- 1Molecular Medicine Research Center, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran

- 2Department of Medical Genetics, Faculty of Medicine, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran

- 3Department of Biology, Faculty of Sciences, Shahid Bahonar University of Kerman, Kerman, Iran

- 4Skull Base Research Center, Loghman Hakim Hospital, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

- 5Institute of Human Genetics, Jena University Hospital, Jena, Germany

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a heterogeneous degenerative brain disorder with a rising prevalence worldwide. The two hallmarks that characterize the AD pathophysiology are amyloid plaques, generated via aggregated amyloid β, and neurofibrillary tangle, generated via accumulated phosphorylated tau. At the post-transcriptional and transcriptional levels, the regulatory functions of non-coding RNAs, in particular long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), have been ascertained in gene expressions. It is noteworthy that a number of lncRNAs feature a prevalent role in their potential of regulating gene expression through modulation of microRNAs via a process called the mechanism of competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA). Given the multifactorial nature of ceRNA interaction networks, they might be advantageous in complex disorders (e.g., AD) investigations at the therapeutic targets level. We carried out scoping review in this research to analyze validated loops of ceRNA in AD and focus on ceRNA axes associated with lncRNA. This scoping review was performed according to a six-stage methodology structure and PRISMA guideline. A systematic search of seven databases was conducted to find eligible articles prior to July 2021. Two reviewers independently performed publications screening and data extraction, and quantitative and qualitative analyses were conducted. Fourteen articles were identified that fulfill the inclusion criteria. Studies with different designs reported nine lncRNAs that were experimentally validated to act as ceRNA in AD in human-related studies, including BACE1-AS, SNHG1, RPPH1, NEAT1, LINC00094, SOX21-AS1, LINC00507, MAGI2-AS3, and LINC01311. The BACE1-AS/BACE1 was the most frequent ceRNA pair. Among miRNAs, miR-107 played a key role by regulating three different loops. Understanding the various aspects of this regulatory mechanism can help elucidate the unknown etiology of AD and provide new molecular targets for use in therapeutic and clinical applications.

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder (NDD) and is a form of dementia that triggers difficulties with memory, thinking, and behavior (Kang et al., 2020). Based on the Alzheimer’s Association, AD makes up about approximately 60–80% of dementia cases. Currently, worldwide, 50 million people are living with AD and other dementias. AD incidence doubles every 5 years after age 65 (Fan et al., 2020). Symptoms generally develop slowly and aggravate with time. From a hereditary point of view, AD is a heterogeneous polygenic condition. The condition has been categorized into two groups according to age-onset: early-onset AD (EOAD) and late-onset AD (LOAD). LOAD also called sporadic AD (SAD), is the most common type of dementia. AD is a multifactorial condition as a result of interactions between the susceptible genes and environmental factors (Rezazadeh et al., 2019). Genes play an important role in AD. The heritability of LOAD is 58–79%, while it is more than 90% in EOAD. The genetic association has helped us to understand the etiology of AD. Over 50 loci are currently associated with AD. These findings highly suggest that AD is a complex disease (Sims et al., 2020).

Alzheimer’s Disease Pathogenesis

The pathophysiology of AD is defined by the accumulation of β-amyloid peptide (Aβ) in the brain, as well as hyperphosphorylated and cleaved structures of the microtubule-associated protein tau. It is known that metabolic dysfunction of Aβ precursor protein (APP) and abnormal tau protein phosphorylation (Kang et al., 2020) or maybe their interaction with each other (Busche and Hyman, 2020) results in senile plaques and neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) formation. According to biochemical, behavioral, and genetic research, the pathologic development of the neurotoxic Aβ peptide resulting from serial APP proteolysis is a critical step in AD development. Moreover, APP is metabolized rapidly and in a highly complicated manner by groups of sequential secretases, including β-site APP-cleaving enzyme 1 (BACE1), γ-secretase, and the ADAM family as α-secretases. Regarding tau proteolysis, this process is crucial in neurodegeneration and the tau aggregation process. Tau is a microtubule-associated protein that is predominantly produced in neurons and is encoded by the Microtubule-Associated Protein Tau (MAPT) gene. Intracellular tau is sometimes hyperphosphorylated, resulting in hazardous oligomers and aggregates visible as NFTs (Kang et al., 2020). Aside from the tau and amyloid theory about AD, several additional ideas have been proposed, namely inflammatory reactions, oxidative stress, mitochondrial failure, and cholinergic hypothesis (Li et al., 2021). Although there are numerous hypotheses about AD pathogenesis, the actual triggers and ideal therapy strategies are still elusive.

Antisense Therapeutics

For therapeutic development, RNA is a novel target with numerous advantages, including: (Kang et al., 2020) it is applicable to a majority of RNAs in the cells, such as non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs), (Fan et al., 2020) genetic discoveries can directly be translated to drug discovery, and drug discovery would be more rapid and efficient. Whereas other promising progress has been made in the discovery of small-molecule medicines that affect RNA activity, antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) provide a far straightforward technique (Bennett et al., 2019). ASOs are synthetic oligonucleotides or oligonucleotide analogs with lengths ranging from 12 to 30 nucleotides (nt) and are engineered for binding to RNA through Watson-Crick base pairing. ASOs can be constructed to bind to both protein-coding RNAs (mRNAs) and ncRNAs, including microRNAs (miRNAs) or long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs). After ASOs bind with the RNAs of interest, antisense medicine can alter the activity of the RNAs in different ways (Bennett and Swayze, 2010; Crooke et al., 2018).

Long Non-coding RNAs

NcRNAs are classified into two types based on their lengths: short ncRNAs (less than 200 nt) and long ncRNAs (more than 200 nt). lncRNAs range in size from 200 nt to more than 100 kb and often lack a clear open reading frame. LncRNAs, resembling protein-coding genes, are widely transcribed by RNA polymerase II and are frequently post-transcriptionally changed by 5′ capping, 3′ polyadenylation, and RNA splicing processes. However, lncRNAs differ from protein-coding genes in that they possess shorter lengths and exhibit poorer sequence conservation among species (Quinn and Chang, 2016). Many biological functions rely on lncRNAs, including RNA transcription, translation, chromatin and DNA modifications, mRNA stability, and pre-RNA splicing (Li et al., 2021).

Long Non-coding RNAs and mRNA Stability

The rate of mRNA synthesis and degradation determines its steady-state level; hence, the degradation of mRNA is an important factor in controlling gene expression. Previous research has shown that instability of mRNAs that encode synaptic transmission proteins leads to synaptic function loss in AD pathogenesis (Alkallas et al., 2017). Furthermore, in AD patients, the mRNA degradation rate of AD risk genes is abnormal (Beyer et al., 2009). It has been shown that lncRNAs have a role in AD pathogenesis via regulating mRNA stability (Li et al., 2021).

Competing Endogenous RNA Hypothesis

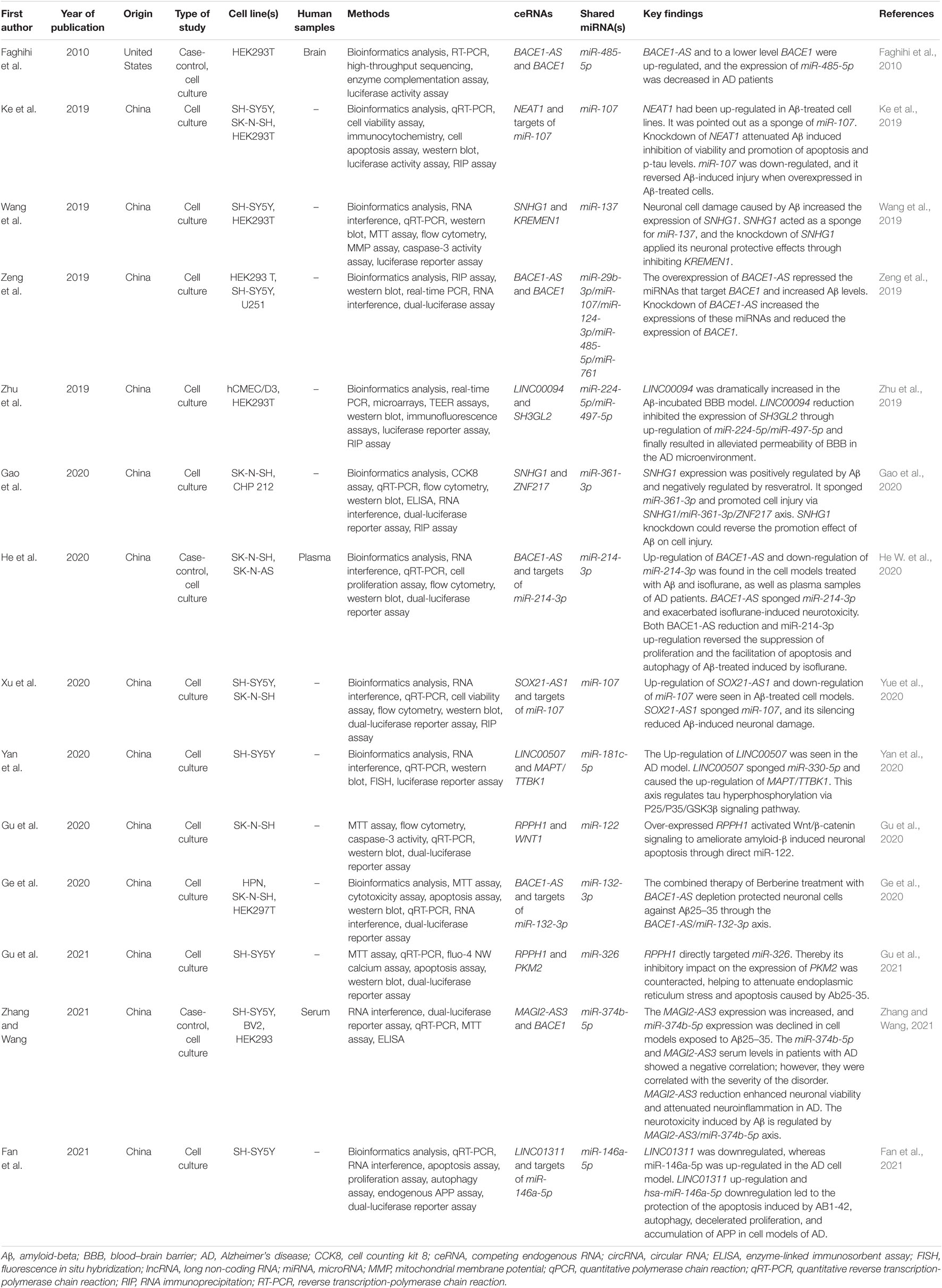

A new mechanism of interaction between RNAs, called ceRNA, is proposed by Pier Paolo Pandolfi’s group in 2011. This hypothesis suggests that cross-talk between RNAs, both coding RNAs and ncRNAs (such as lncRNAs, circRNAs: circular RNAs, and pseudogenes) through miRNA complementary sequences called miRNA response elements (MREs) builds a large-scale regulatory network throughout the transcriptome. Based on the ceRNA hypothesis, if two RNA transcripts regulate each other via a ceRNA mediated mechanism, the expression levels of these two RNA transcripts would be negatively correlated with the levels of target miRNAs, and the expression levels of these two RNA transcripts would be positively associated with each other (Salmena et al., 2011). Figure 1 demonstrates the most simplified ceRNA model. Studies of ceRNA interactions are according to the prediction of target RNA transcripts using multiple software programs (Shuwen et al., 2018) such as StarBase (Li et al., 2014), TargetScan (Agarwal et al., 2015), PicTar (Krek et al., 2005), and StarScan (Liu et al., 2015). These predictions are based on identifying the same MRE within multiple RNA sequences. As the precision of prediction programs is unclear (Amirkhah et al., 2015) due to insufficient raw data for algorithms to reference, the prediction results must still be validated (Shuwen et al., 2018).

Figure 1. Competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA) model. All transcriptome components, such as long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), circRNAs, pseudogenes, and mRNAs that share common MRE, can function as ceRNAs and can co-regulate each other by sponging shared miRNAs. Differentially expressed transcripts can lead to ceRNA dysregulation and biological alterations. ceRNA. (A) Down-regulation of ceRNAs increases the amounts of free miRNAs, thereby repressing target expression. (B) Conversely, up-regulation of ceRNAs reduces free miRNAs abundance, thereby derepressing target expression. Competing endogenous RNA; circRNA, circular RNA; lncRNA, long non-coding RNA; miRNA, microRNA; MRE, miRNA response element.

Over the last few years, several studies have verified the ceRNA theory. It is well known that the disruption of the equilibrium of ceRNA cross-talk can play a role in various diseases (Sen et al., 2014). So far, the ceRNA mechanisms have been further studied in the field of cancer (Yang et al., 2016). During the last 4 years, the study in the field of NDDs has begun systematically, and significant improvements have been produced. Among NDDs, the ceRNA interactions in AD have been studied to a greater extent (Cai and Wan, 2018). Since 2017, there have been increasing studies to identify the genome-wide ceRNA networks in AD using bioinformatics prediction (Wang et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2017; Sekar et al., 2018; Wang Z. et al., 2018; Yu et al., 2018; Ma N. et al., 2019; Zhang Y. et al., 2019; Zhou et al., 2019; Ma et al., 2020; Xu and Jia, 2020). Since interaction networks of ceRNAs are multifactorial, they might be advantageous in investigations of complicated diseases, like AD, in terms of therapeutic targets only by targeting one of them, the levels of several disease-related RNAs change at once (Moreno-García et al., 2020).

Aim of Study

In this study, we performed a scoping review to analyze validated ceRNA loops in AD. Our focus was on lncRNA-associated ceRNA axes that underlie AD pathophysiology and could potentially be therapeutic targets.

Methods

The strategy for this review was according to the scoping review structure recommended by Arksey and O’Malley (2005) and later improved by Levac et al. (2010). This consists of five distinct steps: (1) identifying the research question, (2) identifying relevant studies, (3) study selection, (4) charting the data, and (5) collating, summarizing, and reporting results. An optional sixth step in the scoping review, consultation, was not used in our study. This review was also well guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) Checklist (Tricco et al., 2018).

Identifying the Research Question

This study focused on mapping the current literature on lncRNA-associated ceRNA loops in AD. To address this aim, we sought to answer the following question: Precisely what is known from existing literature about lncRNA-associated ceRNA regulatory axes in AD?

Identifying Relevant Studies

An initial limited search of PubMed and Embase was performed, and then the keywords in the title and abstract were assessed, as well as the index terms that were utilized in the articles. A second search was performed across PubMed, Embase, Scopus, Web of Science, and Cochrane databases according to specific search tips of each database without any restriction, using keywords, MeSH, or Emtree terms recognized from the primary search. The search strategies for PubMed and Embase are shown in Appendix I. Additionally, searches were also carried out in two gray (i.e., difficult to locate or unpublished) literature databases: Google Scholar and ProQuest. The last search was performed on July 10, 2021. We also examined the reference lists of the relevant literature and review articles for additional sources.

Selecting Studies

The included studies fulfilled the following criteria: (1) explicitly discussing the lncRNA-associated ceRNA axes in AD, (2) written in English, and (3) be original research. The exclusion criteria were (1) studies of non-AD or unspecified dementia, (2) studies that did not use human specimens or cell lines, and (3) studies that did not use molecular techniques to validate the components of the ceRNA loop. The title and abstract of articles were first independently screened by three reviewers (HS, NA) for eligibility according to the above criteria. The full texts of the remaining articles were evaluated, and articles going to fulfill the eligibility criteria were included in the final data analysis. Any disagreements were solved through discussion or with a third reviewer (MR) if required.

Charting the Data

Three reviewers (HS and NA) independently extracted data into a predesigned charting form in Microsoft Excel. It provided details about the first author, year of publication, origin, type of study, cell line(s), human samples, methods, ceRNAs, shared miRNA(s), and key findings.

Collating, Summarizing, and Reporting the Results

We performed quantitative and qualitative analyses. For the quantitative part, we provided a descriptive numerical summary of the characteristics of the included articles. For the qualitative analysis, we provided a narrative review of the existing information addressing our earlier mentioned research question, focusing on the importance of results in the broader framework as suggested by Levac et al. (2010).

Results

Search Results

The different steps of finding eligible studies are shown in the flow chart in Figure 2. A total of 395 articles were identified from different sources, of which 208 were duplicates. One hundred and fifty-three articles were excluded for irrelevance. The full texts of the remaining 34 articles were evaluated, and 20 more articles were also excluded because they did not validate the components of the ceRNA loop using molecular techniques (Wang et al., 2017; Yu et al., 2018; Zhou et al., 2019; Ma et al., 2020; Xu and Jia, 2020; Huaying et al., 2021; Lu et al., 2021; Ou et al., 2021; Tang et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2021) and did not use human specimens or cell lines (Jiang et al., 2016; Cai et al., 2017; Wang J. et al., 2018; Wang X. et al., 2018; Ma P. et al., 2019; Zhao et al., 2019; Li L. et al., 2020; Li X. et al., 2020; Yue et al., 2020; Zhou et al., 2020). Lastly, a total of 14 eligible articles remained (Faghihi et al., 2010; Ke et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2019; Zeng et al., 2019; Zhu et al., 2019; Gao et al., 2020; Ge et al., 2020; Gu et al., 2020, 2021; He W. et al., 2020; Yan et al., 2020; Yue et al., 2020; Fan et al., 2021; Zhang and Wang, 2021).

Study Characteristics

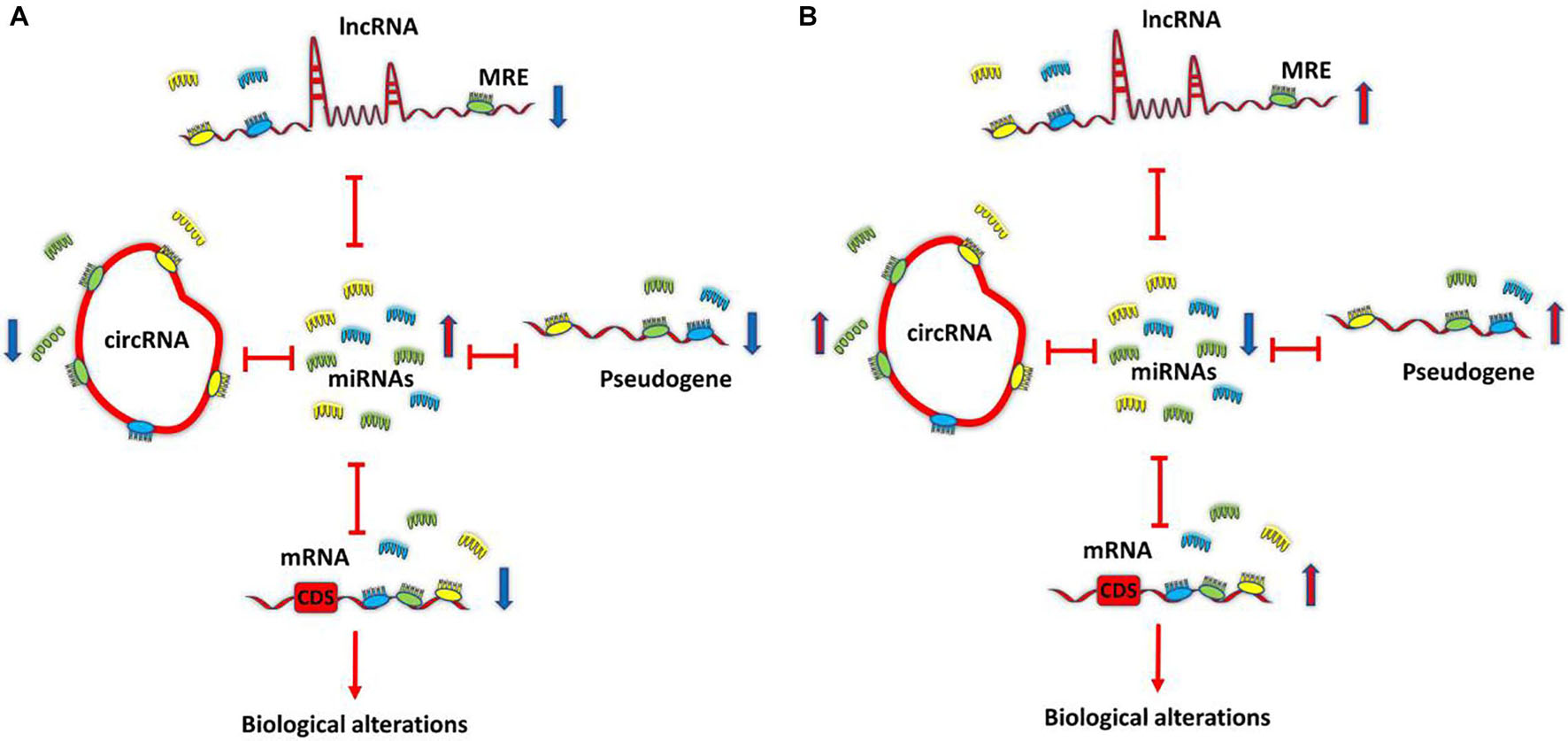

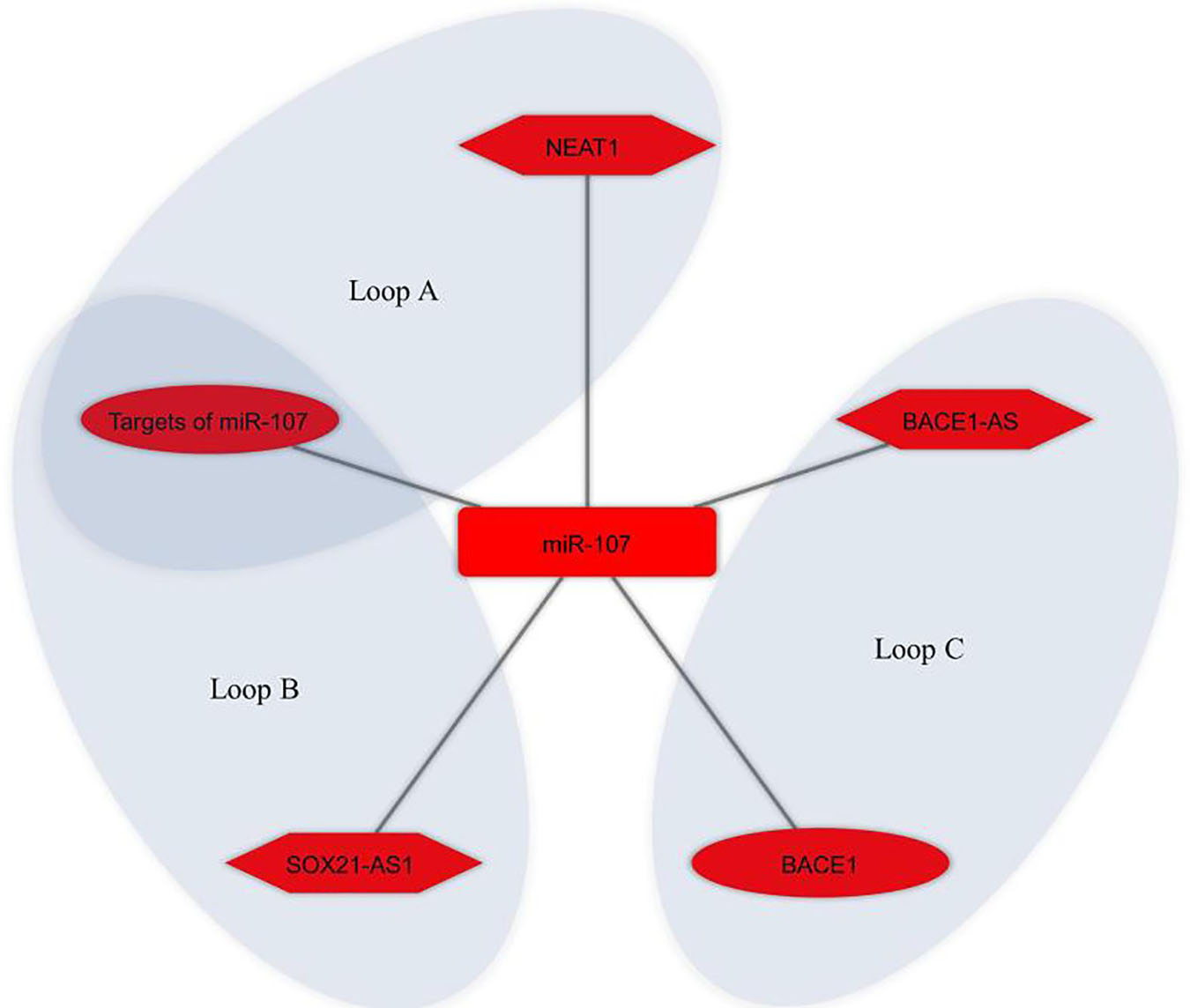

The characteristics of the included studies are summarized in Table 1. Almost all studies have been published since 2019. All but one study (Faghihi et al., 2010) was conducted in China. Eleven studies examined the ceRNA regulatory loop on human cell lines (Ke et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2019; Zeng et al., 2019; Zhu et al., 2019; Gao et al., 2020; Ge et al., 2020; Gu et al., 2020, 2021; Yan et al., 2020; Yue et al., 2020; Fan et al., 2021) and three on both human specimens and cell lines (Faghihi et al., 2010; He W. et al., 2020; Zhang and Wang, 2021). All studies with human specimens had a case-control design. One study used brain samples (Faghihi et al., 2010), one used plasma samples (He W. et al., 2020), and one used serum samples (Zhang and Wang, 2021).

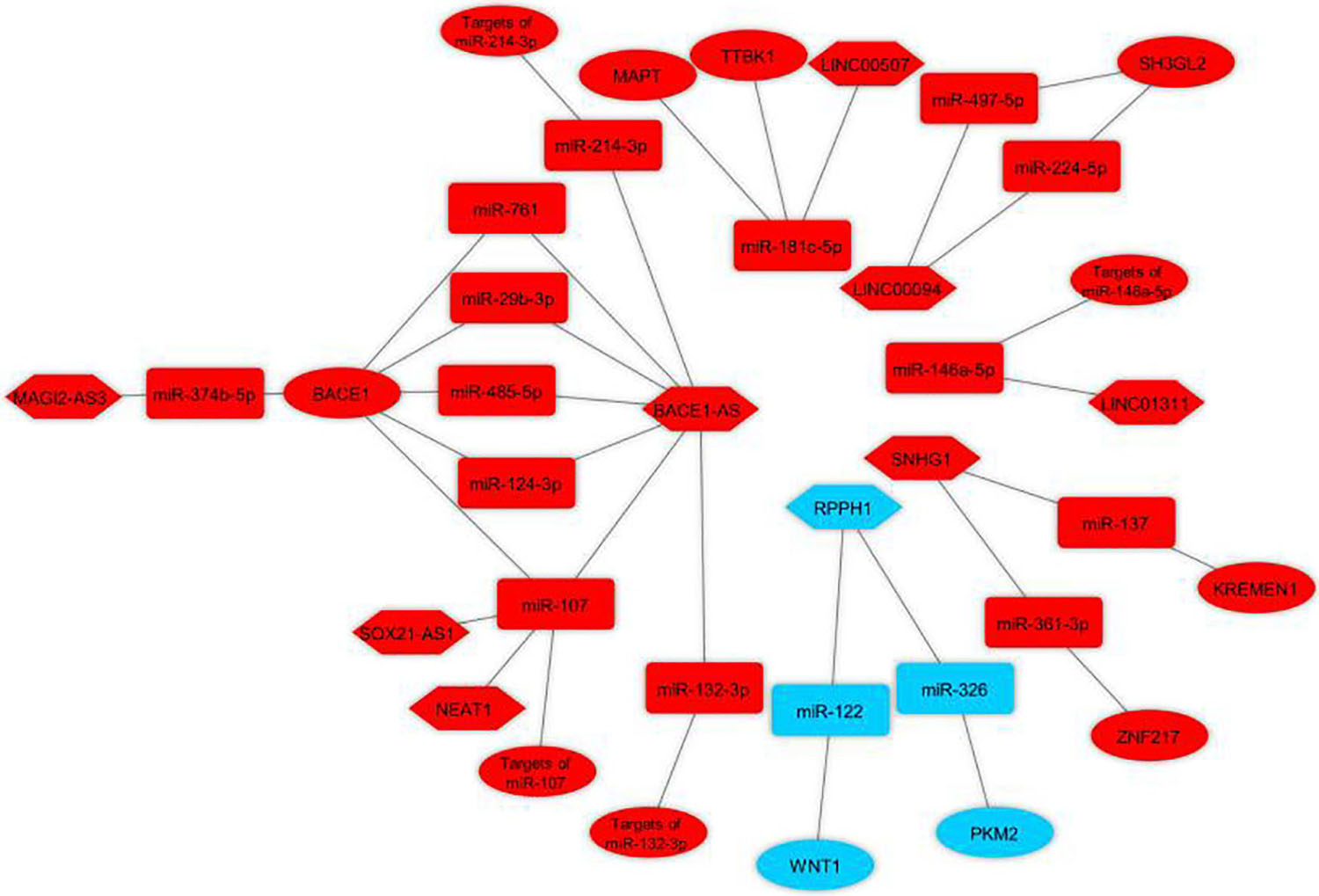

Bioinformatics analysis was used to identify the potential ceRNA interactions. Also, different molecular techniques were utilized to validate the components of the ceRNA loop and investigate their involvement in AD pathogenesis. The reported loops are shown in Figure 3. The lncRNA BACE1-antisense (BACE1-AS) was reported in four studies (Faghihi et al., 2010; Zeng et al., 2019; Ge et al., 2020; He W. et al., 2020), two of which had BACE1-AS/miR-485-5p/BACE1 regulatory axis (Faghihi et al., 2010; Zeng et al., 2019), as well as BACE1 was a target mRNA in three studies (Faghihi et al., 2010; Zeng et al., 2019; Zhang and Wang, 2021). The lncRNA small nucleolar RNA host gene 1 (SNHG1) (Wang et al., 2019; Gao et al., 2020) and the lncRNA ribonuclease P RNA component H1 (RPPH1) (Gu et al., 2020, 2021) were each reported in two articles. The remaining ceRNAs were reported once each in six studies (Ke et al., 2019; Zhu et al., 2019; Yan et al., 2020; Yue et al., 2020; Fan et al., 2021; Zhang and Wang, 2021). Among the identified miRNAs, miR-107 was reported in three regulatory axes in three different studies (Ke et al., 2019; Zeng et al., 2019; Yue et al., 2020). According to these results, we found that three independent ceRNA interaction loops (loop A, loop B, and loop C) are regulated by miR-107. Loop A includes nuclear enriched abundant transcript 1 (NEAT1) and targets of miR-107, loop B includes SOX21 antisense RNA1 (SOX21-AS1) and targets of miR-107, loop C includes BACE1-AS and BACE1 (Figure 4).

Figure 3. Validated lncRNA-associated ceRNA axes in Alzheimer’s disease. The loops were visualized using Cytoscape v3.8.0 software (Shannon et al., 2003) based on lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA interactions. Red represents the damaging role, and blue represents the protective role of competing endogenous RNA axes. LncRNAs, miRNAs, and mRNAs are represented by hexagon, round rectangle, and ellipse, respectively. LncRNA, long non-coding RNA; miRNA, microRNA.

Figure 4. miR-107 regulates different competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA) loops. Loop A (NEAT1 and targets of miR-107), loop B (SOX21-AS1 and targets of miR-107), and loop C (BACE1-AS and BACE1) were all regulated by miR-107. Red represents the damaging role of ceRNA axes. Lon non-coding RNAs, microRNAs, and mRNAs are represented by hexagon, round rectangle, and ellipse, respectively.

Discussion

The most contentious issue with ceRNA regulation is whether or not it is effective in physiological contexts. Most studies questioning ceRNA functions reach the conclusion that regulation of ceRNA is highly improbable to yield biologically major impacts at physiological RNA concentrations; however, these experiments cannot rule out the potential of potent miRNA sponges or the marked downregulation or upregulation of ceRNAs and miRNAs at particular developmental stages or subcellular sites (Denzler et al., 2014; Cai and Wan, 2018). There are many reports indicating that ceRNA machinery operates in numerous diseases and that ceRNA is expressed differently with various tissues, cells, and subcellular situations. The literature represents novel visions by which designing ceRNA-mechanism-based therapeutical utilization can be facilitated for the manipulation of special developmental phases and disease pathogenicity with the use of synthesized oligonucleotides specific to sequences (Khvorova and Wolfson, 2012). Over the last decade, significant effort has been put toward the clinical use of RNA-based therapies, mainly using antisense oligonucleotides as well as small interfering RNAs, with many obtaining Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval (Winkle et al., 2021). However, trial findings have been mixed, with some research claiming strong benefits and others showing minimal effectiveness or toxicity. Alternate entities, including lncRNA-based therapies, are gaining interest (Winkle et al., 2021). The lncRNAs’ wide function offers many possibilities for clinical application, the methods of which must be adapted to the lncRNA’s mode of action (Arun et al., 2018). Investigating natural antisense transcripts (NATs): lncRNAs that are transcribed from opposite strands of adjacent genes and negatively regulate them in cis is an intriguing discovery. AntagoNATs are ASOs that target NATs and have demonstrated extremely promising preclinical findings for gene reactivation in the central nervous system (CNS) (Winkle et al., 2021). AntagoNATs effectively increased the expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a protein important in memory development (Modarresi et al., 2012), and the healthy allele of SCN1A, the haploinsufficiency of which triggers Dravet syndrome (Hsiao et al., 2016). Remarkably, BDNF-AS-targeting antagoNATs were effectively delivered across the blood–brain barrier in a murine model utilizing a minimally invasive nasal depot (MIND). MIND is a medication delivery system that directs drug administration to the olfactory submucosal region and has achieved about 40% effectiveness compared to riskier invasive delivery methods (Padmakumar et al., 2021). Such encouraging findings imply that lncRNA-based therapies will soon enter clinical testing. Moreover, the therapeutical impact of ASO-based lncRNA knockdown has shown promise in patients with Angelman syndrome, a single-gene illness represented by intellectual disability (Bird, 2014; Meng et al., 2015). Despite no development of ASOs that target lncRNA in the therapy of NDDs, ASOs that target mRNAs have received approval by the FDA for the therapy of Duchenne muscular dystrophy and spinal muscular atrophy (Wurster and Ludolph, 2018). Furthermore, ASOs have presented potential effectiveness in the therapy of Huntington’s disease (HD) by affecting the huntingtin gene (HTT) as the target, in the therapy of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis by influencing SOD1 and C9ORF72 as the targets, and in the therapy of AD by affecting MAPT (tau) as the target (Scoles et al., 2019). Hence, lncRNAs and lncRNA-associated ceRNA axes can also serve as a new therapeutical target for AD therapy. In this study, we performed a scoping review and identified nine lncRNAs that were experimentally validated to act as ceRNA in AD in human studies. These lncRNAs are discussed below.

BASE1-AS

As mentioned above, in AD patients, the extracellularly deposited plaque of the Aβ peptide is one of the representative pathologic signs. To produce Aβ, APP needs to be sequentially cleaved proteolytically with β-secretase and γ-secretase. BACE1 is a critical enzyme in AD pathophysiology responsible for Aβ plaque formation through the cleavage of APP in collaboration with γ-secretase. Thus, a misregulated BACE1 can have a major contribution to this pathologic event. Both miRNAs and lncRNAs have been involved in regulating BACE1 post-transcriptionally, with which lncRNA BACE1-AS has the utmost relevancy (Zeng et al., 2019). The lncRNA BACE1-AS was the first validated component of a ceRNA loop described in AD pathogenesis. Both BACE1-AS and BACE1 mRNA transcripts originate from a similar locus in chromosome 11 in humans; the transcription of BACE1 mRNA and BACE1-AS is triggered from the sense and antisense strands, respectively. An RNA duplex is formed by pairing BACE1-AS to BACE1, leading to a structurally changed BACE1 and improved stableness of mRNA. Consequently, BACE1-AS has a role in increasing both the mRNA and protein concentrations of BACE1 (Faghihi et al., 2008, 2010). This ceRNA pair had been reported in two studies. The first loop was BACE1-AS/miR-485-5p/BACE1, which was shown to be involved in AD pathogenesis through BACE1 post-transcriptional regulation (Faghihi et al., 2010). It was also shown that BACE1-AS and to a lower level BACE1 were up-regulated, and the expression of miR-485-5p was decreased in the brain of AD patients (Faghihi et al., 2010). The second study showed that BACE1-AS prevented BACE1 mRNA degradation by sponging miR-29b-3p/miR-107/miR-124-3p/miR-485-5p/miR-761 in the pathophysiology of AD. In addition to the mentioned ceRNA pair, it was shown that BACE1-AS exacerbated isoflurane (anesthetic)-induced neurotoxicity by BACE1-AS/miR-214-3p axis in AD (He W. et al., 2020). This drug increases the risk of AD by increasing Aβ production and its oligomerization, as well as neuronal apoptosis (Xie et al., 2006, 2008; Xie and Xu, 2013). It is noteworthy that increased expression of BACE1-AS and down-regulation of miR-214-3p in the plasma samples of AD patients was also reported. In addition, BACE1-AS is a ceRNA for miR-132-3p. This axis was involved in the berberine-mediated neuroprotective effect in AD (Ge et al., 2020). Berberine is an isoquinoline alkaloid found in many medicinally important plants (Kumar et al., 2015). Berberine has been reported to play a crucial role in AD treatment (Yuan et al., 2019).

MAGI2 Antisense RNA 3 (MAGI2-AS3)

Alongside BACE1-AS, MAGI2-AS3 (via miR-374b-5p) could reportedly regulate BACE1 mRNA levels, Aβ-induced neurotoxicity, and neuroinflammation in AD (Zhang and Wang, 2021). This underlines that the BACE1 is complexly regulated in AD by the mediation of multiple ceRNA networks. It was also shown that serum MAGI2-AS3 and miR-374b-5p expression was significantly up-regulated and down-regulated in AD patients compared with healthy controls, respectively (Zhang and Wang, 2021). LncRNA MAGI2-AS3 is reportedly a sponger of miR-374b-5p in ovarian carcinoma and hepatocellular carcinoma (Gokulnath et al., 2019; Yin Z. et al., 2019). It has been found to be involved in regulating cell survivability in a variety of diseases (Cao et al., 2020; He J. et al., 2020). There are also reports on the association between MAGI2-AS3 and chronic inflammatory illnesses (Liao et al., 2020).

SNHG1

In AD pathology, SNHG1 involves in Aβ-induced neuronal injury via two different ceRNA regulatory axes, SNHG1/miR-137/kringle containing transmembrane protein 1 (KREMEN1) (Wang et al., 2019) and SNHG1/miR-361-3p/zinc finger gene 217 (ZNF217) (Gao et al., 2020). SNHG1 has been well-studied in different types of cancers due to its oncogenic role (Huang et al., 2018). It is shown that it can also promote neuronal autophagy and neuroinflammation in Parkinson’s disease (PD) (Cao et al., 2018; Chen et al., 2018b). KREMEN1 encodes a receptor for Dickkopf (DKK) proteins that functionally cooperates with DKK1/2 to inhibit wingless (WNT)/beta-catenin signaling (Mulvaney et al., 2016; Stelzer et al., 2016). It exerts its pro-apoptotic activity in a Wnt-independent pathway (Causeret et al., 2016). It has been shown that the silencing of KREMEN1 prevents Aβ-mediated synapse loss in AD (Ross et al., 2018). Besides, the oncogenic role of ZNF217 has been shown in many cancers (Quinlan et al., 2007). In AD studies, the down-regulation of ZNF217 could relieve Aβ-induced neurotoxicity (Wang J. et al., 2018). It had also been shown that the neuroprotective effect of resveratrol could occur through SNHG1/miR-361-3p/ZNF217 axis (Gao et al., 2020). Resveratrol is a polyphenolic compound that its high concentrations are found in red grapes, blueberries, and peanuts (Evans et al., 2017). Various studies have proved its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects on AD (Gomes et al., 2018; Corpas et al., 2019; Kong et al., 2019).

NEAT1

NEAT1 aggravated Aβ-induced neuronal injury via acting as a sponge for miR-107 (Ke et al., 2019). Knockdown of NEAT1 attenuated Aβ induced inhibition of viability and promotion of apoptosis and p-tau levels. MiR-107 was down-regulated, and it reversed Aβ-induced injury when overexpressed in Aβ-treated cells (Ke et al., 2019). NEAT1 is frequently overexpressed in human tumors and proposed as a novel target for human cancer therapy and diagnosis by sponging miRNAs (Dong et al., 2018). According to previous studies, it also has a crucial role in HD and PD (Chanda et al., 2018; Liu and Lu, 2018). In AD studies, its increased expression levels were shown in brain tissues of AD patients, compared to controls (Spreafico et al., 2018).

SOX21-AS1

SOX21-AS1, similar to NEAT1, exacerbated Aβ-induced neuronal injury via sequestering miR-107 (Yue et al., 2020). SOX21-AS1 is a recently discovered lncRNA that can suppress neuronal apoptosis of hippocampal cells and mitigate oxidative stress in AD, hence, being involved as an agent in AD pathogenicity (Zhang L. et al., 2019).

It is noteworthy that, as mentioned above, the present study identified that miR-107 was at the center of three different loops, as shown in Figure 4, which suggests it is a key miRNA for both biological researches and ceRNA-based therapeutic purposes in AD studies. The miR-107 family is a group of evolutionarily conserved miRNAs that show high expression in the human cerebral cortex. Numerous studies have shown misregulation of this miRNA in AD brains (Wang et al., 2008; Gupta et al., 2017; Moncini et al., 2017). It has been reported that it may have a protective role in AD by preventing Aβ-induced blood–brain barrier (BBB) disruption, endothelial cell dysfunction (Liu et al., 2016), and Aβ-induced neuronal damage (Jiao et al., 2016; Shu et al., 2018; Chen et al., 2020). miR-107 shows a certain potential to be used as a biomarker in AD (Herrera-Espejo et al., 2019; Prendecki et al., 2019; Swarbrick et al., 2019). The ceRNA interactions are mediated by miRNAs, and altered miRNAs expression result in dysregulation of its competitive interactors. On the other hand, it is hypothesized that ceRNAs in the modules play a role in disease progression as a whole instead of acting individually (Chen et al., 2018a). Thus, these identified ceRNA modules comprising NEAT1, SOX21-AS1, BACE1-AS, miR-107, targets of miR-107, and BACE1 can be further assessed as potential ceRNA modules for ceRNA-based therapeutic purposes in AD.

Long Intergenic Non-protein Coding RNA 507 (LINC00507)

It was reported that LINC00507/miR-181c-5p/tau-tubulin kinase-1 (TTBK1)/MAPT axis regulated tau hyperphosphorylation via P25/P35/GSK3β signaling pathway (Yan et al., 2020). LincRNAs are a subclass of lncRNAs. LINC00507 has an age-dependent expression pattern and is specifically expressed in the primate cortex (Mills et al., 2016). MAPT encodes the tau protein, and TTBK1 is a CNS-specific protein kinase that involves in tau hyper-phosphorylation and deposition in AD (Ikezu and Ikezu, 2014). It also has been shown that P25/P35/GSK3β signaling pathway deteriorates tauopathy (Noble et al., 2003).

Long Intergenic Non-protein Coding RNA 94 (LINC00094)

As indicated in previous reports, LncRNA LINC00094 (called BRD3OS as well) is involved in regulating BBB penetrability in the AD microenvironment by sponging miR-224-5p and miR-497-5p, and SH3GL2 mRNA is targeted by both of them (Zhu et al., 2019). LINC00094 may reportedly act as a prognostic biomarker of lung cancer (Li et al., 2017). Additionally, microarray examination revealed the LINC00094 down-regulation in Memantine-incubated cells. As an N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist, memantine has received wide applications for AD treatment (Zhu et al., 2019). SH3GL2 encodes Endophilin-1, an endocytosis protein that has a marked increase in the AD brain and is responsible for Aβ-induced postsynaptic dysfunction (Yin Y. et al., 2019).

Long Intergenic Non-protein Coding RNA 1311 (LINC01311)

It was reported that the LINC01311/hsa-miR-146a-5p axis could operate as a functional regulator in AB1-42-stimulated apoptosis, proliferation slowdown, autophagy, and accumulated APP in human-lineage neurons (Fan et al., 2021). As a new lncRNA, LINC01311 was discovered throughout human genome-wide screening, which has an aberrant expression in human liver and prostate cancers (Zhu et al., 2016; Imada et al., 2020). However, the functional activity of LINC01311 has never been clarified in other human disorders.

RPPH1

Unlike the lncRNAs discussed above, RPPH1 apparently exerts a neuroprotective compensatory mode of action in AD pathology via two varying ceRNA axes: RPPH1/miR-122/WNT1 (Gu et al., 2020) and RPPH1/miR-326/pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM2) (Gu et al., 2021). Specifically, evidence indicates that it can mitigate Aβ25–35-stimulated neuronal damage, apoptosis, and endoplasmic reticulum stress (Gu et al., 2020, 2021). RPPH1 is the RNA component of RNase P, which plays a role in tRNA maturation in Archaea, Bacteria, and Eukarya (Evans et al., 2006). Wnt/β-catenin signaling has a confirmed essential function in developing AD. Huperzine A, which reversibly and selectively inhibits acetylcholinesterase and is utilized for AD treatment, has been reported to have a neuroprotecting impact by activating Wnt/β-catenin signaling in AD (Wang et al., 2011). As shown previously, the BBB failure in AD is caused by an impaired Wnt/β-catenin signaling (Liu et al., 2014). Besides, research indicates that activating the Wnt/β-catenin signaling is capable of protecting neuronal cells by regulating survival and c-myc, as well as apoptosis-linked proteins Bcl-2 and Bax (Jeong et al., 2014). As a glycolytic sensor, PKM2 has a crucial contribution to the dephosphorylation of phosphoenolpyruvate to pyruvate and catalysis of the final stage of glycolysis (Nakatsu et al., 2015). The emergence of recent documentation has highlighted that PKM2 is involved in AD. According to reports, oxidatively inactivated PKM2 had an association with the progress of AD from mild cognitive impairment (Butterfield et al., 2006). The poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase 1 could also modulate PKM2, indicating that the PKM2-linked glycolytic pathway has a contribution to AD (Martire et al., 2016).

Limitations of Scoping Review

A scoping review is different from a systematic review. It systematically studies the literature, quantitatively synthesizes the accomplishments and sums up the gaps in a particular field’s literature rather than evaluating it to offer a solution to a particular question. The approach is not substantially different from a systematic review, but an evaluation of methodological limitations or risk of bias of the evidence contained in a scoping review is not usually undertaken. A scoping review is often conducted before a systematic review to examine the literature and determine pertinent research topics to be addressed by a subsequent systematic review. Additionally, a scoping review does not seek to aggregate results via meta-analysis but rather maps the literature to determine themes, gaps, and patterns (Arksey and O’Malley, 2005; Levac et al., 2010). Because ceRNAs and AD is relatively new, a scoping review was conducted to evaluate the extent, scope, and type of research effort in this field to bring attention to topics where further study is required. Our results, however, should be interpreted with caution because we decided to perform a scoping review, which omits quality evaluations of the articles. The most significant limitation of this study is most likely the dearth of evidence available for review.

Conclusion

LncRNA-associated ceRNA regulation produces biologically significant effects in various diseases so it can elucidate the pathogenic procedures and offer options for new therapies. Thus, our efforts to understand different aspects of ceRNA regulatory mechanisms in AD pathogenesis provide new insights into the potential molecular targets, discover ceRNA-based biomarkers, and design ceRNA-based therapeutic applications.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author Contributions

MT, MR, and HS wrote the draft and revised it. MA, YD, OR, AJ, and NA collected the data and designed the tables and figures. All authors read the draft and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research protocol was approved and supported by Molecular Medicine Research Center, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences (Grant Number: 64401).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Agarwal, V., Bell, G. W., Nam, J.-W., and Bartel, D. P. (2015). Predicting effective microRNA target sites in mammalian mRNAs. eLife 4:e05005. doi: 10.7554/eLife.05005.028

Alkallas, R., Fish, L., Goodarzi, H., and Najafabadi, H. S. (2017). Inference of RNA decay rate from transcriptional profiling highlights the regulatory programs of Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Commun. 8:909. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00867-z

Amirkhah, R., Farazmand, A., Gupta, S. K., Ahmadi, H., Wolkenhauer, O., and Schmitz, U. (2015). Naïve Bayes classifier predicts functional microRNA target interactions in colorectal cancer. Mol. BioSyst. 11, 2126–2134. doi: 10.1039/C5MB00245A

Arksey, H., and O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 8, 19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616

Arun, G., Diermeier, S. D., and Spector, D. L. (2018). Therapeutic targeting of long non-coding RNAs in cancer. Trends Mol. Med. 24, 257–277. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2018.01.001

Bennett, C. F., Krainer, A. R., and Cleveland, D. W. (2019). Antisense oligonucleotide therapies for neurodegenerative diseases. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 42, 385–406. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-070918-050501

Bennett, C. F., and Swayze, E. E. (2010). RNA targeting therapeutics: molecular mechanisms of antisense oligonucleotides as a therapeutic platform. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 50, 259–293. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.010909.105654

Beyer, N., Coulson, D. T., Heggarty, S., Ravid, R., Irvine, G. B., Hellemans, J., et al. (2009). ZnT3 mRNA levels are reduced in Alzheimer’s disease post-mortem brain. Mol. Neurodegener. 4:53. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-4-53

Bird, L. M. (2014). Angelman syndrome: review of clinical and molecular aspects. Appl. Clin. Genet. 7, 93–104. doi: 10.2147/TACG.S57386

Busche, M. A., and Hyman, B. T. (2020). Synergy between amyloid-β and tau in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Neurosci. 23, 1183–1193. doi: 10.1038/s41593-020-0687-6

Butterfield, D. A., Poon, H. F., St Clair, D., Keller, J. N., Pierce, W. M., Klein, J. B., et al. (2006). Redox proteomics identification of oxidatively modified hippocampal proteins in mild cognitive impairment: insights into the development of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 22, 223–232. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.11.002

Cai, Y., Sun, Z., Jia, H., Luo, H., Ye, X., Wu, Q., et al. (2017). Rpph1 upregulates CDC42 expression and promotes hippocampal neuron dendritic spine formation by competing with miR-330-5p. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 10:27. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2017.00027

Cai, Y., and Wan, J. (2018). Competing endogenous RNA regulations in neurodegenerative disorders: current challenges and emerging insights. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 11:370. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2018.00370

Cao, B., Wang, T., Qu, Q., Kang, T., and Yang, Q. (2018). Long noncoding RNA SNHG1 promotes neuroinflammation in Parkinson’s disease via regulating miR-7/NLRP3 pathway. Neuroscience 388, 118–127. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2018.07.019

Cao, C., Zhou, S., and Hu, J. (2020). Long noncoding RNA MAGI2-AS3/miR-218-5p/GDPD5/SEC61A1 axis drives cellular proliferation and migration and confers cisplatin resistance in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 10, 1012–1023. doi: 10.1002/alr.22562

Causeret, F., Sumia, I., and Pierani, A. (2016). Kremen1 and Dickkopf1 control cell survival in a Wnt-independent manner. Cell Death Diff. 23, 323–332. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2015.100

Chanda, K., Das, S., Chakraborty, J., Bucha, S., Maitra, A., Chatterjee, R., et al. (2018). Altered levels of long NcRNAs Meg3 and Neat1 in cell and animal models Of Huntington’s disease. RNA Biol. 15, 1348–1363. doi: 10.1080/15476286.2018.1534524

Chen, W., Wu, L., Hu, Y., Jiang, L., Liang, N., Chen, J., et al. (2020). MicroRNA-107 ameliorates damage in a cell model of Alzheimer’s disease by mediating the FGF7/FGFR2/PI3K/Akt pathway. J. Mol. Neurosci. 70, 1589–1597. doi: 10.1007/s12031-020-01600-0

Chen, Y., Lian, Y. J., Ma, Y. Q., Wu, C. J., Zheng, Y. K., and Xie, N. C. (2018b). LncRNA SNHG1 promotes α-synuclein aggregation and toxicity by targeting miR-15b-5p to activate SIAH1 in human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells. Neurotoxicology 68, 212–221. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2017.12.001

Chen, Y., Chen, Q., Zou, J., Zhang, Y., and Bi, Z. (2018a). Construction and analysis of a ceRNA-ceRNA network reveals two potential prognostic modules regulated by hsa-miR-335-5p in osteosarcoma. Int. J. Mol. Med. 42, 1237–1246. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2018.3709

Corpas, R., Griñán-Ferré, C., Rodríguez-Farré, E., Pallàs, M., and Sanfeliu, C. (2019). Resveratrol induces brain resilience against Alzheimer neurodegeneration through proteostasis enhancement. Mol. Neurobiol. 56, 1502–1516. doi: 10.1007/s12035-018-1157-y

Crooke, S. T., Witztum, J. L., Bennett, C. F., and Baker, B. F. (2018). RNA-Targeted therapeutics. Cell Metab. 27, 714–739. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2018.03.004

Denzler, R., Agarwal, V., Stefano, J., Bartel, D. P., and Stoffel, M. (2014). Assessing the ceRNA hypothesis with quantitative measurements of miRNA and target abundance. Mol. Cell. 54, 766–776. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.03.045

Dong, P., Xiong, Y., Yue, J., Hanley, S. J. B., Kobayashi, N., Todo, Y., et al. (2018). Long Non-coding RNA NEAT1: a novel target for diagnosis and therapy in human tumors. Front. Genet. 9:471. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2018.00471

Evans, D., Marquez, S. M., and Pace, N. R. (2006). RNase P: interface of the RNA and protein worlds. Trends Biochem. Sci. 31, 333–341. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.04.007

Evans, H. M., Howe, P. R., and Wong, R. H. (2017). Effects of resveratrol on cognitive performance, mood and cerebrovascular function in post-menopausal women; a 14-week randomised placebo-controlled intervention trial. Nutrients 9:27. doi: 10.3390/nu9010027

Faghihi, M. A., Modarresi, F., Khalil, A. M., Wood, D. E., Sahagan, B. G., Morgan, T. E., et al. (2008). Expression of a noncoding RNA is elevated in Alzheimer’s disease and drives rapid feed-forward regulation of beta-secretase. Nat. Med. 14, 723–730. doi: 10.1038/nm1784

Faghihi, M. A., Zhang, M., Huang, J., Modarresi, F., Van der Brug, M. P., Nalls, M. A., et al. (2010). Evidence for natural antisense transcript-mediated inhibition of microRNA function. Genome Biol. 11:R56. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-5-r56

Fan, L., Mao, C., Hu, X., Zhang, S., Yang, Z., Hu, Z., et al. (2020). New insights into the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Neurol. 10:1312. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2019.01312

Fan, Y., Zhang, J., Zhuang, X., Geng, F., Jiang, G., and Yang, X. (2021). Epigenetic transcripts of LINC01311 and hsa-miR-146a-5p regulate neural development in a cellular model of Alzheimer’s disease. IUBMB Life 73, 916–926. doi: 10.1002/iub.2472

Gao, Y., Zhang, N., Lv, C., Li, N., Li, X., and Li, W. (2020). lncRNA SNHG1 knockdown alleviates amyloid-β-induced neuronal injury by regulating ZNF217 via sponging miR-361-3p in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 77, 85–98. doi: 10.3233/JAD-191303

Ge, Y., Song, X., Liu, J., Liu, C., and Xu, C. (2020). The combined therapy of berberine treatment with lncRNA BACE1-AS depletion attenuates Aβ(25-35) induced neuronal injury through regulating the expression of miR-132-3p in neuronal cells. Neurochem. Res. 45, 741–751. doi: 10.1007/s11064-019-02947-6

Gokulnath, P., de Cristofaro, T., Manipur, I., Di Palma, T., Soriano, A. A., Guarracino, M. R., et al. (2019). Long non-coding RNA MAGI2-AS3 is a new player with a tumor suppressive role in high grade serous ovarian carcinoma. Cancers 11:2008. doi: 10.3390/cancers11122008

Gomes, B. A. Q., Silva, J. P. B., Romeiro, C. F. R., Dos Santos, S. M., Rodrigues, C. A., Gonçalves, P. R., et al. (2018). Neuroprotective mechanisms of resveratrol in Alzheimer’s disease: role of SIRT1. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2018:8152373. doi: 10.1155/2018/8152373

Gu, R., Liu, R., Wang, L., Tang, M., Li, S. R., and Hu, X. (2021). LncRNA RPPH1 attenuates Aβ(25-35)-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress and apoptosis in SH-SY5Y cells via miR-326/PKM2. Int. J. Neurosci. 131, 425–432. doi: 10.1080/00207454.2020.1746307

Gu, R., Wang, L., Tang, M., Li, S. R., Liu, R., and Hu, X. (2020). LncRNA Rpph1 protects amyloid-β induced neuronal injury in SK-N-SH cells via miR-122/Wnt1 axis. Int. J. Neurosci. 130, 443–453. doi: 10.1080/00207454.2019.1692834

Gupta, P., Bhattacharjee, S., Sharma, A. R., Sharma, G., Lee, S. S., and Chakraborty, C. (2017). miRNAs in Alzheimer disease - a therapeutic perspective. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 14, 1198–1206. doi: 10.2174/1567205014666170829101016

He, J., Zhou, X., Li, L., and Han, Z. (2020). Long noncoding MAGI2-AS3 suppresses several cellular processes of lung squamous cell carcinoma cells by regulating miR-374a/b-5p/CADM2 Axis. Cancer Manag. Res. 12, 289–302. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S232595

He, W., Chi, S., Jin, X., Lu, J., Zheng, W., Yan, J., et al. (2020). Long non-coding RNA BACE1-AS modulates isoflurane-induced neurotoxicity to Alzheimer’s disease through sponging miR-214-3p. Neurochem. Res. 45, 2324–2335. doi: 10.1007/s11064-020-03091-2

Herrera-Espejo, S., Santos-Zorrozua, B., Álvarez-González, P., Lopez-Lopez, E., and Garcia-Orad, Á (2019). A systematic review of MicroRNA expression as biomarker of late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Neurobiol. 56, 8376–8391. doi: 10.1007/s12035-019-01676-9

Hsiao, J., Yuan, T. Y., Tsai, M. S., Lu, C. Y., Lin, Y. C., Lee, M. L., et al. (2016). Upregulation of haploinsufficient gene expression in the brain by targeting a long non-coding RNA improves seizure phenotype in a model of dravet syndrome. EBioMedicine 9, 257–277. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.05.011

Huang, L., Jiang, X., Wang, Z., Zhong, X., Tai, S., and Cui, Y. (2018). Small nucleolar RNA host gene 1: a new biomarker and therapeutic target for cancers. Pathol. Res. Pract. 214, 1247–1252. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2018.07.033

Huaying, C., Xing, J., Luya, J., Linhui, N., Di, S., and Xianjun, D. A. (2021). Signature of five long non-coding RNAs for predicting the prognosis of Alzheimer’s disease based on competing endogenous RNA networks. Front. Aging Neurosci. 12:598606. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2020.598606

Ikezu, S., and Ikezu, T. (2014). Tau-tubulin kinase. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 7:33. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2014.00033

Imada, E. L., Sanchez, D. F., Collado-Torres, L., Wilks, C., Matam, T., Dinalankara, W., et al. (2020). Recounting the FANTOM CAGE-associated transcriptome. Genome Res. 30, 1073–1081. doi: 10.1101/gr.254656.119

Jeong, J. K., Lee, J. H., Moon, J. H., Lee, Y. J., and Park, S. Y. (2014). Melatonin-mediated β-catenin activation protects neuron cells against prion protein-induced neurotoxicity. J. Pineal Res. 57, 427–434. doi: 10.1111/jpi.12182

Jiang, Q., Shan, K., Qun-Wang, X., Zhou, R.-M., Yang, H., Liu, C., et al. (2016). Long non-coding RNA-MIAT promotes neurovascular remodeling in the eye and brain. Oncotarget 7, 49688–49698. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10434

Jiao, Y., Kong, L., Yao, Y., Li, S., Tao, Z., Yan, Y., et al. (2016). Osthole decreases beta amyloid levels through up-regulation of miR-107 in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropharmacology 108, 332–344. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2016.04.046

Kang, S. S., Ahn, E. H., and Ye, K. (2020). Delta-secretase cleavage of Tau mediates its pathology and propagation in Alzheimer’s disease. Exp. Mol. Med. 52, 1275–1287. doi: 10.1038/s12276-020-00494-7

Ke, S., Yang, Z., Yang, F., Wang, X., Tan, J., and Liao, B. (2019). Long noncoding RNA NEAT1 aggravates Aβ-induced neuronal damage by targeting miR-107 in Alzheimer’s disease. Yonsei Med. J. 60, 640–650. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2019.60.7.640

Khvorova, A., and Wolfson, A. (2012). New competition in RNA regulation. Nat. Biotechnol. 30, 58–59. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2092

Kong, D., Yan, Y., He, X.-Y., Yang, H., Liang, B., Wang, J., et al. (2019). Effects of resveratrol on the mechanisms of antioxidants and estrogen in Alzheimer’s Disease. BioMed Res. Int. 2019:8983752. doi: 10.1155/2019/8983752

Krek, A., Grün, D., Poy, M. N., Wolf, R., Rosenberg, L., Epstein, E. J., et al. (2005). Combinatorial microRNA target predictions. Nat. Genet. 37, 495–500. doi: 10.1038/ng1536

Kumar, A., Ekavali, Chopra, K., Mukherjee, M., Pottabathini, R., and Dhull, D. K. (2015). Current knowledge and pharmacological profile of berberine: an update. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 761, 288–297. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2015.05.068

Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., and O’Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 5:69. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

Li, D., Zhang, J., Li, X., Chen, Y., Yu, F., and Liu, Q. (2021). Insights into lncRNAs in Alzheimer’s disease mechanisms. RNA Biol. 18, 1037–1047. doi: 10.1080/15476286.2020.1788848

Li, J. H., Liu, S., Zhou, H., Qu, L. H., and Yang, J. H. (2014). starBase v2.0: decoding miRNA-ceRNA, miRNA-ncRNA and protein-RNA interaction networks from large-scale CLIP-Seq data. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, D92–D97. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1248

Li, L., Xu, Y., Zhao, M., and Gao, Z. (2020). Neuro-protective roles of long non-coding RNA MALAT1 in Alzheimer’s disease with the involvement of the microRNA-30b/CNR1 network and the following PI3K/AKT activation. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 117:104545. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2020.104545

Li, S., Sun, X., Miao, S., Liu, J., and Jiao, W. (2017). Differential protein-coding gene and long noncoding RNA expression in smoking-related lung squamous cell carcinoma. Thorac. Cancer 8, 672–681. doi: 10.1111/1759-7714.12510

Li, X., Wang, S. W., Li, X. L., Yu, F. Y., and Cong, H. M. (2020). Knockdown of long non-coding RNA TUG1 depresses apoptosis of hippocampal neurons in Alzheimer’s disease by elevating microRNA-15a and repressing ROCK1 expression. Inflamm. Res. 69, 897–910. doi: 10.1007/s00011-020-01364-8

Liao, Y., Li, P., Wang, Y., Chen, H., Ning, S., and Su, D. (2020). Construction of asthma related competing endogenous RNA network revealed novel long non-coding RNAs and potential new drugs. Resp. Res. 21:14. doi: 10.1186/s12931-019-1257-x

Liu, L., Wan, W., Xia, S., Kalionis, B., and Li, Y. (2014). Dysfunctional Wnt/β-catenin signaling contributes to blood–brain barrier breakdown in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurochem. Int. 75, 19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2014.05.004

Liu, S., Li, J.-H., Wu, J., Zhou, K.-R., Zhou, H., Yang, J.-H., et al. (2015). StarScan: a web server for scanning small RNA targets from degradome sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, W480–W486. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv524

Liu, W., Cai, H., Lin, M., Zhu, L., Gao, L., Zhong, R., et al. (2016). MicroRNA-107 prevents amyloid-beta induced blood-brain barrier disruption and endothelial cell dysfunction by targeting Endophilin-1. Exp. Cell Res. 343, 248–257. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2016.03.026

Liu, Y., and Lu, Z. (2018). Long non-coding RNA NEAT1 mediates the toxic of Parkinson’s disease induced by MPTP/MPP+ via regulation of gene expression. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 45, 841–848. doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.12932

Lu, L., Dai, W.-Z., Zhu, X.-C., and Ma, T. (2021). Analysis of Serum miRNAs in Alzheimer’s disease. Am. J. Alzheimers Dis. Other Dement. 36:15333175211021712. doi: 10.1177/15333175211021712

Ma, N., Pan, J., Ye, X., Yu, B., Zhang, W., and Wan, J. (2019). Whole-transcriptome analysis of APP/PS1 mouse brain and identification of circRNA-miRNA-mRNA networks to investigate AD pathogenesis. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 18, 1049–1062. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2019.10.030

Ma, N., Tie, C., Yu, B., Zhang, W., and Wan, J. (2020). Identifying lncRNA-miRNA-mRNA networks to investigate Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis and therapy strategy. Aging 12, 2897–2920. doi: 10.18632/aging.102785

Ma, P., Li, Y., Zhang, W., Fang, F., Sun, J., Liu, M., et al. (2019). Long Non-coding RNA MALAT1 inhibits neuron apoptosis and neuroinflammation while stimulates neurite outgrowth and its correlation With MiR-125b Mediates PTGS2, CDK5 and FOXQ1 in Alzheimer’s disease. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 16, 596–612. doi: 10.2174/1567205016666190725130134

Martire, S., Fuso, A., Mosca, L., Forte, E., Correani, V., Fontana, M., et al. (2016). Bioenergetic impairment in animal and cellular models of Alzheimer’s disease: PARP-1 inhibition rescues metabolic dysfunctions. J. Alzheimers Dis. 54, 307–324. doi: 10.3233/JAD-151040

Meng, L., Ward, A. J., Chun, S., Bennett, C. F., Beaudet, A. L., and Rigo, F. (2015). Towards a therapy for Angelman syndrome by targeting a long non-coding RNA. Nature 518, 409–412. doi: 10.1038/nature13975

Mills, J. D., Ward, M., Chen, B. J., Iyer, A. M., Aronica, E., and Janitz, M. (2016). LINC00507 is specifically expressed in the primate cortex and has age-dependent expression patterns. J. Mol. Neurosci. 59, 431–439. doi: 10.1007/s12031-016-0745-4

Modarresi, F., Faghihi, M. A., Lopez-Toledano, M. A., Fatemi, R. P., Magistri, M., Brothers, S. P., et al. (2012). Inhibition of natural antisense transcripts in vivo results in gene-specific transcriptional upregulation. Nat. Biotechnol. 30, 453–459. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2158

Moncini, S., Lunghi, M., Valmadre, A., Grasso, M., Del Vescovo, V., Riva, P., et al. (2017). The miR-15/107 family of microRNA genes regulates CDK5R1/p35 with implications for Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis. Mol. Neurobiol. 54, 4329–4342. doi: 10.1007/s12035-016-0002-4

Moreno-García, L., López-Royo, T., Calvo, A. C., Toivonen, J. M., de la Torre, M., Moreno-Martínez, L., et al. (2020). Competing endogenous RNA networks as biomarkers in neurodegenerative diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21:9582. doi: 10.3390/ijms21249582

Mulvaney, J. F., Thompkins, C., Noda, T., Nishimura, K., Sun, W. W., Lin, S.-Y., et al. (2016). Kremen1 regulates mechanosensory hair cell development in the mammalian cochlea and the zebrafish lateral line. Sci. Rep. 6:31668. doi: 10.1038/srep31668

Nakatsu, D., Horiuchi, Y., Kano, F., Noguchi, Y., Sugawara, T., Takamoto, I., et al. (2015). L-cysteine reversibly inhibits glucose-induced biphasic insulin secretion and ATP production by inactivating PKM2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, E1067–E1076. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1417197112

Noble, W., Olm, V., Takata, K., Casey, E., Mary, O., Meyerson, J., et al. (2003). Cdk5 is a key factor in tau aggregation and tangle formation in vivo. Neuron 38, 555–565. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00259-9

Ou, G. Y., Lin, W. W., and Zhao, W. J. (2021). Construction of long noncoding RNA-associated ceRNA networks reveals potential biomarkers in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 82, 169–183. doi: 10.3233/JAD-210068

Padmakumar, S., Jones, G., Pawar, G., Khorkova, O., Hsiao, J., Kim, J., et al. (2021). Minimally invasive nasal depot (MIND) technique for direct BDNF AntagoNAT delivery to the brain. J. Control. Release 331, 176–186. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2021.01.027

Prendecki, M., Florczak-Wyspianska, J., Kowalska, M., Ilkowski, J., Grzelak, T., Bialas, K., et al. (2019). APOE genetic variants and apoE, miR-107 and miR-650 levels in Alzheimer’s disease. Folia Neuropathol. 57, 106–116. doi: 10.5114/fn.2019.84828

Quinlan, K. G., Verger, A., Yaswen, P., and Crossley, M. (2007). Amplification of zinc finger gene 217 (ZNF217) and cancer: when good fingers go bad. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1775, 333–340. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2007.05.001

Quinn, J. J., and Chang, H. Y. (2016). Unique features of long non-coding RNA biogenesis and function. Nat. Rev. Genet. 17, 47–62. doi: 10.1038/nrg.2015.10

Rezazadeh, M., Hosseinzadeh, H., Moradi, M., Salek Esfahani, B., Talebian, S., Parvin, S., et al. (2019). Genetic discoveries and advances in late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. J. Cell. Physiol. 234, 16873–16884. doi: 10.1002/jcp.28372

Ross, S. P., Baker, K. E., Fisher, A., Hoff, L., Pak, E. S., and Murashov, A. K. (2018). miRNA-431 prevents amyloid-β-induced synapse loss in neuronal cell culture model of Alzheimer’s disease by silencing Kremen1. Front. Cell Neurosci. 12:87. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2018.00087

Salmena, L., Poliseno, L., Tay, Y., Kats, L., and Pandolfi, P. P. (2011). A ceRNA hypothesis: the rosetta stone of a hidden RNA language? Cell 146, 353–358. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.014

Scoles, D. R., Minikel, E. V., and Pulst, S. M. (2019). Antisense oligonucleotides: a primer. Neurol. Genet. 5:e323. doi: 10.1212/NXG.0000000000000323

Sekar, S., Cuyugan, L., Adkins, J., Geiger, P., and Liang, W. S. (2018). Circular RNA expression and regulatory network prediction in posterior cingulate astrocytes in elderly subjects. BMC Genom. 19:340. doi: 10.1186/s12864-018-4670-5

Sen, R., Ghosal, S., Das, S., Balti, S., and Chakrabarti, J. (2014). Competing endogenous RNA: the key to posttranscriptional regulation. Sci. World J. 2014:896206. doi: 10.1155/2014/896206

Shannon, P., Markiel, A., Ozier, O., Baliga, N. S., Wang, J. T., Ramage, D., et al. (2003). Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 13, 2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303

Shu, B., Zhang, X., Du, G., Fu, Q., and Huang, L. (2018). MicroRNA-107 prevents amyloid-β-induced neurotoxicity and memory impairment in mice. Int. J. Mol. Med. 41, 1665–1672. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2017.3339

Shuwen, H., Qing, Z., Yan, Z., and Xi, Y. (2018). Competitive endogenous RNA in colorectal cancer: a systematic review. Gene 645, 157–162. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2017.12.036

Sims, R., Hill, M., and Williams, J. (2020). The multiplex model of the genetics of Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Neurosci. 23, 311–322. doi: 10.1038/s41593-020-0599-5

Spreafico, M., Grillo, B., Rusconi, F., Battaglioli, E., and Venturin, M. (2018). Multiple Layers of CDK5R1 regulation in Alzheimer’s disease implicate long non-coding RNAs. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19:2022. doi: 10.3390/ijms19072022

Stelzer, G., Rosen, N., Plaschkes, I., Zimmerman, S., Twik, M., Fishilevich, S., et al. (2016). The GeneCards suite: from gene data mining to disease genome sequence analyses. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform. 54, 1.30.1–1.3. doi: 10.1002/cpbi.5

Swarbrick, S., Wragg, N., Ghosh, S., and Stolzing, A. (2019). Systematic review of miRNA as biomarkers in Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Neurobiol. 56, 6156–6167. doi: 10.1007/s12035-019-1500-y

Tang, L., Xiang, Q., Xiang, J., and Li, J. (2021). lncRNA-associated competitive endogenous RNA regulatory network in an Aβ(25-35)-induced AD mouse model treated with tripterygium glycoside. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 17, 1531–1541. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S310271

Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., et al. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 169, 467–473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850

Wang, C.-Y., Zheng, W., Wang, T., Xie, J.-W., Wang, S.-L., Zhao, B.-L., et al. (2011). Huperzine A activates Wnt/β-catenin signaling and enhances the nonamyloidogenic pathway in an alzheimer transgenic mouse model. Neuropsychopharmacology 36, 1073–1089. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.245

Wang, H., Lu, B., and Chen, J. (2019). Knockdown of lncRNA SNHG1 attenuated Aβ(25-35)-inudced neuronal injury via regulating KREMEN1 by acting as a ceRNA of miR-137 in neuronal cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 518, 438–444. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.08.033

Wang, J., Zhou, T., Wang, T., and Wang, B. (2018). Suppression of lncRNA-ATB prevents amyloid-β-induced neurotoxicity in PC12 cells via regulating miR-200/ZNF217 axis. Biomed Pharmacother. 108, 707–715. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.08.155

Wang, L. K., Chen, X. F., He, D. D., Li, Y., and Fu, J. (2017). Dissection of functional lncRNAs in Alzheimer’s disease by construction and analysis of lncRNA-mRNA networks based on competitive endogenous RNAs. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 485, 569–576. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.11.143

Wang, W. X., Rajeev, B. W., Stromberg, A. J., Ren, N., Tang, G., Huang, Q., et al. (2008). The expression of microRNA miR-107 decreases early in Alzheimer’s disease and may accelerate disease progression through regulation of beta-site amyloid precursor protein-cleaving enzyme 1. J. Neurosci. 28, 1213–1223. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5065-07.2008

Wang, X., Wang, C., Geng, C., and Zhao, K. (2018). LncRNA XIST knockdown attenuates Aβ(25-35)-induced toxicity, oxidative stress, and apoptosis in primary cultured rat hippocampal neurons by targeting miR-132. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 11, 3915–3924.

Wang, Z., Xu, P., Chen, B., Zhang, Z., Zhang, C., Zhan, Q., et al. (2018). Identifying circRNA-associated-ceRNA networks in the hippocampus of Aß1-42-induced Alzheimer’s disease-like rats using microarray analysis. Aging 10, 775–788. doi: 10.18632/aging.101427

Winkle, M., El-Daly, S. M., Fabbri, M., and Calin, G. A. (2021). Noncoding RNA therapeutics — challenges and potential solutions. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 20, 629–651. doi: 10.1038/s41573-021-00219-z

Wurster, C. D., and Ludolph, A. C. (2018). Antisense oligonucleotides in neurological disorders. Ther. Adv. Neurol. Disord. 11:1756286418776932. doi: 10.1177/1756286418776932

Xie, Z., Culley, D. J., Dong, Y., Zhang, G., Zhang, B., Moir, R. D., et al. (2008). The common inhalation anesthetic isoflurane induces caspase activation and increases amyloid beta-protein level in vivo. Ann. Neurol. 64, 618–627. doi: 10.1002/ana.21548

Xie, Z., Dong, Y., Maeda, U., Alfille, P., Culley, D. J., Crosby, G., et al. (2006). The common inhalation anesthetic isoflurane induces apoptosis and increases amyloid beta protein levels. Anesthesiology 104, 988–994. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200605000-00015

Xie, Z., and Xu, Z. (2013). General anesthetics and β-amyloid protein. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 47, 140–146. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2012.08.002

Xu, H., and Jia, J. (2020). Immune-related hub genes and the competitive endogenous RNA network in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 77, 1255–1265. doi: 10.3233/JAD-200081

Yan, Y., Yan, H., Teng, Y., Wang, Q., Yang, P., Zhang, L., et al. (2020). Long non-coding RNA 00507/miRNA-181c-5p/TTBK1/MAPT axis regulates tau hyperphosphorylation in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Gene Med. 22:e3268. doi: 10.1002/jgm.3268

Yang, C., Wu, D., Gao, L., Liu, X., Jin, Y., Wang, D., et al. (2016). Competing endogenous RNA networks in human cancer: hypothesis, validation, and perspectives. Oncotarget 7, 13479–13490. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7266

Yin, Y., Cha, C., Wu, F., Li, J., Li, S., Zhu, X., et al. (2019). Endophilin 1 knockdown prevents synaptic dysfunction induced by oligomeric amyloid β. Mol. Med. Rep. 19, 4897–4905. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2019.10158

Yin, Z., Ma, T., Yan, J., Shi, N., Zhang, C., Lu, X., et al. (2019). LncRNA MAGI2-AS3 inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma cell proliferation and migration by targeting the miR-374b-5p/SMG1 signaling pathway. J. Cell. Physiol. 234, 18825–18836. doi: 10.1002/jcp.28521

Yu, L., Qian, S., and Wei, S. (2018). Identification of a noncoding RNA-mediated gene pair-based regulatory module in Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Med. Rep. 18, 2164–2170. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2018.9190

Yuan, N. N., Cai, C. Z., Wu, M. Y., Su, H. X., Li, M., and Lu, J. H. (2019). Neuroprotective effects of berberine in animal models of Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review of pre-clinical studies. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 19:109. doi: 10.1186/s12906-019-2510-z

Yue, D., Guanqun, G., Jingxin, L., Sen, S., Shuang, L., Yan, S., et al. (2020). Silencing of long noncoding RNA XIST attenuated Alzheimer’s disease-related BACE1 alteration through miR-124. Cell Biol. Int. 44, 630–636. doi: 10.1002/cbin.11263

Zeng, T., Ni, H., Yu, Y., Zhang, M., Wu, M., Wang, Q., et al. (2019). BACE1-AS prevents BACE1 mRNA degradation through the sequestration of BACE1-targeting miRNAs. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 98, 87–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2019.04.001

Zhang, J., and Wang, R. (2021). Deregulated lncRNA MAGI2-AS3 in Alzheimer’s disease attenuates amyloid-β induced neurotoxicity and neuroinflammation by sponging miR-374b-5p. Exp. Gerontol. 144:111180. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2020.111180

Zhang, L., Fang, Y., Cheng, X., Lian, Y. J., and Xu, H. L. (2019). Silencing of long noncoding RNA SOX21-AS1 relieves neuronal oxidative stress injury in mice with Alzheimer’s disease by Upregulating FZD3/5 via the Wnt signaling pathway. Mol. Neurobiol. 56, 3522–3537. doi: 10.1007/s12035-018-1299-y

Zhang, S., Zhu, D., Li, H., Li, H., Feng, C., and Zhang, W. (2017). Characterization of circRNA-Associated-ceRNA networks in a senescence-accelerated mouse prone 8 brain. Mol. Ther. 25, 2053–2061. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.06.009

Zhang, T., Shen, Y., Guo, Y., and Yao, J. (2021). Identification of key transcriptome biomarkers based on a vital gene module associated with pathological changes in Alzheimer’s disease. Aging 13, 14940–14967. doi: 10.18632/aging.203017

Zhang, Y., Yu, F., Bao, S., and Sun, J. (2019). Systematic characterization of circular RNA-associated CeRNA network identified novel circRNA biomarkers in Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 7:222. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2019.00222

Zhao, M. Y., Wang, G. Q., Wang, N. N., Yu, Q. Y., Liu, R. L., and Shi, W. Q. (2019). The long-non-coding RNA NEAT1 is a novel target for Alzheimer’s disease progression via miR-124/BACE1 axis. Neurol. Res. 41, 489–497. doi: 10.1080/01616412.2018.1548747

Zhou, B., Li, L., Qiu, X., Wu, J., Xu, L., and Shao, W. (2020). Long non-coding RNA ANRIL knockdown suppresses apoptosis and pro-inflammatory cytokines while enhancing neurite outgrowth via binding microRNA-125a in a cellular model of Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Med. Rep. 22, 1489–1497. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2020.11203

Zhou, Y., Xu, Z., Yu, Y., Cao, J., Qiao, Y., Qiao, H., et al. (2019). Comprehensive analysis of the lncRNA-associated ceRNA network identifies neuroinflammation biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Omics 15, 459–469. doi: 10.1039/C9MO00129H

Zhu, L., Lin, M., Ma, J., Liu, W., Gao, L., Wei, S., et al. (2019). The role of LINC00094/miR-224-5p (miR-497-5p)/Endophilin-1 axis in Memantine mediated protective effects on blood-brain barrier in AD microenvironment. J. Cell Mol. Med. 23, 3280–3292. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.14214

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, antisense oligonucleotides, competing endogenous RNA, long non-coding RNA, miRNA sponge

Citation: Sabaie H, Amirinejad N, Asadi MR, Jalaiei A, Daneshmandpour Y, Rezaei O, Taheri M and Rezazadeh M (2021) Molecular Insight Into the Therapeutic Potential of Long Non-coding RNA-Associated Competing Endogenous RNA Axes in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Systematic Scoping Review. Front. Aging Neurosci. 13:742242. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2021.742242

Received: 15 July 2021; Accepted: 25 October 2021;

Published: 25 November 2021.

Edited by:

Lilach Soreq, University College London, United KingdomReviewed by:

Zhifei Luo, University of California, San Diego, United StatesZerui Wang, Case Western Reserve University, United States

Zhonghua Dai, University of Southern California, United States

Copyright © 2021 Sabaie, Amirinejad, Asadi, Jalaiei, Daneshmandpour, Rezaei, Taheri and Rezazadeh. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mohammad Taheri, TW9oYW1tYWRfODIzQHlhaG9vLmNvbQ==; Maryam Rezazadeh, UmV6YXphZGVobUB0YnptZWQuYWMuaXI=

Hani Sabaie

Hani Sabaie Nazanin Amirinejad3

Nazanin Amirinejad3 Mohammad Reza Asadi

Mohammad Reza Asadi Mohammad Taheri

Mohammad Taheri