- 1State Key Laboratory of Oral Diseases, Department of Preventive Dentistry, National Clinical Research Center for Oral Diseases, West China Hospital of Stomatology, Sichuan University, Chengdu, China

- 2Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Stomatology, Department of Operative Dentistry and Endodontics, Hospital of Stomatology, Guanghua School of Stomatology, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, China

Streptococcus mutans constantly coexists with Candida albicans in plaque biofilms of early childhood caries (ECC). The progression of ECC can be influenced by the interactions between S. mutans and C. albicans through exopolysaccharides (EPS). Our previous studies have shown that rnc, the gene encoding ribonuclease III (RNase III), is implicated in the cariogenicity of S. mutans by regulating EPS metabolism. The DCR1 gene in C. albicans encodes the sole functional RNase III and is capable of producing non-coding RNAs. However, whether rnc or DCR1 can regulate the structure or cariogenic virulence of the cross-kingdom biofilm of S. mutans and C. albicans is not yet well understood. By using gene disruption or overexpression assays, this study aims to investigate the roles of rnc and DCR1 in modulating the biological characteristics of dual-species biofilms of S. mutans and C. albicans and to reveal the molecular mechanism of regulation. The morphology, biomass, EPS content, and lactic acid production of the dual-species biofilm were assessed. Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) and transcriptomic profiling were performed to unravel the alteration of C. albicans virulence. We found that both rnc and DCR1 could regulate the biological traits of cross-kingdom biofilms. The rnc gene prominently contributed to the formation of dual-species biofilms by positively modulating the extracellular polysaccharide synthesis, leading to increased biomass, biofilm roughness, and acid production. Changes in the microecological system probably impacted the virulence as well as polysaccharide or pyruvate metabolism pathways of C. albicans, which facilitated the assembly of a cariogenic cross-kingdom biofilm and the generation of an augmented acidic milieu. These results may provide an avenue for exploring new targets for the effective prevention and treatment of ECC.

Introduction

Early childhood caries (ECC) is an aggressive form of tooth decay in children younger than 6 years, with a high prevalence of 70% in disadvantaged groups worldwide (James et al., 2018; Peres et al., 2019; Duan et al., 2021). Streptococcus mutans (S. mutans) is a critical pathogen of dental caries due to its acidogenicity, aciduricity, and capacity to develop cariogenic biofilms by synthesizing exopolysaccharides (EPS) (Lemos et al., 2019). As the main virulence factor of S. mutans, EPS are conducive to the energy storage, adhesion, and three-dimensional (3D) architecture of dental plaque biofilms (Koo et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2019). Another microbe frequently detected with S. mutans in plaque biofilms of ECC is Candida albicans (C. albicans), an opportunistic fungal pathogen usually isolated from the human oral cavity (Ponde et al., 2021; Ramadugu et al., 2021). C. albicans is closely correlated with the occurrence and development of ECC or persistent apical periodontitis in which the pathogens are difficult to eradicate especially in molars with complicated root canal morphology (Zhang et al., 2011a,b; Mustafa et al., 2022). Children with oral C. albicans have a more than 5 times higher possibility of developing ECC than those without C. albicans (Xiao et al., 2018b). C. albicans can strengthen the ability of microflora to produce or tolerate acid, elevate the abundance of S. mutans, and enhance the activity of glucosyltransferases (Gtfs) secreted by S. mutans in plaque biofilms of severe early childhood caries (S-ECC) (Xiao et al., 2018a). These findings suggest that the coexistence of S. mutans and C. albicans is closely related to the progression of ECC. In the co-culture biofilm, the presence of C. albicans improves the carbohydrate metabolism of S. mutans and affects its environmental fitness and biofilm formation (He et al., 2017). Mannans located in the cell wall of C. albicans binds to S. mutans-derived GtfB to regulate EPS formation, mechanical stability, and colonization of dual-species biofilms (Hwang et al., 2017; Khoury et al., 2020). S. mutans-secreted GtfB, in turn, can not only break sucrose down into monosaccharides that are efficiently utilized by C. albicans to enhance its acid production but also improve fungal colonization onto the tooth surface and antifungal resistance to fluconazole (Kim et al., 2018; Ellepola et al., 2019). Transcriptomics and proteomics studies have implied that genes and proteins of C. albicans associated with polysaccharide metabolism and cell morphogenesis are significantly upregulated in dual-species biofilms of S. mutans and C. albicans (Ellepola et al., 2019). Therefore, EPS play important roles in the cross-kingdom interaction between S. mutans and C. albicans.

Ribonuclease III (RNase III) is the endonuclease in bacteria and eukaryotes that participates in RNA biogenesis to control gene expression (Svensson and Sharma, 2021). Our previous studies have illuminated that the gene encoding S. mutans RNase III, rnc, enhances the EPS synthesis and cariogenicity of bacterial biofilms through non-coding RNAs that target vicR, the gene encoding a response regulator of EPS metabolism (Lei et al., 2018, 2020). On the one hand, rnc impairs vicR expression by affecting the generation of microRNA-size small RNA 1657 (msRNA 1657), which can bind to the 5′-UTR regions of the vicR mRNA (Lei et al., 2019). On the other hand, rnc increases the expression of vicR antisense (ASvicR) RNA, thus influencing the transcriptional level of the vicR gene (Lei et al., 2020). C. albicans also has DCR1 as the sole functional RNase III, which is instrumental in small interfering RNA (siRNA), ribosomal RNA (rRNA), and small nuclear RNA (snRNA) generation (Drinnenberg et al., 2009; Bernstein et al., 2012). Notably, although deletions of one copy of the DCR1 gene in diploids do not restrict C. albicans growth, mutants deficient in both copies of the DCR1 allele cannot be recovered, indicating that DCR1 is essential for C. albicans survival (Bernstein et al., 2012). In summary, as RNase III-coding genes in bacteria and eukaryotes, rnc regulates extracellular matrix synthesis and cariogenic characteristics of S. mutans biofilms at the post-transcriptional level, while DCR1 catalyzes the production of non-coding RNAs in C. albicans. However, whether rnc and DCR1 affect the EPS and cariogenicity of cross-kingdom biofilms of S. mutans and C. albicans has not yet been elucidated.

In this study, C. albicans DCR1 low-expressing and overexpressing strains were constructed and co-cultured with S. mutans wild-type or rnc-mutant strains to explore the roles of rnc and DCR1 in the modulation of dual-species biofilms of S. mutans and C. albicans. We demonstrated that DCR1 regulated the fungal yeast-to-hyphae transition, spatial structure, acid production, and glucan/microorganism ratio of biofilms, while rnc prominently contributed to cross-kingdom biofilm formation by boosting extracellular polysaccharide synthesis. Alterations of the microecosystem caused by rnc might affect the virulence of C. albicans that facilitated the assembly of a cariogenic cross-kingdom biofilm and the formation of an intensive acidic milieu. According to these results, rnc and DCR1 may be new potential targets for ECC prevention and treatment.

Materials and methods

Microorganisms and construction of mutant strains

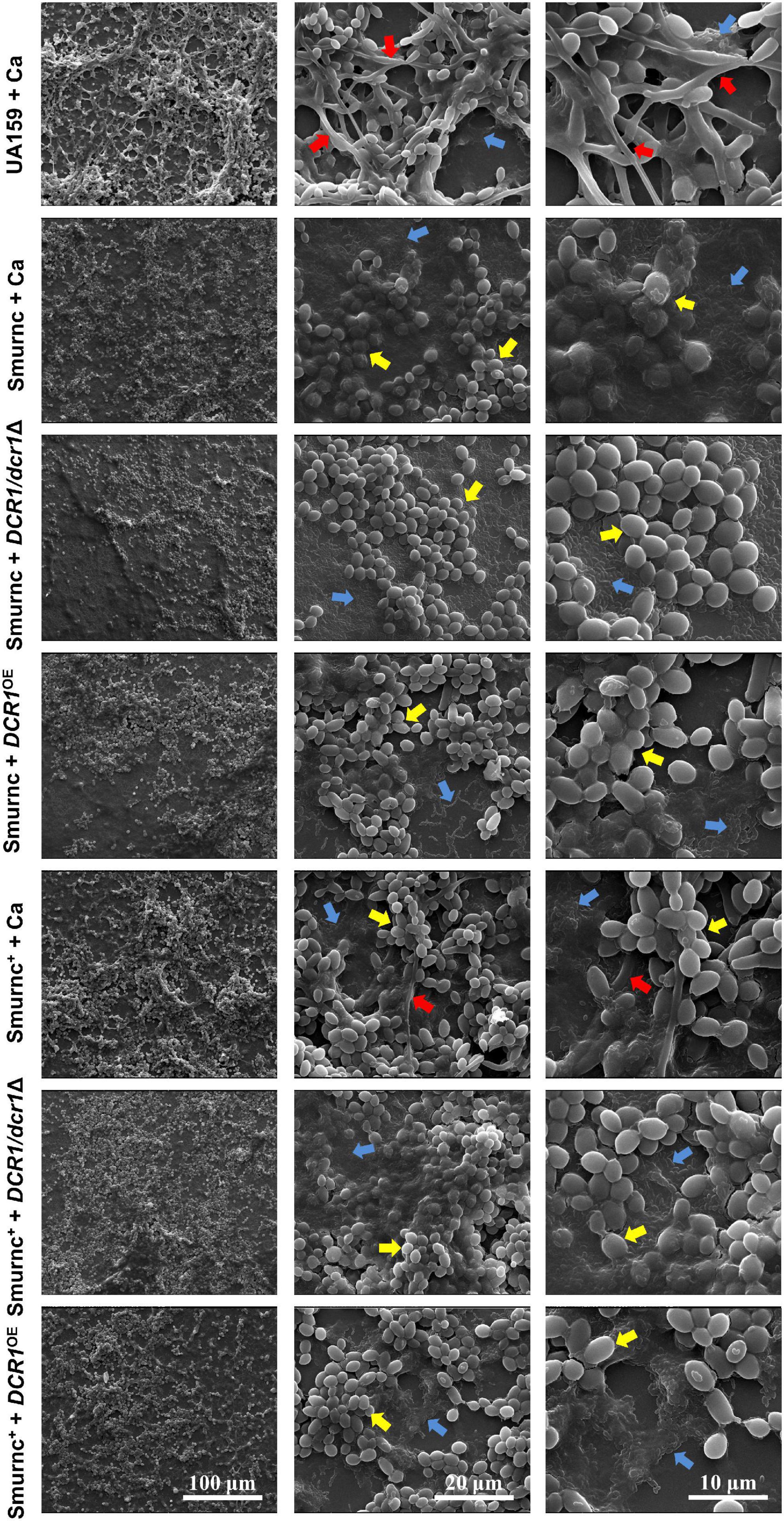

The strains and plasmids used in this study are summarized in Table 1. C. albicans SC5314 and CAI4, and S. mutans UA159 were kindly provided by the State Key Laboratory of Oral Diseases (Sichuan University, Chengdu, China). S. mutans strains were cultured on brain heart infusion (BHI; BD, Franklin Lakes, United States) medium with erythromycin or spectinomycin when necessary at 37°C anaerobically (10% CO2, 80% N2, 10% H2). C. albicans SC5314 and CAI4 were grown in the YPD medium (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, and 2% dextrose) at 30°C with shaking (150 rpm) under aerobic conditions. A C. albicans DCR1 low-expressing strain (DCR1/dcr1Δ) was constructed by deleting one copy of the DCR1 gene using plasmid p5921 according to the URA-Blaster method (Janik et al., 2019). Upstream and downstream fragments of DCR1 from the chromosome were inserted into both ends of the hisG-URA3-hisG cassette of p5921 to obtain the recombinant plasmid pUC-DCR1-URA3 to replace one of the DCR1 alleles in C. albicans. The open reading frame (ORF) of the DCR1 gene was cloned into the pCaEXP plasmid to establish the recombinant vector pCaEXP-DCR1, which could integrate into the RP10 locus of the C. albicans genome to create a DCR1 overexpressing strain (DCR1OE) (Jia et al., 2011; Basso et al., 2017; Znaidi et al., 2018). All recombinant plasmids were transformed into C. albicans CAI4 utilizing the Yeast Transformation Kit (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, United States). The mutagenic strains were selected on a synthetic dropout (SD) medium without uridine, methionine, and cysteine and then verified by PCR, DNA sequencing, and quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) with the primers listed in Supplementary Table 1. The rnc-deficient strain (Smurnc) was constructed by an erythromycin cassette based on homologous recombination. Meanwhile, the recombinant plasmid pDL278 containing the rnc ORF and promoter region was transformed into S. mutans UA159 to generate an rnc overexpressing strain (Smurnc+), as previously described (Lau et al., 2002; Lei et al., 2020).

Biofilm formation

Streptococcus mutans and C. albicans were grown to mid-exponential phase and co-cultured in YNBB medium (0.67% YNB, 75 mM Na2HPO4-NaH2PO4, 0.5% sucrose, and essential amino acids) at the concentrations of 2 × 106 colony forming units (CFU)/ml (S. mutans) and 2 × 104CFU/ml (C. albicans). Cross-kingdom biofilms were formed in microtiter plates at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 24 h (Sztajer et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2017).

Biofilm observation and assessment

The structure of cross-kingdom biofilms was analyzed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM; FEI, Hillsboro, United States). Briefly, after being cultivated on sterile polystyrene slides, the biofilms were washed two times with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde at 4°C for 4 h in the dark, followed by serial dehydration with ethanol solutions (30, 50, 75, 85, 95, and 99%) and coating with gold for image collection. The biomass of the biofilms was quantified by the crystal violet (CV) microtiter assay. After incubation in 24-well polystyrene plates, the biofilms were stained with 0.1% (w/v) CV for 10 min at room temperature when the planktonic cells and supernatant were gently removed. The specimens were rinsed carefully with water, and then 33% acetic acid was added to dissolve the dye under gentle shaking at 37°C for 5 min. Finally, biofilm formation was detected by the absorbance of acetic acid at 575 nm.

Lactic acid generation evaluation

The mature biofilms were cultured in buffered peptone water (BPW; Hopebio, Qingdao, China) supplemented with 0.2% (w/v) sucrose at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 3 h after rinsing with PBS (Chen et al., 2020). The concentrations of lactic acid produced by the biofilms were calculated based on the standard curve according to the instructions of the Lactic Acid Assay Kit (Nanjing Jiancheng, China).

Exopolysaccharide distribution in biofilms

Glucan in the biofilms that grew in polystyrene cell culture dishes with modified bottoms was stained with Alexa Fluor 647 (Invitrogen, Waltham, United States) at a final concentration of 1 μl/ml during incubation. Microorganisms were labeled with 2.5 μM SYTO 9 green fluorescent dye (Invitrogen), while C. albicans was stained with calcofluor white dye (Sigma-Aldrich) (Punjabi et al., 2020). The distribution of microbes or glucan was detected by confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Biofilms were reconstructed, and imaging biomass quantification was analyzed using Imaris version 7.2.3 (Bitplane, Zurich, Switzerland) (Lei et al., 2020).

Exopolysaccharide production measurement

The biofilms were cultivated in 6-well polystyrene plates before the EPS content was determined by the anthrone method. Water-insoluble EPS extraction from dual-species biofilms was performed according to previous protocols with modifications (Lei et al., 2020). Biofilms were gently washed with PBS, collected by scraping, and centrifuged at 4°C (2,422 × g) for 15 min. The precipitates were solubilized in 1 M NaOH (Sigma, United States) by incubation at 37°C for 2 h at 120 rpm. After centrifugation (2,422 × g) at 4°C for 15 min, the supernatant containing water-insoluble EPS was collected and diluted with an anthrone-sulfuric acid reagent to a final concentration of 25% (v/v). The mixed samples were blended and incubated at 95°C for 6 min, and the absorbance was measured at an optical density of 625 nm.

Characteristics of the biofilm surface

The surface morphology and roughness of the biofilm were visualized and examined by atomic force microscopy (AFM). In brief, the biofilms cultured on polystyrene slides were mildly washed with PBS and dried in the air, followed by the measurement of surface roughness, which is represented by the arithmetic mean deviation of the profile (Ra) counted by an STM9700 system (Shimadzu, Tokyo, Japan) using a cantilever probe (HYDRA-ALL-G-20, AppNANO, Syracuse, United States) in contact mode (Deng et al., 2021). The scanning range was 10 × 10 μm.

RNA isolation and quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction assays

Biofilm cells were collected by scraping into PBS and harvested by centrifugation (4,500 × g) at 4°C for 10 min. Total RNA was extracted by a MasterPure™ complete DNA and RNA purification kit (Lucigen, Middleton, United States). Purification and reverse transcription of the isolated RNAs were performed by using the RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, United States) with gDNA Eraser (Takara, Dalian, China). qRT-PCR was conducted using TB Green® Premix Ex Taq™ (Takara) in a LightCycler 480 System (Roche, Vaud, Switzerland). All primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 1. The relative gene expression level of virulence factors of C. albicans was normalized to the gene expression level of the reference gene ACT1, and the data were interpreted as fold changes based on the control group according to the 2–ΔΔCt method.

Transcriptome sequencing and data analysis

Total RNA was quantified and qualified using a NanoDrop 2000 instrument (Thermo Scientific) and the 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent, Santa Clara, United States), respectively. The mRNA was isolated by the polyA selection method using oligo(dT) magnetic beads, followed by chemical fragmentation, and then double-stranded cDNA was prepared using a SuperScript double-stranded cDNA synthesis kit (Invitrogen) with random hexamer primers (Illumina, San Diego, United States). Libraries were size-selected for end-repaired cDNA target fragments of 300 bp on 2% low-range ultra agarose, followed by PCR amplification. Subsequently, RNA-Seq was conducted with the Illumina HiSeq xten/NovaSeq 6000 sequencer (2 × 150 bp read length). The differential expression genes (DEGs) were classified by Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COG). Furthermore, we performed Gene Ontology (GO) functional enrichment and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis to identify which DEGs were significantly enriched in GO terms and metabolic pathways using Fisher’s exact tests.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, United States), and differences in data were considered significant if P < 0.05. Data normality and the homogeneity of variance were tested by the Shapiro–Wilk method and Bartlett method, respectively. If the data obeyed the homogeneity of variance, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Fisher’s least significant difference (LSD) multiple-comparison test was used to examine the statistical significance; otherwise, Dunnett’s T3 multiple-comparison test was used.

Results

The DCR1 gene modulated the fungal yeast-to-hyphae transition, spatial structure, acid production, and glucan/microorganism volume ratio of the cross-kingdom biofilm

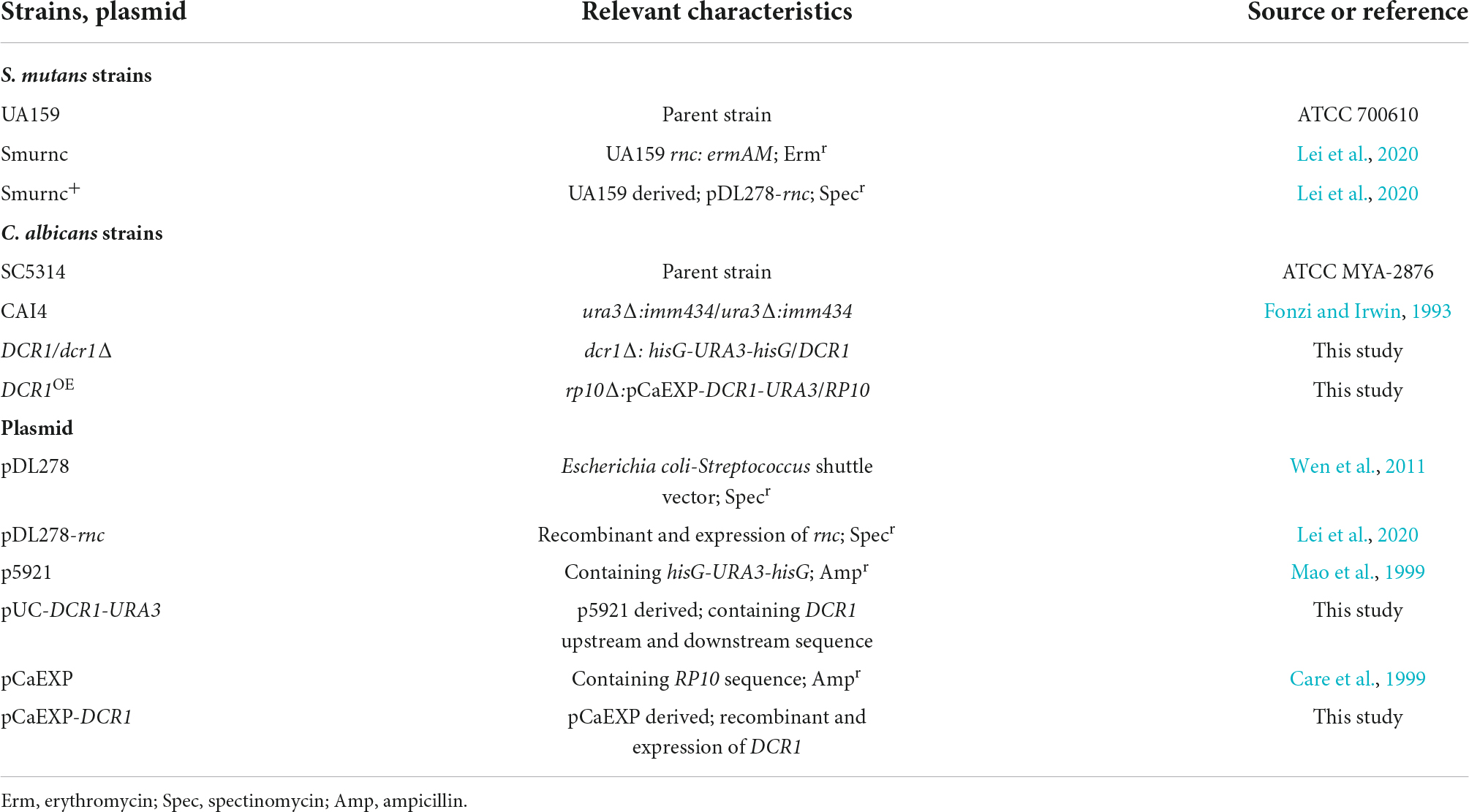

We successfully constructed a DCR1 low-expressing mutant DCR1/dcr1Δ and a DCR1 overexpressing mutant DCR1OE (Supplementary Figure 1). The biofilm of UA159 + Ca formed a pronounced 3D structure, and C. albicans was present mainly in the hyphal form (Figure 1A). Nevertheless, the cross-kingdom biofilms containing DCR1/dcr1Δ or DCR1OE seemed to lack skeletal architecture, and there were mostly C. albicans yeast cells (Figure 1A), which was in line with the CLSM results (Figure 1D). The glucan/microorganism ratio was used to reflect the capacity of microbial strains to produce glucan. The biofilm of UA159 + DCR1/dcr1Δ exhibited a conspicuously decreased glucan/microorganism volume ratio (Figure 1E), while UA159 + DCR1OE displayed increased lactic acid production compared to UA159 + Ca (Figure 1C). We also used the Ra (nm) value as an indication of the biofilm surface roughness. There was no significant difference in biomass (Figure 1B), biofilm roughness (Figures 1G,H), or total content of water-insoluble EPS (Figure 1F) among the three groups.

Figure 1. The effects of DCR1 gene on formation and exopolysaccharide synthesis of cross-kingdom biofilm. (A) Biofilms architecture was observed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Blue arrows, S. mutans; red arrows, C. albicans hyphae; yellow arrows, C. albicans yeast cells. Images were taken at 1,000 × (scale bar, 100 μm), 5,000 × (scale bar, 20 μm), and 10,000 × (scale bar, 10 μm) magnifications, respectively. (B) Biofilms volume was quantified by CV microtiter assay. (C) Lactic acid generation was assessed by the Lactic Acid Assay Kit. (D,E) Exopolysaccharide production and distribution in biofilms were visualized by confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM), and the ratio of glucan to microbes was calculated using Imaris version 7.2.3. Green, total microbes (SYTO 9); blue, C. albicans (calcofluor white); red, glucan (Alexa Fluor 647). (F) Water-insoluble exopolysaccharides from samples were measured by the anthrone method. (G,H) Biofilm morphology was detected by AFM and the surface roughness average (Ra) of biofilms was evaluated. Experiments were performed in biological triplicate. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

The rnc gene promoted the exopolysaccharide synthesis and cariogenic characteristics of cross-kingdom biofilms

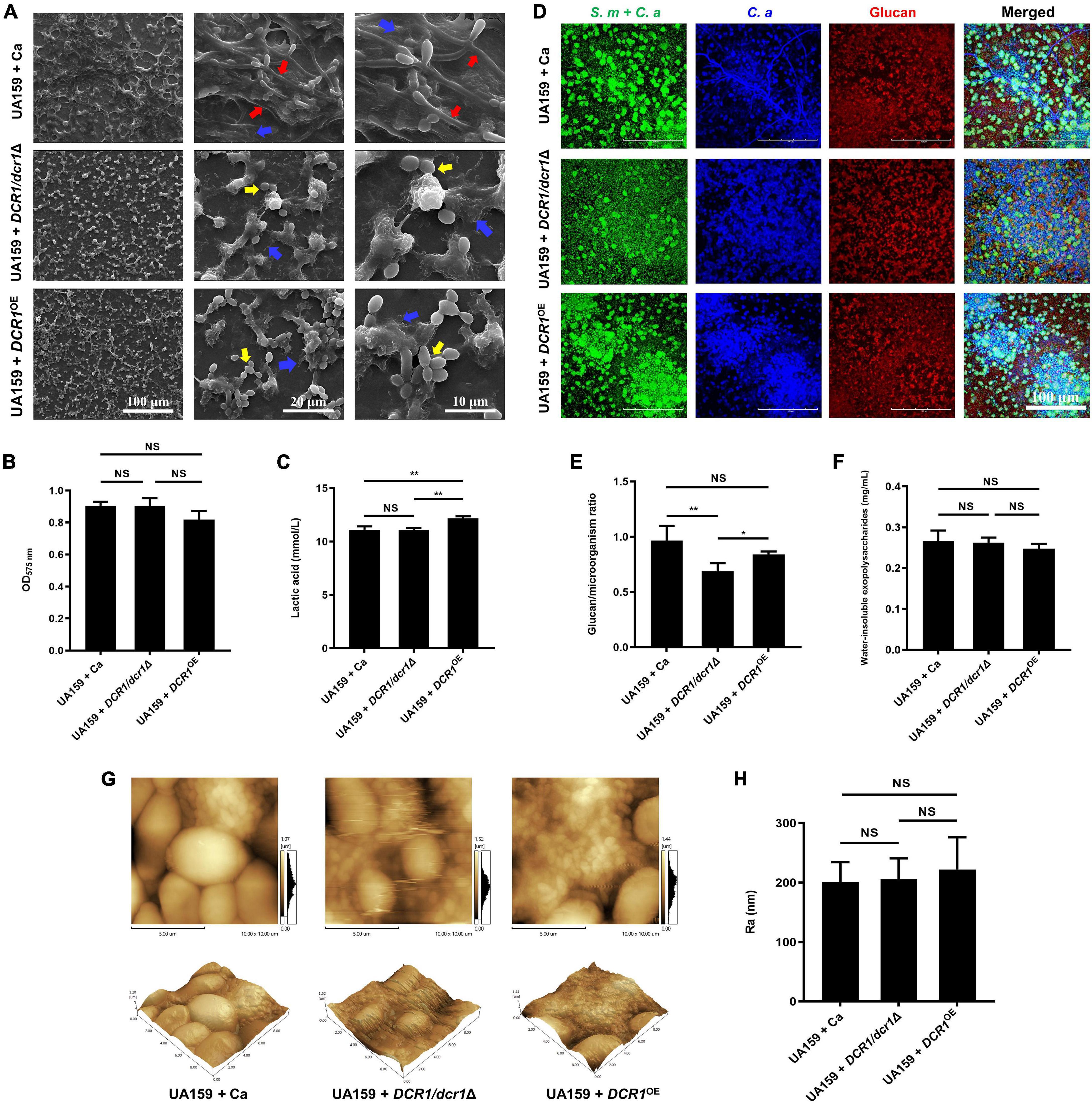

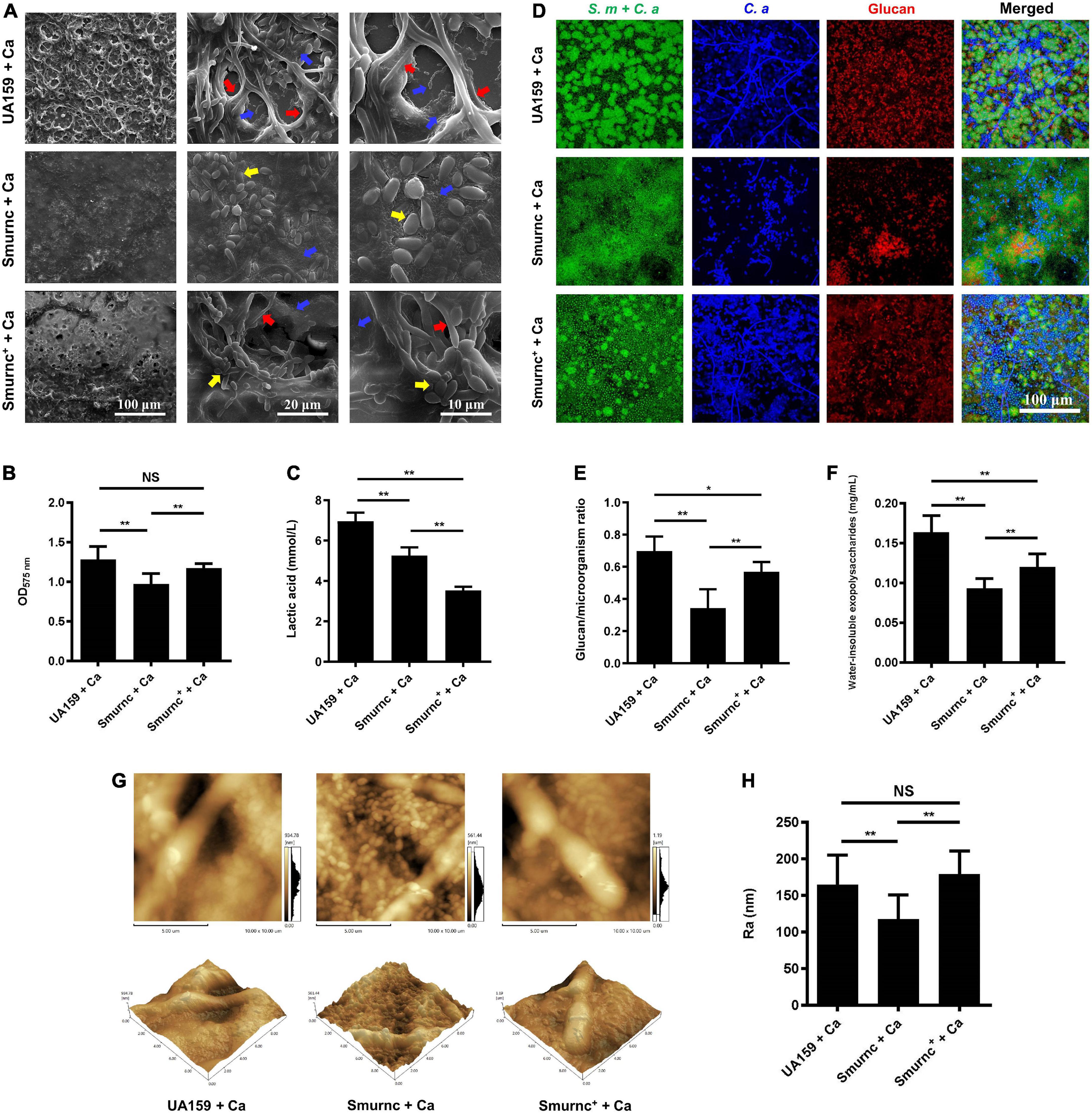

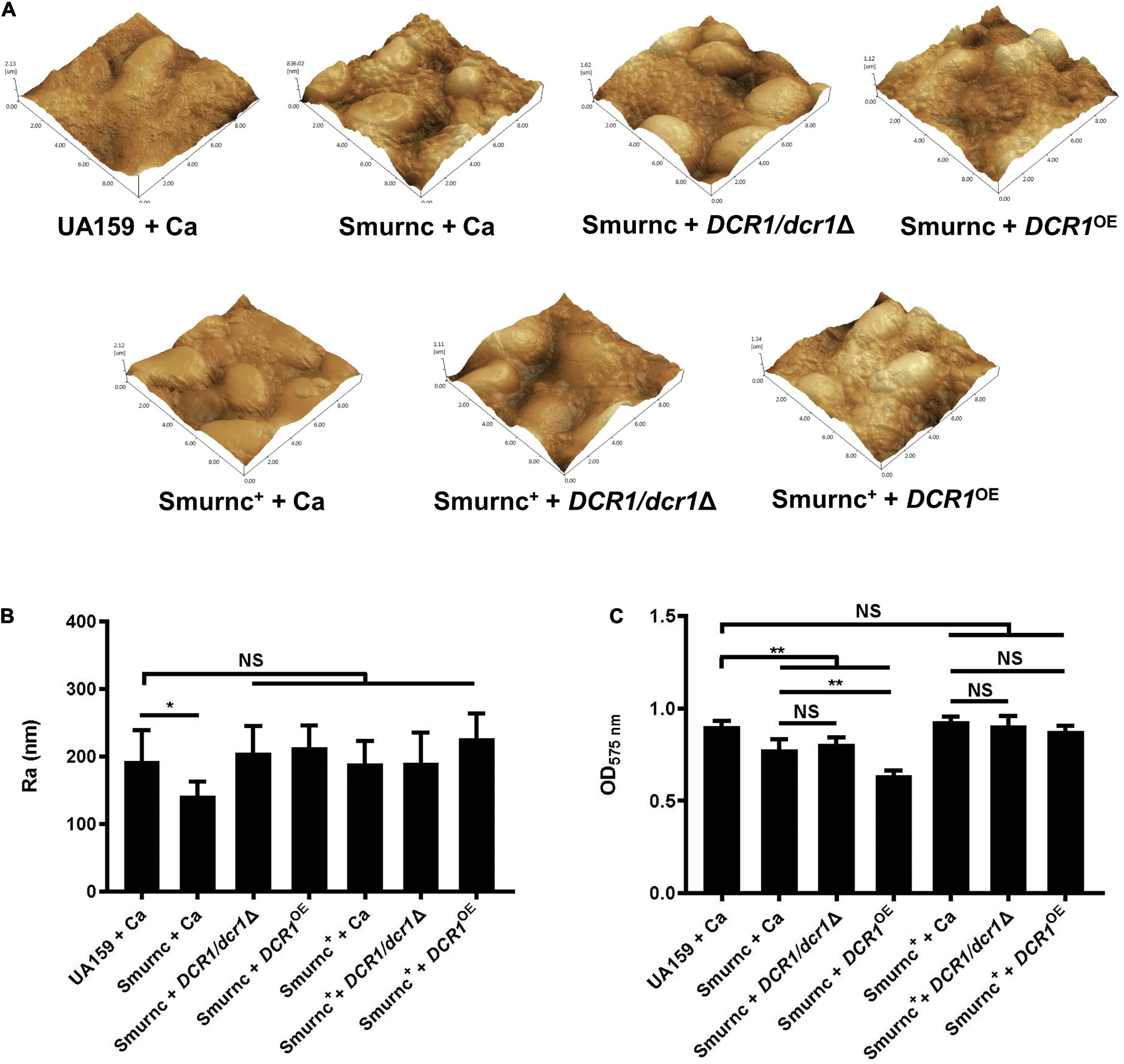

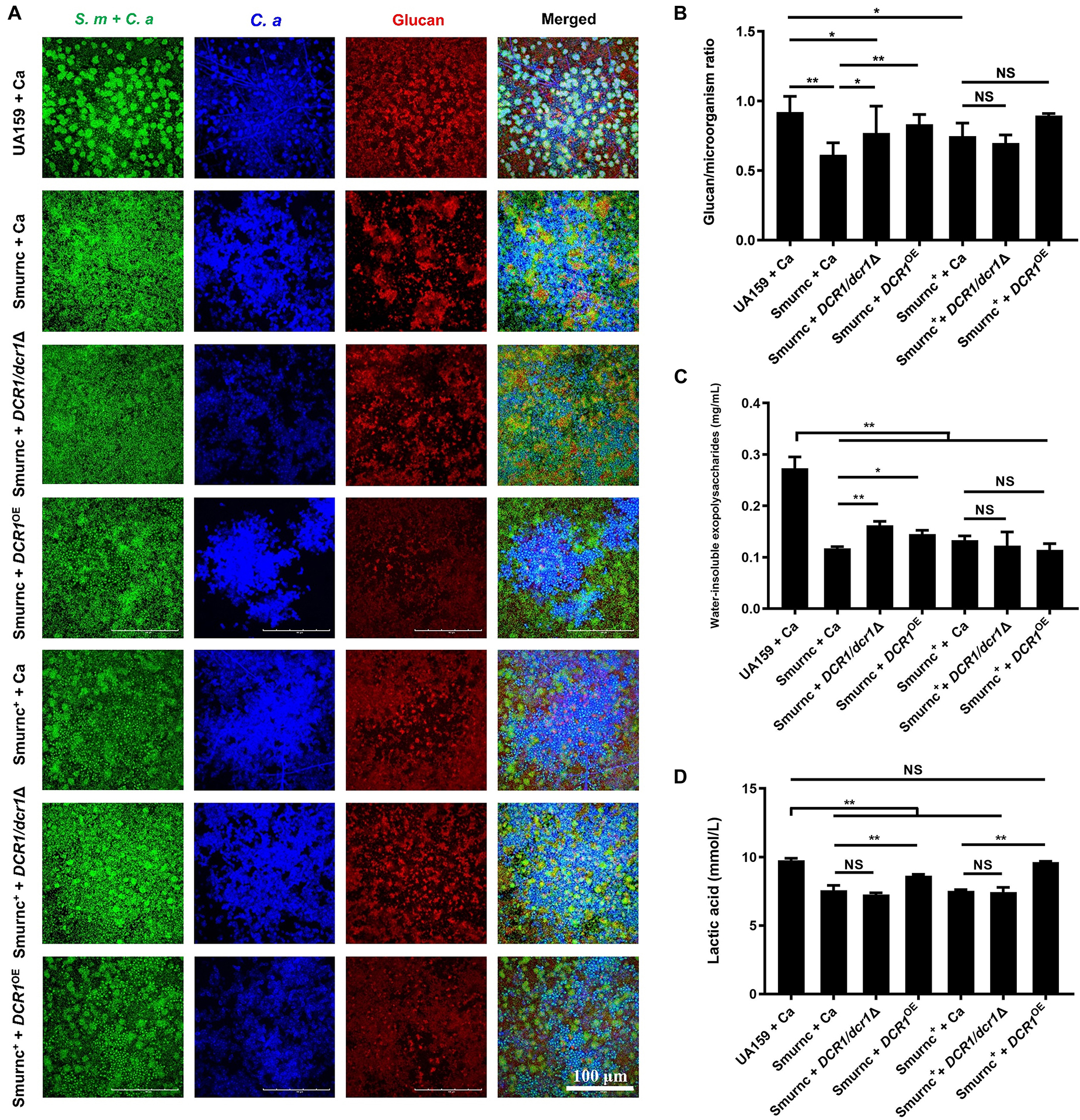

Microorganisms appeared to gather into condensed clusters surrounded by abundant extracellular polymeric substances to form the 3D structure in biofilms of the UA159 + Ca or Smurnc+ + Ca group (Figures 2A,D,G). Conversely, the biofilm of Smurnc + Ca had scattered microcolonies with barren extracellular matrix (Figures 2A,D,G); this was in line with the results of quantitative calculation which affirmed that the glucan/microorganisms ratio and total content of water-insoluble EPS became diminished in Smurnc + Ca biofilm when compared to UA159 + Ca or Smurnc+ + Ca (Figures 2E,F and Supplementary Figure 3). The fungi among Smurnc + Ca biofilms were predominantly yeast cells, whereas C. albicans was present mainly in the hyphal form in the UA159 + Ca or Smurnc+ + Ca group (Figures 2A,D). Moreover, the biomass of Smurnc + Ca dual-species biofilms was attenuated significantly, which was accompanied by the conspicuous reduction of biofilm roughness and acid production (Figures 2B,C,H). To further explore the combined effect of rnc and DCR1 on the cariogenic characteristics of cross-kingdom biofilms, S. mutans rnc mutant strains were co-cultured with C. albicans DCR1 mutant strains. There were principally C. albicans yeast cells in the biofilms containing Smurnc, DCR1/dcr1Δ, or DCR1OE (Figures 3, 5A). Notably, when S. mutans was defective in rnc, the dual-species biofilms were devoid of scaffold structure and had the least and loosest matrix compared to other groups (Figure 3), resulting in planar architecture with exposed microbial cells, reduced biomass, and low surface roughness (Figure 4). AFM detection also revealed that the cells were densely immersed in the flourishing extracellular matrix in the biofilms of Smurnc+ + Ca, Smurnc+ + DCR1/dcr1Δ, and Smurnc+ + DCR1OE, which was similar to the UA159 + Ca group (Figure 4A). Bacteria were sparsely distributed in biofilms composed of Smurnc and C. albicans wild-type strain or mutant strains (Figure 5A). Quantitative analysis showed that the Smurnc + Ca biofilm exhibited a markedly lower glucan/microorganism volume ratio, restrained synthesis of water-insoluble EPS, and impaired lactic acid production (Figures 5B–D). Taken together, the rnc gene in S. mutans has more pronounced regulatory effects on the cariogenic properties of cross-kingdom biofilms than DCR1. Consequently, we chose biofilms consisting of UA159 + Ca and Smurnc + Ca and Smurnc+ + Ca for the following research.

Figure 2. The regulation of rnc gene in cariogenic characteristics of cross-kingdom biofilm. (A) SEM observation of biofilm architecture. Blue arrows, S. mutans; red arrows, C. albicans hyphae; yellow arrows, C. albicans yeast cells. Images were taken at 1,000 × (scale bar, 100 μm), 5,000 × (scale bar, 20 μm), and 10,000 × (scale bar, 10 μm) magnifications, respectively. (B) CV microtiter assay was used to quantify the biofilm biomass. (C) Lactic acid generation was assessed by the Lactic Acid Assay Kit. (D,E) Exopolysaccharide production and distribution in biofilms were visualized by CLSM. Green, total microbes; blue, C. albicans; red, glucan. The glucan to microbes ratio was calculated using Imaris version 7.2.3. (F) Water-insoluble exopolysaccharides from biofilms were measured by the anthrone method. (G,H) Biofilm morphology was detected by AFM, and the surface roughness indicated by Ra (nm) was evaluated. Experiments were performed in biological triplicate. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Figure 3. The effects of genes coding RNase III on the architecture of cross-kingdom biofilms were observed by SEM. Blue arrows, S. mutans; red arrows, C. albicans hyphae; yellow arrows, C. albicans yeast cells. All images were taken at 1,000 × (scale bar, 100 μm), 5,000 × (scale bar, 20 μm), and 10,000 × (scale bar, 10 μm) magnifications, respectively.

Figure 4. The genes coding RNase III modulated the formation and surface characteristics of cross-kingdom biofilms. (A,B) Biofilm morphology and surface roughness (Ra) were tested by AFM. (C) Biofilm volume was examined by the CV microtiter assay. Experiments were performed in biological triplicate. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Figure 5. The genes coding RNase III regulated the exopolysaccharides synthesis and lactic acid production of cross-kingdom biofilms. (A,B) Exopolysaccharide production and distribution in biofilms were visualized by CLSM. Green, total microbes; blue, C. albicans; red, glucan and the ratio of exopolysaccharides to microbes was calculated. (C) Water-insoluble exopolysaccharides of biofilms were quantified by the anthrone method. (D) Lactic acid production was detected by the Lactic Acid Assay Kit. Experiments were performed in biological triplicate. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

The rnc gene affected virulence factor expression and the pathways of polysaccharide metabolism in Candida albicans

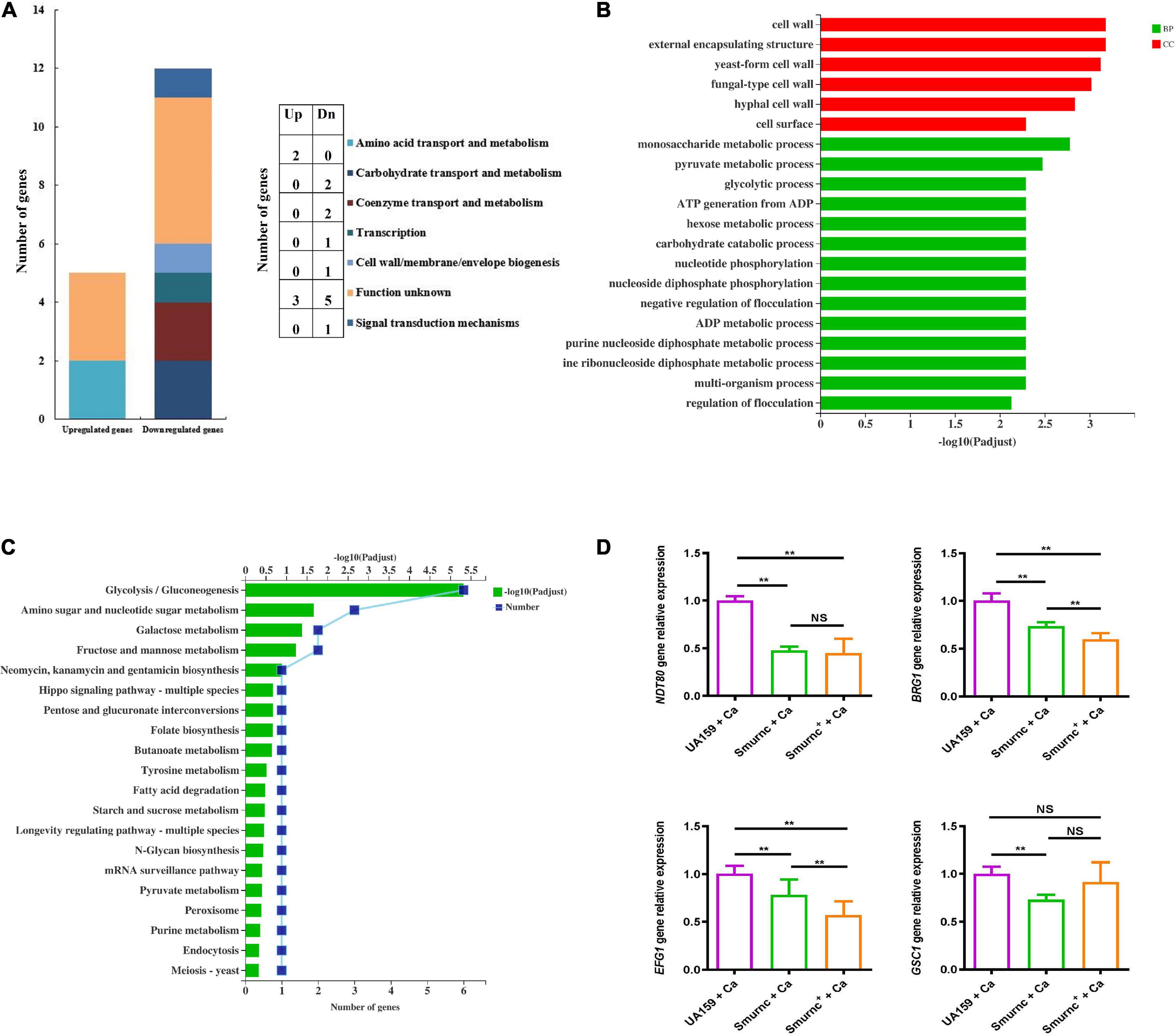

To further investigate the effects of rnc on the biological properties of C. albicans in the cross-kingdom biofilm, the virulence gene transcription level and pathway alterations were revealed by qRT-PCR, RNA-seq, and bioinformatics. The COG results showed that 12 fungal genes were observably downregulated and 5 fungal genes were upregulated in Smurnc + Ca biofilms compared to UA159 + Ca biofilms (Figure 6A). These genes are related mainly to carbohydrate bioprocess, cell wall biogenesis, signal transduction, and transcription (Figure 6A). GO demonstrated that the majority of downregulated genes were involved in yeast-hyphae transformation, monosaccharide metabolic processes, and pyruvate metabolism (Figure 6B). Through the KEGG pathway analysis, C. albicans showed decreased glycolysis/gluconeogenesis, galactose metabolism, and fructose and mannose metabolism (Figure 6C), suggesting that the C. albicans pathways associated with carbohydrate metabolism and pyruvate metabolism were suppressed in biofilms of Smurnc + Ca compared to the UA159 + Ca group (Figures 6B,C). Transcriptome data were further confirmed by qRT-PCR which illustrated that the rnc mutant strains significantly downregulated the expression of C. albicans genes relevant to biofilm formation (BRG1, NDT80, and EFG1) compared with UA159 (Figure 6D). The transcriptional level of the C. albicans glucan synthesis gene GSC1 in Smurnc + C.a biofilm was depressed compared to that in UA159 + Ca or Smurnc+ + Ca biofilms (Figure 6D).

Figure 6. rnc gene was associated with the gene expression of virulence factors of C. albicans. Transcriptomic analysis of the Smurnc + Ca group compared to the UA159 + Ca group. (A) The differently expressed genes were classified by gene annotation based on COG. (B) Functional categories and enrichment analysis of differently down-expressed genes based on GO. (C) Functional categories and enrichment analysis of differently down-expressed genes based on KEGG. (D) The gene transcripts of C. albicans in the cross-kingdom biofilms were relatively quantified by RT-qPCR using ACT1 as a reference gene and interpreted as fold changes based on the UA159 + Ca group. Experiments were performed in biological triplicate. **P < 0.01.

Discussion

Biofilms are dynamic and organized communities in which microbial cells are packed with and embraced by EPS to form a 3D structure to resist environmental interference (Lobo et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2022). Microorganisms carry out complex life activities in biofilms; therefore, expounding the interactions between microorganisms in dual-species biofilms is paramount to developing management strategies for dental caries (Flemming et al., 2016). Among the dental plaque of ECC, S. mutans was always detected with C. albicans that can also produce acids and survive in an acidic environment, implying the important role of C. albicans in biofilm-induced caries (Yang et al., 2012). In previous studies, we found that the rnc gene was able to promote the synthesis and configuration of EPS, thus amplifying the cariogenicity of S. mutans (Lei et al., 2019, 2020; Lu et al., 2021). Here, our study provided new insights that the rnc gene of S. mutans and the DCR1 gene of C. albicans modulated extracellular polysaccharide synthesis, thus contributing to the cross-kingdom biofilm formation of S. mutans and C. albicans.

For the first time, we investigated the effects of the essential gene DCR1 on the biological characteristics of cross-kingdom biofilms. When the DCR1 expression level was changed, the arrangement of cell clusters in the biofilm was loose, and the 3D structure formed by the cells and matrix was not obvious (Figures 1A,D). The transformation of cells from yeast to hyphal type is an important virulence factor of C. albicans (Carlisle et al., 2009; Sapaar et al., 2014). C. albicans hyphae can express a variety of specific virulence factors such as adhesins and antioxidant defense proteins, which participate in the establishment of biofilm structure and immune escape (Greig et al., 2015; Noble et al., 2017). C. albicans was present mostly in the yeast form in biofilms containing DCR1/dcr1Δ or DCR1OE (Figures 1A,D), congruent with the downregulation of mycelium-related virulence factor genes in DCR1-mutant strains (Supplementary Figure 2). These results suggest that abnormalities in DCR1 could change the spatial structure of cross-kingdom biofilms. The roughness of the biofilm surface is conducive to providing a larger area for microbial adhesion and producing surfaces with low shear stress, which can protect the biofilm from elimination (Shen et al., 2015). Nevertheless, we found that the regulatory effect of DCR1 on biofilm roughness was limited (Figures 1G,H).

Extracellular polysaccharides are the main component as well as the vital cariogenic virulence factor of dental plaque biofilms (Koo et al., 2013). DCR1 regulated the ability of glucan metabolism of microbes but could not affect the biomass and water-insoluble EPS content of biofilms (Figures 1B,E,F). In dental plaque, the microbiome can ferment carbohydrates to produce lactic acid, reduce the pH of the biofilm microenvironment, and finally cause demineralization of tooth hard tissue (Valm, 2019; Gabe et al., 2020). From this point of view, DCR1 overexpression presumably facilitates ECC formation by enhancing acid production (Figures 1C, 5D). We conjectured that the gene expression associated with lactic acid production of the DCR1OE mutant may be regulated by siRNAs at the post-transcriptional level (Bernstein et al., 2012). Further studies are still needed to investigate the regulatory effects and underlying mechanisms of DCR1 on acid production of the cross-kingdom biofilm.

Although low- or over-expression of DCR1 could downregulate virulence genes related to biofilm formation of C. albicans, the water-insoluble EPS content and biomass of cross-kingdom biofilms of S. mutans and C. albicans did not change when DCR1 was expressed abnormally, implying that there are likely complex interactions between these two strains to seek advantages and avoid disadvantages, thus forming a micro-ecological environment that is more beneficial to resist external adverse factors (Arnold, 2022). In contrast, S. mutans was supposed to play a more pivotal role in regulating the formation of dual-species biofilms.

We further explored the role of rnc in the cariogenic characteristics of cross-kingdom biofilms. Biofilms with Smurnc lacked an obvious scaffold structure and had less matrix wrapped around the microbes, revealing that rnc assisted in the formation of the extracellular matrix of dual-species biofilms and led to changes in their morphological structure. The EPS layer in biofilms was a manifestation of the defective biofilm, which was devoid of stereoscopic architecture. Deletion of the rnc gene inhibited the EPS metabolism instead of completely eliminating EPS synthesis in S. mutans, consistent with the quantitative data detected by the anthrone assay and the visualized images obtained by CLSM. Therefore, rnc-deficient S. mutans has defective biofilms but still with an EPS layer compared to the UA159 + Ca group (Figure 3). When compared to the DCR1 gene, deficiency of rnc could conspicuously restrain extracellular polysaccharide synthesis, decrease surface roughness, and cause attenuated acid production, which diminished the construction of cariogenic dual-species biofilms. Meanwhile, changes induced by the lack of rnc possibly impacted C. albicans virulence by affecting its biological behavior, such as biofilm formation, which may ultimately repress the cross-kingdom biofilm.

Ndt80, EFG1, and BRG1 are important transcription factors involved in the formation of C. albicans biofilms. After the knockout of these genes, C. albicans cannot display normal biofilms in vivo or in vitro (Nobile et al., 2012). β-1,3 glucan is one of the three major components of the C. albicans extracellular matrix, and its synthesis pathway involves mainly the GSC1 gene (glucan synthase catalytic subunit 1), which amplifies biofilm formation and drug resistance by increasing the extracellular matrix (Mitchell et al., 2015). Based on the phenotype and gene expression results, we speculated that rnc expedited the formation of cross-kingdom biofilms through EPS anabolism and catabolism, also propitious to the growth and the upregulated expression of the virulence genes of C. albicans. Related biological activities of C. albicans, such as hyphal transformation, glucan synthesis, and biofilm development, could further improve the structure of cross-kingdom biofilms and give full play to biofilm cariogenic properties such as acid production. In this study, we elucidated that S. mutans may play a more prominent role in regulating the formation of dual-species biofilms. Therefore, although the virulence- or biofilm-associated genes such as BRG1 and EFG1 of C. albicans were significantly lower in Smurnc+ + Ca than in Smurnc + Ca, Smurnc + Ca might have defective biofilms because of the impaired EPS synthesis and biofilm establishment induced by the absence of rnc (Figure 6D). Moreover, the cross-kingdom biofilm of S. mutans and C. albicans may be modulated by C. albicans virulence genes in addition to BRG1 and EFG1, which need to be further explored.

Transcriptomics helped us clarify the specific molecular mechanism and main pathway by which the rnc gene affects C. albicans (Motaung et al., 2017). It is possible that the phenotype of different morphological transformations of C. albicans in the Smurnc + Ca group was attributed to the downregulation of cell wall-related genes (Figure 6B). The downregulated genes in glycometabolism pathways suggested that the deletion of rnc in S. mutans possibly impacted the polysaccharide synthesis of C. albicans in the cross-kingdom biofilms, leading to the disruption of biofilm formation. Pyruvate metabolism is an important way to generate lactic acid. In the Smurnc + Ca group, the significantly decreased lactic acid production might be associated with the weak acid production capacity of C. albicans caused by the downregulation of genes relevant to the pyruvate metabolism pathway.

In conclusion, both RNase III coding genes of S. mutans and C. albicans can regulate the biological characteristics of the cross-kingdom biofilm. The rnc gene of S. mutans was able to crucially promote the formation of cross-kingdom biofilms with cariogenic characteristics by affecting the synthesis and metabolism of EPS. At the same time, changes in the dual-species environment were conducive to hyphal transformation, biofilm formation, polysaccharide metabolism, and pyruvate metabolism in C. albicans. The DCR1 gene of C. albicans mainly played a role in improving the biofilm structure and affecting the development of the acidic microecological environment. This research may provide an avenue for exploring new targets for the effective prevention and treatment of ECC.

Data availability statement

The data presented in the study are deposited in the NCBI repository under BioProject accession number PRJNA854798 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/PRJNA854798).

Author contributions

TH, YY, and XW designed the experiments and revised and finalized the manuscript. YL, LL, and YD performed the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote and finalized the manuscript. HZ and MX contributed to data collection and analysis. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 31971196 and 82170948) and the Chengdu Key Industry R&D Support Plan Grant (Grant No. 2019-YF05-01090-SN). The funding sources had no role in the study design, data acquisition and analysis, or preparation of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2022.957879/full#supplementary-material

References

Arnold, A. E. (2022). Bacterial-fungal interactions: Bacteria take up residence in the house that Fungi built. Curr. Biol. 32, R327–R328. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2022.02.024

Basso, V., Znaidi, S., Lagage, V., Cabral, V., Schoenherr, F., LeibundGut-Landmann, S., et al. (2017). The two-component response regulator Skn7 belongs to a network of transcription factors regulating morphogenesis in Candida albicans and independently limits morphogenesis-induced ROS accumulation. Mol. Microbiol. 106, 157–182. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13758

Bernstein, D. A., Vyas, V. K., Weinberg, D. E., Drinnenberg, I. A., Bartel, D. P., and Fink, G. R. (2012). Candida albicans Dicer (CaDcr1) is required for efficient ribosomal and spliceosomal RNA maturation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 523–528. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118859109

Care, R. S., Trevethick, J., Binley, K. M., and Sudbery, P. E. (1999). The MET3 promoter: A new tool for Candida albicans molecular genetics. Mol. Microbiol. 34, 792–798. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01641.x

Carlisle, P. L., Banerjee, M., Lazzell, A., Monteagudo, C., Lopez-Ribot, J. L., and Kadosh, D. (2009). Expression levels of a filament-specific transcriptional regulator are sufficient to determine Candida albicans morphology and virulence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 599–604. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804061106

Chen, H., Zhang, B., Weir, M. D., Homayounfar, N., Fay, G. G., Martinho, F., et al. (2020). S. mutans gene-modification and antibacterial resin composite as dual strategy to suppress biofilm acid production and inhibit caries. J. Dent. 93:103278. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2020.103278

Deng, Y., Yang, Y., Zhang, B., Chen, H., Lu, Y., Ren, S., et al. (2021). The vicK gene of Streptococcus mutans mediates its cariogenicity via exopolysaccharides metabolism. Int. J. Oral. Sci. 13:45. doi: 10.1038/s41368-021-00149-x

Drinnenberg, I. A., Weinberg, D. E., Xie, K. T., Mower, J. P., Wolfe, K. H., Fink, G. R., et al. (2009). RNAi in budding yeast. Science 326, 544–550. doi: 10.1126/science.1176945

Duan, S., Li, M., Zhao, J., Yang, H., He, J., Lei, L., et al. (2021). A predictive nomogram: A cross-sectional study on a simple-to-use model for screening 12-year-old children for severe caries in middle schools. BMC Oral. Health 21:457. doi: 10.1186/s12903-021-01819-2

Ellepola, K., Truong, T., Liu, Y., Lin, Q., Lim, T. K., Lee, Y. M., et al. (2019). Multi-omics Analyses Reveal Synergistic Carbohydrate Metabolism in Streptococcus mutans-Candida albicans Mixed-Species Biofilms. Infect. Immun. 87:e00339–19. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00339-19

Flemming, H. C., Wingender, J., Szewzyk, U., Steinberg, P., Rice, S. A., and Kjelleberg, S. (2016). Biofilms: An emergent form of bacterial life. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 14, 563–575. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.94

Fonzi, W. A., and Irwin, M. Y. (1993). Isogenic strain construction and gene mapping in Candida albicans. Genetics 134, 717–728. doi: 10.1093/genetics/134.3.717

Gabe, V., Zeidan, M., Kacergius, T., Bratchikov, M., Falah, M., and Rayan, A. (2020). Lauryl Gallate Activity and Streptococcus mutans: Its Effects on Biofilm Formation, Acidogenicity and Gene Expression. Molecules 25:3685. doi: 10.3390/molecules25163685

Greig, J. A., Sudbery, I. M., Richardson, J. P., Naglik, J. R., Wang, Y., and Sudbery, P. E. (2015). Cell cycle-independent phospho-regulation of Fkh2 during hyphal growth regulates Candida albicans pathogenesis. PLoS Pathog. 11:e1004630. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004630

He, J., Kim, D., Zhou, X., Ahn, S. J., Burne, R. A., Richards, V. P., et al. (2017). RNA-Seq Reveals Enhanced Sugar Metabolism in Streptococcus mutans Co-cultured with Candida albicans within Mixed-Species Biofilms. Front. Microbiol. 8:1036. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01036

Hwang, G., Liu, Y., Kim, D., Li, Y., Krysan, D. J., and Koo, H. (2017). Candida albicans mannans mediate Streptococcus mutans exoenzyme GtfB binding to modulate cross-kingdom biofilm development in vivo. PLoS Pathog. 13:e1006407. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006407

James, S. L., Abate, D., Abate, K. H., Abay, S. M., Abbafati, C., Abbasi, N., et al. (2018). Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 392, 1789–1858. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(18)32279-7

Janik, A., Niewiadomska, M., Perlinska-Lenart, U., Lenart, J., Kolakowski, D., Skorupinska-Tudek, K., et al. (2019). Inhibition of Dephosphorylation of Dolichyl Diphosphate Alters the Synthesis of Dolichol and Hinders Protein N-Glycosylation and Morphological Transitions in Candida albicans. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20:5067. doi: 10.3390/ijms20205067

Jia, X. M., Wang, Y., Zhang, J. D., Tan, H. Y., Jiang, Y. Y., and Gu, J. (2011). CaIPF14030 negatively modulates intracellular ATP levels during the development of azole resistance in Candida albicans. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 32, 512–518. doi: 10.1038/aps.2010.232

Khoury, Z. H., Vila, T., Puthran, T. R., Sultan, A. S., Montelongo-Jauregui, D., Melo, M. A. S., et al. (2020). The Role of Candida albicans Secreted Polysaccharides in Augmenting Streptococcus mutans Adherence and Mixed Biofilm Formation: In vitro and in vivo Studies. Front. Microbiol. 11:307. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.00307

Kim, D., Liu, Y., Benhamou, R. I., Sanchez, H., Simon-Soro, A., Li, Y., et al. (2018). Bacterial-derived exopolysaccharides enhance antifungal drug tolerance in a cross-kingdom oral biofilm. ISME J. 12, 1427–1442. doi: 10.1038/s41396-018-0113-1

Koo, H., Allan, R. N., Howlin, R. P., Stoodley, P., and Hall-Stoodley, L. (2017). Targeting microbial biofilms: Current and prospective therapeutic strategies. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 15, 740–755. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2017.99

Koo, H., Falsetta, M. L., and Klein, M. I. (2013). The exopolysaccharide matrix: A virulence determinant of cariogenic biofilm. J. Dent. Res. 92, 1065–1073. doi: 10.1177/0022034513504218

Lau, P. C., Sung, C. K., Lee, J. H., Morrison, D. A., and Cvitkovitch, D. G. (2002). PCR ligation mutagenesis in transformable streptococci: Application and efficiency. J. Microbiol. Methods 49, 193–205. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7012(01)00369-4

Lei, L., Stipp, R. N., Chen, T., Wu, S. Z., Hu, T., and Duncan, M. J. (2018). Activity of Streptococcus mutans VicR Is Modulated by Antisense RNA. J. Dent. Res. 97, 1477–1484. doi: 10.1177/0022034518781765

Lei, L., Yang, Y., Yang, Y., Wu, S., Ma, X., Mao, M., et al. (2019). Mechanisms by Which Small RNAs Affect Bacterial Activity. J. Dent. Res. 98, 1315–1323. doi: 10.1177/0022034519876898

Lei, L., Zhang, B., Mao, M., Chen, H., Wu, S., Deng, Y., et al. (2020). Carbohydrate Metabolism Regulated by Antisense vicR RNA in Cariogenicity. J. Dent. Res. 99, 204–213. doi: 10.1177/0022034519890570

Lemos, J. A., Palmer, S. R., Zeng, L., Wen, Z. T., Kajfasz, J. K., Freires, I. A., et al. (2019). The Biology of Streptococcus mutans. Microbiol. Spectr. 7:10.1128/microbiolspec.GPP3-0051-2018. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.GPP3-0051-2018

Liu, S., Qiu, W., Zhang, K., Zhou, X., Ren, B., He, J., et al. (2017). Nicotine Enhances Interspecies Relationship between Streptococcus mutans and Candida albicans. Biomed. Res. Int. 2017:7953920. doi: 10.1155/2017/7953920

Lobo, C. I. V., Rinaldi, T. B., Christiano, C. M. S., De Sales Leite, L., Barbugli, P. A., and Klein, M. I. (2019). Dual-species biofilms of Streptococcus mutans and Candida albicans exhibit more biomass and are mutually beneficial compared with single-species biofilms. J. Oral. Microbiol. 11:1581520. doi: 10.1080/20002297.2019.1581520

Lu, Y., Zhang, H., Li, M., Mao, M., Song, J., Deng, Y., et al. (2021). The rnc Gene Regulates the Microstructure of Exopolysaccharide in the Biofilm of Streptococcus mutans through the beta-Monosaccharides. Caries Res. 55, 534–545. doi: 10.1159/000518462

Mao, Y., Kalb, V. F., and Wong, B. (1999). Overexpression of a dominant-negative allele of SEC4 inhibits growth and protein secretion in Candida albicans. J. Bacteriol. 181, 7235–7242. doi: 10.1128/JB.181.23.7235-7242.1999

Mitchell, K. F., Zarnowski, R., Sanchez, H., Edward, J. A., Reinicke, E. L., Nett, J. E., et al. (2015). Community participation in biofilm matrix assembly and function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, 4092–4097. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1421437112

Motaung, T. E., Ells, R., Pohl, C. H., Albertyn, J., and Tsilo, T. J. (2017). Genome-wide functional analysis in Candida albicans. Virulence 8, 1563–1579. doi: 10.1080/21505594.2017.1292198

Mustafa, M., Alamri, H. M., Almokhatieb, A. A., Alqahtani, A. R., Alayad, A. S., and Divakar, D. D. (2022). Effectiveness of antimicrobial photodynamic therapy as an adjunct to mechanical instrumentation in reducing counts of Enterococcus faecalis and Candida albicans from C-shaped root canals. Photodermatol. Photoimmunol. Photomed. 38, 328–333. doi: 10.1111/phpp.12751

Nobile, C. J., Fox, E. P., Nett, J. E., Sorrells, T. R., Mitrovich, Q. M., Hernday, A. D., et al. (2012). A recently evolved transcriptional network controls biofilm development in Candida albicans. Cell 148, 126–138. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.048

Noble, S. M., Gianetti, B. A., and Witchley, J. N. (2017). Candida albicans cell-type switching and functional plasticity in the mammalian host. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 15, 96–108. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.157

Peres, M. A., Macpherson, L. M. D., Weyant, R. J., Daly, B., Venturelli, R., Mathur, M. R., et al. (2019). Oral diseases: A global public health challenge. Lancet 394, 249–260. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(19)31146-8

Ponde, N. O., Lortal, L., Ramage, G., Naglik, J. R., and Richardson, J. P. (2021). Candida albicans biofilms and polymicrobial interactions. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 47, 91–111. doi: 10.1080/1040841X.2020.1843400

Punjabi, V., Patel, S., Pathak, J., and Swain, N. (2020). Comparative evaluation of staining efficacy of calcofluor white and acridine orange for detection of Candida species using fluorescence microscopy - A prospective microbiological study. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Pathol. 24, 81–86. doi: 10.4103/jomfp.JOMFP_315_18

Ramadugu, K., Bhaumik, D., Luo, T., Gicquelais, R. E., Lee, K. H., Stafford, E. B., et al. (2021). Maternal Oral Health Influences Infant Salivary Microbiome. J. Dent. Res. 100, 58–65. doi: 10.1177/0022034520947665

Sapaar, B., Nur, A., Hirota, K., Yumoto, H., Murakami, K., Amoh, T., et al. (2014). Effects of extracellular DNA from Candida albicans and pneumonia-related pathogens on Candida biofilm formation and hyphal transformation. J. Appl. Microbiol. 116, 1531–1542. doi: 10.1111/jam.12483

Shen, Y., Monroy, G. L., Derlon, N., Janjaroen, D., Huang, C., Morgenroth, E., et al. (2015). Role of biofilm roughness and hydrodynamic conditions in Legionella pneumophila adhesion to and detachment from simulated drinking water biofilms. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 4274–4282. doi: 10.1021/es505842v

Svensson, S. L., and Sharma, C. M. (2021). RNase III-mediated processing of a trans-acting bacterial sRNA and its cis-encoded antagonist. elife 10:e69064. doi: 10.7554/eLife.69064

Sztajer, H., Szafranski, S. P., Tomasch, J., Reck, M., Nimtz, M., Rohde, M., et al. (2014). Cross-feeding and interkingdom communication in dual-species biofilms of Streptococcus mutans and Candida albicans. ISME J. 8, 2256–2271. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2014.73

Valm, A. M. (2019). The Structure of Dental Plaque Microbial Communities in the Transition from Health to Dental Caries and Periodontal Disease. J. Mol. Biol. 431, 2957–2969. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2019.05.016

Wen, Z. T., Nguyen, A. H., Bitoun, J. P., Abranches, J., Baker, H. V., and Burne, R. A. (2011). Transcriptome analysis of LuxS-deficient Streptococcus mutans grown in biofilms. Mol. Oral. Microbiol. 26, 2–18. doi: 10.1111/j.2041-1014.2010.00581.x

Xiao, J., Grier, A., Faustoferri, R. C., Alzoubi, S., Gill, A. L., Feng, C., et al. (2018a). Association between Oral Candida and Bacteriome in Children with Severe ECC. J. Dent. Res. 97, 1468–1476. doi: 10.1177/0022034518790941

Xiao, J., Huang, X., Alkhers, N., Alzamil, H., Alzoubi, S., Wu, T. T., et al. (2018b). Candida albicans and Early Childhood Caries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Caries Res. 52, 102–112. doi: 10.1159/000481833

Yang, X. Q., Zhang, Q., Lu, L. Y., Yang, R., Liu, Y., and Zou, J. (2012). Genotypic distribution of Candida albicans in dental biofilm of Chinese children associated with severe early childhood caries. Arch. Oral. Biol. 57, 1048–1053. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2012.05.012

Yang, Y., Mao, M., Lei, L., Li, M., Yin, J., Ma, X., et al. (2019). Regulation of water-soluble glucan synthesis by the Streptococcus mutans dexA gene effects biofilm aggregation and cariogenic pathogenicity. Mol. Oral. Microbiol. 34, 51–63. doi: 10.1111/omi.12253

Zhang, H., Xia, M., Zhang, B., Zhang, Y., Chen, H., Deng, Y., et al. (2022). Sucrose selectively regulates Streptococcus mutans polysaccharide by GcrR. Environ. Microbiol. 24, 1395–1410. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.15887

Zhang, R., Wang, H., Tian, Y. Y., Yu, X., Hu, T., and Dummer, P. M. (2011a). Use of cone-beam computed tomography to evaluate root and canal morphology of mandibular molars in Chinese individuals. Int. Endod. J. 44, 990–999. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2011.01904.x

Zhang, R., Yang, H., Yu, X., Wang, H., Hu, T., and Dummer, P. M. (2011b). Use of CBCT to identify the morphology of maxillary permanent molar teeth in a Chinese subpopulation. Int. Endod. J. 44, 162–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2010.01826.x

Keywords: Streptococcus mutans, rnc gene, Candida albicans, DCR1 gene, cross-kingdom biofilm

Citation: Lu Y, Lei L, Deng Y, Zhang H, Xia M, Wei X, Yang Y and Hu T (2022) RNase III coding genes modulate the cross-kingdom biofilm of Streptococcus mutans and Candida albicans. Front. Microbiol. 13:957879. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.957879

Received: 31 May 2022; Accepted: 18 August 2022;

Published: 30 September 2022.

Edited by:

Fang Yang, Qingdao Municipal Hospital, ChinaReviewed by:

Dhirendra Kumar Singh, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, United StatesMegan L. Falsetta, University of Rochester, United States

Copyright © 2022 Lu, Lei, Deng, Zhang, Xia, Wei, Yang and Hu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yingming Yang, eW15YW5nQHNjdS5lZHUuY24=; Tao Hu, aHV0YW9Ac2N1LmVkdS5jbg==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Yangyu Lu1,2†

Yangyu Lu1,2† Lei Lei

Lei Lei Xi Wei

Xi Wei Yingming Yang

Yingming Yang Tao Hu

Tao Hu