95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Microbiol. , 03 March 2025

Sec. Systems Microbiology

Volume 16 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2025.1532341

This article is part of the Research Topic Investigating the Role of Microorganisms in Ecosystems and Their Interactions with the Humans, Animals, Plants, and Environment Interface View all 6 articles

Longbing Lin1

Longbing Lin1 Yongsheng Lin1

Yongsheng Lin1 Nemat O. Keyhani2

Nemat O. Keyhani2 Huili Pu1

Huili Pu1 Jiao Yang1

Jiao Yang1 Chengjie Xiong1

Chengjie Xiong1 Junya Shang1

Junya Shang1 Yuchen Mao1

Yuchen Mao1 Lixia Yang1

Lixia Yang1 Minghai Zheng1

Minghai Zheng1 Mengjia Zhu1

Mengjia Zhu1 Taichang Mu1

Taichang Mu1 Yi Li3

Yi Li3 Huiling Liang4

Huiling Liang4 Longfei Fan5

Longfei Fan5 Xiaoli Ma6

Xiaoli Ma6 Haixia Ma7

Haixia Ma7 Wen Xiong8

Wen Xiong8 Junzhi Qiu1*

Junzhi Qiu1* Xiayu Guan9*

Xiayu Guan9*Introduction: Entomopathogenic fungi play a crucial role in the ecological regulation of insect populations and can be exploited as a resource for pest control, sustainable agriculture, and natural products discovery. These fungi and their infected hosts are sometimes highly coveted as part of traditional medicine practices. Here, we sought to examine the biodiversity of entomogenous fungi in subtropical forests of China.

Methods: Fungal-infected insect specimens were collected from various sites in Fujian Province, China, and purified isolates were obtained through laboratory cultivation and isolation techniques. Molecular characterization of specific target genomic loci was performed on the fungal isolates, and used for phylogenetic analyses using Bayesian inference and maximum likelihood methods to elucidate their taxonomic relationships. Microscopy was used to describe the morphological features of the isolates.

Results: Through a comprehensive two-year survey of Fujian Province via multilocus molecular phylogenetic analysis targeting the nrSSU, nrLSU, tef1-α, rpb1, and rpb2 loci of collected specimens, we identified three novel species within the Clavicipitaceae herein described as: Albacillium fuzhouense sp. nov., Conoideocrella gongyashanensis sp. nov. and Neoaraneomyces wuyishanensis sp. nov., as well as the recently recorded, Metarhizium cicadae. Each new species was also distinguished from its closest relatives by unique morphological characteristics.

Discussion: These discoveries enrich our understanding of biodiversity within the Clavicipitaceae family and can contribute to the development of new pest control strategies and natural products discovery.

Entomogenous fungi are pathogenic microorganisms that can infect and kill insect hosts (Litwin et al., 2020; Li et al., 2023). They play a key role in regulating the ecological balance of insect populations in a wide range of natural ecosystems, including forests, and have been exploited as a resource for pest biological control and sustainable agriculture. Various isolates of these fungi have been developed into promising green biopesticides (Pattemore et al., 2014; Hyde et al., 2019), contributing to biodiversity conservation by offering a more environmentally friendly approach to pest management. Currently, several species such as Beauveria Vuill., Metarhizium Sorokīn, and Lecanicillium W. Gams & Zare are widely used for applied biological control of agricultural pests (Mantzoukas and Eliopoulos, 2020). In addition, some isolates of plant-pathogenic fungi such as Alternaria alternata can also be pathogenic to insects (Paschapur et al., 2022). The family Clavicipitaceae (Ascomycota, Hypocreales) is distributed widely in nature and can be found in different trophic levels and organisms, e.g., plants, soil, insects, and other invertebrates (Sung et al., 2007; Steiner et al., 2011; Kepler et al., 2011; Thanakitpipattana et al., 2020). Recent studies have characterized the diversity of Clavicipitaceae into at least 53 genera with more than 750 species (Chen et al., 2022; Phull et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2023). The morphology of Clavicipitaceae is usually characterized by cylindrical asci, thickened ascus apices, and filiform and multiseptate ascospores that are often disjoint at maturity (Rogerson, 1970; Sung et al., 2007). Clavicipitaceae fungi play an important role in plant protection and symbiotic evolution. They have diverse applications, including pest management and the treatment of conditions such as migraines, Alzheimer’s disease, and Parkinson’s disease through ergot alkaloids (Robinson and Panaccione, 2015; Florea et al., 2017). In addition, endophytes such as Epichloë enhance host plants’ stress resistance by producing bioactive compounds (Karpyn et al., 2017; Fernando et al., 2021).

The genus Albacillium was proposed by Ding et al. (2024) and first discovered in the forest litter of Northeast China. Albacillium hingganense was designated as the type species. Although Albacillium and Chlorocillium share a close relationship in phylogenetics, they exhibit differences in both morphological characteristics and phylogenetic placement determined by multilocus molecular data. Albacillium is characterized by conidia that are produced directly from phialides and arranged in slimy, globular clusters at the apices of the phialides. Currently, there is only one species within the genus A. hingganense (Ding et al., 2024).

Metarhizium is a genus that belongs to the family Clavicipitaceae and has rich morphological and ecological diversity (Brunner-Mendoza et al., 2019; Dakhel et al., 2020). Due to the incredible insect parasitizing ability of various Metarhizium members, certain species, e.g., Metarhizium anisopliae, Metarhizium robertsii, and Metarhizium brunneum have been used to develop eco-friendly commercial biological control agents (Meyling and Eilenberg, 2007; Zimmermann, 2007; Castrillo et al., 2011). Metarhizium species can be described by morphological characteristics such as mycelium/conidia (spore), conidia structure (size, arrangement, and production), and hyphal and other cell structure parameters (Sung et al., 2007). However, with the increasing number of species in this genus, morphological convergences can hinder species identification, with examples of cryptic species. In recent years, multigene phylogenetic studies have been able to exploit molecular approaches to better distinguish between various species of Metarhizium and its related genera (Luangsa-ard et al., 2017; Mongkolsamrit et al., 2020). Metarhizium sp. have been used in pest control worldwide for over 140 years (Nishi et al., 2013; González-Hernández et al., 2020), with continued discovery of diversity within Metarhizium being reported.

The genus Torrubiella Boud. was classified within Clavicipitaceae by Boudier in 1885 (Boudier, 1885). Fungi of this genus can parasitize a range of arthropods; however, spiders and scale insects appear to be particularly targeted hosts (Johnson et al., 2009). At present, there are 84 records of the genera in the Index (data from online service Index Fungorum http://www.indexfungorum.org; accessed on 15 September 2024). The majority of the species of Torrubiella are characterized by infected hosts wrapped in loose hyphae that generate conical, elongate perithecia and planar stromata (Johnson et al., 2009; Mongkolsamrit et al., 2016). Torrubiella is closely related to Cordyceps s. 1. but differs in morphology, although members have been subsequently divided into three distinct families (Clavicipitaceae, Cordycipitaceae, and Ophiocordycipitaceae) (Johnson et al., 2009). At the same time, a new genus, Conoideocrella, was proposed by Johnson et al. (2009), with C. luteorostrata (Zimm.) identified as the type species. Currently, Conoideocrella contains four species, all of which have a sexual morph similar to Torrubiella (Hywel-Jones, 1993; Mongkolsamrit et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2024). C. krungchingensis is parasitic on scale insects and was found on the undersides of fallen leaves in Thailand (Mongkolsamrit et al., 2016). In addition, C. fenshuilingensis appears to be distributed only in China (Wang et al., 2024).

The majority of the spider-pathogenic fungi are distributed in Cordycipitaceae and Ophiocordycipitaceae and include both generalist and specialist (essentially spider-specific) members, e.g., Akanthomyces Lebert, Beauveria Vuill., Cordyceps, Gibellula Cavara, Hevansia Luangsa-ard, Hirsutella Pat., Hymenostilbe Petch, Purpureocillium Luangsa-ard, and Torrubiella Boud (Chen et al., 2018; Chen et al., 2022; Joseph et al., 2024). The genus Neoaraneomyces is an araneopathogenic fungus first identified in the Clavicipitaceae family with Neoaraneomyces araneicola as the type species (Chen et al., 2022). Neoaraneomyces fungi produce white to gray mycelia completely covering the spider host. At present, there is only one species in this genus.

The biodiversity of entomopathogenic fungi in subtropical forests in China remains underexplored. Fujian Province in South-eastern China is highly forested (65.12%) and is environmentally neotropical. Its unique subtropical climate and biodiversity provide a rich habitat for diverse fungal species. During our survey assessing the diversity of entomogenous fungi across various regions of Fujian Province, we collected a variety of insect specimens exhibiting fungal infections. Combined molecular analyses using five genetic loci (nrSSU, nrLSU, tef1-α, rpb1, and rpb2) combined with detailed morphological characterization revealed three new species, one each within Albacillium, Conoideocrella, and Neoaraneomyces, as well as a new record of Metarhizium cicadae in China.

Fungal-infected insect specimens were collected from understory vegetation, stones, and decomposing matter in mixed forests of Fuzhou City, the Gongyashan National Forest Park, Longqishan National Nature Reserve, and Wuyi Mountain National Nature Reserve in Fujian Province, China (Supplementary Figure S1), between September 2023 and June 2024, focusing on the summer months. Infected specimens were recorded and photographed in the field before collection and transport to the laboratory for further analyses. The specimens were stored in 50-mL sterile conical tubes containing a small amount of silica gel. To obtain purified isolates, stromata or synnemata from host bodies were taken in a sterile workbench, soaked in 75% alcohol for 30 s, and then washed twice with sterile water. After using sterilized filter paper to dry the tissue fragment, sample segments were inoculated onto potato dextrose agar (PDA: fresh potato chips 200 g/L, agar and dextrose 20 g/L, respectively) plates. After allowing for fungal mycelial growth (3–5 days), colony edges were used to inoculate fresh PDA plates until a pure culture was obtained by visual inspection. All characterized specimens have been preserved in the Fungarium (HMAS) at the Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences. Characterized microbial strains have also been deposited with the China General Microbiological Culture Collection Center (CGMCC).

A portion of the tissue from the pure culture (PDA plates) was picked and mounted in acid cotton blue on a slide. The microscopic morphological characteristics of the strains were observed using a Nikon Ni-U (Tokyo, Japan) compound microscope and a Nikon SMZ74 (Tokyo, Japan) stereomicroscope, and measurements were made using Digimizer image analysis software 6.4.0 (MedCalc Software Ltd., Belgium). Fungal cultures were also incubated on a PDA (25°C) for 2 weeks and subsequently photographed using a Canon EOS 6D Mark II (Tokyo, Japan) camera. Colony growth rates were calculated based on the methods of Liu and Hodge by taking measurements daily (Liu and Hodge, 2005).

The total genomic DNA was extracted from the cultured mycelia using the Omega D3390 Fungal DNA Mini Kit (Guangzhou Feiyang Biological Engineering Co., LTD, China) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Five-gene loci including the nuclear ribosomal small subunit (nrSSU) (Wang et al., 2015), the nuclear ribosomal large subunit (nrLSU) (Vilgalys and Hester, 1990; Rehner and Samuels, 1994), translation elongation factor 1-α (tef1-α) (Bischof et al., 2006; Sung et al., 2007), and RNA polymerase II largest and second largest subunits (rpb1 and rpb2) (Liu et al., 1999; Bischof et al., 2006; Sung et al., 2007) were targeted for PCR amplification and sequencing (primers given in Table 1, Sangon Biotech, Shanghai Co., Ltd). Each PCR amplification reaction consisted of 12.5 μL of 2 × Rapid Taq PCR Master Mix (Vazyme, Nanjing, China), 1 μL of each forward and reverse primer (10 μM), 1 μL of genomic DNA, and 9.5 μL of distilled deionized water (Sangon Bio Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) to a total volume of 25 μL. PCR reactions were performed in a Bio-Rad thermal cycler (Hercules, CA, United States). The PCR products were purified and sequenced by Tsingke Biotech Co., Ltd. (Fuzhou, China). Sequences generated in this study have been submitted to GenBank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank, under accession numbers as given in Table 2).

Table 2. Species, voucher information, locations, hosts, and corresponding GenBank accession numbers of the taxa used in this study.

Phylogenetic analyses were performed based on the five genetic loci examined (nrSSU, nrLSU, tef1-α, rpb1, and rpb2) and corresponding sequences from GenBank. GenBank accession numbers of comparative taxa used are listed in Table 2. MAFFT v. 7 online website (http://mafft.cbrc.jp/alignment/server/, accessed on 17 September 2024) was used to align all the sequences, and then sequences were manually edited using BioEdit v.7.2.6.1 (He et al., 2022) and MEGA v.7.0 (Kumar et al., 2016) as needed. The aligned loci sequences were concatenated using Phylosuite v1.2.2 (Zhang et al., 2020). Based on five-gene combination datasets, phylogenetic analyses were performed using Bayesian inference (BI) and maximum likelihood (ML). The ML and Bayesian analyses were conducted using IQ-tree v.2.1.3 (Nguyen et al., 2015) and MrBayes v.3.2.2 (Ronquist et al., 2012), respectively. Four simultaneous Markov chains were run for 2,500,000 generations, and trees were sampled with a frequency of every 100th generation. The initial 25% of sampled trees were discarded as burn-in. The clades support value over 0.9 in BI and greater than 70% in ML were considered significantly supported. Phylogenetic trees were viewed using the ITOL online service1 and FigTree v.1.4.3 and polished using Adobe Illustrator 2023.

Approximately 40 specimens were collected from four distinct locations in Fujian Province: Gongya Mountain National Forest Park, Longqishan National Nature Reserve, Wuyi Mountain National Nature Reserve, and Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University. More than 35 samples were purified into single colonies, and 12 strains showed unique morphological signatures. Genomic DNA was extracted from these isolates, and selected genetic loci were sequenced, as detailed in the Methods section. Of the 12 specimens examined, 3 were identified as novel isolates (with 1 being a first description in China), as further detailed below.

Five genetic loci (nrSSU, nrLSU, tef1-α, rpb1, and rpb2) were used to construct both ML and BI trees for molecular identification supporting new species descriptions in this study. Pleurocordyceps aurantiaca (MFLUCC 17–2,113) and Pleurocordyceps marginaliradians (MFLU 17–1,582) were selected as outgroups in the phylogenetic reconstruction of Clavicipitaceae. The total length of the concatenated sequences was 4,508 bp (nrSSU: 1–1,042 bp; nrLSU: 1043–1932 bp; tef1-α: 1933–2,829 bp; rpb1: 2830–3,518 bp, and rpb2: 3519–4,508 bp), with analyses including members from 172 taxa from 20 genera. The phylogenetic trees derived from both BI and ML analyses exhibited similar topological structures and indicated three new species and one newly recorded species within Clavicipitaceae as being strongly supported (Figure 1). These molecular analyses revealed that (1) the newly described C. gongyashanensis sp. nov. was closely related to C. fenshuilingensis and C. krungchingensis with high support value (ML-BS: 93%, BI-PP: 0.92), and (2) that two specimens were identical and described in this study as Albacillium fuzhouense, within Albacillium with strong support (BP = 100% and PP = 1). Analyses of four specimens that grouped within the Metarhizium clade indicated a monophyletic cluster that could be assigned to M. cicadae (BP = 94% and PP = 0.99). In addition, two specimens are described in this study as a new species, N. wuyishanensis, which is closely related to its syntopic species N. araneicola, forming a collective group (BP: 99%, PP: 1).

Figure 1. Phylogenetic analysis of Clavicipitaceae based on maximum likelihood (ML) and Bayesian inference (BI) using five-gene combination (nrSSU, nrLSU, tef1-α, rpb1, and rpb2). The ML bootstrap proportions (left) and BI posterior probabilities (right) greater than 70% and 0.7 were shown above brunches. Strains in both bold and red are generated in this study.

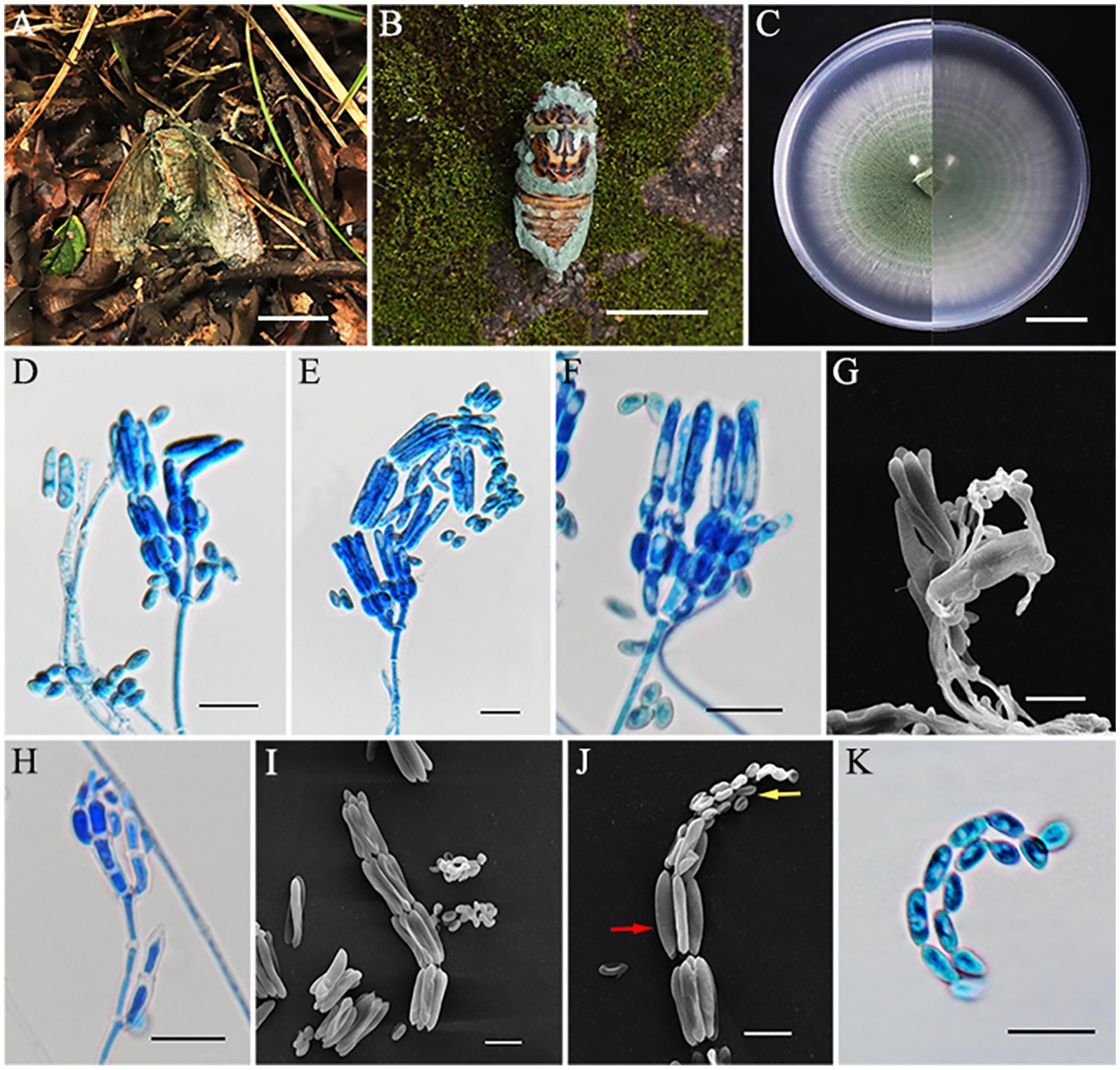

Albacillium fuzhouense L. B. Lin and J. Z. Qiu, sp. nov. (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Albacillium fuzhouense (holotype HMAS353206). (A,B) Larva of Coleoptera infected by A. fuzhouense. (C) Colony characteristics on PDA for 14 days. (D–K) Conidiophores (red arrow) and conidia (yellow arrow) on PDA. Scale bars: (A,C) 5 mm; (B) 1 mm; (D–K) 10 μm.

MycoBank No.: MB856115.

Etymology: Named after Fuzhou City, where the specimen was originally found.

Holotype: China, Fujian Province, Fuzhou City, 119°14′32″ E, 26°4′54″ N, alt. 62 m, found on a larva of Coleoptera attached to the leaf litter in a bamboo garden, 19 June 2024, J. Z. Qiu and L. B. Lin (HMAS353206, holotype; ex-holotype living culture CGMCC3.27818).

Sexual morph: Undetermined.

Asexual morph: Larvae (Coleoptera) covered by white and cottony mycelium, producing white and powdery conidia. Colonies grew well on PDA medium at a relatively constant rate, attaining a diameter of 38–39 mm after 14 days of cultivation at 25°C, with white, felty, dense mycelium, an entire margin, and reverse light yellow. Hyphae were hyaline, smooth-walled, septate, 1.1–2.1 μm wide. Phialides directly originated from aerial hyphae, lanceolate, solitary, hyaline, with a cylindrical base tapering to apex, 13.6–81.5 × 0.8–1.3 μm, mean = 36.9 × 1.1 μm. Conidia were fusiform, ellipsoidal and slightly curved, hyaline, smooth, one-celled, arranged either singly or in mucilaginous spherical clusters at the tips of the phialides, 2.4–6.7 × 1.0–1.4 μm, mean = 4.2 × 1.2 μm.

Habitat: Parasitic on larvae of Coleoptera attached to the leaf litter.

Distribution: China, Fujian Province, Fuzhou City, Jianxin Town.

Other materials examined: China, Fujian Province, Fuzhou City, 119°14′32″ E, 26°4′54″ N, alt. 1,084 m, found on a larva of Coleoptera attached to the leaf litter in a bamboo garden, 19 June 2024, J. Z. Qiu and L. B. Lin (HMAS353207, paratype; ex-paratype living culture CGMCC3.27815).

Notes: The five-gene multilocus phylogenetic analysis revealed that the two samples of A. fuzhouense clustered with A. hingganense with strong support (BP: 100%, PP: 1). Then, the nucleotide sequence comparison of rpb2 showed a 2.1% (23/1091) difference between A. fuzhouense and its related species. Morphologically, A. fuzhouense was similar in shape to its close relatives, yet is distinguished by possessing longer phialides (13.6–81.5 × 0.8–1.3 vs. 8.6–60.1 × 0.9–1.5 μm) and larger conidia (2.4–6.7 × 1.0–1.4 vs. 2.0–4.3 × 0.8–1.3 μm) compared to those of A. hingganense. In addition, the colonies on PDA of A. fuzhouense grew faster than A. hingganense, and the textures of the two are different. A. hingganense is velvet, while A. fuzhouense is more of a felty texture. Moreover, there existed a notable divergence in the host organisms and origins between these two species. The newly found species of the present study were parasitic on the larvae of Coleoptera and were isolated from the Fujian subtropical forest, whereas A. hingganense was isolated from forest litters in a cold temperate climatic zone (Table 3).

Conoideocrella gongyashanensis L. B. Lin and J. Z. Qiu, sp. nov. (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Conoideocrella gongyashanensis (holotype HMAS353158). (A,B) Dead spider infected by C. gongyashanensis. (C) Colony characteristics on PDA for 14 days. (D–N) Conidiogenous structures (red arrow) and conidia (yellow arrow) on PDA. Scale bars: (A,B) 2 mm; (C) 10 mm; (D–N)10 μm.

MycoBank No.: MB856116.

Etymology: Named after the Gongya Mountain National Forest Park, where the specimen was originally found.

Holotype: China, Fujian Province, Huaan County, Gongyashan National Forest Park. 117°25′26″ E, 24°54′15″ N, alt. 1,084 m, found on a dead spider that attaching to fallen leaves, 7 May 2024, J. Z. Qiu and L. B. Lin (HMAS353158, holotype; ex-holotype living culture CGMCC3.28305).

Sexual morph: Not observed.

Asexual morph: White to pale yellow and cottony mycelium enveloping the host. Colonies grew rapidly on PDA, reaching a diameter of 32–33 mm in 14 days at 25°C, yellow to light orange, with low mycelium density, a rigid, flocculent margin, and reverse yellowish brown. The growth rate of the colony was 23 mm/day. Hyphae were hyaline, smooth, 1.3–2.5 μm wide. The asexual phase was similar to Hirsutella and originated from vegetative hyphae. These featured conidiogenous structures that had a cylindrical base that gradually narrowed down toward a neck-like extension, hyaline, smooth-walled, 12.7–89.9 × 0.4–1.3 μm, mean = 53.5 × 0.9 μm. Conidia were hyaline, smooth-walled, fusiform-curved, single-celled, and clustered at the apex of the conidiogenous structures, 3.5–10.3 × 1.0–2.5 μm, mean = 6.2 × 1.59 μm.

Habitat: This species was parasitic on scale insects, found attached to the underside of fallen leaves.

Distribution: China, Fujian Province, Huaan County, Gongyashan National Forest Park.

Other materials examined: China, Fujian Province, Huaan County, Gongyashan National Forest Park. 117°25′26″ E, 24°54′15″ N, alt. 1,084 m, found on a dead spider of Sternorrhyncha that attached to the back of living leaves in May 2024, J. Z. Qiu and L. B. Lin (HMAS353159, paratype; ex-paratype living culture CGMCC3.28306).

Notes: C. gongyashanensis is the first species of the genus Conoideocrella to be discovered without an apparent sexual morph. The results of the molecular phylogenetic analysis indicate that two isolates of C. gongyashanensis were found which grouped together, forming a distinct branch within the genus. Phylogenetically, C. gongyashanensis was closely related to C. fenshuilingensis. Therefore, we compared the nucleotides of nrLSU, tef1-α, and rpb1 between C. gongyashanensis and its related species. The differences were as follows: 1.4% (11/812, nrLSU), 6.7% (58/866, tef1-α), and 11.4% (72/630, rpb1) when compared to C. fenshuilingensis.

Metarhizium cicadae S. Mongkolsamrit, A. Khonsanit, D. Thanakitpipattana and J. Luangsa-ard, Stud. Mycol. 95: 212 (2020) (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Metarhizium cicadae (HMAS353156). (A,B) Cicada adult infected by M. cicadae. (C) Colony characteristics on PDA for 14 days. (D–H) Part of conidiophores on PDA. (H–I) Microconidia (yellow arrow) and macroconidia (red arrow) on PDA. (K) Conidia on PDA. Scale bars: (A,B) 50 mm; (C) 20 mm; (D–K) 10 μm.

MycoBank No.: MB856117.

Sexual morph: Not known.

Asexual morph: Cicada adult (Hemiptera) covered by densely bright green powder, produces numerous green and powdery conidia. Colonies grew rapidly on PDA and reached a diameter of 74–75 mm in 14 days at 25°C, at first white and then turning green in the center due to sporulation after 7 days. Colonies flat, floccose, with areas producing green powder, entire margin, white border, reverse as the same, with a growth rate of 5.2–5.3 mm/day. Hyphae were hyaline, branched, smooth-walled, septate, and 1.2–2.6 μm wide. Conidiophores were densely arranged, rising from aerial hyphae, with 2–3 phialides per branch. Phialides cylindrical or clavate, 4.2–10.1 × 1.6–3.0 μm, mean = 6.3 × 2.4 μm, swollen at the bottom, and gradually tapering to a thin neck. Conidia often arrayed in chains, smooth-walled, dimorphic; microconidia came first, ellipsoidal or ovoid, 3.6–6.8 × 2.3–3.2 μm, mean = 5.1 × 2.8 μm; macroconidia produced later, mostly cylindrical, 13.8–20.2 × 2.5–3.6 μm, mean = 17.5 × 3.1 μm.

Habitat: Attached to fallen leaves of dicotyledonous plants or on the trunk of trees.

Distribution: thailand (type country) and China.

Other materials examined: China, Fujian Province, Mingxi County, Gaoyang village, 116°53′38″ E, 26°33′43″ N, alt. 524 m, found on a cicada adult (Hemiptera) covered by green powder, 3 September 2023, J. Z. Qiu and L. B. Lin (HMAS353154, HMAS353155, CGMCC3.28301, CGMCC3.28302 living culture). Fujian Province, Jiangle County, Longqishan National Nature Reserve, 117°20′31″ E, 26°31′43″ N, alt. 1,275 m, found on a cicada adult (Hemiptera), 1 July 2024, J. Z. Qiu and L. B. Lin (HMAS353156, HMAS353157, CGMCC3.28303, and CGMCC3.28304 living culture).

Notes: The species M. cicadae was classified by Mongkolsamrit et al. in 2020, in Thailand (Luangsa-ard et al., 2017). The existence of this species has not been reported in China. In this study, four specimens were collected in Fujian Province, and, according to the phylogenetic analysis, all of them are closely related to M. cicadae with high statistical support (94% in ML and 0.99 in BYPP). The morphology of the four strains was generally similar to M. cicadae, including similarities in the host, phialides proximity, and the size of both macroconidia and microconidia (Table 3). However, the collected specimens exhibited bright green colonies on PDA, attaining 74–75 mm in 14 days, while M. cicadae colonies were cream to green and grew only 15 mm after 14 days of cultivation. Overall, however, our data indicated that the four strains collected in this study should be identified as M. cicadae.

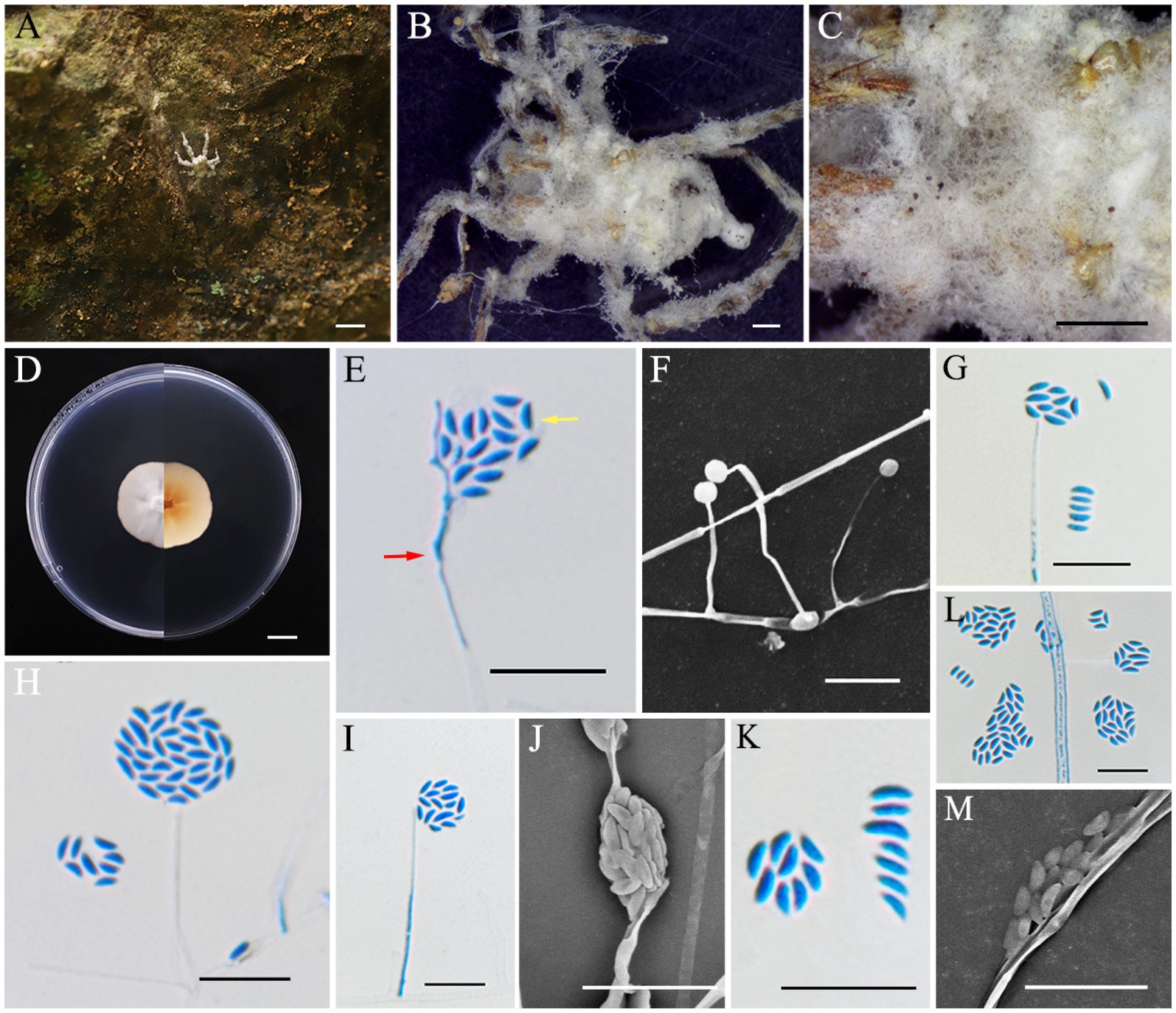

Neoaraneomyces wuyishanensis L. B. Lin and J. Z. Qiu, sp. nov. (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Neoaraneomyces wuyishanensis (holotype HMAS353160). (A–C) Spider infected by N. wuyishanensis. (D) Colony characteristics on PDA for 14 days. (E–M) Conidiophores (red arrow) and conidia (yellow arrow) on PDA. Scale bars: (A,D) 10 mm; (B,C) 1 mm; (E–M) 10 μm.

MycoBank No.: MB856118.

Etymology: Named after the Wuyi Mountain National Nature Reserve, where the species was originally found.

Holotype: China, Fujian Province, Wuyishan City, Xingcun Town, Wuyi Mountain National Nature Reserve, 117°39′12″ E, 27°36′14″ N, alt. 952 m, found on a spider adsorbed on the wall, 6 September 2023, J. Z. Qiu and L. B. Lin (HMAS353160, holotype; ex-holotype living culture CGMCC3.28307).

Sexual morph: Undetermined.

Asexual morph: The spider was completely enveloped by white to gray cottony mycelium. Colonies grew readily on PDA, showing velvety, low mycelium density, attaining a diameter of 28–30 mm after 14 days at 25°C. The colony was white, sunken slightly in the middle, reverse, light yellow to orange, with a growth rate of 2.0–2.1 mm/day. Hyphae were hyaline, smooth-walled, septate, 1.0–2.4 μm wide. Phialides were lanceolate, hyaline, originating from aerial hyphae, usually solitary, with a slender base, tapering to a thin neck, 6.2–34.3 × 0.9–2.0 μm, mean = 21.4 × 1.2 μm. Conidia were formed either at the apex of the phialides or in spherical clusters atop the phialides, smooth-walled, hyaline, ellipsoidal, fusiform and slightly curved, one-celled, 2.5–4.5 × 1.0–1.4 μm, mean = 3.1 × 1.2 μm.

Habitat: Attached to stone.

Distribution: China, Fujian Province, Wuyishan City, Xingcun Town, Wuyi Mountain National Nature Reserve.

Other materials examined: China, Fujian Province, Wuyishan City, Xingcun Town, Wuyi Mountain National Nature Reserve, 117°39′12″ E, 27°36′14″ N, alt. 952 m, found on a spider, 6 September 2023, J. Z. Qiu and L. B. Lin (HMAS353161, paratype; ex-paratype living culture CGMCC3.28308).

Notes: Multilocus analyses revealed that the two strains of N. wuyishanensis were similar to N. araneicola (DY101711, ex-holotype) with strong support (99% ML and 1 BYPP), including having the same host, parallel colony morphology, and conidia shape. The nucleotide comparison of rpb1 and rpb2 revealed separation from N. wuyishanensis and N. araneicola with differences of 1.67% (12/720, rpb1) and 1.26% (13/1031, rpb2), respectively. However, the arrangement of conidia between the species was quite different: the conidia of N. wuyishanensis sp. nov. were grouped, while those of N. araneicola were arranged in chains. Concurrently, the phialides of N. wuyishanensis sp. nov. are typically solitary, while those of N. araneicola are either individual or occur in small clusters of two to three. Furthermore, N. wuyishanensis has larger phialides (8.9–23.8 × 1.1–1.6 vs. 10.2–34.3 × 0.9–2.0 μm) and conidia (2.9–4.4 × 1.3–2.0 vs. 2.5–4.5 × 1.0–1.4 μm) compared to N. araneicola. In addition, after 14 days of cultivation on PDA, the mycelium of N. wuyishanensis sp. nov. appeared relatively fluffy, whereas that of its sibling species was slightly more compact. Moreover, this new species produced a pigment that ranged from yellow to orange (Table 3).

The majority of insect-pathogenic fungi prefer to grow in moist, shaded areas covered with vegetation (Nasir et al., 2023). Fujian is located in the southeast of China and is known for its lush vegetation and mild climate with frequent rainfall, which makes it very suitable for both insect populations and the fungi that target them. Within the past several years, we have conducted a survey of entomogenous fungal resources in several large nature reserves and national forest parks in Fujian, during which many specimens (>50) were collected. This has led to a significant increase in the diversity of a range of fungal species (Liu et al., 2024; Mu et al., 2024; Zhao et al., 2024), highlighting the rich fungal resources of this area. In this study, we expand this diversity by characterizing of three new species of entomopathogenic fungi and one new record species, namely: Albacillium fuzhouense, Conoideocrella gongyashanensis, Neoaraneomyces wuyishanensis, and Metarhizium cicadae. All of the described species belonged to the Clavicipitaceae. This discovery not only enriches the diversity of fungal resources in the Asian continent but also sheds light on the complexity and interactions within subtropical fungal communities, which is of great significance for biological control, drug development, ecological protection, and sustainable development, and helps to unravel the evolutionary relationships and divergence patterns within subtropical fungal communities.

We identify one of the new species in this study as belonging to the genus Albacillium. Albacillium is similar to Acremonium and an unresolved genus Chlorocillium (Hypocreales incertae sedis), with A. hingganense reported from forest litter (but not a particular insect) in Northeast China (Ding et al., 2024), a region climatically very different from Fujian. Albacillium and Chlorocillium apparently form a monophyletic group that is basal to the Clavicipitaceae but are distinguished by conidial arrangement and other morphological features. A second species, classified within the Conoideocrella genus, which previously only contained four species, was identified on scale insects. Conoideocrella, established by Johnson et al. (2009), is similar to other genera in Clavicipitaceae, parasitizing scale insects or whiteflies (Hemiptera, Coccidae, and Lecaniidae) (Mongkolsamrit et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2024). Thus, members of Conoideocrella have been identified as potential specific biological control agents for (armored) scale insects, e.g., the elongate Hemlock scale, Fiorinia externa (Hemiptera: Diaspididae), native to Asia and which feeds on coniferous trees, and these fungi have also been exploited as potential sources of bioactive compounds including those with antimalarial and antiproliferative effects (Mongkolsamrit et al., 2016; Saepua et al., 2018; Lovett et al., 2024).

Metarhizium spp. are one of the most widely distributed and characterized genera of entomopathogenic fungi worldwide and are known to parasitize a wide range of insects across Hemiptera, Lepidoptera, Coleoptera, and others (Luangsa-ard et al., 2017). Metarhizium species are often present in soil and can form close rhizosphere associations with a broad range of plants (Chen et al., 2018a,b; Chen W. H. et al., 2018; Nishi and Sato, 2018). The genus also contains members with both broad and narrow insect host ranges that have been exploited for pest biological control (Marciano et al., 2021). Although M. cicadae is nominally considered potentially host (cicada)-specific, this has not been confirmed experimentally, and some caution should be taken in extrapolating from survey findings (such as this study) and definitive conclusions concerning host ranges. Given this caveat, in this study, we report a new record of the M. cicadae species, originally isolated from cicadas in Thailand, now found in China from an infected cicada.

Spider-pathogenic fungi are mainly distributed in the order Hypocreales, commonly found on the underside of dicotyledonous leaves, on wet cliffs, and under rocks near roadsides. Among these fungi, the genus Gibellula is highly regarded as a particular spider killer (Kuephadungphan et al., 2022; Joseph et al., 2024). Neoaraneomyces is a relatively newly described apparently arachnid-pathogen-specific genus that is related to Claviceps, Hypocrella, and Epichloë but distinct from a similarly characterized Pseudometarhizium araneogenum and currently contains only one species, N. araneicola (Chen et al., 2022). In this study, we have identified a second species within Neoaraneomyces, N. wuyishanensis, based on phylogenetic and morphological analyses. Little is known concerning these spider pathogens, and our data add to the diversity of potential species that either have specialized across arthropod orders and/or have significantly broad specificities.

Fujian is a region with a particularly rich diversity of fungal species (Guan et al., 2024; Liu et al., 2024). The three new species of Albacillium, Conoideocrella, and Neoaraneomyces collected from Fujian, as described in this study, can contribute to pest management by inhabiting pests, consuming their internal tissues, and competing with other organisms, including pests or pathogens, for resources and space. Their application in commercial pest control is promising, particularly as part of integrated pest management (IPM) strategies that align with sustainable agriculture practices, such as combining living biocontrol agents (BCAs) to improve pest control (Galli et al., 2024). Further research is required to evaluate the virulence and host specificity of these fungi under field conditions.

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary material.

LL: Conceptualization, Visualization, Writing – original draft. YoL: Writing – original draft. NK: Data curation, Writing—review & editing. HP: Methodology, Writing—original draft. JY: Software, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing – original draft. CX: Validation, Data curation, Writing – original draft. JS: Validation, Writing – original draft. YM: Validation, Writing – original draft. LY: Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing – original draft. MiZ: Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing – original draft. MeZ: Investigation, Data curation, Writing – original draft. TM: Investigation, Data curation, Writing – original draft. YiL: Data curation, Writing – original draft. HL: Data curation, Writing – original draft. LF: Data curation, Writing – original draft. XM: Data curation, Writing – original draft. HM: Data curation, Writing – original draft. WX: Resources, Data curation, Writing – original draft. JQ: Conceptualization, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition, writing—review & editing. XG: Conceptualization, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 32270029, U1803232, 31670026), the National Key R & D Program of China (No. 2017YFE0122000), a Social Service Team Support Program Project (No. 11899170165), Science and Technology Innovation Special Fund (Nos. KFB23084, CXZX2019059S, CXZX2019060G) of Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University, a Fujian Provincial Major Science and Technology Project (No. 2022NZ029017), an Investigation and evaluation of biodiversity in the Jiulong River Basin (No. 082·23259-15), Macrofungal and microbial resource investigation project in Longqishan Nature Reserve (No. SMLH2024(TP)-JL003#), and an Investigation of macrofungal diversity in Junzifeng National Nature Reserve, Fujian Province (No. Min Qianyu Sanming Recruitment 2024-23).

We would like to thank China General Microbiological Culture Collection Center (CGMCC) and Fungarium (HMAS), Institute of Microbiology, CAS for strain and sample storage help.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2025.1532341/full#supplementary-material

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE 1 | Sampling sites map of Fujian Province, China. Notes: In the map, FAFU, GYC, GYS, LQS, and WYS correspond to Fuzhou City, Gaoyang Village, Gongyashan National Forest Park, Longqishan National Nature Reserve, and Wuyi Mountain National Nature Reserve, respectively.

Bischof, J. F., Rehner, S. A., and Humber, R. A. (2006). Metarhizium frigidum sp. nov.: a cryptic species of M. anisopliae and a member of the M. anisopliae complex. Mycologia 98, 737–745. doi: 10.1080/15572536.2006.11832645

Boudier, J. L. É. (1885). Note sur un nouveau genre et quelques nouvelles espèces des Pyrenomycètes. Revue Mycologique Toulouse. 7, 224–227.

Brunner-Mendoza, C., Reyes-Montes, M. D. R., Moonjely, S., Bidochka, M. J., and Toriello, C. (2019). A review on the genus Metarhizium as an entomopathogenic microbial biocontrol agent with emphasis on its use and utility in Mexico. Biocontrol Sci. Tech. 29, 83–102. doi: 10.1080/09583157.2018.1531111

Castrillo, L. A., Griggs, M. H., Ranger, C. M., Reding, M. E., and Vandenberg, J. D. (2011). Virulence of commercial strains of Beauveria bassiana and Metarhizium brunneum (Ascomycota: Hypocreales) against adult Xylosandrus germanus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) and impact on brood. Biol. Control 58, 121–126. doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2011.04.010

Chen, W. H., Liang, J. D., Ren, X. X., Zhao, J. H., Han, Y. F., and Liang, Z. Q. (2022). Phylogenetic, ecological and morphological characteristics reveal two new spider-associated genera in Clavicipitaceae. Myco Keys 91, 49–66. doi: 10.3897/mycokeys.91.86812

Chen, W. H., Liu, C., Han, Y. F., Liang, J. D., and Liang, Z. Q. (2018). Akanthomyces araneogenum, a new Isaria-like araneogenous species. Phytotaxa 379, 66–72. doi: 10.11646/phytotaxa.379.1.6

Chen, Z. H., Xu, L., Yang, X. N., Zhang, Y. G., and Yang, Y. M. (2018a). Metarhizium baoshanense sp. nov., a new entomopathogen fungus from southwestern China. Pak. J. Zool. 50, 1739–1746. doi: 10.17582/journal.pjz/2018.50.5.1739.1746

Chen, Z. H., Yang, X. N., Sun, N., Xu, L., Zheng, Y., and Yang, Y. M. (2018b). Species diversity and vertical distribution characteristics of Metarhizium in Gaoligong Mountains, southwestern China. Biodivers. Sci. 26, 1308–1317. doi: 10.17520/biods.2018131

Dakhel, W. H., Jaronski, S. T., and Schell, S. (2020). Control of Pest grasshoppers in North America. Insects 11:566. doi: 10.3390/insects11090566

Ding, M. M., Li, Y. P., Bai, Y., Gai, P. Z., Wang, J., and Jiang, Z. Z. (2024). Albacillium hingganense gen. Et sp. nov. (Clavicipitaceae) from forest litters in Northeast China. Phytotaxa 650, 157–168. doi: 10.11646/phytotaxa.650.2.3

Fernando, K., Reddy, P., Spangenberg, G. C., Rochfort, S. J., and Guthridge, K. M. (2021). Metabolic potential of Epichloë endophytes for host grass fungal disease resistance. Microorganisms 10:64. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms10010064

Florea, S., Panaccione, D. G., and Schardl, C. L. (2017). Ergot alkaloids of the family Clavicipitaceae. Phytopathology 107, 504–518. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-12-16-0435-RVW

Galli, M., Feldmann, F., Vogler, U. K., and Kogel, K. H. (2024). Can biocontrol be the game-changer in integrated pest management? A review of defnitions, methods and strategies. J. Plant. Dis. Prot. 131, 265–291. doi: 10.1007/s41348-024-00878-1

González-Hernández, G. A., Padilla-Guerrero, I. E., Martínez-Vázquez, A., and Torres-Guzmán, J. C. (2020). Virulence factors of the Entomopathogenic genus Metarhizium. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 21, 324–330. doi: 10.2174/1389203721666200116092407

Guan, X. Y., Zhu, M. J., Keyhani, N. O., Dang, Y. X., Lv, H. J., Wu, Z. Y., et al. (2024). Amanita minqingensis, a novel taxon of amanita section Vaginatae (Amanitaceae, Agaricales) from southern China. Phytotaxa 664, 85–97. doi: 10.11646/phytotaxa.664.2.1

He, J., Han, X., Luo, Z. L., Xian, L., Tang, S. M., Luo, H. M., et al. (2022). Species diversity of Ganoderma (Ganodermataceae, Polyporales) with three new species and a key to Ganoderma in Yunnan Province, China. Front. Microbiol. 13:1035434. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.1035434

Hyde, K. D., Xu, J. C., Rapior, S., Jeewon, R., Lumyong, S., Niego, A. G. T., et al. (2019). The amazing potential of fungi: 50 ways we can exploit fungi industrially. Fungal Divers. 97, 1–136. doi: 10.1007/s13225-019-00430-9

Hywel-Jones, N. L. (1993). Torrubiella luteorostrata: a pathogen of scale insects and its association with Paecilomyces cinnamomeus with a note on Torrubiella tenuis. Mycol. Res. 97, 1126–1130. doi: 10.1016/S0953-7562(09)80514-5

Johnson, D., Sung, G. H., Hywel-Jones, N. L., Luangsa-ard, J. J., Bischoff, J. F., Kepler, R. M., et al. (2009). Systematics and evolution of the genus Torrubiella (Hypocreales, Ascomycota). Mycol. Res. 113, 279–289. doi: 10.1016/j.mycres.2008.09.008

Joseph, R. A., Masoudi, A., Valdiviezo, M. J., and Keyhani, N. O. (2024). Discovery of Gibellula floridensis from infected spiders and analysis of the surrounding fungal Entomopathogen community. J. Fungi 10:694. doi: 10.3390/jof10100694

Karpyn, E. M., Yen, A. L., Rochfort, S., Guthridge, K. M., Powell, K. S., Edwards, J., et al. (2017). A review of perennial ryegrass endophytes and their potential use in the management of African black beetle in perennial grazing systems in Australia. Front. Plant Sci. 8:3. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00003

Kepler, R. M., Sung, G. H., Harada, Y., Tanaka, K., Tanaka, E., Hosoya, T., et al. (2011). Host jumping onto close relatives and across kingdoms by Tyrannicordyceps (Clavicipitaceae) gen. Nov. and Ustilaginoidea (Clavicipitaceae). Am. J. Bot. 99, 552–561. doi: 10.3732/ajb.1100124

Kuephadungphan, W., Petcharad, B., Tasanathai, K., Thanakitpipattana, D., Kobmoo, N., Khonsanit, A., et al. (2022). Multi-locus phylogeny unmasks hidden species within the specialised spider-parasitic fungus, Gibellula (Hypocreales, Cordycipitaceae) in Thailand. Stud. Mycol. 101, 245–286. doi: 10.3114/sim.2022.101.04

Kumar, S., Stecher, G., and Tamura, K. (2016). MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 33, 1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054

Li, Y., Zhao, X. C., Wu, L. X., Wang, Y., Xu, A., and Lin, W. F. (2023). Blackwellomyces kaihuaensis and Metarhizium putuoense (Hypocreales), two new Entomogenous Fungi from subtropical forests in Zhejiang Province, Eastern China. Forest 14:2333. doi: 10.3390/f14122333

Litwin, A., Nowak, M., and Rózalska, S. (2020). Entomopathogenic fungi: unconventional applications. Rev. Environ. Sci. Bio. 19, 23–42. doi: 10.1007/s11157-020-09525-1

Liu, M., and Hodge, K. T. (2005). Hypocrella zhongdongii sp. nov., the teleomorph of Aschersonia incrassata. Mycol. Res. 109, 818–824. doi: 10.1017/S095375620500290X

Liu, Y. J., Whelen, S., and Hall, B. D. (1999). Phylogenetic relationships among ascomycetes: evidence from an RNA polymerse II subunit. Mol. Biol. Evol. 16, 1799–1808. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026092

Liu, S., Zhu, M. J., Keyhani, N. O., Wu, Z. Y., Lv, H. J., Heng, Z. A., et al. (2024). Three new species of Russulaceae (Russulales, Basidiomycota) from southern China. J. Fungi 10:70. doi: 10.3390/jof10010070

Lovett, B., Barrett, H., Macias, A. M., Stajich, J. E., Kasson, L. R., and Kasson, M. T. (2024). Morphological andphylogenetic resolution of Conoideocrella luteorostrata (Hypocreales: Clavicipitaceae), a potential biocontrol fungus for Fiorinia externa in United States Christmas tree production areas. Mycologia 116, 267–290. doi: 10.1080/00275514.2023.2296337

Luangsa-ard, J. J., Mongkolsamrit, S., Thanakitpipattana, D., Khonsanit, A., Tasanathai, K., Noisripoom, W., et al. (2017). Clavicipitaceous entomopathogens: new species in Metarhizium and a new genus Nigelia. Mycol. Prog. 16, 369–391. doi: 10.1007/s11557-017-1277-1

Mantzoukas, S., and Eliopoulos, P. A. (2020). Endophytic entomopathogenic fungi: a valuable biological control tool against plant pests. Appl. Sci. 10:360. doi: 10.3390/app10010360

Marciano, A. F., Mascarin, G. M., Franco, R. F. F., Golo, P. S., Jaronski, S. T., Fernandes, É. K. K., et al. (2021). Innovative granular formulation of Metarhizium robertsii microsclerotia and blastospores for cattle tick control. Sci. Rep. 11:4972. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-84142-8

Meyling, N. V., and Eilenberg, J. (2007). Ecology of the entomopathogenic fungi Beauveria bassiana and Metarhizium anisopliae in temperate agroecosystems: potential for conservation biological control. Biol. Control 43, 145–155. doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2007.07.007

Mongkolsamrit, S., Khonsanit, A., Thanakitpipattana, D., Tasanathai, K., Noisripoom, W., Lamlertthon, S., et al. (2020). Revisiting Metarhizium and the description of new species from Thailand. Stud. Mycol. 95, 171–251. doi: 10.1016/j.simyco.2020.04.001

Mongkolsamrit, S., Thanakitpipattana, D., Khonsanit, A., Promharn, R., and Luangsa-ard, J. J. (2016). Conoideocrella krungchingensis sp. nov., an entomopathogenic fungus from Thailand. Mycoscience 57, 264–270. doi: 10.1016/j.myc.2016.03.003

Mu, T. C., Lin, Y. S., Pu, H. L., Keyhani, N. O., Dang, Y. X., Lv, H. J., et al. (2024). Molecular phylogenetic and estimation of evolutionary divergence and biogeography of the family Schizoparmaceae and allied families (Diaporthales, Ascomycota). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 201:108211. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2024.108211

Nasir, A. A., Syarif, N. Y., Omar, D., and Asib, N. (2023). Effectiveness of Cordyceps fumosorosea Wettable powder formulation against Metisa plana (Walker) and its side effects on Elaeidobius kamerunicus in oil palm plantation. J. Pestic. Sci. 48, 54–60. doi: 10.1584/jpestics.D22-072

Nguyen, L. T., Schmidt, H. A., von Haeseler, A., and Minh, B. Q. (2015). IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum likelihood phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 32, 268–274. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msu300

Nishi, O., Iiyama, K., Yasunaga-Aoki, C., and Shimizu, S. (2013). Comparison of the germination rates of Metarhizium spp. conidia from Japan at high and low temperatures. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 57, 554–560. doi: 10.1111/lam.12150

Nishi, O., and Sato, H. (2018). Isolation of Metarhizium spp. from rhizosphere soils of wild plants reflects fungal diversity in soil but not plant specificity. Mycology 10, 22–31. doi: 10.1080/21501203.2018.1524799

Paschapur, A. U., Subbanna, A. R. N. S., Singh, A. K., Jeevan, B., Stanley, J., Rajashekara, H., et al. (2022). Alternaria alternata strain VLH1: a potential entomopathogenic fungus native to North Western Indian Himalayas. Egypt. J. Biol. Pest. Co. 32:138. doi: 10.1186/s41938-022-00637-0

Pattemore, J. A., Hane, J. K., Wiliams, A. H., Wilson, B. A., Stodart, B. J., and Ash, G. J. (2014). The genome sequence of the biocontrol fungus Metarhizium anisopliae and comparative genomics of Metarhizium species. BMC Genomics 15:660. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-660

Phull, A. R., Ahmed, M., and Park, H. J. (2022). Cordyceps militaris as a bio functional food source: pharmacological potential, anti-inflammatory actions and related molecular mechanisms. Microorganisms 10:405. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms10020405

Rehner, S. A., and Samuels, G. J. (1994). Taxonomy and phylogeny of Gliocladium analysed from nuclear large subunit ribosomal DNA sequences. Mycol. Res. 98, 625–634. doi: 10.1016/S0953-7562(09)80409-7

Robinson, S. L., and Panaccione, D. G. (2015). Diversification of ergot alkaloids in natural and modified Fungi. Toxins 7, 201–218. doi: 10.3390/toxins7010201

Rogerson, C. T. (1970). The hypocrealean fungi (Ascomycetes, Hypocreales). Mycologia 62, 865–910. doi: 10.1080/00275514.1970.12019033

Ronquist, F., Teslenko, M., van der Mark, P., Ayres, D. L., Darling, A., Höhna, S., et al. (2012). MrBayes 3.2: Efcient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 61, 539–542. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/sys029

Saepua, S., Kornsakulkarn, J., Somyong, W., Laksanacharoen, P., Isaka, M., and Thongpanchang, C. (2018). Bioactive compounds from the scale insect fungus Conoideocrella tenuis BCC44534. Tetrahedron 74, 859–866. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2018.01.004

Steiner, U., Leibner, S., Schardl, C. L., Leuchtmann, A., and Leistner, E. (2011). Periglandula, a new fungal genus within the Clavicipitaceae and its association with Convolvulaceae. Mycologia 103, 1133–1145. doi: 10.3852/11-031

Sung, G. H., Hywel-Jones, N. L., Sung, J. M., Luangsa-ard, J. J., Shrestha, B., and Spatafora, J. W. (2007). Phylogenetic classification of Cordyceps and the clavicipitaceous fungi. Stud. Mycol. 57, 5–59. doi: 10.3114/sim.2007.57.01

Thanakitpipattana, D., Tasanathai, K., Mongkolsamrit, S., Khonsanit, A., Lamlertthon, S., and Luangsa-ard, J. J. (2020). Fungal pathogens occurring on Orthopterida in Thailand. Persoonia 44, 140–160. doi: 10.3767/persoonia.2020.44.06

Vilgalys, R., and Hester, M. (1990). Rapid genetic identification and mapping of enzymatically amplified ribosomal DNA from several Cryptococcus species. J. Bacteriol. 172, 4238–4246. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.8.4238-4246.1990

Wang, Z. Q., Ma, J. M., Yang, Z. L., Zhao, J., Yu, Z. Y., Li, J. H., et al. (2024). Morphological and phylogenetic analyses reveal three new species of Entomopathogenic Fungi belonging to Clavicipitaceae (Hypocreales, Ascomycota). J. Fungi 10:423. doi: 10.3390/jof10060423

Wang, Y. B., Yu, H., Dai, Y. D., Wu, C. K., Zeng, W. B., Yuan, F., et al. (2015). Polycephalomyces agaricus, a new hyperparasite of Ophiocordyceps sp. infecting melolonthid larvae in southwestern China. Mycol. Prog. 14:70. doi: 10.1007/s11557-015-1090-7

Zhang, Z. Y., Feng, Y., Tong, S. Q., Ding, C. Y., Tao, G., and Han, Y. F. (2023). Morphological and phylogenetic characterisation of two new soil-borne fungal taxa belonging to Clavicipitaceae (Hypocreales, Ascomycota). Myco Keys 98, 113–132. doi: 10.3897/mycokeys.98.106240

Zhang, D., Gao, F. L., Jakovlić, I., Zou, H., Zhang, J., Li, W. X., et al. (2020). PhyloSuite: an integrated and scalable desktop platform for streamlined molecular sequence data management and evolutionary phylogenetics studies. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 20, 348–355. doi: 10.1111/1755-0998.13096

Zhao, Z. Y., Mu, T. C., Keyhani, N. O., Pu, H. L., Lin, Y. S., Lv, Z. Y., et al. (2024). Diversity and new species of Ascomycota from bamboo in China. J. Fungi 10:454. doi: 10.3390/jof10070454

Keywords: entomopathogenic fungi, Albacillium, Conoideocrella, Metarhizium, Neoaraneomyces, Clavicipitaceae, new taxa

Citation: Lin L, Lin Y, Keyhani NO, Pu H, Yang J, Xiong C, Shang J, Mao Y, Yang L, Zheng M, Zhu M, Mu T, Li Y, Liang H, Fan L, Ma X, Ma H, Xiong W, Qiu J and Guan X (2025) New entomopathogenic species in the Clavicipitaceae family (Hypocreales, Ascomycota) from the subtropical forests of Fujian, China. Front. Microbiol. 16:1532341. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2025.1532341

Received: 21 November 2024; Accepted: 10 January 2025;

Published: 03 March 2025.

Edited by:

Wen-Jun Li, Sun Yat-sen University, ChinaReviewed by:

Guohua Xiao, Sanda University, ChinaCopyright © 2025 Lin, Lin, Keyhani, Pu, Yang, Xiong, Shang, Mao, Yang, Zheng, Zhu, Mu, Li, Liang, Fan, Ma, Ma, Xiong, Qiu and Guan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xiayu Guan, Z3h5MzAyQDEyNi5jb20=; Junzhi Qiu, anVuemhpcWl1QDEyNi5jb20=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.