94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Microbiol., 14 February 2024

Sec. Microorganisms in Vertebrate Digestive Systems

Volume 15 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2024.1365043

This article is part of the Research TopicThe Intricate Web of Gastrointestinal Virome, Mycome and Archaeome: Implications for Gastrointestinal DiseasesView all 5 articles

Hanjing Li1,2,3†

Hanjing Li1,2,3† Yingying Hu1,2,3†

Yingying Hu1,2,3† Yanyu Huang1,2,3

Yanyu Huang1,2,3 Shanshan Ding1,2,3

Shanshan Ding1,2,3 Long Zhu1,2,3

Long Zhu1,2,3 Xinghui Li1,2,3

Xinghui Li1,2,3 Meng Lan1,2,3

Meng Lan1,2,3 Weirong Huang4

Weirong Huang4 Xuejuan Lin1,2,3*

Xuejuan Lin1,2,3*Objectives: Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is a type of bacteria that infects the stomach lining, and it is a major cause of chronic gastritis (CG). H. pylori infection can influence the composition of the gastric microbiota. Additionally, alterations in the gut microbiome have been associated with various health conditions, including gastrointestinal disorders. The dysbiosis in gut microbiota of human is associated with the decreased secretion of gastric acid. Chronic atrophic gastritis (CAG) and H. pylori infection are also causes of reduced gastric acid secretion. However, the specific details of how H. pylori infection and CG, especially for CAG, influence the gut microbiome can vary and are still an area of ongoing investigation. The incidence of CAG and infection rate of H. pylori has obvious regional characteristics, and Fujian Province in China is a high incidence area of CAG as well as H. pylori infection. We aimed to characterize the microbial changes and find potential diagnostic markers associated with infection of H. pylori as well as CG of subjects in Jinjiang City, Fujian Province, China.

Participants: Enrollment involved sequencing the 16S rRNA gene in fecal samples from 176 cases, adhering to stringent inclusion and exclusion criteria. For our study, we included healthy volunteers (Normal), individuals with chronic non-atrophic gastritis (CNAG), and those with CAG from Fujian, China. The aim was to assess gut microbiome dysbiosis based on various histopathological features. QIIME and LEfSe analyses were performed. There were 176 cases, comprising 126 individuals who tested negative for H. pylori and 50 who tested positive defined by C14 urea breath tests and histopathological findings in biopsies obtained through endoscopy. CAG was also staged by applying OLGIM system.

Results: When merging the outcomes from 16S rRNA gene sequencing results, there were no notable variations in alpha diversity among the following groups: Normal, CNAG, and CAG; OLGIM I and OLGIM II; and H. pylori positive [Hp (+)] and H. pylori negative [Hp (–)] groups. Beta diversity among different groups show significant separation through the NMDS diagrams. LEfSe analyses confirmed 2, 3, and 6 bacterial species were in abundance in the Normal, CNAG, and CAG groups; 26 and 2 species in the OLGIM I and OLGIM II group; 22 significant phylotypes were identified in Hp (+) and Hp (–) group, 21 and 1, respectively; 9 bacterial species exhibited significant differences between individuals with CG who were Hp (+) and those who were Hp (–).

Conclusion: The study uncovered notable distinctions in the characteristics of gut microbiota among the following groups: Normal, CNAG, and CAG; OLGIM I and OLGIM II; and Hp (+) and Hp (–) groups. Through the analysis of H. pylori infection in CNAG and CAG groups, we found the gut microbiota characteristics of different group show significant difference because of H. pylori infection. Several bacterial genera could potentially serve as diagnostic markers for H. pylori infection and the progression of CG.

The gut microbiota comprises an intricate ecosystem teeming with tens of trillions of microorganisms (Lozupone et al., 2012; Sender et al., 2016). Throughout an individual's entire lifespan, the human gut microbiota participates in numerous interactions that impact the host's overall wellbeing (Milani et al., 2017). Disruption of gut microbiota homeostasis could correlate with alimentary tract injury (Chen et al., 2020), gastritis (Miao et al., 2022), and even gastric cancer (GC; Barra et al., 2021). The colonization of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) has a substantial impact on the gastric microenvironment, subsequently leading to alterations in the gastric microbiota (Chen et al., 2021). H. pylori infection is widely recognized for its links to gastroduodenal ulcer disease, chronic atrophic gastritis (CAG), GC, gastric intestinal metaplasia (GIM), and various other gastric and extragastric conditions (Watari et al., 2014; Fischbach and Malfertheiner, 2018). The interplay between H. pylori and the commensal flora in the gastrointestinal tract might contribute to H. pylori-related cancer risk and extragastric symptoms (Chen et al., 2021).

CAG is a type of gastritis, which is an inflammation of the stomach lining (Li et al., 2018). It is called “chronic” because it develops gradually over an extended period and “atrophic” because it is marked by the gradual depletion of gastric glandular cells, which are gradually replaced by fibrous tissue. One of the main causes of CAG is the presence of H. pylori infection (Holleczek et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2021; Zheng et al., 2023), which is a type of bacteria that can infect the stomach lining and cause chronic inflammation. Over time, as the inflammation persists, the gastric glands that produce hydrochloric acid and digestive enzymes start to deteriorate, leading to a reduction in the production of these essential substances (Neumann et al., 2013; Lahner et al., 2018). As a result, the stomach's ability to digest food and absorb certain nutrients, such as vitamin B12 and iron, is impaired. Subsequently, a range of gastrointestinal symptoms manifested, such as gas, upper abdominal discomfort, bloating, and changes in bowel movements. CAG can give rise to a range of health complications. Prolonged, persistent atrophic gastritis, particularly when linked with a chronic H. pylori infection, can elevate the likelihood of developing gastric (stomach) cancer (Karaman et al., 2008; Huang et al., 2023). But not everyone with CAG will experience noticeable symptoms, and in some cases, it may remain asymptomatic for an extended period (Liou et al., 2020). It is essential to manage CAG appropriately to prevent or minimize these potential morbidities.

It's encouraged for individuals with CAG to undergo regular screenings and monitoring for any signs of cancerous changes in the stomach lining. Diagnosing CAG usually involves a thorough assessment of the patient's medical history, blood tests, a physical examination to detect anemia or nutritional deficiencies, and endoscopy to visualize the stomach lining and collect biopsy samples for laboratory analysis (Shah et al., 2021). Diagnosing atrophic gastritis histopathologically continues to be challenging, characterized by limited agreement among different observers (Isajevs et al., 2014), and histopathological diagnosis is invasive. These all prompted us to find more convenient and accurate methods to find CAG patients. China exhibits a clear geographical clustering in the distribution of CAG and GC, with Fujian province standing out as a high-incidence area for this condition in the country (Li et al., 1996; Yang, 2006). The H. pylori infection is an important risk factor for CAG, affecting approximately half of the world's population, but the prevalence varies in different geographic regions (such as coastal, high altitude, and jungle; 1992; Yin et al., 2022; Malfertheiner et al., 2023). H. pylori infection is highly prevalent in coastal areas of China, such as Hainan and Shenzhen, with a high incidence rate among asymptomatic individuals (Li et al., 2022; Chen et al., 2023). Jinjiang City, located in the southeast of Fujian Province, China, is a typical coastal city, which has a certain representation of the population characteristics in coastal areas. This investigation employed 16S rRNA gene sequencing to investigate alterations in the ecological and composition aspects of gut microbiota for subjects from Jinjiang City, Fujian Province, aiming to understand their contributions to the transition from a healthy state to chronic non-atrophic gastritis (CNAG), followed by CAG, and their connection to H. pylori infection. To further identify potential diagnostic markers for H. pylori infection and the progression of chronic gastritis (CG).

This research enrolled 210 adult participants who had undergone a health assessment at the Spleen and Stomach Department and Health Management Center of Jinjiang Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine affiliated to Fujian University of Chinese Medicine, Jinjiang City, Fujian, China, between March 2021 to January 2022. The diagnosis of CAG (including OLGIM I and OLGIM II) and CNAG was evaluated by physicians based on a combination of endoscopic information and histopathological results. H. pylori positive [Hp (+)] and H. pylori negative [Hp (–)] was defined by C14 urea breath tests or biopsies. Healthy controls (Normal) had no self-report and physician diagnosis of past or current gastritis. Exclusion criteria encompassed individuals with a pacemaker, defibrillator, or other metallic implants; gastrointestinal tract obstruction; poor general condition; dysphagia or delayed gastric emptying; pregnancy. Out of these, we excluded 34 participants who refused to check H. pylori or received quadruple therapy for H. pylori eradication, including proton pump inhibitors (PPI) or antibiotic treatment. Finally, 176 subjects were analyzed (Figure 1).

This study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from the ethics committee of Jinjiang Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine, affiliated with Fujian University of Traditional Chinese Medicine Medical Ethics Committee (2019-016). We obtained written informed consent from all patients who participated.

C14 urea breath tests or biopsies obtained through endoscopy were used to diagnose H. pylori infection. C14 breath tests were subjected after more than 6 h-fasting. An H. pylori standard value exceeding 100 (dpm/mmol) indicated a positive outcome, while a negative outcome corresponded to a range of 0–100 (dpm/mmol). In most instances, the antrum served as the primary site for biopsy to detect H. pylori infection. Nevertheless, in order to mitigate the potential for false negative outcomes in individuals with intestinal metaplasia (IM) or antral atrophy, a biopsy from the corpus at the greater curve was utilized. Additionally, H. pylori infection was diagnosed in real-time during the endoscopic examination.

Characteristic endoscopic signs of atrophic gastritis consist of a pale appearance of the gastric mucosa, enhanced visibility of vasculature due to mucosal thinning, and the absence of gastric folds. In cases where light blue crests and white opaque fields were present, a concurrent diagnosis of intestinal metaplasia might be established. According to the Sydney System (Dixon et al., 1996), two endoscopists with more than 5 years' experience in gastroscopy performed five biopsies: two antral and two corpus, a fifth or more biopsy specimens from the incisura as a supplement. Biopsy samples from the three regions were individually distinguishable upon submission to the laboratory. Both a general and a specialist gastrointestinal pathologist evaluated and graded the biopsy specimens using Sydney classification, and the gastritis stage was evaluated based on the OLGIM system. Combined endoscopic information with histopathology, subjects were divided into CNAG, and CAG. In the OLGIM staging system, the evaluation of IM followed a similar scoring approach to that of OLGA. However, instead of the atrophy score, it was replaced with an IM score (based on the presence of IM; Capelle et al., 2010). We then categorized the subjects into OLGIM I and OLGIM II groups.

Each participant collected 2–3 g of fecal samples in commercial containers (Sorfa Life Science Research Co., Ltd., Zhejiang, China) and suspended in GUHE Flora Storage buffer (Zhejiang Hangzhou Equipment Preparation 20190682, GUHE Laboratories, Hangzhou, China). Preserved the collected samples at −80°C before the procedure of DNA extraction, and all samples were maintained under identical storage conditions.

The GHFDE100 DNA isolation kit (Zhejiang Hangzhou Equipment Preparation 20190952) was used to obtain genomic DNA from bacteria. The extraction procedure adhered to the guidelines of manufacturer. Agarose gel electrophoresis and NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) were used to ensure the quality and quantity of the obtained DNA.

The V4 region of bacterial 16S rRNA genes were amplified via PCR, employing the forward primer 515F (5′-GTGCCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA-3′) and the reverse primer 806R (5′-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′). The PCR amplicons were subsequently purified with Agencourt AMPure XP Beads from Beckman Coulter, Indianapolis, IN, and their quantification was determined using the PicoGreen dsDNA Assay Kit from Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA. After quantifying each amplicon individually, they were mixed in equal proportions and then underwent pair-end 2 × 150 bp sequencing on the Illumina NovaSeq6000 platform at GUHE Info Technology Co., Ltd in Hangzhou, China. We employed the following criteria to filter out low-quality sequences (Gill et al., 2006): sequences shorter than 150 base pairs, sequences with mononucleotide repeats longer than 8 base pairs, sequences with an average Phred score below 20, and sequences containing ambiguous bases were all excluded. The paired-end reads were merged using Vsearch V2.4.4 (-fastq_mergepairs–fastq_minovlen 5), and then operational taxonomic units (OTUs) were determined using Vsearch v2.15.0. The taxonomic classification of the OTU was conducted (Quast et al., 2013) and an OTU table was created to document the abundance of each OTU in every sample, along with their taxonomic assignments. Eliminating OTUs representing <0.01‰ of the total sequences. To ensure uniform sequencing depth across samples, we generated an OTU table by computing the averages of 100 evenly resampled OTU subsets. Each subset was resampled to meet 90% of the minimum sequencing depth.

QIIME2 was used to analyze the microbiome sequence data. OTUs were constructed using a >97% similarity threshold to the 16S rRNA representative sequence provided in the Green Genes Database v13.8.0. Alpha diversity, beta diversity and LEfSe analyses were performed.

We used SPSS 26.0 to analyze clinical data. Categorical variables were presented as percentages and frequencies. Continuous variables were presented using either the mean and standard deviation or the median and interquartile range. We utilized the chi-square test for categorical variables and Student's t-test for continuous variables. One-way ANOVA was applied for two or more groups' comparison. Between-group effects were tested pairwise (two-tailed t-tests, alpha = 0.05). P < 0.05 was considered as a significance level.

One hundred and seventy-six subjects included 23 healthy volunteers (normal), 48 CNAG patients, and 105 CAG patients. Of all the patients with CAG, 52 subjects were classified as OLGIM I and 53 OLGIM II. A combined 126 subjects were Hp (–), while 50 Hp (+). By comparing general features of the 176 participates, we found the age of subjects increased from group normal, CNAG to CAG, and the disparity was statistically noteworthy (P < 0.01; Table 1). Comparing the occupations of participants in group OLGIM I with OLGIM II and group Hp (+) with Hp (–), it was observed that there were more farmers in group OLGIM II and Hp (+) (P < 0.05; Tables 2, 3). No significant distinctions were observed among the subjects of lifestyle including smoking and drinking (P > 0.05; Tables 1–3).

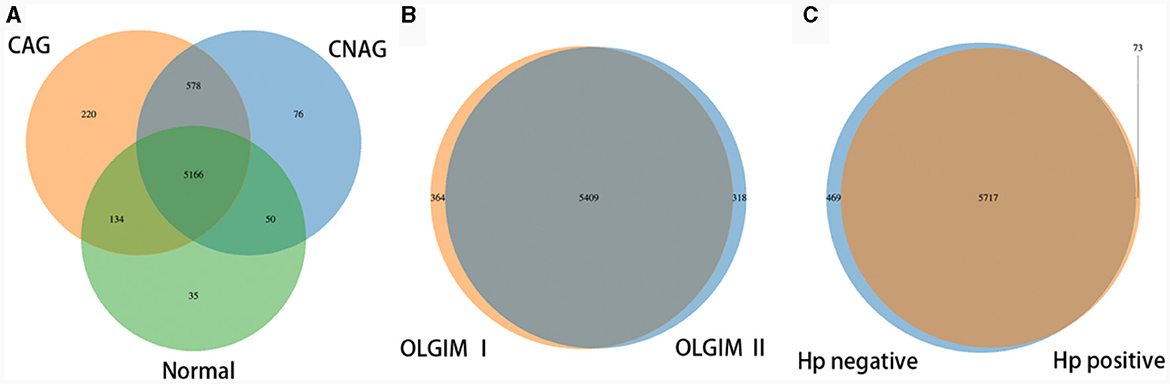

To profile the gut microbiota linked to the Normal, CNAG, and CAG groups, we conducted 16S rRNA gene sequencing on 176 fecal samples. From the three groups, we identified a total of 5,385, 5,870, and 6,098 OTUs (97% similarity), respectively (Figure 2A). A heatmap was generated to illustrate the top 30 genera within each group (Figure 3). For 105 fecal samples, 5,773 and 5,727 OTUs (97% similarity) were obtained from OLGIM I and OLGIM II group (Figure 2B). The top 60 genera within each group were described in a heat map (Figure 4). Of all the 176 fecal samples, 5,790 and 6,186 OTUs (97% similarity) were obtained from Hp (+) and Hp (–) group (Figure 2C).

Figure 2. Venn map. (A) The Venn map of the OTUs distribution of group Normal, CNAG, and CAG. (B) The Venn map of the OTUs distribution of group OLGIM I and OLGIM II. (C) The Venn map of the OTUs distribution of group H. pylori positive and H. pylori negative.

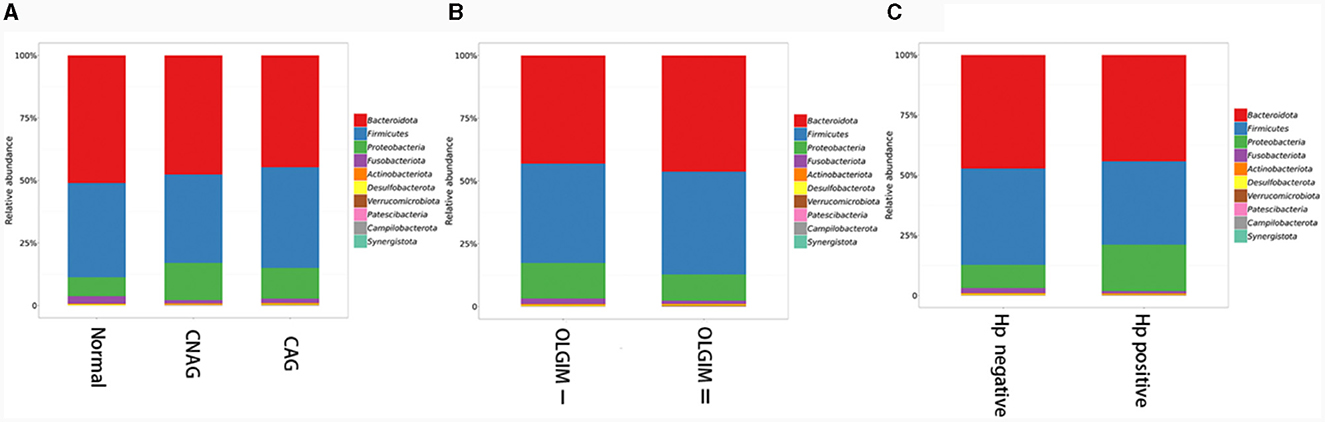

Furthermore, the three predominant bacterial phyla in each group consisted of Bacteroidota, Firmicutes, and Proteobacteria (Figures 5A–C), the top three genera in each group are Bacteroides, Prevotella, and Faecalibacterium (Supplementary Tables 1–3).

Figure 5. The predominant bacterial phylum distribution composition of each group. (A) The predominant bacterial phyla in group Normal, CNAG, and CAG. (B) The predominant bacterial phyla in group OLGIM I and OLGIM II. (C) The predominant bacterial phyla in group H. pylori positive and H. pylori negative.

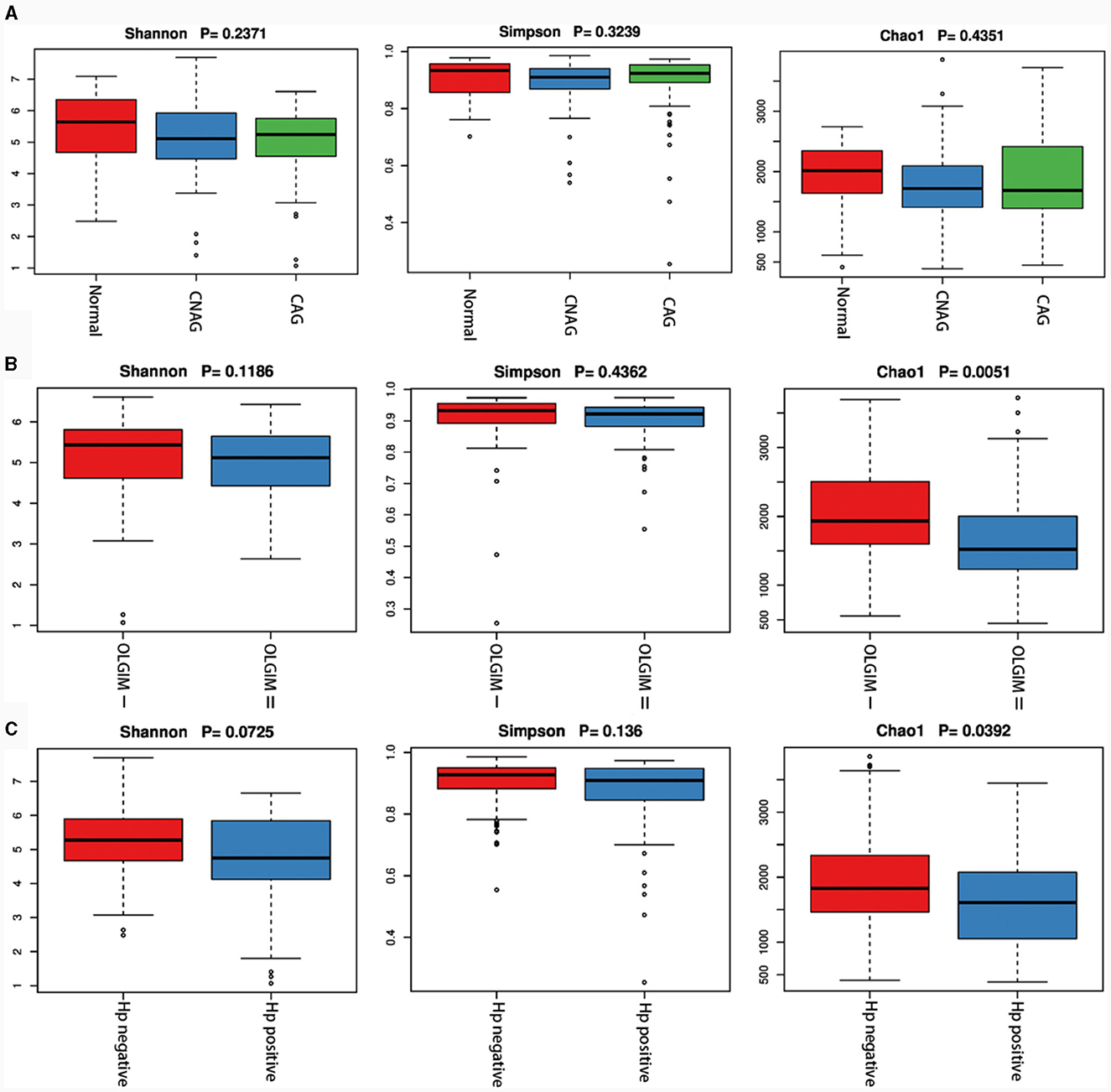

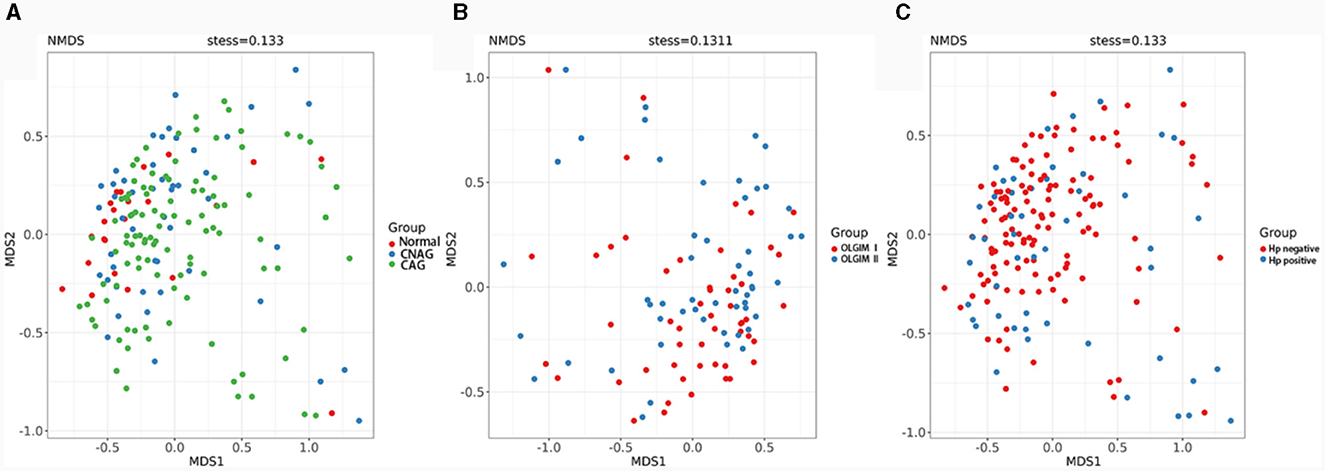

We utilized both alpha and beta diversity measures to evaluate gut microbiota dysbiosis across the various groups. Alpha diversity was assessed using community diversity (Simpson indexes and Shannon indexes) and community richness (Chao1 indexes). The Shannon and Simpson indexes of group Normal, CNAG and CAG, group OLGIM I and OLGIM II, group Hp (+) and Hp (–) show no significant differences. Chao1 indexes exhibited a significant decrease in group OLGIM II and group Hp (+) (P < 0.05; Figures 6A–C). Non-metric Multidimensional Scaling (NMDS) analyses were carried out to assess beta diversity, allowing us to quantify the dissimilarity in gut microbial composition. The NMDS plots revealed substantial differentiation in the intestinal microbiome across the distinct groups (Figures 7A–C).

Figure 6. Characteristics of the gut microbiota alpha diversity among each group. (A) Characteristics of the gut microbiota alpha diversity among group Normal, CNAG, and CAG. (B) Characteristics of the gut microbiota alpha diversity between group OLGIM I and OLGIM II. (C) Characteristics of the gut microbiota alpha diversity between group H. pylori positive and H. pylori negative.

Figure 7. Comparison of the microbiota beta diversity among each group. (A) The microbiota beta diversity of group Normal, CNAG, and CAG. (B) The microbiota beta diversity of group OLGIM I and OLGIM II. (C) The microbiota beta diversity of group H. pylori positive and H. pylori negative.

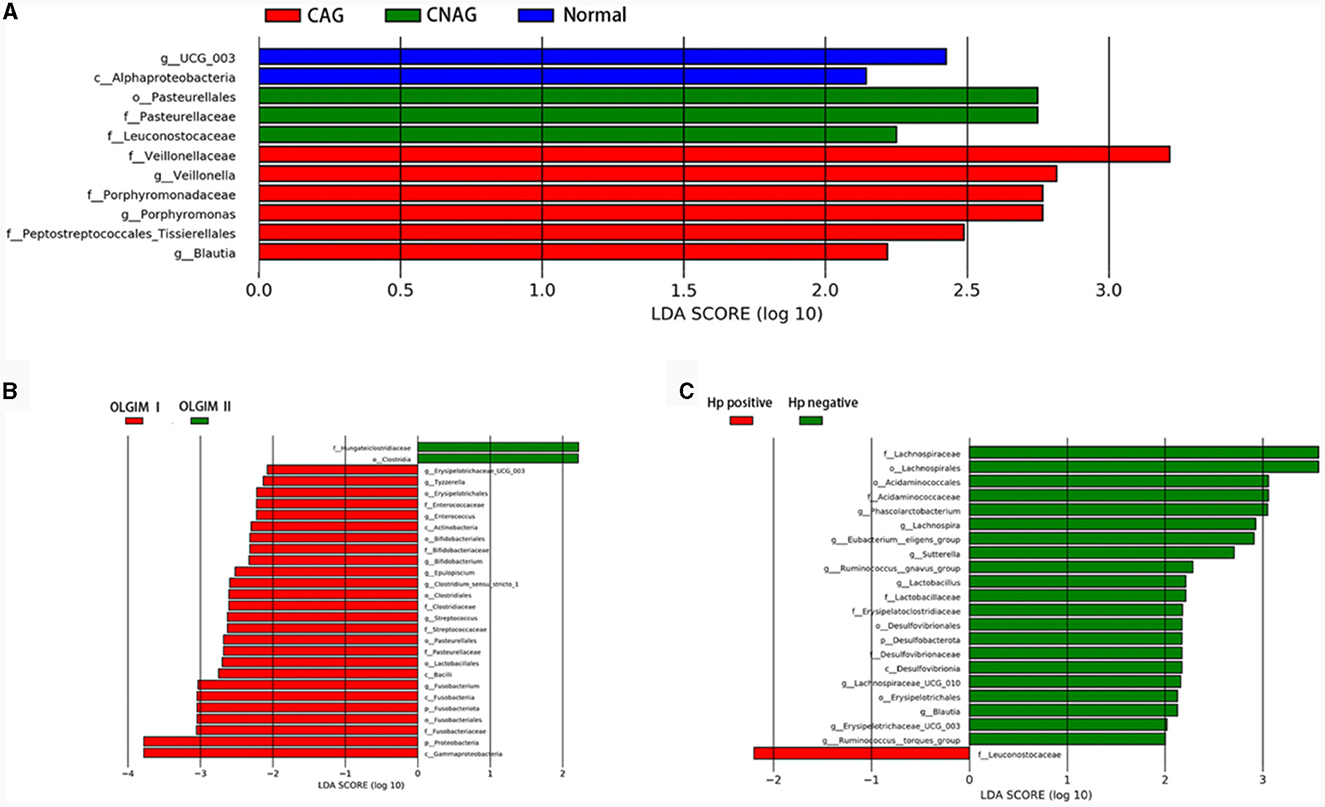

To validate the distinctions in microbial communities, we conducted LEfSe analyses, leveraging Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) to pinpoint bacteria that displayed significant abundance variations across various groups (LDA score >2.0 with P < 0.05). The length of each bar in the chart indicated the extent of influence of various species (LDA Score), signifying the impact of significantly differing species between the various groups (Figures 8A–C).

Figure 8. Comparing the distributions of the gut microbiota composition among each group. (A) Histogram of LDA value distribution represents the magnitude of the impact of different species among group Normal, CNAG, and CAG. (B) Histogram of LDA value distribution represents the magnitude of the impact of different species among group OLGIM I and OLGIM II. (C) Histogram of LDA value distribution represents the magnitude of the impact of different species among group H. pylori positive and H. pylori negative.

In total, 11 significant phylotypes were recognized, with 2, 3, and 6 bacterial species predominantly present in the Normal, CNAG, and CAG groups, respectively. At the genus level, Oscillospiraceae_UCG_003 (P = 0.041) exhibited significant enrichment in the Normal group, Veillonella (P = 0.025), Porphyromonas (P = 0.044), Blautia (P = 0.005) exhibited significant enrichment in the CAG group.

In the OLGIM I and OLGIM II groups, there were 26 and 2 species of bacteria that were predominant, respectively. At the genus level, Erysipelotrichaceae_UCG_003 (P = 0.036), Tyzzerella (P = 0.042), Enterococcus (P = 0.015), Bifidobacterium (P = 0.023), Epulopiscium (P = 0.019), Clostridium_sensu_stricto_1 (P = 0.030), Streptococcus (P = 0.006), Fusobacterium (P = 0.030) showed a significant enrichment in the OLGIM I group.

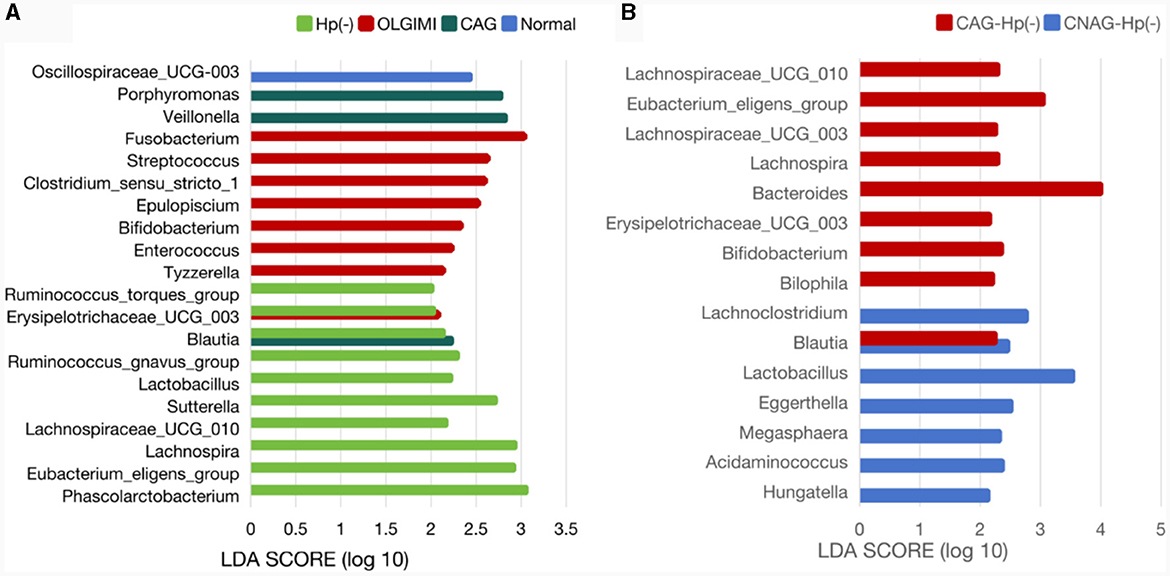

Twenty-two significant phylotypes were identified in Hp (+) and Hp (–) group, 21 and 1, respectively. At the genus level, Phascolarctobacterium (P = 0.020), Eubacterium_eligens_group (P = 0.018), Lachnospira (P = 0.004), Lachnospiraceae_UCG_010 (P = 0.040), Sutterella (P = 0.030), Lactobacillus (P = 0.032), Ruminococcus_gnavus_group (P = 0.049), Blautia (P = 0.003), Erysipelotrichaceae_UCG_003 (P = 0.024), Ruminococcus_torques_group (P = 0.042) showed a significant enrichment in the Hp (–) group (Figure 9A).

Figure 9. Comparison of the significantly enriched genera in each group. (A) The histogram of LDA values represents the impact level of significantly enriched genera in the Normal, CAG, OLGIM I, and Hp (-) group. (B) Histogram of LDA value distribution represents the impact level of significantly enriched genera in the CNAG-Hp (-) and CAG-Hp (-) group.

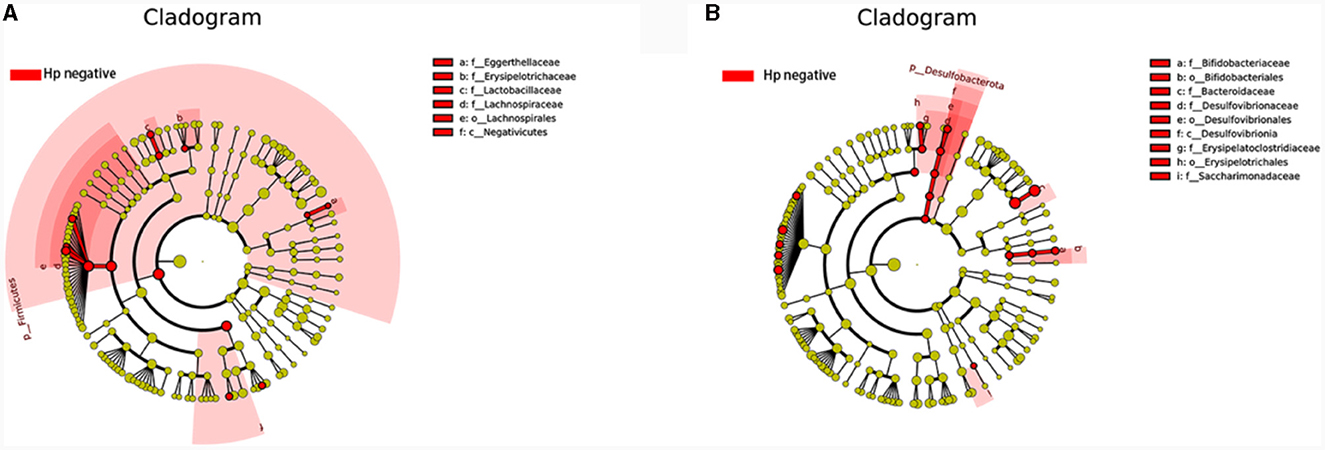

Trough LEfSe analyses, nine species of bacteria were significantly differed between the CNAG and CAG group. In order to explore the connections between gut microbiota and H. pylori infection in all subjects with CG, we examined the gut microbiota of individuals with CNAG and CAG, categorizing them into Hp (+) and Hp (–) groups. To be specific, the abundances of Hungatella (P = 0.0003), Acidaminococcus (P = 0.0148), Megasphaera (P = 0.0066), Eggerthella (P = 0.0288), Lactobacillus (P = 0.0202), Blautia (P = 0.0490), and Lachnoclostridium (P = 0.0304) were notably greater in the Hp (–) group as opposed to the Hp (+) group among CNAG subjects (Figure 10A). The abundances of Bilophila (P = 0.0089), Bifidobacterium (P = 0.0371), Blautia (P = 0.0040), Erysipelotrichaceae_UCG_003 (P = 0.0215), Bacteroides (P = 0.0304), Lachnospira (P = 0.0082), Lachnospiraceae_UCG_003 (P = 0.0281), Eubacterium_eligens_group (P = 0.0077), and Lachnospiraceae_UCG_010 (P = 0.0293) exhibited a marked increase in the Hp (–) group as opposed to the Hp (+) group among CAG subjects (Figures 9B, 10B).

Figure 10. Comparing the distributions of the gut microbiota structure among each group. (A) The cladogram illustrates the phylogenetic distribution of microbial lineages between group H. pylori positive and H. pylori negative among CNAG subjects. (B) The cladogram illustrates the phylogenetic distribution of microbial lineages between group H. pylori positive and H. pylori negative among CAG subjects.

Considering that antibiotic and PPI treatments may exacerbate disturbances in the gut microbiota, we excluded 34 subjects who were undergoing medication treatment and those who refused H. pylori examination. In the end, 16S rRNA gene sequencing of feces samples were performed for 176 subjects to determine the characteristics of gut microbiota for Normal, CNAG, and CAG subjects. As well as characteristics of gut microbiota for Hp (+) and Hp (–) group. Through histological stages of CAG, the gut microbiota characteristics of OLGIM I and OLGIM II were also described.

Through basic information comparison of participants in each group, it was found that the age of participants gradually increased from the Normal group to the CNAG group and then to the CAG group. This aligns with the common understanding that the incidence of CAG tends to increase with age (Adamu et al., 2010; Chen Z. et al., 2022). When comparing the occupations between group OLGIM I and group OLGIM II, as well as group Hp (+) and Hp (–) separately, we observed that there was a higher proportion of participants engaged in agriculture in group OLGIM II and group Hp (+). This suggests that engaging in agricultural activities is associated with a higher degree of the OLGIM staging and H. pylori infection, which aligns with relevant research results regarding the impact of occupation on the incidence of CAG (Chen Z. et al., 2022). Smoking and alcohol consumption, identified as risk factors for the onset and progression of CG, showed no significant differences in the comparisons among groups in this study, possibly due to the sample size.

The sequencing results of feces samples indicate that, despite no differences in community diversity, there is a significant decrease in community richness in OLGIM II and Hp (+) group. Through NMDS analysis, the stress values for each group were all < 0.2. Which means the results of the NMDS analysis have a certain level of interpretative significance, indicating that beta diversity analyses reveal a noteworthy segregation of gut microbiota among distinct groups.

The genus Oscillospiraceae_UCG_003 was only significantly enriched in the Normal group, and decreased in other disease like depression (Liang et al., 2022), suggesting that it may be a beneficial bacterial genus for health. Of all the bacterial significantly enriched in Hp (–) group, Phascolarctobacterium, Eubacterium_eligens_group, and Lachnospira were the top three genera with the highest extent of influence on the group. Phascolarctobacterium and Eubacterium_eligens_group also showed significant impact on the group Hp (–) group among CAG subjects. Lactobacillus was significantly enriched in both the Hp (–) group and CNAG-Hp (–) group, demonstrating a strong extent of influence. Based on the evidence presented, we could assume that these three genera Eubacterium_eligens_group, Lachnospira, and Lactobacillus might be potentially protective bacterial genera against H. pylori infection. Eubacterium_eligens_group were also discovered to have a protective effect on other diseases like scoliosis (Lai et al., 2023) and type 1 diabetes (Luo et al., 2023). Lachnospiraceae constitute an integral part of the gut microbiota's core, characterized by their diversity of species and consistent relative abundance throughout the host's lifespan. Lachnospira belong to the Lachnospiraceae family and are known for being primary contributors to short-chain fatty acid production. Patients experiencing active ulcerative colitis and exhibiting depression and anxiety tend to have lower richness in genus Lachnospira (Yuan X. et al., 2021). Zhang et al. (2022) found that Lachnospira were significantly reduced in type 2 diabetes and diabetic nephropathy patients. As a kind of potential probiotics, Lachnospira showed a protective effect against H. pylori infection in this study. Lactobacillus is widely present in the environment, food, and various parts of the human body, constituting a bacterial genus that rarely causes opportunistic infections in the human body (O'Callaghan and O'Toole, 2013). Several species of Lactobacillus are commonly employed as probiotics, contributing to the wellbeing of the host when administered in sufficient quantities (Yang et al., 2018). Considering the beneficial effects of these three bacterial genera on health and the demonstrated significant extent of influence on groups which related with negative H. pylori infection status to a considerable degree of our study, an increase in bacterial abundance of genera Eubacterium_eligens_group, Lachnospira, and Lactobacillus might serve as a negative indicator for diagnosing H. pylori infection. The abundance of bacterial Bifidobacterium was enriched in the OLGIM I group and the CAG-Hp (–) group, which means the gut microbiota characteristics of bacterial Bifidobacterium enrichment could be linked to the occurrence of H. pylori negative CAG (especially for OLGIM I). Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus are two types of probiotics which have been suggested as adjuncts to antibiotics to address H. pylori (Boltin, 2016). Though didn't found to be enriched in Normal group, these two genera were corelated with H. pylori negative in this study. These evidences also show the negative correlation between H. pylori infection and two probiotics Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus.

Veillonella and Porphyromonas exhibited significant enrichment in the CAG group and Fusobacterium in OLGIM I group. Veillonella species are commonly found in the oral microbiota and have been repeatedly reported to be associated with inflammatory conditions in the oral cavity (Luo et al., 2020; Yuan H. et al., 2021; Giacomini et al., 2023; Kumar et al., 2023). In certain pathological conditions, oral bacteria Veillonella can ectopically colonize in the intestine (Rojas-Tapias et al., 2022). Liu et al. (2022) found that the relative abundance of Veillonella was richer in the GIM group than in the chronic superficial gastritis group. Hua et al. (2023) observed that H. pylori infection reduced the abundances of several predominant oral bacteria in patients with CAG. Additionally, bile reflux markedly facilitated the colonization of dominant oral microbiota, particularly Veillonella, in the stomach of CAG patients. The increase in Veillonella abundance may serve as one of the indicators for CAG and GIM. Research show that the abundance of Porphyromonas in gastritis samples were increased (Chen M. et al., 2022). The abundance of Porphyromonas showed a correlation with histological gastritis, but not with endoscopic or symptomatic gastritis (Han et al., 2019). Through testing the variations in Porphyromonas abundance may enhance the accuracy of diagnosing gastritis through endoscopy or symptoms. The genus Fusobacterium has been found to be closely associated with gastrointestinal diseases. Li's team discovered that, compared to gastritis, the genus Fusobacterium is frequently and significantly enriched in GC patients, demonstrating a strong ability to distinguish between GC samples and gastritis (Li et al., 2023). This suggests that the abundance of the genus Fusobacterium may be associated with the progression of GIM and CAG. The strong coexcluding interactions between H. pylori and Fusobacterium might be one reason we didn't observed the richness of Fusobacterium in Hp (+) group, which has been proved by Gou's team (Guo et al., 2020).

Bacterial genus Blautia was significantly enriched in group CAG and group Hp (–), as well as in group CNAG-Hp (–) and group CAG-Hp (–). Blautia represents a genus of anaerobic bacteria recognized for its probiotic attributes (Liu et al., 2021). Recent researches have demonstrated that variations in the composition and levels of Blautia in the gut play a beneficial role in countering colorectal cancer (Ni et al., 2022), depressive disorder (Zhuang et al., 2020), type 2 diabetes and obesity (Hosomi et al., 2022). Zhou et al. (2020) observed that the bacterial Blautia decreased in gastritis subjects. Huang et al.'s (2022) team found that the abundance of bacteria Blautia decreased in CAG patients. These studies have shown the beneficial effects of the bacteria on health. Indeed, the presence of Blautia in the gut microbiome is influenced by factors such as host age, geographic location, dietary habits, genotype, health, disease status, and various physiological conditions. Notably, this genus comprises 20 newly discovered species with officially recognized names (Nakayama et al., 2015; Odamaki et al., 2016; Mao et al., 2018). In our research, Blautia exhibited notable enrichment in four groups. The dominance of a specific Blautia species remains uncertain, indicating that it may not be suitable as a diagnostic marker of CAG.

Helicobacter pylori infection, CG, and the composition of the gut microbiota mutually influences each other. The changes in the abundance of gut bacterial genera could reflect H. pylori infection and the progression of CG of subjects. For these reasons, learn more about the relationship of significant characteristics of gut microbiota for healthy individuals, CNAG, and CAG (regardless of the etiology, the diagnosis of atrophic gastritis OLGIM I and OLGIM II was confirmed by histopathology) subjects, as well as infection of H. pylori at different stage of the disease, might let us learn more about the disease and further identify diagnosis and treatment. Through our research, we have observed that several gut bacterial genera could potentially serve as diagnostic markers for H. pylori infection and the progression of CG. This may offer a pathway for gut microbiota detection to reduce the potential incidence of CAG and H. pylori infection. However, our study was conducted in a specific region with limited samples, reflecting characteristics of populations in areas with a high prevalence of CAG and H. pylori infection, such as Jinjiang City in Fujian Province, China, and similar coastal regions. Further research is needed to uncover universal characteristics in populations.

We found the gut microbiota characteristics of healthy, CNAG, and CAG subjects have a significant difference, and age of subjects increased from Normal, CNAG to CAG group. There were more farmers in OLGIM II and Hp (+) group. Also, the gut microbiota characteristics of group OLGIM I and OLGIM II, group Hp (+) and Hp (–) show significant differences. Through the analysis of H. pylori infection in CNAG and CAG groups, we found the gut microbiota characteristics of different group show significant difference because of H. pylori infection. Several bacterial genera showed a significant extent of influence on corresponding group and could be potential diagnostic markers for H. pylori infection and the progression of CG. These discoveries may enhance our comprehension of CG, H. pylori infection, and gut microbiota. However, to obtain more universally applicable characteristics of the gut microbiota in populations related to gastritis, further research is necessary.

The datasets presented in this study are deposited in the NCBI repository under accession number PRJNA1072256 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/PRJNA1072256).

The studies involving humans were approved by Jinjiang Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine, affiliated with Fujian University of Traditional Chinese Medicine Medical Ethics Committee. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

HL: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft. YHu: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft. YHua: Investigation, Resources, Software, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. SD: Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. LZ: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. XLi: Project administration, Resources, Validation, Writing – review & editing. ML: Resources, Software, Validation, Writing – review & editing. WH: Data curation, Resources, Validation, Writing – review & editing. XLin: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was funded by Funds of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81973752).

We appreciated all the medical staff involved in the study.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2024.1365043/full#supplementary-material

(1992). Ecology of Helicobacter pylori in Peru: infection rates in coastal, high altitude, and jungle communities. The Gastrointestinal Physiology Working Group of the Cayetano Heredia and the Johns Hopkins University. Gut 33, 604–605. doi: 10.1136/gut.33.5.604

Adamu, M. A., Weck, M. N., Gao, L., and Brenner, H. (2010). Incidence of chronic atrophic gastritis: systematic review and meta-analysis of follow-up studies. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 25, 439–448. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9482-0

Barra, W. F., Sarquis, D. P., Khayat, A. S., Khayat, B. C. M., Demachki, S., Anaissi, A. K. M., et al. (2021). Gastric cancer microbiome. Pathobiology 88, 156–169. doi: 10.1159/000512833

Boltin, D. (2016). Probiotics in Helicobacter pylori-induced peptic ulcer disease. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 30, 99–109. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2015.12.003

Capelle, L. G., de Vries, A. C., Haringsma, J., Ter Borg, F., de Vries, R. A., Bruno, M. J., et al. (2010). The staging of gastritis with the OLGA system by using intestinal metaplasia as an accurate alternative for atrophic gastritis. Gastrointest. Endosc. 71, 1150–1158. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.12.029

Chen, C. C., Liou, J. M., Lee, Y. C., Hong, T. C., El-Omar, E. M., Wu, M. S., et al. (2021). The interplay between Helicobacter pylori and gastrointestinal microbiota. Gut Microbes 13, 1–22. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2021.1909459

Chen, M., Fan, H.-N., Chen, X.-Y., Yi, Y.-C., Zhang, J., and Zhu, J.-S. (2022). Alterations in the saliva microbiome in patients with gastritis and small bowel inflammation. Microb. Pathog. 165:105491. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2022.105491

Chen, R.-X., Zhang, D.-Y., Zhang, X., Chen, S., Huang, S., Chen, C., et al. (2023). A survey on Helicobacter pylori infection rate in Hainan Province and analysis of related risk factors. BMC Gastroenterol. 23:338. doi: 10.1186/s12876-023-02973-3

Chen, Y., Wu, G., and Zhao, Y. (2020). Gut microbiota and alimentary tract injury. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1238:11–22. doi: 10.1007/978-981-15-2385-4_2

Chen, Z., Zheng, Y., Fan, P., Li, M., Liu, W., Yuan, H., et al. (2022). Risk factors in the development of gastric adenocarcinoma in the general population: a cross-sectional study of the Wuwei Cohort. Front. Microbiol. 13:1024155. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.1024155

Dixon, M. F., Genta, R. M., Yardley, J. H., et al. (1996). Classification and grading of gastritis. The updated Sydney System. International Workshop on the Histopathology of Gastritis, Houston 1994. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 20, 1161–1181. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199610000-00001

Fischbach, W., and Malfertheiner, P. (2018). Helicobacter pylori infection. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 115, 429–436. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2018.0429

Giacomini, J. J., Torres-Morales, J., Dewhirst, F. E., and Irwin, R. E. (2023). Site specialization of human oral veillonella species. Microbiol. Spectr. 11:e0404222. doi: 10.1128/spectrum.04042-22

Gill, S. R., Pop, M., Deboy, R. T., Eckburg, P. B., Turnbaugh, P. J., Samuel, B. S., et al. (2006). Metagenomic analysis of the human distal gut microbiome. Science 312, 1355–1359. doi: 10.1126/science.1124234

Guo, Y., Zhang, Y., Gerhard, M., Gao, J.-J., Mejias-Luque, R., Zhang, L., et al. (2020). Effect of Helicobacter pylori on gastrointestinal microbiota: a population-based study in Linqu, a high-risk area of gastric cancer. Gut 69, 1598–1607. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-319696

Han, H. S., Lee, S.-Y., Oh, S. Y., Moon, H. W., Cho, H., and Kim, J.-H. (2019). Correlations of the gastric and duodenal microbiota with histological, endoscopic, and symptomatic gastritis. J. Clin. Med. 8:312 doi: 10.3390/jcm8030312

Holleczek, B., Schöttker, B., and Brenner, H. (2020). Helicobacter pylori infection, chronic atrophic gastritis and risk of stomach and esophagus cancer: results from the prospective population-based ESTHER cohort study. Int. J. Cancer 146, 2773–2783. doi: 10.1002/ijc.32610

Hosomi, K., Saito, M., Park, J., Murakami, H., Shibata, N., Ando, M., et al. (2022). Oral administration of Blautia wexlerae ameliorates obesity and type 2 diabetes via metabolic remodeling of the gut microbiota. Nat. Commun. 13:4477. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-32015-7

Hua, Z., Xu, L., Zhu, J., Xiao, L., Lu, B., Wu, J., et al. (2023). Helicobacter pylori infection altered gastric microbiota in patients with chronic gastritis. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 13:1221433. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2023.1221433

Huang, R. J., Laszkowska, M., In, H., Hwang, J. H., and Epplein, M. (2023). Controlling gastric cancer in a world of heterogeneous risk. Gastroenterology 164, 736–751. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2023.01.018

Huang, W., Yau, Y., Zhu, J., Wang, Y., Dai, Z., Gan, H., et al. (2022). Effect of electroacupuncture at zusanli (ST36) on intestinal microbiota in rats with chronic atrophic gastritis. Front. Genet. 13:824739. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2022.824739

Isajevs, S., Liepniece-Karele, I., Janciauskas, D., Moisejevs, G., Putnins, V., Funka, K., et al. (2014). Gastritis staging: interobserver agreement by applying OLGA and OLGIM systems. Virchows Arch. 464, 403–407. doi: 10.1007/s00428-014-1544-3

Karaman, A., Binici, D. N., Kabalar, M. E., Dursun, H., and Kurt, A. (2008). Alteration of sister chromatid exchange frequencies in gastric cancer and chronic atrophic gastritis patients with and without H. pylori infection. World J. Gastroenterol. 14, 2534–2539. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.2534

Kumar, P., Kumaresan, M., Biswas, R., and Saxena, S. K. (2023). Veillonella atypica causing retropharyngeal abscess: a rare case presentation. Anaerobe 81:102712. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2023.102712

Lahner, E., Carabotti, M., and Annibale, B. (2018). Treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection in atrophic gastritis. World J. Gastroenterol. 24, 2373–2380. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i22.2373

Lai, B., Jiang, H., Gao, Y., and Zhou, X. (2023). Causal effects of gut microbiota on scoliosis: a bidirectional two-sample mendelian randomization study. Heliyon 9:e21654. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e21654

Li, C., Yue, J., Ding, Z., Zhang, Q., Xu, Y., Wei, Q., et al. (2022). Prevalence and predictors of Helicobacter pylori infection in asymptomatic individuals: a hospital-based cross-sectional study in Shenzhen, China. Postgrad. Med. 134, 686–692. doi: 10.1080/00325481.2022.2085950

Li, L., Lu, F., and Zhang, S. (1996). [Analysis of cancer modality and distribution in China from year 1990 through 1992–an epidemiologic study]. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi 18, 403–407.

Li, Y., Hu, Y., Zhan, X., Song, Y., Xu, M., Wang, S., et al. (2023). Meta-analysis reveals Helicobacter pylori mutual exclusivity and reproducible gastric microbiome alterations during gastric carcinoma progression. Gut Microbes 15:2197835. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2023.2197835

Li, Y., Xia, R., Zhang, B., et al. (2018). Chronic atrophic gastritis: a review. J. Environ. Pathol. Toxicol. Oncol. 37, 241–259. doi: 10.1615/JEnvironPatholToxicolOncol.2018026839

Liang, S., Sin, Z. Y., Yu, J., Zhao, S., Xi, Z., Bruzzone, R., et al. (2022). Multi-cohort analysis of depression-associated gut bacteria sheds insight on bacterial biomarkers across populations. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 80:9. doi: 10.1007/s00018-022-04650-2

Liou, J.-M., Malfertheiner, P., Lee, Y.-C., Sheu, B.-S., Sugano, K., Cheng, H.-C., et al. (2020). Screening and eradication of Helicobacter pylori for gastric cancer prevention: the Taipei global consensus. Gut 69, 2093–2112. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-322368

Liu, X., Mao, B., Gu, J., Wu, J., Cui, S., Wang, G., et al. (2021). Blautia-a new functional genus with potential probiotic properties? Gut Microbes 13, 1–21. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2021.1875796

Liu, Y., Ma, Y. J., and Huang, C. Q. (2022). Evaluation of the gastric microbiome in patients with chronic superficial gastritis and intestinal metaplasia. Chin. Med. Sci. J. 37, 44–51. doi: 10.24920/003889

Lozupone, C. A., Stombaugh, J. I., Gordon, J. I., Jansson, J. K., and Knight, R. (2012). Diversity, stability and resilience of the human gut microbiota. Nature 489, 220–230. doi: 10.1038/nature11550

Luo, M., Sun, M., Wang, T., Zhang, S., Song, X., Liu, X., et al. (2023). Gut microbiota and type 1 diabetes: a two-sample bidirectional Mendelian randomization study. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 13:1163898. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2023.1163898

Luo, Y. X., Sun, M. L., Shi, P. L., Liu, P., Chen, Y. Y, and Peng, X. (2020). [Research progress in the relationship between Veillonella and oral diseases]. Hua Xi Kou Qiang Yi Xue Za Zhi 38, 576–582. doi: 10.7518/hxkq.2020.05.018

Malfertheiner, P., Camargo, M. C., El-Omar, E., Liou, J. M., Peek, R., Schulz, C., et al. (2023). Helicobacter pylori infection. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 9:19. doi: 10.1038/s41572-023-00431-8

Mao, B., Gu, J., Li, D., Cui, S., Zhao, J., and Zhang, H. (2018). Effects of different doses of fructooligosaccharides (FOS) on the composition of mice fecal microbiota, especially the bifidobacterium composition. Nutrients 10:1105. doi: 10.3390/nu10081105

Miao, Y., Tang, H., Zhai, Q., Liu, L., Xia, L., Wu, W., et al. (2022). Gut microbiota dysbiosis in the development and progression of gastric cancer. J. Oncol. 2022:9971619. doi: 10.1155/2022/9971619

Milani, C., Duranti, S., Bottacini, F., Casey, E., Turroni, F., Mahony, J., et al. (2017). The first microbial colonizers of the human gut: composition, activities, and health implications of the infant gut microbiota. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 81:e00036-17. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00036-17

Nakayama, J., Watanabe, K., Jiang, J., Matsuda, K., Chao, S. H., Haryono, P., et al. (2015). Diversity in gut bacterial community of school-age children in Asia. Sci. Rep. 5:8397. doi: 10.1038/srep08397

Neumann, W. L., Coss, E., Rugge, M., and Genta, R. M. (2013). Autoimmune atrophic gastritis–pathogenesis, pathology and management. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 10, 529–541. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2013.101

Ni, J. J., Li, X. S., Zhang, H., Xu, Q., Wei, X. T., Feng, G. J., et al. (2022). Mendelian randomization study of causal link from gut microbiota to colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer 22:1371. doi: 10.1186/s12885-022-10483-w

O'Callaghan, J., and O'Toole, P. W. (2013). Lactobacillus: host-microbe relationships. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 358, 119–154. doi: 10.1007/82_2011_187

Odamaki, T., Kato, K., Sugahara, H., Hashikura, N., Takahashi, S., Xiao, J.-Z., et al. (2016). Age-related changes in gut microbiota composition from newborn to centenarian: a cross-sectional study. BMC Microbiol. 16:90. doi: 10.1186/s12866-016-0708-5

Quast, C., Pruesse, E., Yilmaz, P., Gerken, J., Schweer, T., Yarza, P., et al. (2013). The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D590–D596. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1219

Rojas-Tapias, D. F., Brown, E. M., Temple, E. R., Onyekaba, M. A., Mohamed, A. M. T., Duncan, K., et al. (2022). Inflammation-associated nitrate facilitates ectopic colonization of oral bacterium Veillonella parvula in the intestine. Nat. Microbiol. 7, 1673–1685. doi: 10.1038/s41564-022-01224-7

Sender, R., Fuchs, S., and Milo, R. (2016). Are we really vastly outnumbered? Revisiting the ratio of bacterial to host cells in humans. Cell 164, 337–340. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.01.013

Shah, S. C., Piazuelo, M. B., Kuipers, E. J., and Li, D. (2021). AGA clinical practice update on the diagnosis and management of atrophic gastritis: expert review. Gastroenterology 161, 1325-32.e7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.06.078

Watari, J., Chen, N., Amenta, P. S., Fukui, H., Oshima, T., Tomita, T., et al. (2014). Helicobacter pylori associated chronic gastritis, clinical syndromes, precancerous lesions, and pathogenesis of gastric cancer development. World J. Gastroenterol. 20, 5461–5473. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i18.5461

Yang, K., Xu, M., Zhong, F., et al. (2018). Rapid differentiation of Lactobacillus species via metabolic profiling. J. Microbiol. Methods 154, 147–155. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2018.10.013

Yang, L. (2006). Incidence and mortality of gastric cancer in China. World J. Gastroenterol. 12, 17–20. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i1.17

Yang, T., Wang, R., Liu, H., Wang, L., Li, J., Wu, S., et al. (2021). Berberine regulates macrophage polarization through IL-4-STAT6 signaling pathway in Helicobacter pylori-induced chronic atrophic gastritis. Life Sci. 266:118903. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.118903

Yin, Y., Liang, H., Wei, N., and Zheng, Z. (2022). Prevalence of chronic atrophic gastritis worldwide from 2010 to 2020: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Palliat. Med. 11, 3697–3703. doi: 10.21037/apm-21-1464

Yuan, H., Qiu, J., Zhang, T., Wu, X., Zhou, J., and Park, S. (2021). Quantitative changes of Veillonella, Streptococcus, and Neisseria in the oral cavity of patients with recurrent aphthous stomatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Oral Biol. 129:105198. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2021.105198

Yuan, X., Chen, B., Duan, Z., Xia, Z., Ding, Y., Chen, T., et al. (2021). Depression and anxiety in patients with active ulcerative colitis: crosstalk of gut microbiota, metabolomics and proteomics. Gut Microbes 13:1987779. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2021.1987779

Zhang, L., Wang, Z., Zhang, X., Zhao, L., Chu, J., Li, H., et al. (2022). Alterations of the gut microbiota in patients with diabetic nephropathy. Microbiol. Spectr. 10:e0032422. doi: 10.1128/spectrum.00324-22

Zheng, S.-Y., Zhu, L., Wu, L.-Y., Liu, H.-R., Ma, X.-P., Li, Q., et al. (2023). Helicobacter pylori-positive chronic atrophic gastritis and cellular senescence. Helicobacter 28:e12944. doi: 10.1111/hel.12944

Zhou, Y., Ye, Z., Lu, J., Miao, S., Lu, X., Sun, H., et al. (2020). Long-term changes in the gut microbiota after 14-day bismuth quadruple therapy in penicillin-allergic children. Helicobacter 25:e12721. doi: 10.1111/hel.12721

Keywords: chronic atrophic gastritis, gut microbiota, Helicobacter pylori, gastritis, gastric microenvironment

Citation: Li H, Hu Y, Huang Y, Ding S, Zhu L, Li X, Lan M, Huang W and Lin X (2024) The mutual interactions among Helicobacter pylori, chronic gastritis, and the gut microbiota: a population-based study in Jinjiang, Fujian. Front. Microbiol. 15:1365043. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2024.1365043

Received: 03 January 2024; Accepted: 29 January 2024;

Published: 14 February 2024.

Edited by:

Mudasir Rashid, Howard University Hospital, United StatesReviewed by:

Sameer A. Mir, National Institutes of Health (NIH), United StatesCopyright © 2024 Li, Hu, Huang, Ding, Zhu, Li, Lan, Huang and Lin. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xuejuan Lin, bHhqZmp6eUAxMjYuY29t

†These authors share first authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.