- 1Department of Endodontics, School of Dentistry, Bushehr University of Medical Sciences, Bushehr, Iran

- 2The Persian Gulf Marine Biotechnology Research Center, The Persian Gulf Biomedical Sciences Research Institute, Bushehr University of Medical Sciences, Bushehr, Iran

- 3Department of Stem Cells and Developmental Biology, Cell Science Research Center, Royan Institute for Stem Cell Biology and Technology, ACECR, Tehran, Iran

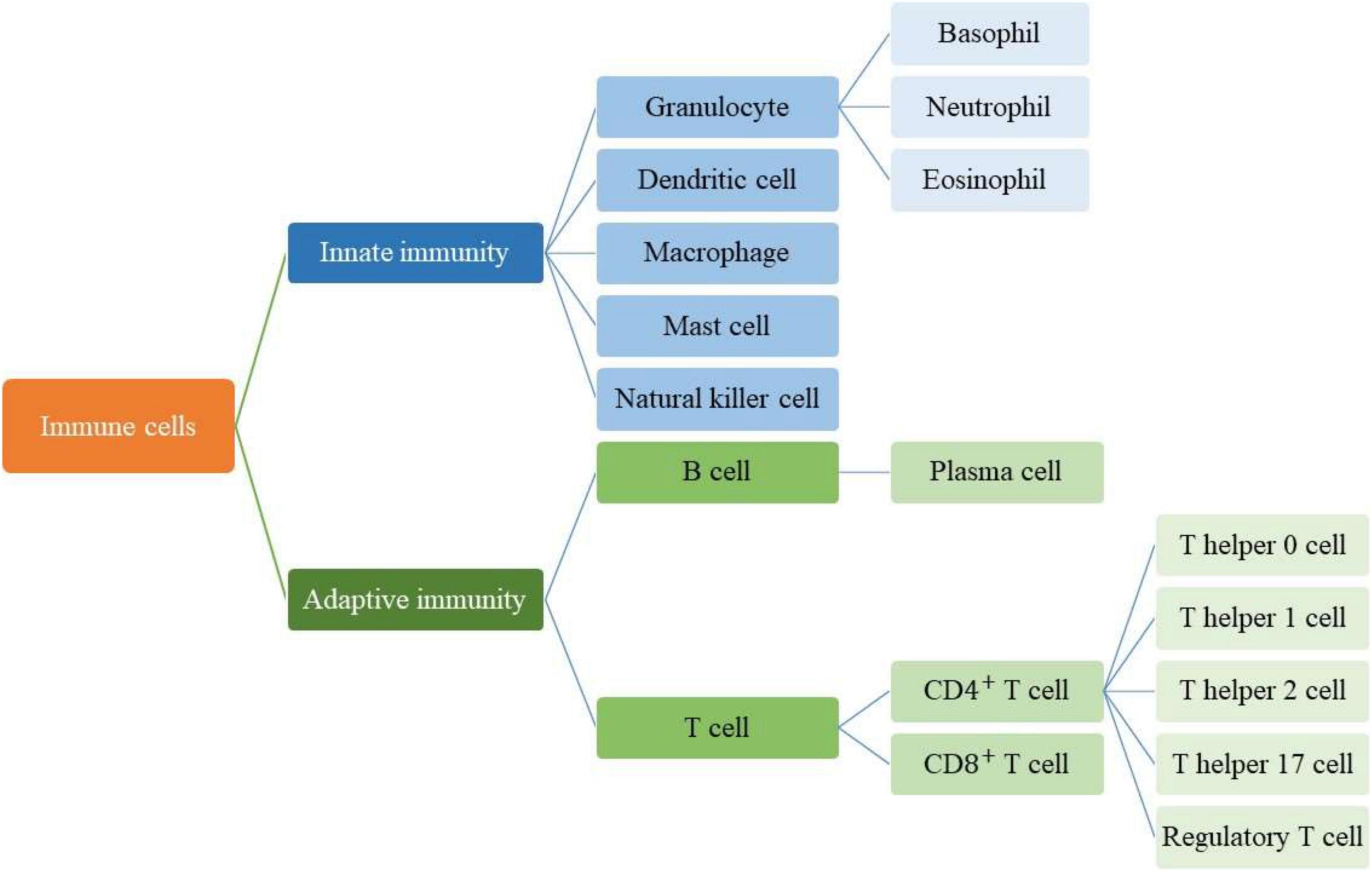

The oral cavity as the second most various microbial community in the body contains a broad spectrum of microorganisms which are known as the oral microbiome. The oral microbiome includes different types of microbes such as bacteria, fungi, viruses, and protozoa. Numerous factors can affect the equilibrium of the oral microbiome community which can eventually lead to orodental infectious diseases. Periodontitis, dental caries, oral leukoplakia, oral squamous cell carcinoma are some multifactorial infectious diseases in the oral cavity. In defending against infection, the immune system has an essential role. Depending on the speed and specificity of the reaction, immunity is divided into two different types which are named the innate and the adaptive responses but also there is much interaction between them. In these responses, different types of immune cells are present and recent evidence demonstrates that these cell types both within the innate and adaptive immune systems are capable of secreting some extracellular vesicles named exosomes which are involved in the response to infection. Exosomes are 30–150 nm lipid bilayer vesicles that consist of variant molecules, including proteins, lipids, and genetic materials and they have been associated with cell-to-cell communications. However, some kinds of exosomes can be effective on the pathogenicity of various microorganisms and promoting infections, and some other ones have antimicrobial and anti-infective functions in microbial diseases. These discrepancies in performance are due to the origin of the exosome. Exosomes can modulate the innate and specific immune responses of host cells by participating in antigen presentation for activation of immune cells and stimulating the release of inflammatory factors and the expression of immune molecules. Also, mesenchymal stromal/stem cells (MSCs)-derived exosomes participate in immunomodulation by different mechanisms. Ease of expansion and immunotherapeutic capabilities of MSCs, develop their applications in hundreds of clinical trials. Recently, it has been shown that cell-free therapies, like exosome therapies, by having more advantages than previous treatment methods are emerging as a promising strategy for the treatment of several diseases, in particular inflammatory conditions. In orodental infectious disease, exosomes can also play an important role by modulating immunoinflammatory responses. Therefore, MSCs-derived exosomes may have potential therapeutic effects to be a choice for controlling and treatment of orodental infectious diseases.

Introduction

The oral cavity is the second most diverse microbial community in the human body after the gut (Caselli et al., 2020). Numerous microorganisms including fungi, viruses, protozoa, and over 700 species of bacteria in this community are called “microbiome” (Deo and Deshmukh, 2019). The microbiome is a term that was coined by Joshua Lederberg, a Nobel Prize laureate, to explain the ecological community of symbiotic, commensal, and pathogenic microorganisms that share human body space (Kilian et al., 2016). Orodental infections are caused by changes in the balance of microbial populations or the dynamic relationship between them and the oral cavity (Cho and Blaser, 2012; Marsh et al., 2015). In addition, the oral cavity is exposed to external environmental microorganisms that can cause oral diseases (Gerba, 2015).

The host immune system plays an important role in defending against pathogens (Dunkelberger and Song, 2010). At first, It fights against pathogens through innate immunity and then through adaptive immunity (Cerny and Striz, 2019). Although the innate immune system response is general, non-specific, and does not directly target a single pathogen, it provides a defense barrier against all infectious agents (Aderem and Ulevitch, 2000). The skin and mucosal membranes act as a mechanical barrier against pathogens, also epithelial cells contain peptides that have antimicrobial properties (Ganz, 2003; Oppenheim et al., 2003). If the pathogens can get past the primary defense, the second line of defense becomes active (Frank, 2000). In the infected area, an inflammatory response begins due to stimulation of high blood pressure, the blood vessels dilate, and white blood cells leave the veins during diapause to fight the pathogen (Chen et al., 2018). The vessels diameter increase, because of the secretion of “histamine” from mast cells. Mast cells are a type of white blood cell and phagocytes that draw in pathogens and kill them. During the inflammatory response, the infected area becomes red, swollen, and painful (Janeway et al., 2001b; Csaba et al., 2003) and, the immune system may release substances that raise the body temperature and cause fever. An increase in temperature can decelerate the growth of pathogens and the immune system fights against infectious agents more quickly (Evans et al., 2015). Some phagocytic cells detect pathogenic cells and other kill cells in the body and digest them (Bain, 2017). In the human body, some proteins are normally inactive and activated in infection conditions. They create pores in the membrane of pathogenic cells and destroy them. These proteins are unable to distinguish different pathogens from each other and attack all pathogens non-specifically (Janeway et al., 2001a).

Acquired or specific immunity is activated when a pathogen can cross the innate or non-specific immune mechanism (McDade et al., 2016). The cells of the body have signs that the immune system distinguishes them from other foreign cells (Rich and Chaplin, 2019). When the immune system encounters cells that do not have these signs, it recognizes them as aliens and attacks them through specific or acquired mechanisms, using lymphocytes and producing antibodies (Elgert, 2009). This mechanism develops during the growth of the human body. In this way, with the development of the human body and exposure to pathogens and various vaccinations, a library of antibodies from the cells of the immune system related to various pathogens is created in the body. This process is sometimes called “Immunological Memory” because immune cells remember their former enemies (Crotty and Ahmed, 2004). The acquired mechanism produces antibodies to protect the body against foreign agents, for example, if previous pathogens attack the body, it will produce antibodies more quickly and eliminate the infection (Jerne, 1973). Acquired immunity is caused by the presence of antigens. Antigens are usually located on the surface of pathogen cells, and each pathogen has its antigen (Lamm, 1997). The immune system responds to antigens by certain cells or by producing antibodies (Figure 1). Antibodies attack antigens and produce a signal that attracts phagocytes or other killer cells (Davies and Cohen, 1996). In the immune system, cells like mast cells (Raposo et al., 1997), epithelial cells (van Niel et al., 2001; Lin et al., 2005), antigen-presenting cells (Zitvogel et al., 1998), T lymphocytes (Anel et al., 2019), B lymphocytes (Kato et al., 2020), neutrophils (Vargas et al., 2016), and macrophage (Singhto et al., 2018) release small extracellular vesicles (EVs) which called “exosomes.”

The Role of Exosomes in Microbial Infections

EVs are made and secreted in normal and diseased states by most types of cells and have an essential role in intercellular communication and facilitate the immunity process They contain a wide range of lipid-bound nanoparticles that vary in size (Yanez-Mo et al., 2015; Maas et al., 2017; Herrmann et al., 2021). There is no certain agreement on markers or specific naming for EV subtypes, and EVs are usually classified according to their biogenesis pathway or their physical properties used for isolation (Théry et al., 2018). In fact, differences in size help to separate different types of EVs. Microvesicles, exosomes, and apoptotic bodies are the three main subtypes of EVs which are distinguished by their biogenesis, size, content, release pathways, and function (Figure 2; Karpman et al., 2017; Doyle and Wang, 2019; Ståhl et al., 2019).

In the late 1960s, for the first time, Bonucci (1967) and Anderson (1969) described small, secreted vesicles as small, 100-nm-diameter vesicles secreted by chondrocytes. A special subset of small EVs, between 30 and 150 nm in diameter, are known as exosomes that appear through endosomal biogenesis pathways (Willms et al., 2018; Tschuschke et al., 2020). A wide range of cell types can secrete exosomes, and the size of exosomes can vary even for exosomes secreted from a single cell line (Zhang et al., 2019). Exosomes consist of approximately 4,400 proteins, 194 lipids, 1,639 mRNAs, and 764 miRNAs and as secretory vesicles, the possibility of their physiological function has been defined (Mathivanan et al., 2012; Kim et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2019; O’Brien et al., 2020). They can regulate the immune system and also interfere with biological processes. Pathogenic infections alter the number of exosomes, their contents, and membrane structure (Li et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2018).

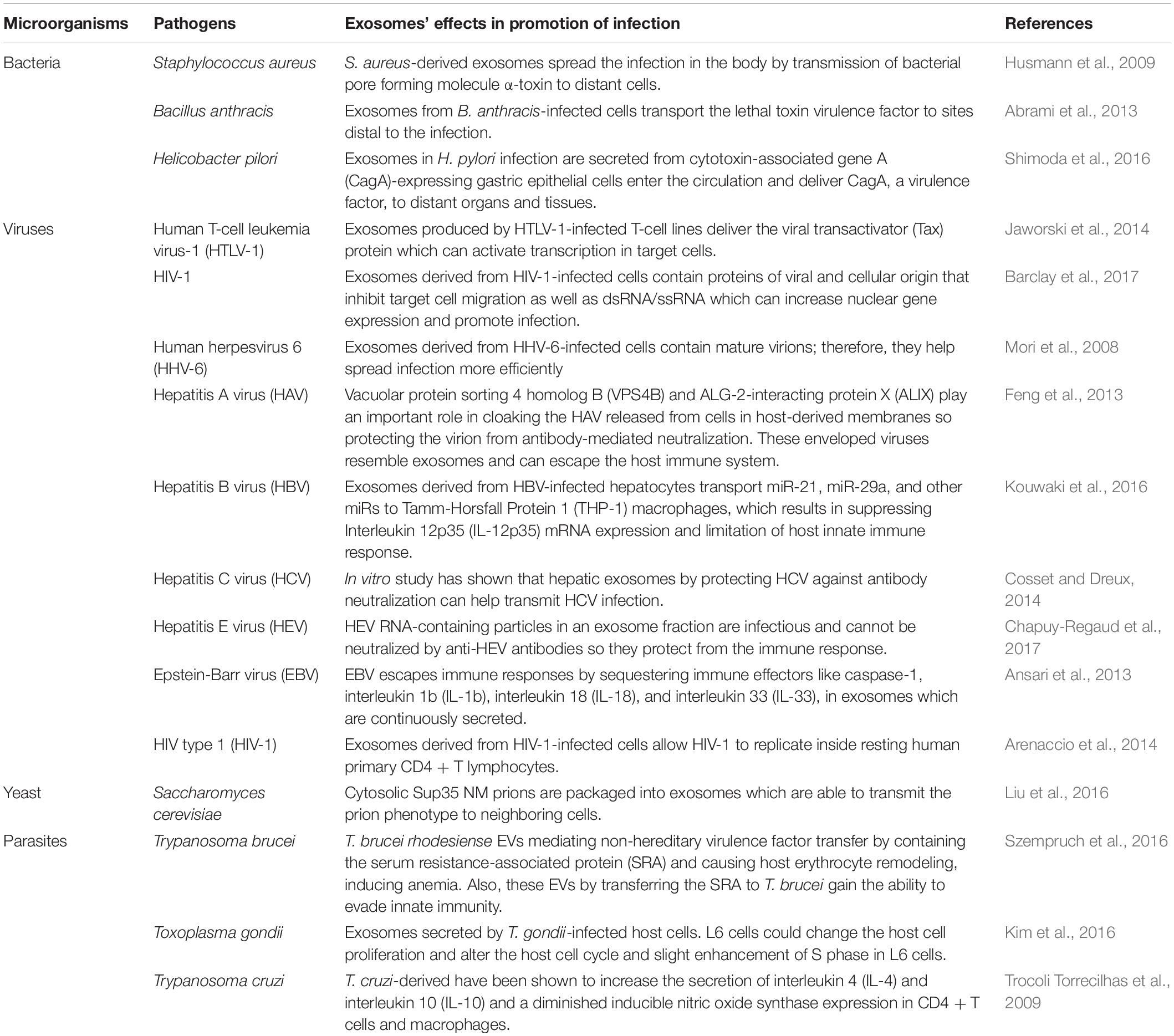

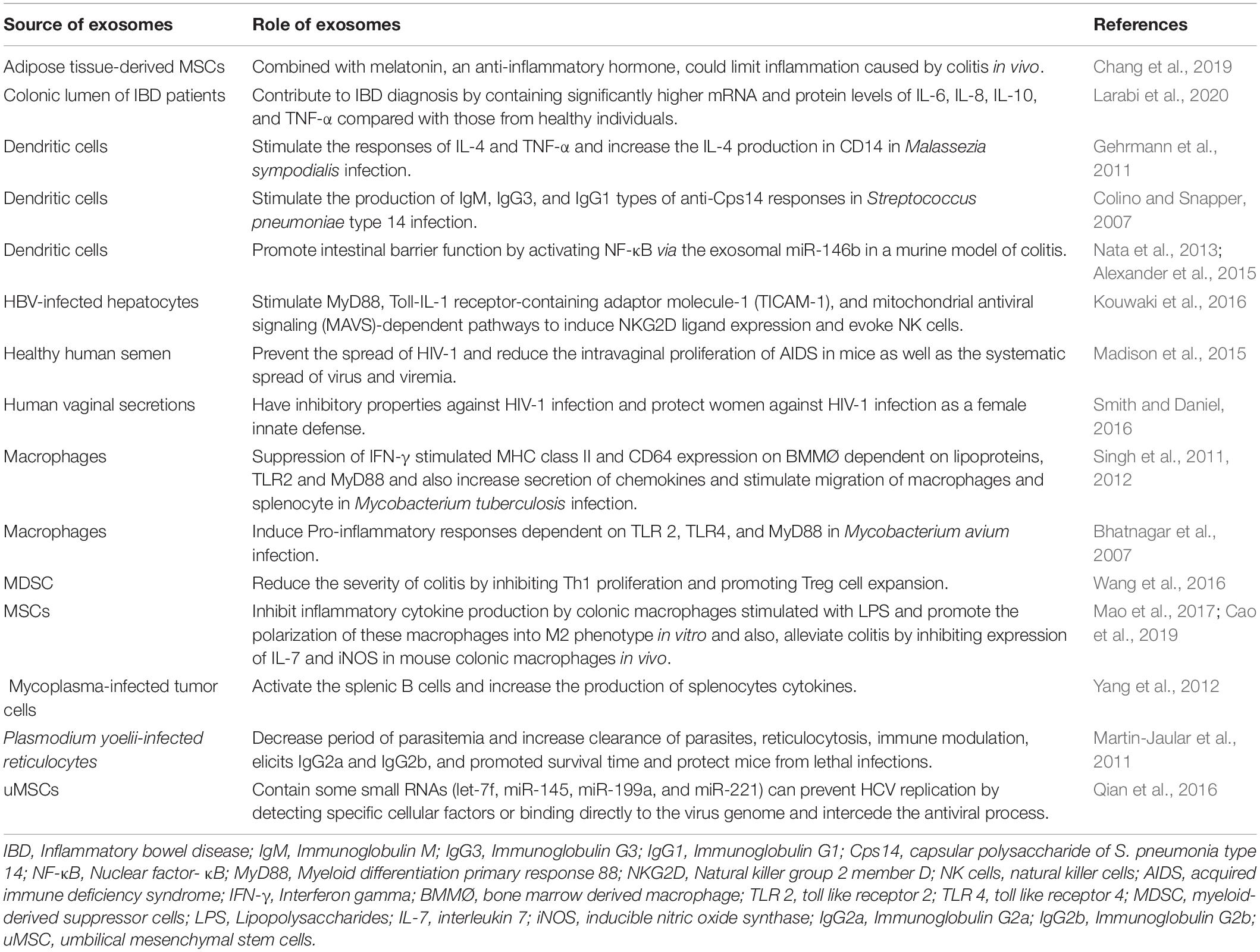

Infectious diseases like lower respiratory infections, malaria, diarrhea, tuberculosis (TB), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, and malaria are major reasons for morbidity and mortality worldwide and their treatment is challenging (Murray et al., 2014; Kirtane et al., 2021). Exosomes can interfere with the processes of infectious diseases. On the one hand, they can contribute to the pathogenesis of microorganisms, be effective in the progression of infection, and can fight against pathogens and infections. This functional variation of exosomes depends on the source of cells and their contents. To confirm this, Tables 1, 2 provide examples of the role of exosomes in infectious diseases. Briefly, Table 1 provides examples of the effects of exosomes on the pathogenicity of various microorganisms so that they cause and promote infections, and Table 2 lists several antimicrobial and anti-infective functions of exosomes in microbial diseases.

Orodental Infectious Disease

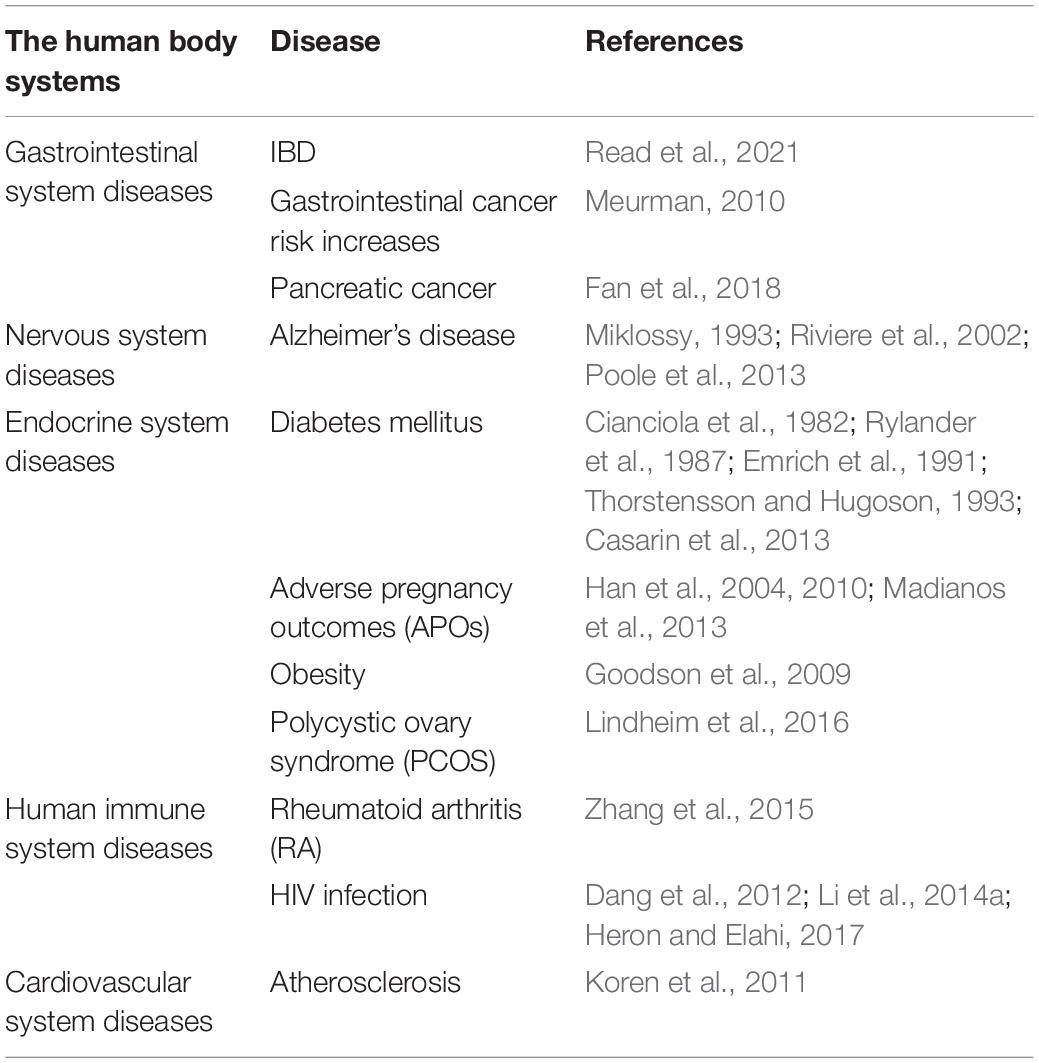

Orodental infectious diseases are caused by both pathogenic microorganisms and the loss of balance in the ecological community of symbiotic microorganisms in the oral cavity. Oral microbial diseases include a wide range of different diseases such as periodontitis and caries. If proper measures are not taken to control and treat mouth-infectious diseases, it can lead to whole-body systemic diseases (Table 3).

Periodontitis

The periodontium contains the supporting tissues around the structure of the teeth, such as the gingiva, cementum, junctional epithelium, periodontal ligament, and alveolar bone (Taba et al., 2005). Periodontal diseases are a result of periodontal structure destruction (Nanci and Bosshardt, 2006). The prevalence of periodontal disease is very high and more than 90% of adults worldwide suffer from it (Pihlstrom et al., 2005). There are two main categories of periodontal disease: gingivitis and periodontitis (Dorfer et al., 2004). Gingivitis is a milder form of periodontitis and is limited to gum tissue, but periodontitis occurs when the inflammation spreads to deeper tissues and causes loss of supporting connective tissue and alveolar bone (Kononen et al., 2019). The structure and texture of the periodontium can provide a suitable environment for the growth of various microorganisms (Cobb and Killoy, 1990). Microorganisms such as Porphyromonas gingivalis, Tannerella forsythensis, and Treponema denticola play an important role in the development of periodontal disease (Mineoka et al., 2008). T. forsythensis, T. denticola, and Treponema lecithinolyticum can be present in all phases of periodontal disease (Scapoli et al., 2015). Porphyromonas endodontalis and p. gingivalis are more specifically associated with periodontitis and Capnocytophaga ochracea and Campylobacter rectus associated with gingivitis (Scapoli et al., 2015).

Dental Caries

Tooth decay is the most common chronic infectious disease which deals with the chronic and progressive destruction of hard tooth tissue (Ozdemir, 2013; Rathee and Sapra, 2020). In this disease, the hard tooth tissue (enamel and dentin) loses calcium and phosphorus minerals due to acid secretion from cariogenic bacteria (mainly Streptococcus mutans) (Moynihan and Petersen, 2004; Selwitz et al., 2007; Krzysciak et al., 2014). There are various causes for caries, but in general, the four main factors of tooth-adherent specific bacteria, time, susceptible tooth surface, and fermentable carbohydrates play a role in tooth decay (Tahir and Nazir, 2018). These four factors always cause caries, and if each one is not present, the tooth will not decay (Fejerskov, 1997; Sheiham, 2001; Wade, 2013; Kidd and Fejerskov, 2016; Tahir and Nazir, 2018). Tooth decay, in addition to its high prevalence, affects a wide range of age groups, and from children to the elderly, they are at risk for tooth decay (Smith and Szuster, 2000). The most harmful type of caries occurs in childhood and is named “early childhood caries” which has become a common public health problem among preschool children worldwide (Colak et al., 2013; Alazmah, 2017). Numerous factors, including the oral microbiome, affect the incidence of tooth decay in children (Dzidic et al., 2018). Bacteria are considered the main pathogen in tooth decay (Dzidic et al., 2018). Different lactobacilli promote the development of dental caries, but the most important microorganism in the development of dental caries is S. mutans (Loesche, 1996).

Oral Leukoplakia

In 1877, oral leukoplakia was described for the first time by Schwimmer (1877) Oral leukoplakia is one of the most common diseases of the oral mucosa which has malignant potential (van der Waal et al., 1997). According to the Pindborg study, leukoplakia is a white patch on the oral mucosa that cannot be removed and there is no other clinical diagnosis (Mehta et al., 1969; Bánóaczy, 1983). Different microorganisms like Fusobacterium, Leptotrichia, Campylobacter, and Rothia species were detected in oral leukoplakia (Amer et al., 2017).

Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Oral squamous cell carcinoma is the eighth most common cancer worldwide and is the most common oral malignancy (Scully and Bagan, 2009). Numerous hypotheses have been proposed for the association of microorganisms and their products with oral cancer (Perera et al., 2016). Acetaldehyde converted from ethanol, reactive oxygen species, reactive nitrogen species, and volatile sulfur compounds by bacteria are some examples of carcinogenic substances which can cause oral cancer (Meurman and Uittamo, 2008). The metabolization of alcohol to acetaldehyde can be happened by Streptococcus gordonii, Streptococcus mitis, Streptococcus oralis, Streptococcus salivarius, Streptococcus sanguinis, and Candida by the using of alcohol dehydrogenase enzyme (Mantzourani et al., 2009; Marttila et al., 2013). Also, hydrogen sulfide (H2S), methyl mercaptan (CH3SH), and dimethyl sulfide [(CH3)2S] are produced by P. gingivalis, Prevotella intermedia, Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans, and Fusobacterium nucleatum (Nakamura et al., 2018; Suzuki et al., 2019).

Application of Stem Cells-Derived Exosomes in Orodental Infections

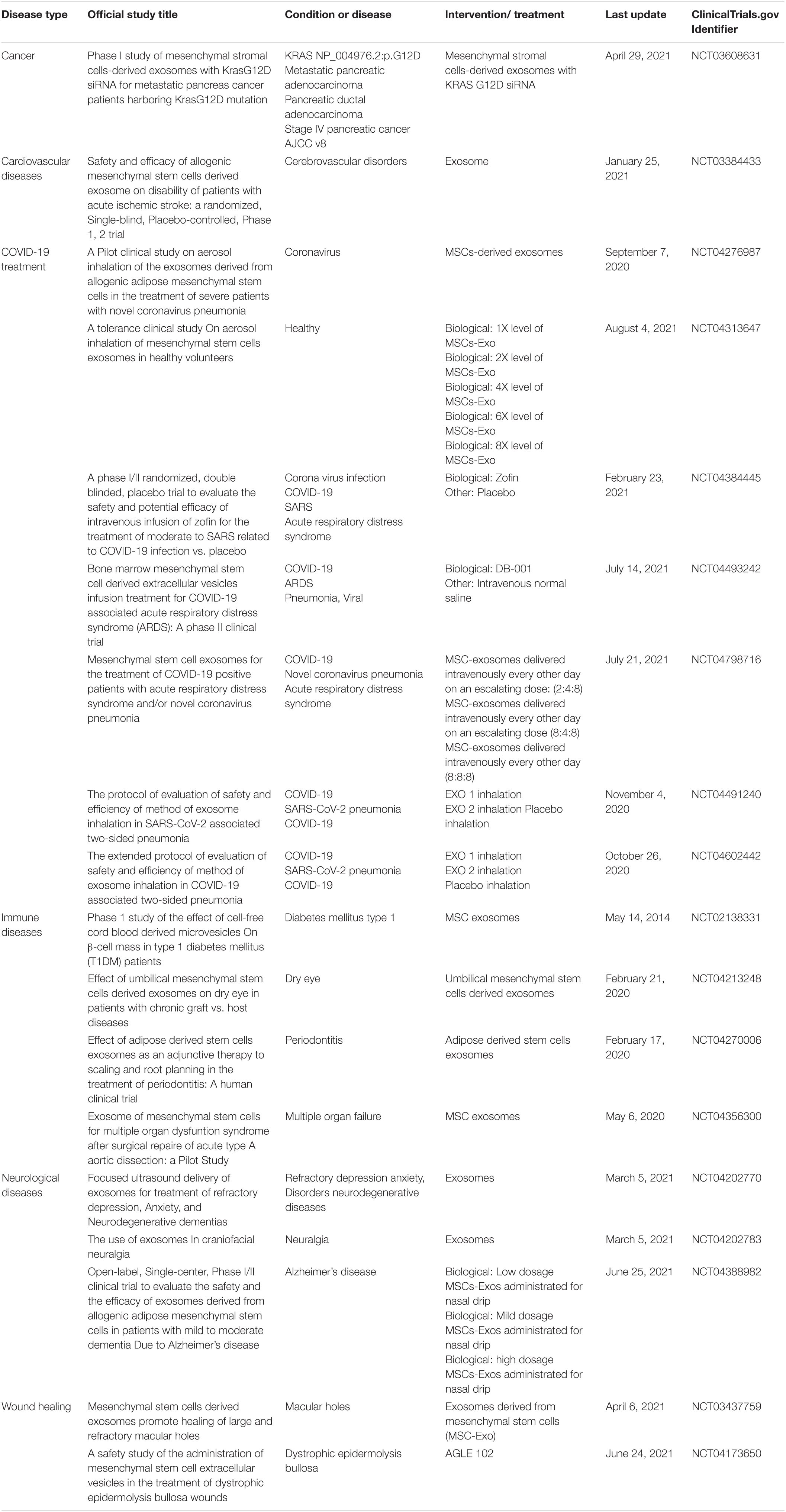

Mesenchymal stromal/stem cells (MSCs) are adult pluripotent stem cells with self−renewing potential that have been administered in different types of diseases (Undale et al., 2009; Fitzsimmons et al., 2018). The unique biomedical characteristic of MSCs is their stemness by stimulating their proliferation and differentiating into multi-lineage cells (da Silva Meirelles et al., 2006). MSCs are immunologically safe. Low expression of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I molecules and expression of only a few MHC class II molecules make MSCs low immunogenicity cells (Hass et al., 2011; Lee et al., 2014). Immunomodulatory and regenerative functions of MSCs have been shown in various types of diseases (Zappia et al., 2005; Corcione et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2013; Forbes et al., 2014; Le Blanc and Davies, 2015). MSCs-derived exosomes also have angiogenic potential that can improve ischemic diseases (Babaei and Rezaie, 2021). Senescence of MSCs during in vitro expansion makes the cells less productive and can increase disease severity by causing inflammaging (Lee and Yu, 2020). Also, weak engraftment of infused MSCs, and donor-dependent variations are some limitations of application MSCs in clinical trials (Karp and Leng Teo, 2009; Siegel et al., 2013; Li et al., 2016). An alternative method to improve MSC-based therapy is to use exosomes (Zavatti et al., 2020). Being free of immunogenic problems and not being trapped in the lung or liver like infused MSCs, and keeping the therapeutic functions of their cells of origin make MSC exosomes more suitable for clinical application than MSCs (Table 4; U.S. National Library of Medicine clinicaltrials.gov, 2021). The immunomodulatory function of MSCs and MSC-derived exosomes is the most important clinical feature of their application (Kang et al., 2020). Recent studies show that MSCs can inhibit T cells, B cells, natural killer cells, and dendritic cells and result in immune suppression (Bocelli-Tyndall et al., 2007; Li et al., 2012). Regarding MSCs properties, they have been used in clinical trials over several decades (Kabat et al., 2020). The MSCs mainly modulate the activity of the immune system by paracrine agents and exosomes, and the exosomes play an important role in cellular communication (Xu et al., 2016). MSCs-derived exosomes have a role in tissue regeneration, infection treatment, and inflammation control (Afshar et al., 2021; Zhankina et al., 2021).

Table 4. Some applications of MSCs-derived exosomes in recent clinical trials (U.S. National Library of Medicine clinicaltrials.gov, 2021).

Periodontitis is an inflammatory and destructive disease that has a relationship with several factors such as the pathogens, host inflammation, and immune responses, and the imbalance of multiple T helper cells 17 (Th17)/regulatory T cell (Treg) related cytokines (Wang et al., 2014; Silva et al., 2015; Pan et al., 2019). Bacterial infection is a primary factor in the development of periodontitis, but what ultimately causes periodontitis is improper regulation of the host immune system and inflammatory response (Hajishengallis, 2014, 2015). Th17 cells play a destructive role in the immune balance of periodontitis (Zhao et al., 2011). Over-regulation of Th17 and improper regulation of Treg may lead to periodontal disease through immune-mediated tissue destruction (Zhao et al., 2011; Yang et al., 2014; Karthikeyan et al., 2015). Periodontal ligament stem cells (PDLSCs)-derived exosomes have a similar role with exosomes from MSCs and PDLSCs-derived exosomes contain microRNA−155−5p and regulate Th17/Treg balance by targeting sirtuin−1 in chronic periodontitis (Zheng et al., 2019).

Interleukin-1 (IL-1) and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) are pro-inflammatory cytokines that are needed for periodontal inflammation and alveolar bone resorption (Delima et al., 2001; Grauballe et al., 2015). Macrophages that are activated by bacteria can release many inflammatory cytokines, causing gingiva destruction and alveolar bone resorption (Spiller and Koh, 2017; Dutzan et al., 2018; Garaicoa-Pazmino et al., 2019). Macrophages can be divided into two groups which are known as pro-inflammatory macrophages and anti-inflammatory macrophages and periodontal destruction occur following the imbalance of pro-inflammatory/anti-inflammatory macrophages (Gonzalez et al., 2015; Wynn and Vannella, 2016; Zhuang et al., 2019). Pro-inflammatory macrophages play an important role in the production of many inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin 1 beta (IL-1β) and TNF-α. Also, they can stimulate T cells and neutrophils, which cause the destruction of alveolar bone, and they can increase the local expression of receptor activator of nuclear factor ligand (RANKL), which causes osteoclast differentiation in the periodontium (Darveau, 2010; Hienz et al., 2015). In contrast, anti-inflammatory macrophages by secreting the anti-inflammatory mediators play a significant role in the elimination of inflammation and tissue regeneration and contribute to efferocytosis of the apoptotic osteoblastic cells so that mediating bone formation (Zhang et al., 2012; Shapouri-Moghaddam et al., 2018).

Dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs) as a population of dental−derived mesenchymal stem cells have easy accessibility and minimal ethical concerns for use (Mahdiyar et al., 2014; Potdar and Jethmalani, 2015; Mehrabani et al., 2017). The DPSCs have beneficial immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory properties and have a regulating effect on macrophages of the immune system (Lee et al., 2016; Omi et al., 2016; Galipeau and Sensebe, 2018). Since the therapeutic effects of stem cells are mainly related to the release of paracrine agents, stem cell-derived exosomes, as one of the most important paracrine mediators, show therapeutic effects through immunomodulation (Sun et al., 2018; Riazifar et al., 2019). DPSC-derived exosomes containing miR-1246 can facilitate the conversion of pro-inflammatory macrophages to anti-inflammatory macrophages in the periodontium of mice with periodontitis and accelerate the healing of alveolar bone and the periodontal epithelium (Shen et al., 2020).

In connection with the issue of infectious diseases, exosomes, in addition to treatment, can also help in the diagnosis of infectious diseases. For instance, hand, foot, and mouth disease (HFMD) is a common acute viral infection that has spread worldwide (Guerra et al., 2017). Human enterovirus 71 (EV71) and coxsackie virus A16 (CVA16) are the two main causes of HFMD (Yan et al., 2001; Osterback et al., 2009). HFMD has mild and severe forms which are known as mild HFMD and extremely severe HFMD (Jia et al., 2014), EV71 can cause extremely severe HFMD in which severe neurological symptoms occur and significant mortality (Huang et al., 1999). Many children with extremely severe HFMD die before a definitive diagnosis. There are no effective and reliable methods and tools for diagnosing (Li et al., 2014b; Hossain Khan et al., 2018). A study has shown that patients with different HFMD conditions express a specific type of exosomal miRNA profile (Jia et al., 2014). In fact, these exosomes provide a supplemental biomarker for differential infection stage at an early stage. Therefore, by examining the exosomal content, the disease can be diagnosed, and its different forms can be distinguished from each other (Jia et al., 2014). The immunomodulatory properties of exosomes have enhanced their use in the field of cancer biology. For example, dendritic cells-derived exosomes called “Dexosomes” can be used as a cell-free vaccine for cancer immunotherapy (Nikfarjam et al., 2020). Also, homeostasis and metastasis of tumor cells can change by exosomal and autophagy pathways (Salimi et al., 2020). Radiotherapy may affect the mechanism of paracrine intercellular communication within irradiated tumor tissue and surrounding cells (Jabbari et al., 2019).

Future Perspective of Exosome Therapy

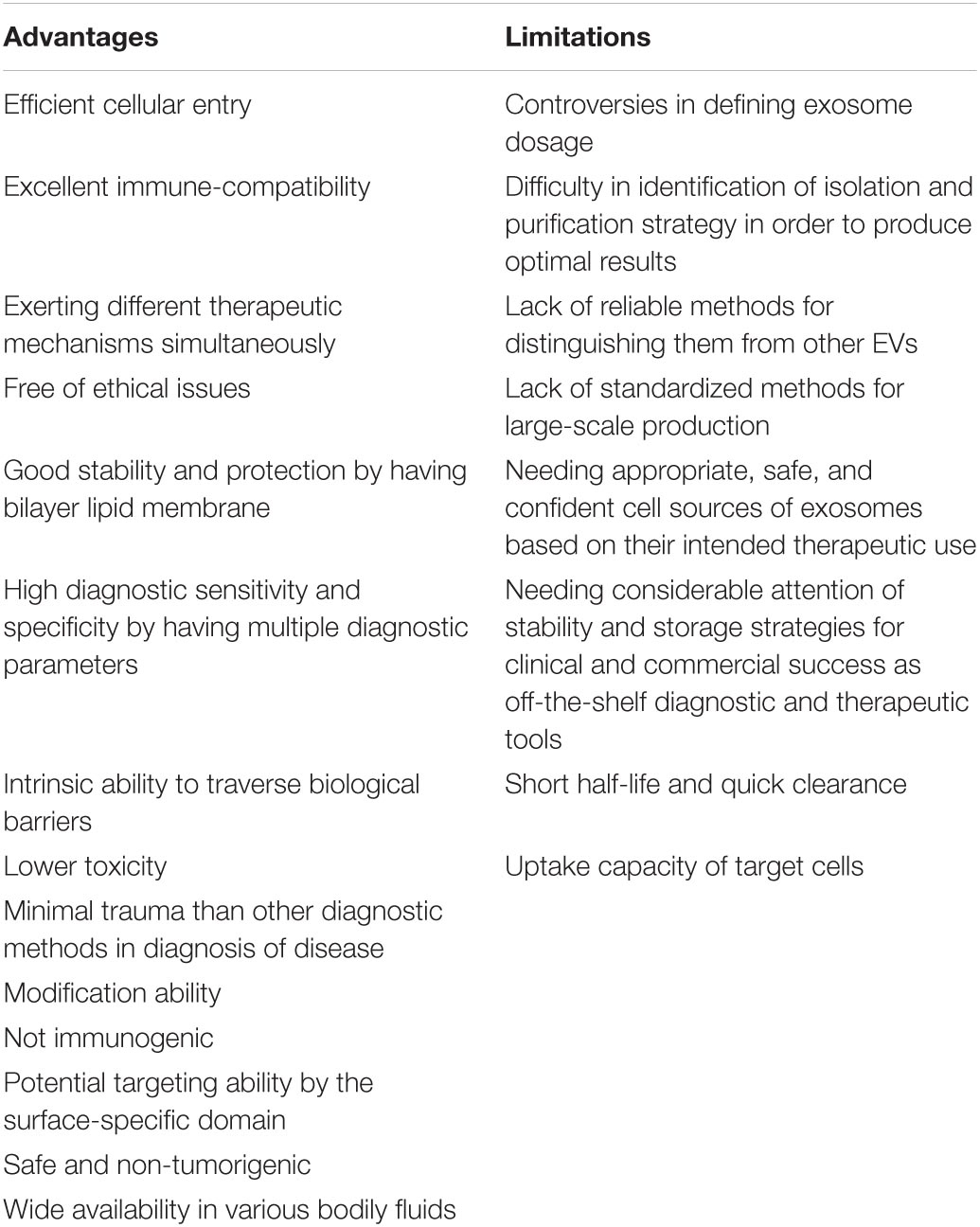

Over the last decades, the knowledge about biogenesis, molecular content, and biological function of exosomes have significant progress and a considerable amount of manuscripts have been published in this field. Exosome therapy as a cell-free therapy is emerging as a promising strategy for the treatment of several diseases, in particular inflammatory conditions. The characteristic properties of exosomes, including the transmission of exosomal competent, protecting it from extracellular degradation, and delivering it in a highly selective manner to target cells, have led to their numerous uses in various fields of treatment. The use of exosomes in clinical applications as well as in the treatment of diseases has both advantages and challenges, some of which are listed in Table 5. Despite the existing limitations, the use of exosomes as a new method in various fields of medical science is phenomenal and inspiring that need more data collection.

Table 5. Advantages and limitations of exosomes therapy in clinical applications (Tian et al., 2010; Takahashi et al., 2013; Lötvall et al., 2014; Yu et al., 2014; Théry et al., 2018; Xing et al., 2020; Babaei and Rezaie, 2021).

Conclusion

The oral cavity as a part of the digestive system which is in close contact with the external environment of the body and also by having its special microbiome is prone to a wide range of infectious diseases. In infectious diseases, the pathogenic mechanism of the microorganism is significantly affected by a special type of EVs called exosomes. In this way, these exosomes can be effective in the process of disease development and progression, as well as in the face of preventing and limiting the disease. Exosomes also play an important role in microbial infections by regulating the host immune system. In addition, exosomes can be used in the diagnosis of infectious diseases. Due to the importance of treating oral infectious diseases as well as the ease of using non-cellular therapies, mesenchymal stromal/stem cells-derived exosomes can be considered as a suitable and available option for the treatment of orodental infectious diseases that require more and more extensive studies in the future.

Author Contributions

NJ wrote the manuscript with support from AK and RM. MS helped supervise the project. All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abrami, L., Brandi, L., Moayeri, M., Brown, M. J., Krantz, B. A., Leppla, S. H., et al. (2013). Hijacking multivesicular bodies enables long-term and exosome-mediated long-distance action of anthrax toxin. Cell Rep. 5, 986–996. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.10.019

Aderem, A., and Ulevitch, R. J. (2000). Toll-like receptors in the induction of the innate immune response. Nature 406, 782–787. doi: 10.1038/35021228

Afshar, A., Zare, M., Farrar, Z., Hashemi, A., Baghban, N., Khoradmehr, A., et al. (2021). Exosomes of mesenchymal stem cells as nano-cargos for anti-SARS-CoV-2 asRNAs. Mod. Med. Lab. J. 4, 11–18.

Alexander, M., Hu, R., Runtsch, M. C., Kagele, D. A., Mosbruger, T. L., Tolmachova, T., et al. (2015). Exosome-delivered microRNAs modulate the inflammatory response to endotoxin. Nat. Commun. 6:7321. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8321

Amer, A., Galvin, S., Healy, C. M., and Moran, G. P. (2017). The microbiome of potentially malignant oral leukoplakia exhibits enrichment for Fusobacterium, Leptotrichia, Campylobacter, and Rothia Species. Front. Microbiol. 8:2391. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02391

Anderson, H. C. (1969). Vesicles associated with calcification in the matrix of epiphyseal cartilage. J. Cell Biol. 41, 59–72. doi: 10.1083/jcb.41.1.59

Anel, A., Gallego-Lleyda, A., de Miguel, D., Naval, J., and Martinez-Lostao, L. (2019). Role of exosomes in the regulation of T-cell mediated immune responses and in autoimmune disease. Cells 8:154. doi: 10.3390/cells8020154

Ansari, M. A., Singh, V. V., Dutta, S., Veettil, M. V., Dutta, D., Chikoti, L., et al. (2013). Constitutive interferon-inducible protein 16-inflammasome activation during Epstein-Barr virus latency I. II, and III in B and epithelial cells. J. Virol. 87, 8606–8623. doi: 10.1128/jvi.00805-13

Arenaccio, C., Chiozzini, C., Columba-Cabezas, S., Manfredi, F., Affabris, E., Baur, A., et al. (2014). Exosomes from human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)-infected cells license quiescent CD4+ T lymphocytes to replicate HIV-1 through a Nef- and ADAM17-dependent mechanism. J. Virol. 88, 11529–11539. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01712-14

Babaei, M., and Rezaie, J. (2021). Application of stem cell-derived exosomes in ischemic diseases: opportunity and limitations. J. Transl. Med. 19:196. doi: 10.1186/s12967-021-02863-w

Bain, B. J. (2017). Structure and function of red and white blood cells. Medicine 45, 187–193. doi: 10.1016/j.mpmed.2017.01.011

Bánóaczy, J. (1983). Oral leukoplakia and other white lesions of the oral mucosa related to dermatological disorders. J. Cutaneous Pathol. 10, 238–256. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.1983.tb01490.x

Barclay, R. A., Schwab, A., DeMarino, C., Akpamagbo, Y., Lepene, B., Kassaye, S., et al. (2017). Exosomes from uninfected cells activate transcription of latent HIV-1. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 11682–11701.

Bhatnagar, S., Shinagawa, K., Castellino, F. J., and Schorey, J. S. (2007). Exosomes released from macrophages infected with intracellular pathogens stimulate a proinflammatory response in vitro and in vivo. Blood 110, 3234–3244. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-03-079152

Bocelli-Tyndall, C., Bracci, L., Spagnoli, G., Braccini, A., Bouchenaki, M., Ceredig, R., et al. (2007). Bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cells (BM-MSCs) from healthy donors and auto-immune disease patients reduce the proliferation of autologous-and allogeneic-stimulated lymphocytes in vitro. Rheumatology 46, 403–408. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel267

Bonucci, E. (1967). Fine structure of early cartilage calcification. J. Ultrastruct. Res. 20, 33–50. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5320(67)80034-0

Cao, L., Xu, H., Wang, G., Liu, M., Tian, D., and Yuan, Z. (2019). Extracellular vesicles derived from bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells attenuate dextran sodium sulfate-induced ulcerative colitis by promoting M2 macrophage polarization. Int. Immunopharmacol. 72, 264–274. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2019.04.020

Casarin, R. C., Barbagallo, A., Meulman, T., Santos, V. R., Sallum, E. A., Nociti, F. H., et al. (2013). Subgingival biodiversity in subjects with uncontrolled type-2 diabetes and chronic periodontitis. J. Periodontal Res. 48, 30–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2012.01498.x

Caselli, E., Fabbri, C., D’Accolti, M., Soffritti, I., Bassi, C., Mazzacane, S., et al. (2020). Defining the oral microbiome by whole-genome sequencing and resistome analysis: the complexity of the healthy picture. BMC Microbiol. 20:120. doi: 10.1186/s12866-020-01801-y

Cerny, J., and Striz, I. (2019). Adaptive innate immunity or innate adaptive immunity? Clin. Sci. (Lond.) 133, 1549–1565. doi: 10.1042/CS20180548

Chang, C.-L., Chen, C.-H., Chiang, J. Y., Sun, C.-K., Chen, Y.-L., Chen, K.-H., et al. (2019). Synergistic effect of combined melatonin and adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cell (ADMSC)-derived exosomes on amelioration of dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced acute colitis. Am. J. Transl. Res. 11:2706.

Chapuy-Regaud, S., Dubois, M., Plisson-Chastang, C., Bonnefois, T., Lhomme, S., Bertrand-Michel, J., et al. (2017). Characterization of the lipid envelope of exosome encapsulated HEV particles protected from the immune response. Biochimie 141, 70–79. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2017.05.003

Chen, L., Deng, H., Cui, H., Fang, J., Zuo, Z., Deng, J., et al. (2018). Inflammatory responses and inflammation-associated diseases in organs. Oncotarget 9, 7204–7218. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.23208

Cho, I., and Blaser, M. J. (2012). The human microbiome: at the interface of health and disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 13, 260–270. doi: 10.1038/nrg3182

Cianciola, L. J., Park, B. H., Bruck, E., Mosovich, L., and Genco, R. J. (1982). Prevalence of periodontal disease in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (juvenile diabetes). J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 104, 653–660. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1982.0240

Cobb, C. M., and Killoy, W. J. (1990). Microbial colonization in human periodontal disease: an illustrated tutorial on selected ultrastructural and ecologic considerations. Scanning Microsc. 4, 675–690; discussion 690–1.

Colak, H., Dulgergil, C. T., Dalli, M., and Hamidi, M. M. (2013). Early childhood caries update: a review of causes, diagnoses, and treatments. J. Nat. Sci. Biol. Med. 4, 29–38. doi: 10.4103/0976-9668.107257

Colino, J., and Snapper, C. M. (2007). Dendritic cell-derived exosomes express a Streptococcus pneumoniae capsular polysaccharide type 14 cross-reactive antigen that induces protective immunoglobulin responses against pneumococcal infection in mice. Infect. Immun. 75, 220–230. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01217-06

Corcione, A., Benvenuto, F., Ferretti, E., Giunti, D., Cappiello, V., Cazzanti, F., et al. (2006). Human mesenchymal stem cells modulate B-cell functions. Blood 107, 367–372. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2657

Cosset, F. L., and Dreux, M. (2014). HCV transmission by hepatic exosomes establishes a productive infection. J. Hepatol. 60, 674–675. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.10.015

Crotty, S., and Ahmed, R. (eds.) (2004). “Immunological memory in humans,” in Seminars in Immunology (Amsterdam: Elsevier).

Csaba, G., Kovacs, P., and Pallinger, E. (2003). Gender differences in the histamine and serotonin content of blood, peritoneal and thymic cells: a comparison with mast cells. Cell Biol. Int. 27, 387–389. doi: 10.1016/s1065-6995(03)00017-9

da Silva Meirelles, L., Chagastelles, P. C., and Nardi, N. B. (2006). Mesenchymal stem cells reside in virtually all post-natal organs and tissues. J. Cell Sci. 119(Pt. 11), 2204–2213. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02932

Dang, A. T., Cotton, S., Sankaran-Walters, S., Li, C. S., Lee, C. Y., Dandekar, S., et al. (2012). Evidence of an increased pathogenic footprint in the lingual microbiome of untreated HIV infected patients. BMC Microbiol. 12:153. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-12-153

Darveau, R. P. (2010). Periodontitis: a polymicrobial disruption of host homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8, 481–490. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2337

Davies, D. R., and Cohen, G. H. (1996). Interactions of protein antigens with antibodies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 7–12.

Delima, A. J., Oates, T., Assuma, R., Schwartz, Z., Cochran, D., Amar, S., et al. (2001). Soluble antagonists to interleukin-1 (IL-1) and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibits loss of tissue attachment in experimental periodontitis. J. Clin. Periodontol. 28, 233–240. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2001.028003233.x

Deo, P. N., and Deshmukh, R. (2019). Oral microbiome: unveiling the fundamentals. J. Oral Maxillofac. Pathol. 23, 122–128. doi: 10.4103/jomfp.JOMFP_304_18

Dorfer, C. E., Becher, H., Ziegler, C. M., Kaiser, C., Lutz, R., Jorss, D., et al. (2004). The association of gingivitis and periodontitis with ischemic stroke. J. Clin. Periodontol. 31, 396–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.2004.00579.x

Doyle, L. M., and Wang, M. Z. (2019). Overview of extracellular vesicles, their origin, composition, purpose, and methods for exosome isolation and analysis. Cells 8:727. doi: 10.3390/cells8070727

Dunkelberger, J. R., and Song, W. C. (2010). Complement and its role in innate and adaptive immune responses. Cell Res. 20, 34–50. doi: 10.1038/cr.2009.139

Dutzan, N., Kajikawa, T., Abusleme, L., Greenwell-Wild, T., Zuazo, C. E., Ikeuchi, T., et al. (2018). A dysbiotic microbiome triggers TH17 cells to mediate oral mucosal immunopathology in mice and humans. Sci. Transl. Med. 10:eaat0797. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aat0797

Dzidic, M., Collado, M. C., Abrahamsson, T., Artacho, A., Stensson, M., Jenmalm, M. C., et al. (2018). Oral microbiome development during childhood: an ecological succession influenced by postnatal factors and associated with tooth decay. ISME J. 12, 2292–2306. doi: 10.1038/s41396-018-0204-z

Emrich, L. J., Shlossman, M., and Genco, R. J. (1991). Periodontal disease in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J. Periodontol. 62, 123–131.

Evans, S. S., Repasky, E. A., and Fisher, D. T. (2015). Fever and the thermal regulation of immunity: the immune system feels the heat. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 15, 335–349. doi: 10.1038/nri3843

Fan, X., Alekseyenko, A. V., Wu, J., Peters, B. A., Jacobs, E. J., Gapstur, S. M., et al. (2018). Human oral microbiome and prospective risk for pancreatic cancer: a population-based nested case-control study. Gut 67, 120–127. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-312580

Fejerskov, O. (1997). Concepts of dental caries and their consequences for understanding the disease. Commun. Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 25, 5–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1997.tb00894.x

Feng, Z., Hensley, L., McKnight, K. L., Hu, F., Madden, V., Ping, L., et al. (2013). A pathogenic picornavirus acquires an envelope by hijacking cellular membranes. Nature 496, 367–371. doi: 10.1038/nature12029

Fitzsimmons, R. E. B., Mazurek, M. S., Soos, A., and Simmons, C. A. (2018). Mesenchymal stromal/stem cells in regenerative medicine and tissue engineering. Stem Cells Int. 2018:8031718. doi: 10.1155/2018/8031718

Forbes, G. M., Sturm, M. J., Leong, R. W., Sparrow, M. P., Segarajasingam, D., Cummins, A. G., et al. (2014). A phase 2 study of allogeneic mesenchymal stromal cells for luminal Crohn’s disease refractory to biologic therapy. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 12, 64–71. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.06.021

Frank, S. A. (2000). Specific and non-specific defense against parasitic attack. J. Theor. Biol. 202, 283–304. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.1999.1054

Galipeau, J., and Sensebe, L. (2018). Mesenchymal stromal cells: clinical challenges and therapeutic opportunities. Cell Stem Cell 22, 824–833. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2018.05.004

Ganz, T. (2003). Defensins: antimicrobial peptides of innate immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 3, 710–720. doi: 10.1038/nri1180

Garaicoa-Pazmino, C., Fretwurst, T., Squarize, C. H., Berglundh, T., Giannobile, W. V., Larsson, L., et al. (2019). Characterization of macrophage polarization in periodontal disease. J. Clin. Periodontol. 46, 830–839. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.13156

Gehrmann, U., Qazi, K. R., Johansson, C., Hultenby, K., Karlsson, M., Lundeberg, L., et al. (2011). Nanovesicles from Malassezia sympodialis and host exosomes induce cytokine responses–novel mechanisms for host-microbe interactions in atopic eczema. PLoS One 6:e21480. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021480

Gerba, C. P. (2015). “Environmentally transmitted pathogens,” in Environmental Microbiology, eds R. M. Maier, I. L. Pepper, and C. P. Gerba (Amsterdam: Elsevier), 509–550.

Gonzalez, O. A., Novak, M. J., Kirakodu, S., Stromberg, A., Nagarajan, R., Huang, C. B., et al. (2015). Differential gene expression profiles reflecting macrophage polarization in aging and periodontitis gingival tissues. Immunol. Invest. 44, 643–664. doi: 10.3109/08820139.2015.1070269

Goodson, J. M., Groppo, D., Halem, S., and Carpino, E. (2009). Is obesity an oral bacterial disease? J. Dent. Res. 88, 519–523. doi: 10.1177/0022034509338353

Grauballe, M. B., Ostergaard, J. A., Schou, S., Flyvbjerg, A., and Holmstrup, P. (2015). Effects of TNF-alpha blocking on experimental periodontitis and type 2 diabetes in obese diabetic Zucker rats. J. Clin. Periodontol. 42, 807–816. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12442

Guerra, A. M., Orille, E., and Waseem, M. (2017). Hand Foot and Mouth Disease. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls.

Hajishengallis, G. (2014). Immunomicrobial pathogenesis of periodontitis: keystones, pathobionts, and host response. Trends Immunol. 35, 3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2013.09.001

Hajishengallis, G. (2015). Periodontitis: from microbial immune subversion to systemic inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 15, 30–44. doi: 10.1038/nri3785

Han, Y. W., Fardini, Y., Chen, C., Iacampo, K. G., Peraino, V. A., Shamonki, J. M., et al. (2010). Term stillbirth caused by oral Fusobacterium nucleatum. Obstet. Gynecol. 115(2 Pt. 2), 442–445. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181cb9955

Han, Y. W., Redline, R. W., Li, M., Yin, L., Hill, G. B., and McCormick, T. S. (2004). Fusobacterium nucleatum induces premature and term stillbirths in pregnant mice: implication of oral bacteria in preterm birth. Infect. Immun. 72, 2272–2279. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.4.2272-2279.2004

Hass, R., Kasper, C., Böhm, S., and Jacobs, R. (2011). Different populations and sources of human mesenchymal stem cells (MSC): a comparison of adult and neonatal tissue-derived MSC. Cell Commun. Signal. 9:12. doi: 10.1186/1478-811X-9-12

Heron, S. E., and Elahi, S. (2017). HIV infection and compromised mucosal immunity: oral manifestations and systemic inflammation. Front. Immunol. 8:241. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00241

Herrmann, I. K., Wood, M. J. A., and Fuhrmann, G. (2021). Extracellular vesicles as a next-generation drug delivery platform. Nat. Nanotechnol. 16, 748–759. doi: 10.1038/s41565-021-00931-2

Hienz, S. A., Paliwal, S., and Ivanovski, S. (2015). Mechanisms of bone resorption in periodontitis. J. Immunol. Res. 2015:615486.

Hossain Khan, M. A., Anwar, K. S., Muraduzzaman, A. K. M., Hossain Mollah, M. A., Akhter-Ul-Alam, S. M., Munisul Islam, K., et al. (2018). Emerging hand foot mouth disease in Bangladeshi children- first report of rapid appraisal on pocket outbreak: clinico-epidemiological perspective implicating public health emergency. F1000Res. 7:1156. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.15170.3

Huang, C. C., Liu, C. C., Chang, Y. C., Chen, C. Y., Wang, S. T., and Yeh, T. F. (1999). Neurologic complications in children with enterovirus 71 infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 341, 936–942. doi: 10.1056/nejm199909233411302

Husmann, M., Beckmann, E., Boller, K., Kloft, N., Tenzer, S., Bobkiewicz, W., et al. (2009). Elimination of a bacterial pore-forming toxin by sequential endocytosis and exocytosis. FEBS Lett. 583, 337–344. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.12.028

Jabbari, N., Nawaz, M., and Rezaie, J. (2019). Bystander effects of ionizing radiation: conditioned media from X-ray irradiated MCF-7 cells increases the angiogenic ability of endothelial cells. Cell Commun. Signal. 17:165. doi: 10.1186/s12964-019-0474-8

Janeway, C. A. Jr., Travers, P., Walport, M., and Shlomchik, M. J. (2001a). The Complement System and Innate Immunity. Immunobiology: The Immune System in Health and Disease, 5th Edn. New York, NY: Garland Science.

Janeway, C. A. Jr., Travers, P., Walport, M., and Shlomchik, M. J. (2001b). The Front Line of Host Defense. Immunobiology: The Immune System in Health and Disease, 5th Edn. New York, NY: Garland Science.

Jaworski, E., Narayanan, A., Van Duyne, R., Shabbeer-Meyering, S., Iordanskiy, S., Saifuddin, M., et al. (2014). Human T-lymphotropic virus type 1-infected cells secrete exosomes that contain Tax protein. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 22284–22305. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.549659

Jia, H. L., He, C. H., Wang, Z. Y., Xu, Y. F., Yin, G. Q., Mao, L. J., et al. (2014). MicroRNA expression profile in exosome discriminates extremely severe infections from mild infections for hand, foot and mouth disease. BMC Infect. Dis. 14:506. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-14-506

Kabat, M., Bobkov, I., Kumar, S., and Grumet, M. (2020). Trends in mesenchymal stem cell clinical trials 2004-2018: is efficacy optimal in a narrow dose range? Stem Cells Transl. Med. 9, 17–27. doi: 10.1002/sctm.19-0202

Kang, J. Y., Oh, M. K., Joo, H., Park, H. S., Chae, D. H., Kim, J., et al. (2020). Xeno-Free condition enhances therapeutic functions of human Wharton’s Jelly-Derived mesenchymal stem cells against experimental colitis by upregulated indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase activity. J. Clin. Med. 9:2913. doi: 10.3390/jcm9092913

Karp, J. M., and Leng Teo, G. S. (2009). Mesenchymal stem cell homing: the devil is in the details. Cell Stem Cell 4, 206–216. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.02.001

Karpman, D., and Ståhl, A-l, and Arvidsson, I. (2017). Extracellular vesicles in renal disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 13, 545–562. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2017.98

Karthikeyan, B., Talwar, Arun, K. V., and Kalaivani, S. (2015). Evaluation of transcription factor that regulates T helper 17 and regulatory T cells function in periodontal health and disease. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 7(Suppl. 2), S672–S676. doi: 10.4103/0975-7406.163602

Kato, T., Fahrmann, J. F., Hanash, S. M., and Vykoukal, J. (2020). Extracellular vesicles mediate B cell immune response and are a potential target for cancer therapy. Cells 9:1518. doi: 10.3390/cells9061518

Kidd, E. A., and Fejerskov, O. (2016). Essentials of Dental Caries. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kilian, M., Chapple, I. L., Hannig, M., Marsh, P. D., Meuric, V., Pedersen, A. M., et al. (2016). The oral microbiome - an update for oral healthcare professionals. Br. Dent. J. 221, 657–666. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2016.865

Kim, D. K., Kang, B., Kim, O. Y., Choi, D. S., Lee, J., Kim, S. R., et al. (2013). EVpedia: an integrated database of high-throughput data for systemic analyses of extracellular vesicles. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2:20384. doi: 10.3402/jev.v2i0.20384

Kim, M. J., Jung, B. K., Cho, J., Song, H., Pyo, K. H., Lee, J. M., et al. (2016). Exosomes secreted by Toxoplasma gondii-infected L6 cells: their effects on host cell proliferation and cell cycle changes. Korean J. Parasitol. 54, 147–154. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2016.54.2.147

Kirtane, A. R., Verma, M., Karandikar, P., Furin, J., Langer, R., and Traverso, G. (2021). Nanotechnology approaches for global infectious diseases. Nat. Nanotechnol. 16, 369–384. doi: 10.1038/s41565-021-00866-8

Kononen, E., Gursoy, M., and Gursoy, U. K. (2019). Periodontitis: a multifaceted disease of tooth-supporting tissues. J. Clin. Med. 8:1135. doi: 10.3390/jcm8081135

Koren, O., Spor, A., Felin, J., Fak, F., Stombaugh, J., Tremaroli, V., et al. (2011). Human oral, gut, and plaque microbiota in patients with atherosclerosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108(Suppl. 1), 4592–4598. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011383107

Kouwaki, T., Fukushima, Y., Daito, T., Sanada, T., Yamamoto, N., Mifsud, E. J., et al. (2016). Extracellular vesicles including exosomes regulate innate immune responses to hepatitis B virus infection. Front Immunol. 7:335. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00335

Krzysciak, W., Jurczak, A., Koscielniak, D., Bystrowska, B., and Skalniak, A. (2014). The virulence of Streptococcus mutans and the ability to form biofilms. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 33, 499–515. doi: 10.1007/s10096-013-1993-7

Lamm, M. E. (1997). Interaction of antigens and antibodies at mucosal surfaces. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 51, 311–340. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.51.1.311

Larabi, A., Barnich, N., and Nguyen, H. T. T. (2020). Emerging role of exosomes in diagnosis and treatment of infectious and inflammatory bowel diseases. Cells 9:1111. doi: 10.3390/cells9051111

Le Blanc, K., and Davies, L. C. (2015). Mesenchymal stromal cells and the innate immune response. Immunol. Lett. 168, 140–146. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2015.05.004

Lee, B. C., and Yu, K. R. (2020). Impact of mesenchymal stem cell senescence on inflammaging. BMB Rep. 53, 65–73. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2020.53.2.291

Lee, M., Jeong, S. Y., Ha, J., Kim, M., Jin, H. J., Kwon, S. J., et al. (2014). Low immunogenicity of allogeneic human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells in vitro and in vivo. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 446, 983–989. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.03.051

Lee, S., Zhang, Q. Z., Karabucak, B., and Le, A. D. (2016). DPSCs from inflamed pulp modulate macrophage function via the TNF-alpha/IDO Axis. J. Dent. Res. 95, 1274–1281. doi: 10.1177/0022034516657817

Li, L., Chen, X., Wang, W. E., and Zeng, C. (2016). How to improve the survival of transplanted mesenchymal stem cell in ischemic heart? Stem Cells Int. 2016:9682757. doi: 10.1155/2016/9682757

Li, X., Liu, L., Meng, D., Wang, D., Zhang, J., Shi, D., et al. (2012). Enhanced apoptosis and senescence of bone-marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Stem Cells Dev. 21, 2387–2394. doi: 10.1089/scd.2011.0447

Li, X. B., Zhang, Z. R., Schluesener, H. J., and Xu, S. Q. (2006). Role of exosomes in immune regulation. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 10, 364–375.

Li, Y., Saxena, D., Chen, Z., Liu, G., Abrams, W. R., Phelan, J. A., et al. (2014a). HIV infection and microbial diversity in saliva. J. Clin. Microbiol. 52, 1400–1411. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02954-13

Li, Y., Zhang, J., and Zhang, X. (2014b). Modeling and preventive measures of hand, foot and mouth disease (HFMD) in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 11, 3108–3117. doi: 10.3390/ijerph110303108

Lin, X. P., Almqvist, N., and Telemo, E. (2005). Human small intestinal epithelial cells constitutively express the key elements for antigen processing and the production of exosomes. Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 35, 122–128. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2005.05.011

Lindheim, L., Bashir, M., Munzker, J., Trummer, C., Zachhuber, V., Pieber, T. R., et al. (2016). The salivary microbiome in polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) and its association with disease-related parameters: a pilot study. Front. Microbiol. 7:1270. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01270

Liu, S., Hossinger, A., Hofmann, J. P., Denner, P., and Vorberg, I. M. (2016). Horizontal transmission of cytosolic Sup35 prions by extracellular vesicles. mBio 7:e00915-16. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00915-16

Loesche, W. J. (1996). “Microbiology of dental decay and periodontal disease,” in Medical Microbiology, 4th Edn, ed. S. Baron (Galveston, TX: University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston).

Lötvall, J., Hill, A. F., Hochberg, F., Buzás, E. I., Di Vizio, D., Gardiner, C., et al. (2014). Minimal Experimental Requirements for Definition of Extracellular Vesicles and Their Functions: A Position Statement From the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles. Abingdon: Taylor & Francis.

Maas, S. L. N., Breakefield, X. O., and Weaver, A. M. (2017). Extracellular vesicles: unique intercellular delivery vehicles. Trends Cell Biol. 27, 172–188. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2016.11.003

Madianos, P. N., Bobetsis, Y. A., and Offenbacher, S. (2013). Adverse pregnancy outcomes (APOs) and periodontal disease: pathogenic mechanisms. J. Clin. Periodontol. 40(Suppl. 14), S170–S180.

Madison, M. N., Jones, P. H., and Okeoma, C. M. (2015). Exosomes in human semen restrict HIV-1 transmission by vaginal cells and block intravaginal replication of LP-BM5 murine AIDS virus complex. Virology 482, 189–201. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2015.03.040

Mahdiyar, P., Zare, S., Robati, R., Dianatpour, M., Torabi, K., Tamadon, A., et al. (2014). Isolation, culture, and characterization of human dental pulp mesenchymal stem cells. Int. J. Pediatr. 2:44.

Mantzourani, M., Fenlon, M., and Beighton, D. (2009). Association between Bifidobacteriaceae and the clinical severity of root caries lesions. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 24, 32–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302X.2008.00470.x

Mao, F., Wu, Y., Tang, X., Kang, J., Zhang, B., Yan, Y., et al. (2017). Exosomes derived from human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells relieve inflammatory bowel disease in mice. Biomed Res. Int. 2017:5356760. doi: 10.1155/2017/5356760

Marsh, P. D., Head, D. A., and Devine, D. A. (2015). Ecological approaches to oral biofilms: control without killing. Caries Res. 49(Suppl. 1), 46–54. doi: 10.1159/000377732

Martin-Jaular, L., Nakayasu, E. S., Ferrer, M., Almeida, I. C., and Del Portillo, H. A. (2011). Exosomes from Plasmodium yoelii-infected reticulocytes protect mice from lethal infections. PLoS One 6:e26588. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026588

Marttila, E., Bowyer, P., Sanglard, D., Uittamo, J., Kaihovaara, P., Salaspuro, M., et al. (2013). Fermentative 2-carbon metabolism produces carcinogenic levels of acetaldehyde in Candida albicans. Mol. Oral Microbiol. 28, 281–291. doi: 10.1111/omi.12024

Mathivanan, S., Fahner, C. J., Reid, G. E., and Simpson, R. J. (2012). ExoCarta 2012: database of exosomal proteins, RNA and lipids. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, D1241–D1244. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr828

McDade, T. W., Georgiev, A. V., and Kuzawa, C. W. (2016). Trade-offs between acquired and innate immune defenses in humans. Evol. Med. Public Health 2016, 1–16. doi: 10.1093/emph/eov033

Mehrabani, D., Mahdiyar, P., Torabi, K., Robati, R., Zare, S., Dianatpour, M., et al. (2017). Growth kinetics and characterization of human dental pulp stem cells: comparison between third molar and first premolar teeth. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 9:e172. doi: 10.4317/jced.52824

Mehta, F. S., Pindborg, J., Gupta, P., and Daftary, D. (1969). Epidemiologic and histologic study of oral cancer and leukoplakia among 50,915 villagers in India. Cancer 24, 832–849. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196910)24:4<832::aid-cncr2820240427>3.0.co;2-u

Meurman, J. H., and Uittamo, J. (2008). Oral micro-organisms in the etiology of cancer. Acta Odontol. Scand. 66, 321–326. doi: 10.1080/00016350802446527

Miklossy, J. (1993). Alzheimer’s disease–a spirochetosis? Neuroreport 4, 841–848. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199307000-00002

Mineoka, T., Awano, S., Rikimaru, T., Kurata, H., Yoshida, A., Ansai, T., et al. (2008). Site-specific development of periodontal disease is associated with increased levels of Porphyromonas gingivalis, Treponema denticola, and Tannerella forsythia in subgingival plaque. J. Periodontol. 79, 670–676. doi: 10.1902/jop.2008.070398

Mori, Y., Koike, M., Moriishi, E., Kawabata, A., Tang, H., Oyaizu, H., et al. (2008). Human herpesvirus-6 induces MVB formation, and virus egress occurs by an exosomal release pathway. Traffic 9, 1728–1742. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2008.00796.x

Moynihan, P., and Petersen, P. E. (2004). Diet, nutrition and the prevention of dental diseases. Public Health Nutr. 7, 201–226. doi: 10.1079/phn2003589

Murray, C. J., Ortblad, K. F., Guinovart, C., Lim, S. S., Wolock, T. M., Roberts, D. A., et al. (2014). Global, regional, and national incidence and mortality for HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria during 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 384, 1005–1070. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60844-8

Nakamura, S., Shioya, K., Hiraoka, B. Y., Suzuki, N., Hoshino, T., Fujiwara, T., et al. (2018). Porphyromonas gingivalis hydrogen sulfide enhances methyl mercaptan-induced pathogenicity in mouse abscess formation. Microbiology (Reading) 164, 529–539. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.000640

Nanci, A., and Bosshardt, D. D. (2006). Structure of periodontal tissues in health and disease. Periodontol 2000 40, 11–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2005.00141.x

Nata, T., Fujiya, M., Ueno, N., Moriichi, K., Konishi, H., Tanabe, H., et al. (2013). MicroRNA-146b improves intestinal injury in mouse colitis by activating nuclear factor-κB and improving epithelial barrier function. J. Gene Med. 15, 249–260. doi: 10.1002/jgm.2717

Nikfarjam, S., Rezaie, J., Kashanchi, F., and Jafari, R. (2020). Dexosomes as a cell-free vaccine for cancer immunotherapy. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 39:258. doi: 10.1186/s13046-020-01781-x

O’Brien, K., Breyne, K., Ughetto, S., Laurent, L. C., and Breakefield, X. O. (2020). RNA delivery by extracellular vesicles in mammalian cells and its applications. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 21, 585–606. doi: 10.1038/s41580-020-0251-y

Omi, M., Hata, M., Nakamura, N., Miyabe, M., Kobayashi, Y., Kamiya, H., et al. (2016). Transplantation of dental pulp stem cells suppressed inflammation in sciatic nerves by promoting macrophage polarization towards anti-inflammation phenotypes and ameliorated diabetic polyneuropathy. J. Diabetes Investig. 7, 485–496. doi: 10.1111/jdi.12452

Oppenheim, J., Biragyn, A., Kwak, L., and Yang, D. (2003). Roles of antimicrobial peptides such as defensins in innate and adaptive immunity. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 62(Suppl. 2), ii17–ii21. doi: 10.1136/ard.62.suppl_2.ii17

Osterback, R., Vuorinen, T., Linna, M., Susi, P., Hyypia, T., and Waris, M. (2009). Coxsackievirus A6 and hand, foot, and mouth disease, Finland. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 15, 1485–1488.

Ozdemir, D. (2013). Dental caries: the most common disease worldwide and preventive strategies. Int. J. Biol. 5:55.

Pan, W., Wang, Q., and Chen, Q. (2019). The cytokine network involved in the host immune response to periodontitis. Int. J. Oral Sci. 11:30. doi: 10.1038/s41368-019-0064-z

Perera, M., Al-Hebshi, N. N., Speicher, D. J., Perera, I., and Johnson, N. W. (2016). Emerging role of bacteria in oral carcinogenesis: a review with special reference to perio-pathogenic bacteria. J. Oral Microbiol. 8:32762. doi: 10.3402/jom.v8.32762

Pihlstrom, B. L., Michalowicz, B. S., and Johnson, N. W. (2005). Periodontal diseases. Lancet 366, 1809–1820.

Poole, S., Singhrao, S. K., Kesavalu, L., Curtis, M. A., and Crean, S. (2013). Determining the presence of periodontopathic virulence factors in short-term postmortem Alzheimer’s disease brain tissue. J. Alzheimers Dis. 36, 665–677. doi: 10.3233/JAD-121918

Potdar, P. D., and Jethmalani, Y. D. (2015). Human dental pulp stem cells: applications in future regenerative medicine. World J. Stem Cells 7, 839–851. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v7.i5.839

Qian, X., Xu, C., Fang, S., Zhao, P., Wang, Y., Liu, H., et al. (2016). Exosomal MicroRNAs derived from umbilical mesenchymal stem cells inhibit hepatitis C virus infection. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 5, 1190–1203. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2015-0348

Raposo, G., Tenza, D., Mecheri, S., Peronet, R., Bonnerot, C., and Desaymard, C. (1997). Accumulation of major histocompatibility complex class II molecules in mast cell secretory granules and their release upon degranulation. Mol. Biol. Cell 8, 2631–2645. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.12.2631

Read, E., Curtis, M. A., and Neves, J. F. (2021). The role of oral bacteria in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 18, 731–742. doi: 10.1038/s41575-021-00488-4

Riazifar, M., Mohammadi, M. R., Pone, E. J., Yeri, A., Lasser, C., Segaliny, A. I., et al. (2019). Stem cell-derived exosomes as nanotherapeutics for autoimmune and neurodegenerative disorders. ACS Nano 13, 6670–6688. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.9b01004

Rich, R. R., and Chaplin, D. D. (2019). “The human immune response,” in Clinical Immunology, eds R. R. Rich, T. A. Fleisher, W. T. Shearer, H. W. Schroeder, A. J. Frew, and C. M. Weyand (Amsterdam: Elsevier), 3–17.

Riviere, G. R., Riviere, K. H., and Smith, K. S. (2002). Molecular and immunological evidence of oral Treponema in the human brain and their association with Alzheimer’s disease. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 17, 113–118. doi: 10.1046/j.0902-0055.2001.00100.x

Rylander, H., Ramberg, P., Blohme, G., and Lindhe, J. (1987). Prevalence of periodontal disease in young diabetics. J. Clin. Periodontol. 14, 38–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1987.tb01511.x

Salimi, L., Akbari, A., Jabbari, N., Mojarad, B., Vahhabi, A., Szafert, S., et al. (2020). Synergies in exosomes and autophagy pathways for cellular homeostasis and metastasis of tumor cells. Cell Biosci. 10:64. doi: 10.1186/s13578-020-00426-y

Scapoli, L., Girardi, A., Palmieri, A., Martinelli, M., Cura, F., Lauritano, D., et al. (2015). Quantitative analysis of periodontal pathogens in periodontitis and gingivitis. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 29(3 Suppl. 1), 101–110.

Schwimmer, E. (1877). Die idopathisches Schleimhaut-plaques der Mundhohle (leukoplakia buccalis). Arch. Dermatol. Syphilol. 9, 511–570.

Scully, C., and Bagan, J. (2009). Oral squamous cell carcinoma: overview of current understanding of aetiopathogenesis and clinical implications. Oral Dis. 15, 388–399. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2009.01563.x

Shapouri-Moghaddam, A., Mohammadian, S., Vazini, H., Taghadosi, M., Esmaeili, S. A., Mardani, F., et al. (2018). Macrophage plasticity, polarization, and function in health and disease. J. Cell. Physiol. 233, 6425–6440. doi: 10.1002/jcp.26429

Sheiham, A. (2001). Dietary effects on dental diseases. Public Health Nutr. 4, 569–591. doi: 10.1079/phn2001142

Shen, Z., Kuang, S., Zhang, Y., Yang, M., Qin, W., Shi, X., et al. (2020). Chitosan hydrogel incorporated with dental pulp stem cell-derived exosomes alleviates periodontitis in mice via a macrophage-dependent mechanism. Bioact. Mater. 5, 1113–1126. doi: 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2020.07.002

Shimoda, A., Ueda, K., Nishiumi, S., Murata-Kamiya, N., Mukai, S. A., Sawada, S., et al. (2016). Exosomes as nanocarriers for systemic delivery of the Helicobacter pylori virulence factor CagA. Sci. Rep. 6:18346. doi: 10.1038/srep18346

Siegel, G., Kluba, T., Hermanutz-Klein, U., Bieback, K., Northoff, H., and Schäfer, R. (2013). Phenotype, donor age and gender affect function of human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells. BMC Med. 11:146. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-146

Silva, N., Abusleme, L., Bravo, D., Dutzan, N., Garcia-Sesnich, J., Vernal, R., et al. (2015). Host response mechanisms in periodontal diseases. J. Appl. Oral Sci. Rev. FOB 23, 329–355. doi: 10.1590/1678-775720140259

Singh, P. P., LeMaire, C., Tan, J. C., Zeng, E., and Schorey, J. S. (2011). Exosomes released from M. tuberculosis infected cells can suppress IFN-γ mediated activation of naïve macrophages. PLoS One 6:e18564. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018564

Singh, P. P., Smith, V. L., Karakousis, P. C., and Schorey, J. S. (2012). Exosomes isolated from mycobacteria-infected mice or cultured macrophages can recruit and activate immune cells in vitro and in vivo. J. Immunol. 189, 777–785. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103638

Singhto, N., Kanlaya, R., Nilnumkhum, A., and Thongboonkerd, V. (2018). Roles of macrophage exosomes in immune response to calcium oxalate monohydrate crystals. Front. Immunol. 9:316. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00316

Smith, D. K., and Szuster, F. (2000). Aspects of tooth decay in recently arrived refugees. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 24, 623–626. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.2000.tb00529.x

Smith, J. A., and Daniel, R. (2016). Human vaginal fluid contains exosomes that have an inhibitory effect on an early step of the HIV-1 life cycle. AIDS 30, 2611–2616. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001236

Spiller, K. L., and Koh, T. J. (2017). Macrophage-based therapeutic strategies in regenerative medicine. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 122, 74–83. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2017.05.010

Ståhl, A.-L., Johansson, K., Mossberg, M., Kahn, R., and Karpman, D. (2019). Exosomes and microvesicles in normal physiology, pathophysiology, and renal diseases. Pediatr. Nephrol. 34, 11–30. doi: 10.1007/s00467-017-3816-z

Sun, Y., Shi, H., Yin, S., Ji, C., Zhang, X., Zhang, B., et al. (2018). Human mesenchymal stem cell derived exosomes alleviate type 2 diabetes mellitus by reversing peripheral insulin resistance and relieving beta-cell destruction. ACS Nano 12, 7613–7628. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.7b07643

Suzuki, N., Yoneda, M., Takeshita, T., Hirofuji, T., and Hanioka, T. (2019). Induction and inhibition of oral malodor. Mol. Oral Microbiol. 34, 85–96. doi: 10.1111/omi.12259

Szempruch, A. J., Sykes, S. E., Kieft, R., Dennison, L., Becker, A. C., Gartrell, A., et al. (2016). Extracellular vesicles from trypanosoma brucei mediate virulence factor transfer and cause host anemia. Cell 164, 246–257. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.11.051

Taba, M. Jr., Jin, Q., Sugai, J. V., and Giannobile, W. V. (2005). Current concepts in periodontal bioengineering. Orthod. Craniofac. Res. 8, 292–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-6343.2005.00352.x

Tahir, L., and Nazir, R. (2018). Dental Caries, Etiology, and Remedy Through Natural Resources. Dental Caries-Diagnosis, Prevention and Management. London: IntechOpen.

Takahashi, Y., Nishikawa, M., Shinotsuka, H., Matsui, Y., Ohara, S., Imai, T., et al. (2013). Visualization and in vivo tracking of the exosomes of murine melanoma B16-BL6 cells in mice after intravenous injection. J. Biotechnol. 165, 77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2013.03.013

Théry, C., Witwer, K. W., Aikawa, E., Alcaraz, M. J., Anderson, J. D., Andriantsitohaina, R., et al. (2018). Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles 2018 (MISEV2018): a position statement of the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles and update of the MISEV2014 guidelines. J. Extracell. Vesicles 7:1535750. doi: 10.1080/20013078.2018.1535750

Thorstensson, H., and Hugoson, A. (1993). Periodontal disease experience in adult long-duration insulin-dependent diabetics. J. Clin. Periodontol. 20, 352–358. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1993.tb00372.x

Tian, T., Wang, Y., Wang, H., Zhu, Z., and Xiao, Z. (2010). Visualizing of the cellular uptake and intracellular trafficking of exosomes by live-cell microscopy. J. Cell. Biochem. 111, 488–496. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22733

Trocoli Torrecilhas, A. C., Tonelli, R. R., Pavanelli, W. R., da Silva, J. S., Schumacher, R. I., de Souza, W., et al. (2009). Trypanosoma cruzi: parasite shed vesicles increase heart parasitism and generate an intense inflammatory response. Microbes Infect. 11, 29–39. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2008.10.003

Tschuschke, M., Kocherova, I., Bryja, A., Mozdziak, P., Angelova Volponi, A., Janowicz, K., et al. (2020). Inclusion biogenesis, methods of isolation and clinical application of human cellular exosomes. J. Clin. Med. 9:436. doi: 10.3390/jcm9020436

U.S. National Library of Medicine ClinicalTrials.gov (2021). U.S. National Library of Medicine ClinicalTrials.gov Database. Available online at: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ (accessed September, 2021).

Undale, A. H., Westendorf, J. J., Yaszemski, M. J., and Khosla, S. (eds.) (2009). “Mesenchymal stem cells for bone repair and metabolic bone diseases,” in Mayo Clinic Proceedings (Amsterdam: Elsevier). doi: 10.1016/S0025-6196(11)60506-5

van der Waal, I., Schepman, K. P., van der Meij, E. H., and Smeele, L. E. (1997). Oral leukoplakia: a clinicopathological review. Oral Oncol. 33, 291–301. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(97)00002-x

van Niel, G., Raposo, G., Candalh, C., Boussac, M., Hershberg, R., Cerf-Bensussan, N., et al. (2001). Intestinal epithelial cells secrete exosome-like vesicles. Gastroenterology 121, 337–349. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.26263

Vargas, A., Roux-Dalvai, F., Droit, A., and Lavoie, J. P. (2016). Neutrophil-Derived exosomes: a new mechanism contributing to airway smooth muscle remodeling. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 55, 450–461. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2016-0033OC

Wang, D., Zhang, H., Liang, J., Li, X., Feng, X., Wang, H., et al. (2013). Allogeneic mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in severe and refractory systemic lupus erythematosus: 4 years of experience. Cell Transplant. 22, 2267–2277. doi: 10.3727/096368911X582769c

Wang, L., Wang, J., Jin, Y., Gao, H., and Lin, X. (2014). Oral administration of all-trans retinoic acid suppresses experimental periodontitis by modulating the Th17/Treg imbalance. J. Periodontol. 85, 740–750. doi: 10.1902/jop.2013.130132

Wang, Y., Tian, J., Tang, X., Rui, K., Tian, X., Ma, J., et al. (2016). Exosomes released by granulocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells attenuate DSS-induced colitis in mice. Oncotarget 7, 15356–15368. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7324

Willms, E., Cabanas, C., Mager, I., Wood, M. J. A., and Vader, P. (2018). Extracellular vesicle heterogeneity: subpopulations, isolation techniques, and diverse functions in cancer progression. Front. Immunol. 9:738. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00738

Wynn, T. A., and Vannella, K. M. (2016). Macrophages in tissue repair, regeneration, and fibrosis. Immunity 44, 450–462. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.02.015

Xing, X., Han, S., Li, Z., and Li, Z. (2020). Emerging role of exosomes in craniofacial and dental applications. Theranostics 10, 8648–8664. doi: 10.7150/thno.48291

Xu, R., Greening, D. W., Zhu, H. J., Takahashi, N., and Simpson, R. J. (2016). Extracellular vesicle isolation and characterization: toward clinical application. J. Clin. Invest. 126, 1152–1162. doi: 10.1172/JCI81129

Yan, J. J., Su, I. J., Chen, P. F., Liu, C. C., Yu, C. K., and Wang, J. R. (2001). Complete genome analysis of enterovirus 71 isolated from an outbreak in Taiwan and rapid identification of enterovirus 71 and coxsackievirus A16 by RT-PCR. J. Med. Virol. 65, 331–339. doi: 10.1002/jmv.2038

Yanez-Mo, M., Siljander, P. R., Andreu, Z., Zavec, A. B., Borras, F. E., Buzas, E. I., et al. (2015). Biological properties of extracellular vesicles and their physiological functions. J. Extracell. Vesicles 4, 27066.

Yang, C., Chalasani, G., Ng, Y. H., and Robbins, P. D. (2012). Exosomes released from Mycoplasma infected tumor cells activate inhibitory B cells. PLoS One 7:e36138. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036138

Yang, J., Wu, J., Liu, Y., Huang, J., Lu, Z., Xie, L., et al. (2014). Porphyromonas gingivalis infection reduces regulatory T cells in infected atherosclerosis patients. PLoS One 9:e86599. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086599

Yu, B., Zhang, X., and Li, X. (2014). Exosomes derived from mesenchymal stem cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 15, 4142–4157.

Zappia, E., Casazza, S., Pedemonte, E., Benvenuto, F., Bonanni, I., Gerdoni, E., et al. (2005). Mesenchymal stem cells ameliorate experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis inducing T-cell anergy. Blood 106, 1755–1761. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1496

Zavatti, M., Beretti, F., Casciaro, F., Bertucci, E., and Maraldi, T. (2020). Comparison of the therapeutic effect of amniotic fluid stem cells and their exosomes on monoiodoacetate-induced animal model of osteoarthritis. Biofactors 46, 106–117. doi: 10.1002/biof.1576

Zhang, M. Z., Yao, B., Yang, S., Jiang, L., Wang, S., Fan, X., et al. (2012). CSF-1 signaling mediates recovery from acute kidney injury. J. Clin. Invest. 122, 4519–4532. doi: 10.1172/JCI60363

Zhang, W., Jiang, X., Bao, J., Wang, Y., Liu, H., and Tang, L. (2018). Exosomes in pathogen infections: a bridge to deliver molecules and link functions. Front. Immunol. 9:90. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00090

Zhang, X., Zhang, D., Jia, H., Feng, Q., Wang, D., Liang, D., et al. (2015). The oral and gut microbiomes are perturbed in rheumatoid arthritis and partly normalized after treatment. Nat. Med. 21, 895–905. doi: 10.1038/nm.3914

Zhang, Y., Liu, Y., Liu, H., and Tang, W. H. (2019). Exosomes: biogenesis, biologic function and clinical potential. Cell Biosci. 9:19. doi: 10.1186/s13578-019-0282-2

Zhankina, R., Baghban, N., Askarov, M., Saipiyeva, D., Ibragimov, A., Kadirova, B., et al. (2021). Mesenchymal stromal/stem cells and their exosomes for restoration of spermatogenesis in non-obstructive azoospermia: a systemic review. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 12, 1–12. doi: 10.1186/s13287-021-02295-9

Zhao, L., Zhou, Y., Xu, Y., Sun, Y., Li, L., and Chen, W. (2011). Effect of non-surgical periodontal therapy on the levels of Th17/Th1/Th2 cytokines and their transcription factors in Chinese chronic periodontitis patients. J. Clin. Periodontol. 38, 509–516. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2011.01712.x

Zheng, Y., Dong, C., Yang, J., Jin, Y., Zheng, W., Zhou, Q., et al. (2019). Exosomal microRNA-155-5p from PDLSCs regulated Th17/Treg balance by targeting sirtuin-1 in chronic periodontitis. J. Cell. Physiol. 234, 20662–20674. doi: 10.1002/jcp.28671

Zhuang, Z., Yoshizawa-Smith, S., Glowacki, A., Maltos, K., Pacheco, C., Shehabeldin, M., et al. (2019). Induction of M2 macrophages prevents bone loss in murine periodontitis models. J. Dent. Res. 98, 200–208. doi: 10.1177/0022034518805984

Keywords: exosomes, mesenchymal stromal/stem cells, dental infection controls, dentistry, orodental

Citation: Jafari N, Khoradmehr A, Moghiminasr R and Seyed Habashi M (2022) Mesenchymal Stromal/Stem Cells-Derived Exosomes as an Antimicrobial Weapon for Orodental Infections. Front. Microbiol. 12:795682. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.795682

Received: 15 October 2021; Accepted: 08 December 2021;

Published: 04 January 2022.

Edited by:

Nader Tanideh, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, IranReviewed by:

Jafar Rezaie, Urmia University of Medical Sciences, IranReza Shirazi, UNSW Sydney, Australia

Copyright © 2022 Jafari, Khoradmehr, Moghiminasr and Seyed Habashi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mina Seyed Habashi, bWluYS5zLmhhYmFzaGkuNjRAZ21haWwuY29t

Nazanin Jafari

Nazanin Jafari