95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Microbiol. , 15 February 2023

Sec. Aquatic Microbiology

Volume 14 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2023.1102909

This article is part of the Research Topic Impact of Global Change on Marine Microbial Ecology View all 6 articles

He Li1

He Li1 Kunshan Gao1,2*

Kunshan Gao1,2*Effects of changed levels of dissolved O2 and CO2 on marine primary producers are of general concern with respect to ecological effects of ongoing ocean deoxygenation and acidification as well as upwelled seawaters. We investigated the response of the diazotroph Trichodesmium erythraeum IMS 101 after it had acclimated to lowered pO2 (~60 μM O2) and/or elevated pCO2 levels (HC, ~32 μM CO2) for about 20 generations. Our results showed that reduced O2 levels decreased dark respiration significantly, and increased the net photosynthetic rate by 66 and 89% under the ambient (AC, ~13 μM CO2) and the HC, respectively. The reduced pO2 enhanced the N2 fixation rate by ~139% under AC and only by 44% under HC, respectively. The N2 fixation quotient, the ratio of N2 fixed per O2 evolved, increased by 143% when pO2 decreased by 75% under the elevated pCO2. Meanwhile, particulate organic carbon and nitrogen quota increased simultaneously under reduced O2 levels, regardless of the pCO2 treatments. Nevertheless, changed levels of O2 and CO2 did not bring about significant changes in the specific growth rate of the diazotroph. Such inconsistency was attributed to the daytime positive and nighttime negative effects of both lowered pO2 and elevated pCO2 on the energy supply for growth. Our results suggest that Trichodesmium decrease its dark respiration by 5% and increase its N2-fixation by 49% and N2-fixation quotient by 30% under future ocean deoxygenation and acidification with 16% decline of pO2 and 138% rise of pCO2 by the end of this century.

Biological N2 fixation by marine diazotrophs is an important source of “new” usable nitrogen to phytoplankton in oligotrophic surface waters (Karl et al., 1997; Bergman et al., 2013). The N2-fixing cyanobacteria, Trichodesmium spp., contribute about half of the current estimate of global annual marine N2 fixation, playing a pivotal role in global biogeochemical N/C cycles (Mahaffey et al., 2005; Sohm et al., 2011). The nitrogenase enzyme encoded by the nifHDK genes is critically sensitive to and can be inactivated by oxygen (O2) (Staal et al., 2007; Hutchins and Sañudo-Wilhelmy, 2022). Most cyanobacterial N2-fixers can avoid O2 damage via temporal (fixing N2 during night) or spatial (using heterocyst) strategies. However, Trichodesmium spp. do not possess such contrivances to avoid photosynthetically evolved O2, since all cells of the trichomes have PSII (Lin et al., 1998; Bergman et al., 2013). It is known that Trichodesmium cells down-regulate its photosynthesis during midday to protect nitrogenase using various physiological pathways (e.g., the Mehler reaction, respiration and flavoprotein-mediated O2 uptake) to sequestrate O2 under light (Berman-Frank et al., 2001; Gallon, 2001; Milligan et al., 2007), which is considered as a metabolic strategy for the O2-sensitive diazotroph (Luo et al., 2022).

Dissolved O2 (DO) levels in the oceans have been declining due to global warming, and are expected to further decline during the 21th century (Schmidtko et al., 2017; Breitburg et al., 2018). Rising global temperatures decrease the solubility of O2, enhancing stratification (hindering ventilation to deeper layers) of the upper mixing layers and increasing biological respiration, thus ultimately reduce DO in surface and subsurface oceans (Carstensen et al., 2014). Consequently, the oxygen-minimum zones (OMZ) have expanded horizontally and vertically along with progressive ocean deoxygenation (Stramma et al., 2008; Schmidtko et al., 2017). On the other hand, internal O2 concentrations of Trichodesmium colonies or blooms ranged from 0 to 500 μM during dark and/or high-light periods, which is supposed to affect the nitrogenase activity (Paerl and Bebout, 1992; Eichner et al., 2019). Light stimulation of nitrogenase activity is most obvious at low O2 concentrations, while it becomes gradually less important with increased levels of O2 in Trichodesmium IMS 101 (Staal et al., 2007). Therefore, it is likely that the marine diazotrophs including Trichodesmium would benefit from ocean deoxygenation.

On the other hand, ocean acidification (OA) induced by continuous dissolution of anthropogenically emitted CO2 into seawater is known to affect various phytoplankton species and ecological processes (Gao et al., 2020), which show positive and/or negative responses to OA under different environmental conditions (Boyd et al., 2018). Temperature, light, nutrients and UV radiation are known to modulate the influences of elevated pCO2, resulting in negative in oligotrophic waters but in neutral or positive effects in nutrients-replete waters (Gao et al., 2022). Most cyanobacteria and microalgae, including Trichodesmium, have evolved efficient CO2-concentrating mechanisms (CCMs) that actively uptake CO2 and bicarbonate to increase the level of intracellular dissolved inorganic carbon for efficient photosynthesis (Giordano et al., 2005). Therefore, the energy saved by the downregulation of CCMs under elevated pCO2 is expected to be reallocated to other metabolic processes (Kranz et al., 2010). Differential responses have also been documented in Trichodesmium. OA has been shown to promote the N2 fixation and growth of Trichodesmium (Hutchins et al., 2007; Levitan et al., 2007; Garcia et al., 2011; Hutchins et al., 2013). However, it was also shown to result in insignificant or even negative effects on Trichodesmium, and the negative effects were more obvious under iron limitation (Shi et al., 2012; Hong et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2019). It was suggested that the energy saved from downregulation of CCMs under elevated pCO2 is not enough for the energy demand of increased N2-fixation rates in Trichodesmium under OA conditions (Luo et al., 2019). While these disputable findings need to be mechanistically reconciled, effects of multiple drivers on the marine diazotroph should also be examined (Wake, 2019). Recently, it was shown that reduced O2 availability modulated the effects of elevated pCO2 on a diatom (Sun et al., 2022). Combined effects of ocean deoxygenation and acidification on Trichodesmium has yet to be investigated.

Since levels of pH/pCO2 and O2 in the center of Trichodesmium colonies fluctuate during a diel cycle due to night respiration and daytime photosynthesis (Eichner et al., 2019), its physiological performance can be naturally influenced by the changed levels of both O2 and CO2. In parallel, progressive ocean deoxygenation and acidification are covarying factors that affect marine organisms including the diazotrophs (Staal et al., 2007; Paulmier et al., 2011; Sun et al., 2022). Considering that low levels of O2 can theoretically enhance carboxylation via decreasing oxygenation processes catalyzed by Rubisco and stimulate the activity of nitrogenase, we hypothesize that combination of ocean deoxygenation and acidification can synergistically enhance photosynthetic performance and N2 fixation of Trichodesmium. Hence, we simulated different microenvironments by growing Trichodesmium erythraeum (T. erythraeum) strain IMS 101 under four different pO2/pCO2 combinations (ambient CO2 & ambient O2; ambient CO2 & low O2; high CO2 & ambient O2; high CO2 & low O2) in order to investigate the responses of Trichodesmium. In this work, we found that reduced O2 concentration increased both photosynthetic performance and N2 fixation rate and thus raised the particulate organic carbon and nitrogen even under elevated pCO2 projected for future ocean acidification by the end of this century.

Trichodesmium erythraeum (strain IMS 101), originally isolated from the North Atlantic Ocean (Prufert-Bebout et al., 1993), was grown in YBCII medium without combined N prepared with autoclaved sterilized artificial seawater (Chen et al., 1996). Experiments were conducted in polycarbonate bottles under 160 μmol photons m−2 s−1 of PAR (measured by a Solar light sensor, PMA2100, United States) with a day-night cycle of 12: 12 h at 27 ± 0.5°C in an incubator (HP300G–C, Ruihua, China).

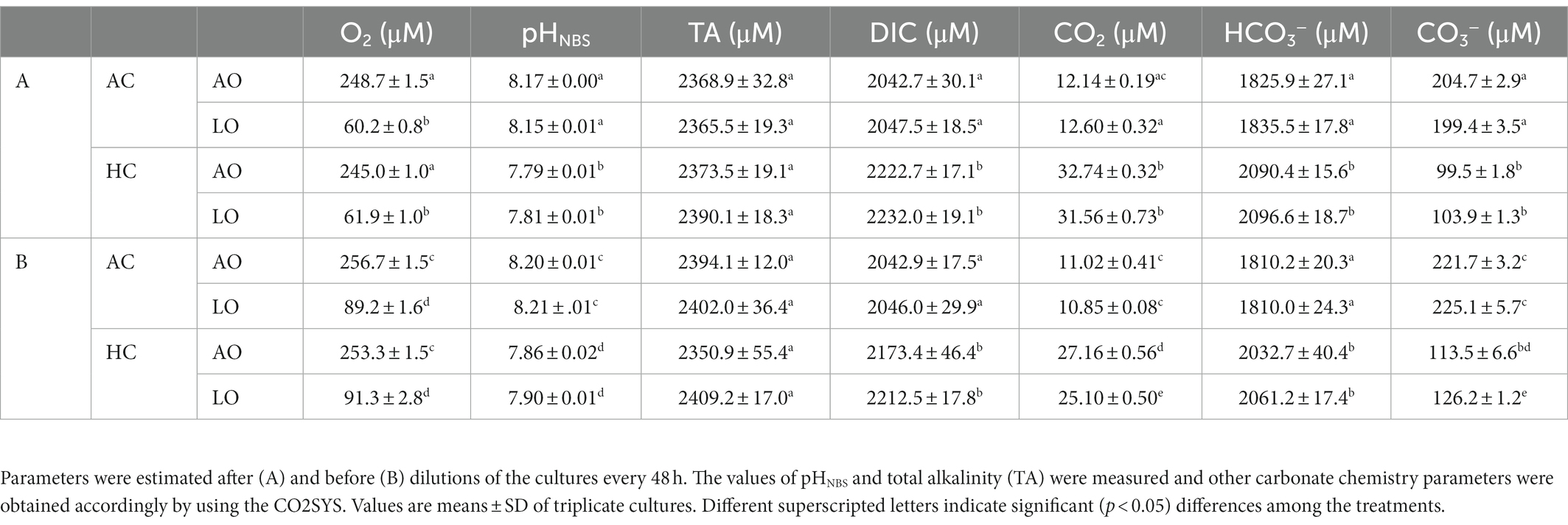

Triplicate experiments were carried out in a four treatments matrix of two levels of CO2 (ambient and high CO2) and two levels of O2 (ambient and low O2), respectively. T. erythraeum cells were maintained in the exponential growth phase by semicontinuous culture (diluted every 48 h). The chlorophyll a (Chl a) concentration was maintained within a range of 0.003–0.015 μg mL−1 (Supplementary Figure S1), so that dissolved O2 and carbonate chemistry in the cultures were little altered. The carbonate chemistry parameters were relatively stable before and after the dilution, the pH variations were less than 0.08 units under either the HC (elevated CO2, 32 μM) or AC (ambient CO2, 12 μM) treatments, along with 12 to 19% decrease of pCO2 before the dilutions, and dissolved O2 concentrations varied less than 10 μM (245–255 μM) and 30 μM (60–90 μM) under AO (ambient O2) and LO (low O2) treatments, respectively (Table 1; Supplementary Figure S2). Prior to dilution, fresh media were prepared with the target O2 and CO2 levels: ambient CO2 & ambient O2 (ACAO), ambient CO2 & low O2 (ACLO,), high CO2 & ambient O2 (HCAO), high CO2 & low O2 (HCLO) (Table 1). A customized CO2/O2 controlling device (CE-100DY, Ruihua, China) was employed to achieve the above O2 and CO2 levels. The bottles were shaken gently every 3 h during the daytime to ensure that the cyanobacterial filaments were in a suspended state.

Table 1. Dissolved O2 concentrations and carbonate chemistry parameters of the culture media during the semi-continuous cultures of Trichodesmium erythraeum IMS101 under the four treatments (ACAO, ~12 μM CO2/~250 μM O2; ACLO, ~12 μM CO2/~60 μM O2; HCAO, ~32 μM CO2/~250 μM O2; HCLO, ~32 μM CO2/~60 μM O2).

The dissolved O2 and pH of seawater were measured before and after dilution every 2 days. The dissolved O2 was measured with a Clark-type oxygen electrode (Hansatech, United Kingdom). The pHNBS was measured using a pH meter, which was three-point calibrated with NBS buffer. Total alkalinity (TA) was measured using the Gran potentiometric titration method (Gao et al., 2018). Dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) and other carbonate chemistry parameters (Table 1) were calculated from pHNBS and TA by using the CO2SYS software (Lewis et al., 1998).

Trichodesmium erythraeum cells were gently filtered onto 25 mm glass-fiber filters (GF/F, Whatman), which was then extracted in pure methanol at 4°C for 24 h for Chl a determination. The extracts were centrifuged at 6000 g for 10 min, and the absorbances of the supernatants at 665 nm and 750 nm were measured using a UV–VIS Spectrophotometer (DU800, Beckman, United States). The Chl a concentration was calculated according to the equations Chl a (μg mL−1) =12.9447 × (A665 − A750) × V1/V2 (Ritchie, 2006), where V1 and V2 represent the 100% methanol volume (mL) and filtered cell volume (mL), respectively. The specific growth rates (μ, d−1) were determined from linear regressions of the natural log of Chl a vs. time during the exponential growth (Yi et al., 2020).

Dark respiration and net photosynthetic oxygen evolution were measured in the middle of the light period within 3 h using a Clarke-type electrode (Hansatech, United Kingdom). Cells were harvested by filtering onto polycarbonate membrane filters (5 μm, Millipore, Germany) under gentle vacuum pressure (<0.01 MPa). These cells were then re-suspended in seawater buffered with 20 mM Tris–HCl with a final Chl a concentration of approximately 0.5 μg mL−1. The pH levels of the Tris buffered-medium were pre-adjusted by adding hydrochloric acid or sodium hydroxide to the same levels of the cultures (pH 7.83 for HC and 8.13 for AC), and the O2 levels were achieved by flushing the medium with pure N2. The resuspended cells were injected into an oxygen electrode vessel with a magnetic stirrer held in a water-jacked chamber (temperature controlled at 27°C) under the same level of light intensity. The respiration rate was estimated in darkness by covering the reaction chamber with aluminum foil. Photosynthetic O2 evolution was determined under growth O2 levels.

N2-fixation rates were determined at the midpoint of the photoperiod with the acetylene reduction assay, assuming a ratio of 4: 1 to convert ethylene production to N2 fixation (Capone, 1993). Although one time point measurement has been able to identify changes of N2-fixation rate under different environmental conditions (Zhang et al., 2019), it may overlook other timepoint values of the N2-fixation during the whole light period. For determination of the N2-fixation rates, 5 ml of sample was added to a 13 mL vial, which was then sealed. After 1 mL of air was extracted from the headspace, 1 ml of acetylene (C2H2) was added to each vial. All replicates were mixed well and incubated for 2 h under the same temperature and light in the incubator as the growth conditions. The ethylene production was measured using a gas chromatograph with a flame ionization detector (Clarus 580, PerkinElmer, United States).

Cell samples for particulate organic carbon (POC) and particulate organic nitrogen (PON) were collected onto pre-combusted (450°C for 6 h) GF/F filters (Whatman), and were stored at −80°C before measuring. Filters were exposed to HCl fumes to remove inorganic carbon and dried at 60°C before analysis with a CHNS elemental analyzer (vario EL cube, Elementar, Germany).

The data were presented as means of three replicates ± SD (n = 3, triplicate independent cultures). One-way ANOVA and Tukey test were performed to analyze the statistical differences among different treatments. Differences were termed significant when p < 0.05. Before performing parametric tests, data were tested for homogeneity of variance (Levene test) and normality (ShapiroWilk test).

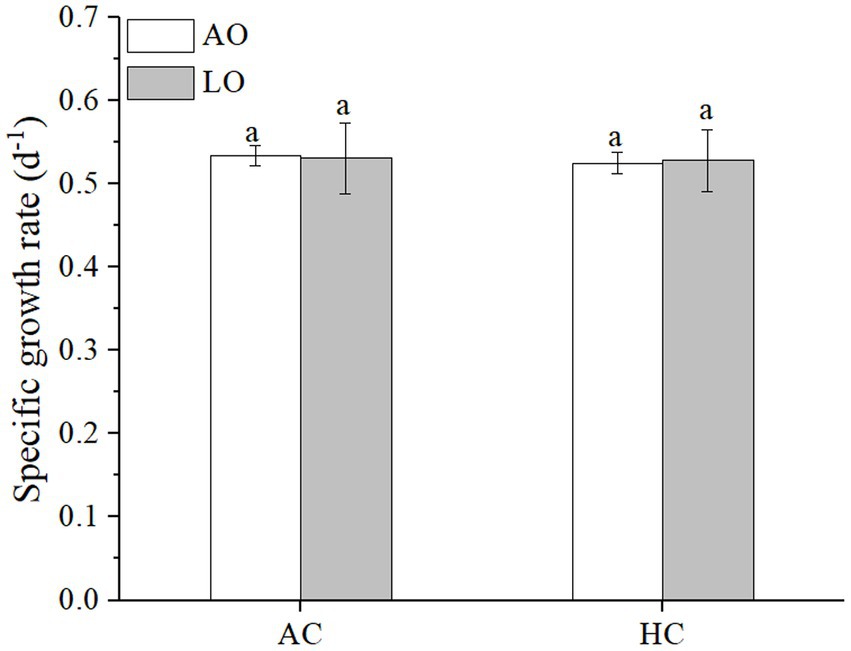

Neither elevated pCO2 (p = 0.9881) nor lowered pO2 (p = 0.6284) significantly affected the specific growth rate of T. erythraeum (Figure 1). The specific growth rates were 0.534 ± 0.012 and 0.531 ± 0.043 d−1 under AC, and were 0.525 ± 0.013 and 0.528 ± 0.038 d−1 under HC, at the levels of ambient and lowered O2, respectively (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The specific growth rates of Trichodesmium. erythraeum IMS101 grown and measured after it acclimated for 16 days (12 generations) to different combinations of pCO2 and pO2 (AO, ~245 μM; LO, ~60 μM; AC, ~12 μM; HC, ~32 μM. LO and HC refer to lowered pO2 and elevated pCO2). The values are indicated as the means ± SD for independent cultures (n = 6) at each treatment. The same letters above the bars indicate no significant (p < 0.05) differences among the treatments.

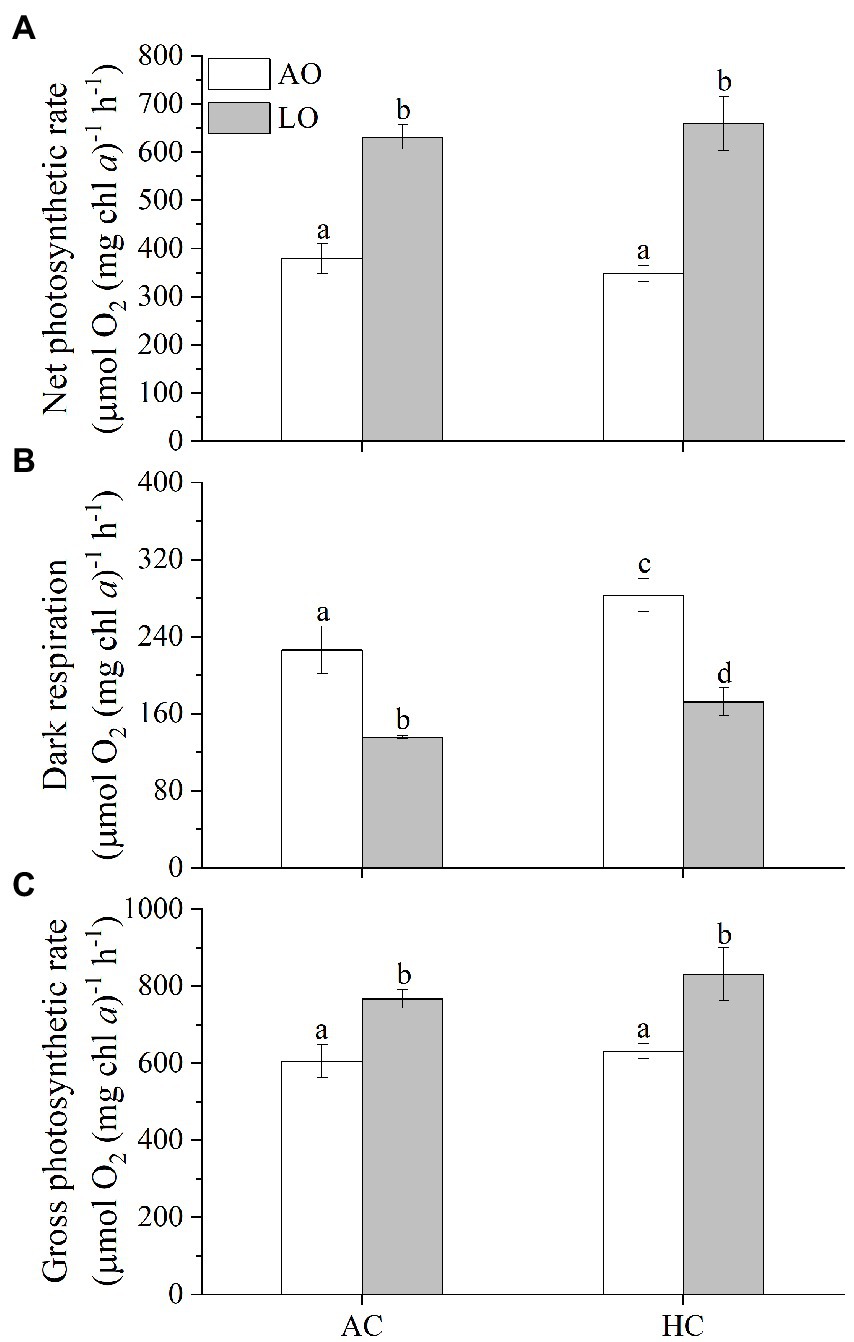

Dark respiration decreased with lowered levels of O2, whereas net and gross photosynthetic rate increased (Figure 2). Reduced O2 levels (from 250 to 60 μM) significantly increased net photosynthetic rate by 66% under AC (631 vs. 379 μmol O2 mg chl a−1 h−1, p < 0.0001) and by 89% under HC conditions (659 vs. 348 μmol O2 mg chl a−1 h−1, p < 0.0001), respectively (Figure 2A). Nevertheless, no significant differences were found in the net photosynthetic rate between the AC and HC treatments (p = 0.9432) (Figure 2A), though the mean net photosynthetic rate of the cells grown under HC was higher by about 4% than that of AC under LO. Decreased O2 levels to 60 μM (by 75%) significantly inhibited dark respiration by 40% under the AC (136 vs. 226 μmol O2 mg chl a−1 h−1, p = 0.0002) and 39% under the HC (172 vs. 283 μmol O2 mg chl a−1 h−1, p < 0.0001), respectively (Figure 2B), reflecting that Trichodesmium would decrease its dark respiration by 9% and increase its net photosynthetic rate by 14% with 16% pO2 decline by the end of this century (Table S1). Meanwhile, the HC-acclimated cells had higher (by 25% at AO and by 27% at LO) dark respiration rate compared to that of AC cells regardless of O2 levels (p = 0.0031 for AO, p = 0.0278 for LO). The reduced O2 levels significantly increased gross photosynthetic rate by 27% (767 vs. 605 μmol O2 mg chl a−1 h−1, p < 0.0019) under AC and by 32% (831 vs. 631 μmol O2 mg chl a−1 h−1, p = 0.0005) under HC, respectively (Figure 2C). Meanwhile, HC treatments increased gross photosynthetic rate by 4% (p = 0.4844) under AO and by 8% (p = 0.1081) under LO compared to the AC-grown cells, though the difference was insignificant.

Figure 2. The rates of net photosynthetic O2 evolution (A), dark respiration (B) and gross photosynthetic O2 evolution (C) in T. erythraeum IMS101 cells after acclimated different levels of pCO2 and pO2 (as shown in Figure 1) for 28–30 days (21–23 generations). Levels of pCO2 and pO2 are the same or within the same ranges as shown in Figure 1. The values are indicated as the means ± SD for triplicate cultures at each treatment. Different letters above the bars indicate significant (p < 0.05) differences among the treatments.

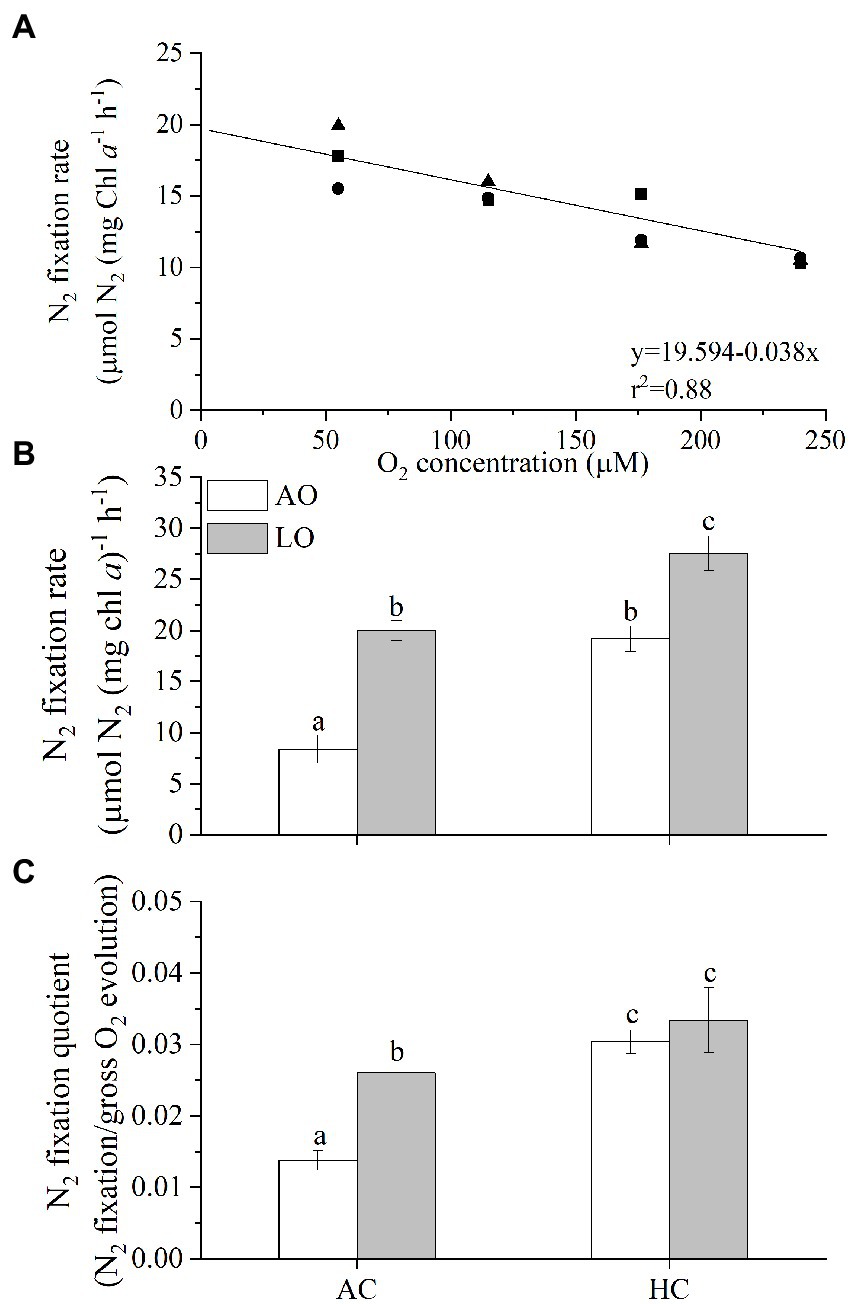

When T. erythraeum cells were grown under different O2 levels, their N2 fixation rates showed a negative relationship with the O2 concentrations (Figure 3A, r2 = 0.88). The N2 fixation rate increased linearly by 9% with each 10% decline in the dissolved O2 concentration. After the Trichodesmium cells acclimated to different levels of O2 and pCO2, lowering DO to about 60 μM increased the Chl a-specific N2 fixation rate by ~139% (20.0 vs. 8.4 μmol N2 mg chl a−1 h−1, p < 0.0001) under AC but only by 44% (27.5 vs. 19.2 μmol N2 mg chl a−1 h−1, p < 0.0001) under the HC conditions (Figure 3B), indicating obvious less enhancement by the reduced O2 treatment under the elevated pCO2. The Trichodesmium cells grown in the HC treatment had higher N2 fixation rates than those grown in the AC cultures regardless of the O2 levels (p < 0.0001 for AO, p = 0.0001 for LO), being increased by 129% under AO and by 38% under LO, respectively. The ratio of N2 fixation to the gross photosynthetic rate, as a proxy of the N2-fixation quotient (NFQ), ranged from 0.014 to 0.033 (mol N2: mol O2) (Figure 3C). The lowered pO2 treatment increased the NFQ by 89% under AC (p = 0.0016) and by only 10% under HC (p = 0.5104), and the elevated pCO2 and low pO2 treatment increased it by 143% compared to ACAO (p < 0.0001). Based on the results in this work, we estimated that Trichodesmium would increase its N2-fixation by 14% and N2-fixation quotient by 19% under future ocean deoxygenation with 16% decline of pO2 till 2,100 under the current pCO2 level (Table S1).

Figure 3. (A) N2-fixation rates of T. erythraeum IMS101 as a function of dissolved O2 concentrations in cultures after the cells acclimated for 48 h, (B) the N2-fixation rates and (C) N2-fixation quotients of T. erythraeum cells after acclimated different levels of O2 and CO2 (see Figure 1) for 32 days (24 generations). Different symbols [panel (A)] represent independent cultures (n = 3). The values in panels (B,C) indicate the means ± SD for triplicate cultures at each treatment. Levels of pCO2 and pO2 are the same or within the same ranges as shown in Figure 1. Different letters above the bars indicate significant (p < 0.05) differences among the treatments.

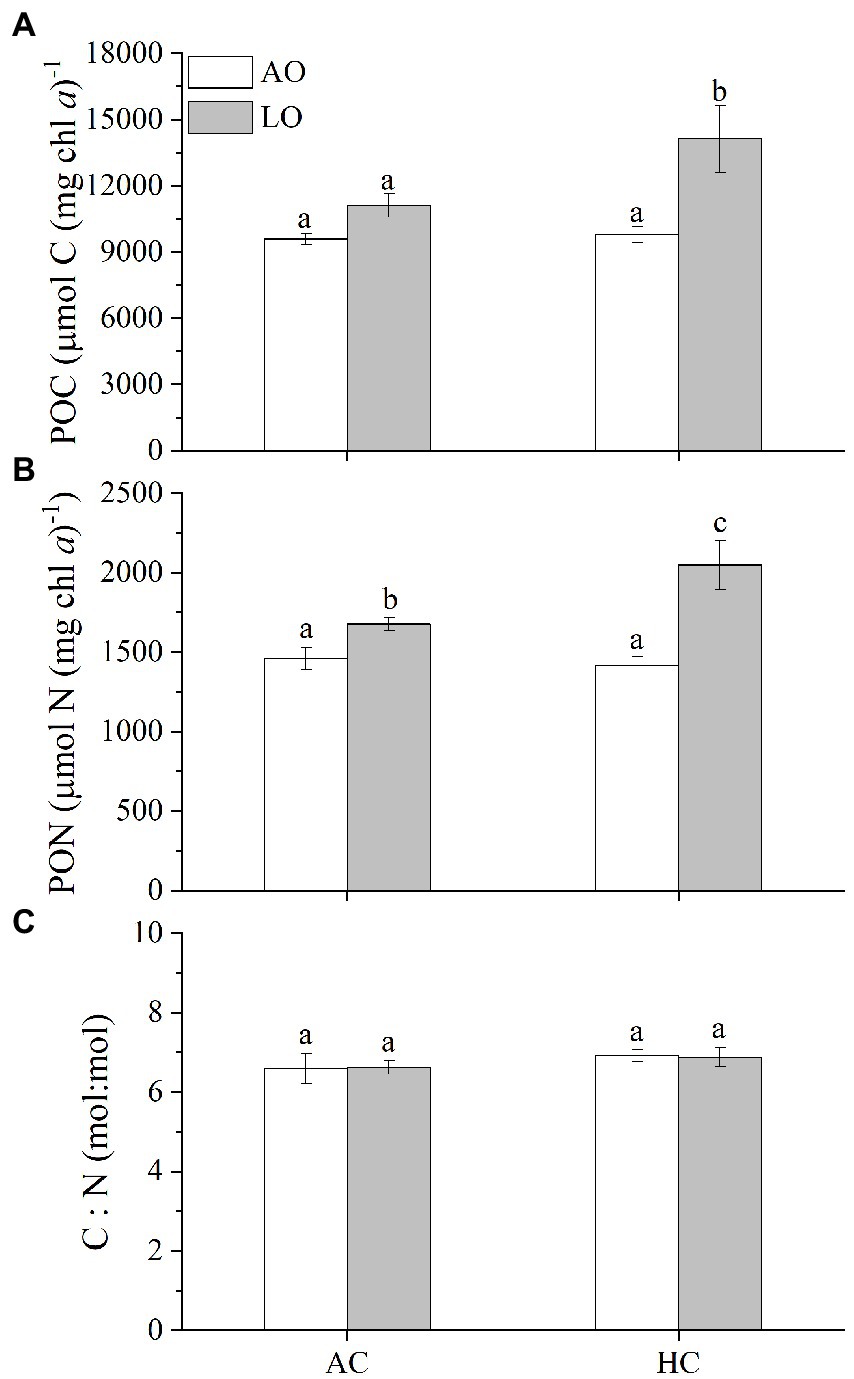

Decreased O2 levels to about 60 μM slightly raised the cellular particulate organic carbon (POC) by 16% (p = 0.0583) and particulate organic nitrogen (PON) by 15% (p = 0.0190) in the T. erythraeum cells ISM 101 grown under the AC (Figures 4A,B). Contrastingly, under the HC conditions, the reduced O2 concentration increased POC by 44% (p = 0.0002) and PON by 45% (p < 0.0001), respectively (Figures 4A,B). Nevertheless, the cellular C:N ratios were about 6.8, being neither affected under the changed levels of pCO2 (p = 0.0796) nor under the reduced levels of pO2 (p = 0.9859) (Figure 4C).

Figure 4. The particulate organic carbon (POC) (A), particulate organic nitrogen (PON) per chl a (B), and C:N ratio (mol: mol) (C) in T. erythraeum IMS101 grown and acclimated under the different levels of O2 and CO2 (see Figure 1) for 36 days (27 generations). The values are indicated as the means ± SD for triplicate cultures at each treatment. Different letters above the bars indicate significant (p < 0.05) differences among the treatments.

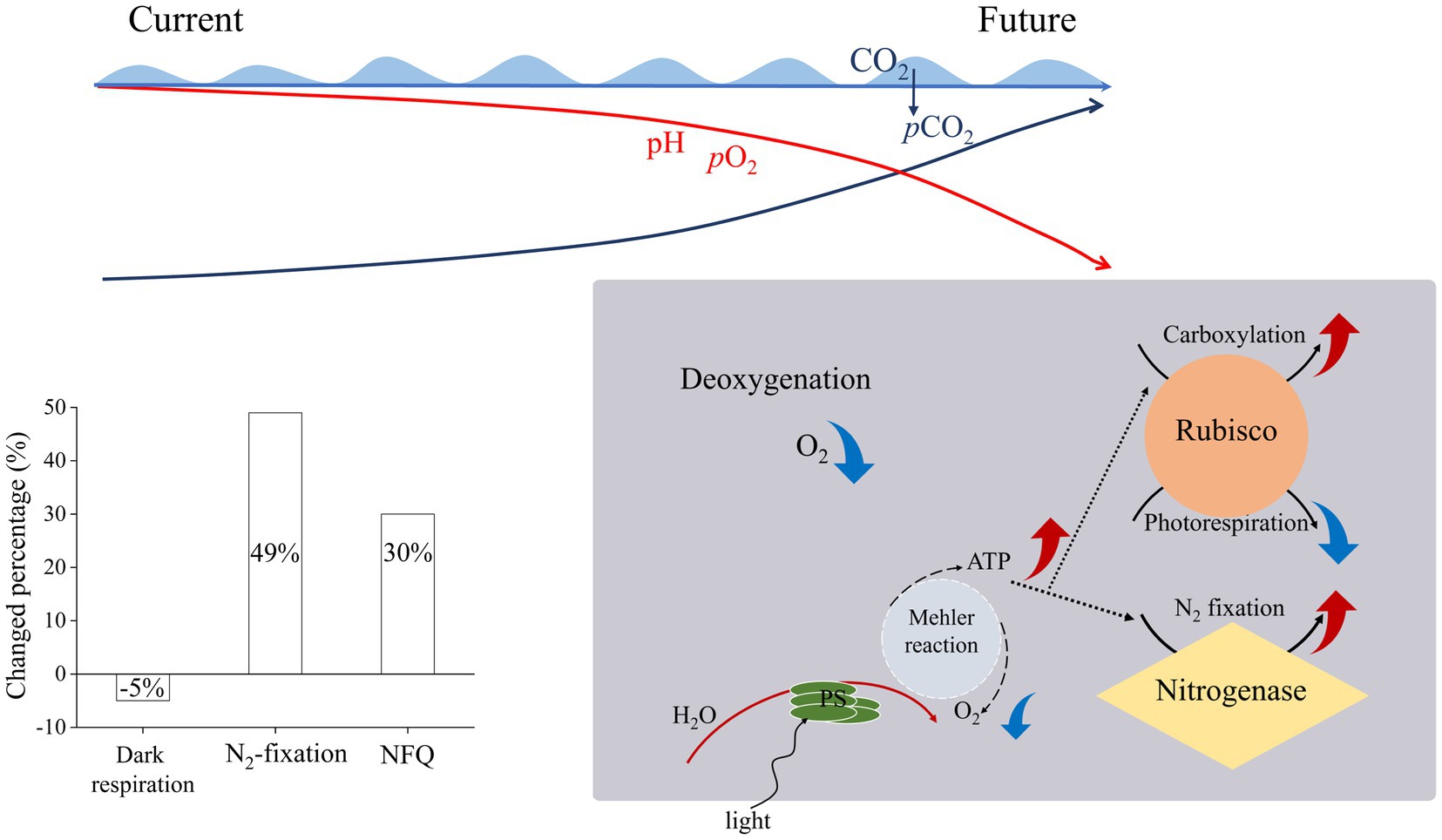

In the present study, the T. erythraeum cells acclimated to lowered pO2 and elevated pCO2 levels showed higher N2-fixation quotient (ratio of N2 fixed to gross O2 production), being increased by 143% (with pO2 declined bys 75%) and by 12% (with pO2 declined by 10%) compared to ambient levels of pO2 and pCO2 (Figure 5). This could be attributed to decreased dark respiration and increased photosynthetic performance as well as increased N2 fixation under the reduced levels of pO2 and to increased rates of dark respiration and N2 fixation under the elevated pCO2 (Figures 2, 3). Although both low pO2 and high pCO2 treatments did not significantly affect the growth rates of T. erythraeum, its cellular particulate organic carbon (POC) and nitrogen (PON) contents increased under the lowered O2 and elevated pCO2 levels. Our data provided the experimental evidence that reduced O2 levels increased N2 fixation and photosynthetic performance by stimulating the activities of nitrogenase and Rubisco (Figure 5), enhancing POC and PON production in anoxic and/or hypoxic environments, where lowered levels of O2 and pH (high pCO2) are covarying drivers.

Figure 5. Illustration of the effects of ocean deoxygenation and acidification on Trichodesmium erythraeum, which is suggested to decrease its dark respiration by 5% and to increase its N2-fixation by 49% and N2-fixation quotient (NFQ, ratios of N2 fixed per C fixed) by 30% with 16% decline of pO2 and 138% rise of pCO2 by the end of this century.

Nitrogenase, the key enzyme that catalyzes the reduction of N2, is instantaneously and irreversibly inactivated by O2 via oxidative damage (Staal et al., 2007). Meanwhile, significantly decreased photosynthetic O2 evolution coincided with increased respiratory CO2 release during midday, that favored the N2 fixation (Kranz et al., 2009). In the present work, reduced levels of O2 in milieu significantly increased N2-fixation and photosynthesis (Figures 2, 3). Since lowered O2 concentration increased the net photosynthetic O2 evolution, the dissolved O2 in the cultures increased before the continual dilutions, which, nevertheless, did not significantly alter the difference in O2 treatments between lowered (LO) and ambient (AO) pO2 (Table 1). Therefore, the O2 levels (AO: 245–255 μM; LO: 60–90 μM) during the growth period could still reflect LO and AO conditions. In photosynthesis, electrons transport via the photosynthetic and respiratory transport chains must have promoted production of ATP and reductant for N2 fixation and CO2 assimilation in Trichodesmium (Suggett et al., 2010; Eichner et al., 2019). While no decline in net photosynthetic O2 evolution was found with enhanced dark respiration in this study (Figure 2), higher respiration rates during the photoperiod would decrease the photosynthetic O2 evolution in Trichodesmium (Berman-Frank et al., 2001), which must partially favored the N2 fixation. In the present work, the rates of dark respiration accounted for 37% in AO-grown and for 18% in LO-grown cells of the gross photosynthesis (Figures 2B,C), indicating that the role to remove O2 by respiration was down-regulated under LO. Since the O2 consumptions such as dark respiration were reduced under LO, and the net photosynthesis significantly increased (Figure 2), Mehler reaction must have been active in maintaining low intracellular O2 to sustain the activity of the nitrogenase and promote energetically expensive N2 fixation. Additionally, it is most likely that the Trichodesmium cells grown under low O2 could have greater abundances and/or upregulated activity of the nitrogenase (Zehr et al., 1993). Such physiological responses can be responsible for increased values of the N2-fixation quotient under the low O2 conditions (Figure 3C), indicating that the N2-fixation efficiency increased per photosynthetically evolved O2 or C fixed under low O2 and high CO2 conditions.

Although the cells of Trichodesmium grown under HC increased their N2 fixation under both ambient and lowered pO2 (Figure 3), their specific growth rates were unaffected compared to the AC-grown cells (Figures 1, 2). This contradicts to some of the previously reported results (Table 2), which show either enhanced or inhibited growth rates of Trichodesmium grown under future ocean acidification conditions. The likely reason responsible for such discrepancies between these studies (Table 2) could be that different light sources (different emission spectra) regulate the diazotroph’s response to elevated pCO2 even under equal levels of PAR (Yi and Gao, 2022), though such hypothetical explanation should be based on N2-fixation action spectra, which has not been documented. In addition, limitation of phosphate and iron ions as well as exposure to solar UV radiation could also result in negative or insignificant effects of future ocean acidification on the N2-fixation of Trichodesmium (Hong et al., 2017; Yi and Gao, 2022; Zhang et al., 2022). In the present study, when the Trichodesmium cells acclimated to the acidified HC treatment with replete phosphate and iron, its photosynthesis and growth did not show significant changes, though its N2-fixation increased by 129% under ambient and by 38% under the reduced pO2, respectively (Figure 3). In addition, the HC treatment increased its POC significantly under the LO (Figure 4), though its photosynthesis did not show significant change (Figure 2). Such inconsistency between the photosynthetic responses and the POC production could be attributed to altered photosynthetic quotients (ratios of evolved O2 to CO2 fixed). In the present work, gross photosynthetic rates changed less compared to the net photosynthetic rates, since dark respiration decreased when net photosynthesis increased under the different combinations of pO2 and pCO2. On the other hand, the documented photosynthetic quotients of Trichodesmium ranged 1.28–2.60 (Kranz et al., 2010; Boatman et al., 2019). Therefore, photosynthetic O2 evolution rates can hardly be taken as a proxy of C fixation, which must be responsible for the observed discrepancy between the POC production and photosynthetic O2 evolution.

Table 2. Documented growth rates (μ) and nitrogen fixation rates (NF) of T. erythraeum grown under low (350 ~ 400 μatm) and high (750 ~ 1,400 μatm, values in the brackets) CO2 conditions.

Carbon and nitrogen fixation are both energy-intensive processes that compete directly for the products of photosynthesis (Berman-Frank et al., 2001; Hutchins et al., 2007). Previously, the enhancement of N2 fixation as well as growth rate of Trichodesmium at elevated pCO2 levels has been considered as an indirect effect resulting from alleviation of C-limitation of CO2 fixation (Hutchins et al., 2007) or attributed to saved energy from down-regulation of CCMs (Table 2). However, Shi et al. (2012) and Hong et al. (2017) showed that the N2 fixation rate of T. erythraeum significantly decreased under the elevated pCO2 projected for future acidification, which was attributed to reduced efficiency of nitrogenase, although the expression of the nitrogenase was enhanced in terms of proteomic responses (Zhang et al., 2019; Wen et al., 2022). Our data did not show significant effects of the elevated pCO2 on the growth rate and photosynthesis in T. erythraeum, but its N2 fixation rate and POC/PON were enhanced (Figures 2–4). It is likely that the energy saved from downregulation of CMMs under HC was not enough to bring significant increase of net photosynthesis and growth rate (Luo et al., 2019). Considering that phytoplankton can benefit from the elevated pCO2 under light but suffer from the acidic stress in darkness, resulting in daytime enhanced and nighttime suppressed growth rates (Qu et al., 2021), the net effects of the HC treatment on growth should be holistically considered for the diel cycle and availability of nutrients (Table 2). We suggest that extra energy required to cope with the acidic stress under HC could be provided via increased dark respiration (Figure 2), compensating for the insufficient energy supply from the downregulation of CCMs in Trichodesmium cells grown under HC. In the present work, lowered levels of O2 enhanced photosynthesis and POC production of Trichodesmium (Figures 2, 4). This could be attributed to suppressed respiration (Figure 2), which enables the cells to save more POC (Figure 4A).

Since one time point measurement might have overlooked daily N2 fixation, the rates of N2 fixation in this work could hardly be approximated to that of PON production (Figures 3, 4). When the N2 fixation rate was integrated for the daytime, it turned out that PON production rate (Supplementary Figure S3) was higher than the integrated N2 fixation per day, which was about one third of the PON production rates. Similar discrepancy was also reported by Zhang et al. (2019), whose daily PON production rate was about 3 times the daily integrated N2 fixation. In the present work, increased proportion (15%) of PON is much less than the enhancement (139%) of N2 fixation under LO compared to AO under ambient CO2 concentration (Figures 3, 4), such inconsistency could be contributed to the fact that PON production reflects how much new fixed N is ultimately incorporated into the cells which covers several generations, while N2 fixation rate measured within 2 h during the midday could only reflect the periodical performance during light period. Future studies should examine the diurnal variations of the N2 fixation to look into the diel or diurnal responses. Meanwhile, increased availability of CO2 (Kranz et al., 2010; Hutchins et al., 2015) and elongated light period (Cai and Gao, 2015) could alter the maximal rate of N2 fixation from the mid-light period, the low O2 treatment might have led to different levels of N2 fixation rates at different time points during the light period, which could also be responsible for the inconsistency. On the other hand, since the cells can release 10 to 50% of the fixed N as dissolved organic N (DON) and / or NH4+ into seawater (Mulholland et al., 2004; Konno et al., 2010; Lu et al., 2018), the proportional increase of PON could be less. The exudation of “new-fixed” N may be further increased at elevated pCO2 (Hutchins et al., 2007), which is mirrored in our study in that the elevated pCO2 enhanced the N2 fixation but not changed the cellular PON under the ambient O2 level (Figures 3, 4).

The global oxygen loss has been suggested to be about 2% of the total ocean inventory per decade since 1960 (Schmidtko et al., 2017) and the O2 concentration of ocean has been predicted to decline to about 200 μmol L−1 by the end of the century (−5 μmol kg−1 per decade) (Breitburg et al., 2018). In addition, upwelling-induced hypoxia events have been shown in sunlit layers in time-series observations (Gireeshkumar et al., 2017), and typhon-driven mixing would churn deep seawater of low O2 and high CO2 to surface layer. Therefore, diazotrophs and other phytoplankton are inevitably exposed to extreme low O2 and high CO2 conditions. This study provided the experimental evidence that combination of lowered pO2 and pH along with elevated pCO2 enhanced the photosynthesis and N2-fixation of Trichodesmium. Under the future scenarios of ocean deoxygenation and acidification, as estimated in the present work, Trichodesmium would decrease its dark respiration by 5% and increase its N2-fixation by 49% and N2-fixation quotient by 30% with 16% decline of pO2 and 138% rise of pCO2 by the end of this century (Supplementary Table S1; Figure 5). Such estimation might overestimate the changed percentage, since increased POC and PON only accounted for 10% and by 8%, respectively (Figure 4). As increased temperature would also enhance iron use efficiency (Jiang et al., 2018) and stimulate dark respiration and then favors N2-fixation, decreased O2 availability along with ocean warming can further enhance the activity of the nitrogenase and increased N2-fixation of Trichodesmium, as long as ocean warming does not surpass the thermal tipping point for its growth.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

KG and HL designed the experiment, and analyzed the data and wrote and improved the manuscript. HL carried out the experiment. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This study was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (nos. 41721005, 41720104005, and 41890803).

We are grateful to David A. Hutchins and Fei-xue Fu for their constructive comments, and thank the laboratory engineers Xianglan Zeng, Wenyan Zhao, and Liting Peng for their logistical and technical support.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2023.1102909/full#supplementary-material

Bergman, B., Sandh, G., Lin, S., Larsson, J., and Carpenter, E. J. (2013). Trichodesmium–a widespread marine cyanobacterium with unusual nitrogen fixation properties. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 37, 286–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2012.00352.x

Berman-Frank, I., Lundgren, P., Chen, Y.-B., Kupper, H., Kolber, Z., Bergman, B., et al. (2001). Segregation of nitrogen fixation and oxygenic photosynthesis in the marine cyanobacterium Trichodesmium. Science 294, 1534–1537. doi: 10.1126/science.1064082

Boatman, T. G., Davey, P. A., Lawson, T., and Geider, R. J. (2019). CO2 modulation of the rates of photosynthesis and light-dependent O2 consumption in Trichodesmium. J. Exp. Bot. 70, 589–597. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ery368

Boyd, P. W., Collins, S., Dupont, S., Fabricius, K., Gattuso, J. P., Havenhand, J., et al. (2018). Experimental strategies to assess the biological ramifications of multiple drivers of global ocean change—a review. Glob. Chang. Biol. 24, 2239–2261. doi: 10.1111/gcb.14102

Breitburg, D., Levin, L. A., Oschlies, A., Grégoire, M., Chavez, F. P., Conley, D. J., et al. (2018). Declining oxygen in the global ocean and coastal waters. Science 359:eaam7240. doi: 10.1126/science.aam7240

Cai, X., and Gao, K. (2015). Levels of daily light doses under changed day-night cycles regulate temporal segregation of photosynthesis and N2 fixation in the cyanobacterium Trichodesmium erythraeum IMS101. PLoS One 10:e0135401. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135401

Capone, D. G. (1993). “Determination of nitrogenase activity in aquatic samples using the acetylene reduction procedure” in Handbook of Methods in Aquatic Microbial Ecology. eds. P. F. Kemp, B. F. Sherr, E. B. Sherr, and J. J. Cole (New York: Lewis Publishers), 621–631.

Carstensen, J., Andersen, J. H., Gustafsson, B. G., and Conley, D. J. (2014). Deoxygenation of the Baltic Sea during the last century. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 111, 5628–5633. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1323156111

Chen, Y. B., Zehr, J. P., and Mellon, M. (1996). Growth and nitrogen fixation of the diazotrophic filamentous nonheterocystous cyanobacterium Trichodesmium sp. IMS 101 in defined media: evidence for a circadian rhythm. J. Phycol. 32, 916–923. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-3646.1996.00916.x

Eichner, M., Kranz, S. A., and Rost, B. (2014). Combined effects of different CO2 levels and N sources on the diazotrophic cyanobacterium Trichodesmium. Physiol. plantarum. 152, 316–330. doi: 10.1111/ppl.12172

Eichner, M., Thoms, S., Rost, B., Mohr, W., Ahmerkamp, S., Ploug, H., et al. (2019). N2 fixation in free-floating filaments of Trichodesmium is higher than in transiently suboxic colony microenvironments. New Phytol. 222, 852–863. doi: 10.1111/nph.15621

Gallon, J. (2001). N2 fixation in phototrophs: adaptation to a specialized way of life. Plant Soil 230, 39–48. doi: 10.1023/A:1004640219659

Gao, K., Gao, G., Wang, Y., and Dupont, S. (2020). Impacts of ocean acidification under multiple stressors on typical organisms and ecological processes. Mar. Life. Sci. Tech. 2, 279–291. doi: 10.1007/s42995-020-00048-w

Gao, G., Wang, T., Sun, J., Zhao, X., Wang, L., Guo, X., et al. (2022). Contrasting responses of phytoplankton productivity between coastal and offshore surface waters in the Taiwan Strait and the South China Sea to short-term seawater acidification. Biogeosciences 19, 2795–2804. doi: 10.5194/bg-19-2795-2022

Gao, G., Xia, J., Yu, J., Fan, J., and Zeng, X. (2018). Regulation of inorganic carbon acquisition in a red tide alga (Skeletonema costatum): the importance of phosphorus availability. Biogeosciences 15, 4871–4882. doi: 10.5194/bg-15-4871-2018

Garcia, N. S., Fu, F. X., Breene, C. L., Bernhardt, P. W., Mulholland, M. R., Sohm, J. A., et al. (2011). Interactive effects of irradiance and CO2 on CO2 fixation and N2 fixation in the diazotroph trichodesmium erythraeum (cyanobacteria). J. Phycol. 47, 1292–1303. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8817.2011.01078.x

Giordano, M., Beardall, J., and Raven, J. (2005). CO2 concentrating mechanisms in algae: mechanisms, environmental modulation, and evolution. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 56, 99–131. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.56.032604.144052

Gireeshkumar, T., Mathew, D., Pratihary, A., Naik, H., Narvekar, K., Araujo, J., et al. (2017). Influence of upwelling induced near shore hypoxia on the Alappuzha mud banks, south west coast of India. Cont. Shelf Res. 139, 1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.csr.2017.03.009

Hong, H., Shen, R., Zhang, F., Wen, Z., Chang, S., Lin, W., et al. (2017). The complex effects of ocean acidification on the prominent N2-fixing cyanobacterium Trichodesmium. Science 356, 527–531. doi: 10.1126/science.aal2981

Hutchins, D. A., Fu, F.-X., Webb, E. A., Walworth, N., and Tagliabue, A. (2013). Taxon-specific response of marine nitrogen fixers to elevated carbon dioxide concentrations. Nat. Geosci. 6, 790–795. doi: 10.1038/ngeo1858

Hutchins, D., Fu, F.-X., Zhang, Y., Warner, M., Feng, Y., Portune, K., et al. (2007). CO2 control of Trichodesmium N2 fixation, photosynthesis, growth rates, and elemental ratios: implications for past, present, and future ocean biogeochemistry. Limnol. Oceanogr. 52, 1293–1304. doi: 10.4319/lo.2007.52.4.1293

Hutchins, D. A., and Sañudo-Wilhelmy, S. A. (2022). The enzymology of ocean global change. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 14, 187–211. doi: 10.1146/annurev-marine-032221-084230

Hutchins, D. A., Walworth, N. G., Webb, E. A., Saito, M. A., Moran, D., McIlvin, M. R., et al. (2015). Irreversibly increased nitrogen fixation in Trichodesmium experimentally adapted to elevated carbon dioxide. Nat. Commun. 6, 8155–8157. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9155

Jiang, H.-B., Fu, F.-X., Rivero-Calle, S., Levine, N. M., Sañudo-Wilhelmy, S. A., Qu, P.-P., et al. (2018). Ocean warming alleviates iron limitation of marine nitrogen fixation. Nat. Clim. Chang. 8, 709–712. doi: 10.1038/s41558-018-0216-8

Karl, D., Letelier, R., Tupas, L., Dore, J., Christian, J., and Hebel, D. (1997). The role of nitrogen fixation in biogeochemical cycling in the subtropical North Pacific Ocean. Nature 388, 533–538. doi: 10.1038/41474

Konno, U., Tsunogai, U., Komatsu, D., Daita, S., Nakagawa, F., Tsuda, A., et al. (2010). Determination of total N2 fixation rates in the ocean taking into account both the particulate and filtrate fractions. Biogeosciences 7, 2369–2377. doi: 10.5194/bg-7-2369-2010

Kranz, S. A., Dieter, S., Richter, K.-U., and Rost, B. (2009). Carbon acquisition by Trichodesmium: the effect of pCO2 and diurnal changes. Limnol. Oceanogr. 54, 548–559. doi: 10.4319/lo.2009.54.2.0548

Kranz, S. A., Levitan, O., Richter, K.-U., Prá¡il, O., Berman-Frank, I., and Rost, B. (2010). Combined effects of CO2 and light on the N2-fixing cyanobacterium Trichodesmium IMS101: physiological responses. Plant Physiol. 154, 334–345. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.159145

Levitan, O., Brown, C. M., Sudhaus, S., Campbell, D., LaRoche, J., and Berman-Frank, I. (2010). Regulation of nitrogen metabolism in the marine diazotroph Trichodesmium IMS101 under varying temperatures and atmospheric CO2 concentrations. Environ. Microbiol. 12, 1899–1912. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02195.x

Levitan, O., Rosenberg, G., Setlik, I., Setlikova, E., Grigel, J., Klepetar, J., et al. (2007). Elevated CO2 enhances nitrogen fixation and growth in the marine cyanobacterium Trichodesmium. Glob. Chang. Biol. 13, 531–538. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2006.01314.x

Lewis, E., Wallace, D., and Allison, L. (1998). Program developed for CO2 system calculations. In: oceanCO2, Available at: https://www.osti.gov/servlets/purl/639712

Lin, S., Henze, S., Lundgren, P., Bergman, B., and Carpenter, E. J. (1998). Whole-cell immunolocalization of nitrogenase in marine diazotrophic cyanobacteria Trichodesmium spp. Trichodesmium spp. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64, 3052–3058. doi: 10.1128/AEM.64.8.3052-3058.1998

Lu, Y., Wen, Z., Shi, D., Chen, M., Zhang, Y., Bonnet, S., et al. (2018). Effect of light on N2 fixation and net nitrogen release of Trichodesmium in a field study. Biogeosciences 15, 1–12. doi: 10.5194/bg-15-1-2018

Luo, W., Inomura, K., Zhang, H., and Luo, Y.-W. (2022). N2 fixation in Trichodesmium does not require spatial segregation from photosynthesis. Msystems 7, e0053822–e0000522. doi: 10.1128/msystems.00538-22

Luo, Y.-W., Shi, D., Kranz, S. A., Hopkinson, B. M., Hong, H., Shen, R., et al. (2019). Reduced nitrogenase efficiency dominates response of the globally important nitrogen fixer Trichodesmium to ocean acidification. Nat. Commun. 10, 1521–1512. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09554-7

Mahaffey, C., Michaels, A. F., and Capone, D. G. (2005). The conundrum of marine N2 fixation. Am. J. Sci. 305, 546–595. doi: 10.2475/ajs.305.6-8.546

Milligan, A. J., Berman-Frank, I., Gerchman, Y., Dismukes, G. C., and Falkowski, P. G. (2007). Light-dependent oxygen consumption in nitrogen-fixing cyanobacteria plays a key role in nitrogenase protection 1. J. Phycol. 43, 845–852. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8817.2007.00395.x

Mulholland, M. R., Bronk, D. A., and Capone, D. (2004). Dinitrogen fixation and release of ammonium and dissolved organic nitrogen by Trichodesmium IMS101. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 37, 85–94. doi: 10.3354/ame037085

Paerl, H., and Bebout, B. (1992). “Oxygen dynamics in Trichodesmium spp. aggregates” in Marine pelagic Cyanobacteria: Trichodesmium and Other Diazotrophs (Dordrecht: Springer)

Paulmier, A., Ruiz-Pino, D., and Garçon, V. (2011). CO2 maximum in the oxygen minimum zone (OMZ). Biogeosciences 8, 239–252. doi: 10.5194/bg-8-239-2011

Prufert-Bebout, L., Paerl, H. W., and Lassen, C. (1993). Growth, nitrogen fixation, and spectral attenuation in cultivated Trichodesmium species. Appl. Environ. Microb. 59, 1367–1375. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.5.1367-1375.1993

Qu, L., Beardall, J., Jiang, X., and Gao, K. (2021). Elevated pCO2 enhances under light but reduces in darkness the growth rate of a diatom, with implications for the fate of phytoplankton below the photic zone. Limnol. Oceanogr. 66, 3630–3642. doi: 10.1002/lno.11903

Ritchie, R. (2006). Consistent sets of spectrophotometric chlorophyll equations for acetone, methanol and ethanol solvents. Photosynth. Res. 89, 27–41. doi: 10.1007/s11120-006-9065-9

Schmidtko, S., Stramma, L., and Visbeck, M. (2017). Decline in global oceanic oxygen content during the past five decades. Nature 542, 335–339. doi: 10.1038/nature21399

Shi, D., Kranz, S. A., Kim, J.-M., and Morel, F. M. (2012). Ocean acidification slows nitrogen fixation and growth in the dominant diazotroph Trichodesmium under low-iron conditions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109, E3094–E3100. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1216012109

Sohm, J. A., Webb, E. A., and Capone, D. G. (2011). Emerging patterns of marine nitrogen fixation. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 9, 499–508. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2594

Staal, M., Rabouille, S., and Stal, L. J. (2007). On the role of oxygen for nitrogen fixation in the marine cyanobacterium Trichodesmium sp. Environ. Microbiol. 9, 727–736. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2006.01195.x

Stramma, L., Johnson, G. C., Sprintall, J., and Mohrholz, V. (2008). Expanding oxygen-minimum zones in the tropical oceans. Science 320, 655–658. doi: 10.1126/science.1153847

Suggett, D. J., Moore, C. M., and Geider, R. J. (2010). “Estimating aquatic productivity from active fluorescence measurements” in Chlorophyll a fluorescence in aquatic sciences: Methods and applications (Dordrecht: Springer), 103–127. doi: 10.1007/978-90-481-9268-7_6

Sun, J.-Z., Wang, T., Huang, R., Yi, X., Zhang, D., Beardall, J., et al. (2022). Enhancement of diatom growth and phytoplankton productivity with reduced O2 availability is moderated by rising CO2. Commun. Biol. 5, 54–12. doi: 10.1038/s42003-022-03006-7

Wake, B. (2019). Experimenting with multistressors. Nat. Clim. Chang. 9:357. doi: 10.1038/s41558-019-0475-z

Wen, Z., Browning, T. J., Dai, R., Wu, W., Li, W., Hu, X., et al. (2022). The response of diazotrophs to nutrient amendment in the South China Sea and western North Pacific. Biogeosciences 19, 5237–5250. doi: 10.5194/bg-19-5237-2022

Yi, X., Fu, F.-X., Hutchins, D. A., and Gao, K. (2020). Light availability modulates the effects of warming in a marine N2 fixer. Biogeosciences 17, 1169–1180. doi: 10.5194/bg-17-1169-2020

Yi, X., and Gao, K. (2022). Impact of ultraviolet radiation nearly overrides the effects of elevated pCO2 on a prominent nitrogen-fixing cyanobacterium. Limnol. Oceanogr. doi: 10.1002/lno.12294

Zehr, J. P., Wyman, M., Miller, V., Duguay, L., and Capone, D. G. (1993). Modification of the Fe protein of nitrogenase in natural populations of Trichodesmium thiebautii. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59, 669–676. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.3.669-676.1993

Zhang, F., Hong, H., Kranz, S. A., Shen, R., Lin, W., and Shi, D. (2019). Proteomic responses to ocean acidification of the marine diazotroph Trichodesmium under iron-replete and iron-limited conditions. Photosynth. Res. 142, 17–34. doi: 10.1007/s11120-019-00643-8

Keywords: growth rate, N2 fixation, photosynthesis, respiration, Trichodesmium erythraeum

Citation: Li H and Gao K (2023) Deoxygenation enhances photosynthetic performance and increases N2 fixation in the marine cyanobacterium Trichodesmium under elevated pCO2. Front. Microbiol. 14:1102909. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2023.1102909

Received: 19 November 2022; Accepted: 27 January 2023;

Published: 15 February 2023.

Edited by:

Francisco G. Figueiras, Institute of Marine Research (CSIC), SpainReviewed by:

Biswarup Sen, Tianjin University, ChinaCopyright © 2023 Li and Gao. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kunshan Gao, ✉ a3NnYW9AeG11LmVkdS5jbg==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.