- 1Cell Biology Center, Tokyo Institute of Technology, Yokohama, Japan

- 2Department of Applied Bioscience, Kanagawa Institute of Technology, Atsugi, Kanagawa, Japan

Protein folding is often hampered by intermolecular protein aggregation, which can be prevented by a variety of chaperones in the cell. Bacterial chaperonin GroEL is a ring-shaped chaperone that forms complexes with its cochaperonin GroES, creating central cavities to accommodate client proteins (also referred as substrate proteins) for folding. GroEL and GroES (GroE) are the only indispensable chaperones for bacterial viability, except for some species of Mollicutes such as Ureaplasma. To understand the role of chaperonins in the cell, one important goal of GroEL research is to identify a group of obligate GroEL/GroES clients. Recent advances revealed hundreds of in vivo GroE interactors and obligate chaperonin-dependent clients. This review summarizes the progress on the in vivo GroE client repertoire and its features, mainly for Escherichia coli GroE. Finally, we discuss the implications of the GroE clients for the chaperone-mediated buffering of protein folding and their influences on protein evolution.

1 Introduction

Protein functions depend on their tertiary structures, which are dictated by their amino acid sequences, as demonstrated by Christian Anfinsen more than half a century ago (Anfinsen, 1973). Although protein folding is a spontaneous process in principle, folding frequently competes with the side process of aggregate formation, which is repressed by a variety of molecular chaperones (Dobson, 2003; Richter et al., 2010; Balchin et al., 2016). Indeed, a proteome-wide aggregation analysis of thousands of Escherichia coli proteins, using a reconstituted cell-free translation system, found that around 30% of proteins tend to aggregate without chaperones (Niwa et al., 2009), and the majority are saved by conserved chaperones such as the chaperonin GroEL/GroES (GroE) or DnaK/DnaJ/GrpE (DnaK system) (Niwa et al., 2012).

Chaperonins, a subclass of conserved chaperones, are responsible for promoting protein folding in cells (Thirumalai and Lorimer, 2001; Taguchi, 2005, 2015; Hayer-Hartl et al., 2016; Weiss et al., 2016; Thirumalai et al., 2020; Horovitz et al., 2022). The best-characterized chaperonin is E. coli GroE. GroE is a heat shock protein and the only indispensable chaperone for bacterial viability (Fayet et al., 1989), except for some species of Mollicutes such as Ureaplasma and Mycoplasma (Glass et al., 2000; Clark and Tillier, 2010; Schwarz et al., 2018). GroE helps fold numerous client proteins within cells using ATP. ATP binding to the GroEL rings induces drastic conformational changes leading to the formation of GroEL-GroES complexes, which have central cavities for client protein encapsulation (Xu et al., 1997; Kanno et al., 2009; Chen et al., 2013). The encapsulation of client proteins in the chaperonin cavity is essential to the growth of E. coli (Koike-Takeshita et al., 2006). An in vitro analysis revealed that the GroE cavity could accommodate proteins up to ∼60 kDa (Sakikawa et al., 1999). Although this review does not cover the detailed molecular mechanism of GroE, the basic role of GroEL is to bind to non-native monomeric proteins that arise after translation or during heat stress to prevent aggregation, and then promote folding in an ATP- and GroES-dependent manner.

In this review, we summarize the progress on the in vivo client proteins of the chaperonin GroEL and GroES (in vivo GroE clients) and discuss the roles of chaperonins in the cell. Other details on chaperonins have been summarized in recent excellent reviews (Weiss et al., 2016; Balchin et al., 2020; Horovitz et al., 2022).

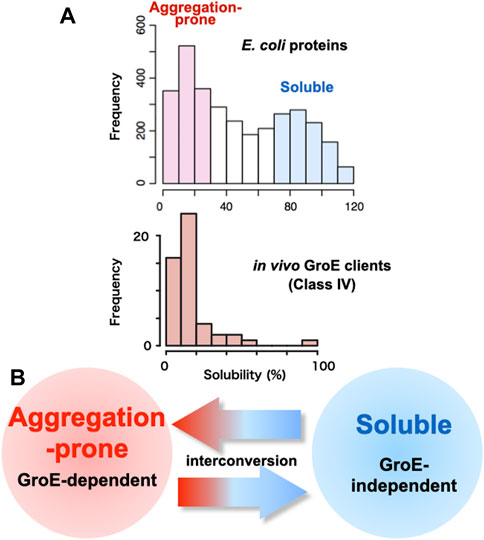

2 Premise of the chaperone requirement: Proteins are aggregation-prone

One of the reasons why chaperones are necessary for the cell is that proteins often aggregate. Indeed, researchers handling proteins know empirically that some proteins tend to form aggregates. What fraction of proteins is aggregation-prone at the proteome level? In this regard, a comprehensive study was conducted in which more than 70% of E. coli proteins, 3,173 proteins, were translated under chaperone-free conditions to determine whether they formed aggregates or were soluble (Niwa et al., 2009). The large-scale analysis using a reconstituted cell-free E. coli translation system (PURE system) revealed that the distribution of solubilities was bimodal, indicating that the E. coli proteome is divided into two groups: Soluble and aggregation-prone (Figure 1A). The analysis also showed that one-third of the proteins were aggregated when translated in the absence of chaperones, supporting the empirical view that proteins are aggregation-prone. A bioinformatics analysis demonstrated that protein solubility correlates better with cellular abundance, rather than gene-expression levels (Castillo et al., 2011). Subsequent analyses with the DnaK system or GroE showed that the addition of the chaperones during the translation of those aggregation-prone proteins alleviated aggregation overall, indicating the necessity of chaperones at the proteome level (Niwa et al., 2012).

FIGURE 1. Relationship between GroE-dependency and protein solubility (A) Histograms of solubility distributions for 3,173 E. coli proteins (Niwa et al., 2009) and obligate GroE-dependent clients (Class IV clients) (Fujiwara et al., 2010). Inherent protein solubilities under chaperone-free conditions were determined by a global aggregation analysis, using a reconstituted cell-free translation system (PURE system). Solubility scores, representing the index of the aggregation propensity, are defined as the proportion of the supernatant fraction, obtained after the centrifugation of the translation mixture, to the uncentrifuged total protein (Niwa et al., 2009). (B) Interconversion of the aggregation-prone propensity and the GroE-dependency.

Aggregation formation is associated with impaired folding. Recent global refolding experiments using an E. coli lysate, combined with mass spectrometry-based proteomics, revealed that one-third of the E. coli proteome is not intrinsically refoldable (To et al., 2021).

As these large-scale studies suggest, a certain fraction of proteins does not fold easily and often aggregates, supporting the notion that chaperones are essential to maintain the protein homeostasis (proteostasis) in the cell.

3 In vivo clients of GroEL-GroES

In E. coli, three major chaperone systems, trigger factor (TF), the DnaK system, and the chaperonin GroE, are considered to contribute to the folding of newly synthesized polypeptides. These three chaperone systems work together in a cooperative manner, with TF and DnaK both playing similar roles during co-translational processes in vivo (Deuerling et al., 1999; Teter et al., 1999; Ferbitz et al., 2004), whereas it is thought that GroEL plays a role in folding polypeptides after they have left the ribosome, although there have also been reports of GroEL potentially being involved in the co-translational process (Genevaux et al., 2004; Vorderwülbecke et al., 2004; Ying et al., 2005, 2006). An important goal in understanding the role of GroE in the cell is to identify in vivo obligate GroE clients that absolutely require GroE for folding in cells. The determination of the obligate GroE clients should clarify GroE’s unique role among chaperones, provide insight into the structural characteristics of the obligate clients, and illuminate the role of GroE in protein evolution.

3.1 Phenotype analyses using GroE-knockdown strains

Since the GroE-deletion E. coli strain is not available, due to the fact that GroE is the only indispensable chaperone for E. coli viability (Fayet et al., 1989; Horwich et al., 1993), a conditional GroE expression strain has been used to identify the in vivo GroE clients by analyzing the phenotype after GroE-depletion (McLennan and Masters, 1998). The depletion of GroE in E. coli has led to the identification of DapA and FtsE as essential clients in the cell lysis and filamentous morphology phenotypes, respectively (McLennan and Masters, 1998; Fujiwara and Taguchi, 2007). Although a detailed phenotypic analysis can precisely identify obligate GroE clients, this approach is limited because it can only identify one client at a time and only in cells with experimentally tractable phenotypes.

GroE depletion in E. coli causes the aggregation or degradation of newly translated polypeptides due to misfolding (e.g., Chapman et al., 2006; Fujiwara et al., 2010; Niwa et al., 2022). The use of mass spectrometry (MS) has identified around 300 proteins in aggregated proteins in a severe temperature-sensitive GroE strain, which harbors the GroEL (E461 K) mutant instead of wild-type GroEL (Chapman et al., 2006).

3.2 In vivo GroEL interactors

Another method to identify in vivo GroE clients is through a proteome-wide analysis of GroE complexes, including client proteins. Hundreds of GroEL interactors have been identified using MS (e.g., Houry et al., 1999; Kerner et al., 2005). In particular, Kerner et al. identified ∼250 E. coli proteins that are encapsulated in a chaperonin complex between E. coli GroEL and Methanosarcina mazei GroES, which tightly binds E. coli GroEL (Kerner et al., 2005). The interactors were categorized into three classes depending on their enrichment in the GroEL-GroES complex: Class I clients as spontaneous folders, Class II as partial GroEL-dependent clients, and Class III as potential obligate GroE clients (Kerner et al., 2005).

Note that other approaches to identify in vivo GroEL interactors have been applied to other bacteria besides E. coli. In Thermus thermophilus, MS-based proteomics of the endogenous T. thermophilus GroEL-GroES complex identified 24 clients in the chaperonin cavity (Shimamura et al., 2004). In Bacillus subtilis, a single-ring GroEL variant with a histidine-tag was used to identify 28 GroEL interactors (Endo and Kurusu, 2007). The archaeon M. mazei has the unusual property of possessing a group I chaperonin (GroEL) in addition to a group II chaperonin (Figueiredo et al., 2004). In this archaeon, Methanosarcina GroEL interactors have been identified by a large-scale co-immunoprecipitation analysis (Hirtreiter et al., 2009).

3.3 In vivo obligate GroE-dependent clients

An analysis of E. coli chaperonin GroEL interactors at the proteome level identified a group of proteins referred to as Class III clients, which were thought to be obligate chaperonin clients. However, the necessity of chaperonins for in vivo folding has not been thoroughly examined. In fact, one of the Class III proteins, ParC, was functional even under GroE-depleted conditions (Fujiwara and Taguchi, 2007), raising the possibility that the predicted Class III proteins are not necessarily obligate clients of GroE. A systematic assessment of the GroE requirement under the GroE-depleted condition revealed that ∼60% of the Class III clients required GroE for proper folding, and thus were regarded as bona fide obligate GroE clients in vivo and reclassified as Class IV clients (Fujiwara et al., 2010). Besides the Class III clients, a metabolomics analysis and the Class IV homologs in E. coli were used to identify additional Class IV clients (Fujiwara et al., 2010). In the metabolomics analysis, if the level of a metabolite is altered in a GroE-deficient strain, then the enzymes involved with the metabolite may be GroEL clients (Fujiwara et al., 2010). Furthermore, with the aid of data from the in vitro comprehensive analysis using the PURE system, 20 additional Class IV clients were identified (Niwa et al., 2016). In total, about 80 proteins have now been identified as Class IV clients.

It is worthwhile to compare these Class IV clients with other client candidate lists identified by various approaches or in other bacteria. Regarding the ∼300 proteins aggregated in the GroEL (E461 K) mutant strain, identified by Chapman et al. (Chapman et al., 2006), only 17 proteins were overlapped with Class IV clients (Fujiwara et al., 2010). The poor overlapping of the clients in these studies would be due to the different approaches used. Indeed, Masters et al. observed that insoluble proteins did not accumulate in GroE-depleted MGM100 cells (Masters et al., 2009), suggesting that the cellular milieus in the GroEL mutant strain and the GroE-depleted cells are quite different. Comparisons of Class IV clients in E. coli with GroE interactors in T. thermophilus and B. subtilis (Shimamura et al., 2004; Endo and Kurusu, 2007) revealed no apparent overlap, probably due to the fact that MS-based proteomics was in its initial stages in the early 2000s and the number of identified proteins was extremely small.

Collectively, the term “client” can vary significantly depending on the context in which it is utilized. The most commonly employed method for identifying chaperone client candidates is through the utilization of in vivo interactors obtained via pull-down assays. However, in the case of GroE, additional validation is necessary as GroE-interactors such as Class III proteins do not necessarily require GroE for in vivo folding. To qualify as a bona fide GroE client, folding in a GroE-depleted strain should be examined. Furthermore, in vitro experiments could provide greater insight into whether the folding of candidate clients can be aided by GroE during translation or after denaturation. In reality, however, determining whether a protein has completed folding correctly in vitro can be challenging. For enzymes, it is possible to assess folding completion through enzymatic activity, however, this activity-based approach is not universally applicable to all potential clients.

3.4 Features of the in vivo obligate GroE clients

The identification of the Class IV clients revealed several of their features, as follows (Fujiwara et al., 2010).

3.4.1 Aggregation-prone properties

The most striking feature of the Class IV clients is their inherent highly aggregation-prone nature (Fujiwara et al., 2010) (Figure 1A), which was evaluated by a global aggregation analysis under chaperone-free conditions using a reconstituted E. coli cell-free translation system (PURE system) (Niwa et al., 2009).

3.4.2 Molecular weights and amino acid preferences

As with other features, the Class IV clients, which are limited to those with molecular weights less than approximately 70 kD and can fit within the chaperonin cavity, exhibit a weak yet significant enrichment in alanine/glycine residues. On average, the Ala/Gly enrichment corresponded to six additional alanine or glycine residues in a 300 amino acid protein (Fujiwara et al., 2010).

3.4.3 Structural preferences

A bioinformatic analysis revealed specific structural tendencies among the Class IV clients, with nearly half (25/57) of them displaying the TIM-barrel fold (c.1 in SCOP database terminology), which has been proposed as the preferred folding topology for GroE interactors (Houry et al., 1999; Kerner et al., 2005). Other fold classes, such as the FAD/NAD(P)-binding domain (c.3), the PLP-dependent transferase-like fold (c.67), and the thiolase fold (c.95), were also overrepresented in Class IV, but to a lesser extent than the TIM-barrel fold proteins. Strikingly, all of the fold classes overrepresented among the Class IV members are aggregation-prone folds, as characterized in the global aggregation assay under chaperone-free conditions (Niwa et al., 2009).

3.4.4 Functional preferences

Approximately 70% of Class IV clients are metabolic enzymes, with six of them (DapA, ASD, MetK, FtsE, HemB, and KdsA) being essential for the viability of E. coli (Fujiwara et al., 2010). If these are the only essential clients of GroE, creating an E. coli strain that is not dependent on GroE should be possible by complementing these six genes; e.g., the conversion of GroE-dependency (Masters et al., 2009; Fujiwara et al., 2010). A viable groE-knockout E. coli strain would provide an answer to the question of why GroE is essential for cell viability.

4 Determinants that define the chaperonin GroEL dependency

After the in vivo obligate GroE clients have been identified, the next challenge is to distinguish the determinants that define such GroE dependence. Although these determinants are not yet fully understood, some attempts are introduced here.

4.1 Factors associated with GroE dependency

Several attempts have been made to distinguish GroE clients from other proteins, by bioinformatics and experimental approaches (Masters et al., 2009; Tartaglia et al., 2010; Azia et al., 2012). The identification of in vivo obligate GroE clients raises the question about the key factors that define the GroE dependency. So far, various approaches have been used to extract the characteristics of the GroE clients. Although they were not sufficient to enable the development of a highly accurate predictor, the following are some factors that are associated with GroE clients. At the amino acid sequence level, bioinformatic approaches were conducted to identify “binding motifs” of GroE clients using sequence patterns similar to the GroES mobile loop segment that binds GroEL (Chaudhuri and Gupta, 2005; Stan et al., 2005). Many other indicators have been proposed as features of GroE clients. The studies that used GFP as an artificial GroE client revealed that highly frustrated regions, wherein not all interactions in the native state are optimized energetically, and increased contact order in the client are associated with greater GroE dependence (Bandyopadhyay et al., 2017, 2019). Also, we note that the features that identify the GroE dependency of a given protein do not necessarily translate broadly to in vivo clients. For example, contact order did not distinguish in vivo clients from other E. coli proteins (Noivirt-Brik et al., 2007).

4.2 Converting the GroE dependency of a protein

One way to explore the factors that determine GroE dependence is to convert a protein that is not a GroE client into a GroE client. The Class IV orthologs (MetK, DeoA and YcfH) in the GroE-lacking organism Ureaplasma urealyticum fold into the native state in GroE-depleted E. coli cells (Fujiwara et al., 2010; Georgescauld et al., 2014). Among them, the MetK ortholog in Ureaplasma urealyticum (UuMetK), which shares 45% identity with E. coli MetK (EcMetK), has been investigated to decode the determinants for the GroE requirement (Ishimoto et al., 2014). UuMetK does not require GroE during the folding process in E. coli (Fujiwara et al., 2010; Fujiwara and Taguchi, 2012). Analyses of chimeric or randomly mutagenized UuMetK genes expressed in GroE-depleted E. coli revealed that multiple independent point mutations or even single mutations were sufficient to change from the GroE-independent UuMetK to the GroE-dependent UuMetK, suggesting that subtle differences determine the GroE-dependency. The locations of the mutations in UuMetK were spread out throughout the open reading frame. Notably, the GroE-dependency was well correlated with the tendency of the mutant proteins to form protein aggregates during folding (Ishimoto et al., 2014). Combined with the recent finding that point mutations can convert an aggregation-prone GroE client into a GroE-independent folder (Taguchi et al. unpublished), the differences between GroE clients and non-GroE clients would be subtle, suggesting that they could be interconvertible (Figure 1B).

5 Implications in protein evolution: GroE might be required for “newcomer” proteins

The identification of the obligate GroE clients revealed that more than 70% (42 out of 57) are likely to be involved in metabolic reactions. What is the relationship between GroE and metabolic enzymes? A bioinformatics analysis of the metabolic pathways revealed that, as the GroE dependency increases, the clients are more laterally distributed in the metabolic network (Takemoto et al., 2011). In addition, a comparative genome analysis showed that the degree of conservation of GroE clients decreases with the GroE dependence, and the Class I GroE clients are most conserved as compared to other GroE client classes (Takemoto et al., 2011).

These findings could be discussed in the context of protein evolution. Most protein mutations have a negative effect since the protein stability is, in general, marginal (Tokuriki et al., 2008). It has been proposed that chaperones play a role in facilitating protein evolution by buffering the destabilizing mutations that cause misfolding (Rutherford and Lindquist, 1998). This concept, which was originally developed from studies on Hsp90 (Rutherford and Lindquist, 1998), has been extended to GroE (Fares et al., 2002; Tokuriki and Tawfik, 2009; Bogumil and Dagan, 2012). Directed evolution experiments revealed that GroE overexpression could buffer the destabilizing mutations, thereby promoting the folding of compromised proteins to improve their enzyme activities (Tokuriki and Tawfik, 2009; Wyganowski et al., 2013). Indeed, the evolved enzymes in GroE-overexpressing E. coli gained aggregation-prone properties and were converted to GroE-dependent proteins (Tokuriki and Tawfik, 2009), consistent with the MetK case described above (Ishimoto et al., 2014). Therefore, the role of GroE in buffering the aggregation-prone mutations helps the destabilized proteins to function in the cellular environment. The buffering effect would allow the destabilized proteins to exhibit novel cellular functions in a chaperone-dependent manner, eventually contributing to the molecular evolution of the protein (Takemoto et al., 2011).

The possible evolutional role of GroE prompted us to investigate whether GroE clients are conserved among species. If the obligate GroE clients (Class IV) have evolutionarily acquired some function or other traits more recently by mutations of existing proteins than other proteome members, then we would expect that the GroE clients are not conserved. So far, an extensive survey to identify in vivo obligate GroE-dependent clients has only been conducted in E. coli. For verification, we await a study to identify the in vivo clients in other bacteria, at the level of that in E. coli.

6 Future perspectives

Even though there have been great breakthroughs in highly accurate protein structure prediction, as represented by AlphaFold2 (Jumper et al., 2021) and rational de novo protein design (Huang et al., 2016), we still do not fully understand the protein folding process. One of the obstacles is protein aggregation. Protein aggregation is a notorious problem when handling proteins and has often been ignored as an unwanted side reaction in protein folding. The chaperone studies unveiled the previously unrecognized role of aggregation-prone proteins in the protein world. Since Anfinsen demonstrated the basic principle of protein folding (Anfinsen, 1973), extensive efforts to elucidate the protein folding mechanism have been performed for more than half a century (Dill and MacCallum, 2012). However, the “folding” mechanisms of “recalcitrant” proteins, which are not spontaneously folded under chaperone-free conditions, remain enigmatic. Most physicochemical methods such as stopped-flow kinetic experiments and calorimetric measurements are not amenable to aggregated proteins. Approaches to tackle the “folding” mechanisms of recalcitrant proteins are necessary to understand the wide spectrum of protein folding in the cell.

Author contributions

HT and AK-T Conceived the review. HT finalized the review.

Funding

This work was supported by MEXT Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (Grant Numbers JP26116002, JP18H03984, JP20H05925 to HT).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Anfinsen, B. C. (1973). Principles that govern the folding of protein chains. Science 181, 223–230. doi:10.1126/science.181.4096.223

Azia, A., Unger, R., and Horovitz, A. (2012). What distinguishes GroEL substrates from other Escherichia coli proteins? FEBS J. 279, 543–550. doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08458.x

Balchin, D., Hayer-Hartl, M., and Hartl, F. U. (2016). In vivo aspects of protein folding and quality control. Science 353, aac4354. doi:10.1126/science.aac4354

Balchin, D., Hayer-Hartl, M., and Hartl, F. U. (2020). Recent advances in understanding catalysis of protein folding by molecular chaperones. FEBS Lett. 594, 2770–2781. doi:10.1002/1873-3468.13844

Bandyopadhyay, B., Goldenzweig, A., Unger, T., Adato, O., Fleishman, S. J., Unger, R., et al. (2017). Local energetic frustration affects the dependence of green fluorescent protein folding on the chaperonin GroEL. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 20583–20591. doi:10.1074/jbc.M117.808576

Bandyopadhyay, B., Mondal, T., Unger, R., and Horovitz, A. (2019). Contact order is a determinant for the dependence of GFP folding on the chaperonin GroEL. Biophys. J. 116, 42–48. doi:10.1016/J.BPJ.2018.11.019

Bogumil, D., and Dagan, T. (2012). Cumulative impact of chaperone-mediated folding on genome evolution. Biochemistry 51, 9941–9953. doi:10.1021/bi3013643

Castillo, V., Graña-Montes, R., and Ventura, S. (2011). The aggregation properties of Escherichia coli proteins associated with their cellular abundance. Biotechnol. J. 6, 752–760. doi:10.1002/biot.201100014

Chapman, E., Farr, G. W., Usaite, R., Furtak, K., Fenton, W. A., Chaudhuri, T. K., et al. (2006). Global aggregation of newly translated proteins in an Escherichia coli strain deficient of the chaperonin GroEL. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103, 15800–15805. doi:10.1073/pnas.0607534103

Chaudhuri, T. K., and Gupta, P. (2005). Factors governing the substrate recognition by GroEL chaperone: A sequence correlation approach. Cell Stress Chaperones 10, 24–36. doi:10.1379/CSC-64R1.1

Chen, D. H., Madan, D., Weaver, J., Lin, Z., Schröder, G. F., Chiu, W., et al. (2013). Visualizing GroEL/ES in the act of encapsulating a folding protein. Cell 153, 1354–1365. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.052

Clark, G. W., and Tillier, E. R. M. (2010). Loss and gain of GroEL in the mollicutes. Biochem. Cell Biol. 88, 185–194. doi:10.1139/O09-157

Deuerling, E., Schulze-Specking, A., Tomoyasu, T., Mogk, A., Bukau, B., and Mogk, A. (1999). Trigger factor and DnaK cooperate in folding of newly synthesized proteins. Nature 400, 693–696. doi:10.1038/23301

Dill, K. A., and MacCallum, J. L. (2012). The protein-folding problem, 50 years on. Science 338, 1042–1046. doi:10.1126/science.1219021

Endo, A., and Kurusu, Y. (2007). Identification of in vivo substrates of the chaperonin GroEL from Bacillus subtilis. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 71, 1073–1077. doi:10.1271/bbb.60640

Fares, M. A., Ruiz-González, M. X., Moya, A., Elena, S. F., and Barrio, E. (2002). Endosymbiotic bacteria: GroEL buffers against deleterious mutations. Nature 417, 398. doi:10.1038/417398a

Fayet, O., Ziegelhoffer, T., and Georgopoulos, C. (1989). The groES and groEL heat shock gene products of Escherichia coli are essential for bacterial growth at all temperatures. J. Bacteriol. 171, 1379–1385. doi:10.1128/jb.171.3.1379-1385.1989

Ferbitz, L., Maier, T., Patzelt, H., Bukau, B., Deuerling, E., and Ban, N. (2004). Trigger factor in complex with the ribosome forms a molecular cradle for nascent proteins. Nature 431, 590–596. doi:10.1038/nature02899

Figueiredo, L., Klunker, D., Ang, D., Naylor, D. J., Kerner, M. J., Georgopoulos, C., et al. (2004). Functional characterization of an archaeal GroEL/GroES chaperonin system: Significance of substrate encapsulation. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 1090–1099. doi:10.1074/jbc.M310914200

Fujiwara, K., Ishihama, Y., Nakahigashi, K., Soga, T., and Taguchi, H. (2010). A systematic survey of in vivo obligate chaperonin-dependent substrates. EMBO J. 29, 1552–1564. doi:10.1038/emboj.2010.52

Fujiwara, K., and Taguchi, H. (2007). Filamentous morphology in GroE-depleted Escherichia coli induced by impaired folding of FtsE. J. Bacteriol. 189, 5860–5866. doi:10.1128/JB.00493-07

Fujiwara, K., and Taguchi, H. (2012). Mechanism of methionine synthase overexpression in chaperonin-depleted Escherichia coli. Microbiol. (N Y) 158, 917–924. doi:10.1099/mic.0.055079-0

Genevaux, P., Keppel, F., Schwager, F., Langendijk-Genevaux, P. S., Hartl, F. U., and Georgopoulos, C. (2004). In vivo analysis of the overlapping functions of DnaK and trigger factor. EMBO Rep. 5, 195–200. doi:10.1038/sj.embor.7400067

Georgescauld, F., Popova, K., Gupta, A. J., Bracher, A., Engen, J. R., Hayer-Hartl, M., et al. (2014). GroEL/ES chaperonin modulates the mechanism and accelerates the rate of TIM-barrel domain folding. Cell 157, 922–934. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.038

Glass, J. I., Lefkowitz, E. J., Glass, J. S., Heiner, C. R., Chen, E. Y., and Cassell, G. H. (2000). The complete sequence of the mucosal pathogen Ureaplasma urealyticum. Nature 407, 757–762. doi:10.1038/35037619

Hayer-Hartl, M., Bracher, A., and Hartl, F. U. (2016). The GroEL-GroES chaperonin machine: A nano-cage for protein folding. Trends Biochem. Sci. 41, 62–76. doi:10.1016/j.tibs.2015.07.009

Hirtreiter, A. M., Calloni, G., Forner, F., Scheibe, B., Puype, M., Vandekerckhove, J., et al. (2009). Differential substrate specificity of group I and group II chaperonins in the archaeon Methanosarcina mazei. Mol. Microbiol. 74, 1152–1168. doi:10.1111/J.1365-2958.2009.06924.X

Horovitz, A., Reingewertz, T. H., Cuéllar, J., and Valpuesta, J. M. (2022). Chaperonin mechanisms: Multiple and (Mis)Understood? Annu. Rev. Biophys. 51, 115–133. doi:10.1146/annurev-biophys-082521-113418

Horwich, A. L., Low, K. B., Fenton, W. A., Hirshfield, I. N., and Furtak, K. (1993). Folding in vivo of bacterial cytoplasmic proteins: Role of GroEL. Cell 74, 909–917. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(93)90470-B

Houry, W. A., Frishman, D., Eckerskorn, C., Lottspeich, F., and Hartl, F. U. (1999). Identification of in vivo substrates of the chaperonin GroEL. Nature 402, 147–154. doi:10.1038/45977

Huang, P. S., Boyken, S. E., and Baker, D. (2016). The coming of age of de novo protein design. Nature 537, 320–327. doi:10.1038/nature19946

Ishimoto, T., Fujiwara, K., Niwa, T., and Taguchi, H. (2014). Conversion of a chaperonin GroEL-independent protein into an obligate substrate. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 32073–32080. doi:10.1074/jbc.M114.610444

Jumper, J., Evans, R., Pritzel, A., Green, T., Figurnov, M., Ronneberger, O., et al. (2021). Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 596, 583–589. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03819-2

Kanno, R., Koike-Takeshita, A., Yokoyama, K., Taguchi, H., and Mitsuoka, K. (2009). Cryo-EM structure of the native GroEL-GroES complex from thermus thermophilus encapsulating substrate inside the cavity. Structure 17, 287–293. doi:10.1016/j.str.2008.12.012

Kerner, M. J., Naylor, D. J., Ishihama, Y., Maier, T., Chang, H. C., Stines, A. P., et al. (2005). Proteome-wide analysis of chaperonin-dependent protein folding in Escherichia coli. Cell 122, 209–220. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.028

Koike-Takeshita, A., Shimamura, T., Yokoyama, K., Yoshida, M., and Taguchi, H. (2006). Leu309 plays a critical role in the encapsulation of substrate protein into the internal cavity of GroEL. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 962–967. doi:10.1074/jbc.M506298200

Masters, M., Blakely, G., Coulson, A., McLennan, N., Yerko, V., and Acord, J. (2009). Protein folding in Escherichia coli: The chaperonin GroE and its substrates. Res. Microbiol. 160, 267–277. doi:10.1016/j.resmic.2009.04.002

McLennan, N., and Masters, M. (1998). GroE is vital for cell-wall synthesis. Nature 392, 139. doi:10.1038/32317

Niwa, T., Chadani, Y., and Taguchi, H. (2022). Shotgun proteomics revealed preferential degradation of misfolded in vivo obligate GroE substrates by lon protease in Escherichia coli. Molecules 27, 3772. doi:10.3390/molecules27123772

Niwa, T., Fujiwara, K., and Taguchi, H. (2016). Identification of novel in vivo obligate GroEL/ES substrates based on data from a cell-free proteomics approach. FEBS Lett. 590, 251–257. doi:10.1002/1873-3468.12036

Niwa, T., Kanamori, T., Ueda, T., and Taguchi, H. (2012). Global analysis of chaperone effects using a reconstituted cell-free translation system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109, 8937–8942. doi:10.1073/pnas.1201380109

Niwa, T., Ying, B.-W., Saito, K., Jin, W., Takada, S., Ueda, T., et al. (2009). Bimodal protein solubility distribution revealed by an aggregation analysis of the entire ensemble of Escherichia coli proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106, 4201–4206. doi:10.1073/pnas.0811922106

Noivirt-Brik, O., Unger, R., and Horovitz, A. (2007). Low folding propensity and high translation efficiency distinguish in vivo substrates of GroEL from other Escherichia coli proteins. Bioinformatics 23, 3276–3279. doi:10.1093/BIOINFORMATICS/BTM513

Richter, K., Haslbeck, M., and Buchner, J. (2010). The heat shock response: Life on the verge of death. Mol. Cell 40, 253–266. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2010.10.006

Rutherford, S. L., and Lindquist, S. (1998). Hsp90 as a capacitor for morphological evolution. Nature 396, 336–342. doi:10.1038/24550

Sakikawa, C., Taguchi, H., Makino, Y., and Yoshida, M. (1999). On the maximum size of proteins to stay and fold in the cavity of GroEL underneath GroES. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 21251–21256. doi:10.1074/jbc.274.30.21251

Schwarz, D., Adato, O., Horovitz, A., and Unger, R. (2018). Comparative genomic analysis of mollicutes with and without a chaperonin system. PLoS One 13, e0192619. doi:10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0192619

Shimamura, T., Koike-Takeshita, A., Yokoyama, K., Masui, R., Murai, N., Yoshida, M., et al. (2004). Crystal structure of the native chaperonin complex from Thermus thermophilus revealed unexpected asymmetry at the cis-cavity. Structure 12, 1471–1480. doi:10.1016/j.str.2004.05.020

Stan, G., Brooks, B. R., Lorimer, G. H., and Thirumalai, D. (2005). Identifying natural substrates for chaperonins using a sequence-based approach. Protein Sci. 14, 193–201. doi:10.1110/PS.04933205

Taguchi, H. (2005). Chaperonin GroEL meets the substrate protein as a “load” of the rings. J. Biochem. 137, 543–549. doi:10.1093/jb/mvi069

Taguchi, H. (2015). Reaction cycle of chaperonin GroEL via symmetric “football” intermediate. J. Mol. Biol. 427, 2912–2918. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2015.04.007

Takemoto, K., Niwa, T., and Taguchi, H. (2011). Difference in the distribution pattern of substrate enzymes in the metabolic network of Escherichia coli, according to chaperonin requirement. BMC Syst. Biol. 5, 98. doi:10.1186/1752-0509-5-98

Tartaglia, G. G., Dobson, C. M., Hartl, F. U., and Vendruscolo, M. (2010). Physicochemical determinants of chaperone requirements. J. Mol. Biol. 400, 579–588. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2010.03.066

Teter, S. A., Houry, W. A., Ang, D., Tradler, T., Rockabrand, D., Fischer, G., et al. (1999). Polypeptide flux through bacterial Hsp70: DnaK cooperates with trigger factor in chaperoning nascent chains. Cell 97, 755–765. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80787-4

Thirumalai, D., and Lorimer, G. H. (2001). Chaperonin-mediated protein folding. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 30, 245–269. doi:10.1146/annurev.biophys.30.1.245

Thirumalai, D., Lorimer, G. H., and Hyeon, C. (2020). Iterative annealing mechanism explains the functions of the GroEL and RNA chaperones. Protein Sci. 29, 360–377. doi:10.1002/pro.3795

To, P., Whitehead, B., Tarbox, H. E., and Fried, S. D. (2021). Nonrefoldability is pervasive across the E. coli proteome. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 11435–11448. doi:10.1021/JACS.1C03270

Tokuriki, N., Stricher, F., Serrano, L., and Tawfik, D. S. (2008). How protein stability and new functions trade off. PLoS Comput. Biol. 4, e1000002. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000002

Tokuriki, N., and Tawfik, D. S. (2009). Chaperonin overexpression promotes genetic variation and enzyme evolution. Nature 459, 668–673. doi:10.1038/nature08009

Vorderwülbecke, S., Kramer, G., Merz, F., Kurz, T. A., Rauch, T., Zachmann-Brand, B., et al. (2004). Low temperature or GroEL/ES overproduction permits growth of Escherichia coli cells lacking trigger factor and DnaK. FEBS Lett. 559, 181–187. doi:10.1016/S0014-5793(04)00052-3

Weiss, C., Jebara, F., Nisemblat, S., and Azem, A. (2016). Dynamic complexes in the chaperonin-mediated protein folding cycle. Front. Mol. Biosci. 3, 80. doi:10.3389/FMOLB.2016.00080

Wyganowski, K. T., Kaltenbach, M., and Tokuriki, N. (2013). GroEL/ES buffering and compensatory mutations promote protein evolution by stabilizing folding intermediates. J. Mol. Biol. 425, 3403–3414. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2013.06.028

Xu, Z., Horwich, A. L., and Sigler, P. B. (1997). The crystal structure of the asymmetric GroEL-GroES-(ADP)7 chaperonin complex. Nature 388, 741–750. doi:10.1038/41944

Ying, B. W., Taguchi, H., Kondo, M., and Ueda, T. (2005). Co-translational involvement of the chaperonin GroEL in the folding of newly translated polypeptides. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 12035–12040. doi:10.1074/jbc.M500364200

Keywords: chaperonin, GroEL and GroES, protein aggregation, chaperone, chaperone clients

Citation: Taguchi H and Koike-Takeshita A (2023) In vivo client proteins of the chaperonin GroEL-GroES provide insight into the role of chaperones in protein evolution. Front. Mol. Biosci. 10:1091677. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2023.1091677

Received: 07 November 2022; Accepted: 30 January 2023;

Published: 10 February 2023.

Edited by:

Amnon Horovitz, Weizmann Institute of Science, IsraelReviewed by:

George Stan, University of Cincinnati, United StatesPeter Adrian Lund, University of Birmingham, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2023 Taguchi and Koike-Takeshita. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hideki Taguchi, dGFndWNoaUBiaW8udGl0ZWNoLmFjLmpw

Hideki Taguchi

Hideki Taguchi Ayumi Koike-Takeshita

Ayumi Koike-Takeshita