- 1Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology, Henry Wellcome Building, University of Leicester, Leicester, United Kingdom

- 2Leicester Institute of Structural and Chemical Biology, Henry Wellcome Building, University of Leicester, Leicester, United Kingdom

- 3WestCHEM and Department of Pure and Applied Chemistry, University of Strathclyde, Glasgow, United Kingdom

- 4School of Chemistry, University of Leicester, Leicester, United Kingdom

- 5Biomedical Engineering Research Division, School of Engineering, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, United Kingdom

Protein-RNA interactions are central to numerous cellular processes. In this work, we present an easy and straightforward NMR-based approach to determine the RNA binding site of RNA binding proteins and to evaluate the binding of pairs of proteins to a single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) under physiological conditions, in this case in nuclear extracts. By incorporation of a 19F atom on the ribose of different nucleotides along the ssRNA sequence, we show that, upon addition of an RNA binding protein, the intensity of the 19F NMR signal changes when the 19F atom is located near the protein binding site. Furthermore, we show that the addition of pairs of proteins to a ssRNA containing two 19F atoms at two different locations informs on their concurrent binding or competition. We demonstrate that such studies can be done in a nuclear extract that mimics the physiological environment in which these protein-ssRNA interactions occur. Finally, we demonstrate that a trifluoromethoxy group (-OCF3) incorporated in the 2′ribose position of ssRNA sequences increases the sensitivity of the NMR signal, leading to decreased measurement times, and reduces the issue of RNA degradation in cellular extracts.

1 Introduction

The interaction between RNAs and RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) is an essential, fundamental, and highly regulated cellular process. A large number of proteins regulate post-transcriptional gene expression, such as splicing and translation (Baltz et al., 2012); indeed, there are approximately 800 RBPs in humans (Castello et al., 2012). Modulation of their interaction with RNA or changes in their levels of expression can lead to neurodegenerative diseases and cancers (Cieply and Carstens, 2015; Kelaini et al., 2021; Prashad and Gopal, 2021; Mehta et al., 2022; Sanya et al., 2023). Many RBPs act on pre-mRNA splicing to regulate the production of alternative isoforms of mRNA, leading to the production of different proteins with different functions or to the production of isoforms with poison exons (exons containing premature termination codons) that downregulate protein expression (Jobbins et al., 2023; Manabile et al., 2023; Nikom and Zheng, 2023) These RBPs interact specifically with their pre-mRNA targets through various RNA binding domains (RBDs) such as an RNA Recognition Motif (RRM) (Maris et al., 2005; Daubner et al., 2013) or a KH domain (Valverde et al., 2008; Nicastro et al., 2015). These small domains generally only recognize specifically 3 to 5 nucleotides of a single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) with moderate affinities (dissociation constants in the micromolar range) and the high affinity and specificity of RBPs towards RNA comes from the fact that most splicing factors contain multiple RBDs, each binding a different region of the same RNA. Pre-mRNAs often contain binding sites for many different RBPs in or near their exons and the cooperative or competitive binding of these RBPs to the ssRNA is believed to ultimately dictate the outcome of alternative splicing events (Nag et al., 2022).

NMR spectroscopy is a powerful tool to study protein-RNA interactions at the atomic level (Pellecchia, 2005; Dominguez et al., 2011; Furukawa et al., 2016; Teilum et al., 2017). However, NMR studies of macromolecules requires the labelling of one macromolecule with an “NMR-visible” isotope. While 13C and 15N isotope labelling of proteins is routine, this precludes the possibility of following the binding at the level of the RNA. This is especially problematic if there is more than one binding site for the protein on the RNA, or if there is any intention to follow the binding of two or more proteins to the same RNA molecule. Labelling of RNA with 13C and/or 15N is less straightforward and requires either complex chemical synthesis or in vitro transcription of the RNA using expensive 13C-labelled nucleotides (Nikonowicz et al., 1992; Batey et al., 1995; Wenter et al., 2006). Furthermore, because the 1H chemical shift distribution of atoms in ssRNA is narrow, their specific assignment is difficult due to signal overlap and therefore NMR spectroscopy studies of ssRNAs are generally limited to short oligonucleotides.

Some of these limitations can be avoided by the use of fluorine atoms at specific sites within biomolecules, such as RNA (Gronenborn, 2022). The natural isotope of fluorine, 19F, has a 100% natural abundance, possesses a spin of ½, has a high NMR sensitivity and covers a much wider chemical shift range than 1H (Dolbier, 2009). Like 1H, the chemical environment of a 19F atom strongly affects its chemical shift. This has allowed the use of 19F NMR spectroscopy to investigate RNA secondary structures and protein conformations (Kreutz et al., 2005; Sharaf and Gronenborn, 2015; Sharaf et al., 2016; Overbeck et al., 2023). Although fluorine atoms are not naturally present in most macromolecules such as proteins and nucleic acids, they can be incorporated at specific positions in nucleotides and amino acids by chemical modifications (Kreutz et al., 2005; Scott and Hennig, 2016). Structural investigations of RNAs using 19F NMR have been performed by incorporating 19F atoms at position 4′of the ribose of uridines (Li et al., 2020), at position 5 on the bases of cytidines and uridine (Becette et al., 2020; Nußbaumer et al., 2020; Sudakov et al., 2023), at position 2 of adenine (Scott et al., 2004), at position 2′on the ribose of any nucleotide (Kreutz et al., 2005; Fauster et al., 2012; Himmelstoss et al., 2020), or at the 5′end of the RNA by adding a 3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)phenyl/Benzyl group (Bao and Xu, 2018, 2020). Protein-RNA interactions have also been investigated by 19F NMR: while most studies relied on incorporation of fluorinated amino acids into proteins (Campos-Olivas et al., 2002; Cellitti et al., 2008; Crowley et al., 2012; Sharaf and Gronenborn, 2015; Matei and Gronenborn, 2016; Sharaf et al., 2016; Dujardin et al., 2018; Gronenborn, 2022), in some cases, fluorine was incorporated into RNAs to investigate their interaction with proteins or small molecules (Fauster et al., 2012; Himmelstoss et al., 2020; Gronenborn, 2022), or to monitor the modification of an RNA by an enzyme (Li et al., 2020). In these cases, it was shown that protein binding induced either a chemical shift change, or a broadening of the 19F signal. However, these studies were done on structured RNAs, not ssRNAs, and the position of the 19F atom was chosen mainly to investigate the structure of the RNA rather than the interaction with proteins.

All the NMR studies mentioned above were done in vitro in NMR suitable buffers. However, NMR studies in cellular extracts (bacterial, xenopus oocytes, mammalian) have demonstrated that it is also possible to obtain structural information on macromolecules, such as proteins and nucleic acids, in physiological conditions and they are easier to conduct than in-cell NMR (Luchinat and Banci, 2022; Theillet and Luchinat, 2022). For example, NMR studies of nucleic acids in cell extract has been carried out to monitor the maturation of tRNAs in yeast extract (Barraud et al., 2019) or to analyse ssDNA/protein interaction by 19F labelling of the protein and NMR analysis in E. coli cell lysate (Welte et al., 2021).

Here we demonstrate that 19F labelling of a ssRNA at different specific positions allows for the mapping of different RBP binding sites and can inform on the concurrent or competitive binding of pairs of RBPs to the ssRNA, using 19F NMR spectroscopy in the presence of mammalian cells nuclear extracts. This involved the incorporation of 2′-F or 2′-OCF3 nucleotides at specific positions within a portion of the SMN2 pre-mRNA and measuring 1D 19F NMR spectra in HeLa nuclear extract, in the absence or presence of individual or pairs of three RBPs, Sam68, hnRNP A1 and SRSF1.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Overexpression and purification of the proteins

The DNA sequence coding for Sam68 QUA1KH (Uniprot: Q07666, amino acids 96–260) and hnRNP A1 RRM12 (Uniprot: P09651, amino acids 1–218) were cloned in the pLEICS-01 vector (https://le.ac.uk/mcb/facilities-and-technologies/protex/) that contains the sequence encoding for a N-terminal hexa-Histine tag followed by a TEV protease site and a gene for Ampicillin resistance. The DNA sequence coding for SRSF1 RRM12 (Uniprot: Q07955, amino acids 1–196 with Y37S and Y72S mutations in RRM1) was cloned in the plasmid pET24b that contains the sequence encoding for a N-terminal GB1-His-TEV tag.

All proteins were purified as described previously (Barraud and Allain, 2013; Cléry et al., 2013; Feracci et al., 2016). In brief, plasmid DNAs were transformed into Rosetta BL21 DE3 cells and the protein expression was induced by the addition of 0.5 mM (Sam68 and hnRNP A1) or 1 mM (SRSF1) of isopropylthiogalactosidase (IPTG) for 16 h at 25°C. Proteins were purified by affinity chromatography using Ni-NTA agarose (Quiagen) and dialysed overnight in the presence of TEV protease. SRSF1 was separated from the GB1-His-TEV tag by NI-NTA affinity chromatography. Sam68 and hnRNP A1 were further purified by gel filtration using a Superdex 75 column (GE Healthcare). Sam68, SRSF1 and hnRNP A1 were dialysed against the NMR buffer (20 mM NaHPO4 pH 6.5, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM beta-mercaptoethanol, 50 mM L-Arginine, 50 mM L-Glutamate). Protein concentration was estimated by measuring the absorbance at 280 nm and using theoretical molar absorption coefficients of 7450 M-1 cm-1 for Sam68, 13,075 M-1 cm-1 for A1 and 22,015 M-1 cm-1 for SRSF1.

2.2 Chemical synthesis of fluorinated RNAs

2′Fluoro (2′-F) RNAs:

The 2′-F RNAs were chemically synthesized by Dharmacon (Horizon Discovery) with one fluorine modification in RNA1 and two in RNA2:

RNA1: UUACA-(2′-F-G)GGUUUUAGACAAAAU.

RNA2: UUACA-(2′-F-G)GGUUUUAGACAAA-(2′-F-A)U.

Fluorine was inserted in the 2′position on the ribose of G6 of RNA1 and G6 and A20 of RNA2.

2′-O-Trifluoromethylated (2′-OCF3) RNA:

The 2′-OCF3 adenosine phosphoramadite was chemically synthesized following a previously published protocol (Himmelstoss et al., 2020) (see Supplementary Material S1). This phosphoramadite was then incorporated by chemical synthesis (Horizon Discovery) at position A20 in RNA3:

RNA3: UUACAGGGUUUUAGACAAA-(2′-OCF3-A)U.

2.3 Nuclear extract

Nuclear Extract from HeLa cells was purchased from Ipracell (catalogue number: CC-01–20–005).

2.4 NMR sample preparation

Lyophilised RNAs received from Dharmacon were dissolved in 20 μL of NMR buffer and heated to 95°C for 5 min then snap cooled to 4°C in ice. RNA concentrations were estimated by measuring the absorbance at 260 nm using an extinction coefficient of 224,300 M-1 cm-1 for 2′-F-RNAs and 229,000 M-1 cm-1 for 2′-OCF3-RNA.

For the RNA only samples, the RNAs were diluted to a final concentration of 100 or 200 μM in 600 µL NMR buffer containing 10% D2O. For RNA/protein samples, the RNAs were mixed with Sam68 QUA1-KH, hnRNPA1 RRM12 or SRSF1 RRM12, 10% D2O and buffer to a final volume of 600 µL with final concentrations of 200 µM for the RNA and 400 µM for the proteins (2′-F-RNA experiments) or 100 µM of RNA and 200 µM of protein (2′-OCF3-RNA experiments).

2.5 NMR experiments

600 µL of RNA or RNA/protein mixture were inserted into 5 mm NMR tubes. All NMR spectra were recorded at 303 K (typical temperature used for in vitro splicing assays) on a Bruker AVIII-600 MHz spectrometer equipped with a 5 mm HF SEF probe with z-gradients. 1D 19F spectra of the 2′-F-RNAs samples were acquired with a spectral width of 20 ppm, a frequency offset of −202 ppm, and a total acquisition time of 100 ms. The total number of scans was 3,840 (1.5 h per experiment). 1D 19F spectra of the 2′-OCF3 RNA samples were acquired with a spectral width of 20 ppm, a frequency offset of −60 ppm, and a total acquisition time of 100 ms. The number of scans was 1,024 for the comparison between 2′-F-RNA2 and 2′-OCF3 RNA3 (29 min per experiment) and 256 for the experiment with 2′-OCF3 RNA, 40% nuclear extract in the absence or presence of Sam68 QUA1-KH (7 min per experiment). NMR data were processed and analysed using TOPSPIN 3.6 (Bruker). All the experiments were zero-filled to 8,192 points, and a 6 Hz exponential window function applied.

2.6 Electromobility shift assays (EMSA)

EMSA assays were done using 14% polyacrylamide (40% (w/v)29:1 Acrylamide:Bis-Acrylamide) gels in TBE buffer (Tris 0.13 M, Borate 45 mM, EDTA 2.5 mM pH 7.6 and run in TBE buffer at 4° at 160 V for 1 h, using Xylene cyanol as loading dye. Gels were stained with toluidine blue for 5 min, then rinsed with water overnight on a gel rotator.

2.6.1 Binding of Sam68 to fluorinated RNAs versus unmodified RNA

All the samples contained 2 μL of unmodified RNA2 or 2′F-RNA2 or 2′-OCF3-RNA3 at a final concentration of 40 μM. Then, 10 μL of NMR buffer for the free RNA sample or 10 μL of protein in NMR buffer were added to obtain different final concentrations of Sam68: 10 μM, 50 μM, 100 μM or 200 μM. Finally, 3 μL of Xylene Cyanol non denaturing loading dye was added to each sample.

2.6.2 Competition assay for SRSF1 and Sam68 for binding to 2′F-RNA

The RNA concentration was 40 μM in all samples and the proteins concentrations (Sam68 or SRSF1) were 80 μM. Samples in nuclear extract contained the same concentrations of RNA and proteins with the addition of 40% HeLa nuclear extract.

3 Results

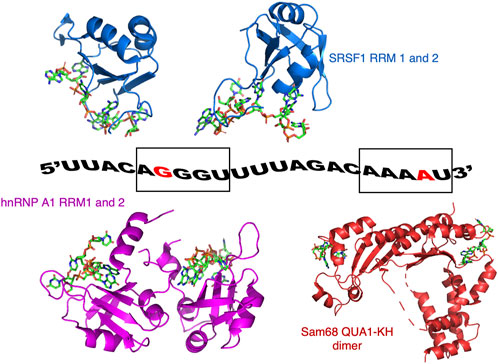

In our study, we have used a 21-nucleotide portion of SMN2 pre-mRNA (encompassing the 3′end of intron 6 and the 5′end of exon 7) and the RBDs of three proteins: Sam68 QUA1-KH domain, SRSF1 RRM1-2 domains and hnRNP A1 RRM1-2 domains (Figure 1). Based on biochemical data (Wee et al., 2014) and structural work (Barraud and Allain, 2013; Cléry et al., 2013; Feracci et al., 2016; Beusch et al., 2017), this RNA contains binding sites for SRSF1 (GG (A/G)), hnRNP A1 ((U/C)AGG) and Sam68 ((A/U)AA (Figure 1). The SRSF1 and hnRNP A1 binding sites overlap near the 5′end of the RNA, while the Sam68 binding site is located near the 3′end (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1. Model of ssRNA/protein binding used in this study. The RNA corresponds to a portion of the SMN2 pre-mRNA. The guanine at position 6 (G6) and the adenine at position 20 (A20) that were 19F labelled on their 2′ribose position are coloured red. G6 is part of the AGGGUU motif that binds SRSF1 and hnRNP A1, while A20 is part of the AAAAU motif binding Sam68. Also shown are the structures of SRSF1 RRM1 and RRM2 bound to RNA (pdb codes: 6HPJ and 2M8D), hnRNP A1 RRM1 and RRM2 bound to RNA (pdb codes: 5MPG and 5MPL), and a structural model of Sam68 bound to RNA based on the structure of the homologous protein T-STAR (pdb code: 5ELT).

2′fluorinated (2′-F) nucleotides were used as these nucleotides are commercially available and do not affect RNA thermodynamic stability or structure (Kreutz et al., 2005). Furthermore, the 2′position is rarely involved in ssRNA-protein complex formation (Dominguez et al., 2011; Corley et al., 2020), and 2′-F nucleotides are sensitive to conformational changes in RNA structures and protein binding (Kreutz et al., 2005). Thus, we hypothesized that 19F labelling of the ribose 2′ position would provide a useful tool for investigating the simultaneous binding profile of several RBPs in physiological conditions. To confirm that the 2′-F modification does not significantly interfere with the binding of RBPs, we tested the binding of Sam68 with the unmodified and 2′-F-modified RNA using electromobility shift assay (EMSA) (Supplementary Figure S1). As expected, Sam68 binds both RNAs at the concentrations used for the NMR studies.

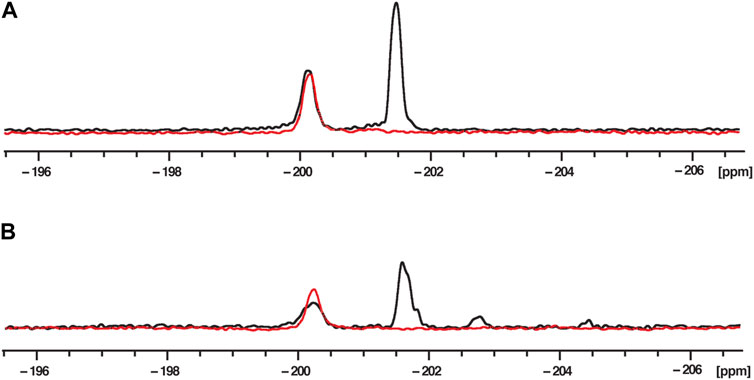

To assign the chemical shifts of the 19F NMR signals, two 2′-F RNA sequences were used. The first RNA (RNA1) contained a single 2′-F nucleotide at position 6 (G6) in the middle of the hnRNP A1 and SRSF1 binding sites, while the second RNA (RNA2) contained two 2′-F nucleotides at positions G6 and at position 20 (A20), in the Sam68 binding site (Figure 1). 1D 19F NMR spectra of these RNAs were recorded in the absence of proteins in buffer (Figure 2A). The 19F NMR spectrum of RNA2 containing two 2′-F nucleotides (G6 and A20) shows two distinct peaks, one at −200.2 ppm and one at −201.5 ppm (black), while the spectrum of RNA1 containing a single 2′-F nucleotide (G6), displays a single peak at −200.2 ppm (red). We conclude that the peak at −200.2 ppm corresponds to the G6 19F signal and the peak at −201.5 ppm corresponds to the A20 19F signal. This indicates that the 19F signal at position 2′of the ribose is highly sensitive to the nature of the base and/or to its local environment in the RNA, and hence allows the differentiation of the two positions in the ssRNA.

FIGURE 2. 19F NMR spectra at 303K of fluorinated RNAs in phosphate buffer (A) and nuclear extract (B). RNA2 containing two 2′-F at G6 and A20 (UUACA-(2′-F-g)GGUUUUAGACAAA-(2′-F-A)U) is in black and RNA1 containing only one 2′-F at G6 (UUACA-(2′-F-g)GGUUUUAGACAAAAU) is in red. The RNA concentration was 200 μM and the total NMR measurement time per spectrum was 1.5 h (3,840 scans).

To mimic the physiological conditions of the RNA-RBP interactions, 19F 1D NMR spectra were acquired in the presence of 40% HeLa nuclear extract (Figure 2B), because this reflects the amount of nuclear extract typically used to recapitulate splicing events in in vitro splicing assays (Higgins and Hames, 1994; Eperon et al., 2000). The spectra showed signals at the same chemical shifts as those recorded in phosphate buffer, as we observe two peaks at −200.2 and −201.5 ppm for RNA2, and only one peak (−200.2 ppm) for RNA1. While the peaks observed in nuclear extract are slightly broader than those in buffer, they are clearly visible and suitable to investigate the effect of protein addition on these signals. Minor peaks are also observed between −202 and −206 ppm and we suspected that they arise from the partial degradation of the RNA due to the presence of RNAses in the nuclear extract. We therefore incubated RNA2 in 40% nuclear extracts and measured 1D 19F spectra as a function of time (Supplementary Figure S2). As expected, the signals of G6 and A20 disappear with time (after 10 and 6 h, respectively, which is consistent with A20 being located one nucleotide from the 3′end of the RNA while G6 is located 6 nucleotides from the 5′end), confirming that the peaks observed between −202 and −206 ppm arise from RNA degradation in the nuclear extract. Indeed, we can speculate that the new peak at −202.7 ppm corresponds to a partial degradation of the 3′end of the RNA because this peak appears almost immediately after addition of nuclear extract (within 10 min) and seems to correlate with the rapid disappearance of the A20 signal. The degradation peak at −204.7 ppm could be due to 5′end degradation because it appears later (after about 1 h) and correlates with the disappearance of the G6 peak. We could then assume that the peak at −203.2 ppm that appears much later (after 2 h) corresponds to the signals of both G6 and A20 when the RNA is fully degraded. In that case, the 2′-F of both G6 and A20 experience the same chemical environment and therefore have the same chemical shift.

It is therefore important to measure the NMR spectra immediately after the addition of the nuclear extract to the RNA. In conclusion, our data demonstrate that it is possible to observe and differentiate two 19F signals located in two different positions of the same ssRNA even in the presence of nuclear extracts.

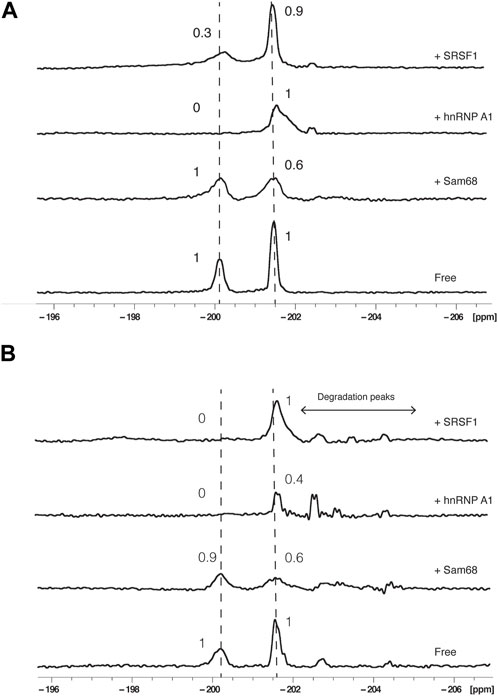

Next, the RBDs of Sam68, SRSF1 or hnRNP A1 were added to RNA2 in molar excess (RNA:protein molar ratio of 1:2) and 19F NMR spectra were recorded either in buffer (Figure 3A) or in presence of 40% nuclear extract (Figure 3B). Addition of the proteins did not lead to obvious chemical shift changes but induced a decrease and a broadening of the signals. We therefore analysed our data by integrating the relative peak area of each signal and calculating the ratios of these integrals before and after the addition of the proteins using the formula:

FIGURE 3. Effect of proteins on 19F signals of fluorinated RNA. 19F NMR spectra at 303K of RNA2 in the absence or presence of Sam68, hnRNP A1 or SRSF1 RNA binding domains in the absence (A) or presence of 40% nuclear extract (B). The total NMR measurement time per spectrum was 1.5 h (3,840 scans). Peak area ratios are indicated.

Where I is the peak integral in the presence of protein and I0 is the peak integral in the absence of protein.

The results were similar in either buffer (Figure 3A) or in the presence of 40% nuclear extract (Figure 3B): Addition of Sam68 did not alter the signal of G6 (PIR of 1 and 0.9 in buffer and nuclear extract, respectively) but induced a reduction in the PIR of A20 (0.6 in both conditions), consistent with Sam68 only interacting with the motif AAAAU (Feracci et al., 2016). In contrast, the addition of SRSF1 affected the signal of G6 (PIR of 0.3 and 0) but not A20 (PIR of 0.9 and 1), consistent with SRSF1 only interacting with the UACAGGGU motif (Cléry et al., 2013). Addition of hnRNP A1 strongly affected the signal of G6 (PIR of 0 in both conditions) but also induced a broadening but no reduction in peak integral (PIR of 1) of the A20 signal in buffer conditions, while in the presence of nuclear extract, the A20 signal intensity is reduced (PIR of 0.4). This suggest that hnRNP A1 binds predominantly the CAGGGU motif as expected (Barraud and Allain, 2013; Beusch et al., 2017), but the binding also slightly influences the chemical environment of A20, possibly through weaker binding near this motif as suggested previously (Kashima and Manley, 2003; Cartegni et al., 2006). In the presence of nuclear extracts, we also observe minor peaks between −202 and −205 ppm resulting from the partial degradation of the RNA in the nuclear extract. These peaks are also observed following the addition of the proteins (notably hnRNP A1 and SRSF1) and could be due to trace amount of RNAses present in the protein samples after purification. It is worth noting that the degradation peaks observed are more prominent upon addition of hnRNP A1 or SRSF1 than addition of Sam68. This is consistent with the fact that SRSF1 and hnRNP A1 bind near the 5′end of the RNA, leaving the 3′end accessible to RNAses, while Sam68 binding near the 3′end protects the RNA from 3′end degradation. The fact that the major degradation peak observed in these experiments is at −202.7 ppm is also consistent with our previous assumption that this peak is associated with 3′end degradation of the RNA.

Taken together, these data demonstrate that addition of RBPs affect predominantly the NMR signal located near the protein binding site (G6 for hnRNP A1 and SRSF1, and A20 for Sam68) indicating that it is possible to identify the RNA motif bound by a protein using 19F NMR, even in the presence of nuclear extracts.

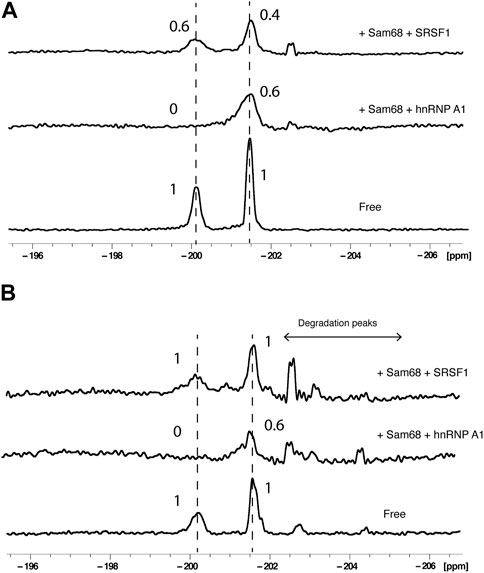

Next, we added pairs of proteins to RNA2 at a RNA:protein:protein molar ratio of 1:2:2 and acquired 1D 19F spectra either in the absence (Figure 4A) or presence of 40% nuclear extract (Figure 4B). The addition of Sam68 and hnRNP A1 led to changes in the PIR of both peaks, very similar to the effect of Sam68 alone on the A20 signal (PIR of 0.6) or the effect of hnRNP A1 alone on the G6 signal (PIR of 0). This demonstrates that both proteins can bind concurrently to the RNA, both in buffer and in nuclear extract. In contrast, the addition of Sam68 and SRSF1 led to a different outcome. In buffer, the PIR for the A20 signal was 0.4, slightly lower than the PIR observed with Sam68 alone (0.6) indicating that Sam68 is binding the RNA in the presence of SRSF1. However, the PIR for the G6 signal was 0.6, which is higher than the PIR observed with SRSF1 alone (0.3), suggesting that SRSF1 binding might be weakened by the presence of Sam68. In nuclear extract the effect is more pronounced and the signals of G6 and A20 display a PIR of 1, indicating that when added together, Sam68 and SRSF1 do not bind, or bind weakly to the RNA. This suggests that these two RBP domains compete for binding the RNA, leading to a reduction in their binding affinity and ultimately their displacement from the RNA in the presence of other RNA binding proteins that are present in the nuclear extract. To confirm these results, we tested the binding of Sam68, SRSF1 or an equimolar amount of Sam68 and SRSF1 in buffer and in nuclear extract by EMSA (Supplementary Figure S3). In buffer, Sam68, SRSF1 and the Sam68/SRSF1 pair bind the RNA, although in the case of the Sam68/SRFS1 pair, it is not possible to determine whether both proteins or only one of them binds the RNA, since the bands corresponding to the RNA/Sam68 and RNA/SRSF1 complex overlap. In contrast, in nuclear extract, it is clear that while Sam68 and SRSF1 bind the RNA, the RNA remains free when both proteins are added together. These results are in agreement with our 19F NMR data.

FIGURE 4. Effect of pairs of proteins on 19F signals of fluorinated RNA. 19F NMR spectra at 303K of RNA2 in the absence or presence of pairs of proteins (Sam68 + hnRNP A1 or Sam68 + SRSF1) in the absence (A) or presence of 40% nuclear extract (B). The total NMR measurement time per spectrum was 1.5 h (3,840 scans). Peak area ratios are indicated.

Taken collectively, these data demonstrate that labelling a single RNA with 2′-F at two different positions is an effective tool to investigate the concurrent or competitive binding of pairs of RBPs on a single ssRNA by 19F NMR spectroscopy, and that the presence of nuclear extract influences the binding of pairs of proteins.

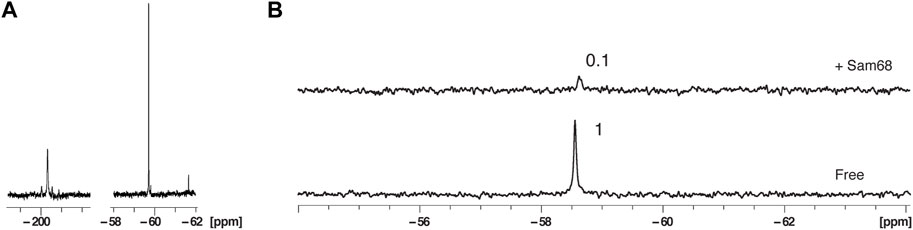

Our results above demonstrate that 19F NMR allows to investigate the binding of RBDs to a ssRNA in physiological conditions. However, RNA degradation is an issue and requires rapid sample preparation and acquisition time. One way of reducing acquisition time is to increase the concentration of the RNA and protein. However, fluorinated RNAs are costly, and many RBPs have a tendency to precipitate at higher concentrations. Recently, it was shown that 2′-O-trifluoromethylated (2′-OCF3) RNAs have the advantage of significant enhanced signal to noise compared to 2′-F due to the increased number of chemically equivalent 19F atoms and the absence of 1H-19F J-couplings (Himmelstoss et al., 2020) (Supplementary Figure S4). The synthesis of 2′-OCF3 phosphoramadites has previously been described for adenosine and cytosine (Himmelstoss et al., 2020), and more recently for guanosine and uridine (Eichler et al., 2023).

We therefore synthesized a 2′-OCF3 adenosine phosphoramidite (for details, see Supplementary Material S1) and incorporated it at position 20 of the ssRNA: UUACAGGGUUUUAGACAAA-(2′-OCF3-A)U (RNA3). To confirm that the 2′-OCF3 modification does not significantly interfere with the binding of RBPs, we tested the binding of Sam68 with the unmodified and 2′-OCF3-modified RNA using electromobility shift assay (EMSA) (Supplementary Figure S5). While the binding of Sam68 to the 2′-OCF3 RNA appears to be weaker than with the unmodified RNA, probably due to the bulkiness of the 2′-OCF3 compared to 2′-F, the binding still occurs at the concentrations used for the NMR studies (200 μM of protein).

We compared the 1D 19F NMR spectra of RNA3 in 40% nuclear extract at a concentration of 100 μM with the 1D spectrum of the 2′-F RNA (RNA2) in 40% nuclear extract at a concentration of 200 μM (total NMR measurement time for each spectrum of 29 min). As expected, the 19F NMR signal intensity of the 2′-OCF3 RNA3 is significantly higher than the 19F intensity of the 2′-F RNA2 even with half the concentration (Figure 5A), demonstrating that a suitable NMR signal can be obtained with shorter measurement times.

FIGURE 5. Effect of 2′-OCF3 labelling on 19F NMR signal sensitivity and protein binding in the presence of nuclear extract. (A) 1D NMR spectra at 303K of fluorinated 2′F-RNA at position A20 at a concentration of 200 μM (left) and fluorinated 2′-OCF3-RNA at position A20 at a concentration of 100 μM (right). The total NMR measurement time per spectrum was 29 min (1,024 scans). (B) 1D NMR spectra at 303K of the 2′-OCF3-RNA in the presence of 40% nuclear extract before and after addition of Sam68 at a RNA:protein ratio of 1:2. The total NMR measurement time per spectrum was 7 min (256 scans).

We next incubated RNA3 at a concentration of 100 μM in 40% nuclear extract and measured a 1D 19F spectrum in the absence or presence of Sam68 at a RNA:protein molar ratio of 1:2 (Figure 5B). The total NMR measurement time per spectrum was 7 min. As for the 2′-F RNA, the addition of Sam68 leads to a strong reduction of the 19F signal (PIR of 0.1). However, we do not observe any additional peaks as a result of RNA degradation. The fact that Sam68 induces a stronger reduction of the 2′-OCF3 signal (PIR of 0.1) than the 2′-F signal (PIR of 0.6, Figure 3B) could be due to the lower affinity of Sam68 for the 2′-OCF3 modified RNA in comparison to the 2′-F RNA (Supplementary Figure S5). In that case, at the concentrations used, only partial saturation of the binding site has occurred for the 2′-OCF3 RNA resulting in extensive line broadening (intermediate exchange regime) whereas the binding site is fully occupied for the 2′-F RNA and the signals are broadened due to an increase in correlation time experienced by the 19F.

4 Discussion

Our results demonstrate that 19F-labelling of RNAs is a powerful tool to i) probe the interaction between ssRNAs and one or more proteins at near-nucleotide resolution and in physiological conditions and ii) investigate competition or concurrent binding to the ssRNA. The use of fluorine has the important advantage of facilitating the NMR analysis since fluorine is, in contrast to protons, rarely present in cells, has nearly the same sensitivity as protons (Dolbier, 2009; Gronenborn, 2022) and when incorporated at the 2′position does not affect the thermodynamic stability of the RNA (Kreutz et al., 2005). In this work, the labelling of the RNA at two different nucleotides generates two separate signals, allowing the identification of the RNA motif bound by each protein. Because all nucleotides can be 19F-labelled by chemical synthesis, this method would allow for a faster and precise mapping of the RNA motif bound by specific splicing factors, without the need for 15N and 13C labelling and resonance assignment of the RNA. The approach presented here also demonstrates that the presence of 40% nuclear extract does not affect significantly the 19F NMR signals, although it does induce RNA degradation, but this issue can be solved by using 2′-OCF3 labelled RNAs, indicating that it is possible to study protein-ssRNA interactions in physiological conditions. The synthesis of fluorinated phosphoramadites at different positions of the sugar or the base have been reported (Scott et al., 2004; Kreutz et al., 2005; Fauster et al., 2012; Scott and Hennig, 2016; Bao and Xu, 2018, 2020; Becette et al., 2020; Himmelstoss et al., 2020; Li et al., 2020; Nußbaumer et al., 2020; Sudakov et al., 2023). While here we demonstrate the power of 19F NMR for protein-ssRNA interaction using modification at the 2′position, it is probable that modifications at other positions of the sugar would also be suitable. However, modifications on the base might affect the affinity of the protein to the RNA since protein-ssRNA interactions mainly occur through the RNA bases (Maris et al., 2005; Valverde et al., 2008; Daubner et al., 2013; Nicastro et al., 2015).

We also demonstrate that using two fluorine signals at different nucleotides of the same RNA allows the identification of concurrent or competitive binding of pairs of proteins. Our study was done at single concentrations of proteins to a final RNA:proteins ratio of 1:2:2, but it would be possible to investigate the binding of individual or pairs of proteins more quantitatively by doing NMR titration experiments with various RNA:protein molar ratios. This would provide additional information, for example, an estimate of the affinity of each protein or pairs of proteins for the RNA. While our study was done with a 21-nucleotide ssRNA and only with pairs of proteins, we believe that similar investigations could be done with longer functional RNAs and more than two proteins added simultaneously, providing a precise mapping of RBPs binding sites and information on their competition or concomitant for ssRNA binding in physiological conditions. Accordingly, it was demonstrated recently that 19F NMR analysis can be used to investigate ligand binding to an 86-nucleotide RNA riboswitch containing a single 5-fluorocytidine that was incorporated by splint ligation (Sudakov et al., 2023).

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

HK: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing. AA: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing–review and editing. FM: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing–review and editing. CB-A: Methodology, Writing–review and editing. VP: Methodology, Writing–review and editing. AT-S: Methodology, Writing–review and editing. ST: Methodology, Writing–review and editing. MV: Methodology, Writing–review and editing. ZZ: Methodology, Writing–review and editing. AC: Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Writing–review and editing. AH: Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Writing–review and editing. IE: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing–review and editing. GB: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing–review and editing. CD: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by a Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) sLoLa grant (BB/T000627/1) to AC, AH, GB, IE, and CD.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Antoine Cléry and Frederic Allain (ETH, Zurich, Switzerland) for providing the clone of SRSF1.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmolb.2024.1325041/full#supplementary-material

References

Baltz, A. G., Munschauer, M., Schwanhausser, B., Vasile, A., Murakawa, Y., Schueler, M., et al. (2012). The mRNA-bound proteome and its global occupancy profile on protein-coding transcripts. Mol. Cell 46 (5), 674–690. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2012.05.021

Bao, H. L., and Xu, Y. (2018). Investigation of higher-order RNA G-quadruplex structures in vitro and in living cells by 19F NMR spectroscopy. Nat. Protoc. 13 (4), 652–665. doi:10.1038/nprot.2017.156

Bao, H. L., and Xu, Y. (2020). Telomeric DNA-RNA-hybrid G-quadruplex exists in environmental conditions of HeLa cells. Chem. Commun. (Camb) 56 (48), 6547–6550. doi:10.1039/d0cc02053b

Barraud, P., and Allain, F. H. (2013). Solution structure of the two RNA recognition motifs of hnRNP A1 using segmental isotope labeling: how the relative orientation between RRMs influences the nucleic acid binding topology. J. Biomol. NMR 55 (1), 119–138. doi:10.1007/s10858-012-9696-4

Barraud, P., Gato, A., Heiss, M., Catala, M., Kellner, S., and Tisné, C. (2019). Time-resolved NMR monitoring of tRNA maturation. Nat. Commun. 10 (1), 3373. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-11356-w

Batey, R. T., Battiste, J. L., and Williamson, J. R. (1995). Preparation of isotopically enriched RNAs for heteronuclear NMR. Methods Enzymol. 261, 300–322. doi:10.1016/s0076-6879(95)61015-4

Becette, O. B., Zong, G., Chen, B., Taiwo, K. M., Case, D. A., and Dayie, T. K. (2020). Solution NMR readily reveals distinct structural folds and interactions in doubly 13C- and 19F-labeled RNAs. Sci. Adv. 6 (41), eabc6572. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abc6572

Beusch, I., Barraud, P., Moursy, A., Cléry, A., and Allain, F. H. (2017). Tandem hnRNP A1 RNA recognition motifs act in concert to repress the splicing of survival motor neuron exon 7. Elife 6, e25736. doi:10.7554/eLife.25736

Campos-Olivas, R., Aziz, R., Helms, G. L., Evans, J. N., and Gronenborn, A. M. (2002). Placement of 19F into the center of GB1: effects on structure and stability. FEBS Lett. 517 (1-3), 55–60. doi:10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02577-2

Cartegni, L., Hastings, M. L., Calarco, J. A., de Stanchina, E., and Krainer, A. R. (2006). Determinants of exon 7 splicing in the spinal muscular atrophy genes, SMN1 and SMN2. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 78 (1), 63–77. doi:10.1086/498853

Castello, A., Fischer, B., Eichelbaum, K., Horos, R., Beckmann, B. M., Strein, C., et al. (2012). Insights into RNA biology from an atlas of mammalian mRNA-binding proteins. Cell 149 (6), 1393–1406. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.031

Cellitti, S. E., Jones, D. H., Lagpacan, L., Hao, X., Zhang, Q., Hu, H., et al. (2008). In vivo incorporation of unnatural amino acids to probe structure, dynamics, and ligand binding in a large protein by nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130 (29), 9268–9281. doi:10.1021/ja801602q

Cieply, B., and Carstens, R. P. (2015). Functional roles of alternative splicing factors in human disease. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 6 (3), 311–326. doi:10.1002/wrna.1276

Cléry, A., Sinha, R., Anczuków, O., Corrionero, A., Moursy, A., Daubner, G. M., et al. (2013). Isolated pseudo-RNA-recognition motifs of SR proteins can regulate splicing using a noncanonical mode of RNA recognition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 110 (30), E2802–E2811. doi:10.1073/pnas.1303445110

Corley, M., Burns, M. C., and Yeo, G. W. (2020). How RNA-binding proteins interact with RNA: molecules and mechanisms. Mol. Cell 78 (1), 9–29. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2020.03.011

Crowley, P. B., Kyne, C., and Monteith, W. B. (2012). Simple and inexpensive incorporation of 19F-tryptophan for protein NMR spectroscopy. Chem. Commun. (Camb) 48 (86), 10681–10683. doi:10.1039/c2cc35347d

Daubner, G. M., Cléry, A., and Allain, F. H. (2013). RRM-RNA recognition: NMR or crystallography and new findings. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 23 (1), 100–108. doi:10.1016/j.sbi.2012.11.006

Dolbier, W. R. (2009). Guide to fluorine NMR for organic chemists. New Jersey, United States: John Wiley & Sons.

Dominguez, C., Schubert, M., Duss, O., Ravindranathan, S., and Allain, F. H. (2011). Structure determination and dynamics of protein-RNA complexes by NMR spectroscopy. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson Spectrosc. 58 (1-2), 1–61. doi:10.1016/j.pnmrs.2010.10.001

Dujardin, M., Cantrelle, F. X., Lippens, G., and Hanoulle, X. (2018). Interaction study between HCV NS5A-D2 and NS5B using 19F NMR. J. Biomol. NMR 70 (1), 67–76. doi:10.1007/s10858-017-0159-9

Eichler, C., Himmelstoß, M., Plangger, R., Weber, L. I., Hartl, M., Kreutz, C., et al. (2023). Advances in RNA labeling with trifluoromethyl groups. Chemistry 29, e202302220. doi:10.1002/chem.202302220

Eperon, I. C., Makarova, O. V., Mayeda, A., Munroe, S. H., Cáceres, J. F., Hayward, D. G., et al. (2000). Selection of alternative 5' splice sites: role of U1 snRNP and models for the antagonistic effects of SF2/ASF and hnRNP A1. Mol. Cell Biol. 20 (22), 8303–8318. doi:10.1128/mcb.20.22.8303-8318.2000

Fauster, K., Kreutz, C., and Micura, R. (2012). 2'-SCF3 uridine-a powerful label for probing structure and function of RNA by 19F NMR spectroscopy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 51 (52), 13080–13084. doi:10.1002/anie.201207128

Feracci, M., Foot, J. N., Grellscheid, S. N., Danilenko, M., Stehle, R., Gonchar, O., et al. (2016). Structural basis of RNA recognition and dimerization by the STAR proteins T-STAR and Sam68. Nat. Commun. 7, 10355. doi:10.1038/ncomms10355

Furukawa, A., Konuma, T., Yanaka, S., and Sugase, K. (2016). Quantitative analysis of protein-ligand interactions by NMR. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson Spectrosc. 96, 47–57. doi:10.1016/j.pnmrs.2016.02.002

Gronenborn, A. M. (2022). Small, but powerful and attractive: 19F in biomolecular NMR. Structure 30 (1), 6–14. doi:10.1016/j.str.2021.09.009

Higgins, S. J., and Hames, B. D. (1994). RNA processing: a practical approach: v.1 & 2. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Himmelstoss, M., Erharter, K., Renard, E., Ennifar, E., Kreutz, C., and Micura, R. (2020). 2'-O-Trifluoromethylated RNA - a powerful modification for RNA chemistry and NMR spectroscopy. Chem. Sci. 11 (41), 11322–11330. doi:10.1039/d0sc04520a

Jobbins, A. M., Yu, S., Paterson, H. A. B., Maude, H., Kefala-Stavridi, A., Speck, C., et al. (2023). Pre-RNA splicing in metabolic homeostasis and liver disease. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 34 (12), 823–837. doi:10.1016/j.tem.2023.08.007

Kashima, T., and Manley, J. L. (2003). A negative element in SMN2 exon 7 inhibits splicing in spinal muscular atrophy. Nat. Genet. 34 (4), 460–463. doi:10.1038/ng1207

Kelaini, S., Chan, C., Cornelius, V. A., and Margariti, A. (2021). RNA-binding proteins hold key roles in function, dysfunction, and disease. Biol. (Basel) 10 (5), 366. doi:10.3390/biology10050366

Kreutz, C., Kählig, H., Konrat, R., and Micura, R. (2005). Ribose 2'-F labeling: a simple tool for the characterization of RNA secondary structure equilibria by 19F NMR spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127 (33), 11558–11559. doi:10.1021/ja052844u

Li, Q., Chen, J., Trajkovski, M., Zhou, Y., Fan, C., Lu, K., et al. (2020). 4'-Fluorinated RNA: synthesis, structure, and applications as a sensitive 19F NMR probe of RNA structure and function. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142 (10), 4739–4748. doi:10.1021/jacs.9b13207

Luchinat, E., and Banci, L. (2022). In-cell NMR: from target structure and dynamics to drug screening. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 74, 102374. doi:10.1016/j.sbi.2022.102374

Manabile, M. A., Hull, R., Khanyile, R., Molefi, T., Damane, B. P., Mongan, N. P., et al. (2023). Alternative splicing events and their clinical significance in colorectal cancer: targeted therapeutic opportunities. Cancers (Basel) 15 (15), 3999. doi:10.3390/cancers15153999

Maris, C., Dominguez, C., and Allain, F. H. (2005). The RNA recognition motif, a plastic RNA-binding platform to regulate post-transcriptional gene expression. FEBS J. 272 (9), 2118–2131. doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04653.x

Matei, E., and Gronenborn, A. M. (2016). (19)F paramagnetic relaxation enhancement: a valuable tool for distance measurements in proteins. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 55 (1), 150–154. doi:10.1002/anie.201508464

Mehta, M., Raguraman, R., Ramesh, R., and Munshi, A. (2022). RNA binding proteins (RBPs) and their role in DNA damage and radiation response in cancer. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 191, 114569. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2022.114569

Nag, S., Goswami, B., Das Mandal, S., and Ray, P. S. (2022). Cooperation and competition by RNA-binding proteins in cancer. Semin. Cancer Biol. 86 (3), 286–297. doi:10.1016/j.semcancer.2022.02.023

Nicastro, G., Taylor, I. A., and Ramos, A. (2015). KH-RNA interactions: back in the groove. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 30, 63–70. doi:10.1016/j.sbi.2015.01.002

Nikom, D., and Zheng, S. (2023). Alternative splicing in neurodegenerative disease and the promise of RNA therapies. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 24 (8), 457–473. doi:10.1038/s41583-023-00717-6

Nikonowicz, E. P., Sirr, A., Legault, P., Jucker, F. M., Baer, L. M., and Pardi, A. (1992). Preparation of 13C and 15N labelled RNAs for heteronuclear multi-dimensional NMR studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 20 (17), 4507–4513. doi:10.1093/nar/20.17.4507

Nußbaumer, F., Plangger, R., Roeck, M., and Kreutz, C. (2020). Aromatic 19 F-13C TROSY-[19 F, 13C]-Pyrimidine labeling for NMR spectroscopy of RNA. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 59 (39), 17062–17069. doi:10.1002/anie.202006577

Overbeck, J. H., Vögele, J., Nussbaumer, F., Duchardt-Ferner, E., Kreutz, C., Wöhnert, J., et al. (2023). Multi-site conformational exchange in the synthetic neomycin-sensing riboswitch studied by 19F NMR. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 62 (23), e202218064. doi:10.1002/anie.202218064

Pellecchia, M. (2005). Solution nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy techniques for probing intermolecular interactions. Chem. Biol. 12 (9), 961–971. doi:10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.08.013

Prashad, S., and Gopal, P. P. (2021). RNA-binding proteins in neurological development and disease. RNA Biol. 18 (7), 972–987. doi:10.1080/15476286.2020.1809186

Sanya, D. R. A., Cava, C., and Onésime, D. (2023). Roles of RNA-binding proteins in neurological disorders, COVID-19, and cancer. Hum. Cell 36 (2), 493–514. doi:10.1007/s13577-022-00843-w

Scott, L. G., Geierstanger, B. H., Williamson, J. R., and Hennig, M. (2004). Enzymatic synthesis and 19F NMR studies of 2-fluoroadenine-substituted RNA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126 (38), 11776–11777. doi:10.1021/ja047556x

Scott, L. G., and Hennig, M. (2016). ¹⁹F-Site-Specific-Labeled nucleotides for nucleic acid structural analysis by NMR. Methods Enzymol. 566, 59–87. doi:10.1016/bs.mie.2015.05.015

Sharaf, N. G., and Gronenborn, A. M. (2015). (19)F-modified proteins and (19)F-containing ligands as tools in solution NMR studies of protein interactions. Methods Enzymol. 565, 67–95. doi:10.1016/bs.mie.2015.05.014

Sharaf, N. G., Ishima, R., and Gronenborn, A. M. (2016). Conformational plasticity of the NNRTI-binding pocket in HIV-1 reverse transcriptase: a fluorine nuclear magnetic resonance study. Biochemistry 55 (28), 3864–3873. doi:10.1021/acs.biochem.6b00113

Sudakov, A., Knezic, B., Hengesbach, M., Fürtig, B., Stirnal, E., and Schwalbe, H. (2023). Site-specific labeling of RNAs with modified and 19 F-labeled nucleotides by chemo-enzymatic synthesis. Chemistry 29 (25), e202203368. doi:10.1002/chem.202203368

Teilum, K., Kunze, M. B., Erlendsson, S., and Kragelund, B. B. (2017). (S)Pinning down protein interactions by NMR. Protein Sci. 26 (3), 436–451. doi:10.1002/pro.3105

Theillet, F. X., and Luchinat, E. (2022). In-cell NMR: why and how? Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson Spectrosc. 132-133, 1–112. doi:10.1016/j.pnmrs.2022.04.002

Valverde, R., Edwards, L., and Regan, L. (2008). Structure and function of KH domains. FEBS J. 275 (11), 2712–2726. doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06411.x

Wee, C. D., Havens, M. A., Jodelka, F. M., and Hastings, M. L. (2014). Targeting SR proteins improves SMN expression in spinal muscular atrophy cells. PLoS One 9 (12), e115205. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0115205

Welte, H., Sinn, P., and Kovermann, M. (2021). Fluorine NMR spectroscopy enables to quantify the affinity between DNA and proteins in cell lysate. Chembiochem 22 (20), 2973–2980. doi:10.1002/cbic.202100304

Keywords: RNA-protein interaction, 19F NMR spectroscopy, RNA binding proteins, RNA labelling, concurrent/competitive binding

Citation: Kara H, Axer A, Muskett FW, Bueno-Alejo CJ, Paschalis V, Taladriz-Sender A, Tubasum S, Vega MS, Zhao Z, Clark AW, Hudson AJ, Eperon IC, Burley GA and Dominguez C (2024) 2′-19F labelling of ribose in RNAs: a tool to analyse RNA/protein interactions by NMR in physiological conditions. Front. Mol. Biosci. 11:1325041. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2024.1325041

Received: 20 October 2023; Accepted: 30 January 2024;

Published: 14 February 2024.

Edited by:

Pierre Barraud, UMR8261 Expression Génétique Microbienne (EGM), FranceReviewed by:

Bruno Kieffer, Université de Strasbourg, FranceOr Szekely, Duke University, United States

Maja Marušič, National Institute of Chemistry, Slovenia

Copyright © 2024 Kara, Axer, Muskett, Bueno-Alejo, Paschalis, Taladriz-Sender, Tubasum, Vega, Zhao, Clark, Hudson, Eperon, Burley and Dominguez. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ian C. Eperon, ZWNpQGxlLmFjLnVr; Glenn A. Burley, Z2xlbm4uYnVybGV5QHN0cmF0aC5hYy51aw==; Cyril Dominguez, Y2QxODBAbGUuYWMudWs=

Hesna Kara1,2

Hesna Kara1,2 Alexander Axer

Alexander Axer Frederick W. Muskett

Frederick W. Muskett Andrea Taladriz-Sender

Andrea Taladriz-Sender Marina Santana Vega

Marina Santana Vega Zhengyun Zhao

Zhengyun Zhao Ian C. Eperon

Ian C. Eperon Glenn A. Burley

Glenn A. Burley Cyril Dominguez

Cyril Dominguez