94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Microbiol. , 10 June 2021

Sec. Microbiotechnology

Volume 12 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2021.696096

This article is part of the Research Topic Marine Microorganisms and Their Enzymes with Biotechnological Application View all 13 articles

Hyaluronic acid (HA) is a negatively charged and linear polysaccharide existing in the tissues and body fluids of all vertebrates. Some pathogenic bacteria target hyaluronic acid for adhesion and/or infection to host cells. Vibrio alginolyticus is an opportunistic pathogen related to infections of humans and marine animals, and the hyaluronic acid-degrading potential of Vibrio spp. has been well-demonstrated. However, little is known about how Vibrio spp. utilize hyaluronic acid. In this study, a marine bacterium V. alginolyticus LWW-9 capable of degrading hyaluronic acid has been isolated. Genetic and bioinformatic analysis showed that V. alginolyticus LWW-9 harbors a gene cluster involved in the degradation, transport, and metabolism of hyaluronic acid. Two novel PL8 family hyaluronate lyases, VaHly8A and VaHly8B, are the key enzymes for the degradation of hyaluronic acid. VaHly8A and VaHly8B have distinct biochemical properties, reflecting the adaptation of the strain to the changing parameters of the aquatic habitats and hosts. Based on genomic and functional analysis, we propose a model for the complete degradation of hyaluronic acid by V. alginolyticus LWW-9. Overall, our study expands our knowledge of the HA utilization paradigm within the Proteobacteria, and the two novel hyaluronate lyases are excellent candidates for industrial applications.

Animal cells are in close interaction with extracellular matrices (ECM), which function as a physical scaffold for organs and tissues, regulate various cellular functions and maintain homeostasis (Theocharis et al., 2016). Hyaluronic acid (HA), a significant constituent of ECM, is a linear polysaccharide consisting of repeating units of glucuronic acid and N-acetylglucosamine via a β-1,4 linkage. HA is involved in various physiological and pathological processes of the biological system, such as cell migration, adhesion, growth and differentiation, embryogenesis, cancer, inflammation, and damage repair (Volpi et al., 2009). Due to its excellent physicochemical characteristics, HA has a variety of applications in the pharmaceutical industry, such as orthopedics, ophthalmology, and aesthetic dermatology (Sudha and Rose, 2014).

Some pathogenic bacteria, such as streptococci and streptobacillus, produce extracellular or cell-surface hyaluronate lyase to depolymerize HA, facilitating the invasion of the host (Li and Jedrzejas, 2001; Oiki et al., 2017). Hyaluronate lyases degrade HA by β-elimination mechanism, generating unsaturated disaccharides with a C4-C5 double bond at the non-reducing end (Wang et al., 2017). Hyaluronate lyases are categorized into four polysaccharide lyase (PL) families, PL8, PL16, PL30, and PL33, in the Carbohydrate-Active Enzymes (CAZy) database according to primary structures (Lombard et al., 2014).

The utilization of HA requires multiple proteins, such as PLs, glycoside hydrolases (GHs), sugar transporters, and transcriptional factors. These genes often cluster in a polysaccharide utilization loci (PUL), orchestrating sensing, enzymatic digestion, transport, and metabolism of a specific polysaccharide (Martens et al., 2009; Grondin et al., 2017). There are some reports on the polysaccharide utilization locus of hyaluronic acid (PULHA) in Firmicutes and Fusobacteria, but few reports on the PULHA in Proteobacteria (Kawai et al., 2018; Oiki et al., 2019a,b). Although several hyaluronate lyases of Proteobacteria have been characterized in detail, the pathway for HA utilization in Proteobacteria remains largely opaque (Han et al., 2014; Peng et al., 2018).

Members of the genus Vibrio are pathogenic bacteria that cause serious infections to aquatic animals and humans, called vibriosis (Austin, 2010). Vibriosis is one of the most common bacterial diseases posing a threat to cultured fish, shellfish, and shrimp, which has a negative effect on the development of the global aquaculture industry (Ina-Salwany et al., 2019). Vibrio infections occur when humans expose to contaminated water or consume raw or undercooked contaminated seafood, causing many diseases, such as gastroenteritis, and wound infections and septicemia (Dechet et al., 2008). Vibrio strains could degrade hyaluronic acid to facilitate host invasion; however, little is known about how they utilize hyaluronic acid.

In this study, we isolated a hyaluronate lyase-producing bacterium, Vibrio alginolyticus strain LWW-9. A PULHA was found in the draft genome of V. alginolyticus LWW-9 by genome analysis. In particular, two novel hyaluronate lyases in PULHA, VaHly8A, and VaHly8B, were characterized. VaHly8A and VaHly8B showed distinct biochemical properties, which revealed their adaption to the living environment. Finally, we provided a model for how V. alginolyticus strain LWW-9 utilizes the HA. These results presented here not merely extend our understanding of the HA utilization paradigm within the Proteobacteria but also may contribute to the elucidation of bacterial physiology and pathogenicity.

Hyaluronic acid was obtained from Macklin (Shanghai, China). The pET-28a (+) plasmid and Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) were obtained from Takara (Dalian, China). DNA polymerase was obtained from Vazyme (Nanjing, China). Restriction enzymes and T4 DNA ligase were purchased from Takara (Dalian, China). Pageruler unstained protein ladder was obtained from Thermo Scientific (Wilmington, United States). All other chemicals were purchased from Sinopharm (Beijing, China).

Seawater was collected from Zhanqiao, Qingdao, China. A selective medium supplemented with HA as the sole carbon source was used to isolate hyaluronate lyase-producing bacteria from seawater. The medium consisted of 0.3% (w/v) KH2PO4, 0.7% (w/v) K2HPO4·3H2O, 0.2% (w/v; NH4)2SO4, 0.01% (w/v) MgSO4, 0.01% (w/v) FeSO4·7H2O, 3% NaCl, 0.05% (w/v) HA, and 1.5% (w/v) agar (pH 7.0). After microorganisms had grown at 25°C for 48 h, the plates were soaked with Gram’s iodine for 1 min (Patil and Chaudhari, 2017). Clones with distinct clearance zones were detected as HA-degrading strains. They were picked up and purified on the fresh selective medium plates for three times. The pure cultured strains were incubated at 25°C and 160 r/min for 48 h in 100 ml marine broth 2216, and the hyaluronate lyase activity in the culture supernatant was determined. The strain LWW-9 that exhibited the highest hyaluronate lyase activity was obtained and used in the following experiment.

The 16S rDNA of strain LWW-9 was amplified by PCR using the universal primers 27F (5'-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3') and 1492R (5'-TACGGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3'). A colony of strain LWW-9 was used as the template. The PCR product was purified, and sequenced by Ruibiotech Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). The sequence analysis was conducted using Blast program1 to search for sequences with high identity in GenBank database. The phylogenetic analysis was performed by MEGA X using the neighbor-joining method (Kumar et al., 2018).

The genomic DNA of strain LWW-9 was prepared using Tianamp bacteria DNA kit (Tiangen, China). The draft genome of strain LWW-9 was sequenced using Roche 454 FLX Titanium technologies (Margulies et al., 2005). The genome annotation was performed online in the Rapid Annotation using Subsystem Technology (RAST) server.2 Cazymes were further identified using pfam (Finn et al., 2014) and dbCAN Hidden Markov model (Zhang et al., 2018). Homologs searches of predicted protein sequences were carried out using Blatsp against NCBI PDB and nr databases. The gene cluster involved in the utilization of HA was identified as a potential PULHA. If genes adjacent to hyaluronate lyases encoded proteins dedicated to the utilization of HA, including Cazymes, sugar transporters, and transcription factors, the boundary of PULHA was extended. When five continuous genes were not annotated as HA utilization proteins, the last gene with related function was regarded as the putative boundary of PULHA.

The online Blastp algorithm was used to perform similarity searches against NCBI PDB and nr databases. Protein modules and domains were analyzed using Conserved Domain (CD) Search.3 A neighbor-joining tree based on the protein sequence alignment was constructed using MEGA X (Kumar et al., 2018). Amino acid alignment with other enzymes of the PL8 family was carried out using ESPrit 3.0 (Robert and Gouet, 2014). The physical and chemical parameters of proteins, such as molecular weight (Mw) and isoelectric point (pI) were predicted by the ProtParam tool on the ExPASy server.4 The existence and pattern of signal peptides were identified using SignalP 5.0 server.5

The vahly8B and vahly8B were amplified by PCR using the genomic DNA of strain LWW-9 as the template. The primers for VaHly8A were 5'-GGAATTCCATATGAATAAATTTAATATTTCAA-3' and 5'-CCGCTCGAGTTCCTTAATGCGTTTAAC-3'. The primers for VaHly8B were 5'-GGAATTCCATATGAAACCTCTGAAACTCAC-3' and 5'-CCGCTCGAGCTCTTTTACCAAAGAGAAGG-3'. The PCR products were recovered from the agarose gel, digested with Nde I and Xho I, and ligated into the expression plasmid pET-28a(+). The recombinant plasmids, pET28a(+)-VaHly8A and pET28a(+)-VaHly8B, were transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3) cells, respectively.

Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) cells harboring pET28a(+)-VaHly8A and pET28a(+)-VaHly8B were incubated in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium at 37°C until the OD600 reached 0.4–0.6, then induced with 0.02 mM isopropyl β-D-thiogalactoside at 18°C for 24 h. The cells were harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in 20 mM Na2HPO4-NaH2PO4 buffer (pH 7.4) containing 500 mM NaCl, and disrupted by sonication. The cell lysate was centrifuged, and the recombinant hyaluronate lyase with N-terminal and C-terminal (His)6 tags was purified from the supernatant by Histrap column (GE Healthcare, United States). The purity and Mw of the proteins were determined by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) on a 10% (w/v) resolving gel. Protein concentration was measured by the BCA protein assay kit (NCM Biotech, China).

The enzyme activity was measured in a 1 ml reaction system under the optimal reaction condition. First, 0.1 ml enzyme (0.18 U/ml) was added to 0.9 ml 0.2% (w/v) HA substrate solution. After incubation for 10 min at the optimal temperature, the reaction was terminated by boiling for 10 min, and then the absorbance of the solution was measured at 232 nm by a UH5300 UV visible spectrophotometer (HITACHI, Japan). One unit of enzyme activity was defined as the amount of the protein required to produce 1 μmol unsaturated oligosaccharides using the molecular extinction coefficient value of 5,500 M−1 cm−1 at 232 nm (Lin et al., 1994).

The optimal temperature was determined in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.05) at different temperatures ranging from 0 to 70°C. The optimal pH was measured in the following buffers with various pH values: 50 mM Na2HPO4-Citrate buffer (pH 3.0–8.0), 50 mM NaH2PO4-Na2HPO4 buffer (pH 6.0–8.0), 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.05–8.95), and 50 mM Glycine-NaOH buffer (pH 8.6–10.6). To determine the thermostability of the enzyme, it was incubated for 1 h under temperatures ranging from 0 to 50°C, and the residual activities were determined at the optimal temperature and pH. To determine the pH stability of the enzyme, it was incubated for 6 h in buffers with varying pH values from 3.0 to 10.6 at 0°C, and the residual activities were determined at the optimal temperature and pH. The effect of NaCl was investigated by examining the enzyme activities in Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.05) containing various concentrations of NaCl ranging from 0 to 1.0 M at the optimal temperature and pH. The effects of metal ions and surfactants were investigated by examining the enzyme activities in Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.05) containing various compounds (1 mM) at the optimal temperature and pH.

To investigate the kinetic parameters of VaHly8A and VaHly8B, 0.1–8.0 mg/ml HA were used as the substrate. 0.1 ml enzyme (0.36 U/ml) was added to 0.9 ml substrate solution. After incubation at the optimal temperature for 3 min, the absorbance of the solution was measured at 232 nm. Km and Vmax values were determined using the Michaelis-Menten equation and the curve fitting program by non-linear regression analysis using Graphpad Prism 8.

To investigate the degradation pattern and final product of HA by VaHly8A and VaHly8B, 0.2% (w/v) HA was digested by the purified enzyme (0.15 U/ml) at 20°C for VaHly8A and 30°C for VaHly8B. The reaction mixture was incubated for different time intervals ranging from 0 to 12 h. Samples were inactivated at 100°C for 10 min and centrifuged at 12,000 r/min for 10 min. The supernatant was then analyzed on a Superdex™ Peptide 10/300 GL column (GE Health, United States) by monitoring the absorbance at 232 nm. The mobile phase and flow rate were 0.2 M ammonium bicarbonate and 0.2 ml/min, respectively.

The exact Mw of final product was detected by negative ion electrospray ionization-mass spectroscopy (ESI-MS, Thermo Fisher Scientific, United States) with the mass acquisition range of 100–2,000. The ESI-MS analysis was carried out under the following conditions: sheath gas flow rate, 10 arb; spray voltage, 2.5 kV; tube lens, 35 V; capillary voltage, 16 V; and capillary temperature, 275°C.

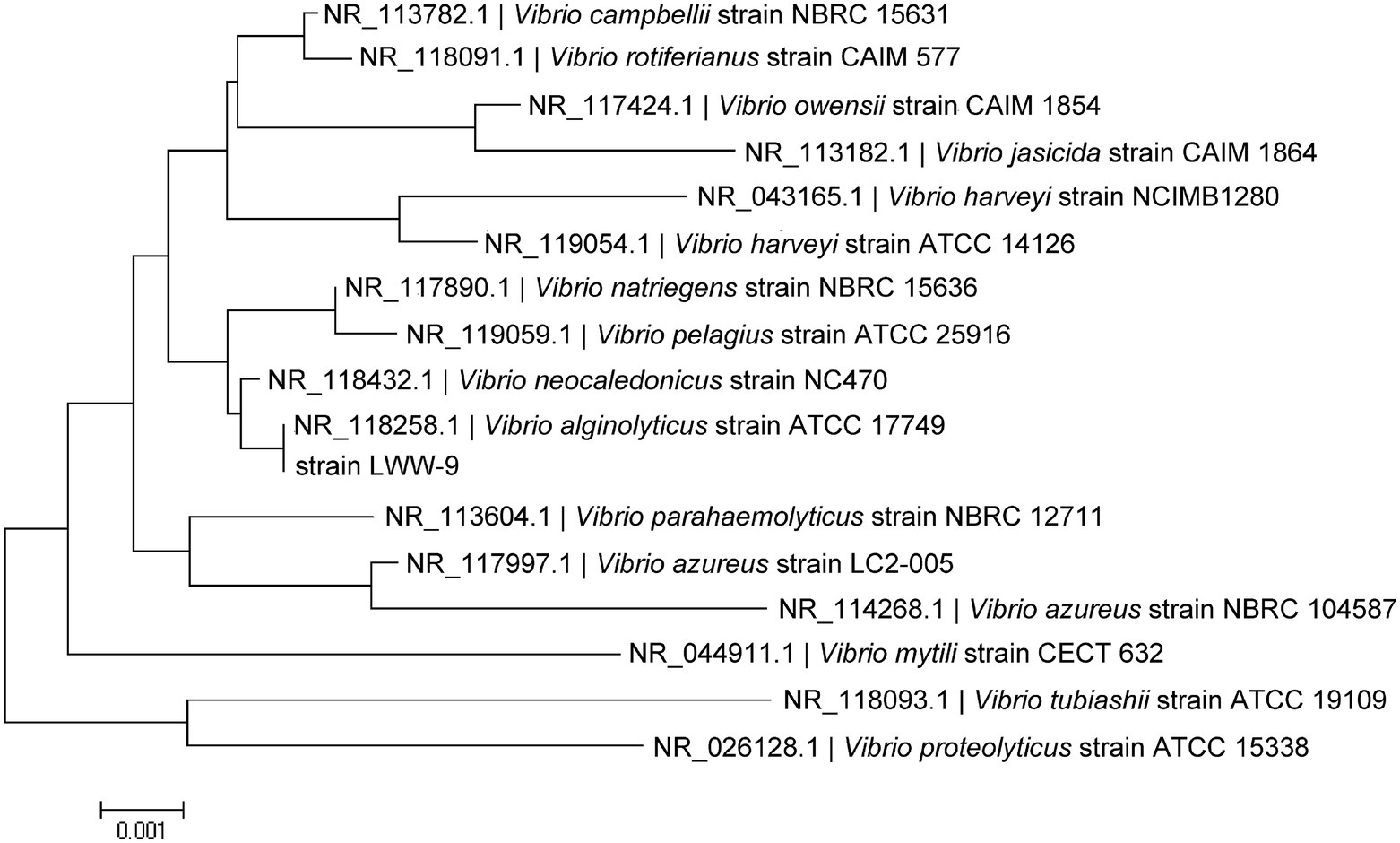

The 16S rDNA of strain LWW-9 was sequenced and submitted to GenBank under the accession number MW396717. The Blast search analysis against GenBank database revealed that strain LWW-9 showed 99% identity with multiple Vibrio strains. Vibrio alginolyticus strain Va-X15 (MH298577.1) showed the highest identity of 99.23%. Sixteen type strains in Vibrio were selected for phylogenetic analysis, and the result showed that strain LWW-9 was closest to V. alginolyticus strain ATCC 17749 (NR_118258.1) in the phylogenetic tree (Figure 1). Therefore, strain LWW-9 was identified as V. alginolyticus.

Figure 1. Phylogenetic tree of strain LWW-9 based on 16S rRNA sequences. The phylogenetic tree was generated by MEGA X using the neighbor-joining method.

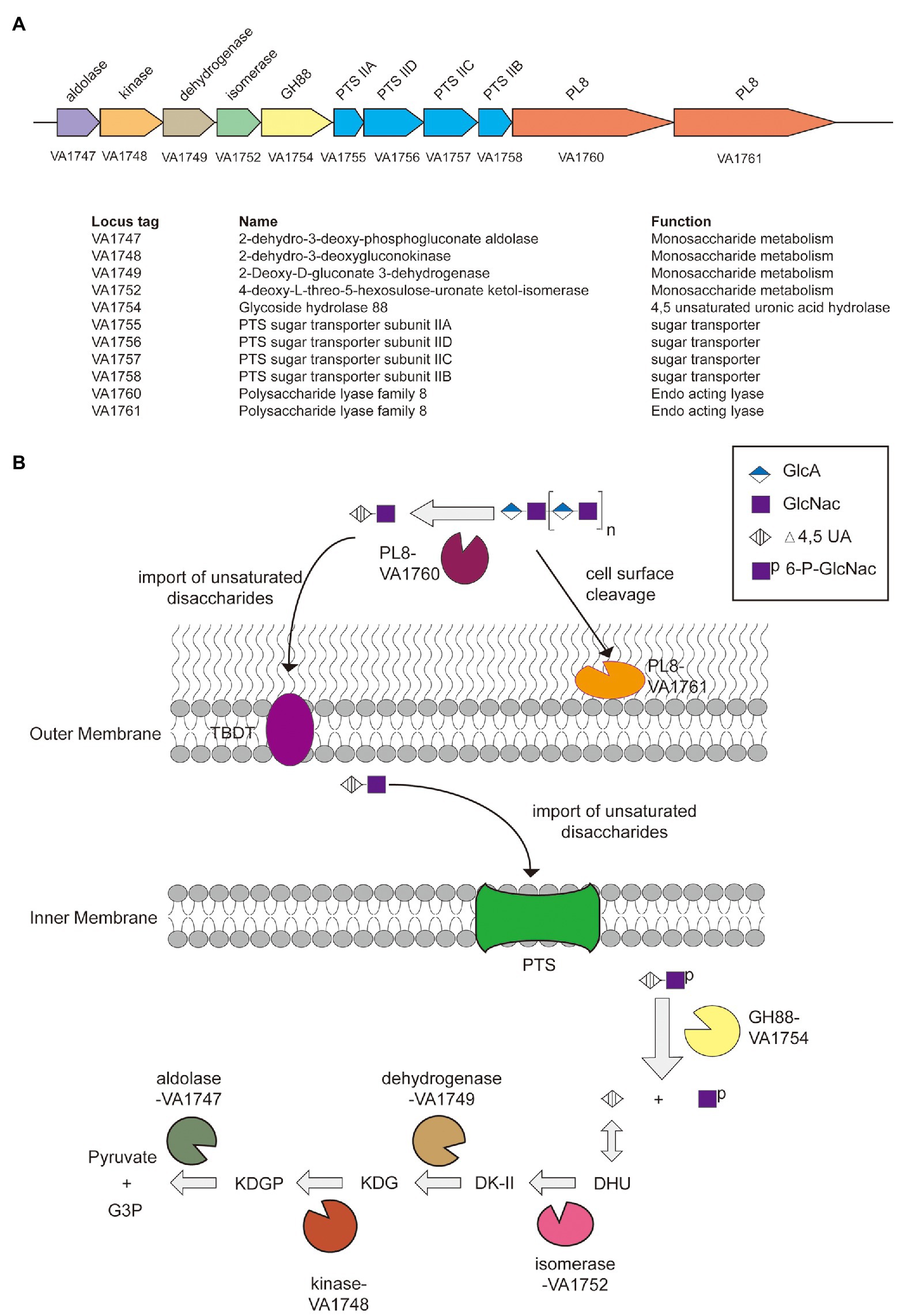

Genes related to the utilization of HA in V. alginolyticus LWW-9 were clustered in a ~19,600 bp genomic region, which suggested that this genetic cluster could be a PULHA. The PULHA encodes two PL8 family hyaluronate lyases (VN1760 and VN1761), one GH88 family unsaturated glucuronyl hydrolase (VN1754), four enzymes involved in the metabolism of HA monosaccharides (VN1747, VN1748, VN1749, and VN1752), and one sugar transporter glucose phosphotransferase system (PTS) composed of four components (VN1755, VN1756, VN1757, and VN1758; Figure 2A). Despite the lack of susC/susD pairs in PULHA, TonB-dependent transporter (TBDT) encoded elsewhere in the genome may enable the oligosaccharides sensing and transport, similar to the SusC/SusD system of Bacteroides (Blanvillain et al., 2007).

Figure 2. The paradigm of hyaluronic acid (HA) utilization by Vibrio alginolyticus LWW-9. (A) Predicted polysaccharide utilization locus of hyaluronic acid (PULHA) in V. alginolyticus LWW-9. (B) Schematic of the cellular location, activity, and specificity of the PULHA-encoded enzymes. DHU, 4-deoxy-L-threo-5-hexosulose-uronate; DK-II, 3-deoxy-D-glycero-2,5-hexodiulosonate; KDG, 2-keto-3-deoxy-D-gluconate; KDGP, 2-keto-3-deoxy-6-phosphogluconate; and G3P, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate.

A pathway for the metabolism of HA in V. alginolyticus LWW-9 has been proposed (Figure 2B). HA is degraded to unsaturated disaccharides by extracellular and cell-surface hyaluronate lyases. Unsaturated disaccharides are first transported to the periplasm by TBDT and then imported to the cytoplasm by PTS. They are degraded to unsaturated uronates and N-acetyl-D-glucosamines by GH88 through hydrolysis of β-1,4 linkages in the cytoplasm. Unsaturated uronates are converted to 4-deoxy-L-threo-5-hexosulose-uronate (DHU) by nonenzymatic reactions. DHU was ultimately metabolized to pyruvate and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate by consecutive reactions of isomerase, dehydrogenase, kinase, and aldolase (Maruyama et al., 2015).

The putative gene vahly8A was 2,385 bp in length and encoded VaHly8A consisting of 794 amino acid residues. The theoretical Mw and pI of VaHly8A are 88.1 kDa and 5.40, respectively. According to SignalP 5.0, VaHly8A has a type I signal peptide of 26 amino acid residues at its N-terminus. CD Search indicated that VaHly8A contained a Lyase_8 module (Trp49-Ile381) and a GAG lyase superfamily module (Phe42-Pro740). Blastp searches showed that VaHly8A shared the identity with HCLase (39%) from Vibrio sp. FC509 (Han et al., 2014), HAase-B (31%) from Bacillus sp. A50 (Guo et al., 2014), and XalA (30%) from Paenibacillus alginolyticus XL-1 (Ruijssenaars et al., 1999).

The putative gene vahly8B was 2,373 bp in length and encoded VaHly8B composed of 790 amino acid residues. The theoretical Mw and pI of VaHly8B are 86.5 kDa and 4.90, respectively. According to SignalP 5.0, VaHly8B has a type II signal peptide of 19 amino acid residues at its N-terminus. CD Search indicated that VaHly8A contained a Lyase_8 module (Trp54-Lys373) and a GAG_lyase superfamily module (Arg51-Ser736). Balstp searches showed that VaHly8B shared the identity with HCLase (41%) from Vibrio sp. FC509 (Han et al., 2014), XalA (33%) from Paenibacillus alginolyticus XL-1 (Ruijssenaars et al., 1999), and HAase-B (32%) from Bacillus sp. A50 (Guo et al., 2014).

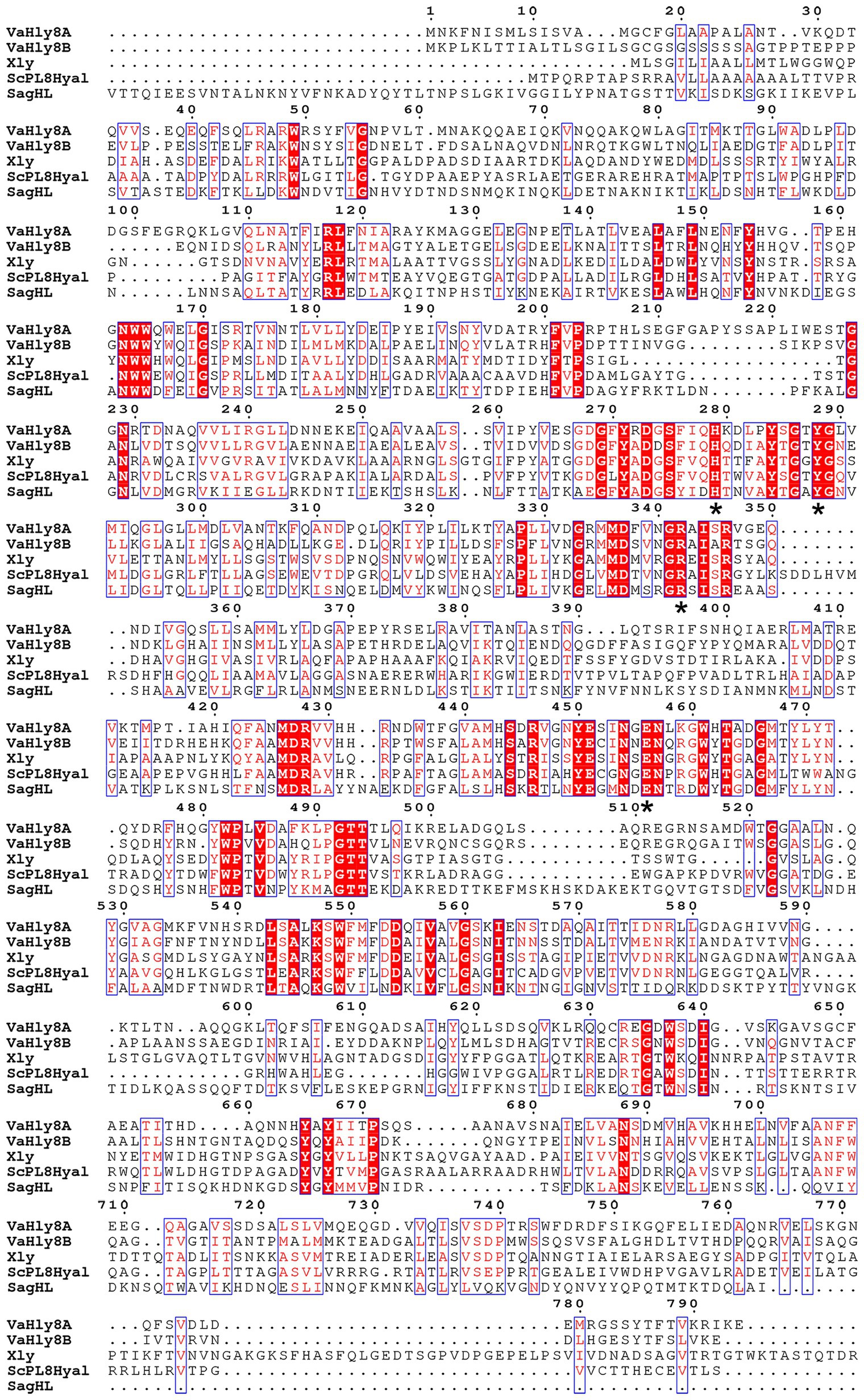

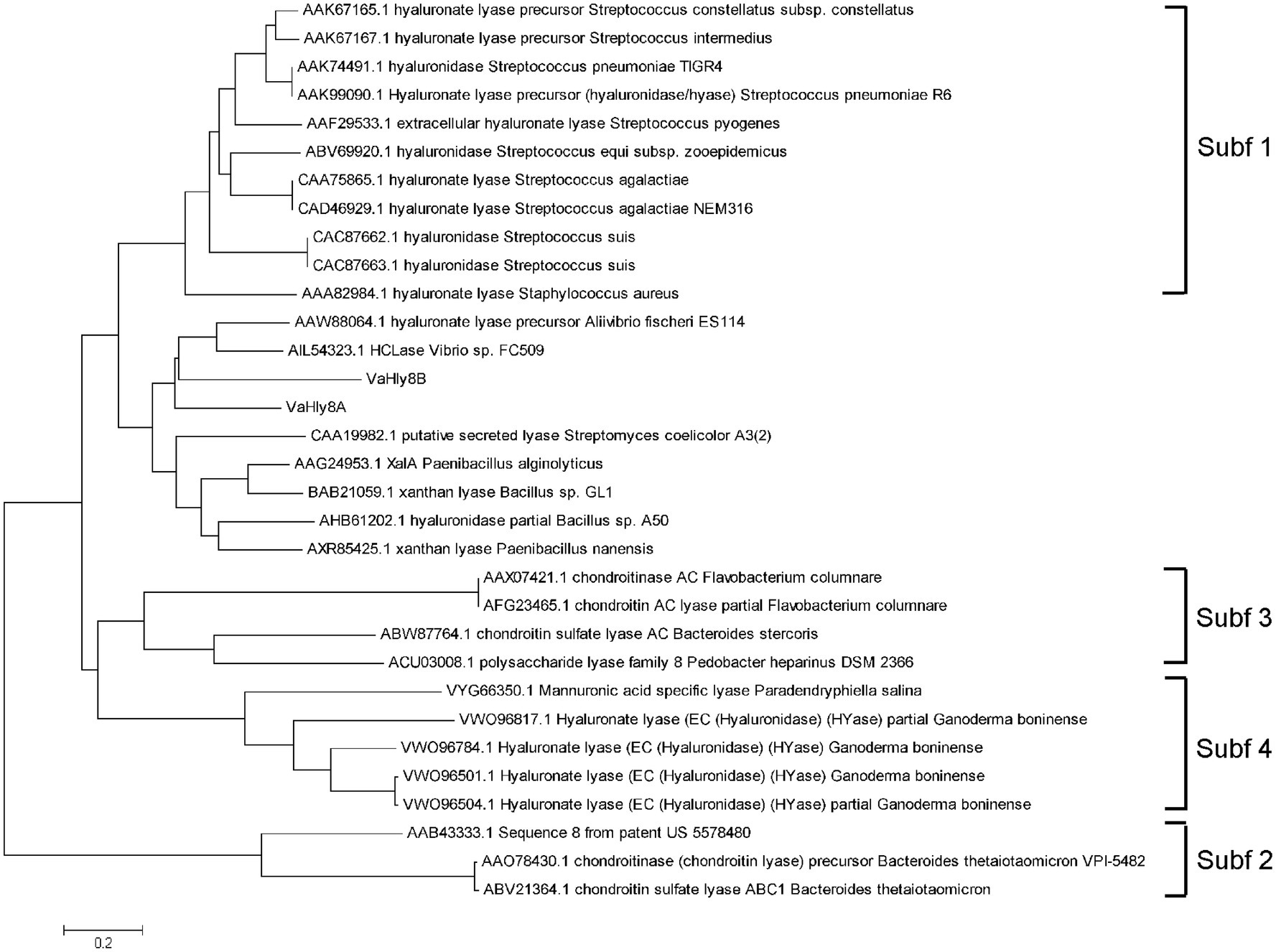

The amino acid alignment of VaHly8A, VaHly8B, and identified PL8 family enzymes showed that VaHly8A and VaHly8B contained the conserved catalytic residues of PL8 family (His279, Tyr288, Arg342, and Glu456 in VaHly8A; His271, Tyr280, Arg333, and Glu451 in VaHly8B; Figure 3). Phylogenetic tree was constructed and the result (Figure 4) revealed that VaHly8A and VaHly8B were new members of the PL8 family.

Figure 3. Protein sequence alignment of VaHly8A and VaHly8B to the identified enzymes of the PL8 family. Red background represents the same amino acid residues and blue frames indicate amino acid residues with identity > 70%. The critical catalytic residues were highlighted by asterisks below them. Xly, from Bacillus sp. GL1, Genbank: BAB21059.1; ScPL8Hyl, from Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2), Genbank: CAA19982.1; SagHL, from Streptococcus agalactiae NEM316, Genbank: CAD46929.1.

Figure 4. Phylogenetic tree of VaHly8A, VaHly8B and other enzymes of the PL8 family. The phylogenetic tree was constructed by MEGA X using the neighbor-joining method.

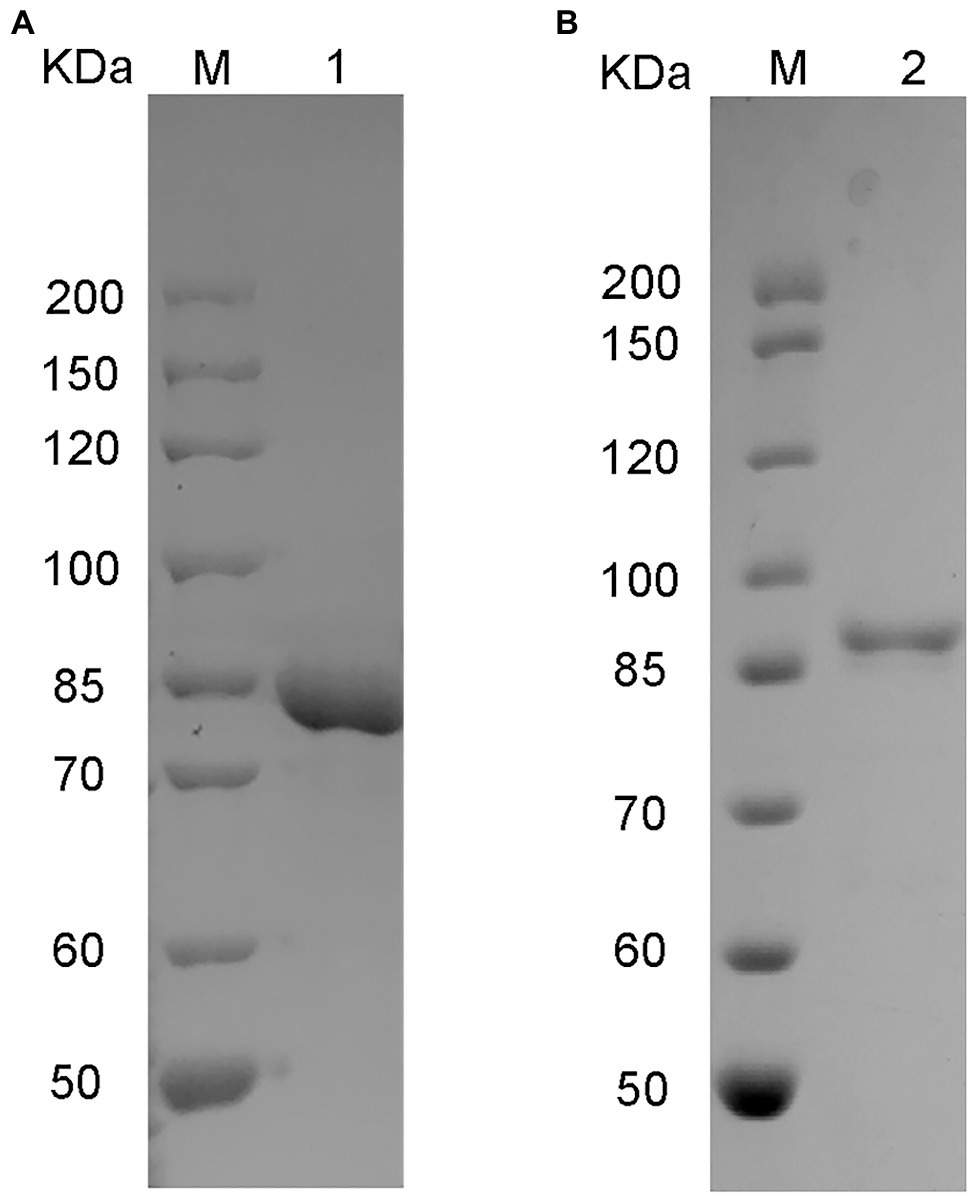

The genes vahly8A and vahly8B were heterologously expressed in pET-28a (+)/E. coli BL21(DE3) system and successfully purified by Ni-affinity chromatography. SDS-PAGE showed that VaHly8A (Figure 5A) and VaHly8B (Figure 5B) purified to homogeneity with Mw of approximately 83 and 87 kDa, respectively, which had no significant difference with the predicted Mw. The specific activity of VaHly8A and VaHly8B were 223.65 and 26.38 U/mg, respectively.

Figure 5. Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) of purified recombinant VaHly8A (A) and VaHly8B (B). Lane M, unstained protein molecular weight marker; lane 1, purified VaHly8A; and lane 2, purified VaHly8B.

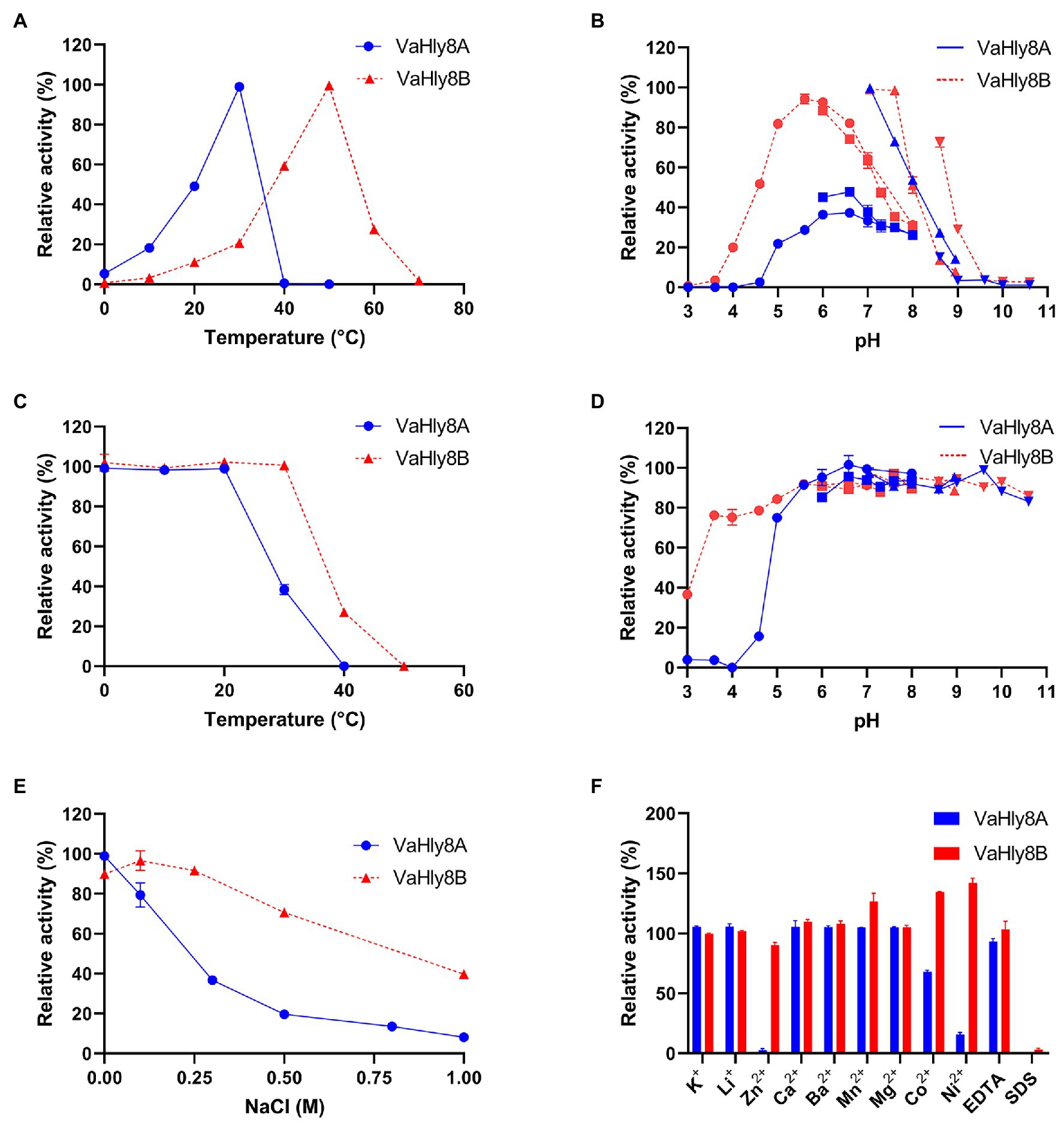

VaHly8A exhibited the maximal activity at 30°C (Figure 6A) and maintained over 90% original activity after incubation at temperatures from 0 to 20°C for 1 h (Figure 6C). VaHly8B showed the highest activity at 50°C (Figure 6A) and retained over 90% original activity after incubation at temperatures from 0 to 30°C for 1 h (Figure 6C). Compared with VaHly8B, VaHly8A had a lower optimal temperature and thermostability. The optimal pH of VaHly8A and VaHly8B was 7.05 in Tris-HCl buffer (Figure 6B). VaHly8A retained over 70% original activity after incubation at pH ranging from 5.0 to 10.6 for 6 h (Figure 6D). VaHly8B maintained over 70% original activity after incubation at pH ranging from 3.6 to 10.6 for 6 h. Despite the same optimal pH of VaHly8A and VaHly8B, VaHly8B showed higher activity and stability than VaHly8A under acidic conditions. The activity of VaHly8A was inhibited in the presence of NaCl (Figure 6E). However, VaHly8B is more tolerant of NaCl than VaHly8A, and the activity of VaHly8B reached the maximum when the concentration of NaCl was 100 mM. Mn2+, Co2+, and Ni2+ showed significantly stimulating effects on VaHly8B with 126.8, 134.5, and 142.0% of relative activity, respectively (Figure 6F). The activity of VaHly8A was not obviously enhanced by these metal ions, but inhibited by Co2+ and Ni2+. The activities of both VaHly8A and VaHly8B were strongly inhibited by SDS. Besides, the activity of VaHly8A was strongly inhibited by Zn2+. Other tested chemicals had no significant effect on both VaHly8A and VaHly8B. Overall, VaHly8B had higher resistance to metal ions than VaHly8A. As shown in Table 1, the Km and kcat of VaHly8A toward HA were 1.21 μM and 477.93 s−1, respectively. The Km and kcat of VaHly8B toward HA were 0.78 μM and 54.59 s−1, respectively.

Figure 6. Biochemical properties of the hyaluronate lyases VaHly8A and VaHly8B. (A) Effect of temperature. The enzyme activities of VaHly8A (1.69 μg/ml) and VaHly8B (9.76 μg/ml) were measured at 0–70°C. The highest specific activity of VaHly8A (106.70 U/mg) at 30°C and VaHly8B (17.57 U/mg) at 50°C were set as 100%. (B) Effect of pH. The enzyme activities of VaHly8A (1.13 μg/ml) and VaHly8B (6.62 μg/ml) were measured in 50 mM buffers, including Na2HPO4-Citrate buffer (pH 3.0–8.0; filled circles), NaH2PO4-Na2HPO4 buffer (pH 6.0–8.0; filled squares), Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.05–8.95; positive triangles), and Glycine-NaOH buffer (pH 8.6–10.6; inverted triangles). The highest specific activity of VaHly8A (223.65 U/mg) and VaHly8B (23.70 U/mg) in Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.05) was set as 100%. (C) Thermostability of VaHly8A and VaHly8B. The enzymes were incubated for 1 h at different temperatures (0–50°C), and the residual activities were measured at 30°C for VaHly8A (5.83 μg/ml) and 50°C for VaHly8B (55.50 μg/ml). The initial specific activity of VaHly8A (223.65 U/mg) and VaHly8B (23.70 U/mg) were set as 100%. (D) The pH stability of VaHly8A and VaHly8B. The enzymes were incubated in above buffers (pH 3.0–10.60) for 6 h at 0°C, and the residual activities were measured at 30°C for VaHly8A (10.73 μg/ml) and 50°C for VaHly8B (61.75 μg/ml). The initial specific activity of VaHly8A (223.65 U/mg) and VaHly8B (23.70 U/mg) were set as 100%. (E) Effect of NaCl. The enzyme activities were measured in Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.05) containing different concentrations of NaCl ranging from 0 to 1.0 M at 30°C for VaHly8A (0.67 μg/ml) and 50°C for VaHly8B (4.39 μg/ml). The highest specific activity of VaHly8A (223.65 U/mg) without NaCl and VaHly8B (26.38 U/mg) in the presence of 0.1 M NaCl were set as 100%. (F) Effects of various compounds. The enzyme activities were measured in Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.05) containing 1 mM various compounds at 30°C for VaHly8A (1.06 μg/ml) and 50°C for VaHly8B (3.60 μg/ml). The specific activity of VaHly8A (223.65 U/mg) and VaHly8B (26.38 U/mg) without tested compounds was set as 100%. Values represent the mean of three replicates ± SD.

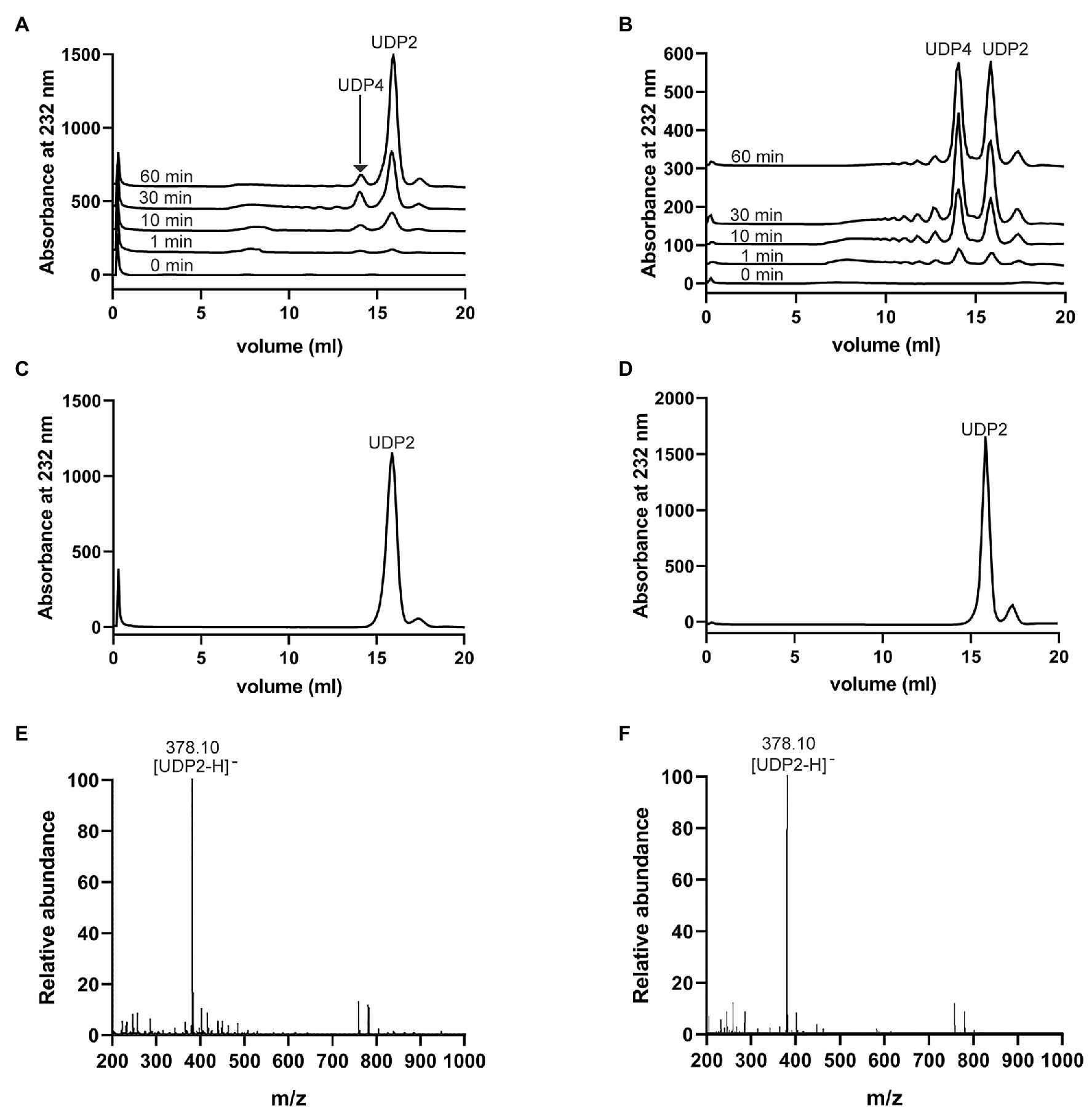

To investigate the degradation patterns of VaHly8A and VaHly8B, reaction products incubated for different time intervals were analyzed by the Superdex™ peptide 10/300 gel filtration column. The appearance of unsaturated oligosaccharides was detected using the absorbance at 232 nm. At the beginning of the reaction, products with high degree of polymerization were produced (Figures 7A,B). As the reaction continues, smaller oligomers continuously accumulated. The HA was completely digested after 6 h by VaHly8A and 12 h by VaHly8B (Figures 7C,D). These results indicated that both VaHly8A and VaHly8B acted in an endolytic manner.

Figure 7. Action modes and final products of VaHly8A and VaHly8B. (A) Time-course treatment of HA using VaHly8A at 30°C. (B) Time-course treatment of HA using VaHly8B at 50°C. Analysis of the final products of HA digested by VaHly8A (C) and VaHly8B (D) using gel filtration chromatography with a Superdex™ peptide 10/300 gel filtration column. Electrospray ionization-mass spectroscopy (ESI-MS) analysis of the final products of HA digested by VaHly8A (E) and VaHly8B (F).

To further obtain the exact molecular weight of the final products, the negative-ion ESI-MS was used (Figures 7E,F). Both main peaks in mass spectra were 378.10 m/z, corresponding to the molecular weight of unsaturated disaccharides. Therefore, VaHly8A and VaHly8B degraded HA to unsaturated disaccharides as the final products.

Hyaluronic acid-degrading bacteria are common in the marine ecosystem: a few studies previously reported hyaluronate lyase-encoding bacilli (Kurata et al., 2015) and gammaproteobacterial (Han et al., 2014; Peng et al., 2018). In this study, a hyaluronate lyase-producing marine bacterium, V. alginolyticus LWW-9, was isolated from seawater.

Based on the bioinformatic analysis, we discovered an enzymatic HA degradation system in V. alginolyticus. The organization of PULHA of V. alginolyticus closely resembles the HA PULs in Firmicutes and Fusobacteria (Oiki et al., 2017, 2019b; Kawai et al., 2018). However, compared with archetypal PULs of Bacteroides, PULHA lacks susC/susD pairs encoding a TBDT and a glycan-binding lipoprotein, respectively (Tancula et al., 1992; Reeves et al., 1997). SusC/SusD-like proteins are considered as the hallmark of PUL and have been used to identify PULs in the genomes of Bacteroides. In the genome of V. alginolyticus, no protein showing similarity with SusD was detected. Similar to other bacteria in Proteobacteria, V. alginolyticus contains TBDT proteins in the genome, which is the counterpart of SusC/SusD pairs in Proteobacteria (Blanvillain et al., 2007; Neumann et al., 2015). Blastp searches revealed that none of TBDTs identified in V. alginolyticus genome displayed high similarity with SusC. These results strongly support Blanvillain’s opinion that TBDTs related to glycan uptake evolved independently in Proteobacteria and Bacteroidetes (Blanvillain et al., 2007).

The combination of genomic studies and biochemical characterizations of individual CAZymes can enhance our knowledge of the functions of PULs in microbial communities. Here, two hyaluronate lyases in the PULHA, VaHly8A, and VaHly8B, were heterologously expressed, purified, and characterized. VaHly8A has a type I signal peptide, whereas VaHly8B has a type II signal peptide, suggesting their different subcellular localization in the bacterial cells. Hence, VaHly8A is an extracellular enzyme, whereas VaHly8B is an outer membrane enzyme. Moreover, they show distinct biochemical properties. The survival and colonization of vibrios depend on their adaption to variable parameters of the aquatic habitats and respective hosts. From the perspective of evolution, the generation of these two hyaluronate lyases is the result of the strain’s adaptation to environmental changes.

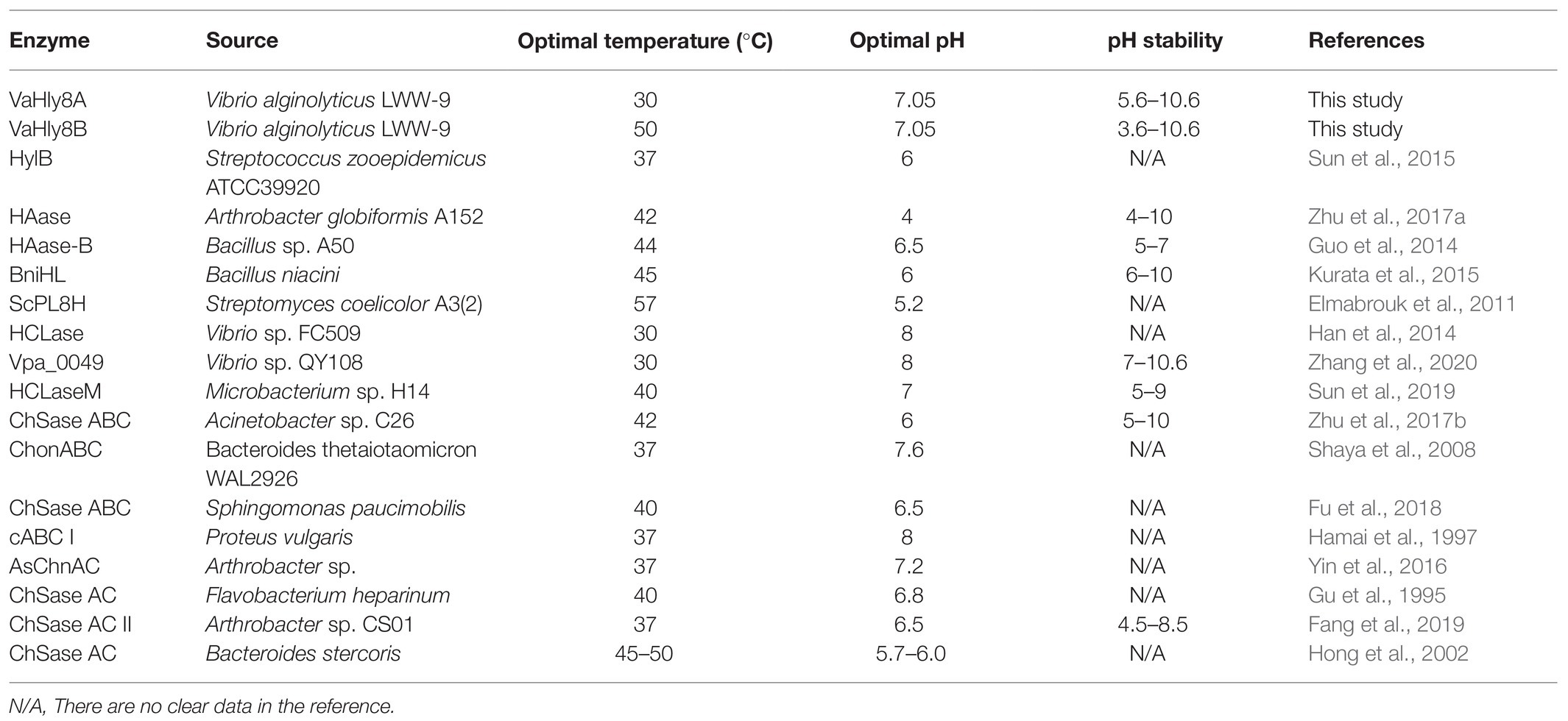

VaHly8A and VaHly8B exhibited the highest activity at 30 and 50°C, respectively. By contrast, the optimal temperatures of most identified enzymes of PL8 are 37–45°C (Table 2). VaHly8A was a cold-adapted hyaluronate lyase with lower optimal temperature and thermostability, which can conserve energy and reduce the risk of environmental contamination. Furthermore, it can be inactivated selectively by increasing the temperature slightly. Owing to these properties, the enzymatic reaction can be easily terminated and the product can be conveniently separated from the reaction mixture. Both VaHly8A and VaHly8B are most active at neutral pH, which is different from most characterized hyaluronate lyases from the PL8 family with the highest activity at acidic conditions (Table 2). VaHly8B retained about 70% activity at pH 3.6–10.6. Compared with most identified enzymes of PL8 (Table 2), VaHly8B was stable over a wider pH range. This property is advantageous for the storage of the enzyme preparation. Except SDS, most metal ions and EDTA did not obviously inhibit the activity of VaHly8B. The result revealed that VaHly8B was resistant to many metal ions. VaHly8B can degrade HA in the complex environment, which is beneficial to its industrial application. The specific activity of hyaluronate lyases is generally tens to hundreds of units per milligram by A232 enzyme activity assay, such as HCLase Er (13.8 U/mg) from Vibrio sp. FC509 (Peng et al., 2018), BniHL (136.7 U/mg) from Bacillus niacin (Kurata et al., 2015), and HAase (292.7 U/mg) from Arthrobacter globiformis A152 (Zhu et al., 2017a). In comparison, VaHly8A exhibited a higher specific activity. Our findings indicated that VaHly8A and VaHly8B are two hyaluronate lyases with novel enzymatic properties.

Table 2. Comparison of the biochemical properties of VaHly8A and VaHly8B with other PL8 family enzymes.

Hyaluronic acid exists extensively in diverse connective tissues and the nervous system of virtually all animals. Vibrio alginolyticus, a common pathogenic marine Vibrio species, is not only an emerging pathogen inducing human infection but also a common cause of economic loss in the aquaculture industry (Cao et al., 2018). Vibrio alginolyticus secrets extracellular and cell-surface hyaluronate lyases to degrade HA, leading to the breakdown of biophysical barrier of the host tissues and exposure of host cells to bacterial toxins. The degradation of HA promotes the invasion and spreading of V. alginolyticus in the host. Therefore, the PULHA of V. alginolyticus reflects the bacterial ability to utilize the given glycan as a nutrient source for survival and to produce the “spreading factors” hyaluronate lyases for colonization.

Currently, antibiotics have been mainly used to resolve V. alginolyticus-related diseases (Grimes, 2020). However, the long-term use of antibiotics may result in harmful consequences, such as antibiotic residues and drug resistance (Langdon et al., 2016). Thus, finding an effective alternative method to regulate V. alginolyticus infection is highly significant. The functional characterization of PULHA broadens our knowledge about the physiology and pathogenicity of V. alginolyticus and enables the development of novel preventive and therapeutic strategies against V. alginolyticus-associated infection.

In summary, we reported the discovery and characterization of a PUL that orchestrates the utilization of HA in a marine bacterium V. alginolyticus LWW-9. The PLs, GH, and enzymes related to monosaccharide metabolism encoded by PULHA provide an example of how V. alginolyticus completely degrade HA. The presence of two novel hyaluronate lyases with distinct biochemical properties provides critical insights into how V. alginolyticus adapts to variable parameters of the aquatic habitats and hosts for survival and colonization. Our report strengthens the previous proposition (Blanvillain et al., 2007) that TBDTs related to glycan uptake evolved independently in Proteobacteria and Bacteroidetes. Furthermore, the functional characterization of PULHA facilitates the illustration of physiology and pathogenicity of V. alginolyticus and promotes the development of alternative non-antibiotic-based means of controlling bacterial infections.

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found at: NCBI (accession: MW396717).

WY and FH: conceptualization. XW: methodology, investigation, and writing – original draft preparation. ZW and YL: investigation and data curation. HW: software and data curation. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2018YFC0311105), Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (major basic research projects; ZR2019ZD18), and the Marine S&T Fund of Shandong Province for Pilot National Laboratory for Marine Science and Technology (Qingdao; 2018SDKJ0401-2).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2021.696096/full#supplementary-material

1. ^http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi

3. ^https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/wrpsb.cgi

Austin, B. (2010). Vibrios as causal agents of zoonoses. Vet. Microbiol. 140, 310–317. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.03.015

Blanvillain, S., Meyer, D., Boulanger, A., Lautier, M., Guynet, C., Denance, N., et al. (2007). Plant carbohydrate scavenging through tonB-dependent receptors: a feature shared by phytopathogenic and aquatic bacteria. PLoS One 2:e224. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000224

Cao, J., Zhang, J., Ma, L., Li, L., Zhang, W., and Li, J. (2018). Identification of fish source Vibrio alginolyticus and evaluation of its bacterial ghosts vaccine immune effects. Microbiologyopen 7:e00576. doi: 10.1002/mbo3.576

Dechet, A. M., Yu, P. A., Koram, N., and Painter, J. (2008). Nonfoodborne Vibrio infections: an important cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States, 1997-2006. Clin. Infect. Dis. 46, 970–976. doi: 10.1086/529148

Elmabrouk, Z. H., Vincent, F., Zhang, M., Smith, N. L., Turkenburg, J. P., Charnock, S. J., et al. (2011). Crystal structures of a family 8 polysaccharide lyase reveal open and highly occluded substrate-binding cleft conformations. Proteins 79, 965–974. doi: 10.1002/prot.22938

Fang, Y., Yang, S., Fu, X., Xie, W., Li, L., Liu, Z., et al. (2019). Expression, purification and characterization of chondroitinase AC II from marine bacterium Arthrobacter sp. CS01. Mar. Drugs 17:185. doi: 10.3390/md17030185

Finn, R. D., Bateman, A., Clements, J., Coggill, P., Eberhardt, R. Y., Eddy, S. R., et al. (2014). Pfam: the protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, D222–D230. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1223

Fu, J., Jiang, Z., Chang, J., Han, B., Liu, W., and Peng, Y. (2018). Purification, characterization of Chondroitinase ABC from Sphingomonas paucimobilis and in vitro cardiocytoprotection of the enzymatically degraded CS-A. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 115, 737–745. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.04.117

Grimes, D. J. (2020). The vibrios: scavengers, symbionts, and pathogens from the sea. Microb. Ecol. 80, 501–506. doi: 10.1007/s00248-020-01524-7

Grondin, J. M., Tamura, K., Déjean, G., Abbott, D. W., and Brumer, H. (2017). Polysaccharide utilization loci: fueling microbial communities. J. Bacteriol. 199, e00860–e00816. doi: 10.1128/jb.00860-16

Gu, K., Linhardt, R. J., Laliberté, M., Gu, K., and Zimmermann, J. (1995). Purification, characterization and specificity of chondroitin lyases and glycuronidase from Flavobacterium heparinum. Biochem. J. 312, 569–577. doi: 10.1042/bj3120569

Guo, X., Shi, Y., Sheng, J., and Wang, F. (2014). A novel hyaluronidase produced by Bacillus sp. A50. PLoS One 9:e94156. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094156

Hamai, A., Hashimoto, N., Mochizuki, H., Kato, F., Makiguchi, Y., Horie, K., et al. (1997). Two distinct chondroitin sulfate ABC lyases. An endoeliminase yielding tetrasaccharides and an exoeliminase preferentially acting on oligosaccharides. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 9123–9130. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.14.9123

Han, W., Wang, W., Zhao, M., Sugahara, K., and Li, F. (2014). A novel eliminase from a marine bacterium that degrades hyaluronan and chondroitin sulfate. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 27886–27898. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.590752

Hong, S. W., Kim, B. T., Shin, H. Y., Kim, W. S., Lee, K. S., Kim, Y. S., et al. (2002). Purification and characterization of novel chondroitin ABC and AC lyases from Bacteroides stercoris HJ-15, a human intestinal anaerobic bacterium. Eur. J. Biochem. 269, 2934–2940. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.02967.x

Ina-Salwany, M. Y., Al-Saari, N., Mohamad, A., Mursidi, F. A., Mohd-Aris, A., Amal, M. N. A., et al. (2019). Vibriosis in fish: a review on disease development and prevention. J. Aquat. Anim. Health 31, 3–22. doi: 10.1002/aah.10045

Kawai, K., Kamochi, R., Oiki, S., Murata, K., and Hashimoto, W. (2018). Probiotics in human gut microbiota can degrade host glycosaminoglycans. Sci. Rep. 8:10674. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-28886-w

Kumar, S., Stecher, G., Li, M., Knyaz, C., and Tamura, K. (2018). MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 35, 1547–1549. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msy096

Kurata, A., Matsumoto, M., Kobayashi, T., Deguchi, S., and Kishimoto, N. (2015). Hyaluronate lyase of a deep-sea Bacillus niacini. Mar. Biotechnol. 17, 277–284. doi: 10.1007/s10126-015-9618-z

Langdon, A., Crook, N., and Dantas, G. (2016). The effects of antibiotics on the microbiome throughout development and alternative approaches for therapeutic modulation. Genome Med. 8:39. doi: 10.1186/s13073-016-0294-z

Li, S., and Jedrzejas, M. J. (2001). Hyaluronan binding and degradation by Streptococcus agalactiae hyaluronate lyase. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 41407–41416. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106634200

Lin, B., Hollingshead, S. K., Coligan, J. E., Egan, M. L., Baker, J. R., and Pritchard, D. G. (1994). Cloning and expression of the gene for group B streptococcal hyaluronate lyase. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 30113–30116. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)43783-0

Lombard, V., Golaconda Ramulu, H., Drula, E., Coutinho, P. M., and Henrissat, B. (2014). The carbohydrate-active enzymes database (CAZy) in 2013. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, D490–D495. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1178

Margulies, M., Egholm, M., Altman, W. E., Attiya, S., Bader, J. S., Bemben, L. A., et al. (2005). Genome sequencing in microfabricated high-density picolitre reactors. Nature 437, 376–380. doi: 10.1038/nature03959

Martens, E. C., Koropatkin, N. M., Smith, T. J., and Gordon, J. I. (2009). Complex glycan catabolism by the human gut microbiota: the Bacteroidetes sus-like paradigm. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 24673–24677. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R109.022848

Maruyama, Y., Oiki, S., Takase, R., Mikami, B., Murata, K., and Hashimoto, W. (2015). Metabolic fate of unsaturated glucuronic/iduronic acids from glycosaminoglycans: molecular identification and structure determination of streptococcal isomerase and dehydrogenase. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 6281–6292. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.604546

Neumann, A. M., Balmonte, J. P., Berger, M., Giebel, H. A., Arnosti, C., Voget, S., et al. (2015). Different utilization of alginate and other algal polysaccharides by marine Alteromonas macleodii ecotypes. Environ. Microbiol. 17, 3857–3868. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12862

Oiki, S., Mikami, B., Maruyama, Y., Murata, K., and Hashimoto, W. (2017). A bacterial ABC transporter enables import of mammalian host glycosaminoglycans. Sci. Rep. 7:1069. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-00917-y

Oiki, S., Nakamichi, Y., Maruyama, Y., Mikami, B., Murata, K., and Hashimoto, W. (2019a). Streptococcal phosphotransferase system imports unsaturated hyaluronan disaccharide derived from host extracellular matrices. PLoS One 14:e0224753. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0224753

Oiki, S., Sato, M., Mikami, B., Murata, K., and Hashimoto, W. (2019b). Substrate recognition by bacterial solute-binding protein is responsible for import of extracellular hyaluronan and chondroitin sulfate from the animal host. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 83, 1946–1954. doi: 10.1080/09168451.2019.1630250

Patil, S., and Chaudhari, B. (2017). A simple, rapid and sensitive plate assay for detection of microbial hyaluronidase activity. J. Basic Microbiol. 57, 358–361. doi: 10.1002/jobm.201600579

Peng, C., Wang, Q., Wang, S., Wang, W., Jiao, R., Han, W., et al. (2018). A chondroitin sulfate and hyaluronic acid lyase with poor activity to glucuronyl 4,6-O-disulfated N-acetylgalactosamine (E-type)-containing structures. J. Biol. Chem. 293, 4230–4243. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA117.001238

Reeves, A. R., Wang, G. R., and Salyers, A. A. (1997). Characterization of four outer membrane proteins that play a role in utilization of starch by Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron. J. Bacteriol. 179, 643–649. doi: 10.1128/JB.179.3.643-649.1997

Robert, X., and Gouet, P. (2014). Deciphering key features in protein structures with the new ENDscript server. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, W320–W324. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku316

Ruijssenaars, H. J., de Bont, J. A., and Hartmans, S. (1999). A pyruvated mannose-specific xanthan lyase involved in xanthan degradation by Paenibacillus alginolyticus XL-1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65, 2446–2452. doi: 10.1128/AEM.65.6.2446-2452.1999

Shaya, D., Hahn, B. S., Park, N. Y., Sim, J. S., Kim, Y. S., and Cygler, M. (2008). Characterization of chondroitin sulfate lyase ABC from Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron WAL2926. Biochemistry 47, 6650–6661. doi: 10.1021/bi800353g

Sudha, P. N., and Rose, M. H. (2014). Beneficial effects of hyaluronic acid. Adv. Food Nutr. Res. 72, 137–176. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-800269-8.00009-9

Sun, J., Han, X., Song, G., Gong, Q., and Yu, W. (2019). Cloning, expression, and characterization of a new glycosaminoglycan lyase from microbacterium sp. H14. Mar. Drugs 17:681. doi: 10.3390/md17120681

Sun, X., Wang, Z., Bi, Y., Wang, Y., and Liu, H. (2015). Genetic and functional characterization of the hyaluronate lyase HylB and the beta-N-acetylglucosaminidase HylZ in Streptococcus zooepidemicus. Curr. Microbiol. 70, 35–42. doi: 10.1007/s00284-014-0679-4

Tancula, E., Feldhaus, M. J., Bedzyk, L. A., and Salyers, A. A. (1992). Location and characterization of genes involved in binding of starch to the surface of Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron. J. Bacteriol. 174, 5609–5616. doi: 10.1128/JB.174.17.5609-5616.1992

Theocharis, A. D., Skandalis, S. S., Gialeli, C., and Karamanos, N. K. (2016). Extracellular matrix structure. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 97, 4–27. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2015.11.001

Volpi, N., Schiller, J., Stern, R., and Soltés, L. (2009). Role, metabolism, chemical modifications and applications of hyaluronan. Curr. Med. Chem. 16, 1718–1745. doi: 10.2174/092986709788186138

Wang, W., Wang, J., and Li, F. (2017). Hyaluronidase and chondroitinase. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 925, 75–87. doi: 10.1007/5584_2016_54

Yin, F. X., Wang, F. S., and Sheng, J. Z. (2016). Uncovering the catalytic direction of chondroitin AC exolyase: from the reducing end towards the non-reducing end. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 4399–4406. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C115.708396

Zhang, Z., Su, H., Wang, X., Tang, L., Hu, J., Yu, W., et al. (2020). Cloning and characterization of a novel chondroitinase ABC categorized into a new subfamily of polysaccharide lyase family 8. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 164, 3762–3770. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.08.210

Zhang, H., Yohe, T., Huang, L., Entwistle, S., Wu, P., Yang, Z., et al. (2018). dbCAN2: a meta server for automated carbohydrate-active enzyme annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, W95–w101. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky418

Zhu, C., Zhang, J., Li, L., Zhang, J., Jiang, Y., Shen, Z., et al. (2017a). Purification and characterization of hyaluronate lyase from Arthrobacter globiformis A152. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 182, 216–228. doi: 10.1007/s12010-016-2321-3

Keywords: hyaluronate lyase, hyaluronic acid, polysaccharide utilization loci, Vibrio, Proteobacteria

Citation: Wang X, Wei Z, Wu H, Li Y, Han F and Yu W (2021) Characterization of a Hyaluronic Acid Utilization Locus and Identification of Two Hyaluronate Lyases in a Marine Bacterium Vibrio alginolyticus LWW-9. Front. Microbiol. 12:696096. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.696096

Received: 16 April 2021; Accepted: 17 May 2021;

Published: 10 June 2021.

Edited by:

Benwei Zhu, Nanjing Tech University, ChinaCopyright © 2021 Wang, Wei, Wu, Li, Han and Yu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Feng Han, ZmhhbkBvdWMuZWR1LmNu; Wengong Yu, eXV3ZzY2QG91Yy5lZHUuY24=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.