- 1College of Ecology and Environment, Nanjing Forestry University, Nanjing, China

- 2Cell Factory Research Centre, Korea Research Institute of Bioscience and Biotechnology (KRIBB), Daejeon, Republic of Korea

- 3Department of Environmental Biotechnology, KRIBB School of Biotechnology, Korea University of Science and Technology (UST), Daejeon, Republic of Korea

A free-living Bradyrhizobium strain isolated from a contaminated sediment sample collected at a water depth of 4 m from the Hongze Lake in China was characterized. Phylogenetic investigation of the 16S rRNA gene, concatenated housekeeping gene sequences, and phylogenomic analysis placed this strain in a lineage distinct from all previously described Bradyrhizobium species. The sequence similarities of the concatenated housekeeping genes support its distinctiveness with the type strains of the named species. The complete genome of strain S12-14-2 consists of a single chromosome of size 7.3M. The strain lacks both a symbiosis island and important nodulation genes. Based on the data presented here, the strain represents a new species, for which the name Bradyrhizobium roseus sp. nov. is proposed for the type strain S12-14-2T. Several functional differences between the isolate and other published genomes indicate that the genus Bradyrhizobium is extremely heterogeneous and has functions within the community, such as non-symbiotic nitrogen fixation. Functional denitrification and nitrogen fixation genes were identified on the genomes of strain S12-14-2T. Genes encoding proteins for sulfur oxidation, sulfonate transport, phosphonate degradation, and phosphonate production were also identified. Lastly, the B. roseus genome contained genes encoding ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase, a trait that presumably enables autotrophic flexibility under varying environmental conditions. This study provides insights into the dynamics of a genome that could enhance our understanding of the metabolism and evolutionary characteristics of the genus Bradyrhizobium and a new genetic framework for future research.

Introduction

The genus Bradyrhizobium is a relatively well-studied rhizobial bacteria and well known for symbiosis and endophytic interaction with leguminous plants, where they exchange nutrients for survival. The genus includes a diverse collection of globally distributed bacteria that can nodulate a wide range of legumes (Salminen and Streeter, 1987; Van Rhijn and Vanderleyden, 1995; Okubo et al., 2012; Parker, 2015; Remigi et al., 2016; Sprent et al., 2017; Claassens et al., 2023; Lafay et al., 2023). It was widely recognized that the Bradyrhizobium species were capable of nitrogen fixation and the formation of symbiotic nodules in the roots of leguminous plants. The symbiotic species are crucial for soil health, plant growth, and food security, whereas nitrogen-fixing species are critical for the global nitrogen cycle (Jordan, 1982; Ladha and So, 1994; Stacey et al., 1995; Remigi et al., 2016; Gogoi et al., 2018). Members of Bradyrhizobium are characterized extensively for their symbiotic lifestyle with leguminous plants to form symbiotic nodules. Bradyrhizobium has biologically significant functions in soils, including photosynthesis, nitrogen fixation, denitrification, and degradation of aromatic compounds and others. Especially in the global nitrogen cycle, Bradyrhizobium removes nitrogen through heterotrophic denitrification and also has multiple roles in agriculture (Kaneko et al., 2002; Okubo et al., 2012). Nodulating Bradyrhizobium species typically contain nod and nif genes associated with nodulation and nitrogen fixation, respectively, the so-called symbiotic properties. Due to these characteristics, Bradyrhizobium has been regarded as a model of legume-rhizobia symbiosis and an ecologically significant microbe. However, nodulation-deficient isolates have been discovered and characterized, even though they possess genes for nitrogen fixation, and some Bradyrhizobium isolates recovered from forest soils have been found to lack both nodulation and nitrogen-fixing functions (VanInsberghe et al., 2015; Jones et al., 2016). A culture-independent investigation has shown that the population of Bradyrhizobium in soil habitats is different from the rhizosphere of leguminous plants (VanInsberghe et al., 2015), suggesting that non-symbiotic Bradyrhizobia inhabit physically or functionally distinct niches.

Understanding the mechanisms of bradyrhizobial adaptation to independent existence in diverse environments is becoming increasingly important and urgent and may reveal the genetic potential of this globally significant genus. In the present study, we characterized a novel species of Bradyrhizobium isolated from freshwater sediment of the Hongze Lake in China. To reveal the genetic diversity and physiological features, here, we report the isolation, and the sequencing, assembly, taxonomic classification, and annotation of the genome of a new species of the genus Bradyrhizobium. These investigations will be extremely beneficial for elucidating its putative metabolism, contributing to a greater understanding of free-living Bradyrhizobium isolates, enhancing knowledge of the genes and enzymes involved in metabolic pathways, and possibly identifying genomic markers that can be utilized in future ecological studies.

Materials and methods

Sampling, isolation, and growth condition

Strain S12-14-2 was recovered from a contaminated sediment sample (33°14′26″N, 118°35′40″E) collected at a water depth of 4 m from Hongze Lake, the fourth largest freshwater lake in China. The Hongze Lake is located in the Jiangsu Province and surrounded by Suqian and Huai’an cities; it has a surface area of 1,960 km2, a mean water depth of 1.77 m, a maximum depth of 4.37 m, and a volume of 28 × 108 m3 (Gao et al., 2009; Li et al., 2011). The ecological risk of the Hongze Lake sediments has been assessed. Heavy metals including copper (Cu), zinc (Zn), lead (Pb), cadmium (Cd), chromium (Cr), mercury (Hg), arsenic (As), iron (Fe), aluminum (Al), and manganese (Mn) have been identified in the lake sediments of the Hongze Lake, and antibiotics like atrazine and ofloxacin were also detected (Yao et al., 2016; Wu et al., 2023). One gram of a sediment sample was used to screen for bacterial strains with the serial dilution method. The strain was grown on modified R2A medium at 30°C under dark conditions (Jin et al., 2019).

Morphological and physiological characteristics

The mobility and morphology of the colonies were examined using a phase-contrast microscope (Nikon Optiphot, 1,000× magnification) and transmission electron microscopy (Philips CM-20). The growth temperature range, pH range, and salt tolerance were determined following the methods described by Jin et al. (2021). Duplicated antibiotic-susceptibility of strain S12-14-2 was checked on R2A agar medium using the filter-paper disk method (Li et al., 2020), where the disks contained the following: nalidixic acid (30 μg ml–1), tetracycline (30 μg ml–1), amikacin (30 μg ml–1), ampicillin/sulbactam (20 μg ml–1, 1:1), kanamycin (30 μg ml–1), vancomycin (30 μg ml–1), chloramphenicol (30 μg ml–1), teicoplanin (30 μg ml–1), spectinomycin (25 μg ml–1), gentamicin (30 μg ml–1), streptomycin (25 μg ml–1), rifampicin (30 μg ml–1), lincomycin (15 μg ml–1), and erythromycin (30 μg ml–1). Positive results were observed for halo diameters greater than 10 mm after 5 days of incubation at 30°C. For the comparative cellular fatty acids analysis, strain S12-14-2 together with the reference strains Bradyrhizobium erythrophlei LMG 28425T, Bradyrhizobium jicamae LMG 24556T, Bradyrhizobium lablabi LMG 25572T, Bradyrhizobium mercantei LMG 30031T, Bradyrhizobium elkanii KACC 10647T, and Bradyrhizobium japonicum KACC 10645T were cultured on R2A agar for 2 days at 30°C. Standardized cell harvesting and extraction were performed according to Jin et al. (2022a), and the identification was performed using the TSBA 6 (Trypticase Soy Broth Agar) database with the Sherlock software 6.1. Carbon source utilization, enzyme activities and other physiological and biochemical activities were observed using the API 20NE, API ID 32GN, and API ZYM kits (bioMérieux, l’Etoile, France) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

DNA extraction, PCR amplification, and genomic sequencing

Genomic DNA was extracted using the FastDNA™ SPIN kit following the manufacturer’s instructions. The concentration and purity of the DNA were then checked on a ND-2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The 16S rRNA genes of strain S12-14-2 were amplified by PCR method using the universal primer sets 27F/1492R (Weisburg et al., 1991) and then identified using the EzBioCloud web service (Yoon et al., 2017). The use of multilocus sequence analysis (MLSA) has been proven useful for the classification and identification of several groups of rhizobia. In the genus Bradyrhizobium, the 16S rDNA sequences provide minimal taxonomic information due to the high degree of conservation among species and the relatively high sequence similarity. Consequently, MLSA studies of glnII, recA, dnaK, rpoB, and ITS genes were performed to assess the taxonomic position of the free-living strain among identified species (Martens et al., 2008; Menna et al., 2009; Rivas et al., 2009; Pérez-Yépez et al., 2014; Gnat et al., 2016). The partial sequences of the housekeeping genes, glnII, recA, dnaK, rpoB, and ITS genes, were amplified by PCR method. The primer sets and PCR amplification conditions were described in a previous study (Menna et al., 2009; Delamuta et al., 2013). Whole genome sequencing was done at Novogene Biotechnology, Beijing, China, using the Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) RS II single molecule real-time (SMRT) platform together with the Illumina HiSeq technology. The quality of the genome assemblies was assessed using SMRT Link version 5.0.1.

Phylogenetic analyses and genome annotation

For phylogenetic analysis of strain S12-14-2, the 16S rRNA sequences of Bradyrhizobium type strains were downloaded from the NCBI database. The sequences were edited and aligned with BIOEDIT and CLUSTAL X software, respectively (Thompson et al., 1997; Hall, 1999), and the phylogenetic tree was reconstructed using the MEGA7 software (Kumar et al., 2016). For genomic annotations, the draft genome sequence was applied to the RAST pipeline, and comparisons of the genome were performed in the SEED Viewer (Aziz et al., 2008, 2012). The protein coding sequences (CDSs) were submitted to the COG (Clusters of Orthologous Groups) database1 for functional classification and summary statistics (Tatusov et al., 1997, 2003). For the pangenome analysis, we followed Delmont and Eren’s description of the Anvi’o workflow (Delmont and Eren, 2018), a community-driven, open-source analysis and visualization platform for microbial-omics, which is available at http://merenlab.org/software/anvio/. The structures of protein monomeric units were predicted using the SWISS-MODEL (Bienert et al., 2017; Waterhouse et al., 2018). Biosynthetic gene clusters (BGC) were identified and analyzed using the secondary metabolite databases antiSMASH database.2 The average nucleotide identity (ANI) was determined using the OrthoANI tool in the EZBioCloud server, and the digital DNA–DNA hybridization (dDDH) value was calculated with the Genome-to-Genome Distance Calculator (GGDC 2.1) (Meier-Kolthoff et al., 2013; Yoon et al., 2017). The average amino acid identity (AAI) was calculated with the AAI web-based calculator developed by Konstantinidis Lab.3

Results and discussion

Physiological features

The strain displayed growth on R2A and NA agar media after 5 days of incubation at 28°C but not on TSA, LB, or MA media. Colonies were pink in color and less than 1 mm in diameter after 5 days of growth at 28°C on R2A agar medium. Microscopically, the strain represented a Gram-negative and rod-shaped bacterium that ranged in size from 2.0-2.3 × 0.7-0.8 μm (Supplementary Figure 1). Strain S12-14-2T showed resistance to the following antibiotics tested: nalidixic acid (30 μg ml–1), vancomycin (30 μg ml–1), chloramphenicol (30 μg ml–1), teicoplanin (30 μg ml–1), streptomycin (25 μg ml–1), rifampicin (30 μg ml–1), and lincomycin (15 μg ml–1); and susceptible to tetracycline (30 μg ml–1), amikacin (30 μg ml–1), ampicillin/sulbactam (20 μg ml–1, 1:1), kanamycin (30 μg ml–1), spectinomycin (25 μg ml–1), gentamicin (30 μg ml–1), and erythromycin (30 μg ml–1). The major fatty acids (>10%) of the strain were sorted into two groups C16:0 and C18:1 ω7c and/or C18:1 ω6c, which was consistent with species from the genus Bradyrhizobium (Supplementary Table 1). The carbon source assimilation, enzyme activity, and some other physiological features are summarized in Supplementary Table 2.

Genomic analysis: the taxonomic status

The phylogenetic analysis based on 16S rRNA gene sequences revealed that strain S12-14-2 should taxonomically be classified to the genus Bradyrhizobium. The strain shared 99.36–99.69% pairwise similarity with B. lablabi CCBAU 23086T, B. jicamae PAC68T, B. erythrophlei CCBAU 53325T, and B. algeriense RST89T and less than 99.3% with the other species within the genus Bradyrhizobium (Table 1). The 16S rRNA gene sequence neighbor-joining tree revealed that strain S12-14-2 unambiguously clustered with members of Bradyrhizobium. Due to its high level of conservation within the genus Bradyrhizobium, the 16S rRNA gene is an inadequate molecular marker for distinguishing species (Germano et al., 2006; Rivas et al., 2009). Therefore, a genome-based phylogenetic analysis was used. The topology of the phylogenetic and phylogenomic trees is consistent with the sequence similarities of the 16S rRNA gene between the novel strain and the type strains of the Bradyrhizobium species (Figure 1 and Supplementary Figure 2).

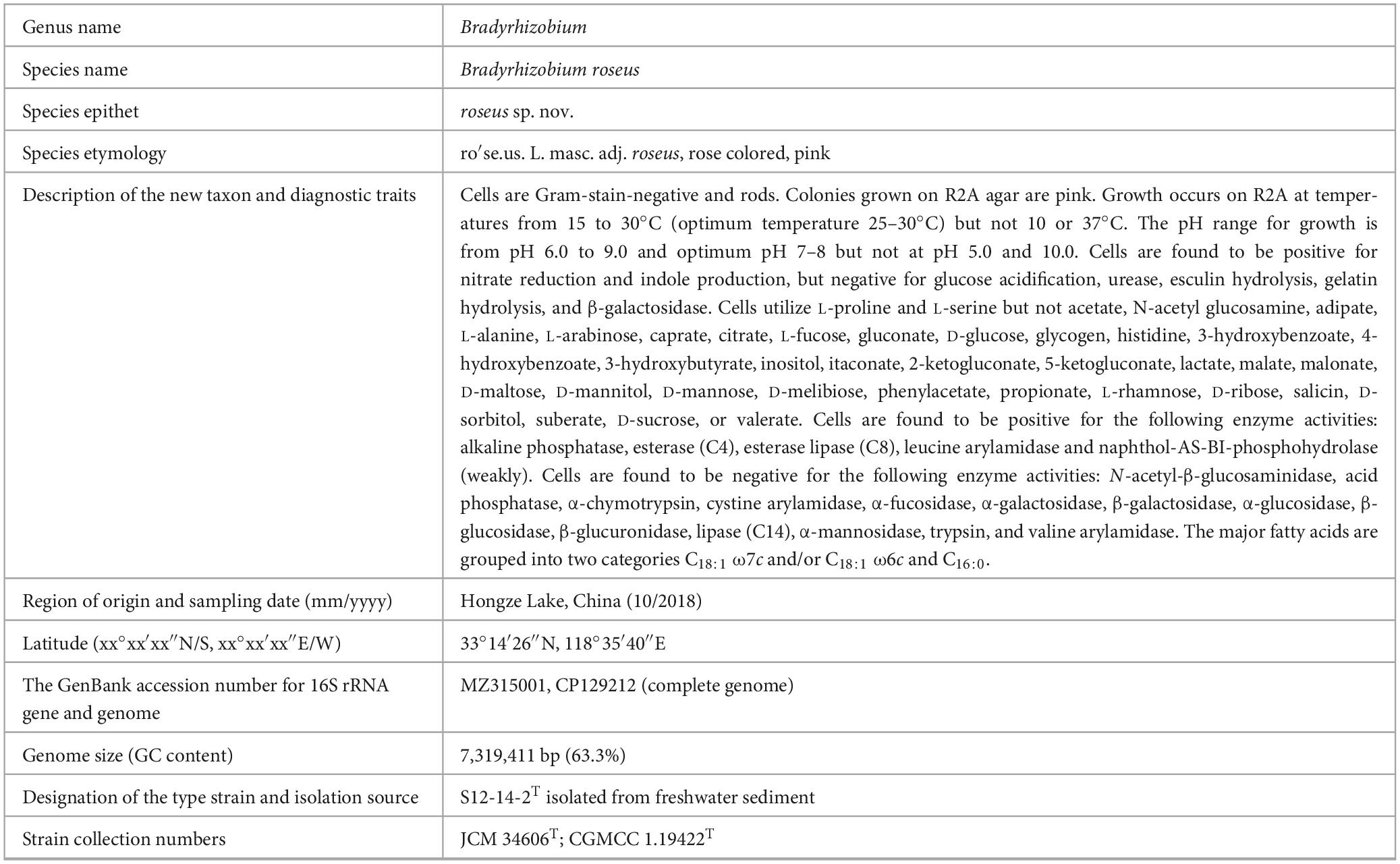

Table 1. 16S rRNA gene, ANI, AAI similarities (%), and digital DNA–DNA relatedness (%) between novel strain S12-14-2T and related type strains of Bradyrhizobium.

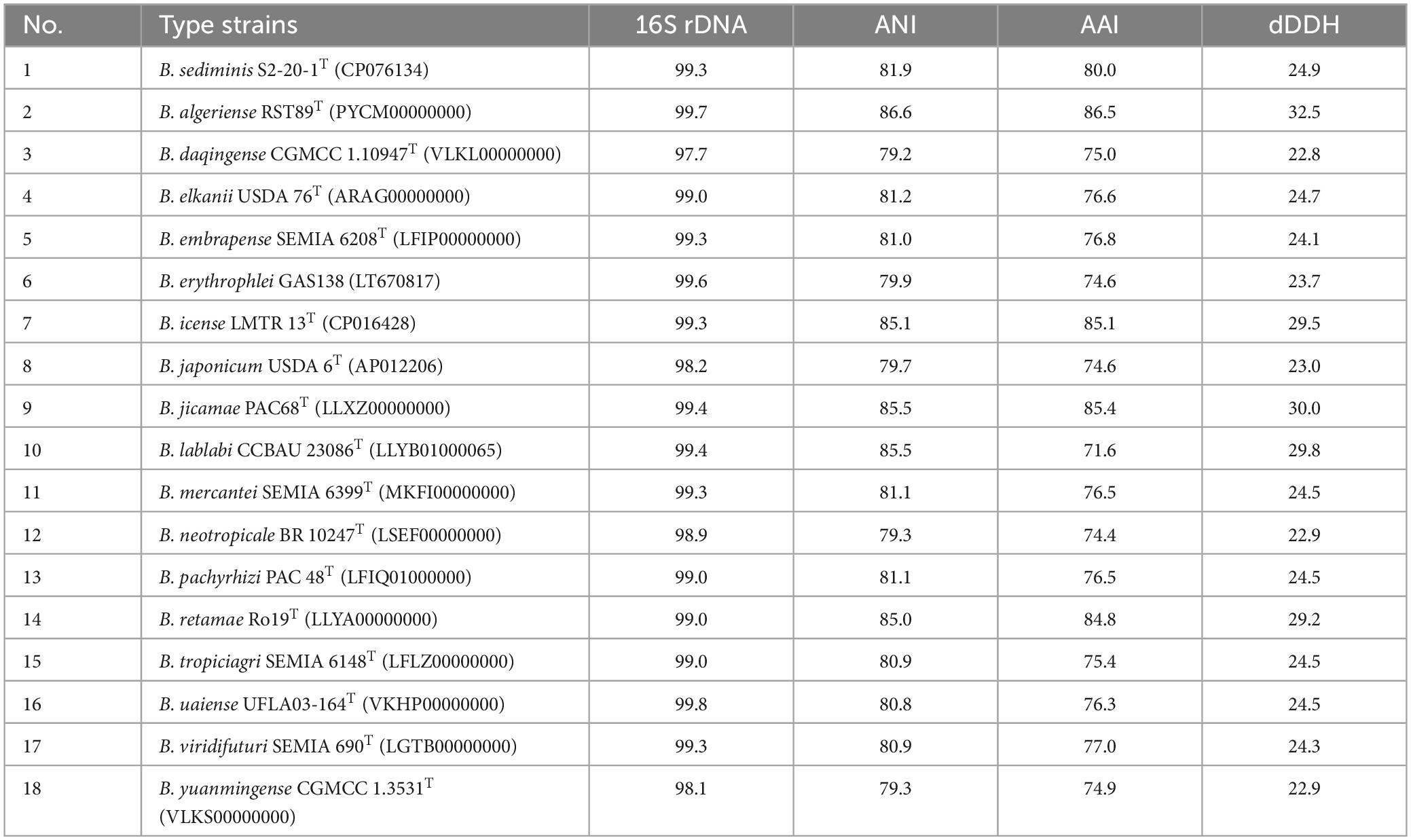

Figure 1. Phylogenomic tree based on genome sequences of strain S12-14-2T and its closely related type strains of Bradyrhizobium in the TYGS (https://tygs.dsmz.de/) and iTOL.

Within the genus Bradyrhizobium, phylogenetic analysis based on MLSA (multilocus sequence analysis) of housekeeping genes is a powerful tool for discriminating species (Rivas et al., 2009; Tang et al., 2012; Duran et al., 2014). The phylogenetic tree of five concatenated housekeeping gene sequences (ITS, dnaK, glnII, recA, and rpoB) located the novel strain in a clearly distinct lineage from the named Bradyrhizobium species. The phylogenetic tree of the concatenated ITS-dnaK-glnII-recA-rpoB gene sequences confirmed the placement of the novel strain in a lineage distinct from the named Bradyrhizobium species (Supplementary Figure 3). ANI, AAI, and dDDH analyses based on whole-genome sequences were implemented for additional characterization. We estimated the values for the complete genome sequence of S12-14-2 by conducting pair-wise comparisons with genome sequences of the type strains of Bradyrhizobium species obtained from public databases. The ANI values of the named species ranged from 79.2% (Bradyrhizobium daqingense) to 86.6% (B. algeriense), which is significantly lower than the 95–96% threshold value for circumscription of bacterial species (Konstantinidis and Tiedje, 2005; Rivas et al., 2009; Chun et al., 2018; Ciufo et al., 2018). The AAI (dDDH) values for all pairwise comparisons between the novel strain and related Bradyrhizobium species ranged from 71.6 to 86.5% (22.8–32.5%) (Table 1), which is also under the borderline of 95% (ANI) and 70% (dDDH) species delineation (Goris et al., 2007; Richter and Rossello-Mora, 2009; Luo C. et al., 2014; Konstantinidis et al., 2017).

General genome properties

The genome of isolate S12-14-2 has a size of 7,319,411 base pairs, a GC content of 63.3%, three rRNA genes, 62 tRNA genes, and 6893 CDS, of which 5,838 genes were allocated to COG (Supplementary Table 3). Bradyrhizobium spp. have relatively large genomes compared to other groups, ranging between 5 and 11M, whereas the smallest genome size found to date is approximately 5M in the free-living strain S2-11-2 (Ormeño-Orrillo and Martínez-Romero, 2019; Jin et al., 2022b; Klepa et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2023). The GC content is consistent with other Bradyrhizobium type strains (Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 2). The abundant genes were associated with amino acid transport and metabolism (COG category E), inorganic ion transport and metabolism (COG category P), energy production and conversion (COG category C), transcription (COG category K), signal transduction mechanisms (COG category T), and cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis (COG category M), and lipid transport and metabolism (COG category I), and approximately 32.5% of the genes were assigned to the unknown function COG category (Supplementary Table 4).

Pangenomics and secondary metabolites

To investigate the genomic diversity of Bradyrhizobium sp. S12-14-2 and related Bradyrhizobium spp., we compiled a total of 44 complete whole genomes (including 7 free-living and 34 symbiotics) downloaded from the NCBI. This dataset contains genomes representing 41 species validly published. Across the entire dataset, the genome size (GS) varied between 5.5 and 11.5M (mean, 8.5M); the GC content varied between 61.4 and 65.1% (mean, 64.9), and the number of predicted genes ranged from 5,220 to 11,061 (mean, 8,111).

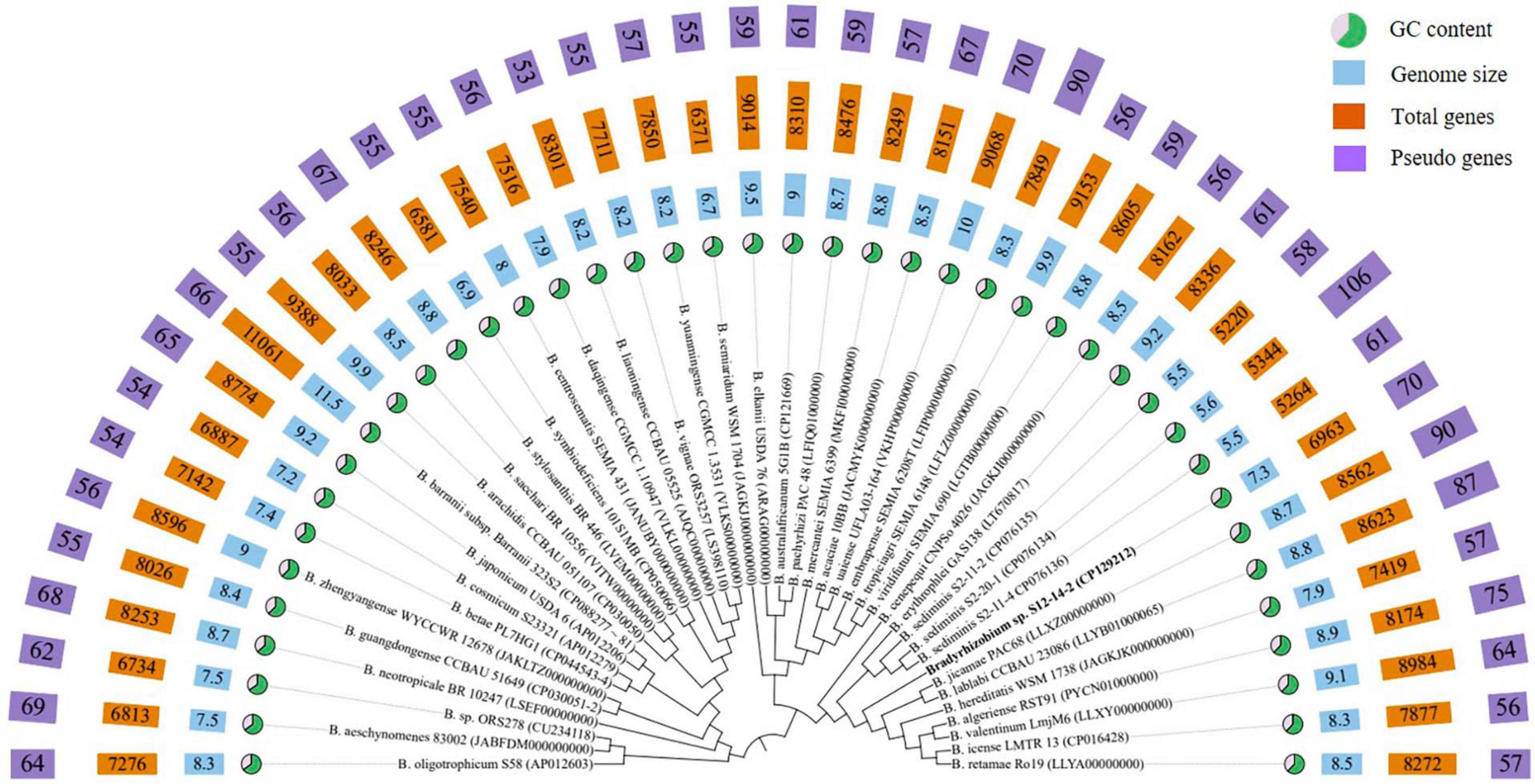

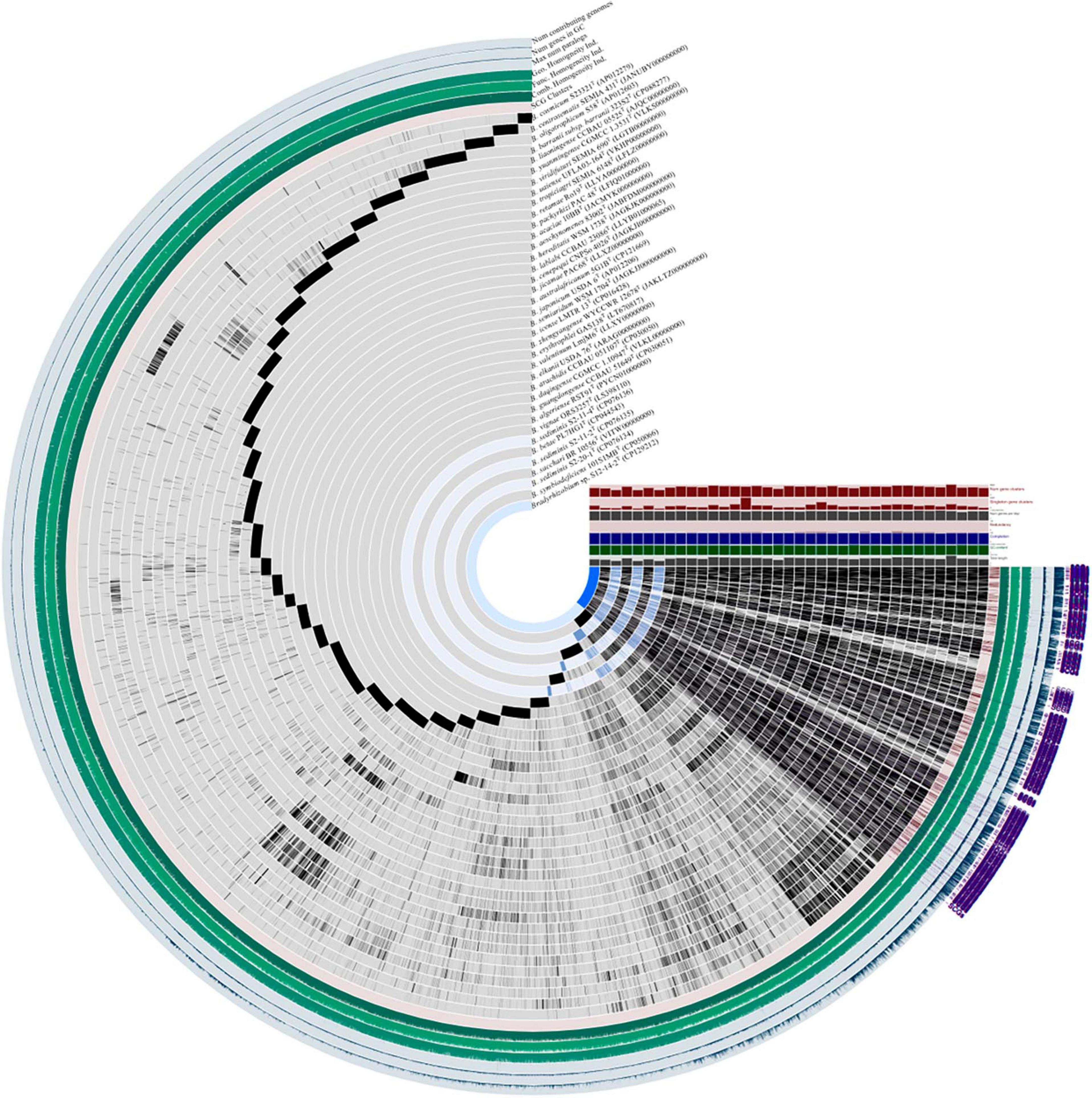

Following the workflow, pangenomic analysis of 37 Bradyrhizobium strains was performed using Anvi’o (version 7.1). Single copy gene clusters (SCGs) are shown in purple color on the outside, which are drawn by 1,235 gene clusters from 43,916 splits and 44,526 objects. Bradyrhizobium sp. S12-14-2T exhibited a similar pattern of blue-colored single copy gene clusters as the other three free-living microorganisms Bradyrhizobium sediminis S2-20-1T, B. sediminis S2-11-2, and B. sediminis S2-11-4. SCGs were also the same with the core genes, and others not included in the SCGs were accessory genes. B. erythrophlei GAS138T (LT670817) has the largest number of singleton gene clusters which is almost equal to 2,046 (Figure 2). BGC from 44 Bradyrhizobium genomes from the free-living and symbiotic groups were identified using antiSMASH, and a comprehensive network analysis was performed in BiG-SCAPE using all similar BGC sequences from the MIBiG databases. The average number of BGCs from the 44 genomes is 11, and the network analysis distributed 557 BGCs in different types, including 99 terpenes, 84 NRPS (non-ribosomal peptides), 93 hserlactones (homoserine lactones), 44 redox-cofactors (redox-cofactors such as PQQ), 47 RiPP-like (other unspecified ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptide products), 35 NRPS-like (NRPS-like fragmenta), and 37 TPKS (type I, II, and III PKSs), and generally, the number of secondary metabolites from free living bacteria are less than symbiotic bacteria (Supplementary Figure 4). We identified common BGCFs shared by all strains, such as terpenes and redox-cofactors and nine BGCFs not found in free-living strains, such as Bradyrhizobium sp. S12-14-2 (Supplementary Figure 4). Additionally, Bradyrhizobium sp. S12-14-2 possesses a phosphonate-producing gene cluster, confirmed by phosphorous metabolism-related genetic analysis.

Figure 2. Pangenome analysis of Bradyrhizobium species including Bradyrhizobium sp. S12-14-2T and closely related strains calculated with Anvi’o version 7.1. Dark regions in purple color (SCGs) represent genes (black) found in each genome at least one time.

Genome size of Bradyrhizobium

Genome size variation is a biological trait, although its evolutionary sources and effects are debated. GS’s neutrality, selective pressures, and strength are unknown. The genetic segments responsible for this diversity directly affect evolutionary outcomes and are targeted by diverse evolutionary pressures. Bradyrhizobium isolates have rather big genomes ranging from 5 to 11M, with an average size of 8.6M (Ormeño-Orrillo and Martínez-Romero, 2019; Avontuur et al., 2022; Jin et al., 2022b; Claassens et al., 2023; Lafay et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2023). Nevertheless, the range of GSs within the genus remains unknown. The smallest genome was 5.5M in length and related to strain S12-14-2 recovered from freshwater sediment. The largest full assembly (11.7M) was discovered from the soil isolate GAS478 (FSRD01000000). Notably, strains S12-14-2 (7.3M), S2-20-1T (5.6M), S2-11-2 (5.5M), S2-11-4 (5.5M), and GAS478 (11.7M) lacked symbiosis genes, suggesting that GS in Bradyrhizobium is unrelated to its capacity to interact with legumes. In the Nitrobacteraceae family, Bradyrhizobium has the largest genome, followed by Tardiphaga and Bosea. Bradyrhizobium, Tardiphaga, and Bosea, three taxa with large genomes, interact with plants (De Meyer et al., 2012; Ormeño-Orrillo and Martínez-Romero, 2019). And taxa with small genomes, including Nitrobacter, Oligotropha, and Variibacter, were discovered to be metabolically constrained, indicating that the Nitrobacteraceae GS appears to be associated with lifestyle. Understanding the GS variation and its causes and effects requires trustworthy methodologies; however, there are still obstacles. From genome annotation and content analysis to laboratory- and sequence-based GS measurement accuracy, there are problems and recommended practices. Even among big consortia building high-quality genome assemblies, gold standards and best practices are continually changing.

Motility

The genome of strain S12-14-2 contains 192 genes for motility via flagella and genes for chemotaxis (data not shown). At least 132 genes related to flagellar motility (components of the flagellar apparatus or specific regulators) are grouped in two clusters in the genome separated by unknown genes. Notably, the cultured S12-14-2 cells lack any discernible flagella or pili (Supplementary Figure 1). The reason could be that twitching motility may be a more efficient mode of locomotion in environments devoid of conditions that require or prohibit pilus-facilitated or flagellum-powered movement.

Genes involved in carbon metabolism and photosynthesis

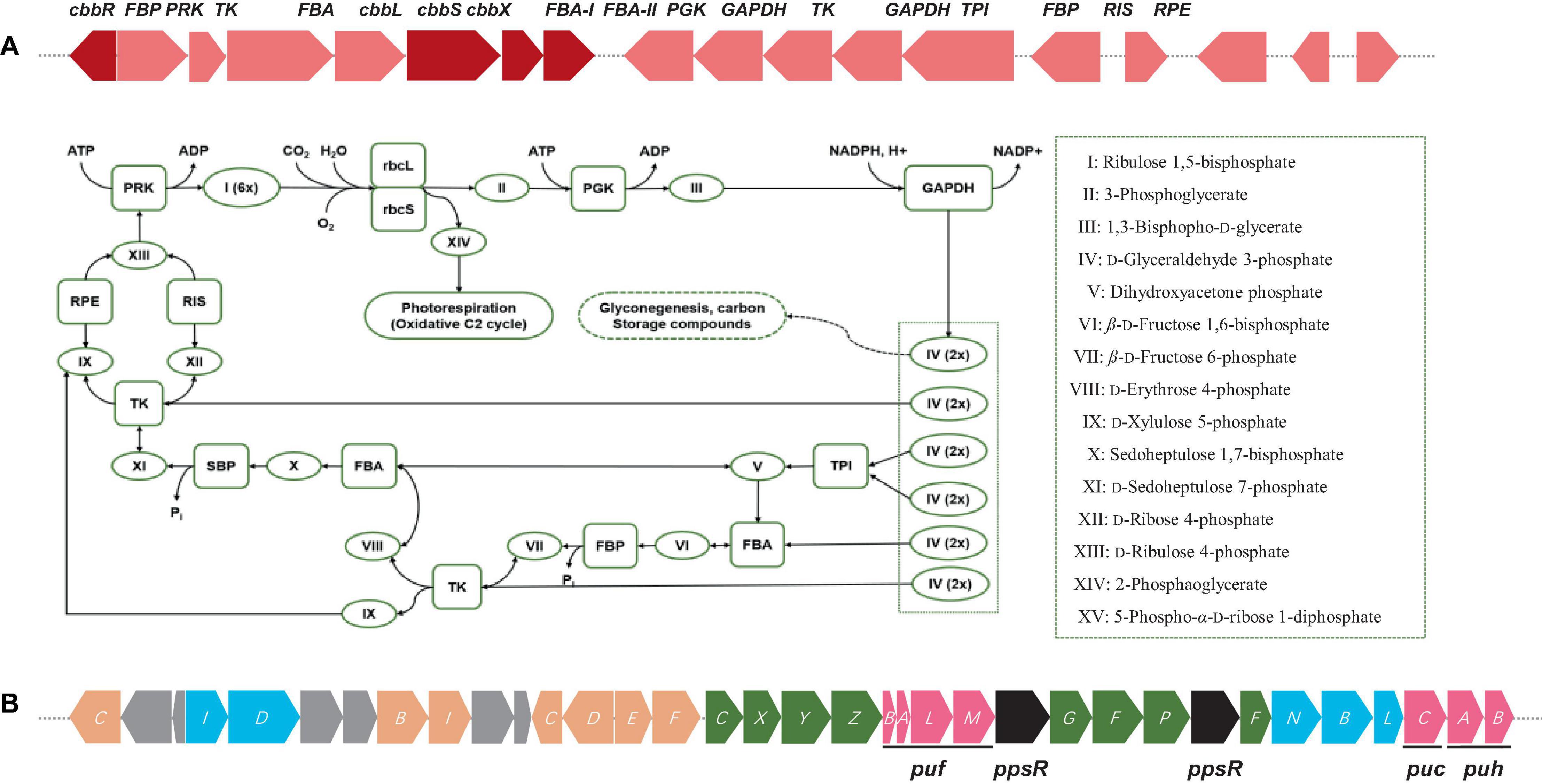

Free-living Bradyrhizobium organisms also perform vital roles in soil ecology, nutrient cycling, and carbon metabolism. As free-living microbes, they must acquire carbon from other environmental sources. Bradyrhizobium can metabolize a vast array of carbon sources, including simple carbohydrates, organic acids, and amino acids, via diverse biochemical pathways (VanInsberghe et al., 2015; Tao et al., 2021). The TCA (tricarboxylic acid) cycle, also known as the Krebs cycle, is one of the primary pathways involved in carbon metabolism in free-living Bradyrhizobium. This pathway is essential for the growth and survival of microorganisms as it is involved in producing energy from carbon sources. The complete gene sets of the TCA cycle, Entner–Doudoroff pathway, and glycolysis and gluconeogenesis were observed in the genome of strain S12-14-2. Furthermore, genes for encoding phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) carboxylase (EC 4.1.1.31) and pentose phosphate pathway were also observed. The genome of S12-14-2 contained genes for encoding RuBisCO (ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase) or the light-harvesting complex (Figure 3A), which means that strain S12-14-2 may fix CO2 and potentially have photosynthetic function.

Figure 3. (A) Diagram of Calvin cycle and RuBisCO gene cluster arrangements including RuBisCo (RbcL), phosphoribulokinase (PRK), fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase (FBP), etc. Color keys: red, RuBisCO subunits and RuBisCo activation protein coding genes: rose, other carbon fixation related genes. (B) Photosynthetic gene cluster of Bradyrhizobium sp. S12-14-2T. Color keys: green, bch genes (bacteriochlorophyll synthesis); orange, crt genes (carotenoid synthesis); blue, chl gene (light-independent protochlorophyllide reductase); pink, puh (photosynthetic reaction centers), puf and puc (light-harvesting complexes); black, regulatory proteins; gray, uncharacterized proteins.

The gene cluster responsible for photosynthesis in Bradyrhizobium encompasses several genes that have a crucial role in the production of pigments and proteins necessary for the process of photosynthesis. The genes in question encode various proteins, such as bacteriochlorophyll, carotenoids, and reaction center proteins (Gregor and Klug, 1999; Igarashi et al., 2001; Hata et al., 2023). The presence of genes associated with photosynthesis in the genome of S12-14-2 has been verified. The genetic components in this set are as follows: bacteriochlorophyll genes (bchCXYZGFPF), genes for light-independent protochlorophyllide reductase (chlIDNBL), carotenoid genes (crtCBICDEF), genes for light harvesting polypeptides (pucCAB), and genes for reaction center subunits (puhBA/pufLM) (Figure 3B). Several species of Bradyrhizobium have the ability to utilize carbon dioxide through the Calvin cycle, also known as the Calvin–Benson–Bassham cycle. In this metabolic pathway, the enzyme ribulose-1, 5-bisphosphate carboxylase oxygenase (RuBisCo) has a crucial role. The strain S12-14-2 was found to possess all gene sets associated with the Calvin cycle except for a gene responsible for encoding sedoheptulose-1,7-bisphosphatase (SBP) (Figure 3A). The Calvin cycle involves the execution of distinct tasks by RuBisCo (RbcL), phosphoribulokinase (PRK), and SBP. The combined utilization of RuBisCo and PRK can be used as reliable indicators for the presence of the cycle within a particular organism. However, the enzymatic activity of SBP in bacteria is commonly facilitated by fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase (FBP) with a dual sugar (Jiang et al., 2012).

Genes involved in nitrogen metabolism and nodulation

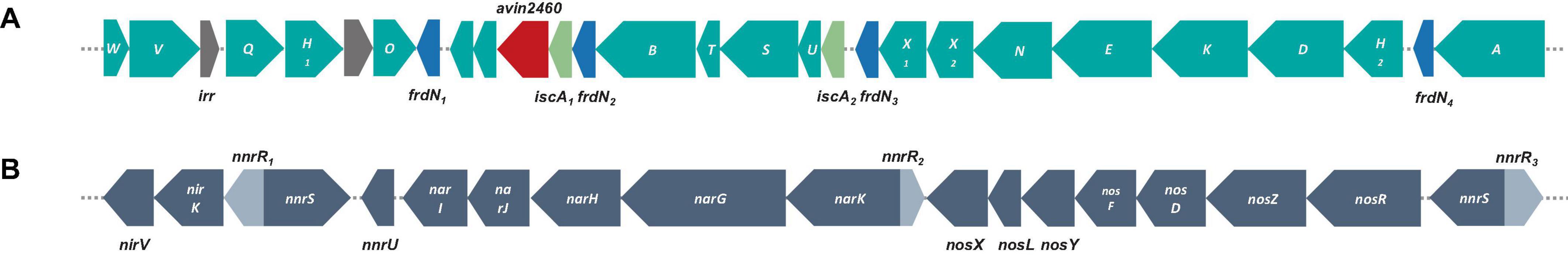

Nitrogen fixation is extremely important in environmental sustainability, particularly in nitrogen-deficient soil (Lindström et al., 2010; Hungria et al., 2015). In legume-rhizobium symbiosis, this activity is key for soil health and plant growth (Jensen and Hauggaard-Nielsen, 2003; Meena et al., 2018). Genes encoding NifKDH (nitrogenase α-, ß-subunits and reductase, respectively); and NifENB (nitrogenase assembly proteins) are considered the minimal gene set required for a diazotrophic phenotype; those genes encode a FeMo-cofactor-containing nitrogenase (Kaneko et al., 2002; Dos Santos et al., 2012; Sprent et al., 2017). All genes encoding these nitrogen-fixation like proteins in S12-14-2 (genes and proteins abbreviated nif and Nif, respectively, and numbered 1–2), nifABDEHKNOQSTUVWXZ, were clustered (Figure 4A). The genes encoding NifH1,2DK are located upstream of the cluster, while the genes encoding NifNE are adjacent to nifKDH. In contrast to symbiotic strains, free-living Bradyrhizobium bacteria do not have nif or nod genes, and some nod-independent strains contain just nif genes (Ferrieres et al., 2004; Bobik et al., 2006; Meilhoc et al., 2010; VanInsberghe et al., 2015). No nodulation genes were identified in the genome, indicating that strain S12-14-2 could fix atmospheric nitrogen; as for nodulation, it is uncertain whether strain S12-14-2 forms nodules at this time because of nod-factor-independence of symbiosis.

Figure 4. Genetic organization of nitrogen-fixation and denitrification related genes and surrounding genes. (A) Nitrogen-fixation gene clusters located on genome of strain S12-14-2T. (B) Denitrification gene clusters; color keys: teal, nif genes; gray, irr genes (iron-responsive regulator); blue, frdN genes (4Fe-4S ferredoxin, nitrogenase-associated); red, avin2460 [LRV (FeS)4 cluster domain protein clustered with nitrogenase cofactor synthesis]; light green, iscA genes (probable iron binding protein in nif operon); gray, denitrification related genes: nor, nitric oxide reductase; nar, nitrate reductase; nir, nitrite reductase; nnr genes [nnrS (NO sensing protein); nnrU (denitrification regulatory protein)].

Denitrification is a prominent contributor to nitrous oxide (N2O) emission in soil, serving as a substantial constituent of the worldwide nitrogen cycle. This process takes place in both terrestrial and marine ecosystems. Certain bacteria can adjust their metabolic processes in response to oxygen-depleted settings, wherein the concentration of dissolved and accessible oxygen is diminished. In such conditions, these bacteria use nitrate as a respiratory substrate for the process of denitrification (Coates et al., 2001; Luo F. et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2020). The strain S12-14-2 contains a periplasmic nitrate reductase (Nar), a copper (Cu)-containing nitrite reductase (Nir), and a Cu-dependent nitrous oxide reductase (Nos) encoded by the narGHJI, nirKV, and nosRZDFYLX genes, respectively (Figure 4B). Nitrite produced by NarGHJI will be released to the periplasm through a membrane transporter and reduced to nitric oxide (NO) by Cu-containing nitrite reductase (NirK) (Richardson, 2000; Simon and Klotz, 2013). Due of its high cytotoxicity, NO will immediately reduce to N2O by Nor (nitric oxide reductase). Typically, nor enzymes are usually periplasmic cytochrome c (cNor) or quinones (qNor) (Nordling et al., 1990; Pearson et al., 2003; Rinaldo and Cutruzzola, 2007; Simon and Klotz, 2013). Notably, the genome does not contain NO reductase genes for the reduction stage. The apparent absence of Nor-encoding genes in strain S12-14-2 is of special interest, but it is speculated that some cNor or qNor-like proteins are encoded by some other unknown genes.

Genes involved in sulfur metabolism

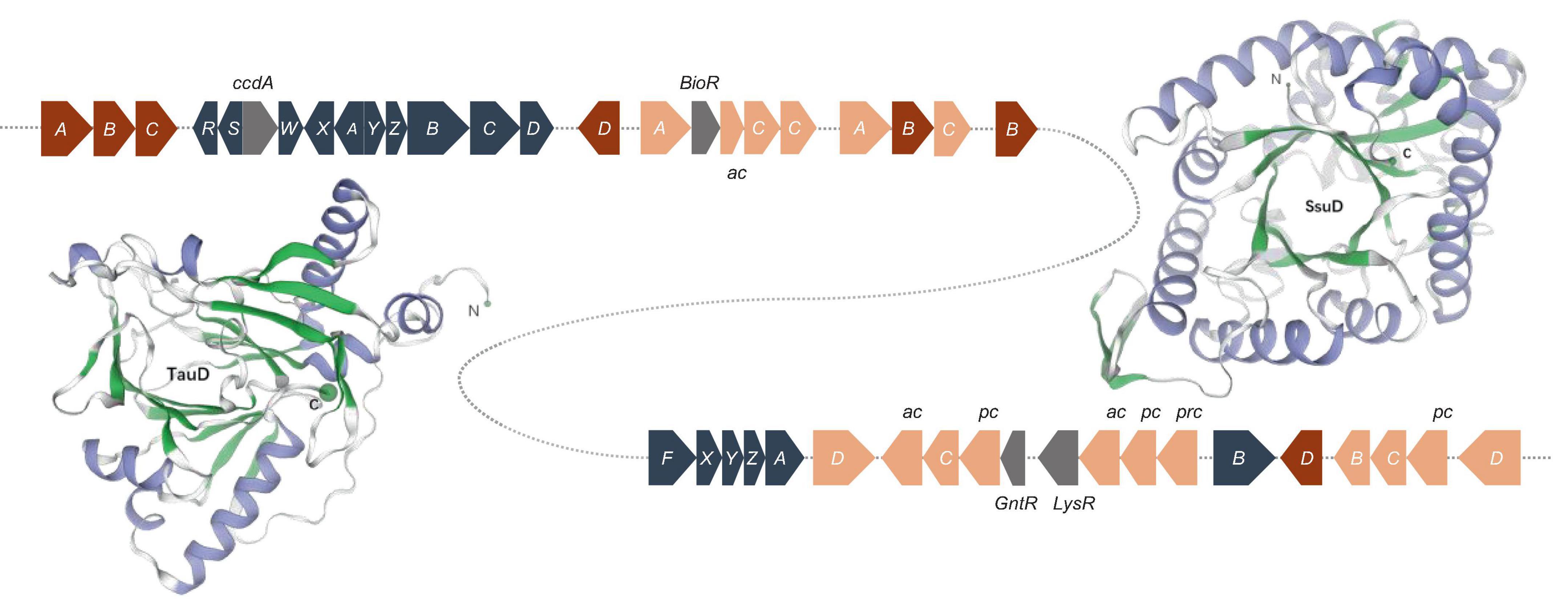

Sulfur, an amino acid component and enzyme cofactor, is essential to all organisms. Sulfide is formed by the sulfate assimilation pathway in many bacteria and integrated into sulfur-containing organic compounds. Under sulfur-limiting conditions, bacteria must receive sulfur from the environment because inorganic sulfate is not prevalent in nature. Sulfonates and sulfonate esters are natural or xenobiotic compounds (Kertesz, 2000; Van Der Ploeg et al., 2001b). Genes encoding a sulfur-oxidizing (Sox) function were discovered, and the sox gene cluster consists of 16 genes. soxR encodes a repressor protein, and soxSW encodes a periplasmic thioredoxin, which is essential for full expression of the sox genes. The subsequent soxXYZABCD genes encode four periplasmic proteins that reconstitute the Sox enzyme system: SoxXA, SoxYZ, SoxB, and SoxCD, which can convert a variety of reduced sulfur compounds to sulfates (Figure 5). Strain S12-14-2 also possess the soxF gene, which encodes flavoprotein SoxF with a sulfide dehydrogenase activity (Quentmeier et al., 2004). These sulfur oxidation Sox systems suggest that strain S12-14-2 might be capable of oxidizing thiosulfate to sulfate.

Figure 5. Sulfur oxidation gene clusters and of structure of the monomeric unit of TauD and SsuD. The TauD and SsuD enzyme exist in the form of a TIM-barrel containing 297 and 359 amino acid residues, respectively. Color key: blue gray, sox genes; red, tau genes; orange, ssu genes (ac, ABC type nitrate/sulfonate/bicarbonate transport system, ATPase component; pc, ABC-type nitrate/sulfonate/bicarbonate transport systems, periplasmic components; prc, ABC-type nitrate/sulfonate/bicarbonate transport system, permease component.); gray, regulator genes.

Under sulfur-limiting conditions, several bacteria express proteins to use organosulfonates or sulfonate esters as sulfur sources. Sulfate starvation-induced proteins ingest sulfonate, acquire sulfur from organic molecules, and defend against reactive oxygen species (Hummerjohann et al., 1998; Van Der Ploeg et al., 2001a; Ellis, 2011). A sulfonate transport system has been detected in the genome of Bradyrhizobium sp. S12-14-2, which includes sulfonate-binding protein (SsuA), ATP-binding protein (SsuB), and sulfonate permease protein (SsuC). The genes tauD and ssuD, which encode a taurine dioxygenase and an alkanesulfonate monooxygenase, respectively, were also found to be responsible for sulfonate and taurine metabolism. The tau operon encodes an ABC-type transporter and taurine dioxygenase (TauD), which oxidize taurine to hydroxytaurine. The unstable hydroxytaurine breaks down to yield the aminoacetaldehyde and sulfite products (Eichhorn et al., 1997). The SsuD monooxygenase enzyme catalyzes the desulfonation of a wide variety of organosulfonated products, producing the corresponding aldehyde and sulfonate (Eichhorn et al., 1999).

The structures of TauD and SsuD monomeric units were predicted using the SWISS-MODEL. The SsuD monomer consists of a total of 359 amino acid residues and belongs to the structural family of TIM-barrel proteins. SsuD is classified as a flavin-dependent oxidoreductase belonging to the LLM (luciferase-like monooxygenase) class. On the other hand, the TauD monomer consists of 297 amino acid residues and functions as an α-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase (Figure 5). TauD prefers taurine but may also desulfonate alkanesulfonates. Although alkanesulfonate monooxygenase enzymes can use various organosulfate substrates, they have no enzymatic activity against taurine (Ellis, 2011). These TauD and SsuD enzymes possibly work together to ensure that the bacterial cell has sufficient sulfur for biosynthetic processes. While most of these enzymes’ kinetic properties are known, much remains to be learned about their detailed mechanistic properties.

Genes involved in phosphate metabolism

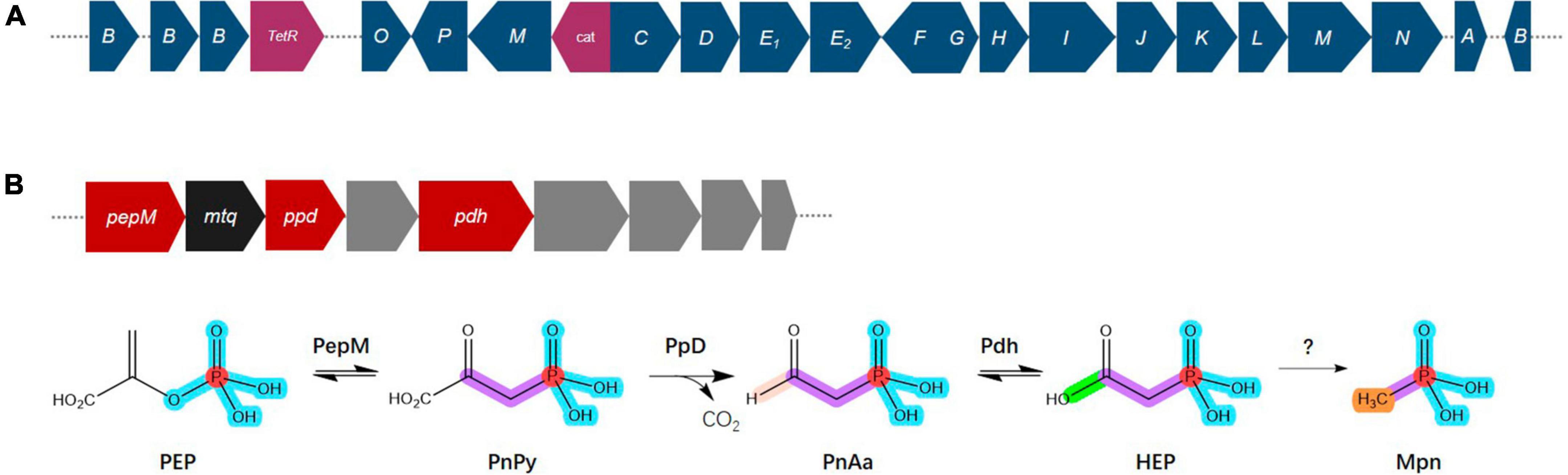

Phosphorus is an essential nutrient for all organisms and has crucial roles in respiration, energy production and storage, the biosynthesis of nucleic acids, ATP, and phospholipids and other physiological and biochemical processes in specific environments (Balemi and Negisho, 2012; Nath et al., 2017). Phosphorus availability and plant assimilation are governed by microorganisms, and phosphorus-solubilizing microorganisms are capable of dissolving insoluble phosphorus in soil and converting it into soluble phosphorus for plant absorption and use (Cao, 2014; Moro et al., 2021). Phosphonate compounds, which contain a direct C–P bond instead C–O–P ester linkage, are prevalent in the environment, where they are a significant source of organic phosphorus and a common pollutant (Horsman and Zechel, 2017; Rott et al., 2018). The degradation of phosphonates is especially advantageous for microorganisms, where the bioavailability of phosphorus is frequently a growth-limiting factor (Sosa et al., 2019). The genome of Bradyrhizobium sp. S12-14-2 contains all the predicted C–P lyase genes necessary for phosphonate degradation and the additional putative auxiliary functions (Figure 6A). These genes included a TetR family transcriptional regulator, phosphonate ABC transporters phnCDE1E2, purine ribonucleoside triphosphate phosphorylase components phnGHIJKL, a chloramphenicol acetyltransferase, a triphosphoribosyl 1-phosphonate diphosphohydrolase phnM, and a phosphoribosyl cyclic phosphodiesterase phnP.

Figure 6. Overview of the C–P lyase gene cluster and pathway. (A) Overview of phn gene organization. (B) Pathway for phosphonate production and gene organization. Phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) mutase (PepM) isomerizes PEP to phosphonopyruvate (PnPy), which is the precursor to all known phosphonate molecules. Due to this functional conservation, the pepM gene is a reliable genomic marker for the potential to produce phosphonates. Phosphonopyruvate decarboxylase (Ppd) converts PnPy to phosphonoacetaldehyde (PnAa), phosphonoacetaldehyde dehydrogenase (Pdh) dehydrogenates of PnAa to 2-hydroxyethylphosphonic acid (HEP), and finally to methylphosphonate (Mpn). Color key: dark blue, phn genes; purple, TelR (transcriptional regulator), cat (chloramphenicol acetyltransferase); red, phosphonate production related genes; black, mtq (O-methyltransferase); gray, transporters.

Phosphonates are a type of phosphorus-based metabolites distinguished by a highly stable C–P bond. They comprise a significant portion of the dissolved organic phosphorus reservoir in the oceans and are widely distributed among more primitive life forms (Villarreal-Chiu et al., 2012; Acker et al., 2022). Almost all known pathways of phosphonate biosynthesis involve a central C–P bond-forming reaction in which the enzyme PEP phosphomutase (Ppm) intramolecularly rearranges the intermediary metabolite phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) to form phosphonopyruvate (PnPy) (Metcalf and Van Der Donk, 2009; Acker et al., 2022). The genome of Bradyrhizobium sp. S12-14-2 contains the genes pepM which encodes Ppm, ppd encoding phosphonopyruvate decarboxylase (Ppd) which subsequently converts PnPy to phosphonoacetaldehyde (PnAa) in next reaction, and pdh encoding phosphonoacetaldehyde dehydrogenase (Pdh) which dehydrogenates of PnAa to 2-hydroxyethylphosphonic acid (HEP) (Figure 6B).

Conclusion

To summarize our investigations, the strain S12-14-2T from a contaminated freshwater sediment belonging to the genus Bradyrhizobium was studied through genome analysis and a polyphasic approach. The phylogenetic analysis indicated that the strain S12-14-2T was affiliated closely with the species of Bradyrhizobium, based on the phylogenetic, genomic, and physiological differences; thus, we propose strain S12-14-2T as a novel species, Bradyrhizobium roseus sp. nov., in the family Nitrobacteraceae (Table 2). The B. roseus pan-genome is considered to be in an open state, genetically diverse, and with a flexible gene repertoire associated with multiple functions. B. roseus contained genes encoding all enzymes of the Calvin–Benson cycle and phototrophic systems with carotenoids synthesizing genes and possesses complete genes for nitrogen fixing and denitrification. B. roseus S12-14-2T also contains genes for sulfur oxidation and the essential genes encoding for the sulfonate transport system. Moreover, strain S12-14-2T contains all the necessary genes for phosphonate degradation and phosphate biosynthesis. The physiological characteristics and comparative genome analyses of B. roseus S12-14-2T help us to understand the metabolism and evolutionary features of the genus Bradyrhizobium and provide understanding of this microorganism and a new genetic framework for future studies.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary material.

Author contributions

NZ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing – original draft. C-ZJ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing – original draft. YZ: Data curation, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft. TL: Data curation, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft. F-JJ: Data curation, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft. H-GL: Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. LJ: Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by the Korea Environment Industry and Technology Institute (KEITI) through a project to develop new, eco-friendly materials and processing technology derived from wildlife, the Korea Ministry of Environment (MOE), grant number 2021003240004, and the Korea Research Institute of Bioscience and Biotechnology (KRIBB) Research Initiative Program (KGM5252322).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2023.1295854/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

- ^ http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/COG/

- ^ https://antismash.secondarymetabolites.org

- ^ http://enve-omics.ce.gatech.edu/aai/

References

Acker, M., Hogle, S. L., Berube, P. M., Hackl, T., Coe, A., Stepanauskas, R., et al. (2022). Phosphonate production by marine microbes: Exploring new sources and potential function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 119:e2113386119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2113386119

Avontuur, J. R., Palmer, M., Beukes, C. W., Chan, W. Y., Tasiya, T., Van Zyl, E., et al. (2022). Bradyrhizobium altum sp. nov., Bradyrhizobium oropedii sp. nov. and Bradyrhizobium acaciae sp. nov. from South Africa show locally restricted and pantropical nodA phylogeographic patterns. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 167:107338. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2021.107338

Aziz, R. K., Bartels, D., Best, A. A., DeJongh, M., Disz, T., Edwards, R. A., et al. (2008). The RAST Server: Rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Evol. Biol. 9:75. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-75

Aziz, R. K., Devoid, S., Disz, T., Edwards, R. A., Henry, C. S., Olsen, G. J., et al. (2012). SEED servers: High-performance access to the SEED genomes, annotations, and metabolic models. PLoS One 7:e48053. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048053

Balemi, T., and Negisho, K. (2012). Management of soil phosphorus and plant adaptation mechanisms to phosphorus stress for sustainable crop production: A review. J. Soil Sci. Plant. Nutr. 12, 547–561. doi: 10.4067/s0718-95162012005000015

Bienert, S., Waterhouse, A., de Beer, T. A. P., Tauriello, G., Studer, G., Bordoli, L., et al. (2017). The SWISS-MODEL Repository - new features and functionality. Nucleic Acids. Res. 45, D313–D319. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1132

Bobik, C., Meilhoc, E., and Batut, J. (2006). FixJ: A major regulator of the oxygen limitation response and late symbiotic functions of Sinorhizobium meliloti. J. Bacteriol. 188, 4890–4902. doi: 10.1128/jb.00251-06

Cao, N. D. (2014). Phosphate and potassium solubilizing bacteria from weathered materials of denatured rock Mountain, Ha Tien, Kien Giang Province, Vietnam. Am. J. Life. Sci. 1, 88–92. doi: 10.11648/j.ajls.20130103.12

Chun, J., Oren, A., Ventosa, A., Christensen, H., Arahal, D. R., da Costa, M. S., et al. (2018). Proposed minimal standards for the use of genome data for the taxonomy of prokaryotes. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 68, 461–466. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.002516

Ciufo, S., Kannan, S., Sharma, S., Badretdin, A., Clark, K., Turner, S., et al. (2018). Using average nucleotide identity to improve taxonomic assignments in prokaryotic genomes at the NCBI. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 68, 2386–2392. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.002809

Claassens, R., Venter, S. N., Beukes, C. W., Stępkowski, T., Chan, W. Y., and Steenkamp, E. T. (2023). Bradyrhizobium xenonodulans sp. nov. isolated from nodules of Australian Acacia species invasive to South Africa. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 46:126452. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2023.126452

Coates, J. D., Chakraborty, R., Lack, J. G., O’Connor, S. M., Cole, K. A., Bender, K. S., et al. (2001). Anaerobic benzene oxidation coupled to nitrate reduction in pure culture by two strains of Dechloromonas. Nature 411, 1039–1043. doi: 10.1038/35082545

De Meyer, S. E., Coorevits, A., and Willems, A. (2012). Tardiphaga robiniae gen. nov., sp. nov., a new genus in the family Bradyrhizobiaceae isolated from Robinia pseudoacacia in Flanders (Belgium). Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 35, 205–214. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2012.02.002

Delamuta, J. R. M., Ribeiro, R. A., Ormeño-Orrillo, E., Melo, I. S., Martínez-Romero, E., and Hungria, M. (2013). Polyphasic evidence supporting the reclassification of Bradyrhizobium japonicum group Ia strains as Bradyrhizobium diazoefficiens sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 63, 3342–3351. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.049130-0

Delmont, T. O., and Eren, A. M. (2018). Linking pangenomes and metagenomes: The Prochlorococcus metapangenome. PeerJ 6:e4320. doi: 10.7717/peerj.4320

Dos Santos, P. C., Fang, Z., Mason, S. W., Setubal, J. C., and Dixon, R. (2012). Distribution of nitrogen fixation and nitrogenase-like sequences amongst microbial genomes. BMC Genomics 13:162. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-162

Duran, D., Rey, L., Mayo, J., Zuniga-Davila, D., Imperial, J., Ruiz-Argüeso, T., et al. (2014). Bradyrhizobium paxllaeri sp. nov. and Bradyrhizobium icense sp. nov., nitrogen-fixing rhizobial symbionts of Lima bean (Phaseolus lunatus L.) in Peru. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 64, 2072–2078. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.060426-0

Eichhorn, E., van der Ploeg, J. R., Kertesz, M. A., and Leisinger, T. (1997). Characterization of α-ketoglutarate-dependent taurine dioxygenase from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 23031–23036. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.37.23031

Eichhorn, E., van der Ploeg, J. R., and Leisinger, T. (1999). Characterization of a two-component alkanesulfonate monooxygenase from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 26639–26646. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.38.26639

Ellis, H. R. (2011). Mechanism for sulfur acquisition by the alkanesulfonate monooxygenase system. Bioorg. Chem. 39, 178–184. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2011.08.001

Ferrieres, L., Francez-Charlot, A., Gouzy, J., Rouille, S., and Kahn, D. (2004). Fix-regulated genes evolved through promoter duplication in Sinorhizobium meliloti. Microbiology 150, 2335–2345. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27081-0

Gao, Y., Lesven, L., Gillan, D., Sabbe, K., Billon, G., Galan, S. D., et al. (2009). Geochemical behavior of trace elements in sub-tidal marine sediment of the Belgian coast. Mar. Chem 117, 88–96. doi: 10.1016/j.marchem.2009.05.002

Germano, M. G., Menna, P., Mostasso, F. L., and Hungria, M. (2006). RFLP analysis of the rRNA operon of a Brazilian collection of bradyrhizobial strains from 33 legume species. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 56, 217–229. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.02917-0

Gnat, S., Małek, W., Ole´nska, E., Wdowiak-Wróbel, S., Kalita, M., Rogalski, J., et al. (2016). Multilocus sequence analysis supports the taxonomic position of Astragalus glycyphyllos symbionts based on DNA–DNA hybridization. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 66, 1906–1912. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.000862

Gogoi, N., Baruah, K. K., Meena, R. S., Das, A., Yadav, G. S., and Lal, R. (eds) (2018). “Grain legumes: Impact on soil health and agroecosystem,” in Legumes for Soil Health and Sustainable Management, ed. R. S. Meena (Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd), 511–539. doi: 10.1007/978-981-13-0253-4_16

Goris, J., Konstantinidis, K. T., Klappenbach, J. A., Coenye, T., Vandamme, P., and Tiedje, J. M. (2007). DNA-DNA hybridization values and their relationship to whole-genome sequence similarities. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 57, 81–91. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.64483-0

Gregor, J., and Klug, G. (1999). Regulation of bacterial photosynthesis genes by oxygen and light. FEMS. Microbiol. Lett. 179, 1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb08700.x

Hall, T. A. (1999). BioEdit: A user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucl. Acids. Symp. Ser. 41, 95–98. doi: 10.1021/bk-1999-0734.ch008

Hata, S., Kojima, S., Tsuda, R., Kawajiri, N., Kouchi, H., Suzuki, T., et al. (2023). Characterization of photosynthetic Bradyrhizobium sp. strain SSBR45 isolated from the root nodules of Aeschynomene indica. Plant Signal. Behav. 18:2184907. doi: 10.1080/15592324.2023.2184907

Horsman, G. P., and Zechel, D. L. (2017). Phosphonate biochemistry. Chem. Rev. 117, 5704–5783. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00536

Hummerjohann, J., Küttel, E., Quadroni, M., Ragaller, J., Leisinger, T., and Kertes, M. A. (1998). Regulation of the sulfate starvation response in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Role of cysteine biosynthetic intermediates. Microbiology 144, 1375–1386. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-5-1375

Hungria, M., Menna, P., and Delamuta, J. R. M. (2015). “Bradyrhizobium, the ancestor of all rhizobia: Phylogeny of housekeeping and nitrogen-fixation genes,” in Biological Nitrogen Fixation, ed. F. Bruijn (New Jersey, NJ: Wiley, Sons, Inc), 191–202. doi: 10.1002/9781119053095.ch18

Igarashi, N., Harada, J., Nagashima, S., Matsuura, K., Shimada, K., and Nagashima, K. V. (2001). Horizontal transfer of the photosynthesis gene cluster and operon rearrangement in purple bacteria. J. Mol. Evol. 52, 333–341. doi: 10.1007/s002390010163

Jensen, E. S., and Hauggaard-Nielsen, H. (2003). How can increased use of biological N2 fixation in agriculture benefit the environment? Plant Soil 252, 177–186. doi: 10.1023/A:1024189029226

Jiang, Y. H., Wang, D. Y., and Wen, J. F. (2012). The independent prokaryotic origins of eukaryotic fructose-1, 6-bisphosphatase and sedoheptulose-1, 7-bisphosphatase and the implications of their origins for the evolution of eukaryotic Calvin cycle. BMC Evol. Biol. 12:208. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-12-208

Jin, C. Z., Jin, L., Liu, M. J., Lee, J. M., Park, D. J., and Kim, C. J. (2022a). Solihabitans fulvus gen. nov., sp. nov., a member of the family Pseudonocardiaceae isolated from soil. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 72:005110. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.005110

Jin, C. Z., Wu, X. W., Zhuo, Y., Yang, Y., Li, T. H., and Jin, F. J. (2022b). Genomic insights into a free-living, nitrogen-fixing but non nodulating novel species of Bradyrhizobium sediminis from freshwater sediment: Three isolates with the smallest genome within the genus Bradyrhizobium. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 45:126353. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2022.126353

Jin, L., Jin, C. Z., Lee, H. G., and Lee, C. S. (2021). Genomic insights into denitrifying methane-oxidizing bacteria Gemmobacter fulva sp. nov., isolated from an Anabaena culture. Microorganisms. 9:2423. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms9122423

Jin, L., Ko, S. R., Jin, C. Z., Jin, F. J., Li, T. H., and Ahn, C. Y. (2019). Description of novel members of the family Sphingomonadaceae: Aquisediminimonas profunda gen. nov., sp. nov., and Aquisediminimonas sediminicola sp. nov., isolated from freshwater sediment. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 69, 2179–2186. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.003347

Jones, F. P., Clark, I. M., King, R., Shaw, L. J., Woodward, M. J., and Hirsch, P. R. (2016). Novel European free-living, non-diazotrophic Bradyrhizobium isolates from contrasting soils that lack nodulation and nitrogen fixation genes - a genome comparison. Sci. Rep. 6:25858. doi: 10.1038/srep25858

Jordan, D. C. (1982). NOTES: Transfer of Rhizobium japonicum Buchanan 1980 to Bradyrhizobium gen. nov., a genus of slow-growing, root nodule bacteria from leguminous plants. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 32, 136–139. doi: 10.1099/00207713-32-1-136

Kaneko, T., Nakamura, Y., Sato, S., Minamisawa, K., Uchiumi, T., and Sasamoto, S. (2002). Complete genomic sequence of nitrogen-fixing symbiotic bacterium Bradyrhizobium japonicum USDA110. DNA Res. 9, 189–197. doi: 10.1093/dnares/9.6.189

Kertesz, M. A. (2000). Riding the sulfur cycle–metabolism of sulfonates and sulfate esters in Gram-negative bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 24, 135–175. doi: 10.1016/S0168-6445(99)00033-9

Klepa, M. S., Helene, L. C. F., O´ Hara, G., and Hungria, M. (2022). Bradyrhizobium cenepequi sp. nov., Bradyrhizobium semiaridum sp. nov., Bradyrhizobium hereditatis sp. nov. and Bradyrhizobium australafricanum sp. nov., symbionts of different leguminous plants of Western Australia and South Africa and definition of three novel symbiovars. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 72:005446. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.005446

Konstantinidis, K. T., Rosselló-Móra, R., and Amann, R. (2017). Uncultivated microbes in need of their own taxonomy. ISME J. 11, 2399–2406. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2017.113

Konstantinidis, K. T., and Tiedje, J. M. (2005). Genomic insights that advance the species definition for prokaryotes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102, 2567–2572. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409727102

Kumar, S., Stecher, G., and Tamura, K. (2016). MEGA7: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 33, 1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054

Ladha, J. K., and So, R. B. (1994). Numerical taxonomy of photosynthetic rhizobia nodulating Aeschynomene species. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 44, 62–73. doi: 10.1099/00207713-44-1-62

Lafay, B., Coquery, E., and Oger, P. M. (2023). Bradyrhizobium commune sp. nov., isolated from nodules of a wide range of native legumes across the Australian continent. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 73:005971. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.005971

Li, S. H., Guo, W., and Mitchell, B. (2011). Evaluation of water quality and management of Hongze Lake and Gaoyou Lake along the Grand Canal in Eastern China. Environ. Monit. Assess. 176, 373–384. doi: 10.1007/s10661-010-1590-5

Li, T. H., Zhuo, Y., Jin, C. Z., Wu, X. W., Ko, S. R., Jin, F. J., et al. (2020). Genomic insights into a novel species Rhodoferax aquaticus sp. nov., isolated from freshwater. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 70, 4653–4660. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.004325

Lindström, K., Murwira, M., Willems, A., and Altier, N. (2010). The biodiversity of beneficial microbe-host mutualism: The case of rhizobia. Res. Microbiol. 161, 453–463. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2010.05.005

Luo, C., Rodriguez-R, L. M., and Konstantinidis, K. T. (2014). MyTaxa: An advanced taxonomic classifier for genomic and metagenomic sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 42:e73. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku169

Luo, F., Gitiafroz, R., Devine, C. E., Gong, Y., Hug, L. A., Raskin, L., et al. (2014). Metatranscriptome of an anaerobic benzene-degrading, nitrate reducing enrichment culture reveals involvement of carboxylation in benzene ring activation. Appl. Environ. Microb. 80, 4095–4107. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00717-14

Martens, M., Dawyndt, P., Coopman, R., Gillis, M., De Vos, P., and Willems, A. (2008). Advantages of multilocus sequence analysis for taxonomic studies: A case study using 10 housekeeping genes in the genus Ensifer (including former Sinorhizobium). Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 58, 200–214. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.65392-0

Meena, R. S., Das, A., Yadav, G. S., and Lal, R. (eds) (2018). Legumes for Soil Health and Sustainable Management. Singapore: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-981-13-0253-4_13

Meier-Kolthoff, J. P., Auch, A. F., Klenk, H. P., and Göker, M. (2013). Genome sequence-based species delimitation with confidence intervals and improved distance functions. BMC Bioinformatics 14:60. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-14-60

Meilhoc, E., Cam, Y., Skapski, A., and Bruand, C. (2010). The response to nitric oxide of the nitrogen-fixing symbiont Sinorhizobium meliloti. Mol. Plant. Microbe Interact. 23, 748–759. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-23-6-0748

Menna, P., Barcellos, F. G., and Hungria, M. (2009). Phylogeny and taxonomy of a diverse collection of Bradyrhizobium strains based on multilocus sequence analysis of the 16S rRNA gene, ITS region and glnII, recA, atpD and dnaK genes. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 59, 2934–2950. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.009779-0

Metcalf, W. W., and Van Der Donk, W. A. (2009). Biosynthesis of phosphonic and phosphinic acid natural products. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 78, 65–94. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.091707.100215

Moro, H., Park, H. D., and Kunito, T. (2021). Organic phosphorus substantially contributes to crop plant nutrition in soils with low phosphorus availability. Agronomy 11:903. doi: 10.3390/agronomy11050903

Nath, D., Maurya, B. R., and Meena, V. S. (2017). Documentation of five potassium- and phosphorus-solubilizing bacteria for their K and P-solubilization ability from various minerals. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 10, 174–181. doi: 10.1016/j.bcab.2017.03.007

Nordling, M., Young, S., Karlsson, B. G., and Lundberg, L. G. (1990). The structural gene for cytochrome c551 from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. The nucleotide sequence shows a location downstream of the nitrite reductase gene. FEBS Lett. 259, 230–232. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80015-B

Okubo, T., Tsukui, T., Maita, H., Okamoto, S., Oshima, K., Fujisawa, T., et al. (2012). Complete genome sequence of Bradyrhizobium sp. S23321: Insights into symbiosis evolution in soil oligotrophs. Microbes Environ. 27, 306–315. doi: 10.1264/jsme2.ME1132

Ormeño-Orrillo, E., and Martínez-Romero, E. (2019). A Genomotaxonomy view of the Bradyrhizobium Genus. Front. Microbiol. 10:1334. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01334

Parker, M. A. (2015). The spread of Bradyrhizobium lineages across host legume clades: From Abarema to Zygia. Microb. Ecol. 69, 630–640. doi: 10.1007/s00248-014-0503-5

Pearson, I. V., Page, M. D., van Spanning, R. J., and Ferguson, S. J. (2003). A mutant of Paracoccus denitrificans with disrupted genes coding for cytochrome c550 and pseudoazurin establishes these two proteins as the in vivo electron donors to cytochrome cd1 nitrite reductase. J. Bacteriol. 185, 6308–6315. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.21.6308-6315.2003

Pérez-Yépez, J., Armas-Capote, N., Velázquez, E., Pérez-Galdona, R., Rivas, R., and León-Barrios, M. (2014). Evaluation of seven housekeeping genes for multilocus sequence analysis of the genus Mesorhizobium: Resolving the taxonomic affiliation of the Cicer canariense rhizobia. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 37, 553–559. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2014.10.003

Quentmeier, A., Hellwig, P., Bardischewsky, F., Wichmann, R., and Friedrich, C. G. (2004). Sulfide dehydrogenase activity of the monomeric flavoprotein SoxF of Paracoccus pantotrophust. Biochemistry 43, 14696–14703. doi: 10.1021/bi048568y

Remigi, P., Zhu, J., Young, J. P. W., and Masson-Boivin, C. (2016). Symbiosis within symbiosis: Evolving nitrogen-fixing legume symbionts. Trends Microbiol. 24, 63–75. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2015.10.007

Richardson, D. J. (2000). Bacterial respiration: A flexible process for a changing environment. Microbiology 146, 551–571. doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-3-551

Richter, M., and Rossello-Mora, R. (2009). Shifting the genomic gold standard for the prokaryotic species definition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106, 19126–19131. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906412106

Rinaldo, S., and Cutruzzola, F. (2007). Nitrite reductases in denitrification. Biol. Nitrogen Cycle 37, 37–55. doi: 10.1016/B978-044452857-5.50004-7

Rivas, R., Martens, M., de Lajudie, P., and Willems, A. (2009). Multilocus sequence analysis of the genus Bradyrhizobium. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 32, 101–110. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2008.12.005

Rott, E., Steinmetz, H., and Metzger, J. W. (2018). Organophosphonates: A review on environmental relevance, biodegradability and removal in wastewater treatment plants. Sci. Total Environ. 615, 1176–1191. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.09.223

Salminen, S. O., and Streeter, J. G. (1987). Uptake and metabolism of carbohydrates by Bradyrhizobium japonicum bacteroids. Plant Physiol. 83, 535–540. doi: 10.1104/pp.83.3.535

Simon, J., and Klotz, M. G. (2013). Diversity and evolution of bioenergetic systems involved in microbial nitrogen compound transformations. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1827, 114–135. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2012.07.005

Sosa, O. A., Repeta, D. J., DeLong, E. F., Ashkezari, M. D., and Karl, D. M. (2019). Phosphate-limited ocean regions select for bacterial populations enriched in the carbon-phosphorus lyase pathway for phosphonate degradation. Environ. Microbiol. 21, 2402–2414. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.14628

Sprent, J. I., Ardley, J., and James, E. K. (2017). Biogeography of nodulated legumes and their nitrogen-fixing symbionts. New Phytol. 215, 40–56. doi: 10.1111/nph.14474

Stacey, G., Sanjuan, J., Luka, S., Dockendorff, T., and Carlson, R. W. (1995). Signal exchange in the Bradyrhizobium–soybean symbiosis. Soil Biol. Biochem. 27, 473–483. doi: 10.1016/0038-0717(95)98622-u

Tang, J., Bromfield, E. S. P., Rodrigue, N., Cloutier, S., and Tambong, J. T. (2012). Microevolution of symbiotic Bradyrhizobium populations associated with soybeans in east North America. Ecol. Evol. 2, 2943–2961. doi: 10.1002/ece3.404

Tao, J., Wang, S., Liao, T., and Luo, H. (2021). Evolutionary origin and ecological implication of a unique nif island in free-living Bradyrhizobium lineages. ISME J. 15, 3195–3206. doi: 10.1038/s41396-021-01002-z

Tatusov, R. L., Fedorova, N. D., Jackson, J. D., Jacobs, A. R., Kiryutin, B., Koonin, E. V., et al. (2003). The COG database: An updated version includes eukaryotes. BMC Bioinformatics 4:41. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-4-41

Tatusov, R. L., Koonin, E. V., and Lipman, D. J. (1997). A genomic perspective on protein families. Science 278, 631–637. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5338.631

Thompson, J. D., Gibson, T. J., Plewniak, F., Jeanmougin, F., and Higgins, D. G. (1997). The Clustal X windows interface: Flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 24, 4876–4882. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876

Van Der Ploeg, J. R., Barone, M., and Leisinger, T. (2001a). Expression of the Bacillus subtilis sulphonate–sulphur utilization genes is regulated at the levels of transcription initiation and termination. Mol. Microbiol. 39, 1356–1365. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02327.x

Van Der Ploeg, J. R., Eichhorn, E., and Leisinger, T. (2001b). Sulfonate-sulfur metabolism and its regulation in Escherichia coli. Arch. Microbiol. 176, 1–8. doi: 10.1007/s002030100298

Van Rhijn, P., and Vanderleyden, J. (1995). The Rhizobium-plant symbiosis. Microbiol. Rev. 59, 124–142. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.1.124-142.1995

VanInsberghe, D., Maas, K. R., Cardenas, E., Strachan, C. R., Hallam, S. J., and Mohn, W. W. (2015). Non-symbiotic Bradyrhizobium ecotypes dominate North American forest soils. ISME J. 9, 2435–2441. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2015.54

Villarreal-Chiu, J. F., Quinn, J. P., and McGrath, J. W. (2012). The genes and enzymes of phosphonate metabolism by bacteria, and their distribution in the marine environment. Front. Microbiol. 3:19. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00019

Waterhouse, A., Bertoni, M., Bienert, S., Studer, G., Tauriello, G., Gumienny, R., et al. (2018). SWISS-MODEL: Homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, W296–W303. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky427

Weisburg, W. G., Barns, S. M., Pelletier, D. A., and Lane, D. J. (1991). 16S ribosomal DNA amplification for phylogenetic study. J. Bacteriol. 173, 697–703. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.2.697-703.1991

Wu, Y. S., Huang, T. Y., Zhang, J. G., Tian, Y. J., Pang, Y., and Xu, Q. J. (2023). Distribution characteristics and risk assessment of PPCPs in surface water and sediments of lakes in the lower reaches of the Huaihe River. Huan Jing Ke Xue 44, 3217–3227. doi: 10.13227/j.hjkx.202207169

Yao, Y., Wang, P., Wang, C., Hou, J., Miao, L., Yuan, Y., et al. (2016). Assessment of mobilization of labile phosphorus and iron across sediment-water interface in a shallow lake (Hongze) based on in situ high-resolution measurement. Environ. Pollut. 219, 873–882. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2016.08.054

Yoon, S. H., Ha, S. M., Kwon, S., Lim, J., Kim, Y., Seo, H., et al. (2017). Introducing EzBio-Cloud: A taxonomically united database of 16S rRNA gene sequences and whole-genome assemblies. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 67, 1613–1617. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.001755

Zhang, J., Wang, N., Li, S., Peng, S., Andrews, M., Zhang, X., et al. (2023). Bradyrhizobium zhengyangense sp. nov., isype strains of the most closely related species of isolated from effective nodules of Arachis hypogaea L. in central China. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol 73:005723. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.005723

Keywords: Bradyrhizobium, Bradyrhizobium roseus, free-living, non-symbiotic, phosphonate, freshwater sediment

Citation: Zhang N, Jin C-Z, Zhuo Y, Li T, Jin F-J, Lee H-G and Jin L (2023) Genetic diversity into a novel free-living species of Bradyrhizobium from contaminated freshwater sediment. Front. Microbiol. 14:1295854. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1295854

Received: 17 September 2023; Accepted: 30 October 2023;

Published: 18 November 2023.

Edited by:

Adolphe Zeze, Félix Houphouët-Boigny National Polytechnic Institute, Côte d’IvoireReviewed by:

Esther Menendez, University of Salamanca, SpainClémence Chaintreuil, Institut de Recherche pour le Développement, Republic of Congo

Copyright © 2023 Zhang, Jin, Zhuo, Li, Jin, Lee and Jin. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Long Jin, aXNhY2NraW1AYWx1bW5pLmthaXN0LmFjLmty; Hyung-Gwan Lee, dHJ1c3RpbkBrcmliYi5yZS5rcg==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Naxue Zhang

Naxue Zhang Chun-Zhi Jin

Chun-Zhi Jin Ye Zhuo2,3

Ye Zhuo2,3 Feng-Jie Jin

Feng-Jie Jin Hyung-Gwan Lee

Hyung-Gwan Lee Long Jin

Long Jin