94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Mol. Biosci., 29 June 2022

Sec. Protein Biochemistry for Basic and Applied Sciences

Volume 9 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmolb.2022.907439

This article is part of the Research TopicCarbohydrate-Active Enzymes and Their Inhibitors - Volume IIView all 4 articles

Melanie Baudrexl1

Melanie Baudrexl1 Tarik Fida1†

Tarik Fida1† Berkay Berk1

Berkay Berk1 Wolfgang H. Schwarz1†

Wolfgang H. Schwarz1† Vladimir V. Zverlov1,2‡

Vladimir V. Zverlov1,2‡ Michael Groll3

Michael Groll3 Wolfgang Liebl1*

Wolfgang Liebl1*Functional, biochemical, and preliminary structural properties are reported for three glycoside hydrolases of the recently described glycoside hydrolase (GH) family 159. The genes were cloned from the genomic sequences of different Caldicellulosiruptor strains. This study extends the spectrum of functions of GH159 enzymes. The only activity previously reported for GH159 was hydrolytic activity on β-galactofuranosides. Activity screening using a set of para-nitrophenyl (pNP) glycosides suggested additional arabinosidase activity on substrates with arabinosyl residues, which has not been previously reported for members of GH159. Even though the thermophilic enzymes investigated—Cs_Gaf159A, Ch_Gaf159A, and Ck_Gaf159A—cleaved pNP-α-l-arabinofuranoside, they were only weakly active on arabinogalactan, and they did not cleave arabinose from arabinan, arabinoxylan, or gum arabic. However, the enzymes were able to hydrolyze the α-1,3-linkage in different arabinoxylan-derived oligosaccharides (AXOS) with arabinosylated xylose at the non-reducing end (A3X, A2,3XX), suggesting their role in the intracellular hydrolysis of oligosaccharides. Crystallization and structural analysis of the apo form of one of the Caldicellulosiruptor enzymes, Ch_Gaf159A, enabled the elucidation of the first 3D structure of a GH159 member. This work revealed a five-bladed β-propeller structure for GH159 enzymes. The 3D structure and its substrate-binding pocket also provides an explanation at the molecular level for the observed exo-activity of the enzyme. Furthermore, the structural data enabled the prediction of the catalytic amino acids. This was supported by the complete inactivation by mutation of residues D19, D142, and E190 of Ch_Gaf159A.

Carbohydrates are the most common and, due to their structural heterogeneity, one of the most diverse classes of biopolymers (Pauly and Keegstra 2008). Their hydrolysis depends on the simultaneous presence of a wide range of different enzymatic activities. These Carbohydrate Active Enzymes (CAZymes) are, like their substrates, incredibly diverse. At the same time, each enzyme is highly specific for both the type of sugar bound and its glycosidic bond. This is also reflected in the large number of sequences in the CAZy database (Lombard et al., 2014), which classifies these enzymes, according to sequence similarities and conformity of 3D structure, into clans and families. Currently 18 GH clans of related GH families and seven different folding types can be distinguished, among which are mainly barrel-formed 3D structures (http://www.cazy.org/Glycoside-Hydrolases.html). Small variations in the catalytic center of an enzyme can cause a different substrate specificity, which is why most glycoside hydrolase (GH) families contain enzymes with different catalytic functions. In contrast, the Enzyme Commission (E.C.) number indicates which chemical reaction is catalyzed by an enzyme, irrespective of the enzyme’s structure. Accordingly, enzymes with two different activities are assigned two E.C. numbers.

Helbert et al. (2019) experimentally confirmed β-d-galactofuranosidase (EC 3.2.1.146; Gaf) activity for BcellWH2_02356 (ALJ59596.1) from Bacteroides cellulosilyticus WH2 using heterologously produced enzyme and the artificial substrate para-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactofuranoside (pNPG), whereas oligo- or polysaccharides have not been tested as substrates. Due to the lack of similarity to previously described GH families, this enzyme became the founding member of the new GH family GH159. Since 2019, some formerly unclassified glycoside hydrolase (GHnc) sequences have been assigned to GH159 on the basis of amino acid sequence similarities, including putative enzymes encoded on the genomes of different Caldicellulosiruptor strains. The members of the genus Caldicellulosiruptor are extremely thermophilic, cellulolytic, and non-spore-forming flagellated strict anaerobes with Gram-positive type cell walls, and are capable of fermenting a wide spectrum of carbohydrates. Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus was isolated from wood in the flow from a geothermal spring in New Zealand and has a growth range of between 45°C and 80°C at pH 5.5 to 8.0 (optimum at 70°C and pH 7.0) (Rainey et al., 1994). Caldicellulosiruptor hydrothermalis grows between 50 and 80°C at pH 6.0 to 8.0 with optimum growth at 65°C and pH 7.0. The same growth properties were found for Caldicellulosiruptor kronotskyensis, but the temperature range (45–82°C) is broader and the optimum higher (70°C) (Miroshnichenko et al., 2008).

In this study, the hitherto uncharacterized ORFs encoding three GH159 enzymes, Cs_Gaf159A, Ch_Gaf159A, and Ck_Gaf159A with similar sequences were cloned from the three aforementioned Caldicellulosiruptor species C. saccharolyticus, C. hydrothermalis and C. kronotskyensis with the aim of biochemically characterizing the heterologously expressed enzymes with regard to substrate specificity, temperature and pH dependence of activity, their stability at elevated temperatures, the effects of metal ions, and inhibition by products. In order to characterize the substrate binding and catalytic mechanism of enzymes in more detail at the molecular level from the previously (poorly) studied GH159 family, for which no three-dimensional structures were available, we also sought to elucidate the 3D structure of one of the enzymes by means of crystallography.

Caldicellulosiruptor strains C. saccharolyticus DSM 8903, C. hydrothermalis 108 (DSMZ 18901), and C. kronotskyensis 2002 (DSMZ 18902) were grown anaerobically, and genomic DNA was isolated in order to amplify the sequences of the genes with locus tags Csac_0437 (ABP6075.1), Calhy_0274 (ADQ06027.1) and Calkro_0290 (ADQ45201), respectively.

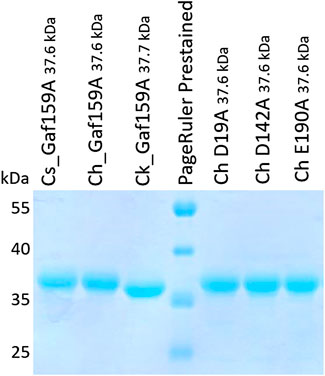

After cloning in expression vector pET24c(+), the expected constructs were verified by sequencing. Expression in E. coli BL21 Star and the subsequent purification resulted in sufficient amounts of the proteins for further study. Separation by SDS-PAGE showed bands corresponding to the expected molecular weights including the His6-tags (Cs_Gaf159A: 37.6 kDa; Ch_Gaf159A: 37.6 kDa; Ck_Gaf159A: 37.7 kDa) for all enzyme preparations used in this study (Figure 1). A high degree of purity as judged from SDS-PAGE was achieved by means of immobilized metal affinity chromatography. Heat treatment of crude extracts from the recombinant E. coli strains at 55°C for depletion of host proteins did not result in a much higher purity, although only small amounts of the respective enzymes precipitated (Supplementary Figure S1).

FIGURE 1. SDS-PAGE analysis of recombinantly produced wildtype and mutant enzymes. Protein samples (0.5 µg μl−1) were mixed with 4 x SDS-loading buffer (0.25 M Tris, 40% w/v glycerol, 0.29 M SDS, 0,57 β-mercaptoethanol, 0.02% bromophenol blue, HCl to pH 6.8), 10 µl were loaded into each lane. Size markers were applied as PageRuler™ Prestained Protein Ladder, 10–180 kDa.

Activity assays with para-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactofuranoside (pNPG), pNP-α-l-arabinofuranoside (pNPA), pNP-α-d-galactopyranoside, pNP-α-l-fucopyranoside, pNP-β-l-fucopyranoside, pNP-β-d-glucopyranoside, pNP-β-d-xylopyranoside, pNP-β-d-mannopyranoside, pNP-α-l-rhamnopyranoside, and pNP-α-d-glucopyranosiduronic acid as substrates showed that the enzymes were active only on pNPG and pNPA. The activity with pNPG was on average 3.6-fold higher at 65°C and 2.6-fold higher at 80°C than the activity with pNPA (Figure 2). Km values with pNPG ranged from 4.2 to 8.5 mM, while the maximum velocity (Vmax) was determined to be 2.7–2.9 U mg−1 (Supplementary Figure S2). Therefore, the enzymes can be classified as galactofuranosidases (Gafs).

FIGURE 2. Specific activities of Cs_Gaf195A, Ch_Gaf159A and Ck_Gaf159A with pNPA and pNPG at 65 and 80°C. The pNPG-cleaving and pNPA-cleaving activities are indicated as fold changes. Standard reactions contained 0.1 µg μl−1 enzyme and were performed in triplicates and incubated for 20 min.

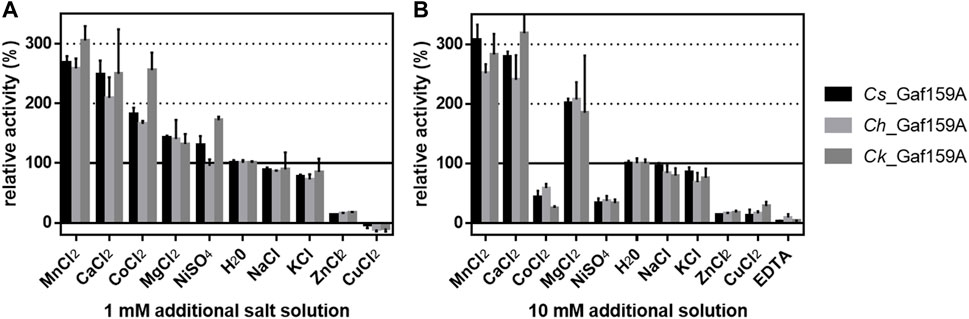

Since arabinofuranosidase activity was not previously reported for GH159 enzymes, we mainly focused on this newly detected activity in the present work. The mean specific activities on pNPA for Cs_Gaf159A, Ch_Gaf159A, and Ck_Gaf159A were 0.04, 0.04, and 0.03 U mg−1, which corresponds to 1.5, 1.5 and 1.3 U µmol−1, all respectively. To uncover the influence of different metal ions on the activity, standard assay reactions were supplemented with various salt solutions. The addition of 1 mM of MnCl2, CaCl2, MgCl2, and CoCl2 increased the activity (see Supplementary Table S1). NaCl and KCl had nearly no or a slightly negative effect, whereas addition of 1 mM ZnCl2 or CuCl2 reduced the activity by 80% (Figure 3A). At 10 mM, the effects of the salts on enzymes activity were similar, the difference being that the higher concentrations of NiSO4 and CoCl2 had an inhibitory effect (Figure 3B). The data for MnCl2, CoCl2, NiCl2, and CuCl2 that is shown in Figure 3 should not be overinterpreted due to color and precipitate formation under the assay conditions and hence interference with the assay used. Based on its activity-enhancing effect, 10 mM CaCl2 was included in the standard assay buffer. This led to at least a two-fold increase in specific activities, i.e., about 0.1 U mg−1 (3.76 U µmol−1), 0.09 U mg−1 (3.39 U µmol−1), and 0.08 U mg−1 (3.02 U µmol−1) with pNPA as substrate, of Cs-, Ch- and Ck_Gaf159A, respectively. Addition of 10 mM of the chelating agent EDTA resulted in an almost complete inactivation of all three enzymes, thus confirming their dependency on divalent metal ions (Figure 3B).

FIGURE 3. Influence of additional salt solutions on the activity of Cs_Gaf159A, Ch_Gaf159A and Ck_Gaf159 on pNPA. Reactions contained 1 mM pNPA, 5 µg enzyme (0.2 µg μl−1 stocks stored in 0.1 M MOPS pH 6.5), 0.1 M MOPS pH 6.5, and either 1 mM (A), or 10 mM (B) additional salt solutions, and were incubated for 20 min at the respective temperature optima (90, 82 and 93°C for Cs, Ch and Ck). Bars represent standard deviation from triplicates.

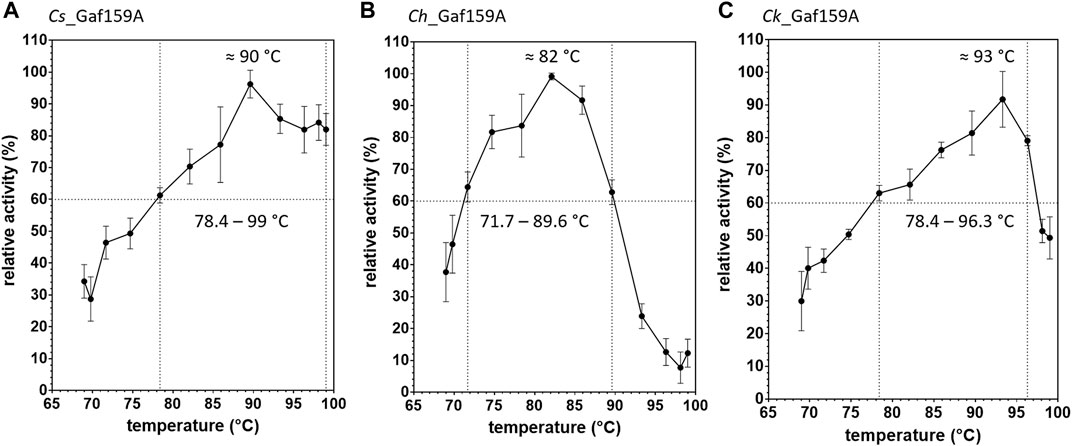

The temperature ranges in which the enzymes displayed at least 60% activity (pH 6.5) were 78.4–99.0°C for Cs_Gaf159A, 71.7–89.6°C for Ch_Gaf159A and 78.4–96.3°C for Ck_Gaf159A, whereas the temperatures for maximal activity (20 min assay with pNPA as substrate) were 90°C, 82°C, and 93°C, respectively (see Figure 4).

FIGURE 4. Effect of temperature on pNPAase activity of Cs_Gaf159A (A), Ch_Gaf159A (B) and Ck_Gaf159A (C). Relative activities to the maximal activity measured after 20 min were calculated from pNP standard reactions (2.65 µM enzyme). Bars represent standard deviation from triplicates.

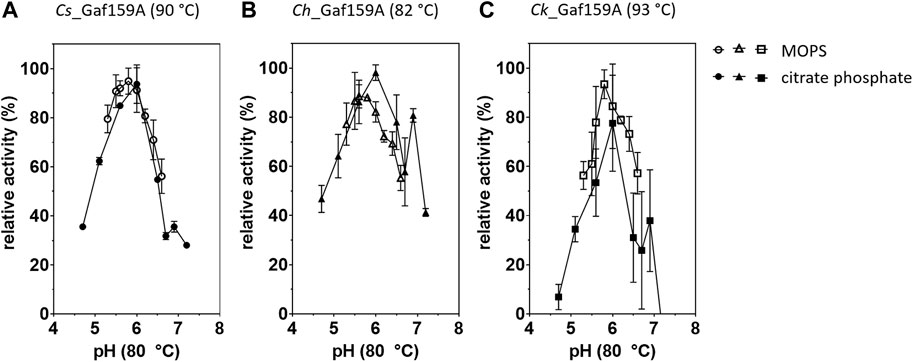

The pH optimum, as determined at the respective apparent 20 min temperature optimum of each enzyme, differed less between the enzymes than the temperature optima. Using assays carried out at 80°C all three Gafs displayed the highest activity at around pH 5.6–6 (Figure 5). At room temperature, the optimal pH levels were found to be at pH 5.5–6 in McIlvaine+ buffer and pH 6.4–6.8 in MOPS buffer (Supplementary Table S2). The specific activities in McIlvaine+ buffer were from two to more than four times lower than in MOPS, with 0.02 U mg−1 (0.8 U µmol−1) for Cs_Gaf159A and 0.03 U mg−1 (1.0 U µmol−1) for Ch_Gaf159A and Ck_Gaf159A, possibly due to complex formation between the divalent cations and the phosphate present in the McIlvaine+ buffer system.

FIGURE 5. Influence of different pH values on the activity of Cs-, Ch- and Ck_Gaf159A. Reactions contained either McIlvaine (filled symbols), or MOPS buffer (empty symbols), 2.65 µM enzyme (0.1 µg μl−1), 1 mM pNPA, 1 x RP and 1 mM CaCl2 and were incubated for 20 min at the respective temperature optimum. (A) Cs_Gaf159A, 90°C; (B) Ch_Gaf159A, 82°C; (C) Ck_Gaf159A, 93°C. Activities are related to highest activity with the respective buffer. Bars represent standard deviation from triplicates.

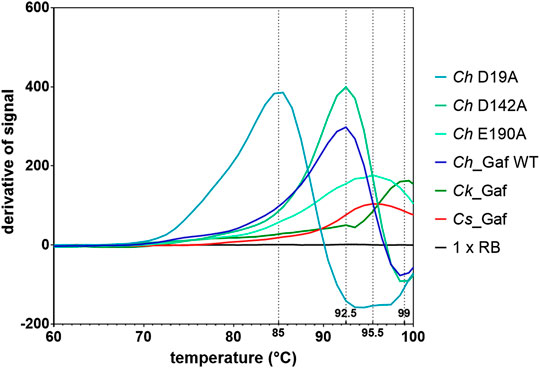

Regarding resistance against thermo-inactivation, incubation of the enzymes at their apparent “optimal” temperatures (temperature of maximum activity in a 20 min assay with substrate pNPA) indicated a high level of thermostability, especially for Cs_Gaf159A. Incubation of up to 24 h at 90°C did not seem to affect the activity of the latter. Ch_Gaf159A lost 50% of its activity after 5 h at 82°C, and Ck_Gaf159A lost nearly 50% of its activity after 2.5 h at 93 °C (Supplementary Figure S3). Although Cs_Gaf159A revealed an apparently extraordinary heat stability at 90 °C, variation of the assay time between 10 and 30 min indicated that heat inactivation at this temperature over a short time span did indeed occur (see Supplementary Figure S4). The explanation for the extreme long-term stability at 90°C may lie in the refolding of previously (partially) inactivated enzyme. This refolding may occur during cooling to room temperature after sample withdrawal and before addition of the pNP-arabinoside substrate and the measurement of residual activity. To assess the enzymes’ structural thermostability more directly, the melting temperatures (Tm) of the enzymes were determined using differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF). The apparent Tm values for Cs_Gaf159A, Ch_Gaf159A, and Ck_Gaf159A were 95.5°C, 92.5°C, and 99.0°C respectively (Figure 6), which was consistent with a high intrinsic stability of all three orthologous enzymes.

FIGURE 6. Melting temperatures of Cs_Gaf159A, Ck_Gaf159A, Ch_Gaf159A and the mutants Ch_D19A, Ch_D142A and Ch_E190A according to differential scanning fluorimetry analysis with SYPRO Orange. Smoothed differentiated curves from triplicates.

As for kinetic parameters and product inhibition, the latter was low under presumed physiological conditions, as the enzymes retained more than 50% of their activity in the presence of 500 mM arabinose in the reactions (Supplementary Figure S3). Due to the instability of the substrate pNPA at the high assay temperatures (90, 82, and 93°C) used, only short reaction times were applied.

Kinetic parameters with the chromogenic arabinoside substrate pNPA were able to be determined only up to a concentration of 10 mM. Results obtained at the standard enzyme concentration of 0.1 µg μl−1 (2.65 µM) after 10, 20 and 30 min at the enzymes’ optimal temperature are shown by way of example for Cs_Gaf159A at 90°C in Supplementary Figure S4. Substrate saturation was not reached with substrate concentrations up to 10 mM using a 10 min assay. On the other hand, the curves generated after incubation for 20 or 30 min showed some flattening at higher substrate concentrations, which is presumed to be the result of a loss of enzyme activity over time at 90°C (see above). Therefore, the reactions were stopped after 10 min in the following experiments. The curves of substrate concentration vs. reaction rates were recorded for Cs_Gaf159A and Ch_Gaf159A at various enzyme concentrations. Although the conditions for near saturation of the substrate were not met, the curves suggest a minimum Km for pNPA of at least 10 mM.

Overnight incubation of 5 mg ml−1 arabinan, arabinoxylan, arabinogalactan, and gum arabic with the three enzymes at different temperatures (65, 70, 75, and 80°C) were analyzed via the DNSA assay. Increased reducing sugar content was measureable only with arabinogalactan (containing arabinose residues linked either α-1,6 to the galactan backbone, or α-1,4 to galactose side chains) when compared to control reactions without enzyme addition. Product analysis by HPAEC-PAD revealed that only arabinose (about 5 mg L−1 corrected by enzyme and substrate controls) was liberated after an incubation period of 23 h (Supplementary Figure S5). This only accounts for about 0.6% of the possible release of arabinose, which was calculated to be 0.76 mg ml−1. This was calculated assuming 95% purity and 14% arabinose content in larch arabinogalactan (Megazyme data sheet), a substrate concentration of 5 g L−1 and the ratio in molecular weight of hydrolyzed to non-hydrolyzed arabinose of 150.13 g mol−1: 132.11 g mol−1. The calculated specific activity was 0.024 nmol min−1 mg−1.

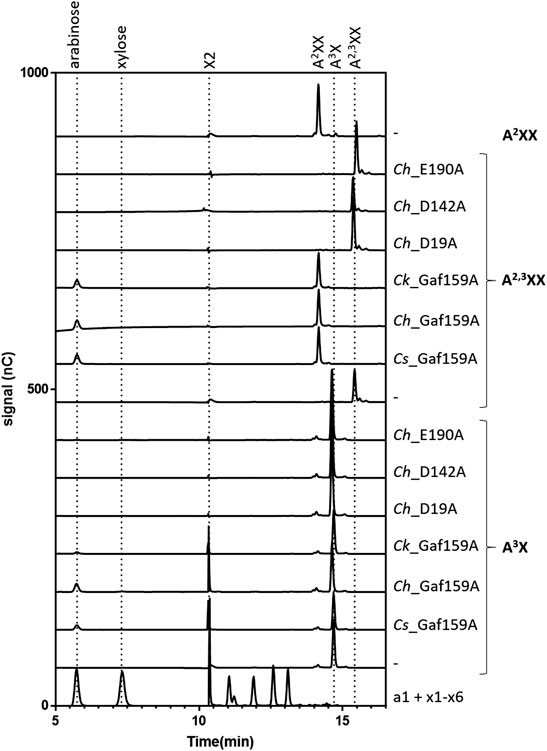

In contrast to the lack of activity against polymeric arabinoxylan, all three wildtype enzymes were able to efficiently cleave arabinoxylooligosaccharides (AXOS). HPAEC-PAD analysis (Figure 7; Supplementary Figure S6) revealed that, in 24 h reactions containing 0.1 g L−1 substrate, the arabinofuranosidase activity of Cs_Gaf159A, Ch_Gaf159A, and Ck_Gaf159A was able to fully cleave the α-l-1,3-O linkage in A2,3XX, yielding A2XX and arabinose as the only products. In contrast, in A3X-containing reactions under identical conditions only small amounts of arabinose and xylobiose (X2) were released, indicating incomplete hydrolysis of A3X.

FIGURE 7. Degradation of A2,3XX and A3X by Cs_Gaf159A, Ch_Gaf159A and Ck_Gaf159A but not by any of the Ch_Mutants. Selected HPAEC-PAD chromatograms of reactions are shown containing 0.1 g L−1 substrate (A3X, A2XX, A2,3XX, XA3XX, XAXX-Mix or XA2,3,XX), 2.4 µM Cs_, 0.8 µM Ch_, 0.3 µM Ck_Gaf159A, or 2.7 µM of the mutants: Ch_D19A, Ch_D142A, or Ch_E190A, 1 x RP, 1 mM CaCl2, and were incubated 24 h at 75°C. A complete conversion from A2,3XX to A2XX, and thus the release of arabinose, was observed for all three wild type enzymes. Small amounts of arabinose and xylobiose (X2) were produced of A3X by Cs- and Ch-, and also in less amounts by Ck_Gaf159A. A2XX, XA3XX, XAXX-Mix and XA2,3XX were not used by Cs-, Ch- or Ck_Gaf159A (supplementary Figure S10) Mutants did not show any activity.

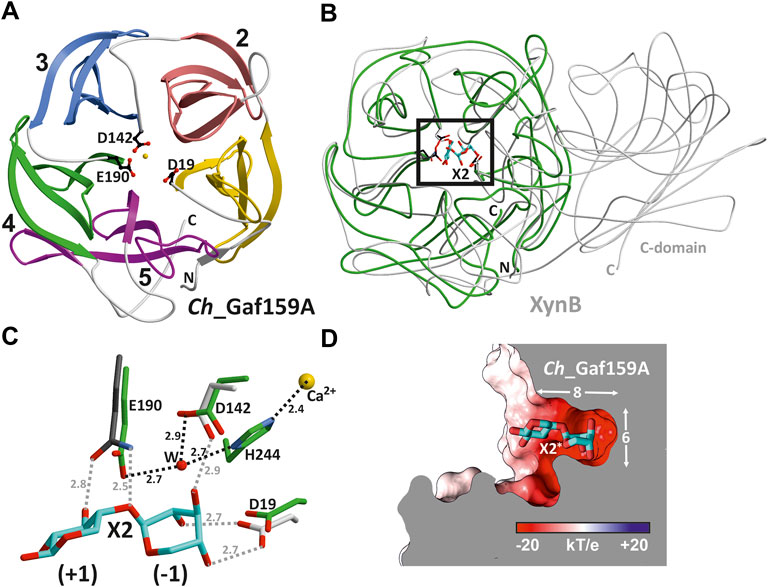

Ch_Gaf159A was crystallized and its structure determined through molecular replacement to a resolution of 1.7 Å (Rfree = 15.3%; PDB ID: 7ZEI, see Supplementary Table S3). The stable monomeric state of Ch_Gaf159A was confirmed by means of polymerization-induced self-assembly (PISA) (Krissinel and Henrick 2007) calculations and size-exclusion chromatography. The PDB Pisa analysis predicted a solvent-accessible surface area of 13519.7 Å2 and −324.2 kcal/mol free energy for folding. The fold of Ch_Gaf159A displays striking similarities to that of glycoside hydrolase family 43. A search for homologous topologies using the DALI-server (Holm and Sander 1995) revealed structures with high Z scores but low sequence identities of <20% (structural superposition of representatives with Ch_Gaf159A are shown in Supplementary Figure S7). The best hits turned out to be an exo-α-1,5-l-arabinofuranosidase from GH43_26 (root-mean-square deviation (rmsd): 1.5 Å for 173 Cα atoms, sequence identity (SI): 17%, Z = 27.0, PDB ID: 3AKI) (Fujimoto et al., 2010) and a mutant derivative (E186Q) of Bacillus pumilus β-xylosidase XynB in complex with xylobiose (rmsd 1.7 Å for 181 Cα atoms, sequence identity 15%, Z = 26.2, PDB ID: 5ZQX) classified in GH43_11 (Hong et al., 2018). However, Ch_Gaf159A is substantially smaller than its homologues, consisting of only a five-bladed β-propeller domain (Figure 8A). The metal ion present in the central cavity was modelled as Ca2+ due to the absence of any anomalous signal and the experimental findings for metal ion dependence described above (Figure 8A). Each blade is composed of four mainly antiparallel beta-strands. The overlay with XynB in complex with xylobiose (X2) suggests the substrate binding on the upper part of the barrels center (Figure 8B). The positions of E190, D142, and D19 in Ch_Gaf159A exactly matched E186, proposed to be the nucleophilic catalytic base, D127, and D14 in XynB (Figure 8C). The latter two possible catalytic aspartic acid residues of Ch_Gaf159A surround the non-reducing end of the substrate in subsite -1 of the binding site. The specific interaction with hydroxides of C2, C3, and C4 in xylobiose determines the orientation of the glycosidic linkage and therefore substrate specificity. E190 in Ch_Gaf159A is suggested as being catalytically important given its proximity to the glycosidic O and its description as a catalytic base in XynB. H244 located between D19 and D142, also adopts a putatively important position in coordinating the metal ion (Figure 8C). This matches the findings for CoXyl43 as previously described by Matsuzawa et al. (2017) (Supplementary Figure S8).

FIGURE 8. Crystal structure of Ch_Gaf159A from Caldicellulosiruptor hydrothermalis. (A) Monomeric Ch_Gaf159A adopts a β-propeller fold (PDB ID 7ZEI) consisting of five blades (ribbon drawing, linker regions in grey, N- and C-terminus marked in capitals) and houses a central metal ion (modelled as Ca2+, yellow sphere). The topology corresponds to glycoside hydrolase clan F. Asp19, Asp142 and Glu190 (shown in balls-and-sticks) are conserved residues in this enzyme class and form the catalytic center. (B) Superposition of Ch_Gaf159A (green) and mutant β-xylosidase (XynB, E186Q, PDB: 5ZQX, grey) in complex with xylobiose (X2, cyan). Ch_Gaf159A lacks the C-terminal β-sandwich domain that mediates homodimer formation in XynB (Hong et al., 2018). (C) Close up view of the active site (black rectangle in B). In XynB, hydroxy groups of X2 at position (−1) are fixed by an extensive hydrogen bonding network. The introduced E186Q mutation (dark grey) abolishes hydrolytic enzyme activity. Despite low sequence identity (15%) between Ch_Gaf159A and XynB, these residues match perfectly (labelled for Ch_Gaf159A). Distances are shown in Å, H-bonds for Ch_Gaf159A are drawn in black dots. (D) Surface representation of Ch_Gaf159A colored according to negative and positive electrostatic potentials. The modelled ligand (X2*) originates from the structural overlay with XynB and aligns with the specificity pocket (8 Å × 6 Å), indicating exo hydrolase activity of Ch_Gaf159A.

Analyses for pronounced specificity pockets at the active site identified a solvent exposed negatively charged ligand binding site with approximately 8 Å in length and 6 Å in diameter (Berka et al., 2012). The surface representation showed two electro negative pockets, one of them capable of incorporating the X2 ligand (Figure 8D). This substrate pocket structurally explains why Ch_Gaf159A acts as an exo-arabinofuranosidase, or -galactofuranosidase. The substrate can only enter the pocket at one end and is specifically bound in the -1 subsite (Figure 8D).

The sequence of Ch_Gaf159A also structurally aligned (Supplementary Figure S9) with the catalytic residues of GH43_33 HoAraf (PDB 4QQS), an α-l-arabinofuranosidase from Halothermothrix orenii (Hassan et al., 2015). The known conserved catalytic nucleophile of HoAraf (E195) aligned with E190 in Ch_Gaf159A, the catalytic base D17 (HoAraf) with D19, and D126 in HoAraf corresponded to D142 in Ch_Gaf159A. This indicated that all three residues are catalytically important.

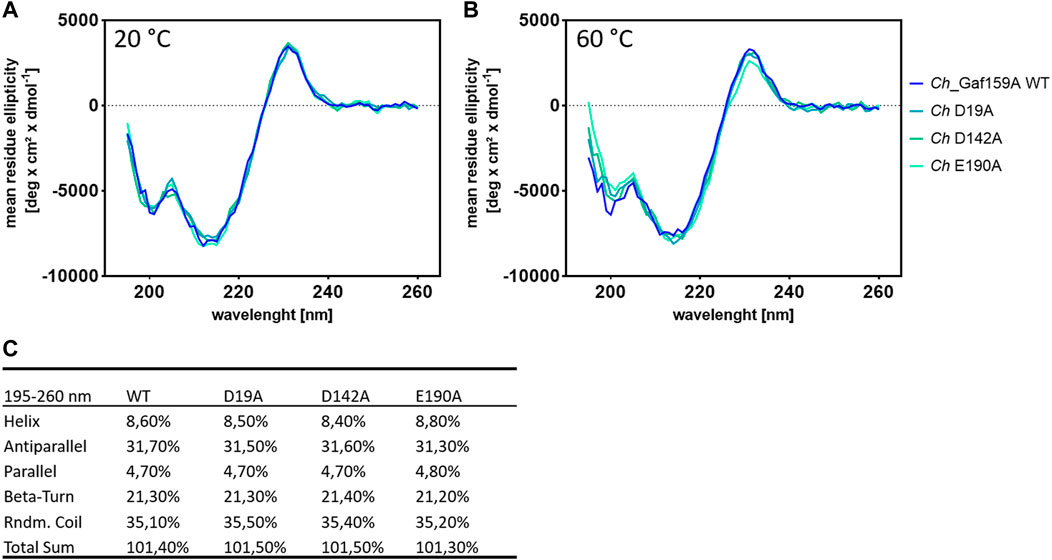

Therefore, three variants of Ch_Gaf159A were generated at the possible catalytic amino acid position E190, D19 and D142, each containing an alanine residue instead of the proposed catalytic residue. All three mutants lost the ability to cleave pNPA, as well as A2,3XX and A3X (Figure 7), nor did they show any activity against the other tested AXOS (Supplementary Figure S10). The behavior during expression, purification, or protein analysis exhibited change in none of the mutants (Mut I D19A, Mut II D142A, or Mut III E190A) as compared to the wildtype Ch_Gaf159A. DSF analyses revealed that the melting temperature Tm of Mut II (D142A) was unchanged. In contrast, the Tm of Mut I (D19A) was reduced by 7.5°C, and that of Mut III (E190A) increased by 3°C (Figure 6). Since differences in melting temperatures could indicate differences in folding properties, Circular Dichroism (CD) measurements were additionally performed. The far UV CD-spectra of the mutants compared to wild type indicated no changes in secondary structure and probably none in the overall folding properties of the backbone either (Rodger 2018), at 20°C (Figure 9A). In addition, the curves were identical for WT and mutants at 60°C (Figure 9B). Since the wild type still showed about 50% of its activity at 60°C, it can be assumed that the wild type was correctly folded at this temperature, which also applied to the mutants. According to the secondary structure composition deduced from the CD spectra by computational analysis, all Ch_Gaf159A variants are composed of 31–32% antiparallel beta-strands, 21% beta turns, and 8–9% helical structures. The proportion of random coils was calculated to be 35–36% in WT and mutants (Figure 9C).

FIGURE 9. Circular dichroism measurements for Ch_Gaf159A and its mutants Ch_D19A, Ch_D142A and Ch_E190A. CD spectra obtained at 20°C (A) and 60°C (B) and, secondary structure composition revealed by computational spectra analysis at 20°C (C).

A function-based, experimentally confirmed nomenclature for proteins is needed in order to achieve meaningful annotation of new gene and protein sequences, and to supply references for the functional and structural prediction of proteins (Gupta and Sardar 2021). This work focused on the biochemical and structural characterization of three members of the recently described glycoside hydrolase family GH159 in order to contribute to the overall characterization of this enzyme family. To this end, we chose three GH159 enzymes from the Caldicellulosiruptor species C. saccharolyticus, C. hydrothermalis, and C. kronotskyensis and succeeded in obtaining the proteins with a high degree of purity by means of recombinant expression and affinity purification.

In agreement with the first characterized GH159 enzyme, which was a β-d-galactofuranosidase from Bacteroides cellulosilyticus WH2 (ALJ59596.1), all three Caldicellulosiruptor enzymes showed activity towards the model-substrate pNP-β-d-galactofuranoside (pNPG). In addition, we observed weaker activity against pNP-α-l-arabinofuranoside (pNPA). The occurrence of arabinofuranosidase (Abf) and galactofuranosidase (Gaf) activity in one enzyme has also been observed for other enzymes (Tefsen et al., 2012; Pavic et al., 2019). This is plausible because the two sugars differ by only one carbon atom, which is not involved in furanose ring formation (Chlubnová et al., 2010). Due to their β-d-galactofuranosidase activity (EC 3.2.1.146), the gene products of Casc_0437 (ABP66075.1), Calhy_0274 (ADQ06027.1), and Calkro_0290 (ADQ45201.1) were termed β-d-galactofuranosidases (Gafs) according to common nomenclature. However, this study focused on the α-l-arabinofuranosidase activity (EC 3.2.1.55) as this activity had not yet been described for GH159. In addition, the thermostable Caldicellulosiruptor enzymes may be useful as added enzymatic activities enhancing the degradation of arabinose-containing lignocellulosic polysaccharides. The complete saccharification of lignocellulose is a desirable goal for the sustainable industrial production of bioethanol and chemicals (Østby et al., 2020), while galactofuranose-containing substrates are less common in lignocellulosic biomass (Seiboth and Metz 2011).

In accordance with the high sequence identity between the three enzymes Cs_Gaf159A, Ch_Gaf159A and Ck_Gaf159A (more than 90% with 100% query coverage), their biochemical characteristics in terms of activity, substrate specificity, pH optimum (between 5.5 and 6, measured at 80 °C) were identical. Additionally, cation dependence, and to some extent also their temperature preference for activity (maximum activity in a 20 min assay between 82 and 93°C), as well as thermal stability, were all similar. Like some other glycoside hydrolases (Ahmed et al., 2013; Baudrexl et al., 2019), Cs_Gaf159A, Ch_Gaf159A, and Ck_Gaf159A are activated by divalent metal ions. The greatest effect was observed with either MnCl2 or CaCl2 ions (Figure 3).

As can be expected for proteins of extremely thermophilic bacteria that grow optimally at temperatures of 70°C, the Caldicellulosiruptor enzymes Cs_Gaf159A, Ch_Gaf159A, and Ck_Gaf159A displayed a high level of resistance against thermal inactivation. In particular, Cs_Gaf159A was able to be incubated for 24 h at its temperature of maximum activity of 90°C, apparently without losing activity (Supplementary Figure S3). On the other hand, an indication that heat inactivation of Cs_Gaf159A at this temperature did occur was obtained by varying the assay time between 10 and 30 min (see Supplementary Figure S4). The explanation for the apparent extreme long-term stability at 90°C may lie in the efficient refolding of previously (partially) inactivated enzyme enabled by the assay conditions. In this case, after incubation of Cs_Gaf159A at 90°C and sample withdrawal, the samples were cooled to room temperature before the pNP-arabinoside substrate was added for measurement of residual activity. During this cooling period, refolding of previously (partially) inactivated enzyme may have occurred, meaning that the reversibility of potential temperature-induced (partial) unfolding rather than the thermostability had been tested. If this hypothesis, which has not been tested within this study, is correct, then Cs_Gaf159A is the most flexible protein of this study. Namely, it was probably able to correctly refold after incubation at 90°C for 24 h and regain its original activity. This is an often observed phenomenon with thermophlic proteins and for instance has been reported for the catalytic domain of xylanase Xyn10B (Araki et al., 2006). As an outlook, it would be interesting to study the folding and unfolding properties of Cs_Gaf159A in particular.

Temperature-dependent denaturation was evaluated by determining the enzymes’ melting temperatures (Tm) via DSF. The Tm reflects a protein’s intrinsic thermal stability, which is usually higher than the physiological temperature to which the protein is exposed to in its natural environment (Menzen 2014). With this approach, Ck_Gaf159A showed the highest Tm (99°C), which is consistent with the finding that it had the highest “optimal” temperature, i.e., the temperature for maximum activity in a 20 min assay (TOpt = 93°C), followed by Cs_Gaf159A (Tm = 95.5°C) and Ch_Gaf159A (Tm = 92.5°C). Compared to the 20 min optimal temperatures the melting temperatures of Cs_Gaf159A, Ch_Gaf159A and Ck_Gaf159A were 5.5°C, 10.5°C, and 6°C higher, respectively. The melting curves indicate that the enzymes start to partially unfold at their “optimum” temperatures (90°C, 82°C, and 93°C), which may account for the observed activity loss over time. The dye used for DSF, SyproOrange, binds to hydrophobic regions in proteins. Considering the high overall sequence similarity of the enzymes and the fact that the number of hydrophobic residues was almost the same, the differences in both Tm (92.5—99°C) and TOpt (20min) values (82—93°C) for the investigated enzymes were relatively high. The counts of hydrophobic residues were 23, 24, and 24 for Cs_Gaf159A, Ch_Gaf159A, and Ck_Gaf159A, respectively (Supplementary Table S4). The melting curves suggest that all of the enzymes investigated could be stable at approximately 70°C for extended periods of time, which nicely matches the optimal growth temperature of Caldicellulosiruptor species (see above). The Tm values were much higher than the optimum growth temperature and a significant resistance against thermo-inactivation has been observed, even at temperatures 20°C above the optimum growth temperature. This may be advantageous for bacteria thriving in hot springs, because significant temperature fluctuations often found in such habitats would not lead to irreversible enzyme inactivation. With regard to the methodology used for assessing the thermostability of enzymes, DSF clearly is a more suitable method than activity-based methods. In activity-based methods, incubation times as well as refolding of previously unfolded, and thereby inactivated, enzyme play a crucial role. Adding preheated substrate to the preincubated enzymes without cooling of the enzymes would avoid refolding during the cooling period, but this approach is experimentally challenging at temperatures around and above 80 °C.

Due to the low specificity for pNPA and the instability of pNPA at higher temperatures, kinetic parameters were not able to be evaluated. However, using 10 mM as the highest pNPA concentration and enzyme concentrations of 0.036 µM it can be concluded that the Michaelis Menten constant Km must at least be higher than the substrate concentration of 10 mM (Li 2017). This and the values obtained using pNPG as a substrate (4.2–8.5 mM), were higher than most of the reported Km values for Abf, which range from about 0.1 to 1.5 mM pNPA (Inacio et al., 2008; Matsuzawa et al., 2017; Coconi Linares et al., 2022).

The substrate specificity of the enzymes was tested using a range of glycosidic substrates. Cs_Gaf159A, Ch_Gaf159A and Ck_Gaf159A were not able to cleave the backbone or the sidechain arabinosidic linkages (arabinose residues linked α-1,3 and α-1,5 to backbone arabinoses) present in arabinan, arabinoxylan (arabinose residues linked α-1,2 and/or α-1,3 to xylan backbone), or gum arabic. The latter is a complex heteropolysaccharide containing l-arabinose (Pragnesh and Ankur 2018) in the main and side chains (Musa et al., 2018) and probably at least some non-reducing terminal Araf-residues (Tagawa and Kaji 1969). In contrast, the enzymes exhibited arabinosidase activity on the polysaccharide arabinogalactan, which contains sidechains with terminal arabinofuranose residues (Robinson et al., 2008) which may be cleaved off. The absence of the enzymes’ activity with arabinan, arabinoxylan and gum arabic, as well as the limited activity on arabinogalactan in addition to their activity on small substrates such as pNPA and various AXOS indicates that the arabinosidase activities of Cs_Gaf159A, Ch_Gaf159A, and Ck_Gaf159A should be affiliated with the type A arabinofuranosidases (Bourgois et al., 2007). Furthermore, the lack of signal peptides in all three enzymes indicates their intracellular localization. This matches their preference for low molecular mass substrates such as arabinose-containing oligosaccharides, which are far more likely to be encountered intracellularly than polysaccharides are (Reintjes et al., 2017).

In addition to preferences for poly- or oligosaccharides, or for substrates of a small size, further specificity characteristics have been described for a special group of arabinofuranosidases, the arabinoxylan arabinofuranohydrolases (Axh). A simple nomenclature was proposed by Vandermarliere et al., 2009 for different specificities, e.g. Axh-d3 (van Laere et al., 1999; van den Broek et al., 2005; Sørensen et al., 2006), Axh-m2,3 (van Laere et al., 1999; Wang et al., 2014), Axh-m3 (Kormelink et al., 1993) or Axh-m,d2 (Cartmell et al., 2011). This nomenclature depends on whether arabinofuranose residues are cleaved from double substituted xylose residues (d), or from mono-substituted xyloses (m) and taking into account the preference for 1,3- or 1,2-linkages. Adapting this nomenclature to the arabinofuranosidase activities of the enzymes of this study against AXOS, Axh-m,d3 activity seems to be insufficiently specific since Cs_Gaf159A, Ch_Gaf159A, and Ck_Gaf159A preferentially cleave α-1,3 linkages only when the non-reducing end of the arabinosylated xylose residue is free, such as in A2,3XX and also in A3X. In contrast, XA3XX, or XA2,3XX, are not substrates.

Different preferences for internal and external substituents have previously been described, e.g., a GH51 arabinofuranosidase with Axh-m,d activity on the terminal, but Axh-m activity on internal Xylp residues (Koutaniemi and Tenkanen 2016). The fact that the Caldicellulosiruptor enzymes cleaved only small amounts of arabinose from A3X, and that polymeric substrates were not efficiently hydrolyzed, indicates either that only oligosaccharides of a certain size can be fitted into the substrate-binding pocket of the enzyme, or that double-substituted xylose residues are preferred. To verify this experimentally, it would be helpful to test additional substrates with substitutions (single or double) at the first xylose residue (counted from the non-reducing end), such as A3XX, A3XXX, A2,3X, and A2,3XXX. However, these are not commercially available. Even though the actual role of the enzymes Cs_Gaf159A, Ch_Gaf159A, and Ck_Gaf159A for the producing bacteria has never been investigated, a role in the intracellular degradation and further utilization of arabinose-containing oligosaccharides in concert with backbone cleaving enzymes would be conceivable, as described for AbfA and Abf2 of B. subtilis (Inacio et al., 2008).

Crystallization and elucidation of the molecular structure of the WT Ch_Gaf159A (PDB: 7ZEI) protein revealed a 5-fold beta propeller structure, which is a conserved fold for glycoside hydrolases present in clan GH-F (GH43, GH62 and GH117) and GH-J (GH32 and GH68). In contrast to clan GH-J enzymes, which are active on fructose-containing substrates and retain the net configuration, GH-F enzymes invert the configuration at the anomeric carbon of their β-d-xylopyranosylated, α-l-arabinofuranosylated, or β-d-galactofuranosylated substrates. The specificity towards these three sugar moieties is conceivable, as the orientation of the ring substituents is identical for C1, C2, C3 and C4 (Supplementary Figure S11). The cleavage specificity of Cs_Gaf159A, Ch_Gaf159A and Ck_Gaf159A for β-d-Galf and α-l-Araf substituted substrates, as well as the similar positioning of the catalytic residues compared with GH43_11 XynB, suggests that also GH159 enzymes act via an inverting cleavage mechanism and should be included in GH clan F. However, the catalytic mode was not investigated so far. The central ion which was modelled in the Ch_Gaf159A structure as Ca2+ due to the experimental findings described before matches the results obtained for other GH-F enzymes, such as GH62 4080 (Wang et al., 2014), GH117 4AK7 (Hehemann et al., 2012), or GH43_1 5GLR (Matsuzawa et al., 2017), whose structures also contained a metal ion.

Residues E190, D142, and D19, which in the three-dimensional Ch_Gaf159A structure are found in close proximity to each other in the center of the channel formed by the β-propeller, perfectly matched the catalytically essential amino acid residues of a structurally similar enzyme of GH43_11 (XynB; 5ZQX; SI: 15%) in an overlay of both enzyme structures and also in a structural alignment with HoAraf (4QQS; SI: 27%). Therefore, they were suggested as possible catalytical residues for Ch_Gaf159A. The complete loss of activity of the Ch_Gaf159A mutants D19A, D142A and E190A, which was tested with pNPA, AXOS and arabinogalactan, confirmed this prediction. The topology of the crater-shaped substrate specificity pocket also revealed the structural basis for the exo-activity that has been experimentally observed. In analogy, the structural homolog 5ZQX was reported to display β-xylosidase activity but had no activity toward the polysaccharide xylan (Xu et al., 1991; Hong et al., 2018). The bifurcated binding pocket reinforces the experimentally obtained assumption that d-AXOS are preferred over m-AXOS. However, the crystallization of the glutamine mutant E190Q in complex with the substrate A2,3XX to confirm the specific binding of d-AXOS was not successful yet. The liganded structure would have been necessary to shed light on the orientation of the substrate backbone and the residues involved, which would have allowed the analysis of the observed preference towards low molecular mass substrates.

In conclusion, this study elucidated the first 3D structure of a representative of the glycoside hydrolase family GH159. The analyses revealed molecular details of substrate binding and the catalytic mechanism of enzymes belonging to this family. α-l-arabinofuranosidase activity (EC 3.2.1.55), which has not been reported for the most closely related GH159 enzyme (BcellWH2_02356; Helbert et al., 2019) was biochemically characterized for the three GH159 members of this study, in addition to β-d-galactofuranosidase activity (EC 3.2.1.146). In retrospect, the observation of arabinofuranosidase activity in GH159 is expected due to structural similarities with GH43 family members. Taken together, the work reported here adds a new cleavage specificity not known before to glycoside hydrolase family GH159 as well as its protein fold.

The Carbohydrate Active Enzymes (CAZy) database (http://www.cazy.org/Glycoside-Hydrolases.html; Lombard et al., 2014) was scoured, and homology analysis was performed using the NCBI tool BLASTp (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi). Signal peptides were predicted using the SignalP 4.1 server (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP-4.1/; (Petersen et al., 2011). Structural information was extracted from the RCSB PDB Protein Data Bank (http://www.rcsb.org/). Structural alignments were created using HHpred, a MPI Bioinformatics Toolkit (https://toolkit.tuebingen.mpg.de/tools/hhpred; Zimmermann et al., 2018) to compare conserved catalytic amino acids.

The bacterial strains C. saccharolyticus DSM 8903, C. hydrothermalis 108 (DSMZ 18901), C. kronotskyensis 2002 (DSMZ No. 18902) were obtained from the DSMZ (Braunschweig, Germany). Dried cells were rehydrated with 500 µl GS2 medium (Johnson et al., 1981; Koeck et al., 2015) for 30 min under anaerobic atmosphere in an anaerobic chamber (98% N2, 2% H2; Coy Laboratory Products). An aliquot of 250 µl was used to inoculate 50 ml GS2 medium in butyl rubber-stoppered serum bottles with 0.1% cellobiose. Another 100 µl were plated in the anaerobic chamber onto a GS2 agar plate (1.8% agar). Cells were cultivated anaerobically at 65°C for 5 days (bottles without shaking). Genomic DNA of a clonal culture inoculated from a single colony was isolated using the Gentra® Puregene® kit for Yeast and Bacteria Kit (Qiagen). Briefly, 5 ml of the bacterial culture was centrifuged for 1 min at 13,000 rpm. After discarding the supernatant, the protocol for DNA isolation was followed in accordance with the manufacturer’s description for Gram-positive bacteria. However, 1.5 μl of lysozyme (730 U ml−1) was used instead of 1.5 μl of the Lytic Enzyme Solution. PCR-amplified DNA fragments were purified using NucleoSpin® Gel and PCR Clean-up kits (Macherey-Nagel).

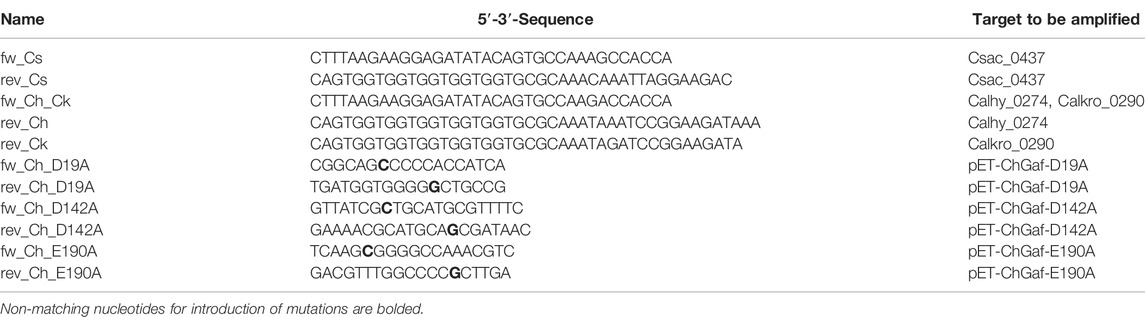

Recombinant Escherichia coli strains DH10B (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States) and BL21 Star (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, United States) were aerobically grown in LB-Lennox medium with 50 µg ml−1 kanamycin at 180 rpm and 37°C. Plasmids were isolated from overnight cultures using the NucleoSpin Plasmid kit from Macherey-Nagel (Düren, Germany). Amplified DNA was purified using the NucleoSpin® Gel and PCR Clean-up (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany). Plasmid pET24c (+) (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) was amplified in E. coli DH10B, cut with NdeI and XhoI (New England Biolabs GmbH, Frankfurt, Germany) and purified from an 1% agarose gel. The genes coding for the GH159 enzymes with arabinofuranosidase activity from C. saccharolyticus (Cs_Gaf159A; ABP66075.1), C. hydrothermalis (Ch_Gaf159A; ADQ06027.1) and C. kronotskyensis (Ck_Gaf159A; ADQ45201.1) were amplified from genomic DNA by PCR using Phusion High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific, A, United States), genomic DNA of the respective strain and primer pairs as listed in Table 1. Cloning of pET24c(+) constructs was accomplished by Gibson Assembly (Gibson et al., 2009) using purified PCR product and restricted vector as described above, followed by transformation of strain E. coli DH10B. Sanger sequencing at Eurofins Genomics (Ebersberg, Germany) verified sequence integrity before enzyme production in E. coli BL21 Star™, isolation and purification by immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC) was carried out as described previously (Baudrexl et al., 2019). The eluates from IMAC were incubated at 50°C for 15 min to denature remaining E. coli proteins followed by precipitate removal by centrifugation. Size and purity of the proteins were confirmed by SDS-PAGE (Laemmli 1970). Protein concentration was determined spectrophotometrically at 280 nm under denaturing conditions (5 M urea) using the molar extinction coefficients, calculated by the ExPaSy ProtParam tool (https://web.expasy.org/protparam/) from the Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics (Artimo et al., 2012).

TABLE 1. Primers for amplification of gene fragments for Gibson-Assembly and site directed mutagenesis.

Crystals of Ch_Gaf159A (Genbank: ADQ06027.1, Uniprot: E4QB49) from C. hydrothermalis were grown at 20°C within 14 days to a final size of 300 μm × 100 μm × 100 μm by using the sitting drop vapour diffusion method. The drops contained 0.3 µl protein (30 mg ml−1) and 0.1 µl reservoir (100 mM 2-(N-morpholino)-ethanesulfonic acid, pH 6.5, 30% (w/v) polyethylene glycol 8000, and 5% (v/v) glycerol). Before exposure to X-rays, crystals were soaked in a mixture of mother liquor and glycerol (5:1, v/v) for 30 s and vitrified in liquid nitrogen. A native diffraction data set was collected using synchrotron radiation at the X06SA-beamline, SLS, Switzerland. Reflection intensities were evaluated with the program package XDS and data reduction was carried out with XSCALE (Kabsch 2010) (Supplementary Table S3). Initial phases were obtained by Patterson search calculations with PHASER (McCoy et al., 2007) using a starting model predicted by alphafold2 (Jumper et al., 2021). Six monomers could be positioned in the asymmetric unit. Phases were improved by cyclic non-crystallographic averaging methods, resulting in an electron density map that allowed to correct misaligned secondary structure elements and loop connections. The structure was completed in successive rounds of model building with COOT (Emsley and Cowtan 2004) and refined with REFMAC5 (Vagin et al., 2004). Water molecules were placed with ARP/wARP solvent (Perrakis et al., 1997). The determined crystal structure has superb crystallographic values (Rcrys = 0.128 and Rfree = 0.153), was proven to fulfil the Ramachandran plot (Supplementary Table S3) and evaluated by MolProbity (Williams et al., 2018). Interface areas were calculated with PISA (‘Protein interfaces, surfaces and assemblies’ service at the European Bioinformatics Institute) (Krissinel and Henrick 2005). Coordinates and structure factor amplitudes have been deposited in the RCSB Protein Data Bank under the accession code 7ZEI.

Mutations were introduced into the gene sequences via site directed mutagenesis. For this, linear fragments with overlapping ends were amplified using PCR reactions with reverse complementary primer pairs with single nucleotide changes as indicated in Table 1 and the constructed vector pET24c-ChGaf159A as template. Reactions were subjected to complete digestion with DpnI to remove non-mutated methylated template DNA isolated from the cloning strain E. coli DH10b (Marinus and Løbner-Olesen 2014). Transformation of this strain using the resulting linear DNA with overlapping ends lead to self-circularization upon replication in the transformed cells. The expected mutations were verified by sequencing.

Standard reactions with pNP-glycosides, purchased from Megazyme (Wicklow, Ireland), were performed in a total volume of 50 µl with 1 mM substrate and 2.65 µM enzyme (1 µg μl−1) in standard reaction buffer (100 mM MOPS pH 6.5, 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM CaCl2) for 20 min at the indicated temperature. For a first screening, pNP-glycoside reactions were incubated at 65°C, the optimal growth temperature of Caldicellulosiruptor. For further biochemical characterization, the respective apparent “temperature optima” (temperatures at which maximum activity was measured under standard assay conditions in a 20 min assay) were used, i.e., 90°C for Cs_Gaf159A, 82°C for Ch_Gaf159A, and 93°C for Ck_Gaf159A. Reactions were performed in triplicates and stopped by adding 100 µl 1 M Na2CO3. Color formation from released pNP was quantified by spectrophotometric measurement of 100 μl at 405 nm and calculated using a standard curve created with pNP as reference.

Activity on various pNP glycosides was assessed by prolonged overnight incubation to detect even very low activity. Dependency on and response to ions was examined by using 100 mM MOPS buffer pH 6.5 in standard reactions with and without addition of salt solutions (1–10 mM of CaCl2, NaCl, CuCl2, NiSO4, KCl, MnCl2, MgCl2, FeCl3, ZnCl2, CoCl2, NH4Cl, K2HPO4, KSO4, KNO3, or K2CO3). For this purpose, the storage buffer for the enzymes was changed to 0.1 M MOPS pH 6.5 without additional ions, either by diafiltration using Vivaspin columns, cutoff 10 kDa (Sartorius AG, Goettingen, Germany), or by using PD-10 desalting columns (Cytiva Europe GmbH, Freiburg, Germany). Temperature optima were determined by measuring activities in a gradient thermocycler (TAdvanced 96S, Biometra, Göttingen, Germany), with a span of 40°C over 12 reactions.

Because the pH tolerance strongly depends on the temperature, an established high throughput method was used to analyze the pH optima as described by Herlet et al. (2017). Citric acid—phosphate buffer was prepared in the style of (McIlvaine 1921), but stock solutions were supplemented with 0.1 M NaCl (McIlvaine+) as described by Herlet et al. (2017). This buffer system (pH 4.5–8) was used in a ratio of 1:2, whereas MOPS buffer (pH 6–7.4) was used in final concentrations as in the standard reactions (0.1 M). Buffers were prepared at room temperature. To take the temperature dependency into account, pH values were additionally measured at 80 °C to use actual pH values under reaction conditions to visualize the pH optima. Values for both buffers at RT and 80°C can be found in Supplementary Table S2.

Kinetic parameters vmax and Km as known from the Michaelis Menten equation

For activity based stability tests standard reactions were preincubated at different temperatures and then briefly cooled on ice before the substrate was added. To assess intrinsic protein thermal stability, DSF was performed in a C1000 Touch Thermal Cycler equipped with the CFX96 Real-Time System (Bio-Rad). Reactions contained 4 µM protein in reaction buffer (100 mM MOPS pH 6.5, 10 mM CaCl2, 50 mM NaCl) and 20x SYPRO® Orange Protein Gel Stain (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) diluted in the respective buffer in a total volume of 50 µl. Triplicates were pipetted on ice in white RT-PCR 96-well plates, sealed with Microseal®B Adhesive Sealer (Bio-Rad, MSB-1001). Samples were incubated at the initial temperature (25°C, or 50°C) for 10 min before the temperature was increased every 15 s by 1°C each. Fluorescence was measured each time before the temperature changed. The measured values and respective temperatures were recorded at the respective time points. Interpretation of the saturation curves was performed using the xy analysis method “Smooth differentiate curve” in Graphpad Prism 7.00.

CD spectroscopy was conducted with 0.1 µg μl−1 enzyme in 10 mM Tris pH 6.5, using a Jasco–J710 CD spectrometer (Oklahoma City, OK, United States), a 1 mm cuvette, a range from 195 to 260 nm, and the signal average of 10 scans at 20 and 60°C as described by Stelzer et al. (2008). Secondary structure compositions were obtained after calculation of molar elipticity from signals in mdeg on the basis of reference spectra (Poschner et al., 2007).

The reactions used to test the ability of the enzymes to cleave arabinose from polysaccharides contained 0.5% wheat medium viscosity arabinoxylan (P-WAXYM, Megazyme, Wicklow, Ireland), sugar beet arabinan (P-ARAB, Megazyme), larch arabinogalactan (P-ARGAL, Megazyme) or acacia gum arabic (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), 1x RP (100 mM MOPS pH 6.5, 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM CaCl2), and 2.65 µM of the respective enzyme. Reactions were incubated overnight at 65, 70, 75, or 80°C. Preferences for specific arabinosyl linkages in arabinoxylan-derived oligosaccharides (AXOS) purchased from Megazyme were tested using an 24 h incubation at 75°C and just 0.01% (100 mg L−1) of the respective substrate as follows: Either 32-α-l-arabinofuranosyl-xylobiose (A3X), 23-α-l-arabinofuranosyl-xylotriose (A2XX), 23,33-di-α-l-arabinofuranosyl-xylotriose (A2,3XX), 23,33-di-α-l-arabinofuranosyl-xylotetraose (XA2,3XX), 33-α-l-arabinofuranosyl-xylotetraose (XA3XX), or a mixture of XA3XX and 23-α-l-arabinofuranosyl-xylotetraose (XA2XX) which is referred to as XAXX-Mix. The number in the exponent indicates which xylose counting from the reducing end, and the integer of the base shows which oxygen atom of this xylose is substituted with arabinose (Supplementary Figure S12; abbreviations adopted from Fauré et al., 2009).

Hydrolysates were analyzed for the liberated reducing ends using the dinitrosalicylic acid method (DNSA), as described elsewhere (Wood and Bhat 1988). To summarize, 50 µl of reactions, or arabinose standard solutions (0.2–2 mg ml−1) were mixed with 75 µl reagent (10 g L−1 dinitrosalicylic acid, 200 g L−1 potassium sodium tartrate, 10 g L−1 NaOH, 0.5 g L−1 Na2SO4, 2 g L−1 phenol) and heated at 95°C for 10 min. After measuring 100 μl at 540 nm, values were interpolated from arabinose standard curves using non-linear regression in GraphPad Prism 7.

High performance anion exchange chromatography with pulsed amperometric detection (HPAEC-PAD) of polysaccharide and oligosaccharide hydrolysates was conducted as described (Mechelke et al., 2017; Baudrexl et al., 2019) at an adjusted gradient: During the first 10 min, a gradient from 0 to 100 mM sodium acetate was used; in the following 20 min a second linear gradient to a final concentration of 800 mM NaOAc was suitable for separating the arabinoxylan-derived oligosaccharides in a shorter time. In addition, the arabinose was quantified using arabinose solutions (12.5–200 mg L−1) as external standards.

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.

MB, VZ, and WL designed the research. MG carried out enzyme crystallization and evaluation of the data. MB, TF, and BB performed the biochemical experiments and interpreted the data. MB, WS, and WL wrote the manuscript. All of the authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

We gratefully acknowledge Walter Stelzer and Prof. Dr. Langosch (Chair of Biopolymer Chemistry, Technical University Munich) for the circular dichroism measurements and their evaluation.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmolb.2022.907439/full#supplementary-material

Ahmed, S., Luis, A. S., Bras, J. L. A., Ghosh, A., Gautam, S., Gupta, M. N., et al. (2013). A Novel α-L-Arabinofuranosidase of Family 43 Glycoside Hydrolase (Ct43Araf) from Clostridium Thermocellum. PloS one 8 (9), e73575. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0073575

Araki, R., Karita, S., Tanaka, A., Kimura, T., and Sakka, K. (2006). Effect of Family 22 Carbohydrate-Binding Module on the Thermostability of Xyn10B Catalytic Module fromClostridium Stercorarium. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 70 (12), 3039–3041. doi:10.1271/bbb.60348

Artimo, P., Jonnalagedda, M., Arnold, K., Baratin, D., Csardi, G., de Castro, E., et al. (2012). ExPASy: SIB Bioinformatics Resource Portal. Nucleic acids Res. 40 (Web Server issue), W597–W603. doi:10.1093/nar/gks400

Baudrexl, M., Schwarz, W. H., Zverlov, V. V., and Liebl, W. (2019). Biochemical Characterisation of Four Rhamnosidases from Thermophilic Bacteria of the Genera Thermotoga, Caldicellulosiruptor and Thermoclostridium. Sci. Rep. 9 (1), 15924. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-52251-0

Berka, K., Hanak, O., Sehnal, D., Banas, P., Navratilova, V., Jaiswal, D., et al. (2012). MOLEonline 2.0: Interactive Web-Based Analysis of Biomacromolecular Channels. Nucleic Acids Res. 40 (W1), W222–W227. doi:10.1093/nar/gks363

Bourgois, T. M., van Craeyveld, V., Van Campenhout, S., Courtin, C. M., Delcour, J. A., Robben, J., et al. (2007). Recombinant Expression and Characterization of XynD from Bacillus Subtilis Subsp. Subtilis ATCC 6051: a GH 43 Arabinoxylan Arabinofuranohydrolase. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 75 (6), 1309–1317. doi:10.1007/s00253-007-0956-2

Cartmell, A., McKee, L. S., Peña, M. J., Larsbrink, J., Brumer, H., Kaneko, S., et al. (2011). The Structure and Function of an Arabinan-specific α-1,2-Arabinofuranosidase Identified from Screening the Activities of Bacterial GH43 Glycoside Hydrolases. J. Biol. Chem. 286 (17), 15483–15495. doi:10.1074/jbc.m110.215962

Chlubnová, I., Filipp, Dominik., Spiwok, Vojtech., Dvořáková, Hana., Daniellou, Richard., Nugier-Chauvin, Caroline., et al. (2010). Enzymatic Synthesis of Oligo-D-Galactofuranosides and L-Arabinofuranosides: from Molecular Dynamics to Immunological Assays. Org. Biomol. Chem. 8 (9), 2092–2102. doi:10.1039/B926988F

Coconi Linares, N., Li, X., Dilokpimol, A., and Vries, R. P. (2022). Comparative Characterization of Nine Novel GH51, GH54 and GH62 α‐ L ‐arabinofuranosidases from Penicillium subrubescens. FEBS Lett. 596 (3), 360–368. doi:10.1002/1873-3468.14278

Emsley, P., and Cowtan, K. (2004). Coot: Model-Building Tools for Molecular Graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Cryst. 60 (Pt 12 Pt 1), 2126–2132. doi:10.1107/S0907444904019158

Fauré, R., Courtin, C. M., Delcour, J. A., Dumon, C., Faulds, C. B., Fincher, G. B., et al. (2009). A Brief and Informationally Rich Naming System for Oligosaccharide Motifs of Heteroxylans Found in Plant Cell Walls. Aust. J. Chem. 62 (6), 533–537. doi:10.1071/CH08458

Fujimoto, Z., Ichinose, H., Maehara, T., Honda, M., Kitaoka, M., and Kaneko, S. (2010). Crystal Structure of an Exo-1,5-α-L-Arabinofuranosidase from Streptomyces Avermitilis Provides Insights into the Mechanism of Substrate Discrimination between Exo- and Endo-type Enzymes in Glycoside Hydrolase Family 43*. J. Biol. Chem. 285 (44), 34134–34143. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.164251

Gibson, D. G., Young, L., Chuang, R.-Y., Venter, J. C., Hutchison, C. A., Smith, H. O., et al. (2009). Enzymatic Assembly of DNA Molecules up to Several Hundred Kilobases. Nat. Methods 6 (5), 343–345. doi:10.1038/NMETH.1318

Gupta, D., and Sardar, R. (2021). “Bioinformatics of Genome Annotation,” in Bioinformatics and Human Genomics Research. Editor D. A. Forero (Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press), 7–30. doi:10.1201/9781003005926-2

Hassan, N., Kori, L. D., Gandini, R., Patel, B. K. C., Divne, C., and Tan, T. C. (2015). High-resolution Crystal Structure of a Polyextreme GH43 Glycosidase fromHalothermothrix Oreniiwith α-L-arabinofuranosidase Activity. Acta Cryst. Sect. F. 71 (3), 338–345. doi:10.1107/S2053230X15003337

Hehemann, J.-H., Smyth, L., Yadav, A., Vocadlo, D. J., and Boraston, A. B. (2012). Analysis of Keystone Enzyme in Agar Hydrolysis Provides Insight into the Degradation (Of a Polysaccharide from) Red Seaweeds. J. Biol. Chem. 287 (17), 13985–13995. doi:10.1074/jbc.M112.345645

Helbert, W., Poulet, L., Drouillard, S., Mathieu, S., Loiodice, M., Couturier, M., et al. (2019). Discovery of Novel Carbohydrate-Active Enzymes through the Rational Exploration of the Protein Sequences Space. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 6063–6068. doi:10.1073/pnas.1815791116

Herlet, J., Kornberger, P., Roessler, B., Glanz, J., Schwarz, W. H., Liebl, W., et al. (2017). A New Method to Evaluate Temperature vs. pH Activity Profiles for Biotechnological Relevant Enzymes. Biotechnol. Biofuels 10 (1), 234. doi:10.1186/s13068-017-0923-9

Holm, L., and Sander, C. (1995). Dali: a Network Tool for Protein Structure Comparison. Trends Biochem. Sci. 20 (11), 478–480. doi:10.1016/s0968-0004(00)89105-7

Hong, S., Kyung, M., Jo, I., Kim, Y.-R., and Ha, N.-C. (2018). Structure-based Protein Engineering of Bacterial β-xylosidase to Increase the Production Yield of Xylobiose from Xylose. Biochem. biophysical Res. Commun. 501 (3), 703–710. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.05.051

Inácio, J. M., Correia, I. L., and de Sá-Nogueira, I. (2008). Two Distinct Arabinofuranosidases Contribute to Arabino-Oligosaccharide Degradation in Bacillus Subtilis. Microbiology 154 (9), 2719–2729. doi:10.1099/mic.0.2008/018978-0

Johnson, E. A., Madia, A., and Demain, A. L. (1981). Chemically Defined Minimal Medium for Growth of the Anaerobic Cellulolytic Thermophile Clostridium Thermocellum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 41 (4), 1060–1062. doi:10.1128/aem.41.4.1060-1062.1981

Jumper, J., Evans, R., Pritzel, A., Green, T., Figurnov, M., Ronneberger, O., et al. (2021). Highly Accurate Protein Structure Prediction with AlphaFold. nature 596 (7873), 583–589. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03819-2

Kabsch, W. (2010). Xds. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Cryst. 66 (2), 125–132. doi:10.1107/s0907444909047337

Koeck, D. E., Ludwig, W., Wanner, G., Zverlov, V. V., Liebl, W., and Schwarz, W. H. (2015). Herbinix Hemicellulosilytica Gen. nov., Sp. nov., a Thermophilic Cellulose-Degrading Bacterium Isolated from a Thermophilic Biogas Reactor. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 65 (8), 2365–2371. doi:10.1099/ijs.0.000264

Kormelink, F. J. M., Gruppen, H., and Voragen, A. G. J. (1993). Mode of Action of (1→4)-β-D-Arabinoxylan Arabinofuranohydrolase (AXH) and |ga=l-arabinofuranosidases on Alkali-Extractable Wheat-Flour Arabinoxylan. Carbohydr. Res. 249 (2), 345–353. doi:10.1016/0008-6215(93)84099-r

Koutaniemi, S., and Tenkanen, M. (2016). Action of Three GH51 and One GH54 α-arabinofuranosidases on Internally and Terminally Located Arabinofuranosyl Branches. J. Biotechnol. 229, 22–30. doi:10.1016/j.jbiotec.2016.04.050

Krissinel, E., and Henrick, K. (2005). “Detection of Protein Assemblies in Crystals,” in Computational Life Sciences. First International Symposium, CompLife 2005, Konstanz, Germany, September 25-27, 2005, Proceedings. D. Hutchison, T. Kanade, J. Kittler, J. M. Kleinberg, F. Mattern, and C. John. Editors (Berlin: Springer), 3695, 163–174. Lecture notes in computer science Lecture notes in bioinformatics, 3695. doi:10.1007/11560500_15

Krissinel, E., and Henrick, K. (2007). Inference of Macromolecular Assemblies from Crystalline State. J. Mol. Biol. 372 (3), 774–797. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.022

Laemmli, U. K. (1970). Cleavage of Structural Proteins during the Assembly of the Head of Bacteriophage T4. nature 227 (5259), 680–685. doi:10.1038/227680a0

Li, S. (2017). “Fundamentals of Biochemical Reaction Engineering,” in Reaction Engineering. Editor S Li (Boston: Butterworth-Heinemann), 491–539. Available online at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780124104167000112. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-410416-7.00011-2

Lombard, V., Golaconda Ramulu, H., Drula, E., Coutinho, P. M., and Henrissat, B., and (2014). The Carbohydrate-Active Enzymes Database (CAZy) in 2013. Nucl. Acids Res. 42 (D1), D490–D495. doi:10.1093/nar/gkt1178

Marinus, M. G., and Løbner-Olesen, A. (2014). DNA Methylation. EcoSal Plus 6 (1), 29. doi:10.1128/ecosalplus.ESP-0003-2013

Matsuzawa, T., Kaneko, S., Kishine, N., Fujimoto, Z., and Yaoi, K. (2017). Crystal Structure of Metagenomic β-xylosidase/α-l-arabinofuranosidase Activated by Calcium. J. Biochem. 162 (3), 173–181. doi:10.1093/jb/mvx012

McCoy, A. J., Grosse-Kunstleve, R. W., Adams, P. D., Winn, M. D., Storoni, L. C., and Read, R. J. (2007). Phasercrystallographic Software. J. Appl. Cryst. 40 (Pt 4), 658–674. doi:10.1107/S0021889807021206

McIlvaine, T. C. (1921). A Buffer Solution for Colorimetric Comparison. J. Biol. Chem. 49 (1), 183–186. doi:10.1016/s0021-9258(18)86000-8

Mechelke, M., Herlet, J., Benz, J. P., Schwarz, W. H., Zverlov, V. V., Liebl, W., et al. (2017). HPAEC-PAD for Oligosaccharide Analysis-Novel Insights into Analyte Sensitivity and Response Stability. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 409 (30), 7169–7181. doi:10.1007/s00216-017-0678-y

Menzen, T. A. (2014). Temperature-induced Unfolding, Aggregation, and Interaction of Therapeutic Monoclonal Antibodies. lmu.

Miroshnichenko, M. L., Kublanov, I. V., Kostrikina, N. A., Tourova, T. P., Kolganova, T. V., BirkelandNils-Kåre, N.-K., et al. (2008). Caldicellulosiruptor Kronotskyensis Sp. Nov. And Caldicellulosiruptor Hydrothermalis Sp. nov., Two Extremely Thermophilic, Cellulolytic, Anaerobic Bacteria from Kamchatka Thermal Springs. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 58 (6), 1492–1496. doi:10.1099/ijs.0.65236-0

Musa, H. H., Ahmed, A. A., and Musa, T. H. (2018). “Chemistry, Biological, and Pharmacological Properties of Gum Arabic,” in Bioactive Molecules in Food (Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing AG), 1–18. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-54528-8_11-1

Østby, H., Hansen, L. D., Horn, S. J., Eijsink, V. G. H., and Várnai, A. (2020). Enzymatic Processing of Lignocellulosic Biomass: Principles, Recent Advances and Perspectives. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 47, 623–657. doi:10.1007/s10295-020-02301-8

Pauly, M., and Keegstra, K. (2008). Cell-wall Carbohydrates and Their Modification as a Resource for Biofuels. Plant J. 54 (4), 559–568. doi:10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03463.x

Pavic, Q., Pillot, A., Tasseau, O., Legentil, L., and Tranchimand, S. (2019). Improvement of the Versatility of an Arabinofuranosidase against Galactofuranose for the Synthesis of Galactofuranoconjugates. Org. Biomol. Chem. 17 (28), 6799–6808. doi:10.1039/c9ob01162e

Perrakis, A., Sixma, T. K., Wilson, K. S., and Lamzin, V. S. (1997). wARP: Improvement and Extension of Crystallographic Phases by Weighted Averaging of Multiple-Refined Dummy Atomic Models. Acta Cryst. D. 53 (Pt 4), 448–455. doi:10.1107/S0907444997005696

Petersen, T. N., Brunak, S., von Heijne, G., and Nielsen, H. (2011). SignalP 4.0: Discriminating Signal Peptides from Transmembrane Regions. Nat. Methods 8 (10), 785–786. doi:10.1038/nmeth.1701

Poschner, B. C., Reed, J., Langosch, D., and Hofmann, M. W. (2007). An Automated Application for Deconvolution of Circular Dichroism Spectra of Small Peptides. Anal. Biochem. 363 (2), 306–308. doi:10.1016/j.ab.2007.01.021

Pragnesh, N. D., and Ankur, G. (2018). “Chapter 3 - Natural Polysaccharide-Based Hydrogels and Nanomaterials: Recent Trends and Their Applications,” in Handbook of Nanomaterials for Industrial Applications. Editor C. M. Hussain (Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier (Micro and Nano Technologies)), 36–66. Available at: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780128133514000031.

Rainey, F. A., Donnison, A. M., Janssen, P. H., Saul, D., Rodrigo, A., Bergquist, P. L., et al. (1994). Description ofCaldicellulosiruptor Saccharolyticusgen. nov., Sp. Nov: An Obligately Anaerobic, Extremely Thermophilic, Cellulolytic Bacterium. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 120 (3), 263–266. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb07043.x

Reintjes, G., Arnosti, C., Fuchs, B. M., and Amann, R. (2017). An Alternative Polysaccharide Uptake Mechanism of Marine Bacteria. Isme J. 11 (7), 1640–1650. doi:10.1038/ismej.2017.26

Robinson, R., Causey, J., and Slavin, J. L. (2008). “38 Nutritional Benefits of Larch Arabinogalactan,” in Advanced Dietary Fibre Technology. Editors B. McCleary, and L. Prosky (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons), 443.

Rodger, A. (2018). “Far UV Protein Circular Dichroism,” in Encyclopedia of Biophysics (Springer Nature), 1–6. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-35943-9_634-1

Seiboth, B., and Metz, B. (2011). Fungal Arabinan and L-Arabinose Metabolism. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 89 (6), 1665–1673. doi:10.1007/s00253-010-3071-8

Sørensen, H. R., Jørgensen, C. T., Hansen, C. H., Jørgensen, C. I., Pedersen, S., and Meyer, A. S. (2006). A Novel GH43 α-L-arabinofuranosidase from Humicola Insolens: Mode of Action and Synergy with GH51 α-L-arabinofuranosidases on Wheat Arabinoxylan. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 73 (4), 850–861. doi:10.1007/s00253-006-0543-y

Stelzer, W., Poschner, B. C., Stalz, H., Heck, A. J., and Langosch, D. (2008). Sequence-specific Conformational Flexibility of SNARE Transmembrane Helices Probed by Hydrogen/deuterium Exchange. Biophysical J. 95 (3), 1326–1335. doi:10.1529/biophysj.108.132928

Tagawa, K., and Kaji, A. (1969). Preparation of L-Arabinose-Containing Polysaccharides and the Action of an α-l-arabinofuranosidase on These Polysaccharides. Carbohydr. Res. 11 (3), 293–301. doi:10.1016/S0008-6215(00)80570-4

Tefsen, B., Lagendijk, E. L., Park, J., Akeroyd, M., Schachtschabel, D., Winkler, R., et al. (2012). Fungal α-arabinofuranosidases of Glycosyl Hydrolase Families 51 and 54 Show a Dual Arabinofuranosyl- and Galactofuranosyl-Hydrolyzing Activity. Biol. Chem. 393 (8), 767–775. doi:10.1515/hsz-2012-0134

Vagin, A. A., Steiner, R. A., Lebedev, A. A., Potterton, L., McNicholas, S., Long, F., et al. (2004). REFMAC5 Dictionary: Organization of Prior Chemical Knowledge and Guidelines for its Use. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Cryst. 60 (Pt 12 Pt 1), 2184–2195. doi:10.1107/S0907444904023510

van den Broek, L. A. M., Lloyd, R. M., Beldman, G., Verdoes, J. C., McCleary, B. V., and Voragen, A. G. J. (2005). Cloning and Characterization of Arabinoxylan Arabinofuranohydrolase-D3 (AXHd3) from Bifidobacterium Adolescentis DSM20083. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 67 (5), 641–647. doi:10.1007/s00253-004-1850-9

van Laere, K. M. J., Voragen, C. H. L., Kroef, T., van den Broek, L. A. M., Beldman, G., and Voragen, A. G. J. (1999). Purification and Mode of Action of Two Different Arabinoxylan Arabinofuranohydrolases from Bifidobacterium Adolescentis DSM 20083. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 51 (5), 606–613. doi:10.1007/s002530051439

Vandermarliere, E., Bourgois, T. M., Winn, M. D., van Campenhout, S., Volckaert, G., Delcour, J. A., et al. (2009). Structural Analysis of a Glycoside Hydrolase Family 43 Arabinoxylan Arabinofuranohydrolase in Complex with Xylotetraose Reveals a Different Binding Mechanism Compared with Other Members of the Same Family. Biochem. J. 418 (1), 39–47. doi:10.1042/BJ20081256

Wang, W., Mai-Gisondi, G., Stogios, P. J., Kaur, A., Xu, X., Cui, H., et al. (2014). Elucidation of the Molecular Basis for Arabinoxylan-Debranching Activity of a Thermostable Family GH62 α- L -Arabinofuranosidase from Streptomyces Thermoviolaceus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 80 (17), 5317–5329. doi:10.1128/aem.00685-14

Williams, C. J., Headd, J. J., Moriarty, N. W., Prisant, M. G., Videau, L. L., Deis, L. N., et al. (2018). MolProbity: More and Better Reference Data for Improved All-Atom Structure Validation. Protein Sci. 27 (1), 293–315. doi:10.1002/pro.3330

Wood, T. M., and Bhat, K. M. (1988). “Methods for Measuring Cellulase Activities,” in Methods in Enzymology (Elsevier), 160, 87–112. doi:10.1016/0076-6879(88)60109-1

Xu, W.-Z., Shima, Y., Negoro, S., and Urabe, I. (1991). Sequence and Properties of Beta-Xylosidase from Bacillus Pumilus IPO. Contradiction of the Previous Nucleotide Sequence. Eur. J. Biochem. 202 (3), 1197–1203. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1991.tb16490.x

Keywords: β-D-galactofuranosidase, α-L-arabinofuranosidase, glycoside hydrolase family GH159, thermophilic, Caldicellulosiruptor, crystallographic structure analysis, five-bladed beta propeller, active site

Citation: Baudrexl M, Fida T, Berk B, Schwarz WH, Zverlov VV, Groll M and Liebl W (2022) Biochemical and Structural Characterization of Thermostable GH159 Glycoside Hydrolases Exhibiting α-L-Arabinofuranosidase Activity. Front. Mol. Biosci. 9:907439. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2022.907439

Received: 29 March 2022; Accepted: 06 June 2022;

Published: 29 June 2022.

Edited by:

Tian Liu, Dalian University of Technology, ChinaReviewed by:

Anastassios C. Papageorgiou, University of Turku, FinlandCopyright © 2022 Baudrexl, Fida, Berk, Schwarz, Zverlov, Groll and Liebl. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wolfgang Liebl, d2xpZWJsQHR1bS5kZQ==

†Present address: Tarik Fida, Pharmaceutical Institute, Pharmaceutical Biology, Eberhard Karls University of Tübingen, Tuebingen, Germany Wolfgang H. Schwarz, Aspratis GmbH, München, Germany

‡Deceased

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.