95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Aging Neurosci. , 25 May 2023

Sec. Alzheimer's Disease and Related Dementias

Volume 15 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2023.1196185

Background and objective: Migraine is a common chronic neurological disease characterized by pulsating headaches, photophobia, phonophobia, nausea, and vomiting. The prevalence of dementia in individuals aged over 65 years in Korea is more than 10%, and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) dementia accounts for most cases. Although these two neurological diseases account for a large portion of the medical burden in Korea, few studies have examined the relationship between the two diseases. Therefore, this study investigated the incidence and risk of AD in patients with migraines.

Methods: We retrospectively collected nationwide data from a national health insurance claims database governed by Korea’s National Health Insurance Service. Among Koreans in the 2009 record, patients with migraine were identified according to the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10) code G43. First, we screened the database for participants aged over 40 years. Individuals diagnosed with migraine at least twice over more than 3 months in a year were considered to have chronic migraine in this study. Further, all participants with an AD diagnosis (ICD-10 code: Alzheimer’s disease F00, G30) were investigated for AD dementia development. The primary endpoint was AD development.

Results: The overall incidence of AD dementia was higher in individuals with a history of migraine than in those with no migraine history (8.0 per 1,000 person-years vs. 4.1 per 1,000 person-years). The risk of AD dementia was higher in individuals diagnosed with migraine (hazard ratio = 1.37 [95% confidence interval, 1.35–1.39]) than in the control group after adjustments for age and sex. Individuals with chronic migraine had a higher incidence of AD dementia than those with episodic migraine. Younger age (<65 years old) was associated with an increased risk of AD dementia compared to older age (≥65 years old). Higher body mass index (BMI) (≥25 kg/m2) was also associated with an increased risk of AD dementia compared to lower BMI (<25 kg/m2) (p < 0.001).

Conclusion: Our results suggest that individuals with a migraine history are more susceptible to AD than those without a migraine history. Additionally, these associations were more significant in younger and obese individuals with migraine than in individuals without migraine.

Migraine is a neurological disorder that causes symptoms such as headache, abdominal discomfort, vomiting, and visual impairment, affecting more than 10 billion people worldwide (Amiri et al., 2021). Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common cause of dementia, with more than 30 million people affected worldwide (Gustavsson et al., 2023). Female sex, old age, hypertension, diabetes, obesity, dyslipidemia, stress, and hormonal imbalance were considered risk factors for migraine (Giannini et al., 2012; Amiri et al., 2021). Old age, female sex, hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and obesity are well-known risk factors for AD (Leibson et al., 1997; Qiu et al., 2003; Reitz, 2013; Lloret et al., 2019; Ding et al., 2020). Although these two neurological diseases account for a large portion of the medical burden worldwide, few studies have examined their relationship.

Previous studies showed inconsistent results regarding the association between migraine and AD (Morton et al., 2019; George et al., 2020; Islamoska et al., 2020). However, more recent large-scale studies have reported that patients with migraine have a higher incidence of AD than those without migraine (Kostev et al., 2019; Lee et al., 2021). Regarding the association between dementia and migraine, several studies have suggested the existence of a relationship between white matter damage, depression, chronic pain, and stress (Jensen, 2003; Wang et al., 2018); however, there are few studies on the association according to common risk factors for migraine and dementia, especially AD.

Extensive research into the association between migraine and dementia could improve the diagnosis and treatment of these disorders that significantly affect patients’ quality of life. In the present study, we aimed to investigate the association between migraine and the incidence of AD dementia according to various risk factors.

We retrospectively collected nationwide data from a national health insurance claims database governed by Korea’s National Health Insurance Service (NHIS). Among 10,628,070 Koreans who participated in the national health screening program in 2009, individuals aged ≥40 years were eligible for inclusion in this study. We investigated the medical records of the eligible participants as obtained from the NHIS database during the period spanning from 2002 to 2019. The date of participation in the 2009 national health screening program was defined as the start date of the follow-up. The patients with migraine were identified according to the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10) code G43. Patients diagnosed with migraine at least twice over more than 3 months in a year were considered to have chronic migraine in this study.

All participants were investigated for AD development based on a positive AD diagnosis (ICD-10 code Alzheimer’s disease F00, G30) and their prescription records for anti-dementia medication. The primary endpoint was AD development. Participants with a previous AD diagnosis were excluded from the study. Participants were also excluded if they developed AD or died within 12 months of enrollment. The wash-out period of 12 months was used to minimize the possibility of reverse-causality. The study flowchart is presented in Supplementary Figure S1.

To investigate whether migraine affects the risk of AD, we calculated the hazard ratios (HR) and the associated 95% confidence intervals (CI) using the Cox proportional hazards model. We used three progressively adjusted models. Model 1 involved a crude analysis without any adjustment. Model 2 was adjusted for age and sex. In model 3, we adjusted age, sex, comorbidities, lifestyle factors (smoking, drinking, and physical exercise), eGFR, and BMI. Multivariate Cox regression analysis was used in subgroup analyses to assess the impact of underlying comorbidities or demographic characteristics on AD risk in individuals with migraine. All analyses were performed using the SAS statistical software (version 9.2; SAS Institute, Cary, NC, United States).

The demographic characteristics of the study participants are shown in Table 1. Female patients had a higher predominance of migraine than male patients (72.3% vs. 46.6%, p < 0.001). Hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, myocardial infarction, stroke, and congestive heart failure were significantly more predominant in patients with migraine than the participants without migraine (p < 0.001). Patients with migraine comprised a higher percentage of never smokers and non-drinkers than the participants without migraine (p < 0.001).

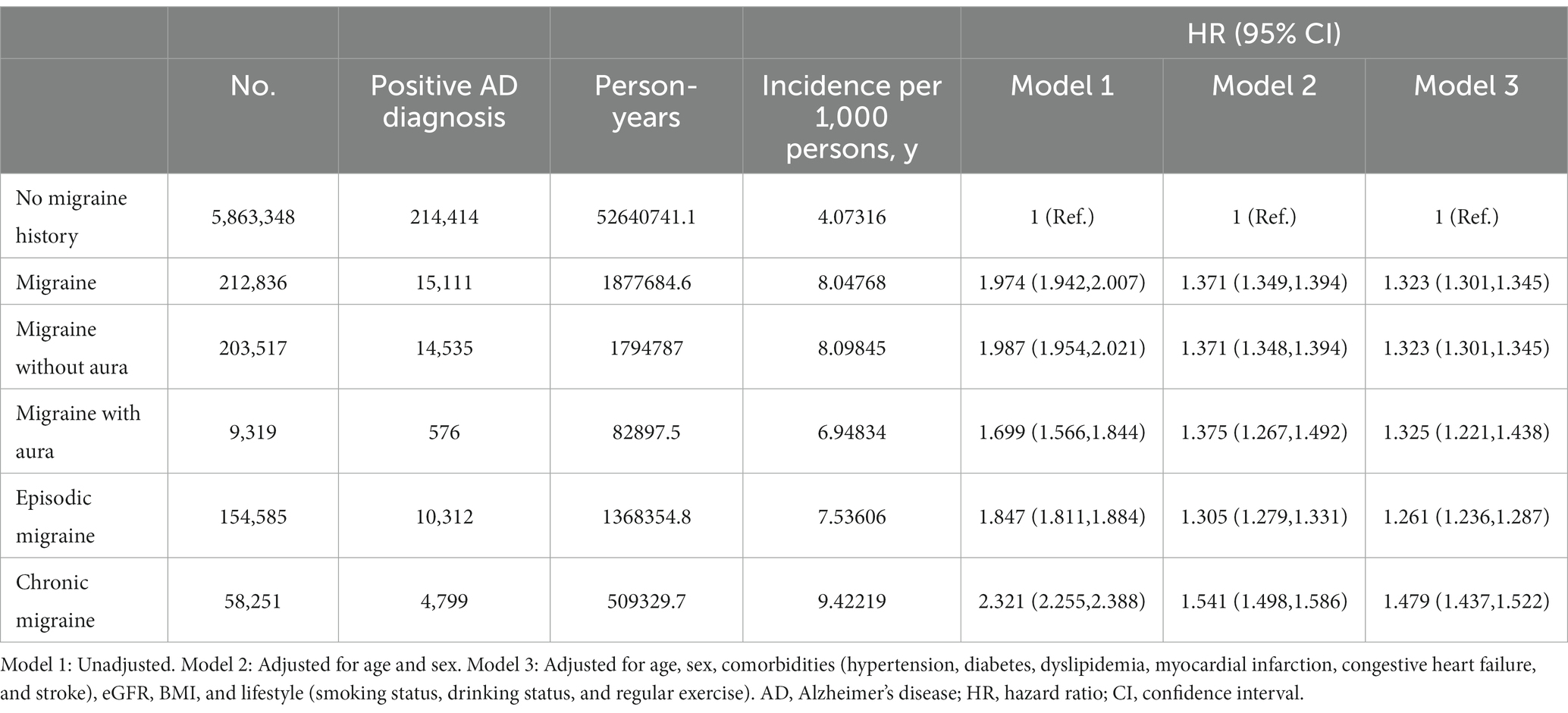

The overall incidence of AD in participants with no migraine history was 3.7% (214,414/5,863,348), whereas that in those with a migraine history was 7.1% (15,111/2,12,836) (Table 2), suggesting that migraine was related to the incidence of AD.

Table 2. Cox proportional hazard regression analysis of the risk of Alzheimer’s disease in participants with different types of migraine.

Cox proportional hazard regression analysis showed that patients with migraine developed AD with a 1.32 HR (95% CI, 1.30–1.35) compared to the participants with no migraine history after adjustments for age, sex, comorbidities, and lifestyle (Table 2). In the subgroup analysis, we observed that patients with chronic migraine had a higher HR of AD development than those with episodic migraine (HR = 1.48 [95% CI, 1.44–1.52] vs. HR = 1.26 [95% CI, 1.27–1.29]).

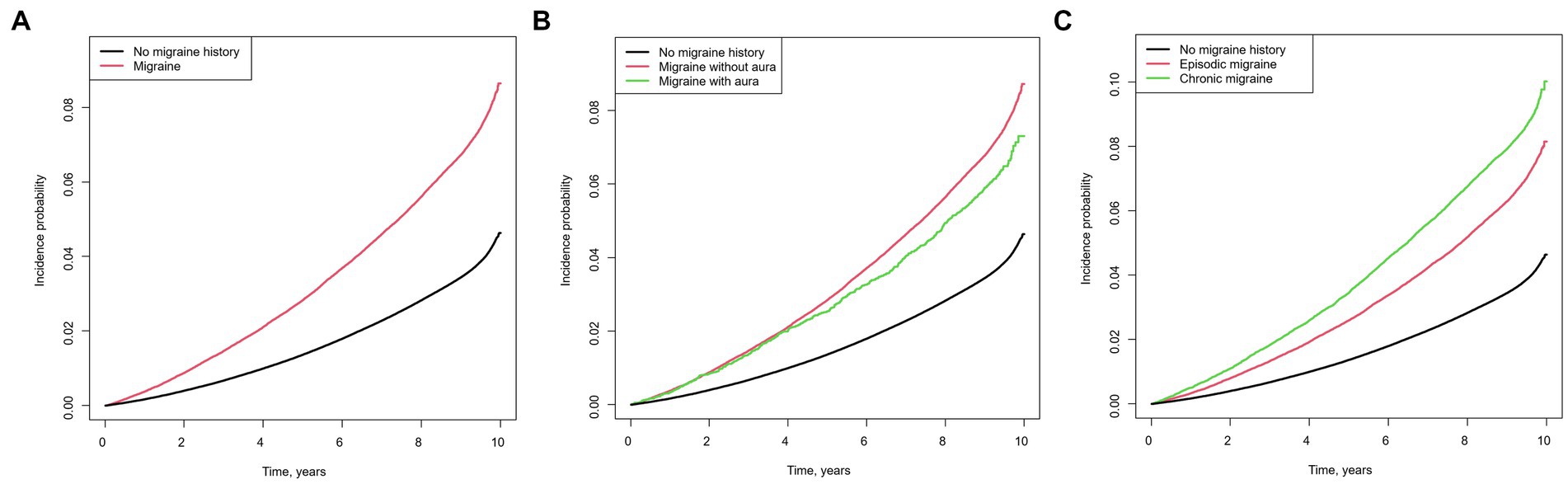

Figure 1 shows the Kaplan–Meier curves of the incidence of AD. The cumulative incidence of AD was significantly higher in participants with versus without a migraine history (Figure 1A). In the subgroup analysis, the migraine without aura group showed a higher incidence of AD than the migraine with aura group (Figure 1B). Furthermore, patients with chronic migraine had a higher cumulative incidence of AD than those with episodic migraine (Figure 1C).

Figure 1. Kaplan–Meier curves of the cumulative incidence of Alzheimer’s disease in individuals with migraine Migraine versus no migraine history (A), chronic migraine versus episodic migraine versus no migraine history (B), migraine with aura versus migraine without aura versus no migraine history (C).

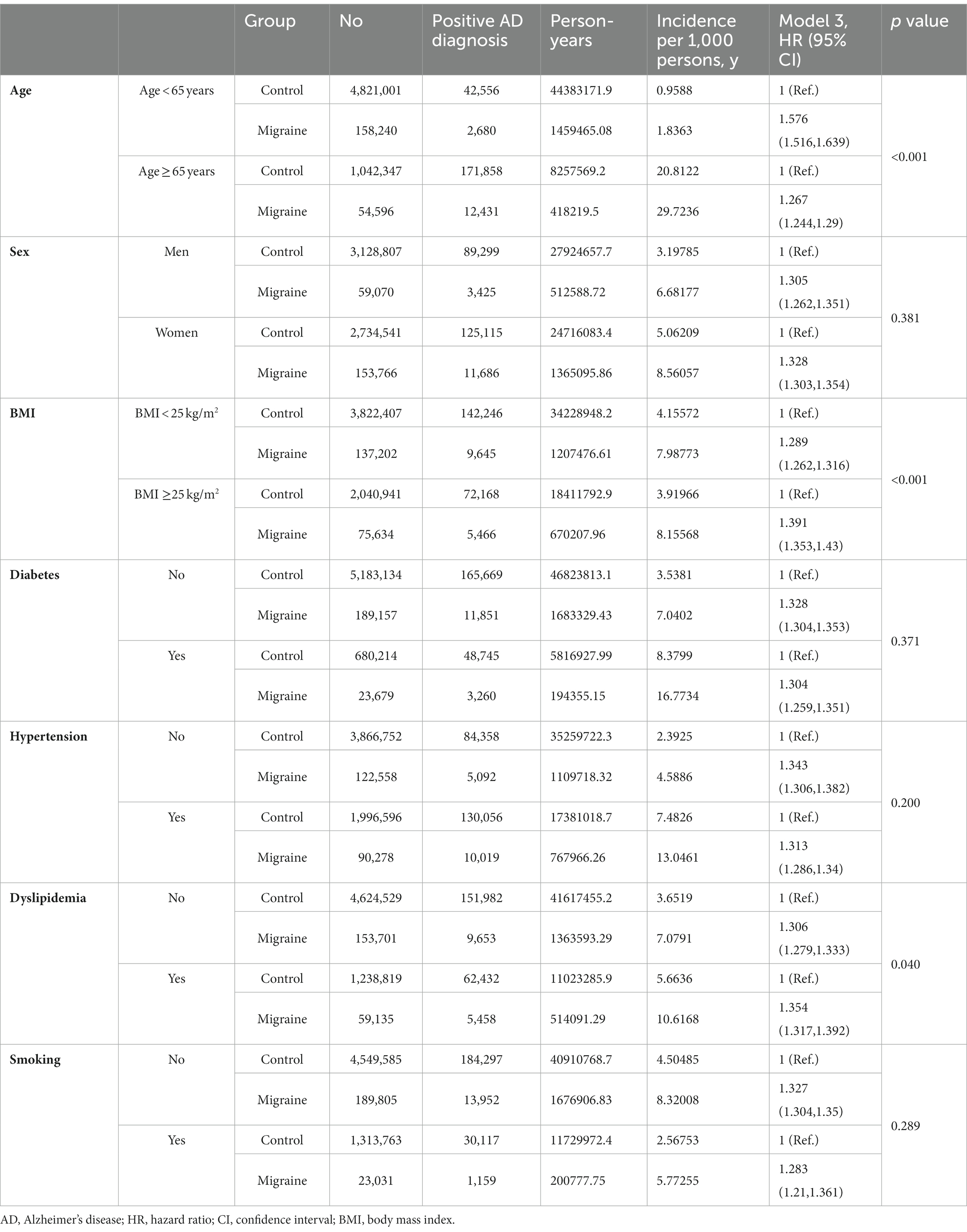

We evaluated whether AD risk factors had differential effects between participants with migraine and controls. In the younger age group (age < 65 years), participants with migraine had a higher incidence of AD (HR = 1.58 [95% CI, 1.52–1.64]) than those without migraine. This was higher than that in the older age group (aged ≥65 years) compared to those without migraine (HR = 1.27 [95% CI, 1.24–1.30]; P for interaction <0.001) after adjustments for covariates (Table 3).

Table 3. Multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analysis of the risk of Alzheimer’s disease in participants with migraine.

Additionally, in the obese group (BMI ≥25 kg/m2), participants with migraine showed a higher incidence of AD than those without migraine (HR = 1.39 [95% CI, 1.35–1.43]). The incidence of AD was also higher in the non-obese group (BMI < 25 kg/m2) than in the controls (HR = 1.29 [95% CI, 1.26–1.32]; P for interaction <0.001) (Table 3).

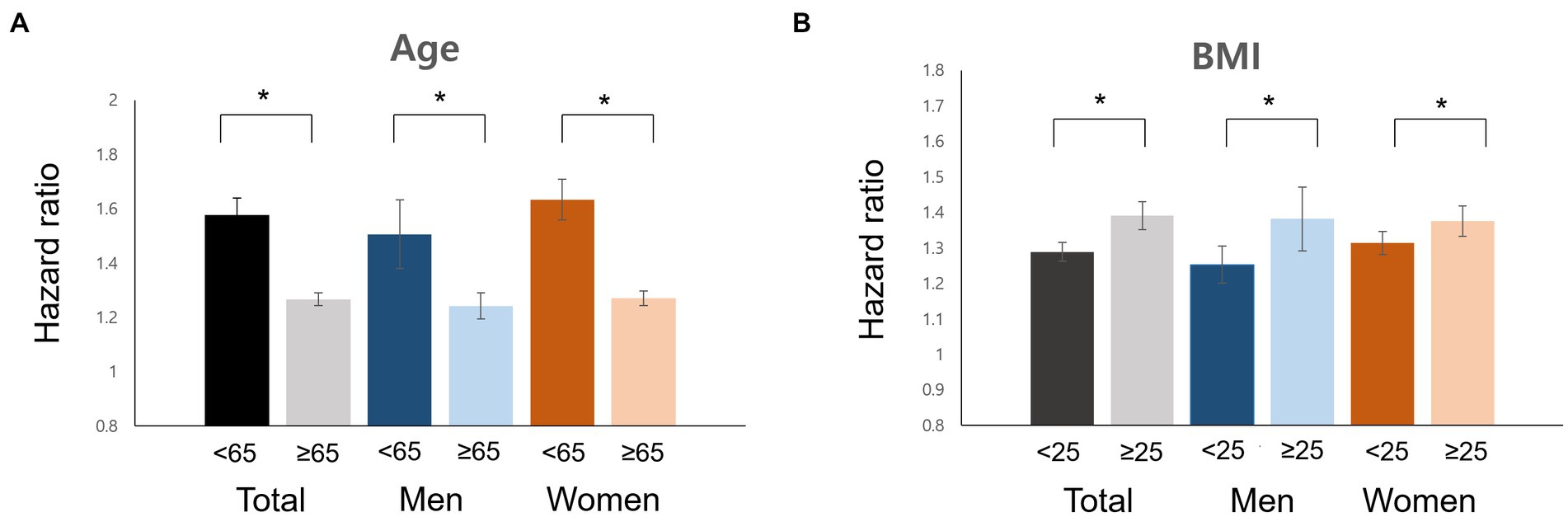

In the subgroup analysis, the interaction of age and obesity with AD incidence was consistent in both men and women (Figure 2, p < 0.05). There were no significant differences in the effects of sex, diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and current smoking status for any interaction of migraine with the incidence of AD.

Figure 2. Impacts of risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease in men and women with migraine. Age (A), BMI (B), hazard ratio. BMI, body mass index.

The present study evaluated the association between migraine and AD in a large-scale Korean nationwide population-based cohort. We found a higher incidence of AD in individuals with migraine than in those without migraine. We also found a higher AD incidence in individuals with chronic migraine than in those with episodic migraines. Lastly, we showed that younger age and higher BMI increased the risk of AD in patients with migraine.

Our first major finding was that the overall incidence of AD among individuals with migraine was higher than that in individuals with no migraine history. This result is consistent with those of previous studies that suggest that migraine is associated with an increased risk of dementia (Wang et al., 2018; Lee et al., 2021; Gu et al., 2022). We analyzed specific personal, medical, and behavioral data, including BMI, smoking history, and alcohol consumption. The prevalence rate of migraine and AD may vary depending on race-related differences (Stewart et al., 1996; Niu et al., 2017; Park et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2022), while the association between these two conditions could be influenced by disparities in lifestyle habits and socioeconomic status. Recently, Gu et al. (2022) revealed that migraine was associated with an increased risk of dementia, suggesting a significant association with cognitive decline in several country-based cohorts. Although several studies have recently reported an association between migraine and dementia, the pathomechanisms underlying the occurrence of cognitive decline in patients with migraine remain unclear. Migraine is a painful condition. Many common structures exist in the pain pathway and memory processing circuits, such as the thalamus, insula, anterior cingulate, hippocampus, and temporal cortex (Apkarian et al., 2005; Svoboda et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2018). Chronic repetitive pain can cause vulnerability of these brain structures and weaken brain function, resulting in memory deterioration.

Our second major finding was that individuals with chronic migraine showed a higher rate of AD development than individuals with episodic migraine. Due to the limited evaluation of the dataset, we set the criterion for a chronic headache diagnosis as at least two migraine diagnoses over more than 3 months in a year, contrary to the diagnostic criteria for chronic migraine. Chronic stress activates the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenocortical (HPA) axis, resulting in glucocorticoid release and HPA axis dysregulation (Herman et al., 2016). Recent studies have shown that growing evidence supports the association between HPA axis dysregulation and amyloidosis and synaptic plasticity disruption related to AD progression (Chi et al., 2014; Saeedi and Rashidy-Pour, 2021). We conjectured that individuals with chronic migraine are exposed to repetitive and extensive chronic stress, and this can accumulate, resulting in a higher incidence of AD development.

Additionally, in the multivariable analysis, we found that younger and obese individuals with migraine had a higher AD incidence than controls. There were no significant differences in the effect of other AD risk factors such as sex, diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and current smoking status for any interaction with migraine on the rate of AD development. It is known that vascular risk factors such as diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and current smoking are associated with AD (Leibson et al., 1997; Reitz, 2013; Chi et al., 2014; Durazzo et al., 2014; Ding et al., 2020). Gomez et al. demonstrated that vascular risk factors could activate brain amyloid-ß accumulation by reducing amyloid-ß clearance and increasing oxidative, inflammatory stress response (Gomez et al., 2018). A previous study showed that obesity could contribute to cognitive dysfunction by activating systemic inflammatory processes (Nguyen et al., 2014). The results of this study indicate that obese individuals with migraine may be more susceptible to AD than those without a migraine history. Based on our results, we assume that the greater the AD development in younger patients with migraine, the greater the long-term or earlier impact of these stresses on brain structure and function related to memory processes.

Our study has a few limitations. First, we collected retrospective data from a large health insurance claims databases, which can have incomplete or inaccurate coding, and the lack of detailed clinical information on the participants. Second, we used the ICD-10 diagnostic code to diagnose migraine and AD, did not use specific medical records for migraine, and AD was not confirmed by amyloid or tau biomarkers. Third, we did not evaluate the effect of migraine-specific medications on cognitive function and dementia risk such as triptans. Fourth, our study does not establish a causal relationship between the migraine and AD Further studies are needed to clarify the underlying mechanisms and potential confounding factors. Finally, it is necessary to investigate the relationship between various risk factors and diseases through follow-up studies. Despite these limitations, using a large nationwide population-based dataset with longitudinal observation seems valuable, providing a homogenous sample.

Our results suggest that individuals with a migraine history are more susceptible to AD than individuals without a migraine history. Additionally, these associations were more significant in individuals with chronic migraine and obese and younger individuals with migraine than in individuals without migraine. Our findings will encourage clinicians to consider individuals with migraine should be followed-up and corrected for the risk factors for AD dementia. Further studies are warranted to evaluate whether these risk factors influence AD exacerbation.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

JK: drafting or revising the manuscript content, including medical science writing, study concept or design, Analysis or interpretation of data. WH: study conceptualization or drafting the study design. SP: study conceptualization or drafting the study design, analysis or interpretation of data. KH: study conceptualization or drafting the study design, major role in data acquisition, and analysis or interpretation of data. MB: drafting or revision of the manuscript, study conceptualization or drafting the study design, analysis or interpretation of data.

All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This research was supported by grants from the National Research Foundation (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (NRF2022R1C1C1012535, NRF-2022R1C1C1010435), the Technology Development Program (S3030742) funded by the Ministry of SMEs and Startups (MSS, Korea), and the Technology Innovation Program (20018182) funded by the Ministry of Trade, Industry & Energy (MOTIE, Korea), the Hallym University Medical Center Research Fund. The funder had no role in the design and conduct of the study, the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnagi.2023.1196185/full#supplementary-material

Amiri, P., Kazeminasab, S., Nejadghaderi, S. A., Mohammadinasab, R., Pourfathi, H., Araj-Khodaei, M., et al. (2021). Migraine: a review on its history, global epidemiology, risk factors, and comorbidities. Front. Neurol. 12:800605. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2021.800605

Apkarian, A. V., Bushnell, M. C., Treede, R. D., and Zubieta, J. K. (2005). Human brain mechanisms of pain perception and regulation in health and disease. Eur. J. Pain 9, 463–484. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2004.11.001

Chi, S., Yu, J. T., Tan, M. S., and Tan, L. (2014). Depression in Alzheimer's disease: epidemiology, mechanisms, and management. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 42, 739–755. doi: 10.3233/JAD-140324

Ding, J., Davis-Plourde, K. L., Sedaghat, S., Tully, P. J., Wang, W., Phillips, C., et al. (2020). Antihypertensive medications and risk for incident dementia and Alzheimer's disease: a meta-analysis of individual participant data from prospective cohort studies. Lancet Neurol. 19, 61–70. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30393-X

Durazzo, T. C., Mattsson, N., and Weiner, M. W. (2014). Smoking and increased Alzheimer's disease risk: a review of potential mechanisms. Alzheimers Dement. 10, S122–S145. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.04.009

George, K. M., Folsom, A. R., Sharrett, A. R., Mosley, T. H., Gottesman, R. F., Hamedani, A. G., et al. (2020). Migraine headache and risk of dementia in the atherosclerosis risk in communities neurocognitive study. Headache 60, 946–953. doi: 10.1111/head.13794

Giannini, G., Cevoli, S., Sambati, L., and Cortelli, P. (2012). Migraine: risk factor and comorbidity. Neurol. Sci. 33, 37–41. doi: 10.1007/s10072-012-1029-6

Gomez, G., Beason-Held, L. L., Bilgel, M., An, Y., Wong, D. F., Studenski, S., et al. (2018). Metabolic syndrome and amyloid accumulation in the aging brain. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 65, 629–639. doi: 10.3233/JAD-180297

Gu, L., Wang, Y., and Shu, H. (2022). Association between migraine and cognitive impairment. J. Headache Pain 23:88. doi: 10.1186/s10194-022-01462-4

Gustavsson, A., Norton, N., Fast, T., Frölich, L., Georges, J., Holzapfel, D., et al. (2023). Global estimates on the number of persons across the Alzheimer's disease continuum. Alzheimers Dement. 19, 658–670. doi: 10.1002/alz.12694

Herman, J. P., McKlveen, J. M., Ghosal, S., Kopp, B., Wulsin, A., Makinson, R., et al. (2016). Regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical stress response. Compr. Physiol. 6, 603–621. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c150015

Islamoska, S., Hansen, Å. M., Wang, H. X., Garde, A. H., Andersen, P. K., Garde, E., et al. (2020). Mid-to late-life migraine diagnoses and risk of dementia: a national register-based follow-up study. J. Headache Pain 21:98. doi: 10.1186/s10194-020-01166-7

Jensen, R. (2003). Diagnosis, epidemiology, and impact of tension-type headache. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 7, 455–459. doi: 10.1007/s11916-003-0061-x

Kim, J., Jung, S. H., Choe, Y. S., Kim, S., Kim, B., Kim, H. R., et al. (2022). Ethnic differences in the frequency of β-amyloid deposition in cognitively normal individuals. Neurobiol. Aging 114, 27–37. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2022.03.001

Kostev, K., Bohlken, J., and Jacob, L. (2019). Association between migraine headaches and dementia in more than 7,400 patients followed in general practices in the United Kingdom. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 71, 353–360. doi: 10.3233/JAD-190581

Lee, H. J., Yu, H., Gil Myeong, S., Park, K., and Kim, D. K. (2021). Mid-and late-life migraine is associated with an increased risk of all-cause dementia and Alzheimer's disease, but not vascular dementia: a Nationwide retrospective cohort study. J. Pers. Med. 11:990. doi: 10.3390/jpm11100990

Leibson, C. L., Rocca, W. A., Hanson, V. A., Cha, R., Kokmen, E., O'Brien, P. C., et al. (1997). Risk of dementia among persons with diabetes mellitus: a population-based cohort study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 145, 301–308. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009106

Liu, H. Y., Chou, K. H., and Chen, W. T. (2018). Migraine and the Hippocampus. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 22:13. doi: 10.1007/s11916-018-0668-6

Lloret, A., Monllor, P., Esteve, D., Cervera-Ferri, A., and Lloret, A. (2019). Obesity as a risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease: implication of Leptin and glutamate. Front. Neurosci. 13:508. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2019.00508

Morton, R. E., St John, P. D., and Tyas, S. L. (2019). Migraine and the risk of all-cause dementia, Alzheimer's disease, and vascular dementia: a prospective cohort study in community-dwelling older adults. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 34, 1667–1676. doi: 10.1002/gps.5180

Nguyen, J. C., Killcross, A. S., and Jenkins, T. A. (2014). Obesity and cognitive decline: role of inflammation and vascular changes. Front. Neurosci. 8:375. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2014.00375

Niu, H., Álvarez-Álvarez, I., Guillén-Grima, F., and Aguinaga-Ontoso, I. (2017). Prevalence and incidence of Alzheimer's disease in Europe: a meta-analysis. Neurologia 32, 523–532. doi: 10.1016/j.nrl.2016.02.016

Park, J. E., Kim, B. S., Kim, K. W., Hahm, B. J., Sohn, J. H., Suk, H. W., et al. (2019). Decline in the incidence of all-cause and Alzheimer's disease dementia: a 12-year-later rural cohort study in Korea. J. Korean Med. Sci. 34:e293. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2019.34.e293

Qiu, C., von Strauss, E., Fastbom, J., Winblad, B., and Fratiglioni, L. (2003). Low blood pressure and risk of dementia in the Kungsholmen project: a 6-year follow-up study. Arch. Neurol. 60, 223–228. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.2.223

Reitz, C. (2013). Dyslipidemia and the risk of Alzheimer's disease. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 15:307. doi: 10.1007/s11883-012-0307-3

Saeedi, M., and Rashidy-Pour, A. (2021). Association between chronic stress and Alzheimer's disease: therapeutic effects of saffron. Biomed. Pharmacother. 133:110995. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110995

Stewart, W. F., Lipton, R. B., and Liberman, J. (1996). Variation in migraine prevalence by race. Neurology 47, 52–59. doi: 10.1212/WNL.47.1.52

Svoboda, E., McKinnon, M. C., and Levine, B. (2006). The functional neuroanatomy of autobiographical memory: a meta-analysis. Neuropsychologia 44, 2189–2208. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2006.05.023

Keywords: migraine, dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, headache, cohort studies

Citation: Kim J, Ha WS, Park SH, Han K and Baek MS (2023) Association between migraine and Alzheimer’s disease: a nationwide cohort study. Front. Aging Neurosci. 15:1196185. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2023.1196185

Received: 29 March 2023; Accepted: 10 May 2023;

Published: 25 May 2023.

Edited by:

Nilton Custodio, Peruvian Institute of Neurosciences (IPN), PeruCopyright © 2023 Kim, Ha, Park, Han and Baek. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Min Seok Baek, bWluYmFla0B5b25zZWkuYWMua3I=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.