95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Aging Neurosci. , 20 November 2014

Sec. Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Brain-aging

Volume 6 - 2014 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2014.00324

This article is part of the Research Topic Pathophysiological Mechanisms of Sarcopenia in Aging and in Muscular Dystrophy: a Translational Approach View all 28 articles

Alessandra Zulian1,2

Alessandra Zulian1,2 Francesca Tagliavini3,4

Francesca Tagliavini3,4 Erika Rizzo1,2

Erika Rizzo1,2 Camilla Pellegrini4

Camilla Pellegrini4 Francesca Sardone3,4

Francesca Sardone3,4 Nicoletta Zini3,4

Nicoletta Zini3,4 Nadir Mario Maraldi3

Nadir Mario Maraldi3 Spartaco Santi3,4

Spartaco Santi3,4 Cesare Faldini5

Cesare Faldini5 Luciano Merlini4

Luciano Merlini4 Valeria Petronilli1,2

Valeria Petronilli1,2 Paolo Bernardi1,2*

Paolo Bernardi1,2* Patrizia Sabatelli3,4*

Patrizia Sabatelli3,4*Ullrich congenital muscular dystrophy and Bethlem myopathy are caused by mutations in collagen VI (ColVI) genes, which encode an extracellular matrix protein; yet, mitochondria play a major role in disease pathogenesis through a short circuit caused by inappropriate opening of the permeability transition pore, a high-conductance channel, which causes a shortage in ATP production. We find that melanocytes do not produce ColVI yet they bind it at the cell surface, suggesting that this protein may play a trophic role and that its absence may cause lesions similar to those seen in skeletal muscle. We show that mitochondria in melanocytes of Ullrich congenital muscular dystrophy and Bethlem myopathy patients display increased size, reduced matrix density, and disrupted cristae, findings that suggest a functional impairment. In keeping with this hypothesis, mitochondria (i) underwent anomalous depolarization after inhibition of the F-ATP synthase with oligomycin, and (ii) displayed decreased respiratory reserve capacity. The non-immunosuppressive cyclophilin inhibitor NIM811 prevented mitochondrial depolarization in response to oligomycin in melanocytes from both Ullrich congenital muscular dystrophy and Bethlem myopathy patients, and partially restored the respiratory reserve of melanocytes from one Bethlem myopathy patient. These results match our recent findings on melanocytes from patients affected by Duchenne muscular dystrophy (Pellegrini et al., 2013), and suggest that skin biopsies may represent a minimally invasive tool to investigate mitochondrial dysfunction and to evaluate drug efficacy in ColVI-related myopathies and possibly in other muscle wasting conditions like aging sarcopenia.

Collagen VI (ColVI) is an extracellular matrix (ECM) protein that forms a complex microfibrillar network; it is present in several organs including skeletal muscle, where it is localized just outside the basement membrane (Kuo et al., 1997). ColVI is constituted by three chains (α1, α2, and α3) encoded by different genes (COL6A1, COL6A2, and COL6A3, respectively). Three additional ColVI chains have recently been identified (α4, α5, α6), which are similar to α3 but display a more restricted tissue distribution (Gara et al., 2008). Deficiency of ColVI due to mutations in COL6A1, COL6A2, or COL6A3 gives rise to three main muscle disorders, Ullrich congenital muscular dystrophy (UCMD, MIM #254090) (Ullrich, 1930; Camacho Vanegas et al., 2001), Bethlem myopathy (BM, MIM #158810) (Bethlem and Wijngaarden, 1976), and myosclerosis myopathy (MIM #255600) (Merlini et al., 2008b). UCMD is a severe disorder characterized by congenital muscle weakness with axial and proximal joint contractures and coexisting distal joint hypermobility (Bertini and Pepe, 2002). BM is characterized by slowly progressive axial and proximal muscle weakness with finger flexion contractures (Merlini et al., 1994). Myosclerosis myopathy is a recessive disorder characterized by progressive contractures affecting all joints (Merlini et al., 2008b). However, it should be noted that the clinical features of ColVI muscular dystrophy can be extremely heterogenous, ranging from mild to severe myopathy with progressive muscular dystrophy (Jöbsis et al., 1999). Consistent with the idea that these disorders represent a clinical continuum, about 70 different mutations of the COL6 genes have so far been described in ColVI myopathies (Pepe et al., 2002; Lampe and Bushby, 2005). Patients affected by ColVI muscular dystrophies frequently display skin alterations. Patients with the UCMD phenotype usually present follicular hyperkeratosis over the extensor surfaces of upper and lower limbs, soft velvety skin on the palms and soles, and tendency to develop keloids or “cigarette paper” scars, skin features that may be present also in BM patients (Lampe and Bushby, 2005). Although the mechanism linking ColVI deficiency to skin lesions has not been established, it has recently been shown that melanocytes affect fibroblast proliferation and collagen production, contributing to the generation of hypertrophic scars and keloids (Gao et al., 2013).

Collagen VI myopathies share a common pathogenesis linked to deregulation of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (PTP), an inner membrane high-conductance channel that forms from dimers of the mitochondrial F-ATP synthase under conditions of Ca2+ overload and oxidative stress (Bernardi, 2013; Giorgio et al., 2013) and is desensitized by cyclosporin (Cs) A. Oxidative stress is specifically involved in the pathogenesis of myopathy in the Col6a1−/− mouse model (Menazza et al., 2010; Sorato et al., 2014); and the resulting myofiber damage is amplified by impaired clearance of defective mitochondria (Grumati et al., 2010). PTP-dependent mitochondrial dysfunction appears to be involved also in other forms of muscular dystrophy, including those caused by lack of δ-sarcoglycan and laminin-2 (Millay et al., 2008), as well as of dystrophin (Millay et al., 2008; Reutenauer et al., 2008; Wissing et al., 2010; Pellegrini et al., 2013). These studies generated pharmacological strategies aimed at rescuing the mitochondrial defect through desensitization of the PTP, and encouraging results have been obtained with the use of CsA and its non-immunosuppressive analogs Debio025 and NIM811 in animal models and in a pilot trial in patients (Irwin et al., 2003; Angelin et al., 2007; Merlini et al., 2008a; Tiepolo et al., 2009; Telfer et al., 2010; Zulian et al., 2014).

Translation of the pharmacological strategies tested in animal models to muscular dystrophy patients is particularly complex, and often requires invasive procedures. Cell cultures derived from muscle biopsies can be used for genetic and mechanistic studies, but in the case of ColVI myopathies the disease phenotype is lost after a few passages, a likely result of in vitro selection of apoptosis-resistant cells (Sabatelli et al., 2012b). Melanocytes are the pigment-producing cells of the skin, localized to the basal layer of human epidermis. They are polarized cells performing specific functions at the basolateral and apical membranes, which explains the differential composition of the membrane at these sites (Pinon and Wehrle-Haller, 2011). At the basal layer, melanocytes attach to the dermal–epidermal junction (DEJ), a specialized structure with a fundamental role in maintaining attachment of the epidermis to the dermis and providing skin resistance against shearing forces (Santiago-Walker et al., 2009). Melanocytes do express muscle-specific proteins including the mDP427 dystrophin isoform at the interface with the DEJ (Pellegrini et al., 2013). We have recently demonstrated that melanocytes possess properties similar to those of myoblasts from Duchenne muscular dystrophy patients, and represent a promising cellular model to monitor the response of dystrophinopathies to pharmacological treatments (Pellegrini et al., 2013). Here, we have explored whether mitochondrial dysfunction can be detected in melanocytes from UCMD and BM patients, and whether these cells are a potential alternative to the use of muscle-derived cells in the study and therapy of ColVI myopathies.

Skin biopsies from two healthy subjects and four ColVI muscular dystrophy patients (two UCMD and two BM) were collected. All patients were previously diagnosed by genetic, and/or histochemical and biochemical analysis. UCMD patient 1 (UCMD1) carried a COL6A2 homozygous mutation in exon 28 [UCMD-5 patient in Tagliavini et al. (2014)]; UCMD patient 2 (UCMD2) displayed typical UCMD features, severe deficiency of ColVI in muscle biopsies and defective ColVI secretion in cultured skin fibroblasts; BM patients 1 (BM1) and 2 (BM2) carried heterozygous mutations in COL6A1 and COL6A3, respectively [patients BM-5 and BM-6, respectively, in Tagliavini et al. (2014)]. All participants provided written informed consent, and approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Rizzoli Orthopaedic Institute (Bologna, Italy).

Skin fragments were cut into small pieces and the epidermis was separated from the dermis after overnight incubation in 0.5% dispase II (Roche) at 4°C. Melanocytes were maintained in M254 culture medium (GIBCO) supplemented with phorbol-12-myristate 13-acetate, transferrin, hydrocortisone, insulin, bovine pituitary extract, basic fibroblast growth factor, and fetal calf serum (HMGS supplement, GIBCO). Melanocyte-fibroblast co-cultures were obtained by plating fibroblasts onto coverslips in DMEM growth medium until they reached 70% confluence; after 1 day melanocytes were seeded onto the fibroblast cultures and grown in M254 medium supplemented with 0.25 mM l-ascorbic acid (Sigma). ColVI-enriched, conditioned medium was obtained by treating confluent skin fibroblast cultures from healthy donors with DMEM medium supplemented with 0.25 mM l-ascorbic acid. After 24 h, the medium was collected, centrifuged at low speed to remove cell debris and diluted 1:1 with M254 medium. Normal melanocytes plated onto coverslips were grown with ColVI-enriched medium for 24 h before immunohistochemical analysis with anti-ColVI antibody (Millipore). To assess the effect of cyclophilin inhibitors on mitochondrial morphology, melanocytes from patients and healthy subjects were treated with 0.8 μM NIM811 diluted in M254 medium for 2 h at 37°C before processing for immunofluorescence and transmission electron microscopy.

Cultured melanocytes were fixed with methanol at −20°C for 7 min, washed with phosphate-buffered saline, and incubated with antibodies against NG2 (Millipore), integrin β1 (Millipore), pMEL-17 (Monosan), ColVI (Millipore), or Tom20 (Santa Cruz). All antibodies were revealed with secondary anti-rabbit or anti-mouse TRITC or FITC-conjugated antibodies (DAKO). Samples were mounted with an anti-fading reagent (Molecular Probes) and analyzed with a A1-R confocal laser microscope (Nikon) equipped with a Nikon Plan Apo TIRF 100×, 1.45 NA objective, and with 405 and 561 nm laser lines to elicit DAPI (blue) and TRITC (red) fluorescence signals. Z-stacks were collected at optical resolution of 120 nm/pixel with pinhole diameter set to 1 Airy unit and z-step size to 150 nm. All image analyses were performed using NIS-Elements software (Nikon). For mitochondrial morphometric analysis, maximum intensity projections were generated. Analysis was limited to regions of interest at the periphery of cells, where individual mitochondria are readily resolved. Images were thresholded and converted to binary images. Image segmentation was performed on the binary mask, and number and length of discrete features was measured. The statistical significance of the differences between the experimental points was evaluated by Student’s t-test.

Skin biopsy fragments and melanocytes grown onto uncoated well plates were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer for 2 h and post-fixed with 1% osmium tetroxide. After dehydration, samples were detached with propylene oxide, embedded in Epon812 epoxy resin, and observed with a Philips EM400 electron microscope operated at 100 kV after cutting ultrathin sections. For rotary shadowing electron microscopy analysis, melanocyte-fibroblast co-cultures were incubated with anti-ColVI antibody diluted 1:25 in culture medium at 37°C for 2 h. After several washes with culture medium, samples were incubated with anti-mouse IgG 5 nm gold-conjugated antibody diluted 1:20 in culture medium for 1 h at 37°C. Negative controls were performed in the absence of primary antibody. After immunolabeling cells were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer and 1% osmium tetroxide, dehydrated in ethanol and critical point-dried. Thereafter, the slides were rotary-shadowed with platinum at 45°C and coated with carbon at 90°C in a Balzers BAF 400D Freeze Fracture as previously described (Zhang et al., 2002).

Mitochondrial membrane potential was measured based on the accumulation of tetramethylrhodamine methyl ester (TMRM, Molecular Probes) (Angelin et al., 2007). Primary cultures of melanocytes obtained as described above from healthy donors, UCMD, and BM patients were seeded onto 24-mm-diameter round glass coverslips and grown for 2 days in M254 culture medium with HMGS supplement (GIBCO). The medium was then replaced with serum-free M254 medium supplemented with 10 nM TMRM for 30 min, and cellular fluorescence images were acquired with an Olympus IX71/IX51 inverted microscope, equipped with a xenon light source (75 W) for epifluorescence illumination and with a 12-bit digital cooled CCD camera (Micromax, Princeton Instruments). Data were acquired and analyzed using Cell R Software (Olympus). For detection of fluorescence, 568 ± 25 nm band-pass excitation and 585 nm long-pass emission filter settings were used. Images were collected with exposure time of 100 ms using a 40×, 1.3 NA oil immersion objective (Nikon). The extent of cell and hence mitochondrial loading with potentiometric probes is affected by the activity of the plasma membrane multidrug resistance pump. In order to normalize the loading conditions, in all experiments with TMRM the medium was supplemented with 1.6 μM CsH, which inhibits the multidrug resistance pump but not the PTP (Bernardi et al., 1999). At the end of each experiment, mitochondria were fully depolarized by the addition of 4 μM of the protonophore carbonyl cyanide-p-trifluoromethoxyphenyl hydrazone (FCCP). Clusters of several mitochondria were identified as regions of interest, and fields not containing cells were taken as background. Sequential digital images were acquired every 5 min and the average fluorescence intensity of all relevant regions was recorded and stored for subsequent analysis.

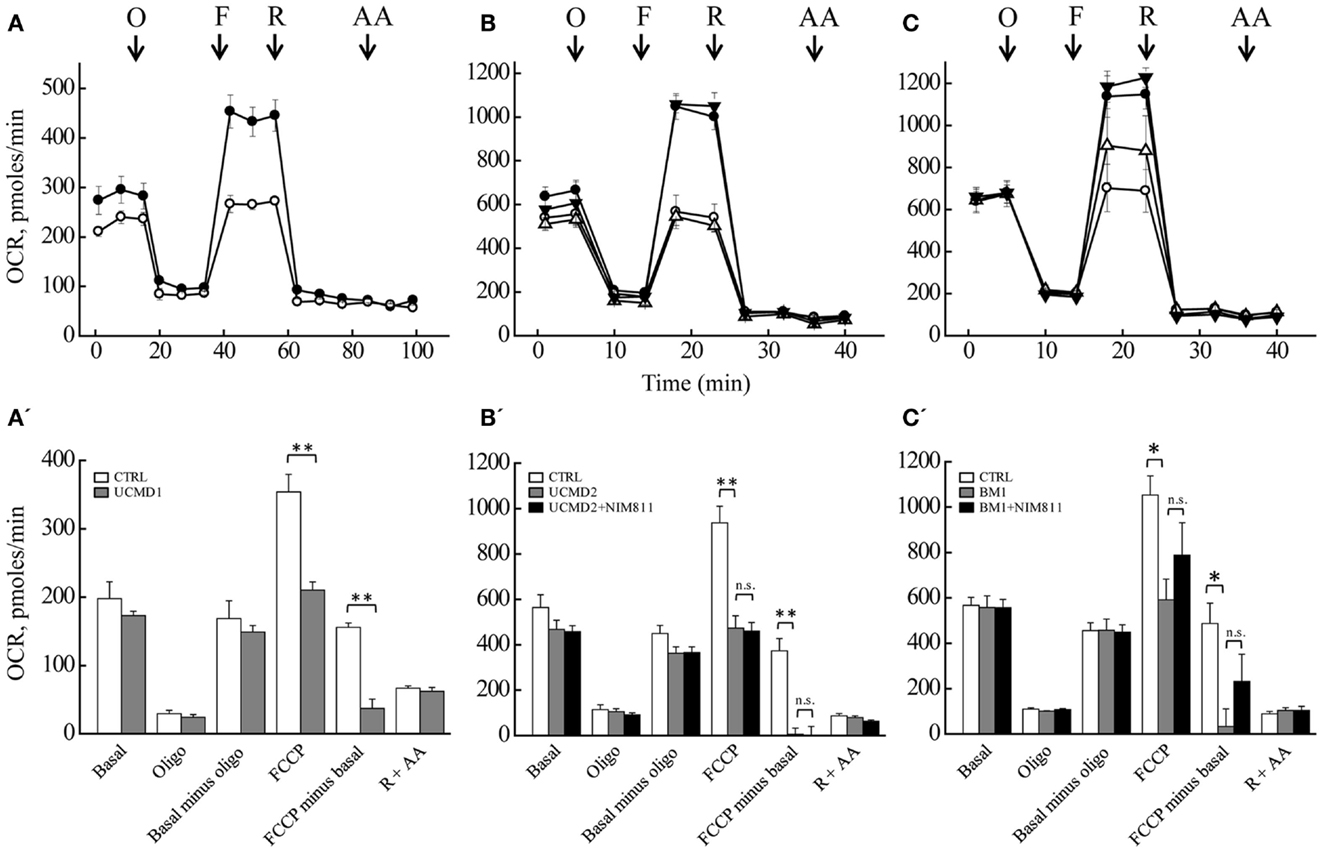

Oxygen consumption rate (OCR) was measured with the XF24 Extracellular Flux Analyzer (Seahorse Bioscience, Billerica, MA, USA). Melanocytes were seeded in XF24 cell culture microplates at 6 × 104 cells/well for patient UCMD1 and 13 × 104 cells/well for patients UCMD2 and BM1 (the same cell densities were used for the matched cultures from healthy donors) in 0.2 ml of M254 culture medium with HMGS supplement and incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 24 h. Experiments were carried out on confluent monolayers. Assay were initiated by replacing the growth medium in each well with 0.67 ml of serum-free M254 prewarmed at 37°C. Cells were incubated at 37°C for 30 min to allow temperature and pH equilibration. A titration with FCCP was performed for each cell type in order to determine the optimal FCCP concentration (i.e., the concentration that stimulates respiration maximally), which was found to be 1 μM for cells from healthy donors, 0.8 μM for patient UCMD1, 0.4–0.6 μM for patient UCMD2, and 0.4 μM for patient BM1. After an OCR baseline was established, 70 μl of a solution containing oligomycin, FCCP, rotenone, or antimycin A were sequentially added to each well to reach final concentrations of 1 μg/ml oligomycin, FCCP as stated above, and 1 μM for rotenone and antimycin A. Data are expressed as pmol of O2 per minute per 6 × 104 (UCMD1) or 13 × 104 (UCMD2, BM1) cells. At the end of each experiment, the medium was removed from each well and the total protein content per well was quantified. Cells were lysed at 4°C in a buffer composed of 140 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 5 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100 (0.1 ml/well) in the presence of phosphatase and protease inhibitors (Sigma). Lysates were then cleared by centrifugation at 13,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C, and proteins were quantified using a BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific-Pierce).

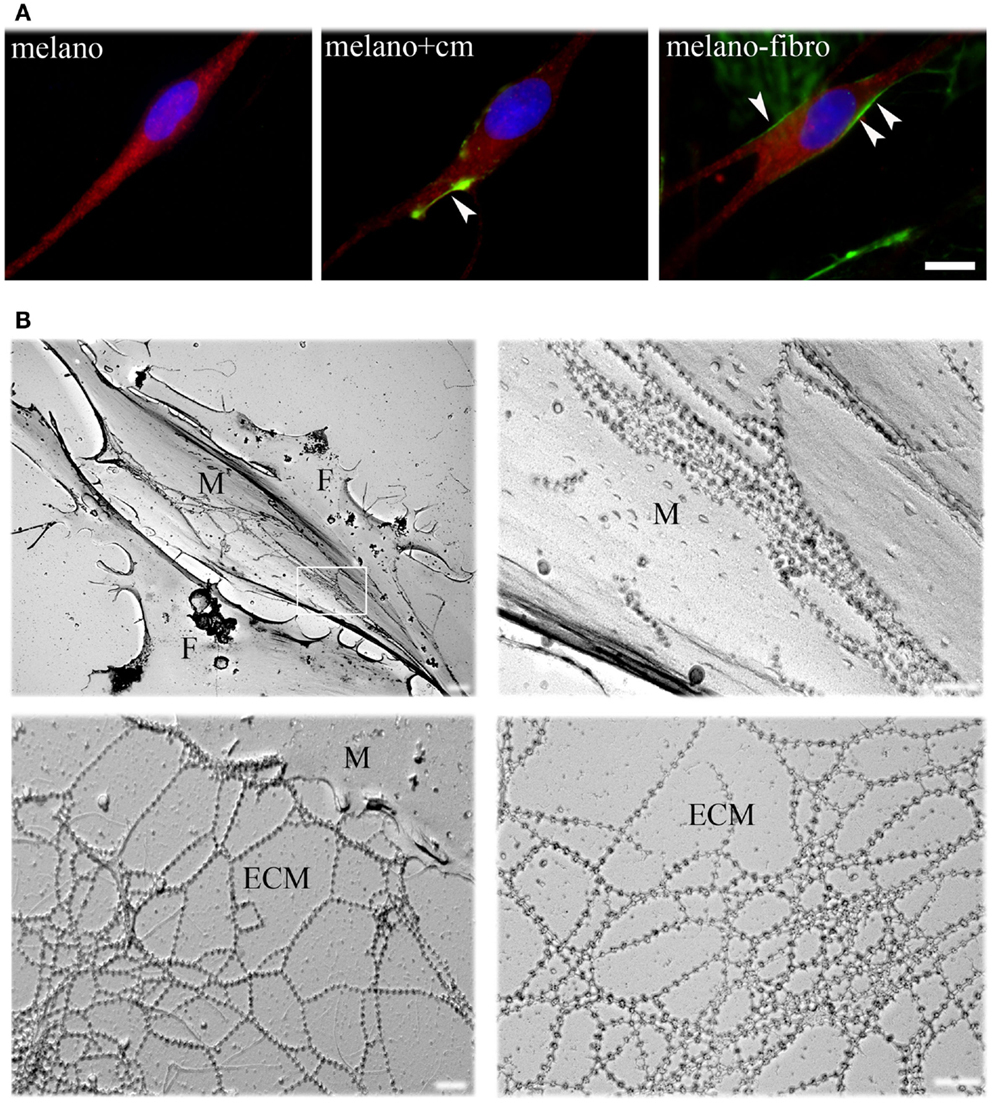

To define their interactions with ColVI, we studied pure cultures of melanocytes from healthy donors in the presence of ascorbic acid, which allows hydroxylation of proline and lysine residues and secretion of ColVI in vitro (Colombatti and Bonaldo, 1987). ColVI could not be detected in the ECM or inside the cells (Figure 1A, left panel), indicating that melanocytes do not synthesize and secrete this protein. However, when melanocytes were treated with a ColVI-enriched medium obtained from skin fibroblasts (Figure 1A, middle panel) or co-cultured with ColVI-producing skin fibroblasts (Figure 1A, right panel) a clear association of ColVI with the cell surface was detected. Rotary shadowing immunoelectron microscopic analysis with anti-ColVI antibody confirmed the presence of ColVI microfilaments onto the cell membrane of melanocytes (M), which can easily be distinguished from fibroblasts (F) because of their elongated, bipolar shape (Figure 1B, upper left panel). Microfilaments displayed the typical “beaded” pattern with a periodicity of 100 nm, and formed parallel rows when attached to the melanocyte cell surface (Figure 1B, upper right panel), while they formed web-like structures when deposited in the ECM (Figure 1B, lower panels).

Figure 1. Immunofluorescence analysis and EM rotary shadowing of melanocyte cultures. (A) Double labeling for ColVI (green) and p-MEL17 (red) on melanocyte cultures under basal conditions (melano), after treatment with ColVI-enriched medium conditioned by skin fibroblasts (melano + cm), and of melanocytes co-cultured with skin fibroblasts (melano + fibro); scale bar, 10 μm. (B) Rotary shadowing electron microscopy analysis of melanocytes co-cultured with fibroblasts. Melanocytes (M, upper left panel) display the typical bipolar shape compared to the flat morphology of fibroblasts (F). Typical ColVI “beaded” microfilaments, identified by 5 nm colloidal gold particles, are visible both at the melanocytes cell surface (top right panel) and in the ECM (bottom panels). Microfilaments formed parallel rows when attached to the cell surface (upper right panel, which is a magnification of the boxed area in the upper left panel), and web-like structures when deposited in the ECM (lower panels). Scale bar, 400 nm.

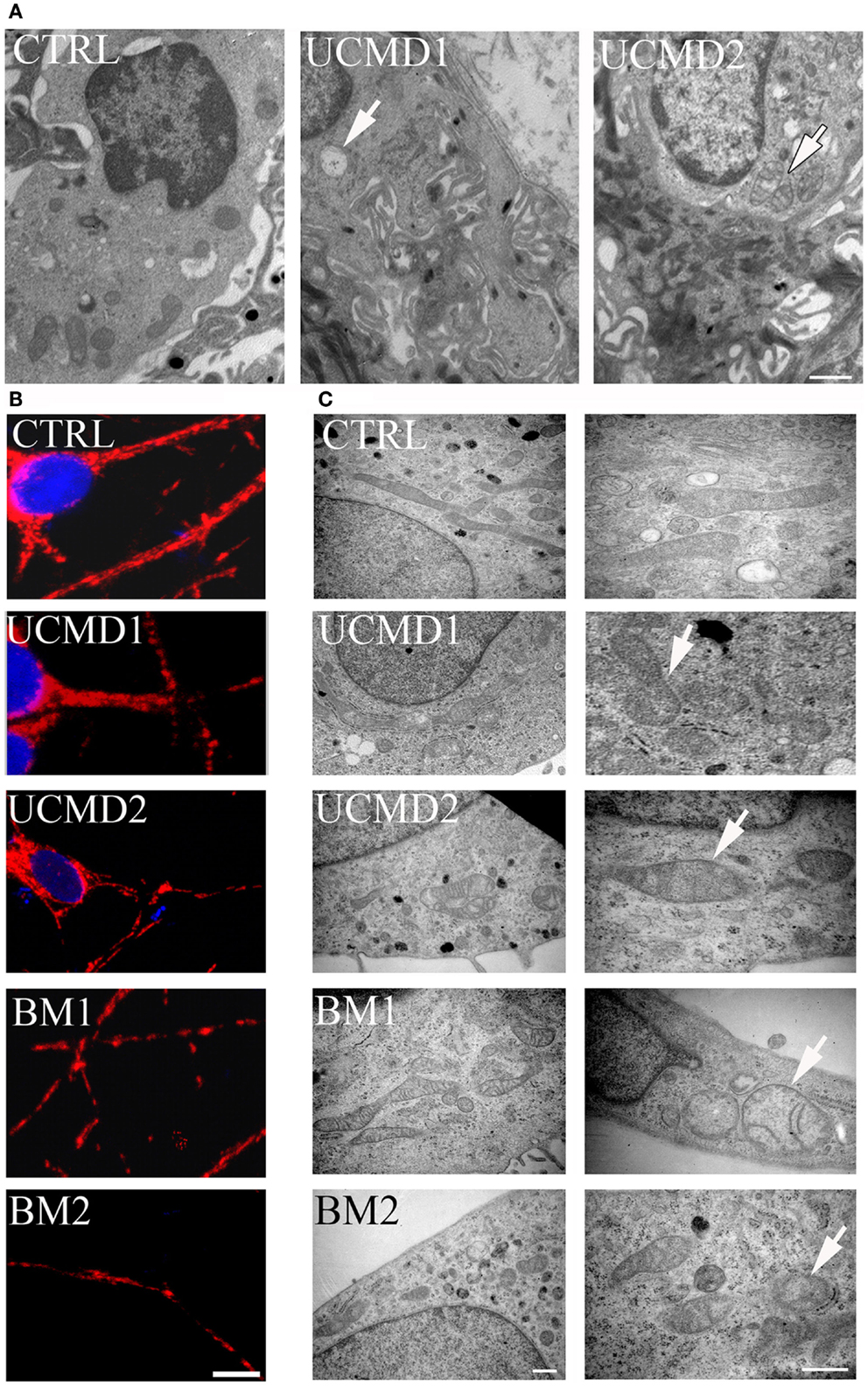

Skin biopsies of healthy donors and of UCMD patients were studied by ultrastructural analysis. Mitochondrial changes, including increased size, reduced matrix density, and disrupted cristae consistent with swelling, were frequently found in patients (Figure 2A, arrows in middle and right panels), while mitochondria in melanocytes of healthy controls had the expected features (Figure 2A, left panel). Occurrence of mitochondrial alterations was also detected in melanocyte cultures obtained from both UCMD and BM patients. The mitochondrial reticulum, as monitored by immunofluorescence analysis of the outer membrane protein Tom20, appeared fragmented along the cytoplasmic extensions as indicated by the presence of a punctate labeling pattern (Figure 2B). Ultrastructural analysis showed changes similar to those detected in skin, with mitochondria of irregular size and focal swelling (Figure 2C, arrows).

Figure 2. Morphological analysis of skin biopsies and melanocyte cultures. (A) Ultrastructural analysis of melanocytes in epon-embedded skin biopsies from healthy donor (CTRL) and patients UCMD1 and UCMD2 showing altered mitochondria (arrows) in patient melanocytes; scale bar, 1 μm. (B) Confocal imaging of melanocyte cultures from patients UCMD1, UCMD2, BM1, and BM2 and from healthy donor (CTRL) labeled with an anti-Tom20 antibody. Patient melanocytes display a fragmented and discontinuous mitochondrial network compared to the long and branched pattern of the cells from healthy donor; scale bar, 20 μm. (C) Ultrastructural analysis of melanocyte cultures from a healthy donor and patients, showing the presence of enlarged mitochondria with a few cristae (arrows) in all patients; scale bar, 500 nm.

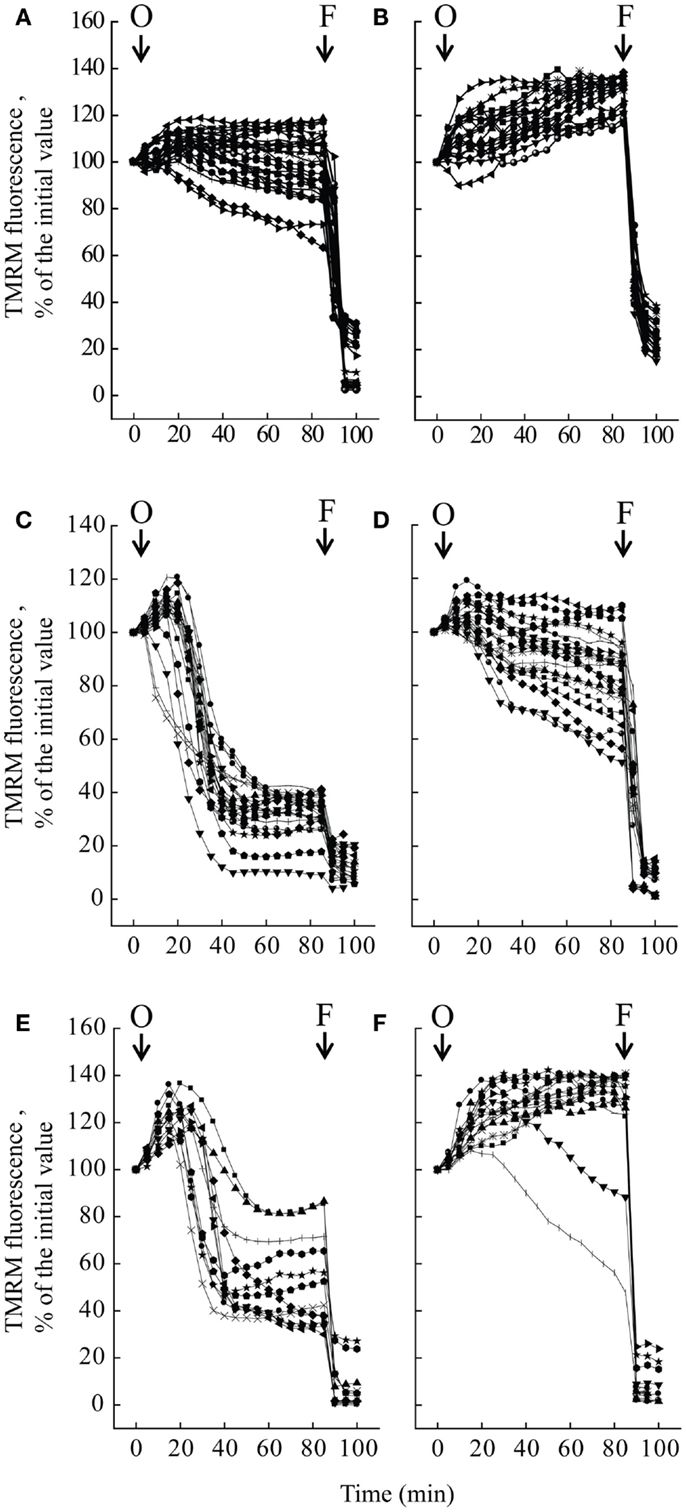

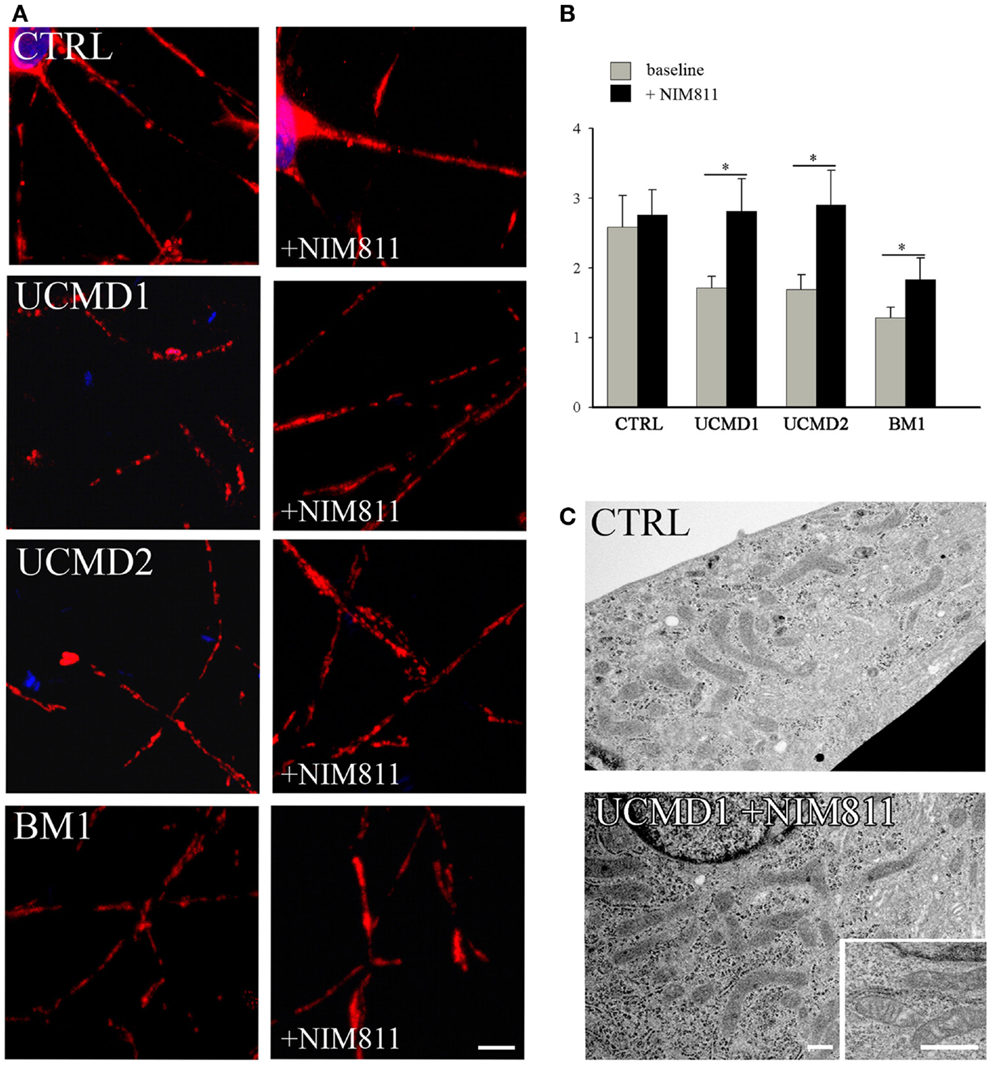

We studied mitochondrial function in primary cultures of melanocytes obtained from one healthy donor and from patients UCMD2 and BM1. Irrespective of the presence of NIM811, addition of oligomycin to melanocytes from healthy donor was followed by an initial fluorescence increase (i.e., the expected hyperpolarization), which was readily followed by depolarization (i.e., probe release with decreased mitochondrial fluorescence) upon addition of the protonophore FCCP (Figures 3A,B). At variance from melanocytes from healthy donor, upon addition of oligomycin melanocytes from patients UCMD2 (Figure 3C) and BM1 (Figure 3E) underwent rapid mitochondrial depolarization after the initial hyperpolarization. Consistent with a key role of the PTP in onset of depolarization, the response to oligomycin was normalized by the cyclophilin inhibitor NIM811, a CsA analog devoid of immunosuppressive activity that desensitizes the PTP without inhibiting calcineurin (Zulian et al., 2014) (Figures 3D,F). Treatment with NIM811 normalized mitochondrial morphology of UCMD1, UCMD2, and BM1, improving the mitochondrial reticulum extension as indicated by increased mitochondrial length (Figures 4A,B). Ultrastructural analysis confirmed that treatment with NIM811 restored mitochondrial matrix density and cristae organization in patient melanocytes (Figure 4C), without affecting mitochondria of melanocytes from the healthy patient (Figures 4B,C). It should be noted that NIM811 inhibits all CyP isoforms, and that an isoform-selective inhibitor is only available for CyPA (Daum et al., 2009); yet, since mitochondria lack other Cs-binding proteins (Nicolli et al., 1996), we conclude that the mitochondrial effects of NIM811 are mediated by inhibition of CyPD. Taken together, these results demonstrate that UCMD and BM melanocytes display the same PTP-dependent latent mitochondrial dysfunction previously identified in primary muscle-derived cell cultures from Col6a1−/− mice (Irwin et al., 2003), UCMD and BM patients (Angelin et al., 2007), and zebrafish with ColVI myopathy (Telfer et al., 2010; Zulian et al., 2014).

Figure 3. Effect of oligomycin on mitochondrial membrane potential in melanocytes. Melanocytes from one healthy donor (A,B), from patient UCMD2 (C,D) and from patient BM1 (E,F) were loaded with TMRM and studied by epifluorescence microscopy as described (Pellegrini et al., 2013). Where indicated (arrows), 6 μM oligomycin (O) and 4 μM FCCP (F) were added. In the experiments of (B,D,F), cells had been treated with 0.8 μM NIM811 for 30 min before beginning the recordings. Each line reports mitochondrial fluorescence of one individual cell.

Figure 4. Effect of NIM811 on mitochondrial morphology. (A) Melanocytes from a healthy donor, and from UCMD1, UCMD2, and BM1 patients were treated with 0.8 μM NIM811 for 2 h and labeled with anti-Tom20 antibody. Scale bar, 5 μm. (B) Mitochondrial length (μm) was quantified and is reported as mean ± SEM; t-test; *P < 0.05; (C) Ultrastructural analysis of melanocytes from a healthy donor (CTRL) and patient UCMD1 (representative of all patients), after treatment with NIM811 (UCMD1 + NIM811). Scale bar, 300 nm.

We measured the OCR of primary cultures of melanocytes from UCMD and BM patients with the sensitive Seahorse technology (Wu et al., 2007). Basal respiration largely reflects mitochondrial oxygen consumption, which in aerobic, non-transformed cells fulfills the needs for ATP synthesis; addition of oligomycin inhibits the F-ATP synthase, and therefore, “removes” the fraction of respiration linked to ATP synthesis. Inspection of the response of melanocytes from healthy donors (Figures 5A–C, closed circles) reveals that a large fraction of the basal OCR is linked to ATP synthesis, as shown by the inhibitory effect of oligomycin (residual oxygen consumption is non-mitochondrial, see below). Melanocytes could be stimulated well above the basal respiratory level by addition of the protonophore FCCP, which stimulates respiration maximally, demonstrating that they have a large respiratory reserve (the difference between OCR after the addition of FCCP and basal OCR). Addition of rotenone (selective inhibitor of respiratory complex I) almost completely inhibited the OCR, no further decrease being seen with the addition of antimycin A (selective inhibitor of complex III). Finally, NIM811 had no effect in the response of melanocytes from healthy donors to oligomycin, FCCP, rotenone, and antimycin A (Figures 5B,C closed triangles). Melanocytes from patients UCMD1, UCMD2, and BM1 displayed a marked decrease of the respiratory reserve, which became apparent after the addition of FCCP (open circles in Figures 5A–C, respectively). In patient BM1, maximal respiration was partially restored by NIM811 but the effect was not statistically significant (Figure 5C). Thus, assessing whether the lower respiratory activity of melanocytes from patients depends on PTP opening will require further work. We also tested the effect of FCCP on basal respiration (i.e., in the absence of oligomycin) with identical results (data not shown). The statistical analysis of these experiments is presented in Figures 5A’–C’. Resting ATP levels were not altered in melanocytes from ColVI patients (results not shown), as also observed in myoblast cultures (Angelin et al., 2008). These findings, which match the maintenance of a normal mitochondrial membrane potential under resting conditions, are consistent with a latent rather than overt mitochondrial dysfunction in cultured melanocytes from the patients.

Figure 5. Oxygen consumption rate of melanocytes. OCR of melanocytes from a healthy donor (closed circles in all panels), of patients (open circles in all panels) UCMD1 (A), UCMD2 (B), and BM1 (C) was measured in 24-well Seahorse plates [60,000 cells/well for (A) and 130,000 cells/well for (B,C)]. Where indicated (arrows) 1 μg/ml oligomycin (O), FCCP as detailed in Section “Materials and Methods” (F), 1 μM rotenone (R), and 1 μM antimycin A (AA) were added. In (B,C), triangles report respiration of melanocytes from healthy donor (closed symbols) or UCMD2 and BM1 patients (open symbols) treated with 0.8 μM NIM811 1 h before beginning the recording. Data in each panel are mean of at least four independent determinations in triplicate ± SEM. (A’–C’) OCR before (Basal) and after the sequential addition of oligomycin (Oligo), FCCP, rotenone, and antimycin A. Data were analyzed with ANOVA. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.005; n.s., not significant.

Epidermal melanocytes interact with the underlying ECM of derma via the DEJ, a specialized adhesion structure consisting of ECM components that include ColVI (Sabatelli et al., 2011). Adhesion of melanocytes to the DEJ involves components common to the muscle cell sarcolemma. Like muscle cells, melanocytes express mDp427 dystrophin (Pellegrini et al., 2013), which bridges the cytoskeleton and the ECM through α, β dystroglycan (Herzog et al., 2004) and the α2 chain of laminin (Sewry et al., 1996). In addition, the DEJ basement membrane is enriched in ColVI, which includes the α5 and α6 chains (Sabatelli et al., 2011) as also recently shown for the endomysium of human muscle (Sabatelli et al., 2012a). ColVI microfilament organization is influenced by the interactions of ColVI with its binding partners (Wiberg et al., 2002). Our findings demonstrate that, like myoblasts (Zou et al., 2008; Sabatelli et al., 2012b), melanocytes do not produce ColVI, yet they bind the protein at the cell surface (Kawahara et al., 2008). Melanocytes do express NG2 proteoglycan (results not shown), which acts as a ColVI receptor (Campoli et al., 2010) together with integrins (Pfaff et al., 1993; Zambruno et al., 1993). The pattern of melanocyte surface labeling with ColVI microfibrils is consistent with receptor-mediated interactions. Interestingly, lack of ColVI affects melanocyte mitochondria in the same way as it affects mitochondria in skeletal muscle, suggesting that this ECM protein exerts a trophic role in the skin as well, consistent with the lesions detected in UCMD and BM patients (Lampe and Bushby, 2005). Indeed, UCMD and BM melanocytes display the same PTP-dependent latent mitochondrial dysfunction previously identified in primary muscle-derived cell cultures from Col6a1−/− mice (Irwin et al., 2003), UCMD and BM patients (Angelin et al., 2007), and zebrafish with ColVI myopathy (Zulian et al., 2014) that manifests itself as an oligomycin-induced depolarization. We have interpreted oligomycin-induced depolarization as a secondary event following mitochondrial Ca2+ overload; this would be a consequence of decreased activity of ATP-dependent Ca2+ pumps, resulting in cytosolic Ca2+ overload because of decreased Ca2+ extrusion at the plasma membrane and decreased Ca2+ uptake from the endo-sarcoplasmic reticulum (Angelin et al., 2008).

The reason why maximal respiration is decreased in melanocytes from ColVI muscular dystrophy patients is not easy to dissect in intact cells, but prominent possibilities are increased cytochrome c release through both PTP-dependent and -independent mechanisms (Clerc et al., 2012), and PTP-dependent pyridine nucleotide depletion (Vinogradov et al., 1972; Di Lisa et al., 2001). Short openings of the PTP that cannot be detected by TMRM redistribution do take place in isolated mitochondria (Hüser et al., 1998; Hüser and Blatter, 1999) and have also been documented in situ (Petronilli et al., 1999). The PTP open time can be increased by Ca2+ overload synergistically with arachidonic acid produced by activation of cPLA2 (Petronilli et al., 2001; Scorrano et al., 2001; Penzo et al., 2004) leading to cytochrome c release (Petronilli et al., 2001), depletion of matrix pyridine nucleotides (Di Lisa et al., 2001), and respiratory inhibition (Vinogradov et al., 1972). Since we found ultrastructural and functional alterations of mitochondria compatible with increased PTP opening in melanocytes from UCMD and BM patients, we suspect that PTP opening is responsible for decreased maximal respiratory capacity as well. Some support for this interpretation comes from the partial restoration of respiration in patient BM1 after treatment with the cyclophilin inhibitor NIM811, which desensitizes the PTP.

The present results show that skin melanocytes from UCMD and BM patients faithfully reproduce the mitochondrial dysfunction and ultrastructural alterations that characterize myoblasts and myofibers from the same patients (Merlini and Bernardi, 2008). These findings may also help to understand the pathogenesis of the skin lesions in patients affected by ColVI muscular dystrophies, and closely match recent results on melanocytes derived from a patient affected by Duchenne muscular dystrophy (Pellegrini et al., 2013). Taken together, our results suggest that melanocytes can become a useful tool to study and monitor other muscle diseases as well, and that skin biopsies may represent a convenient and minimally invasive alternative procedure to monitor muscle genetic diseases and to assess potential therapies ex vivo.

The study was supported in part by a Research Grant from Novartis Pharma AG (Basel).

We thank Dr. Stefano Squarzoni for the rotary shadowing immunoelectron microscope experiment, and Novartis AG (Basel) for providing NIM811. Funding sources: This work was supported by TELETHON Italy (GUP11007 to Luciano Merlini, Patrizia Sabatelli, and Nadir Mario Maraldi and GGP11082 to Nadir Mario Maraldi and Paolo Bernardi), FIRB 2010 RBAP10KCNS and “5 per mille” 2011 Rizzoli Orthopaedic Institute.

BM, Bethlem myopathy; ColVI, collagen VI; Cs, cyclosporin; DEJ, dermal–epidermal junction; ECM, extracellular matrix; FCCP, carbonylcyanide-p-trifluoromethoxyphenyl hydrazone; OCR, oxygen consumption rate; PTP, mitochondrial permeability transition pore; TMRM, tetramethylrhodamine methyl ester; UCMD, Ullrich congenital muscular dystrophy.

Angelin, A., Bonaldo, P., and Bernardi, P. (2008). Altered threshold of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore in Ullrich congenital muscular dystrophy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1777, 893–896. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2008.03.026

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Angelin, A., Tiepolo, T., Sabatelli, P., Grumati, P., Bergamin, N., Golfieri, C., et al. (2007). Mitochondrial dysfunction in the pathogenesis of Ullrich congenital muscular dystrophy and prospective therapy with cyclosporins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 991–996. doi:10.1073/pnas.0610270104

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bernardi, P. (2013). The mitochondrial permeability transition pore: a mystery solved? Front. Physiol. 4:95. doi:10.3389/fphys.2013.00095

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bernardi, P., Scorrano, L., Colonna, R., Petronilli, V., and Di Lisa, F. (1999). Mitochondria and cell death. Mechanistic aspects and methodological issues. Eur. J. Biochem. 264, 687–701. doi:10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00725.x

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bertini, E., and Pepe, G. (2002). Collagen type VI and related disorders: Bethlem myopathy and Ullrich scleroatonic muscular dystrophy. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 6, 193–198. doi:10.1053/ejpn.2002.0593

Bethlem, J., and Wijngaarden, G. K. (1976). Benign myopathy, with autosomal dominant inheritance. A report on three pedigrees. Brain 99, 91–100. doi:10.1093/brain/99.1.91

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Camacho Vanegas, O., Bertini, E., Zhang, R. Z., Petrini, S., Minosse, C., Sabatelli, P., et al. (2001). Ullrich scleroatonic muscular dystrophy is caused by recessive mutations in collagen type VI. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 7516–7521. doi:10.1073/pnas.121027598

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Campoli, M., Ferrone, S., and Wang, X. (2010). Functional and clinical relevance of chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan 4. Adv. Cancer Res. 109, 73–121. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-380890-5.00003-X

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Clerc, P., Carey, G. B., Mehrabian, Z., Wei, M., Hwang, H., Girnun, G. D., et al. (2012). Rapid detection of an ABT-737-sensitive primed for death state in cells using microplate-based respirometry. PLoS ONE 7:e42487. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0042487

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Colombatti, A., and Bonaldo, P. (1987). Biosynthesis of chick type VI collagen. II. Processing and secretion in fibroblasts and smooth muscle cells. J. Biol. Chem. 262, 14461–14466.

Daum, S., Schumann, M., Mathea, S., Aumuller, T., Balsley, M. A., Constant, S. L., et al. (2009). Isoform-specific inhibition of cyclophilins. Biochemistry 48, 6268–6277. doi:10.1021/bi9007287

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Di Lisa, F., Menabò, R., Canton, M., Barile, M., and Bernardi, P. (2001). Opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore causes depletion of mitochondrial and cytosolic NAD+ and is a causative event in the death of myocytes in postischemic reperfusion of the heart. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 2571–2575. doi:10.1074/jbc.M006825200

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Gao, F. L., Jin, R., Zhang, L., and Zhang, Y. G. (2013). The contribution of melanocytes to pathological scar formation during wound healing. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 6, 609–613.

Gara, S. K., Grumati, P., Urciuolo, A., Bonaldo, P., Kobbe, B., Koch, M., et al. (2008). Three novel collagen VI chains with high homology to the alpha3 chain. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 10658–10670. doi:10.1074/jbc.M709540200

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Giorgio, V., von Stockum, S., Antoniel, M., Fabbro, A., Fogolari, F., Forte, M., et al. (2013). Dimers of mitochondrial ATP synthase form the permeability transition pore. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 5887–5892. doi:10.1073/pnas.1217823110

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Grumati, P., Coletto, L., Sabatelli, P., Cescon, M., Angelin, A., Bertaggia, E., et al. (2010). Autophagy is defective in collagen VI muscular dystrophies, and its reactivation rescues myofiber degeneration. Nat. Med. 16, 1313–1320. doi:10.1038/nm.2247

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Herzog, C., Has, C., Franzke, C. W., Echtermeyer, F. G., Schlötzer-Schrehardt, U., Kröger, S., et al. (2004). Dystroglycan in skin and cutaneous cells: beta-subunit is shed from the cell surface. J. Invest. Dermatol. 122, 1372–1380. doi:10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.22605.x

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Hüser, J., and Blatter, L. A. (1999). Fluctuations in mitochondrial membrane potential caused by repetitive gating of the permeability transition pore. Biochem. J. 343(Pt 2), 311–317. doi:10.1042/0264-6021:3430311

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Hüser, J., Rechenmacher, C. E., and Blatter, L. A. (1998). Imaging the permeability pore transition in single mitochondria. Biophys. J. 74, 2129–2137. doi:10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77920-2

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Irwin, W. A., Bergamin, N., Sabatelli, P., Reggiani, C., Megighian, A., Merlini, L., et al. (2003). Mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis in myopathic mice with collagen VI deficiency. Nat. Genet. 35, 267–271. doi:10.1038/ng1270

Jöbsis, G. J., Boers, J. M., Barth, P. G., and de Visser, M. (1999). Bethlem myopathy: a slowly progressive congenital muscular dystrophy with contractures. Brain 122(Pt 4), 649–655. doi:10.1093/brain/122.4.649

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kawahara, G., Ogawa, M., Okada, M., Malicdan, M. C., Goto, Y., Hayashi, Y. K., et al. (2008). Diminished binding of mutated collagen VI to the extracellular matrix surrounding myocytes. Muscle Nerve 38, 1192–1195. doi:10.1002/mus.21030

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kuo, H. J., Maslen, C. L., Keene, D. R., and Glanville, R. W. (1997). Type VI collagen anchors endothelial basement membranes by interacting with type IV collagen. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 26522–26529. doi:10.1074/jbc.272.42.26522

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lampe, A. K., and Bushby, K. M. (2005). Collagen VI related muscle disorders. J. Med. Genet. 42, 673–685. doi:10.1136/jmg.2002.002311

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Menazza, S., Blaauw, B., Tiepolo, T., Toniolo, L., Braghetta, P., Spolaore, B., et al. (2010). Oxidative stress by monoamine oxidases is causally involved in myofiber damage in muscular dystrophy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 19, 4207–4215. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddq339

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Merlini, L., Angelin, A., Tiepolo, T., Braghetta, P., Sabatelli, P., Zamparelli, A., et al. (2008a). Cyclosporin A corrects mitochondrial dysfunction and muscle apoptosis in patients with collagen VI myopathies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 5225–5229. doi:10.1073/pnas.0800962105

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Merlini, L., Martoni, E., Grumati, P., Sabatelli, P., Squarzoni, S., Urciuolo, A., et al. (2008b). Autosomal recessive myosclerosis myopathy is a collagen VI disorder. Neurology 71, 1245–1253. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000327611.01687.5e

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Merlini, L., and Bernardi, P. (2008). Therapy of collagen VI-related myopathies (Bethlem and Ullrich). Neurotherapeutics 5, 613–618. doi:10.1016/j.nurt.2008.08.004

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Merlini, L., Morandi, L., Granata, C., and Ballestrazzi, A. (1994). Bethlem myopathy: early-onset benign autosomal dominant myopathy with contractures. Description of two new families. Neuromuscul. Disord. 4, 503–511. doi:10.1016/0960-8966(94)90091-4

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Millay, D. P., Sargent, M. A., Osinska, H., Baines, C. P., Barton, E. R., Vuagniaux, G., et al. (2008). Genetic and pharmacologic inhibition of mitochondrial-dependent necrosis attenuates muscular dystrophy. Nat. Med. 14, 442–447. doi:10.1038/nm1736

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Nicolli, A., Basso, E., Petronilli, V., Wenger, R. M., and Bernardi, P. (1996). Interactions of cyclophilin with the mitochondrial inner membrane and regulation of the permeability transition pore, a cyclosporin A-sensitive channel. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 2185–2192. doi:10.1074/jbc.271.4.2185

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Pellegrini, C., Zulian, A., Gualandi, F., Manzati, E., Merlini, L., Michelini, M. E., et al. (2013). Melanocytes-A novel tool to study mitochondrial dysfunction in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J. Cell Physiol. 228, 1323–1331. doi:10.1002/jcp.24290

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Penzo, D., Petronilli, V., Angelin, A., Cusan, C., Colonna, R., Scorrano, L., et al. (2004). Arachidonic acid released by phospholipase A2 activation triggers Ca2+-dependent apoptosis through the mitochondrial pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 25219–25225. doi:10.1074/jbc.M310381200

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Pepe, G., Bertini, E., Bonaldo, P., Bushby, K., Giusti, B., de Visser, M., et al. (2002). Bethlem myopathy (BETHLEM) and Ullrich scleroatonic muscular dystrophy: 100th ENMC international workshop, 23-24 November 2001, Naarden, The Netherlands. Neuromuscul. Disord. 12, 984–993. doi:10.1016/S0960-8966(02)00139-6

Petronilli, V., Miotto, G., Canton, M., Brini, M., Colonna, R., Bernardi, P., et al. (1999). Transient and long-lasting openings of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore can be monitored directly in intact cells by changes in mitochondrial calcein fluorescence. Biophys. J. 76, 725–734. doi:10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77239-5

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Petronilli, V., Penzo, D., Scorrano, L., Bernardi, P., and Di Lisa, F. (2001). The mitochondrial permeability transition, release of cytochrome c and cell death. Correlation with the duration of pore openings in situ. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 12030–12034. doi:10.1074/jbc.M010604200

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Pfaff, M., Aumailley, M., Specks, U., Knolle, J., Zerwes, H. G., and Timpl, R. (1993). Integrin and Arg-Gly-Asp dependence of cell adhesion to the native and unfolded triple helix of collagen type VI. Exp. Cell Res. 206, 167–176. doi:10.1006/excr.1993.1134

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Pinon, P., and Wehrle-Haller, B. (2011). Integrins: versatile receptors controlling melanocyte adhesion, migration and proliferation. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 24, 282–294. doi:10.1111/j.1755-148X.2010.00806.x

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Reutenauer, J., Dorchies, O. M., Patthey-Vuadens, O., Vuagniaux, G., and Ruegg, U. T. (2008). Investigation of Debio 025, a cyclophilin inhibitor, in the dystrophic mdx mouse, a model for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Br. J. Pharmacol 155, 574–584. doi:10.1038/bjp.2008.285

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Sabatelli, P., Gara, S. K., Grumati, P., Urciuolo, A., Gualandi, F., Curci, R., et al. (2011). Expression of the collagen VI alpha5 and alpha6 chains in normal human skin and in skin of patients with collagen VI-related myopathies. J. Invest. Dermatol. 131, 99–107. doi:10.1038/jid.2010.284

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Sabatelli, P., Gualandi, F., Gara, S. K., Grumati, P., Zamparelli, A., Martoni, E., et al. (2012a). Expression of collagen VI alpha5 and alpha6 chains in human muscle and in Duchenne muscular dystrophy-related muscle fibrosis. Matrix Biol. 31, 187–196. doi:10.1016/j.matbio.2011.12.003

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Sabatelli, P., Palma, E., Angelin, A., Squarzoni, S., Urciuolo, A., Pellegrini, C., et al. (2012b). Critical evaluation of the use of cell cultures for inclusion in clinical trials of patients affected by collagen VI myopathies. J. Cell. Physiol. 227, 2927–2935. doi:10.1002/jcp.23039

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Santiago-Walker, A., Li, L., Haass, N. K., and Herlyn, M. (2009). Melanocytes: from morphology to application. Skin Pharmacol. Physiol. 22, 114–121. doi:10.1159/000178870

Scorrano, L., Penzo, D., Petronilli, V., Pagano, F., and Bernardi, P. (2001). Arachidonic acid causes cell death through the mitochondrial permeability transition. Implications for tumor necrosis factor-α apoptotic signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 12035–12040. doi:10.1074/jbc.M010603200

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Sewry, C. A., Philpot, J., Sorokin, L. M., Wilson, L. A., Naom, I., Goodwin, F., et al. (1996). Diagnosis of merosin (laminin-2) deficient congenital muscular dystrophy by skin biopsy. Lancet 347, 582–584. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(96)91274-X

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Sorato, E., Menazza, S., Zulian, A., Sabatelli, P., Gualandi, F., Merlini, L., et al. (2014). Monoamine oxidase inhibition prevents mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis in myoblasts from patients with collagen VI myopathies. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 75C, 40–47. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.07.006

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Tagliavini, F., Pellegrini, C., Sardone, F., Squarzoni, S., Paulsson, M., Wagener, R., et al. (2014). Defective collagen VI alpha6 chain expression in the skeletal muscle of patients with collagen VI-related myopathies. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1842, 1604–1612. doi:10.1016/j.bbadis.2014.05.033

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Telfer, W. R., Busta, A. S., Bonnemann, C. G., Feldman, E. L., and Dowling, J. J. (2010). Zebrafish models of collagen VI-related myopathies. Hum. Mol. Genet. 19, 2433–2444. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddq126

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Tiepolo, T., Angelin, A., Palma, E., Sabatelli, P., Merlini, L., Nicolosi, L., et al. (2009). The cyclophilin inhibitor Debio 025 normalizes mitochondrial function, muscle apoptosis and ultrastructural defects in Col6a1-/- myopathic mice. Br. J. Pharmacol. 157, 1045–1052. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00316.x

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ullrich, O. (1930). Kongenitale, atonisch-sklerotische Muskeldystrophie, ein weiterer Typus der heredodegenerativen Erkrankungen des neuromuskulaeren Systems. Z. Ges. Neurol. Psychiatr. 126, 171–201. doi:10.1007/BF02864097

Vinogradov, A., Scarpa, A., and Chance, B. (1972). Calcium and pyridine nucleotide interaction in mitochondrial membranes. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 152, 646–654. doi:10.1016/0003-9861(72)90261-5

Wiberg, C., Heinegård, D., Wenglén, C., Timpl, R., and Mörgelin, M. (2002). Biglycan organizes collagen VI into hexagonal-like networks resembling tissue structures. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 49120–49126. doi:10.1074/jbc.M206891200

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Wissing, E. R., Millay, D. P., Vuagniaux, G., and Molkentin, J. D. (2010). Debio-025 is more effective than prednisone in reducing muscular pathology in mdx mice. Neuromuscul. Disord. 20, 753–760. doi:10.1016/j.nmd.2010.06.016

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Wu, M., Neilson, A., Swift, A. L., Moran, R., Tamagnine, J., Parslow, D., et al. (2007). Multiparameter metabolic analysis reveals a close link between attenuated mitochondrial bioenergetic function and enhanced glycolysis dependency in human tumor cells. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 292, C125–C136. doi:10.1152/ajpcell.00247.2006

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Zambruno, G., Marchisio, P. C., Melchiori, A., Bondanza, S., Cancedda, R., and De Luca, M. (1993). Expression of integrin receptors and their role in adhesion, spreading and migration of normal human melanocytes. J. Cell Sci. 105(Pt 1), 179–190.

Zhang, R. Z., Sabatelli, P., Pan, T. C., Squarzoni, S., Mattioli, E., Bertini, E., et al. (2002). Effects on collagen VI mRNA stability and microfibrillar assembly of three COL6A2 mutations in two families with Ullrich congenital muscular dystrophy. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 43557–43564. doi:10.1074/jbc.M207696200

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Zou, Y., Zhang, R. Z., Sabatelli, P., Chu, M. L., and Bonnemann, C. G. (2008). Muscle interstitial fibroblasts are the main source of collagen VI synthesis in skeletal muscle: implications for congenital muscular dystrophy types Ullrich and Bethlem. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 67, 144–154. doi:10.1097/nen.0b013e3181634ef7

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Zulian, A., Rizzo, E., Schiavone, M., Palma, E., Tagliavini, F., Blaauw, B., et al. (2014). NIM811, a cyclophilin inhibitor without immunosuppressive activity, is beneficial in collagen VI congenital muscular dystrophy models. Hum. Mol. Genet. 23, 5353–5363. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddu254

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Keywords: collagen VI, muscular dystrophy, mitochondria, melanocytes, permeability transition, cyclophilin inhibitors

Citation: Zulian A, Tagliavini F, Rizzo E, Pellegrini C, Sardone F, Zini N, Maraldi NM, Santi S, Faldini C, Merlini L, Petronilli V, Bernardi P and Sabatelli P (2014) Melanocytes from patients affected by Ullrich congenital muscular dystrophy and Bethlem myopathy have dysfunctional mitochondria that can be rescued with cyclophilin inhibitors. Front. Aging Neurosci. 6:324. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2014.00324

Received: 03 July 2014; Accepted: 06 November 2014;

Published online: 20 November 2014.

Edited by:

Emanuele Marzetti, Catholic University of the Sacred Heart, ItalyReviewed by:

Jorgina Satrustegui, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, SpainCopyright: © 2014 Zulian, Tagliavini, Rizzo, Pellegrini, Sardone, Zini, Maraldi, Santi, Faldini, Merlini, Petronilli, Bernardi and Sabatelli. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Paolo Bernardi, Department of Biomedical Sciences, University of Padova,Via Ugo Bassi 58/B, Padova I-35131, Italy e-mail:YmVybmFyZGlAYmlvLnVuaXBkLml0;

Patrizia Sabatelli, Institute of Molecular Genetics-CNR, Bologna I-40136, Italy e-mail:c2FiYXRlbGxpQGFyZWEuYm8uY25yLml0

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.