- Department of Pathology and Cell Biology, Center for Motor Neuron Biology and Disease, College of Physicians and Surgeons, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a neurodegenerative disorder that affects about 1.5% of the global population over 65 years of age. A hallmark feature of PD is the degeneration of the dopamine (DA) neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc) and the consequent striatal DA deficiency. Yet, the pathogenesis of PD remains unclear. Despite tremendous growth in recent years in our knowledge of the molecular basis of PD and the molecular pathways of cell death, important questions remain, such as: (1) why are SNc cells especially vulnerable; (2) which mechanisms underlie progressive SNc cell loss; and (3) what do Lewy bodies or α-synuclein reveal about disease progression. Understanding the variable vulnerability of the dopaminergic neurons from the midbrain and the mechanisms whereby pathology becomes widespread are some of the primary objectives of research in PD. Animal models are the best tools to study the pathogenesis of PD. The identification of PD-related genes has led to the development of genetic PD models as an alternative to the classical toxin-based ones, but does the dopaminergic neuronal loss in actual animal models adequately recapitulate that of the human disease? The selection of a particular animal model is very important for the specific goals of the different experiments. In this review, we provide a summary of our current knowledge about the different in vivo models of PD that are used in relation to the vulnerability of the dopaminergic neurons in the midbrain in the pathogenesis of PD.

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a common neurodegenerative disorder whose prevalence increases with age (Pringsheim et al., 2014). The cardinal features of PD include tremor, rigidity and slowness of movements, albeit non-motor manifestations such as depression and sleep disturbances are increasingly recognized in these patients (Rodriguez-Oroz et al., 2009). Over the past decade, more attention has also been paid to the broader nature of the neurodegenerative changes in the brains of PD patients. Indeed, for many years, the neuropathological focus has been on the striking neurodegeneration of the nigrostriatal dopaminergic pathway, however, nowadays, disturbances of the serotonergic, noradrenergic, glutamatergic, GABAergic, and cholinergic systems (Brichta et al., 2013) as well as alterations in neural circuits are now being intensively investigated from the angle of the pathophysiology of PD (Obeso et al., 2014), with the underlying expectation of acquiring a better understanding of the neurobiology of this disabling disorder and of identifying new targets for therapeutic purposes. From a molecular biology point of view, the accepted opinion that the PD neurodegenerative process affects much more than the dopaminergic neurons of the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc), has triggered a set of fascinating questions such as: are dopaminergic and non-dopaminergic neurons in PD dying by the same pathogenic mechanisms; and, given the fact that within a given subtype of neurons, not all die to the same extent nor at the same rate [e.g., dopaminergic neurons in the SNc vs. ventral tegmental area (VTA)], what are the molecular determinants of susceptibly/and resistance to disease?

To gain insights into these types of critical questions, a brief review of the literature demonstrates that the enthusiasm for experimental models of PD, both in vitro and in vivo, has greatly increased, in part, thanks to new strategies for producing sophisticated models, such as the temporal- and/or cell-specific expression of mutated genes in mice (Dawson et al., 2010), human pluripotent cells coaxed into a specific type of neurons (Berg et al., 2014), and a host of invertebrate organisms like Drosophila (Guo, 2012), Caenorhabditis elegans (Chege and McColl, 2014), or Medaka fish (Matsui et al., 2014). Thus far, however, all of these experimental models continue to be categorized into two main flavors: toxic and genetic (and sometimes, both approaches are combined). But, more importantly, none of the currently available models phenocopy PD, mainly because they lack some specific neuropathological and/or behavioral feature of PD. Some PD experts see this as fatal flaws, while others tend to ignore the shortcomings. It has always been our personal view that models are just models and, as such, given the large collection of models the field of PD possesses, the prerequisite resides in not using just any model but in selecting the optimal in vitro or in vivo model whose strengths are appropriate for investigating the question being asked and whose weaknesses will not invalidate the interpretation of an experiment.

Based on our above premise, herein, we discuss the experimental models of PD, with a deliberate emphasis on in vivo mammalian models induced by reproducible means. Over the years, a constellation of uncommon strategies and organisms have been used to produce models of PD. However, in this review, we have decided not to discuss these cases, because we have limited space and because we are missing sufficient independent information to assessment the reproducibility and reliability of these models, which, to us, is critical for distinguishing between interesting “case reports” and useful tools to model human diseases.

Toxin Models

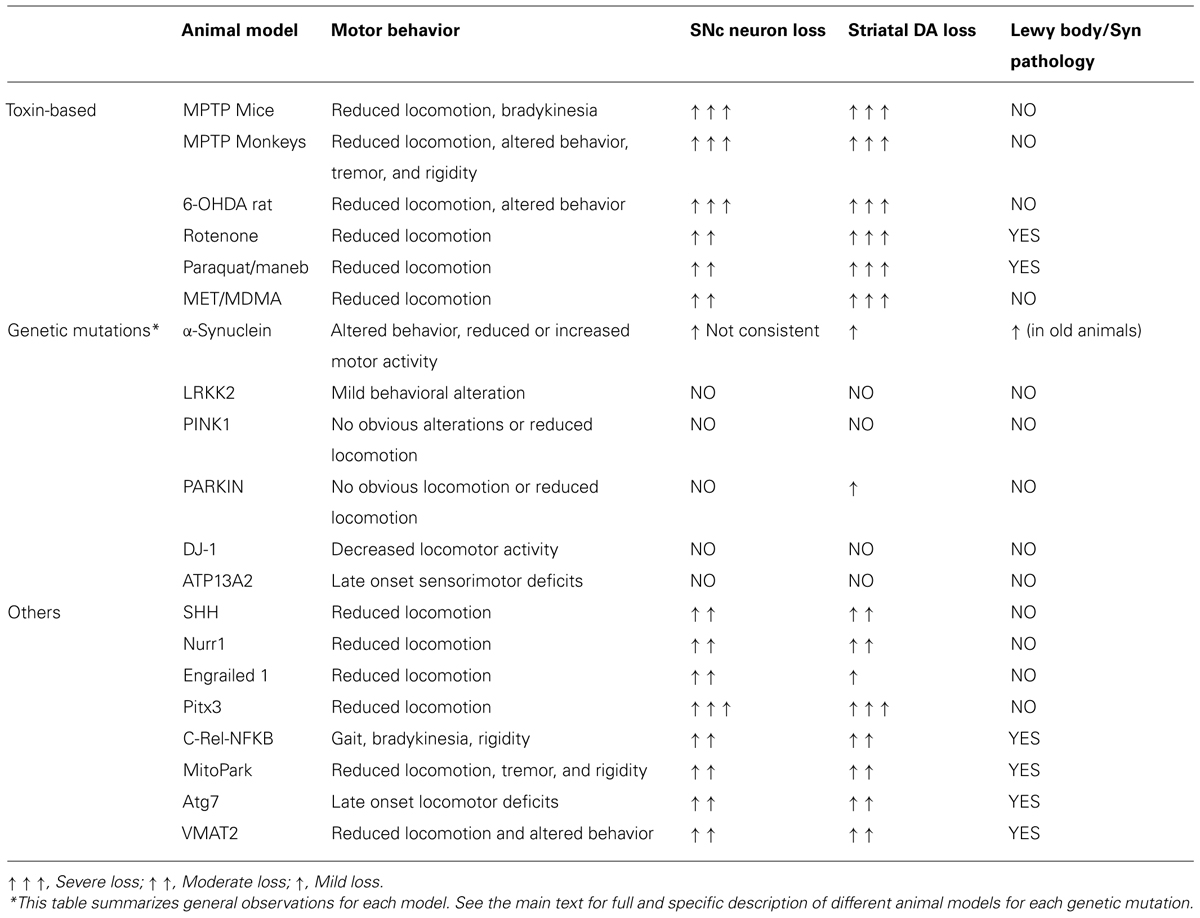

A number of pharmacological and toxic agents including reserpine, haloperidol, and inflammogens like lipopolysaccharide have been used over the years to model PD, although the two most widely used are still the classical 6-OHDA in rats and MPTP in mice and monkeys. Although the neurotoxic models appear to be the best ones for testing degeneration of the nigrostriatal pathway, some striking departures from PD need to be mentioned: the degeneration of dopaminergic neurons progress rapidly, i.e., days not years, lesions are primarily if not exclusively dopaminergic, and animals lack the typical PD proteinaceous inclusions called Lewy bodies (LBs). In addition, behavioral abnormalities in these animal models are also a challenging question (see below; Table 1).

MPTP

MPTP is the tool of choice for investigations into the mechanisms involved in the death of DA neurons in PD. MPTP has been shown to be toxic in a large range of species (Tieu, 2011). The most popular species, besides primates, is the mouse, as rats were found to be resistant to this toxin (Chiueh et al., 1984). A number of intoxication regimens or administration methods have been used over the years in mouse (Jackson-Lewis and Przedborski, 2007; Meredith et al., 2008) and in primates (Bezard et al., 1997; Blesa et al., 2012; Porras et al., 2012). In both species, MPTP primarily causes damage to the nigrostriatal DA pathway with a profound loss of DA in the striatum and SNc (Dauer and Przedborski, 2003).

This specific and reproducible neurotoxic effect on the nigrostriatal system is the strength of this model. Neuropathological data show that MPTP administration causes damage to the nigrostriatal DA pathway that is identical to that seen in PD (Langston et al., 1983), yet there is a resemblance that goes beyond the loss of SNc DA neurons. Like in PD, MPTP causes greater loss of DA neurons in SNc than in VTA or retrorubral field (Seniuk et al., 1990; Muthane et al., 1994; Blesa et al., 2011, 2012) and, at least in monkeys treated with low doses of MPTP, greater degeneration of DA nerve terminals in the putamen than in the caudate nucleus (Moratalla et al., 1992; Snow et al., 2000; Blesa et al., 2010).

A often raised weakness with this model is the lack of LB (Shimoji et al., 2005; Halliday et al., 2009). Although no LBs have been observed in these models so far, a few reports have investigated the expression, regulation or pattern of α-syn after MPTP exposure (Vila et al., 2000; Dauer et al., 2002; Purisai et al., 2005). Only, in MPTP-injected monkeys, have intraneuronal inclusions, reminiscent of LBs, been described (Forno et al., 1986; Kowall et al., 2000). Behavior is also an issue, and except for the monkeys, features reminiscent of PD are lacking especially in mice. Yet, using a battery of tests, some motor alterations in mice with profound dopaminergic deficit may be detected (Taylor et al., 2010).

6-OHDA

Like MPTP, 6-OHDA is a selective catecholaminergic neurotoxin that is used, mainly, to generate lesions in the nigrostriatal DA neurons in rats (Ungerstedt, 1968). Since 6-OHDA cannot cross the blood-brain barrier, systemic administration fails to induce parkinsonism. So, this induction model requires that 6-OHDA be injected (typically as a unilateral injection) into the SNc, medial forebrain bundle or striatum (Blandini et al., 2008). Intraventricular administration has also been achieved (Rodríguez Díaz et al., 2001). The effects resemble those in the acute MPTP model, causing neuronal death over a brief time course (12 h to 2–3 days). The intrastriatal injection of 6-OHDA causes progressive retrograde neuronal degeneration in the SNc and VTA (Sauer and Oertel, 1994; Przedborski et al., 1995). The pattern of DA loss in animals bearing a full lesion (>90%) again mirrors seen that in PD, with the SNc showing more cells loss compared to the VTA (Przedborski et al., 1995). As in PD, DA neurons are killed, and the non-DA neurons are preserved. However, like in the MPTP model, 6-OHDA does not produce LB-like inclusions in the nigrostriatal pathway. Traditionally, behavioral assessments of motor impairments in the unilateral 6-OHDA model are done by drug-induced rotation tests (Dunnett and Lelos, 2010). However, drug-free sensorimotor behavioral tests have been developed in both rat and mice that may be helpful for the preclinical testing of new symptomatic strategies (Schallert et al., 2000; Glajch et al., 2012).

Rotenone

Chronic systemic exposure to rotenone in rats causes many features of PD, including nigrostriatal DA degeneration (Betarbet et al., 2000). The rotenone-administered animal model also reproduces all of the behavioral features reminiscent of human PD. Importantly, many of the degenerating neurons have intracellular inclusions that resemble LB morphologically. These inclusions show immunoreactivity for α-syn and ubiquitin as did the original LB (Sherer et al., 2003). Usually, rotenone is administered by daily intraperitoneal injection (Cannon et al., 2009), intravenously or subcutaneously (Fleming et al., 2004). Recently, rotenone has been tested in mice through chronic intragastric administration, (Pan-Montojo et al., 2010) or as a stereotaxic injection or infusion directly in the brain (Alam et al., 2004; Xiong et al., 2009) recapitulating the slow and specific loss of DA neurons. However, administration of rotenone in rats causes high mortality and, somehow, is difficult to replicate.

Paraquat/Maneb

Although the idea that the herbicide paraquat (N,N′-dimethyl-4-4-4′-bypiridinium), may cause parkinsonism in humans has attracted some interest, at this time, as pointed out by Berry and collaborators, epidemiological and clinical evidence that paraquat may cause PD is inconclusive (Berry et al., 2010). And, the same view seems to apply to the fungicide maneb (manganese ethylenebisdithiocarbamate; Berry et al., 2010). Moreover, effects of this compound in the nigrostriatal DA system is somewhat ambiguous (Freire and Koifman, 2012). Regarding animal models, some researchers report that, following the systemic application of paraquat, mice exhibit reduced motor activity and a dose-dependent loss of striatal tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) fibers and SNc neurons with relative sparing of the VTA (Brooks et al., 1999; Day et al., 1999; McCormack et al., 2002; Rappold et al., 2011). Like rotenone, paraquat may be useful in the laboratory because of its presumed ability to induce LB in DA neurons (Manning-Bog et al., 2002). Maneb has been shown to decrease locomotor activity and produce SNc neurons loss (Thiruchelvam et al., 2003) and potentiate both the MPTP and the paraquat effects (Takahashi et al., 1989; Thiruchelvam et al., 2000; Bastías-Candia et al., 2013). However, as with rotenone, this model shows contradictory results, variable cell death and loss of striatal DA content (Miller, 2007).

Amphetamine-Type Psychostimulants

Some amphetamine derivatives such as methamphetamine (METH) and 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) also have neurotoxic effects on the nervous system causing not only functional deficits but also structural alterations (Cadet et al., 2007; Thrash et al., 2009). The first study to show DA depletion in rats following repeated, high-dose exposure to METH was conducted by Kogan et al. (1976). Hess et al. (1990) and Sonsalla et al. (1996) showed that high-dose treatment with METH in mice resulted in a loss of DA cells in the SNc. Since then, several studies have reported selective DA or serotonergic nerve terminal as well as SNc neuronal loss in rodents, primates or even guinea pig following the administration of very high doses of METH (Wagner et al., 1979; Trulson et al., 1985; Howard et al., 2011; Morrow et al., 2011).

3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine can also elicit significant neurobehavioral adverse effects. Although MDMA toxicity mainly affects the serotonergic system, DA system can also be affected to a lesser extent (Jensen et al., 1993; Capela et al., 2009). In mice, repeated administration of MDMA produces degeneration of DA terminals in the striatum (O’Callaghan and Miller, 1994; Granado et al., 2008a,b) and TH+ neuronal loss in the SNc (Granado et al., 2008b).

Exposure to low concentrations of METH results in a decrease of the vulnerability of the SNc DA cells to toxins like 6-OHDA or MPTP (Sziráki et al., 1994; El Ayadi and Zigmond, 2011). On the other hand, chronic exposure to MDMA of adolescent mice exacerbates DA neurotoxicity elicited by MPTP in the SNc and striatum at adulthood (Costa et al., 2013). Hence, a METH or MDMA-treated animal model could be useful to study the mechanisms of DA neurodegeneration (Thrash et al., 2009).

Genetic Models

Genetic models may better simulate the mechanisms underlying the genetic forms of PD, even though their pathological and behavioral phenotypes are often quite different from the human condition. A number of cellular and molecular dysfunctions have been shown to result from these gene defects like fragmented and dysfunctional mitochondria (Exner et al., 2012; Matsui et al., 2014; Morais et al., 2014), altered mitophagy (Lachenmayer and Yue, 2012; Zhang et al., 2014), ubiquitin–proteasome dysfunction (Dantuma and Bott, 2014), and altered reactive oxygen species production and calcium handling (Gandhi et al., 2009; Joselin et al., 2012; Ottolini et al., 2013). Some studies have reported alterations in motor function and behavior in these mice (Hinkle et al., 2012; Hennis et al., 2013; Vincow et al., 2013), and sensitivities to complex I toxins, like MPTP, different from wild type (WT) mice (Dauer et al., 2002; Nieto et al., 2006; Haque et al., 2012) although this latter finding is not always consistent (Rathke-Hartlieb et al., 2001; Dong et al., 2002). However, almost all of the studies evaluating the integrity of the nigrostriatal DA system in these genetic models failed to find significant loss of DA neurons (Goldberg et al., 2003; Andres-Mateos et al., 2007; Hinkle et al., 2012; Sanchez et al., 2014). Thus, recapitulation of the genetic alterations in mice is insufficient to reproduce the final neuropathological feature of PD. Below, we describe transgenic mice or rat models which recapitulate the most known mutations observed in familial PD patients (Table 1).

α-Synuclein

α-syn was the first gene linked to a dominant-type, familial PD, called Park1, and is the main component of LB which are observed in the PD brain (Goedert et al., 2013). Three missense mutations of α-syn, encoding the substitutions A30P, A53T, and E46K, have been identified in familial PD so far (Vekrellis et al., 2011; Schapira et al., 2014). Furthermore, the duplication or triplication of α-syn is sufficient to cause PD, suggesting that the level of α-syn expression is a critical determinant of PD progression (Singleton et al., 2003; Kara et al., 2014).

To date, various α-syn transgenic mice have been developed. Although, in some of these mice, decreased striatal levels of TH or DA and behavioral impairments indicate that the accumulation of α-syn can significantly alter the functioning of DA neurons, no significant nigrostriatal degeneration has been found in most of them. The models of α-syn overexpression in mice recapitulate the neurodegeneration, depending primarily on the promoter used to drive the expression of the transgene, whether the transgene codes for the WT or the mutated protein, and the level of expression.

Although a lot of behavioral alterations have been described in both the A30P and A53T mice (Sotiriou et al., 2010; Oaks et al., 2013; Paumier et al., 2013), the mouse prion protein promoter failed to reproduce the cell loss in the SNc or locus coeruleus (LC; van der Putten et al., 2000; Giasson et al., 2002; Gispert et al., 2003). The same phenotype was found with the hamster prion promoter (Gomez-Isla et al., 2003). Mice based on the PDGF-β promoter showed loss of terminals and DA in the striatum but no TH+ cell loss (Masliah et al., 2000). The TH promoter led to TH+ cell loss only in a few studies (Thiruchelvam et al., 2004; Wakamatsu et al., 2008) but did not replicate the α-syn neuropathology as did the Thy-1 promoter (Matsuoka et al., 2001; Chen et al., 2006; Miller et al., 2007; Su et al., 2009). However, the use of the murine Thy-1 promoter often causes loss of DA levels in the striatum but only moderate nigral DA cell loss in the SNc, with α-syn pathology (van der Putten et al., 2000; Rockenstein et al., 2002; Ikeda et al., 2009; Ono et al., 2009; Lam et al., 2011). A new line of tetracycline-regulated inducible transgenic mice that overexpressed α-syn A53T under control of the promoter of Pitx3 in the DA neurons developed profound motor disabilities and robust midbrain neurons neurodegeneration, profound decrease of DA release, the fragmentation of Golgi apparatus, and the impairments of autophagy/lysosome degradation pathways (Lin et al., 2012). Janezic et al. (2013) generated BAC transgenic mice (SNCA-OVX) that express WT human α-syn and which display an age-dependent loss of SNc DA neurons preceded by early deficits in DA release from terminals in the dorsal striatum, protein aggregation and reduced firing of SNc DA neurons. Regarding the transgene expressed, the A53T seems to be more effective than the A30P, in general.

Several viral vectors, primarily lentiviruses and adeno-associated viruses (AAVs), have been used to drive exogenous α-syn. Rats are usually used for these studies because viral vector delivery requires stereotactic injections within or near the site of the neuronal cell bodies in the SNc (Kirik et al., 2002; Klein et al., 2002; Lo Bianco et al., 2002; Lauwers et al., 2003, 2007). In contrast to all of the α-syn transgenic mice, viral vector-mediated α-syn models display α-syn pathology and clear dopaminergic neurodegeneration. The injection of human WT or A53T mutant α-syn by AAVs into the SNc neurons of rats induces a progressive, age-dependent loss of DA neurons, motor impairment, and α-syn cytoplasmic inclusions (Kirik et al., 2002; Klein et al., 2002; Lo Bianco et al., 2002; Decressac et al., 2012). This cell loss was preceded by degenerative changes in striatal axons and terminals, and the presence of α-syn positive inclusions in axons and dendrites (Kirik et al., 2003; Decressac et al., 2012). These results have been replicated in mice (Lauwers et al., 2003; Oliveras-Salvá et al., 2013). Although these models still suffer from a certain degree of variability, they can be of great value for further development and testing of neuroprotective strategies.

Recently, several studies have demonstrated that α-syn may be transmissible from cell to cell (Luk and Lee, 2014). In WT mice, a single intrastriatal inoculation of synthetic α-syn fibrils or pathological α-syn purified from postmortem PD brains led to the cell-to-cell transmission of pathologic α-syn and LB pathology in anatomically interconnected regions and was accompanied by a progressive loss of dopaminergic neurons in the SNc and reduced DA levels in the striatum, culminating in motor deficits (Luk et al., 2012a,b; Masuda-Suzukake et al., 2014; Recasens et al., 2014). Moreover, the hind limb intramuscular injection of α-syn can induce pathology in the central nervous system in transgenic mouse models (Sacino et al., 2014).

LRKK2

Mutations in LRRK2 are known to cause a late-onset autosomal dominant inherited form of PD (Healy et al., 2008). Several mutations have been identified in LRRK2, the most frequent being the G2019S mutation, a point mutation in the kinase domain, whereas R1441C, a mutation in the guanosine triphosphatase domain, is the second most common (Rudenko and Cookson, 2014). Overall, LRRK2 mice models display mild or not functional disruption of the nigrostriatal DA neurons of the SNc.

LRRK2 KO mice are viable and have an intact nigrostriatal DA pathway up to 2 years of age. Neuropathological features associated with neurodegeneration or altered neuronal structure were absent, but α-syn or ubiquitin accumulation has been reported in these mice (Andres-Mateos et al., 2009; Lin et al., 2009; Tong et al., 2010; Hinkle et al., 2012). To date, two LRRK2 KO rat models have been developed, although the consequences of LRRK2 deficiency in the brain are still unknown (Baptista et al., 2013; Ness et al., 2013).

Both G2019S and R1441C LRRK2 KI mice are viable, fertile, and appear grossly normal. This mutation had no impact on DA neuron number or morphology in the SNc, or on noradrenergic neurons in the LC. Striatal DA levels and DA turnover are also normal in these mice (Tong et al., 2009; Herzig et al., 2011).

Overexpression of G2019S LRRK2 leads to a mild progressive and selective degeneration of SNc DA neurons (20%) up to 2 years of age. Furthermore, no alteration in striatal DA levels or locomotor activity could be detected in older G2019S LRRK2 mice (Ramonet et al., 2011; Chen et al., 2012). Also, Maekawa et al. (2012) generated transgenic mice constitutively expressing V5-tagged human I2020T LRRK2 from a CMV promoter with no influence on SNc DA neuronal number or striatal DA fiber density. Zhou et al. (2011) developed a transgenic rat model expressing G2019S LRRK2. Despite a mild behavioral alteration, LRRK2 expression had no effect on the number of DA neurons or on striatal DA content. Recently, conditional expression of R1441C LRRK2 in midbrain dopaminergic neurons of mice results in nuclear abnormalities but, without neurodegeneration (Tsika et al., 2014).

Additional LRRK2 BAC transgenic mouse models have also been developed. These mice displayed age-dependent and progressive motor deficits at 10–12 months of age, accompanied by a mild reduction of striatal DA release. Adult neurogenesis and neurite outgrowth are impaired. No DA neurons loss or degeneration of striatal nerve terminals where observed in mice at 9–10 months of age (Li et al., 2009b, 2010; Melrose et al., 2010; Winner et al., 2011).

Regarding the viral vector-based models, Lee et al. (2010) developed a herpes simplex virus (HSV) amplicon-based mouse model of G2019S LRRK2-induced DA neurotoxicity. The nigrostriatal expression of WT LRRK2 induced modest nigral DA neurodegeneration (10–20%), whereas expression of the kinase-hyperactive G2019S LRRK2 resulted in a 50% neuronal loss in the ipsilateral SNc associated with reduced striatal DA fiber density at 3 weeks post-injection. In another study, a model based on the unilateral injection of recombinant, second-generation human serotype 5 adenoviral (rAd) vectors expressing FLAG-tagged human WT or G2019S LRRK2 driven by a neuronal-specific human synapsin-1 promoter in rats induced the progressive loss (20%) of DA neurons in the ipsilateral SNc over 42 days, but with no reduction of striatal DA fiber density (Dusonchet et al., 2011).

PINK1

Mutations in the gene PINK1 cause another form of PD called PARK6 (Scarffe et al., 2014). PINK1 KO mice have an age-dependent, moderate reduction in striatal DA levels accompanied by low locomotor activity, but do not exhibit major abnormalities in the DA neurons or striatal DA levels (Gautier et al., 2008; Gispert et al., 2009). These mice showed no LB formation or nigrostriatal degeneration for up to 18 months of age. However, in PINK1 KO mice, overexpression of α-syn in the SNc resulted in enhanced dopaminergic neuron degeneration as well as significantly higher levels of α-syn phosphorylation at serine 129 at 4 weeks post-injection (Oliveras-Salvá et al., 2014). Recently, a PINK1 null mouse with an exon 4–5 deletion displayed a progressive loss of DA in the striatum, but there was no degeneration in the SNc (Akundi et al., 2011). The phenotypes of these mice are very similar to those of Parkin KO and DJ-1 KO mice.

Parkin

Parkin is an E3 ubiquitin ligase that functions in the ubiquitin–proteasome system. Mutations in parkin are a cause of familial PD and are also seen in some young-onset sporadic PD cases (Lücking et al., 2000; Periquet et al., 2003). Several parkin KO mice have been generated, typically produced by deletion at exon 3, exon 7, or exon 2 in the PRKN gene (Goldberg et al., 2003; Itier et al., 2003; Palacino et al., 2004; Von Coelln et al., 2004; Perez and Palmiter, 2005; Zhu et al., 2007; Martella et al., 2009). However, they show no substantial DA-related behavioral abnormalities. Some of these KO mice exhibit slightly impaired DA release (Itier et al., 2003; Kitada et al., 2009a) and reduced norepinephrine levels in the olfactory bulb and spinal cord with an abnormal nigrostriatal region but without loss of SNc neurons (Goldberg et al., 2003; Von Coelln et al., 2004).

Only the Parkin-Q311X-DAT-BAC mice exhibit multiple late onsets and progressive hypokinetic motor deficits, age-dependent DA neuron degeneration in the SNc and a significant reduction in striatal DA and dopaminergic terminals in the striatum (Lu et al., 2009). Recently, overexpression of T240R-parkin and of human WT parkin induced progressive and dose-dependent DA cell death in rats (Van Rompuy et al., 2014).

DJ-1

DJ-1 mutations are linked to an autosomal recessive, early onset PD (Puschmann, 2013). KO models of DJ-1 mice with a targeted deletion of exon 2 or insertion of a premature stop codon in exon 1 show decreased locomotor activity, a reduction in the release of evoked DA in the striatum but no loss of SNc DA neurons and no change of the DA levels (Goldberg et al., 2005; Kim et al., 2005). However, one line of DJ-1 KO mice shows loss of DA neurons in the VTA (Pham et al., 2010).

Interestingly, a recently described DJ-1 KO mouse, backcrossed on a C57/BL6 background, displayed a dramatic early onset unilateral loss of DA neurons in the SNc, progressing to bilateral degeneration of the nigrostriatal axis, with aging. In addition, these mice exhibit age-dependent bilateral degeneration in the LC and display, with aging, a mild motor behavioral deficit at specific time points (Rousseaux et al., 2012). Therefore, if confirmed, this new mouse model would provide a tool to study the preclinical aspects of PD.

ATP13A2

Mutations in ATP13A2 (PARK9), encoding a lysosomal P-type ATPase, are associated with both Kufor–Rakeb syndrome (KRS) and neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. KRS has recently been classified as a rare genetic form of PD (Heinzen et al., 2014; Yang and Xu, 2014). Despite the accumulation of lipofuscin deposits in the SNc and late-onset sensorimotor deficits, there was no change in the number of DA neurons in the SNc or in striatal DA levels in aged Atp13a2 KO mice (Schultheis et al., 2013).

Other Models

Inactivation of multiple PD genes has been shown to be insufficient to cause significant nigral degeneration within the lifespan of mice (Hennis et al., 2014). Triple KO mice lacking Parkin, DJ-1, or PINK1 have normal morphology and normal numbers of dopaminergic and noradrenergic neurons in the SNc and LC. Also, levels of striatal DA in these triple KO mice were normal at 16 months, but increased at 24 months of age (Kitada et al., 2009b).

Sonic hedgehog (SHH), nuclear receptor related protein-1 (Nurr1), pituitary homeobox3 (Pitx3), and engrailed 1 (EN1) are transcription factors important to the development and maintenance of the nigro-striatal system (Jankovic et al., 2005; Jiang et al., 2005; Li et al., 2009a; Gonzalez-Reyes et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2012). Both SHH and Nurr1 KO mice show a progressive loss of DA neurons without LB formation (Jiang et al., 2005; Kadkhodaei et al., 2009; Gonzalez-Reyes et al., 2012). Also, Pitx3 gene mutations cause a complete loss of SNc and VTA DA neurons and altered locomotor activity in mice (Hwang et al., 2003; van den Munckhof et al., 2003). Recently, engrailed 1 heterozygous mice (En1+/–) showed a significant and progressive retrograde degeneration of SNc neurons and dystrophic and swollen striatal TH+ terminals (Nordström et al., 2014). c-Rel (a subunit of the NFκB complex) KO mice also develop a PD-like neuropathology on aging. At 18 months of age, c-rel (–/–) mice exhibit a significant loss of DA neurons in the SNc, loss of dopaminergic terminals and a significant reduction of DA and HVA levels in the striatum. In addition, these mice show age-dependent deficits in locomotor activity and a marked immunoreactivity for fibrillary α-syn in the SNc (Baiguera et al., 2012).

Conditional disruption of the gene for mitochondrial transcription factor A in DA neurons (MitoPark) results in a parkinsonism phenotype in mice that includes an adult-onset, slowly progressive impairment of motor function, DA neuron death, degeneration of nigrostriatal pathways and intraneuronal inclusions (Ekstrand et al., 2007; Good et al., 2011). Also, cell-specific deletion of the essential autophagy gene Atg7 in midbrain DA neurons causes DA neuron loss in the SNc at 9 months, accompanied by late-onset locomotor deficits. Atg7-deficient DA neurons in the midbrain also exhibit early dendritic and axonal dystrophy, reduced striatal DA content, and the formation of somatic and dendritic ubiquitinated inclusions (Friedman et al., 2012).

Recently, it has been suggested that a vesicular monoamine tranporter (VMAT2) defect may be an early abnormality promoting mechanisms leading to nigrostriatal DA neuron death in PD (Pifl et al., 2014). VMAT2-deficient mice display a progressive loss of nigral DA and LC cells, loss of striatal DA and α-syn accumulation (Taylor et al., 2011, 2014). Neuroprotection from MPTP toxicity in VMAT2-overexpressors and enhanced MPTP toxicity in VMAT2-KO mice suggest that interventions aimed at enhancing vesicular capacity may be of therapeutic benefit in PD (Takahashi et al., 1997; Lohr et al., 2014).

Concluding Remarks

Despite the significant contribution of all of these animal models to our understanding of PD, none of these models reproduce the human condition. If we consider toxic models, significant nigrostriatal degeneration is generally obtained with some motor deficits (particularly in MPTP-treated monkeys). Although no consistent LB-like formation is detected, this issue in the study of PD pathogenesis remains to be demonstrated. On the other hand, although transgenic models offer insights into the causes of PD pathogenesis or LB-like formation, the absence of consistent neuronal loss in the SNc remains a major limitation for these models. Another troubling observation in genetic models is the often inconsistent phenotypes among the lines with the same mutations. Whether or not this is related to an artifact of insertion of the transgene or to the actual genetic background, it would be advisable to test these in more than one line.

In addition to the classical motor abnormalities observed in PD, animal models are increasingly used to study non-motor symptoms (sleep disturbances, neuropsychiatric and cognitive deficits; Campos et al., 2013; Drui et al., 2014). Both toxin-based and genetic models are suitable for studying these non-motor symptoms that are increasingly recognized as relevant in disease-state (McDowell and Chesselet, 2012). Toxins-based models have been mostly used to seek the mechanisms involved in levodopa induced dyskinesias (LID) thus far (Morin et al., 2014). However, recently viral vector-mediated silencing of TH was used to induce striatal DA depletion without affecting the anatomical integrity of the presynaptic terminals and study LID (Ulusoy et al., 2010). And more recently, for the first time, a genetic mouse model overexpressing A53T α-syn in nigrostriatal and corticostriatal projection neurons shows involuntary movements and increased post-synaptic sensitivity to apomorphine (Brehm et al., 2014). It seems unlikely that a single model can fully recapitulate the complexity of the human disease. Future models should involve a combination of neurotoxin and genetic animal models in order to study the progressive neurodegeneration associated with PD. Understanding the mechanisms responsible for this progressive and intrinsic SNc neuronal loss is completely necessary at this point.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Jackson-Lewis for valuable comments and corrections on the manuscript. Javier Blesa was supported by a post-doctoral fellowship from the Spanish Ministry of Education and a post-doctoral fellowship from the Government of Navarra-Euraxess.

References

Akundi, R. S., Huang, Z., Eason, J., Pandya, J. D., Zhi, L., Cass, W. A.,et al. (2011). Increased mitochondrial calcium sensitivity and abnormal expression of innate immunity genes precede dopaminergic defects in Pink1-deficient mice. PLoS ONE 6:e16038. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016038

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Alam, M., Mayerhofer, A., and Schmidt, W. J. (2004). The neurobehavioral changes induced by bilateral rotenone lesion in medial forebrain bundle of rats are reversed by L-DOPA. Behav. Brain Res. 151, 117–124. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2003.08.014

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Andres-Mateos, E., Mejias, R., Sasaki, M., Li, X., Lin, B. M., Biskup, S.,et al. (2009). Unexpected lack of hypersensitivity in LRRK2 knock-out mice to MPTP (1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine). J. Neurosci. 29, 15846–15850. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4357-09.2009

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Andres-Mateos, E., Perier, C., Zhang, L., Blanchard-Fillion, B., Greco, T. M., Thomas, B.,et al. (2007). DJ-1 gene deletion reveals that DJ-1 is an atypical peroxiredoxin-like peroxidase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 14807–14812. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703219104

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Baiguera, C., Alghisi, M., Pinna, A., Bellucci, A., De Luca, M. A., Frau, L.,et al. (2012). Late-onset Parkinsonism in NFκB/c-Rel-deficient mice. Brain 135, 2750–2765. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws193

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Baptista, M. A. S., Dave, K. D., Frasier, M. A., Sherer, T. B., Greeley, M., Beck, M. J.,et al. (2013). Loss of leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) in rats leads to progressive abnormal phenotypes in peripheral organs. PLoS ONE 8:e80705. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080705

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bastías-Candia, S., Di Benedetto, M., D’Addario, C., Candeletti, S., and Romualdi, P. (2013). Combined exposure to agriculture pesticides, paraquat and maneb, induces alterations in the N/OFQ-NOPr and PDYN/KOPr systems in rats: relevance to sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Environ. Toxicol. doi: 10.1002/tox.21943 [Epub ahead of print].

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Berg, J., Roch, M., Altschüler, J., Winter, C., Schwerk, A., Kurtz, A.,et al. (2014). Human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells improve motor functions and are neuroprotective in the 6-hydroxydopamine-rat model for parkinson’s disease when cultured in monolayer cultures but suppress hippocampal neurogenesis and hippocampal memory functi. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. doi: 10.1007/s12015-014-9551-y [Epub ahead of print].

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Berry, C., La Vecchia, C., and Nicotera, P. (2010). Paraquat and Parkinson’s disease. Cell Death Differ. 17, 1115–1125. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.217

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Betarbet, R., Sherer, T. B., MacKenzie, G., Garcia-Osuna, M., Panov, A. V., and Greenamyre, J. T. (2000). Chronic systemic pesticide exposure reproduces features of Parkinson’s disease. Nat. Neurosci. 3, 1301–1306. doi: 10.1038/81834

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bezard, E., Imbert, C., Deloire, X., Bioulac, B., and Gross, C. E. (1997). A chronic MPTP model reproducing the slow evolution of Parkinson’s disease: evolution of motor symptoms in the monkey. Brain Res. 766, 107–112. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(97)00531-3

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Blandini, F., Armentero, M.-T., and Martignoni, E. (2008). The 6-hydroxydopamine model: news from the past. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 14(Suppl. 2), S124–S129. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2008.04.015

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Blesa, J., Juri, C., Collantes, M., Peñuelas, I., Prieto, E., Iglesias, E.,et al. (2010). Progression of dopaminergic depletion in a model of MPTP-induced Parkinsonism in non-human primates. An (18)F-DOPA and (11)C-DTBZ PET study. Neurobiol. Dis. 38, 456–463. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.03.006

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Blesa, J., Juri, C., Garcia-Cabezas, M. A., Adanez, R., Sanchez-Gonzalez, M. A., Cavada, C.,et al. (2011). Inter-hemispheric asymmetry of nigrostriatal dopaminergic lesion: a possible compensatory mechanism in Parkinson’s disease. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 5:92. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2011.00092

Blesa, J., Pifl, C., Sánchez-González, M. A., Juri, C., García-Cabezas, M. A., Adánez, R.,et al. (2012). The nigrostriatal system in the presymptomatic and symptomatic stages in the MPTP monkey model: a PET, histological and biochemical study. Neurobiol. Dis. 48, 79–91. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2012.05.018

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Brehm, N., Bez, F., Carlsson, T., Kern, B., Gispert, S., Auburger, G.,et al. (2014). A genetic mouse model of Parkinson’s disease shows involuntary movements and increased postsynaptic sensitivity to apomorphine. Mol. Neurobiol. doi: 10.1007/s12035-014-8911–8916 [Epub ahead of print].

Brichta, L., Greengard, P., and Flajolet, M. (2013). Advances in the pharmacological treatment of Parkinson’s disease: targeting neurotransmitter systems. Trends Neurosci. 36, 543–554. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2013.06.003

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Brooks, A. I., Chadwick, C. A., Gelbard, H. A., Cory-Slechta, D. A., and Federoff, H. J. (1999). Paraquat elicited neurobehavioral syndrome caused by dopaminergic neuron loss. Brain Res. 823, 1–10. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(98)01192-5

Cadet, J. L., Krasnova, I. N., Jayanthi, S., and Lyles, J. (2007). Neurotoxicity of substituted amphetamines: molecular and cellular mechanisms. Neurotox. Res. 11, 183–202. doi: 10.1007/BF03033567

Campos, F. L., Carvalho, M. M., Cristovão, A. C., Je, G., Baltazar, G., Salgado, A. J.,et al. (2013). Rodent models of Parkinson’s disease: beyond the motor symptomatology. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 7:175. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2013.00175

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Cannon, J. R., Tapias, V., Na, H. M., Honick, A. S., Drolet, R. E., and Greenamyre, J. T. (2009). A highly reproducible rotenone model of Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 34, 279–290.

Capela, J. P., Carmo, H., Remião, F., Bastos, M. L., Meisel, A., and Carvalho, F. (2009). Molecular and cellular mechanisms of ecstasy-induced neurotoxicity: an overview. Mol. Neurobiol. 39, 210–271. doi: 10.1007/s12035-009-8064–8061

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Chege, P. M., and McColl, G. (2014). Caenorhabditis elegans: a model to investigate oxidative stress and metal dyshomeostasis in Parkinson’s disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 6:89. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2014.00089

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Chen, C.-Y., Weng, Y.-H., Chien, K.-Y., Lin, K.-J., Yeh, T.-H., Cheng, Y.-P.,et al. (2012). (G2019S) LRRK2 activates MKK4-JNK pathway and causes degeneration of SN dopaminergic neurons in a transgenic mouse model of PD. Cell Death Differ. 19, 1623–1633. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2012.42

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Chen, L., Thiruchelvam, M. J., Madura, K., and Richfield, E. K. (2006). Proteasome dysfunction in aged human alpha-synuclein transgenic mice. Neurobiol. Dis. 23, 120–126. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.02.004

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Chiueh, C. C., Markey, S. P., Burns, R. S., Johannessen, J. N., Jacobowitz, D. M., and Kopin, I. J. (1984). Neurochemical and behavioral effects of 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6- tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) in rat, guinea pig, and monkey. Psychopharmacol. Bull. 20, 548–553.

Costa, G., Frau, L., Wardas, J., Pinna, A., Plumitallo, A., and Morelli, M. (2013). MPTP-induced dopamine neuron degeneration and glia activation is potentiated in MDMA-pretreated mice. Mov. Disord. 28, 1957–1965. doi: 10.1002/mds.25646

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Dantuma, N. P., and Bott, L. C. (2014). The ubiquitin-proteasome system in neurodegenerative diseases: precipitating factor, yet part of the solution. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 7:70. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2014.00070

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Dauer, W., Kholodilov, N., Vila, M., Trillat, A.-C. C., Goodchild, R., Larsen, K. E.,et al. (2002). Resistance of alpha -synuclein null mice to the parkinsonian neurotoxin MPTP. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 14524–14529. doi: 10.1073/pnas.172514599

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Dauer, W., and Przedborski, S. (2003). Parkinson’s disease: mechanisms and models. Neuron 39, 889–909. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00568-3

Dawson, T. M., Ko, H. S., and Dawson, V. L. (2010). Genetic animal models of Parkinson’s disease. Neuron 66, 646–661. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.04.034

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Day, B. J., Patel, M., Calavetta, L., Chang, L. Y., and Stamler, J. S. (1999). A mechanism of paraquat toxicity involving nitric oxide synthase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 12760–12765. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12760

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Decressac, M., Mattsson, B., Lundblad, M., Weikop, P., and Björklund, A. (2012). Progressive neurodegenerative and behavioural changes induced by AAV-mediated overexpression of α-synuclein in midbrain dopamine neurons. Neurobiol. Dis. 45, 939–953. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.12.013

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Dong, Z., Ferger, B., Feldon, J., and Büeler, H. (2002). Overexpression of Parkinson’s disease-associated alpha-synucleinA53T by recombinant adeno-associated virus in mice does not increase the vulnerability of dopaminergic neurons to MPTP. J. Neurobiol. 53, 1–10. doi: 10.1002/neu.10094

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Drui, G., Carnicella, S., Carcenac, C., Favier, M., Bertrand, A., Boulet, S.,et al. (2014). Loss of dopaminergic nigrostriatal neurons accounts for the motivational and affective deficits in Parkinson’s disease. Mol. Psychiatry 19, 358–367. doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.3

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Dunnett, S. B., and Lelos, M. (2010). Behavioral analysis of motor and non-motor symptoms in rodent models of Parkinson’s disease. Prog. Brain Res. 184, 35–51. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(10)840038

Dusonchet, J., Kochubey, O., Stafa, K., Young, S. M., Zufferey, R., Moore, D. J.,et al. (2011). A rat model of progressive nigral neurodegeneration induced by the Parkinson’s disease-associated G2019S mutation in LRRK2. J. Neurosci. 31, 907–912. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5092-10.2011

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ekstrand, M. I., Terzioglu, M., Galter, D., Zhu, S., Hofstetter, C., Lindqvist, E.,et al. (2007). Progressive parkinsonism in mice with respiratory-chain-deficient dopamine neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 1325–1330. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605208103

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

El Ayadi, A., and Zigmond, M. J. (2011). Low concentrations of methamphetamine can protect dopaminergic cells against a larger oxidative stress injury: mechanistic study. PLoS ONE 6:e24722. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024722

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Exner, N., Lutz, A. K., Haass, C., and Winklhofer, K. F. (2012). Mitochondrial dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease: molecular mechanisms and pathophysiological consequences. EMBO J. 31, 3038–3062. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.170

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Fleming, S. M., Zhu, C., Fernagut, P.-O., Mehta, A., DiCarlo, C. D., Seaman, R. L.,et al. (2004). Behavioral and immunohistochemical effects of chronic intravenous and subcutaneous infusions of varying doses of rotenone. Exp. Neurol. 187, 418–429. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.01.023

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Forno, L. S., Langston, J. W., DeLanney, L. E., Irwin, I., and Ricaurte, G. A. (1986). Locus ceruleus lesions and eosinophilic inclusions in MPTP-treated monkeys. Ann. Neurol. 20, 449–455. doi: 10.1002/ana.410200403

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Freire, C., and Koifman, S. (2012). Pesticide exposure and Parkinson’s disease: epidemiological evidence of association. Neurotoxicology 33, 947–971. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2012.05.011

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Friedman, L. G., Lachenmayer, M. L., Wang, J., He, L., Poulose, S. M., Komatsu, M.,et al. (2012). Disrupted autophagy leads to dopaminergic axon and dendrite degeneration and promotes presynaptic accumulation of α-synuclein and LRRK2 in the brain. J. Neurosci. 32, 7585–7593. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5809-11.2012

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Gandhi, S., Wood-Kaczmar, A., Yao, Z., Plun-Favreau, H., Deas, E., Klupsch, K.,et al. (2009). PINK1-associated Parkinson’s disease is caused by neuronal vulnerability to calcium-induced cell death. Mol. Cell 33, 627–638. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.02.013

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Gautier, C. A., Kitada, T., and Shen, J. (2008). Loss of PINK1 causes mitochondrial functional defects and increased sensitivity to oxidative stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 11364–11369. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802076105

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Giasson, B. I., Duda, J. E., Quinn, S. M., Zhang, B., Trojanowski, J. Q., and Lee, V. M. (2002). Neuronal alpha-synucleinopathy with severe movement disorder in mice expressing A53T human alpha-synuclein. Neuron 34, 521–533. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(02)00682-7

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Gispert, S., Del Turco, D., Garrett, L., Chen, A., Bernard, D. J., Hamm-Clement, J.,et al. (2003). Transgenic mice expressing mutant A53T human alpha-synuclein show neuronal dysfunction in the absence of aggregate formation. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 24, 419–429. doi: 10.1016/S1044-7431(03)00198-2

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Gispert, S., Ricciardi, F., Kurz, A., Azizov, M., Hoepken, H.-H., Becker, D.,et al. (2009). Parkinson phenotype in aged PINK1-deficient mice is accompanied by progressive mitochondrial dysfunction in absence of neurodegeneration. PLoS ONE 4:e5777. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005777

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Glajch, K. E., Fleming, S. M., Surmeier, D. J., and Osten, P. (2012). Sensorimotor assessment of the unilateral 6-hydroxydopamine mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Behav. Brain Res. 230, 309–316. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.12.007

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Goedert, M., Spillantini, M. G., Del Tredici, K., and Braak, H. (2013). 100 years of Lewy pathology. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 9, 13–24. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2012.242

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Goldberg, M. S., Fleming, S. M., Palacino, J. J., Cepeda, C., Lam, H. A., Bhatnagar, A.,et al. (2003). Parkin-deficient mice exhibit nigrostriatal deficits but not loss of dopaminergic neurons. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 43628–43635. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308947200

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Goldberg, M. S., Pisani, A., Haburcak, M., Vortherms, T. A., Kitada, T., Costa, C.,et al. (2005). Nigrostriatal dopaminergic deficits and hypokinesia caused by inactivation of the familial Parkinsonism-linked gene DJ-1. Neuron 45, 489–496. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.01.041

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Gomez-Isla, T., Irizarry, M. C., Mariash, A., Cheung, B., Soto, O., Schrump, S.,et al. (2003). Motor dysfunction and gliosis with preserved dopaminergic markers in human alpha-synuclein A30P transgenic mice. Neurobiol. Aging 24, 245–258. doi: 10.1016/S0197-4580(02)00091-X

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Gonzalez-Reyes, L. E., Verbitsky, M., Blesa, J., Jackson-Lewis, V., Paredes, D., Tillack, K.,et al. (2012). Sonic hedgehog maintains cellular and neurochemical homeostasis in the adult nigrostriatal circuit. Neuron 75, 306–319. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.05.018

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Good, C. H., Hoffman, A. F., Hoffer, B. J., Chefer, V. I., Shippenberg, T. S., Bäckman, C. M.,et al. (2011). Impaired nigrostriatal function precedes behavioral deficits in a genetic mitochondrial model of Parkinson’s disease. FASEB J. 25, 1333–1344. doi: 10.1096/fj.10–173625

Granado, N., Escobedo, I., O’Shea, E., Colado, I., and Moratalla, R. (2008a). Early loss of dopaminergic terminals in striosomes after MDMA administration to mice. Synapse 62, 80–84. doi: 10.1002/syn.20466

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Granado, N., O’Shea, E., Bove, J., Vila, M., Colado, M. I., and Moratalla, R. (2008b). Persistent MDMA-induced dopaminergic neurotoxicity in the striatum and substantia nigra of mice. J. Neurochem. 107, 1102–1112. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05705.x

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Guo, M. (2012). Drosophila as a model to study mitochondrial dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2, pii:a009944. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a009944

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Halliday, G., Herrero, M. T., Murphy, K., McCann, H., Ros-Bernal, F., Barcia, C.,et al. (2009). No Lewy pathology in monkeys with over 10 years of severe MPTP Parkinsonism. Mov. Disord. 24, 1519–1523. doi: 10.1002/mds.22481

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Haque, M. E., Mount, M. P., Safarpour, F., Abdel-Messih, E., Callaghan, S., Mazerolle, C.,et al. (2012). Inactivation of Pink1 gene in vivo sensitizes dopamine-producing neurons to 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) and can be rescued by autosomal recessive Parkinson disease genes, Parkin or DJ-1. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 23162–23170. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.346437

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Healy, D. G., Falchi, M., O’Sullivan, S. S., Bonifati, V., Durr, A., Bressman, S.,et al. (2008). Phenotype, genotype, and worldwide genetic penetrance of LRRK2-associated Parkinson’s disease: a case-control study. Lancet. Neurol. 7, 583–590. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70117–70110

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Heinzen, E. L., Arzimanoglou, A., Brashear, A., Clapcote, S. J., Gurrieri, F., Goldstein, D. B.,et al. (2014). Distinct neurological disorders with ATP1A3 mutations. Lancet. Neurol. 13, 503–514. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70011–70010

Hennis, M. R., Marvin, M. A., Taylor, C. M., and Goldberg, M. S. (2014). Surprising behavioral and neurochemical enhancements in mice with combined mutations linked to Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 62, 113–123. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2013.09.009

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Hennis, M. R., Seamans, K. W., Marvin, M. A., Casey, B. H., and Goldberg, M. S. (2013). Behavioral and neurotransmitter abnormalities in mice deficient for Parkin, DJ-1 and superoxide dismutase. PLoS ONE 8:e84894. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084894

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Herzig, M. C., Kolly, C., Persohn, E., Theil, D., Schweizer, T., Hafner, T.,et al. (2011). LRRK2 protein levels are determined by kinase function and are crucial for kidney and lung homeostasis in mice. Hum. Mol. Genet. 20, 4209–4223. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr348

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Hess, A., Desiderio, C., and McAuliffe, W. G. (1990). Acute neuropathological changes in the caudate nucleus caused by MPTP and methamphetamine: immunohistochemical studies. J. Neurocytol. 19, 338–342. doi: 10.1007/BF01188403

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Hinkle, K. M., Yue, M., Behrouz, B., Dächsel, J. C., Lincoln, S. J., Bowles, E. E.,et al. (2012). LRRK2 knockout mice have an intact dopaminergic system but display alterations in exploratory and motor co-ordination behaviors. Mol. Neurodegener. 7:25. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-725

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Howard, C. D., Keefe, K. A., Garris, P. A., and Daberkow, D. P. (2011). Methamphetamine neurotoxicity decreases phasic, but not tonic, dopaminergic signaling in the rat striatum. J. Neurochem. 118, 668–676. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07342.x

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Hwang, D.-Y., Ardayfio, P., Kang, U. J., Semina, E. V, and Kim, K.-S. (2003). Selective loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra of Pitx3-deficient aphakia mice. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 114, 123–131. doi: 10.1016/S0169-328X(03)00162-1

Ikeda, M., Kawarabayashi, T., Harigaya, Y., Sasaki, A., Yamada, S., Matsubara, E.,et al. (2009). Motor impairment and aberrant production of neurochemicals in human alpha-synuclein A30P+A53T transgenic mice with alpha-synuclein pathology. Brain Res. 1250, 232–241. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.10.011

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Itier, J.-M., Ibanez, P., Mena, M. A., Abbas, N., Cohen-Salmon, C., Bohme, G. A.,et al. (2003). Parkin gene inactivation alters behaviour and dopamine neurotransmission in the mouse. Hum. Mol. Genet. 12, 2277–2291. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg239

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Jackson-Lewis, V., and Przedborski, S. (2007). Protocol for the MPTP mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Nat. Protoc. 2, 141–151. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.342

Janezic, S., Threlfell, S., Dodson, P. D., Dowie, M. J., Taylor, T. N., Potgieter, D.,et al. (2013). Deficits in dopaminergic transmission precede neuron loss and dysfunction in a new Parkinson model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, E4016–E4025. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1309143110

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Jankovic, J., Chen, S., and Le, W. D. (2005). The role of Nurr1 in the development of dopaminergic neurons and Parkinson’s disease. Prog. Neurobiol. 77, 128–138. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2005.09.001

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Jensen, K. F., Olin, J., Haykal-Coates, N., O’Callaghan, J., Miller, D. B., and de Olmos, J. S. (1993). Mapping toxicant-induced nervous system damage with a cupric silver stain: a quantitative analysis of neural degeneration induced by 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine. NIDA Res. Monogr. 136, 133–149; discussion 150–154.

Jiang, C., Wan, X., He, Y., Pan, T., Jankovic, J., and Le, W. (2005). Age-dependent dopaminergic dysfunction in Nurr1 knockout mice. Exp. Neurol. 191, 154–162. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.08.035

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Joselin, A. P., Hewitt, S. J., Callaghan, S. M., Kim, R. H., Chung, Y.-H., Mak, T. W.,et al. (2012). ROS-dependent regulation of Parkin and DJ-1 localization during oxidative stress in neurons. Hum. Mol. Genet. 21, 4888–4903. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds325

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kadkhodaei, B., Ito, T., Joodmardi, E., Mattsson, B., Rouillard, C., Carta, M.,et al. (2009). Nurr1 is required for maintenance of maturing and adult midbrain dopamine neurons. J. Neurosci. 29, 15923–15932. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3910-09.2009

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kara, E., Kiely, A. P., Proukakis, C., Giffin, N., Love, S., Hehir, J.,et al. (2014). A 6.4 Mb duplication of the α-synuclein locus causing frontotemporal dementia and parkinsonism: phenotype-genotype correlations. JAMA Neurol. 71, 1162–1171. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.994

Kim, R. H., Smith, P. D., Aleyasin, H., Hayley, S., Mount, M. P., Pownall, S.,et al. (2005). Hypersensitivity of DJ-1-deficient mice to 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyrindine (MPTP) and oxidative stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 5215–5220. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501282102

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kirik, D., Annett, L. E., Burger, C., Muzyczka, N., Mandel, R. J., and Björklund, A. (2003). Nigrostriatal alpha-synucleinopathy induced by viral vector-mediated overexpression of human alpha-synuclein: a new primate model of Parkinson’s disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 2884–2889. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0536383100

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kirik, D., Rosenblad, C., Burger, C., Lundberg, C., Johansen, T. E., Muzyczka, N.,et al. (2002). Parkinson-like neurodegeneration induced by targeted overexpression of alpha-synuclein in the nigrostriatal system. J. Neurosci. 22, 2780–2791.

Kitada, T., Pisani, A., Karouani, M., Haburcak, M., Martella, G., Tscherter, A.,et al. (2009a). Impaired dopamine release and synaptic plasticity in the striatum of parkin-/- mice. J. Neurochem. 110, 613–621. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06152.x

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kitada, T., Tong, Y., Gautier, C. A., and Shen, J. (2009b). Absence of nigral degeneration in aged parkin/DJ-1/PINK1 triple knockout mice. J. Neurochem. 111, 696–702. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06350.x

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Klein, R. L., King, M. A., Hamby, M. E., and Meyer, E. M. (2002). Dopaminergic cell loss induced by human A30P alpha-synuclein gene transfer to the rat substantia nigra. Hum. Gene Ther. 13, 605–612. doi: 10.1089/10430340252837206

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kogan, F. J., Nichols, W. K., and Gibb, J. W. (1976). Influence of methamphetamine on nigral and striatal tyrosine hydroxylase activity and on striatal dopamine levels. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 36, 363–371. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(76)90090-X

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kowall, N. W., Hantraye, P., Brouillet, E., Beal, M. F., McKee, A. C., and Ferrante, R. J. (2000). MPTP induces alpha-synuclein aggregation in the substantia nigra of baboons. Neuroreport 11, 211–213.

Lachenmayer, M. L., and Yue, Z. (2012). Genetic animal models for evaluating the role of autophagy in etiopathogenesis of Parkinson disease. Autophagy 8, 1837–1838. doi: 10.4161/auto.21859

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lam, H. A., Wu, N., Cely, I., Kelly, R. L., Hean, S., Richter, F.,et al. (2011). Elevated tonic extracellular dopamine concentration and altered dopamine modulation of synaptic activity precede dopamine loss in the striatum of mice overexpressing human α-synuclein. J. Neurosci. Res. 89, 1091–1102. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22611

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Langston, J. W., Ballard, P., Tetrud, J. W., and Irwin, I. (1983). Chronic Parkinsonism in humans due to a product of meperidine-analog synthesis. Science 219, 979–980. doi: 10.1126/science.6823561

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lauwers, E., Bequé, D., Van Laere, K., Nuyts, J., Bormans, G., Mortelmans, L.,et al. (2007). Non-invasive imaging of neuropathology in a rat model of alpha-synuclein overexpression. Neurobiol. Aging 28, 248–257. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.12.005

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lauwers, E., Debyser, Z., Van Dorpe, J., De Strooper, B., Nuttin, B., and Baekelandt, V. (2003). Neuropathology and neurodegeneration in rodent brain induced by lentiviral vector-mediated overexpression of alpha-synuclein. Brain Pathol. 13, 364–372. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2003.tb00035.x

Lee, B. D., Shin, J.-H., VanKampen, J., Petrucelli, L., West, A. B., Ko, H. S.,et al. (2010). Inhibitors of leucine-rich repeat kinase-2 protect against models of Parkinson’s disease. Nat. Med. 16, 998–1000. doi: 10.1038/nm.2199

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Li, J., Dani, J. A., and Le, W. (2009a). The role of transcription factor Pitx3 in dopamine neuron development and Parkinson’s disease. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 9, 855–859.

Li, Y., Liu, W., Oo, T. F., Wang, L., Tang, Y., Jackson-Lewis, V.,et al. (2009b). Mutant LRRK2(R1441G) BAC transgenic mice recapitulate cardinal features of Parkinson’s disease. Nat. Neurosci. 12, 826–828. doi: 10.1038/nn.2349

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Li, X., Patel, J. C., Wang, J., Avshalumov, M. V., Nicholson, C., Buxbaum, J. D.,et al. (2010). Enhanced striatal dopamine transmission and motor performance with LRRK2 overexpression in mice is eliminated by familial Parkinson’s disease mutation G2019S. J. Neurosci. 30, 1788–1797. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5604-09.2010

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lin, X., Parisiadou, L., Gu, X.-L., Wang, L., Shim, H., Sun, L.,et al. (2009). Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 regulates the progression of neuropathology induced by Parkinson’s-disease-related mutant alpha-synuclein. Neuron 64, 807–827. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.11.006

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lin, X., Parisiadou, L., Sgobio, C., Liu, G., Yu, J., Sun, L.,et al. (2012). Conditional expression of Parkinson’s disease-related mutant α-synuclein in the midbrain dopaminergic neurons causes progressive neurodegeneration and degradation of transcription factor nuclear receptor related 1. J. Neurosci. 32, 9248–9264. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1731-12.2012

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lo Bianco, C., Ridet, J.-L., Schneider, B. L., Deglon, N., and Aebischer, P. (2002). alpha -Synucleinopathy and selective dopaminergic neuron loss in a rat lentiviral-based model of Parkinson’s disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 10813–10818. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152339799

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lohr, K. M., Bernstein, A. I., Stout, K. A., Dunn, A. R., Lazo, C. R., Alter, S. P.,et al. (2014). Increased vesicular monoamine transporter enhances dopamine release and opposes Parkinson disease-related neurodegeneration in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 9977–9982. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1402134111

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lu, X.-H., Fleming, S. M., Meurers, B., Ackerson, L. C., Mortazavi, F., Lo, V.,et al. (2009). Bacterial artificial chromosome transgenic mice expressing a truncated mutant parkin exhibit age-dependent hypokinetic motor deficits, dopaminergic neuron degeneration, and accumulation of proteinase K-resistant alpha-synuclein. J. Neurosci. 29, 1962–1976. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5351-08.2009

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lücking, C. B., Dürr, A., Bonifati, V., Vaughan, J., De Michele, G., Gasser, T.,et al. (2000). Association between early-onset Parkinson’s disease and mutations in the parkin gene. N. Engl. J. Med. 342, 1560–1567. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005253422103

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Luk, K. C., Kehm, V., Carroll, J., Zhang, B., O’Brien, P., Trojanowski, J. Q.,et al. (2012a). Pathological α-synuclein transmission initiates Parkinson-like neurodegeneration in nontransgenic mice. Science 338, 949–953. doi: 10.1126/science.1227157

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Luk, K. C., Kehm, V. M., Zhang, B., O’Brien, P., Trojanowski, J. Q., and Lee, V. M. Y. (2012b). Intracerebral inoculation of pathological α-synuclein initiates a rapidly progressive neurodegenerative α-synucleinopathy in mice. J. Exp. Med. 209, 975–986. doi: 10.1084/jem.20112457

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Luk, K. C., and Lee, V. M.-Y. (2014). Modeling Lewy pathology propagation in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 20(Suppl. 1), S85–S87. doi: 10.1016/S1353-8020(13)70022–70021

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Maekawa, T., Mori, S., Sasaki, Y., Miyajima, T., Azuma, S., Ohta, E.,et al. (2012). The I2020T Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 transgenic mouse exhibits impaired locomotive ability accompanied by dopaminergic neuron abnormalities. Mol. Neurodegener. 7, 15. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-715

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Manning-Bog, A. B., McCormack, A. L., Li, J., Uversky, V. N., Fink, A. L., and Di Monte, D. A. (2002). The herbicide paraquat causes up-regulation and aggregation of alpha-synuclein in mice: paraquat and alpha-synuclein. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 1641–1644. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100560200

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Martella, G., Platania, P., Vita, D., Sciamanna, G., Cuomo, D., Tassone, A.,et al. (2009). Enhanced sensitivity to group II mGlu receptor activation at corticostriatal synapses in mice lacking the familial parkinsonism-linked genes PINK1 or Parkin. Exp. Neurol. 215, 388–396. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.11.001

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Masliah, E., Rockenstein, E., Veinbergs, I., Mallory, M., Hashimoto, M., Takeda, A.,et al. (2000). Dopaminergic loss and inclusion body formation in alpha-synuclein mice: implications for neurodegenerative disorders. Science 287, 1265–1269. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5456.1265

Masuda-Suzukake, M., Nonaka, T., Hosokawa, M., Kubo, M., Shimozawa, A., Akiyama, H.,et al. (2014). Pathological alpha-synuclein propagates through neural networks. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2, 88. doi: 10.1186/PREACCEPT-1296467154135944

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Matsui, H., Uemura, N., Yamakado, H., Takeda, S., and Takahashi, R. (2014). Exploring the pathogenetic mechanisms underlying Parkinson’s disease in medaka fish. J. Parkinsons. Dis. 4, 301–310. doi: 10.3233/JPD-130289

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Matsuoka, Y., Vila, M., Lincoln, S., McCormack, A., Picciano, M., LaFrancois, J.,et al. (2001). Lack of nigral pathology in transgenic mice expressing human alpha-synuclein driven by the tyrosine hydroxylase promoter. Neurobiol. Dis. 8, 535–539. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2001.0392

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

McCormack, A. L., Thiruchelvam, M., Manning-Bog, A. B., Thiffault, C., Langston, J. W., Cory-Slechta, D. A.,et al. (2002). Environmental risk factors and Parkinson’s disease: selective degeneration of nigral dopaminergic neurons caused by the herbicide paraquat. Neurobiol. Dis. 10, 119–127. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2002.0507

McDowell, K., and Chesselet, M.-F. (2012). Animal models of the non-motor features of Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 46, 597–606. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.12.040

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Melrose, H. L., Dächsel, J. C., Behrouz, B., Lincoln, S. J., Yue, M., Hinkle, K. M.,et al. (2010). Impaired dopaminergic neurotransmission and microtubule-associated protein tau alterations in human LRRK2 transgenic mice. Neurobiol. Dis. 40, 503–517. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.07.010

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Meredith, G. E., Totterdell, S., Potashkin, J. A., and Surmeier, D. J. (2008). Modeling PD pathogenesis in mice: advantages of a chronic MPTP protocol. Park. Relat Disord 14(Suppl. 2), S112–S115. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2008.04.012

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Miller, G. W. (2007). Paraquat: the red herring of Parkinson’s disease research. Toxicol. Sci. 100, 1–2. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfm223

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Miller, R. M., Kiser, G. L., Kaysser-Kranich, T., Casaceli, C., Colla, E., Lee, M. K.,et al. (2007). Wild-type and mutant alpha-synuclein induce a multi-component gene expression profile consistent with shared pathophysiology in different transgenic mouse models of PD. Exp. Neurol. 204, 421–432. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.12.005

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Morais, V. A., Haddad, D., Craessaerts, K., De Bock, P.-J., Swerts, J., Vilain, S.,et al. (2014). PINK1 loss-of-function mutations affect mitochondrial complex I activity via NdufA10 ubiquinone uncoupling. Science 344, 203–207. doi: 10.1126/science.1249161

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Moratalla, R., Quinn, B., DeLanney, L. E., Irwin, I., Langston, J. W., and Graybiel, A. M. (1992). Differential vulnerability of primate caudate-putamen and striosome-matrix dopamine systems to the neurotoxic effects of 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89, 3859–3863. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.9.3859

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Morin, N., Jourdain, V. A., and Di Paolo, T. (2014). Modeling dyskinesia in animal models of Parkinson disease. Exp. Neurol. 256, 105–116. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2013.01.024

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Morrow, B. A., Roth, R. H., Redmond, D. E., and Elsworth, J. D. (2011). Impact of methamphetamine on dopamine neurons in primates is dependent on age: implications for development of Parkinson’s disease. Neuroscience 189, 277–285. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.05.046

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Muthane, U., Ramsay, K. A., Jiang, H., Jackson-Lewis, V., Donaldson, D., Fernando, S.,et al. (1994). Differences in nigral neuron number and sensitivity to 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine in C57/bl and CD-1 mice. Exp. Neurol. 126, 195–204. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1994.1058

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ness, D., Ren, Z., Gardai, S., Sharpnack, D., Johnson, V. J., Brennan, R. J.,et al. (2013). Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2)-deficient rats exhibit renal tubule injury and perturbations in metabolic and immunological homeostasis. PLoS ONE 8:e66164. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066164

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Nieto, M., Gil-Bea, F. J., Dalfó, E., Cuadrado, M., Cabodevilla, F., Sánchez, B.,et al. (2006). Increased sensitivity to MPTP in human alpha-synuclein A30P transgenic mice. Neurobiol. Aging 27, 848–856. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.04.010

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Nordström, U., Beauvais, G., Ghosh, A., Sasidharan, B. C. P., Lundblad, M., Fuchs, J.,et al. (2014). Progressive nigrostriatal terminal dysfunction and degeneration in the engrailed1 heterozygous mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol. Dis. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2014.09.012

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Oaks, A. W., Frankfurt, M., Finkelstein, D. I., and Sidhu, A. (2013). Age-dependent effects of A53T alpha-synuclein on behavior and dopaminergic function. PLoS ONE 8:e60378. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060378

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Obeso, J. A., Rodriguez-Oroz, M. C., Stamelou, M., Bhatia, K. P., and Burn, D. J. (2014). The expanding universe of disorders of the basal ganglia. Lancet 384, 523–531. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62418–62416

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

O’Callaghan, J. P., and Miller, D. B. (1994). Neurotoxicity profiles of substituted amphetamines in the C57BL/6J mouse. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 270, 741–751.

Oliveras-Salvá, M., Macchi, F., Coessens, V., Deleersnijder, A., Gérard, M., Van der Perren, A.,et al. (2014). Alpha-synuclein-induced neurodegeneration is exacerbated in PINK1 knockout mice. Neurobiol. Aging 35, 2625–2636. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.04.032

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Oliveras-Salvá, M., Van der Perren, A., Casadei, N., Stroobants, S., Nuber, S., D’Hooge, R.,et al. (2013). rAAV2/7 vector-mediated overexpression of alpha-synuclein in mouse substantia nigra induces protein aggregation and progressive dose-dependent neurodegeneration. Mol. Neurodegener. 8, 44. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-8-44

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ono, K., Ikemoto, M., Kawarabayashi, T., Ikeda, M., Nishinakagawa, T., Hosokawa, M.,et al. (2009). A chemical chaperone, sodium 4-phenylbutyric acid, attenuates the pathogenic potency in human alpha-synuclein A30P + A53T transgenic mice. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 15, 649–654. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2009.03.002

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ottolini, D., Calì, T., Negro, A., and Brini, M. (2013). The Parkinson disease-related protein DJ-1 counteracts mitochondrial impairment induced by the tumour suppressor protein p53 by enhancing endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria tethering. Hum. Mol. Genet. 22, 2152–2168. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt068

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Palacino, J. J., Sagi, D., Goldberg, M. S., Krauss, S., Motz, C., Wacker, M.,et al. (2004). Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative damage in parkin-deficient mice. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 18614–18622. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401135200

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Pan-Montojo, F., Anichtchik, O., Dening, Y., Knels, L., Pursche, S., Jung, R.,et al. (2010). Progression of Parkinson’s disease pathology is reproduced by intragastric administration of rotenone in mice. PLoS ONE 5:e8762. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008762

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Paumier, K. L., Sukoff Rizzo, S. J., Berger, Z., Chen, Y., Gonzales, C., Kaftan, E.,et al. (2013). Behavioral characterization of A53T mice reveals early and late stage deficits related to Parkinson’s disease. PLoS ONE 8:e70274. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070274

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Perez, F. A., and Palmiter, R. D. (2005). Parkin-deficient mice are not a robust model of parkinsonism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 2174–2179. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409598102

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Periquet, M., Latouche, M., Lohmann, E., Rawal, N., De Michele, G., Ricard, S.,et al. (2003). Parkin mutations are frequent in patients with isolated early-onset parkinsonism. Brain 126, 1271–1278. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg136

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Pham, T. T., Giesert, F., Röthig, A., Floss, T., Kallnik, M., Weindl, K.,et al. (2010). DJ-1-deficient mice show less TH-positive neurons in the ventral tegmental area and exhibit non-motoric behavioural impairments. Genes Brain Behav. 9, 305–317. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2009.00559.x

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar