95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Microbiol. , 28 February 2025

Sec. Microbial Physiology and Metabolism

Volume 16 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2025.1547950

Oxalate decarboxylase (OxdC) is an enzyme that degrades oxalic acid and may affect the virulence of necrotrophic fungal pathogens that rely on oxalic acid as a pathogenicity factor. However, the biological function of OxdCs in hemibiotropic fungi is still unknown. Our previous studies revealed four OxdC-encoding genes in the whole genome, with CsOxdC3 playing important roles in morphosporogenesis, fungicide resistance and virulence in Colletotrichum siamense. Here, we systematically analyzed the biological functions of four oxalate decarboxylase genes in C. siamense via a loss-of-function method. The results revealed CsOxdC1, CsOxdC2, and CsOxdC4 played major roles in degrading oxalic acid in C. siamense, whereas CsOxdC3 did not. All four CsOxdCs positively modulated morphosporogenesis, including vegetative growth, conidial size, conidial germination rate and the appressorium formation rate, to different extents. In particular, the CsOxdC3 deletion mutant failed to form appressoria. The four OxdC gene deletion mutants had different responses to Mn2+, Cu2+, and multiple fungicides. Among them, CsOxdC2 and CsOxdC4 exhibited positive roles in resistance to Mn2+ and Cu2+ stresses; CsOxdC1 played a slightly positive role in C. siamense resistance to azole fungicides; and CsOxdC3 had a significantly positive role in regulating the sensitivity of C. siamense to multiple fungicides, including pyrrole and azole, but not CsOxdC2 and CsOxdC4. Furthermore, compared with the wild-type strain, ΔCsOxdC2 and ΔCsOxdC3, but not ΔCsOxdC1 and ΔCsOxdC4, displayed significantly reduced virulence. In conclusion, our data indicated that CsOxdCs exerted diverse functions in morphogenesis, stress homeostasis, fungicide resistance, and virulence in C. siamense. This study provides insights into the biological function of OxdCs in the hemibiotrophic fungus C. siamense.

Colletotrichum is one of the most common and important genera of filamentous fungal plant pathogens, comprising nine core clades with 15 major species complexes and 252 species (Khodadadi et al., 2023). Species of Colletotrichum employ diverse strategies for invading host tissue, ranging from intracellular hemibiotrophy to subcuticular intramural necrotrophy (Perfect et al., 1999). Colletotrichum spp. can cause anthracnose spots and blights in various economically important crops, especially fruits, vegetables and ornamentals (Dean et al., 2012). C. siamense, a member of the C. gloeosporioides species complex, is the dominant pathogen species in rubber tree, mango, litchi, and other tropical crops in the field (Liu et al., 2018; Ling et al., 2019; Qin et al., 2019). Colletotrichum has a long and distinguished history as a model pathogen for fundamental, biochemical, physiological and genetic studies (Dean et al., 2012). In recent years, although some functional genes of Colletotrichum have been characterized, additional genes related to pathogenicity and drug resistance need to be discovered to understand the pathogenesis of Colletotrichum and control the disease.

Oxalic acid (OA) is a natural organic acid with a low molecular weight and is an important metabolic product that is widely present in plants, animals, and microorganisms (Dutton and Evans, 1996; Grąz, 2024). It has strong acidity, reductivity, and the ability to chelate calcium (Dutton and Evans, 1996). Fungi can synthesize and secrete OA to maintain a suitable pH in their living environment (Dutton and Evans, 1996). OA is remarkably multifunctional in fungi and plays significant biological and pathological roles in the life cycle and infection processes, particularly in necrotrophic fungi. It can acidify the host tissue environment, participate in cell wall degradation, and induce reactive oxygen species production (Rollins and Dickman, 2001; Kim et al., 2008; Williams et al., 2011; Tian et al., 2021).

OA can be degraded by enzymes via decarboxylation or oxidation (Grąz, 2024). The enzymes involved in the biological degradation of OA in the biosphere include oxalyl-CoA decarboxylase, oxalate oxidase, and oxalate decarboxylase (Kumar et al., 2019). Among these enzymes, oxalate decarboxylase (OxdC), which is a manganese-dependent enzyme that can directly degrade OA into formic acid and CO2 without additional cofactors, is widely present in bacteria and fungi (Kumar et al., 2019). OxdCs belong to the bicupin protein family, which is widely involved in various life processes, including growth, development, and responses to environmental stress (Kathiara et al., 2000; Kesarwani et al., 2000; Chowdhury et al., 2024). Owing to the high specificity of OxdCs for their substrates and the high efficiency of their enzymatic reactions, some OxdCs have been extensively studied and successfully applied in agriculture, food, and other fields. In agricultural fields, OxdCs are often utilized for plant disease control. For example, tobacco, tomato, and lettuce harboring the OxdC genes from Trametes versicolor, Collybia velutipes, and Flammulina sp. have been shown to effectively defend against Sclerotinia infections (Kesarwani et al., 2000; Dias et al., 2006; Walz et al., 2008). Transgenic tomato expressing an OxdC gene from F. velutipes increased survival to Moniliophthora perniciosa (Pereira et al., 2022). Transgenic rice expressing an OxdC gene from Bacillus subtilis presented increased resistance to rice blast and rice sheath blight (Qi et al., 2017). Most studies on OxdCs focus on their enzyme activity and potential applications. However, the biological function of OxdCs in fungi has not been well characterized.

Some OxdCs have been characterized in plant pathogenic fungi, including S. sclerotiorum, T. ochracea, T. versicolor, Postia placenta, Gleophylum trabeum, Serpula lacrymans, and Coniothyrium minitans (Micales, 1997; Mäkelä et al., 2002; Grąz et al., 2011; Hastrup et al., 2012; Liang et al., 2015a; Liang et al., 2015b). Many studies have shown that multiple OxdCs exist, with diverse expression patterns and functions across different fungi. Currently, three expression patterns of oxalate decarboxylase genes have been identified: (1) inducible by OA and pH, such as the OxdC genes in C. velutipes and Aspergillus niger (Azam et al., 2002); (2) inducible solely by oxalate anions, as observed in the OxdC of the brown rot fungus (P. placenta) (Micales, 1997); and (3) not inducible by pH or OA, as observed in S. sclerotiorum with its Ss-odc1 and Ss-odc2 genes (Liang et al., 2015b). Different gene expression patterns suggest that OxdCs may have various functions. The biological functions of different OxdCs vary within the same fungi. For example, two OxdC genes have been identified in S. sclerotiorum, with only Ss-Oxdc2 playing a role in oxalate degradation (Kabbage et al., 2013). In C. minitans, three OxdCs were analyzed, which revealed the involvement of CmOxdC1 and CmOxdC3 in OA degradation and their parasitic ability of C. minitans against host fungi; in contrast, CmOxdC2 did not play a role in this process (Zeng et al., 2014; Xu et al., 2022). The OxdCs involved in plant pathogenicity are mainly necrotrophic fungi. Little is known about the biological function of OxdCs in hemibiotrophic or biotrophic fungi.

In our previous study, we identified four OxdC-encoding genes in the whole genome of C. siamense. We characterized the function of CsOxdC3, which interacts with CsPbs2 (a mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase) and is involved in morphogenesis, stress homeostasis, fungicide resistance, and virulence in C. siamense (Lu et al., 2024). In this study, we further investigated the functions of three other oxalate decarboxylase genes in C. siamense by comparing the phenotypes of the gene deletion mutants and wild-type strains. We found that all four CsOxdCs were involved in the growth and development of C. siamense, with differential regulation observed in terms of spore germination, sporulation, and appressorium formation. CsOxdCs were induced to varying degrees by OA and exhibited different levels of tolerance to OA. Enzyme activity assays revealed that CsOxdC1, CsOxdC2, and CsOxdC4 possessed oxalate decarboxylase activity, whereas CsOxdC3 had the weakest oxalate degradation ability. Additionally, the four CsOxdCs presented diverse responses to stress homeostasis, fungicide resistance, and virulence. Our research on the oxalate decarboxylase family in C. siamense, covering aspects such as morphogenesis, stress homeostasis, fungicide resistance, and virulence, indicates that CsOxdCs have diverse functions and may operate through different pathways in C. siamense.

The HN08 strain C. siamense from rubber trees was used as the wild-type (WT) strain. In this study, HN08 served as the starting strain to construct the gene deletion mutants ΔCsOxdC1, ΔCsOxdC2, and ΔCsOxdC4 and the complementary mutants CΔCsOxdC1, CΔCsOxdC2, and CΔCsOxdC4. The construction of ΔCsOxdC3 and CΔCsOxdC3 (equivalent to ΔCsOxdC3/CsOxdC3) has been described in our previous study (Lu et al., 2024). The methods for constructing mutants and complementary strains have been detailed in a previous study (Liu et al., 2023; Lu et al., 2024). The gene deletion diagram and primers for PCR conformation are listed in Supplementary Figure S1. For spore collection, the strains were grown on potato dextrose agar (PDA: 20 g/L potato, 20 g/L glucose, and 18 g/L agar) in Petri dishes for 3 days, after which the hyphae were scraped off and inoculated into liquid potato dextrose medium (PD, PDA without agar) with shaking at 150 rpm and 28°C for 3–5 days, after which large numbers of spores were harvested with ddH2O for preparation of the spore suspension. DNA, RNA and total proteins were extracted from mycelial strains cultured in liquid complete medium (CM: 0.6% yeast extract, 0.1% casein hydrolysate, and 1% sucrose) with shaking at 150 rpm and 28°C for 3–5 days.

The expression of the CsOxdC genes was analyzed via qRT–PCR. The final concentrations of OA were 0 and 6 mM in complete medium. HN08, ∆CsOxdCs and C∆CsOxdCs were cultured in this medium for 2–3 days. Total RNA was extracted using the SteadyPure Plant RNA Extraction Kit (Accurate, China), and the RNA was reverse-transcribed into cDNA using the EvoM-MLV RT Mix Kit with gDNA Clean for qRT-PCR (Accurate, China). Two-step qRT–PCR (TOLOBIO, China) was used to compare the expression levels of the CsOxdC genes after 0 and 6 mM OA treatment. All primers used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

A total of 10 μL of the spore suspensions of HN08, ∆CsOxdCs and C∆CsOxdCs at a concentration of 105 conidia/mL were inoculated onto CM plates containing 0, 3, 6, 12, and 24 mM OA. Bromophenol blue was added to the media at 0.001% (w/v) as a pH indicator to monitor the pH changes caused by fungal growth. After incubation in the dark at 28°C, the colony diameter was measured, and the color of the media was observed and photographed after 5 days. The experiment was repeated three times. The inhibition rate was calculated using the following formula: inhibition rate (%) = [colony diameter (control group - treatment group)]/[colony diameter (control group)] × 100.

Spore suspensions of HN08, ∆CsOxdCs, and C∆CsOxdCs at the same concentration were inoculated into PD medium containing 12 mM OA. The OA contents in the medium at 0, 12 and 24 h were detected and recorded using an OA content detection kit (BOXNIO, China).

Spore suspensions of HN08 and ∆CsOxdCs at the same concentration were cultured in PD medium, and total protein was extracted using a Protein Extraction Kit (BestBio, China). The level of OxdC activity in C. siamense was detected using a colorimetry assay in accordance with the instructions supplied with the Oxalate Decarboxylase Activity Assay Kit (Mmbio, China). Briefly, OxdC activity was determined by generating a colorimetric product with absorbance at 450 nm (A450), proportional to the enzymatic activity present. One unit of oxalate decarboxylase was the amount of enzyme required to generate 1.0 mM formate per minute at pH 5 and 37°C.

A total of 10 μL of the spore suspensions of HN08, ∆CsOxdCs and C∆CsOxdCs at a concentration of 105 conidia/mL were inoculated onto CM plates. The growth rate of the individual colonies was assessed 5 days postinfection (dpi) at 28°C. To measure conidial germination, the number of spores and appressorial formation, 10 μL of 105 conidia/mL spore suspension preparations was dropped onto hydrophobic slides and incubated at 28°C according to a previous study (Song et al., 2022). The rate of spore germination at 0, 2, 4, 6 and 8 h and the rate of appressorium formation at 12 h post inoculation (hpi) was recorded. At least three hundred spores were tested, and three independent experiments were performed.

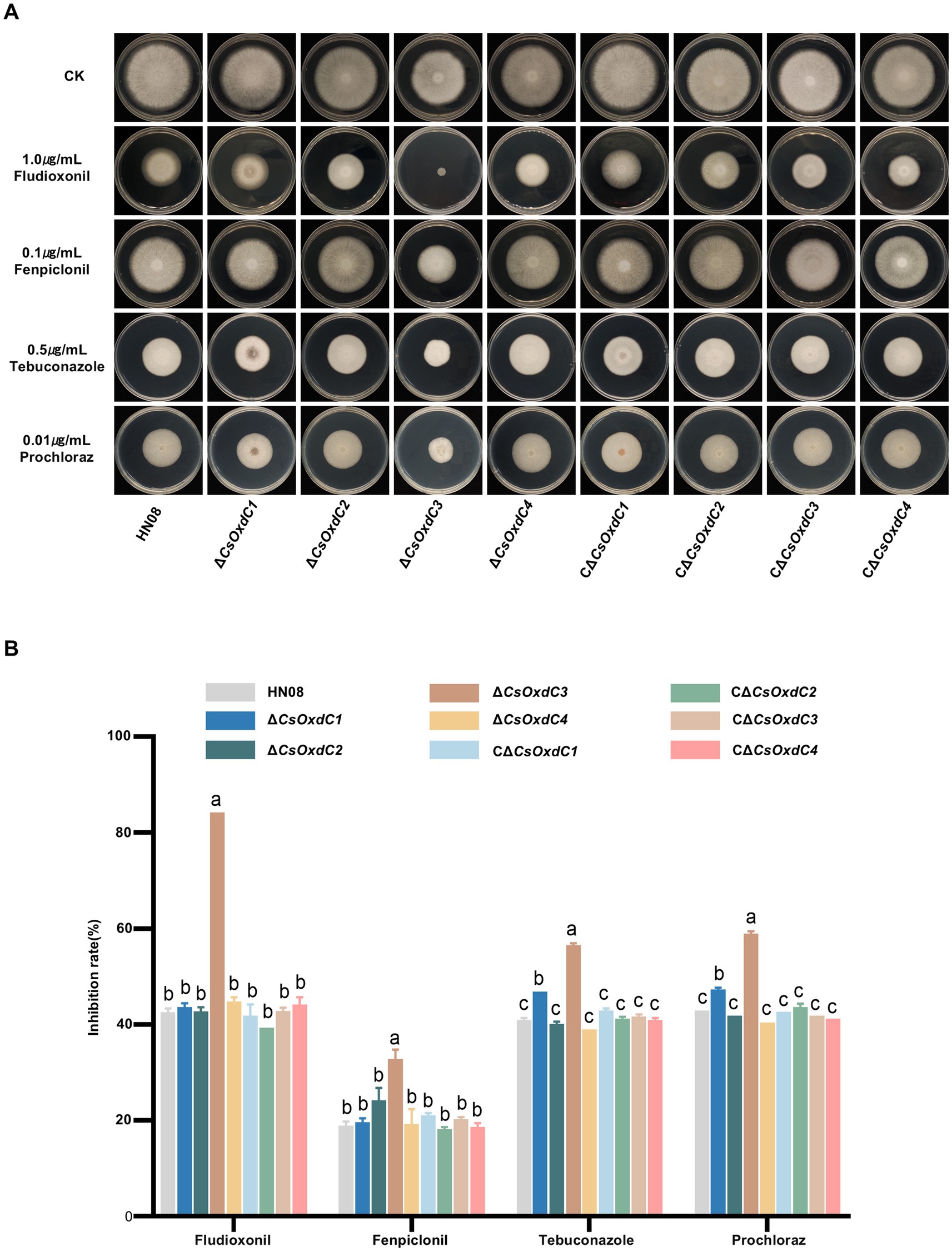

The stress responses of the HN08, ΔCsOxdCs, and CΔCsOxdCs strains were examined by inoculating 10 μL of the 105 conidia/mL conidial suspension from the gene deletion mutants, WT (HN08), and complementation strains on CM media supplemented with different chemical materials, including 10 mM Mn2+, 6 mM Cu2+, 1.0 μg/mL fludioxonil, 0.1 μg/mL fenpiclonil, 0.5 μg/mL tebuconazole and 0.01 μg/mL prochloraz, and culturing the samples at 28°C. The colony diameter was measured, and the colonies were photographed at 5 dpi. The growth inhibition rate was calculated using the following formula: inhibition rate (%) = [colony diameter (control group - treatment group)]/[colony diameter (control group)] × 100.

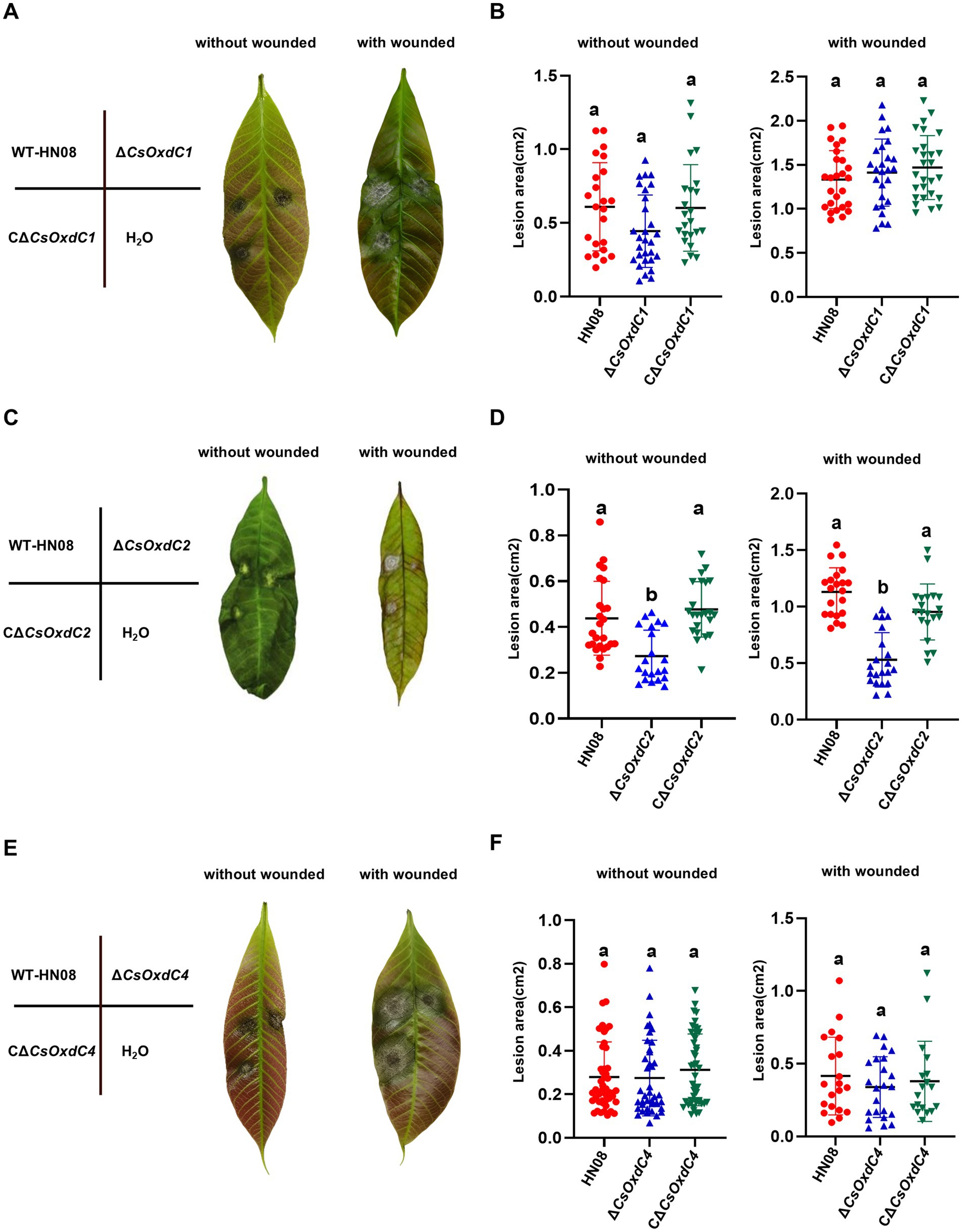

Pathogenicity assessment was performed via drop inoculation of intact and injured tender leaves that had been detached from rubber trees with 10 μL of spore suspension (1 × 105 conidia/mL) prepared with spores obtained from the individual strains. Three biological replicates were assayed, and 30 leaves were inoculated for each treatment. The diseased lesions were measured and photographed at 5 dpi.

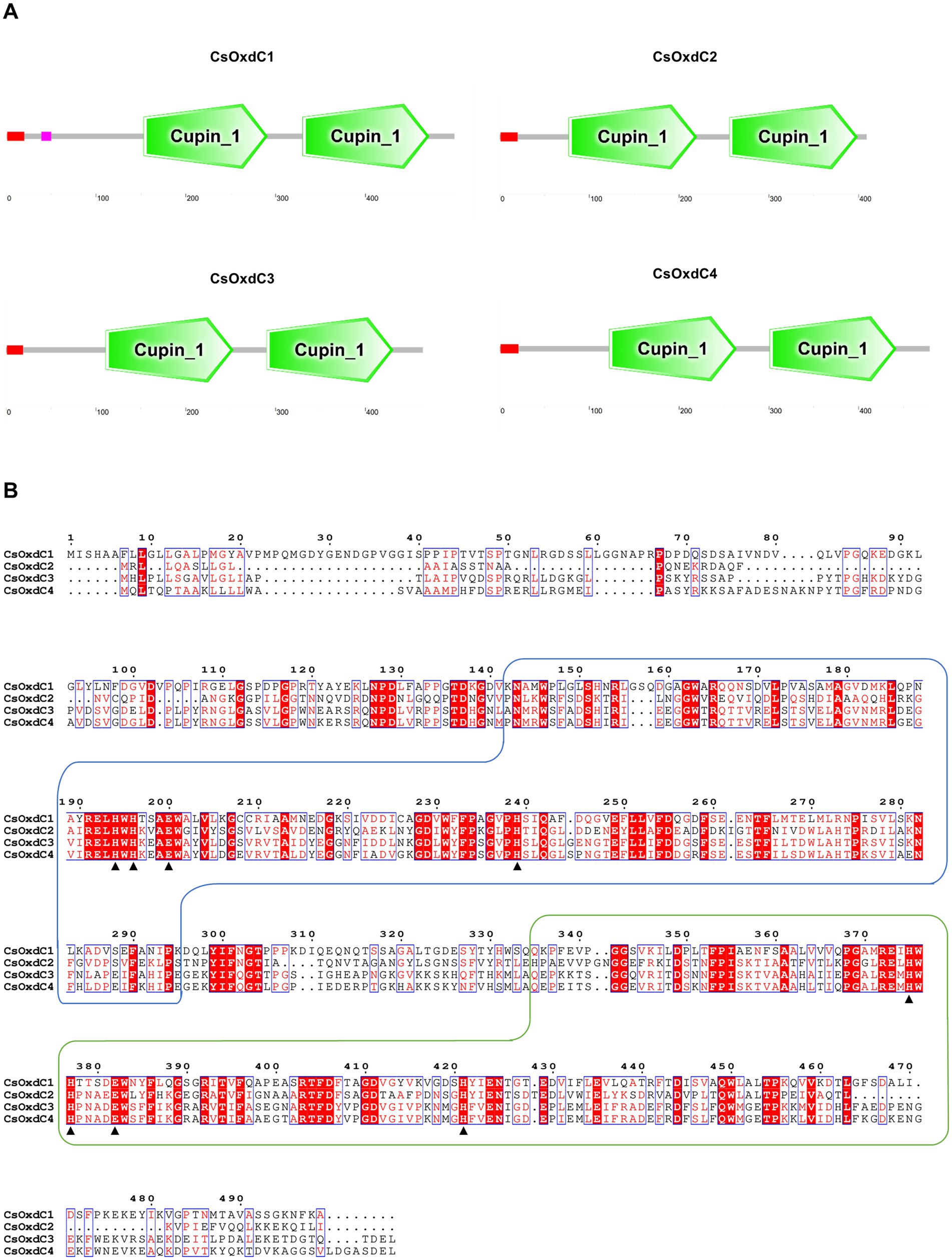

In our previous study, we identified four oxalate decarboxylase coding genes in C. siamense and characterized the biological function of the CsOxdC3 gene among them (Lu et al., 2024). Here, we cloned and analyzed the remaining three oxalate decarboxylase genes in C. siamense. Sequence analyses revealed that the CsOxdC1 gene had a DNA size of 1750 bp and contained 4 introns and 5 exons encoding 499 amino acids. The CsOxdC2 gene was 1,568 bp in length and contained 7 introns and 8 exons, encoding 409 amino acids in total. The CsOxdC4 gene consisted of 1,684 bp with 2 introns, encoding a total of 479 amino acids. SMART analysis revealed that all four CsOxdC proteins had two Cupin_1 domains containing Mn2+-binding sites and a signal peptide at the N-terminus (Figure 1). CsOxdC1 also contained a low-complexity domain sequence (Figure 1A). Comparative analysis of the amino acid sequences revealed that CsOxdC1 and CsOxdC2 had low homology (less than 40%) with the other proteins, whereas CsOxdC3 and CsOxdC4 shared 76.41% homology (Figure 1B). This finding was consistent with previous phylogenetic analyses, which grouped OxdCs from fungi into five clades (A to E). CsOxdC3 and CsOxdC4 belonged to Clade A, CsOxdC1 belonged to Clade D, and CsOxdC2 belonged to Clade E in C. siamense (Lu et al., 2024).

Figure 1. Protein domain and amino acid sequence analysis of the four members of CsOxdCs family in C. siamense. (A) SMART analysis of the four CsOxdC proteins. (B) The amino acid sequence alignment of four CsOxdC proteins. The two wireframes are the Cupin_1 domain; the red area is the conserved motif; ▲indicate amino acid residues for Mn2+-binding site. The sequences were aligned with Clustal X and analyzed using Espript3.0.

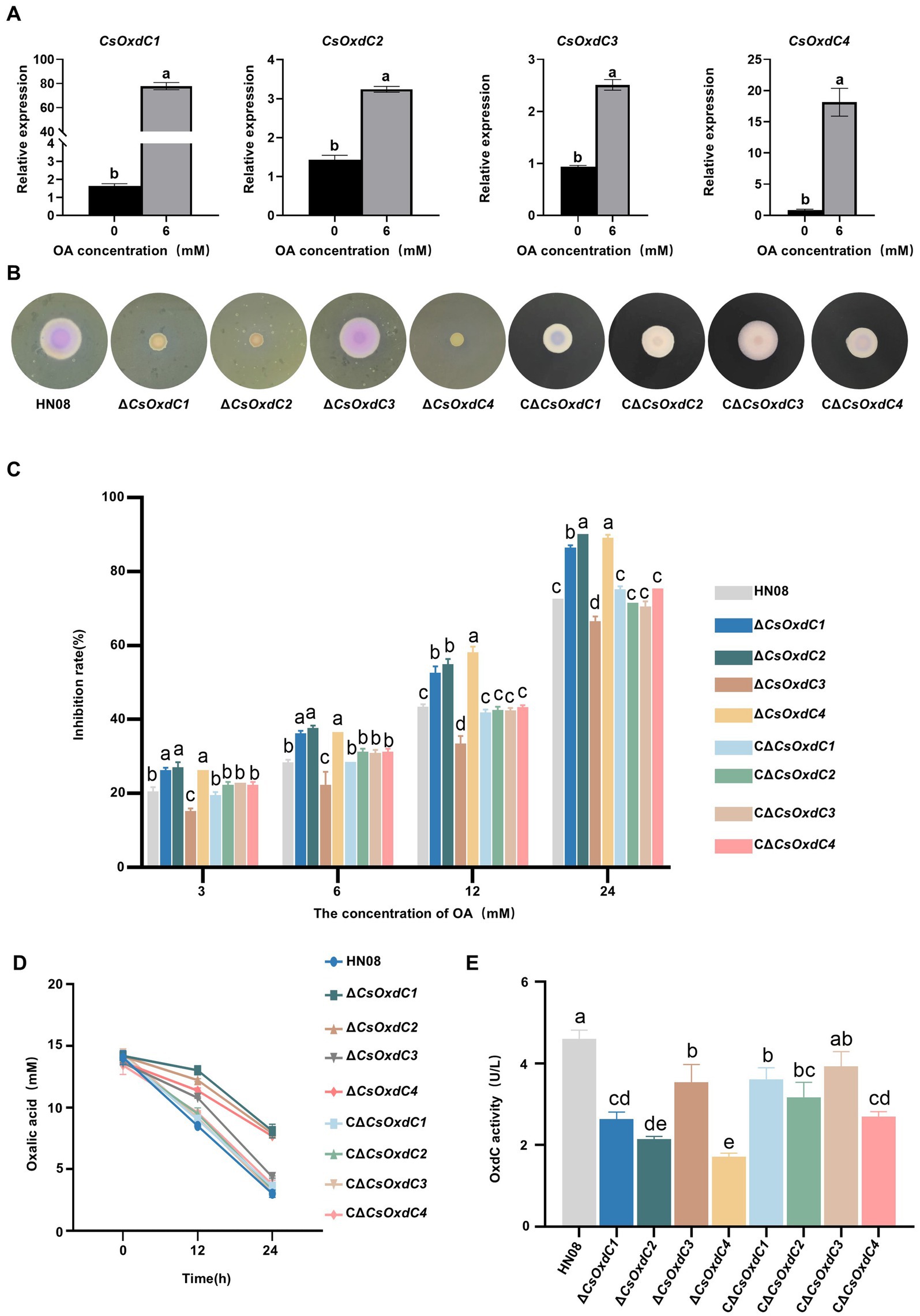

Considering that OxdCs are enzymes that can directly degrade OA into formic acid and CO2 without additional cofactors (Kumar et al., 2019), we investigated whether these four OxdCs had oxalate decarboxylase enzyme activity in C. siamense. First, we evaluated whether the expression of the four CsOxdC genes was induced by 6 mM OA (Figure 2A). The results showed that the expression levels of the four CsOxdC genes were significantly elevated compared with the control, with CsOxdC1 expression reaching a 76.38-fold increase, CsOxdC2 expression reaching a 3.24-fold increase, CsOxdC3 expression reaching a 2.51-fold increase, and CsOxdC4 expression reaching a 18.13-fold increase (Figure 2A). These results demonstrated that the expression of the four CsOxdC genes was upregulated by OA induction, with varying degrees of upregulation among the different genes.

Figure 2. Gene expression and oxalate decarboxylase activities of the four CsOxdC members in C. siamense. (A) Effect of OA on gene expression of CsOxdCs family in C. siamense. (B) Colony size and medium color of the cultures of the tested strains on CM supplemented with bromophenol blue and 24 mM OA. (C) Growth inhibition rate of the tested strains under different concentrations of OA stress. (D) Content of OA in medium of the tested strains cultured at 0, 12 and 24 hpi. (E) The oxalate decarboxylase activities of the tested strains after being cultured in PD medium for 2 dpi. Different letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05, according to one-way ANOVA and Duncan’s test), and the error bars represent the standard deviations.

The CsOxdCs-deficient strains (ΔCsOxdC1, ΔCsOxdC2, ΔCsOxdC3, and ΔCsOxdC4, collectively named ΔCsOxdCs) were subsequently constructed by replacing each CsOxdCs gene with the ILV1 gene (the sulfonylurea resistant gene) (Sweigard et al., 1997), which was confirmed via PCR amplification and sequencing. The complementary strains CΔCsOxdCs (CΔCsOxdC1, CΔCsOxdC2, CΔCsOxdC3, and CΔCsOxdC4, also named CΔCsOxdCs) were also constructed and identified by PCR confirmation (Supplementary Figure S1). The effects of CsOxdCs on tolerance to OA were tested by growing the ΔCsOxdCs mutants, CΔCsOxdCs and WT strains on CM supplemented with OA at five concentrations (0, 3, 6, 12 and 24 mM). Since medium containing bromothymol blue acts as a pH indicator, changing color from blue to yellow upon the addition of OA (Zeng et al., 2014), we compared the intensity of the colony color shift between the four mutants and the WT at different OA concentrations (Figure 2B and Supplementary Figure S2). Notably, the color of the media colonized by ΔCsOxdC1, ΔCsOxdC2, and ΔCsOxdC4 remained yellow, whereas that colonized by the WT and ΔCsOxdC3 turned pink at 24 mM, indicating that ΔCsOxdC1, ΔCsOxdC2, and ΔCsOxdC4 have lost the ability to degrade OA to some extent compared with WT and ΔCsOxdC3. Although the color of the complementation mutants CΔCsOxdCs did not completely match that of the WT, which may be due to the reintroduced genes only partially restored the phenotype (Figure 2B). The growth inhibition rates of the ΔCsOxdC1, ΔCsOxdC2, and ΔCsOxdC4 mutants were significantly greater than those of the WT strain under various concentrations of OA. In contrast, the growth inhibition rates of ΔCsOxdC3 were significantly lower than those of the WT (Figures 2B,C). Additionally, the growth rates of the complementation mutants CΔCsOxdCs did not significantly differ from those of the WT (Figure 2C). Both the colony color and growth inhibition data suggested that the primary OA-degrading genes of this family were CsOxdC1, CsOxdC2 and CsOxdC4 but not CsOxdC3 in C. siamense.

Furthermore, a reduction in the OA concentration was observed in the culture solutions of the four mutants and WT initially 12 mM OA added (Figure 2D). The reducing levels of ΔCsOxdC1, ΔCsOxdC2, and ΔCsOxdC4 were similar. The most significant decrease in OA was observed in the WT and ΔCsOxdC3 strains at 24 h, indicating that CsOxdC3 was not the primary gene responsible for OA degradation in this family. To verify the OA-degrading ability of the four CsOxdC genes, we analyzed the enzyme activity of the four gene deletion mutants (Figure 2E). The results revealed that the oxalate decarboxylase activities of the WT and ΔCsOxdC3 strains were similar, while the enzyme activities of ΔCsOxdC1, ΔCsOxdC2, and ΔCsOxdC4 were significantly decreased compared with the WT strain (Figure 2E). Taken together, these data indicated that CsOxdC1, CsOxdC2, and CsOxdC4 played major roles in degrading OA in C. siamense, whereas CsOxdC3 did not.

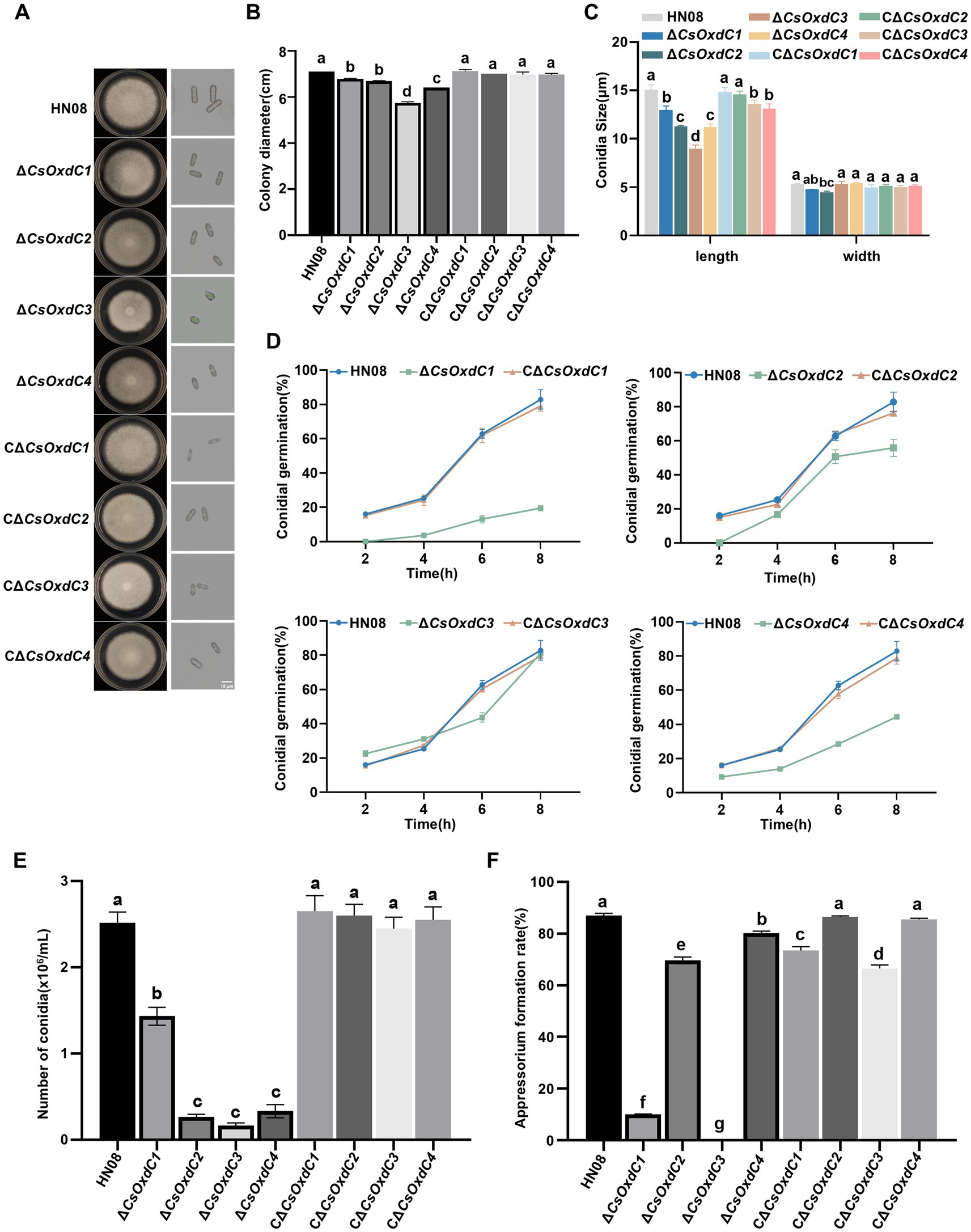

To characterize the role of CsOxdCs in the vegetative growth and morphological development of C. siamense, we examined the radial growth and colony morphology of HN08, ΔCsOxdCs, and CΔCsOxdCs cultured on minimal medium. Compared with the HN08 and complemented strains, the ΔCsOxdCs strains displayed a significant reduction in colony diameter (Figures 3A,B). Notably, ΔCsOxdC3 exhibited the greatest reduction in colony diameter with a 19.30% reduction. The colony diameters of the ΔCsOxdC1, ΔCsOxdC2 and ΔCsOxdC4 mutants were reduced by 4.51, 5.92 and 9.86%, respectively (Figures 3A,B). These results indicated that the CsOxdCs family significantly influenced the colony growth of C. siamense, but the influence is relatively minor.

Figure 3. Effects of four CsOxdC genes on the growth and development of C. siamense. (A) Colony phenotype and conidia morphology of the tested strains cultured for 5 dpi. (B) Colony diameter of the tested strains. (C) Conidial size of the tested strains. (D) Conidial germination rates of the tested strains at 2, 4, 6 and 8 hpi. (E) Conidial number of the tested strain. (F) Appressorial formation rates of the tested strains. Different letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05, according to one-way ANOVA and Duncan’s test), and the error bars represent the standard deviations.

The conidial size, conidial germination rate, sporulation rate, and appressorium formation rates of the four mutants and the WT strain were also measured. The conidial sizes of the ΔCsOxdC1, ΔCsOxdC2, ΔCsOxdC3, and ΔCsOxdC4 strains were (12.97 ± 0.34) × (4.77 ± 0.01) μm, (11.31 ± 0.05) × (4.46 ± 0.11) μm, (8.97 ± 0.32) × (5.31 ± 0.25) μm, and (11.21 ± 0.27) × (5.40 ± 0.04) μm, respectively, whereas that of the WT strain was (15.06 ± 0.42) × (5.3 ± 0.06) μm (Figures 3A,C). Data analyses revealed that the conidial lengths of the four gene deletion mutants were obviously shortened. The conidial germination rates of the ΔCsOxdC1, ΔCsOxdC2, and ΔCsOxdC4 mutants were consistently lower than those of the WT from 2 to 8 hpi, whereas the rate of ∆CsOxdC3 was lower than that of the WT at 6 h but was similar to that of the WT at 8 hpi (Figure 3D). The sporulation of ∆CsOxdC1 (1.43 × 106 conidia/mL, 43.25% decrease in conidiation), ∆CsOxdC2 (0.27 × 106 conidia/mL, 89.29% decrease in conidiation), ∆CsOxdC3 (0.17 × 106 conidia/mL, 93.25% decrease in conidiation), and ∆CsOxdC4 (0.33 × 106 conidia/mL, 86.90% decrease in conidiation) was significantly lower than that of the WT strain (2.52 × 106 conidia/mL) (Figure 3E). Additionally, the appressorium formation rates were also assessed, which were 87.06% at 12 hpi in WT compared with 10.07, 69.67%, 0, and 80.09% ∆CsOxdC1, ∆CsOxdC2, ∆CsOxdC3, and ∆CsOxdC4, respectively (Figure 3F). These results indicated that ∆CsOxdCs decreased the appressorium formation rate at 12 h, with ∆CsOxdC1 and ∆CsOxdC3 having the greatest impact. These data, coupled with the phenotypic recovery observed in the complementary strains (CΔCsOxdCs), supported the conclusion that four CsOxdCs positively regulated the vegetative growth, conidial morphology, conidial germination rate and appressorium formation rate, but each gene affected them to different extents in C. siamense.

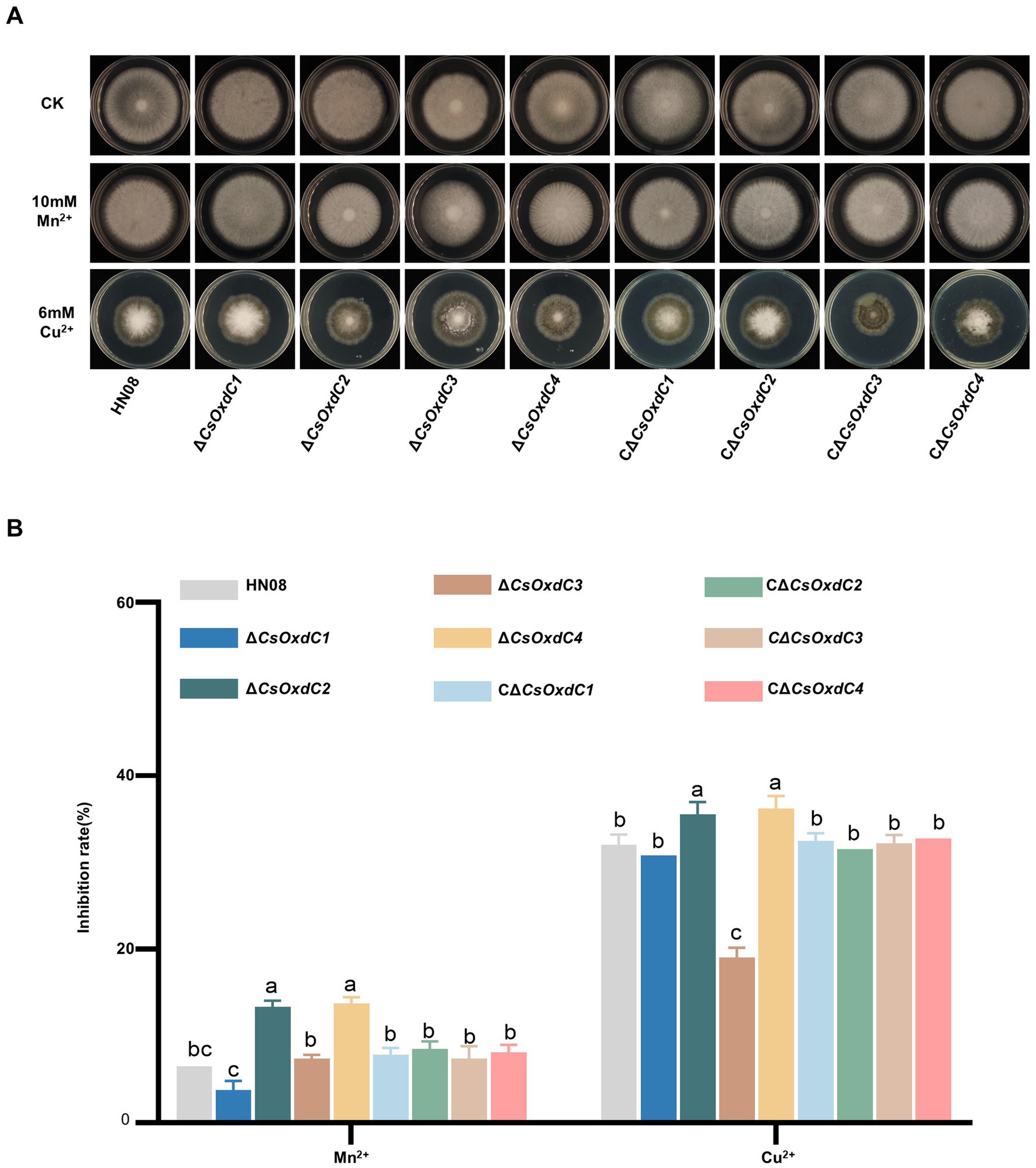

OxdCs act as manganese-containing polymerases and belong to the cupin superfamily (Mäkelä et al., 2010; Chowdhury et al., 2024), we investigated the contributions of the CsOxdCs gene to Mn2+ and Cu2+ stresses. The colony diameters of HN08, ΔCsOxdCs, and CΔCsOxdCs on CM plates containing 10 mM Mn2+ and 6 mM Cu2+ were measured, and the inhibition rates were calculated (Figures 4A,B). Under Mn2+ stress, the inhibition rates of ΔCsOxdC2 and ΔCsOxdC4 were 13.37 and 13.77%, respectively, both of which were significantly greater than that in WT (6.53%). There were no significant differences between ΔCsOxdC1 and HN08 or between ΔCsOxdC3 and HN08 (Figure 4B). These findings indicated that the CsOxdC2 and CsOxdC4 genes were involved in the response to Mn2+ stress. Under Cu2+ stress, the inhibition rates of ΔCsOxdC2 (35.56%) and ΔCsOxdC4 (36.23%) were greater than that of WT (32.01%), whereas that of ΔCsOxdC3 (19.04%) was lower than that of WT (Figure 4B). These findings indicated that CsOxdC2 and CsOxdC4 played positive roles in the regulation of C. siamense resistance to Cu2+ stress, whereas CsOxdC3 had an opposite role. Taken together, these data suggested that four CsOxdC genes played diverse roles in the stress response of C. siamense to Mn2+ and Cu2+ stresses.

Figure 4. Comparison of responses to various stresses among WT (HN08), ΔCsOxdCs and CΔCsOxdCs. (A) Mycelial growth of the tested strains on CM supplemented with 10 mM Mn2+ and 6 mM Cu2+ for 5 dpi. (B) Growth inhibition rates of the tested strains under different stresses. The growth inhibition rate is relative to the growth rate of each untreated control. Three repeats were performed. The error bars represent the standard deviations. Different letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05, according to one-way ANOVA and Duncan’s test), and the error bars represent the standard deviations.

Previous studies have shown that CsOxdC3 is involved in regulating the sensitivity of C. siamense to pyrrole and azole fungicides (Lu et al., 2024). Here, we further evaluated whether other genes in this family played role in regulating the sensitivity of C. siamense to various fungicides. The growth inhibition rate of individual strains was assessed on CM plates supplemented with different fungicides, including fludioxonil, fenpiclonil, prochloraz, and tebuconazole (Figures 5A,B). The results showed that only deletion of the CsOxdC3 gene, but not the other three genes, resulted in an increase in the growth inhibition rate under pyrrole fungicide (fludioxonil and fenpiclonil) stress. Under azole fungicide (prochloraz and tebuconazole) stress, the growth inhibition rates of both ∆CsOxdC3 and ∆CsOxdC1 were greater than those of WT. These results indicated that the CsOxdC3 gene played a positive role in regulating the sensitivity of C. siamense to pyrrole and azole fungicides, which was consistent with previous research results (Lu et al., 2024). CsOxdC1 also played a minor role in regulating the sensitivity of the strain to azole fungicides. These results suggested different OxdC genes played distinct roles in the regulation of fungicide sensitivity in C. siamense.

Figure 5. Comparison of fungicide sensitivity among WT (HN08), ΔCsOxdCs, CΔCsOxdCs. (A) Mycelial growth of the tested strains on CM supplemented with 1.0 μg/mL dpi, 0.1 μg/mL Fenpiclonil, 0.5 μg/mL Tebuconazole and 0.01 μg/mL Prochloraz for 5 dpi. (B) Growth inhibition rates of the tested strains under different concentration of fungicides. The growth inhibition rate is relative to the growth rate of each untreated control. Three repeats were performed. The error bars represent the standard deviations. Different letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05, according to one-way ANOVA and Duncan’s test), and the error bars represent the standard deviations.

Previous studies have shown that ∆CsOxdC3 attenuates the virulence of C. siamense (Lu et al., 2024). In this study, we tested the pathogenicity of three other gene deletion mutants. Conidial suspensions of the individual strains (105 conidia/mL) were inoculated onto rubber tree leaves with and without wounding. The results revealed that the lesion areas caused by ΔCsOxdC1 and ΔCsOxdC4 were not significantly different from those caused by the WT strain or the complemented strains on both wounded and unwounded leaves. This finding indicated that deletion of the CsOxdC1 and CsOxdC4 genes did not significantly affect the pathogenicity of C. siamense (Figures 6A,B,E,F). However, the lesion areas infected by ΔCsOxdC2, HN08 and CΔCsOxdC2 on wounded leaves were 0.55 ± 0.28 cm2, 1.17 ± 0.36 cm2, and 0.91 ± 0.28 cm2, respectively. On unwounded leaves, the lesion areas were 0.31 ± 0.16 cm2, 0.41 ± 0.17 cm2, and 0.48 ± 0.12 cm2, respectively. Data analyses revealed that the lesion area caused by ΔCsOxdC2 was significantly smaller than that caused by HN08 both on wounded and unwounded leaves, and the pathogenicity was restored to the WT level in the complemented strain CΔCsOxdC2 (Figures 6C,D). These results indicated that the CsOxdC2 gene played an important role in the pathogenicity of C. siamense but not in CsOxdC1 or CsOxdC4. The pathogenicity test of this study, along with previous studies, suggested that CsOxdC2 and CsOxdC3 in the OxdCs family were involved in the virulence of C. siamense.

Figure 6. Virulence assays performed on rubber tree leaves. (A,C,E) Schematic diagram and symptoms of the virulence assays of the tested strains. The rubber tree leaves were inoculated with 10 μL of conidial suspension (1 × 105 conidia/mL) of the tested strains with and without wounded. (B,D,F) Dot plot analysis of the lesion areas at 5 dpi. Different letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05, according to one-way ANOVA and Duncan’s test), and the error bars represent the standard deviations.

OxdC is a ubiquitous and common enzyme belonging to the cupin superfamily, which has a broad range of biochemical functions, including cell wall synthesis and oxidative processing (Azam et al., 2001; Chowdhury et al., 2024). Research on OxdC has focused mainly on its oxalate decarboxylase activity and potential applications, such as its ability to reduce calcium oxalate stones in medicine (Chakraborty et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2014; Sasikumar et al., 2014; Paul et al., 2018). In agriculture, most studies have focused mainly on heterologous expression of the OxdC gene to improve plant resistance to pathogens (Kesarwani et al., 2000; Dias et al., 2006; Walz et al., 2008; Qi et al., 2017; Pereira et al., 2022). Research on the biological function of OxdCs in microorganisms has been relatively limited to date. Previous studies on plant pathogenic fungi have shown that some OxdCs are involved in plant pathogenicity, especially necrotrophic fungi (Liang et al., 2015a). Little is known about the biological function of OxdCs in hemibiotrophic or biotrophic fungi. We previously reported that an OxdC-encoding gene, CsOxdC3, acts as an interactor of the mitogen-activated protein kinase CsPbs2, which is involved in morphogenesis, fungicide resistance and virulence in C. siamense (Lu et al., 2024). In this study, we systematically compared and analyzed the functions of all four OxdCs in morphogenesis, oxalate decarboxylase enzyme activity, stress regulation, fungicide resistance and virulence in C. siamense via the loss of single gene function method. We demonstrated that four individual genes exhibited distinct roles in the morphogenesis, enzyme activity, stress regulation, and pathogenicity of C. siamense, facilitating understanding of the biological functions of OxdCs in plant pathogenic fungi.

To survive, microorganisms usually evolve multiple genes to cope with the same biochemical processes to adapt to environmental conditions and stresses. These genes are redundant in certain functions and often exhibit differentiation. The presence of multiple OxdCs that degrade OA in fungi is a typical example. Previous studies have demonstrated the various functions of different OxdCs in fungi. For example, among three OxdC genes in C. minitans, two genes (CmOxdc1 and CmOxdc3) are involved in OA degradation and the ability to parasitize the sclerotia of S. sclerotiorum (Zeng et al., 2014). In this study, we first systematically compared the oxalate decarboxylase activity of four OxdC genes in C. siamense. We found that three proteins, CsOxdC1, CsOxdC2, and CsOxdC4, possessed oxalate decarboxylase activity, whereas CsOxdC3 exhibited the weakest oxalate degradation ability. Among these four proteins, the amino acid sequences of CsOxdC3 and CsOxdC4 were especially similar, with 76.41% homology, but their enzyme activities were quite different (Figure 2). This variation in enzymatic activity implied that different fungal OxdC genes might have diverse physiological and biological functions. Some of these genes might play specific roles in response to environmental conditions and stress factors.

In addition to their various enzymatic activities, different OxdCs have diverse functions in morphosporogenesis and stress regulation in C. siamense. Our findings demonstrated that CsOxdCs were involved in spore germination, sporulation, and appressorium formation, with each gene showing differential regulation. Among them, CsOxdC3 played an important role in appressorium formation, which was abrogated in the gene deletion mutant (Figure 3F). In terms of their role in stress regulation, we also observed that four OxdCs played diverse roles in response to Mn2+ and Cu2+. OxdC is a manganese-containing polymerase (Mäkelä et al., 2010). Among these four OxdCs, CsOxdC2 and CsOxdC4 had positive roles in resistance to Mn2+ and Cu2+ stresses, and they exhibited relatively high oxalate decarboxylase activity. These results suggested that CsOxdC2 and CsOxdC4 served as major enzymes involved in the degradation of OA in C. siamense. With respect to fungicide resistance, our results demonstrated that CsOxdC1 and CsOxdC3 were involved in fungicide resistance regulation. CsOxdC1 played a slightly positive role in C. siamense resistance to azole fungicides, and CsOxdC3 played a significantly positive role in regulating the sensitivity of C. siamense to pyrrole and azole fungicides. We have previously reported that CsOxdC3 interacts with the protein kinase CsPbs2, which is involved in fungicide resistance in C. siamense (Lu et al., 2024). We speculated that the differences in resistance of these OxdCs to various types of fungicides might be due to their different interacting proteins in vivo.

Some plant pathogenic fungi, especially necrotrophic fungi, utilize OA as a virulence factor or a nonspecific phytotoxin in interactions with plants (Cessna et al., 2000). Mutants of the fungus lacking the ability to produce OA show reduced pathogenicity (Rana et al., 2022). Acting as enzymes in the degradation of OA via decarboxylation, some OxdCs have also been reported to be associated with the pathogenicity of plant pathogenic fungi, such as ss-odc2 in S. sclerotiorum (Liang et al., 2015a; Liang et al., 2015b). Among the four OxdC genes in C. siamense, CsOxdC2 and CsOxdC4 may be the major OA degradation enzymes, but CsOxdC2 has a role in virulence; CsOxdC4 shows no significant impact on pathogenicity. CsOxdC3 deletion mutants also exhibited a significant reduction in virulence in previous studies (Lu et al., 2024), whereas CsOxdC3 exhibited the weakest oxalate degradation ability in this study. C. siamense is a hemibiotrophic fungus, and OA may not be its major pathogenic factor. Because CsOxdCs are involved in spore germination, sporulation, and appressorium formation to different degrees, we speculated that the effects of CsOxdC2 and CsOxdC3 on the pathogenicity of C. siamense might involve not only OA but also a combination of multiple factors, including their effects on sporulation, spore germination and appressorium formation.

In summary, we systematically analyzed the biological functions of four oxalate decarboxylase genes in C. siamense in the present study, which was summarized in Supplementary Table S2. We revealed CsOxdC1, CsOxdC2, and CsOxdC4 played major roles in degrading Oxalic acid in C. siamense, whereas CsOxdC3 did not. Four CsOxdCs positively modulated morphosporogenesis, including vegetative growth, conidial size, conidial germination rate and the appressorium formation rate. These genes were also involved in stress homeostasis and fungicide resistance regulation to different extents. Furthermore, compared with WT, ΔCsOxdC2 and ΔCsOxdC3 exhibited significantly reduced virulence. In general, our study on the oxalate decarboxylase family in C. siamense, including aspects such as morphogenesis, stress homeostasis, fungicide resistance, and virulence, revealed that CsOxdCs have diverse functions and may operate through different pathways in C. siamense. These findings will help to elucidate the biological function of OxdCs in hemibiotrophic fungi.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

YLv: Formal analysis, Investigation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YLiu: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. YLin: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. HZ: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. JY: Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing. YZ: Resources, Writing – review & editing. WM: Resources, Writing – review & editing. WW: Writing – review & editing. CL: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was supported by the earmarked fund for HNARS (No. HNARS-07-ZJ03), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 32160613), the Earmarked Fund for China Agriculture Research System (No. CARS-33-BC1) and the Hainan Province Science and Technology Talent Innovation Project (KRJC2023B14).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2025.1547950/full#supplementary-material

Azam, M., Kesarwani, M., Chakraborty, S., Natarajan, K., and Datta, A. (2002). Cloning and characterization of the 5′-flanking region of the oxalate decarboxylase gene from Flammulina velutipes. Biochem. J. 367, 67–75. doi: 10.1042/bj20011573

Azam, M., Kesarwani, M., Natarajan, K., and Datta, A. (2001). A secretion signal is present in the Collybia velutipes oxalate decarboxylase gene. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 289, 807–812. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.6049

Cessna, S. G., Sears, V. E., Dickman, M. B., and Low, P. S. (2000). Oxalic acid, a pathogenicity factor for Sclerotinia sclerotiorum, suppresses the oxidative burst of the host plant. Plant Cell 12, 2191–2199. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.11.2191

Chakraborty, N., Ghosh, R., Ghosh, S., Narula, K., Tayal, R., Datta, A., et al. (2013). Reduction of oxalate levels in tomato fruit and consequent metabolic remodeling following overexpression of a fungal oxalate decarboxylase. Plant Physiol. 162, 364–378. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.209197

Chowdhury, N., Naorem, R. S., Hazarika, D. J., Goswami, G., Dasgupta, A., Bora, S. S., et al. (2024). An oxalate decarboxylase-like cupin domain containing protein is involved in imparting acid stress tolerance in Bacillus amyloliquefaciens MBNC. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 40:64. doi: 10.1007/s11274-023-03870-3

Dean, R., Van Kan, J. A. L., Pretorius, Z. A., Hammond-Kosack, K. E., Di Pietro, A., Spanu, P. D., et al. (2012). The top 10 fungal pathogens in molecular plant pathology. Mol. Plant Pathol. 13:804. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2012.00822.x

Dias, B. B. A., Cunha, W. G., Morais, L. S., Vianna, G. R., Rech, E. L., de Capdeville, G., et al. (2006). Expression of an oxalate decarboxylase gene from Flammulina sp. in transgenic lettuce (Lactuca sativa) plants and resistance to Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Plant Pathol. 55, 187–193. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3059.2006.01342.x

Dutton, M. V., and Evans, C. S. (1996). Oxalate production by fungi: its role in pathogenicity and ecology in the soil environment. Can. J. Microbiol. 42, 881–895. doi: 10.1139/m96-114

Grąz, M. (2024). Role of oxalic acid in fungal and bacterial metabolism and its biotechnological potential. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 40:178. doi: 10.1007/s11274-024-03973-5

Grąz, M., Pawlikowska-Pawlęga, B., and Jarosz-Wilkołazka, A. (2011). Growth inhibition and intracellular distribution of Pb ions by the white-rot fungus Abortiporus biennis. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegradation 65, 124–129. doi: 10.1016/j.ibiod.2010.08.010

Hastrup, A. C. S., Green, F., Lebow, P. K., and Jensen, B. (2012). Enzymatic oxalic acid regulation correlated with wood degradation in four brown-rot fungi. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegradation 75, 109–114. doi: 10.1016/j.ibiod.2012.05.030

Kabbage, M., Williams, B., and Dickman, M. B. (2013). Cell death control: the interplay of apoptosis and autophagy in the pathogenicity of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. PLoS Pathog. 9:e1003287. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003287

Kathiara, M., Wood, D. A., and Evans, C. S. (2000). Detection and partial characterization of oxalate decarboxylase from Agaricus bisporus. Mycol. Res. 104, 345–350. doi: 10.1017/s095375629900129x

Kesarwani, M., Azam, M., Natarajan, K., Mehta, A., and Datta, A. (2000). Oxalate decarboxylase from Collybia velutipes. Molecular cloning and its overexpression to confer resistance to fungal infection in transgenic tobacco and tomato. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 7230–7238. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.10.7230

Khodadadi, F., Giroux, E., Bilodeau, G. J., Jurick, W. M. 2nd, and Aćimović, S. G. (2023). Genomic resources of four Colletotrichum species (C. Fioriniae, C. Chrysophilum, C. Noveboracense, and C. Nupharicola) threatening commercial apple production in the eastern United States. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 36, 529–532. doi: 10.1094/mpmi-10-22-0204-a

Kim, K. S., Min, J. Y., and Dickman, M. B. (2008). Oxalic acid is an elicitor of plant programmed cell death during Sclerotinia sclerotiorum disease development. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 21, 605–612. doi: 10.1094/mpmi-21-5-0605

Kumar, V., Irfan, M., and Datta, A. (2019). Manipulation of oxalate metabolism in plants for improving food quality and productivity. Phytochemistry 158, 103–109. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2018.10.029

Lee, E., Jeong, B. C., Park, Y. H., and Kim, H. H. (2014). Expression of the gene encoding oxalate decarboxylase from Bacillus subtilis and characterization of the recombinant enzyme. BMC. Res. Notes 7:598. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-7-598

Liang, X., Liberti, D., Li, M., Kim, Y. T., Hutchens, A., Wilson, R., et al. (2015a). Oxaloacetate acetylhydrolase gene mutants of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum do not accumulate oxalic acid, but do produce limited lesions on host plants. Mol. Plant Pathol. 16, 559–571. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12211

Liang, X., Moomaw, E. W., and Rollins, J. A. (2015b). Fungal oxalate decarboxylase activity contributes to Sclerotinia sclerotiorum early infection by affecting both compound appressoria development and function. Mol. Plant Pathol. 16, 825–836. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12239

Ling, J. F., Song, X. B., Xi, P. G., Cheng, B. P., Cui, Y. P., Chen, X., et al. (2019). Identification of Colletotrichum siamense causing litchi pepper spot disease in mainland China. Plant Pathol. 68, 1533–1542. doi: 10.1111/ppa.13075

Liu, X., Li, B., Cai, J., Zheng, X., Feng, Y., and Huang, G. (2018). Colletotrichum species causing anthracnose of rubber trees in China. Sci. Rep. 8:10435. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-28166-7

Liu, Y., Xi, Y., Lv, Y., Yan, J., Song, M., Yang, H., et al. (2023). The plasma membrane H(+) ATPase CsPMA2 regulates lipid droplet formation, Appressorial development and virulence in Colletotrichum siamense. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24:7337. doi: 10.3390/ijms242417337

Lu, J., Liu, Y., Song, M., Xi, Y., Yang, H., Liu, W., et al. (2024). The CsPbs2-interacting protein oxalate decarboxylase CsOxdC3 modulates morphosporogenesis, virulence, and fungicide resistance in Colletotrichum siamense. Microbiol. Res. 284:127732. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2024.127732

Mäkelä, M., Galkin, S., Hatakka, A., and Lundell, T. (2002). Production of organic acids and oxalate decarboxylase in lignin-degrading white rot fungi. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 30, 542–549. doi: 10.1016/S0141-0229(02)00012-1

Mäkelä, M. R., Hildén, K., and Lundell, T. K. (2010). Oxalate decarboxylase: biotechnological update and prevalence of the enzyme in filamentous fungi. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 87, 801–814. doi: 10.1007/s00253-010-2650-z

Micales, J. A. (1997). Localization and induction of oxalate decarboxylase in the brown-rot wood decay fungus Postia placenta. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegradation 39, 125–132. doi: 10.1016/S0964-8305(97)00009-7

Paul, E., Albert, A., Ponnusamy, S., Mishra, S. R., Vignesh, A. G., Sivakumar, S. M., et al. (2018). Designer probiotic Lactobacillus plantarum expressing oxalate decarboxylase developed using group II intron degrades intestinal oxalate in hyperoxaluric rats. Microbiol. Res. 215, 65–75. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2018.06.009

Pereira, S., de Andrade Silva, E. M., Peres Gramacho, K., Freitas Sena, K., da Costa Silva, D., Lima Aragão, F. J., et al. (2022). Transgenic tomato expressing an oxalate decarboxylase gene from Flammulina sp. shows increased survival to Moniliophthora perniciosa. Sci. Hortic. 299:111004. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2022.111004

Perfect, S. E., Hughes, H. B., O'Connell, R. J., and Green, J. R. (1999). Colletotrichum: a model genus for studies on pathology and fungal-plant interactions. Fungal Genet. Biol. 27, 186–198. doi: 10.1006/fgbi.1999.1143

Qi, Z., Yu, J., Shen, L., Yu, Z., Yu, M., Du, Y., et al. (2017). Enhanced resistance to rice blast and sheath blight in rice (oryza sativa L.) by expressing the oxalate decarboxylase protein Bacisubin from Bacillus subtilis. Plant Sci. 265, 51–60. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2017.09.014

Qin, L. P., Zhang, Y., Su, Q., Chen, Y., Nong, Q., Xie, L., et al. (2019). First report of anthracnose of Mangifera indica caused by Colletotrichum scovillei in China. Plant Dis. 103:1043. doi: 10.1094/pdis-11-18-1980-pdn

Rana, K., Yuan, J., Liao, H., Banga, S. S., Kumar, R., Qian, W., et al. (2022). Host-induced gene silencing reveals the role of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum oxaloacetate acetylhydrolase gene in fungal oxalic acid accumulation and virulence. Microbiol. Res. 258:126981. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2022.126981

Rollins, J. A., and Dickman, M. B. (2001). pH signaling in Sclerotinia sclerotiorum: identification of a pacC/RIM1 homolog. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67, 75–81. doi: 10.1128/aem.67.1.75-81.2001

Sasikumar, P., Gomathi, S., Anbazhagan, K., Abhishek, A., Paul, E., Vasudevan, V., et al. (2014). Recombinant Lactobacillus plantarum expressing and secreting heterologous oxalate decarboxylase prevents renal calcium oxalate stone deposition in experimental rats. J. Biomed. Sci. 21:86. doi: 10.1186/s12929-014-0086-y

Song, M., Fang, S., Li, Z., Wang, N., Li, X., Liu, W., et al. (2022). CsAtf1, a bZIP transcription factor, is involved in fludioxonil sensitivity and virulence in the rubber tree anthracnose fungus Colletotrichum siamense. Fungal Genet. Biol. 158:103649. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2021.103649

Sweigard, J. A., Chumley, F. G., Carroll, A. M., Farrall, L., and Valent, B. (1997). A series of vectors for fungal transformation. Fungal Genet. Rep. 44, 52–53. doi: 10.4148/1941-4765.1287

Tian, J., Chen, C., Sun, H., Wang, Z., Steinkellner, S., Feng, J., et al. (2021). Proteomic analysis reveals the importance of exudates on Sclerotial development in Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. J. Agric. Food Chem. 69, 1430–1440. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.0c06685

Walz, A., Zingen-Sell, I., Theisen, S., and Kortekamp, A. (2008). Reactive oxygen intermediates and oxalic acid in the pathogenesis of the necrotrophic fungus Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 120, 317–330. doi: 10.1007/s10658-007-9218-5

Williams, B., Kabbage, M., Kim, H. J., Britt, R., and Dickman, M. B. (2011). Tipping the balance: Sclerotinia sclerotiorum secreted oxalic acid suppresses host defenses by manipulating the host redox environment. PLoS Pathog. 7:e1002107. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002107

Xu, Y., Wu, M., Zhang, J., Li, G., and Yang, L. (2022). Cloning and molecular characterization of CmOxdc3 coding for oxalate decarboxylase in the Mycoparasite Coniothyrium minitans. J. Fungi 8:1304. doi: 10.3390/jof8121304

Keywords: Colletotrichum siamense, oxalate decarboxylase, morphosporogenesis, stress homeostasis, fungicide sensitivity, virulence

Citation: Lv Y, Liu Y, Lin Y, Zheng H, Yan J, Zhang Y, Miao W, Wu W and Lin C (2025) Functional diversification of oxalate decarboxylases in terms of enzymatic activity, morphosporogenesis, stress regulation and virulence in Colletotrichum siamense. Front. Microbiol. 16:1547950. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2025.1547950

Received: 19 December 2024; Accepted: 19 February 2025;

Published: 28 February 2025.

Edited by:

Vijay K. Sharma, Agricultural Research Organization (ARO), IsraelReviewed by:

Anupam Sharma Mahto, Brown University, United StatesCopyright © 2025 Lv, Liu, Lin, Zheng, Yan, Zhang, Miao, Wu and Lin. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wei Wu, d2Vpd3UyMDIzQGhhaW5hbnUuZWR1LmNu; Chunhua Lin, bGluMzI4NjMyMEBoYWluYW51LmVkdS5jbg==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.