- 1Department of Agricultural Microbiology, Faculty of Agriculture, Benha University, Benha, Egypt

- 2Department of Basic and Applied Agricultural Sciences, Higher Institute for Agriculture Cooperation, Cairo, Egypt

- 3Botany and Microbiology Department, Faculty of Science, Al-Azhar University, Cairo, Egypt

- 4Department of Botany and Microbiology, College of Science, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

- 5Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Division of Pharmacology and Toxicology, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria

- 6Department of Botany and Microbiology, Faculty of Science, Benha University, Benha, Egypt

Fungal endophytes are known to produce bioactive chemicals and secondary metabolites that are often identical to those produced by their host plants. The main objective of the current study was to isolate and identify endophytic fungi associated with the medicinal plant Anethum graveolens, and to investigate their potential antibacterial and anticancer properties. The ethyl acetate extracts from the isolated endophytic fungi, as well as the host plant A. graveolens, were subjected to bioactivity assays to evaluate their antibacterial and anticancer potential against multi-drug resistant bacterial strains and the human hepatocellular carcinoma cell line HepG2. The endophytic fungi isolated and identified from the A. graveolens samples included Diaporthe, Auxarthron, Arthrinium, Aspergillus, Microsporum, Dothiorella, Trichophyton, Lophiostoma, Penicillium, and Trichoderma species. The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) assay revealed that the A. graveolens extract exhibited the strongest antibacterial activity, with an MIC value of 4 μg/ml, followed by the Trichoderma sp. (5 μg/ml) and Penicillium sp. (6 μg/ml) extracts. Additionally, the crude extracts of Trichoderma sp., Penicillium sp., and Fusarium sp. demonstrated high anticancer activity against HepG2 cells, with inhibition rates ranging from 89 to 92% at a concentration of 50 μg/ml. Interestingly, the A. graveolens extract showed the most potent anticancer activity, with a 95% inhibition rate against HepG2 cells at the same concentration. These findings highlight the significant potential of endophytic fungi associated with A. graveolens, as a source of bioactive compounds with promising antibacterial and anticancer properties. The results reinforce the hypothesis that medicinal plants and their endophytic fungi can serve as an attractive alternative for the development of novel therapeutic agents, potentially offering a more sustainable and less harmful approach to disease management compared to traditional chemical-based methods.

Introduction

Each of the nearly 300,000 distinctive terrestrial plant species has the potential to harbor one or more of the millions of fungi that can serve as hosts for these plants (Rashmi et al., 2019). Endophytes are microorganisms that can exist dormant within the host’s tissues for an extended period without manifesting any outward symptoms of sickness (Mishra et al., 2021). They have the potential to be used as a biocontrol agent, which is becoming the preferred approach to disease management because of the various positive effects that it has on both human health and the preservation of the natural environment (Lahlali et al., 2022). They have the potential to be used as a biocontrol agent (Javaid et al., 2021; Ons et al., 2020). Endophytes have a variety of mechanisms, such as the capability to activate specific genes that are involved in induced systemic resistance (ISR), which can initiate a defense mechanism against an attack by pathogens, or the capability to formulate secondary metabolites and other chemical compounds that are directly toxic to the pathogens (Anjum et al., 2019; Khan et al., 2021). Endophytes are found in all plant species regardless of their place of origin. The ability to enter and thrive in the host tissues makes them unique, showing multidimensional interactions within the host plant. Several host activities are known to be influenced by the presence of endophytes. They can promote plant growth, elicit defense response against pathogen attack, and can act as remediators of abiotic stresses (Khare et al., 2018). The variety of fungi that can be found on or within the host plant is significantly influenced not only by the type of plant that acts as the host but also by the environmental conditions under which the plant grows or the geographical elements that are present (Dastogeer et al., 2020). According to the findings of the Sofy et al. (2020) study, endophytic fungal strains were collected from a wide range of plants. These plants included vegetables, fruits, fodder, cereal grains, trees, and other types of crops. In addition, endophytes are a rich and dependable source of genetic variation as well as biological innovation, and they have been employed in agriculture as well as pharmacology (for example, in medicines that combat cancer, fungi, viruses, and bacteria; Fontana et al., 2021).

Medicinal plant extracts may contain hundreds or even thousands of individual biologically active compounds in varying amounts that enable them to treat a wide range of conditions, the overall activity of medicinal plant extracts is the result of the combined action of multiple compounds with synergistic, additive or antagonistic activity (Vaou et al., 2022).

The plant species Anethum graveolens, more often referred to as dill, was chosen for the purpose of this inquiry (Sulieman et al., 2023). This plant belongs to the family Apiaceae, which also includes celery and parsley (Wang et al., 2022). The A. graveolens plant has been linked to having actions that include antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-diabetic, antibacterial, and anticancer (Ahmed et al., 2021). It has been established that extracts of A. graveolens possess significant antioxidant activity against fungi that are toxic to both plants and people (Al-Oqail and Farshori, 2021). The unchecked multiplication of cells, which ultimately leads to the creation of a tumor, is one of the defining characteristics of cancer (Compton and Compton, 2020). These cells are not the same as regular cells and do not participate in the standard mechanisms that regulate growth (Meng et al., 2006). According to Chen et al. (2015), the cytotoxic and anti-proliferative capabilities of plants and plant-derived components can be examined using a range of cancer cell lines by employing a number of different cytotoxic endpoints. These endpoints include MTT, neutral red uptake, and cellular morphology investigations (Cudazzo et al., 2019). Plants produce a substantial quantity of active components, and in comparison to other sources, these components from plants are less harmful (Alamgir, 2017). Buranrat et al. (2020) stated that one of the current trends in the fight against cancer is the quest for an anticancer agent derived from plants that have the power to both halt and reverse the progression of the disease.

Consequently, the objective of this research was to explore the biological activity (antibacterial and anticancer) of A. graveolens and endophyte fungi extracts against human cancer cells and multi-drug-resistant pathogenic bacteria, as well as to isolate and identify colonized endophytic fungi. Furthermore, the investigation endeavored to isolate and identify colonized endophytic fungi.

Materials and methods

Collection of plant

Matured healthy Anethum graveolens plant was collected from the farm of the Horticulture Department, Faculty of Agriculture, Ain Shams University. The plant’s stem, root, and leaves were cut off using a sterile knife, and they were then preserved in sterile plastic bags at 4°C until usage.

Endophytic fungi isolation

According to Lu et al. (2012) each sterile part was placed on potato dextrose agar (PDA) supplemented with penicillin and ̸ or streptomycin (3 mg/100 ml) and incubated at 28°C. On Sabouraud agar, the fungal hyphae tips were inoculated and incubated for 7 days at 24 until the selected single distinct colony morphotype (Zhang et al., 2019). The pure cultures isolates were maintained at 4°C on Sabouraud agar slant tubes.

Identification of endophytic fungi isolates

All isolates were described depending on their morphological characteristics (Barnett and Hunter, 1998; Hashem et al., 2019; Khalil et al., 2013; Khalil et al., 2019; Watanabe, 2010). Macroscopic morphological features including color, texture and diameter of colonies and microscopic characteristics including vegetative and reproductive structures of the fungi were noted.

Multi-drug pathogenic bacterial strains and culture conditions

Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 6538) Bacillus cereus (ATCC9634), Escherichia coli (ATCC10536), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ATCC10145), Salmonella typhi (ATCC 8435) were obtained from the Cairo MARCN Fac. of Agric. Ain Shams Univ. Egypt. Twenty-four hours before each experiment, bacteria were sub cultured on nutrient agar tubes at 37°C. These strains were used for the bioactive study of mycelia and culture broth extracts of isolated endophytic fungi.

Bioactivity assay

Extraction of endophytic fungi isolates

Each isolate was cultivated in a 500 ml Erlenmeyer’s flask containing 100 ml of Sabouraud broth at a pH 5.6, inoculated by fungal mycelium, and cultivated for 7 days at 220 rpm in an incubator shaker (Chathurdevi and Gowrie, 2016). From fermentation, fungal mycelia and broth medium were obtained. At 35°C, the solvent was combined and concentrated in a vacuum. The crude extracts were kept at −20°C until analysis.

Extraction maceration of A. graveolens plants

The 10 g of extracted plant material were shaken and stirred irregularly for 3 days while submerged in ethyl acetate (1:2 W/V) in an airtight, flat-bottomed jar. In a cell disintegrator, the sterile plant material was air-dried and homogenized, then extracted with ethyl acetate (1:2 W/V). Using 2 thicknesses of cheesecloth, the extraction was filtered. At 35°C, in a vacuum, the solvent was mixed and concentrated (Ibrahim et al., 2021).

Minimum inhibitory concentration determination

The inhibitory effects of 11 endophyte fungus extracts against five pathogenic bacterial strains were assessed by the microdilution method (Ibrahim et al., 2021). First, each well received 50 μl of the crude extract of each isolated fungus and 100 μl of the pathogenic bacteria culture (1*108 CFU/ml). The harmful bacterial strains were cultivated for 48 h at 37°C. Then, using an absorbance value near to the blank value and no discernible turbidity in the pores as the standard, the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of the chemical was calculated at 600 nm. The positive control for antibacterial was an antibiotic (ampicillin). Three repetitions were planned for each test. The microbial growth reduction percentage (GR %) was calculated using the broth microdilution method with the control treatment as the guideline as .

Where, T = replicates, C = cell concentrations under the control treatment. The outcomes of the experiment were recorded as mean ± SE of the triplicate samples (NCCLS/CLSI, 2015).

Biofilm-disruption assay

The tested multi-drug pathogenic bacterial strains were inoculated with 50 μl in nutrient broth media in 96-well microtiter and incubated for 72 h at 30°C to allow biofilm formation on the well (Dusane et al., 2010). Each endophytic fungal isolate extract was poured into microtiter wells to determine anti-disruptive activity. Planktonic cells were removed after 24 h. of incubation and washed twice with PBS. To evaluate absorbance at 595 nm, adherent bacteria were fixed in methanol (99%) and stained with crystal violet. Pathogen biofilms in wells not treated with extracts were used as controls. Biofilm disruption activity was measured as the percentage of biofilm formed in extracts-treated wells compared to untreated biofilms (control negative) and treated with (ampicillin) control positive.

Cytotoxicity activity (MTT assay)

The company for Biological Products and Vaccines (VACSERA) supplied the monolayer microtiter plate with HepG2 cell monolayers. MTT assay is a colorimetric assay that relies on intracellular mitochondrial succinate dehydrogenase enzymes in metabolically active cells to convert the yellow, With certain adjustments, according to (Mosmann, 1983). For a 48-h exposure period, cell monolayers were treated in quadrature with test IC50 for each extract. On a Tristar LB2 microplate reader (Berthold, Germany), the absorbance was measured at 492 nm against a blank (no cells) after adding DMSO (100 μl/well) to dissolve the formazan crystals for 10 min of shaking. The following formula was used to determine the viability percentage: Inhibiting cells (%) = 100 − Surviving cells; % viability = (At − Ab)/(Ac − Ab)100.

Results

Eleven fungal endophytes isolation and identification

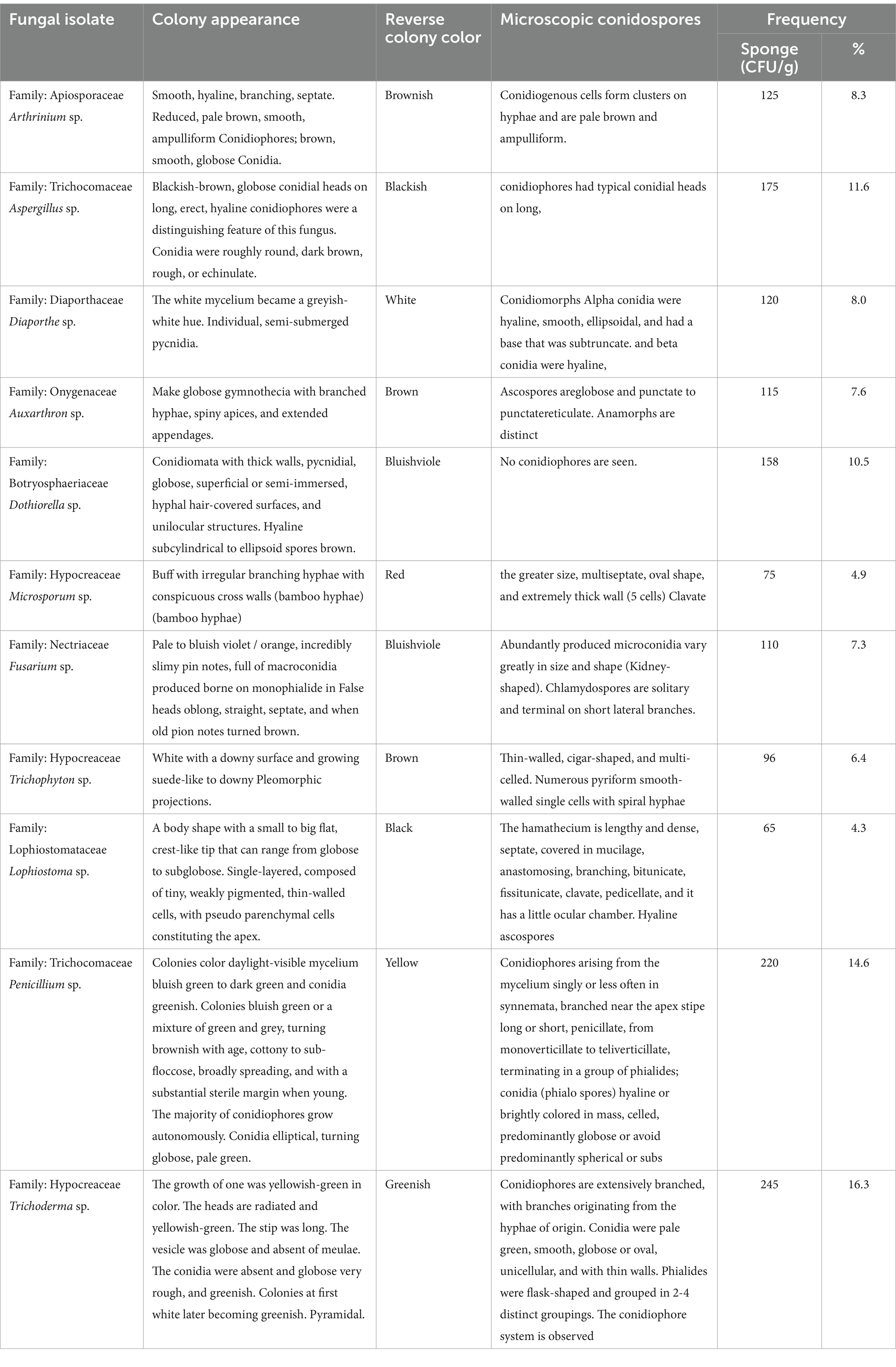

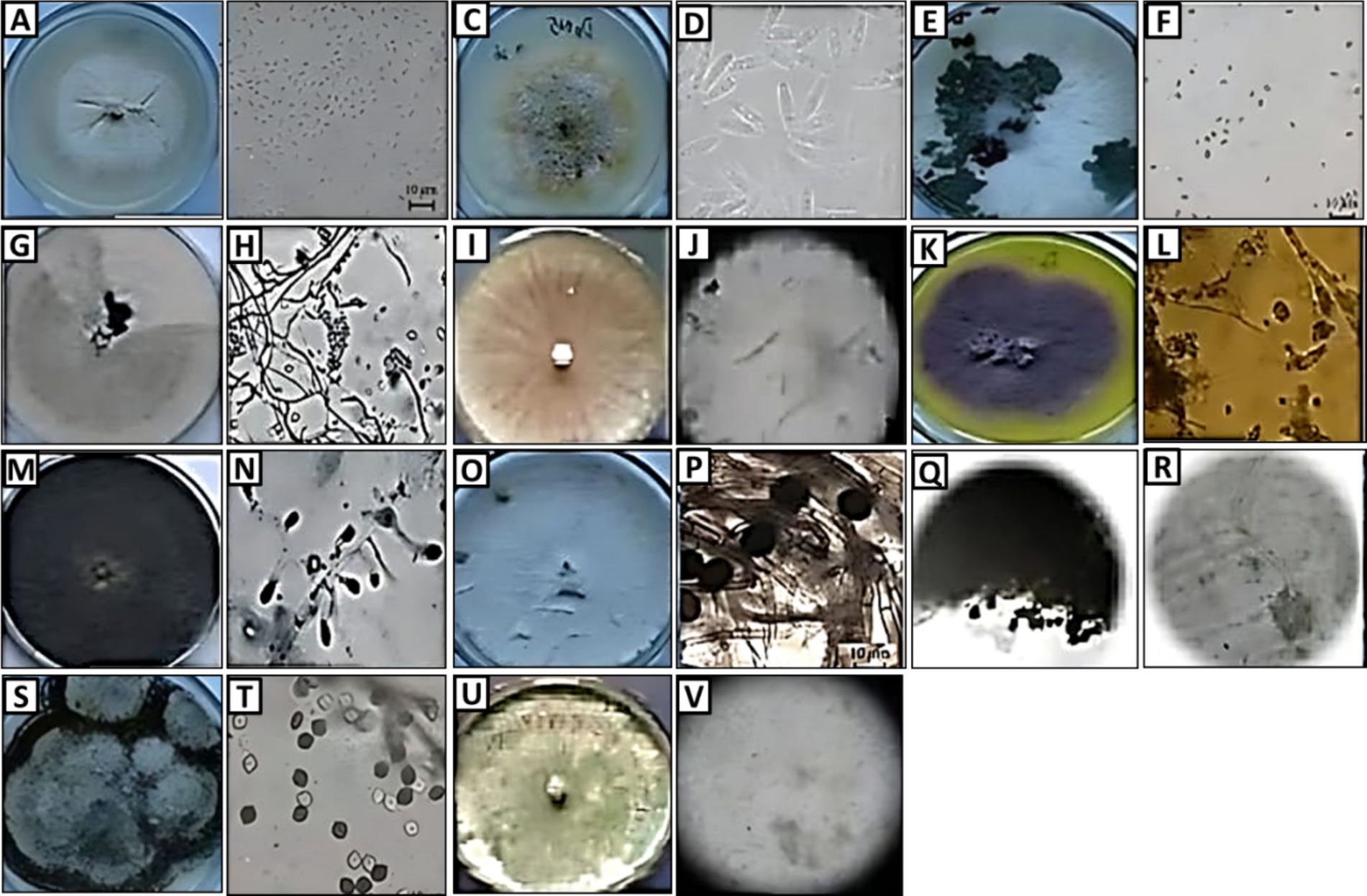

Eleven fungal endophytes were isolated from A. graveolens and identified according to morph type characteristics, colony appearance, reverse colony, and microscopic conidia. The isolated endophytes fungi belonged to nine different families, Trichocomaceae; Onygenaceae; Apiosporaceae; Diaporthaceae; Hypocreaceae; Nectriaceae; Lophiostomataceae; Botryosphaeriaceae and Trichocomacea. The 11 fungal endophytic were Aspergillus sp. Trichoderma sp. Penicillium sp. Dothiorella sp. Arthrinium sp. Fusarium sp. Diaporthe sp. Microsporum sp. Auxarthron sp. Trichophyton sp. and Lophiostoma sp. The most abundant fungi were Trichoderma sp. (16.3%), Penicillium sp. with (14.6%), Aspergillus sp. (11.6%), Dothiorella sp. (10.5%), Arthrinium sp. (8.3%), Diaporthe sp. with (8.0%), Auxarthron sp. (7.6%), Fusarium sp. (7.3%), Trichophyton sp. (6.4%), Microsporum sp. (4.9%) and Lophiostoma sp. with (4.3%; Figure 1).

Figure 1. Morphology (colony appearance, conidia, and hypha) of endophytic fungi: Arthrinium sp. (A,B), Auxarthron sp. (C,D), Dothiorella sp. (E,F), Trichoderma sp. (G,H), Fusarium sp. (I,J), Penicillium sp. (K,L), Trichophyton sp. (M,N), Microsporum sp. (O,P), Aspergillus sp. (Q,R), Lophiostoma sp. (S,T), and Diaporthe sp. (U,V).

Antibacterial activity

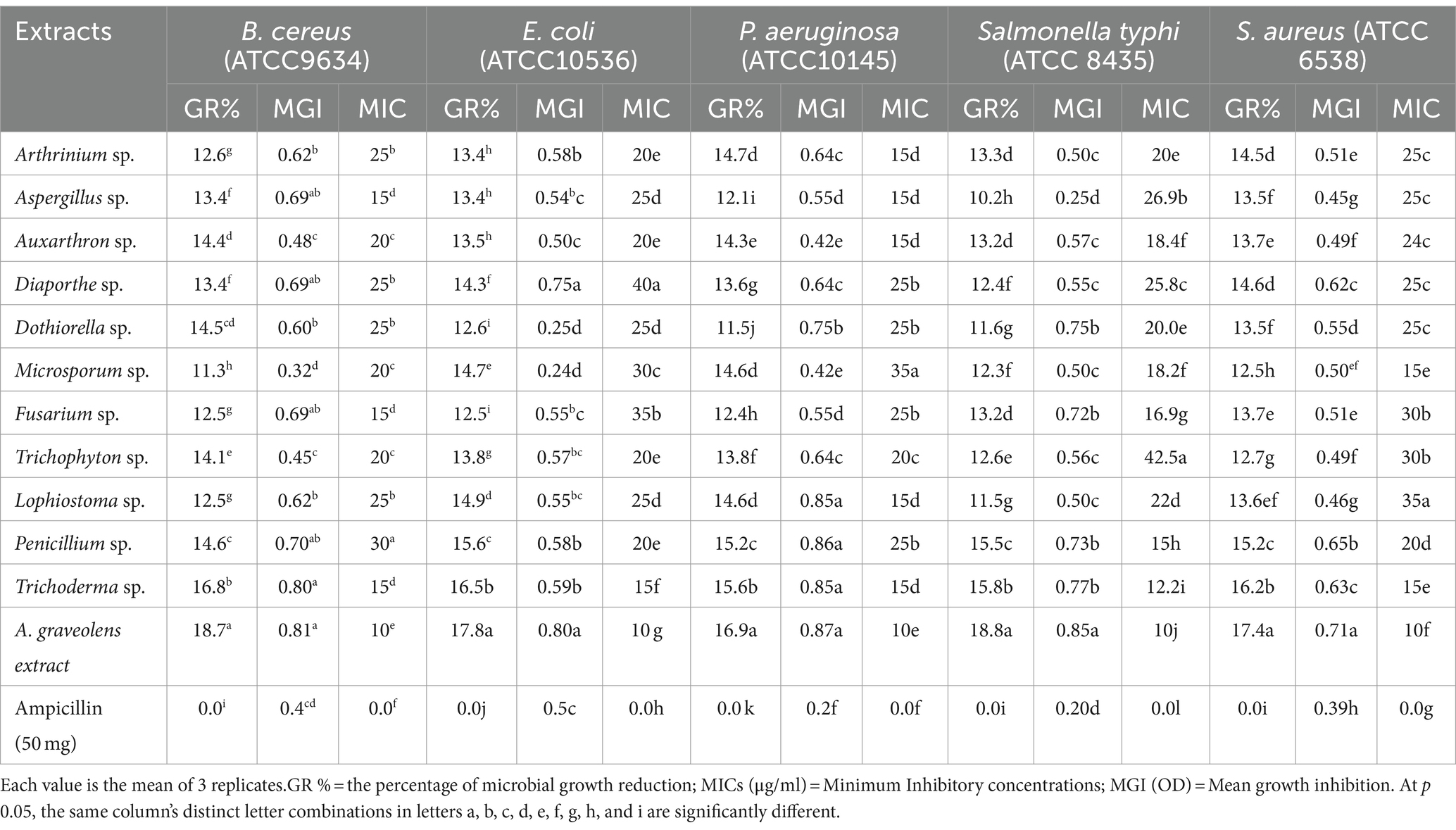

Regarding the antibacterial activities, percentage of microbial growth inhibition (GR) ranged from 10.2 to 18.8%, mean growth inhibition (MGI) ranged from 0.24 to 0.87 OD, and minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) ranged from 10 to 42.5 (μg/ml) against all tested multi-drug pathogenic bacterial strains under research. The strongest antibacterial activity was demonstrated by A. graveolens, Trichoderma sp. and Penicillium sp. extracts. Additionally, data showed that Microsporum sp. exhibited the lowest antibacterial activity against Gram-positive B. cereus and S. aureus. While, Aspergillus sp. against Gram-negative E. coli, P. aeruginosa, and Salmonella typhi (Table 1).

Table 1. A. graveolens and fungal endophytes extract against selected multi-drug pathogenic bacterial strains.

Metabolite broths of all 11 endophyte fungi isolate extract were growth reduction of tested pathogenic bacteria with ranged from 11.3 to 16.8 (B. cereus), 12.5–16.5 (E.coli), 11.5–15.6 (P. aeruginosa), 10.2–15.8 (Salmonella typhi) 12.5–16.2 (S. aureus) as well as A.graveolens extracts, 18.7, 17.8, 16.9, 18.8, and 17.4, respectively compared with ampicillin (50 mg). The mean growth inhibition was recorded in all tested multi-drug pathogenic bacterial strains ranging from 0.32 to 0.81, 0.24 to 0.80, 0.42 to 0.87, 0.25 to 0.85, and 0.45 to 0.71 OD for B. cereus, E. coli, P. aeruginosa, Salmonella, and S. aureus, respectively by broth micro-dilution method compared to ampicillin (50 mg) was 0.4, 0.5, 0.2, 0.2, 0.39 OD. The MIC values were recorded against tested pathogenic bacterial strains ranging from 10 to 42.5 μg/ml. Generally, results showed that the MIC values of A. graveolens extract were the lowest followed by Trichoderma sp. then other endophyte fungi isolates.

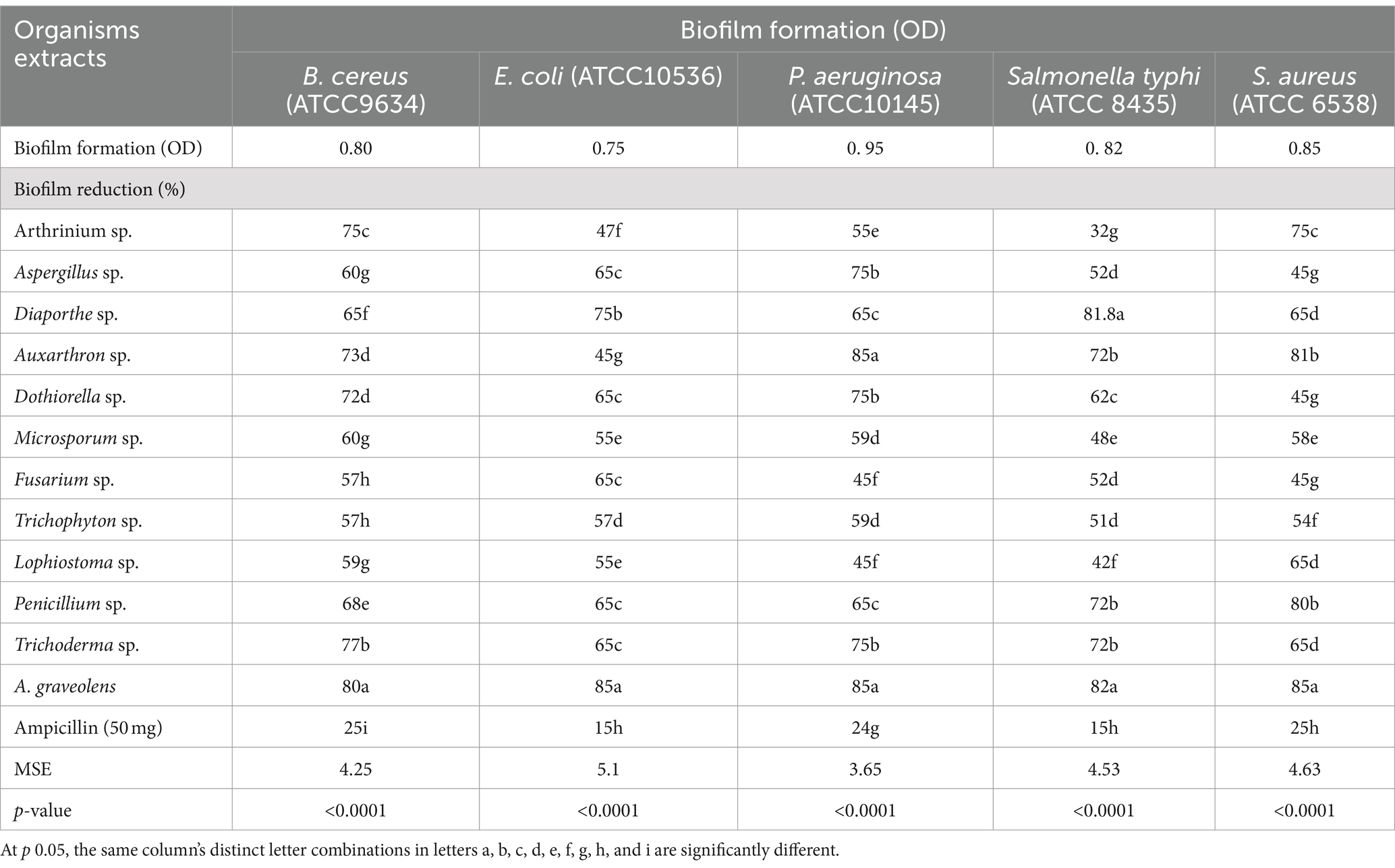

Biofilm disruption

The percentage of biofilm reduction of ethyl acetate extracts from plant tissues and isolated fungal endophytes compared to the antibacterial drug ampicillin All tested pathogenic bacteria have biofilm formation with different values of 0.80, 0.75, 0.95, 0.82, and 0.85 with optical density (OD) for B. cereus, E.coli, P. aeruginosa, S. typhi, and S. aureus, respectively (Table 2).

Table 2. Biofilm disruption assay of ethyl acetate extract for fungal endophytes and A. graveolens compared to ampicillin.

Regarding extract of fungal endophytes, showed significant anti-biofilm activity against B. cereus, E.coli, P. aeruginosa, S. typhi, and S. aureus with an inhibition rate ranging between 57 to 77%, 45 to 75%, 45 to 85%, 42 to 82%, and 45 to 81%, respectively. Also, results indicated that the highest anti-biofilm activity was achieved by A. graveolens extract significantly inhibited the biofilm formation of B. cereus, E.coli, P. aeruginosa, S. typhi, and S. aureus with 80, 85, 85, 82, 85%, respectively. However, ampicillin (50 mg) showed the lowest anti-biofilm activity with a value of 25, 15, 24, 15, and 25% for B. cereus, E.coli, P. aeruginosa, S. typhi, and S. aureus, respectively.

Anti-tumor activity

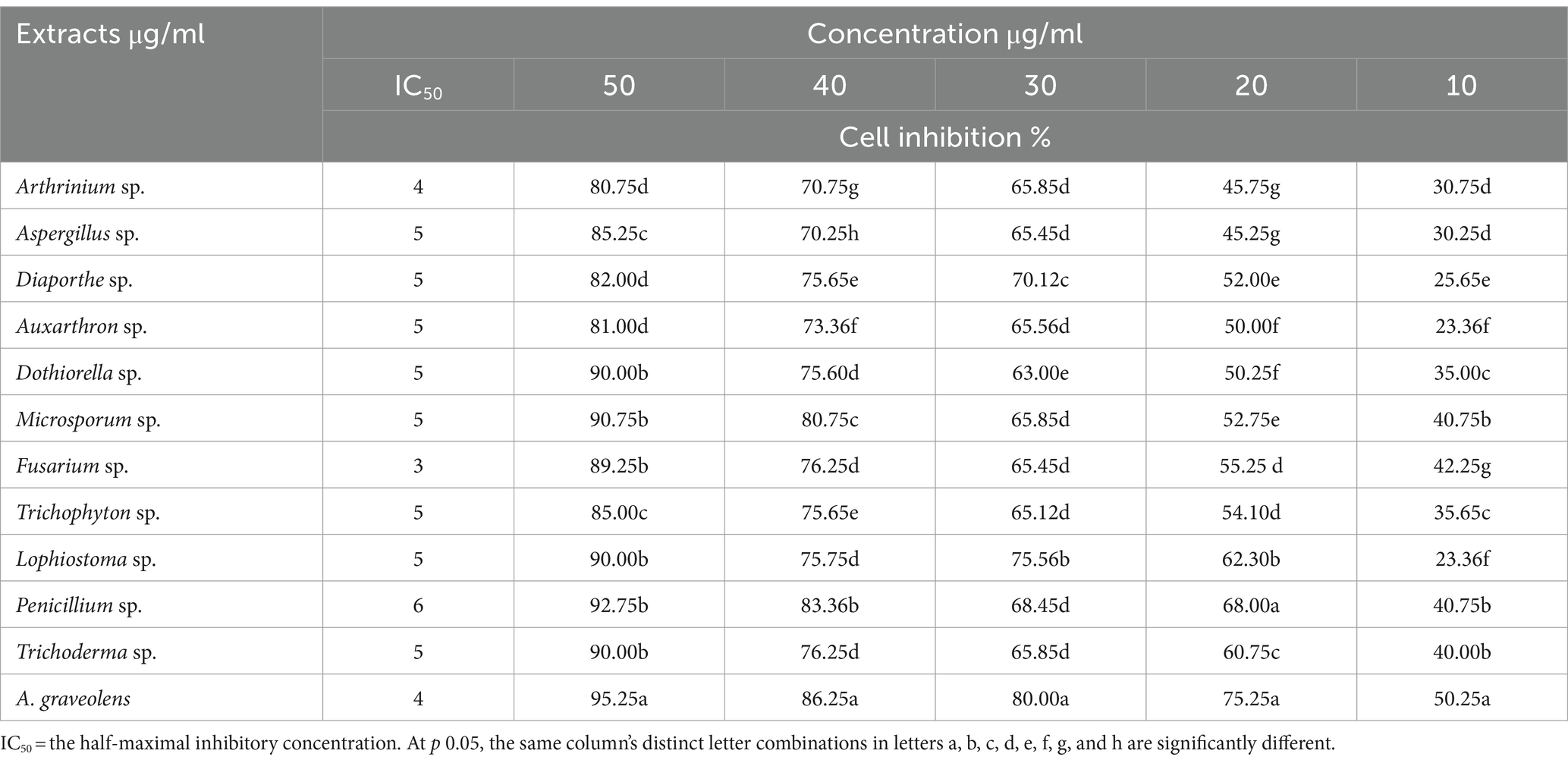

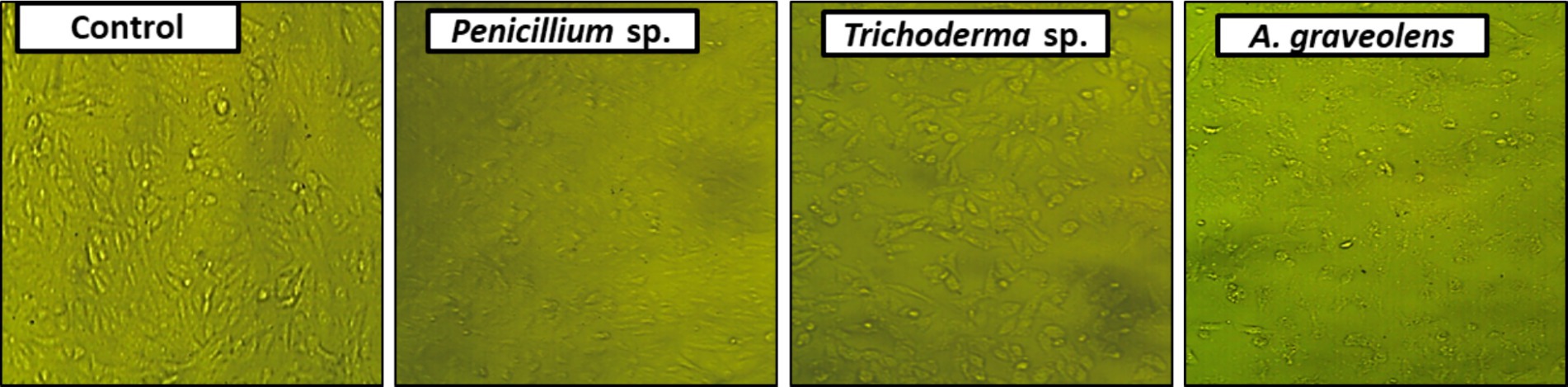

In the initial screening of 11 endophytic fungi and plant extracts for antitumor activities, the extracts of A. graveolens, Trichoderma sp. and Penicillium sp. displayed the greatest anticancer activity against human HCC (HepG2) compared to the control (0.5% DMSO). The morphology of treated cells exhibited symptoms of toxicity, involving shrinkage, cell rounding, and/or monolayer rupture representing effects on HepG2 cells. At (50 μg/ml) the crude extract of Trichoderma sp. was the best anticancer activity against HepG2 cells among the studied extracts. Plant extract > Penicillium sp. > Trichoderma sp. are the most active fungal endophytic extracts against the HepG2 tumor (Tables 3, 4; Figure 2).

Table 3. Endophytic fungi ethyl acetate and A. graveolens extract and their anticancer activity against (HepG2) cells.

Figure 2. Photomicrographs displaying alterations in HepG2 monolayer morphology following treatment with a specific concentration of Penicillium sp. Trichoderma sp. or Plant (A. graveolens) extracts, as well as a control (0.5% DMSO). Monolayer rupture, cell rounding, cell contraction, and/or cell lysis are symptoms of cytotoxicity.

Discussion

Fungal endophytes are fungi that live within plant tissues without harming the host. They can enhance plant defense, stress tolerance, and nutrient acquisition (Badawy et al., 2021; Sharaf et al., 2022). Endophytes form symbiotic relationships, benefiting both the host plant and the fungus. Understanding fungal endophytes has applications in agriculture, forestry, and natural product development (Abdelaziz et al., 2022a; Abdelaziz et al., 2022b; Attia et al., 2022). In this study, 11 endophyte fungi were isolated from multipurpose plant A. graveolens. The isolated fungal endophytes belonged to 9 different families: Apiosporaceae, Trichocomaceae, Diaporthaceae, Onygenaceae, Botryosphaeriaceae, Hypocreaceae, Nectriaceae, Lophiostomataceae and Trichocomaceae. The more frequent genus are Aspergillus sp. Trichoderma sp. Penicillium sp. and Dothiorella sp. Where the number and type of isolated fungi differ according to the plant variety and plant tissues. Daldinia sp. and Lentinus sp. were isolated from plant leaf tissue while Rigidoporus sp. and Polyporales sp. were from root tissue (Maadon et al., 2018). Penicillium sp. two of Aspergillus spp. and Trametes hirsuta were identified in coconut (Salo and Novero, 2020). Fusarium chlamydosporum, Phoms sp. Fusarium oxysporum, Alternaria solani, Fusarium equiseti, Stemphylium sp., 8 from leaf segments of Avicennia marina (Khalil et al., 2021). We observed that Dothiorella sp. which is isolated from salt-tolerant plant like Mangrove (Cadamuro et al., 2021) is among the more frequent endophytes in our target plant, this indicates to may be A. graveolen has microbe-plant interaction mechanisms for salt tolerance but this needs more investigation.

For the development of prospective cytotoxic and antibacterial medications, endophytic fungi of medicinal plants are useful sources of active natural compounds (Mohamed et al., 2022), these compounds may be secreted or not (Charria-Girón et al., 2021; Gu et al., 2022). Fungal endophytes are known to produce a variety of antimicrobial compounds that can inhibit the growth of pathogenic bacteria, fungi, and viruses (Elghaffar et al., 2022; Hashem et al., 2022). These antimicrobial metabolites help protect the host plant from infectious diseases, making endophytes a promising source for discovering new antimicrobial agents with potential applications in medicine and agriculture (Hashem et al., 2023).

In the current study, the 11 endophyte fungi secreted compounds that inhibited the tested pathogenic bacteria, B. cereus; E.coli; S. aureus, S. typhi; P. aeruginosa, with mean growth inhibition (MGI) ranging from 0.24 to 0.87 OD. In other studies, the inhibitory activity reached 96% of the total fungi isolated from Artemisia argyi namely, Alternaria, Colletotrichum, Phoma, Diaporthe, Gibberella, Trichoderma, Chaetomium and Fusarium against pathogenic microorganisms (Gu et al., 2022). Additionally, MIC values against the pathogenic bacterial strains that were examined ranged from 10 to 42.5 g/ml. Fusarium oxysporum extract, on the other hand, has demonstrated broad antagonistic activity against a wide spectrum of bacteria, with MIC values ranging from 0.156 to 5.0 mg/ml and MBC values ranging from 0.625 to 10.0 mg/ml. Additionally, it demonstrated suppression of Saccharomyces cerevisiae but not of Candida albicans and Trichophyton interdigitale (Chutulo and Chalannavar, 2020; Metwaly, 2019; Raina et al., 2018). It is important to note that we were successful in this work in inhibiting the pathogenic bacterial strains with low MIC values, demonstrating the potency of the compounds produced by the endophytic fungi isolates. Regarding biofilm disruption, the extract of fungal endophytes showed significant antibiofilm activity against five bacteria B. cereus, P. aeruginosa, S. aureus, E. coli and S. typhi. Whereas, many extracts of fungal endophytes showed antibiofilm activity against Pseudomonas aeruginosa only. This is evident in the following studies endophytic fungi, such as Aspergillus nidulans and Alternaria alternata, have excellent antibiofilm activity against pathogenic bacteria (Meenambiga and Rajagopal, 2018), Alternaria alternate showed anti-quorum sensing activity against Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Rashmi et al., 2018) and Fusarium sp. Pestalotiopsis sp. Phoma sp. Aspergillus sp. Trichoderma sp. Penicillium sp. Phomopsis sp. and Colletotrichum sp. Chlamydomonas sp. extracts showed significant inhibition in biofilm formation against Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Dawande et al., 2019; Nithya et al., 2014). Furthermore, we observed high levels of anticancer activity of crude extracts of A. graveolens; Trichoderma sp. and Penicillium sp. against (HepG2) cells with IC50 4, 5, and 6 μg/ml, respectively at concentrations of 50 μg/ml. According to studies, Penicillium rubens, Alternaria alternata, and Aspergillus niger extracts showed negligible cytotoxicity on normal human lung at concentrations up to 400 g/ml (Al-Rajhi et al., 2022). Penicillium rubens and Aspergillus niger extract exhibited inhibitory activity against prostate cancer proliferation with concentrations of 48 and 4.4 μg/ml, respectively, with mortality levels of 75.91 and 76.2% (Heydari et al., 2019). However, the crude extract of Aspergillus tubingensis up to 19 μg/ml showed strong antiproliferative activity against colon, hepatocellular, and breast carcinoma cell lines (Elkhouly et al., 2021). This study reinforced the hypothesis that medicinal plants and fungi isolated from them play an important role as anti-tumor compounds and offer an attractive alternative for disease management without the negative impact of chemicals.

Conclusion

The present study demonstrates the successful isolation and identification of various endophytic fungi from the medicinal plant Anethum graveolens. These endophytic fungi, including Diaporthe, Auxarthron, Arthrinium, Aspergillus, Microsporum, Dothiorella, Trichophyton, Lophiostoma, Penicillium, and Trichoderma, were found to possess potent antibacterial and anticancer properties. The findings highlight the significant potential of these endophytic fungi as a source of bioactive compounds. The extracts from Trichoderma sp., Penicillium sp., and Fusarium sp. exhibited high anticancer activity against the human hepatocellular cancer cell line HepG2, with inhibition rates ranging from 89 to 92% at a concentration of 50 μg/ml. Interestingly, the extract from the host plant A. graveolens showed the most potent anticancer activity, with a 95% inhibition rate against HepG2 cells at the same concentration. These results reinforce the hypothesis that medicinal plants and their associated endophytic fungi can serve as a valuable resource for the discovery of novel therapeutic compounds, offering an attractive alternative to traditional chemical-based approaches for disease management.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the studies on humans in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements because only commercially available established cell lines were used.

Author contributions

HE-Z: Writing – original draft, Supervision, Software, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation. NA: Writing – original draft, Validation, Software, Methodology, Investigation. AF: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Data curation, Conceptualization. MSA: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Software, Project administration, Methodology. MA-M: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Investigation, Funding acquisition. ME-T: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation. NE-D: Writing – original draft, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology. MA: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The authors extend their appreciation to King Saud University for funding this work through research supporting project (RSPD2024R678), Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Department of Agricultural Microbiology, Faculty of Agriculture, Moshtohor, Benha University, Qalyubia, Egypt Also, The authors would like to thank the Botany and Microbiology Department, Faculty of Science, Al-Azhar University for promoting this research.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abdelaziz, A. M., El-Wakil, D. A., Attia, M. S., Ali, O. M., Abd Elgawad, H., and Hashem, A. H. (2022a). Inhibition of aspergillus flavus growth and aflatoxin production in Zea mays L. using endophytic Aspergillus fumigatus. J. Fungi 8:482. doi: 10.3390/jof8050482

Abdelaziz, A. M., Kalaba, M. H., Hashem, A. H., Sharaf, M. H., and Attia, M. S. (2022b). Biostimulation of tomato growth and biocontrol of fusarium wilt disease using certain endophytic fungi. Bot. Stud. 63:34. doi: 10.1186/s40529-022-00364-7

Ahmed, S. S. T., Fahim, J., and Abdelmohsen, U. R. (2021). Chemical and biological potential of Ammi visnaga (L.) Lam. and Apium graveolens L.: a review (1963-2020). J. Adv. Biomed. Pharm. Sci. 4, 160–176. doi: 10.21608/jabps.2021.55949.1115

Alamgir, A. (2017). Therapeutic use of medicinal plants and their extracts, vol. 1: Springer, International Publishing AG.

Al-Oqail, M. M., and Farshori, N. N. (2021, 2021). Antioxidant and anticancer efficacies of anethum graveolens against human breast carcinoma cells through oxidative stress and caspase dependency. Bio Med. Res. Int. 2021, 1–12. doi: 10.1155/2021/5535570

Al-Rajhi, A. M., Mashraqi, A., Al Abboud, M. A., Shater, A.-R. M., Al Jaouni, S. K., Selim, S., et al. (2022). Screening of bioactive compounds from endophytic marine-derived fungi in Saudi Arabia: antimicrobial and anticancer potential. Life 12:1182. doi: 10.3390/life12081182

Anjum, R., Afzal, M., Baber, R., Khan, M. A. J., Kanwal, W., Sajid, W., et al. (2019). Endophytes: as potential biocontrol agent—review and future prospects. J. Agric. Sci. 11, 113–125. doi: 10.5539/jas.v11n4p113

Attia, M. S., Hashem, A. H., Badawy, A. A., and Abdelaziz, A. M. (2022). Biocontrol of early blight disease of eggplant using endophytic Aspergillus terreus: improving plant immunological, physiological and antifungal activities. Bot. Stud. 63:26. doi: 10.1186/s40529-022-00357-6

Badawy, A. A., Alotaibi, M. O., Abdelaziz, A. M., Osman, M. S., Khalil, A. M. A., Saleh, A. M., et al. (2021). Enhancement of seawater stress tolerance in barley by the endophytic fungus Aspergillus ochraceus. Metabolites 11, 11:428:428. doi: 10.3390/metabo11070428

Barnett, H., and Hunter, B. (1998). Illustrated genera of imperfect fungi : Minnesota The American Phytopathological Society, Minneapolis, Burgess Publishing Co. 200.

Buranrat, B., Boontha, S., Temkitthawon, P., and Chomchalao, P. (2020). Anticancer activities of Careya arborea Roxb on MCF-7 human breast cancer cells. Biologia 75, 2359–2366. doi: 10.2478/s11756-020-00535-6

Cadamuro, R. D., da Silveira Bastos, I. M. A., Silva, I. T., da Cruz, A. C. C., Robl, D., Sandjo, L. P., et al. (2021). Bioactive compounds from mangrove endophytic fungus and their uses for microorganism control. J. Fungi 7:455. doi: 10.3390/jof7060455

Charria-Girón, E., Espinosa, M. C., Zapata-Montoya, A., Méndez, M. J., Caicedo, J. P., Dávalos, A. F., et al. (2021). Evaluation of the antibacterial activity of crude extracts obtained from cultivation of native endophytic fungi belonging to a tropical montane rainforest in Colombia. Front. Microbiol. 12:716523. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.716523

Chathurdevi, G., and Gowrie, S. (2016). Endophytic fungi isolated from medicinal plant—a source of potential bioactive metabolites. Int. J. Curr. Pharm. Res. 8, 50–56.

Chen, W.-L., Barszczyk, A., Turlova, E., Deurloo, M., Liu, B., Yang, B. B., et al. (2015). Inhibition of TRPM7 by carvacrol suppresses glioblastoma cell proliferation, migration and invasion. Oncotarget 6, 16321–16340. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3872

Chutulo, E. C., and Chalannavar, R. K. (2020). Antimicrobial activity of fusarium oxysporum, endophytic fungus, isolated from Psidium guajava L (White fruit). Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 11, 5844–5855.

Compton, C., and Compton, C. (2020). Cancer initiation, promotion, and progression and the acquisition of key behavioral traits : Springer, Springer International Publishing.

Cudazzo, G., Smart, D. J., McHugh, D., and Vanscheeuwijck, P. (2019). Lysosomotropic-related limitations of the BALB/c 3T3 cell-based neutral red uptake assay and an alternative testing approach for assessing e-liquid cytotoxicity. Toxicol. in Vitro 61:104647. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2019.104647

Dastogeer, K. M., Tumpa, F. H., Sultana, A., Akter, M. A., and Chakraborty, A. (2020). Plant microbiome–an account of the factors that shape community composition and diversity. Curr. Plant Biol. 23:100161. doi: 10.1016/j.cpb.2020.100161

Dawande, A. Y., Gajbhiye, N. D., Charde, V. N., and Banginwar, Y. S. (2019). Assessment of endophytic fungal isolates for its Antibiofilm activity on Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Int. J. Sci. Res. Biol. Sci. 6, 81–86. doi: 10.26438/ijsrbs/v6i3.8186

Dusane, D. H., Nancharaiah, Y. V., Zinjarde, S. S., and Venugopalan, V. P. (2010). Rhamnolipid mediated disruption of marine Bacillus pumilus biofilms. Colloids Surf. B: Biointerfaces 81, 242–248. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2010.07.013

Elghaffar, R. Y. A., Amin, B. H., Hashem, A. H., and Sehim, A. E. (2022). Promising endophytic Alternaria alternata from leaves of Ziziphus spina-christi: phytochemical analyses, antimicrobial and antioxidant activities. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 194, 3984–4001. doi: 10.1007/s12010-022-03959-9

Elkhouly, H. I., Hamed, A. A., El Hosainy, A. M., Ghareeb, M. A., and Sidkey, N. M. (2021). Bioactive secondary metabolite from endophytic aspergillus tubenginses ASH4 isolated from Hyoscyamus muticus: antimicrobial, antibiofilm, antioxidant and anticancer activity. Pharm. J. 13, 434–442. doi: 10.5530/pj.2021.13.55

Fontana, D. C., de Paula, S., Torres, A. G., de Souza, V. H. M., Pascholati, S. F., Schmidt, D., et al. (2021). Endophytic Fungi: biological control and induced resistance to Phytopathogens and abiotic stresses. Pathogens 10:570. doi: 10.3390/pathogens10050570

Gu, H., Zhang, S., Zhao, F., and Tian, Y. (2022). Antimicrobial potential of endophytic fungi from Artemisia argyi and bioactive metabolites from Diaporthe sp. AC1. Front. Microbiol. 13:908836. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.908836

Hashem, A. H., Attia, M. S., Kandil, E. K., Fawzi, M. M., Abdelrahman, A. S., Khader, M. S., et al. (2023). Bioactive compounds and biomedical applications of endophytic fungi: a recent review. Microb. Cell Factories 22:107. doi: 10.1186/s12934-023-02118-x

Hashem, A. H., Hasanin, M. S., Khalil, A. M. A., and Suleiman, W. B. (2019). Eco-green conversion of watermelon peels to single cell oils using a unique oleaginous fungus: Lichtheimia corymbifera AH13. Waste Biomass Valoriz. 11:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s12649-019-00850-3

Hashem, A. H., Shehabeldine, A. M., Abdelaziz, A. M., Amin, B. H., and Sharaf, M. H. (2022). Antifungal activity of endophytic aspergillus terreus extract against some Fungi causing Mucormycosis: ultrastructural study. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 194, 3468–3482. doi: 10.1007/s12010-022-03876-x

Heydari, H., Koc, A., Simsek, D., Gozcelioglu, B., Altanlar, N., and Konuklugil, B. (2019). Isolation, identification and bioactivity screening of Turkish marine-derived Fungi. Farmacia 67, 780–788. doi: 10.31925/farmacia.2019.5.5

Ibrahim, M., Oyebanji, E., Fowora, M., Aiyeolemi, A., Orabuchi, C., Akinnawo, B., et al. (2021). Extracts of endophytic fungi from leaves of selected Nigerian ethnomedicinal plants exhibited antioxidant activity. BMC Comp. Med. Therap. 21, 1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12906-021-03269-3

Javaid, A., Ali, A., Shoaib, A., and Khan, I. (2021). Alleviating stress of sclertium rolfsii on growth of chickpea var. bhakkar-2011 by Trichoderma harzianum and T viride. J. Anim. Plant Sci. 31:1755–1761. doi: 10.1186/s12906-021-03269-3

Khalil, A., Abdelaziz, A., Khaleil, M., and Hashem, A. (2021). Fungal endophytes from leaves of Avicennia marina growing in semi-arid environment as a promising source for bioactive compounds. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 72, 263–274. doi: 10.1111/lam.13414

Khalil, A. M., El-Sheikh, H. H., and Sultan, M. H. (2013). Distribution of fungi in mangrove soil of coastal areas at Nabq and Ras Mohammed protectorates. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. App. Sci. 2, 264–274.

Khalil, A. M. A., Hashem, A. H., and Abdelaziz, A. M. (2019). Occurrence of toxigenic Penicillium polonicum in retail green table olives from the Saudi Arabia market. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 21:101314. doi: 10.1016/j.bcab.2019.101314

Khan, I. H., Javaid, A., and Ahmed, D. (2021). Trichoderma viride controls Macrophomina phaseolina through its DNA disintegration and production of antifungal compounds. Int. J. Agric. Biol. 25, 888–894. doi: 10.17957/IJAB/15.1743

Khare, E., Mishra, J., and Arora, N. K. (2018). Multifaceted interactions between endophytes and plant: developments and prospects. Front. Microbiol. 9:2732. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02732

Lahlali, R., Ezrari, S., Radouane, N., Kenfaoui, J., Esmaeel, Q., el Hamss, H., et al. (2022). Biological control of plant pathogens: a global perspective. Microorganisms 10:596. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms10030596

Lu, Y., Chen, C., Chen, H., Zhang, J., and Chen, W. (2012). Isolation and identification of endophytic fungi from Actinidia macrospermaand investigation of their bioactivities. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2012, 1–8. doi: 10.1155/2012/382742

Maadon, S. N., Ahmad Wakid, S., Zainudin, I. I., Rusli, L. S., Mohd Zan, M. S., Hasan, N.' A., et al. (2018). Isolation and identification of endophytic fungi from UiTM reserve forest. Negeri Sembilan Sains Malaysiana 47, 3025–3030. doi: 10.17576/jsm-2018-4712-12

Meenambiga, S., and Rajagopal, K. (2018). Antibiofilm activity and molecular docking studies of bioactive secondary metabolites from endophytic fungus Aspergillus nidulans on oral Candida albicans. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 8, 37–45. doi: 10.7324/JAPS.2018.8306

Meng, F., Henson, R., Lang, M., Wehbe, H., Maheshwari, S., Mendell, J. T., et al. (2006). Involvement of human micro-RNA in growth and response to chemotherapy in human cholangiocarcinoma cell lines. Gastroenterology 130, 2113–2129. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.02.057

Metwaly, A. (2019). Comparative biological evaluation of four endophytic fungi isolated from nigella sativa seeds Al-Azhar. J. Pharm. Sci. 59, 123–136. doi: 10.21608/ajps.2019.64111

Mishra, S., Bhattacharjee, A., and Sharma, S. (2021). An ecological insight into the multifaceted world of plant-endophyte association. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 40, 127–146. doi: 10.1080/07352689.2021.1901044

Mohamed, H., Ebrahim, W., El-Neketi, M., Awad, M. F., Zhang, H., Zhang, Y., et al. (2022). In vitro phytobiological investigation of bioactive secondary metabolites from the malus domestica-derived endophytic fungus Aspergillus tubingensis strain AN103. Molecules 27:3762. doi: 10.3390/molecules27123762

Mosmann, T. (1983). Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J. Immunol. Methods 65, 55–63. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4

NCCLS. (2015). Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. Approved standard, document M07-A10. Wayne, PA, USA: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards.

Nithya, C., LewisOscar, F., Kanaga, S., Kavitha, R., Bakkiyaraj, D., Arunkumar, M., et al. (2014). Biofilm inhibitory potential of Chlamydomonas sp. extract against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Algal Biomass Util. 5, 74–81.

Ons, L., Bylemans, D., Thevissen, K., and Cammue, B. P. (2020). Combining biocontrol agents with chemical fungicides for integrated plant fungal disease control. Microorganisms 8:1930. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8121930

Raina, D., Singh, B., Bhat, A., Satti, N., and Singh, V. K. (2018). Antimicrobial activity of endophytes isolated from Picrorhiza kurroa. Indian Phytopathol. 71, 103–113. doi: 10.1007/s42360-018-0015-1

Rashmi, M., Kushveer, J., and Sarma, V. (2019). A worldwide list of endophytic fungi with notes on ecology and diversity. Mycosphere 10, 798–1079. doi: 10.5943/mycosphere/10/1/19

Rashmi, M., Meena, H., Meena, C., Kushveer, J., Busi, S., Murali, A., et al. (2018). Anti-quorum sensing and antibiofilm potential of Alternaria alternata, a foliar endophyte of Carica papaya, evidenced by QS assays and in-silico analysis. Fungal Biol. 122, 998–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.funbio.2018.07.00

Salo, E. N., and Novero, A. (2020). Identification and characterisation of endophytic bacteria from coconut (Cocos nucifera) tissue culture. Trop. Life Sci. Res. 31, 57–68. doi: 10.21315/tlsr2020.31.1.4

Sharaf, M. H., Abdelaziz, A. M., Kalaba, M. H., Radwan, A. A., and Hashem, A. H. (2022). Antimicrobial, antioxidant, cytotoxic activities and phytochemical analysis of fungal endophytes isolated from Ocimum Basilicum. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 194, 1271–1289. doi: 10.1007/s12010-021-03702-w

Sofy, A. R., Dawoud, R. A., Sofy, M. R., Mohamed, H. I., Hmed, A. A., and El-Dougdoug, N. K. (2020). Improving regulation of enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidants and stress-related gene stimulation in cucumber mosaic cucumovirus-infected cucumber plants treated with glycine betaine, chitosan and combination. Molecules 25:2341. doi: 10.3390/molecules25102341

Sulieman, A. M. E., Abdallah, E. M., Alanazi, N. A., Ed-Dra, A., Jamal, A., Idriss, H., et al. (2023). Spices as sustainable food preservatives: a comprehensive review of their antimicrobial potential. Pharmaceuticals 16:1451. doi: 10.3390/ph16101451

Vaou, N., Stavropoulou, E., Voidarou, C., Tsakris, Z., Rozos, G., Tsigalou, C., et al. (2022). Interactions between medical plant-derived bioactive compounds: focus on antimicrobial combination effects. Antibiotics 11:1014. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics11081014

Wang, X.-J., Luo, Q., Li, T., Meng, P. H., Pu, Y. T., Liu, J. X., et al. (2022). Origin, evolution, breeding, and omics of Apiaceae: a family of vegetables and medicinal plants. Hortic. Res. 9:uhac076. doi: 10.1093/hr/uhac076

Watanabe, T. (2010). Pictorial atlas of soil and seed fungi: Morphologies of cultured fungi and key to species, Boca Raton: CRC press.

Keywords: endophytic fungi, medicinal plants, Anethum graveolens , antitumor, secondary metaabolites

Citation: El-Zehery HRA, Ashry NM, Faiesal AA, Attia MS, Abdel-Maksoud MA, El-Tayeb MA, Aufy M and El-Dougdoug NK (2024) Antibacterial and anticancer potential of bioactive compounds and secondary metabolites of endophytic fungi isolated from Anethum graveolens. Front. Microbiol. 15:1448191. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2024.1448191

Edited by:

Ahmed Abdelkhalek, City of Scientific Research and Technological Applications, EgyptReviewed by:

Malik Mobeen Ahmad, Integral University, IndiaPhatu William Mashela, University of Limpopo, South Africa

Arshad Javaid, University of the Punjab, Pakistan

Copyright © 2024 El-Zehery, Ashry, Faiesal, Attia, Abdel-Maksoud, El-Tayeb, Aufy and El-Dougdoug. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mohammed Aufy, bW9oYW1tZWQuYXVmeUB1bml2aWUuYWMuYXQ=

Hoda R. A. El-Zehery1

Hoda R. A. El-Zehery1 Mohamed S. Attia

Mohamed S. Attia Mostafa A. Abdel-Maksoud

Mostafa A. Abdel-Maksoud Mohamed A. El-Tayeb

Mohamed A. El-Tayeb Mohammed Aufy

Mohammed Aufy