teachers, 15.2% reported lack of class social cohesion, and 4.7% reported not being part of the school community. 72.5% of the participants did not experience any type of social disconnectedness at school, while 18.8% experienced one type of disconnectedness, 6.0% experienced two types of disconnectedness, 2.2% experienced three types of disconnectedness, and 0.6% experienced all four types of disconnectedness.

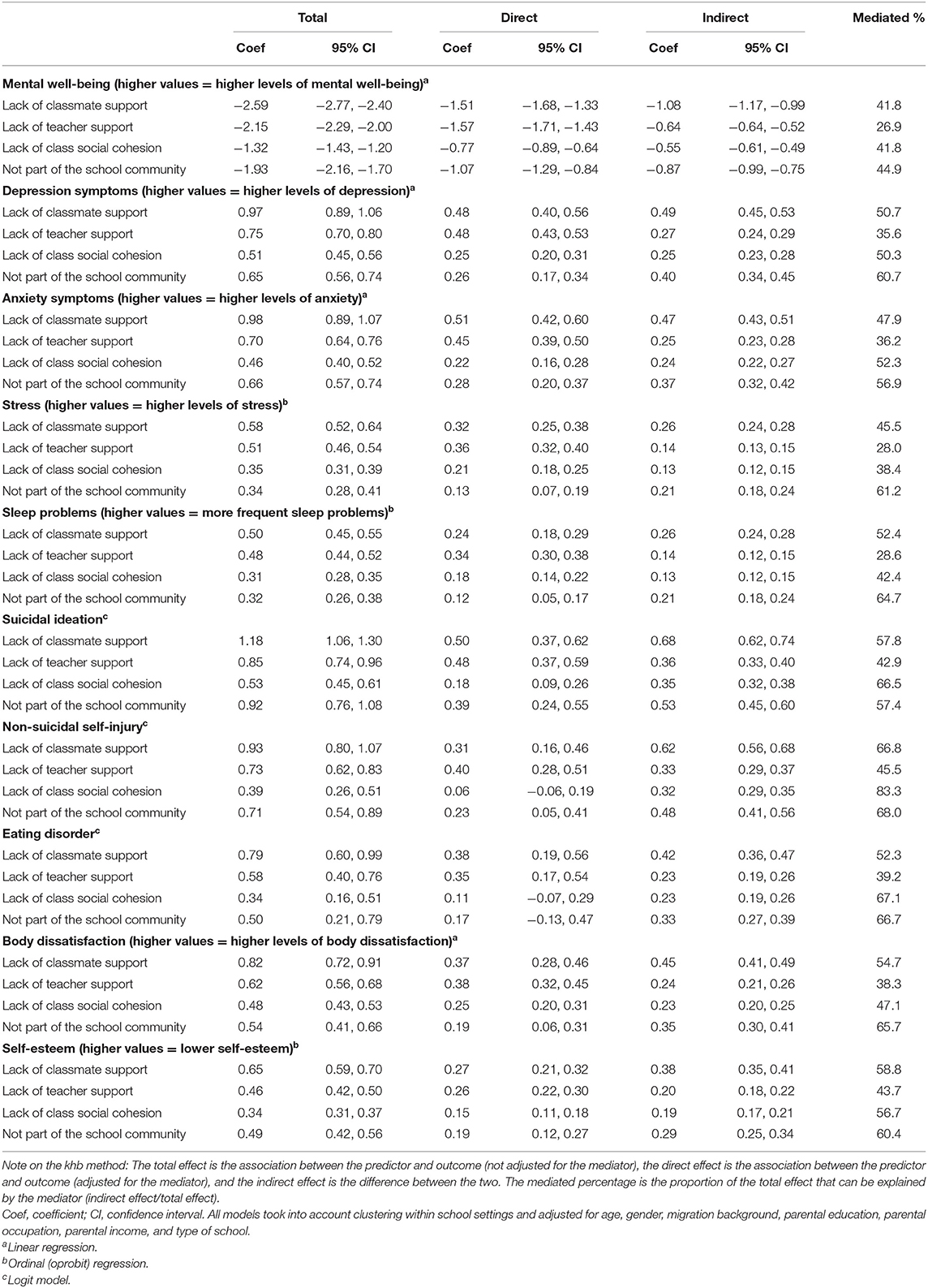

Table 2 shows the associations between individual types of social disconnectedness at school and mental health outcomes, namely mental well-being, depression symptoms, anxiety symptoms, stress, sleep problems, suicidal ideation, non-suicidal self-injury, eating disorder, body dissatisfaction, self-esteem. All types were significantly associated with all outcomes, where each type of social disconnectedness was positively associated with mental health problems and negatively associated with mental well-being. In general, lack of classmate support appeared to be the strongest factor associated with all outcomes, followed by lack of teacher support or not being part of the school community. The type that had the least strong associations to all outcomes was lack of class social cohesion. Loneliness mediated all associations, ranging from 41.8–66.8% for lack of classmate support, 26.9–43.7% for lack of teacher support, 38.4–83.3% for lack of class social cohesion, and 44.9–68.0% for not being part of the school community.

Table 2. Regression analyses predicting mental health outcomes by types of social disconnectedness in school (each type in separate models) with loneliness as the mediating variable (khb method).

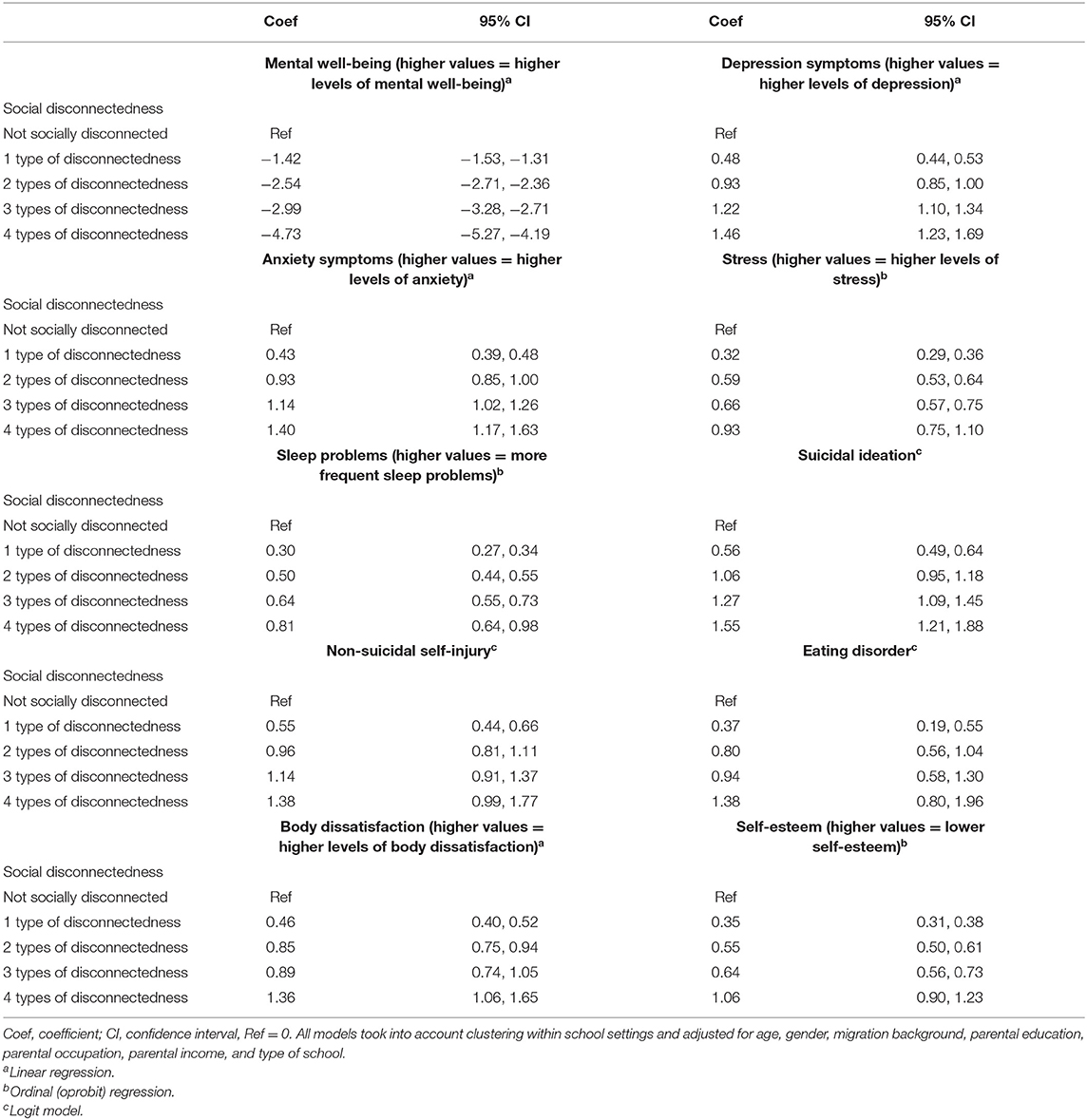

Table 3 shows the associations between the generated social disconnectedness scale and mental health outcomes. Across all outcomes, a dose-response pattern can be observed between the predictor and all outcomes, i.e., incrementally higher positive coefficients for mental health problems (depression, anxiety, stress, sleep problems, suicidal ideation, non-suicidal self-injury, eating disorder, body dissatisfaction, low self-esteem) for each increase in types of social disconnectedness at school, and incrementally higher negative coefficients for mental well-being for each increase in types of social disconnectedness at school.

Table 3. Regression analyses predicting mental health outcomes by social disconnectedness in school (categorical scale).

We conducted several sensitivity analyses. First, we assessed the extent to which each type of social disconnectedness added to the models. Each type of social type of social disconnectedness added uniquely to each model (see Supplementary Table A1), with two exceptions (non-suicidal self-injury and eating disorder) where lack of class social cohesion was positively associated with the outcomes but did not reach statistical significance. Next, in estimating associations between accumulating types of social disconnectedness, we conducted the same models as reported above, but where we included symptoms of pain and discomfort and long-term illness and disability (these covariates are described in Supplementary Material) to the list of covariates as potential confounders (since these factors could potentially be related to social withdrawal as well as mental health). The results remained virtually the same (see Supplementary Table A2), there were no major differences in terms of statistical significance, only the coefficients were generally slightly attenuated. However, the basic pattern of coefficients was the same. Finally, we conducted a dose-response analysis where the same models were conducted (as described for the models shown in Table 3), but where the constructed variable for accumulating types of social disconnectedness were entered in the models as a continuous rather than a categorical variable. In this case, social disconnectedness was a significant predictor or all outcomes (see Supplementary Table A3).

Our results showed that adolescents who experience any type of social disconnectedness at school (lack of classmate or teacher support, lack of class social cohesion, not being part of the school community) were at heightened risk for mental health problems. Lack of support from classmates appeared to be most strongly related to most of the outcomes, followed by lack of support from teachers or not being part of the school community. Lack of class social cohesion was the least strong predictor. As part of these analyses, we showed that the associations could, to a large extent, be accounted for by increases in loneliness. These findings confirmed our first two hypotheses. Our study further revealed that increases in types of social disconnectedness was negatively associated with mental well-being, and positively associated with depression symptoms, anxiety symptoms, stress, sleep problems, suicidal ideation, non-suicidal self-injury, eating disorders, body dissatisfaction, and low self-esteem. The coefficients indicate a clear and robust dose-response pattern [lending support to the hypothesized direction of associations (Flanders et al., 1992)], where each addition in social disconnectedness was associated with incrementally stronger coefficients.

Major strengths of the study include the use of validated scales for measuring mental well-being, depression, and anxiety, and the use of a large nation-wide school-based survey linked with national registers, which made it possible to make direct links to a number of useful register-based covariates. However, some limitations are worth mentioning. First, the cross-sectional design precludes us from making causal inferences. An issue related to this limitation is that the suicidal ideation item enquired about having experienced this problem anytime during the respondent's lifetime (in the case of non-suicidal self-injury, we were able to capture those for whom it had occurred within the past year), and it is possible that some respondents experienced this in the past but not at the time they completed the questionnaire. Although we cannot make inferences regarding directions of causality, it may be noted that Shochet, Dadds (Shochet et al., 2006) reported that school social disconnectedness at baseline predicted mental health problems (depression, anxiety) 1 year later, but the reverse was not true, i.e., mental health problems at baseline did not predict school social disconnectedness 1 year later. Similarly, Lasgaard, Goossens (Lasgaard et al., 2011) reported that loneliness in adolescence predicted depression over time, but not vice versa. Others have reported reciprocal relationships, but with the direction from loneliness to depression being stronger than the reverse order (Vanhalst et al., 2012). This lends support to directionality implied in our theoretical model. Second, these findings were based on self-reported data, which implies the possibility for self-report bias. Also, we cannot exclude the possibility of issues pertaining to common-methods variance. Future longitudinal data and the use of for example diagnosed mental health outcomes or relevant biological measurements are warranted to reduce these limitations.

Third, it may be taken into account that many of the outcomes (apart from those pertaining to mental well-being, depression and anxiety symptoms) were measured based on single item measures rather than validated scales, which may or may not be a limitation given that single-item measures also have some advantages (e.g., ease of interpretation, avoiding respondent fatigue) (Bowling, 2005). Data based on diagnostic interviews or longer versions of the various scales could potentially produce different results. Fourth, the school participation proportion was low. This was expected since schools in Denmark are often overwhelmed by survey requests. Hence, many schools only participate in surveys that are mandatory. Due to the relatively low response rate, we cannot rule out the possibility that some schools characterized by more mental health problems and social disconnectedness among their students were not among those participating, and the same may be argued regarding the individual students not participating. This may lead to an underestimate in our findings. A non-response analysis indicates that to be female, younger, have a Danish ethnic background, and have parents with higher income is associated with response to the survey (Pisinger et al., 2021).

Previous studies on adolescents have reported links between different aspects of school social disconnectedness and well-being (Chu et al., 2010; Jose et al., 2012), depression (Kiesner et al., 2003; Murberg and Bru, 2004; Undheim and Sund, 2005; Shochet et al., 2006, 2008; Bond et al., 2007; LaRusso et al., 2007; Way et al., 2007; Costello et al., 2008; Lin et al., 2008; McGraw et al., 2008; Rueger et al., 2010; Wilkinson-Lee et al., 2011; Foster et al., 2017), anxiety (Murberg and Bru, 2004; Shochet et al., 2006; Bond et al., 2007; McGraw et al., 2008; Rueger et al., 2010; Foster et al., 2017), stress (McGraw et al., 2008), sleep problems (Maume, 2013; Bao et al., 2018), suicidal ideation (Sun and Hui, 2007; Winfree and Jiang, 2009; Foster et al., 2017), non-suicidal self-injury (Klemera et al., 2017), and self-esteem (Williams and Galliher, 2006; Rueger et al., 2010; Foster et al., 2017), but we did not find similar studies documenting links between school social disconnectedness and eating disorders or body dissatisfaction. Our study adds to the evidence base suggesting that feeling disconnected in one's school environment may have implications for a wide range of mental health problems. Although lack of class social cohesion was a significant predictor of all outcomes, the strongest predictor appeared to be lack of support from classmates, followed by lack of support from teachers and not being part of the school community. This suggests that direct interpersonal relationships with classmates and students are of prime importance, as well as feeling part of the entire school community. Enhancing interpersonal relationships between among students and with teachers may also improve class social cohesion.

In line with previous research (Fiori and Consedine, 2013; Kong and You, 2013; Jose and Lim, 2014), our mediation analyses confirmed that substantial proportions of the associations between all types of social disconnectedness and all outcomes were mediated by loneliness. Other possible mediators may include for example neurobiological and psychological resilience factors (Ozbay et al., 2007), or academic achievement (Song et al., 2015). If our results are confirmed with longitudinal data, as it was in previous studies (Fiori and Consedine, 2013; Jose and Lim, 2014), the implications would be that social disconnectedness indirectly leads to mental health problems by increasing feelings of loneliness. Loneliness is an issue of concern in and of itself, and while meta-analytic reviews have evaluated specific interventions to reduce loneliness among adolescents (Masi et al., 2011; Eccles and Qualter, 2020), our results imply that fostering social connectedness at school could prevent loneliness, which in turn would promote mental well-being and prevent mental health problems.

The novelty of the current study pertains particularly to the observed increases in risk for mental health problems associated with multiple forms of social disconnectedness. Every additional type of disconnectedness experienced at school was associated with incrementally higher risk for mental health problems. It would appear that addressing or preventing single types of social disconnectedness is not a sufficient strategy for protecting mental health, since, either one - out of four types of disconnectedness–was associated with increased risk of unfavorable outcomes. The issue of social disconnectedness experienced at school in Denmark is disconcerting, given that 27.5% of high school students according to our sample experience some form of feeling disconnected within their school environment. For individuals who report being socially disconnected, the various different mental health problems may interact, accumulate, or reinforce each other over time, which is likely to negatively affect developmental processes, health, functioning, learning outcomes, increase school drop-out, compromise healthy trajectories into adulthood, and potentially result in psychiatric disorders, suicide or other problems both in the short and long term (Harrington and Clark, 1998; Fergusson and Woodward, 2002; Green et al., 2004; Kessler et al., 2005; Hawton et al., 2006; Hawton and Harriss, 2007).

Since school connectedness initially became a focus for enhancing well-being among students, the concept has broadened and research has proliferated in several interconnected domains, all of which need to be considered in strategies to ameliorate social disconnectedness among students. Bronfenbrenner's eco-systemic model (Bronfenbrenner, 1979) suggests that each level of a system impacts bi-directionally on others, and also that changes occur over time. For example, what is said about students in the staffroom impacts on student-teacher interactions in the classroom. Consequently, a change of leadership might also influence conversations across a school. Schools and other organizations are comprised of nested levels of a system, nothing stands alone. As an implication for practice, the following strategies should be considered when working on securing greater social connectedness in schools.

Whereas, school culture might be considered as “how we do things around here,” school climate might be defined as “how people feel about being here.” There is evidence that interventions that add to school culture and climate can help protect against the adverse effects of psycho-social stressors (Phongsavan et al., 2006; Long et al., 2020) as well as promote pro-social behavior and engagement (Jennings and Greenberg, 2009). A healthy school climate and culture is demonstrated by the way people talk to and about each other with an atmosphere that encapsulates calmness, purposefulness, warmth, safety, trust, inclusion, being visible, and being valued (Roffey, 2012; Long et al., 2020). It is about ensuring that everyone matters, not just an elite few.

A significant factor for students in terms of whether they experience a sense of connectedness in school is how they perceive their relationships with their teachers (Allen et al., 2018; Long et al., 2020). It matters that they feel “known, seen, and befriended” (p. 97) (Riley, 2019). Teachers can instill a sense of connectedness in many ways. It helps if they are friendly and approachable and make some effort to establish positive relationships with their students, finding out a little about them beyond academia. Students also need to feel they are treated fairly and that teachers do not jump to judgment. Strengths-based language is now widely acknowledged as more helpful and inclusive than deficit-based language. This can incorporate a focus on what a student has done well, aspects of their character that contribute to their learning and the value of making mistakes as a pathway to achievement. It is not only teachers that impact on students, but all other adults in the school from admin staff to caretakers and support personnel. When staff are offered professional development on the skills of positive relationships, it makes sense for all stakeholders to be included (Bronfenbrenner, 1979).

A sense of connectedness in school will not happen for students who feel they have no voice or that their voice is not heard. There are now schools who promote personalized learning so that students have a say in their learning goals. Those who follow individual sports will understand the concept of “personal bests” where an athlete may not necessarily win against others but exceed their prior best performance. Such a framework has been utilized in some schools as a way of reducing harsh competition in schools where students perceive themselves as winners or losers. Instead, they assess themselves on their past performance to identify both progress and next steps. A sense of connectedness is sometimes identified simply as students feeling welcomed, but this is not sufficient. They also need to know that they can participate and contribute, and that these contributions are valued. When students are empowered to make a difference, they develop confidence, competence and a sense of purpose (Riley, 2019). For students who struggle during school, the provision of extra-curricular activities, including trips and clubs can also help to enhance their social connectedness (Allen et al., 2018; Midgen et al., 2019).

Peer relationships are widely acknowledged as influencing students' mental health in both positive and negative ways (Gowing, 2019). There is a view that left to their own devices, adolescents may reject others either actively in bullying behaviors or passively by ignoring them. To ensure that everyone has a positive sense of connectedness in school, specific interventions may be needed to ensure that everyone feels both safe and included. Social and emotional learning (SEL) is now seen as a way forward in schools, not only for the development of individual knowledge and skills, but also to address perceptions of others and build community (Dobia et al., 2019; Singh and Duralappah, 2020). SEL cannot be effectively taught with a didactic pedagogy that tells students what to think and do. Some also note that it may not be a safe place for either teachers or students – with the fear that talking about feelings may lead to disclosures that teachers are not best placed to deal with (Ecclestone and Hayes, 2008). The ASPIRE pedagogy has been developed to address these concerns and implemented with students in diverse settings (Dobia et al., 2014). ASPIRE is an acronym that stands for Agency, Safety, Positivity, Inclusion, Respect, and Equity (Dobia and Roffey, 2017; Roffey, 2017, 2020). Students are given activities, games, hypotheticals and role-plays that encourage them to think about emotions, relationships and other important issues (but not incidents), discuss these with their peers, and focus on actions that support their own and others' wellbeing. Students are regularly mixed up in order to talk to peers outside their own social circle. The use of third person language enhances safety. Everything happens in pairs, small groups or a whole circle so there is no individual competitive element, while the need for academic skills is limited. Some activities are planned so that students get opportunities to laugh together with the understanding that this can enhance social connectedness. Teachers are also participants in activities which gives them a way to learn more about their students.

Much of the literature on school belonging does not discriminate between inclusive and exclusive (Roffey, 2013). There are schools who pride themselves on a sense of identity (e.g., with ceremonies, elite sports teams and academic excellence) but who maintain a sense of superiority by excluding those who do not “fit” (such students may not contribute to the school's reputation for outstanding exam results). Inclusive belonging entails valuing each and every student with the aim for them to become the best they can be in all aspects of their development and domains of learning. Whether or not this happens is determined by school culture, the leadership that influences this and the socio-political climate in which education is embedded.

Although there is no one panacea for students who feel alone, the section above is a brief non-exhaustive review of the many interventions that can enhance school connectedness. Many do not involve more resources, just a willingness to engage with the evidence of what works and to show care for vulnerable students. These are not only pro-active, preventative measures for students at risk, but also measures that elevate the educational experiences of all children and adolescents. We might well be asking why this is not happening routinely across all schools around the world.

Altogether, there is a need to prioritize mental health promotion–including social connectedness–in the youth sector, and frameworks have been developed precisely for this purpose (Kuosmanen et al., 2020). In terms of specific examples of interventions to promote mental health in schools, it is relevant to note that the Act-Belong-Commit campaign has been successful in enhancing well-being among both students and staff in Australian schools (Anwar-McHenry et al., 2016; Anwar McHenry et al., 2018), and is now also being implemented in university settings in the USA (Elon, 2019). The Act-Belong-Commit framework essentially promotes three behavioral domains known to contribute to good mental health: Keeping physically, mentally, socially, and spiritually active (Act); developing a sense of belonging through interaction with social support networks and participation in group and community activities (Belong); and taking on challenges and committing to causes and hobbies that provide meaning and purpose (Commit). The Act-Belong-Commit school framework enables the promotion of positive mental health using the campaign messages in a school setting by encouraging a whole-of-school approach to mental health promotion (Anwar McHenry et al., 2018).

Our results add to a large evidence-base showing that adolescents who experience any (out of four) types of social disconnectedness at school (lack of classmate or teacher support, lack of class social cohesion, not being part of the school community) are at heightened risk for mental health problems. A sizeable proportion of the associations between types of social disconnectedness and mental health outcomes are suggested to be accounted for by increases in loneliness. Further, increases in the number of social disconnectedness types are associated with incrementally higher risk for mental health problems. Strategies to foster social connectedness in the school setting could potentially prevent loneliness, which in turn would promote mental well-being and prevent mental health problems. Various relevant possibilities for intervention, policy, and practice in school settings have shown promising results and may be considered in mental health promotion and prevention efforts.

The data analyzed in this study is subject to the following licenses/restrictions: We do not have permission to share the data. Requests to access these datasets should be directed to dmVwaUBzZHUuZGs=.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Southern University of Denmark; Law department; ref: 10.130. The study complies with the Helsinki 2 Declaration on Ethics and is registered with the Danish Data Protection Authority; all confidentiality and privacy requirements were met. The participants' voluntary completion and return of the survey questionnaires constituted implied consent.

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

This work was supported by Nordea-fonden.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnbeh.2021.632906/full#supplementary-material

1. ^Wingspread Declaration: A National Strategy for Improving School Connectedness2003: University of Minnesota: Division of General Pediatrics & Adolescent Health.

Allen, K., Kern, M. L., Vella-Brodrick, D., Hattie, J., and Waters, L. (2018). What schools need to know about fostering school belonging: a meta-analysis. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 30, 1–34. doi: 10.1007/s10648-016-9389-8

Anwar McHenry, J., Joyce, P., Drane, C., and Donovan, R. (2018). Mentally Healthy WA's Act-Belong-Commit Schools Initiative: Impact Evaluation Report Perth: Mentally Healthy. Bentley, WA, Curtin University.

Anwar-McHenry, J., Donovan, R. J., Nicholas, A., Kerrigan, S., Francas, S., and Phan, T. (2016). Implementing a mentally healthy schools framework based on the population wide act-belong-commit mental health promotion campaign: a process evaluation. Health Educ. 116, 561–579. doi: 10.1108/HE-07-2015-0023

Bao, Z., Chen, C., Zhang, W., Jiang, Y., Zhu, J., and Lai, X. (2018). School connectedness and Chinese adolescents' sleep problems: a cross-lagged panel analysis. J. Sch. Health 88, 315–321. doi: 10.1111/josh.12608

Benner, A. D., Boyle, A. E., and Bakhtiari, F. (2017). Understanding students' transition to high school: demographic variation and the role of supportive relationships. J. Youth Adolesc. 46, 2129–2142. doi: 10.1007/s10964-017-0716-2

Berkman, L. F., Glass, T., Brissette, I., and Seeman, T. E. (2000). From social integration to health: durkheim in the new millennium. Soc. Sci. Med. 51, 843–857. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00065-4

Bond, L., Butler, H., Thomas, L., Carlin, J., Glover, S., Bowes, G., et al. (2007). Social and school connectedness in early secondary school as predictors of late teenage substance use, mental health, and academic outcomes. J. Adolesc. Health 40, 357.e9–357.e18. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.10.013

Bowling, A. (2005). Just one question: if one question works, why ask several? J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health 59, 342–345. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.021204

Breen, R., Karlson, K. B., and Holm, A. (2013). Total, direct, and indirect effects in logit and probit models. Sociol. Methods Res. 42, 164–191. doi: 10.1177/0049124113494572

Brunner, R., Kaess, M., Parzer, P., Fischer, G., Carli, V., Hoven, C. W., et al. (2014). Life-time prevalence and psychosocial correlates of adolescent direct self-injurious behavior: a comparative study of findings in 11 European countries. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 55, 337–348. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12166

Cacioppo, J. T., Chen, H. Y., and Cacioppo, S. (2017). Reciprocal influences between loneliness and self-centeredness: a cross-lagged panel analysis in a population-based sample of african american, hispanic, and caucasian adults. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 43, 1125–1135. doi: 10.1177/0146167217705120

Cavanaugh, A. M., and Buehler, C. (2015). Adolescent loneliness and social anxiety: the role of multiple sources of support. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 33, 149–170. doi: 10.1177/0265407514567837

Chu, P. S., Saucier, D. A., and Hafner, E. (2010). Meta-analysis of the relationships between social support and well-being in children and adolescents. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 29, 624–645. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2010.29.6.624

Costello, D. M., Swendsen, J., Rose, J. S., and Dierker, L. C. (2008). Risk and protective factors associated with trajectories of depressed mood from adolescence to early adulthood. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 76, 173–183. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.2.173

de Jong Gierveld, J., and Havens, B. (2004). Cross-national comparisons of social isolation and loneliness: introduction and overview. Can. J. Aging 23, 109–113. doi: 10.1353/cja.2004.0021

Dobia, B., Bodkin-Andrews, G., Parada, R. H., O'Rourke, V., Gilbert, S., and Roffey, S. (2014). The Aboriginal Girls' Circle: Enhancing connectedness and promoting resilience for Aboriginal girls: Final report. Penrith, NSW: University of Western Sydney.

Dobia, B., Parada, R., Roffey, S., and Smith, M. (2019). Social and emotional learning: from individual skills to group cohesion. Educ. Child Psychol. 36, 79–90. doi: 10.1080/0305.764X

Dobia, B., and Roffey, S. (2017). “Respect for culture: social and emotional learning with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Youth,” in Social and Emotional Learning in Australia and the Asia Pacific, eds R. Collie, E. Frydenberg, and A. Martin (Berlin: Springer), 313–334.

Due, P., Diderichsen, F., Meilstrup, C., Nordentoft, M., Obel, C., and Sandbæk, A. (2014). Børn og unges mentale sundhed. Forekomst af psykiske symptomer og lidelse og mulige forebyggelsesindsatser. København: Vidensråd for Forebyggelse.

Eccles, A. M., and Qualter, P. (2020). Review: alleviating loneliness in young people—a meta-analysis of interventions. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 26, 17–33. doi: 10.1111/camh.12389

Ecclestone, K., and Hayes, D. (2008). The Dangerous Rise of Therapeutic Education. London: Routledge.

Elon (2019). ABC Framework for a Mentally Healthy Elon. Elon, NC: Elon University. Available online at: https://www.elon.edu/u/wellness-initiative/ (accessed January 1, 2021).

English, T., and Carstensen, L. L. (2014). Selective narrowing of social networks across adulthood is associated with improved emotional experience in daily life. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 38, 195–202. doi: 10.1177/0165025413515404

Fergusson, D. M., and Woodward, L. J. (2002). Mental health, educational, and social role outcomes of adolescents with depression. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 59, 225–231. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.3.225

Fiori, K. L., and Consedine, N. S. (2013). Positive and negative social exchanges and mental health across the transition to college: loneliness as a mediator. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 30, 920–941. doi: 10.1177/0265407512473863

Flanders, W. D., Lin, L., Pirkle, J. L., and Caudill, S. P. (1992). Assessing the direction of causality in cross-sectional studies. Am. J. Epidemiol. 135, 926–935. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116388

Foster, C. E., Horwitz, A., Thomas, A., Opperman, K., Gipson, P., Burnside, A., et al. (2017). Connectedness to family, school, peers, and community in socially vulnerable adolescents. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 81, 321–331. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.08.011

Goodenow, C. (1993). The psychological sense of school membership among adolescents: scale development and educational correlates. Psychol. Sch. 30, 79–90.

Goossens, L. (2018). Loneliness in adolescence: insights from cacioppo's evolutionary model. Child Dev. Perspect. 12, 230–234. doi: 10.1111/cdep.12291

Gowing, A. (2019). Peer-peer relationships: a key factor in enhancing school connectedness and belonging. Educ. Child Psychol. 36, 64–77.

Green, H., McGinnity, Á., Meltzer, H., Ford, T., and Goodman, R. (2004). Mental Health of Children and Young People in Great Britain. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Harrington, R., and Clark, A. (1998). Prevention and early intervention for depression in adolescence and early adult life. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience.; 248(1):32–45. doi: 10.1007/s004060050015

Hawton, K., and Harriss, L. (2007). Deliberate self-harm in young people: characteristics and subsequent mortality in a 20-year cohort of patients presenting to hospital. J. Clin. Psychiatry 68, 1574–1583. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v68n1017

Hawton, K., Rodham, K., and Evans, E. (2006). By Their Own Young Hand: Deliberate Self-Harm and Suicidal Ideas in Adolescents. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers. https://www.google.com/search?sxsrf=ALeKk03R3uMFEdK7YxB5qFvMFxEAJfzt6w:1615979870126&q=London&stick=H4sIAAAAAAAAAOPgE-LUz9U3SDHKTq9Q4gAxTbIKcrSMMsqt9JPzc3JSk0sy8_P084vSE_MyqxJBnGKrjNTElMLSxKKS1KJihZz8ZLDwIlY2n_y8lPy8HayMAPEDHRFXAAAA&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwi-uf2QmrfvAhU34HMBHYB4BX8QmxMoATAZegQIHRAD

Heinrich, L. M., and Gullone, E. (2006). The clinical significance of loneliness: a literature review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 26, 695–718. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.04.002

Jennings, P. A., and Greenberg, M. T. (2009). The prosocial classroom: teacher social and emotional competence in relation to student and classroom outcomes. Rev. Educ. Res. 79, 491–525. doi: 10.3102/0034654308325693

Jensen, H. A. R., Davidsen, M., Ekholm, O., and Christensen, A. I. (2018). Danskernes sundhed: Den Nationale Sundhedsprofil 2017. København: Sundhedsstyrelsen.

Jeppesen, P., Obel, C., Lund, L., Madsen, K. B., Nielsen, L., and Nordentoft, M. (2020). Mental sundhed og sygdom hos børn og unge i alderen 10-24 år - forekomst, udvikling og forebyggelsesmuligheder. København: Vidensråd for Forebyggelse.

Jose, P. E., and Lim, B. T. L. (2014). Social connectedness predicts lower loneliness and depressive symptoms over time in adolescents. Open J. Depress. 3:10. doi: 10.4236/ojd.2014.34019

Jose, P. E., Ryan, N., and Pryor, J. (2012). Does social connectedness promote a greater sense of well-being in adolescence over time? J. Res. Adolesc. 22, 235–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2012.00783.x

Kessler, R. C., Berglund, P., Demler, O., Jin, R., Merikangas, K. R., and Walters, E. E. (2005). Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of dsm-iv disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 62, 593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593

Kidger, J., Araya, R., Donovan, J., and Gunnell, D. (2012). The effect of the school environment on the emotional health of adolescents: a systematic review. Pediatrics 129:925. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2248

Kieling, C., Baker-Henningham, H., Belfer, M., Conti, G., Ertem, I., Omigbodun, O., et al. (2011). Child and adolescent mental health worldwide: evidence for action. Lancet 378, 1515–1525. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60827-1

Kiesner, J., Poulin, F., and Nicotra, E. (2003). Peer relations across contexts: individual-network homophily and network inclusion in and after school. Child Dev. 74, 1328–1343. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00610

Klemera, E., Brooks, F. M., Chester, K. L., Magnusson, J., and Spencer, N. (2017). Self-harm in adolescence: protective health assets in the family, school, and community. Int. J. Public Health 62, 631–638. doi: 10.1007/s00038-016-0900-2

Kohler, U., Karlson, K. B., and Holm, A. (2011). Comparing coefficients of nested nonlinear probability models. Stata J. 11, 420–438. doi: 10.1177/1536867X1101100306

Kokkevi, A., Rotsika, V., Arapaki, A., and Richardson, C. (2012). Adolescents' self-reported suicide attempts, self-harm thoughts, and their correlates across 17 European countries. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 53, 381–389. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02457.x

Kõlves, K., and De Leo, D. (2016). Adolescent suicide rates between 1990 and 2009: analysis of age group 15–19 years worldwide. J. Adolesc. Health 58, 69–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.09.014

Kong, F., and You, X. (2013). Loneliness and self-esteem as mediators between social support and life satisfaction in late adolescence. Soc. Indic. Res. 110, 271–279. doi: 10.1007/s11205-011-9930-6

Koushede, V., Lasgaard, M., Hinrichsen, C., Meilstrup, C., Nielsen, L., Rayce, S. B., et al. (2019). Measuring mental well-being in Denmark: validation of the original and short version of Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale (WEMWBS and SWEMWBS) and cross-cultural comparison across four European settings. Psychiatry Res. 271, 502–509. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.12.003

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., Williams, J. B., and Lowe, B. (2009). An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: the PHQ-4. Psychosomatics 50, 613–621. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.50.6.613

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., Williams, J. B., and Lowe, B. (2010). The patient health questionnaire somatic, anxiety, and depressive symptom scales: a systematic review. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 32, 345–359. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.03.006

Kuosmanen, T., Dowling, K., and Barry, M. M. (2020). A Framework for Promoting Positive Mental Health and Wellbeing in the European Youth Sector. Galway: World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Health Promotion Research, National University of Ireland Galway.

LaRusso, M. D., Romer, D., and Selman, R. L. (2007). Teachers as builders of respectful school climates: implications for adolescent drug use norms and depressive symptoms in high school. J. Youth Adolesc. 37:386. doi: 10.1007/s10964-007-9212-4

Lasgaard, M., Goossens, L., and Elklit, A. (2011). Loneliness, depressive symptomatology, and suicide ideation in adolescence: cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 39, 137–150. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9442-x

Laursen, B., and Hartl, A. C. (2013). Understanding loneliness during adolescence: developmental changes that increase the risk of perceived social isolation. J. Adolesc. 36, 1261–1268. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.06.003

Lin, H.-C., Tang, T.-C., Yen, J.-Y., Ko, C.-H., Huang, C.-F., Liu, S.-C., et al. (2008). Depression and its association with self-esteem, family, peer, and school factors in a population of 9586 adolescents in southern Taiwan. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 62, 412–420. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2008.01820.x

Long, E., Zucca, C., and Sweeting, H. (2020). School climate, peer relationships, and adolescent mental health: a social ecological perspective. Youth Soc. 1–16. doi: 10.1177/0044118X20970232

Loukas, A., and Robinson, S. (2004). Examining the moderating role of perceived school climate in early adolescent adjustment. J. Res. Adolesc. 14, 209–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2004.01402004.x

Masi, C. M., Chen, H. Y., Hawkley, L. C., and Cacioppo, J. T. (2011). A meta-analysis of interventions to reduce loneliness. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. Off. J. Soc. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Inc. 15, 219–266. doi: 10.1177/1088868310377394

Maume, D. J. (2013). Social ties and adolescent sleep disruption. J. Health Soc. Behav. 54, 498–515. doi: 10.1177/0022146513498512

McGraw, K., Moore, S., Fuller, A., and Bates, G. (2008). Family, peer, and school connectedness in final year secondary school students. Aust. Psychol. 43, 27–37. doi: 10.1080/00050060701668637

McLaughlin, C., and Clarke, B. (2010). Relational matters: a review of the impact of school experience on mental health in early adolescence. Educ. Child Psychol. 27, 91–103.

Midgen, T., Theodoratou, T., Newbury, K., and Leonard, M. (2019). “School for Everyone:” an exploration of children and young people's perceptions of belonging. Educ. Child Psychol. 36, 9–22.

Murberg, T. A., and Bru, E. (2004). Social support, negative life events, and emotional problems among norwegian adolescents. Sch. Psychol. Int. 25, 387–403. doi: 10.1177/0143034304048775

Olsson, C. A., McGee, R., Nada-Raja, S., and Williams, S. M. (2013). A 32-year longitudinal study of child and adolescent pathways to well-being in adulthood. J. Happiness Stud. 14, 1069–1083. doi: 10.1007/s10902-012-9369-8

Osterman, K. F. (2000). Students' need for belonging in the school community. Rev. Educ. Res. 70, 323–367. doi: 10.3102/00346543070003323

Ozbay, F., Johnson, D. C., Dimoulas, E., Morgan, C. A., Charney, D., and Southwick, S. (2007). Social support and resilience to stress: from neurobiology to clinical practice. Psychiatry (Edgmont) 4, 35–40. doi: 10.1007/s11920-008-0049-7

Patton, G. C., Glover, S., Bond, L., Butler, H., Godfrey, C., Pietro, G. D., et al. (2000). The gatehouse project: a systematic approach to mental health promotion in secondary schools. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 34, 586–593. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2000.00718.x

Pedersen, C. B. (2011). The danish civil registration system. Scand. J. Public Health 39(Suppl. 7), 22–25. doi: 10.1177/1403494810387965

Phongsavan, P., Chey, T., Bauman, A., Brooks, R., and Silove, D. (2006). Social capital, socio-economic status,and psychological distress among Australian adults. Soc. Sci. Med. 63, 2546–2561. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.06.021

Pisinger, V., Thorsted, A., Jezek, A. H., Jørgensen, A., Christensen, A. I., and Thygesen, L. C. (2019). UNG19–Sundhed og trivsel på gymnasiale uddannelser 2019. København: Statens Institut for Folkesundhed.

Pisinger, V., Thorsted, A., Jezek, A. H., Jørgensen, A., Christensen, A. I., Tolstrup, J. S., et al. (2021). The Danish National Youth Study 2019: study design and participant characteristics. Scand. J. Public Health 1–10. doi: 10.1177/1403494821993724

Polanczyk, G. V., Salum, G. A., Sugaya, L. S., Caye, A., and Rohde, L. A. (2015). Annual research review: a meta-analysis of the worldwide prevalence of mental disorders in children and adolescents. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 56, 345–365. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12381

Riley, K. (2019). Agency and belonging: what transformative actions can schools take to help create a sense of place and belonging? Educ. Child Psychol. 36:13.

Roffey, S. (2012). “Developing positive relationships in schools,” in Positive Relationships: Evidence-Based Practice Across the World, ed S. Roffey (Dordrecht, NL: Springer), 145–162.

Roffey, S. (2013). Inclusive and exclusive belonging: the impact on individual and community wellbeing. Educ. Child Psychol. 30, 38–48.

Roffey, S. (2017). The ASPIRE principles and pedagogy for the implementation of social-emotional learning and whole school wellbeing. Int. J. Emot. Educ. 9, 59–71.

Roffey, S. (2020). Circle Solutions for Student Wellbeing, 3rd Edn. https://www.google.com/search?sxsrf=ALeKk03tOOKbPtKTmyJt_6803JdMOci90g:1615994963128&q=Thousand+Oaks,+California&stick=H4sIAAAAAAAAAOPgE-LUz9U3sEw2MC9R4gAxiyySLbSMMsqt9JPzc3JSk0sy8_P084vSE_MyqxJBnGKrjNTElMLSxKKS1KJihZz8ZLDwIlbJkIz80uLEvBQF_8TsYh0F58SczLT8orzMxB2sjABqF7C_agAAAA&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwi5pPGt0rfvAhWMwjgGHe4KBrIQmxMoATAoegQIHBAD Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Rueger, S. Y., Malecki, C. K., and Demaray, M. K. (2010). Relationship between multiple sources of perceived social support and psychological and academic adjustment in early adolescence: comparisons across gender. J. Youth Adolesc. 39, 47–61. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9368-6

Shochet, I. M., Dadds, M. R., Ham, D., and Montague, R. (2006). School connectedness is an underemphasized parameter in adolescent mental health: results of a community prediction study. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 35, 170–179. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3502_1

Shochet, I. M., Homel, R., Cockshaw, W. D., and Montgomery, D. T. (2008). How do school connectedness and attachment to parents interrelate in predicting adolescent depressive symptoms? J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 37, 676–681. doi: 10.1080/15374410802148053

Singh, N. C., and Duralappah, A., (eds.). (2020). Rethinking Learning: A Review of Social and Emotional Learning for Education Systems. Delhi: UNESCO/MGIEP.

Song, J., Bong, M., Lee, K., and Kim, S.-I. (2015). Longitudinal investigation into the role of perceived social support in adolescents' academic motivation and achievement. J. Educ. Psychol. 107:821. doi: 10.1037/edu0000016

Sun, R. C. F., and Hui, E. K. P. (2007). Psychosocial factors contributing to adolescent suicidal ideation. J. Youth Adoles. 36, 775–786. doi: 10.1007/s10964-006-9139-1

Thygesen, L. C., Daasnes, C., Thaulow, I., and Brønnum-Hansen, H. (2011). Introduction to Danish (nationwide) registers on health and social issues: structure, access, legislation, and archiving. Scand. J. Public Health 39(Suppl. 7), 12-16. doi: 10.1177/1403494811399956

Uchino, B. N., Bowen, K., Carlisle, M., and Birmingham, W. (2012). Psychological pathways linking social support to health outcomes: a visit with the “ghosts” of research past, present, and future. Soc. Sci. Med. 74, 949–957. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.11.023

Undheim, A. M., and Sund, A. M. (2005). School factors and the emergence of depressive symptoms among young Norwegian adolescents. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 14, 446–453. doi: 10.1007/s00787-005-0496-1

van den Bos, W., Crone, E. A., Meuwese, R., and Güroglu, B. (2018). Social network cohesion in school classes promotes prosocial behavior. PLoS ONE 13:e0194656. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0194656

Vanhalst, J., Klimstra, T. A., Luyckx, K., Scholte, R. H. J., Engels, R. C. M. E., and Goossens, L. (2012). The interplay of loneliness and depressive symptoms across adolescence: exploring the role of personality traits. J. Youth Adolesc. 41, 776–787. doi: 10.1007/s10964-011-9726-7

Waters, S. K., Cross, D. S., and Runions, K. (2009). Social and ecological structures supporting adolescent connectedness to school: a theoretical model. J. Sch. Health 79, 516–524. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2009.00443.x

Way, N., Reddy, R., and Rhodes, J. (2007). Students' perceptions of school climate during the middle school years: associations with trajectories of psychological and behavioral adjustment. Am. J. Commun. Psychol. 40, 194–213. doi: 10.1007/s10464-007-9143-y

Wilkinson-Lee, A. M., Zhang, Q., Nuno, V. L., and Wilhelm, M. S. (2011). Adolescent emotional distress: the role of family obligations and school connectedness. J. Youth Adolesc. 40, 221–230. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9494-9

Williams, K. L., and Galliher, R. V. (2006). Predicting depression and self–esteem from social connectedness, support, and competence. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 25, 855–874. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2006.25.8.855

Keywords: adolescence, social connectedness, loneliness, mental health, well-being

Citation: Santini ZI, Pisinger VSC, Nielsen L, Madsen KR, Nelausen MK, Koyanagi A, Koushede V, Roffey S, Thygesen LC and Meilstrup C (2021) Social Disconnectedness, Loneliness, and Mental Health Among Adolescents in Danish High Schools: A Nationwide Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 15:632906. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2021.632906

Received: 24 November 2020; Accepted: 12 March 2021;

Published: 12 April 2021.

Edited by:

Erin P. Hambrick, University of Missouri–Kansas City, United StatesReviewed by:

Lawrence Elledge, The University of Tennessee, United StatesCopyright © 2021 Santini, Pisinger, Nielsen, Madsen, Nelausen, Koyanagi, Koushede, Roffey, Thygesen and Meilstrup. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ziggi Ivan Santini, emlnZ2kuc2FudGluaUBnbWFpbC5jb20=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.