95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

PERSPECTIVE article

Front. Microbiol. , 24 February 2022

Sec. Systems Microbiology

Volume 13 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2022.798917

This article is part of the Research Topic Insights in Systems Microbiology: 2021 View all 12 articles

Many studies shown that neurological diseases are associated with neural mitochondrial dysfunctions and microbiome composition alterations. Since mitochondria emerged from bacterial ancestors during endosymbiosis, mitochondria, and bacteria had analogous genomic characteristics, similar bioactive compounds and comparable energy metabolism pathways. Therefore, it is necessary to rationalize the interactions of intestinal microbiota with neural mitochondria. Recent studies have identified neural mitochondrial dysfunction as a critical pathogenic factor for the onset and progress of multiple neurological disorders, in which the non-negligible role of altered gut flora composition was increasingly noticed. Here, we proposed a new perspective of intestinal microbiota – neural mitochondria interaction as a communicating channel from gut to brain, which could help to extend the vision of gut-brain axis regulation and provide additional research directions on treatment and prevention of responsive neurological disorders.

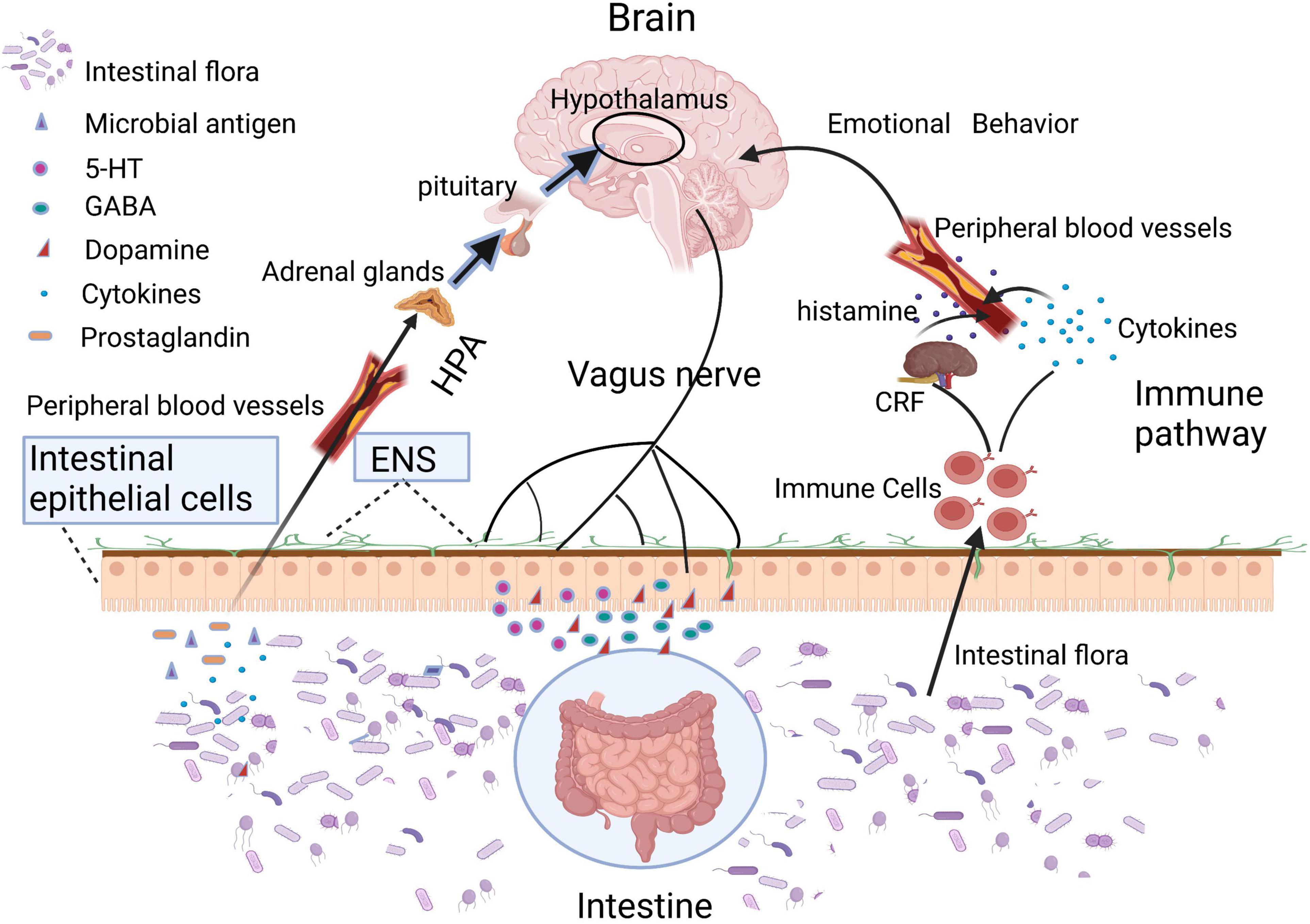

Human body is a super organism composed of own cells and resident microorganisms. In the long-term co-evolutionary process, human gut microbes, and the hosts constantly selected and adapted to each other, bringing about a close symbiotic relationship presently (Moeller et al., 2016). While microbiota exist in many body sites such as oral cavity, vagina, airways, and skin, etc., we focused only on the gut microbiota in this study as its interplay with systemic health is the most extensively documented (van de Guchte et al., 2018). In consideration of its distributive peculiarity, the gut microbiota was primarily proposed to have specific interactions with the host digestive system, which served as the main study topic for past decades. In recent years, a mass of research has identified that gut microbiota and corresponding bacterial metabolites can target the brain through various pathways, such as nervous conduction (enteric nerve, vagus nerve, etc.) (Fulling et al., 2019), hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis (McNeilly et al., 2010), and enteric endocrine and immune response (Fung, 2020; Morais et al., 2020), etc., (Figure 1). However, the specific regulatory mechanisms in these channels remain largely unclear.

Brain is one of the most energy-consuming organ in the body (Karbowski, 2007). Neural mitochondria can not only provide energy for maintaining brain homeostasis, but are also central regulators of cognitive function as well as fate determinant for neural stem cells (Khacho et al., 2016; Iwata et al., 2020). It has been widely reported that mitochondrial dysfunction can accelerate senescence of neural cells and facilitate the onset of multiple neurological diseases (Nguyen et al., 2014). In parallelly, a large amount of evidence confirmed that gut microbiota composition played critical roles in regulating the physiological and pathological functions of the brain. Therefore, considering the common ancestries, similar mechanisms, similar goals, and similar structures between gut microbiota and mitochondria (Franco-Obregon and Gilbert, 2017), is it possible that neural mitochondria are direct targets of intestinal microflora and function as key mediators regulating gut-brain interaction?

In Sagan (1967), first proposed the hypothesis that mitochondria evolved from bacteria. Currently, determining the nature of the bacterial lineages that gave rise to mitochondrial ancestors is still a hotly debated topic (Figure 1). Although many studies have already showed that mitochondrion originated from within the bacterial phylum Alphaproteobacteria, the phylogenetic relationship of the mitochondrial endosymbiont to extant Alphaproteobacteria is yet unclear (Fan et al., 2020), while other studies support the idea that mitochondria evolved from an ancestor related to Rickettsiales (Andersson et al., 1998; Wang and Wu, 2015). It is true that mitochondria have a bacterial origin and do share many proteins that mediate similar or even the same metabolic processes (Karlberg et al., 2000). Besides that, the use of antibiotics such as quinolones, aminoglycosides and poplar polysaccharide antibiotics can induce mitochondria dysfunction due to similarities in their structures with bacteria (Kalghatgi et al., 2013; Lleonart et al., 2017). For instance, that quinolones target mtDNA topoisomerases (Gootz et al., 1990) and bacterial gyrases (Wolfson and Hooper, 1985), aminoglycosides target both mitochondrial (Hutchin and Cortopassi, 1994) and bacterial ribosomes (Davis, 1987). Reversibly, mitochondrial-targeted antioxidants could also function as effective antibiotics (Nazarov et al., 2017). These studies suggested that mitochondria have a close relationship with bacteria, which indicates a possibility of information exchange between gut microbiota and mitochondria.

Intestinal epithelium and gastrointestinal nerves are the first sites of interactions between microbes and hosts (Figure 2). Moreover, many toxins produced by gut microbiota can lead to mitochondrial dysfunctions. For example, when the host was infected by pathogenic bacteria, mitochondria will be activated by lipopolysaccharides and other toxins released by the gut microbiota, inducing the accumulation of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS), which sequentially mediate intestinal inflammation (Mills et al., 2016). In addition, toxins secreted by certain species of Clostridium could inhibit the mitochondrial ATP-sensitive potassium channels, leading to mitochondrial membrane hyperpolarization, cell apoptosis, and intestinal epithelial barrier disruption (Matarrese et al., 2007; Berger et al., 2016; Crakes et al., 2019). The increased intestinal permeability enabled the translocation of damaging substances or pathogens into the intestinal epithelium and gastrointestinal nerves. Vagus nerve, an important link in the gut-brain axis, is able to sense microbial metabolites through its afferents, which transfers gut information to the central nervous system (Bonaz et al., 2018; Yu et al., 2020). Moreover, mitochondria are an important source of damaged cells release endogenous messengers (DAMPs), the release of these mitochondrial ROS have role of signaling in neuroinflammation and neurodegenerative diseases (Hsieh and Yang, 2013). DAMPs can also activate the innate immune system (Taanman, 1999), while innate immunity further reacts to different insults that may challenge the integrity of the central nervous system (CNS; Liu et al., 2014).

Figure 2. Intestinal microbiota or its metabolites can directly regulate brain function through HPA axis, vagus nerve, and immune pathway.

Experimental evidence has been showing that metabolites produced by gut microbes interact directly with brain mitochondria, providing new insights into the communication pathway from gut to brain. In specificity, intestinal infection caused by lipopolysaccharides from gram-negative bacteria could trigger mitochondrial antigen presentation (MitAP) in autoimmune CD8 + T cells, which could enter the brain to attack dopamine neurons and cause a sharp decrement in the density of dopaminergic axon expansion in the striatum, leading to movement disorders like Parkinson’s disease (PD) in mice (Matheoud et al., 2019). Effects of pathogenic bacteria on mitochondria can also include morphological and functional changes. Listeriolysin O (LLO) secreted by Listeria monocytogenes, which can cause CNS infection, can inserted into the plasma membrane, causing calcium influx and indirectly leading to mitochondrial fission (Stavru et al., 2011). Helicobacter pylori, an important pathogen that causes chronic gastritis in various areas of stomach and duodenum, could also cause nervous system inflammation and even promote the occurrence of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). However, the relationship between Helicobacter pylori infection and neurological inflammation or AD remains unclear. It has been reported that toxin VacA secreted by Helicobacter pylori can migrate across the blood-brain barrier (Suzuki et al., 2019), which could also be inserted in the mitochondrial inner membrane, causing calcium influx and thus indirectly leading to mitochondrial fission (Foo et al., 2010). Since it was proposed that altered balance in mitochondrial fission might be an important mechanism of neuronal dysfunction in the brain tissue of AD patients (Wang et al., 2009; Manczak and Reddy, 2012), it could provide novel insights into how Helicobacter pylori targets neural mitochondria and how mitochondrial and neuronal dysfunctions evolve. A recent study also showed that aberrant mitochondria functionality could be a key mediator for the effects of the intestinal microbiota on the progression of depression (Chen and Vitetta, 2020). These studies supported the role that mitochondria plays as an emerging target for bacteria-induced neurological diseases.

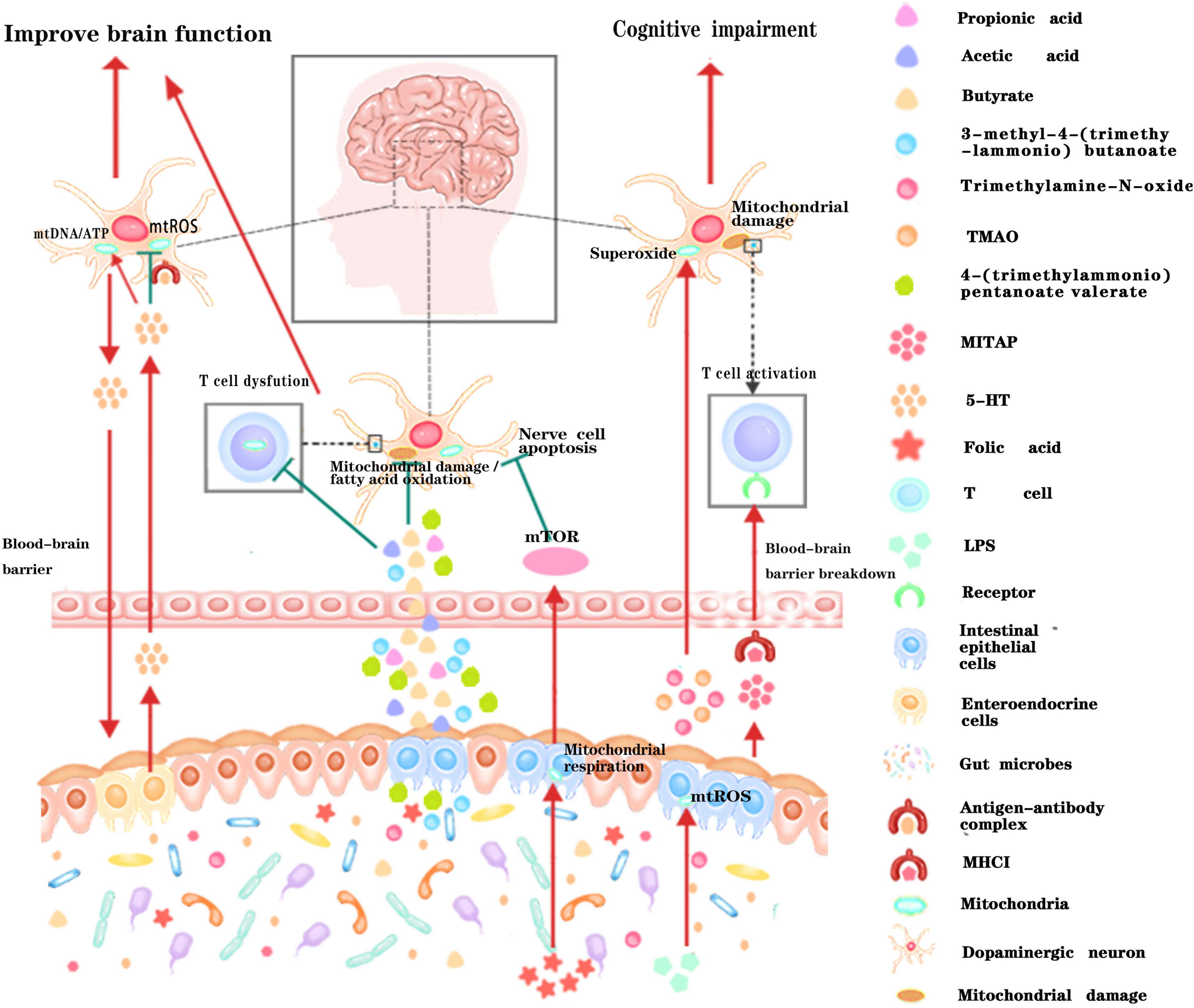

A large amount of evidence suggest that gut microbiota can also remotely regulate the mitochondrial function of brain tissue through the various metabolites they produced (Figure 3). Short-chain fatty acids (SCFA) generated by gut microbiota can cross the highly selective semipermeable blood-brain barrier (Luu and Visekruna, 2019; Melbye et al., 2019) and directly enter the mitochondria for further oxidative metabolism (Chen and Vitetta, 2020). In addition, supplementation of propionic acid (PA), could defer the progression of Multiple sclerosis (MS) and brain atrophy (Duscha et al., 2020). Since PA can improve mitochondrial function and morphology in competent regulatory T (Treg) cells, and can enter the brain directly, it is rationally speculated that the protective effect of PA on brain tissue may be achieved by improving neural mitochondrial function. Folate produced by gut flora (mainly Escherichia coli) could regulate mitochondrial respiration and play an important role in the early development of the nervous system by activating the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathway (Silva et al., 2017). Isoallolithocholic acid (IsoalloLCA), distinct derivatives of lithocholic acid, which is also closely related to nervous system diseases, can also induce the production of mitochondrial ROS (Hang et al., 2019). The gut microbiota metabolites 4-(trimethylammonio) pentanoate valerate and 3-methyl-4-(trimethylammonio) butanoate could enter the brain tissue and inhibit the oxidation of mitochondrial fatty acids so as to mediate gut-brain communication (Hulme et al., 2020). Another study found that trimethylamine-N-oxide can also increase mitochondrial damage and superoxide production in mice, thereby accelerating the aging of neurons in the hippocampus of mice, causing and exacerbating aging-related cognitive impairment (Li et al., 2018). Therefore, it is of great theoretical significance to clarify the underlying pathways that gut microbiota metabolites affect brain function by regulating mitochondrial bioactivities, and to reveal how gut microbiota regulate the neuronal functions through dietary metabolism. These studies may provide new drug targets for the ontological enteric treatment of encephalopathy.

Figure 3. Schematic illustration of the dialog between intestinal microbiota and neural mitochondria across the blood-brain barrier. Metabolites or active small molecules secreted by intestinal microbiota cross the blood-brain barrier and modulate mitochondrial functions through mTOR signaling pathway, ROS signaling pathway, immune pathway, or directly acting on neural mitochondria to influence brain functions. Red arrows indicate enhancement while the green T arrows indicate inhibition.

Another strategy of gut microbiota affecting the host’s nervous system is to regulate the host’s neurotransmitter levels, such as gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), serotonin (5-HT), and dopamine (DA). These neurotransmitters have been found to be closely in mitochondrial function. For example, GABA can pass through mitochondrial membrane, and regulate citric acid cycle reaction. The distribution mode of GABA is believed to play a critical role in regulating its cytoplasm levels; Conversely, increased mitochondrial activity can reduce GABAergic signaling, resulting in defective social behavior (Kanellopoulos et al., 2020). Recent studies have also shown that 5-HT could promote mitochondrial biogenesis, which is involved in reducing toxic ROS in neurons, protecting buffered neurons from damages caused by cellular stress (Fanibunda et al., 2019). Dopamine has been reported to be associated with mitochondrial dysfunction. Experimental evidence suggests that high dopamine concentrations induce striatal mitochondrial dysfunction through a decrease in mitochondrial respiratory control and loss of membrane potential (Czerniczyniec et al., 2010) and promotes mitochondrial complex I inhibition and leads to neuropsychiatric disorders (Ben-Shachar et al., 2004; Brenner-Lavie et al., 2008). These studies suggested that mitochondria also play an important role in gut microbiota- neurotransmitters-brain communication.

Reciprocally, mitochondria can also regulate the intestinal microbiota. Studies have shown that mitochondria play an important role in the innate immune response to pathogen infection (Lobet et al., 2015). In addition, mitochondria dysfunction also involves in the regulation of the gut epithelial barrier, allowing transepithelial flux of Escherichia coli (Wang et al., 2014). In addition, mitochondrial variants can affect the diversity and composition of intestinal microbiota (Evaldson et al., 1980; Ma et al., 2014; Yardeni et al., 2019). Moreover, mitochondrial chaperone HSP-60 in the neurons regulates anti-bacterial immunity via p38 MAP kinase signaling (Jeong et al., 2017). Clinical studies have shown that a large proportion of patients with neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD; Haran et al., 2019; Sochocka et al., 2019), Parkinson’s disease (PD; Brudek, 2019; Dumitrescu et al., 2021), and Huntington’s disease (HD; Du et al., 2020; Wasser et al., 2020), often suffer from intestinal inflammation simultaneously. A recent report found that artificial expression of HD-causing protein PolyQ40 in nerve cells of Caenorhabditis elegans can induce mitochondrial unfolded protein response in the intestine (Zhang et al., 2018). These results further indicate that mitochondria play an important role in signal transmission between the brain and the gut. Another study found that 5-HT can regulate the colonization of Turicibacter sanguinis in the intestine, and Turicibacter sanguinis can affect the expression of multiple pathways including lipid and cholesterol metabolism in intestinal (Fung et al., 2019). Combined with the evidence that 5-HT can promote mitochondrial biogenesis and the level of ROS produced by host mitochondria can regulate the diversity of gut flora (Fanibunda et al., 2019), we can deduce that neuron secreted 5-HT regulate the gut flora by regulating the function of intestinal mitochondria. These results suggest that mitochondria mediate two-way communication between gut and brain.

The understanding of intestinal system has been revolutionized over the past decades, especially in regarding to its physiological and pathological interconnection with brain function. The crosstalk between gut microbiota and central nervous system, which is also known as the microbiota-gut-brain axis have been well elucidated from numerous studies. Numbers of evidence has confirmed that mitochondria can be regulated by the composition of gut microbiota, and mitochondria are also closely related to the physiological and pathological state of the nervous system. In addition, although there are few studies on how gut microbiota directly regulate the physiological and pathological functions of the brain through the mitochondrial pathway, or how the nervous system regulates the composition of gut microbiota through the mitochondrial pathway, the evidence had been gradually reported in recent years. This perspective proposed a hypothetical model about cross-talk between the intestinal microbiome and the neural mitochondria based on the previously known fact that the mitochondria and the bacteria have the evolutionary homology. Symbiont and pathobiont bacteria have the influence to control the neuronal mitochondrial activity. We highlighted the new role of mitochondria in dialog with gut microbiota across the blood-brain barrier, which is one of the important ways of communicating between the brain and gut (Figure 3). The new perspective not only expands our understanding of the brain-gut interaction mechanism, but also provides a new treatment strategy targeting the gut microbiota-mitochondria-brain communication which has the potential to treat a variety of nervous system diseases or digestive system diseases, and may also have a profound impact on future medical treatment.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

YZ performed the statistical analysis. ZZ, LW, YL, QZ, and YS wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81902040 and 81701390), the Jiangsu Province Postgraduate Research and Practice Innovation Project (KYCX20-2464 and KYCX21-2642), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20170250), the Xuzhou Science and Technology Innovation Project (KC19057). Fusion Innovation Project of Xuzhou Medical University (XYRHCX). LW would like to thank the financial support of National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 31900022 and 32171281), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (No. BK20180997), the Young Science and Technology Innovation Team of Xuzhou Medical University (No. TD202001) and the Jiang-Su Qing-Lan Project (2020).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Thanks are due to Prof. Shi Huang for fruitful discussions.

Andersson, S. G., Zomorodipour, A., Andersson, J. O., Sicheritz-Ponten, T., Alsmark, U. C., Podowski, R. M., et al. (1998). The genome sequence of Rickettsia prowazekii and the origin of mitochondria. Nature 396, 133–140. doi: 10.1038/24094

Ben-Shachar, D., Zuk, R., Gazawi, H., and Ljubuncic, P. (2004). Dopamine toxicity involves mitochondrial complex i inhibition: implications to dopamine-related neuropsychiatric disorders. Biochem. Pharmacol. 67, 1965–1974. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.02.015

Berger, E., Rath, E., Yuan, D., Waldschmitt, N., Khaloian, S., Allgauer, M., et al. (2016). Mitochondrial function controls intestinal epithelial stemness and proliferation. Nat. Commun. 7:13171. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13171

Bonaz, B., Bazin, T., and Pellissier, S. (2018). The vagus nerve at the interface of the microbiota-gut-brain axis. Front. Neurosci. 12:49. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2018.00049

Brenner-Lavie, H., Klein, E., Zuk, R., Gazawi, H., Ljubuncic, P., and Ben-Shachar, D. (2008). Dopamine modulates mitochondrial function in viable SH-SY5Y cells possibly via its interaction with complex I: relevance to dopamine pathology in schizophrenia. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1777, 173–185. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2007.10.006

Brudek, T. (2019). Inflammatory bowel diseases and Parkinson’s disease. J. Parkinsons Dis. 9, S331–S344.

Chen, J., and Vitetta, L. (2020). Mitochondria could be a potential key mediator linking the intestinal microbiota to depression. J. Cell. Biochem. 121, 17–24. doi: 10.1002/jcb.29311

Crakes, K. R., Santos Rocha, C., Grishina, I., Hirao, L. A., Napoli, E., Gaulke, C. A., et al. (2019). PPARalpha-targeted mitochondrial bioenergetics mediate repair of intestinal barriers at the host-microbe intersection during SIV infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 3, 24819–24829. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1908977116

Czerniczyniec, A., Bustamante, J., and Lores-Arnaiz, S. (2010). Dopamine modifies oxygen consumption and mitochondrial membrane potential in striatal mitochondria. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 341, 251–257. doi: 10.1007/s11010-010-0456-z

Davis, B. D. (1987). Mechanism of bactericidal action of aminoglycosides. Microbiol. Rev. 51, 341–350.

Du, G., Dong, W., Yang, Q., Yu, X., Ma, J., Gu, W., et al. (2020). Altered gut microbiota related to inflammatory responses in patients with huntington’s disease. Front. Immunol. 11:603594. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.603594

Dumitrescu, L., Marta, D., Danau, A., Lefter, A., Tulba, D., Cozma, L., et al. (2021). Serum and fecal markers of intestinal inflammation and intestinal barrier permeability are elevated in Parkinson’s disease. Front. Neurosci. 15:689723. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2021.689723

Duscha, A., Gisevius, B., Hirschberg, S., Yissachar, N., Stangl, G. I., Eilers, E., et al. (2020). Propionic acid shapes the multiple sclerosis disease course by an immunomodulatory mechanism. Cell 180, 1067–1080.e16. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.035

Evaldson, G., Carlstrom, G., Lagrelius, A., Malmborg, A. S., and Nord, C. E. (1980). Microbiological findings in pregnant women with premature rupture of the membranes. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 168, 283–297. doi: 10.1007/BF02121812

Fan, L., Wu, D., Goremykin, V., Xiao, J., Xu, Y., Garg, S., et al. (2020). Phylogenetic analyses with systematic taxon sampling show that mitochondria branch within Alphaproteobacteria. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 4, 1213–1219. doi: 10.1038/s41559-020-1239-x

Fanibunda, S. E., Deb, S., Maniyadath, B., Tiwari, P., Ghai, U., Gupta, S., et al. (2019). Serotonin regulates mitochondrial biogenesis and function in rodent cortical neurons via the 5-HT2A receptor and SIRT1-PGC-1alpha axis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116:11028. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1821332116

Foo, J. H., Culvenor, J. G., Ferrero, R. L., Kwok, T., Lithgow, T., and Gabriel, K. (2010). Both the p33 and p55 subunits of the Helicobacter pylori VacA toxin are targeted to mammalian mitochondria. J. Mol. Biol. 401, 792–798. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.06.065

Franco-Obregon, A., and Gilbert, J. A. (2017). The Microbiome-mitochondrion connection: common ancestries, common mechanisms, common goals. mSystems 2:e00018-17. doi: 10.1128/mSystems.00018-17

Fulling, C., Dinan, T. G., and Cryan, J. F. (2019). Gut microbe to brain signaling: what happens in vagus. Neuron 101, 998–1002. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.02.008

Fung, T. C. (2020). The microbiota-immune axis as a central mediator of gut-brain communication. Neurobiol. Dis. 136:104714. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2019.104714

Fung, T. C., Vuong, H. E., Luna, C. D. G., Pronovost, G. N., Aleksandrova, A. A., Riley, N. G., et al. (2019). Intestinal serotonin and fluoxetine exposure modulate bacterial colonization in the gut. Nat. Microbiol. 4, 2064–2073. doi: 10.1038/s41564-019-0540-4

Gootz, T. D., Barrett, J. F., and Sutcliffe, J. A. (1990). Inhibitory effects of quinolone antibacterial agents on eucaryotic topoisomerases and related test systems. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 34, 8–12. doi: 10.1128/AAC.34.1.8

Hang, S., Paik, D., Yao, L., Kim, E., Trinath, J., Lu, J., et al. (2019). Bile acid metabolites control TH17 and Treg cell differentiation. Nature 576, 143–148.

Haran, J. P., Bhattarai, S. K., Foley, S. E., Dutta, P., Ward, D. V., Bucci, V., et al. (2019). Alzheimer’s disease microbiome is associated with dysregulation of the anti-inflammatory P-glycoprotein pathway. mBio 10:e00632-19. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00632-19

Hsieh, H. L., and Yang, C. M. (2013). Role of redox signaling in neuroinflammation and neurodegenerative diseases. Biomed. Res. Int. 2013:484613. doi: 10.1155/2013/484613

Hulme, H., Meikle, L. M., Strittmatter, N., van der Hooft, J. J. J., Swales, J., Bragg, R. A., et al. (2020). Microbiome-derived carnitine mimics as previously unknown mediators of gut-brain axis communication. Sci. Adv. 6:eaax6328. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aax6328

Hutchin, T., and Cortopassi, G. (1994). Proposed molecular and cellular mechanism for aminoglycoside ototoxicity. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 38, 2517–2520. doi: 10.1128/AAC.38.11.2517

Iwata, R., Casimir, P., and Vanderhaeghen, P. (2020). Mitochondrial dynamics in postmitotic cells regulate neurogenesis. Science 369, 858–862. doi: 10.1126/science.aba9760

Jeong, D. E., Lee, D., Hwang, S. Y., Lee, Y., Lee, J. E., Seo, M., et al. (2017). Mitochondrial chaperone HSP-60 regulates anti-bacterial immunity via p38 MAP kinase signaling. EMBO J. 36, 1046–1065. doi: 10.15252/embj.201694781

Kalghatgi, S., Spina, C. S., Costello, J. C., Liesa, M., Morones-Ramirez, J. R., Slomovic, S., et al. (2013). Bactericidal antibiotics induce mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative damage in Mammalian cells. Sci. Transl. Med. 5:192ra185. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3006055

Kanellopoulos, A. K., Mariano, V., Spinazzi, M., Woo, Y. J., McLean, C., Pech, U., et al. (2020). Aralar sequesters GABA into hyperactive mitochondria, causing social behavior deficits. Cell 180, 1178–1197.e20 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.044

Karbowski, J. (2007). Global and regional brain metabolic scaling and its functional consequences. BMC Biol. 5:18. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-5-18

Karlberg, O., Canback, B., Kurland, C. G., and Andersson, S. G. (2000). The dual origin of the yeast mitochondrial proteome. Yeast 17, 170–187. doi: 10.1002/1097-0061(20000930)17:3<170::AID-YEA25>3.0.CO;2-V

Khacho, M., Clark, A., Svoboda, D. S., Azzi, J., MacLaurin, J. G., Meghaizel, C., et al. (2016). Mitochondrial dynamics impacts stem cell identity and fate decisions by regulating a nuclear transcriptional program. Cell Stem Cell. 19, 232–247. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.04.015

Li, D., Ke, Y., Zhan, R., Liu, C., Zhao, M., Zeng, A., et al. (2018). Trimethylamine-N-oxide promotes brain aging and cognitive impairment in mice. Aging Cell 17:e12768. doi: 10.1111/acel.12768

Liu, H. Y., Chen, C. Y., and Hsueh, Y. P. (2014). Innate immune responses regulate morphogenesis and degeneration: roles of Toll-like receptors and Sarm1 in neurons. Neurosci. Bull. 30, 645–654. doi: 10.1007/s12264-014-1445-5

Lleonart, M. E., Grodzicki, R., Graifer, D. M., and Lyakhovich, A. (2017). Mitochondrial dysfunction and potential anticancer therapy. Med. Res. Rev. 37, 1275–1298. doi: 10.1002/med.21459

Lobet, E., Letesson, J. J., and Arnould, T. (2015). Mitochondria: a target for bacteria. Biochem. Pharmacol. 94, 173–185. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2015.02.007

Luu, M., and Visekruna, A. (2019). Short-chain fatty acids: bacterial messengers modulating the immunometabolism of T cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 49, 842–848. doi: 10.1002/eji.201848009

Ma, J., Coarfa, C., Qin, X., Bonnen, P. E., Milosavljevic, A., Versalovic, J., et al. (2014). mtDNA haplogroup and single nucleotide polymorphisms structure human microbiome communities. BMC Genomics 15:257. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-257

Manczak, M., and Reddy, P. H. (2012). Abnormal interaction between the mitochondrial fission protein Drp1 and hyperphosphorylated tau in Alzheimer’s disease neurons: implications for mitochondrial dysfunction and neuronal damage. Hum. Mol. Genet. 21, 2538–2547. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds072

Matarrese, P., Falzano, L., Fabbri, A., Gambardella, L., Frank, C., Geny, B., et al. (2007). Clostridium difficile toxin B causes apoptosis in epithelial cells by thrilling mitochondria. Involvement of ATP-sensitive mitochondrial potassium channels. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 9029–9041. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607614200

Matheoud, D., Cannon, T., Voisin, A., Penttinen, A. M., Ramet, L., Fahmy, A. M., et al. (2019). Intestinal infection triggers Parkinson’s disease-like symptoms in Pink1(-/-) mice. Nature 571, 565–569. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1405-y

McNeilly, A. D., Macfarlane, D. P., O’Flaherty, E., Livingstone, D. E., Mitic, T., McConnell, K. M., et al. (2010). Bile acids modulate glucocorticoid metabolism and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in obstructive jaundice. J. Hepatol. 52, 705–711. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.10.037

Melbye, P., Olsson, A., Hansen, T. H., Sondergaard, H. B., and Bang Oturai, A. (2019). Short-chain fatty acids and gut microbiota in multiple sclerosis. Acta Neurol. Scand. 139, 208–219. doi: 10.1111/ane.13045

Mills, E. L., Kelly, B., Logan, A., Costa, A. S. H., Varma, M., Bryant, C. E., et al. (2016). Succinate dehydrogenase supports metabolic repurposing of mitochondria to drive inflammatory macrophages. Cell 167, 457–470.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.08.064

Moeller, A. H., Caro-Quintero, A., Mjungu, D., Georgiev, A. V., Lonsdorf, E. V., Muller, M. N., et al. (2016). Cospeciation of gut microbiota with hominids. Science 353, 380–382. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf3951

Morais, L. H., and Schreiber, HLt, and Mazmanian, S. K. (2020). The gut microbiota-brain axis in behaviour and brain disorders. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 19, 241–255 doi: 10.1038/s41579-020-00460-0

Nazarov, P. A., Osterman, I. A., Tokarchuk, A. V., Karakozova, M. V., Korshunova, G. A., Lyamzaev, K. G., et al. (2017). Mitochondria-targeted antioxidants as highly effective antibiotics. Sci. Rep. 7:1394. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-00802-8

Nguyen, T. T., Oh, S. S., Weaver, D., Lewandowska, A., Maxfield, D., Schuler, M. H., et al. (2014). Loss of Miro1-directed mitochondrial movement results in a novel murine model for neuron disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, E3631–E3640. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1402449111

Silva, E., Rosario, F. J., Powell, T. L., and Jansson, T. (2017). Mechanistic target of rapamycin is a novel molecular mechanism linking folate availability and cell function. J. Nutr. 147, 1237–1242. doi: 10.3945/jn.117.248823

Sochocka, M., Donskow-Lysoniewska, K., Diniz, B. S., Kurpas, D., Brzozowska, E., and Leszek, J. (2019). The gut microbiome alterations and inflammation-driven pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease-a critical review. Mol. Neurobiol. 56, 1841–1851. doi: 10.1007/s12035-018-1188-4

Stavru, F., Bouillaud, F., Sartori, A., Ricquier, D., and Cossart, P. (2011). Listeria monocytogenes transiently alters mitochondrial dynamics during infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 3612–3617. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100126108

Suzuki, H., Ataka, K., Asakawa, A., Cheng, K. C., Ushikai, M., Iwai, H., et al. (2019). Helicobacter pylori vacuolating cytotoxin A causes anorexia and anxiety via hypothalamic urocortin 1 in mice. Sci. Rep. 9:6011. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-42163-4

Taanman, J. W. (1999). The mitochondrial genome: structure, transcription, translation and replication. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1410, 103–123. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(98)00161-3

van de Guchte, M., Blottiere, H. M., and Dore, J. (2018). Humans as holobionts: implications for prevention and therapy. Microbiome 6:81. doi: 10.1186/s40168-018-0466-8

Wang, A., Keita, A. V., Phan, V., McKay, C. M., Schoultz, I., Lee, J., et al. (2014). Targeting mitochondria-derived reactive oxygen species to reduce epithelial barrier dysfunction and colitis. Am. J. Pathol. 184, 2516–2527. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2014.05.019

Wang, X., Su, B., Lee, H. G., Li, X., Perry, G., Smith, M. A., et al. (2009). Impaired balance of mitochondrial fission and fusion in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurosci. 29, 9090–9103. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1357-09.2009

Wang, Z., and Wu, M. (2015). An integrated phylogenomic approach toward pinpointing the origin of mitochondria. Sci. Rep. 5:7949. doi: 10.1038/srep07949

Wasser, C. I., Mercieca, E. C., Kong, G., Hannan, A. J., McKeown, S. J., Glikmann-Johnston, Y., et al. (2020). Gut dysbiosis in Huntington’s disease: associations among gut microbiota, cognitive performance and clinical outcomes. Brain Commun. 2:fcaa110. doi: 10.1093/braincomms/fcaa110

Wolfson, J. S., and Hooper, D. C. (1985). The fluoroquinolones: structures, mechanisms of action and resistance, and spectra of activity in vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 28, 581–586. doi: 10.1128/AAC.28.4.581

Yardeni, T., Tanes, C. E., Bittinger, K., Mattei, L. M., Schaefer, P. M., Singh, L. N., et al. (2019). Host mitochondria influence gut microbiome diversity: a role for ROS. Sci. Signal. 12:eaaw3159 doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aaw3159

Yu, C. D., Xu, Q. J., and Chang, R. B. (2020). Vagal sensory neurons and gut-brain signaling. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 62, 133–140. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2020.03.006

Keywords: intestinal microbiome, mitochondria, microbiota-gut-brain axis, brain, gut

Citation: Zhu Y, Li Y, Zhang Q, Song Y, Wang L and Zhu Z (2022) Interactions Between Intestinal Microbiota and Neural Mitochondria: A New Perspective on Communicating Pathway From Gut to Brain. Front. Microbiol. 13:798917. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.798917

Received: 20 October 2021; Accepted: 03 February 2022;

Published: 24 February 2022.

Edited by:

George Tsiamis, University of Patras, GreeceReviewed by:

Xin Zhang, Ningbo University, ChinaCopyright © 2022 Zhu, Li, Zhang, Song, Wang and Zhu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zuobin Zhu, emh1enVvYmluQHh6aG11LmVkdS5jbg==; Liang Wang, aGVhbHRoc2NpZW5jZUBmb3htYWlsLmNvbQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.