- 1State Key Laboratory for Diagnosis and Treatment of Infectious Diseases, National Clinical Research Center for Infectious Diseases, Collaborative Innovation Center for Diagnosis and Treatment of Infectious Diseases, The First Affiliated Hospital, College of Medicine, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China

- 2Department of Infectious Diseases, Haining People’s Hospital, Haining, China

- 3Department of Clinical Laboratory, Haining People’s Hospital, Haining, China

The taxonomy of the genus Neisseria remains confusing, particularly regarding Neisseria mucosa and Neisseria sicca. In 2012, ribosomal multi-locus sequence typing reclassified both as N. mucosa, but data concerning 17 N. sicca strains remain available in GenBank. The continuous progress of high-throughput sequencing has facilitated ready accessibility of whole-genome data, promoting vigorous development of average nucleotide identity (ANI) and high-resolution phylogenetic analysis. Here, we report that a Neisseria isolate, which caused native-valve endocarditis and multiple embolic brain infarcts in a patient with congenital heart disease, was misidentified as N. sicca by VITEK MS. This isolate was reclassified as N. mucosa by ANI blast (ANIb) and by phylogenetic analysis using whole-genome data yielded by the PacBio Sequel and Illumina NovaSeq PE150 platforms. The confusion evident in the GenBank and matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) databases suggests that N. mucosa (n = 13) and N. sicca (n = 16) in GenBank should be reclassified using ANIb and high-resolution phylogenetic analysis. The whole-genome data of 30 strains (including the clinical isolate) were compared with the data of 27 type Neisseria strains (including one N. sicca and two N. mucosa type strains) as a genomic index. In total, 25 (8 originally identified as N. mucosa and 17 originally identified as N. sicca) and 7 (1 originally identified as N. sicca and 6 originally identified as N. mucosa) strains were reclassified into the N. mucosa and Neisseria subflava groups, respectively; 1 residual N. mucosa strain was reclassified as Neisseria meningitidis. In conclusion, a combination of ANIb and robust phylogenetic analysis reclassified strains originally identified as N. mucosa and N. sicca into (principally) the N. mucosa group and the N. subflava group. The misclassified N. sicca and N. mucosa strains in the GenBank and MALDI-TOF MS databases were supposed to be corrected. Updated genomic classification strategy for originally identified N. mucosa and N. sicca strains was recommended to be adopted in GenBank.

Introduction

Neisseria mucosa and Neisseria sicca are both non-pathogenic species that inhabit the human pharynx (Caugant and Brynildsrud, 2020). However, they are phenotypically similar; N. mucosa forms mucoid colonies and reduces nitrates, whereas N. sicca forms dry, wrinkled colonies and does not reduce nitrates (Tønjum, 2005). Both species exhibit variable features; identification to the species level using phenotypic characters is difficult. Compared with traditional phenotypic approaches, genomic analyses are superior (Paul et al., 2019). Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) is now very accessible and affordable (Zong, 2020). On the basis of ribosomal multi-locus sequence typing (rMLST) findings, Bennett et al. (2012) proposed that N. sicca was a variant of N. mucosa. Using a phylogenetic taxonomic method, Caugant and Brynildsrud (2020) suggested that N. sicca and N. mucosa did not form monophyletic groups and might constitute a single species. Although the N. sicca strains evaluated by Bennett et al. (2012) have been corrected in GenBank, a couple of N. sicca strains remain.

Current, WGS-based, high-resolution, genomic taxonomic methods include the average nucleotide identity blast (ANIb) and phylogenetic analysis. ANIb of all genes conserved in two genomes measures the evolutionary distance between the strains (Altschul et al., 1997; Konstantinidis and Tiedje, 2005). The phylogenetic analysis uses gene sequences to infer the evolutionary pattern (Staley, 2006). Both algorithms are always used together; they are complementary. For example, of 181 Neisseria isolates examined, seven putative novel Neisseria species were identified by ANI and phylogenetic analysis (Diallo et al., 2019).

Here, we report the case of the clinical isolate SAMN18451419, which was identified as N. sicca by VITEK MS; it was reclassified as N. mucosa by ANIb and phylogenetic analysis (via WGS using the PacBio Sequel and Illumina NovaSeq PE150 platforms). This Neisseria strain was isolated from a patient with infective native-valve endocarditis and multiple embolic brain infarcts. This case and the findings by Bennett et al. (2012) and Caugant and Brynildsrud (2020) suggest that N. sicca and N. mucosa might be the same species. We thus used phylogenetic and ANIb analysis to reassign the “N. mucosa” and “N. sicca” strains in GenBank to the correct groups.

Materials and Methods

Ethics Approval Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine [approval no. 2021IIT 026 (fast track)].

Public Sequence Data

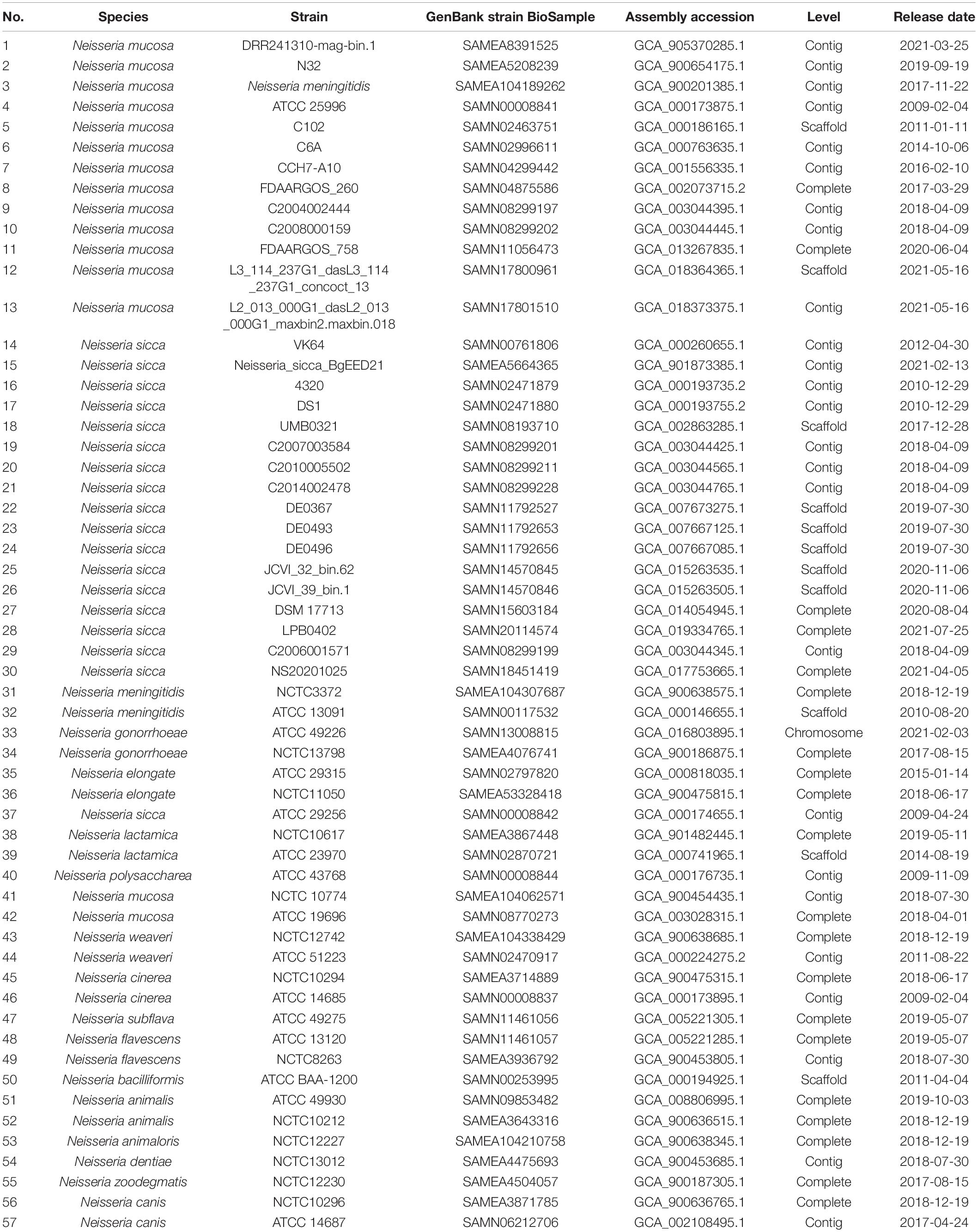

Whole-genome data from 56 strains were downloaded from GenBank using ‘‘Neisseria’’ as the search term1. Of these 56 strains, we selected 27 available from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and National Collection of Type Cultures (NCTC). We downloaded all genome data of Neisseria meningitidis (n = 2), Neisseria gonorrhoeae (n = 2), Neisseria elongata (n = 2), Neisseria lactamica (n = 2), N. mucosa (n = 2), N. sicca (n = 1), Neisseria weaveri (n = 2), Neisseria cinerea (n = 2), Neisseria flavescens (n = 2), Neisseria animalis (n = 2), Neisseria canis (n = 2), Neisseria polysaccharea (n = 1), Neisseria subflava (n = 1), Neisseria bacilliformis (n = 1), Neisseria animaloris (n = 1), Neisseria dentiae (n = 1), Neisseria zoodegmatis (n = 1), and previously identified N. mucosa (n = 13) and N. sicca (n = 16) (Table 1).

Identification of Strain SAMN18451419

Sampling and Clinical Data

A Gram-negative coccus was isolated from the blood culture of a patient with an intermittent fever that had persisted for 3 weeks. Clinical data were retrieved from the patient’s medical record.

Bacterial Isolation and Clinical Identification

The isolate was plated on blood and chocolate agar (Autobio, China) plates at 35°C under 5% (v/v) CO2 before testing (Humphries et al., 2021). Single colonies were selected from the plates. For phenotypic characterization, 3% (v/v) hydrogen peroxide and tetramethyl-p-phenylenediamine hydrochloride were used in the catalase and oxidation assays. For molecular characterization, the isolate was submitted to matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) using a VITEK MS platform (bioMérieux) and VITEK 2 Compact software (bioMérieux).

Whole-Genome Sequencing and Analysis

The Neisseria strain described earlier was subjected to WGS. Genomic DNA was extracted using a commercial kit (QIAGEN Gentra Puregene Yeast/Bact Kit, Germany) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. The library for single-molecule real-time (SMRT) sequencing was constructed (insert size 10 kb) using the SMRT Bell Template kit version 1.0; a next-generation sequencing library was generated using the NEBNext Ultra DNA Library Prep Kit (from Illumina), in accordance with the manufacturer’s recommendations. WGSs were obtained using the PacBio Sequel and Illumina NovaSeq PE150 platforms at Beijing Novogene Bioinformatics Technology Co., Ltd. Clean reads were assembled using SMRT Link ver. 5.1.0 (Supplementary Figure 1).

Data Availability

The complete genome data of strain SAMN18451419 have been deposited in GenBank with the accession number CP0725242.

Identification of Virulence-Associated Genes of Strain SAMN18451419

Virulence genes were identified using the Virulence Factor database3.

PubMLST Analysis of Strain SAMN18451419

After draft genome assembly, we used multi-locus sequence typing (MLST) for taxonomic identification. The assembled scaffolds were submitted to the Neisseria MLST website4 (Jolley et al., 2018).

Reclassification of N. mucosa and N. sicca

Phylogenetic Analysis

To characterize the evolutionary relationships among Neisseria isolates, we used a core genome-based phylogenetic tree to identify the Neisseria genomes [strain SAMN18451419, previously identified N. mucosa (n = 13) and N. sicca (n = 16), and 27 type Neisseria genomes] (Table 1). All genomes were annotated using RAST5. The core genes in Neisseria genomes were identified using RAST and Roary6. A maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree based on the core single-nucleotide polymorphism alignments was generated using MegaX (Kumar et al., 2018). Phylogenetic tree visualizations were produced by the Interactive Tree of Life7.

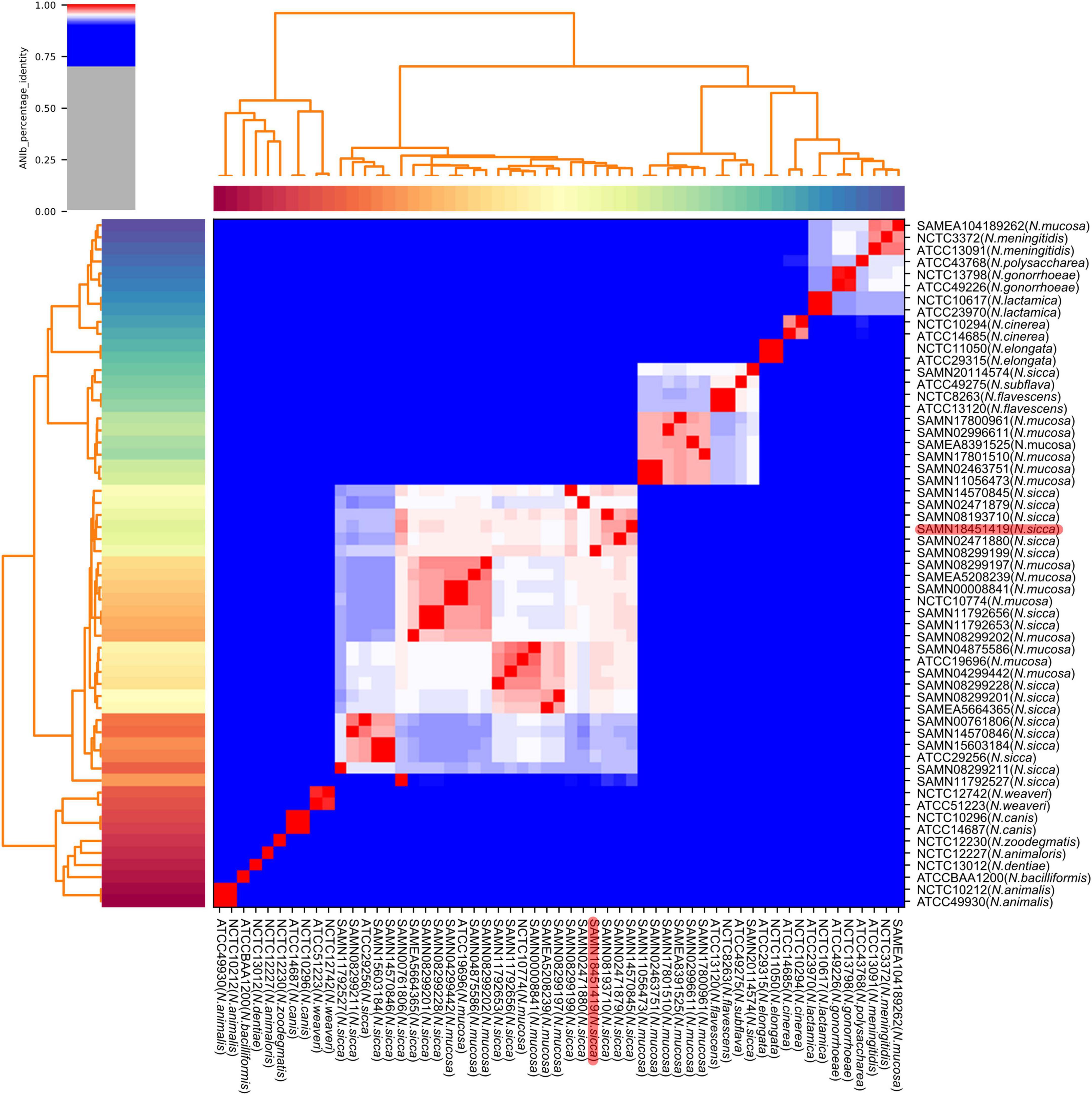

Average Nucleotide Identity Blast Analysis

ANIb analysis was performed using pyani8. The following genomes were analyzed: strain SAMN18451419, previously identified N. mucosa (n = 13) and N. sicca (n = 16), and 27 type Neisseria strains. Pairwise ANIb data for each strain were clustered and visualized using heatmap. All software mentioned earlier were implemented using the default settings.

Results

Case Presentation

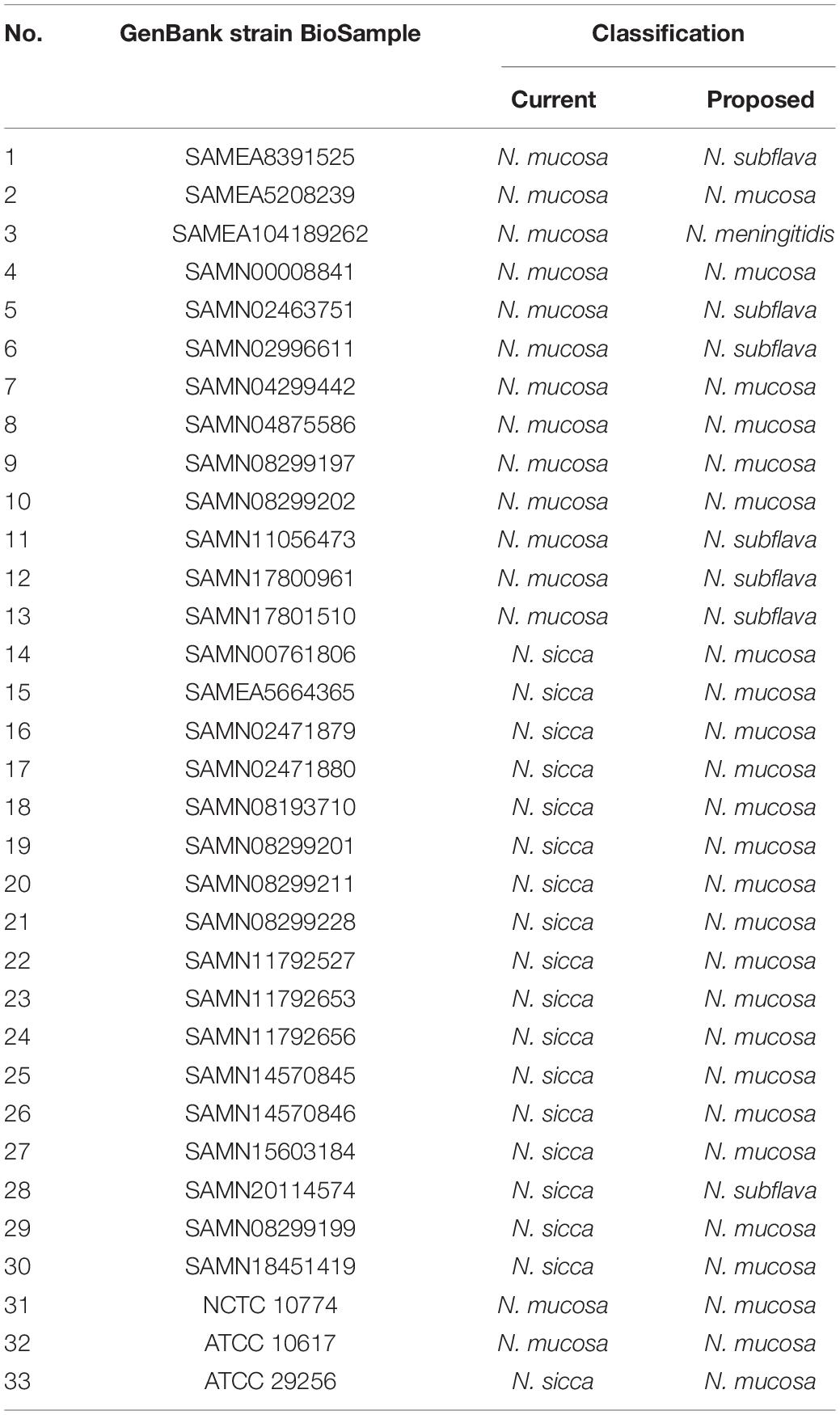

A 52-year-old man with a recurrent fever was admitted (day 0). A schematic of the disease course is shown in Figure 1. Before admission, he had developed non-specific symptoms, including high fever, fatigue, anorexia, nausea, and vomiting (all persisted for 3 weeks). Considering the high leukocyte count (15.9 × 109/L) and C-reactive protein level (144.1 mg/L), despite the absence of an obvious infective focus, empirical outpatient treatment (azlocillin sodium) was administered before admission; this treatment was ineffective. Empirical ticarcillin disodium and clavulanate potassium were prescribed from days 0 to 5. A Gram-negative diplococcus was isolated from blood cultures on day 1. Echocardiography on day 4 revealed vegetations attached to the anterior and posterior leaflets of the mitral valve, with dimensions of approximately 19 × 10 and 12 × 7.8 mm, respectively (Figure 1B). Cranial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) on day 6 showed multiple abnormal signals in the left occipital lobe and on both sides of the ventricle (Figure 1C). The antibiotics were switched to ceftriaxone and amoxicillin sodium clavulanate potassium, based on the drug sensitivities of the isolate (minimal inhibitory concentration of ceftriaxone ≤0.12 μg/ml; recorded from days 6 to 13). Cranial contrast-enhanced MRI revealed abnormal enhancement of punctate, patchy, and ring-shaped lesional regions (compared with the day 6 MRI image); infectious lesions were first considered on day 10 (Figure 1D). The body temperature returned to the normal level, followed by downward trends in the indicators of inflammation from days 1 to 10. However, a relapse developed on day 11. Follow-up heart ultrasonography showed that the vegetations attached to the mitral valve had shrunken (Figure 1E).

Figure 1. Clinical course of the patient (a schematic). (A) Gray-white colonies of strain SAMN18451419 growing on a blood agar plate. (B) Echocardiography revealed vegetations attached toe anterior and posterior leaflets of mitral valve, with dimensions of approximately 19 × 10 and 12 × 7.8 mm, respectively. (C) Cranial MRI revealed multiple abnormal shadows in left occipital lobe and on both sides of ventricle. (D) Cranial contrast-enhanced MRI revealed abnormal enhancement of punctate, patchy, and ring-shaped components of the lesion. (E) Echocardiography revealed a post-treatment reduction in vegetation attached to mitral valve. (F) CT revealed low-density lesions in left frontal, parietal, and occipital lobes with a small amount of hemorrhage after infarction. (G) Cranial CT revealed larger lesions and new low-density lesions in left cerebellar hemisphere. (H) Transesophageal echocardiography revealed a highly echoic mass (dimensions of approximately 1.07 × 1.08 × 1.69 cm) attached to anterior mitral valve leaflet. (I) HE staining of valvular tissue revealed connective tissue hyperplasia and collagenization, mucus changes, calcification, and both acute and chronic inflammatory cell infiltration and necrosis. MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; CT, computed tomography; HE, Hematoxylin-cosin.

The patient was then transferred to our main campus for further treatment. Piperacillin sodium and tazobactam sodium were prescribed from days 13 to 16. However, the high fever persisted. Follow-up ultrasonography of the heart, as well as cranial MRI, yielded results similar to the findings on day 15. The antibiotics were changed to ceftriaxone sodium and compound sulfamethoxazole from days 16 to 38. Symptoms of cerebral infarction manifested on day 17. Subsequent blood cultures were negative. Cranial contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) revealed low-density focus in the left frontal, parietal, and occipital lobes, with minor hemorrhage after infarction on day 18 (Figure 1F). On day 25, cranial CT showed that the lesion had expanded, and new low-density lesions had developed in the left cerebellar hemisphere. The focus of ischemic infarction was compared with the focus on day 18 (Figure 1G). On day 33, mitral valve replacement, tricuspid valvuloplasty, and left atrium folding were performed after preoperative transesophageal echocardiography had revealed a highly echoic mass (dimensions of approximately 1.07 × 1.08 × 1.69 cm) attached to the anterior mitral valve leaflet (Figure 1H). Histology revealed valvular connective tissue hyperplasia and collagenization, mucus changes, calcification, and both acute and chronic inflammatory cell infiltration and necrosis (Figure 1I). Follow-up ultrasonography of the heart (after the operation) revealed normal mechanical valve function without any obvious paravalvular leakage. On day 39, follow-up cranial CT showed that the low-density focus had been absorbed; the size was reduced relative to the size on day 31. The patient was discharged to home on anticoagulant therapy and scheduled for follow-up outpatient review 1 month later.

Clinical Phenotypic Identification of Strain SAMN18451419

The blood and chocolate agar plates both grew off-white Gram-negative diplococci (Figure 1A). The isolates exhibited both catalase and oxidase. Isolates from both plates were identified as N. sicca by VITEK MS and VITEK 2 Compact with 99.9% confidence.

General Genomic Features of Strain SAMN18451419

Sequencing of strain SAMN18451419 revealed a genome size of 2,566,407 bp with a G+C content of 51.1%. There was one scaffold featuring 2,295 protein-encoding genes, 61 transfer RNAs, and 12 ribosomal RNAs (Supplementary Figure 2).

Identification of Virulence-Associated Genes in Strain SAMN18451419

The genome encoded 21 putative virulence factors (Supplementary Figure 2).

PubMLST Analysis of Strain SAMN18451419

Strain SAMN18451419 was identified as a new sequence type using the Neisseria public databases for molecular typing and microbial genome diversity (PubMLST)9.

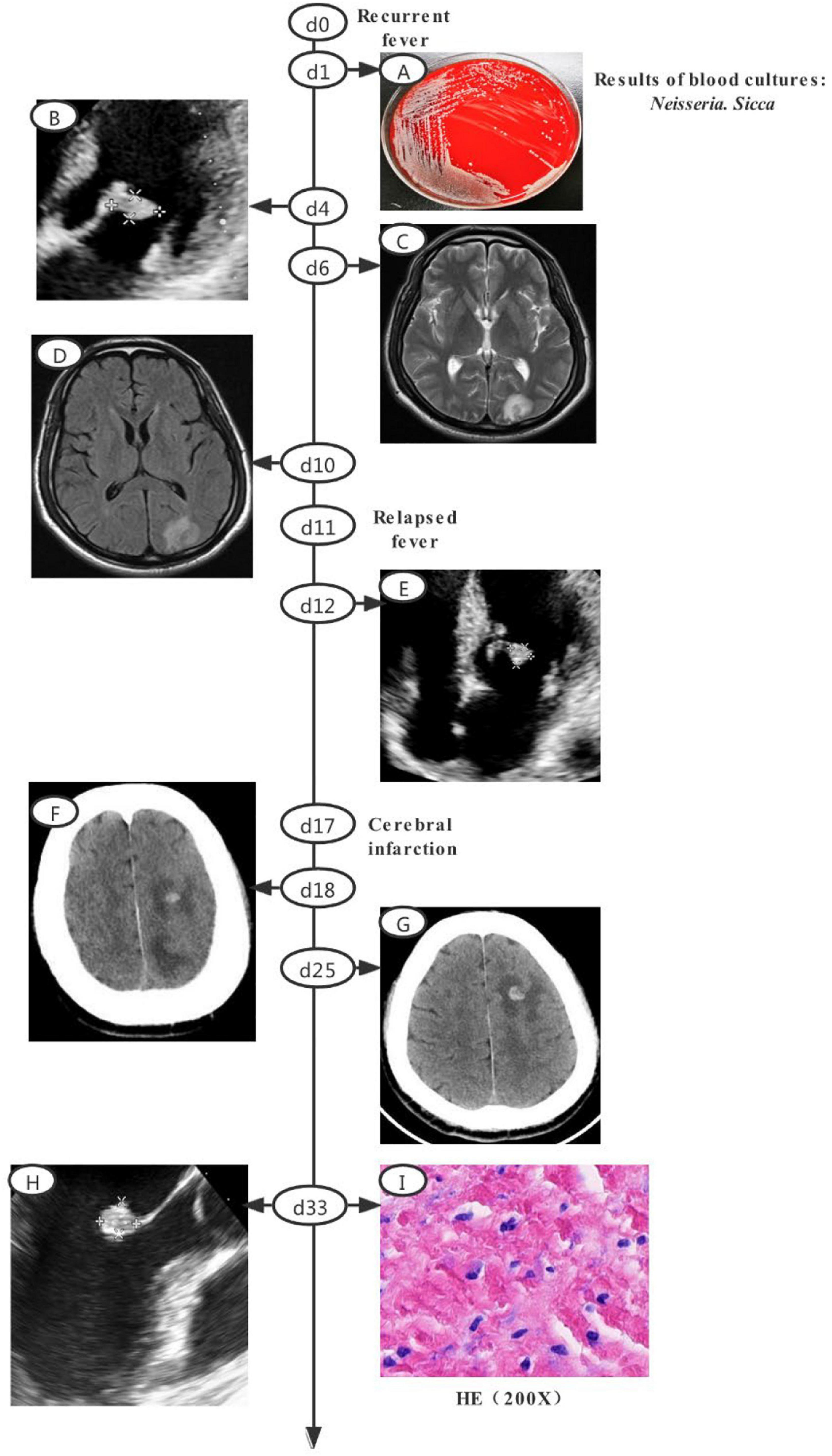

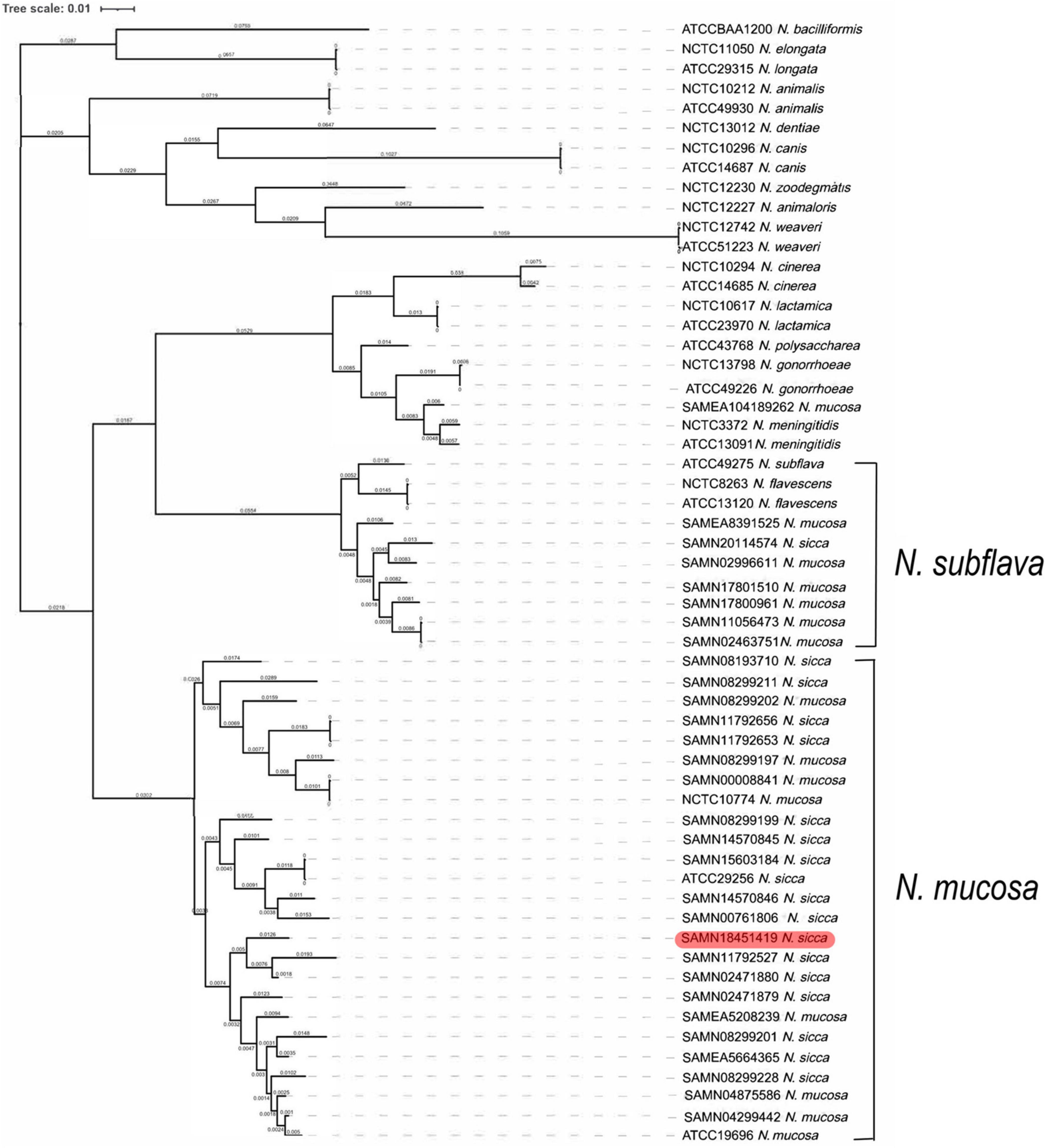

Phylogenetic Analysis of N. mucosa and N. sicca

We explored the phylogenetic relationships among N. mucosa, N. sicca, and the 27 Neisseria type strains based on the core genomes obtained via WGS. Clear separation of the strains listed in Table 1 was evident in the phylogenetic tree (Figure 2). Eight strains originally identified as N. mucosa (including two N. mucosa type strains ATCC 19696 and NCTC 10774) and 17 strains originally identified as N. sicca (including the clinical isolate SAMN18451419 and one N. sicca type strain ATCC 29256) clustered into the N. mucosa group. Six strains originally identified as N. mucosa and one strain originally identified as N. sicca clustered into the N. subflava group. Notably, strain SAMEA104189262, originally classified as N. mucosa, clustered with the N. meningitidis-type strains NCTC 3372 and ATCC 13091.

Figure 2. Phylogenetic analysis of 57 Neisseria strains. The maximum likelihood tree showed phylogeny of genus Neisseria based on WGS. The phylogenetic tree was generated for clinical isolate SAMN18451419, as well as 13 N. mucosa strains, 16 N. sicca strains, and 27 Neisseria type strains (including two N. mucosa and one N. sicca type strains). Red color code refers to clinical isolate SAMN18451419. WGS, whole-genome sequencing.

Average Nucleotide Identity Blast Analysis of N. mucosa and N. sicca

Consistent with the results of phylogenetic analysis, the eight strains originally identified as N. mucosa (including two N. mucosa type strains ATCC 19696 and NCTC 10774) and the 17 strains originally identified as N. sicca (including the clinical isolate SAMN18451419 and one N. sicca type strain ATCC 29256) co-clustered. Six strains originally identified as N. mucosa and one strain originally identified as N. sicca clustered with the N. subflava type strain ATCC 49275. One strain originally identified as N. mucosa (SAMEA104189262) clustered with two N. meningitidis type strains NCTC 3372 and ATCC 13091 (Figure 3). According to the combination of robust phylogenetic and ANIb analysis, the proposed reclassification of previously identified N. mucosa and N. sicca strains were listed in Table 2.

Figure 3. Heatmap and dendrogram of ANIb values of 57 Neisseria genomes. Sequences of clinical isolate SAMN18451419, as well as 13 N. mucosa and 16 N. sicca strains downloaded from GenBank, were characterized by pairwise ANIb with 27 Neisseria type strains (including two N. mucosa and one N. sicca type strains). Red color code refers to clinical isolate SAMN18451419. ANIb, average nucleotide identity blast.

Discussion

N. mucosa and N. sicca are genetically closely related and have a contentious taxonomic history [described in Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology and addressed by Bennett et al. (2012)]. Traditional bacterial taxonomic assignments use phenotypic approaches; these are generally unsatisfactory because phenotypes can vary (Brodie et al., 1971). WGS has greatly assisted bacterial taxonomy. Data ranging from small regions (from which 16S ribosomal RNAs are transcribed) to the entire genome are readily available (Mechergui et al., 2014). Modern genomic analysis approaches based on WGS, rMLST, cgMLST, ANIb, and phylogenetic analysis have flourished recently (Bennett et al., 2012; Zong, 2020).

We used phylogenetic analysis to reclassify the originally (mis)identified N. sicca and N. mucosa strains into the N. mucosa group, confirming the findings by Bennett et al. (2012). The term “N. mucosa group” is used because N. mucosa [originally termed Diplococcus mucosus by Von Lingelsheim in 1906 (Bennett et al., 2012)] was the first such species to be identified (Tønjum, 2005). The N. subflava group, in which one N. sicca, six N. mucosa, one N. subflava, and two N. flavescens strains co-clustered in our results, was also named in accordance with the same principle in the work by Bennett et al. (2012). Only one strain originally identified as N. sicca belonged in the N. subflava group in the work by Bennett et al. (2012), whereas we found that one strain originally identified as N. sicca and six strains originally identified as N. mucosa clustered into that group. The reason may be that six N. mucosa strains, most of which sequences were uploaded to GenBank after 2012, analyzed in our research, were not enrolled by Bennett et al. (2012). According to our results, some originally misidentified N. mucosa and N. sicca species seem as variants of N. subflava. The N. mucosa and N. subflava groups of the phylogenetic tree also clustered in the ANIb heatmap, which revealed ANIb analysis verified our initial conclusion.

The genus Neisseria includes the two pathogenic species, N. meningitidis and N. gonorrhoeae; the remaining species are opportunistic pathogens (Caugant and Brynildsrud, 2020). Compared with the opportunistic pathogen Neisseria species, N. meningitidis causes significant morbidity and mortality (Wang et al., 2019). Notably, one strain originally identified as N. mucosa was reclassified as N. meningitidis. It reveals some GenBank genomes are clearly not curated or checked, creating taxonomic errors. We found that strain SAMN18451419 from a patient with congenital heart disease was misidentified by VITEK MS as N. sicca. It indicates that both MS and GenBank databases require revision of Neisseria classification.

Conclusion

We offered a detailed and well-supported description of the phylogenetic relationship between the (erroneously) originally classified N. mucosa and N. sicca strains, as confirmed by ANIb analysis. The original N. mucosa and N. sicca strains were reclassified into the N. mucosa group and N. subflava group via high-resolution genomic taxonomy. The GenBank and MALDI-TOF MS databases thus require correction. In addition, the classification strategy for originally identified N. mucosa and N. sicca strains in GenBank is supposed to be updated with the progressive development of genomic analysis approaches.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repositories and accession numbers can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.

Ethics Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved [2021IIT026 (fast track)] by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine. The patient provided the written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author Contributions

YZ and BZ designed the research. YJ, HX, YZ, and BZ analyzed and collected data, and wrote the manuscript. QY, BG, ZW, TW, YL, and XY collected the clinical data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by National Key R&D Program of China (2021YFC2301900-2021YFC2301901), the Zhejiang Education Department 2020 Special Project Against COVID-19-Zhejiang University (no. 94) and Independent Task of State Key Laboratory for Diagnosis and Treatment of Infectious Diseases (2021).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2021.780183/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

- ^ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/assembly/?term=Neisseria

- ^ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/CP072524.1/

- ^ http://www.mgc.ac.cn/VFs/main.htm

- ^ https://pubmlst.org/neisseria/

- ^ https://rast.Nmpdr.org

- ^ https://github.com/deminu/Roary

- ^ https://itol.embl.de/

- ^ https://github.com/widdowquinn/pyani

- ^ https://pubmlst.org/bigsdb?db=pubmlst_neisseria_seqdef&page=sequenceQuery

References

Altschul, S. F., Madden, T. L., Schäffer, A. A., Zhang, J., Zhang, Z., Miller, W., et al. (1997). Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389

Bennett, J. S., Jolley, K. A., Earle, S. G., Corton, C., Bentley, S. D., Parkhill, J., et al. (2012). A genomic approach to bacterial taxonomy: an examination and proposed reclassification of species within the genus Neisseria. Microbiology (Reading) 158, 1570–1580. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.056077-0

Brodie, E., Adler, J. L., and Daly, A. K. (1971). Bacterial endocarditis due to an unusual species of encapsulated Neisseria. Neisseria mucosa endocarditis. Am. J. Dis. Child 122, 433–437. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1971.02110050103015

Caugant, D. A., and Brynildsrud, O. B. (2020). Neisseria meningitidis: using genomics to understand diversity, evolution and pathogenesis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 18, 84–96. doi: 10.1038/s41579-019-0282-6

Diallo, K., MacLennan, J., Harrison, O. B., Msefula, C., Sow, S. O., Daugla, D. M., et al. (2019). Genomic characterization of novel Neisseria species. Sci. Rep. 9:13742. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-50203-2

Humphries, R., Bobenchik, A. M., Hindler, J. A., and Schuetz, A. N. (2021). Overview of changes to the clinical and laboratory standards institute performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing, M100, 31(st) Edition. J. Clin. Microbiol. 59:e0021321. doi: 10.1128/jcm.00213-21

Jolley, K. A., Bray, J. E., and Maiden, M. C. J. (2018). Open-access bacterial population genomics: BIGSdb software, the PubMLST.org website and their applications. Wellcome Open Res. 3:124. doi: 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.14826.1

Konstantinidis, K. T., and Tiedje, J. M. (2005). Genomic insights that advance the species definition for prokaryotes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 2567–2572. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409727102

Kumar, S., Stecher, G., Li, M., Knyaz, C., and Tamura, K. (2018). MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 35, 1547–1549. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msy096

Mechergui, A., Achour, W., and Hassen, A. B. (2014). Intraspecific 16S rRNA gene diversity among clinical isolates of Neisseria species. Apmis 122, 437–442. doi: 10.1111/apm.12164

Paul, B., Dixit, G., Murali, T. S., and Satyamoorthy, K. (2019). Genome-based taxonomic classification. Genome 62, 45–52. doi: 10.1139/gen-2018-0072

Staley, J. T. (2006). The bacterial species dilemma and the genomic-phylogenetic species concept. Philos. Trans. R Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 361, 1899–1909. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2006.1914

Tønjum, T. (2005). “Genus I. Neisseria,” in Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, eds G. M. Garrity, D. J. Brenner, N. R. Krieg, and J. R. Staley (New York, NY: Springer-Verlag), 777–798.

Wang, B., Santoreneos, R., Giles, L., Haji Ali Afzali, H., and Marshall, H. (2019). Case fatality rates of invasive meningococcal disease by serogroup and age: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccine 37, 2768–2782. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.04.020

Keywords: Neisseria mucosa, Neisseria sicca, Neisseria subflava, reclassification, whole-genome sequencing, average nucleotide identity blast, phylogenetic analysis

Citation: Jin Y, Xu H, Yao Q, Gu B, Wang Z, Wang T, Yu X, Lu Y, Zheng B and Zhang Y (2022) Confirmation of the Need for Reclassification of Neisseria mucosa and Neisseria sicca Using Average Nucleotide Identity Blast and Phylogenetic Analysis of Whole-Genome Sequencing: Hinted by Clinical Misclassification of a Neisseria mucosa Strain. Front. Microbiol. 12:780183. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.780183

Received: 20 September 2021; Accepted: 24 November 2021;

Published: 21 February 2022.

Edited by:

Daniel Yero, Universitat Autónoma de Barcelona, SpainReviewed by:

Cristina Hansen, University of Alaska Fairbanks, United StatesKanny Diallo, Centre Suisse de Recherches Scientifiques en Côte d’Ivoire, Côte d’Ivoire

Copyright © 2022 Jin, Xu, Yao, Gu, Wang, Wang, Yu, Lu, Zheng and Zhang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Beiwen Zheng, emhlbmdid0B6anUuZWR1LmNu; Yimin Zhang, MTMwNzAyMEB6anUuZWR1LmNu

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Yanqi Jin1†

Yanqi Jin1† Hao Xu

Hao Xu Zhouhan Wang

Zhouhan Wang Beiwen Zheng

Beiwen Zheng Yimin Zhang

Yimin Zhang