95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Aging Neurosci. , 28 September 2023

Sec. Parkinson’s Disease and Aging-related Movement Disorders

Volume 15 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2023.1255428

This article is part of the Research Topic Hospitalization and Parkinson’s Disease: Safety, Quality and Outcomes View all 14 articles

Background: Parkinson’s disease (PD) increases the risk of hospitalization and complications while in the hospital. Patient-centered care emphasizes active participation of patients in decision-making and has been found to improve satisfaction with care. Engaging in discussion and capturing hospitalization experience of a person with PD (PwP) and their family care partner (CP) is a critical step toward the development of quality improvement initiatives tailored to the unique hospitalization needs of PD population.

Objectives: This qualitative study aimed to identify the challenges and opportunities for PD patient-centered care in hospital setting.

Methods: Focus groups were held with PwPs and CPs to capture first-hand perspectives and generate consensus themes on PD care during hospitalization. A semi-structured guide for focus group discussions included questions about inpatient experiences and interactions with the health system and the clinical team. The data were analyzed using inductive thematic analysis.

Results: A total of 12 PwPs and 13 CPs participated in seven focus groups. Participants were 52% female and 28% non-white; 84% discussed unplanned hospitalizations. This paper focuses on two specific categories that emerged from the data analysis. The first category explored the impact of PD diagnosis on the hospital experience, specifically during planned and unplanned hospitalizations. The second category delves into the unique needs of PwPs and CPs during hospitalization, which included the importance of proper PD medication management, the need for improved hospital ambulation protocols, and the creation of disability informed hospital environment specific for PD.

Conclusion: PD diagnosis impacts the care experience, regardless of the reason for hospitalization. While provision of PD medications was a challenge during hospitalization, participants also desired flexibility in ambulation protocols and an environment that accommodated their disability. These findings highlight the importance of integrating the perspectives of PwPs and CPs when targeting patient-centered interventions to improve hospital experiences and outcomes.

People with a clinical diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease (PD) experience more frequent and prolonged hospitalizations than their age-matched peers (Aminoff et al., 2011; Chou et al., 2011; Hobson et al., 2012; Kowal et al., 2013; Shahgholi et al., 2017; Su et al., 2018). Most hospitalizations occur in general wards and result from a comorbid disorder or health crisis, such as respiratory and urinary tract infections, cardiovascular diseases, falls, and fractures (Woodford and Walker, 2005; Braga et al., 2014; Lubomski et al., 2015; Gil-Prieto et al., 2016; Okunoye et al., 2020; Réa-Neto et al., 2021). It is well documented that during hospitalizations, person with PD (PwP) is at a higher risk of complications, including falls, medication errors, development of delirium and psychosis, and overall decline of their pre-existing motor and non-motor symptoms of PD (Derry et al., 2010; Gerlach et al., 2013; Lubomski et al., 2015; Skelly et al., 2017; Magnuszewski et al., 2022). Improved medication adherence during hospital stays, e-alerts to PD specialists upon admission, development of the Parkinson’s Foundation Aware in Care Hospital Kit, and recommendations for ward certification programs are among the calls for action and quality improvement interventions that have targeted hospital outcomes for PD (Azmi et al., 2019, 2020; Hobson et al., 2019; Aslam et al., 2020; Nance et al., 2020; Parkinson’s Foundation Hospital Safety Kits, 2023). However, to date, only a few studies have reported significant decreases in the length of hospital stay or complications during hospitalization for PD (Skelly et al., 2014; Azmi et al., 2020).

In the context of inpatient hospitalization for older adults and those with chronic and serious medical conditions, patient-centered care (PCC) has revealed benefits in intermediate and distal outcomes, and almost all studies have found positive relationships between PCC approaches and patient satisfaction (Counsell et al., 2000; Wolf et al., 2008; Rocco et al., 2011; Rathert et al., 2013). PCC places patients at the center of the healthcare decision-making process and recognizes the importance of their individual preferences and goals (Berwick, 2009; Institute of Medicine, 2014). Growing awareness of PCC delivery has resulted in the establishment of specialized multidisciplinary teams as the gold standard of outpatient care for PD, as well as the increasing application of palliative care, a traditionally team-based model of care, for the management of the physical, emotional, and spiritual needs of PwPs (Eggers et al., 2018; Connor et al., 2019; Vlaanderen et al., 2019; Bhidayasiri et al., 2020; Kluger et al., 2020; Rajan et al., 2020; Lennaerts-Kats et al., 2022).

Presently, the voices of PwPs and their care partners (CPs) regarding their experiences during hospitalization are not well represented in the literature, and most research on PCC for PD has focused on outpatient care. Studies that qualitatively investigated hospitalization for PD primarily highlighted medication mismanagement, struggles with postoperative confusion, and deterioration of motor symptoms; however, they minimally captured patient-reported needs or experiences of CPs during hospitalization (Barber et al., 2001; Buetow et al., 2009; Gerlach et al., 2012; Carney Anderson and Fagerlund, 2013; Read et al., 2019).

By applying open–ended questions qualitative methods gather detailed and nuanced accounts of participants’ experiences, perceptions, and behavior. Compared to quantitative methods, which are intended to achieve the breadth of understanding of a topic, qualitative methods dive deep into individual experiences and the context surrounding them (Patton, 2002).

Unlike quantitative research, which emphasizes data generalization by employing sample size calculation and randomization, qualitative methods place primary emphasis on saturation, which means collecting the information until no new substantive insight emerges (Francis et al., 2010). To achieve saturation, researchers often use purposeful sampling by recruiting individuals who are especially knowledgeable about or experienced with a phenomenon of interest, available and willing to participate, and can communicate experiences and opinions in an articulate, expressive, and reflective manner (Guest et al., 2006). This approach can collect robust and meaningful data per participant, and thus fewer participants within the sample are needed to achieve saturation or “information power” of the sample (Malterud et al., 2016). The choice for qualitative data analysis is dictated by qualitative study methods and the research question. Since open–ended surveys, focus groups, and one on one interviews create information-rich and nuanced datasets, thematic analysis is commonly applied to this qualitative method. This involves creating codes (labels) to organize and describe the data, and then actively synthesizing the data by framing, interpreting, and/or connecting data elements to construct the themes (Kiger and Varpio, 2020). The advantage of thematic analysis is that it offers researchers flexibility concerning the type of research questions it can address, however, it also implies a systematic and iterative process that requires careful attention and interpretation of the data, and then a rigorous approach to identifying and validating themes (Braun and Clarke, 2006, 2012; Kiger and Varpio, 2020).

To expand the scope of patient-centered PD care from outpatient to inpatient settings, we employed qualitative research to gather and analyze valuable self-reported experiences of PwPs and CPs regarding hospitalization.

Focus groups were selected as the optimal methodology to capture first-hand experiences of PwPs and CPs, and to generate themes on PD care during hospitalization (Patton, 2002; Busetto et al., 2020). Participants either had a neurologist-confirmed clinical diagnosis of PD or were family members of a person with a neurologist-confirmed clinical diagnosis of PD and were able to participate in the interview. Hospitalization was defined as a planned (e.g., scheduled surgery or procedure) or unplanned (e.g., emergent or urgent admission) hospital stay for at least 24 h between January 2018 and July 2022. Patients hospitalized for deep brain stimulation surgery were excluded. All participants had to be at least 18 years old, with no upper age limit.

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved and overseen by the Office of Human Research Ethics the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The participants provided verbal informed consent prior to any study activity including data collection. This study was supported by a Parkinson’s Foundation Community Outreach Resource Education grant.

Participants were recruited through clinician referrals, announcements shared with North Carolina-based PD support groups, and flyers placed at the outpatient neurology clinic at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. A purposive sampling strategy was used to recruit a variety of PwPs and CPs with a range of hospital experiences (Table 1). The focus groups were capped at a maximum of five participants to allow for adequate time for each person to actively participate in the focus group discussion and accommodate for inherent challenges with communication and processing speed in PD. Quotas were applied to the patient sample to ensure a diverse representation, including demographic (e.g., sex, age, race) and clinical characteristics (e.g., stage of condition as defined by Hoehn and Yahr score, planned vs. unplanned hospitalization experiences) (Goetz et al., 2004). Half-way through recruitment, additional efforts were made to enroll participants from underrepresented demographics of the study.

A semi-structured discussion guide, developed de novo by the research team based on a review of the published literature on hospitalizations in PD, was used to structure the focus groups (Supplementary Appendix S1). As the data collection progressed, the discussion guide was adapted to incorporate new issues raised by the participants. The questions focusing on aspects of hospital admission, inpatient experiences, discharge processes, interactions with the health system and team, and lived experiences of PwPs and CPs thought to be most relevant to patient- and family-centered outcomes. An experienced group moderator (J.S.) used probing questions to further expand the discussion. Prior to the focus groups, all the participants completed a brief questionnaire to capture their demographic information.

All focus groups were conducted virtually on the Zoom platform and were recorded and transcribed verbatim. Each group was 120 min in length. Identifiers were stripped from the transcripts, which were reviewed for accuracy. Participants received $20 honoraria. After conducting 7 focus groups, the research team determined that information power was achieved, and recruitment ended (Patton, 2002).

Transcripts were independently reviewed by a multidisciplinary team of three researchers, including a movement disorders specialist (N.B.), a clinical social worker (J.S.), and a qualitative methods expert (S.G.), to identify emerging concepts related to hospital experiences. During the first phase of analysis, two investigators (N.B. and S.G.) independently read 3 transcripts before convening to define initial topics/concepts and develop a preliminary codebook. Coded data and transcripts were maintained in an electronic database, MAXQDA 2020 (VERBI software, 2019). An inductive thematic approach was used for analysis. The respective coded transcripts were compared during face-to-face meetings (N.B. and S.G.) to assess similarities and discrepancies regarding code names and code application. Based on these consensus meetings, researchers developed a final codebook that was systematically applied to the remaining transcripts. The team continued to review and code transcripts independently, meeting regularly to collaboratively discuss coding decisions and to resolve any coding differences through consensus. All coded transcripts were then reviewed by a third researcher (J.S.) to ensure consistency (Busetto et al., 2020). The varied perspectives of team members yielded a nuanced and robust interpretation of the results and all discrepancies among analysts were resolved. The research team (N.B., J.S., P.M.) analyzed each code and assessed conceptual relationships among them to develop higher-level categories and the relevant sub-themes within each category (Table 2). The findings were then condensed, and conclusions drawn.

Seven focus groups were conducted. Participants included 12 PwPs (69% in the 65–74 age range and 28% non-white) and 13 CPs, including five PwP-CP dyads, for a total of 25 participants (Table 1). 84% of participants had unplanned hospitalizations and 64% of participants had lived with the PD diagnosis between 6 and 14 years at the time of hospitalization. All CPs reported unplanned hospitalizations of their loved one with PD. Ten participants were hospitalized at academic medical centers. During recruitment, participants were identified by their roles in the healthcare system (patient vs. family CP). Initially, the researches planned to create homogenic focus groups that thought would facilitate open discussion (Kaiser, 2009). However, during the recruitment, several PwPs in more advanced diseases stages expressed a preference for their CPs to be present during focus group and help navigate challenges with speech or slower processing speed, which made it difficult for them to fully participate in the discussion. In these PwP – CP dyads, the CP commonly participated in discussion by either voicing their own opinion about hospitalization or helping the PwP express their thoughts, thus playing the role of “patient’s voice.” The study included two focus groups consisting solely of CPs, one focus group with only PwPs, and the remaining four focus groups had a mix of participants (Table 3).

The focus group discussions revealed rich descriptive and thematic data, however, this paper focuses on two specific categories: the impact of the PD diagnosis on the patient and family’s hospital experiences and perceptions of care, and the emergence of distinctive needs of PwPs and CPs during hospitalization.

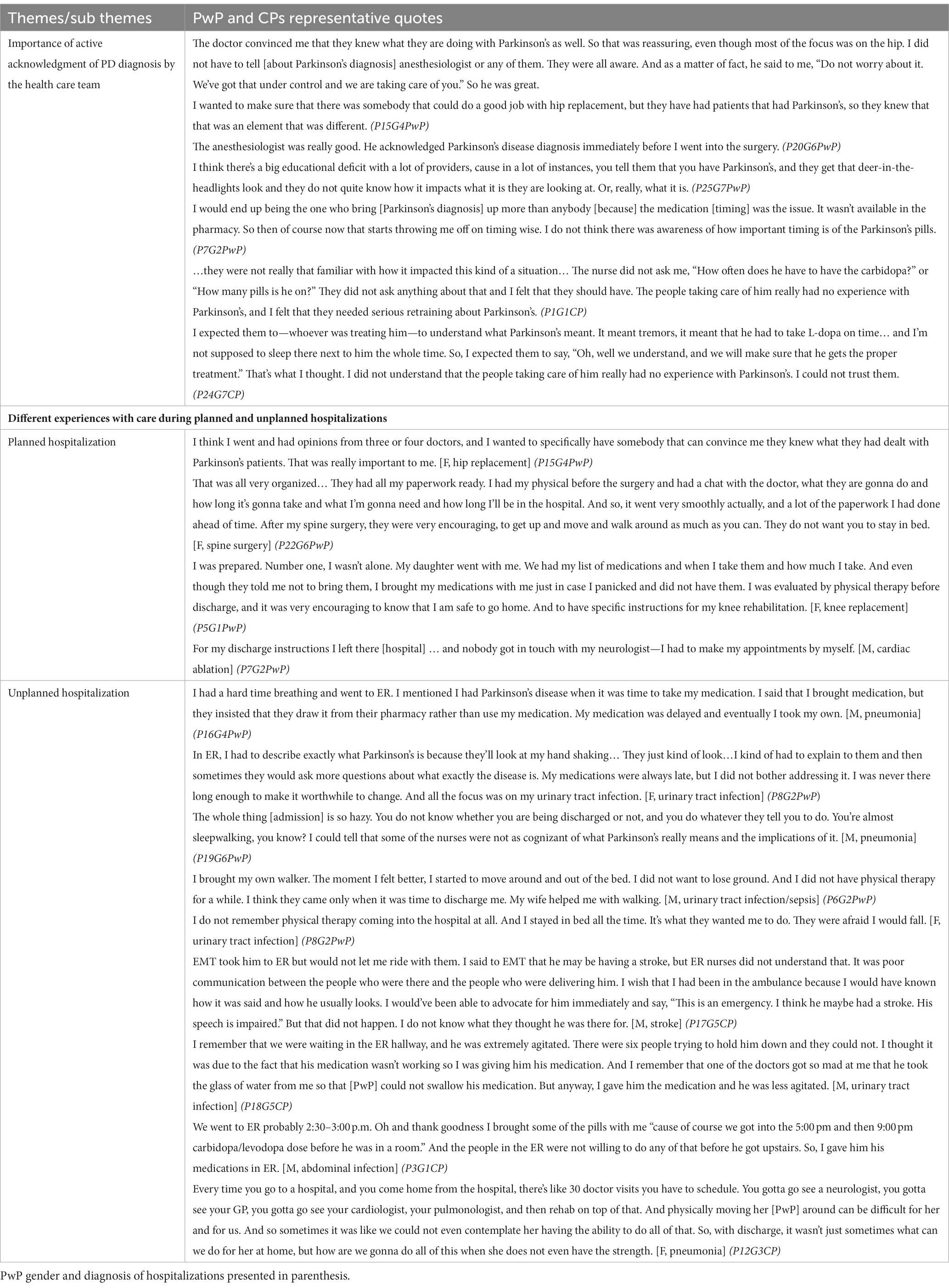

Tables 4, 5 present the sub-themes and themes accompanied by the focus group participants’ representative quotes. Each quote is marked with participant number (P#), focus group number (G#), and whether the participant identified as PwP or CP.

In the following section, we outline the major themes of each category.

1. Pre-existing PD diagnosis affected participants’ hospital experience and perception of care: “They acknowledged [PD] immediately… that was great!”

1.1. Acknowledgment of PD diagnosis by the health care team was important to participants.

Table 4. The impact of PD diagnosis on the hospital experience and perception of care among PwP and CPs with representative quotes.

Although none of the participants’ hospitalizations was directly related to PD symptoms, the presence of a PD diagnosis and whether the health care team (HCT) actively acknowledged the PD diagnosis had a significant impact on the perceptions of care of both for the PwPs and CPs. In both planned and unplanned hospitalizations, trust in the HCT was immediately gained when the team openly acknowledged the patient’s diagnosis of PD and demonstrated knowledge about specific considerations during hospital stays, anesthesia, and post-hospitalization rehabilitation.

1.2. Hospitalization experience differed according to whether hospitalizations were planned or unplanned.

Overall, the participants’ experiences with planned hospitalization were positive starting from the ability to choose their HCT with previous experience in PD care.

“That was really important to me. I wanted to make sure that there was somebody that could do a good job with hip replacement but they have had patients that had Parkinson’s, so they knew that that was an element that was different.” (P15G4PwP).

PwP chose the date of their planned hospitalization to ensure the presence of CP during the hospital stay and after the discharge: “And so I actually chose that particular surgery time so that I knew my daughter would be around… It was at Christmas time and… She is a teacher, and she was actually off for the next two and a half weeks.” (P5G1PwP).

During planned hospitalizations, PwPs had support from the rehabilitation services, and were given precise discharge instructions regarding the primary cause of hospitalization. Still, participants admitted to struggling to maintain the timing of their PD medication dosage during the hospital stay and their discharge instructions did not reference their diagnosis of PD.

In contrast, unplanned hospitalizations were described as “chaotic,” requiring quick decision-making from either PwPs or CPs on whether an ER visit was warranted. For those with unplanned hospitalizations, not one participant mentioned that they had a plan for contacting their neurologist or primary care physician. PwPs and CPs from multiple focus groups commented on delayed access to PD medications in the ER as well as perceived challenges with care delivery (e.g., HCT ability to perform intravenous cannulation placement or chest X-ray) due to prominent PD symptoms such as tremor. CPs were active participants in the decision to go to the hospital for unplanned hospitalizations, and in some cases, drove PwP to the ER. At the ER and once admitted, CP played an essential role in describing the usual state of health of the PwP and helped communicate any changes in their symptoms from baseline to the HCT.

2. The presence of PD-specific care needs posed an additional challenge for participants during hospitalization: “I expect them to be aware of the fact that I’m different.”

Specific needs affecting the experience from admission to discharge were identified, including knowledge of PD medications, proper medication management, improved hospital ambulation protocols, and preservation of independence in the hospital environment.

2.1. Numerous hurdles with PD medications management lead to dissatisfaction with hospital care among the participants.

Prior to any type of hospitalization, across all focus groups, PwPs and CPs were concerned about the availability of PD medications and, as a result, packed and brought their medications to the hospital. All participants reported issues with consistent and timely delivery of PD medications at all stages of hospitalization, from admission to discharge. For some, medications were substituted or re-arranged without explanation, which created mistrust toward HCT.

“They were giving me different looking medications that they assured me was the same thing, just a different manufacturer or whatever it was. Every time they gave me something and I looked at it and questioned it. … it was very disconcerting for me.” (P22G6PwP).

Most participants reported needing to have continuous discussions about their medication regimens with their care team. Trust in the HCT further eroded when the PwP perceived that the team lacked knowledge of commonly used medications for PD.

“Everyone had a general understanding of Parkinson’s, but not what I would consider, really, decent depth. And especially when it came to the medication, that was a tangible way of judging [the team]- that was something that had to happen and they needed to understand why it was important.” (P26G7PwP).

To ensure the correct medications were taken on time and as prescribed, many PwPs and CPs chose to administer their own medications during hospitalization. This was accomplished with or without nursing staff awareness. One CP explained: “I did not trust them to give it to him, so I wanted to give him his pills.” (P24G7CP) While acknowledging possible limitations, many participants expressed a desire to see protocols around medication self-administration in the hospital. As one participant shared: “I wish there was a way for patients who are self-aware to be able to be more self-dosing while they are in the hospital, with some limit per day. They often know their needs better than any staff can.” (P16G4PwP).

2.2. The restrictive nature of the hospital fall prevention protocols, along with dissuasion of ambulation, was discordant to participants needs to maintain mobility in the hospital.

Participants who experienced planned hospitalizations for orthopedic issues received prompt postoperative physical therapy (PT) with encouragement for daily ambulation. However, during unplanned hospitalizations, PwPs struggled to advocate for their ambulation needs and reported limited or no evaluation by PT and decreased mobility due to bed confinement. While CPs were commonly present at the bedsides of PwP, they were unsuccessful in advocating for more physical activity. In all focus groups, both PwPs and CPs remarked that the immobility of the PwP was not a concern for HCT. While some participants actively advocated for more physical activity and an assessment by a PT during their hospital stay, others did not, but still expressed their concerns during their focus group.

There were multiple PwPs with good postural stability and no history of falls who were deemed to be a “fall risk” during their hospitalization. “It was kind of funny that as soon as I said ‘Parkinson’s’ they put a tag on my hand saying that I have fall risk. So, after that, they would not let me get off the bed by myself, even though I was able to walk.” (P16G4PwP) The discrepancy between PwP needs to maintain mobility in the hospital, and the restrictive nature of the hospital fall prevention protocol, along with dissuasion of ambulation, was unsettling to the patients. “They had me in lockdown mode because I was the fall risk… I would just attempt to escape from Alcatraz.” (P25G7PwP) While participants acknowledged fall prevention as an important aspect of hospitalization, not many PwPs mentioned success in their advocacy to the HCT to revert fall prevention protocols despite obvious distress that such protocols created during their hospital stay.

2.3. Hospital environment was not accommodating toward participants’ existing motor and non-motor limitations, indicating the need for disability-informed hospital environment.

Both CP and PwP participants reported feeling that PwP’s sense of independence was significantly altered in the hospital. They described the impact of poor fine motor control (due to bradykinesia or tremor) on PwP’s ability to attend to daily tasks, such as eating and preferring finger foods on the menu, drinking from half-filled glasses to prevent spillage, and requiring assistance with managing urinals or pushing buttons on bed controls. Both PwPs and HCT preferred CPs to be at the bedside to aid in communication related to PD (e.g., low volume of voice, cognitive issues), although many CPs commented on the lack of accommodations for them, including limited space at the bedside or uncomfortable chairs. Some participants described significantly interrupted night sleep due to vital signs assessments, hearing conversations at the nursing station, or being awakened early to take morning medications. Some CPs observed that sleep interruptions created subsequent confusion and delirium and negatively affected the hospital experience for PwPs. Notwithstanding the reason for hospitalization, when accommodations for PD-specific care needs were included in hospital care, the experience was perceived by PwPs and CPs as more positive than when accommodations were excluded.

Our study used an innovative approach to define care needs of PwPs and CPs in the inpatient setting. By gathering first-hand experiences from direct stakeholders, we used qualitative and patient-centered methods to define the challenges and opportunities for improving hospitalization for PD. Thematic analysis revealed unique needs of PwPs and CPs while in the hospital, including the desire for individualized treatment plans and approaches, and the impact of the PD diagnosis on the perception of care during hospitalization.

Consistent with previous literature, the timely provision of PD medications was a key factor in the experience of and satisfaction with care for participants (Barber et al., 2001; Burroughs et al., 2007; Gerlach et al., 2011). In a systematic review examining the prevalence of adverse events related to medication errors, 31% of PwPs expressed dissatisfaction in the way their PD was managed (Gerlach et al., 2011). A more recent study focusing on motor outcomes identified medication errors as the most important factor in motor deterioration during hospitalization (Gerlach et al., 2013). Owing to challenges with medications in the hospital, most participants in our study proceeded with or desired medication self–management. Studies in other patient populations demonstrated the benefits of carefully applying validated medication self–administration protocols during hospitalization and after discharge (Manias et al., 2006; Vanwesemael et al., 2018a,b). The potential benefits and barriers to PD medication self-administration have been explored in outpatient settings; however, no study to date has assessed attitudes toward inpatient medication self-management in the PD population (Tuijt et al., 2020; Armstrong et al., 2021). Strategic and evidence-based medication self-management protocols for PwPs in the early stages or with support of CPs could empower PwPs and CPs and alleviate the workload on hospital staff.

Participants highlighted an important opportunity to improve PCC through individualized assessment of fall risk and flexibility in fall prevention protocols. To our knowledge, the study of falls and fall prevention protocols in hospitalized PwPs does not exist, even though gait and balance deficits were found in 41% of hospitalized PD patients, and prospective studies documented falls in up to 70% of PwPs (Wood et al., 2002; Bernhard et al., 2018). In older adults, a multidisciplinary and patient-centered approach to the development and implementation of hospital fall prevention protocols has been beneficial and could serve as a roadmap for similar quality improvement initiatives for PwPs (Covinsky et al., 2011; Hempel et al., 2013; Matarese et al., 2015). Participants in our study also strongly advocated for safe mobilization and early assessment by rehabilitation therapists during their hospital stay because of their fear or the reality of worsening PD motor symptoms due to immobility. Although there is a lack of literature on the safety and feasibility of early mobilization for hospitalized PwPs on general wards, studies show the benefits of early mobilization after surgery in PD (Macaulay et al., 2010; Schroeder et al., 2015). Walking during hospitalization is effective for older adults, promoting mobility, shortening hospital stays, and increasing likelihood of discharge to home (Hastings et al., 2018). Interventions to encourage mobility in this population show promise in preventing hospital-associated functional decline and maintaining prehospitalization mobility (Wassar Kirk et al., 2018; Cohen et al., 2019; Resnick and Boltz, 2019). Reported barriers to physical activity during hospitalization include insufficient staffing to assist with or encourage mobility, illness symptoms, fear of falls, and a discouraging hospital environment (Brown et al., 2007; Boltz et al., 2011; Koenders et al., 2020). Our study participants alluded to similar barriers to mobilization during their hospital stays. In addition to further research on fall prevention protocols for hospitalized PwPs, identifying patients with low fall risk and encouraging safe ambulation could be the first step to translate the well-established benefits of sustained mobility from outpatient to inpatient care for PD and to empower PwPs and CPs during hospitalization (Ellis et al., 2021).

In our study, nearly two-thirds of participants lived with the PD diagnosis for more than 6 years, and 84% experienced unplanned hospitalizations, emphasizing the complexity of care in the mid- and later stages of PD. The participants’ descriptions of challenges with navigating the hospital environment, including but not limited to tremor preventing the ease of intravenous cannulation placement, difficulty picking up and swallowing food that was served, and using hospital equipment like nurse call buttons, were not anticipated by the researchers when this study was designed. These PD-related challenges point to the hidden impact of hospitalization on one’s sense of independence. In addition, many CPs mentioned worsening of cognitive function or the development of delirium in PwPs while hospitalized. Our study methods precluded us from identifying specific practices implemented for delirium prevention; however, participants in multiple focus groups mentioned poor sleep protection for PwP during hospitalization. This was similar for CPs, who left the hospital feeling exhausted from reportedly sitting in uncomfortable chairs, monitoring and speaking for their PwP, and continuing to care for their partners once discharged home. Patients diagnosed with PD are fivefold more likely to be treated for delirium than patients from the general population, which may be related to non-motor symptoms in PD, such as dementia, cognitive impairment, and sleep disturbances (Figueroa-Ramos et al., 2009; Stavitsky et al., 2012; Lubomski et al., 2015). Since hospitalization places older adults and PwPs alike at risk for new or worsening disability and reduces likelihood of recovery, several successful interventions have been employed to modify hospital environment and improve patient experience and outcomes (Covinsky et al., 2011; Cohen et al., 2019; Resnick and Boltz, 2019; de Foubert et al., 2021). The hospital environment has a significant impact on patient satisfaction with care, and thus, it could be beneficial to develop and adopt customized hospital accommodations for PwPs to optimize outcomes and decrease risk of complications (Skelly et al., 2014; Rapport et al., 2019).

When patients with chronic conditions are admitted to the hospital, they are expected to switch from being the leader of their own care to being a passive consumer who resumes self-management only upon discharge. Consequently, during hospitalization, the combined stress of acute and chronic illness, set against the background of ongoing pressure to advocate for their unique needs, may be all-consuming for PwPs and CPs. Yet, this can be easily overlooked by HCTs as they are focused on medical management of the acute condition that caused hospitalization. In our study, PwPs and CPs sought active acknowledgement of PD diagnosis by their HCT and adjustment of the hospital communications, protocols or even environment, all of which underscore the impact of PD diagnosis on their perceptions of and experiences with inpatient care. Chronic care advocates argue that hospitals will continue to play a key role in chronic disease care, despite how many acute hospitalizations can be avoided, as most chronic conditions are characterized by acute exacerbations requiring admission (Hernandez et al., 2009; De Regge et al., 2017). Innovative care delivery models, such as the Chronic Care Model, recognize the importance of better preparing hospitals for a role in chronic illness management and demonstrate positive outcomes associated with specialized knowledge of PD among inpatient HCTs (Skelly et al., 2015; Siu et al., 2017). Thus, key findings from our study support acknowledging and accommodating the intersectional needs between the chronic condition of PD and the acute reason for hospitalization of the PwP.

The strength of our study is the use of purposeful sampling, a technique widely used in qualitative research, to identify and select information-rich cases for the most effective use of limited resources (Patton, 2002). Purposive sampling allowed us to identify and select individuals in different stages of PD and ensure that we would capture maximum variation of hospitalization experiences. Qualitative analysis can reveal themes in the data that otherwise may be difficult to identify using quantitative approaches. Focus groups, as a qualitative method, carried an additional strength by creating information—rich data. Focus groups allowed people to discuss the relevant topics with other PwPs and CPs using their own language, to build upon each other’s accounts and promoted “memory synergy,” bringing forth a “collective memory” of varied perspectives on similar experiences during hospitalization (Kamberelis and Dimitriadis, 2013). One of the limitations of our study is that we were unable to recruit CPs who experienced planned hospitalizations with their PwP, and, as a result, this perspective was not represented in our focus groups. Our sample was largely white, despite having intentionally expanded our recruitment efforts to include PwPs and CPs from diverse demographic backgrounds. Racial and ethnic differences in diagnosis, care experiences, and treatment utilization with PD are well known (Ben-Joseph et al., 2020). Therefore, the findings from this study likely cannot be generalized to the overall PD population and must be further validated in people with varied racial, ethnic, socioeconomic, and clinical backgrounds. Because the focus groups occurred months after their hospital stays, participants’ reports were subject to recall bias, and their nonclinical knowledge may have restricted their abilities to identify all factors impacting their hospitalizations. Despite the fact that some of the focus group participants were hospitalized during the COVID-19 pandemic, the discussion did not elucidate robust comments to draw any conclusions about the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on their experience with hospital care. Despite these limitations, this study provided a novel opportunity for PwPs and CPs to describe their own realities of their hospitalization experiences.

Our study adds to the canon of literature on hospital care for PD. Still, several concepts brought forth by this study warrant further exploration. There is an opportunity to further investigate the role and impact of advocacy by PwPs and CPs on healthcare delivery, as well as explore methodology to capture the real-time experiences of PwPs and CPs during hospitalization, as has been accomplished in other medical conditions (Gualandi et al., 2021). Additionally, the methods and findings of this study serve as good starting points for understanding the hospital experiences of those with atypical parkinsonian syndromes, including progressive supranuclear palsy and multiple system atrophy, given the complexity of symptoms, rapid disease progression, profound lack of awareness of these rarer neurodegenerative diagnoses within the medical community, and the current dearth of research on hospital care for atypical parkinsonism (Dayal et al., 2017; O’shea et al., 2023).

Our qualitative study draws attention to the significant impact a PD diagnosis can have on planned and unplanned hospital stays, even when the reason for care is not directly related to PD. It highlights the plethora of unique needs PwPs and their CPs have during hospitalization. Findings from this study can be used to inform patient-centered interventions aimed at improving the experience with hospital care for PD, including tools that help PwPs prepare for and advocate during hospitalization as well as ensuring flexibility, as appropriate, within hospital protocols. Empowering PwPs and CPs to communicate their questions, concerns, goals, and needs, both generally and regarding PD, with HCT in the hospital setting, thus applying the principles of PCC, could lead to the care they desire and set them up for higher likelihood of positive outcomes following hospitalization.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving humans were approved by the Office of Human Research Ethics the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The ethics committee/institutional review board waived the requirement of written informed consent for participation from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin because the research was deemed to have no more than minimal risk of harm to subjects and involves no procedures for which written consent is normally required outside of the research context (e.g., many phone or mail surveys, “man in the street” interviews, etc.).

NB: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Validation. JS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Methodology, Writing – original draft. SG: Data curation, Methodology, Software, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Validation. PM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Supervision.

The study was supported by Parkinson’s Foundation Community Outreach Resource Education grant PF-CORE-2008 and Parkinson’s Foundation Center of Excellence Award PF-COE-929858.

We extend our deepest appreciation to each and every study participant. Their altruistic contribution and willingness to share their experiences has been invaluable in advancing our understanding of PD care during hospitalization and ultimately enhancing the lives of the entire community.

JS is currently employed by the CurePSP Foundation, although at the time of the study, she was working at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnagi.2023.1255428/full#supplementary-material

Aminoff, M. J., Christine, C. W., Friedman, J. H., Chou, K. L., Lyons, K. E., Pahwa, R., et al. (2011). Management of the hospitalized patient with Parkinson’s disease: current state of the field and need for guidelines. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 17, 139–145. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2010.11.009

Armstrong, M., Tuijt, R., Read, J., Pigott, J., Davies, N., Manthorpe, J., et al. (2021). Health care professionals’ perspectives on self-management for people with Parkinson’s: qualitative findings from a UK study. BMC Geriatr. 21:706. doi: 10.1186/s12877-021-02678-w

Aslam, S., Simpson, E., Baugh, M., and Shill, H. (2020). Clinical Practice. Neurology 10, 23–28. doi: 10.1212/CPJ.0000000000000709

Azmi, H., Cocoziello, L., Harvey, R., McGee, M., Desai, N., Thomas, J., et al. (2019). Development of a joint commission disease-specific care certification program for Parkinson disease in an acute care hospital. J. Neurosci. Nurs. 51, 313–319. doi: 10.1097/JNN.0000000000000472

Azmi, H., Cocoziello, L., Nyirenda, T., Douglas, C., Jacob, B., Thomas, J., et al. (2020). Adherence to a strict medication protocol can reduce length of stay in hospitalized patients with Parkinson’s disease. Clin. Park. Relat. Disord. :3. doi: 10.1016/J.PRDOA.2020.100076

Barber, M., Stewart, D., Grosset, D., and MacPhee, G. (2001). Patient and carer perception of the management of Parkinson disease after surgery. Age Ageing 30, 171–172. doi: 10.1093/ageing/30.2.171-a

Ben-Joseph, A., Marshall, C. R., Lees, A. J., and Noyce, A. J. (2020). Ethnic variation in the manifestation of Parkinson’s disease: a narrative review. J. Parkinsons Dis. 10, 31–45. doi: 10.3233/JPD-191763

Bernhard, F. P., Sartor, J., Bettecken, K., Hobert, M. A., Arnold, C., Weber, Y. G., et al. (2018). Wearables for gait and balance assessment in the neurological ward - study design and first results of a prospective cross-sectional feasibility study with 384 inpatients. BMC Neurol. 18:114. doi: 10.1186/s12883-018-1111-7

Berwick, D. M. (2009). What “patient-centered” should mean: confessions of an extremist. Health Aff. 28, w555–w565. doi: 10.1377/HLTHAFF.28.4.W555

Bhidayasiri, R., Panyakaew, P., Trenkwalder, C., Jeon, B., Hattori, N., Jagota, P., et al. (2020). Delivering patient-centered care in Parkinson’s disease: challenges and consensus from an international panel. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 72, 82–87. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2020.02.013

Boltz, M., Capezuti, E., and Shabbat, N. (2011). Nursing staff perceptions of physical function in hospitalized older adults. Appl. Nurs. Res. 24, 215–222. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2010.01.001

Braga, M., Pederzoli, M., Antonini, A., Beretta, F., and Crespi, V. (2014). Reasons for hospitalization in Parkinson’s disease: a case-control study. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 20, 488–492. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2014.01.022

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2012). “Thematic analysis” in APA handbook of research methods in psychology, Vol 2: research designs: quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological, and biological, 57–71.

Brown, C. J., Williams, B. R., Woodby, L. L., Davis, L. L., and Allman, R. M. (2007). Barriers to mobility during hospitalization from the perspectives of older patients and their nurses and physicians. J. Hosp. Med. 2, 305–313. doi: 10.1002/jhm.209

Buetow, S., Henshaw, J., Bryant, L., and O’sullivan, D. (2009). Medication timing errors for Parkinson’s disease: perspectives held by caregivers and people with Parkinson’s in New Zealand. Parkinson Dis. 2010:432983. doi: 10.4061/2010/432983

Burroughs, T. E., Waterman, A. D., Gallagher, T. H., Waterman, B., Jeffe, D. B., Dunagan, W. C., et al. (2007). Patients’ concerns about medical errors during hospitalization. Jt. Comm. J. Qual. Patient Saf. 33, 5–14. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(07)33002-x

Busetto, L., Wick, W., and Gumbinger, C. (2020). How to use and assess qualitative research methods. Neurol. Res. Pract. 2, 1–10. doi: 10.1186/s42466-020-00059-z

Carney Anderson, L., and Fagerlund, K. (2013). Original research: The perioperative experience of patients with Parkinson’s disease: a qualitative study. Am. J. Nurs. 113, 26–32. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000426686.84655.4a

Chou, K. L., Zamudio, J., Schmidt, P., Price, C. C., Parashos, S. A., Bloem, B. R., et al. (2011). Hospitalization in Parkinson disease: a survey of National Parkinson Foundation centers. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 17:440. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2011.03.002

Cohen, Y., Zisberg, A., Chayat, Y., Gur-Yaish, N., Gil, E., Levin, C., et al. (2019). Walking for better outcomes and recovery: the effect of WALK-FOR in preventing hospital-associated functional decline among older adults. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 74, 1664–1670. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glz025

Connor, K. I., Cheng, E. M., Barry, F., Siebens, H. C., Lee, M. L., Ganz, D. A., et al. (2019). Randomized trial of care management to improve Parkinson disease care quality a nurse-led model increases quality of care in Parkinson disease criteria for rating therapeutic and diagnostic studies. Neurology 92, e1831–e1842. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007324

Counsell, S. R., Holder, C. M., Liebenauer, L. L., Palmer, R. M., Fortinsky, R. H., Kresevic, D. M., et al. (2000). Effects of a multicomponent intervention on functional outcomes and process of care in hospitalized older patients: a randomized controlled trial of acute Care for Elders (ACE) in a community hospital. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 48, 1572–1581. doi: 10.1111/J.1532-5415.2000.TB03866.X

Covinsky, K. E., Pierluissi, E., and Johnston, C. B. (2011). Hospitalization-associated disability “she was probably able to ambulate, but I’m not sure”. JAMA 306, 1782–1793. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1556

Dayal, A. M., Jenkins, M. E., Jog, M. S., Kimpinski, K., Macdonald, P., and Gofton, T. E. (2017). Palliative care discussions in multiple system atrophy: a retrospective review. Can. J. Neurol. Sci. 44, 276–282. doi: 10.1017/cjn.2016.439

de Foubert, M., Cummins, H., McCullagh, R., Brueton, V., and Naughton, C. (2021). Systematic review of interventions targeting fundamental care to reduce hospital-associated decline in older patients. J. Adv. Nurs. 77, 4661–4678. doi: 10.1111/jan.14954

De Regge, M., De Pourcq, K., Meijboom, B., Trybou, J., Mortier, E., and Eeckloo, K. (2017). The role of hospitals in bridging the care continuum: a systematic review of coordination of care and follow-up for adults with chronic conditions. BMC Health Serv. Res. 17, 1–24. doi: 10.1186/S12913-017-2500-0/TABLES/4

Derry, C. P., Shah, K. J., Caie, L., and Counsell, C. E. (2010). Medication management in people with Parkinson’s disease during surgical admissions. Postgrad. Med. J. 86, 334–337. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2009.080432

Eggers, C., Dano, R., Schill, J., Fink, G., Hellmich, M., and Timmermann, L. (2018). Patient-centered integrated healthcare improves quality of life in Parkinson’s disease patients: a randomized controlled trial on behalf of the CPN study group. J. Neurol. 265, 764–773. doi: 10.1007/s00415-018-8761-7

Ellis, T. D., Colón-Semenza, C., Deangelis, T. R., Thomas, C. A., Hilaire, M.-H. S., Earhart, G. M., et al. (2021). Evidence for early and regular physical therapy and exercise in Parkinson’s disease. Semin. Neurol. 41, 189–205. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1725133

Figueroa-Ramos, M. I., Arroyo-Novoa, C. M., Lee, K. A., Padilla, G., and Puntillo, K. A. (2009). Sleep and delirium in ICU patients: a review of mechanisms and manifestations. Intensive Care Med. 35, 781–795. doi: 10.1007/s00134-009-1397-4

Gerlach, O. H. H., Broen, M. P. G., van Domburg, P. H. M. F., Vermeij, A. J., and Weber, W. E. J. (2012). Deterioration of Parkinson’s disease during hospitalization: survey of 684 patients. BMC Neurol. 12, 1–6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-12-13/TABLES/2

Gerlach, O. H. H., Broen, M. P. G., and Weber, W. E. J. (2013). Motor outcomes during hospitalization in Parkinson’s disease patients: a prospective study. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 19, 737–741. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2013.04.017

Gerlach, O. H., Winogrodzka, A., and Weber, W. E. (2011). Clinical problems in the hospitalized Parkinson’s disease patient: systematic review. Mov. Disord. 26, 197–208. doi: 10.1002/mds.23449

Gil-Prieto, R., Pascual-Garcia, R., San-Roman-Montero, J., Martinez-Martin, P., Castrodeza-Sanz, J., and Gil-De-Miguel, A. (2016). Measuring the burden of hospitalization in patients with Parkinson’s disease in Spain. PLoS One 11:e0151563. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151563

Goetz, C. G., Poewe, W., Rascol, O., Sampaio, C., Stebbins, G. T., Counsell, C., et al. (2004). Movement Disorder Society task force report on the Hoehn and Yahr staging scale: status and recommendations. Mov. Disord. 19, 1020–1028. doi: 10.1002/mds.20213

Gualandi, R., Masella, C., Piredda, M., Ercoli, M., and Tartaglini, D. (2021). What does the patient have to say? Valuing the patient experience to improve the patient journey. BMC Health Serv. Res. 21. doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-06341-3

Guest, G., Bunce, A., and Johnson, L. (2006). How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods 18, 59–82. doi: 10.1177/1525822X05279903

Hastings, S. N., Choate, A. L., Mahanna, E. P., Floegel, T. A., Allen, K. D., Van Houtven, C. H., et al. (2018). Early mobility in the hospital: lessons learned from the STRIDE program. Geriatrics (Basel) 3:61. doi: 10.3390/geriatrics3040061

Hempel, S., Newberry, S., Wang, Z., Booth, M., Shanman, R., Johnsen, B., et al. (2013). Hospital fall prevention: a systematic review of implementation, components, adherence, and effectiveness. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 61, 483–494. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12169

Hernandez, C., Jansa, M., Vidal, M., Nuñez, M., Bertran, M. J., Garcia-Aymerich, J., et al. (2009). The burden of chronic disorders on hospital admissions prompts the need for new modalities of care: a cross-sectional analysis in a tertiary hospital. QJM 102, 193–202. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcn172

Hobson, D. E., Lix, L. M., Azimaee, M., Leslie, W. D., Burchill, C., and Hobson, S. (2012). Healthcare utilization in patients with Parkinson’s disease: a population-based analysis. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 18, 930–935. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2012.04.026

Hobson, P., Roberts, S., and Davies, G. (2019). The introduction of a Parkinson’s disease email alert system to allow for early specialist team review of inpatients. BMC Health Serv. Res. 19:271. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4092-3

Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. (2014), 360. Available at: http://europepmc.org/books/NBK222274 (Accessed February 12, 2023).

Francis, J. J., Johnston, M., Robertson, C., Glidewell, L., Entwistle, V., and Eccles, M. P. (2010). What is an adequate sample size? Operationalising data saturation for theory-based interview studies. Psychol. Health 25, 1229–1245. doi: 10.1080/08870440903194015

Kaiser, K. (2009). Protecting respondent confidentiality in qualitative research. Qual. Health Res. 19, 1632–1641. doi: 10.1177/1049732309350879

Kamberelis, G., and Dimitriadis, G. (2013). Focus groups: From structured interviews to collective conversations. London: Routledge.

Kiger, M. E., and Varpio, L. (2020). Thematic analysis of qualitative data: AMEE guide no. 131. Med. Teach. 42, 846–854. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2020.1755030

Kluger, B. M., Miyasaki, J., Katz, M., Galifianakis, N., Hall, K., Pantilat, S., et al. (2020). Comparison of integrated outpatient palliative care with standard Care in Patients with Parkinson Disease and Related Disorders: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 77, 551–560. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.4992

Koenders, N., van Oorsouw, R., Seeger, J. P. H., Nijhuis – van der Sanden, M. W. G., van de Glind, I., Hoogeboom, T. J., et al. (2020). “I’m not going to walk, just for the sake of walking…”: a qualitative, phenomenological study on physical activity during hospital stay. Disabil. Rehabil. 42, 78–85. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2018.1492636

Kowal, S. L., Dall, T. M., Chakrabarti, R., Storm, M. V., and Jain, A. (2013). The current and projected economic burden of Parkinson’s disease in the United States. Mov. Disord. 28, 311–318. doi: 10.1002/mds.25292

Lennaerts-Kats, H., Ebenau, A., Van Der Steen, J. T., Munneke, M., Bloem, B. R., Vissers, K. C. P., et al. (2022). “No one can tell me how Parkinson’s disease will unfold”: a mixed methods case study on palliative Care for People with Parkinson’s disease and their family caregivers. J. Parkinsons Dis. 12, 207–219. doi: 10.3233/JPD-212742

Lubomski, M., Rushworth, R. L., and Tisch, S. (2015). Hospitalisation and comorbidities in Parkinson’s disease: a large Australian retrospective study. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 86, 324–330. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2014-307822

Macaulay, W. M., Geller, J. A. M., Brown, A. R. M., Cote, L. J. M., and Kiernan, H. A. (2010). Total knee arthroplasty and Parkinson disease: enhancing outcomes and avoiding complications. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surgeon 18, 687–694. doi: 10.5435/00124635-201011000-00006

Magnuszewski, L., Wojszel, A., Kasiukiewicz, A., and Wojszel, Z. B. (2022). Falls at the geriatric hospital Ward in the context of risk factors of falling detected in a comprehensive geriatric assessment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19:10789. doi: 10.3390/ijerph191710789

Malterud, K., Siersma, V. D., and Guassora, A. D. (2016). Sample size in qualitative interview studies: guided by information power. Qual. Health Res. 26, 1753–1760. doi: 10.1177/1049732315617444

Manias, E., Beanland, C. J., Riley, R. G., and Hutchinson, A. M. (2006). Development and validation of the self-administration of medication tool. Ann. Pharmacother. 40, 1064–1073. doi: 10.1345/aph.1G677

Matarese, M., Ivziku, D., Bartolozzi, F., Piredda, M., and De Marinis, M. G. (2015). Systematic review of fall risk screening tools for older patients in acute hospitals. J. Adv. Nurs. 71, 1198–1209. doi: 10.1111/jan.12542

Nance, M. A., Boettcher, L., Edinger, G., Gardner, J., Kitzmann, R., Erickson, L. O., et al. (2020). Quality improvement in Parkinson’s disease: a successful program to enhance timely Administration of Levodopa in the hospital. J. Parkinsons Dis. 10, 1551–1559. doi: 10.3233/JPD-202024

O’shea, N., Lyons, S., Higgins, S., and O’dowd, S. (2023). Neurological update: the palliative care landscape for atypical parkinsonian syndromes. J. Neurol. 270, 2333–2341. doi: 10.1007/s00415-023-11574-9

Okunoye, O., Kojima, G., Marston, L., Walters, K., and Schrag, A. (2020). Factors associated with hospitalisation among people with Parkinson’s disease-a systematic review and meta-analysis. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 71, 66–72. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2020.02.018

Parkinson’s Foundation Hospital Safety Kits. (2023). Available at: https://www.parkinson.org/hospitalsafety.

Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research and evaluation methods. 3rd Edn. Los Angeles: Sage Publications.

Rajan, R., Brennan, L., Bloem, B. R., Dahodwala, N., Gardner, J., Goldman, J. G., et al. (2020). Integrated Care in Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Mov. Disord. 35, 1509–1531. doi: 10.1002/mds.28097

Rapport, F., Hibbert, P., Baysari, M., Long, J. C., Seah, R., Zheng, W. Y., et al. (2019). What do patients really want? An in-depth examination of patient experience in four Australian hospitals. BMC Health Serv. Res. 19:38. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-3881-z

Rathert, C., Wyrwich, M. D., and Boren, S. A. (2013). Patient-centered care and outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. Med. Care Res. Rev. 70, 351–379. doi: 10.1177/1077558712465774

Read, I. J., Cable, S., Lö Fqvist, C., Iwarsson, S., Bartl, G., and Schrag, A. (2019). Experiences of health services and unmet care needs of people with late-stage Parkinson’s in England: a qualitative study. PLoS One 4:e0226916. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0226916

Réa-Neto, Á., Dal Vesco, B. C., Bernardelli, R. S., Kametani, A. M., Oliveira, M. C., and Teive, H. A. G. (2021). Evaluation of patients with Parkinson’s disease in intensive care units: a cohort study. Parkinsons Dis. 2021:2948323. doi: 10.1155/2021/2948323

Resnick, B., and Boltz, M. (2019). Optimizing function and physical activity in hospitalized older adults to prevent functional decline and falls. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 35, 237–251. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2019.01.003

Rocco, N. M., Scher, K. R. C., Basberg, B. M. M., Yalamanchi, S. M., and Baker-Genaw, K. M. (2011). Patient-centered plan-of-care tool for improving clinical outcomes. Qual. Manag. Health Care 20, 89–97. doi: 10.1097/QMH.0b013e318213e728

Schroeder, J. E., Hughes, A., Sama, A., Weinstein, J., Kaplan, L., Cammisa, F. P., et al. (2015). Lumbar spine surgery in patients with Parkinson disease. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 97, 1661–1666. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.N.01049

Shahgholi, L., De Jesus, S., Wu, S. S., Pei, Q., Hassan, A., Armstrong, M. J., et al. (2017). Hospitalization and rehospitalization in Parkinson disease patients: data from the National Parkinson Foundation centers of excellence. PLoS One 12, 1–10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0180425

Siu, A. L., Spragens, L. H., Inouye, S. K., Morrison, R. S., and Leff, B. (2017). The ironic business case for chronic care in the acute care setting 28, 113–125. doi: 10.1377/HLTHAFF.28.1.113

Skelly, R., Brown, L., Fakis, A., Kimber, L., Downes, C., Lindop, F., et al. (2014). Does a specialist unit improve outcomes for hospitalized patients with Parkinson’s disease? Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 20, 1242–1247. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2014.09.015

Skelly, R., Brown, L., Fakis, A., and Walker, R. (2015). Hospitalization in Parkinson’s disease: a survey of UK neurologists, geriatricians and Parkinson’s disease nurse specialists. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 21, 277–281. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2014.12.029

Skelly, R., Brown, L., and Fogarty, A. (2017). Delayed administration of dopaminergic drugs is not associated with prolonged length of stay of hospitalized patients with Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 35, 25–29. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2016.11.004

Stavitsky, K., Neargarder, S., Bogdanova, Y., Mcnamara, P., and Cronin-Golomb, A. (2012). The impact of sleep quality on cognitive functioning in Parkinson’s disease. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 18, 108–117. doi: 10.1017/S1355617711001482

Su, C. M., Te, K. C., Chen, F. C., Cheng, H.-H., Hsiao, S.-Y., Lai, Y.-R., et al. (2018). Manifestations and outcomes of patients with Parkinson’s disease and serious infection in the emergency department. Biomed. Res. Int. 2018:6014896. doi: 10.1155/2018/6014896

Tuijt, R., Tan, A., Armstrong, M., Pigott, J., Read, J., Davies, N., et al. (2020). Self-management components as experienced by people with Parkinson’s disease and their Carers: a systematic review and synthesis of the qualitative literature. Parkinsons Dis. 2020:8857385. doi: 10.1155/2020/8857385

Vanwesemael, T., Boussery, K., Manias, E., Petrovic, M., Fraeyman, J., and Dilles, T. (2018a). Self-management of medication during hospitalisation: healthcare providers’ and patients’ perspectives. J. Clin. Nurs. 27, 753–768.

Vanwesemael, T., Dilles, T., Van Rompaey, B., and Boussery, K. (2018b). An evidence-based procedure for self-Management of Medication in hospital: development and validation of the SelfMED procedure. Pharmacy 6:77. doi: 10.3390/pharmacy6030077

Vlaanderen, F. P., Rompen, L., Munneke, M., Stoffer, M., Bloem, B. R., and Faber, M. J. (2019). The voice of the Parkinson customer. J. Parkinsons Dis. 9, 197–201. doi: 10.3233/JPD-181431

Wassar Kirk, J., Christine Bodilsen, A., Tjørnhøj-Thomsen, T., Pedersen, M. M., Bandholm, T., Husted, R. S., et al. (2018). A tailored strategy for designing the walk-Copenhagen (WALK-Cph) intervention to increase mobility in hospitalised older medical patients: a protocol for the qualitative part of the WALK-Cph project. BMJ Open 8:20272. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020272

Wolf, D. M., Lehman, L., Quinlin, R., Zullo, T., and Hoffman, L. (2008). Effect of patient-centered care on patient satisfaction and quality of care. J. Nurs. Care Qual. 23, 316–321. doi: 10.1097/01.NCQ.0000336672.02725.a5

Wood, B. H., Bilclough, J. A., and Bowron, A. (2002). Incidence and prediction of falls in Parkinson’s disease: a prospective multidisciplinary study. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 72, 721–725. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.72.6.721

Keywords: Parkinson’s disease, hospitalization, patient-centered care, qualitative methods, focus groups

Citation: Shurer J, Golden SLS, Mihas P and Browner N (2023) More than medications: a patient-centered assessment of Parkinson’s disease care needs during hospitalization. Front. Aging Neurosci. 15:1255428. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2023.1255428

Received: 08 July 2023; Accepted: 12 September 2023;

Published: 28 September 2023.

Edited by:

Hooman Azmi, Hackensack University Medical Center, United StatesReviewed by:

Ana Plácido, Instituto Politécnico da Guarda, PortugalCopyright © 2023 Shurer, Golden, Mihas and Browner. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nina Browner, YnJvd25lcm5AbmV1cm9sb2d5LnVuYy5lZHU=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.