95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Microbiol. , 09 December 2021

Sec. Food Microbiology

Volume 12 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2021.785351

This article is part of the Research Topic Biofilm and Food: Well- and Lesser-Known Interactions View all 6 articles

Enterococcus faecalis is considered a leading cause of hospital-acquired infections. Treatment of these infections has become a major challenge for clinicians because some E. faecalis strains are resistant to multiple clinically used antibiotics. Moreover, the presence of E. faecalis biofilms can make infections with E. faecalis more difficult to eradicate with current antibiotic therapies. Thus, our aim in this study was to investigate the effects of probiotic derivatives against E. faecalis biofilm formation. Bacillus subtilis natto is a probiotic strain isolated from Japanese fermented soybean foods, and its culture fluid potently inhibited adherence to Caco-2 cell monolayers, aggregation, and biofilm production without inhibiting the growth of E. faecalis. An apparent decrease in the thickness of E. faecalis biofilms was observed through confocal laser scanning microscopy. In addition, exopolysaccharide synthesis in E. faecalis biofilms was reduced by B. subtilis natto culture fluid treatment. Carbohydrate composition analysis also showed that carbohydrates in the E. faecalis cell envelope were restructured. Furthermore, transcriptome sequencing revealed that the culture fluid of B. subtilis natto downregulated the transcription of genes involved in the WalK/WalR two-component system, peptidoglycan biosynthesis and membrane glycolipid biosynthesis, which are all crucial for E. faecalis cell envelope synthesis and biofilm formation. Collectively, our work shows that some derivatives present in the culture fluid of B. subtilis natto may be useful for controlling E. faecalis biofilms.

Enterococci, which are Gram-positive bacteria normally present in human gastrointestinal tracts, are the second most common pathogens recovered from catheter-associated infections of the bloodstream and urinary tract and from skin and soft-tissue infections in hospitals in the United States (Paulsen et al., 2003; Arias and Murray, 2012). Among Enterococcus species, Enterococcus faecalis is the primary species responsible for human enterococcal infections (Sievert et al., 2013). Treatment of E. faecalis infections has become increasingly difficult because of the emergence of E. faecalis strains that are resistant to numerous clinically used antibiotics, such as macrolides; tetracyclines; aminoglycosides; and glycopeptides, including vancomycin, which was previously used as the antibiotic of last resort for enterococcal infections (Murray, 1997; Klevens et al., 2007; Arias et al., 2010; Frieden, 2013). Moreover, E. faecalis has a propensity to transfer antibiotic resistance genes to other bacteria within and across species via pheromone-inducible conjugative plasmid transfer, which facilitates the dissemination of antibiotic resistance (Clewell, 1990; Clewell et al., 2002).

In addition to having intrinsic resistance to multiple antibiotics and the ability to transfer antibiotic resistance via plasmid transfer, E. faecalis can readily form biofilms on a wide range of natural and artificial substrates, such as damaged heart valves, venous catheters, urinary catheters, and indwelling medical devices (Donlan and Costerton, 2002; Fernandez Guerrero et al., 2007). Biofilms are aggregates of microbes that accumulate at a solid-liquid interface and are encased in a self-produced matrix of extracellular polymeric substances (Flemming et al., 2007; Flemming and Wingender, 2010). Since the protective extracellular matrix can decrease the penetration of antibiotics, E. faecalis cells in biofilms can be 10 to 1,000 times more resistant to antibiotics than their planktonic counterparts (Hoyle and Costerton, 1991; Mah and O’Toole, 2001). This trait of enterococcal biofilms markedly reduces the effectiveness of current antibiotic treatments. In addition, enterococcal biofilms have been shown to serve as nidi for bacterial dissemination and as reservoirs for antibiotic resistance genes (Ch’ng et al., 2019). Taken together, the evidence indicates that the presence of E. faecalis biofilms can make infections with E. faecalis more difficult to eradicate. Therefore, there is a demand for novel, safe, and effective methods to inhibit the formation of E. faecalis biofilms.

In addition to discovering and developing new antibiotics, scientists have explored the possibility of preventing and treating gastrointestinal tract infections with probiotics, which are live microorganisms, such as bacteria and yeast, that can provide benefits to the host when administered in adequate amounts (Saarela et al., 2002; Kamada et al., 2013). The use of spore-forming bacteria, mostly of the genus Bacillus, as probiotics has attracted considerable attention from researchers in recent years (Elshaghabee et al., 2017). In comparison to commonly used non-spore-forming probiotic lactic acid bacteria, Bacillus species can form spores under harsh environments. This trait enables them to have higher acid tolerance and better stability during heat processing and low-temperature storage than other bacteria (Elshaghabee et al., 2017). In addition, previous studies (Piewngam et al., 2018; Tazehabadi et al., 2021) have shown that some Bacillus species possess the ability to inhibit the colonization and biofilm formation of pathogens via actions, such as interference with quorum-sensing signals, or production of antimicrobial agents, such as bacteriocin proteins. Piewngam et al. (2018) found that probiotic Bacillus subtilis can produce the lipopeptide fengycin for decolonization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in mouse feces and intestines via interference with S. aureus agr quorum-sensing signaling. Tazehabadi et al. (2021) found that two bacteriocin-producing Bacillus probiotic strains, B. subtilis KATMIRA1933 and Bacillus amyloliquefaciens B-1895, can inhibit the biofilm formation of several strains of the food-borne pathogen Salmonella enterica without killing planktonic S. enterica cells. Collectively, these studies support the idea that probiotic Bacillus species and their derivatives may have the potential to inhibit the biofilm formation ability of other pathogenic bacteria, such as E. faecalis.

B. subtilis natto is a probiotic strain isolated from natto, which is a traditional fermented soybean food in Japan with a long history of consumption (Nishito et al., 2010). In the process of steamed soybean fermentation, B. subtilis natto produces various derivatives, such as extracellular proteases, viscous substance γ-poly-DL-glutamic acid (γ-PGA), and antibiotics (Nishito et al., 2010; Katayama et al., 2021). Some B. subtilis natto derivatives may be useful to fight against E. faecalis. For example, we have shown in our previous studies that B. subtilis natto can secrete nattokinase mainly to degrade the peptide pheromone cCF10, thereby interfering with the transfer frequency of the antibiotic resistance plasmid pCF10 between E. faecalis bacteria (Lin et al., 2021). In this study, we further demonstrated the effects of B. subtilis natto supernatant on the biofilm formation ability of E. faecalis. In addition, we attempted to clarify the mechanisms by which B. subtilis natto supernatant affects the biofilm formation of E. faecalis using transcriptome sequencing (RNA-seq).

All bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Wild-type E. faecalis OG1RF and constructed E. faecalis OG1RF::p23cfp that expresses a constitutive CFP were obtained from the laboratory of Professor Gary M. Dunny (University of Minnesota, United States). All E. faecalis strains were statically cultured at 37°C in M9 medium [3g/L yeast extract, 10g/L casamino acids, 36g/L glucose, 0.12g/L MgSO4, and 0.011g/L CaCl2 (Bandyopadhyay et al., 2016)] or in brain heart infusion broth (BD Co., United States). If needed, the antibiotic rifampicin was added at a concentration of 200μg/ml (Bandyopadhyay et al., 2016).

Bacillus subtilis natto NTU-18 (BCRC 80390) isolated from a commercial product was maintained in our laboratory (Kuo et al., 2006; Kuo and Lee, 2008). B. subtilis natto was cultured in LB broth [10g/L tryptone, 5g/L yeast extract, and 10g/L sodium chloride (Atlas, 2010)] in orbital shakers at 37°C with shaking at 125rpm.

Bacillus subtilis natto supernatant was prepared using methods described in our previous study (Lin et al., 2021). In brief, overnight cultures of B. subtilis natto were diluted 1:100 in M9B medium (8.5g/L Na2HPO4·2H2O, 3g/L KH2PO4, 11.5g/L sodium acetate, and 1ml/L acetic acid were added as buffering agents to the original M9 medium) and cultured aerobically in orbital shakers at 37°C with shaking at 125rpm. After 24h of cultivation, the cultures were centrifuged (4,000×g, 10min) to remove all cells. Then, the supernatant was filter-sterilized through 0.22-μm filters (Pall Co., United States) and stored at 4°C.

Caco-2, a colon adenocarcinoma cell line, was purchased from the Bioresource Collection and Research Center (BCRC, Taiwan). The cells were routinely maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM containing 4.5g/L glucose; GeneDireX Inc., Taiwan) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco, United States) and 1x penicillin-streptomycin-glutamine (GeneDireX Inc., Taiwan) and incubated at 37°C in a 95% humidity and 5% CO2 air atmosphere. The cells were passaged every 5–6days in 10cm2 cell culture dishes.

An in vitro bacterial adhesion assay was performed as described by Letourneau et al. with some modifications (Letourneau et al., 2011). To prepare monolayers of Caco-2 cells for the in vitro bacterial adhesion assay, one milliliter of cell suspension (2×105 cells/ml) was seeded in three sets of duplicate wells (one for each treatment) of a 24-well plate, and the plate was incubated in a cell culture incubator until the cells were fully confluent. The cells were then washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and the culture medium was replaced with 900μl of antibiotic-free DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS; then, 100μl of B. subtilis natto supernatant or M9B medium was added.

Overnight cultures of E. faecalis cells were centrifuged, washed twice with PBS containing 2mm EDTA, and resuspended in DMEM with 10% FBS. A volume of bacterial culture corresponding to 106 E. faecalis cells was used to inoculate Caco-2 cells. The same volume of E. faecalis culture was also added to a medium mixture (90% DMEM containing 10% FBS; 10% M9B medium) without Caco-2 cells to determine the total number of bacterial cells in the inoculum. The E. faecalis and Caco-2 cells were then cocultured at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 3h. After 3h of incubation, the culture medium was removed, and the infected Caco-2 cells were washed 3 times with PBS. All cells were then detached with 0.05% trypsin-EDTA for 20min at 37°C. Then, serial dilutions of these samples were plated on selective Todd Hewitt broth agar medium containing 30g/L Bacto Todd Hewitt Broth (Neogen Cor., United States), 15g/L agar and 50μg/ml rifampicin, and the adherent E. faecalis cells were counted.

An autoaggregation assay was performed as described by Baccouri et al. and Kaur et al. with some modifications (Kaur et al., 2018; Baccouri et al., 2019). Overnight cultures of E. faecalis OG1RF were diluted 1:100 in M9B medium with or without B. subtilis natto supernatant treatment (0, 10, and 50% v/v) and grown in culture tubes with screw caps and rubber liners (Kimble Inc., United States). All culture tubes were incubated anaerobically at 37°C for 24h. After 24h of cultivation, treated and untreated E. faecalis cultures were centrifuged, washed twice with PBS, and resuspended in PBS to give final OD600 of 1. The E. faecalis suspensions were vortexed for 15s and then incubated at 37°C for 4h. After 0 and 4h of incubation without mixing, one milliliter of the suspension from the top of the tube was taken to measure the absorbance (A) at 600nm. Autoaggregation was then calculated as follows: autoaggregation (%)=[1−(A4h/A0)×100].

Overnight cultures of E. faecalis OG1RF were diluted 1:100 in a 24-well plate containing 1ml of medium and sterile cover glasses and anaerobically cultured at 37°C for 24 or 48h. The biomass that adhered to the cover glass was prefixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde and 2.5% paraformaldehyde in 0.05M cacodylate at 25°C for 60min.

After prefixation, the samples were washed three times with 0.05M cacodylate and then postfixed with 1% osmium tetroxide in 0.05M cacodylate at 25°C for 60min. The fixed samples were chemically dehydrated using a graded ethanol series [30, 50, 70, 85, 90, 95, and 100% (two times)] and processed in a CO2-based critical point dryer and ion coater. The dried samples were observed using an FEI Inspect S scanning electron microscope at a high voltage of 15kV and a magnification of 3,000×.

A ninety-six-well polystyrene plate-based bacterial biofilm formation assay was performed as described by Dale et al. with some modifications (Dale et al., 2015). In brief, overnight cultures of E. faecalis were diluted 1:100 in M9B medium containing 10% B. subtilis natto supernatant or not, and 100μl was dispensed into 8 wells per treatment. In addition, Oxyrase® for Broth (Oxyrase Inc., United States) was added to the cultures to generate anaerobic conditions. The 96-well plates were then incubated in the chamber of a SpectraMax® 190 microplate reader (Molecular Devices, LLC, United States) at 37°C for 24h. The OD600 was measured every 2h to monitor cell growth. After 24h of cultivation, the culture medium was removed, and the biomass in the bottom of the 96-well plates was washed three times with double-distilled water (ddH2O) and then air-dried for 2.5h. Next, the biomass was stained with 0.1% safranin solution for 20min, washed five times with ddH2O, and air-dried. The safranin-stained biomass was quantified by measuring the OD450 value. Biofilm formation is expressed as an index of the biomass stained with safranin (OD450 value) normalized to the cell growth (OD600 value at 24h). The relative biofilm biomass values were calculated by further normalizing the biofilm index values of the treated group to those of the negative control group to which no B. subtilis natto supernatant was added.

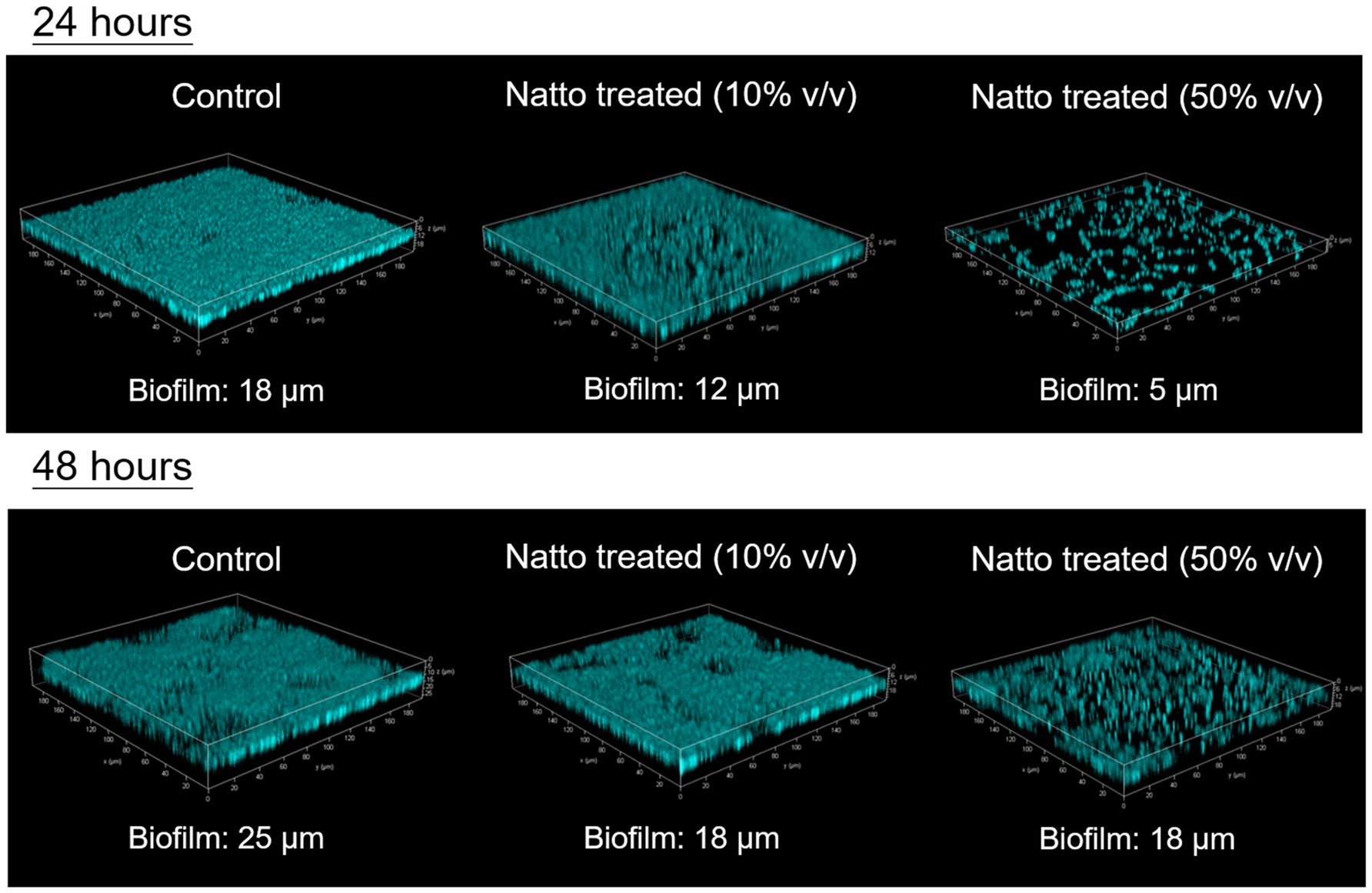

Overnight cultures of E. faecalis OG1RF::p23cfp were diluted 1:100 in M9B medium with or without B. subtilis natto supernatant treatment (0, 10, and 50% v/v) and cultured on glass coverslips in 35×12mm tissue culture dishes (Alpha Plus Scientific Co., Taiwan). All dishes were incubated anaerobically at 37°C for 24 or 48h. After 24 or 48h of cultivation, the culture medium in the tissue culture dishes was removed, and the biomass attached to the glass coverslips in the tissue culture dishes was washed twice with PBS to remove unattached cells and then fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde (PFA). Fixation with 2% PFA in PBS was performed at 4°C for 10min. After fixation, the biomass attached to the glass coverslip in the bottom of each petri dish was visualized using a white light laser confocal microscope Leica TCS SP8 X (Leica Microsystems, Ltd., Germany) and analyzed using Leica Application Suite X software.

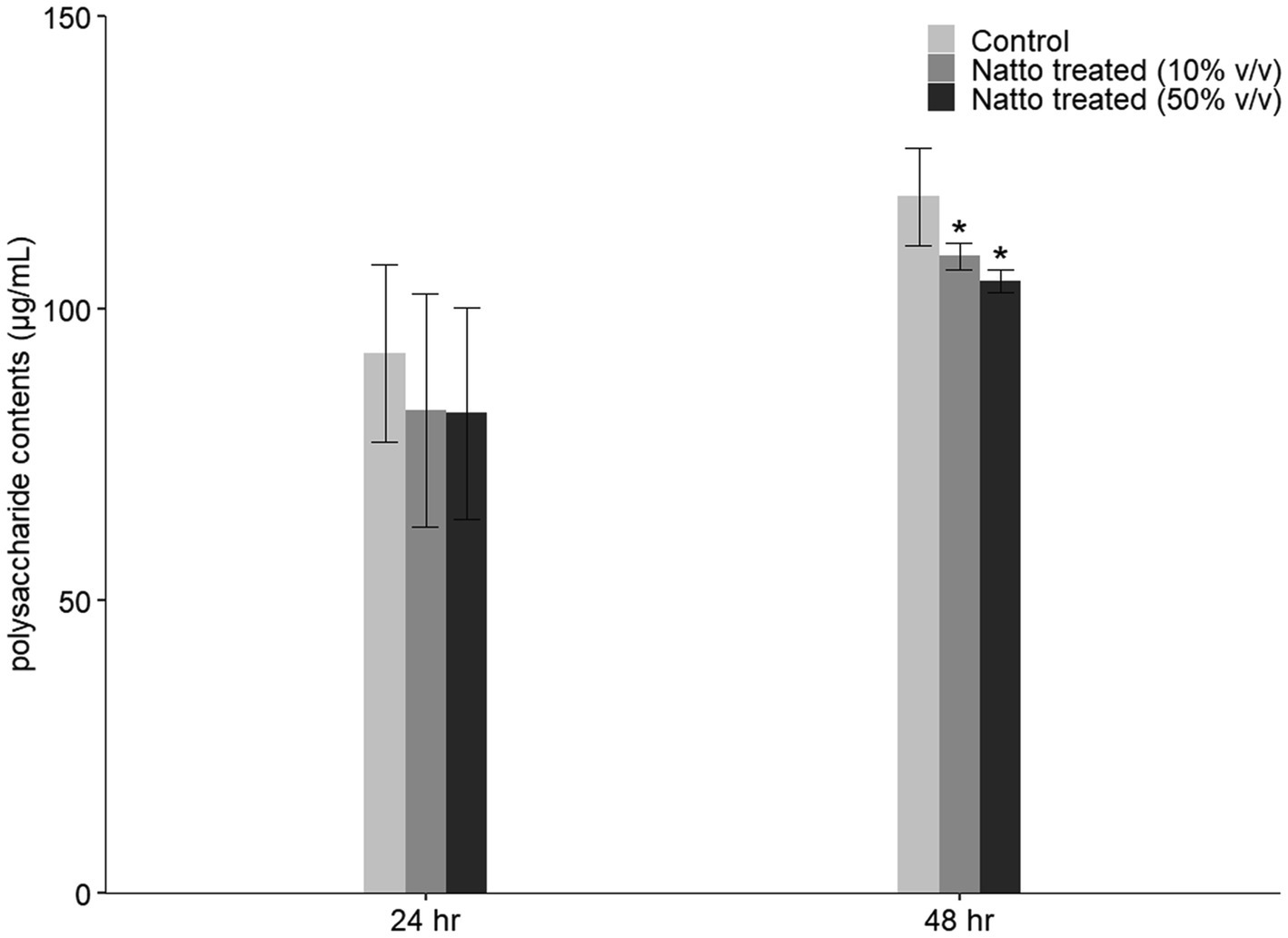

The extraction and analysis of E. faecalis biofilm polysaccharides were conducted using the method described by Liu et al. (2020a, 2020b) with some modifications. Overnight cultures of E. faecalis were diluted 1:100 in M9B broth with or without B. subtilis natto supernatant (0, 10%, or 50% v/v). One milliliter of diluted E. faecalis culture was added to 24-well plates and incubated anaerobically at 37°C. After 24 or 48h of cultivation, the culture supernatant was removed, and the biomass that adhered onto the bottom of each well was washed with ddH2O and then air-dried for 1h. Next, the adhered biomass was harvested by scraping the surface thoroughly with a sterile polyester-tipped swab after 1ml of PBS was added into each well. The cell suspensions of two wells corresponding to the same treatment were mixed together and centrifuged at 5,000×g for 30min at 4°C. The concentrated precipitates were resuspended in aqueous solution (2ml) containing 0.85% NaCl and 0.22% formaldehyde, and the E. faecalis biofilm polysaccharide was extracted at 80°C for 30min. The polysaccharide dissolved in the formaldehyde solution was recovered further via centrifugation at 15,000×g and 4°C for 30min. The polysaccharide concentrations were quantified using the phenol-sulfuric acid (PSA) method (Dubois et al., 1951). In brief, 100μl of polysaccharide solutions or standard (D-glucose solution) was mixed equally with 5% (w/w) phenol solution in microcentrifuge tubes. Immediately afterward, 1ml of concentrated sulfuric acid was added. The tubes were then incubated for 5min at room temperature, and 200μl of the reaction mixture was added to a 96-well plate. The absorbance was measured at 492nm using a Multiskan FC microplate photometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., United States).

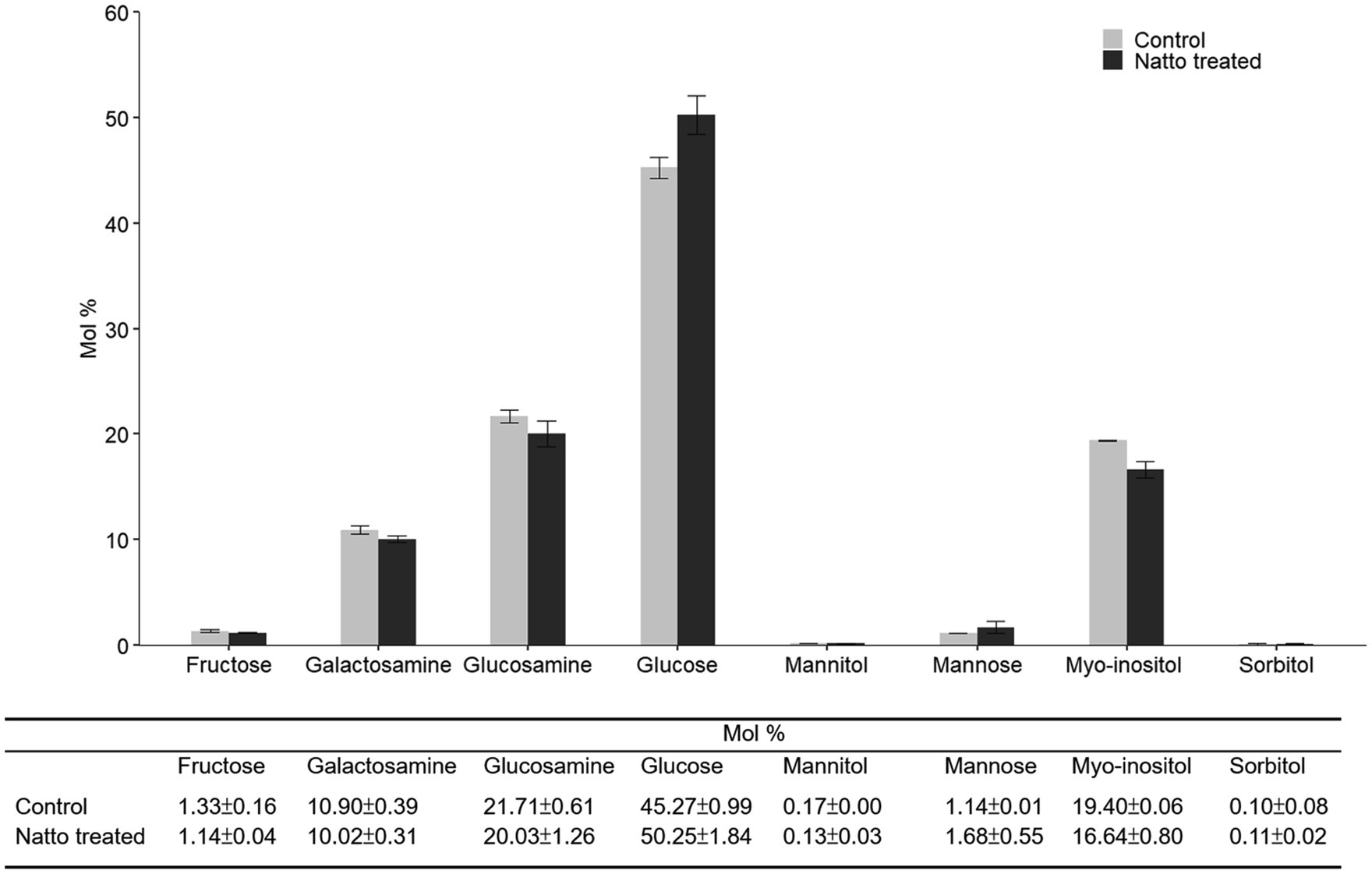

Enterococcus faecalis cell envelope polysaccharides were prepared using the method described by Dale et al. (2015, 2017) with some modifications. In brief, overnight cultures of E. faecalis were diluted 1:100 in M9B broth without and with B. subtilis natto supernatant (0 and 10% v/v) and cultured anaerobically. After 24h of incubation, E. faecalis cells were collected by centrifugation, and pelleted cells were washed using sucrose solution [25% sucrose and 10mm Tris-HCl (pH 8)]. Cells were then resuspended in sucrose solution supplemented with lysozyme and mutanolysin and incubated overnight at 37°C with gentle agitation. Next, supernatant fractions were harvested by centrifugation, followed by treatment with RNase A, DNase to remove contaminating nucleic acids, and proteinase K to remove protein impurities. The remaining impurities in the supernatant fraction were further extracted with chloroform. The aqueous phase was transferred to a new tube, and polysaccharides were precipitated by the addition of ethanol to a final concentration of 75% and incubation at −80°C for 30min. Precipitated polysaccharides were washed with 75% ethanol and allowed to air dry.

The carbohydrate composition of E. faecalis cell envelope polysaccharides was analyzed following complete acid hydrolysis of the polysaccharides. Acid hydrolysis of E. faecalis cell envelope polysaccharides was carried out with 1.95N trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) at 80°C for 6h. The mixture was cooled, evaporated, and then resuspended in Milli-Q water. Monosaccharides were analyzed on an HPAEC system (Dionex BioLC) equipped with a gradient pump, a pulsed amperometric detector (PAD) using a gold working electrode, and an anion – exchange column (Carbopac PA −10, 4.6×250mm). The detection condition was an isocratic NaOH concentration of 18mm at ambient temperature. The flow rate was 1.0ml/min. Identification and quantification of the monosaccharides were carried out in comparison with established standards. Data were collected and integrated on a PRIME DAK system (HPLC Technology, Ltd., United Kingdom).

Overnight culture of E. faecalis OG1RF was diluted 1:100 in M9B medium with or without B. subtilis natto supernatant treatment and incubated anaerobically at 37°C for 24h. After 24h of cultivation, 600μl of bacterial culture was treated with 1,200μl of RNAprotect Bacteria Reagent (Qiagen Ltd., Germany) at room temperature for 5min. The cells were then collected by centrifugation for 10min at 4°C, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until RNA extraction. For RNA extraction, cells were lysed with lysozyme (30mg/ml) and mutanolysin (500U/ml) in Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer at 37°C for 10min (Bandyopadhyay et al., 2016; Manias and Dunny, 2018). Total RNA was then extracted using an RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen Ltd., Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Five micrograms of total RNA was subjected to DNase treatment with Turbo DNase (Ambion Co., United States) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The RNA purity and concentration were measured using an ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Inc., United States), and RNA integrity was validated using a Bioanalyzer 2,100 (Agilent Technologies, Inc., United States). Then, ribosomal RNA was removed using a RiboMinus™ Transcriptome Isolation Kit (Invitrogen Co., United States). The cDNA library was constructed with purified mRNA with a SureSelect Strand Specific RNA Library Preparation Kit (Agilent Technologies, Inc., United States) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA-seq using the Illumina NovaSeq 6,000 (paired end) platform was performed at Welgene Biotech (Taiwan).

The raw image data were converted to sequence data using bcl2fastq conversion software v2.20. After adaptor clipping and sequence quality trimming with Trimmomatic v0.36, the clean reads of the control and treated groups were mapped to the reference genome of the WT strain E. faecalis OG1RF (NC_017316.1) using HISAT2.

Differential expression analysis was performed using cuffdiff (cufflinks v2.2.1) with genome bias detection/correction and Welgene Biotech’s in-house pipeline. Genes with a value of p≤0.05 and an FC≥2 were considered significantly differentially expressed. Functional enrichment assays of the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in each experiment were performed using clusterProfiler v3.6.

The RNA-seq data discussed in this study have been deposited in NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus database (Edgar et al., 2002; Barrett et al., 2013) and are accessible at GEO series accession number GSE184249.1

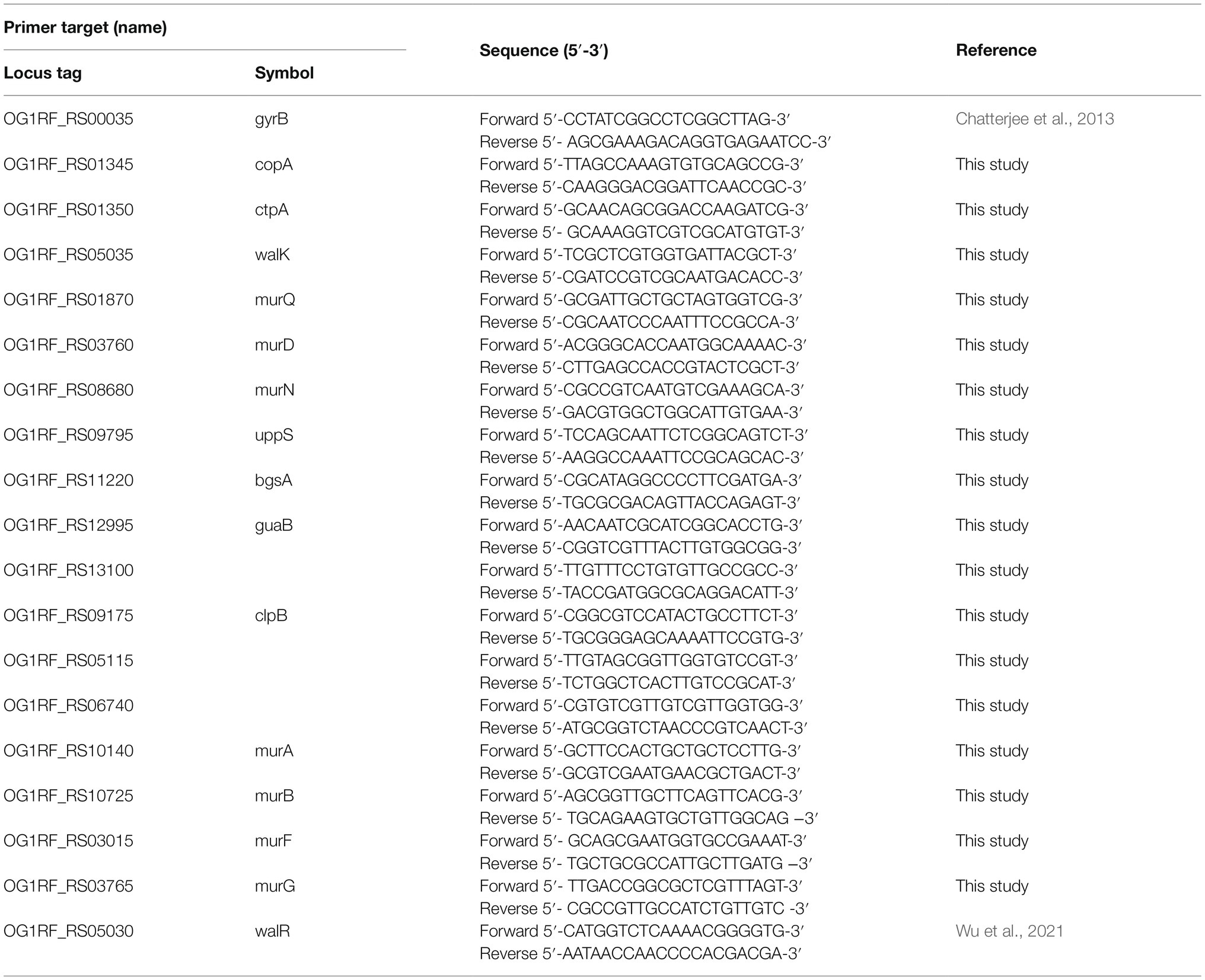

Total RNA was prepared according to the methods above. Approximately 500ng of total RNA was used to synthesize cDNA with a Quant II Fast RT kit (BIOTOOLS Co., Ltd., Taiwan). Each reaction product was diluted 1:20 in ddH2O, and 1μl was then used for quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) using SYBR® Green Supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., United States) and a Bio-Rad CFX384 instrument (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., United States). A total reaction volume of 10μl containing 2μl of gene-specific primer mixture at a concentration of 2μm was used in each well. Each reaction was performed in triplicate, and the threshold cycle (CT) values were obtained. Relative quantification was performed using the 2-ΔΔCT method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). Gene expression was normalized to that of the housekeeping gene gyrB, which is moderately expressed (Chatterjee et al., 2013). The sequences of the primers are listed in Table 2. Three biological replicates were performed to show repeatability.

Table 2. Sequence of the primers used for quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR).

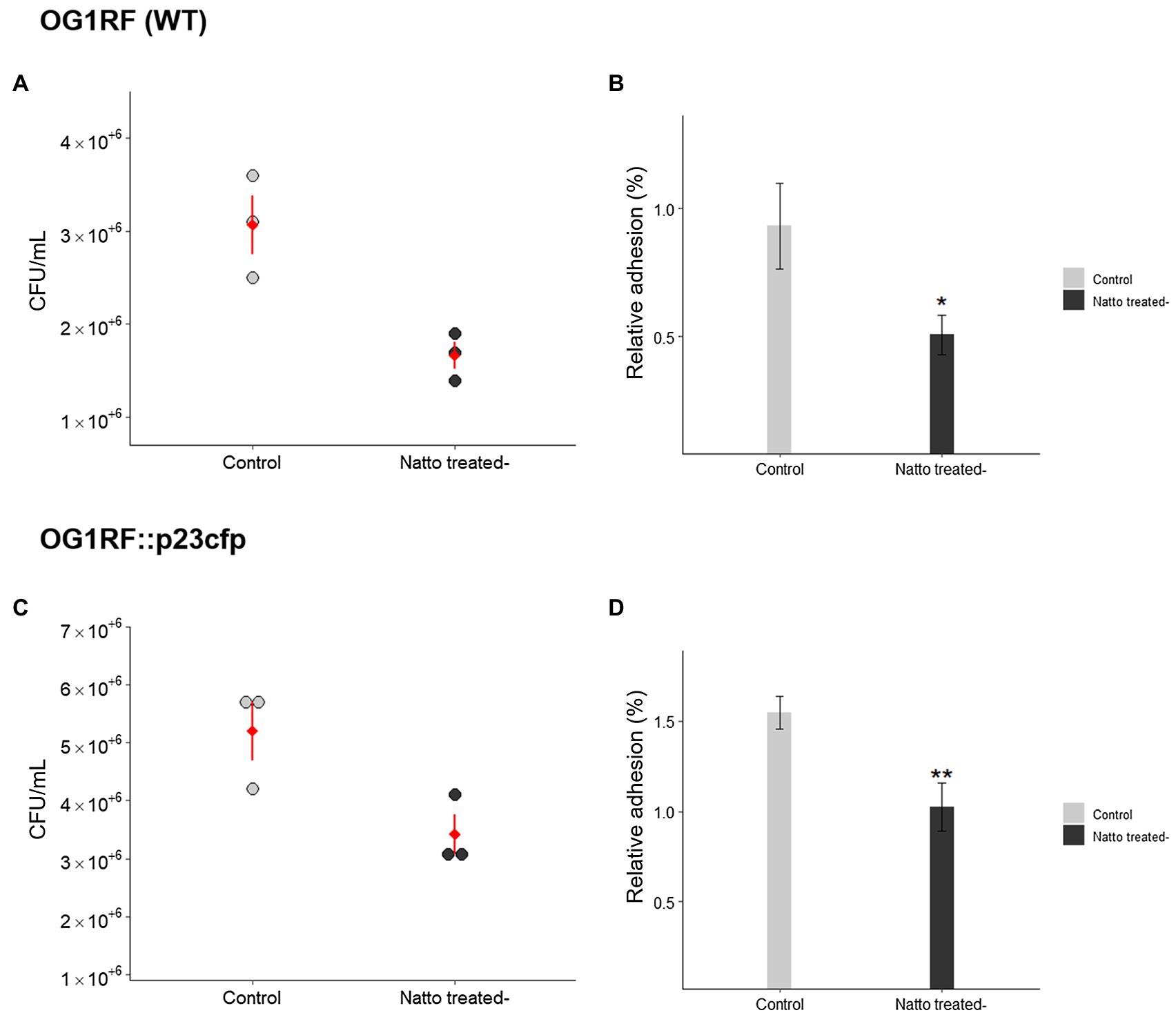

Bacterial adhesion to and subsequent colonization of host tissues are key steps in the initial stage of biofilm formation (Baldassarri et al., 2001; Monte et al., 2014). To test our hypothesis that B. subtilis natto supernatant would interfere with E. faecalis biofilm formation, we first investigated whether the ability of E. faecalis to adhere onto the human intestinal epithelial cell line Caco-2 was inhibited by B. subtilis natto supernatant treatment. A certain number of E. faecalis cells were added to Caco-2 monolayer cultures in the presence or absence of B. subtilis natto supernatant. After 3h of cocultivation, the E. faecalis cells adhered to the Caco-2 cell monolayers were detached and quantified via plating of the entire cultures on selective medium. As shown in Figures 1A,C, the concentrations [colony-forming units (CFU)/ml] of adhered E. faecalis cells [both wild-type (WT) and cyan fluorescent protein (CFP)-expressing strains] decreased markedly due to B. subtilis natto supernatant treatment. The relative adhesion of E. faecalis OG1RF (WT) cells decreased from 1.55 to 1.02%; the relative adhesion of E. faecalis OG1RF::p23cfp cells decreased from 0.93 to 0.51% (Figures 1B,D). These results indicated that B. subtilis natto supernatant likely interferes with the ability of E. faecalis to adhere to host tissues, such as the human intestinal tract.

Figure 1. Bacillus subtilis natto supernatant affects the adhesion of Enterococcus faecalis cells into human intestinal Caco-2 cell monolayers. The concentrations (A,C) (CFU/ml) and relative adhesion(%) (B,D) of E. faecalis OG1RF (WT) and OG1RF::p23cfp cells to Caco-2 cell monolayers after 3h in an in vitro bacterial adhesion assay with or without B. subtilis natto supernatant treatment (10%, v/v). In (A) and (C), each dot in the figures represents a replicate, and the red diamonds with red lines indicate the means±SDs (n=3). In (B) and (D), the data are presented as the means±SDs (n=3). *p<0.05 and **p<0.01 compared with each negative control group (Student’s t-test).

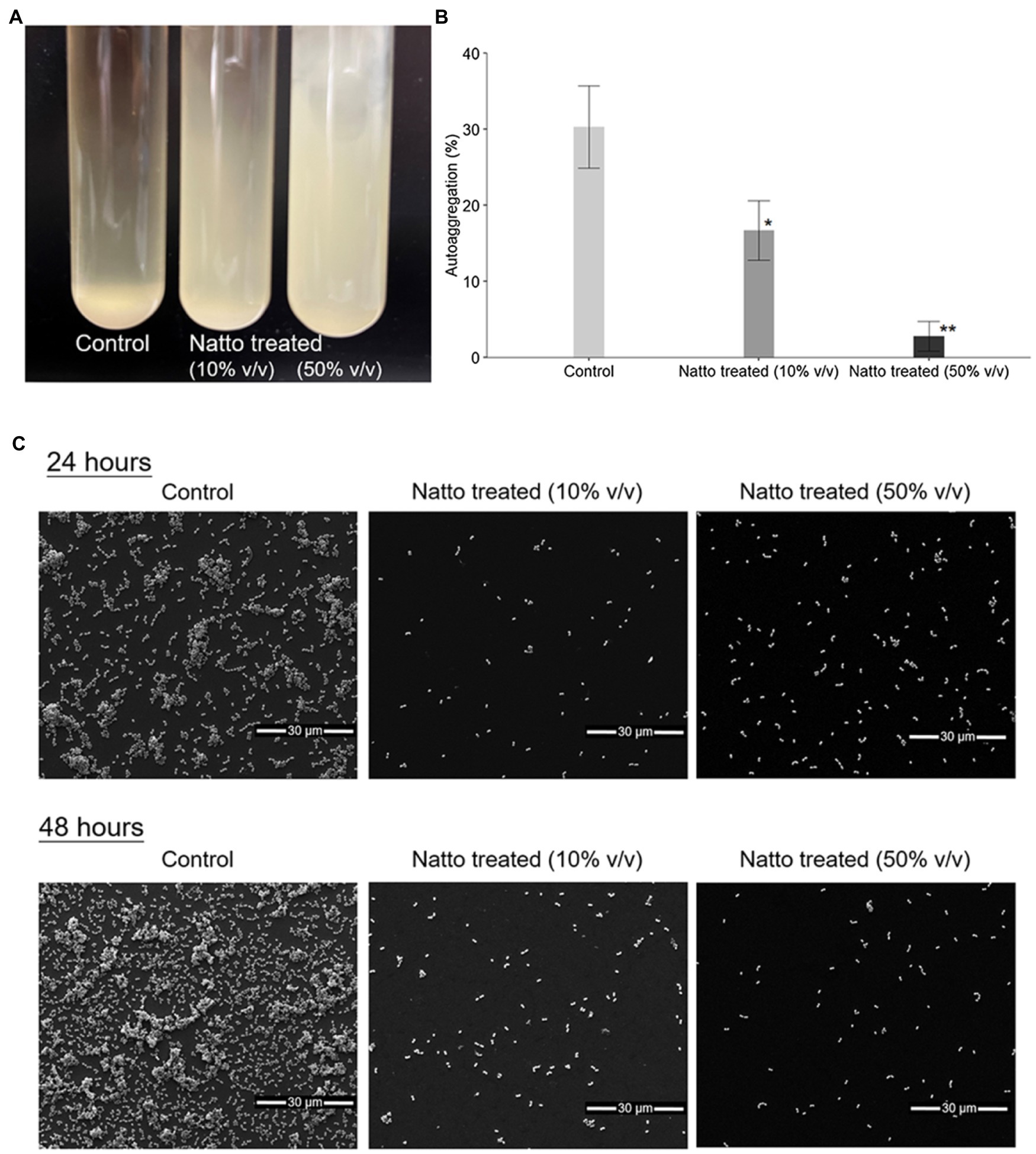

Previous studies (Kragh et al., 2016) have shown that bacterial cells tend to clump together in multicellular aggregates before they form biofilms. Herein, we investigated whether B. subtilis natto supernatant affects the formation of E. faecalis aggregates. Overnight cultures of E. faecalis were diluted in M9B medium in the presence or absence of the B. subtilis natto supernatant and incubated under anaerobic conditions. After 24h of cultivation without mixing, both 10 and 50% (v/v) B. subtilis natto supernatant-treated E. faecalis cultures remained turbid, whereas control (untreated) cultures settled at the bottom of the tube (Figure 2A). Treated and untreated E. faecalis cells were collected and used in 4-h autoaggregation assay. As shown in Figure 2B, percentage autoaggregation of both 10 and 50% (v/v) B. subtilis natto supernatant-treated E. faecalis was significantly lower than that of untreated E. faecalis (control group; 10%: p<0.05; 50%: p<0.01). In addition, the aggregates of E. faecalis cells formed on glass coverslips with or without B. subtilis natto supernatant were observed and analyzed using scanning electron microscopy (SEM). As shown in Figure 2C, E. faecalis cells in the control group formed dense aggregates after 24h of cultivation. However, the dense aggregation of E. faecalis cells was markedly reduced upon treatment with 10 and 50% v/v B. subtilis natto supernatant. Even though E. faecalis grew for 48h, no large cell clumps were observed in the B. subtilis natto supernatant-treated groups. Collectively, these results indicated that B. subtilis natto supernatant might inhibit E. faecalis autoaggregation, thus affecting biofilm initiation and development.

Figure 2. Bacillus subtilis natto supernatant inhibits E. faecalis autoaggregation. (A) Macroscopic analysis of untreated (control) and B. subtilis natto supernatant-treated (10 and 50% v/v) E. faecalis cultures after 24h of cultivation. (B) Percentage autoaggregation exhibited by untreated (control) and B. subtilis natto supernatant-treated (10 and 50% v/v) E. faecalis. The data are presented as the means±SDs (n=3). Values with asterisks (*) were significantly different compared with the negative control (untreated) group according to Duncan’s multiple range tests (*p<0.05; **p<0.01). (C) SEM images of E. faecalis aggregates.

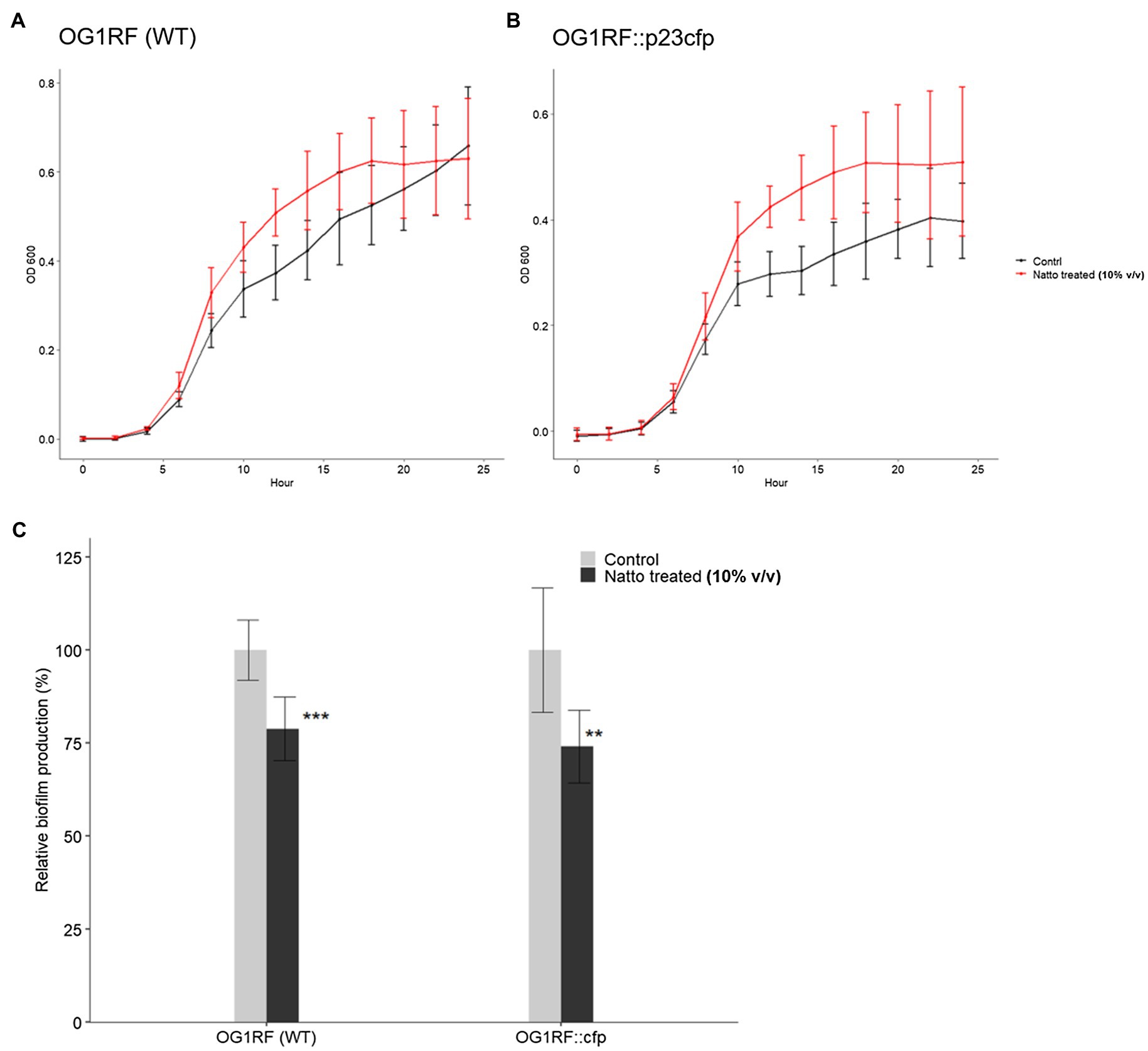

Ninety-six-well polystyrene plate-based biofilm assays devised by Dale et al. (2015) were performed here to investigate the effect of B. subtilis natto supernatant on E. faecalis biofilm growth over 24h. Overnight cultures of E. faecalis were diluted in M9B medium in the presence or absence of the B. subtilis natto supernatant (10% v/v) and incubated under anaerobic conditions for 24h. The optical density at 600nm (OD600) values of the E. faecalis cultures were measured every 2h to monitor the growth status of E. faecalis within 24h. After 24h of cultivation, the biomass that adhered to the bottom of the 96-well plates was washed, dried, and stained with safranin. Biofilm production was expressed as an index of the biomass stained with safranin [optical density at 450nm (OD450) value] normalized to the cell growth (OD600 value at 24h). As shown in Figures 3A,B, the OD600 values of treated E. faecalis cultures were higher than those of untreated E. faecalis cultures when E. faecalis grew to the exponential growth phase. These results indicated that B. subtilis natto supernatant might slightly promote rather than inhibit the growth of E. faecalis in 24h. However, the biofilm growth of E. faecalis at 24h was significantly inhibited by B. subtilis natto supernatant treatment. The relative biofilm production rates (%) of WT and CFP-expressing E. faecalis OG1RF strains decreased by 21.18 and 26.99%, respectively (Figure 3C). These results showed that B. subtilis natto supernatant could inhibit E. faecalis biofilm production without killing planktonic E. faecalis cells.

Figure 3. Bacillus subtilis natto supernatant interferes with E. faecalis biofilm production but not growth. (A,B) Growth curves of E. faecalis OG1RF WT and OG1RF::p23cfp in the absence or presence of B. subtilis natto supernatant (10% v/v) for 24h. In (A) and (B), the Y axis shows the OD600 values of the bacterial cultures at different time points. The data are presented as the means±SDs (n=8). (C) Biofilm production in the absence or presence of B. subtilis natto supernatant (10% v/v) for 24h. Biofilm production is expressed as an index of the biomass stained with safranin (OD450 value) normalized to the cell growth (OD600 value at 24h). Relative biofilm production (%) was calculated by further normalizing the biofilm index values of the treated group to those of the negative control group to which no B. subtilis natto supernatant was added. The data are presented as the means±SDs (n=8). **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001 compared with each negative control group (Student’s t-test).

The difference between the B. subtilis natto supernatant-treated and untreated groups seemed to be more significant in SEM images (Figure 2C) than in the biofilm formation assay (Figure 3C). In SEM experiments, E. faecalis cells attached to glass coverslips that had no coating, whereas E. faecalis cells in the biofilm formation assay attached to the tissue culture-treated bottom of a 96 well polystyrene plate. We found that E. faecalis cells had relatively difficulty attaching to noncoating abiotic surfaces, such as glass coverslips. Furthermore, some E. faecalis cells or clumps that attached to glass coverslips may be removed due to multistep sample pretreatment before SEM observations. Therefore, we inferred that these factors might contribute to the deviation between the results of the SEM experiment and the 96-well plate-based biofilm formation assay (Figures 2C, 3C, respectively).

The 3D architecture of the biofilms of the CFP- expressing strain E. faecalis OG1RF::p23cfp that formed on the glass coverslips at the bottom of the tissue culture dishes with or without B. subtilis natto supernatant was visualized and analyzed using confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM). The results are shown in Figure 4. After 24h of cultivation, the E. faecalis in the control group formed dense and well-organized biofilms, whereas the E. faecalis in both B. subtilis natto supernatant-treated groups formed loose and even disorganized biofilms, especially those in the group with high-dose B. subtilis natto supernatant (50% v/v) treatment. In addition, the biofilms of both 10 and 50% (v/v) B. subtilis natto supernatant-treated E. faecalis were thinner (at almost 12 and 5μm, respectively) than the E. faecalis biofilm in the control group, which was 18μm thick. Although all the control and B. subtilis natto supernatant-treated biofilms grew thicker from 24 to 48h, the inhibitory effect of B. subtilis natto supernatant on E. faecalis biofilms still existed (approximate biofilm thickness: 25μm in the control group, 18μm in both treated groups). The CLSM results were consistent with the results shown by biofilm assays conducted in 96-well polystyrene plates. Taken together, these results indicated that B. subtilis natto supernatant interfered with E. faecalis biofilm growth and resulted in the formation of looser and thinner biofilms.

Figure 4. 3D architecture of E. faecalis OG1RF::p23cfp biofilms with or without B. subtilis natto supernatant. The CFP-expressing strain E. faecalis OG1RF::p23cfp was cultured anaerobically in M9B medium without or with B. subtilis natto supernatant (0, 10, or 50% v/v) on glass coverslips in tissue culture dishes. After 24 or 48h of cultivation, the biofilms that formed on the bottom of the culture dishes were washed, fixed, and then analyzed using CLSM. The approximate biofilm thicknesses (μm) for all groups were measured and are shown in the figure.

We found that E. faecalis cells can easily and effectively attach to the bottom of tissue culture-treated plates or dishes and form biofilms. Therefore, in the 96-well plate-based biofilm formation assay, we hypothesized that approximately the same number of E. faecalis cells attached to the tissue culture-treated surface in the presence or absence of B. subtilis natto supernatant. The results in Figure 3C show that E. faecalis biofilm production was inhibited by B. subtilis natto supernatant treatment. In addition, the E. faecalis biofilms in the B. subtilis natto supernatant-treated groups were thinner than those in the control (untreated) groups under CLSM (Figure 4). However, B. subtilis natto supernatant did not inhibit the growth of E. faecalis (Figures 3A,B). Based on these observations, we inferred that the secretion of extracellular polymeric substances (EPSs) in E. faecalis biofilms might be changed. When bacteria adhere to a solid surface, they continue to grow and secrete EPS, which comprises polysaccharides, proteins, nucleic acids, and fatty acids (Liu et al., 2020a,b). EPS plays a key role in forming the three-dimensional architecture of biofilms. As reported previously, EPS in most biofilms accounts for more than 90% of the dry mass (Flemming and Wingender, 2010). Furthermore, polysaccharides are the major components of EPS (Flemming and Wingender, 2010). Herein, we investigated whether the polysaccharide contents of E. faecalis biofilms were reduced. The quantification results in Figure 5 show that the polysaccharide contents of E. faecalis biofilms indeed decreased in both the 10 and 50% (v/v) B. subtilis natto supernatant-treated groups after 24h of cultivation. When E. faecalis grew for 24 to 48h, the biofilm exopolysaccharide contents in all the control and treated groups increased. However, the polysaccharide contents in both the 10 and 50% (v/v) B. subtilis natto supernatant-treated groups were significantly lower than those in the control groups. Thus, B. subtilis natto supernatant likely inhibited E. faecalis biofilm polysaccharide production.

Figure 5. Inhibitory effect of B. subtilis natto supernatant on E. faecalis biofilm polysaccharide production. E. faecalis OG1RF was anaerobically cultured in M9B broth without or with B. subtilis natto supernatant (0, 10, and 50% v/v) for 24 or 48h. The polysaccharide contents obtained from E. faecalis biofilms were determined using the PSA method. The data are presented as the means±SDs (n=3). Values with asterisks (*) were significantly different compared with each negative control group according to Duncan’s multiple range tests (*p<0.05).

Previous studies (Haussler et al., 2003; Kragh et al., 2016) have reported that greater cell surface “stickiness” may increase the tendency of bacterial cells to form aggregates and attach to a solid surface, thus increasing biofilm formation. The properties of the bacterial cell surface, including stickiness, may be associated with the composition and organization of the bacterial cell envelope, which comprises the inner cell membrane and the cell wall (Sengupta et al., 2013; Choi et al., 2015). Here, we investigated whether the carbohydrate composition of the E. faecalis cell envelope was impacted by B. subtilis natto supernatant treatment (10% v/v, 24h) using high-performance anion-exchange chromatography (HPAEC). As shown in Figure 6, several types of monosaccharides, including glucose, glucosamine, and galactosamine, were detected in the E. faecalis cell envelope. Glucose, which accounted for approximately 45mol % of all monosaccharides in the E. faecalis cell envelope, was the most abundant monosaccharide. Upon treatment with B. subtilis natto supernatant, the content of glucose increased by approximately 5mol %, whereas the content of other monosaccharides decreased. Restructuring of the monosaccharide composition in the cell envelope can likely result in changes in cell surface properties, thus affecting the biofilm formation ability of E. faecalis.

Figure 6. Carbohydrate composition of purified polysaccharides obtained from the E. faecalis cell envelope. E. faecalis OG1RF was anaerobically cultured in M9B broth without or with B. subtilis natto supernatant (0 and 10v/v) for 24h. The polysaccharides in the E. faecalis OG1RF cell envelope were purified for carbohydrate composition analysis using HPAEC. The data are presented as the means±SDs (n=3).

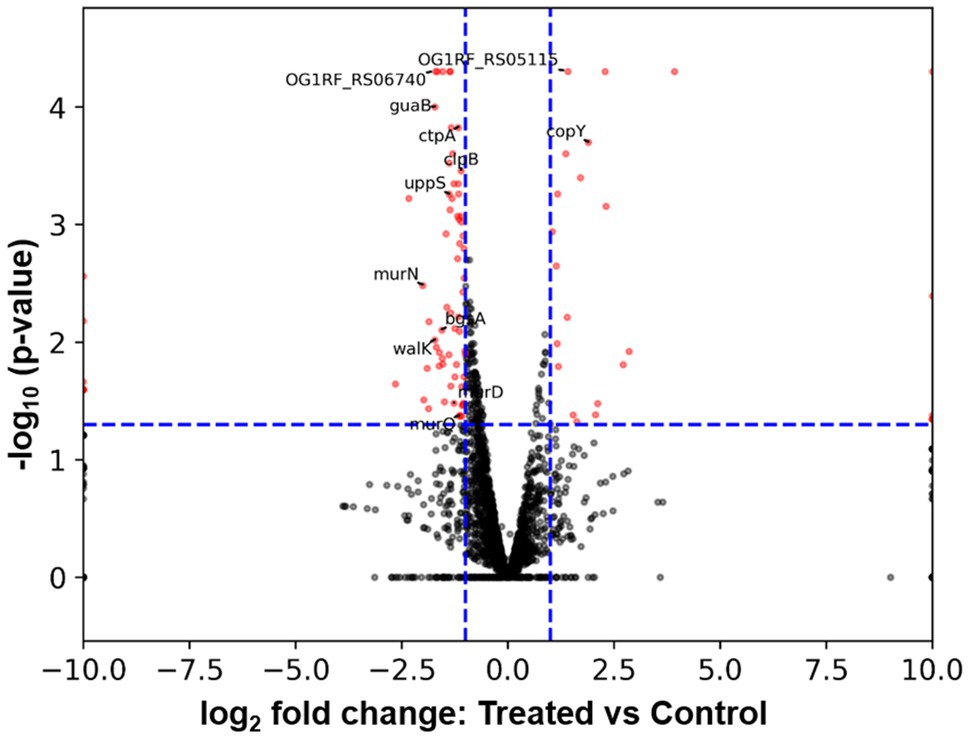

To further understand how E. faecalis responded to B. subtilis natto supernatant, we searched for DEGs between E. faecalis treated with or without B. subtilis natto supernatant using RNA-seq analysis. According to the RNA-seq results, approximately 95.94 and 97.98% of the clean reads from the treated and control (untreated) groups were mapped to the reference genome, respectively. Among the 2,657 genes detected by RNA-seq [2,658 genes present in E. faecalis OG1RF (Bourgogne et al., 2008)], 95 genes were identified as differentially expressed [value of p≤0.05 and fold change (FC)≥2] in the treated group (Figure 7 and Supplementary Table 1). Among these DEGs, 70 genes were identified as significantly downregulated, and 25 genes were found to be significantly upregulated. Furthermore, Gene Ontology (GO) annotation analysis and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis were performed to identify DEGs at the biological function level. The GO annotation results showed that the genes associated with the ATP binding term were differentially expressed, and the KEGG pathway mapping results showed that some DEGs were involved in the peptidoglycan biosynthetic process (Supplementary Figures 1, 2). These results indicated that some genes encoding ATP binding protein or peptidoglycan biosynthetic genes might be differentially expressed due to B. subtilis natto supernatant treatment.

Figure 7. Volcano plot from RNA-seq data showing DEGs of E. faecalis in response to B. subtilis natto supernatant. The expression of each gene is represented by dots. Genes with a value of p≤0.05 and an FC≥2 were considered significantly differentially expressed (represented by red dots). The horizontal blue dashed lines indicate the positions on the Y axes for a -log10 (value of p=0.05), and the vertical blue dashed lines indicate the positions on the X axes for a±log2 (FC=2). The 13 DEGs labeled in the volcano plot were selected for further RT-qPCR analysis.

To verify the RNA-seq results, we selected a total of 13 DEGs, including some ATP binding protein-encoding genes and peptidoglycan biosynthetic genes, for further RT-qPCR analysis. As listed in Table 3, the up- or downregulation trends and relative expression of most selected DEGs, including three peptidoglycan biosynthetic genes [murD (OG1RF_RS03760), murN (OG1RF_RS08680), and uppS (OG1RF_RS09795)], bgsA (OG1RF_RS11220), and walK (OG1RF_RS05035), were consistent with the RNA-seq results. Furthermore, a correlation between the six downregulated DEGs listed above and E. faecalis cell wall homeostasis and biofilm formation has been reported previously (Dubrac et al., 2008; Vollmer et al., 2008; Theilacker et al., 2009; Watanabe et al., 2012; Bucher et al., 2015). Peptidoglycan, an essential component of the cell wall in almost all bacteria, plays a key role in maintaining cell shape and serves as a scaffold to anchor other cell envelope components, such as proteins and teichoic acids (Vollmer et al., 2008). Gene bgsA (OG1RF_RS11220) encodes the putative glucosyltransferase designated biofilm-associated glycolipid synthesis A and synthesizes diglucosyl–diacylglycerol (DGlcDAG) in E. faecalis (Theilacker et al., 2009). DGlcDAG, a precursor of glycolipid and lipoteichoic acid, is involved in E. faecalis biofilm production, adherence to host cells and virulence in vivo (Theilacker et al., 2009). Gene walK (OG1RF_RS05035) encodes the membrane-linked histidine kinase WalK. WalK is a key element in the WalK/WalR two-component signal transduction system, which regulates genes involved in cell wall metabolism, biofilm production, virulence regulation, oxidative stress resistance, and antibiotic resistance in low-G+C Gram-positive bacteria, including E. faecalis (Dubrac et al., 2008; Watanabe et al., 2012). Based on these findings, we focused on the six downregulated cell wall- and biofilm-related genes in E. faecalis in further investigations.

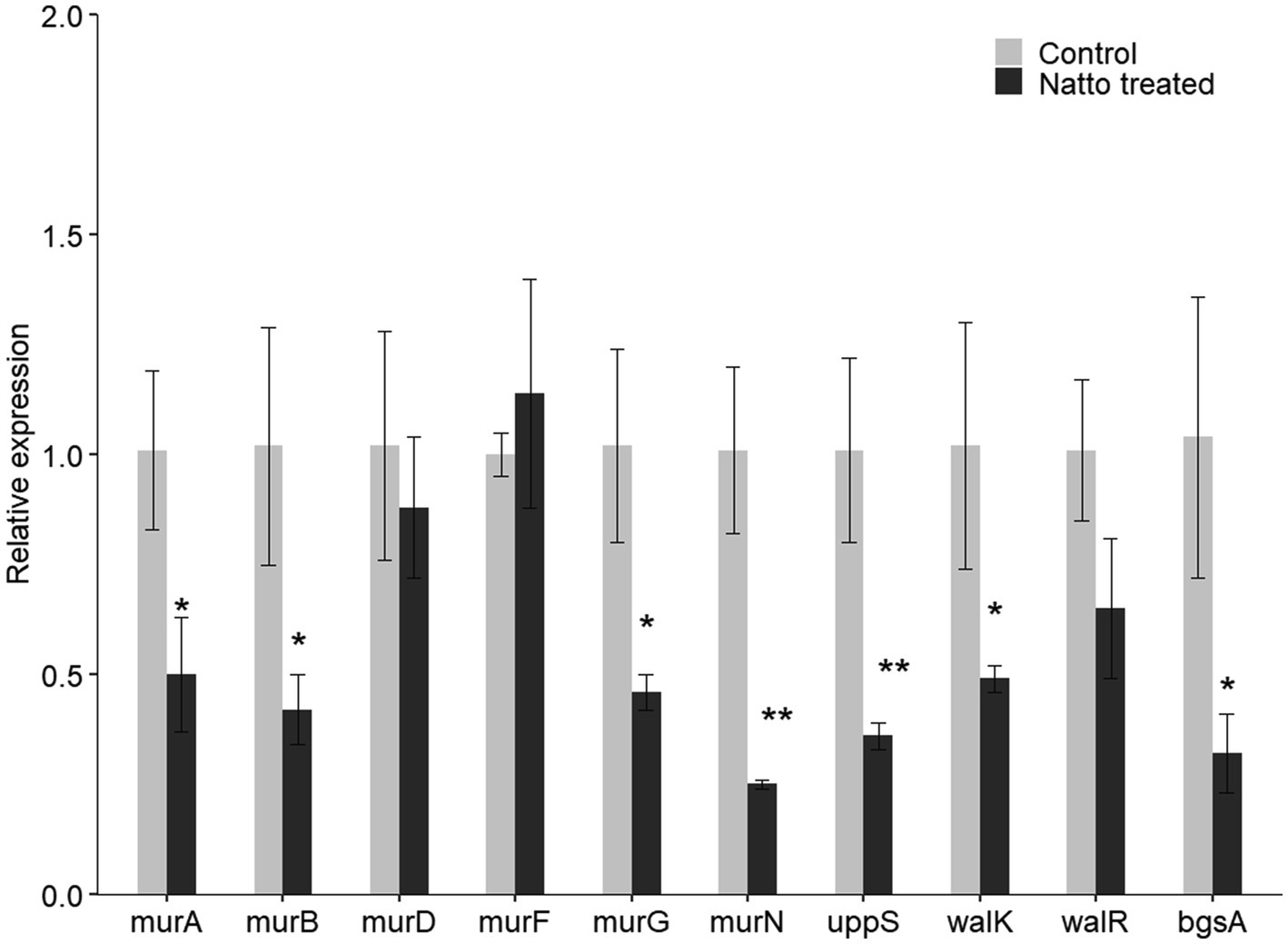

To investigate whether B. subtilis natto supernatant inhibits the expression of other genes in the peptidoglycan biosynthesis pathway and WalK/WalR regulatory system, the relative expression of UDP-GlcNAc enolpyruvyl transferase (murA; OG1RF_RS10140), murB (OG1RF_RS10725), murF (OG1RF_RS03015), and murG (OG1RF_RS03765) in the peptidoglycan biosynthesis pathway and the response regulator-encoding gene walR (OG1RF_RS05030) in the WalK/WalR two-component system were assessed further using RT-qPCR. As shown in Figure 8, the relative expression of several peptidoglycan biosynthetic genes except murF was indeed inhibited due to B. subtilis natto supernatant treatment. The relative expression of walR in the WalK/WalR two-component system was also inhibited. Taken together with the RT-qPCR results of the six cell wall- and biofilm-related genes identified from RNA-seq, these results indicate that B. subtilis natto supernatant might interfere with the E. faecalis peptidoglycan biosynthesis pathway, WalK/WalR two-component system and bgsA, thus inhibiting biofilm formation.

Figure 8. B. subtilis natto supernatant inhibits E. faecalis cell wall- and biofilm-related genes. E. faecalis OG1RF was cultured anaerobically in the presence or absence of B. subtilis natto supernatant for 24h. The relative expression of genes in the peptidoglycan biosynthesis pathway (murA, murB, murD, murF, and uppS), genes in the WalK/WalR two-component system (walK and walR), and bgsA were assessed using RT-qPCR. The data are presented as the means±SDs (n=3). *p<0.05 and **p<0.01 compared with each negative control group (Student’s t-test).

In this study, we found that the culture supernatant of B. subtilis natto can potently inhibit E. faecalis adherence to Caco-2 cell monolayers, aggregation, and biofilm production. These findings support the idea that some derivatives present in B. subtilis natto supernatant may have antibiofilm activity against E. faecalis. Consistent with this idea, some derivatives of Bacillus species have been shown to inhibit the formation of biofilms by several bacterial pathogens (Rivardo et al., 2009; Yoo et al., 2019; Tazehabadi et al., 2021). Rivardo et al. (2009) found that biosurfactants secreted by B. subtilis and B. licheniformis can effectively inhibit biofilm formation of Escherichia coli and S. aureus. Yoo et al. (2019) reported that Bacillus velezensis supernatant containing 1-deoxynojirimycin can decrease the biofilm production of Streptococcus mutans. Tazehabadi et al. (2021) mentioned that the bacteriocins subtilosin A and subtilin produced by B. subtilis and B. amyloliquefaciens, respectively, play a key role in inhibiting Salmonella biofilm formation (Yoo et al., 2019).

We also found that E. faecalis produced fewer exopolysaccharides under treatment with the culture supernatant of B. subtilis natto than under control conditions. Previous studies (Ramos et al., 2019) have shown that β-1,6-linked poly-N-acetylglucosamine (polyGlcNAc) in exopolysaccharides produced by E. faecalis bacteria enables the bacteria to successfully penetrate semisolid surfaces and translocate through human epithelial cell monolayers (Ramos et al., 2019). Thus, the inhibitory effect on E. faecalis exopolysaccharide production might also contribute to reducing polyGlcNAc production, thus mitigating the pathogenicity of E. faecalis.

In addition to exerting an inhibitory effect on exopolysaccharide production, B. subtilis natto supernatant restructured carbohydrates in the E. faecalis cell envelope. A previous study reported that the structure and composition of the bacterial cell envelope are linked to bacterial cell surface properties, such as surface stickiness (Sengupta et al., 2013). Another study reported that bacterial cells with greater surface stickiness have a tendency to aggregate (Kragh et al., 2016). In addition, the increased tendency to aggregate has been shown to be associated with increased biofilm production in Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Deziel et al., 2001; Haussler et al., 2003). Based on these findings, we infer that B. subtilis natto supernatant may alter E. faecalis cell envelope composition and cell surface properties, thereby interfering with E. faecalis adhesion to host tissues, aggregation, and biofilm production.

Via RNA-seq and RT-qPCR analysis, we found that B. subtilis natto supernatant inhibited the expression of bgsA, which encodes biofilm-associated glycolipid synthesis A, in E. faecalis. Previous studies (Theilacker et al., 2009) have shown that inactivation of bgsA in E. faecalis leads to a lack of DGlcDAG in cell membranes and to accumulation of longer lipoteichoic acid structures in cell walls, thus impairing E. faecalis adherence to host tissues and biofilm production. In addition to bgsA, walK and walR in the WalK/WalR two-component system were inhibited in E. faecalis treated with B. subtilis natto supernatant. In low-G+C Gram-positive bacteria, the activation of the WalK/WalR two-component system is essential for lateral cell wall synthesis and cell elongation, whereas depletion of this system may cause defects in cell morphology, murein (peptidoglycan) synthesis, and biofilm formation (Dubrac et al., 2008; Takada and Yoshikawa, 2018). Moreover, we also found that several peptidoglycan biosynthetic genes (murA, murB, murD, murG, murN, and uppS) in E. faecalis were inhibited. Since peptidoglycan is a crucial structural element in the cell walls of most bacteria, interference with its biosynthesis results in impaired biofilm formation and even cell lysis (Vollmer et al., 2008; Bucher et al., 2015). The downregulated genes listed above are all related to cell envelope synthesis and biofilm formation in E. faecalis. The evidence suggests that B. subtilis natto supernatant targets E. faecalis cell envelope synthesis and therefore interferes with the cell envelope composition and biofilm formation of E. faecalis.

Our findings reveal that B. subtilis natto supernatant can likely inhibit biofilm formation of E. faecalis via interference with E. faecalis cell envelope synthesis. Notably, the bacterial cell envelope synthetic process has been reported to be the major target for many antibacterial agents (McCallum et al., 2011). Many antibiotics act by blocking or disrupting bacterial peptidoglycan biosynthesis, such as fosfomycin, which inhibits MurA (Hashemian et al., 2019), and tunicamycin, which inhibits bacterial phospho-N-acetylmuramic acid (MurNAc)-pentapeptide translocase (MraY; Yamamoto et al., 2019). Furthermore, because maintenance of cell wall homeostasis and growth in low-G+C Gram-positive bacteria is essential, the WalK/WalR two-component system has been proposed as a novel target for antibacterial agents that are effective against multidrug-resistant bacteria, including MRSA and vancomycin-resistant E. faecalis (Fabret and Hoch, 1998; Gotoh et al., 2010). Watanabe et al. (2012) reported that the novel antibiotic signermycin B from Streptomyces extracts can function as a WalK inhibitor, targeting the conserved dimerization domain of WalK to inhibit autophosphorylation (Watanabe et al., 2012). Collectively, these studies provide evidence that some substances that function like antibiotics or WalK inhibitors may be present in the culture supernatant of B. subtilis natto. Further investigations are necessary to identify potential antibiofilm agents in the culture supernatant of B. subtilis natto.

The therapeutic potential of B. subtilis and its derivatives in animals has been reported in previous studies (Cartman et al., 2008; Piewngam et al., 2018). One previous study (Cartman et al., 2008) showed that B. subtilis spores can germinate in the chicken gastrointestinal tract. Another study (Piewngam et al., 2018) showed that mice fed B. subtilis spores exhibit complete decolonization of MRSA in the feces and intestines. These studies provide evidence that B. subtilis natto spores may germinate to form vegetative cells and produce functional substances in host gastrointestinal tracts.

In this work, our results showed that B. subtilis natto derivatives present in the culture supernatant could effectively inhibit the formation of E. faecalis biofilms. These derivatives downregulated the transcription of genes involved in membrane glycolipid biosynthesis, the WalK/WalR two-component system, and peptidoglycan biosynthesis, which may contribute to changes in the structural components of the cell envelope and therefore affect biofilm formation ability in E. faecalis. Based on these findings, we propose that natto or the probiotic B. subtilis natto could be used in the management of E. faecalis biofilm infections.

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found online at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/, GSE184249.

Y-CL wrote the manuscript. K-TL, W-SH, and Y-CL designed the experimental plan. Y-CL and C-YW performed all experiments and analyzed the relevant data. H-TH and M-KL assisted with carbohydrate composition analysis using HPAEC and data interpretation. All authors contributed to the revision and final review of the manuscript.

This work was funded by grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology (nos. 107-2313-B-002-028 and 108-2313-B-002-056-MY3), Taiwan.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

We thank Gary M. Dunny of the University of Minnesota for supplying isolates of E. faecalis. We also appreciate the excellent technical assistance of the Technology Commons at the College of Life Science, NTU (Taiwan) for scanning electron microscopy and confocal laser scanning microscopy.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at:

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2021.785351/full#supplementary-material

MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; γ-PGA, γ-poly-DL-glutamic acid; FBS, fetal bovine serum; PFA, paraformaldehyde; EPS, extracellular polymeric substance; PSA, phenol-sulfuric acid; HPAEC, high-performance anion-exchange chromatography; PAD, pulsed amperometric detector; TFA, trifluoroacetic acid; TE, Tris-EDTA; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; A, absorbance; SEM, scanning electron microscopy; CLSM, confocal laser scanning microscopy; rRNA, ribosomal RNA; qRT-qPCR, quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction; OD, optical density; ddH2O, double-distilled water; CFU, colony-forming units; WT, wild type; CFP, cyan fluorescent protein; DEGs, differentially expressed genes; FC, fold change; 1-DNJ, 1-deoxynojirimycin; polyGlcNAc, β-1,6-linked poly-N-acetylglucosamine.

Arias, C. A., Contreras, G. A., and Murray, B. E. (2010). Management of multidrug-resistant enterococcal infections. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 16, 555–562. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03214.x

Arias, C. A., and Murray, B. E. (2012). The rise of the Enterococcus: beyond vancomycin resistance. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 10, 266–278. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2761

Baccouri, O., Boukerb, A. M., Farhat, L. B., Zebre, A., Zimmermann, K., Domann, E., et al. (2019). Probiotic potential and safety evaluation of Enterococcus faecalis OB14 and OB15, isolated From traditional Tunisian Testouri cheese and Rigouta, using physiological and genomic analysis. Front. Microbiol. 10:881. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00881

Baldassarri, L., Cecchini, R., Bertuccini, L., Ammendolia, M. G., Iosi, F., Arciola, C. R., et al. (2001). Enterococcus spp. produces slime and survives in rat peritoneal macrophages. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 190, 113–120. doi: 10.1007/s00430-001-0096-8

Bandyopadhyay, A., O’Brien, S., Frank, K. L., Dunny, G. M., and Hu, W. S. (2016). Antagonistic donor density effect conserved in multiple enterococcal conjugative plasmids. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 82, 4537–4545. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00363-16

Barnes, A. M. T., Dale, J. L., Chen, Y., Manias, D. A., Greenwood Quaintance, K. E., Karau, M. K., et al. (2017). Enterococcus faecalis readily colonizes the entire gastrointestinal tract and forms biofilms in a germ-free mouse model. Virulence 8, 282–296. doi: 10.1080/21505594.2016.1208890

Barrett, T., Wilhite, S. E., Ledoux, P., Evangelista, C., Kim, I. F., Tomashevsky, M., et al. (2013). NCBI GEO: archive for functional genomics data sets--update. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D991–D995. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1193

Bourgogne, A., Garsin, D. A., Qin, X., Singh, K. V., Sillanpaa, J., Yerrapragada, S., et al. (2008). Large scale variation in enterococcus faecalis illustrated by the genome analysis of strain OG1RF. Genome Biol. 9:R110. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-7-r110

Bucher, T., Oppenheimer-Shaanan, Y., Savidor, A., Bloom-Ackermann, Z., and Kolodkin-Gal, I. (2015). Disturbance of the bacterial cell wall specifically interferes with biofilm formation. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 7, 990–1004. doi: 10.1111/1758-2229.12346

Cartman, S. T., La Ragione, R. M., and Woodward, M. J. (2008). Bacillus subtilis spores germinate in the chicken gastrointestinal tract. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 5254–5258. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00580-08

Ch’ng, J. H., Chong, K. K. L., Lam, L. N., Wong, J. J., and Kline, K. A. (2019). Biofilm-associated infection by enterococci. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 17, 82–94. doi: 10.1038/s41579-018-0107-z

Chatterjee, A., Cook, L. C., Shu, C. C., Chen, Y., Manias, D. A., Ramkrishna, D., et al. (2013). Antagonistic self-sensing and mate-sensing signaling controls antibiotic-resistance transfer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 110, 7086–7090. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1212256110

Choi, N. Y., Bae, Y. M., and Lee, S. Y. (2015). Cell surface properties and biofilm formation of pathogenic bacteria. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 24, 2257–2264. doi: 10.1007/s10068-015-0301-y

Clewell, D. B. (1990). Movable genetic elements and antibiotic resistance in enterococci. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 9, 90–102. doi: 10.1007/BF01963632

Clewell, D. B., Francia, M. V., Flannagan, S. E., and An, F. Y. (2002). Enterococcal plasmid transfer: sex pheromones, transfer origins, relaxases, and the Staphylococcus aureus issue. Plasmid 48, 193–201. doi: 10.1016/s0147-619x(02)00113-0

Dale, J. L., Cagnazzo, J., Phan, C. Q., Barnes, A. M., and Dunny, G. M. (2015). Multiple roles for enterococcus faecalis glycosyltransferases in biofilm-associated antibiotic resistance, cell envelope integrity, and conjugative transfer. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 59, 4094–4105. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00344-15

Dale, J. L., Nilson, J. L., Barnes, A. M. T., and Dunny, G. M. (2017). Restructuring of Enterococcus faecalis biofilm architecture in response to antibiotic-induced stress. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 3:15. doi: 10.1038/s41522-017-0023-4

Deziel, E., Comeau, Y., and Villemur, R. (2001). Initiation of biofilm formation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa 57RP correlates with emergence of hyperpiliated and highly adherent phenotypic variants deficient in swimming, swarming, and twitching motilities. J. Bacteriol. 183, 1195–1204. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.4.1195-1204.2001

Donlan, R. M., and Costerton, J. W. (2002). Biofilms: survival mechanisms of clinically relevant microorganisms. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 15, 167–193. doi: 10.1128/CMR.15.2.167-193.2002

Dubois, M., Gilles, K., Hamilton, J. K., Rebers, P. A., and Smith, F. (1951). A colorimetric method for the determination of sugars. Nature 168:167. doi: 10.1038/168167a0

Dubrac, S., Bisicchia, P., Devine, K. M., and Msadek, T. (2008). A matter of life and death: cell wall homeostasis and the WalKR (YycGF) essential signal transduction pathway. Mol. Microbiol. 70, 1307–1322. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06483.x

Dunny, G. M., Brown, B. L., and Clewell, D. B. (1978). Induced cell aggregation and mating in Streptococcus faecalis: evidence for a bacterial sex pheromone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 75, 3479–3483. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.7.3479

Edgar, R., Domrachev, M., and Lash, A. E. (2002). Gene expression omnibus: NCBI gene expression and hybridization array data repository. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 207–210. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.207

Elshaghabee, F. M. F., Rokana, N., Gulhane, R. D., Sharma, C., and Panwar, H. (2017). Bacillus as potential probiotics: status, concerns, and future perspectives. Front. Microbiol. 8:1490. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01490

Fabret, C., and Hoch, J. A. (1998). A two-component signal transduction system essential for growth of Bacillus subtilis: implications for anti-infective therapy. J. Bacteriol. 180, 6375–6383. doi: 10.1128/JB.180.23.6375-6383.1998

Fernandez Guerrero, M. L., Goyenechea, A., Verdejo, C., Roblas, R. F., and de Gorgolas, M. (2007). Enterococcal endocarditis on native and prosthetic valves: a review of clinical and prognostic factors with emphasis on hospital-acquired infections as a major determinant of outcome. Medicine (Baltimore) 86, 363–377. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e31815d5386

Flemming, H. C., Neu, T. R., and Wozniak, D. J. (2007). The EPS matrix: the “house of biofilm cells”. J. Bacteriol. 189, 7945–7947. doi: 10.1128/JB.00858-07

Flemming, H. C., and Wingender, J. (2010). The biofilm matrix. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8, 623–633. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2415

Frieden, T. (2013). Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States. Washington, D.C.: US Department of Health and Human Services.

Gotoh, Y., Eguchi, Y., Watanabe, T., Okamoto, S., Doi, A., and Utsumi, R. (2010). Two-component signal transduction as potential drug targets in pathogenic bacteria. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 13, 232–239. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2010.01.008

Hashemian, S. M. R., Farhadi, Z., and Farhadi, T. (2019). Fosfomycin: the characteristics, activity, and use in critical care. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 15, 525–530. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S199119

Haussler, S., Ziegler, I., Lottel, A., Gotz, F. V., Rohde, M., Wehmhohner, D., et al. (2003). Highly adherent small-colony variants of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis lung infection. J. Med. Microbiol. 52, 295–301. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.05069-0

Hoyle, B. D., and Costerton, J. W. (1991). Bacterial resistance to antibiotics: the role of biofilms. Prog. Drug Res. 37, 91–105. doi: 10.1007/978-3-0348-7139-6_2

Kamada, N., Chen, G. Y., Inohara, N., and Nunez, G. (2013). Control of pathogens and pathobionts by the gut microbiota. Nat. Immunol. 14, 685–690. doi: 10.1038/ni.2608

Katayama, R., Matsumoto, Y., Higashi, Y., Sun, S., Sasao, H., Tanimoto, Y., et al. (2021). Bacillus subtilis var. natto increases the resistance of Caenorhabditis elegans to gram-positive bacteria. J. Appl. Microbiol. doi: 10.1111/jam.15156 Epub ahead of print

Kaur, S., Sharma, P., Kalia, N., Singh, J., and Kaur, S. (2018). Anti-biofilm properties of the fecal probiotic lactobacilli against vibrio spp. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 8:120. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2018.00120

Klevens, R. M., Edwards, J. R., Richards, C. L. Jr., Horan, T. C., Gaynes, R. P., Pollock, D. A., et al. (2007). Estimating health care-associated infections and deaths in U.S. hospitals, 2002. Public Health Rep. 122, 160–166. doi: 10.1177/003335490712200205

Kragh, K. N., Hutchison, J. B., Melaugh, G., Rodesney, C., Roberts, A. E., Irie, Y., et al. (2016). Role of multicellular aggregates in biofilm formation. mBio 7:e00237. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00237-16

Kuo, L. C., Cheng, W. Y., Wu, R. Y., Huang, C. J., and Lee, K. T. (2006). Hydrolysis of black soybean isoflavone glycosides by Bacillus subtilis natto. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 73, 314–320. doi: 10.1007/s00253-006-0474-7

Kuo, L. C., and Lee, K. T. (2008). Cloning, expression, and characterization of two beta-glucosidases from isoflavone glycoside-hydrolyzing Bacillus subtilis natto. J. Agric. Food Chem. 56, 119–125. doi: 10.1021/jf072287q

Letourneau, J., Levesque, C., Berthiaume, F., Jacques, M., and Mourez, M. (2011). In vitro assay of bacterial adhesion onto mammalian epithelial cells. J. Vis. Exp. 16:2783. doi: 10.3791/2783

Lin, Y. C., Chen, E. H., Chen, R. P., Dunny, G. M., Hu, W. S., and Lee, K. T. (2021). Probiotic bacillus affect enterococcus faecalis antibiotic resistance transfer by interfering with pheromone signaling cascades. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 87:e0044221. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00442-21

Liu, F., Jin, P., Gong, H., Sun, Z., Du, L., and Wang, D. (2020a). Antibacterial and antibiofilm activities of thyme oil against foodborne multiple antibiotics-resistant enterococcus faecalis. Poult. Sci. 99, 5127–5136. doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2020.06.067

Liu, F., Sun, Z., Wang, F., Liu, Y., Zhu, Y., Du, L., et al. (2020b). Inhibition of biofilm formation and exopolysaccharide synthesis of enterococcus faecalis by phenyllactic acid. Food Microbiol. 86:103344. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2019.103344

Livak, K. J., and Schmittgen, T. D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods 25, 402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262

Mah, T. F., and O’Toole, G. A. (2001). Mechanisms of biofilm resistance to antimicrobial agents. Trends Microbiol. 9, 34–39. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(00)01913-2

Manias, D. A., and Dunny, G. M. (2018). Expression of adhesive pili and the collagen-binding adhesin ace is activated by ArgR family transcription factors in enterococcus faecalis. J. Bacteriol. 200:e00269-18. doi: 10.1128/JB.00269-18

McCallum, N., Meier, P. S., Heusser, R., and Berger-Bachi, B. (2011). Mutational analyses of open reading frames within the vraSR operon and their roles in the cell wall stress response of Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55, 1391–1402. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01213-10

Monte, J., Abreu, A. C., Borges, A., Simoes, L. C., and Simoes, M. (2014). Antimicrobial activity of selected phytochemicals against Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus and their biofilms. Pathogens 3, 473–498. doi: 10.3390/pathogens3020473

Murray, B. E. (1997). Vancomycin-resistant enterococci. Am. J. Med. 102, 284–293. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(99)80270-8

Nishito, Y., Osana, Y., Hachiya, T., Popendorf, K., Toyoda, A., Fujiyama, A., et al. (2010). Whole genome assembly of a natto production strain Bacillus subtilis natto from very short read data. BMC Genomics 11:243. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-243

Paulsen, I. T., Banerjei, L., Myers, G. S., Nelson, K. E., Seshadri, R., Read, T. D., et al. (2003). Role of mobile DNA in the evolution of vancomycin-resistant enterococcus faecalis. Science 299, 2071–2074. doi: 10.1126/science.1080613

Piewngam, P., Zheng, Y., Nguyen, T. H., Dickey, S. W., Joo, H. S., Villaruz, A. E., et al. (2018). Pathogen elimination by probiotic bacillus via signalling interference. Nature 562, 532–537. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0616-y

Ramos, Y., Rocha, J., Hael, A. L., van Gestel, J., Vlamakis, H., Cywes-Bentley, C., et al. (2019). PolyGlcNAc-containing exopolymers enable surface penetration by non-motile enterococcus faecalis. PLoS Pathog. 15:e1007571. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007571

Rivardo, F., Turner, R. J., Allegrone, G., Ceri, H., and Martinotti, M. G. (2009). Anti-adhesion activity of two biosurfactants produced by bacillus spp. prevents biofilm formation of human bacterial pathogens. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 83, 541–553. doi: 10.1007/s00253-009-1987-7

Saarela, M., Lahteenmaki, L., Crittenden, R., Salminen, S., and Mattila-Sandholm, T. (2002). Gut bacteria and health foods--the European perspective. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 78, 99–117. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1605(02)00235-0

Sengupta, R., Altermann, E., Anderson, R. C., McNabb, W. C., Moughan, P. J., and Roy, N. C. (2013). The role of cell surface architecture of lactobacilli in host-microbe interactions in the gastrointestinal tract. Mediat. Inflamm. 2013:237921. doi: 10.1155/2013/237921

Sievert, D. M., Ricks, P., Edwards, J. R., Schneider, A., Patel, J., Srinivasan, A., et al. (2013). Antimicrobial-resistant pathogens associated with healthcare-associated infections: summary of data reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009-2010. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 34, 1–14. doi: 10.1086/668770

Takada, H., and Yoshikawa, H. (2018). Essentiality and function of WalK/WalR two-component system: the past, present, and future of research. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 82, 741–751. doi: 10.1080/09168451.2018.1444466

Tazehabadi, M. H., Algburi, A., Popov, I. V., Ermakov, A. M., Chistyakov, V. A., Prazdnova, E. V., et al. (2021). Probiotic bacilli inhibit salmonella biofilm formation without killing planktonic cells. Front. Microbiol. 12:615328. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.615328

Theilacker, C., Sanchez-Carballo, P., Toma, I., Fabretti, F., Sava, I., Kropec, A., et al. (2009). Glycolipids are involved in biofilm accumulation and prolonged bacteraemia in enterococcus faecalis. Mol. Microbiol. 71, 1055–1069. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06587.x

Vollmer, W., Blanot, D., and de Pedro, M. A. (2008). Peptidoglycan structure and architecture. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 32, 149–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2007.00094.x

Watanabe, T., Igarashi, M., Okajima, T., Ishii, E., Kino, H., Hatano, M., et al. (2012). Isolation and characterization of signermycin B, an antibiotic that targets the dimerization domain of histidine kinase WalK. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56, 3657–3663. doi: 10.1128/AAC.06467-11

Wu, S., Liu, Y., Lei, L., and Zhang, H. (2021). Endogenous antisense walR RNA modulates biofilm organization and pathogenicity of enterococcus faecalis. Exp. Ther. Med. 21:69. doi: 10.3892/etm.2020.9501

Yamamoto, K., Katsuyama, A., and Ichikawa, S. (2019). Structural requirement of tunicamycin V for MraY inhibition. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 27, 1714–1719. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2019.02.035

Keywords: probiotics, Bacillus subtilis natto, Enterococcus faecalis, biofilm, cell envelope synthesis

Citation: Lin Y-C, Wu C-Y, Huang H-T, Lu M-K, Hu W-S and Lee K-T (2021) Bacillus subtilis natto Derivatives Inhibit Enterococcal Biofilm Formation via Restructuring of the Cell Envelope. Front. Microbiol. 12:785351. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.785351

Received: 29 September 2021; Accepted: 18 November 2021;

Published: 09 December 2021.

Edited by:

Marilena Budroni, University of Sassari, ItalyReviewed by:

Sunil D. Saroj, Symbiosis International University, IndiaCopyright © 2021 Lin, Wu, Huang, Lu, Hu and Lee. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kung-Ta Lee, a3RsZWVAbnR1LmVkdS50dw==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.