94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Front. Aging Neurosci., 26 February 2025

Sec. Parkinson’s Disease and Aging-related Movement Disorders

Volume 17 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2025.1496112

This article is part of the Research TopicMultifactorial balance assessment, falls prevention and rehabilitationView all 9 articles

Objective: Gait disorder represents a characteristic symptom of Parkinson’s disease (PD), and exercise has been established as an effective intervention for gait management in PD. However, the relative efficacy of various exercise types in improving gait among PD patients remains unclear. This study aimed to compare the effectiveness of different movement-based interventions in enhancing gait for individuals with PD through a network meta-analysis.

Methods: A comprehensive search was conducted across multiple databases, including PubMed, Cochrane Library, Embase, Web of Science, and CNKI. The methodological quality of included studies was evaluated using the Cochrane Bias risk tool. Data was extracted from these studies to compare the efficacy of 29 distinct exercise interventions on gait performance in patients with PD.

Results: The analysis encompassed 68 randomized controlled trials (RCTs), involving a total of 3,114 participants. The results of the network meta-analysis showed that DE is higher than CON (SMD, 2.11; 95% CI 1.07 to 3.15), WE (SMD, 2.16; 95% CI 0.90 to 3.43), HE (SMD, 2.19; 95% CI 0.95 to 3.44), OE (SMD, 2.66; 95% CI 1.16 to 4.16), TR (SMD, 2.62; 95% CI 1.45 to 3.79) to better improve Gait velocity in patients with Parkinson’s disease. DE is superior to CON (SMD, 2.08; 95% CI 0.04 to 4.13) in improving Step length. FAE is superior to CON (SMD, 1.01; 95% CI 0.04 to 1.98), BDJ (SMD, 1.20; 95% CI 0.15 to 2.25), RAGT (SMD, 1.29; 95% CI 0.07 to 2.52), DE (SMD, 1.57; 95% CI 0.36 to 2.77), TR (SMD, 1.62; 95% CI 0.48 to 2.76), OE (1.76, 95% CI 0.57 to 2.94) in improving Gait velocity. RAGT is superior to CT (MD, 2.02; 95% CI 0.41 to 3.63), TR (MD, 2.51; 95% CI 1.17 to 3.84), AE (MD, 2.66; 95% CI 0.45 to 4.88), BDJ (MD, 2.77; 95% CI 0.93 to 4.61), CON (MD, 2.83; 95% CI 1.30 to 4.36), DTT (MD, 12.84; 95% CI 10.05 to 15.63) in improving 6MWT.

Conclusion: Our study found that DE improved gait speed and step length in patients with Parkinson’s disease better than other forms of exercise. FAE and RAGT were more effective than other exercises in improving step length and 6MWT in patients with Parkinson’s disease.

PD is the second most prevalent neurodegenerative disorder characterized by motor activity deterioration, resulting from damage to the dopaminergic nigrostriatal system (Pajares et al., 2020; Simon et al., 2020). The incidence of PD correlates directly with age (Hallett et al., 2019). PD diagnoses are projected to double from 6 million in 2015 to 12 million in 2040, coinciding with approximately 1% of the global population exceeding 60 years of age (Ascherio and Ma, 2016; Tysnes and Storstein, 2017; Dorsey and Bloem, 2018). Gait abnormality represents a primary cause of motor dysfunction in PD patients (Frazzitta et al., 2009). These gait abnormalities manifest primarily as postural irregularities, diminished muscle strength in major limb and trunk muscle groups, reduced balance function, initiation difficulties, decreased stride length, inability to halt at will, turning challenges, and bradykinesia. This walking dysfunction in PD patients elevates fall risk and significantly impairs daily living capabilities.

Current PD treatment strategies aim to alleviate symptoms and decelerate disease progression (Raza et al., 2019). The prevailing PD treatment model involves anti-Parkinson’s medications or Deep Brain Stimulation, which often prove inadequate, yielding minimal or no long-term patient improvement (Scelzo et al., 2019). Adjunctive and complementary treatments, such as exercise, can mitigate side effects of anti-Parkinson’s drug therapy and have demonstrated efficacy in improving movement disorders including balance, gait, fall risk, and physical function while reducing fall incidence (Feng et al., 2020; Mak and Wong-Yu, 2019). An increasing body of evidence supports the crucial role of exercise therapy (Tomlinson et al., 2013; Abbruzzese et al., 2016). Dance exercise (DE) can down-regulate α-Syn protein level to a certain extent, inhibit neuronal apoptosis, improve mitochondrial dysfunction, and thus restore the motor function of early patients (Koo et al., 2017). Resistance training (RT) is a strength exercise that can enhance muscle strength by overcoming resistance in local muscle groups. It can also improve the body’s neuroplasticity, up-regulate the expression level of dopaminergic neurotransmitters and receptors, promote the release of non-dopaminergic transmitters such as norepinephrine and 5-hydroxytryptamine (Qian et al., 2024), and improve the motor symptoms of Parkinson’s patients. Aerobic exercise (AE) can improve motor function in patients with Parkinson’s disease by regulating neurotrophic factors to support synaptic formation and angiogenesis, inhibit oxidative stress and improve mitochondrial function (Feng et al., 2020). However, the optimal exercise type for treating gait in PD patients remains unclear. According to Jiang’s traditional meta-analysis, Robotic Assisted Gait Training (RAGT) can effectively enhance PD patients’ walking function and gait performance (Jiang et al., 2024). In a conventional meta-analysis, Bishnoi found that Treadmill Training improved step and stride lengths in PD patients (Bishnoi et al., 2022). Nevertheless, a direct comparison between RAGT and Treadmill Training is currently lacking.

Network meta-analysis (NMA) has gained prominence in evaluating medical interventions due to its capacity to estimate the relative effectiveness and ranking of interventions, even in the absence of direct comparisons (Bafeta et al., 2014). Although Yang explored the influence of exercise patterns on Parkinson’s patients, the exercise was classified into 24 categories, and there was a lack of research on six-minute walk test (6MWT) and Step-length outcome indicators (Yang et al., 2022). Victor explored the intervention measures to improve gait in Parkinson’s disease, but there was a lack of studies on Stride length, 6MWT, and Step length (Hvingelby et al., 2022). Therefore, our study made a detailed division of movement modes, compared the gait forms of more PD patients, determined the best exercise mode to improve the gait of PD patients, and guided PD patients to choose the best exercise mode.

This network meta-analysis was designed according to the guidelines for Preferred Reporting Items of Systems Review and Network Meta-Analysis (PRISMA-NMA) (Hutton et al., 2015).

The computer searched PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, Cochrane Library, CNKI, and other databases, and the search period was established until August 20, 2024. The search takes the way of combining subject words and free words. The search strategy uses Pubmed as an example, as shown in Appendix 1.

The inclusion criteria for study selection were based on the PICOS methodology (Participants, interventions, comparators, outcomes, and study design) (Hutton et al., 2015), shown in Table 1. In addition, we provide detailed definitions of 29 intervention terms. Each intervention is defined in Appendix 2.

The following data were extracted independently by two reviewers: first author, year of publication, country, sample size, intervention mode, intervention time, and intervention period. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (mean ± SD). If the outcome indicator reports multiple points, we extract data for the most recent time.

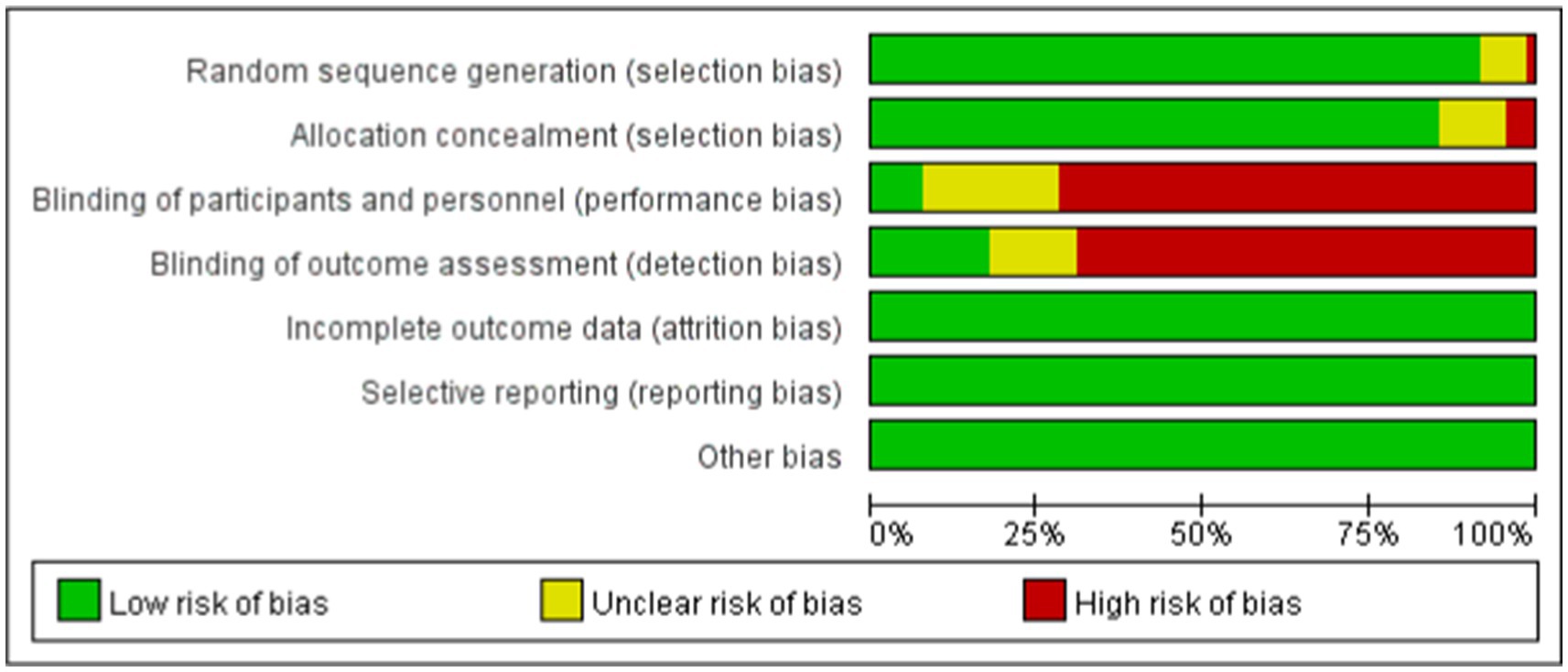

The risk of bias was assessed independently by two reviewers and by a third reviewer using the tools provided by the Cochrane Collaboration (Higgins et al., 2011), including sequence generation, hidden assignment, blinking, incomplete outcome data, non-selective reporting of results, and other sources of bias. Each criterion was judged to have a low, unclear, or high risk of bias.

The netmeta package of R-4.2.1 software was used to perform mesh meta-analysis. Use the STATA 15.1 “networkplot” feature to draw and generate a network diagram that describes and presents different forms of exercises. We use nodes representing various interventions and edges representing head-to-head comparisons between interventions. Node splitting assesses inconsistencies between direct and indirect comparisons (Rücker and Schwarzer, 2015). The combined estimates and their 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated using random effects network analysis. When we are interested in results using the same unit of measure in a study, consider analyzing the results as a therapeutic effect by means difference (MD) or evaluating standardized mean difference (SMD). A pair-to-pair random-effects meta-analysis was used to compare various exercise therapies. The heterogeneity of all pair-to-pair comparisons was assessed using the I2 statistic, and publication bias was evaluated using the p-value of Egger’s test and the funnel plot.

After deleting duplicates, 1,115 records were retrieved, 123 duplicates were removed, 891 articles with inconsistent titles were deleted, 33 articles with inconsistent titles were removed after reading the full text, and 68 articles were finally included (Appendix 3). The research flow chart is shown in Figure 1.

The included studies, published between 2007 and 2024, compared the effects of 29 different forms of exercise on people with Parkinson’s disease. The duration of intervention ranged from 3 to 48 weeks. A total of 3,114 patients were reported. Of all the included studies, 33 reported Gait velocity, 16 reported Step length, 19 reported Stride length and 35 reported 6MWT. The characteristics of the studies and participants are shown in Table 2 and Appendix 3. The risk of bias assessment for each study is summarized in Appendix 4 and Figure 2.

Figure 2. Percentage of studies examining the efficacy of exercise training in patients with non-specific chronic low back pain with low, unclear, and high risk of bias for each feature of the Cochrane risk of bias tool.

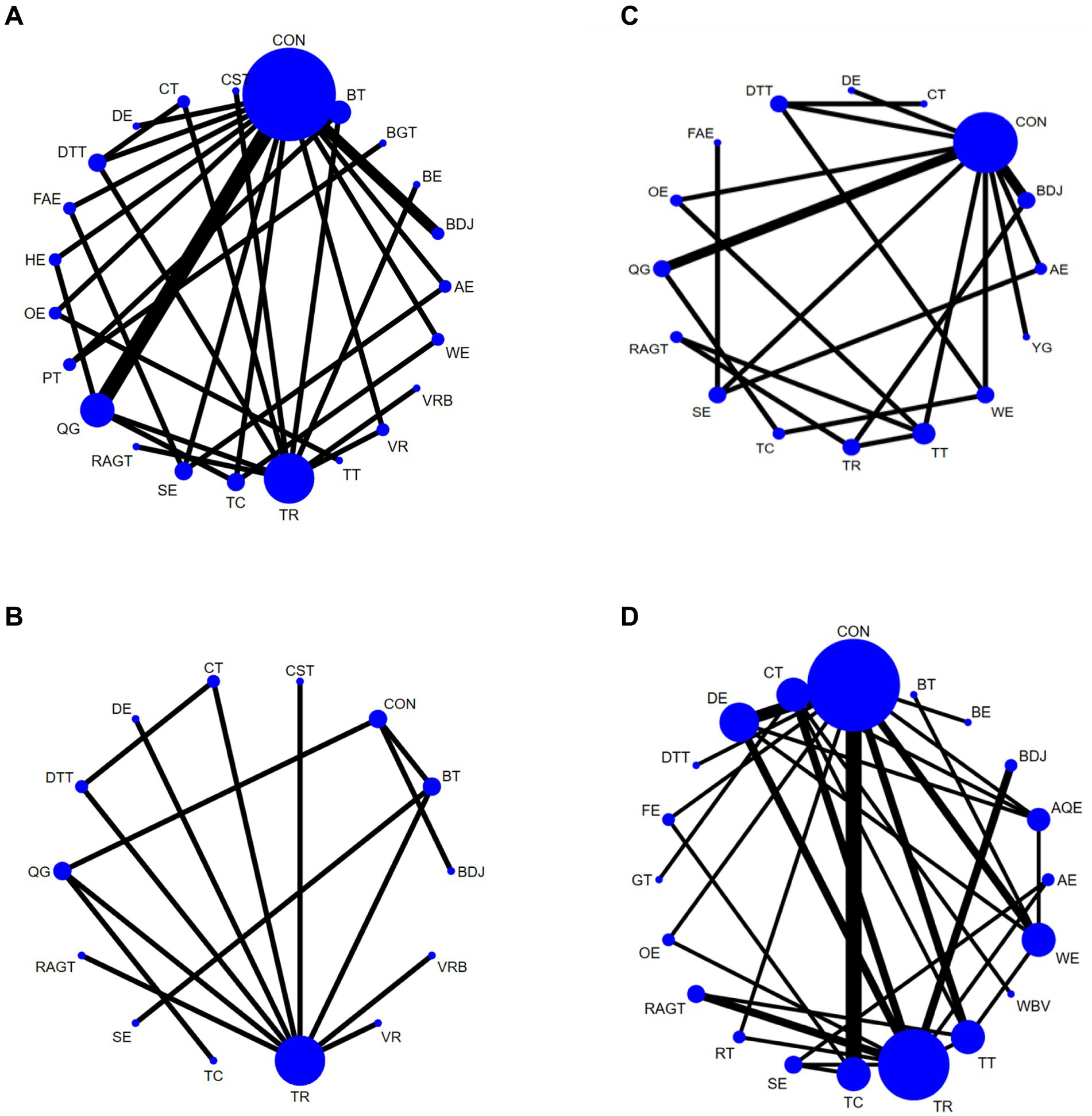

A total of 33 studies evaluated Gait velocity, involving 1,574 participants. We included the following 23 exercise measures in our network meta-analysis (Figure 3A):

Figure 3. Network diagram of Gait velocity (A), Step length (B), Gait velocity (C), and 6MWT (D), in patients with Parkinson’s disease. The node size represents the number of times the exercise appears in any comparison about that treatment, and the width of the edge represents the total sample size in the comparison it connects. Aerobic exercise (AE), Aquatic Exercise (AQE), Whole body vibration training (WBV), Virtual reality (VR), Treadmill training (TT), Resistance training (RT), Tai Chi (TC), Power Training (PT), Biofeedback Balance and Gait Training (BGT), Control group (CON), Walking exercise (WE), Dance exercise (DE), Balance training (BT), Game training (GT), Baduanjin (BDJ), Home exercise (HE), Yoga (YG), Boxing exercise (BE), Robotic Assisted Gait Training (RAGT), Combined therapy (CT), Traditional Rehabilitation (TR), Dual task training (DTT), Stretch exercise (SE), Five animal exercises (FAE), Other exercise (OE), Fitness exercise (FE), Qigong (QG), Virtual reality balance training (VRB), Core strength training (CST).

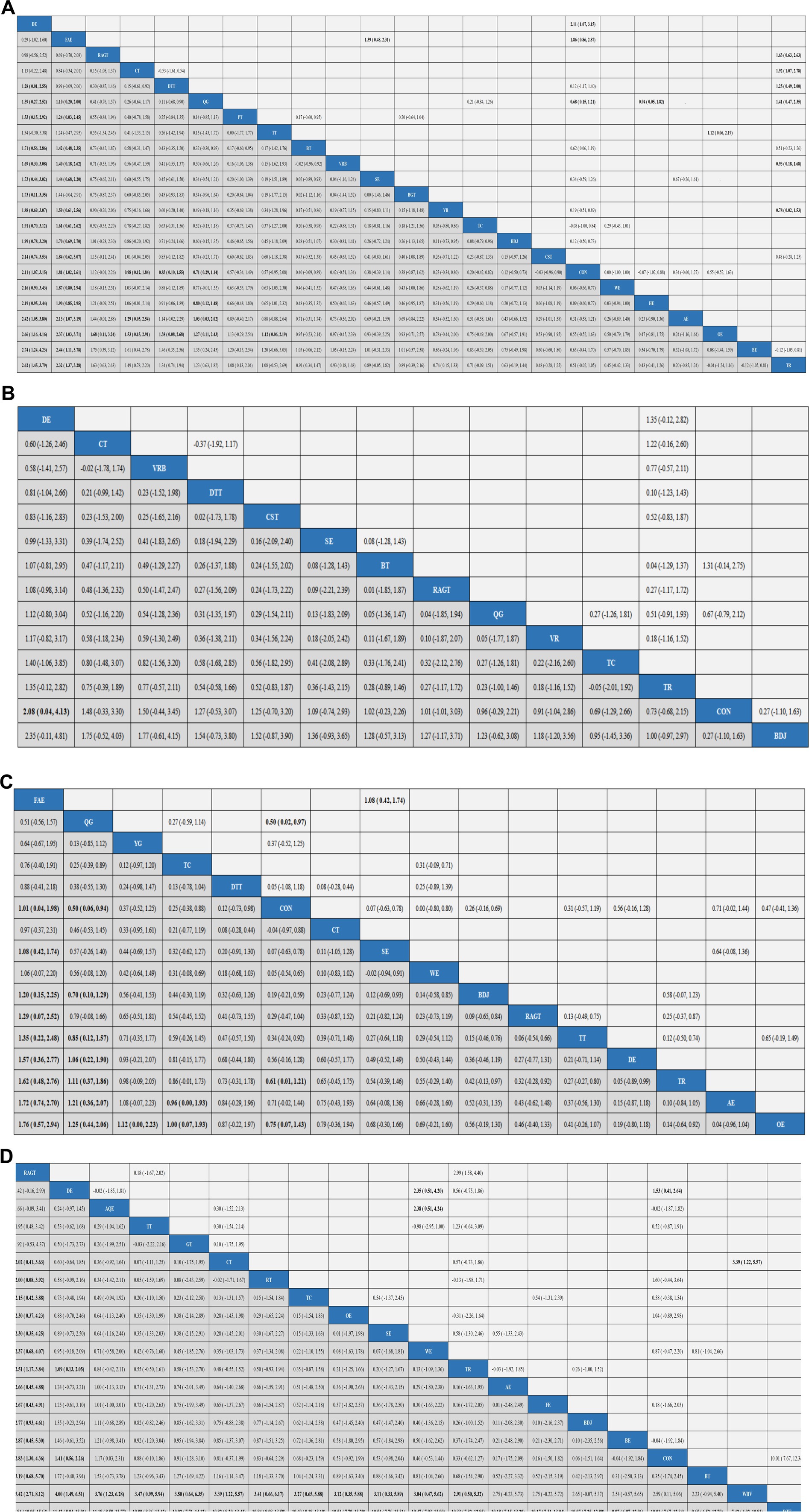

Aerobic exercise (AE), Virtual reality (VR), Treadmill training (TT), Tai Chi (TC), Power Training (PT), Biofeedback Balance and Gait Training (BGT), Control group (CON), Walking exercise (WE), Dance exercise (DE), Balance training (BT), Baduanjin (BDJ), Home exercise (HE), Boxing exercise (BE), Robotic Assisted Gait Training (RAGT), Combined therapy (CT), Traditional Rehabilitation (TR), Dual task training (DTT), Stretch exercise (SE), Five animal exercises (FAE), Other exercise (OE), Qigong (QG), Virtual reality balance training (VRB), Core strength training (CST). Our results show that DE is higher than CON (SMD, 2.11; 95% CI, 1.07 to 3.15), WE (SMD, 2.16; 95% CI 0.90 to 3.43), HE (SMD, 2.19; 95% CI 0.95 to 3.44), AE (SMD, 2.42; 95% CI 1.05 to 3.80), OE (SMD, 2.66; 95% CI 1.16 to 4.16), BE (SMD, 2.74; 95% CI 1.24 to 4.23), TR (SMD2.62; 95% CI 1.45 to 3.79) to better improve Gait velocity in patients with Parkinson’s disease (Figure 4A). In addition, we performed the Egger’s test to assess publication bias (p = 0.325) (Appendix 5.1). The included studies did not show publication bias. Heterogeneity and inconsistencies in the mesh meta-analysis were also evaluated (Appendix 6). The most direct comparisons are CON VS QG (Appendix 7.1).

Figure 4. Results analysis league chart. Gait velocity (A), Step length (B), Gait velocity (C), and 6MWT (D). The data are the mean difference and 95% confidence interval of continuous data. Aerobic exercise (AE), Aquatic Exercise (AQE), Whole body vibration training (WBV), Virtual reality (VR), Treadmill training (TT), Resistance training (RT), Tai Chi (TC), Power Training (PT), Biofeedback Balance and Gait Training (BGT), Control group (CON), Walking exercise (WE), Dance exercise (DE), Balance training (BT), Game training (GT), Baduanjin (BDJ), Home exercise (HE), Yoga (YG), Boxing exercise (BE), Robotic Assisted Gait Training (RAGT), Combined therapy (CT), Traditional Rehabilitation (TR), Dual task training (DTT), Stretch exercise (SE), Five animal exercises (FAE), Other exercise (OE), Fitness exercise (FE), Qigong (QG), Virtual reality balance training (VRB), Core strength training (CST).

A total of 15 studies evaluated GUT, involving 802 participants. We included the following 14 exercise measures in the network meta-analysis (Figure 3B): Virtual reality (VR), Tai Chi (TC), Control group (CON), Dance exercise (DE), Balance training (BT), Baduanjin (BDJ), Robotic Assisted Gait Training (RAGT), Combined therapy (CT), Traditional Rehabilitation (TR), Dual task training (DTT), Stretch exercise (SE), Qigong (QG), Virtual reality balance training (VRB), Core strength training (CST). The results show that DE is superior to CON (SMD, 2.08; 95% CI 0.04 to 4.13) (Figure 4B). In addition, we performed the Egger test to assess publication bias (p = 0.239) (Appendix 5.2). The included studies did not show publication bias. We also evaluated the heterogeneity and inconsistencies of the mesh meta-analysis (Appendix 6). We made a direct comparison of exercise interventions (Appendix 7.2).

A total of 19 studies evaluated, involving 741 participants. We included the following 16 exercise measures in the network meta-analysis (Figure 3C): Aerobic exercise (AE), Treadmill training (TT), Tai Chi (TC), Control group (CON), Walking exercise (WE), Dance exercise (DE), Baduanjin (BDJ), Yoga (YG), Robotic Assisted Gait Training (RAGT), Combined therapy (CT), Traditional Rehabilitation (TR), Dual task training (DTT), Stretch exercise (SE), Five animal exercises (FAE), Other exercise (OE), Qigong (QG). The results show that: FAE is superior to CON (SMD, 1.01; 95% CI 0.04 to 1.98), SE (SMD, 1.08; 95% CI 0.42, 1.74), BDJ (SMD, 1.20; 95% CI 0.15 to 2.25), RAGT (SMD, 1.29; 95% CI 0.07 to 2.52), TT (SMD, 1.35; 95% CI 0.22 to 2.48), DE (SMD, 1.57; 95% CI 0.36 to 2.77), TR (SMD, 1.62; 95% CI 0.48 to 2.76), AE (SMD, 1.72; 95% CI 0.74 to 2.70), OE (SMD, 1.76, 95% CI 0.57 to 2.94) in improving Gait velocity (Figure 4C). In addition, we assessed publication bias using the Egger test (p = 0.659) (Appendix 5.3). The included studies did not show publication bias. We also evaluated heterogeneity and inconsistencies in the mesh meta-analysis (Appendix 6). We made a direct comparison of exercise interventions (Appendix 7.3). The most direct comparisons are CON vs. QG and BDJ vs. CON.

A total of 35 studies evaluated, involving 1,616 participants. We included the following 20 exercise measures in the network metaanalysis (Figure 3D): Aerobic exercise (AE), Aquatic Exercise (AQE), Whole body vibration training (WBV), Treadmill training (TT), Resistance training (RT), Tai Chi (TC), Control group (CON), Walking exercise (WE), Dance exercise (DE), Balance training (BT), Game training (GT), Baduanjin (BDJ), Boxing exercise (BE), Robotic Assisted Gait Training (RAGT), Combined therapy (CT), Traditional Rehabilitation (TR), Dual task training (DTT), Stretch exercise (SE), Other exercise (OE), Fitness exercise (FE). The results show that: RAGT is superior to CT (MD, 2.02; 95% CI 0.41 to 3.63), RT (MD, 2.00; 95% CI 0.08, 3.92), TC (MD, 2.15; 95% CI 0.42, 3.88), OE (MD, 2.30; 95% CI 0.37 to 4.23), SE (MD, 2.30; 95% CI 0.35 to 4.25), WE (MD 2.37; 95% CI 0.68 to 4.07), TR (MD, 2.51; 95% CI 1.17 to 3.84), AE (MD2.66; 95% CI 0.45 to 4.88), FE (MD, 2.67; 95% CI 0.43 to 4.91), BDJ (MD, 2.77; 95% CI 0.93 to 4.61), BE (MD, 2.87; 95% CI 0.45 to 5.30), CON (MD, 2.83; 95% CI 1.30 to 4.36), BT (MD, 3.19; 95% CI 0.68 to 5.70), WBV (MD, 5.42; 95% CI 2.71 to 8.21), DTT (MD, 12.84; 95% CI 10.05 to 15.63) in improving 6MWT (Figure 4D). In addition, we assessed publication bias using the Egger test (p = 0.688) (Appendix 5.3). The included studies did not show publication bias. We also evaluated heterogeneity and inconsistencies in the mesh meta-analysis (Appendix 6). We made a direct comparison of exercise interventions (Appendix 7.3). The most direct comparisons are CON VS DE.

Gait disorder is one of the common manifestations of motor symptoms in PD patients, which often leads to loss of motor ability and increased mortality. It is one of the essential reasons for the decline in quality of life in PD patients. Therefore, it is of great significance to improve the movement mode of PD patients with gait disorders clearly. A total of 3,114 PD patients were included in our study, and 29 exercise methods were explored to enhance the improvement of gait disorders in PD patients.

Gait velocity and step length are frequently utilized as indicators to monitor the progression of gait disorders and treatment efficacy in patients with PD (Chien et al., 2006). Our study revealed that DE demonstrated superior efficacy compared to the Control group (CON), Walking exercise (WE), Home exercise (HE), Aerobic exercise (AE), Other exercise (OE), Boxing exercise (BE), and Traditional Rehabilitation (TR) in enhancing gait velocity among PD patients. Dance, as an art form, integrates aesthetic imagery, musicality, and goal-setting. It typically begins with a gradual warm-up, potentially improving strength, flexibility, and coordination. Furthermore, improvisation, co-creation, and aesthetic interpretation stimulate participants’ creativity and imagination. The music incorporated in dance provides essential auditory cues for movement through rhythmic and speed variations (Batson et al., 2016). Tactile feedback can also facilitate movement. For instance, when partnered with a submissive individual, rhythmic auditory cues and attention strategies prove more advantageous in improving walking speed during dual tasks (Baker et al., 2007; Westheimer, 2008). Research indicates that DE can mitigate progressive neuronal axon degeneration, promote dendritic formation of new synapses, establish novel neural connections, activate or create new neural pathways, enhance the brain’s regulatory role on limbs, improve joint flexibility, and alleviate movement disorders (Huang and He, 2016). Ashoori et al. (2015) suggested that basal ganglia lesions in PD patients may be associated with reduced internal rhythm, leading to impaired motor initiation and rhythm control. Basal ganglia activity increases during dance, particularly in the core-shell region (Brown et al., 2006). This suggests that dance may beneficially stimulate the basal nucleus in PD patients, enabling them to execute relatively complex movements and enhance their motor abilities. Our meta-analysis demonstrated that exercise interventions can improve step length in PD patients. Interestingly, our study only found DE to be superior to CON in improving step length in PD patients. This implies that most intervention studies in this meta-analysis had negligible or statistically insignificant effects on the step length parameter. Consequently, we recommend that future studies increase their focus on step length in PD research. In addition, our study also found that DE was better than CON in improving step length, but the results may be unstable. Considering that we may have many dances (tango, waltz, samba, Irish dance, ballroom dance, etc.), we suggest a detailed division of dance types for future research. Exploring which kind of dance improves stride length in patients with Parkinson’s disease.

Our results indicate that FAE is superior to Control group (CON), Stretch exercise (SE), Baduanjin (BDJ), Robotic Assisted Gait Training (RAGT), Treadmill training (TT), Dance exercise (DE), Traditional Rehabilitation (TR), Aerobic exercise (AE), and Other exercise (OE) in improving Gait velocity. FAE, a traditional Chinese exercise, primarily emulates the movements of tigers, deer, bears, apes, and birds. This practice effectively stretches muscles and joints, engages various muscle groups, and involves alternating the body’s center of gravity from front to back and left to right, thereby improving movement ability, balance, and coordination. Patients with PD typically exhibit a stooped posture, reduced arm swing, decreased lower limb motion range, slower stride speed, shorter stride length, reduced ground clearance, and prolonged double support period, increasing their susceptibility to falls (Cc and Rc, 2018; Wassom et al., 2015). FAE’s efficacy in improving stride length for PD patients may be attributed to its emphasis on forward stride movements. The exercise requires patients to lift their hips while stepping forward, lunge, swing their arms, and shift their center of gravity between stride types, effectively enhancing their ability to take longer strides and mitigating stride ability decline (Xiaofei and Jinggang, 2018). Given its distinct cultural characteristics, promoting FAE warrants consideration. Strategies for promotion could include organizing basic FAE courses, offering accessible introductory sessions, and providing easily comprehensible multi-language or online courses through digital platforms.

6MWT is a 6-min walking test for patients, which can well reflect the walking endurance and cardiopulmonary function level of patients. Our NMA found that Robotic Assisted Gait Training (RAGT) was superior to Combined therapy (CT), Tai Chi (TC), Other exercise (OE), Stretch exercise (SE), Walking exercise (WE), Traditional Rehabilitation (TR), Aerobic exercise (AE), Fitness exercise (FE), Baduanjin (BDJ), Boxing exercise (BE), Control group (CON), Balance training (BT), Whole body vibration training (WBV), Dual task training (DTT) in improving 6MWT in PD patients. RAGT intervention is grounded in the theory of central nervous system plasticity and functional reorganization. Repetitive, purposeful weight-bearing walking training can enhance balance, facilitating gait automation and improved step speed (Aprile et al., 2019; Toole et al., 2005). Janssen’s study found that enhancing patients’ attention through sensory stimulation increased their walking speed in a straight line (Janssen et al., 2017). RAGT provides diverse sensory stimulation and continuous treatment (Mehrholz et al., 2017), promoting comprehensive motor function recovery and increasing motor ability in PD patients. Furthermore, external rhythm can compensate for defective internal rhythm in the basal ganglia, serving as proprioceptive cues (Nieuwboer et al., 2009), This allows for earlier, more targeted balance training, improving balance and subsequently increasing PD patients’ motor ability (Capecci et al., 2019). Ongoing robot research optimization, exemplified by the new Lokomat robot integrating weight reduction, platform running, and gait correction, enhances timely feedback and evaluation. This enables patients to simulate normal walking under weight reduction conditions (Zhao et al., 2024). Suspension weight reduction maintains patients’ upright posture for balance and reduces walking effort. The WalkBotS robot, supplemented with virtual reality games, achieves direct human-environment interaction. Virtual reality technology provides visual stimulation, better approximating real-life conditions, improving training engagement, and enhancing patient compliance (You et al., 2022). Future research will further explore the effectiveness of this robot-assisted gait training.

This study represents the most comprehensive and systematic comparative meta-analysis of exercise effects on gait in individuals with PD. With a substantial sample size of 68 studies and 3,114 patients, encompassing 29 exercise interventions, it provides direct and indirect comparisons to offer new, comprehensive, evidence-based recommendations. The study holds significant clinical relevance, demonstrating that DE, FAE, and RAGT can markedly improve gait in PD patients. However, it is important to acknowledge potential limitations of network meta-analysis, such as reliance on indirect comparisons and variability in comparator groups. Notably, exercise emerges as an effective non-pharmacological intervention for PD management. Despite these findings, caution is warranted in interpreting the results due to relatively small sample sizes for each intervention, which may influence outcomes. Gait problems in PD patients worsen with the progression of the disease, and patients have significant individual differences in gait performance (Zhang et al., 2021; Macht et al., 2007). Future studies can focus specifically on each stage of the disease to further reveal the impact of exercise intervention in different disease stages on gait in PD patients. Additionally, natural polyphenols may alleviate bradykinesia, enhance balance and coordination, and reduce turn time in PD patients, possibly due to their anti-striatal oxidative damage properties, inhibition of microglial activation and inflammatory factor secretion, and enhancement of neurotrophic factor expression (Kujawska and Jodynis-Liebert, 2018). Therefore, while focusing on movement interventions for PD patients, it is crucial to consider other factors influencing gait in this population. Previous research has highlighted exercise intensity as a crucial factor influencing exercise effectiveness (Borde et al., 2015; Milanović et al., 2015). However, different exercise modalities used different intensity criteria and intervention duration, which are significant limitations. Some studies included in this analysis failed to report exercise intensity and intervention duration. Future studies should prioritize detailed reporting of exercise intensity and intervention duration and a comparative analysis of gait improvement in PD patients at different intensity levels and intervention times. This approach will help determine the optimal exercise intensity to enhance gait function in PD patients.

Our study revealed that DE demonstrated superior efficacy in improving gait speed and step length among PD patients compared to other exercise modalities. Furthermore, FAE and RAGT exhibited greater effectiveness in enhancing step length and 6MWT performance, respectively, in individuals with PD. Overall, exercise interventions show significant benefits in improving gait parameters in PD patients. While exercise demonstrates a substantial impact on ameliorating PD symptoms, further investigation is needed to elucidate the underlying molecular mechanisms and neural circuit connections and regulation. Additionally, our quality evaluation highlighted that many studies lacked blinding procedures and randomized grouping, resulting in generally low certainty of evidence. Consequently, we recommend stricter quality control measures in future research, along with increased sample sizes, to further validate the findings of this study. While our study identifies the best form of exercise, safety is a critical consideration for people with Parkinson’s when choosing a form of exercise. To ensure safety, the condition of patients with Parkinson’s disease can be comprehensively considered when choosing exercise methods.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

YL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JH: Conceptualization, Resources, Software, Writing – original draft. JW: Methodology, Resources, Software, Writing – original draft. YC: Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnagi.2025.1496112/full#supplementary-material

Abbruzzese, G., Marchese, R., Avanzino, L., and Pelosin, E. (2016). Rehabilitation for Parkinson’s disease: current outlook and future challenges. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 22, S60–S64. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2015.09.005

Aprile, I., Iacovelli, C., Goffredo, M., Cruciani, A., Galli, M., Simbolotti, C., et al. (2019). Efficacy of end-effector robot-assisted gait training in subacute stroke patients: clinical and gait outcomes from a pilot bi-Centre study. NeuroRehabilitation 45, 201–212. doi: 10.3233/NRE-192778

Ascherio, A., and Ma, S. (2016). The epidemiology of Parkinson’s disease: risk factors and prevention. Lancet Neurol. 15, 1257–1272. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(16)30230-7

Ashoori, A., Dm, E., and Jankovic, J. (2015). Effects of auditory rhythm and music on gait disturbances in Parkinson’s disease. Front. Neurol. 6:234. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2015.00234

Bafeta, A., Trinquart, L., Seror, R., and Ravaud, P. (2014). Reporting of results from network meta-analyses: methodological systematic review. BMJ 348:g1741. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1741

Baker, K., Rochester, L., and Nieuwboer, A. (2007). The immediate effect of attentional, auditory, and a combined cue strategy on gait during single and dual tasks in Parkinson’s disease. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 88, 1593–1600. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.07.026

Batson, G., Hugenschmidt, C. E., and Soriano, C. T. (2016). Verbal auditory cueing of improvisational dance: a proposed method for training Agency in Parkinson’s disease. Front. Neurol. 7:15. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2016.00015

Bishnoi, A., Lee, R., Hu, Y., Mahoney, J. R., and Hernandez, M. E. (2022). Effect of treadmill training interventions on spatiotemporal gait parameters in older adults with neurological disorders: systematic review and Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19:824. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19052824

Borde, R., Hortobágyi, T., and Granacher, U. (2015). Dose-response relationships of resistance training in healthy old adults: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Sports Med. 45, 1693–1720. doi: 10.1007/s40279-015-0385-9

Brown, S., Mj, M., and Lm, P. (2006). The neural basis of human dance. Cereb. Cortex 16, 1157–1167. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhj057

Capecci, M., Pournajaf, S., Galafate, D., Sale, P., le Pera, D., Goffredo, M., et al. (2019). Clinical effects of robot-assisted gait training and treadmill training for Parkinson’s disease. A randomized controlled trial. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 62, 303–312. doi: 10.1016/j.rehab.2019.06.016

Cc, L., and Rc, W. (2018). The impact of walking speed on interlimb coordination in individuals with Parkinson’s disease. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 30, 658–662. doi: 10.1589/jpts.30.658

Chien, S. L., Lin, S. Z., Liang, C. C., Soong, Y. S., Lin, S. H., Hsin, Y. L., et al. (2006). The efficacy of quantitative gait analysis by the Gaitrite system in evaluation of parkinsonian bradykinesia. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 12, 438–442. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2006.04.004

Dorsey, E. R., and Bloem, B. R. (2018). The Parkinson pandemic-a call to action. JAMA Neurol. 75, 9–10. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.3299

Feng, Y. S., Yang, S. D., Tan, Z. X., Wang, M. M., Xing, Y., Dong, F., et al. (2020). The benefits and mechanisms of exercise training for Parkinson’s disease. Life Sci. 245:117345. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117345

Frazzitta, G., Maestri, R., Uccellini, D., Bertotti, G., and Abelli, P. (2009). Rehabilitation treatment of gait in patients with Parkinson’s disease with freezing: a comparison between two physical therapy protocols using visual and auditory cues with or without treadmill training. Mov. Disord. 24, 1139–1143. doi: 10.1002/mds.22491

Hallett, P. J., Engelender, S., and Isacson, O. (2019). Lipid and immune abnormalities causing age-dependent neurodegeneration and Parkinson’s disease. J. Neuroinflammation 16:1532. doi: 10.1186/s12974-019-1532-2

Higgins, J. P., Altman, D. G., and Gøtzsche, P. C. (2011). The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928

Huang, H., and He, Y. (2016). Exercise intervention for Parkinson’s disease. Chin. J. Gerontol. 36, 3861–3865. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1005-9202.2016.15.117

Hutton, B., Salanti, G., Caldwell, D. M., Chaimani, A., Schmid, C. H., and Cameron, C. (2015). The Prisma extension statement for reporting of systematic reviews incorporating network meta-analyses of health care interventions: checklist and explanations. Ann. Intern. Med. 162, 777–784. doi: 10.7326/M14-2385

Hvingelby, V. S., Glud, A. N., Sørensen, J. C. H., Tai, Y., Andersen, A. S. M., Johnsen, E., et al. (2022). Interventions to improve gait in Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials and network meta-analysis. J. Neurol. 269, 4068–4079. doi: 10.1007/s00415-022-11091-1

Janssen, S., Bolte, B., Nonnekes, J., Bittner, M., Bloem, B. R., Heida, T., et al. (2017). Usability of three-dimensional augmented visual cues delivered by smart glasses on (freezing of) gait in Parkinson’s disease. Front. Neurol. 8:279. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2017.00279

Jiang, X., Zhou, J., Chen, Q., Xu, Q., Wang, S., Yuan, L., et al. (2024). Effect of robot-assisted gait training on motor dysfunction in Parkinson’s patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Back Musculoskelet. Rehabil. 37, 253–268. doi: 10.3233/BMR-220395

Koo, J. H., Cho, J. Y., and Lee, U. B. (2017). Treadmill exercise alleviates motor deficits and improves mitochondrial import machinery in an MPTP-induced mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Exp. Gerontol. 89, 20–29. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2017.01.001

Kujawska, M., and Jodynis-Liebert, J. (2018). Polyphenols in Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review of in vivo studies. Nutrients 10:642. doi: 10.3390/nu10050642

Macht, M., Kaussner, Y., Möller, J. C., Stiasny‐Kolster, K., Eggert, K. M., Krüger, H. P., et al. (2007). Predictors of freezing in Parkinson’s disease: a survey of 6,620 patients. Mov. Disord. 22, 953–956. doi: 10.1002/mds.21458

Mak, M. K., and Wong-Yu, I. S. (2019). Exercise for Parkinson’s disease. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 147, 1–44. doi: 10.1016/bs.irn.2019.06.001

Mehrholz, J., Thomas, S., Werner, C., Kugler, J., Pohl, M., and Elsner, B. (2017). Electromechanical-assisted training for walking after stroke: a major update of the evidence. Stroke 48:18018. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.018018

Milanović, Z., Sporiš, G., and Weston, M. (2015). Effectiveness of high-intensity interval training (hit) and continuous endurance training for Vo2max improvements: a systematic review and Meta-analysis of controlled trials. Sports Med. 45, 1469–1481. doi: 10.1007/s40279-015-0365-0

Nieuwboer, A., Rochester, L., Müncks, L., and Swinnen, S. P. (2009). Motor learning in Parkinson’s disease: limitations and potential for rehabilitation. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 15, S53–S58. doi: 10.1016/S1353-8020(09)70781-3

Pajares, M., Rojo, A., Manda, G., Boscá, L., and Cuadrado, A. (2020). Inflammation in Parkinson’s disease: mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Cells 9:1687. doi: 10.3390/cells9071687

Qian, L., Qianlan, B., and Yongci, H. (2024). Research advances in the influence of exercise on Parkinson disease. J. Apoplexy Nerv. Dis. 41, 71–76. doi: 10.19845/j.cnki.zfysjjbzz.2024.0014

Raza, C., Anjum, R., and Shakeel, N. U. A. (2019). Parkinson’s disease: mechanisms, translational models and management strategies. Life Sci. 226, 77–90. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2019.03.057

Rücker, G., and Schwarzer, G. (2015). Ranking treatments in frequentist network meta-analysis works without resampling methods. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 15:58. doi: 10.1186/s12874-015-0060-8

Scelzo, E., Beghi, E., Rosa, M., Angrisano, S., Antonini, A., Bagella, C., et al. (2019). Deep brain stimulation in Parkinson’s disease: a multicentric, long-term, observational pilot study. J. Neurol. Sci. 405:116411. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2019.07.029

Simon, D. K., Tanner, C. M., and Brundin, P. (2020). Parkinson Disease epidemiology, pathology, genetics, and pathophysiology. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 36, 1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2019.08.002

Tomlinson, C. L., Patel, S., Meek, C., Herd, C. P., Clarke, C. E., and Stowe, R. (2013). Physiotherapy versus placebo or no intervention in Parkinson’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013:CD002817. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002817.pub4

Toole, T., Maitland, C. G., Warren, E., Hubmann, M. F., and Panton, L. (2005). The effects of loading and unloading treadmill walking on balance, gait, fall risk, and daily function in parkinsonism. NeuroRehabilitation 20, 307–322. doi: 10.3233/NRE-2005-20406

Tysnes, O. B., and Storstein, A. (2017). Epidemiology of Parkinson’s disease. J. Neural Transm. 124, 901–905. doi: 10.1007/s00702-017-1686-y

Wassom, D. J., Lyons, K. E., Pahwa, R., and Liu, W. (2015). Qigong exercise may improve sleep quality and gait performance in Parkinson’s disease: a pilot study. Int. J. Neurosci. 125, 578–584. doi: 10.3109/00207454.2014.966820

Westheimer, O. (2008). Why dance for Parkinson’s disease. Topics Geriatr Rehab. 24, 127–140. doi: 10.1097/01.TGR.0000318900.95313.af

Xiaofei, C., and Jinggang, D. (2018). Progress of modern research on five-animal boxing. Henan TR Aditional Chin. Med. 38, 151–154. doi: 10.16367/j.issn.1003-5028.2018.01.0039

Yang, Y., Wang, G., Zhang, S., Wang, H., Zhou, W., Ren, F., et al. (2022). Efficacy and evaluation of therapeutic exercises on adults with Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. 22:813. doi: 10.1186/s12877-022-03510-9

You, Y., Hou, W., and Yu, N. (2022). A survey and perspective on rehabilitation robots for patients suffering from Parkinson’s disease. Robot. 44, 368–384. doi: 10.13973/j.cnki.robot.210263

Zhang, W. S., Gao, C., Tan, Y. Y., and Chen, S. D. (2021). Prevalence of freezing of gait in Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Neurol. 268, 4138–4150. doi: 10.1007/s00415-021-10685-5

Zhao, Q., Bu, S. Y., and Jin, L. J. (2024). Research progress on robot • assisted gait training to improve gait disorder in Parkinson’s disease. Chin J Contemp Neurol Neurosurg. 24, 151–157. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1672-6731.2024.03.007

AE - Aerobic exercise

AQE - Aquatic exercise

WBV - Whole body vibration training

VR - Virtual reality

TT - Treadmill training

RT - Resistance training

TC - Tai Chi

PT - Power training

BGT - Biofeedback balance and gait training

CON - Control group

WE - Walking exercise

DE - Dance exercise

BT - Balance training

GT - Game training

BDJ - Baduanjin

HE - Home exercise

YG - Yoga

BE - Boxing exercise

RAGT - Robotic assisted gait training

CT - Combined therapy

TR - Traditional rehabilitation

DTT - Dual task training

SE - Stretch exercise

FAE - Five animal exercises

OE - Other exercise

FE - Fitness exercise

QG - Qigong

VRB - Virtual reality balance training

CST - Core strength training

Keywords: Parkinson’s disease, gait, 6MWT, network meta-analysis, systematic review

Citation: Li Y, Huang J, Wang J and Cheng Y (2025) Effects of different exercises on improving gait performance in patients with Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Front. Aging Neurosci. 17:1496112. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2025.1496112

Received: 13 September 2024; Accepted: 14 February 2025;

Published: 26 February 2025.

Edited by:

Dimitrios Kikidis, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, GreeceReviewed by:

Francesco Lena, Mediterranean Neurological Institute Neuromed (IRCCS), ItalyCopyright © 2025 Li, Huang, Wang and Cheng. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yue Cheng, MTE5NDIwNjQyN0BxcS5jb20=

†These authors share first authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.