- 1Department of Plant Medicine, National Chiayi University, Chiayi, Taiwan

- 2Biotechnology Center in Southern Taiwan, Academia Sinica, Tainan, Taiwan

- 3Agriltural Biotechnology Research Center, Academia Sinica, Taipei, Taiwan

Introduction: Bacterial spot, caused by diverse xanthomonads classified into four lineages within three species, poses a significant threat to global pepper and tomato production. In Taiwan, tomato bacterial spot xanthomonads phylogenetically related to an atypical Xanthomonas euvesicatoria pv. perforans (Xep) strain NI1 from Nigeria were found.

Methods: To investigate the genetic structure of Taiwanese Xep strains and determine the phylogenetic position of the atypical strains, we completed high-quality, gap-free, circularized genomes of seven Taiwanese Xep strains and performed comparative genomic analyses with genomes of X. euvesicatoria pathovars. Average nucleotide identity, core genome analysis, and phylogenomic analysis were conducted.

Results: Three sequenced strains were identified as typical Xep, while four clustered with the atypical strain NI1, forming a distinct genomovar within X. euvesicatoria, proposed as X. euvesicatoria genomovar taiwanensis (Xet). This new lineage likely originated in Taiwan and spread to Nigeria through global seed trade. At the genomovar level, chromosomes remained conserved among Taiwanese strains, while plasmids likely contributed to bacterial virulence, avirulence, and field fitness. Gap-free genomes revealed associations between the evolution of type III effectors, horizontal gene transfer events, plasmid diversity, and recombination.

Discussion: This study highlights the critical roles of horizontal gene transfer and plasmids in shaping the genetic makeup, evolution, and environmental adaptation of plant pathogenic xanthomonads. The identification of a new genomovar, X. euvesicatoria genomovar taiwanensis, provides insights into the diversity and global spread of bacterial spot pathogens through seed trade.

Introduction

Bacterial spot disease, caused by various species of the genus Xanthomonas, poses a significant threat to global tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) and pepper (Capsicum spp.) production, leading to considerable economic losses (Osdaghi et al., 2021). Although precise estimates of economic losses are scarce, it is estimated that annual damages caused by Xanthomonas in tomato can range from $3,000 to $7,000 USD per hectare in Florida and could exceed $7.8 million USD during an outbreak in Northwest Ohio and Southeast Michigan alone.1 Yield reductions of up to 66% under favorable conditions have been reported in United States (Pohronezny and Volin, 1983). In Taiwan, bacterial spot is a prevalent issue in tomato cultivation, affecting crop yield and quality (Leu et al., 2010).

The genus Xanthomonas spp. represents a large group of plant pathogenic gram-negative bacteria, with more than 400 plant hosts recorded as susceptible to xanthomonads (Timilsina et al., 2020). In particular, bacterial spot poses a significant threat to global pepper and tomato production (Osdaghi et al., 2021). The complexity of this disease from the perspective of the pathogen is considerable. Initially, causal xanthomonads were thought to consist of two genetically distinct clonal groups; however, later studies identified four distinct groups (Jones et al., 2004). Currently, bacterial spot-causing Xanthomonas spp. are classified into four distinct lineages within three species: Xanthomonas euvesicatoria pv. euvesicatoria (Xee), X. euvesicatoria pv. perforans (Xep), X. hortorum pv. gardneri, and X. vesicatoria, based on phylogenomic analysis of whole genome sequences (Jones et al., 2004; Constantin et al., 2016; Osdaghi et al., 2021).

Among these lineages, Xep is particularly diverse, with new phylogenetic groups being continuously identified (Abrahamian et al., 2021). For example, Xep strains collected in Florida during the 1990s were initially classified into a single phylogenetic group (Schwartz et al., 2015; Timilsina et al., 2019), but six distinct phylogenetic groups were recognized among Florida strains by 2017 (Newberry et al., 2019; Abrahamian et al., 2021). Australian Xep strains form unique phylogenetic clusters that are distinct from those found in other regions (Roach et al., 2019). Beyond these well-characterized lineages, atypical Xep strains causing tomato bacterial spot have been identified in Nigeria since 2012 (Jibrin et al., 2015; Timilsina et al., 2015; Jibrin et al., 2018; Jibrin et al., 2022). Both atypical and typical Xep strains are amylolytic, and no differences in phenotypic characteristics between atypical and typical Xep strains have been reported (Jibrin et al., 2015). Genetically, these atypical strains can be distinguished by multilocus sequence analysis (MLSA) and phylogenetic analysis of gapA sequences (Timilsina et al., 2015; Timilsina et al., 2016). Moreover, the core genome phylogeny and pangenomic analysis suggest the atypical Nigerian strain NI1 was intermediate between Xee and typical Xep strains but more closely related to X. euvesicatoria pv. allii (Jibrin et al., 2018). Comparative genomic analysis further revealed that the atypical Nigerian strain NI1 differed from typical Xep strains in the composition of the type four secretion system and lipopolysaccharide biosynthetic gene clusters (Jibrin et al., 2022). MLSA results and draft genome comparisons of Nigerian strain NI1 suggested that these atypical Xep strains may have evolved through recombination between Xee and Xep (Timilsina et al., 2015; Jibrin et al., 2018). Core genome phylogeny indicated that strain NI1, along with six Xep strains isolated from peppers in Taiwan in 2019, formed a cluster named TP-2019 (Parajuli et al., 2024). However, no tomato strains of Xep have been identified in Taiwan in this cluster (Chen et al., 2024).

In Taiwan, bacterial spot on tomatoes and peppers is predominantly caused by Xee and Xep (Leu et al., 2010; Constantin et al., 2016). There has been a notable transition in bacterial spot xanthomonad populations in Taiwan. Burlakoti et al. (2018) reported that all pepper strains and 95% of tomato strains collected between 1989 and 1999 were Xee, with no Xep strains found during this period. Although Xep was first reported in tomatoes in Taiwan in 2010 (Leu et al., 2010), 22% of the tomato strains collected by the World Vegetable Center between 2000 and 2009 were identified as Xep (Burlakoti et al., 2018). Since 2010, Xep has become the dominant causal agent of tomato spot disease in Taiwan, with 99% of the tomato strains identified as Xep (Burlakoti et al., 2018).

Despite the prevalence of Xep, recent studies have revealed limited genetic diversity among Taiwanese Xep strains. Analysis of the draft genome assemblies of 11 Xep strains from Taiwan showed no evidence of recombination with other tomato bacterial spot Xanthomonas species, indicating a narrow genetic background (Chen et al., 2024). Interestingly, based on the gapA phylogeny, we found that several Xep strains isolated in Taiwan since 1996 were phylogenetically close to the representative atypical strain NI1. Understanding the genetic diversity and evolutionary relationships of these atypical strains is crucial for accurate pathogen identification, disease management, and elucidation of the mechanisms underlying their pathogenicity and adaptation. However, there is limited information regarding the complete genome composition of Xep in Taiwan.

In this study, we aimed to obtain high-quality complete genomes of atypical Xep strains from Taiwan and clarify their phylogenetic position within diverse lineages of X. euvesicatoria through comparative genomic analysis. Specifically, we sought to decipher the genetic basis of the so-called Xep by analyzing the complete genome sequences of seven strains collected over different years and regions in Taiwan, including four copper-resistant (CuR) strains. The high-quality genome assemblies and annotations of these seven strains were compared with those of other X. euvesicatoria genomes through genome analysis to reveal their phylogenetic positions and genetic diversity. Based on our findings, we propose classifying this new lineage as X. euvesicatoria genomovar taiwanensis (Xet). By analyzing completely circularized genome assemblies, we provided detailed insights into plasmid composition, evidence of recombination and horizontal gene transfer, and the evolution of virulence factors in the sequenced genomes.

Materials and methods

Collection of strains

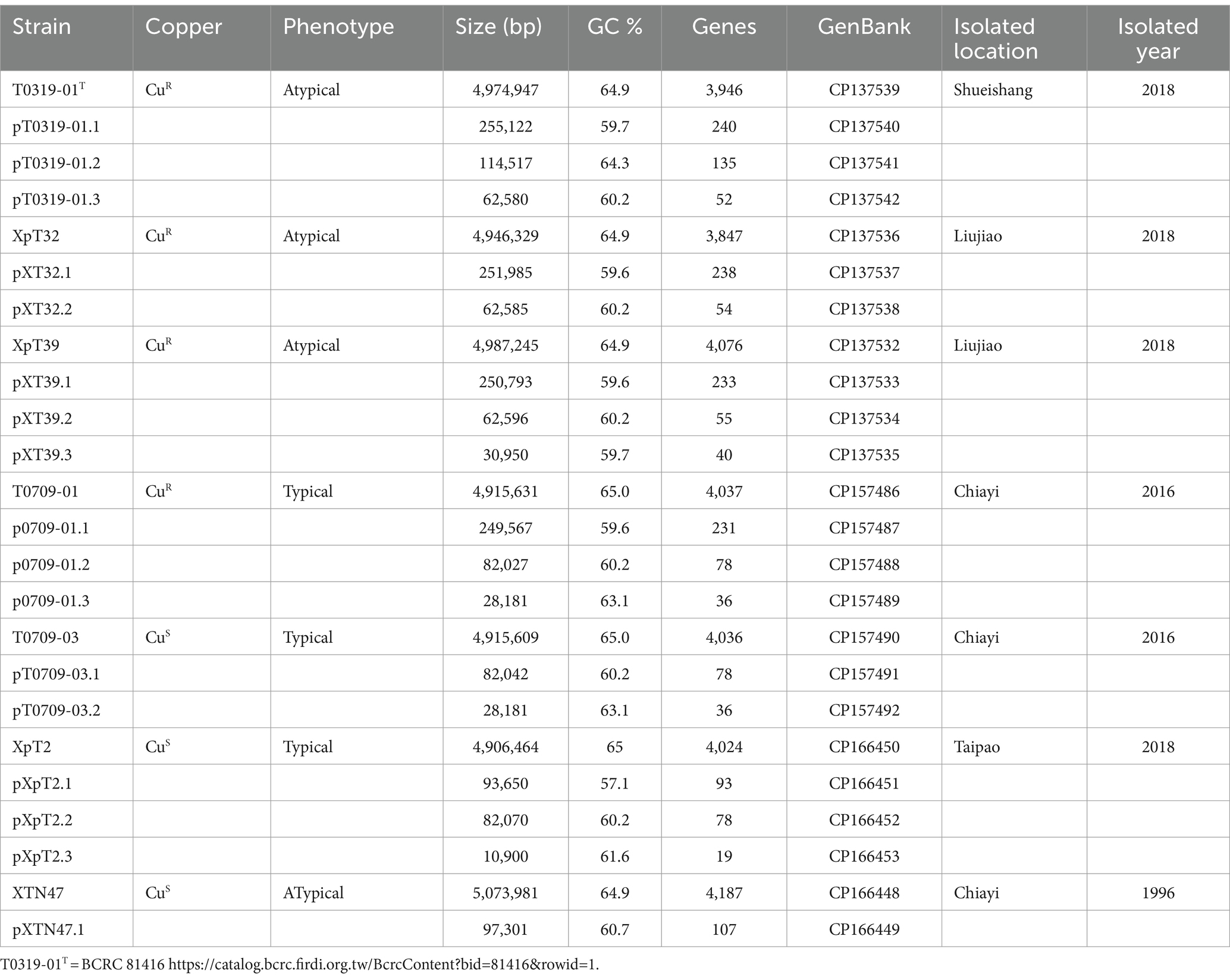

Seven originally identified Xep strains were selected based on the year and location of isolation (Lai et al., 2021). Two strains, T0709-01 and T0709-03, were isolated in 2016, and four strains, T0319-01, XpT2, XpT32, and XpT39, were isolated in 2018. An Xep isolate, XTN47, obtained in 1996 (Leu et al., 2010), was included in this study. Strains XTN47, T0709-01, and T0709-03 were obtained from Chiayi, T0319-01 from Shueishang, XpT2 from Taipao, and XpT32 and XpT39 from Liujiao. All strains were isolated from tomato leaves with symptoms of bacterial spot, and their pathogenicity was confirmed by fulfilling Koch’s postulates (Table 1).

Nanopore and Illumina sequencing

Genomic DNA (gDNA) from the seven strains was prepared using the NautiaZ Bacteria/Fungi DNA Mini Kit (Nautia Gene, Taipei, Taiwan). The quality of the gDNA was estimated using a Qubit fluorometer (Qiagen), and the fragment size was measured using a capillary electrophoresis instrument TapeStation (Agilent Technologies). Sheared gDNA was selected using BluePippin with a 0.75% agarose gel cassette (Sage Science) to obtain gDNA fragment sizes ranging from 6 to 20 kb. Nanopore sequencing libraries were prepared using the PCR-free ligation-based sequencing kit (SQK-LSK109) with native barcoding expansion (EXP-NBD104) for sample multiplexing. Nanopore sequencing was performed using an Oxford Nanopore GridION device (R9.4 flow cell FLO-MIN106D). In total, we obtained 161 K–183 K Nanopore reads for each strain, with an average Nanopore read length of 8,875 bp and an L50 of 48,138 bp (Supplementary Table S1). For the Illumina sequencing, genomic DNA libraries were prepared for high-throughput sequencing using the Illumina DNA Prep Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, United States). Whole-genome shotgun sequencing was performed using an Illumina NovaSeq 6,000 platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, United States) to generate 150 bp paired-end reads. Sequencing depth achieved an average of 2.8–3.1 million paired-end reads per genome (Supplementary Table S1).

Genome assembly and gene annotation

Sequencing read quality was evaluated using FASTQC (v.0.11.9) (Andrews et al., 2023). Low-quality reads were subsequently removed using TRIMMOMATIC (v.0.36) (Bolger et al., 2014) for Illumina reads and NANOFILT (v.2.6.0) (De Coster et al., 2018) for Nanopore reads. The base quality of Nanopore reads greater than 1 kb was further improved by the corresponding high-quality Illumina reads using FMLRC (v.1.0.0) (Wang et al., 2018). Each strain was assembled using three different assemblers, CANU (v.1.8) (Koren et al., 2017), Flye (v.2.5) (Kolmogorov et al., 2019), and WTDBG2 (v.2.5) (Ruan and Li, 2020), for their ability to handle repetitive regions. The draft assemblies for each strain were then compared and merged using BLASTN (v.2.10.1) (Camacho et al., 2009) with manual inspection to produce a consensus assembly. The per-base accuracy of the assemblies was improved using PILON (Wang et al., 2014) with high-quality Illumina reads. On average, the final coverage of the assembled genomes exceeded 200X. Genomic sequences of the seven strains were resolved on a single circular chromosome. All plasmid sequences were fully circularized. Genome assembly quality in terms of completeness and contamination was assessed based on the presence and duplication of marker genes using CHECKM (Parks et al., 2015) and BUSCO (v5.5.0, −l xanthomonadales_odb10) (Manni et al., 2021) (Supplementary Table S1).

To facilitate whole-genome comparison, the dnaA gene was set as the start of the complete genome assembly. Three conserved DnaA boxes have been identified in the oriC region between dnaA and dnaN (da Silva et al., 2002; Yen et al., 2002; Qian et al., 2005). The terminator of replication for each strain was located at approximately 2.5 Mb of the chromosome sequence. Replichores of the three strains were identified using a GC skew plot.

Genome annotation was performed using the local installation of the NCBI Prokaryotic Genome Annotation Pipeline (PGAP) (Tatusova et al., 2016), followed by manual curation. Specifically, the Docker image of PGAP (v.2019-08-22.build3958) was used for the initial genome annotation. The annotations generated by PGAP were then manually inspected using ARTEMIS (Carver et al., 2012) to verify the correctness of the start and stop codons, among other features. A comparative analysis with published X. euvesicatoria genomes was conducted using BLASTP (Camacho et al., 2009) to further refine and validate the annotations.

Despite the publication of the first Xanthomonas genome (X. citri 306) (da Silva et al., 2002) in 2002, followed by numerous subsequent genome sequences and studies, a significant portion of the genome remains functionally uncharacterized. To enhance functional annotation, we used a combined approach with UniProt (Coudert et al., 2023), Blast2GO (Gotz et al., 2008), and Intrproscan (Jones et al., 2014). However, this combined strategy resulted in approximately 20% of the protein-coding genes remaining classified as hypothetical, indicating an unknown function.

Whole genome comparison and gene family analysis

Two complementary approaches based on the diversity of nucleotide sequences and protein-coding genes have been used for genome-wide analyses to understand overall genome variations. The assembled chromosome and plasmid sequences were compared with published 132 Xanthomonas genomes (Supplementary Table S2) to identify conserved and novel sequence elements (Barak et al., 2016; Constantin et al., 2016; Bansal et al., 2018; Fan et al., 2022). The whole-genome similarity metrics of all strains were estimated using the alignment-free approximate sequence mapping algorithm FASTANI (v.1.20) (Jain et al., 2018), with default settings. To confirm the taxonomic nomenclature and classification of these strains, genome-based taxonomy was performed using the GGDC database (Meier-Kolthoff et al., 2022).

To further understand the evolution of protein-coding genes in the Xanthomonas genomes, we analyzed genes from 139 Xanthomonas strains (Supplementary Table S2) to infer orthologous relationships using the Markov Cluster Algorithm (MCL) (Enright et al., 2002). Briefly, genes were compared using all-against-all BLASTP (e-value 10−5) (Camacho et al., 2009), and the results were analyzed using the scalable unsupervised cluster algorithm MCL (inflation value 5). Orthologous and paralogous relationships are presented as networks based on e-values. MCL clustering resulted in 8,580 gene families, which were presented as a gene number matrix of 139 genomes. Gene families present in more than one genome were considered the ′pan-genome′ whereas those shared in at least two genomes were considered the ′core-genome′ (Méric et al., 2014).

A total of 1,346 orthologous genes with a strict one-to-one relationship as the ′single copy core gene′ in 139 Xanthomonas strains were used to construct the phylogenetic tree. Multiple sequence alignments of the protein sequences in these single-copy core genes were individually performed using MUSCLE (Edgar, 2004), and gaps in the alignments were removed using TRIMAL (Capella-Gutiérrez et al., 2009). Individual sequence alignments were concatenated to create a single protein sequence for each strain. Maximum likelihood phylogenetic trees were inferred using RAXML-NG (Kozlov et al., 2019) with 1,000 bootstrap replicates (v.1.0.1, −model LG + G8 + F –seed 2 –bs-trees 1,000) and visualized using FIGTREE.2 Genome collinearity analysis was performed using I-ADHORE 3.0 (Proost et al., 2012) to infer the syntenic regions.

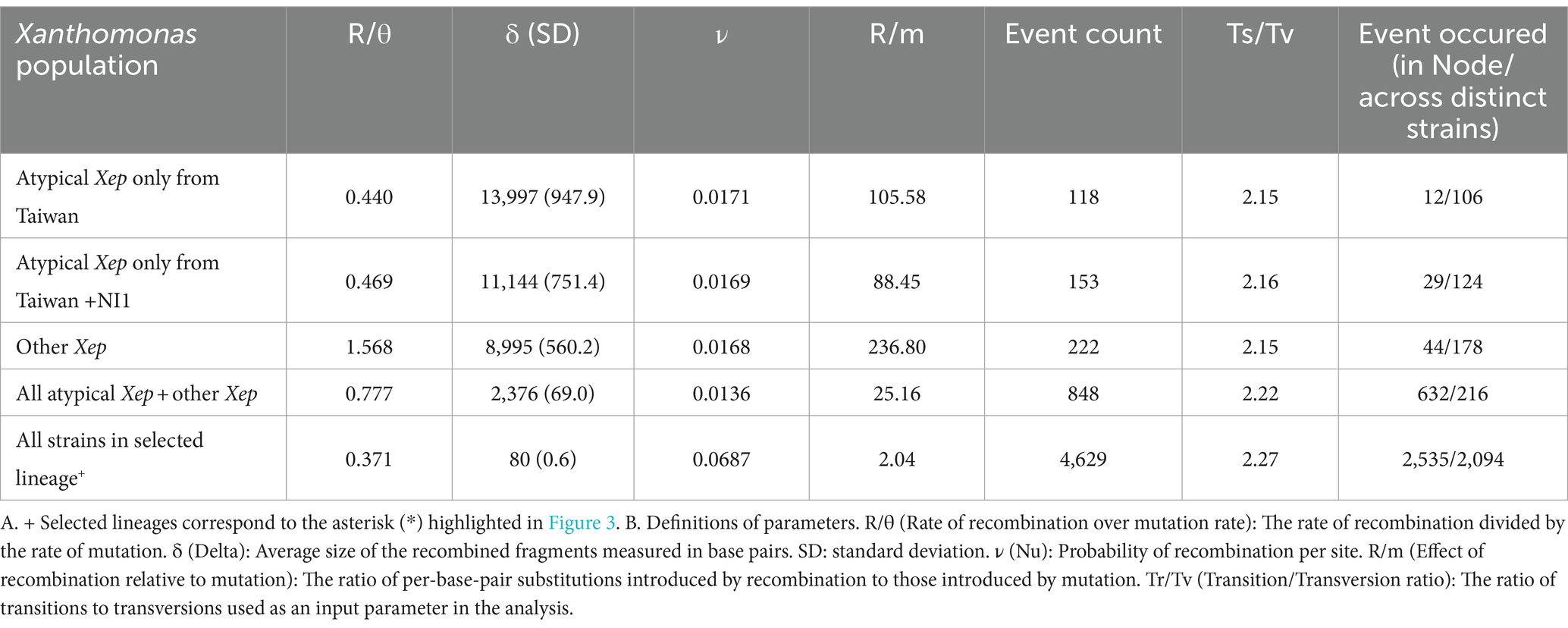

Analysis of homologous recombination

We analyzed homologous recombination among X. euvesicatoria strains using CLONALFRAMEML (v1.13; Didelot and Wilson, 2015). The phylogenetic tree used as the starting topology was constructed based on single-copy core genes. Protein alignments were back-translated to coding DNA sequence (CDS) alignments, and phylogeny was inferred using RAXML-NG (Kozlov et al., 2019) with 1,000 bootstrap replicates (v.1.2.0, −model GTR + G –seed 2 –bs-trees 1,000). Pangenome alignment was performed using CACTUS (v2.7.0; Hickey et al., 2024). Transition/transversion ratios were determined using CACTUS alignment. Recombination parameters were calculated in CLONALFRAMEML using the hidden Markov model (HMM) with 100 simulations (emsim = 100) to enhance the reliability of the analysis. Additionally, we calculated the impact of introduced recombination events relative to single-point mutations (r/m) for each branch in CLONALFRAMEML. Analyses were conducted using different combinations of strains, as shown in Table 2.

Phenotypic characterization

The biochemical characteristics of the strains were determined using a Biolog GEM III MicroPlate system (Biolog, Hayward, CA, United States). The amylolytic activity of the strains was tested on nutrient agar (NA; Difco) plates containing 1.5% soluble starch, as described by Stall et al. (1994).

A copper sensitivity test was performed according to the method described by Lai et al. (2021). The three strains were cultured overnight on NA plates and streaked on NA plates supplemented with 0, 0.1, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.7, 0.8, 1.6, and 3.2 mM CuSO4. Stains sensitive, tolerant, or resistant to copper were differentiated by their ability to grow on NA plates with maximum concentrations of ≤0.6, 0.6–0.8 and ≥ 0.8 mM CuSO4, respectively, as rated by Behlau et al. (2013) and Marin et al. (2019).

Horizontal transfer of copper resistance genes

The horizontal transfer of CuR genes between different xanthomonad strains was tested according to the method described by Behlau et al. (2012). Strain T0319-01, with copper resistance and rifampicin sensitivity, was used as the donor. Spontaneous rifampicin-resistant mutants of the CuS strain XTN47Rif were used as recipients. The bacterial strains were mated on NA plates at 28°C for 24 h. After mating, the bacterial cells were scraped, suspended, and plated at dilutions on NA supplemented with rifampicin (50 mg/L) to estimate the recipient population. To select transconjugants, bacterial suspensions were plated at dilutions on NA supplemented with rifampicin (50 mg/L) and 0.8 mM CuSO4. The conjugation frequency was calculated as the ratio of the number of transconjugants to the recipient population (Behlau et al., 2012).

Results

Genome sequence of seven tomato bacterial spot xanthomonad strains

To investigate the evolutionary divergence and better understand the genomic basis of Taiwanese X. euvesicatoria pv. perforans (Xep) strains, we performed whole-genome sequencing of seven Xep strains collected from different locations during 1996–2018 (Table 1). Three typical Xep strains (T0709-01, T0709-03, and XpT2) and four atypical Xep strains (XpT32, XpT39, T0309-01, and XTN47 (Leu et al., 2010)) were selected. Among these, one typical strain and three atypical strains were characterized as CuR strains, capable of growing on NA plates supplemented with 0.8 mM CuSO (Lai et al., 2021). Conversely, two other typical Xep strains, T0709-03 and XpT2, and an atypical strain isolated in 1996, XTN47, were sensitive to copper.

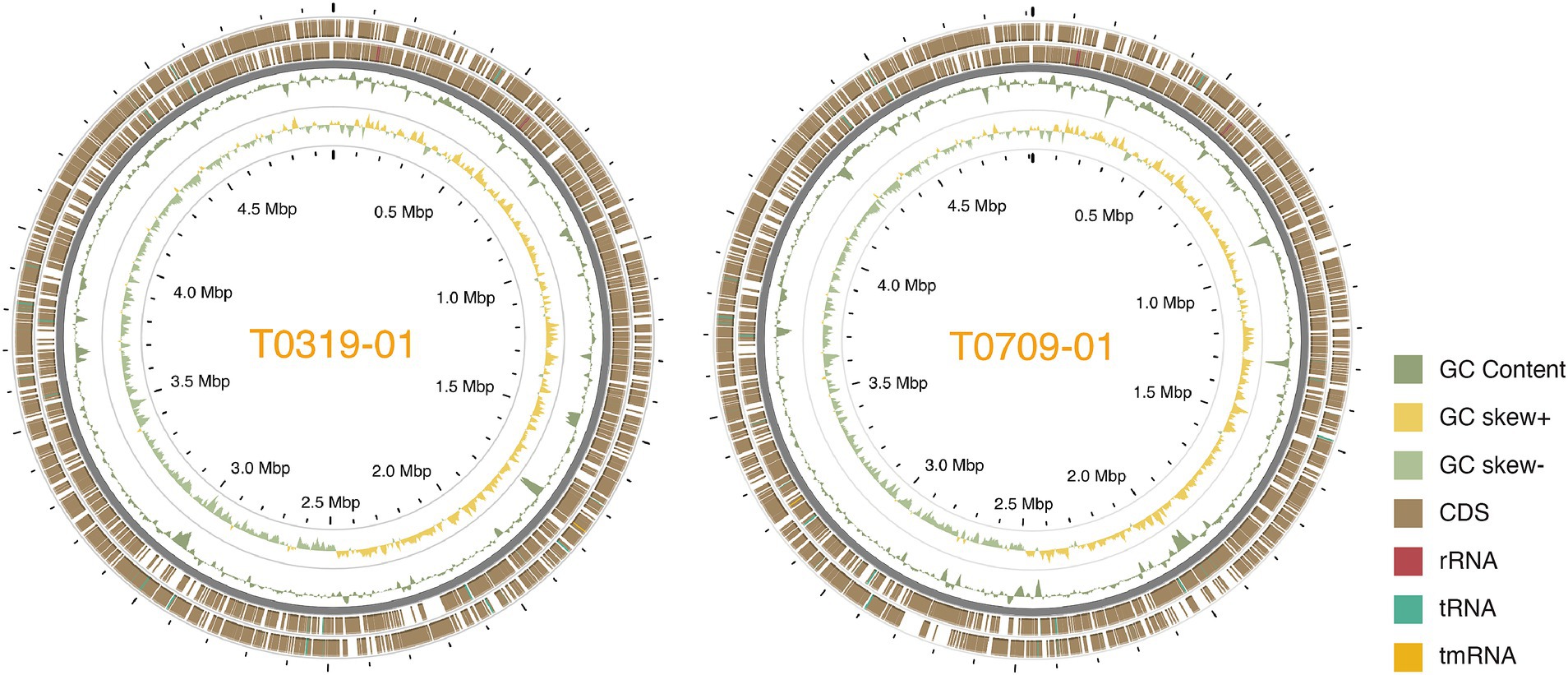

We used a hybrid assembly approach that combined short-read (Illumina) and long-read (Oxford Nanopore) sequencing technologies in an integrated bioinformatics workflow (Huang et al., 2021). This method allowed us to complete the genomes of all seven strains into gap-free and circularized chromosomes and plasmid sequences (Figure 1). The assembled genome sizes of the seven strains showed little variation, ranging from 4.915 to 5.073 Mb, with a consistent GC content between 64.9 and 65.0%. Gene prediction analysis identified between 4,100 and 4,289 genes per strain, including rRNA genes and pseudogenes. These values are comparable to those of previously published X. euvesicatoria genomes (Timilsina et al., 2020; Tables 1; Supplementary Table S1). To assess the quality of the genome assemblies, we evaluated metrics such as coverage depth, contiguity, base accuracy, CheckM (Parks et al., 2015), and BUSCO (Manni et al., 2021). The final assembled genomes achieved depths exceeding 200×, ensuring high confidence in assembly accuracy (Supplementary Table S1). CheckM and BUSCO were used to determine genome completeness and contamination. The hybrid approach enhanced assembly contiguity and accuracy, particularly in resolving repetitive regions and plasmid sequences. We identified 1–3 plasmids in each strain, both in the typical and atypical Xep strains. The plasmid size varied substantially, ranging from 10 kb to over 255 kb. Notably, all plasmid sequences were completely circularized (Supplementary Table S1), providing a comprehensive view of the plasmid architecture in these strains.

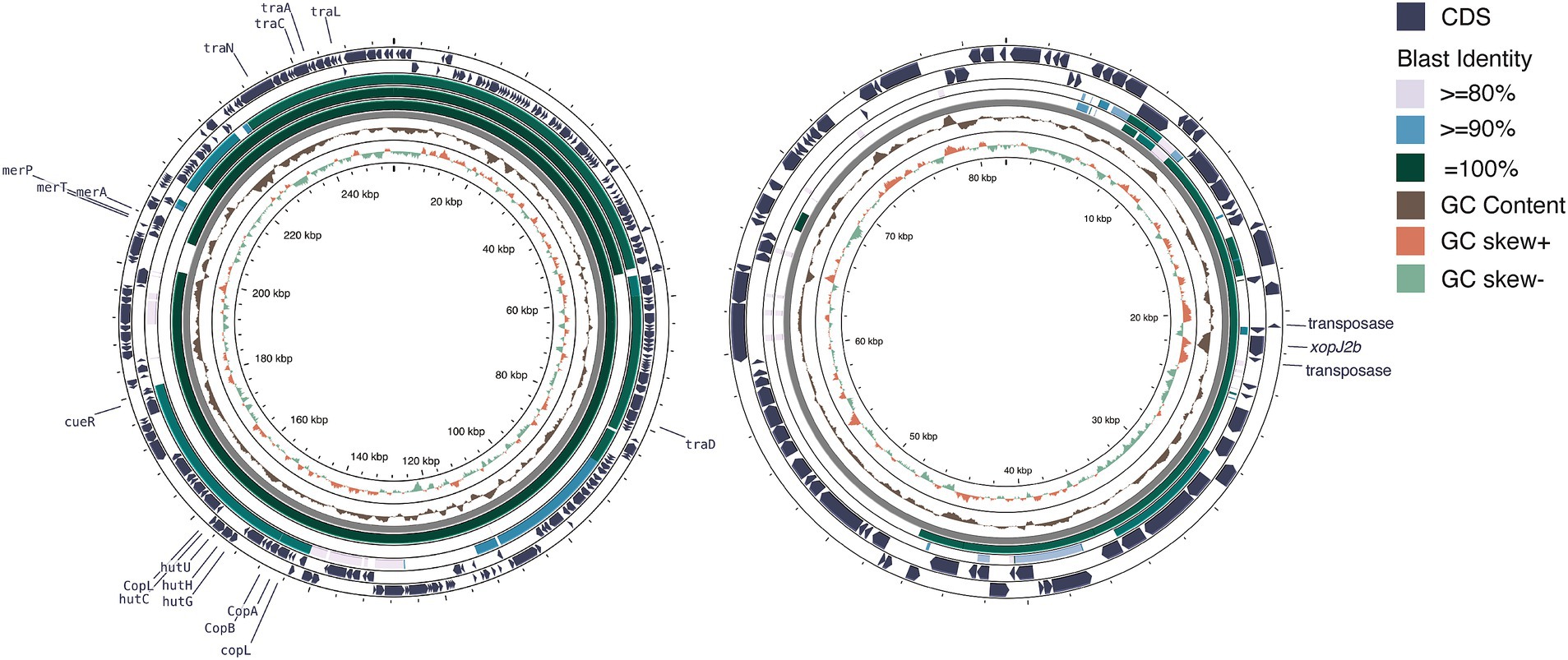

Figure 1. Circos plot of the two Taiwanese Xep strains. The outermost two layers represent coding sequences (CDS) on both strands. The next layer shows the GC content, followed by the GC skew of the fourth layer. The innermost layer represented the grid. The GC content and skew were calculated using a window size of 10 kb and a step size of 100 bp.

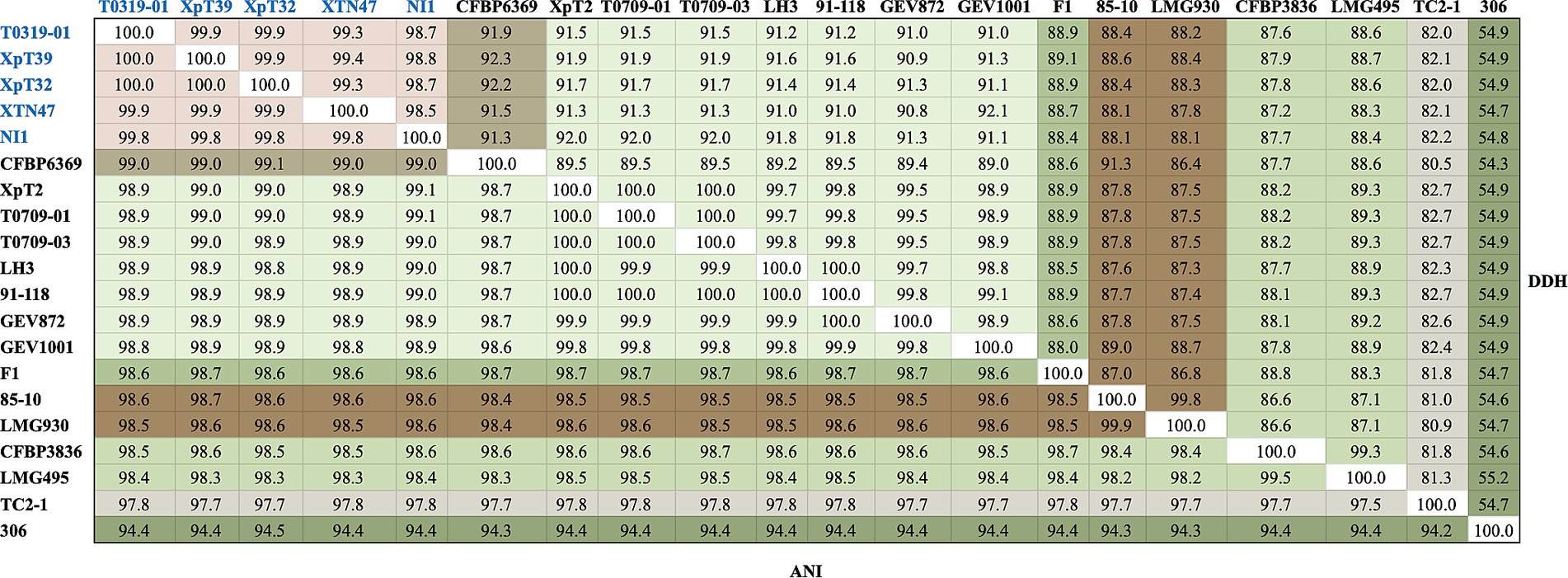

Low nucleotide sequence divergence of Taiwanese Xep strains

To clarify the phylogenetic positions and genetic diversity of the sequenced Taiwanese Xep strains, we used multiple complementary approaches to analyze their genome sequences. We compared the average nucleotide identity using FASTANI (v.1.2) (Jain et al., 2018) and digital DNA–DNA hybridization (dDDH) (Meier-Kolthoff et al., 2022) of 139 strains, including Xep reference strain 91–118 and Xanthomonas euvesicatoria pv. euvesicatoria (Xee) reference strain 85–10 (Supplementary Table S2). The commonly accepted thresholds for species delineation are ANI ≥ 95% and dDDH ≥70% (Chun et al., 2018). The three typical Xep strains from Taiwan (XpT2, T0709-01, and T0709-03) and strain 91–118 had ANI scores of 100.0% and dDDH values of 99.8–100.0%, indicating great similarity in their genomes (Figure 2). These findings are consistent with those of previous studies (Barak et al., 2016; Constantin et al., 2016; Bansal et al., 2018; Jibrin et al., 2018; Fan et al., 2022), indicating that Xep differs from Xee based on an ANI score > 98.5% and a dDDH value >87.3% (Figure 2).

Figure 2. FastANI and dDDH analyses of the selected strains. Strains of the taiwanensis lineage are marked in blue, whereas different species are marked in various colors. The complete FastANI and dDDH analyses of 139 strains are shown in Supplementary Figure S1.

Surprisingly, the four atypical strains sequenced in this study (T0319-01, XpT39, XpT32, and XTN47) and the Nigerian strain NI1 had ANI scores of 99.8–100.0% and dDDH values of 98.6–100.0%, revealing high similarity among their genomes (Figure 2). These four strains were the most closely related to X. euvesicatoria pv. allii CFBP6369 when compared with other X. euvesicatoria strains. The ANI scores between the four strains were 99.0–99.1% and the dDDH values were 91.3–92.3%, supporting the results of the phylogenomic analysis (see Phylogenomics analysis). Additionally, the four strains had ANI scores of 98.5–98.6% and dDDH values of 88.0–88.4% compared to Xee strains, and ANI scores of 98.8–99.0% and dDDH values of 90.7–91.8% compared to Xep strains (Figure 2).

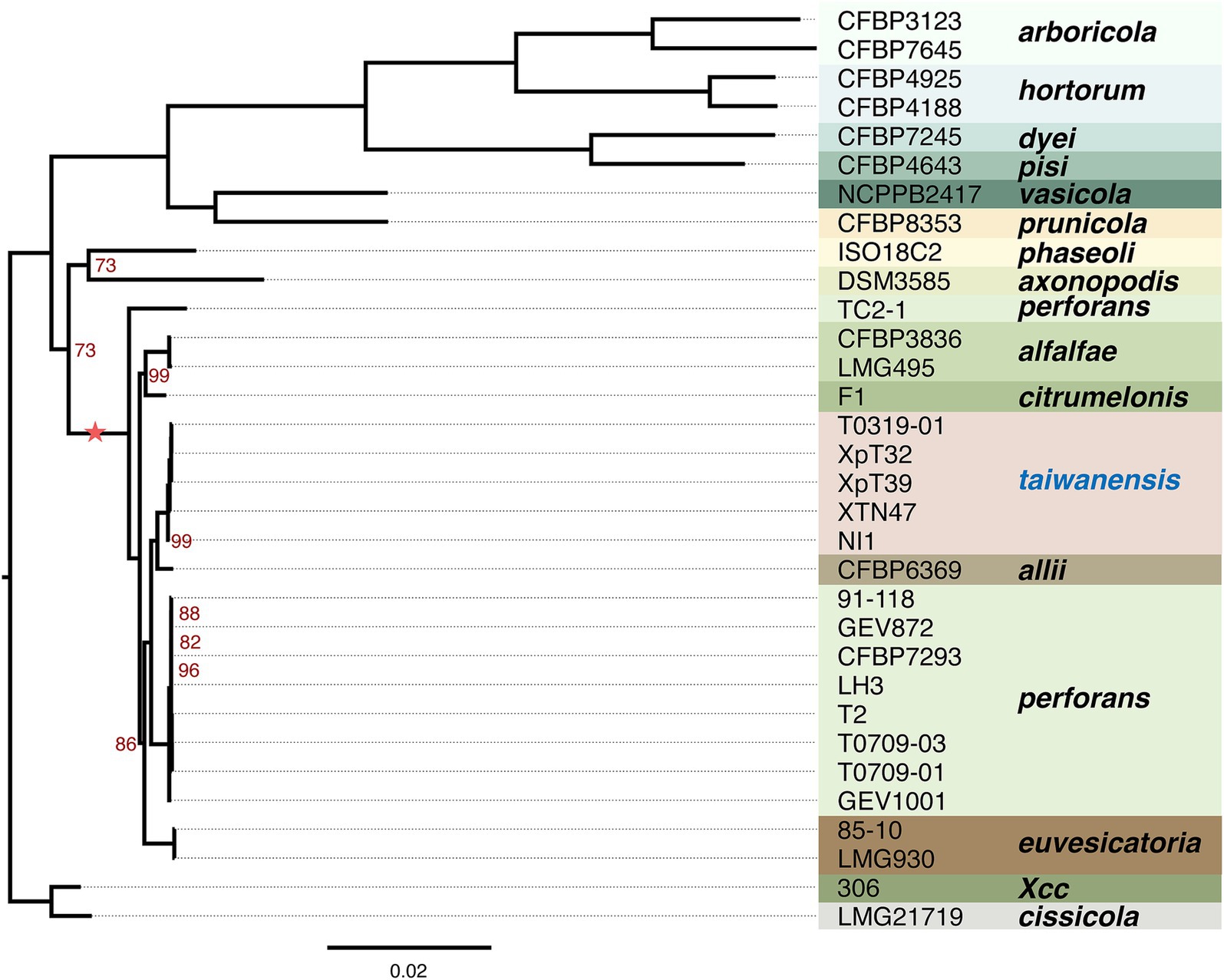

Phylogenomics analysis confirmed the phylogenic positions

To further understand the phylogenetic positions of these Taiwanese Xep strains and their relationship with other pathovars of X. euvesicatoria, we compared the protein-coding genes across 139 strains. Using the ortholog inference method Markov Cluster Algorithm (MCL) (Enright et al., 2002), 8, 580 gene families were identified. Based on the presence or absence of gene families in each genome, we identified 1,642 core gene families (present in all strains, regardless of copy number) and a pangenome of 6,938 gene families (present in at least one strain) (Figure 3; Supplementary Figure S2). For phylogenetic analysis, 1,346 orthologous genes with a strict one-to-one single-copy relationship were used to construct the phylogenetic tree. In agreement with the nucleotide sequence comparison, the three typical Xep strains of this study (XpT2, T0709-01 and T0709-03) formed a well-supported clade with published Xep strains, including the reference strain 91–118, and were separated from Xee. On the other hand, the four atypical Xep strains of this study (T0319-01, XpT39, XpT32, and XTN47) and seven published strains (XVP-272, XVP-270, XVP-273, XVP-271, XVP-267, XVP-265 and Xant-477) (Chen et al., 2024) that were also collected in Taiwan and the atypical Xep strain NI1 from Nigeria formed a separate branch on the phylogenetic tree (Figure 3; Supplementary Figure S2). This suggests that, together with the published NI1 genome, these strains form a new lineage of X. euvesicatoria. This new lineage is phylogenetically closer to X. euvesicatoria pv. allii than to Xep (Figure 3; Supplementary Figure S2).

Figure 3. Phylogenetic analysis. The maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree was constructed based on concatenated core genes from 1,346 single-copy genes across 32 genomes rooted in X. citri subsp. citri strain 306. The scale bar represents substitutions per site. The tree was generated using RAXML-NG with 1,000 bootstrap replicates. Branch support values of less than 100% are indicated by red numbers. The complete phylogenetic analysis of the 139 genomes is provided in Supplementary Figure S2. The asterisk indicates the lineage used in recombination analysis.

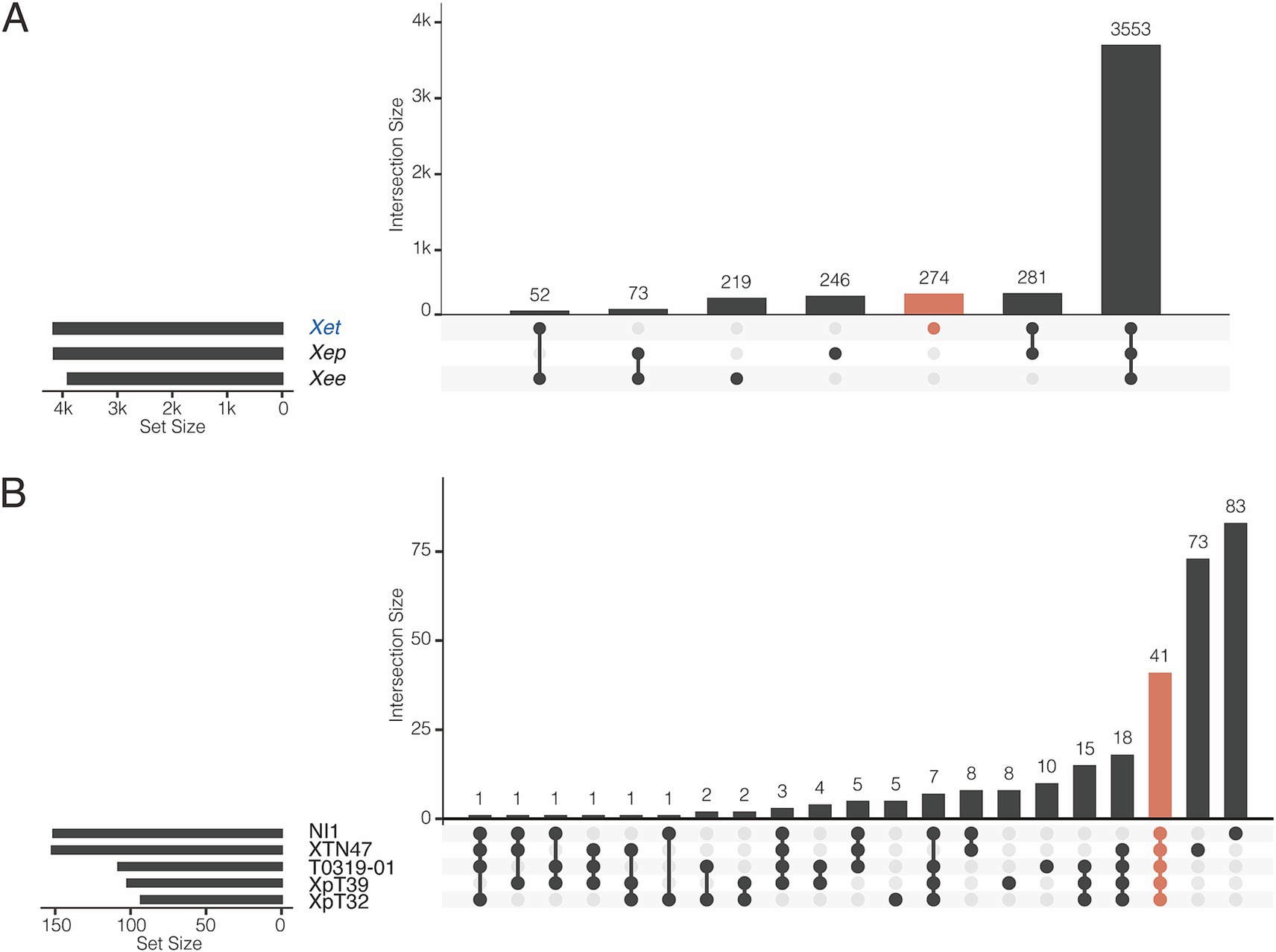

We further studied the presence and absence of variations in gene families among Xee, Xep, and the new lineages (Figure 4; Supplementary Figures S3, S4). In total, 3,553 gene families were shared among the three lineages and comprised the core genome (Figure 4A). The new lineage had more unique gene families (274 gene families) than did the other two lineages (219 and 246 in Xee and Xep, respectively). The number of gene families shared between the new lineage and Xep (281) is much higher than those shared between the new lineage and Xee (52) or between Xee and Xep (73). Gene families unique to the new lineage were further analyzed (Figure 4B; Supplementary Figure S4). Of the 274 lineage-specific genes, a limited number were shared between two or more strains, and 41 genes (15%) were shared by five strains. Strains XTN47 and NI1 had 73 and 83 unique genes, respectively, but only 5–8 unique genes were found in each of the other three strains (Figure 4B). The lineage-specific genes in the new Xep strains were functionally diverse, with many being involved in key biological processes, such as recombinational repair (GO:0000725), carbohydrate metabolism (GO: 0005975), catalytic activity (GO:0003824), zinc ion homeostasis (GO:0006829), and electron transport chain (GO:0022900). Additionally, these genes contribute to critical cellular functions, such as rRNA processing (GO:0006364), cilium- or flagellum-dependent cell motility (GO:0001539), and response to oxidative stress (GO:0006979), highlighting their potential roles in the adaptation and survival of the new lineage under varying environmental conditions and host interactions (Supplementary Figure S3).

Figure 4. Pangenome analysis of X. euvesicatoria lineages. (A) Shared gene families among three X. euvesicatoria lineage Xee, Xep and Xet. Left panel: Total number of gene families in each lineage. Right panel: intersection of gene families in each lineage. Each column represents a unique combination of lineages sharing the same gene family, as indicated by the connected dots below the x-axis. The number of gene families in each intersection set is indicated in each column. (B) Shared gene families within the Xet lineage, including the strains sequenced in this study and the NI1. This plot follows the same principle as in (A).

Homologous recombination of Xanthomonas euvesicatoria strains

To infer recombination events, we reconstructed a reference phylogeny using single-copy gene families across Xep strains. Recombination was assessed by analyzing concatenated universal genomic regions common to the compared genomes in the whole-genome alignment. CLONALFRAMEML was employed to estimate the rates of homologous recombination among the three lineages of X. euvesicatoria. The analysis revealed that within atypical Xep strains, including NI1, the rate of homologous recombination involving imported DNA was less than half the rate of mutation (R/θ < 0.5; Table 2). However, when we included other Xep strains in the comparison, the recombination rate increased, suggesting more frequent genetic exchange across these groups. Conversely, when atypical Xep strains were excluded, the remaining Xep strains exhibited a recombination rate 1.5 times higher than their mutation rate (R/θ > 1.5). Notably, the average size of the recombination fragments (δ) decreased significantly upon the inclusion of atypical and other typical Xep strains. This reduction indicated substantial recombination events between the lineages of atypical Xep strains and other typical Xep strains, possibly due to horizontal gene transfer. In all scenarios, the effect of recombination on nucleotide variation (measured as R/m) was greater than that of mutations (R/m > 1), underscoring the dominant role of recombination in the genetic diversity of X. euvesicatoria populations.

Phenotypic characteristics of Taiwanese Xep strains

Based on the gapA phylogeny, Xep strains isolated in Taiwan in 1996 formed three distinct groups. In addition to the two typical groups of Xep strains, several strains isolated in Taiwan since 1996 are phylogenetically close to the representative atypical strain NI1 from Nigeria (NZ_NISG01000001.1; Timilsina et al., 2015), suggesting a potential origin for atypical Xep strains in Taiwan. The atypical Xep strains of the new lineage were amylolytic, indicating that they can break down starch into simpler sugars through the action of amylase enzymes. This characteristic is shared by Xep, but not in the Xee (Supplementary Table S3). Additionally, these strains differed from Xee and Xep in their carbon utilization patterns (Supplementary Table S3). These phenotypic differences suggest that atypical Xep strains may represent a divergent lineage, potentially of Taiwanese origin. Together with the previous analysis, these findings further support the idea that these strains form a new lineage and do not belong to the known pathovars of X. euvesicatoria. Considering the recent progress in defining intra-species units (Rodriguez-R et al., 2024; Viver et al., 2024), we propose to consider these atypical strains as X. euvesicatoria genomovar taiwanensis (Xet, See Discussion).

Plasmid diversity and horizontal gene transfer of heavy metal resistance gene clusters

We identified eight plasmids in three typical Xep strains and 10 plasmids in four Xet strains (Supplementary Table S1). All strains carried at least one additional plasmid in addition to the CuR plasmid. In typical Xep strains, a consistent 82-kb plasmid was identified, appearing to be a fusion of a 63-kb plasmid from Xet strains and a 64-kb plasmid from X. campestris pv. campestris CFBP6943 (GenBank accession number: CP066920.1) (Dubrow et al., 2022; Table 1). Smaller plasmids of 28 kb and 10.2 kb were also identified, with the 10.2 kb plasmid being a derivative of the 28 kb plasmid (Webster et al., 2020). Notably, the plasmid pXpT2.1, derived from the CuR plasmid, lacked a 160-kb region carrying heavy metal resistance genes (Figure 5A).

Figure 5. Plasmid comparison analysis. (A) Copper resistance-related plasmid comparison. From the outermost to innermost layers: coding sequences (CDS) of pT0319-01.1 on both strands, BLAST comparison results with pT0709-01.1, pXpT2.1, and pLH3.1, followed by GC content, GC skew, and grid layers. The window size for GC content and GC skew analysis was 10 kb with a step size of 10 bp. (B) Plasmid profiles illustrating horizontal gene transfer and fusion. From the outermost to the innermost layers: CDS of pT0709-01.2 on both strands, BLAST comparison results with pT0319-01.3 and pXAC64, followed by GC content, GC skew, and grid layers. The window size for GC content and GC skew analysis was 500 bp with a step size of 1 bp. Illustration created using Prok(see Grant et al., 2023).

In Xet strains, 63-kb plasmids, similar to pXAC64 of X. citri pv. citri (GenBank: NC_003922.1) were identified (56–61% coverage and > 95% identity) (da Silva et al., 2002) (Figure 5B). Strain XTN47, isolated in 1996, carried a 97-kb plasmid, pXTN47, but lacked a 63-kb plasmid. Sequence analysis revealed that pXTN47 is a fusion of the 63-kb plasmid and a 34-kb region from the 67-kb plasmid pLMG696-1 of X. citri pv. durantae LMG696 (GenBank accession number: CP066344.1) (Rana et al., 2022), suggesting a homologous recombination-mediated plasmid fusion. Collectively, either the 63-kb plasmid or its fused derivative was present in all the sequenced strains. Additionally, the 115-kb plasmid pT0319-01.2 was highly similar to the plasmid pF of X. citri pv. phaseoli var. fuscans (GenBank: CP021016.2; 94% coverage, 99.9% identity) and pF of X. citri pv. citri DAR73910 (GenBank accession number: CP060477.1) (Webster et al., 2020) (Figure 5B). A 30-kb plasmid pXpT39.3 was similar to pXAG27 of X. citri pv. glycines (GenBank accession number: CP026335.1; 94% coverage and > 96.6% identity) (Carpenter et al., 2019).

The four CuR strains possessed a large ~250 kb plasmid containing the Cu resistance gene cluster and were absent in the CuS strains. This megaplasmid showed high nucleotide sequence identity (>99%) with CuR strains in pT4p2 of X. citri subsp. citri (Gochez et al., 2018; Huang et al., 2021) and pLH3.1 of Xep (Richard et al., 2017) (Figure 5A). Each plasmid contained a complete set of copper resistance gene clusters, including copLABGF, but lacked copCD (Huang et al., 2021). Additionally, a mercury-resistance operon (merRTPA) was flanked by an ISL3-like transposon, suggesting transposition. Unlike pT4p2, these plasmids did not contain an ~40 kb inverted repeat or arsenate resistance gene cluster.

The copper resistance plasmids also contained genes encoding heavy metal resistance ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters (cusABC and czcABC clusters) and a CadR/PbrR-like transcription regulator near a czcABC cluster. A complete Tra gene cluster encoding 16 Tra proteins essential for plasmid mobility was found in the CuR plasmids and pXpT2.1. The presence of Tra genes with high sequence similarity to other plasmids suggested that heavy metal resistance genes were likely horizontally transferred between xanthomonads.

To further test the mobility of copper resistance genes, they were transferred from CuR strain T0319-01 to CuS strain XTN47Rif through bacterial conjugation. The resulting transconjugants showed the same level of copper resistance as donor strain T0319-01. The frequency of conjugative gene transfers ranged from 10−7 to 10−5 transconjugants per recipient.

We also screened two populations of X. euvesicatoria strains collected from Taiwan at different times (Chen et al., 2024; Parajuli et al., 2024). The analysis revealed that the frequency of the copper resistance gene cluster increased in the strains collected in recent years, whereas earlier collections showed a lower frequency (Supplementary Figure S5). This indicates the recent acquisition and spread of copper resistance among X. euvesicatoria populations in Taiwan, likely driven by selective pressure from the use of copper-based bactericides.

Composition of lipopolysaccharides biosynthetic gene clusters

Lipopolysaccharides (LPSs) produced by Xee 85–10 are known to trigger basal defense responses in pepper (Keshavarzi et al., 2004). Comparative genomic analysis showed that LPS biosynthetic gene clusters, located between the conserved genes cystathionine gamma-lyase (metB) and electron transport flavoprotein subunit A (etfA), exhibited high variability among the four lineages of bacterial spot Xanthomonas. Specifically, the atypical Xep strain NI1 differed significantly from the reference strain 91–118 in both gene content and cluster number (Potnis et al., 2011; Jibrin et al., 2018; Jibrin et al., 2022). Three typical Xep strains from Taiwan had LPS biosynthetic gene clusters identical to those of Xep 91–118 (Supplementary Figure S6). Additionally, a unique LPS biosynthetic gene cluster in NI1 was consistently present in the Xet lineage (Supplementary Figure S6). These findings highlight the distinct composition of LPS biosynthetic gene clusters in the new lineage compared to typical Xep strains.

Type III secretion system and effectors recombination events

In Xanthomonas, the type III secretion system (T3SS) is essential for pathogenicity because it modulates host plant physiology and enables evasion of host immune responses (Timilsina et al., 2020). All seven sequenced strains processed conserved T3SS gene clusters encoding hrp (hypersensitive response and pathogenicity), hrc (hrp conserved), and hpa (hrp associated), indicating that T3SS is highly conserved among these strains.

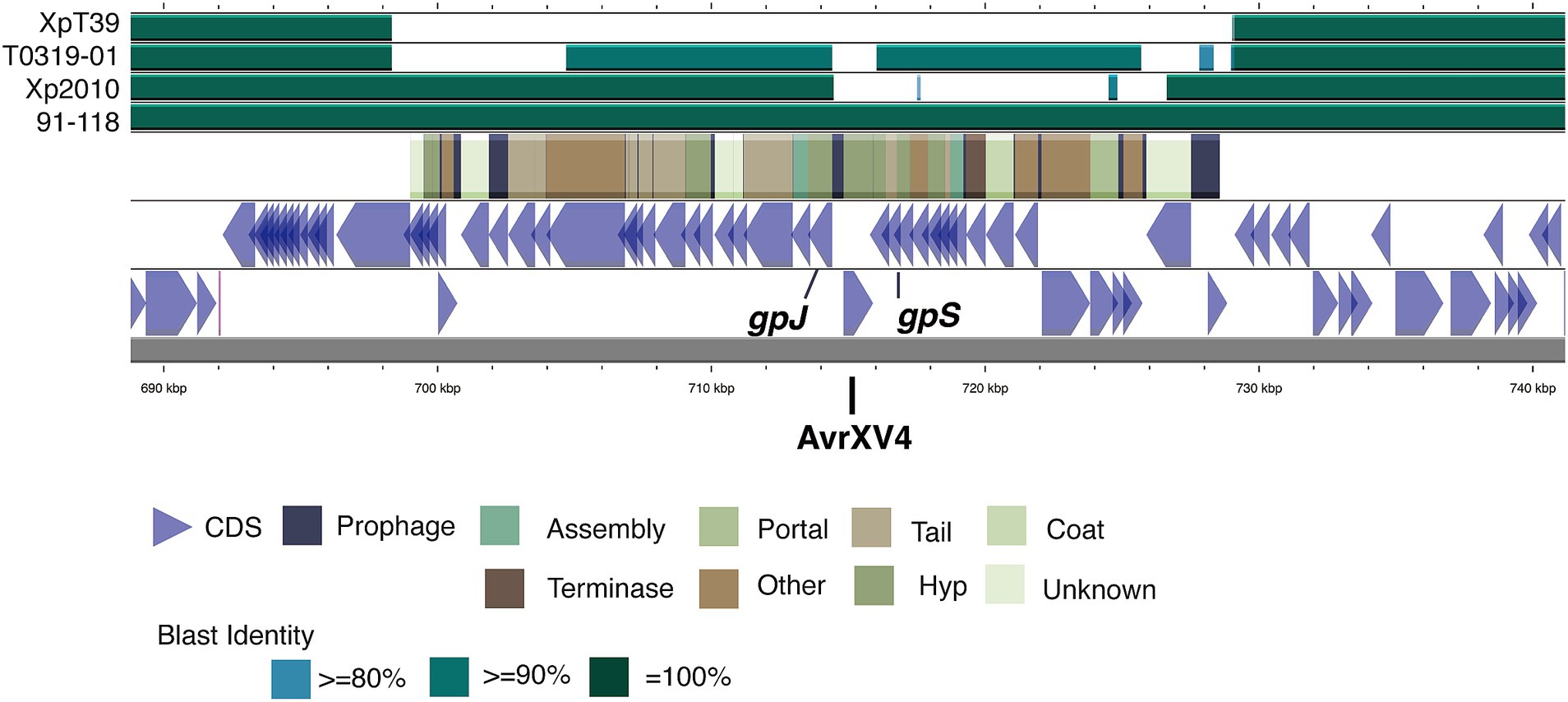

We examined the allelic diversity of three effector genes, xopAF, xopJ2a, and xopJ4, which determine the tomato races and host ranges in Xep strains (Astua-Monge et al., 2000a; Astua-Monge et al., 2000b; Timilsina et al., 2016). The three typical Xep strains contained an intact xopJ4 gene (syn. AvrXv4), which specifically determines the tomato race T4 in Xep (Astua-Monge et al., 2000b). An early stop codon was found in xopAF (syn. AvrXv3), the effector responsible for eliciting Xv3 resistance (Astua-Monge et al., 2000a), classifying these Xep strains as the tomato race T4 (Jibrin et al., 2022) (Supplementary Figure S7).

In contrast, five strains of the new lineage Xet, including the Nigerian strain NI1 (Jibrin et al., 2022), possess xopAF, but lack xopJ4. Within this lineage, two distinct xopAF alleles were observed. Strains XTN47 and NI1 have an intact xopAF gene, classifying strain XTN47 as tomato race T5, similar to NI1 (Jibrin et al., 2022). However, in the other three strains, the C-terminus of the xopAF coding sequence was truncated due to the insertion sequence ISXac4. Additionally, all seven sequenced strains and NI1 contained xopJ2b, a homolog of xopJ2a with 71% amino acid identity (Iruegas-Bocardo et al., 2018; Potnis, 2021; Jibrin et al., 2022). The xopJ2b gene was consistently present in these strains, located on the 63-kb plasmid or its derived plasmids, whereas xopJ2a was absent (Figure 6). These findings highlight conserved T3SS gene clusters but significant allelic diversity and host specificities among different X. euvesicatoria lineages.

Figure 6. Diversity of the xopAF flanking region among the different strains. The diagram illustrates the genomic structure from lower to upper sections, including coding sequences (CDS) on both strands of the T0709-01 chromosome, prophage-related genes, and BLAST comparison results with strain 91–118, Xp2010, T0319-01, and XpT39. The color coding in the BLAST results indicates sequence identity levels, with darker shades representing higher identity. The positions of the xopAF gene (syn. AvrXV3) is marked within the prophage region, highlighting the variability in this region across different strains. Illustration created using Prok(see Grant et al., 2023).

Further analysis showed that the xopJ4 gene in the three typical Xep strains was located within a P2-like temperate prophage region between the gpJ and gpS genes (Figure 6). This structure, including xopJ4, is conserved in typical Xep strains and the reference strain 91–118 (Timilsina et al., 2019) but is absent in the Xet strains. Interestingly, another P2-like prophage sharing 92% identity with the prophage carrying xopJ4 was identified in the same chromosomal region of the new lineage strains T0319-01 and XTN47, but no effector genes were found. The plasmid-borne xopJ2b gene is consistently flanked by two insertion sequence elements. These findings suggest significant recombination events and horizontal gene transfer involving type III effectors among the different X. euvesicatoria lineages.

Novel arrangement of type IV secretion gene clusters

We identified two copies of the VirB/VirD4 type IV secretion system (T4SS) cluster in typical Xep strains from Taiwan. The first one, a complete cluster with 12 genes ending with virD4, was located on the chromosome and showed high protein sequence similarity (90–100%) with the T4SS of the Xep reference strain 91–118 (Supplementary Table S4). The second cluster, consisting of nine genes lacking virB1 and virD4, was found on the 82-kb plasmids (Supplementary Table S4). These plasmid-borne T4SS genes have low protein sequence similarity with those of reference strains Xep 91–118, Xee 85–10, and X. citri subsp. citri 306. Notably, the three typical Xep strains lacked the Dot/Icm T4SS cluster (Supplementary Table S5).

In contrast, each strain of the new lineage harbored at least two distinct VirB/VirD4 T4SS clusters (Supplementary Table S4). The first T4SS cluster, a chromosomal cluster of 12 genes ending with virD4, shares 90–100% protein sequence similarity with the chromosomal T4SS in Xep, indicating strong conservation within the lineage (Supplementary Table S5). This cluster was also present on the NI1 chromosome, further distinguishing this new lineage from typical Xep strains. Additionally, a second VirB/VirD4 T4SS cluster, lacking virD4 and consistsing of 10 genes, was consistently found on the 63-kb plasmids and the 97-kb plasmid pXTN47, which includes the 63-kb plasmid backbone. This plasmid-borne cluster shares high protein sequence similarity with the T4SS genes of Xee 85–10 but differs from those in Xep 91–118, particularly in the VirB4, VirB5, and VirB6 proteins (Supplementary Table S4).

Interestingly, the plasmid-borne T4SS genes in the new lineage were distinct from those in the Xep strains in both gene composition and sequence. Proteins such as VirB1, VirB4, VirB6, VirB9, VirB10, and VirB11 showed greater similarity to those in X. citri subsp. citri 306 than to those in Xee 85–10, suggesting a distinct evolutionary pathway (Supplementary Table S4). The third T4SS cluster, found in the plasmids of strains XTN47 and T0319-01, originated from the pLMG696-1 plasmid of X. citri pv. durantae LMG696, further emphasizing the diversity of T4SS clusters in these strains. These findings highlight the diversity and complexity of T4SS clusters among different Xep strains and the new lineage, suggesting their potential role in pathogenicity and host interactions.

Discussion

Our study provides crucial insights into the taxonomy and phylogenetic relationships within the bacterial spot of X. euvesicatoria pathovars by leveraging high-quality, complete genome strains in Taiwan. The availability of circularized chromosomes and plasmids for three typical and four atypical strains enabled detailed comparative genomic analyses, enhancing our understanding of the bacterial identification, evolution, and pathogenicity of bacterial spot xanthomonads. Completely circularized genomes offer a more comprehensive view of dynamic variations at the inter-strain level (Gochez et al., 2018; Kaur et al., 2019; Huang et al., 2021) than draft genome assemblies or resequencing studies (Zhang et al., 2015; Bansal et al., 2018; Patané et al., 2019; Timilsina et al., 2019; Chen et al., 2024; Parajuli et al., 2024). Additionally, the phylogenetic classification of Xanthomonas species can be challenging owing to genetic cohesion within the genus and the absence of high-quality genomic resources for certain lineages. For example, Agarwal et al. (2023) reanalyzed 1,910 diverse Xanthomonas genomes, leading to the reclassification of 288 previously misclassified strains.

Our analyses revealed that the atypical strains collected in Taiwan and NI1 formed a distinct genetic lineage within X. euvesicatoria separated from the known pathovars X. euvesicatoria pv. euvesicatoria (Xee) and X. euvesicatoria pv. perforans (Xep) (Figure 2). The average nucleotide identity (ANI) scores among these atypical strains were > 99.8%, indicating that they belong to the same intra-species unit. Importantly, the ANI scores between the atypical strains and Xep or Xee ranged from 98.5 to 98.8%, suggesting significant genomic divergence. In X. euvesicatoria phylogenetic analysis, an ANI threshold of >98.5% is commonly used to differentiate Xep isolated from Xee (Barak et al., 2016; Constantin et al., 2016; Bansal et al., 2018; Jibrin et al., 2018; Fan et al., 2022). This observation aligns with the concept of the ´ANI gap´, which refers to a discontinuity in ANI values that helps define intra-species units (Rodriguez-R et al., 2024; Viver et al., 2024). Strains with ANI values above 99.2–99.8% (midpoint 99.5%) can be considered to belong to the same genomovar within a species (Rodriguez-R et al., 2024; Viver et al., 2024). The ANI gap observed between atypical strains and known pathovars supports the designation of a new genomovar.

In plant pathogenic bacteria, ′pathovar′ traditionally describes strains below the subspecies level that differ in pathogenicity based on symptom type or host range. Our data, along with previous studies, indicate that the two known pathovars and the newly identified phylogenetic lineage within the X. euvesicatoria complex share highly similar plant host ranges and disease symptoms, particularly in causing bacterial spot disease in tomatoes and peppers (Timilsina et al., 2020). Given the limited phenotypic differences and host range among these three phylogenetic lineages (Bradbury, 1983; Parker et al., 2019; Timilsina et al., 2020), we propose that the term ′genomovar′ is more appropriate than ′pathovar′ for naming these lineages within X. euvesicatoria. We recommend using the term ′genomovar′ to designate the three phylogenetic lineages of X. euvesicatoria as X. euvesicatoria genomovar euvesicatoria (Xee), genomovar perforans (Xep), and genomovar taiwanensis (Xet) with strain T0319-01 as the representative Xet. This approach reflects the genetic distinctions among lineages, while acknowledging their similar pathogenic characteristics.

Our data also suggest that the novel genomovar taiwanensis of X. euvesicatoria likely originated from Taiwan. The earliest identified strain of Xet, XTN47, was isolated in 1996, predating the first reported identification of Xep strains in tomatoes in 2010 (Leu et al., 2010). It is plausible that the Xet strains were subsequently introduced into Nigeria through the global trade of tomato seeds, leading to their presence in that region.

Plasmids as the recombination vehicle to faciliate the transfer of virulence/avirulence factors or heavy metal resistance genes

Plasmids in Xanthomonas species that cause bacterial leaf spot in tomato and pepper vary widely in size and often carry virulence or heavy metal resistance genes (Minsavage et al., 1990; Thieme et al., 2005; Roach et al., 2019; Huang et al., 2021). Unfortunately, detailed information regarding plasmids from bacterial spot Xanthomonas, particularly Xep, remains limited (Potnis et al., 2011; Roach et al., 2019; Chen et al., 2024; Parajuli et al., 2024). In this study, we found that the 63-kb plasmid in the Xet lineage resembles the pathogenicity plasmid pXAC64 of X. citri subsp. citri (da Silva et al., 2002). The 82-kb plasmid in three typical Xep strains likely originated from a recombination event, leading to plasmid cointegration, a phenomenon also observed in X. citri subsp. citri strains in Taiwan (Huang et al., 2021).

The copLABGF cluster associated with heavy metal resistance and the Tra cluster for plasmid mobility are located on an approximately 250-kb megaplasmid. Previous conjugative transfer experiments confirmed the mobility of this plasmid, enabling the horizontal transfer of copper resistance genes between Xet strains (Basim et al., 2005; Behlau et al., 2012). Additionally, the presences of the mercury resistance gene cluster (merRTPA) instead of the arsenate resistance gene cluster (Huang et al., 2021), suggests transposition events mediated by insertion elements. These findings indicate significant variation in plasmid distribution among X. euvesicatoria strains depending on their geographical origin and host, highlighting the diversity and evolutionary significance of plasmid profiles in Xanthomonas (Burlakoti et al., 2018; Lai et al., 2021; Xu et al., 2023).

Evolution of type III effectors

Recombination and other mechanisms likely contribute to the gain and loss of type III secretion system (T3SS) effector genes in Xanthomonas. The xopJ4 gene is carried by a P2-like temperate prophage in the Xep genomes, reflecting lysogenic conversion (Harrison and Brockhurst, 2017), which facilitates the horizontal transfer of virulence factors and enhances the fitness of pathogenic bacteria. This process has been observed in both animal pathogens (Harrison and Brockhurst, 2017) and the phytopathogen Ralstonia solanacearum (Askora et al., 2017), suggesting its role in the evolution of Xep races.

In contrast, the xopJ2b gene is consistently flanked by two insertion sequence elements and is located on a virulence-related plasmid. Insertion sequence-mediated transposition may be associated with the gain and loss of xopJ2a or xopJ2b in the Xep strains (Klein-Gordon et al., 2021). The XopJ family of type III effectors, which includes XopJ1, XopJ2a (syn. AvrBsT), XopJ3 (syn. AvrRxv), and XopJ2b (syn. XopJ6 homolog) has been identified in Xee and Xep (Minsavage et al., 1990; Ma and Ma, 2016; Iruegas-Bocardo et al., 2018; Osdaghi et al., 2021; Potnis, 2021) and plays a role in enhancing bacterial fitness and determining the host range (Timilsina et al., 2016; Osdaghi et al., 2021; Potnis, 2021). XopJ2a can trigger a hypersensitive response (HR) in pepper, limiting the host range of Xep to tomato and enhancing Xep fitness in tomato plants (Minsavage et al., 1990; Timilsina et al., 2016; Abrahamian et al., 2018). XopJ2b also induces HR in peppers (Iruegas-Bocardo et al., 2018), although its role is not well understood (Sharma et al., 2024).

Since all strains sequenced in this study carried the 63-kb plasmid or its derivatives housing the xopJ2b gene, we propose that these plasmids may contribute to the virulence and fitness of the Xep and Xet strains. Further research is needed to clarify the distribution and roles of xopJ2b and these plasmids in X. euvesicatoria genomovars (Sharma et al., 2024).

Recombination of type IV secretion system

The VirB/VirD4 type IV secretion system (T4SS) clusters are widely distributed among xanthomonads responsible for diseases such as bacterial spot in tomato and pepper, citrus canker, and rice bacterial blight (da Silva et al., 2002; Thieme et al., 2005; Potnis et al., 2011; Kaur et al., 2019; Jibrin et al., 2022). Our characterization of these clusters revealed that the new genomovar Xet differed significantly from Xee 85–10 and Xep 91–118. Protein sequence comparisons suggested that the chromosomal T4SS cluster of Xet is a hybrid cluster that combines elements from the T4SS clusters of Xep and X. citri subsp. citri.

Interestingly, the Taiwanese strains studied here exhibit substantial variation in their plasmid-borne VirB/VirD4 T4SS proteins compared to each other and Xep 91–118, suggesting that they carry a novel VirB/VirD4 T4SS in their plasmids. Furthermore, the plasmid-borne T4SS cluster in Xet may have evolved through recombination between the clusters found in the plasmids of Xee and X. citri subsp. citri. Notably, the hybrid plasmid pXTN47 of strain XTN47 harbors two VirB/VirD4 T4SS clusters: one identical to the T4SS cluster of Xet strains and the other identical to that in pLMG696-1 of X. citri pv. durantae LMG696. These findings suggest that plasmids carrying distinct T4SSs may play a critical role in the evolution and adaptation of plant-pathogenic xanthomonads (Rana et al., 2022).

Additionally, strain T0319-01 was the only strain found to carry the Dot/Icm T4SS cluster within the 112-kb plasmid p0319-01.2, which shows high similarity to the plasmid pF of X. citri but differs markedly from pXCV182 of Xee 85–10. This suggested that X. euvesicatoria strains may acquire plasmids carrying the Dot/Icm T4SS cluster from various donors via horizontal gene transfer or other unknown mechanisms (Drehkopf et al., 2023).

Conclusion

In this study, we performed complete genome sequencing of seven strains of X. euvesicatoria genomovars perforans (Xep) and taiwanensis (Xet) and the compared them to multiple Xanthomonas genomes. This provides evidence of significant diversity and plasticity in both chromosomes and plasmids. These results suggest that the genomovar taiwanensis may have originated in Taiwan and subsequently spread to Nigeria through global seed trades. Genomic analysis revealed genetic recombination, evolution of virulence and avirulence factors, and horizontal gene transfer events within the strains of these two genomovars. The gap-free genomes revealed associations between the evolution of type III and type IV effectors and horizontal gene transfer. They also highlighted the role of plasmid diversity and recombination in the genetic landscape of the sequenced strains. Notably, we identified the cop gene cluster and mercury resistance gene cluster, but not the arsenate resistance gene cluster, on the megaplasmid of the CuR strain of X. euvesicatoria. Collectively, these findings suggest that horizontal gene transfer and genetic recombination have significantly shaped the genetic makeup of X. euvesicatoria genomovars, contributing to their adaptation and survival within the agroecosystem.

Data availability statement

All sequencing data and genome assemblies were deposited in the NCBI database under BioProject ID PRJNA1029321. The X. euvesicatoria strains that support the findings of this study are available upon request from CJH. T0319-01T is available in Bioresource Collection and Research Center under ID BCRC 81416 (https://catalog.bcrc.firdi.org.tw/BcrcContent?bid=81416&rowid=1).

Author contributions

C-JH: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. T-LW: Writing – original draft, Software, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation. Y-LW: Resources, Methodology, Writing – original draft. R-SW: Writing – original draft, Resources, Methodology. Y-CL: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST, grant nos. 110-2313-B-415-007, 111-2313-B-415-002, and 112-2313-B-415-006) to C-JH; and the Innovative Translational Agricultural Research Program (AS-KPQ-110-ITAR-03, AS-KPQ-111-ITAR-11107, AS-ITAR-111-L11102), Agricultural Biotechnology for Sustainability (AS-KPQ-111-ITAR-11207 and AS-ITAR-113030), and Academia Sinica Institutional funding to Y-CL. These funding bodies played no role in the design of the study, collection, analysis or interpretation of data, or in writing the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank AS-BCST Bioinformatics Core for their computational support. We are grateful to all members of the Bioinformatics and Computational Genomics Laboratory for the insightful discussion of the project. Strain XTN47 was kindly provided by Yea-Fang Wu at the Crop Environment Section, Tainan District Agricultural Research and Extension Station. Generative AI (ChatGPT (model o1-preview)) was used in the writing process to improve readability and language of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2024.1487917/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^EPPO Global database, 2023 https://gd.eppo.int/taxon/XANTPF/datasheet

References

Abrahamian, P., Klein-Gordon, J. M., Jones, J. B., and Vallad, G. E. (2021). Epidemiology, diversity, and management of bacterial spot of tomato caused by Xanthomonas perforans. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 105, 6143–6158. doi: 10.1007/s00253-021-11459-9

Abrahamian, P., Timilsina, S., Minsavage, G. V., Kc, S., Goss, E. M., Jones, J. B., et al. (2018). The type III effector AvrBsT enhances Xanthomonas perforans fitness in field-grown tomato. Phytopathology 108, 1355–1362. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-02-18-0052-R

Agarwal, V., Stubits, R., Nassrullah, Z., and Dillon, M. M. (2023). Pangenomic insights into the diversification and disease specificity of worldwide Xanthomonas outbreaks. Front. Microbiol. 14:1213261. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1213261

Andrews, S., Krueger, F., Segonds-Pichon, A., Biggins, L., Krueger, C., and Wingett, S. (2023). FastQC: a quality control tool for high throughput sequence data. Available at: https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/.

Askora, A., Kawasaki, T., Fujie, M., and Yamada, T. (2017). Lysogenic conversion of the phytopathogen Ralstonia solanacearum by the P2virus ϕRSY1. Front. Microbiol. 8:2212. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02212

Astua-Monge, G., Minsavage, G. V., Stall, R. E., Davis, M. J., Bonas, U., and Jones, J. B. (2000a). Resistance of tomato and pepper to T3 strains of Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria is specified by a plant-inducible avirulence. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 13, 911–921. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2000.13.9.911

Astua-Monge, G., Minsavage, G. V., Stall, R. E., Vallejos, C. E., Davis, M. J., and Jones, J. B. (2000b). Xv4-vrxv4: a new gene-for-gene interaction identified between Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria race T3 and the wild tomato relative Lycopersicon pennellii. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 13, 1346–1355. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2000.13.12.1346

Bansal, K., Kumar, S., and Patil, P. B. (2018). Complete genome sequence reveals evolutionary dynamics of an emerging and variant Pathovar of Xanthomonas euvesicatoria. Genome Biol. Evol. 10, 3104–3109. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evy238

Barak, J. D., Vancheva, T., Lefeuvre, P., Jones, J. B., Timilsina, S., Minsavage, G. V., et al. (2016). Whole-genome sequences of Xanthomonas euvesicatoria strains clarify taxonomy and reveal a stepwise Erosion of type 3 effectors. Front. Plant Sci. 7:1805. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01805

Basim, H., Minsavage, G. V., Stall, R. E., Wang, J. F., Shanker, S., and Jones, J. B. (2005). Characterization of a unique chromosomal copper resistance gene cluster from Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71, 8284–8291. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.12.8284-8291.2005

Behlau, F., Canteros, B. I., Jones, J. B., and Graham, J. H. (2012). Copper resistance genes from different xanthomonads and citrus epiphytic bacteria confer resistance to subsp. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 133, 949–963. doi: 10.1007/s10658-012-9966-8

Behlau, F., Hong, J. C., Jones, J. B., and Graham, J. H. (2013). Evidence for acquisition of copper resistance genes from different sources in citrus-associated xanthomonads. Phytopathology 103, 409–418. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-06-12-0134-R

Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M., and Usadel, B. (2014). Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170

Bradbury, J. F. (1983). The new bacterial nomenclature - what to do. Phytopathology 73, 1349–1350. doi: 10.1094/Phyto-73-1349

Burlakoti, R. R., Hsu, C. F., Chen, J. R., and Wang, J. F. (2018). Population dynamics of Xanthomonads associated with bacterial spot of tomato and pepper during 27 years across Taiwan. Plant Dis. 102, 1348–1356. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-04-17-0465-RE

Camacho, C., Coulouris, G., Avagyan, V., Ma, N., Papadopoulos, J., Bealer, K., et al. (2009). BLAST plus: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics 10:421. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-421

Capella-Gutiérrez, S., Silla-Martínez, J. M., and Gabaldón, T. (2009). trimAl: a tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics 25, 1972–1973. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp348

Carpenter, S. C. D., Kladsuwan, L., Han, S. W., Prathuangwong, S., and Bogdanove, A. J. (2019). Complete genome sequences of Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. glycines isolates from the United States and Thailand reveal conserved transcription activator-like effectors. Genome Biol. Evol. 11, 1380–1384. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evz085

Carver, T., Harris, S. R., Berriman, M., Parkhill, J., and Mcquillan, J. A. (2012). Artemis: an integrated platform for visualization and analysis of high-throughput sequence-based experimental data. Bioinformatics 28, 464–469. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr703

Chen, J. R., Aguirre-Carvajal, K., Xue, D. Y., Chang, H. C., Arone-Maxwell, L., Lin, Y. P., et al. (2024). Exploring the genetic makeup of Xanthomonas species causing bacterial spot in Taiwan: evidence of population shift and local adaptation. Front. Microbiol. 15:1408885. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2024.1408885

Chun, J., Oren, A., Ventosa, A., Christensen, H., Arahal, D. R., Da Costa, M. S., et al. (2018). Proposed minimal standards for the use of genome data for the taxonomy of prokaryotes. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 68, 461–466. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.002516

Constantin, E. C., Cleenwerck, I., Maes, M., Baeyen, S., Van Malderghem, C., De Vos, P., et al. (2016). Genetic characterization of strains named as pv. Leads to a taxonomic revision of the species complex. Plant Pathol. 65, 792–806. doi: 10.1111/ppa.12461

Coudert, E., Gehant, S., De Castro, E., Pozzato, M., Baratin, D., Neto, T., et al. (2023). Annotation of biologically relevant ligands in UniProtKB using ChEBI. Bioinformatics 39:793. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btac793

Da Silva, A. C. R., Ferro, J. A., Reinach, F. C., Farah, C. S., Furlan, L. R., Quaggio, R. B., et al. (2002). Comparison of the genomes of two Xanthomonas pathogens with differing host specificities. Nature 417, 459–463. doi: 10.1038/417459a

de Coster, W., D’Hert, S., Schultz, D. T., Cruts, M., and van Broeckhoven, C. (2018). NanoPack: visualizing and processing long-read sequencing data. Bioinformatics 34, 2666–2669. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty149

Didelot, X., and Wilson, D. J. (2015). ClonalFrameML: efficient inference of recombination in whole bacterial genomes. PLoS Comput. Biol. 11:e1004041. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004041

Drehkopf, S., Scheibner, F., and Buttner, D. (2023). Functional characterization of VirB/VirD4 and Icm/dot type IV secretion systems from the plant-pathogenic bacterium Xanthomonas euvesicatoria. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 13:1203159. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2023.1203159

Dubrow, Z. E., Carpenter, S. C. D., Carter, M. E., Grinage, A., Gris, C., Lauber, E., et al. (2022). Cruciferous weed isolates of Xanthomonas campestris yield insight into Pathovar genomic relationships and genetic determinants of host and tissue specificity. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 35, 791–802. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-01-22-0024-R

Edgar, R. C. (2004). MUSCLE: a multiple sequence alignment method with reduced time and space complexity. BMC Bioinformatics 5:113. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-5-113

Enright, A. J., Van Dongen, S., and Ouzounis, C. A. (2002). An efficient algorithm for large-scale detection of protein families. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 1575–1584. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.7.1575

Fan, Q., Bibi, S., Vallad, G. E., Goss, E. M., Hurlbert, J. C., Paret, M. L., et al. (2022). Identification of genes in Xanthomonas euvesicatoria pv. rosa that are host limiting in tomato. Plants (Basel) 11:796. doi: 10.3390/plants11060796

Gochez, A. M., Huguet-Tapia, J. C., Minsavage, G. V., Shantaraj, D., Jalan, N., Strauss, A., et al. (2018). Pacbio sequencing of copper-tolerant Xanthomonas citri reveals presence of a chimeric plasmid structure and provides insights into reassortment and shuffling of transcription activator-like effectors among X. citri strains. BMC Genomics 19:16. doi: 10.1186/s12864-017-4408-9

Gotz, S., Garcia-Gomez, J. M., Terol, J., Williams, T. D., Nagaraj, S. H., Nueda, M. J., et al. (2008). High-throughput functional annotation and data mining with the Blast2GO suite. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, 3420–3435. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn176

Grant, J. R., Enns, E., Marinier, E., Mandal, A., Herman, E. K., Chen, C. Y., et al. (2023). Proksee: in-depth characterization and visualization of bacterial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, W484–W492. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkad326

Harrison, E., and Brockhurst, M. A. (2017). Ecological and evolutionary benefits of temperate phage: what does or Doesn't kill you makes you stronger. BioEssays 39:1700772. doi: 10.1002/bies.201700112

Hickey, G., Monlong, J., Ebler, J., Novak, A. M., Eizenga, J. M., Gao, Y., et al. (2024). Pangenome graph construction from genome alignments with Minigraph-Cactus. Nat. Biotechnol. 42, 663–673. doi: 10.1038/s41587-023-01793-w

Huang, C. J., Wu, T. L., Zheng, P. X., Ou, J. Y., Ni, H. F., and Lin, Y. C. (2021). Comparative genomic analysis uncovered evolution of pathogenicity factors, horizontal gene transfer events, and heavy metal resistance traits in Citrus canker bacterium Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri. Front. Microbiol. 12:731711. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.731711

Iruegas-Bocardo, F., Abrahamian, P., Minsavage, G. V., Potnis, N., Vallad, G. E., Jones, J. B., et al. (2018). XopJ6, a new member of the XopJ family of type III effectors, in Xanthomonas perforans. Phytopathology 108:37.

Jain, C., Rodriguez, R. L., Phillippy, A. M., Konstantinidis, K. T., and Aluru, S. (2018). High throughput ANI analysis of 90K prokaryotic genomes reveals clear species boundaries. Nat. Commun. 9:5114. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07641-9

Jibrin, M. O., Potnis, N., Timilsina, S., Minsavage, G. V., Vallad, G. E., Roberts, P. D., et al. (2018). Genomic inference of recombination-mediated evolution in Xanthomonas euvesicatoria and X. perforans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 84, e00136–e00118. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00136-18

Jibrin, M. O., Timilsina, S., Minsavage, G. V., Vallad, G. E., Roberts, P. D., Goss, E. M., et al. (2022). Bacterial spot of tomato and pepper in Africa: diversity, emergence of T5 race, and management. Front. Microbiol. 13:835647. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.835647

Jibrin, M. O., Timilsina, S., Potnis, N., Minsavage, G. V., Shenge, K. C., Akpa, A. D., et al. (2015). First report of atypical Xanthomonas euvesicatoria strains causing bacterial spot of tomato in Nigeria. Plant Dis. 99:415. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-09-14-0952-PDN

Jones, P., Binns, D., Chang, H. Y., Fraser, M., Li, W., Mcanulla, C., et al. (2014). InterProScan 5: genome-scale protein function classification. Bioinformatics 30, 1236–1240. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu031

Jones, J. B., Lacy, G. H., Bouzar, H., Stall, R. E., and Schaad, N. W. (2004). Reclassification of the xanthomonads associated with bacterial spot disease of tomato and pepper. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 27, 755–762. doi: 10.1078/0723202042369884

Kaur, A., Bansal, K., Kumar, S., Sonti, R. V., and Patil, P. B. (2019). Complete genome dynamics of a dominant-lineage strain of Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae harbouring a novel plasmid encoding a type IV secretion system. Access Microbiol. 1:e000063. doi: 10.1099/acmi.0.000063

Keshavarzi, M., Soylu, S., Brown, I., Bonas, U., Nicole, M., Rossiter, J., et al. (2004). Basal defenses induced in pepper by lipopolysaccharides are suppressed by Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 17, 805–815. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2004.17.7.805

Klein-Gordon, J. M., Xing, Y., Garrett, K. A., Abrahamian, P., Paret, M. L., Minsavage, G. V., et al. (2021). Assessing Changes and Associations in the Xanthomonas perforans Population Across Florida Commercial Tomato Fields Via a Statewide Survey. Phytopathology 111, 1029–1041. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-09-20-0402-R

Kolmogorov, M., Yuan, J., Lin, Y., and Pevzner, P. A. (2019). Assembly of long, error-prone reads using repeat graphs. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 540–546. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0072-8

Koren, S., Walenz, B. P., Berlin, K., Miller, J. R., Bergman, N. H., and Phillippy, A. M. (2017). Canu: scalable and accurate long-read assembly via adaptivek-mer weighting and repeat separation. Genome Res. 27, 722–736. doi: 10.1101/gr.215087.116

Kozlov, A. M., Darriba, D., Flouri, T., Morel, B., and Stamatakis, A. (2019). RAxML-NG: a fast, scalable and user-friendly tool for maximum likelihood phylogenetic inference. Bioinformatics 35, 4453–4455. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz305

Lai, Y. R., Lin, C. H., Chang, C. P., Ni, H. F., Tsai, W. S., and Huang, C. J. (2021). Distribution of copper resistance gene variants of Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri and Xanthomonas euvesicatoria pv. perforans. Plant Prot. Sci. 57, 206–216. doi: 10.17221/160/2020-PPS

Leu, Y. S., Deng, W.-L., Wu, Y. F., Cheng, A. S., Hsu, S. T., and Tzeng, K. C. (2010). Characterization of Xanthomonas associated with bacterial spot of tomato and pepper in Taiwan. Plant Pathol. Bull. 19, 181–190.

Ma, K. W., and Ma, W. B. (2016). YopJ family effectors promote bacterial infection through a unique acetyltransferase activity. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 80, 1011–1027. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00032-16

Manni, M., Berkeley, M. R., Seppey, M., Simao, F. A., and Zdobnov, E. M. (2021). BUSCO update: novel and streamlined workflows along with broader and deeper phylogenetic coverage for scoring of eukaryotic, prokaryotic, and viral genomes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 38, 4647–4654. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msab199

Marin, T. G. S., Galvanin, A. L., Lanza, F. E., and Behlau, F. (2019). Description of copper tolerant subsp. and genotypic comparison with sensitive and resistant strains. Plant Pathol. 68, 1088–1098. doi: 10.1111/ppa.13026

Meier-Kolthoff, J. P., Carbasse, J. S., Peinado-Olarte, R. L., and Göker, M. (2022). TYGS and LPSN: a database tandem for fast and reliable genome-based classification and nomenclature of prokaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res. 50, D801–D807. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab902

Méric, G., Yahara, K., Mageiros, L., Pascoe, B., Maiden, M. C. J., Jolley, K. A., et al. (2014). A reference Pan-genome approach to comparative bacterial genomics: identification of novel epidemiological markers in pathogenic Campylobacter. PLoS One 9:e92798. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092798

Minsavage, G. V., Dahlbeck, D., Whalen, M. C., Kearney, B., Bonas, U., Staskawicz, B. J., et al. (1990). Gene-for-gene relationships specifying disease resistance in Xanthomonas-campestris Pv vesicatoria - pepper interactions. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 3, 41–47. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-3-041

Newberry, E. A., Bhandari, R., Minsavage, G. V., Timilsina, S., Jibrin, M. O., Kemble, J., et al. (2019). Independent evolution with the gene flux originating from multiple Xanthomonas species explains genomic heterogeneity in Xanthomonas perforans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 85, e00885–e00819. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00885-19

Osdaghi, E., Jones, J. B., Sharma, A., Goss, E. M., Abrahamian, P., Newberry, E. A., et al. (2021). A certury for bacterial spot of tomato and pepper. Mol. Plant Pathol. 22, 1500–1519. doi: 10.1111/mpp.13125

Parajuli, A., Subedi, A., Timilsina, S., Minsavage, G. V., Kenyon, L., Chen, J. R., et al. (2024). Phenotypic and genetic diversity of xanthomonads isolated from pepper (Capsicum spp.) in Taiwan from 1989 to 2019. Phytopathology 114, 2033–2044. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-11-23-0449-R

Parker, C. T., Tindall, B. J., and Garrity, G. M. (2019). International code of nomenclature of prokaryotes prokaryotic code (2008 revision). Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 69, S7–S111. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.000778

Parks, D. H., Imelfort, M., Skennerton, C. T., Hugenholtz, P., and Tyson, G. W. (2015). CheckM: assessing the quality of microbial genomes recovered from isolates, single cells, and metagenomes. Genome Res. 25, 1043–1055. doi: 10.1101/gr.186072.114

Patané, J. S. L., Martins, J. Jr., Rangel, L. T., Belasque, J., Digiampietri, L. A., Facincani, A. P., et al. (2019). Origin and diversification of Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri pathotypes revealed by inclusive phylogenomic, dating, and biogeographic analysis. BMC Genomics 20:700. doi: 10.1186/s12864-019-6007-4

Pohronezny, K., and Volin, R. B. (1983). The effect of bacterial spot on yield and quality of fresh market Tomatoes1. HortScience 18, 69–70. doi: 10.21273/HORTSCI.18.1.69

Potnis, N. (2021). Harnessing eco-evolutionary dynamics of Xanthomonads on tomato and pepper to tackle new problems of an old disease. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 59, 289–310. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-020620-101612

Potnis, N., Krasileva, K., Chow, V., Almeida, N. F., Patil, P. B., Ryan, R. P., et al. (2011). Comparative genomics reveals diversity among xanthomonads infecting tomato and pepper. BMC Genomics 12:146. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-146

Proost, S., Fostier, J., De Witte, D., Dhoedt, B., Demeester, P., Van De Peer, Y., et al. (2012). I-ADHoRe 3.0-fast and sensitive detection of genomic homology in extremely large data sets. Nucleic Acids Res. 40:e11. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr955

Qian, W., Jia, Y., Ren, S. X., He, Y. Q., Feng, J. X., Lu, L. F., et al. (2005). Comparative and functional genomic analyses of the pathogenicity of phytopathogen Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris. Genome Res. 15, 757–767. doi: 10.1101/gr.3378705

Rana, R., Bansal, K., Kaur, A., and Patil, P. B. (2022). Genome dynamics mediated by repetitive and mobile elements in Xanthomonas citri pv. durantae. Access Microbiol. 4:acmi000415. doi: 10.1099/acmi.0.000415

Richard, D., Ravigne, V., Rieux, A., Facon, B., Boyer, C., Boyer, K., et al. (2017). Adaptation of genetically monomorphic bacteria: evolution of copper resistance through multiple horizontal gene transfers of complex and versatile mobile genetic elements. Mol. Ecol. 26, 2131–2149. doi: 10.1111/mec.14007

Roach, R., Mann, R., Gambley, C. G., Chapman, T., Shivas, R. G., and Rodoni, B. (2019). Genomic sequence analysis reveals diversity of Australian Xanthomonas species associated with bacterial leaf spot of tomato, capsicum and cilli. BMC Genomics 20:310. doi: 10.1186/s12864-019-5600-x

Rodriguez-R, L. M., Conrad, R. E., Viver, T., Feistel, D. J., Lindner, B. G., Venter, S. N., et al. (2024). An ANI gap within bacterial species that advances the definitions of intra-species units. mBio 15:e0269623. doi: 10.1128/mbio.02696-23

Ruan, J., and Li, H. (2020). Fast and accurate long-read assembly with wtdbg2. Nat. Methods 17, 155–158. doi: 10.1038/s41592-019-0669-3

Schwartz, A. R., Potnis, N., Timilsina, S., Wilson, M., Patane, J., Martins, J. Jr., et al. (2015). Phylogenomics of Xanthomonas field strains infecting pepper and tomato reveals diversity in effector repertoires and identifies determinants of host specificity. Front. Microbiol. 6:535. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00535

Sharma, A., Iruegas-Bocardo, F., Bibi, S., Chen, Y. C., Kim, J. G., Abrahamian, P., et al. (2024). Multiple acquisitions of XopJ2 effectors in populations of Xanthomonas perforans. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2024:8. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-05-24-0048-R

Stall, R. E., Beaulieu, C., Egel, D., Hodge, N. C., Leite, R. P., Minsavage, G. V., et al. (1994). Two genetically diverse groups of strains are included in Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 44, 47–53. doi: 10.1099/00207713-44-1-47

Tatusova, T., Dicuccio, M., Badretdin, A., Chetvernin, V., Nawrocki, E. P., Zaslavsky, L., et al. (2016). NCBI prokaryotic genome annotation pipeline. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, 6614–6624. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw569

Thieme, F., Koebnik, R., Bekel, T., Berger, C., Boch, J., Büttner, D., et al. (2005). Insights into genome plasticity and pathogenicity of the plant pathogenic bacterium pv. vesicatoria revealed by the complete genome sequence. J. Bacteriol. 187, 7254–7266. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.21.7254-7266.2005

Timilsina, S., Abrahamian, P., Potnis, N., Minsavage, G. V., White, F. F., Staskawicz, B. J., et al. (2016). Analysis of sequenced genomes of Xanthomonas perforans identifies candidate targets for resistance breeding in tomato. Phytopathology 106, 1097–1104. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-03-16-0119-FI

Timilsina, S., Jibrin, M. O., Potnis, N., Minsavage, G. V., Kebede, M., Schwartz, A., et al. (2015). Multilocus sequence analysis of Xanthomonads causing bacterial spot of tomato and pepper plants reveals strains generated by recombination among species and recent global spread of. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 81, 1520–1529. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03000-14

Timilsina, S., Pereira-Martin, J. A., Minsavage, G. V., Iruegas-Bocardo, F., Abrahamian, P., Potnis, N., et al. (2019). Multiple recombination events drive the current genetic structure of Xanthomonas perforans in Florida. Front. Microbiol. 10:448. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00448

Timilsina, S., Potnis, N., Newberry, E. A., Liyanapathiranage, P., Iruegas-Bocardo, F., White, F. F., et al. (2020). Xanthomonas diversity, virulence and plant-pathogen interactions. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 18, 415–427. doi: 10.1038/s41579-020-0361-8

Viver, T., Conrad, R. E., Rodriguez, R. L., Ramirez, A. S., Venter, S. N., Rocha-Cardenas, J., et al. (2024). Towards estimating the number of strains that make up a natural bacterial population. Nat. Commun. 15:544. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-44622-z

Wang, J. R., Holt, J., Mcmillan, L., and Jones, C. D. (2018). FMLRC: hybrid long read error correction using an FM-index. BMC Bioinformatics 19:50. doi: 10.1186/s12859-018-2051-3