- 1Institute of Medicinal Biotechnology, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing, China

- 2School of Pharmacy, Binzhou Medical University, Yantai, China

- 3School of Pharmacy, Yantai University, Yantai, China

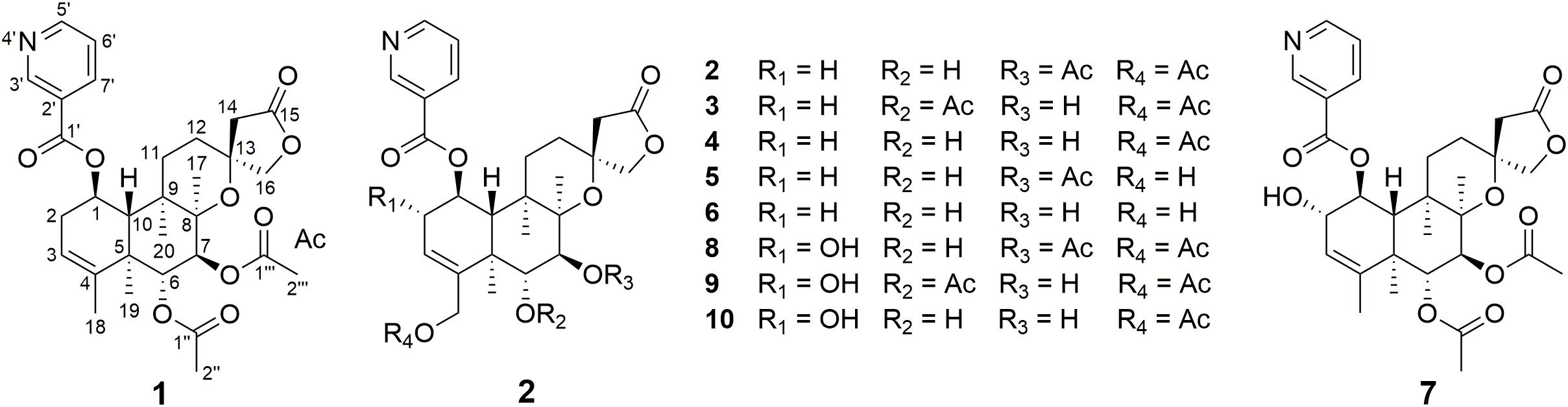

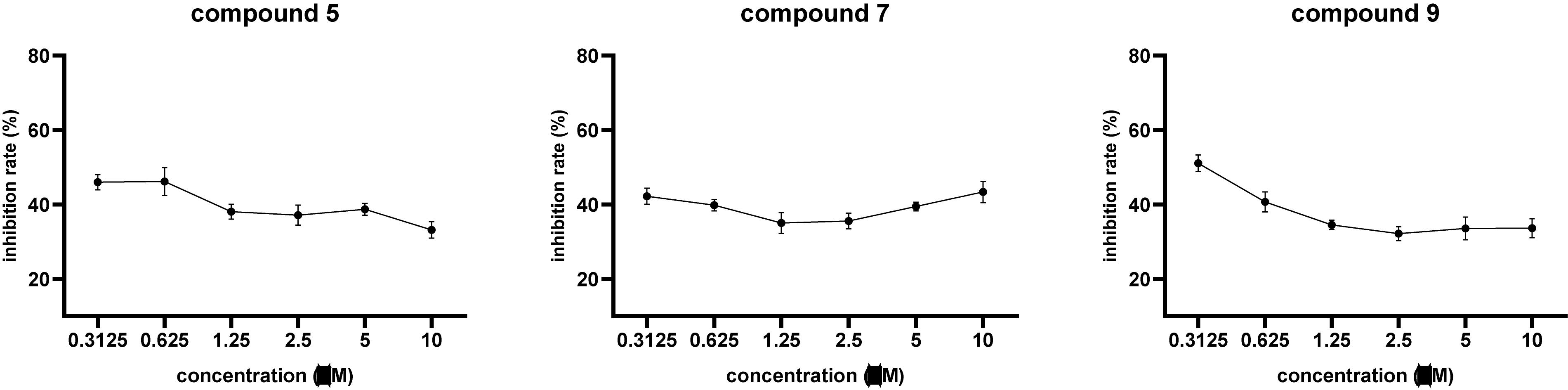

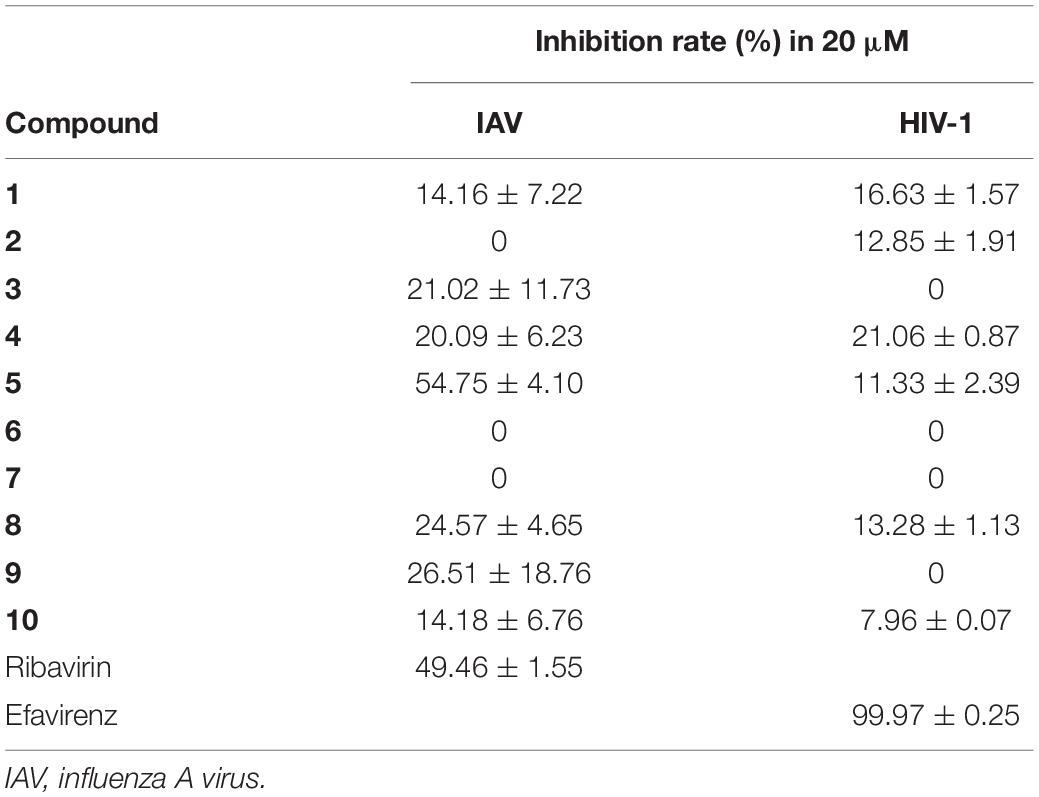

Biotransformation of the neo-clerodane diterpene, scutebarbatine F (1), by Streptomyces sp. CPCC 205437 was investigated for the first time, which led to the isolation of nine new metabolites, scutebarbatine F1–F9 (2–10). Their structures were determined by extensive high-resolution electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (HRESIMS) and NMR data analyses. The reactions that occurred included hydroxylation, acetylation, and deacetylation. Compounds 2–4 and 8–10 possess 18-OAc fragment, which were the first examples of 13-spiro neo-clerodanes with 18-OAc group. Compounds 7–10 were the first report of 13-spiro neo-clerodanes with 2-OH. Compounds 1–10 were biologically evaluated for the cytotoxic, antiviral, and antibacterial activities. Compounds 5, 7, and 9 exhibited cytotoxic activities against H460 cancer cell line with inhibitory ratios of 46.0, 42.2, and 51.1%, respectively, at 0.3 μM. Compound 5 displayed a significant anti-influenza A virus activity with inhibitory ratio of 54.8% at 20 μM, close to the positive control, ribavirin.

Introduction

Biotransformation of natural products has been proved to be an efficient and environmentally friendly approach to the preparation of new compounds, and biotransformation is a powerful tool for the regioselective and stereoselective introduction under mild conditions (Bianchini et al., 2015; Cao et al., 2015; Hegazy et al., 2015; Zafar et al., 2016; Khojasteh et al., 2019). Microbial biotransformation can be an attractive alternative to introduce hydroxyl and acetyl groups at specific positions, which were difficult to achieve by conventional synthesis methods. So biotransformation method has been widely used for structural modification of terpenoids (Silva et al., 2013; Bhatti and Khera, 2014; Rico-Martínez et al., 2014; de Sousa et al., 2018; Luchnikova et al., 2020).

Clerodane diterpenoids are a widespread class of natural products and widely distributed in medicinal herbs from various families, such as Lamiaceae, Euphorbiaceae, Compositae, and Salicaceae (Li et al., 2016). So far, over 1,300 clerodane diterpene derivatives have been reported, and they displayed a broad range of promising biological properties, such as cytotoxic, insect antifeedant, anti-inflammatory, antiprotozoal, and antibacterial activities (Li et al., 2016; Luan et al., 2019; Shen et al., 2021). Structurally, all of the natural clerodane diterpenes were classified as seven different types on the basis of the decalin ring and C-11–C-16 moiety (Supplementary Figure 1; Li et al., 2016). Although more than 1,300 clerodane diterpenoids have been reported, there are a few reports on biotransformation of neo-clerodane diterpenes (Hoffmann and Fraga, 1993; Choudhary et al., 2013; Mafezoli et al., 2014; Kumar et al., 2016; Vasconcelos et al., 2017). To the best of our knowledge, there is no report about biotransformation of 13-spiro neo-clerodane diterpenes till now. Scutebarbatine F (1) with 13-spiro neo-clerodane skeleton was firstly isolated from Scutellaria barbata in 2006 by Dai group and showed significant cytotoxic activities against HONE-1 nasopharyngeal, KB oral epidermoid carcinoma, and HT29 colorectal carcinoma cell lines (Dai et al., 2006). Subsequently, the chemical structure of scutebarbatine F was revised by Wang et al. (2010). Furthermore, the compound with the same chemical structure was also reported to be names as barbatine C and scutebata F (Nguyen et al., 2009; Zhu et al., 2010). In an attempt to obtain new biologically active neo-clerodane diterpenoids. We performed the biotransformation of scutebarbatine F using the Streptomyces sp. CPCC 205437, which resulted in the formation of nine previously undescribed metabolites (2–10) (Figure 1). Biotransformation of 1 introduces hydroxyl groups at C-2 and C-18, followed by introducing acetyl moiety in 18-OH. Herein, we describe the isolation, structure elucidation, and biological activities of nine biotransformation products (2–10).

Materials and Methods

General Experimental Procedures

Optical rotations were measured on an Autopol IV automatic polarimeter. UV spectra were recorded on a Persee TU-1901 UV-vis spectrometer. IR spectra were acquired on a PerkinElmer FT-IR/NIR spectrometer. The CD spectra were obtained on a JASCO J-815 spectropolarimeter. 1D and 2D NMR spectra were measured on Bruker ARX-600 spectrometer. Chemical shifts (δ) are given in ppm, and coupling constants (J) are given in hertz (Hz). Electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESIMS) data were taken on a Thermo LTQ mass spectrometer. High-resolution ESIMS (HRESIMS) was carried out using a Thermo LTQ Orbitrap XL mass spectrometer. Semi-preparative high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was performed using NP7000 module (Hanbon Co. Ltd., China) equipped with a Shodex RI102 detector, and YMC ODS-A C18 column (250 mm × 10 mm, i.d., 5 μm) or SunFire C18 column (250 × 10 mm, i.d., 5 μm). Column chromatography (CC) was performed with silica gel (200–300 mesh, Qingdao Marine Chemical Inc., Qingdao, PR China) and Sephadex LH-20 (GE Healthcare). Analytical thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was carried out using pre-coated silica gel GF254 plates (Yan Tai Zi Fu Chemical Group Co., Yantai, China).

Substrate

Scutebarbatine F was isolated and purified from Scutellaria barbata by the Dai group. Its structure was elucidated by HRESIMS and 1D and 2D NMR analyses as previously reported (Dai et al., 2006), and the purity was > 95% by HPLC analysis. The substrate was dissolved in dimethylformamide (DMF) before being used for biotransformation.

Microorganism and Culture Medium

The strain was originally purchased from the BeNa Culture Collection (BNCC) and identified on the basis of 16s rRNA gene sequence analysis by China Pharmaceutical Culture Collection. The 16S rRNA sequence was strongly homologous to Streptomyces kronopolitis NEAU-ML8(T) (99.3%) and has been deposited in GenBank with accession number MW699542. The strain was deposited at the China Pharmaceutical Culture Collection (No. CPCC 205437). It was grown on potato dextrose agar (PDA) slant at 28°C and stored at 4°C. The medium of Streptomyces sp. was prepared on modified potato dextrose broth (PDB) medium (potato 200 g, glucose 20 g, KH2PO4 3 g, MgSO4 0.73 g, vitamin B1 10 mg, distilled water 1 L).

Fermentation and Biotransformation

The medium was distributed in 24 Erlenmeyer flasks of 1,000 ml containing 200 ml of modified PDB liquid medium and autoclaved at 121°C. The mycelial agar plugs were transferred into the flasks and incubated at 28°C for 3 days. Compound 1 (240 mg) was dissolved in DMF, added to each, flask and incubated at 28°C for an additional 6 days.

Extraction and Isolation

After 6 days of incubation, the cultures were filtered under reduced pressure to obtain the filtrate and mycelia. The mycelia were extracted with methanol three times, and organic solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure to yield a crude extract. The CH3OH extract was suspended in water and further extracted with EtOAc to obtain EtOAc residue. The filtrate was extracted with EtOAc to afford EtOAc residue. The above two parts of EtOAc residues (2.4 g) were combined and firstly subjected to Sephadex LH-20 CC with CHCl3–CH3OH (1:1) to give five fractions (Fr.1–Fr.5). Fraction Fr.3 (1.0 g) was separated by silica gel CC using CHCl3-acetone gradient (100:0–0:100) to provide 14 fractions (Fr.3.1–Fr.3.14) on the basis of TLC analysis. Fraction Fr.3.7 (105 mg) was separated by reversed-phase semi-preparative HPLC eluting with CH3CN–H2O (45:55) at 5 ml/min to yield 2 (40 mg, 16.7%). Fraction Fr.3.8 (60 mg) was isolated by reversed-phase semi-preparative HPLC eluting with CH3CN–H2O (45:55) at 5 ml/min to give 3 (16 mg, 6.7%). Fraction Fr.3.9 (187 mg) was purified via reversed-phase semi-preparative HPLC eluting with CH3CN–H2O (45:55) at 5 ml/min to obtain 4 (26 mg, 10.8%). Fraction Fr.3.10 (40.5 mg) was applied to reversed-phase semi-preparative HPLC eluting with CH3CN–H2O (45:55) at 5 ml/min to afford four fractions (Fr.3.10.1-Fr.3.10.4); fraction Fr.3.10.2 (22 mg) was further purified by reversed-phase semi-preparative HPLC eluting with CH3CN–H2O (40:60) at 5 ml/min to yield 8 (1.8 mg, 0.8%), 9 (2.1 mg, 0.9%), and 10 (4.3 mg, 1.8%); fraction Fr.3.10.3 (15 mg) was further isolated via reversed-phase semi-preparative HPLC eluting with CH3CN–H2O (35:65) at 5 ml/min to give 5 (9.2 mg, 3.8%) and 7 (6.5 mg, 2.7%). Fraction Fr.3.11 (43 mg) was separated by reversed-phase semi-preparative HPLC eluting with CH3CN–H2O (30:70) at 5 ml/min to yield 6 (8.2 mg, 3.4%).

Scutebarbatine F1 (2): white amorphous powder; [α]25D -37.7° (c 0.05, MeOH); IR (νmax): 3,475, 2,983, 1,782, 1,717, 1,374, 1,241, 1,110, 1,023, and 743 cm–1; CD (MeOH) Δε (nm): -2.34 (237.5); ESIMS m/z 572.3 [M + H]+; HRESIMS m/z 572.2498 [M + H]+ (calcd for C30H38NO10, 572.2496); 1H and 13C NMR data (see Tables 1, 2).

Scutebarbatine F2 (3): white amorphous powder; [α]25D -23.2° (c 0.04, MeOH); IR (νmax): 3,527, 2,990, 1,783, 1,717, 1,374, 1,241, 1,109, 1,023, and 743 cm–1; CD (MeOH) Δε (nm): -1.88 (237.5); ESIMS m/z 572.3 [M + H]+; HRESIMS m/z 572.2499 [M + H]+ (calcd for C30H38NO10, 572.2496); 1H and 13C NMR data (see Tables 1, 2).

Scutebarbatine F3 (4): white amorphous powder; [α]25D -23.3° (c 0.06, MeOH); IR (νmax): 3,436, 2,983, 1,779, 1,716, 1,284, 1,241, 1,109, 1,022, and 743 cm–1; CD (MeOH) Δε (nm): -3.29 (239.5); ESIMS m/z 530.2 [M + H]+; HRESIMS m/z 530.2386 [M + H]+ (calcd for C28H36NO9, 530.2390); 1H and 13C NMR data (see Tables 1, 2).

Scutebarbatine F4 (5): white amorphous powder; [α]25D -52.2° (c 0.05, MeOH); IR (νmax): 3,406, 1,780, 1,718, 1,286, 1,245, 1,112, 1,024, and 742 cm–1; CD (MeOH) Δε (nm): -2.91 (239); ESIMS m/z 530.3 [M + H]+; HRESIMS m/z 530.2382 [M + H]+ (calcd for C28H36NO9, 530.2390); 1H and 13C NMR data (see Tables 1, 2).

Scutebarbatine F5 (6): white amorphous powder; [α]25D -20.8° (c 0.05, MeOH); IR (νmax): 3,387, 2,988, 1,780, 1,717, 1,286, 1,246, 1,112, 1,024, and 742 cm–1; CD (MeOH) Δε (nm): + 0.52 (218.5), -2.97 (240); ESIMS m/z 488.3 [M + H]+; HRESIMS m/z 488.2281 [M + H]+ (calcd for C26H34NO8, 488.2284); 1H and 13C NMR data (see Tables 1, 2).

Scutebarbatine F6 (7): white amorphous powder; [α]25D + 33.3° (c 0.03, MeOH); IR (νmax): 3,406, 2,981, 1,780, 1,723, 1,287, 1,247, 1,203, 1,113, 1,024, and 741 cm–1; CD (MeOH) Δε (nm): -0.44 (264.5); ESIMS m/z 572.2 [M + H]+; HRESIMS m/z 572.2498 [M + H]+ (calcd for C30H38NO10, 572.2496); 1H and 13C NMR data (see Tables 2, 3).

Scutebarbatine F7 (8): white amorphous powder; [α]25D + 66.0° (c 0.05, MeOH); IR (νmax): 3,355, 1,780, 1,726, 1,682, 1,240, 1,202, 1,111, 1,023, and 720 cm–1; CD (MeOH) Δε (nm): -0.39 (251.5); ESIMS m/z 588.2 [M + H]+; HRESIMS m/z 588.2441 [M + H]+ (calcd for C30H38NO11, 588.2445); 1H and 13C NMR data (see Tables 2, 3).

Scutebarbatine F8 (9): white amorphous powder; [α]25D + 125.0° (c 0.06, MeOH); IR (νmax): 3,386, 1,781, 1,723, 1,682, 1,243, 1,203, 1,132, 1,025, and 721 cm–1; CD (MeOH) Δε (nm): -0.39 (248.5); ESIMS m/z 588.3 [M + H]+; HRESIMS m/z 588.2440 [M + H]+ (calcd for C30H38NO11, 588.2445); 1H and 13C NMR data (see Tables 2, 3).

Scutebarbatine F9 (10): white amorphous powder; [α]25D + 32.6° (c 0.05, MeOH); IR (νmax): 3,364, 1,718, 1,684, 1,285, 1,203, 1,132, 1,024, 1,007, and 720 cm–1; ESIMS m/z 546.3 [M + H]+; HRESIMS m/z 546.2342 [M + H]+ (calcd for C28H36NO10, 546.2339); 1H and 13C NMR data (see Tables 2, 3).

Cytotoxic Activity Assays

MTT assay was used to measure the cytotoxicity of compounds. Five human cancer cell lines (H460, HCT8, HT15, H1975, and MIA-PaCa-2) were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). Cells (5 × 103 cells/well) were added to 96-well culture dishes and grown for 24 h followed by the addition of fresh medium (100 ml) and the test compound. After an additional 48 h, the medium was removed, and fresh medium with MTT solution was added. The cells were incubated for 1 h, and then the optical density at 450 nm was determined. Compounds 1–10 were tested for H460 and HT15 cancer cell lines at six concentrations (10, 5, 2.5, 1.25, 0.625, and 0.3125 μM), and compounds 1–10 were tested for HCT8, H1975, and MIA-PaCa-2 cancer cell lines at three concentrations (100, 10, and 1 μM). Each concentration of the compounds was tested in three parallels. IC50 values for each cell line were determined with SigmaPlot software (Chen et al., 2019).

Anti-influenza A Virus Activity Assays

All the metabolites were evaluated for their anti-influenza A virus (anti-IAV) (H1N1) activities as in previously described methods (Gao et al., 2014).

Anti-HIV Activity Assays

All the metabolites were tested for their anti-HIV activities as in previously reported methods (Zhang et al., 2017).

Antibacterial Activity Assays

All the metabolites were tested for their antibacterial activities as in previously described methods (Zhang et al., 2017).

Results and Discussion

Structure Elucidation

In this study, the incubation of scutebarbatine F (1, 240 mg) with Streptomyces sp. CPCC 205437 for 6 days led to the isolation of nine new metabolites (2–10). Their structures were elucidated by the HRESIMS and 1D and 2D NMR data.

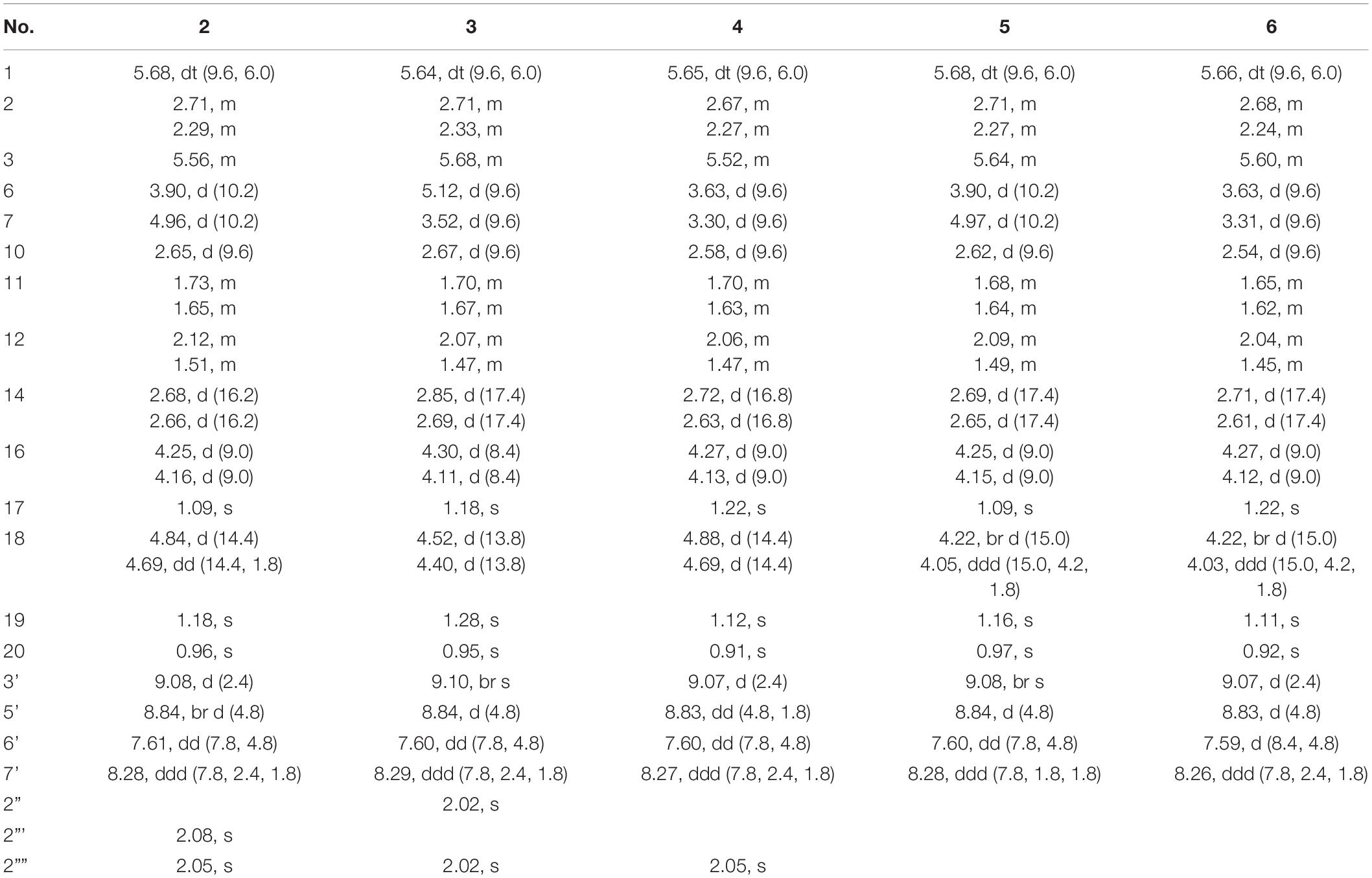

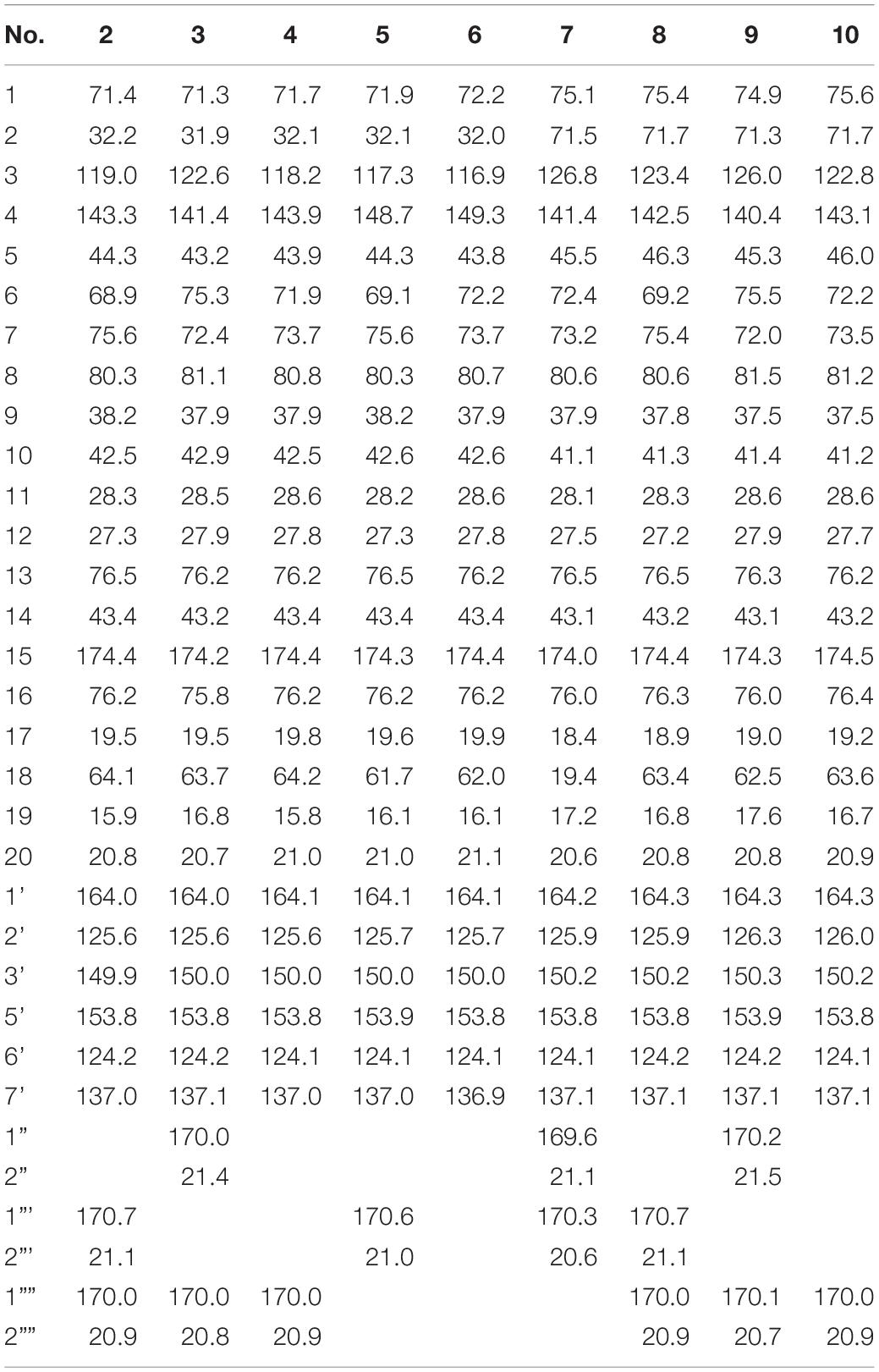

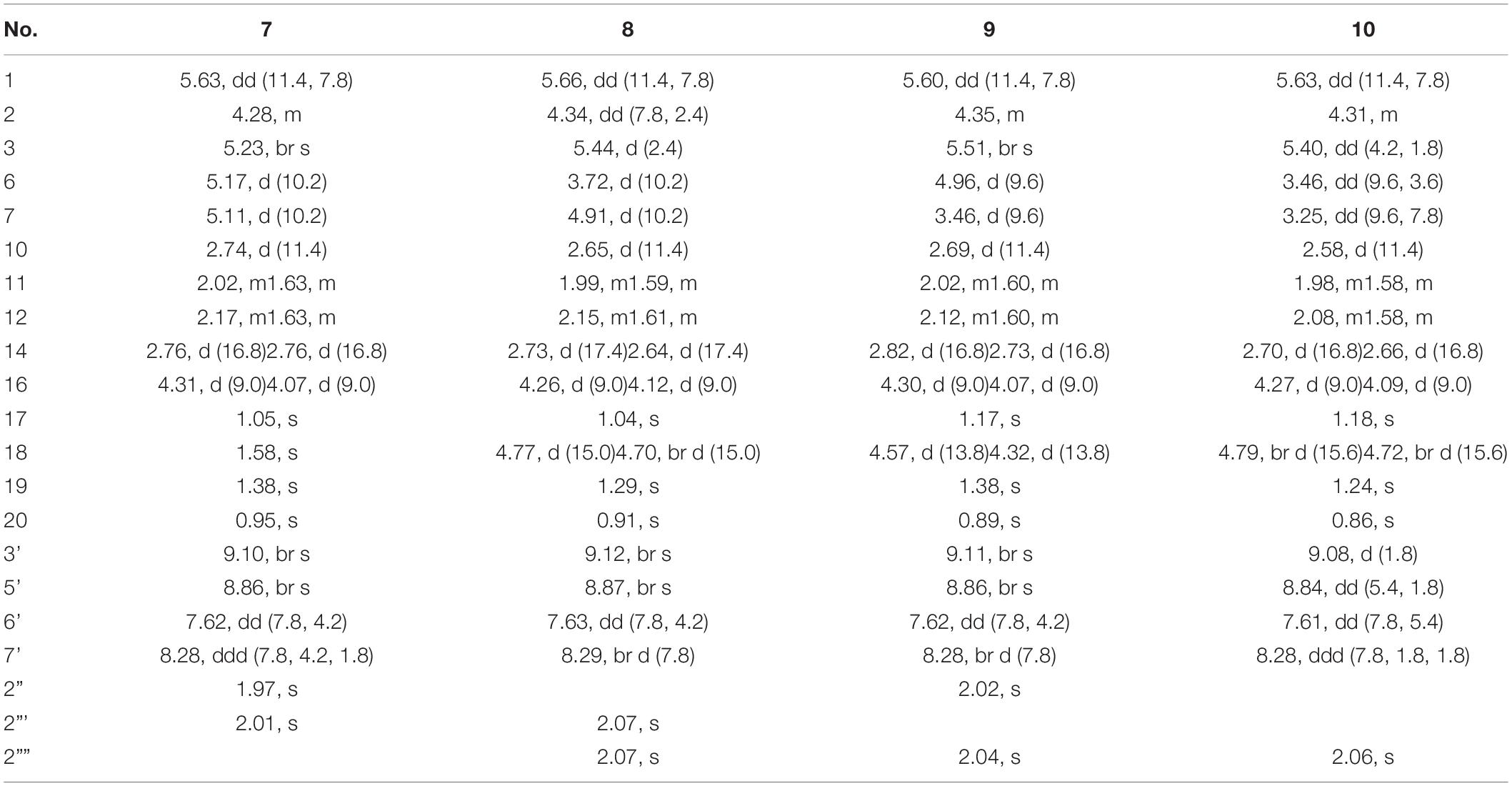

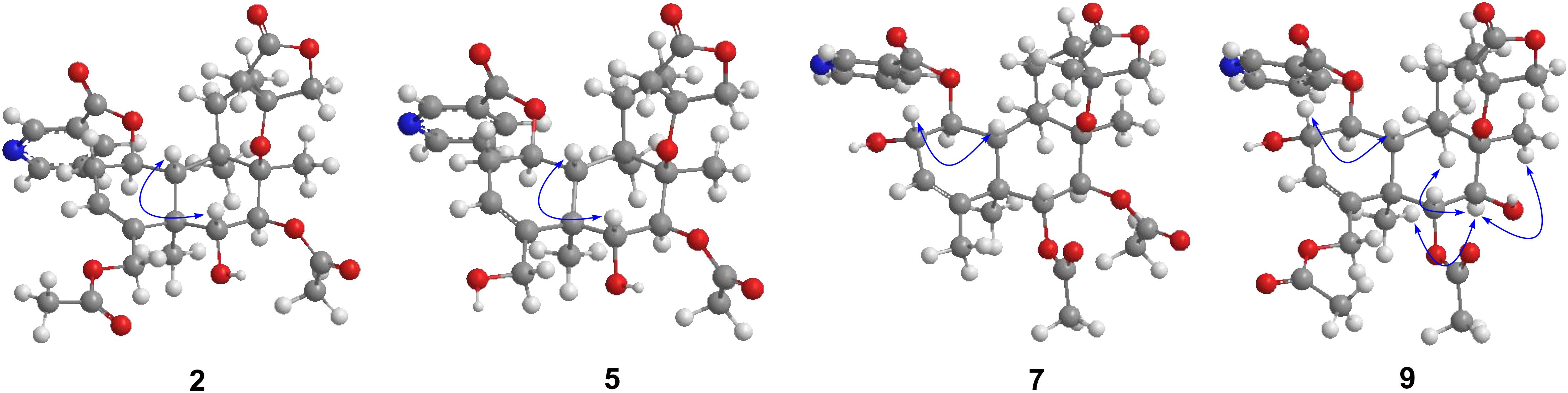

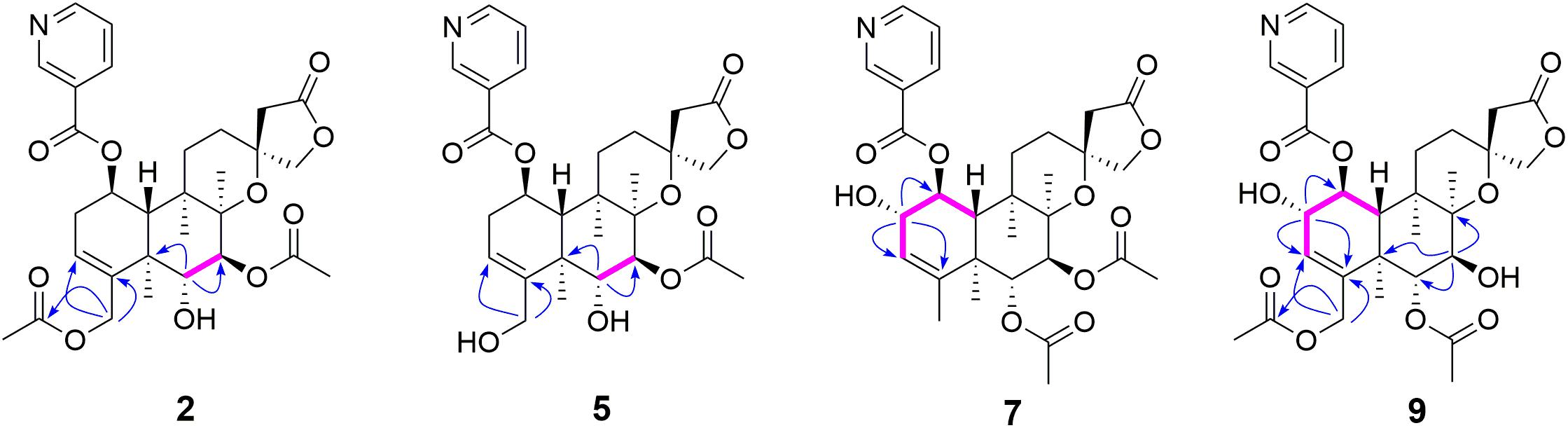

Metabolite 2 was isolated as a white amorphous powder. The HRESIMS spectrum of 2 showed an ion peak at m/z 572.2498 [M + H]+ (calcd for C30H38NO10, 572.2496), 16 amu more massive than that of 1. The 1H NMR spectrum of 2 displayed characteristic proton resonances of neo-clerodane diterpene skeleton including three tertiary methyls at δH 0.96 (3H, s, H-20), 1.09 (3H, s, H-17), and 1.18 (3H, s, H-19); two oxygenated methylenes at δH 4.16 (1H, d, J = 9.0 Hz, Ha-16), 4.25 (1H, d, J = 9.0 Hz, Hb-16), 4.69 (1H, dd, J = 14.4, 1.8 Hz, Ha-18), and 4.84 (1H, d, J = 14.4 Hz, Hb-18); three oxygenated methines at δH 3.90 (1H, d, J = 10.2 Hz, H-6), 4.96 (1H, d, J = 10.2 Hz, H-7), and 5.68 (1H, dt, J = 9.6, 6.0 Hz, H-1); and one olefinic proton at 5.56 (1H, m, H-3). The 13C NMR and distortionless enhancement by polarization transfer (DEPT) spectra of 2 showed 20 typical carbon signals for neo-clerodane diterpene skeleton, which consisted of three methyl carbons (δC 20.8, 19.5, and 15.9), six methylene carbons (δC 76.2, 64.1, 43.4, 32.2, 28.3, and 27.3, including two oxygenated), five methine carbons (δC 119.0, 75.6, 71.4, 68.9, and 42.5, including one olefinic and three oxygenated), and six quaternary carbons (δC 174.4, 143.3, 80.3, 76.5, 44.3, and 38.2, including one carbonyl, one olefinic, and two oxygenated). In addition, the 1H and 13C NMR spectra of 2 revealed the presence of two acetoxy groups [δH 2.08 (3H, s, H-2”’), δC 170.7 (C-1”’) and 21.1 (C-2”’); δH 2.05 (3H, s, H-2””), δC 170.0 (C-1””) and 20.9 (C-2””)] and a nicotinic acid ester unit [δH 9.08 (1H, d, J = 2.4 Hz, H-3’), 8.84 (1H, br d, J = 4.8 Hz, H-5’), 7.61 (1H, d, J = 7.8, 4.8 Hz, H-6’), and 8.28 (1H, ddd, J = 7.8, 2.4, 1.8 Hz, H-7’), δC 164.0 (C-1’), 125.6 (C-2’), 149.9 (C-3’), 153.8 (C-5’), 124.2 (C-6’), and 137.0 (C-7’)]. The general features of its 1H and 13C NMR spectra closely resembled those of substrate 1, except that the methyl signal [δH 1.68 (H-18), δC 20.2 (C-18)] in 1 had disappeared, and a new oxygenated methylene signal [δH 4.84, 4.69, δC 64.1] in 2 was observed, suggesting the introduction of hydroxyl group at C-18. A detailed inspection of 1H and 13C NMR spectra of 2 showed high-field shifts for H-6 (δH 3.90) and C-6 (δC 68.9), in comparison with those of 1. In the heteronuclear multiple bond correlation (HMBC) spectrum (Figure 2), the correlations from H-6 to C-4, C-5, C-7, and C-19, and from H-18 to C-3, C-4, C-5, and C-1””, indicates that acetoxy substituent at C-6 disappeared, and an acetoxy group was attached to C-18. Furthermore, the nuclear Overhauser enhancement spectroscopy (NOESY) correlation (Figure 3) of H-6/H-10, along with the large coupling constant of 3JH–6,H–7 (10.2 Hz), established the β-configuration of H-6. Therefore, metabolite 2 was determined as scutebarbatine F1.

Figure 2. Key correlated spectroscopy (COSY) and heteronuclear multiple bond correlations (HMBCs) of 2, 5, 7, and 9.

Metabolite 3 was obtained as a white amorphous powder, and its molecular formula C30H37NO10 was established by HRESIMS at m/z 572.2499 [M + H]+, which is the same as that of 2. The 1H NMR data of 3 showed oxygenated methine signals at δH 5.12 and 3.52, instead of the resonances at δH 3.90 and 4.96 in 2. The HMBC cross-peaks from H-6 to C-4, C-5, C-7, C-19, and C-1”, and from H-7 to C-5, C-6, C-8, and C-17, assigned the acetoxy group at C-6, rather than C-7. The NOESY correlations of H-7/H-17 and H-19, together with the large coupling constant of 3JH–6,H–7 (9.6 Hz), assigned the α-configuration of H-7. Thus, metabolite 3 was elucidated as scutebarbatine F2.

Metabolite 4 was obtained as a white amorphous powder. HRESIMS gave an ion peak at m/z 530.2386 [M + H]+, which refers to the molecular formula C28H35NO9 (calcd for C28H36NO9, 530.2390), with 42 amu less than that of 3. This suggested that 4 lacked an acetoxy moiety compared with 3, which was further confirmed by the HMBCs from H-6 (δH 3.63) to C-4, C-5, C-7, and C-19. The NOESY correlations of H-6/H-10; H-7/H-17, H-19, and H-20, along with the large coupling constant of 3JH–6,H–7 (9.6 Hz), established the stereochemistry of 4 as the same as substrate 1. Accordingly, metabolite 4 was determined to be scutebarbatine F3. Metabolite 6 was obtained as a white amorphous powder. HRESIMS data of 6 showed an [M + H]+ ion at m/z 488.2281, consistent with the molecular formula C26H33NO8, which is 42 amu less than that of 4, indicating the loss of an acetoxy moiety in 4. The HMBCs from H-6 to C-4, C-5, C-7, and C-19; from H-7 to C-5, C-6, C-8, and C-17; and from H-18 to C-3, C-4, and C-5 established the molecular structure of 6. The enhancement of H-10 was observed when H-6 was irradiated, and irradiation of H-7 enhanced H-17, H-19, and H-20 in the NOE experiments, indicating the relative configuration of 6. Thus, metabolite 6 was elucidated as scutebarbatine F5.

Metabolite 5 was obtained as a white amorphous powder and possessed the same molecular formula C28H35NO9 with 4 as supported by the HRESIMS ion peak at m/z 530.2382 [M + H]+ (calcd for C28H36NO9, 530.2390). The 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopic data of 5 resembled those of 2, except for the absence of an acetoxy substituent. The HMBC cross-peaks (Figure 2) from H-18 to C-3, C-4, and C-5 suggest that the C-18 acetoxy group disappeared in 5 compared with 2. In the NOE experiment, irradiation of H-6 resulted in the enhancement of H-10, together with the large coupling constant of 3JH–6,H–7 (10.2 Hz), suggesting that H-6 and H-10 were syn-oriented. Therefore, metabolite 5 was established as scutebarbatine F4.

Metabolite 7 was isolated as a white amorphous powder, and its molecular formula of C30H38NO10 was determined by the HRESIMS peak at m/z 572.2498 [M + H]+ (calcd for C30H38NO10, 572.2496), with 16 amu higher than that of 1. The 1H and 13C NMR data of 7 were similar to those of 1, except for the presence of oxygenated methine proton at δH 4.28 and oxygenated carbon at δC 71.5, suggesting that a hydroxyl group might be introduced. The location of introduced OH group was attached to C-2 by the 1H–1H correlated spectroscopy (COSY) correlations of H-1/H-2/H-3 and the HMBC cross-peaks (Figure 2) from H-2 to C-1, C-3, and C-4. The NOESY correlation (Figure 3) between H-2 and H-10, together with the large coupling constant of 3JH–1,H–2 (7.8 Hz), assigned the α-orientation of 2-OH. Therefore, metabolite 7 was determined to be scutebarbatine F6.

Metabolite 8 was obtained as a white amorphous powder. The HRESIMS spectrum displayed [M + H]+ ion peak at m/z 588.2441 (calcd for C30H38NO11, 588.2445), suggesting the substitution of one additional OH moiety compared with 2. The 1H NMR data of 8 were similar to those of 2 except that the methylene signals of H-2 at δH 2.71 and 2.29 had disappeared, and an additional oxygen-bearing methine signal at δH 4.34 was observed, indicating that the OH group may be introduced at C-2. It was further confirmed by the 1H–1H COSY correlations of H-1/H-2/H-3 and the HMBCs from H-2 to C-1, C-3, and C-4. The stereochemistry of 2-OH was determined as α-orientation on the basis of the large coupling constant of 3JH–1,H–2 (7.8 Hz) and the NOE experiment, in which the integration value of H-10 when H-2 was irradiated. The integration value of H-10 was enhanced when H-6 was irradiated, indicating the α-configuration of 6-OH. Accordingly, metabolite 8 was elucidated to be scutebarbatine F7. Metabolite 9 was isolated as a white amorphous powder. The molecular formula C30H37NO11 was deduced from the HRESIMS peak at m/z 588.2440 [M + H]+, which is the same as that of 8. Comparison of the 1H NMR data of 9 and 8 revealed an oxymethine signal at δH 3.46 in 9 in place of a signal at δH 3.72 in 8, indicating that changes happened in the C-6 and C-7 positions, and the HMBC cross-peaks from H-6 to C-4, C-5, C-7, C-19, and C-1″ determined the acetoxy group at C-6. The NOESY correlations for H-2/H-10, H-7/H-19, and H-20 assigned the α-orientation of 2-OH and H-7. Thus, metabolite 9 was determined as scutebarbatine F8.

Metabolite 10 was isolated as a white amorphous powder. HRESIMS spectrum of 10 provided a major ion peak at m/z 546.2342 [M + H]+ (calcd for C28H36NO10, 546.2339), consistent with the molecular formula of C28H35NO10, suggesting that a hydroxyl group was introduced in comparison with 4. The 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopic data of 10 were similar to those of 4. The obvious difference was the presence of oxygenated methine signal at δH 4.31 instead of methylene signals at δH 2.67 and 2.27 in 4. The OH moiety was attached to C-2 according to the 1H–1H COSY correlations of H-1/H-2/H-3 and the HMBC cross-peaks from H-2 to C-1, C-3, and C-4. The NOESY correlations of H-2/H-10, H-7/H-19, and H-20, together with the large coupling constants of 3JH–1,H–2 (7.8 Hz) and 3JH–6,H–7 (9.6 Hz), established the relative configuration of C-2, C-6, and C-7. Therefore, metabolite 10 was established as scutebarbatine F9.

Biological Activity

Compounds 1–10 were evaluated for cytotoxic activities against five human cancer cell lines including H460 (large cell lung carcinoma), HCT8 (colon carcinoma), HT15 (colon carcinoma), H1975 (non-small cell lung carcinoma), and MIA-PaCa-2 (pancreatic carcinoma). Compounds 5, 7, and 9 showed cytotoxic activities against H460 cancer cell line with inhibitory ratios of 46.0, 42.2, and 51.1%, respectively, at 0.3 μM (Figure 4 and Supplementary Table 1). Compounds 1–10 were tested for antiviral activities; compound 5 displayed a significant anti-IAV (H1N1) activity with inhibitory ratio of 54.8% at 20 μM, which is close to the positive control, ribavirin (inhibitory ratio of 49.5% at 20 μM); and none of them shows anti-HIV activities at the concentration of 20 μM (Table 4). Compounds 1–10 were also evaluated for antibacterial activities against Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29213 and Escherichia coli ATCC 25922. All compounds showed no antibacterial activities with the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) values > 32 μg/ml.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the biotransformation of 13-spiro neo-clerodane diterpene was investigated for the first time. Nine previously undescribed neo-clerodane diterpenoids 2–10 were afforded from microbial transformation of scutebarbatine F (1) by Streptomyces sp. CPCC 205437. Three types of reactions were involved in the biotransformation, including hydroxylation, acetylation, and deacetylation, in which the hydroxylation follows region- and stereo-selective routes. Hydroxylation was performed at C-2 and C-18; acetylation was further catalyzed at 18-OH; and deacetylation was carried out at C-6 and C-7. Compounds 2–4 and 8–10 were the first examples of 13-spiro neo-clerodanes with 18-OAc group. Compounds 7–10 were the first report of 13-spiro neo-clerodanes with 2-OH. Compounds 5, 7, and 9 displayed good cytotoxic activities against H460 cancer cell line at 0.3 μM. Compound 5 exhibited a significant anti-IAV activity. Our findings not only enrich the structural diversity of neo-clerodane family but also provide the guidance to biotransformation of neo-clerodane diterpenoids.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author Contributions

DZ and LY conceived and designed the experiments. DZ, XT, and GG contributed to fermentation, extraction, and isolation. DZ and SD contributed to structure elucidation and wrote the manuscript. YW, WeZ, and WuZ contributed to bioactivities tests. YR and LY were the project leaders guiding the experiments and manuscript writing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81903790), the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong (No. ZR2016HB21), the CAMS Initiative for Innovative Medicine (No. CAMS-I2M-3-014), the Non-profit Central Research Institute Fund of CAMS (Nos. 2020-PT310-003 and 2019PT350004), the National Mega-project for Innovative Drugs (2019ZX09721001-004-006), and the National Microbial Resource Center (No. NMRC-2020-3).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2021.662321/full#supplementary-material

References

Bhatti, H. N., and Khera, R. A. (2014). Biotransformations of diterpenoids and triterpenoids: a review. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 16, 70–104. doi: 10.1080/10286020.2013.846908

Bianchini, L. F., Arruda, M. F., Vieira, S. R., Campelo, P. M., Grégio, A. M., and Rosa, E. A. (2015). Microbial biotransformation to obtain new antifungals. Front. Microbiol. 6:1433. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01433

Cao, H., Chen, X., Jassbi, A. R., and Xiao, J. (2015). Microbial biotransformation of bioactive flavonoids. Biotechnol. Adv. 33, 214–223. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2014.10.012

Chen, M., Wang, R., Zhao, W., Yu, L., Zhang, C., Chang, S., et al. (2019). Isocoumarindole A, a chlorinated isocoumarin and indole alkaloid hybrid metabolite from an endolichenic fungus Aspergillus sp. Org. Lett. 21, 1530–1533. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.9b00385

Choudhary, M. I., Mohammad, M. Y., Musharraf, S. G., Onajobi, I., Mohammad, A., Anis, I., et al. (2013). Biotransformation of clerodane diterpenoids by Rhizopus stolonifer and antibacterial activity of resulting metabolites. Phytochemistry 90, 56–61. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2013.02.007

Dai, S. J., Chen, M., Liu, K., Jiang, Y. T., and Shen, L. (2006). Four new neo-clerodane diterpenoid alkaloids from Scutellaria barbata with cytotoxic activities. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 54, 869–872. doi: 10.1248/cpb.54.869

de Sousa, I. P., Sousa Teixeira, M. V., and Jacometti Cardoso, Furtado, N. A. (2018). An overview of biotransformation and toxicity of diterpenes. Molecules 23:1387. doi: 10.3390/molecules23061387

Gao, Q., Wang, Z., Liu, Z., Li, X., Zhang, Y., Zhang, Z., et al. (2014). A cell-based high-throughput approach to identify inhibitors of influenza A virus. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 4, 301–306. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2014.06.005

Hegazy, M. E., Mohamed, T. A., ElShamy, A. I., Mohamed, A. E., Mahalel, U. A., Reda, E. H., et al. (2015). Microbial biotransformation as a tool for drug development based on natural products from mevalonic acid pathway: A review. J. Adv. Res. 6, 17–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2014.11.009

Hoffmann, J. J., and Fraga, B. M. (1993). Microbial transformation of diterpenes: hydroxylation of 17-acetoxy-kolavenol acetate by Mucor plumbeus. Phytochemistry 33, 827–830. doi: 10.1016/0031-9422(93)85283-W

Khojasteh, S. C., Bumpus, N., Driscoll, J. P., Miller, G. P., Mitra, K., Rietjens, I. M. C. M., et al. (2019). Biotransformation and bioactivation reactions-2018 literature highlights. Drug Metab. Rev. 51, 121–161. doi: 10.1080/03602532.2019.1615937

Kumar, R., Saha, A., and Saha, D. (2016). Biotransformation of 16-oxacleroda-3,13(14)E-dien-15-oic acid isolated from Polyalthia longifolia by Rhizopus stolonifer increases its antifungal activity. Biocatal. Biotransfor. 34, 212–218. doi: 10.1080/10242422.2016.1247824

Li, R., Morris-Natschke, S. L., and Lee, K. H. (2016). Clerodane diterpenes: sources, structures and biological activities. Nat. Prod. Rep. 33, 1166–1226. doi: 10.1039/c5np00137d

Luan, F., Han, K., Li, M., Zhang, T., Liu, D., Yu, L., et al. (2019). Ethnomedicinal uses, phytochemistry, pharmacology, and toxicology of species from the genus Ajuga L.: a systematic review. Am. J. Chin. Med. 47, 959–1003. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X19500502

Luchnikova, N. A., Grishko, V. V., and Ivshina, I. B. (2020). Biotransformation of oleanane and ursane triterpenic acids. Molecules 25:5526. doi: 10.3390/molecules25235526

Mafezoli, J., Oliveira, M. C. F., Paiva, J. R., Sousa, A. H., Lima, M. A. S., Júnior, J. N. S., et al. (2014). Stereo and regioselective microbial reduction of the clerodane diterpene 3,12-dioxo-15,16-epoxy-4-hydroxycleroda-13(16),14-diene. Nat. Prod. Commun. 9, 759–762.

Nguyen, V. H., Pham, V. C., Nguyen, T. T. H., Tran, V. H., and Doan, T. M. H. (2009). Novel antioxidant neo-clerodane diterpenoids from Scutelaria barbata. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 33, 5810–5815. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.200900431

Rico-Martínez, M., Medina, F. G., Marrero, J. G., and Osegueda-Robles, S. (2014). Biotransformation of diterpenes. RSC Adv. 4, 10627–10647. doi: 10.1039/C3RA45146A

Shen, J., Li, P., Liu, S., Liu, Q., Li, Y., Sun, Y., et al. (2021). Traditional uses, ten-years research progress on phytochemistry and pharmacology, and clinical studies of the genus Scutellaria. J. Ethnopharmacol. 265:113189. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2020.113198

Silva, E. D. O., Jacometti Cardoso, Furtado, N. A., Aleu, J., and Collado, I. G. (2013). Terpenoid biotransformations by Mucor species. Phytochem. Rev. 12, 857–876. doi: 10.1007/s11101-013-9313-5

Vasconcelos, D. H. P., Barbosa, F. G., Oliveira, M. D. C. F. D., Lima, M. A. S., Freire, F. D. C. O., Sousa, A. H., et al. (2017). New clerodane diterpenes from fungal biotransformation of the 3,12-dioxo-15,16-epoxy-4-hydroxycleroda-13(16),14-diene. MOJ Biorg. Org. Chem. 1:00036. doi: 10.15406/mojboc.2017.01.00036

Wang, F., Ren, F. C., Li, Y. J., and Liu, J. K. (2010). Scutebarbatines W−Z, new neo-clerodane diterpenoids from Scutellaria barbata and structure revision of a series of 13-spiro neo-clerodanes. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 58, 1267–1270. doi: 10.1248/cpb.58.1267

Zafar, S., Ahmed, R., and Khan, R. (2016). Biotransformation: a green and efficient way of antioxidant synthesis. Free Radic. Res. 50, 939–948. doi: 10.1080/10715762.2016.1209745

Zhang, D., Zhao, L., Wang, L., Fang, X., Zhao, J., Wang, X., et al. (2017). Griseofulvin derivative and indole alkaloids from Penicillium griseofulvum CPCC 400528. J. Nat. Prod. 80, 371–376. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.6b00829

Keywords: neo-clerodane diterpene, scutebarbatine F, biotransformation, cytotoxicity, antiviral activity, Streptomyces

Citation: Zhang D, Tao X, Gu G, Wang Y, Zhao W, Zhao W, Ren Y, Dai S and Yu L (2021) Microbial Transformation of neo-Clerodane Diterpenoid, Scutebarbatine F, by Streptomyces sp. CPCC 205437. Front. Microbiol. 12:662321. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.662321

Received: 01 February 2021; Accepted: 12 March 2021;

Published: 14 April 2021.

Edited by:

Bingyun Li, West Virginia University, United StatesReviewed by:

Abdelsamed I. Elshamy, National Research Centre (Egypt), EgyptYongbo Xue, Sun Yat-sen University, China

Dawei Li, Dalian Medical University, China

Copyright © 2021 Zhang, Tao, Gu, Wang, Zhao, Zhao, Ren, Dai and Yu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yan Ren, cmVueWFuMTk4MjUxQDE2My5jb20=; Shengjun Dai, ZGFpc2hlbmdqdW5fOUBob3RtYWlsLmNvbQ==; Liyan Yu, eWx5QGNwY2MuYWMuY24=

Dewu Zhang

Dewu Zhang Xiaoyu Tao

Xiaoyu Tao Guowei Gu1

Guowei Gu1 Yujia Wang

Yujia Wang Yan Ren

Yan Ren Liyan Yu

Liyan Yu