- 1Department of Microbiology, Government College University Faisalabad, Faisalabad, Pakistan

- 2National Institute of Health, Islamabad, Pakistan

- 3Institute of Microbiology, University of Agriculture Faisalabad, Faisalabad, Pakistan

- 4National Risk Assessment Laboratory for Antimicrobial Resistance of Animal Original Bacteria, South China Agricultural University, Guangzhou, China

- 5Faculty of Life Science and Technology, Kunming University of Science and Technology, Kunming, China

Klebsiella pneumoniae is ubiquitous and known to be a notorious pathogen of humans, animals, and plant-based foods. K. pneumoniae is a recognized trafficker of antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) between and from different ecological niches. A total of 775 samples (n = 775) were collected from September 2017 to August 2019 from humans, animals, and environmental sources by applying the random convenient sampling technique. A total of 120 (15.7%) samples were confirmed as K. pneumoniae. The distribution of K. pneumoniae among humans, the environment, and animals was 17.1, 12.38, and 10%, respectively. Isolates have shown significant resistance against all the subjected antibiotics agents except colistin. ARGs profiling revealed that the highest percentage prevalence (67.5%) of blaCTX–M was estimated in the isolates, and various carbapenem resistance genes that were found in the study were blaNDM–1 (43.3%), blaOXA–48 (38%), and (1.67%) blaKPC–2. Overall, 21 distinct sequence types (ST) and 13 clonal complexes (CCs) were found through the multi-locus sequence typing (MLST) analysis. Taking together, the distribution of multi-drug resistance (MDR) K. pneumoniae clones in the community and associated environment is alarming for the health care system of the country. Health policymakers should consider the role of all the integral parts of humans, animals, and the associated environment intently to cope with this serious public and animal health concern.

Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a mounting health concern all over the world. The global expansion of the AMR is due to the excessive and irrational use of antibiotics in clinical settings and food-producing animals. Additionally, deprived sanitation facilities, overpopulation, and inadequate sewerage disposal systems are also vital contributing factors to the dissemination of AMR (Aslam et al., 2018). Globally AMR poses huge economic losses; only in the USA losses of $35 billion have been estimated (Cecchini et al., 2015; Ventola, 2015). By the year 2050, 444 million people of the world population would be affected by resistant infections and birth rates would be reduced significantly (Bartlett et al., 2013). In the absence of new antibiotics, AR poses a severe threat to human and animal health in association with their wider environment.

The interplay between various ecologies is critically significant regarding the AMR. There is a number of associated factors among humans, animals, and the wider environment which permit not only the dissemination of various pathogens but also facilitate the transmission of mobile genetic elements carrying the antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs). To develop pragmatic and useful predictions regarding AMR, we need to have adequate and comprehensive data about the dynamics of different antibiotics, multidrug-resistant (MDR) pathogens, and the presence of various resistance determinants in different hosts and the wide-ranging environment (Woolhouse et al., 2015).

The ecological range of Klebsiella pneumoniae in various hosts and environments has been well documented (Wyres and Holt, 2016). Since the 1970s, the ubiquitous distribution of K. pneumoniae has been reported, and it is known to be a contaminant of animal- and plant-based foods (Davis and Price, 2016). K. pneumoniae is a pathogenic Gram-negative bacterium, a member of the Enterobacterales. World Health Organization (WHO) declared the carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales (CRE) as a health threat of critical importance (Ventola, 2015).

Population genomics of K. pneumoniae revealed that it is characterized by mass scale diversified and deep-branching clonal groups. There are approximately 5,500 genes present in K. pneumoniae genomes, 2,000 genes shared amongst different strains, and approximately, 3,500 genes that have a major part of the AMR genes, which are collected from a wide-ranging pool (≥ 30,000) of protein-coding sequences. Only a few clonal groups from universally distributed K. pneumoniae proved dexterous to acquire ARGs (Wyres and Holt, 2016).

In Pakistan, available data are not significant, and routine surveillance at the national level has been overlooked. Lately, we reported the emergence of MDR K. pneumoniae in the hospital and veterinary settings (Chaudhry et al., 2019; Aslam et al., 2020; Chaudhry et al., 2020). Herein, the present study was designed to find out the distribution and genetic diversity of K. pneumoniae in humans, animals, and their associated environments.

Materials and methods

Sample collection

Using a random convenient sampling technique, a total of (n = 775) samples were collected by following standard aseptic conditions and microbiological procedures. In detail, clinical samples (n = 525) including urine samples (n = 122), tracheal aspirates (n = 89), wounds and pus (n = 158), and blood (n = 156) were collected from different hospitals. The environmental samples (n = 210), including wastewater (n = 39), were taken from hospital effluents and nearby communities, and other samples were collected from operation theater waste (n = 31), hospital sludge (n = 23), and ward waste (n = 19), and abattoir/farm wastewater (n = 65) and veterinary sludge/waste (n = 33) were collected from healthy and infected animals at public and private dairy farms and slaughterhouses. Veterinary source samples (n = 40) include milk (n = 18) and fecal samples (n = 22) from the animals.

Isolation and identification of Klebsiella pneumoniae

In brief, some of the samples including fecal swabs, abattoir samples, and ward and operation theater waste samples were dispensed into sterilized glass tubes containing 1 mL PBS followed by streaking on nutrient agar plates; on the other hand, the remaining samples including wastewater, clinical specimens, milk, and sludge samples were streaked directly on nutrient agar plates. Plates were incubated for 24 h at 37°C. Afterward, selective media named HiChrom Klebsiella Selective agar (Himedia®) was used for the isolation of K. pneumoniae. Biochemical characterization of the isolates was done by API 20E Kit and VITEK identification system (bioMérieux, France). For molecular identification of the isolates, 16S rDNA PCR was performed. A total of 35 PCR cycles were performed for the amplification after initial denaturation at 95°C for 3 min. The cycle specifications include: denaturation at 95°C for 35 s, annealing at 50°C for 30 s, extension at 72°C for 60 s, and a final extension was done at 72°C for 5 min. Subsequently, to visualize the amplified PCR product agarose (Thermo Fisher Scientific, United States) gel electrophoresis was performed and gel documentation system (Bio-Rad, United States) was used to read the PCR products.

Antibiotic susceptibility testing

For antibiotic resistance (AR) profiling of the isolates, different antibiotics with CLSI recommended concentrations were used (CLSI, 2018). Antibiotics used in the study were ampicillin 10 μg and piperacillin 100 μg, cefuroxime 30 μg, cefixime 5 μg, ceftriaxone 30 μg, and cefepime 30 μg, meropenem 10 μg, ciprofloxacin 5 μg, tetracycline 30 μg, and minocycline 30 μg, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole 1.25/23.75 μg, colistin 10 μg, and tigecycline 15 μg. Escherichia coli (ATCC-25922) was used as a quality control strain.

In addition to the disc diffusion method, the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of all the antibiotics in the study was determined through broth microdilution assay as described previously (Chaudhry et al., 2020). Precisely, freshly grown K. pneumoniae was used to make 0.5 McFarland standards. Different ranges (0.06–256 μg/mL) of antibiotics dilutions were made. Micro-titration plate wells having growth were used to take inoculum, which was streaked on Petri plates containing nutrient agar and incubated for 24 h at 37°C. Results were interpreted according to the CLSI, 2018 recommendations.

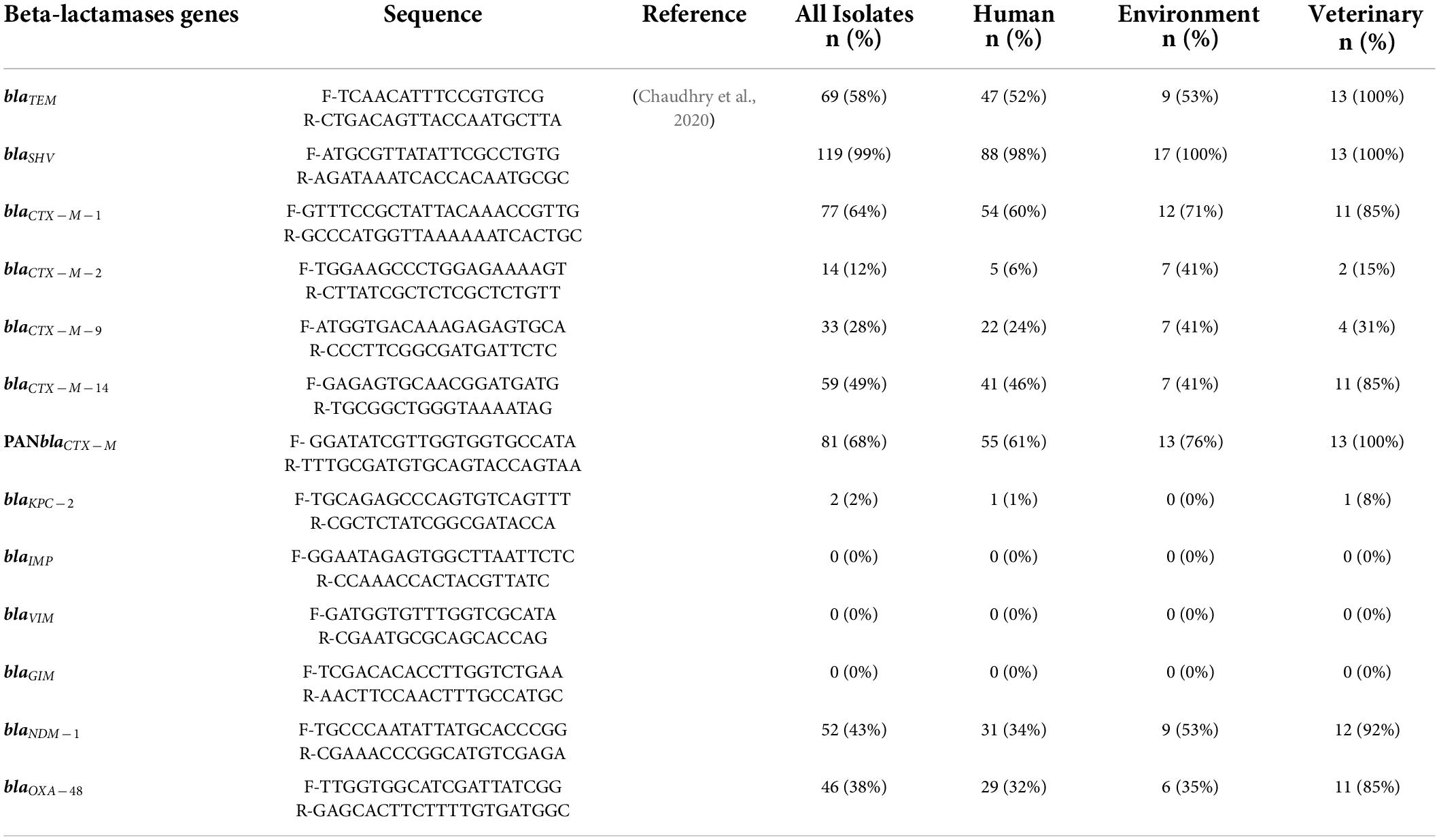

Detection of antibiotic resistance genes

DNA extraction was done by using a DNA Extraction kit (Qiagen™, Hilden, Germany). DNA quantification was performed through NanoDrop 2000 (Thermo Scientific™, United States), and DNA ≥ 60 ng/μl concentration was used for the further experiment. Extracted DNA from freshly grown isolates was used for genetic screening and the detection of β-lactamase genes, including ESBL genes (blaTEM, blaSHV, blaCTX–M–1, blaCTX–M–2, blaCTX–M–9, blaCTX–M–14, and PANCTX–M), carbapenemases genes (blaKPC, blaIMP, blaVIM, blaGIM, blaNDM–1, and blaOXA–48), fluoroquinolones (qnrA, qnrB, qnrS, parC, gyrA, and gyrB), tetracycline (tetA and tetB), and sulfonamides (sul1 and sul2) genes. The amplicons were sent for Sanger sequencing to Macrogen (Seoul, South Korea), and the obtained sequences were verified using the NCBI BLAST tool.

Multi-locus sequence typing

The MLST was carried out by following the Pasteur MLST scheme by the amplification of seven housekeeping genes of K. pneumoniae. The PCR was carried out by making up a 50 μl reaction mixture that comprises 25 μl of 2X PCR Master Mix (Thermo-Scientific, United States), and each primer (10 μM) was 1 and 2 μl sample DNA. The following PCR cycle conditions were set: initial denaturation at 94°C for 2 min and then 35 cycles of initial denaturation at 94°C for 20 s. The annealing temperature for all the genes were set at 50°C, except for tonB (45°C) and gapA (60°C), for 30 s and extension at 72°C for 30 s, and at the end, a final extension at 72°C for 5 min was performed in PCR Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad Inc., United States) (Diancourt et al., 2005). The amplified product of respective genes was analyzed on ethidium bromide-stained 1% agarose gel, the band size was assessed by GeneRuler 1 kb plus DNA ladder (Thermo-Scientific™, United States), and the snapshots were taken by gel documentation system (ChemiDoc™ XRS + System, Bio-Rad, United States). The genes were sequenced with the same forward and reverse sequencing primers from Macrogen™. For the determination of sequence types (ST), the MLST database for K. pneumoniae was referred according to the pasture scheme.1

Conjugation assay

To assess the transferability of K. pneumoniae isolates, conjugation assay was performed. Isolates of the study were kept as a donor while E. coli cells (Thermo Fisher®, United States) were used as the recipient bacterial cells. Confirmation of the transconjugants was done by streaking on Luria-Bertani (LB) agar supplemented with meropenem (MEM), imipenem (IMP), and ertapenem (ETP). Colony PCR of the transconjugants was also performed by using specific primers of blaNDM–1 blaKPC and blaOXA–48. MICs of the transconjugants were determined according to CLSI (2018) guidelines.

Results

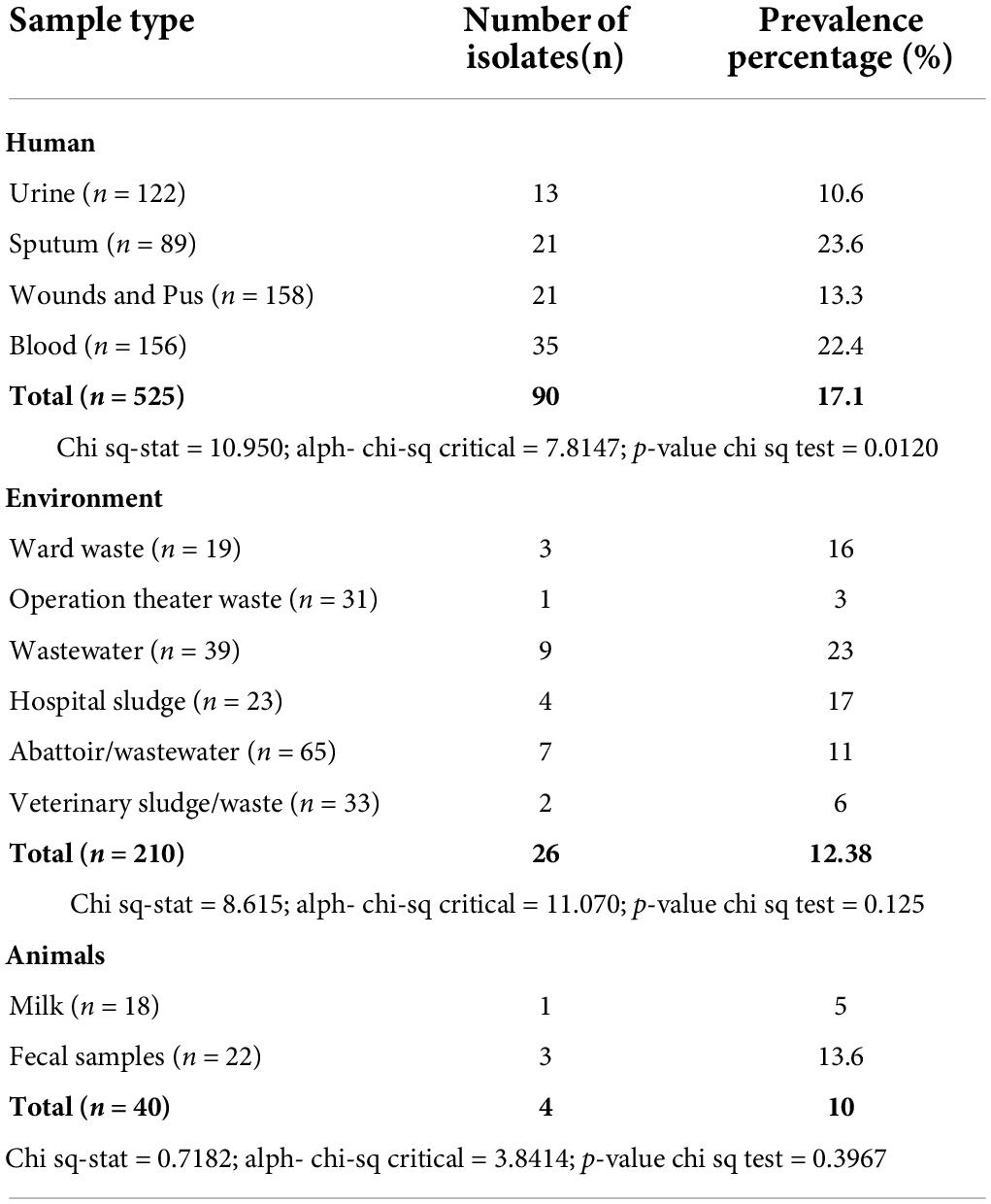

Distribution of Klebsiella pneumoniae among different sample sources

Overall, out of (n = 775) the collected samples, a total of 120 isolates were confirmed as K. pneumoniae. From n = 525 clinical samples, a total of 90 isolates were K. pneumoniae, while from (n = 210) environmental samples, a total of 26 isolates were K. pneumoniae, and out of veterinary samples (n = 40), a total of 4 isolates were confirmed K. pneumoniae (Table 1).

Table 1. Details of all the collected samples and percentage prevalence of K. pneumoniae from various sample sources.

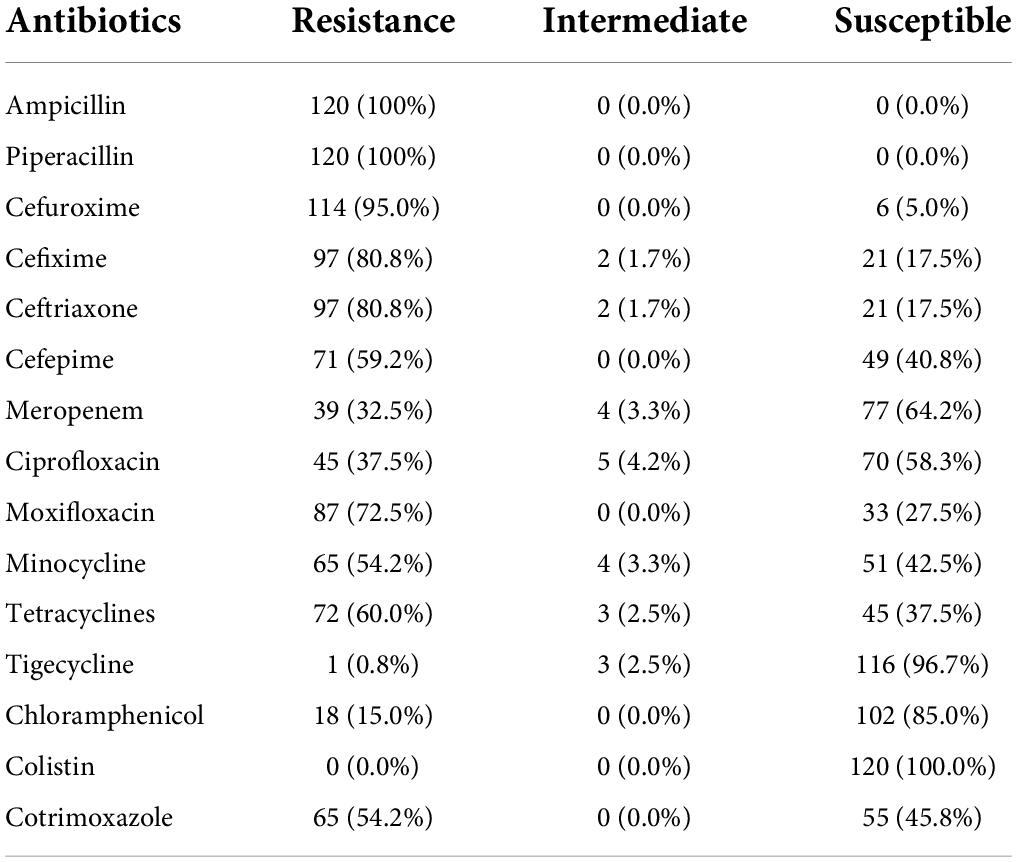

Resistance profiling

All isolates (100%; P < 0.05) were found resistant to ampicillin and piperacillin, while 114 (95.0%; P < 0.05) isolates were found resistant to cefuroxime. Moreover, 97 (80.8%; P < 0.05) isolates were found resistant to the third generation cephalosporins named cefixime and ceftriaxone, while 71 (59.2%; P < 0.05) isolates were found resistant to cefepime. The resistance to carbapenems (meropenem) was found in 39 (32.5%) isolates. Moreover, 87 (72.5%) and 45 (37.5%) isolates were found resistant to moxifloxacin and ciprofloxacin, respectively, while 65 (54.2%; P < 0.05) and 72 (60.0%; P < 0.05) isolates were resistant to minocycline and tetracycline, respectively. Although 65 (54.2%; P < 0.05) isolates were resistant to cotrimoxazole and 18 (15.0%) isolates were found resistant to chloramphenicol, only 01 isolate was found resistant to tigecycline. Fortunately, all the isolates were found susceptible to colistin (Table 2).

Table 2. Antibiotic resistance profile of indigenous K. pneumoniae isolates (n = 120) against all the antibiotics used in the study.

Detection of antibiotic resistance genes

Molecular AR profiling of all (120) the isolates revealed that blaSHV was detected in 92.5% followed by blaCTX–M (67.5%; P < 0.05), while other ARGs which were detected in the isolates showed the percentage prevalence as follows: blaTEM (57.5%; P < 0.05), blaCTX–M–1 (64%; P < 0.05), blaCTX–M–2, (11.6%), blaCTX–M–9 (27.5%), blaCTX–M–14 (49%), blaNDM–1 (43.3%), and blaOXA–48 (38%), and all the isolates were negative for blaVIM, blaGIM, and blaIMP. One of the most significant findings of the study was the detection of the blaKPC–2 gene among the 02 isolates i.e., one isolate from a clinical source and one from the veterinary source were found positive for blaKPC–2 (Table 3). In addition to the ESBL and carbapenemases genes, various other ARGs which were included in the study showed the following distribution patterns among K. pneumoniae isolates: tetA (40%), tetB (45%), qnrS (36.6%), qnrB (44%), sul1 (39%), and sul2 (44%), respectively.

Selected isolates after molecular identification and ARG’s detection were subjected to sequencing. Obtained sequences were used for BLAST analysis and submitted for NCBI GenBank accession numbers, which include MK620996.1, MK620997.1, MK620998.1, MK620999.1, MK621000.1, MK621001.1, MK621002.1, MK585512.1, MK585513.1, and MK458727.1.

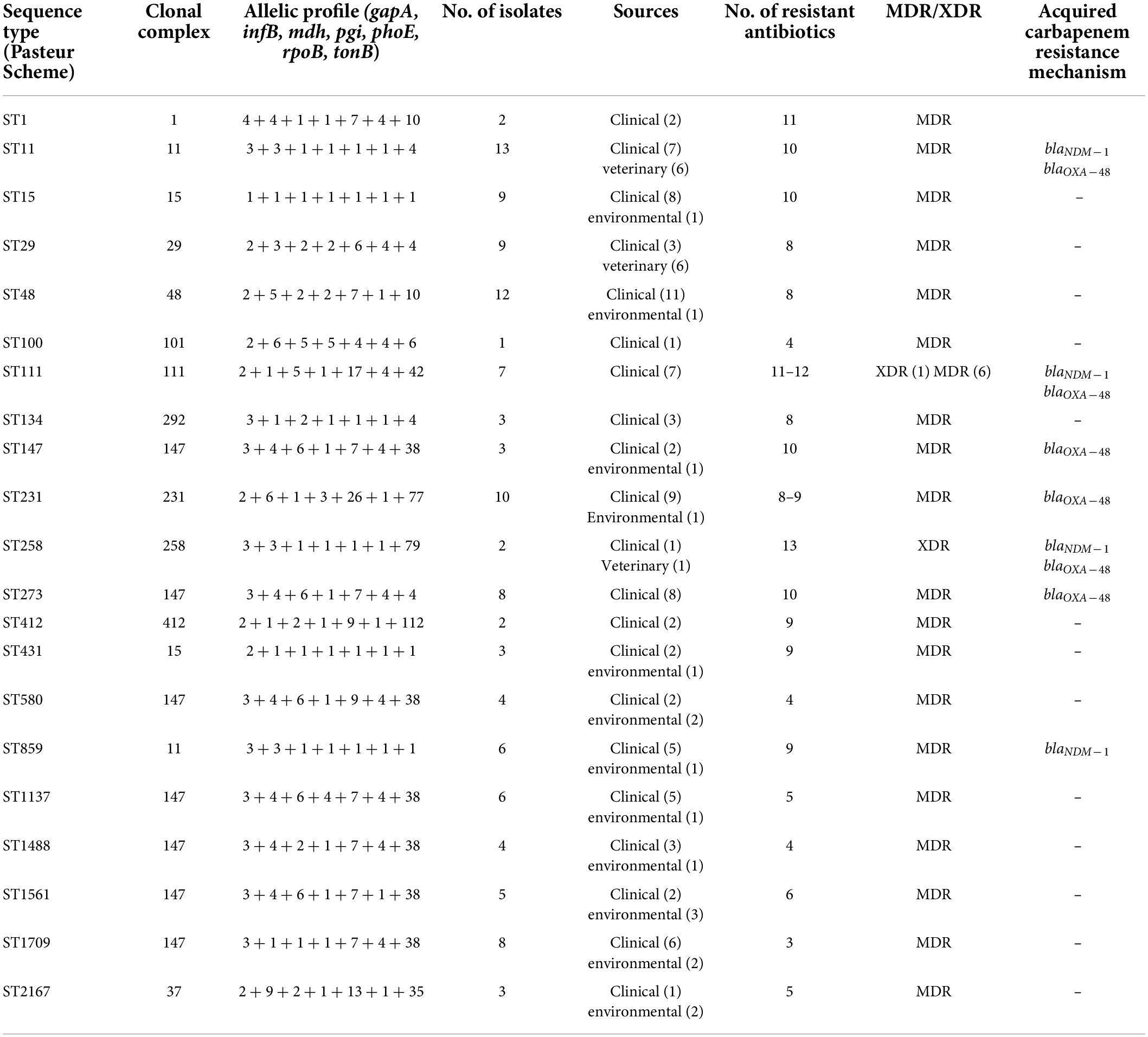

Distribution of sequence types

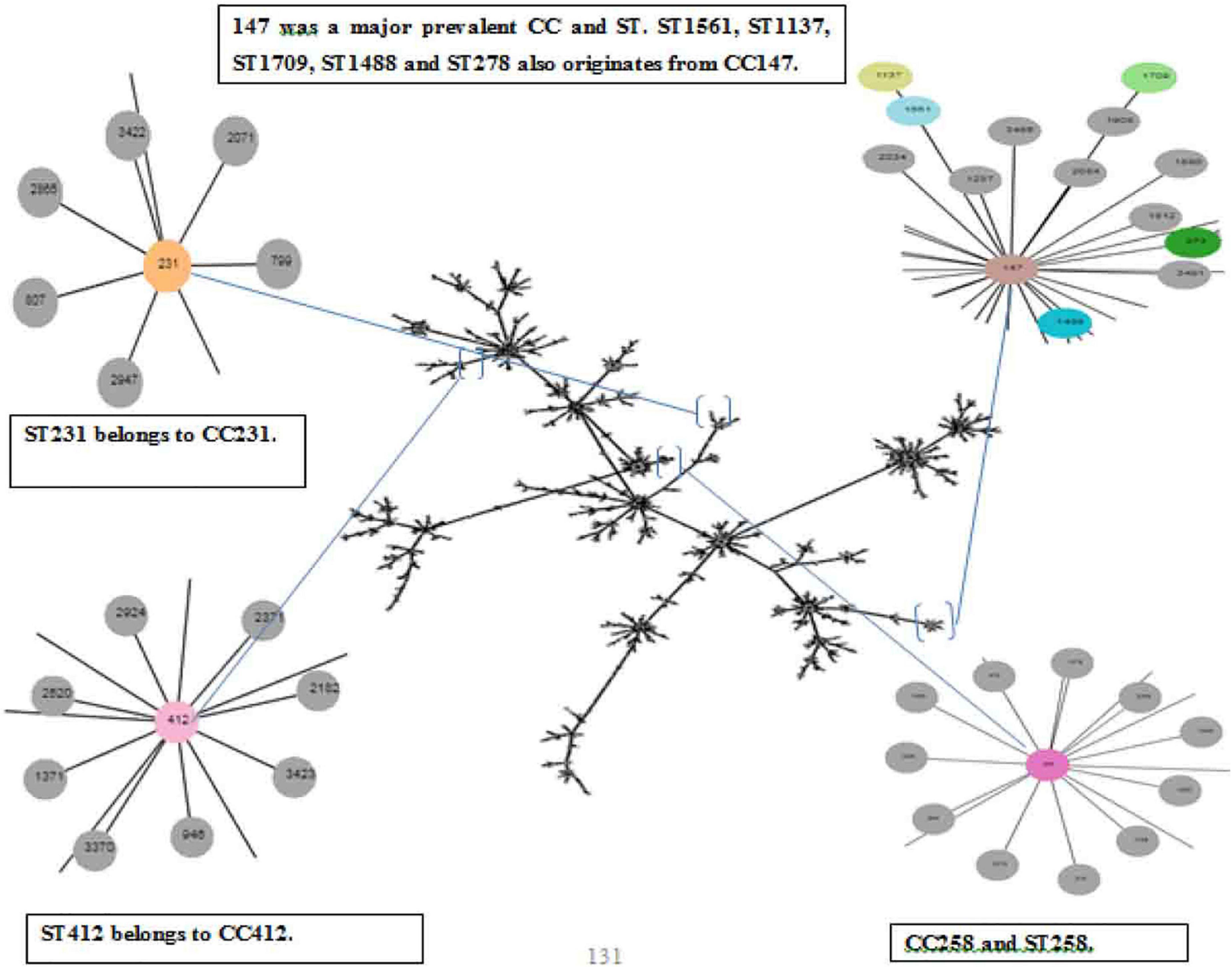

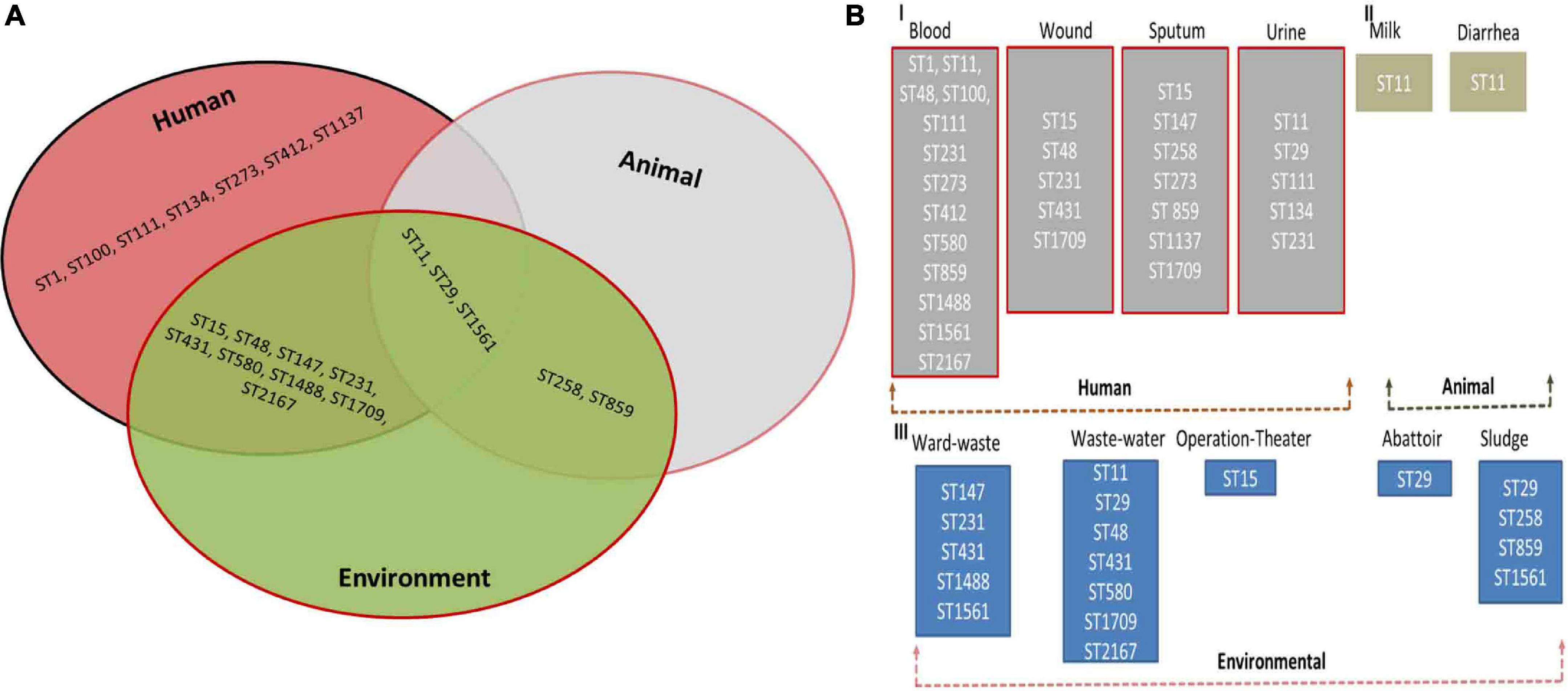

The panel of 120 K. pneumoniae isolates revealed 21 distinct sequence types (ST), while a total of 13 clonal complexes (CCs) were observed (Figure 1). The distribution of STs in humans, animals, and the environment has been shown in Figure 2A. Various STs found from clinical samples were ST1, ST100, ST111, ST134, ST274, and ST412 (Figure 2BI). ST11 was a single ST found in veterinary (animal) sources (milk and diarrhea, Figure 2BII), whereas different STs which were found in the isolates of environmental sources were also observed in the isolates of clinical sources, these STs were as follows: ST48, ST15, ST231, CC147, ST431, ST580, ST859, ST1137, ST1488, ST1561, ST1709, and ST2167 (Figure 2BIII). While all the STs observed in the isolates of veterinary and veterinary environment sources were also observed in the isolates of clinical sources, these STs were as follows: ST11, ST29, and ST258 (Figure 2A).

Figure 1. eBURST analysis (Phyloviz) of Klebsiella pneumoniae representing the STs and CCs, Partial snapshots of branches magnified and highlighted each CC and ST found in the study.

Figure 2. (A) Distribution of multilocus sequence types (STs) of Klebsiella pneumoniae in Human, Animal, and Environment. (B) Prevalence of multilocus sequence types (STs) in blood, wound, sputum, urine (Human) (I), milk and fecal (Animal) (II) and ward-waste, wastewater, operation-theater, Abattoir, and sludge (Environment) (III).

Thirteen isolates, comprising seven isolates from clinical and six isolates from veterinary sources, matched ST11 (P < 0.05). ST48 was the second most abundant sequence type corresponding to the 12 isolates and ST48 (P < 0.05) was the most commonly found ST in the human sources as the 11 clinical isolates. Both dominant STs were classified as MDR with high resistance profile against majorly used antibiotics. CC231 (ST231) was observed in 09 isolates. ST431 and ST231 STs were different from each other by single-locus variant (SLV), and ST15 was found to be the originator genotype of clonal complex CC15. Furthermore, the four diverse STs of CC147 including ST1137, ST1488, ST1561, and ST580 were also found to have double locus variants (DLV) to each other.

Another ST258 corresponded to the 1 + 1 isolate equally from sputum and veterinary sludge, which was designated as XDR with high resistance profile against 13 antibiotics and showed a marked presence of blakpc–2, blaNDM–1, and blaOXA–48. The presence of these carbapenems encoding genes was also evident in ST11, which is a SLV of ST258, but both belong to different CCs. There are few isolates of human and environmental origins that matched with ST1709 and ST2167, which were quite dissimilar to each other in allelic profiles, and all these isolates were found susceptible to all the antibiotics used in the study. Details of STs harboring carbapenem resistance genes are given in Table 4.

Conjugation validation

All the selected isolates displayed transferability, and colonies of the transconjugants were observed on LB agar plates containing MEM, IMP, and ETP. The MIC90 of these antibiotics (MEM, IMP, and ETP) against transconjugants were 32, 16, and 16 μg/mL, respectively. Various carbapenemases genes (blaNDM–1 blaKPC and blaOXA–48) were detected by colony PCR, which confirmed the transconjugants.

Discussion

The mounting crisis of AR is a global challenge that is affecting humans as well as animals in association with the wider environment. Irrational use of antibiotics in health care settings, veterinary and agricultural practices is a substantial contributing factor in the global expansion of AR. Moreover, poor sanitation and disposal systems associated with massive populations have a threatening impact on the dissemination of AR to the community (Adnan et al., 2017; Aslam et al., 2018; Baloch et al., 2018). Pakistan is one of the leading countries in the production of animal products, and the use of antibiotics in animals and veterinary practices is a routine matter in the country. Despite intense modernized farming, Pakistan still lacks sufficient data on the use and estimation of antibiotics in animals (Hassan Ali et al., 2010; Idrees et al., 2011; Khan et al., 2013; Adnan et al., 2017; Mohsin et al., 2017; Mohsin, 2019).

The findings of the present study showed that overall, 120 (15.7%) were confirmed K. pneumoniae isolated from various sources of humans, animals, and the environment (Figure 2A). It has been well established that K. pneumoniae can survive in different environments because of its large genome size (5.7 Mbps with 5,455 protein) than E. coli (5.1 Mbps with 4,915 genes) (Sudarwanto et al., 2015). A total of 90 (17.42%) K. pneumoniae isolates were obtained from clinical samples. Isolation of K. pneumoniae has been reported from various clinical specimens across Pakistan. Most of the isolates of the present study were obtained from respiratory samples, i.e., sputum (23.6%), blood samples (22.4%) followed by pus samples (13.3%) collected from various wounds and surgical sites, and urine samples (14.4%) collected from UTI-infected male and female patients. The is important and suggested that it may lead to hospital-acquired infection or put patients at risk of ventilator-associated pneumonia and bacteremia due to K. pneumoniae. Same findings have been reported from Aga Khan University Hospital, Karachi. Pakistan, where they also found comparable percentage prevalence in various sample sources, particularly blood samples (Khan et al., 2010b). The same study has also been reported from Lahore, Pakistan (Riaz et al., 2012), but they reported a low percentage prevalence of K. pneumoniae from various clinical samples; however, pus samples in this study were also the least possible clinical source of K. pneumoniae. Another study reported from Karachi Pakistan revealed comparable findings regarding the percentage prevalence (17%) of K. pneumoniae from urine and blood samples (Khan et al., 2010a).

In the present study, about 70% of the K. pneumoniae clinical isolates were found to be ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae, which is a very alarming health situation prevailing in Pakistan. Isolates exhibited various antibiotic resistance determinants (ARDs) e.g., blaTEM and blaCTX–M, which were associated with conferring the resistance against beta-lactam antibiotics. These findings were worrying because in local health settings most of the prescribed regimens are limited to a specific class of antibiotics. Same findings showing up to 70% ESBL producing K. pneumoniae have been reported by Shah et al. (2003), while another study reported 30% ESBL producing K. pneumoniae from Lahore (Ejaz et al., 2013). Comparable reports have been published from neighboring countries like India and Iran, where they found 56 and 59% ESBL producing K. pneumoniae from various samples, respectively (Jain and Mondal, 2007; Ghafourian et al., 2011). In a study from India, the prevalence of ESBL and carbapenemase-producing K. pneumoniae isolates were 47 and 17%, respectively (Wyres et al., 2020). In another study from India, 84% of K. pneumoniae isolates were ESBL producers whereas the carbapenem resistance phenotypes were observed in 66% of isolates (Bhaskar et al., 2019).

Additionally, a study conducted in the recent past found ESBL producing K. pneumoniae with a rate of 15.8% (Bukhari et al., 2016), the low percentage prevalence may be due to the small sampling fraction and a huge diversity of sample sources as compared to our studied samples. Worryingly, a significant percentage prevalence (32%) of carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae has also been detected in the present study. Isolates exhibited different ARGs which are responsible for the resistance against carbapenems e.g., blaKPC (1.67%), blaOXA (38.0%), and blaNDM–1 (43.3%), etc. It has been well characterized that K. pneumoniae displays carbapenem resistance by involving various mechanisms, like carbapenemases ARGs, outer membrane permeability alterations, and efflux pump system (Pitout et al., 2015). Few reports of carbapenem resistance in Pakistan have been published, and a recent study revealed the first blaOXA-181-producing carbapenem-resistant (CR) K. pneumoniae from Pakistan, which rang the alarm of pan-drug resistant (PDR) K. pneumoniae (Nahid et al., 2017). In a study from the largest tertiary care hospital in Bangladesh, the prevalence of carbapenem-resistant KP isolates was 30%. Most isolates were found to harbor blaNDM–1 i.e., 53% followed by blaNDM–5 (14%), blaOXA–181 (12%), and blaOXA–232 (10%) (Okanda et al., 2020).

From Pakistan, in livestock, there is barely any such report available to compare our findings. But the percentage prevalence estimated in the present study is closely relative to the findings of a study conducted in India, where they found a 6% percentage prevalence of Enterobacterales from various samples of veterinary sources, especially milk and fecal samples (Kar et al., 2015). The same sort of study has been conducted in England and Wales in 2011; they detected ESBLs-harboring bacteria in various samples of veterinary origin like fecal samples, farm premises samples, and waste milk (Randall et al., 2014). They also detected blaCTX–M in waste milk, and they also suggested the key role of the farm environment in the dissemination of ARGs. A study has been reported from Germany, where they have detected the plasmid-mediated ESBLs producing gram-negative bacteria from cattle suffering from mastitis (Freitag et al., 2017). A significant prevalence of CR K. pneumoniae in poultry meat has been reported in China (Wu et al., 2016). Although they have identified a list of ARDs like the findings of the study, they have also reported blaCTX–M as one of the most prevalent resistance genes in the samples. In a meta-analysis from India, the prevalence of ESBL-producing bacteria increased from 12% in 2013 to 33% in 2019 in veterinary settings. The species-wise prevalence of ESBL phenotypes was 5% in Pseudomonas spp., 9% in E. coli, and 10% in K. pneumoniae, which shows that the ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae is the leading ESBL-producing bacterial species in India (Kuralayanapalya et al., 2019).

Overall, a total of 21 discrete STs with their specific allelic pattern were identified from all the isolates. The most abundant ST found in the study was ST11; a total of 13 (70%) isolates were assigned with ST11, and among them 07 isolates were clinical specimens and 06 isolates were from veterinary samples. Overall, due to the unavailability of data on K. pneumoniae STs, we do not have such studies to corroborate our findings. In a retrospective study from Zhejiang, China from 2008 to 2018, it is reported that the prevalence of carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae increased from 2.5% (2008) to 15.8% (2018). Interestingly, the ST11 was the most common sequence type and blaKPC-2 was the most prevalent carbapenem-resistant determinant (Hu et al., 2020). In the recent past, sporadic reports of K. pneumoniae ST11 have been published from Pakistan (Qamar et al., 2018). In contrast to the findings which were specifically designed for blaNDM–1, the results of the present study revealed a comprehensive status of K. pneumoniae ST11 due to the molecular resistance pattern depicting various ARGs. The second most observed ST was the ST48; 12 isolates were allotted with the ST48, and among these isolates, 11 isolates belong to clinical origin while 01 sample was from an environmental source. ST11 and ST48 were found to be MDR as they showed a significant resistance pattern to almost all the antibiotics used in the study except colistin (Qamar et al., 2018).

To the best of our knowledge, this is the very first report describing the dissemination of blaKPC–2 producing K. pneumoniae ST258 at the human–environment interface from Pakistan. The global distribution of CG258 is well recognized and has been well reported. The findings of the study are partly in agreement with the available literature, as ST11, a group member of CG258 was the most abundant ST found in the study. Additionally, blaKPC–2 producing K. pneumoniae ST258 was also a novel finding from Pakistan. Globally, ST258 is known as a key etiology of MDR K. pneumoniae, especially carbapenemase-producing K. pneumoniae infections (Munoz-Price et al., 2013; Chen et al., 2014; Pitout et al., 2015).

Conclusion

In conclusion, the major findings of the present study strengthened the understanding of the vital resistant determinants of K. pneumoniae which are never reported from Pakistan. Additionally, genetic diversity among indigenous K. pneumoniae isolates from different sources enabled us to find out different STs from humans, animals, and the associated environment, which may be very helpful in the future to control the public and animal health menace caused by MDR K. pneumoniae. Although it is one of the comprehensive studies reported from Pakistan, it also has some limitations. Particularly, the present study described the genetic diversity in MDR K. pneumoniae based on MLST, while the genetic characterization based on whole genome sequence (WGS) analysis is lacking. In the future, a detailed investigation based on WGS surveillance of MDR K. pneumoniae could be a potential work plan to decipher the genetic relatedness of this pathogen at the human–animal–environment interface.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics statement

The study was conducted in a span of 2 years from September 2017 to August 2019; proper permission was granted by the Ethical Review Board (ERB) of Government College University, Faisalabad, Pakistan.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the Major Science and Technology Special Project of Yunnan Province (No. 2019ZF004) and the First People’s Hospital of Yunnan Province (202205AG070053-10 and KHBS-2022-008).

Acknowledgments

We thank all the participants involved in this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

References

Adnan, M., Khan, H., Kashif, J., Ahmad, S., Gohar, A., Ali, A., et al. (2017). Clonal expansion of sulfonamide resistant Escherichia coli isolates recovered from diarrheic calves. Pak. Vet. J. 37, 230–232.

Aslam, B., Chaudhry, T. H., Arshad, M. I., Alvi, R. F., Shahzad, N., Yasmeen, N., et al. (2020). The First bla(KPC) harboring Klebsiella pneumoniae ST258 strain isolated in Pakistan. Microb. Drug Resist. 26, 783–786. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2019.0420

Aslam, B., Wang, W., Arshad, M. I., Khurshid, M., Muzammil, S., Rasool, M. H., et al. (2018). Antibiotic resistance: a rundown of a global crisis. Infect. Drug Resist. 11, 1645–1658. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S173867

Baloch, Z., Aslam, B., Muzammil, S., Khurshid, M., Rasool, M. H., and Ma, K. (2018). Selection inversion: a probable tool against antibiotic resistance. Infect. Drug Resist. 11, 1903–1905. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S176759

Bartlett, J. G., Gilbert, D. N., and Spellberg, B. (2013). Seven ways to preserve the miracle of antibiotics. Clin Infect Dis 56, 1445–1450. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit070

Bhaskar, B. H., Mulki, S. S., Joshi, S., Adhikary, R., and Venkatesh, B. M. (2019). Molecular characterization of extended spectrum β-lactamase and carbapenemase producing Klebsiella pneumoniae from a tertiary care hospital. Indian J. Crit. Care Med. 23, 61–66. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10071-23118

Bukhari, A., Arshad, M., Raza, S., Azam, M., and Mohsin, M. (2016). Emergence of extended spectrum beta-lactamases-producing strains belonging to cefotaxime-M-1 class from intensive care units patients and environmental surfaces in Pakistan. Int. J. One Health 2, 69–74. doi: 10.14202/IJOH.2016.69-74

Cecchini, M., Langer, J., and Slawomirski, L. (2015). Antimicrobial resistance in G7 countries and beyond: economic issues, policies and options for action. Paris: Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, 1–75.

Chaudhry, T. H., Aslam, B., Arshad, M. I., Alvi, R. F., Muzammil, S., Yasmeen, N., et al. (2020). Emergence of bla (NDM-1) Harboring Klebsiella pneumoniae ST29 and ST11 in Veterinary Settings and Waste of Pakistan. Infect. Drug Resist. 13, 3033–3043. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S248091

Chaudhry, T. H., Aslam, B., Arshad, M. I., Nawaz, Z., and Waseem, M. (2019). Occurrence of ESBL-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in hospital settings and waste. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 32, 773–778.

Chen, L., Mathema, B., Chavda, K. D., Deleo, F. R., Bonomo, R. A., and Kreiswirth, B. N. (2014). Carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae: molecular and genetic decoding. Trends Microbiol. 22, 686–696. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2014.09.003

CLSI (2018). performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; twenty-eighth informational supplement. CLSI document M100 (ISBN 1-56238-839-8). Malvern, PA: CLSI.

Davis, G. S., and Price, L. B. (2016). Recent research examining links among klebsiella pneumoniae from food, food animals, and human extraintestinal infections. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 3, 128–135. doi: 10.1007/s40572-016-0089-9

Diancourt, L., Passet, V., Verhoef, J., Grimont, P. A., and Brisse, S. (2005). Multilocus sequence typing of Klebsiella pneumoniae nosocomial isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43, 4178–4182. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.8.4178-4182.2005

Ejaz, H., Ul-Haq, I., Mahmood, S., Zafar, A., and Mohsin Javed, M. (2013). Detection of extended-spectrum β-lactamases in Klebsiella pneumoniae: comparison of phenotypic characterization methods. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 29, 768–772. doi: 10.12669/pjms.293.3576

Freitag, C., Michael, G. B., Kadlec, K., Hassel, M., and Schwarz, S. (2017). Detection of plasmid-borne extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) genes in Escherichia coli isolates from bovine mastitis. Vet. Microbiol. 200, 151–156. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2016.08.010

Ghafourian, S., Bin Sekawi, Z., Sadeghifard, N., Mohebi, R., Kumari Neela, V., Maleki, A., et al. (2011). The prevalence of ESBLs Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates in some major hospitals, Iran. Open Microbiol. J. 5, 91–95. doi: 10.2174/1874285801105010091

Hassan Ali, N., Farooqui, A., Khan, A., Khan, A. Y., and Kazmi, S. U. (2010). Microbial contamination of raw meat and its environment in retail shops in Karachi, Pakistan. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries 4, 382–388. doi: 10.3855/jidc.599

Hu, Y., Liu, C., Shen, Z., Zhou, H., Cao, J., Chen, S., et al. (2020). Prevalence, risk factors and molecular epidemiology of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in patients from Zhejiang, China, 2008-2018. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 9, 1771–1779. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1799721

Idrees, M., Shah, M. A., Michael, S., Qamar, R., and Bokhari, H. (2011). Antimicrobial resistant Escherichia coli strains isolated from food animals in Pakistan. Pak. J. Zool. 43, 303–310.

Jain, A., and Mondal, R. (2007). Prevalence & antimicrobial resistance pattern of extended spectrum beta-lactamase producing Klebsiella spp isolated from cases of neonatal septicaemia. Indian J. Med. Res. 125, 89–94.

Kar, D., Bandyopadhyay, S., Bhattacharyya, D., Samanta, I., Mahanti, A., Nanda, P. K., et al. (2015). Molecular and phylogenetic characterization of multidrug resistant extended spectrum beta-lactamase producing Escherichia coli isolated from poultry and cattle in Odisha, India. Infect. Genet. Evol. 29, 82–90. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2014.11.003

Khan, E., Schneiders, T., Zafar, A., Aziz, E., Parekh, A., and Hasan, R. (2010b). Emergence of CTX-M Group 1-ESBL producing Klebsiella pneumonia from a tertiary care centre in Karachi, Pakistan. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries 4, 472–476. doi: 10.3855/jidc.674

Khan, E., Ejaz, M., Zafar, A., Jabeen, K., Shakoor, S., Inayat, R., et al. (2010a). Increased isolation of ESBL producing Klebsiella pneumoniae with emergence of carbapenem resistant isolates in Pakistan: report from a tertiary care hospital. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 60, 186–190.

Khan, G. A., Berglund, B., Khan, K. M., Lindgren, P. E., and Fick, J. (2013). Occurrence and abundance of antibiotics and resistance genes in rivers, canal and near drug formulation facilities–a study in Pakistan. PLoS One 8:e62712. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062712

Kuralayanapalya, S. P., Patil, S. S., Hamsapriya, S., Shinduja, R., Roy, P., and Amachawadi, R. G. (2019). Prevalence of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase producing bacteria from animal origin: a systematic review and meta-analysis report from India. PLoS One 14:e0221771. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0221771

Mohsin, M. (2019). The under reported issue of antibiotic-resistance in food-producing animals in Pakistan. Pak. Vet. J. 39, 323–328. doi: 10.29261/pakvetj/2019.037

Mohsin, M., Raza, S., Schaufler, K., Roschanski, N., Sarwar, F., Semmler, T., et al. (2017). High Prevalence of CTX-M-15-Type ESBL-Producing E. coli from migratory avian species in Pakistan. Front. Microbiol. 8:2476. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02476

Munoz-Price, L. S., Poirel, L., Bonomo, R. A., Schwaber, M. J., Daikos, G. L., Cormican, M., et al. (2013). Clinical epidemiology of the global expansion of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemases. Lancet Infect. Dis. 13, 785–796. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70190-7

Nahid, F., Zahra, R., and Sandegren, L. (2017). A blaOXA-181-harbouring multi-resistant ST147 Klebsiella pneumoniae isolate from Pakistan that represent an intermediate stage towards pan-drug resistance. PLoS One 12:e0189438. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0189438

Okanda, T., Haque, A., Koshikawa, T., Islam, A., Huda, Q., Takemura, H., et al. (2020). Characteristics of carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated in the intensive care unit of the largest tertiary hospital in Bangladesh. Front. Microbiol. 11:612020. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.612020

Pitout, J. D., Nordmann, P., and Poirel, L. (2015). Carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae, a key pathogen set for global nosocomial dominance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 59, 5873–5884. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01019-15

Qamar, M. U., Saleem, S., Toleman, M. A., Saqalein, M., Waseem, M., Nisar, M. A., et al. (2018). In vitro and in vivo activity of Manuka honey against NDM-1-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae ST11. Future Microbiol. 13, 13–26.

Randall, L., Heinrich, K., Horton, R., Brunton, L., Sharman, M., Bailey-Horne, V., et al. (2014). Detection of antibiotic residues and association of cefquinome residues with the occurrence of Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase (ESBL)-producing bacteria in waste milk samples from dairy farms in England and Wales in 2011. Res. Vet. Sci. 96, 15–24. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2013.10.009

Riaz, S., Faisal, M., and Hasnain, S. (2012). Prevalence and comparison of Beta-lactamase producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella spp from clinical and environmental sources in Lahore, Pakistan. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 6, 465–470. doi: 10.5897/AJMR11.1457

Shah, A. A., Hasan, F., Ahmed, S., and Hameed, A. (2003). Prevalence of extended-spectrum ss-Lactamases in Nosocomial and out-patients (Ambulatory). Pak. J. Med. Sci. 19, 187–191.

Sudarwanto, M., Akineden, Ö, Odenthal, S., Gross, M., and Usleber, E. (2015). Extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in bulk tank milk from dairy farms in Indonesia. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 12, 585–590. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2014.1895

Ventola, C. L. (2015). The antibiotic resistance crisis: part 1: causes and threats. P T 40, 277–283.

Woolhouse, M., Ward, M., Van Bunnik, B., and Farrar, J. (2015). Antimicrobial resistance in humans, livestock and the wider environment. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 370:20140083.

Wu, K., Spiegelman, D., Hou, T., Albanes, D., Allen, N. E., Berndt, S. I., et al. (2016). Associations between unprocessed red and processed meat, poultry, seafood and egg intake and the risk of prostate cancer: A pooled analysis of 15 prospective cohort studies. Int. J. Cancer 138, 2368–2382. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29973

Wyres, K. L., and Holt, K. E. (2016). Klebsiella pneumoniae population genomics and antimicrobial-resistant clones. Trends Microbiol. 24, 944–956. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2016.09.007

Keywords: transmission, antimicrobial resistance, human-animal-environment, MLST analysis, Pakistan

Citation: Aslam B, Chaudhry TH, Arshad MI, Muzammil S, Siddique AB, Yasmeen N, Khurshid M, Amir A, Salman M, Rasool MH, Xia X and Baloch Z (2022) Distribution and genetic diversity of multi-drug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae at the human–animal–environment interface in Pakistan. Front. Microbiol. 13:898248. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.898248

Received: 17 March 2022; Accepted: 05 July 2022;

Published: 06 September 2022.

Edited by:

Ziad Daoud, Central Michigan University, United StatesReviewed by:

Ruichao Li, Yangzhou University, ChinaVijayalakshmi Selvakumar, Kangwon National University, South Korea

Copyright © 2022 Aslam, Chaudhry, Arshad, Muzammil, Siddique, Yasmeen, Khurshid, Amir, Salman, Rasool, Xia and Baloch. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xueshan Xia, b2xpdmVyeGlhMjAwMEBhbGl5dW4uY29t; Zulqarnain Baloch, em5iYWxvb2NoQHlhaG9vLmNvbQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Bilal Aslam

Bilal Aslam Tamoor Hamid Chaudhry

Tamoor Hamid Chaudhry Muhammad Imran Arshad

Muhammad Imran Arshad Saima Muzammil1

Saima Muzammil1 Abu Baker Siddique

Abu Baker Siddique Nafeesa Yasmeen

Nafeesa Yasmeen Mohsin Khurshid

Mohsin Khurshid Afreenish Amir

Afreenish Amir Muhammad Salman

Muhammad Salman Muhammad Hidayat Rasool

Muhammad Hidayat Rasool Zulqarnain Baloch

Zulqarnain Baloch