- 1Fujian Provincial Key Laboratory of Neurodegenerative Disease and Aging Research, School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, School of Medicine, Institute of Neuroscience, Xiamen University, Xiamen, China

- 2The United Innovation of Mengchao Hepatobiliary Technology Key Laboratory of Fujian Province, Mengchao Hepatobiliary Hospital of Fujian Medical University, Fuzhou, China

- 3Neuroscience Initiative, Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute, La Jolla, CA, United States

- 4Fujian Provincial Maternity and Children's Hospital of Fujian Medical University, Fuzhou, China

Oxidative stress is a common feature of neurodegenerative diseases and plays an important role in disease progression. Appoptosin is a pro-apoptotic protein that contributes to the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's disease and progressive supranuclear palsy. However, whether appoptosin mediates oxidative stress-induced neurotoxicity has yet to be determined. Here, we observe that appoptosin protein levels are induced by hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) exposure through the inhibition of proteasomal appoptosin degradation. Furthermore, we demonstrate that overexpression of appoptosin induces apoptosis through the JNK-FoxO1 pathway. Importantly, knockdown of appoptosin can ameliorate H2O2-induced JNK activation and apoptosis in primary neurons. Thus, we propose that appoptosin functions as an upstream regulator of the JNK-FoxO1 pathway, contributing to cell death in response to oxidative stress during neurodegeneration.

Introduction

Reactive Oxidative Species (ROS) are primarily generated in mitochondria as natural by-products of oxidative respiration. ROS normally play an important role in cell signaling and homeostasis (Devasagayam et al., 2004). Transient fluctuations in ROS are counterbalanced by antioxidant mechanisms within the cell comprising non-enzymatic molecules and enzymatic scavengers (Birben et al., 2012). However, ROS production can also be induced in cells, or absorbed directly from the extracellular environment when cells encounter environmental insults (Martindale and Holbrook, 2002; Ma et al., 2017). In these instances, ROS may be deleterious to cell function and survival.

In humans, the brain represents ~2% total body weight but disproportionately consumes ~20% of total oxygen and caloric intake (Jain et al., 2010). Due to an elevated rate of aerobic metabolism and potential insufficiencies in antioxidant and scavenging enzymes, the brain predisposes to be particularly vulnerable to oxidative stress insults. Despite its heterogenous nature, oxidative stress is a common feature of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's disease (AD), Parkinson's disease (PD), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and Huntington's disease (HD) (Ma et al., 2017; Cao et al., 2018). In addition, it has been proposed that several key proteins implicated in these neurodegenerative disorders (Aβ in AD, α-synuclein in PD, mSOD1 in ALS, frataxin in Friedreich's ataxia and α-B-crystallin in cataracts), may feature aberrant accumulation of Cu2+ and Fe3+ which catalyze the conversion of O2 to ROS, thereby exposing neurons to oxidative stress (Barnham et al., 2004; Zhou and Tan, 2017).

Appoptosin is a protein that resides in the mitochondrial inner membrane, and facilitates the exchange of glycine and 5-aminolevulinic acid between the cytosol and mitochondria during heme synthesis (Guernsey et al., 2009). Mutations in Appoptosin have been reported to be genetically linked to congenital sideroblastic anemia (Guernsey et al., 2009; Kannengiesser et al., 2011). We have previously demonstrated that appoptosin is a pro-apoptotic protein that can activate intrinsic caspase cascades, leading to neuronal apoptosis (Zhang et al., 2012). In addition, appoptosin levels are found to be increased in neurodegenerative diseases such as AD and progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), and under oxidative conditions such as rodent stroke models and Aβ- or glutamate-treated neurons (Zhang et al., 2012; Zhao et al., 2015). However, it remains unclear how appoptosin is upregulated to cause cell death in neurodegeneration or under oxidative stress conditions. Here, we find that appoptosin levels are induced with exposure to H2O2, where appoptosin turnover is attenuated through proteasomal degradation with reactive oxygen stress. Moreover, we find that appoptosin mediates activation of ROS-induced JNK/FoxO1 pathways. Together, these results implicate appoptosin as an important mediator of ROS-induced signal transduction pathways and define pathways that regulate appoptosin expression. Given that appoptosin upregulation triggers pathogenic effects in AD and PSP, our results suggest that antioxidants may reverse neurodegeneration by mediating appoptosin turnover.

Materials and Methods

Cells, Vectors, Antibodies, and Reagents

HEK293T and SY5Y cells were maintained in high glucose DMEM with 10% FBS and penicillin/streptomycin. Primary cortical neurons from embryonic day 17 (E17) mouse embryos were maintained in neurobasal medium supplemented with B27 and 0.8 mM Glutamine.

The vector expressing myc-appoptosin was generated previously (Zhang et al., 2012). A FLAG-tagged control vector and vectors expressing FoxO1, FoxO1-AAA (T24A, S256A, and S319A) and FoxO1 short hairpin RNA (shRNA) were kindly provided by Dr. Jie Zhang (Institute of Neuroscience, Xiamen University). The HA-Ub vector was kindly provided by Dr. Hongrui Wang (School of Life Sciences, Xiamen University). Gene-specific shRNA sequences were designed using the Genelink website (www.genelink.com/sirna/shRNAi.asp) and annealed shRNAs were inserted into the pLL3.7 vector. Three different shRNA-expressing constructs were generated, and RNA downregulation was tested by real-time PCR and western-blot. Sequences targeting appoptosin in constructs showing RNAi activity were as follows: Human appoptosin 5′-GGATGTTGGCTGTACTCTT-3′ and 5′-ATTCAGAACTCACGTCCGT-3′; mouse appoptosin 5′-gtgatcaagacacgctatg-3′; Scrambled shRNA 5′-GCCATATGTTCGAGACTCT-3′.

The following antibodies were used in this study: anti-appoptosin (#ab133614) from Abcam; anti-Myc (9E10, sc-40) from Santa Cruz; anti-tubulin (MABT205) from Millipore; anti-cleaved PARP (#5625), anti-AKT (#4691), anti-β-catenin (#8480), anti-β-actin (#8457), anti-cleaved caspase-3 (#9661), anti-FoxO1 (#2880), anti-p-JNK (Thr183/Tyr185) (#9251), and anti-p-c-Jun (Ser73) (#3270) from Cell Signaling Technology. Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) secondary antibody (#31460) and HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L) secondary antibody (#31430) were from Thermo Fisher Scientific.

Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), nicotinamide (NAM), and resveratrol were from Bio Basic Inc. Cycloheximide (CHX), MG132, SP600125, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) and 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) were from Sigma Aldrich. Protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails were from Roche.

Vector Transfection

HEK293T cells were transfected using Turbofect (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer's instructions. For transient co-expression of shRNAs and proteins, cells were firstly transfected with shRNA-expressing plasmids for 24 h, and subsequently with overexpression plasmids for an additional 24 h.

Real-Time PCR

RNA was extracted using TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen). Reverse transcription was performed using the ReverTra Ace qPCR RT Kit (Toyobo). Equal amounts of cDNA from each sample were subjected to real-time PCR experiments. Primers used in this study were as follows:

human appoptosin:

forward primer: 5′-GTCGGAGACACGGTGGAAAC-3′;

reverse primer: 5′-GCCAACATCCCAACACGTCTA-3′;

mouse appoptosin:

forward primer: 5′-GAAGGTGGTTCGCACAGAAAG-3′;

reverse primer: 5′-CCTCGCAAGAAATACTGCTTCG-3′;

18S:

forward primer: 5′-CGACGACCCATTCGAACGTCT-3′;

reverse primer: 5′-CTCTCCGGAATCGAACCCTGA-3′.

Mitochondria Isolation

The cell mitochondria isolation kit was purchased from Beyotime. Mitochondria-cytosol fractionation was performed following manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, cells were pelleted by centrifugation at 600 g for 5 min at 4°C, re-suspended in mitochondrial isolation solution, and homogenized on ice using a tight-fitting pestle attached to a homogenizer. The homogenate was then centrifuged at different speeds to separate intact cells, mitochondria, and cytosol fractions.

Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) Packaging and Infection

AAV was packaged by Obio Technology (Shanghai) and supplied in liquid form (multiplicity of infection (MOI) equals to 1 × 1012). Primary cortical neurons were cultured and infected with AAV particles (MOI equals to 2 × 109) on day 3 in vitro (DIV) and incubated for an additional 6 days before subsequent treatment.

Western Blot

Cells were lysed in TNEN lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 1% Nonidet P-40), and supplemented with a protease inhibitor mixture. Equal amounts of protein lysates were resolved in SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes, and probed with antibodies as indicated. Relative intensity of protein bands was quantified by densitometry with Image J.

Cellular ROS Assay

Cellular ROS levels were evaluated by oxidation sensitive fluorescent probe DCFH-DA. Briefly, HEK293T cells were transfected with control or appoptosin plasmid for 24 h. After washing with PBS for three times, cells were incubated with cell culture media containing 10 μM DCFH-DA for 30 min. Cells were then washed with PBS for another three times. Fluorescence was observed under a fluorescence microscope; and fluorescence intensity was measured by Image J.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 5 software. Results are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Unpaired t-test, one way or two-way ANOVA was used to assess statistical significance between groups.

Results

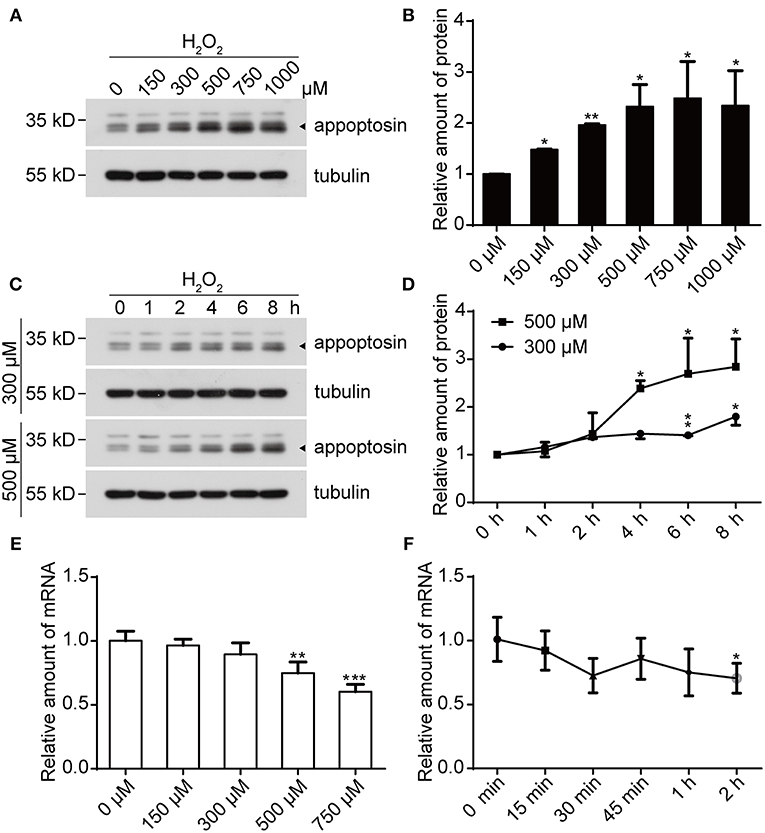

H2O2 Treatment Elevates Appoptosin Protein Levels

We previously reported that appoptosin is upregulated in primary cortical neurons after Aβ or glutamate exposure (Zhang et al., 2012). Because both Aβ (Behl et al., 1994) and glutamate (Parfenova et al., 2006) partially exert toxic effects through oxidative stress, it is likely that appoptosin expression is regulated through pathological oxidative insults. To test this, we treated cells with H2O2, a common membrane-permeable oxidant which is catalytically converted to reactive hydroxyl radicals (•OH) (Valko et al., 2005; Bienert et al., 2007). We found that exposure of HEK293T (Figures 1A,B) and SY5Y (Supplementary Figure 1) cells to H2O2 resulted in increased appoptosin levels in a dose- and time-dependent manner (Figures 1C,D). Interestingly, appoptosin mRNA levels were slightly reduced in a dose- (Figure 1E) and time-dependent (Figure 1F) manner upon H2O2 treatment. These results suggest that H2O2-dependent induction of appoptosin levels occurs through appoptosin-associated translation or turnover, rather than modulation of appoptosin mRNA transcripts.

Figure 1. H2O2 treatment increases appoptosin protein levels. (A) HEK293T cells were exposed to varying H2O2 concentrations for 8 h. Appoptosin protein levels were analyzed by western-blot. (B) Quantification of results from (A). (C) HEK293T cells were treated with 300 or 500 μM H2O2 for the time duration indicated. Appoptosin protein levels were determined by western-blot. (D) Quantification of results from (C). (E) HEK293T cells were treated with increasing H2O2 concentrations for 8 h and appoptosin mRNA levels were determined by quantitative real-time PCR analysis. (F) Appoptosin mRNA levels in HEK293T cells treated with 300 μM of H2O2 for the time duration indicated as measured by quantitative real-time PCR. n ≥ 3; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 (one-way ANOVA).

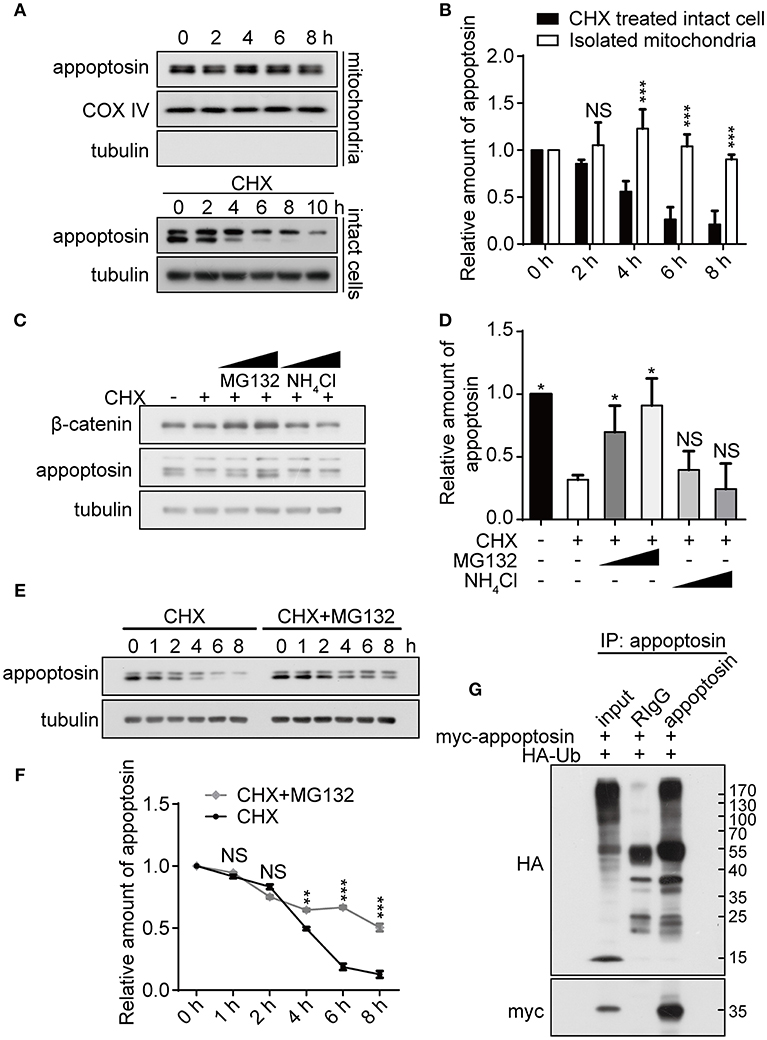

Appoptosin Is Degraded Through the Proteasomal Degradation Pathway

As previous studies have established that severe oxidative stress has an inhibitory effect on protein translation (Patel et al., 2002; Shenton et al., 2006; Ling and Soll, 2010), we characterized mechanisms underlying appoptosin degradation and stability. Appoptosin is an intra-mitochondrial transporter localized in the mitochondrial inner membrane. Mitochondrial proteins can be degraded by intrinsic mitochondrial proteases, or through lysosome or ubiquitin-proteasome systems (Ashrafi and Schwarz, 2013). To determine whether appoptosin is degraded through intrinsic mitochondrial pathways, we isolated mitochondria from HEK293T cells and assayed protein stability at 37°C at varying timepoints by immunoblot as described previously (Azzu et al., 2008). Minimal appoptosin turnover was observed in isolated mitochondria (Figures 2A,B). However, when intact HEK293T cells were incubated with cycloheximide (CHX) to inhibit protein synthesis, appoptosin was found to be rapidly degraded with a half-life of ~4 h (Figures 2A,B). These results suggest that appoptosin degradation is regulated by non-mitochondria associated pathways. Although the mitochondria inner membrane and lumen are spatially separated from ubiquitin-proteasomal machinery in the cytosol, cumulative evidence indicates that the ubiquitin-proteasome system is an important regulator for mitochondrial quality control. Proteins residing in the mitochondrial outer-membrane (Karbowski and Youle, 2011; Yoshii et al., 2011), inter-membrane space (Bragoszewski et al., 2013), and inner-membrane (Azzu and Brand, 2010) have been reported to be degraded through the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Here, we also pharmacologically inhibited proteasome and lysosome function with MG132 (10 or 20 μM) and NH4Cl (20 or 30 mM), respectively, in HEK293T (Figures 2C,D) and SY5Y (Supplementary Figure 2) cells. CHX-mediated inhibition of protein synthesis dramatically decreased appoptosin levels, which was dose-dependently reversed by MG132 but not NH4Cl. In addition, MG132 treatment significantly reduced appoptosin turnover kinetics (Figures 2E,F). These results indicate that proteasomal mechanisms also mediate appoptosin turnover and stability.

Figure 2. Appoptosin is degraded through the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. (A) Appoptosin levels in isolated mitochondria or intact cells treated with cycloheximide (CHX) as determined by western-blot. (B) Quantification of results from (A). (C) HEK293T cells were treated with DMSO alone (–), DMSO+CHX (50 μM), CHX+MG132 (10 and 20 μM), and CHX+NH4Cl (20 and 30 mM) for 8 h. β-catenin and appoptosin levels were determined by western-blot. (D) Quantification of results from (C). (E) HEK293T cells were treated with CHX or CHX+MG132 (10 μM) for various time periods. Appoptosin levels were analyzed by western-blot. (F) Quantification of results from (E). (G) HEK293T cells were co-transfected with HA-ubiquitin (Ub) and myc-appoptosin plasmids for 24 h. Equal protein amounts of cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) with an appoptosin antibody or rabbit IgG, and then western-blot with HA and myc antibodies. Ten percent of lysates used for IP was immunoblotted in inputs. n ≥ 3; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 (unpaired t-test or two-way ANOVA).

Since poly-ubiquitination is the obligatory initiating step during proteasome-mediated protein turnover (Murakami et al., 1992), immuno-precipitation was performed to determine whether appoptosin could be subjected to ubiquitination. Our results indicate that ubiquitin coprecipitated with appoptosin in HEK293T cells, confirming that appoptosin is indeed ubiquitinated (Figure 2G). Taken together, our results suggest that appoptosin is primarily degraded through the proteasome pathway.

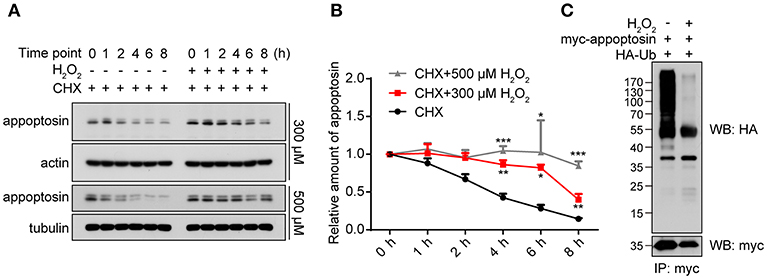

H2O2 Inhibits Appoptosin Turnover

As a fundamental component that mediates cellular protein degradation (Davies, 2001; Jung and Grune, 2008), proteasomal function is potentially impaired during aging (Bulteau et al., 2000; Carrard et al., 2002) and under severe oxidative stress (Breusing and Grune, 2008; Wang et al., 2010). Moreover, activity of E3 ubiquitin ligases has been reported to be diminished under oxidative stress, leading to reduced ubiquitination and aberrant stabilization/accumulation of various protein species (Banerjee et al., 2010; Messina et al., 2012). We therefore tested whether H2O2 stabilizes appoptosin through the inhibition of proteasome-mediated degradation pathways. Our results indicate that appoptosin turnover kinetics were dose-dependently impaired by H2O2 (Figures 3A,B). In addition, H2O2 dramatically inhibited appoptosin ubiquitin conjugation (Figure 3C), indicating that the proteasomal degradation of appoptosin may be impaired under oxidative stress.

Figure 3. Appoptosin turnover is delayed under oxidative stress. (A) HEK293T cells were treated with cycloheximide (CHX) or CHX+H2O2 (300 or 500 μM) for the time indicated. Appoptosin levels were determined by western-blot. (B) Quantification of results from (A). (C) HEK293T cells were co-transfected with HA-ubiquitin (Ub) and myc-appoptosin plasmids for 24 h. Cells were then treated with or without 300 μM H2O2 for 8 h. Equal protein amounts of cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) with a myc antibody and then western blot with HA and myc antibodies. n ≥ 3; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 (two-way ANOVA).

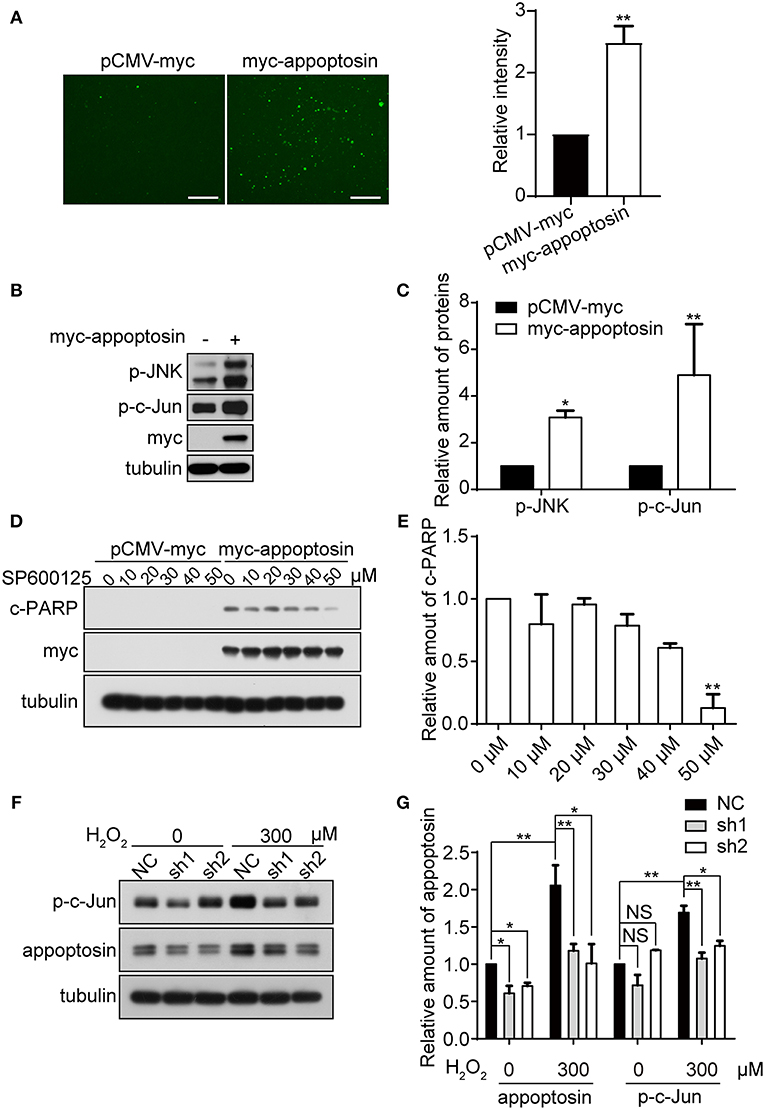

Appoptosin Mediates the JNK Pathway Activation Under Oxidative Stress

Oxidative stress is tightly linked to downstream signaling cascades to regulate cell growth, senescence, and apoptosis (Martindale and Holbrook, 2002). We have previously shown that overexpression of appoptosin leads to aberrant overproduction of heme, and release of ROS (Zhang et al., 2012). Here we confirmed the effects of appoptosin overexpression on promoting ROS production, as evidenced by DCFH-DA staining (Figure 4A).

Figure 4. Appoptosin mediates induction of the JNK pathway with oxidative stress. (A) HEK293T cells were transfected with pCMV-myc or myc-appoptosin for 24 h. Cells were then washed and incubated with DCFH-DA (fluorescent probe as indicator of ROS) for 30 min. Fluorescence intensity was measured by Image J for comparison. Scale bar: 200 μm. (B) HEK293T cells were transfected with control or myc-appoptosin plasmids for 24 h. Cell lysates were analyzed for phosphorylated JNK (p-JNK) and phosphorylated c-Jun (p-c-Jun) by western-blot. (C) Quantification of results from (B). (D) HEK293T cells were transfected with control pCMV-myc or myc-appoptosin plasmids for 5 h, and treated with DMSO or the JNK inhibitor SP600125 as indicated for additional 19 h. Cleaved PARP (c-PARP) and myc-appoptosin levels were analyzed by western-blot. (E) Quantification of results from (D). (F) Cells were transfected with plasmids expressing scrambled shRNA (NC) or appoptosin shRNAs (sh1 and sh2) for 24 h, and treated with 0 or 300 μM H2O2. Levels of p-c-Jun and appoptosin were determined by western-blot. (G) Quantification of results from (F). n ≥ 3; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (one-way or two-way ANOVA).

Although overexpression of appoptosin eventually activates intrinsic caspase-dependent apoptotic pathways (Zhang et al., 2012), the role of appoptosin in downstream ROS-responsive signaling pathways has not been elucidated. Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways, including extracellular signal regulated kinases (ERK-1/2), c-Jun NH2-terminal kinases (JNK-1/2/3), and p38 MAPK proteins (p38 α/β/γ/δ), are related kinase cascades that connect numerous intra- and extra-cellular signaling pathways. JNK-MAPK proteins are strongly tied to stress response (Martindale and Holbrook, 2002), and numerous reports indicate that JNK-MAPK proteins are involved in the regulation of apoptosis during oxidative injury (Yin et al., 2000; Hreniuk et al., 2001; Kanayama and Miyamoto, 2007; Chen et al., 2008; Conde De La Rosa et al., 2008). Here, we observed that overexpression of appoptosin in HEK293T cells activated JNK and its downstream substrate c-Jun, as evidenced by upregulated p-JNK and p-c-Jun (Figures 4B,C). Pharmacological inhibition of JNK by SP600125 dose-dependently reduced appoptosin-induced apoptosis (Figures 4D,E). H2O2 treatment significantly increased p-c-Jun levels, which was fully reversed with shRNA-mediated appoptosin depletion (Figures 4F,G). These results suggest that appoptosin mediates H2O2-induced apoptosis through the JNK-MAPK pathway.

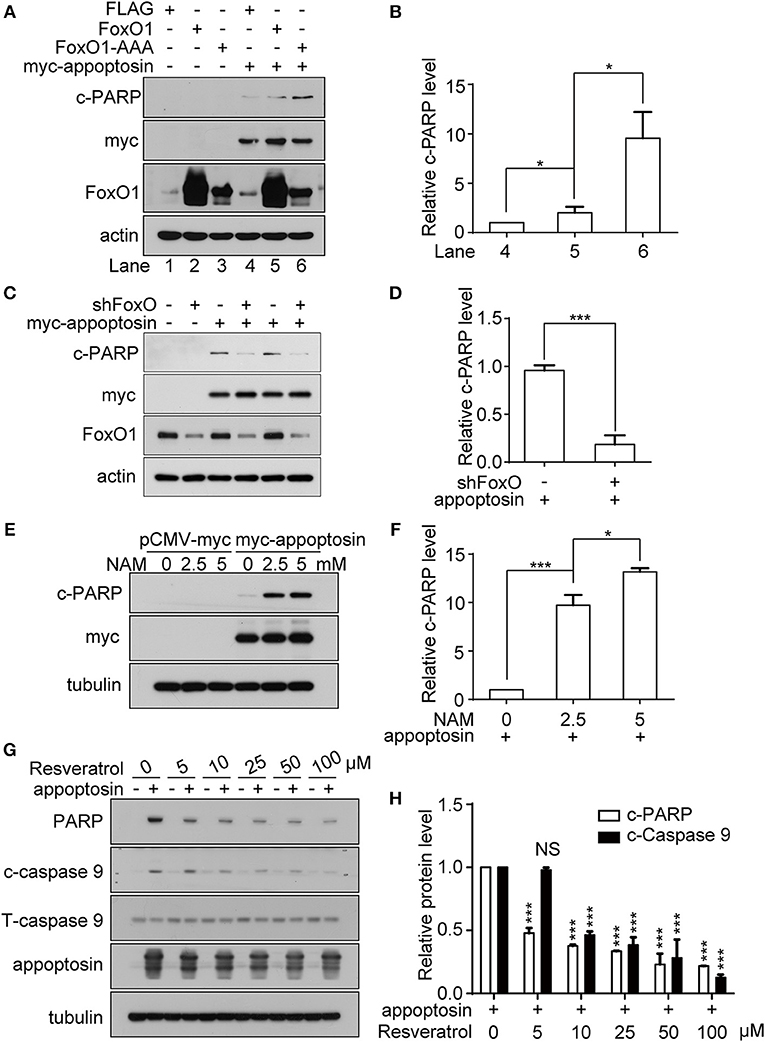

FoxO1 Mediates Appoptosin-Induced Apoptosis

It has been previously established that the class O of forkhead box transcription factor, FoxO1 can trigger apoptosis in response to oxidative stress through the expression of apoptotic proteins such as FasL, Puma, TRAIL, and Bim (Cui et al., 2009). Studies have also shown that JNK can act as an upstream activator of FoxO-related transcription factors multiple levels (Van Der Horst and Burgering, 2007; Karpac and Jasper, 2009), to modulate cell metabolism, cell cycle inhibition, oxidative stress resistance, and/or apoptosis. Although we observe that overexpression of FoxO1 or its active form FoxO1-AAA (mutations at the AKT phosphorylation sites, which lead to nucleus retention) alone had no effect on apoptosis, co-expression of appoptosin together with FoxO1-AAA significantly potentiated appoptosin-induced apoptosis (Figures 5A,B). In contrast, downregulating FoxO1 expression by shRNA significantly inhibited appoptosin-induced apoptosis (Figures 5C,D).

Figure 5. FoxO1 potentiates appoptosin-induced apoptosis. (A) HEK293T cells were transfected with plasmids expressing FLAG (control vector), FoxO1, or FoxO1-AAA plasmids for 24 h, and subsequently transfected with pCMV-myc or myc-appoptosin for another 24 h. Cleaved PARP (c-PARP), myc-appoptosin and FoxO1 levels were analyzed by western-blot. (B) Quantitative analysis of c-PARP levels in (A). (C) HEK293T cells were transfected with scrambled control shRNA or FoxO1-shRNA (shFoxO) for 24 h, and subsequently transfected with pCMV-myc or myc-appoptosin for additional 24 h. Indicated protein levels were analyzed by western-blot. (D) Quantification of results from c-PARP levels in (C). (E) HEK293T cells were transfected with pCMV-myc or myc-appoptosin for 6 h, and subsequently treated with the SIRT1 inhibitor NAM for 18 h as indicated. Levels of c-PARP and myc-appoptosin were determined by western-blot. (F) Quantification of results from c-PARP levels in (E). (G) HEK293T cells were transfected with pCMV-myc or myc-appoptosin for 6 h, and subsequently treated with the SIRT1 activator resveratrol for 18 h as indicated. Levels of c-PARP, cleaved caspase 9 (c-caspase 9), total caspase 9 (T-caspase 9) and appoptosin were analyzed by western-blot. (H) Quantification of results from c-PARP and c-caspase 9 levels in (G). n ≥ 3; *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001 (one-way ANOVA).

Various post-translational modifications have been observed in FoxO1, including phosphorylation, acetylation, ubiquitination, and methylation (Calnan and Brunet, 2008). Among these, FoxO1 acetylation enhances the expression of genes involved in apoptotic pathways (Yang et al., 2009), whereas FoxO1 deacetylation promotes transcription of genes involved in DNA repair and stress resistance. Nicotinamide (NAM) is a well-known inhibitor of SIRT1 (Avalos et al., 2005), which modulates FoxO1 activity through deacetylation (Hariharan et al., 2010). We found that although NAM treatment had no effect on apoptosis in normal cells, NAM potentiated apoptosis in cells overexpressing appoptosin in a dose-dependent manner (Figures 5E,F). Conversely, resveratrol, a well-documented SIRT1 activator (Borra et al., 2005), dose-dependently inhibited appoptosin-induced apoptosis (Figures 5G,H). Together, these results indicate that the downstream JNK pathway effector, FoxO1, can potentiate appoptosin-associated apoptosis pathways.

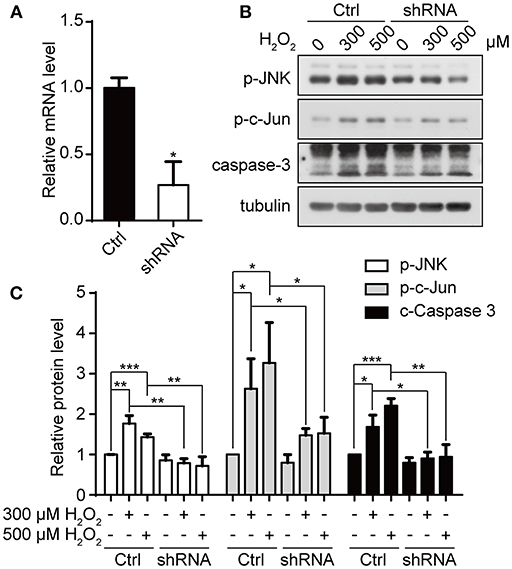

Downregulation of Appoptosin Protects Primary Neurons From Oxidative Injury

We have previously shown that downregulation of appoptosin can protect neurons from Aβ and glutamatergic toxicity (Zhang et al., 2012). To investigate the effect of appoptosin downregulation on neuronal injury induced by oxidative stress, we transduced primary neurons with AAV expressing appoptosin-shRNA or control AAV on DIV-3 for 6 days, and subsequently exposed neurons to H2O2 for 4 h. Appoptosin mRNA levels in appoptosin shRNA-expressing cells were reduced to ~25% of the control (Figure 6A). Consistent with results from HEK293T cells, H2O2-induced JNK/c-Jun activation and caspase-3 cleavage were reversed by appoptosin downregulation (Figures 6B,C). These results indicate that reducing appoptosin expression can protect neurons from oxidative injury.

Figure 6. Downregulation of appoptosin protects primary neurons from oxidative injury. (A) Mouse primary neurons were infected with AAVs carrying scrambled control shRNA (Ctrl-AAV) or AAVs carrying an shRNA targeting appoptosin (shRNA-AAV) for 72 h. Appoptosin mRNA levels in neurons infected with Ctrl-AAV or shRNA-AAV were determined by quantitative real-time PCR. (B) Neurons infected with Ctrl-AAV or shRNA-AAV were treated with H2O2 (0, 300, or 500 μM) for 4 h. Levels of p-JNK, p-c-Jun and caspase 3 were analyzed by western-blot. (C) Quantification of results from (B). n ≥ 3; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 (one-way ANOVA).

Discussion

ROS relay signals as important second messengers, and serve important regulatory functions in cell growth and differentiation at very low concentrations (Suzuki et al., 1997; Sauer et al., 2001). However, excessive ROS-induced oxidative stress impairs vital cell components, leading to cell cycle arrest and eventual apoptosis or necrosis. These degenerative events are important contributors to multiple diseases and are particularly important in a spectrum of neurodegenerative disorders.

Mitochondria are the primary source for ROS generation (Circu and Aw, 2010), and are therefore immediately susceptible to ROS-mediated oxidative damage. With increasing ROS levels, organellar damage within mitochondria includes oxidative damage of mitochondrial DNA, lipids, and proteins, which can have deleterious effects on cell functions (Fariss et al., 2005; Gibson, 2005; Circu et al., 2009; Rachek et al., 2009; Andreazza et al., 2010). Additionally, mitochondria play a central role in mediating intrinsic apoptotic pathways. As a component of the mitochondrial inner membrane, appoptosin and its overexpression have recently been shown to induce apoptosis by increasing heme synthesis, ROS production and cytochrome c release. Appoptosin expression is found to be pathologically upregulated in AD and PSP disorders that are also associated with oxidative stress. In the present study, we found that appoptosin protein levels accumulated under oxidative stress through impaired proteasome-mediated appoptosin turnover. H2O2-induced effects on protein degradation appear to be specific to appoptosin, since H2O2 treatment had no effect on other proteasomal substrates such as SIRT1 (Caito et al., 2010) and FoxO1 (Huang et al., 2005). In addition, we found that appoptosin could mediate the JNK activation induced by oxidative stress, and downregulation of appoptosin attenuated H2O2-induced apoptosis. JNK is activated by the MAPKKK (ASK1) during oxidative stress and is believed to be a central regulator of both intrinsic and extrinsic apoptotic pathways (Sinha et al., 2013). JNK directly or indirectly activates apoptotic pathways by phosphorylating effector proteins (such as Bim, Bad, and Bmf) or transcription factors [such as c-Jun, FoxOs, p53, and c-myc (Sinha et al., 2013)]. Given its role in ROS production shown previously (Chambers and Lograsso, 2011), it is likely that appoptosin activates JNK through ROS induction and mitochondrial fission (Zhang et al., 2016).

Here we observe that overexpression of the transcription factor FoxO1 potentiates appoptosin-induced apoptosis. Downregulation of FoxO1 likewise attenuated appoptosin-induced apoptosis, and the SIRT1 inhibitor NAM promoted appoptosin-induced apoptosis, whereas treatment with the SIRT1 activator resveratrol blocked appoptosin-induced apoptosis. As SIRT1 modulates FoxO1-dependent transcriptional activity to promote expression of genes involved in stress resistance while inhibiting genes that trigger apoptosis, our results indicate that FoxO1 functions downstream of appoptosin. These results produce a working model where FoxO1 functions downstream of JNK, whereby FoxO1 triggers apoptosis under oxidative stress.

Data Availability

The data for this manuscript will be available from the authors to qualified researchers upon reasonable request. Requests for access to the data should be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics Statement

All animal procedures were approved by the Laboratory Animal Management and Ethics Committee of Xiamen University.

Author Contributions

CZ, ZT, and YX performed the experiments. CZ, YZ, and XZ interpreted experimental data. YZ, TH, and HX reviewed the manuscript. ZL, HL, and DC edited the manuscript. CZ, Y-wZ, and XZ wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from National Key Research and Development Program of China (2016YFC1305903 and 2018YFC2000400 to Y-wZ), National Natural Science Foundation of China (81771377 and U1705285 to Y-wZ), Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (20720180049 to Y-wZ), National Institutes of Health (R01 AG061875 and R21 AG059217 to TH), Cure Alzheimer's Fund to HX, BrightFocus Foundation (A2018214F to YZ), Scientific Foundation of Fujian Health and Family Planning Department (2017-2-60 to CZ), Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province (2018J01139 to CZ), Startup Fund for Scientific Research of Fujian Medical University (2016QH080 to CZ), and Joint Funds for the Innovation of Science and Technology of Fujian Province (2018Y9120 to CZ).

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnagi.2019.00243/full#supplementary-material

References

Andreazza, A. C., Shao, L., Wang, J. F., and Young, L. T. (2010). Mitochondrial complex I activity and oxidative damage to mitochondrial proteins in the prefrontal cortex of patients with bipolar disorder. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 67, 360–368. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.22

Ashrafi, G., and Schwarz, T. L. (2013). The pathways of mitophagy for quality control and clearance of mitochondria. Cell Death Differ. 20, 31–42. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2012.81

Avalos, J. L., Bever, K. M., and Wolberger, C. (2005). Mechanism of sirtuin inhibition by nicotinamide: altering the NAD(+) cosubstrate specificity of a Sir2 enzyme. Mol. Cell 17, 855–868. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.02.022

Azzu, V., Affourtit, C., Breen, E. P., Parker, N., and Brand, M. D. (2008). Dynamic regulation of uncoupling protein 2 content in INS-1E insulinoma cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1777, 1378–1383. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2008.07.001

Azzu, V., and Brand, M. D. (2010). Degradation of an intramitochondrial protein by the cytosolic proteasome. J. Cell Sci. 123, 578–585. doi: 10.1242/jcs.060004

Banerjee, S., Zmijewski, J. W., Lorne, E., Liu, G., Sha, Y., and Abraham, E. (2010). Modulation of SCF beta-TrCP-dependent I kappaB alpha ubiquitination by hydrogen peroxide. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 2665–2675. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.060822

Barnham, K. J., Masters, C. L., and Bush, A. I. (2004). Neurodegenerative diseases and oxidative stress. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 3, 205–214. doi: 10.1038/nrd1330

Behl, C., Davis, J. B., Lesley, R., and Schubert, D. (1994). Hydrogen peroxide mediates amyloid beta protein toxicity. Cell 77, 817–827. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90131-7

Bienert, G. P., Moller, A. L., Kristiansen, K. A., Schulz, A., Moller, I. M., Schjoerring, J. K., et al. (2007). Specific aquaporins facilitate the diffusion of hydrogen peroxide across membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 1183–1192. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603761200

Birben, E., Sahiner, U. M., Sackesen, C., Erzurum, S., and Kalayci, O. (2012). Oxidative stress and antioxidant defense. World Allergy Organ. J. 5, 9–19. doi: 10.1097/WOX.0b013e3182439613

Borra, M. T., Smith, B. C., and Denu, J. M. (2005). Mechanism of human SIRT1 activation by resveratrol. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 17187–17195. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501250200

Bragoszewski, P., Gornicka, A., Sztolsztener, M. E., and Chacinska, A. (2013). The ubiquitin-proteasome system regulates mitochondrial intermembrane space proteins. Mol. Cell. Biol. 33, 2136–2148. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01579-12

Breusing, N., and Grune, T. (2008). Regulation of proteasome-mediated protein degradation during oxidative stress and aging. Biol. Chem. 389, 203–209. doi: 10.1515/BC.2008.029

Bulteau, A. L., Petropoulos, I., and Friguet, B. (2000). Age-related alterations of proteasome structure and function in aging epidermis. Exp. Gerontol. 35, 767–777. doi: 10.1016/S0531-5565(00)00136-4

Caito, S., Rajendrasozhan, S., Cook, S., Chung, S., Yao, H., Friedman, A. E., et al. (2010). SIRT1 is a redox-sensitive deacetylase that is post-translationally modified by oxidants and carbonyl stress. FASEB J. 24, 3145–3159. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-151308

Calnan, D. R., and Brunet, A. (2008). The FoxO code. Oncogene 27, 2276–2288. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.21

Cao, J., Hou, J., Ping, J., and Cai, D. (2018). Advances in developing novel therapeutic strategies for Alzheimer's disease. Mol. Neurodegener. 13:64. doi: 10.1186/s13024-018-0299-8

Carrard, G., Bulteau, A. L., Petropoulos, I., and Friguet, B. (2002). Impairment of proteasome structure and function in aging. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 34, 1461–1474. doi: 10.1016/S1357-2725(02)00085-7

Chambers, J. W., and Lograsso, P. V. (2011). Mitochondrial c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) signaling initiates physiological changes resulting in amplification of reactive oxygen species generation. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 16052–16062. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.223602

Chen, S. H., Lin, J. K., Liu, S. H., Liang, Y. C., and Lin-Shiau, S. Y. (2008). Apoptosis of cultured astrocytes induced by the copper and neocuproine complex through oxidative stress and JNK activation. Toxicol. Sci. 102, 138–149. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfm292

Circu, M. L., and Aw, T. Y. (2010). Reactive oxygen species, cellular redox systems, and apoptosis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 48, 749–762. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.12.022

Circu, M. L., Moyer, M. P., Harrison, L., and Aw, T. Y. (2009). Contribution of glutathione status to oxidant-induced mitochondrial DNA damage in colonic epithelial cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 47, 1190–1198. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.07.032

Conde De La Rosa, L., Vrenken, T. E., Hannivoort, R. A., Buist-Homan, M., Havinga, R., Slebos, D. J., et al. (2008). Carbon monoxide blocks oxidative stress-induced hepatocyte apoptosis via inhibition of the p54 JNK isoform. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 44, 1323–1333. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.12.011

Cui, M., Huang, Y., Zhao, Y., and Zheng, J. (2009). New insights for FOXO and cell-fate decision in HIV infection and HIV associated neurocognitive disorder. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 665, 143–159. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-1599-3_11

Davies, K. J. (2001). Degradation of oxidized proteins by the 20S proteasome. Biochimie 83, 301–310. doi: 10.1016/S0300-9084(01)01250-0

Devasagayam, T. P., Tilak, J. C., Boloor, K. K., Sane, K. S., Ghaskadbi, S. S., and Lele, R. D. (2004). Free radicals and antioxidants in human health: current status and future prospects. J. Assoc. Physicians India 52, 794–804. Available online at: http://www.japi.org/october2004/R-794.pdf

Fariss, M. W., Chan, C. B., Patel, M., Van Houten, B., and Orrenius, S. (2005). Role of mitochondria in toxic oxidative stress. Mol. Interv. 5, 94–111. doi: 10.1124/mi.5.2.7

Gibson, B. W. (2005). The human mitochondrial proteome: oxidative stress, protein modifications and oxidative phosphorylation. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 37, 927–934. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.11.013

Guernsey, D. L., Jiang, H., Campagna, D. R., Evans, S. C., Ferguson, M., Kellogg, M. D., et al. (2009). Mutations in mitochondrial carrier family gene SLC25A38 cause nonsyndromic autosomal recessive congenital sideroblastic anemia. Nat. Genet. 41, 651–653. doi: 10.1038/ng.359

Hariharan, N., Maejima, Y., Nakae, J., Paik, J., Depinho, R. A., and Sadoshima, J. (2010). Deacetylation of FoxO by Sirt1 plays an essential role in mediating starvation-induced autophagy in cardiac myocytes. Circ. Res. 107, 1470–1482. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.227371

Hreniuk, D., Garay, M., Gaarde, W., Monia, B. P., Mckay, R. A., and Cioffi, C. L. (2001). Inhibition of c-Jun N-terminal kinase 1, but not c-Jun N-terminal kinase 2, suppresses apoptosis induced by ischemia/reoxygenation in rat cardiac myocytes. Mol. Pharmacol. 59, 867–874. doi: 10.1124/mol.59.4.867

Huang, H., Regan, K. M., Wang, F., Wang, D., Smith, D. I., Van Deursen, J. M., et al. (2005). Skp2 inhibits FOXO1 in tumor suppression through ubiquitin-mediated degradation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 102, 1649–1654. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406789102

Jain, V., Langham, M. C., and Wehrli, F. W. (2010). MRI estimation of global brain oxygen consumption rate. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 30, 1598–1607. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.49

Jung, T., and Grune, T. (2008). The proteasome and its role in the degradation of oxidized proteins. IUBMB Life 60, 743–752. doi: 10.1002/iub.114

Kanayama, A., and Miyamoto, Y. (2007). Apoptosis triggered by phagocytosis-related oxidative stress through FLIPS down-regulation and JNK activation. J. Leukoc. Biol. 82, 1344–1352. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0407259

Kannengiesser, C., Sanchez, M., Sweeney, M., Hetet, G., Kerr, B., Moran, E., et al. (2011). Missense SLC25A38 variations play an important role in autosomal recessive inherited sideroblastic anemia. Haematologica 96, 808–813. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2010.039164

Karbowski, M., and Youle, R. J. (2011). Regulating mitochondrial outer membrane proteins by ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 23, 476–482. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2011.05.007

Karpac, J., and Jasper, H. (2009). Insulin and JNK: optimizing metabolic homeostasis and lifespan. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 20, 100–106. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2008.11.004

Ling, J., and Soll, D. (2010). Severe oxidative stress induces protein mistranslation through impairment of an aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase editing site. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 107, 4028–4033. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000315107

Ma, M. W., Wang, J., Zhang, Q., Wang, R., Dhandapani, K. M., Vadlamudi, R. K., et al. (2017). NADPH oxidase in brain injury and neurodegenerative disorders. Mol. Neurodegener. 12, 7. doi: 10.1186/s13024-017-0150-7

Martindale, J. L., and Holbrook, N. J. (2002). Cellular response to oxidative stress: signaling for suicide and survival. J. Cell. Physiol. 192, 1–15. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10119

Messina, S., Frati, L., and Porcellini, A. (2012). Oxidative stress posttranslationally regulates the expression of Ha-Ras and Ki-Ras in cultured astrocytes. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2012:792705. doi: 10.1155/2012/792705

Murakami, Y., Matsufuji, S., Kameji, T., Hayashi, S., Igarashi, K., Tamura, T., et al. (1992). Ornithine decarboxylase is degraded by the 26S proteasome without ubiquitination. Nature 360, 597–599. doi: 10.1038/360597a0

Parfenova, H., Basuroy, S., Bhattacharya, S., Tcheranova, D., Qu, Y., Regan, R. F., et al. (2006). Glutamate induces oxidative stress and apoptosis in cerebral vascular endothelial cells: contributions of HO-1 and HO-2 to cytoprotection. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 290, C1399–1410. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00386.2005

Patel, J., Mcleod, L. E., Vries, R. G., Flynn, A., Wang, X., and Proud, C. G. (2002). Cellular stresses profoundly inhibit protein synthesis and modulate the states of phosphorylation of multiple translation factors. Eur. J. Biochem. 269, 3076–3085. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.02992.x

Rachek, L. I., Yuzefovych, L. V., Ledoux, S. P., Julie, N. L., and Wilson, G. L. (2009). Troglitazone, but not rosiglitazone, damages mitochondrial DNA and induces mitochondrial dysfunction and cell death in human hepatocytes. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 240, 348–354. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2009.07.021

Sauer, H., Wartenberg, M., and Hescheler, J. (2001). Reactive oxygen species as intracellular messengers during cell growth and differentiation. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 11, 173–186. doi: 10.1159/000047804

Shenton, D., Smirnova, J. B., Selley, J. N., Carroll, K., Hubbard, S. J., Pavitt, G. D., et al. (2006). Global translational responses to oxidative stress impact upon multiple levels of protein synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 29011–29021. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601545200

Sinha, K., Das, J., Pal, P. B., and Sil, P. C. (2013). Oxidative stress: the mitochondria-dependent and mitochondria-independent pathways of apoptosis. Arch. Toxicol. 87, 1157–1180. doi: 10.1007/s00204-013-1034-4

Suzuki, Y. J., Forman, H. J., and Sevanian, A. (1997). Oxidants as stimulators of signal transduction. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 22, 269–285. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(96)00275-4

Valko, M., Morris, H., and Cronin, M. T. (2005). Metals, toxicity and oxidative stress. Curr. Med. Chem. 12, 1161–1208. doi: 10.2174/0929867053764635

Van Der Horst, A., and Burgering, B. M. (2007). Stressing the role of FoxO proteins in lifespan and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 440–450. doi: 10.1038/nrm2190

Wang, X., Yen, J., Kaiser, P., and Huang, L. (2010). Regulation of the 26S proteasome complex during oxidative stress. Sci Signal 3:ra88. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2001232

Yang, Y., Zhao, Y., Liao, W., Yang, J., Wu, L., Zheng, Z., et al. (2009). Acetylation of FoxO1 activates Bim expression to induce apoptosis in response to histone deacetylase inhibitor depsipeptide treatment. Neoplasia 11, 313–324. doi: 10.1593/neo.81358

Yin, Z., Ivanov, V. N., Habelhah, H., Tew, K., and Ronai, Z. (2000). Glutathione S-transferase p elicits protection against H2O2-induced cell death via coordinated regulation of stress kinases. Cancer Res. 60, 4053–4057. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-035-5_12

Yoshii, S. R., Kishi, C., Ishihara, N., and Mizushima, N. (2011). Parkin mediates proteasome-dependent protein degradation and rupture of the outer mitochondrial membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 19630–19640. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.209338

Zhang, C., Shi, Z., Zhang, L., Zhou, Z., Zheng, X., Liu, G., et al. (2016). Appoptosin interacts with mitochondrial outer-membrane fusion proteins and regulates mitochondrial morphology. J. Cell Sci. 129, 994–1002. doi: 10.1242/jcs.176792

Zhang, H., Zhang, Y. W., Chen, Y., Huang, X., Zhou, F., Wang, W., et al. (2012). Appoptosin is a novel pro-apoptotic protein and mediates cell death in neurodegeneration. J. Neurosci. 32, 15565–15576. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3668-12.2012

Zhao, Y., Tseng, I. C., Heyser, C. J., Rockenstein, E., Mante, M., Adame, A., et al. (2015). Appoptosin-mediated caspase cleavage of Tau contributes to progressive supranuclear palsy pathogenesis. Neuron 87, 963–975. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.08.020

Keywords: appoptosin, oxidative stress, ROS, JNK, FoxO1

Citation: Zhang C, Tan Z, Xie Y, Zhao Y, Huang TY, Lu Z, Luo H, Can D, Xu H, Zhang Y-w and Zhang X (2019) Appoptosin Mediates Lesions Induced by Oxidative Stress Through the JNK-FoxO1 Pathway. Front. Aging Neurosci. 11:243. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2019.00243

Received: 21 May 2019; Accepted: 20 August 2019;

Published: 04 September 2019.

Edited by:

Xiongwei Zhu, Case Western Reserve University, United StatesReviewed by:

Riqiang Yan, University of Connecticut, United StatesPeng Lei, State Key Laboratory of Biotherapy, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, China

Copyright © 2019 Zhang, Tan, Xie, Zhao, Huang, Lu, Luo, Can, Xu, Zhang and Zhang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yun-wu Zhang, eXVuemhhbmcmI3gwMDA0MDt4bXUuZWR1LmNu; Xian Zhang, eGlhbnpoYW5nJiN4MDAwNDA7eG11LmVkdS5jbg==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Cuilin Zhang1,2†

Cuilin Zhang1,2† Zhenqiu Tan

Zhenqiu Tan Yongzhuang Xie

Yongzhuang Xie Yun-wu Zhang

Yun-wu Zhang Xian Zhang

Xian Zhang