- Department of Clinical Laboratory, Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Hangzhou, China

Multidrug-resistant (MDR) Klebsiella pneumoniae is a severe threat to public health worldwide. Worryingly, colistin resistance, one of the last-line antibiotics for the treatment of MDR K. pneumoniae infection, has been increasingly reported. This study aims to investigate the emergence of evolved colistin resistance in a carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae isolate during colistin treatment. In this study, a pair of sequential carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae isolates were recovered from the same patient before and after colistin treatment, named KP1-1 and KP1-2, respectively. Antibiotic susceptibility testing was performed by the microdilution broth method. Whole genome sequencing was performed, and putative gene variations were analyzed in comparison of the genome sequence of both isolates. The bacterial whole genome sequence typing and source tracking analysis were performed by BacWGSTdb 2.0 server. Validation of the role of these variations in colistin resistance was examined by complementation experiments. The association between colistin resistance and the expression level of PhoP/PhoQ signaling system and its regulated genes was evaluated by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) assay. Our study indicated that KP1-1 displayed extensively antibiotic resistant trait, but only susceptible to colistin. KP1-2 showed additional resistance to colistin. Both isolates belonged to Sequence Type 11 (ST11). The whole genome sequence analysis uncovered multiple resistance genes and virulence genes in both isolates. No plasmid-mediated mcr genes were found, but genetic variations in five chromosomal genes, especially the Gln30∗ alteration in MgrB, were detected in colistin-resistant isolate KP1-2. Moreover, only complementation with wild-type mgrB gene restored colistin susceptibility, with colistin MIC decreased from 32 to 1 mg/L. Expression assays revealed an overexpression of the phoP, phoQ, and pmrD genes in the mgrB-mutated isolate KP1-2 compared to the wild-type isolate KP1-1, confirming the MgrB alterations was responsible for increased expression levels of those genes. This study provides direct in vivo evidence that Gln30∗ alteration of MgrB is a critical region responsible for colistin resistance in K. pneumoniae clinical strains.

Introduction

Carbapenem resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae has increased worldwide, mainly due to the rapid dissemination of antimicrobial-resistant bacteria and carbapenem overconsumption, thus limiting the effectiveness of therapeutic regimens (Tzouvelekis et al., 2012; van Duin and Doi, 2017). Polymyxins (polymyxin B and colistin) are considered as the last-resort antibiotics to treat infections caused by carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae (Giamarellou, 2016; Poirel et al., 2017). Colistin initially exhibited robust antibacterial activity for carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae, however, the emergence of colistin-resistant isolates has been reported repeatedly as its use expanded (Cannatelli et al., 2013; Jayol et al., 2014; Olaitan et al., 2014a; Aires et al., 2016; Giamarellou, 2016; Haeili et al., 2017; Hamel et al., 2020).

In K. pneumoniae, resistance to polymyxins is mostly mediated by adding 4-amino-4-deoxy-L-arabinose (L-Ara4N) and/or phosphoethanolamine (PEtN) to the lipid A moiety of lipopolysaccharide (LPS), which reduces the affinity between polymyxins and LPS (Olaitan et al., 2014b; Poirel et al., 2017). This modification can be regulated by the PhoQ/PhoP and PmrAB signaling systems, which regulate the expression of pmrCAB and pmrHFIJKLM operons responsible for modification of lipid A (Jayol et al., 2014; Olaitan et al., 2014b; Poirel et al., 2017). MgrB is a small regulatory transmembrane protein and exerts negative feedback on the PhoQ/PhoP signaling system (Lippa and Goulian, 2009). Thus, genetic alterations of MgrB have been proved to be responsible for colistin resistance (Cannatelli et al., 2013, 2014; Poirel et al., 2015; Aires et al., 2016; Hamel et al., 2020). Moreover, plasmid mediated mobile colistin resistance (mcr gene) has been reported as a transmissible resistance mechanism in Enterobacteriaceae, including K. pneumoniae (Liu et al., 2016; Caniaux et al., 2017; Ga et al., 2019).

In this study, we investigated the genomic variations between a paired colistin-susceptible and -resistant K. pneumoniae isolates consecutively recovered from a single patient, and demonstrated the mechanism responsible for the emergence of high-level resistance to colistin during in vivo treatment.

Materials and Methods

The Patient and Isolates

A 66-year-old female patient was hospitalized, in a tertiary hospital in Hangzhou, Zhejiang province, China, in 2019, with symptoms of pyosepticemia, pancreatic malignancy, leukopenia, thrombocytopenic purpura, hepatic failure, and renal insufficiency. Initially, the patient received tigecycline by intravenous injection. Isolates were cultured from the inpatient during her hospitalization. The first isolate KP1-1, cultured form the blood sample of the inpatient within 24 h after admission, displayed extensively antibiotic resistance (including tigecycline) but susceptible only to colistin. The antibiotic therapeutic strategy was then adjusted to that of intravenous colistin (500,000 Unit every 8 h for the first 4 days and every 12 h for the following days). After received colistin treatment for 9 days, the second isolate KP1-2 was cultured from the stool sample with a colistin MIC of 32 mg/L. At the end of the treatment period, the inpatient expired from pyosepticemia and pancreatic malignancy. The isolates were identified by VITEK 2 (bioMérieux, Marcy-l’Étoile, France) and Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF-MS, Bruker, Billerica, MA, United States).

Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed by the microdilution broth method for the following antimicrobial agents: aztreonam, fosfomycin, ertapenem, ceftazidime, cefepime, cefoperazone-sulbactam, cefoxitin, levofloxacin, ciprofloxacin, amikacin, tetracycline, minocycline, tigecycline, colistin, cefotaxime, meropenem, imipenem, gentamicin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, piperacillin, and piperacillin-tazobactam. The results were interpreted according to Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines, except for tigecycline and colistin, which were interpreted according to the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) guidelines. Escherichia coli (ATCC 25922) were used as quality control strains for antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

Whole-Genome Sequencing

Genomic DNA was extracted using a QIAamp DNA MiniKit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, United States) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The bacterial genome was fragmented by sonication using a Covaris M220 sonicator (Covaris, Woburn, MA, United States) and the sheared DNA fragments were then used to prepare a shotgun paired-end library with an average insert size of 350 bp via a TruSeq DNA Sample Prep kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, United States). The prepared library was sequenced using the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, United States) through the 150 bp paired-end protocol. The short reads were assembled using Unicycler v0.4.8 software (Wick et al., 2017).

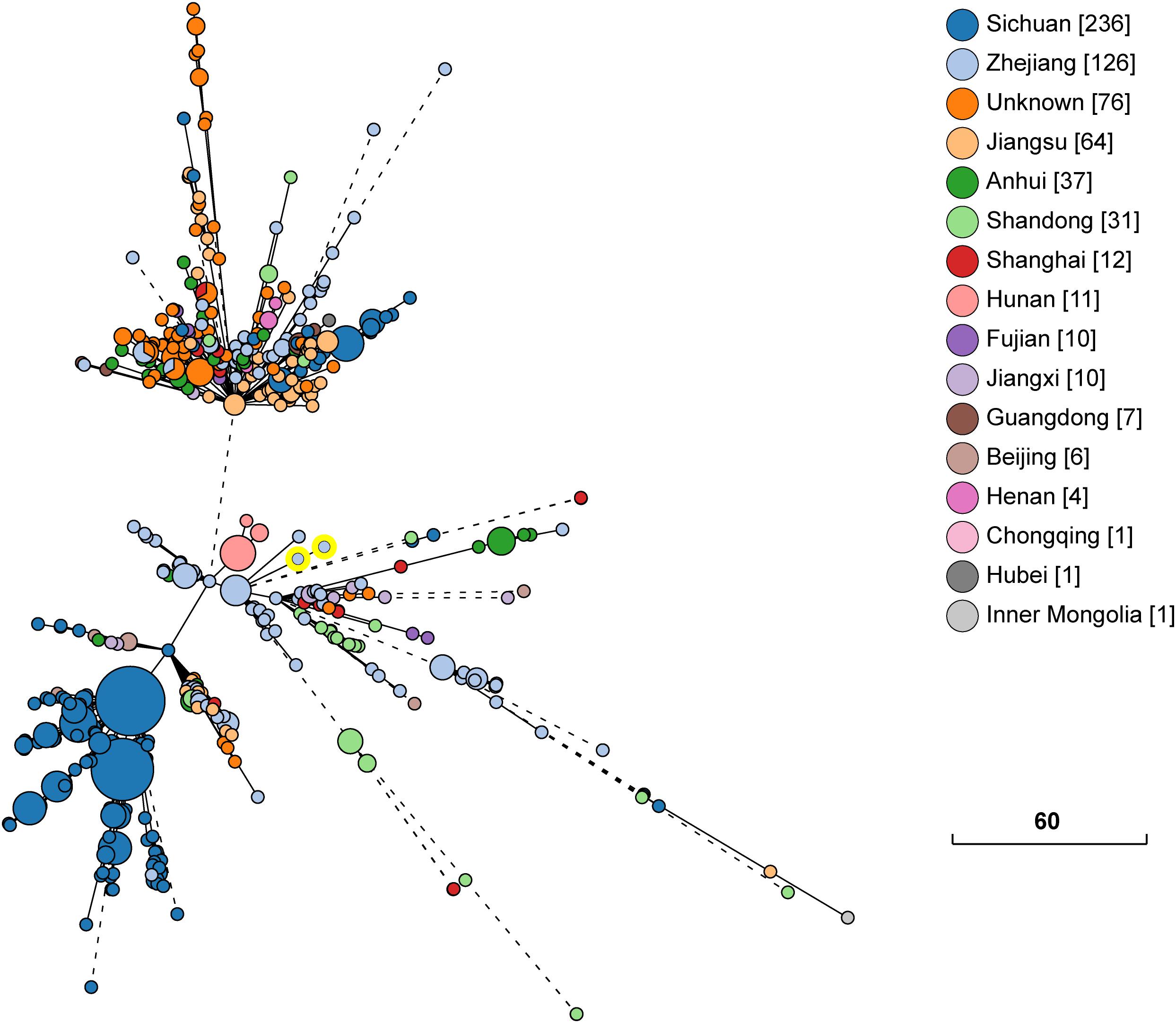

The genome annotation was conducted using the NCBI Prokaryotic Genome Annotation Pipeline (PGAP) (Tatusova et al., 2016). Antibiotic resistance genes, virulence genes, and plasmid replicons were queried using ABRicate 1.0.1 in tandem with ResFinder 4.1, CARD 2020, VFDB 2019, and PlasmidFinder 2.1 databases, with a 90% threshold for gene identification and a 60% minimum length to respective database entries. With the genomic sequence of the first isolate KP1-1 as the reference, the reads of the second isolate KP1-2 was mapped against that of KP1-1 using CLC Genomics Workbench 12. The gene variations, including single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and insertion and deletion mutations were predicted, and the variations were verified by PCR and Sanger sequencing. In silico multilocus sequence typing (MLST) analysis and bacterial source tracking using core genome MLST (cgMLST) strategy were performed using BacWGSTdb 2.0 server (Ruan and Feng, 2016; Ruan et al., 2020; Feng et al., 2021). The phylogenetic relationship between K. pneumoniae KP1-1, KP1-2 and a total of 631 publicly available ST11 K. pneumoniae isolates recovered from China were analyzed.

Complementation Assays

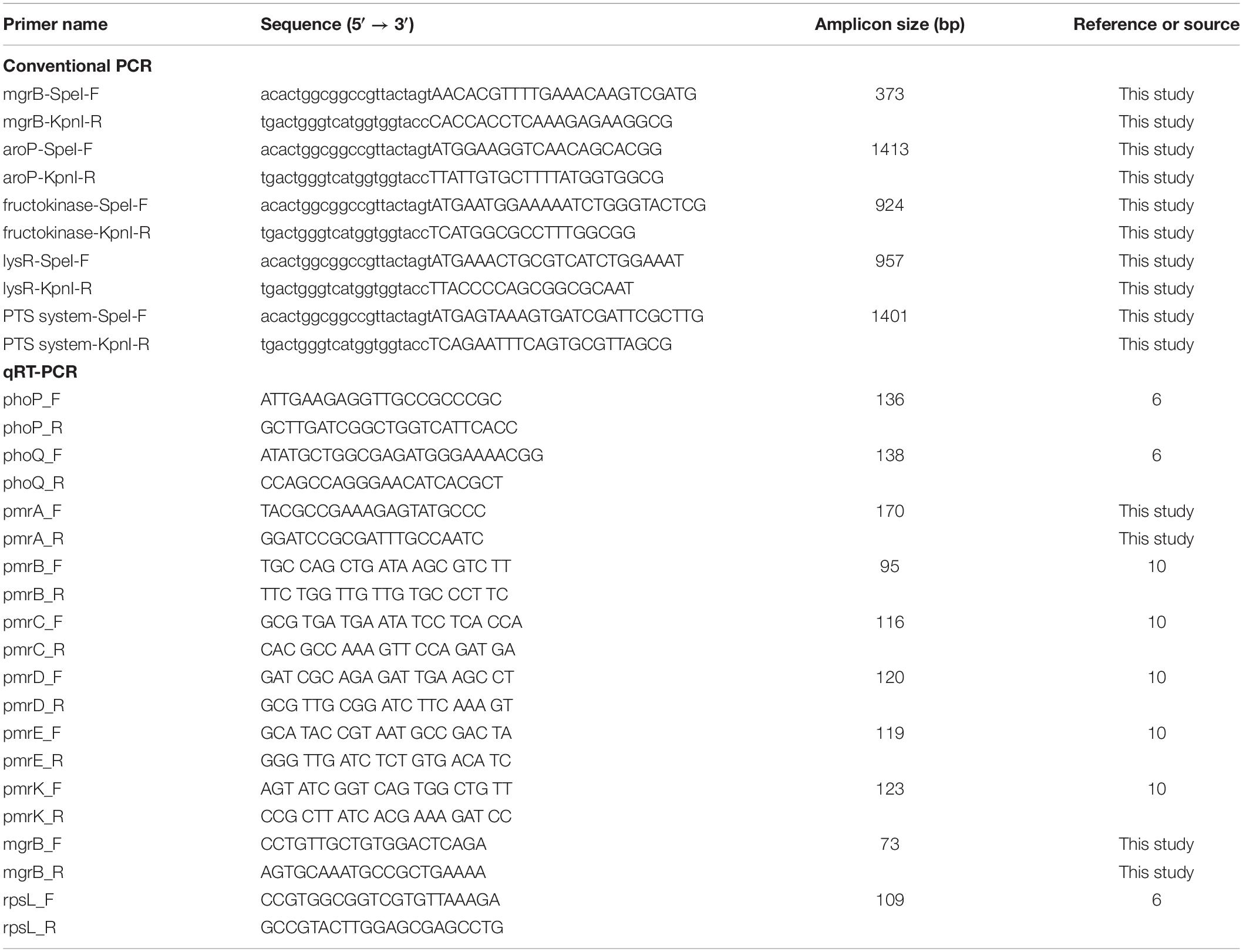

The high-copy plasmid pCR2.1-Hyg, constructed by inserting a hygromycin-resistant gene into the HindIII site of pCR2.1, was used as a genetic vector. Escherichia coli DH5α was used as the host for recombinant plasmids. The differential genes were amplified from the colistin-susceptible isolates KP1-1 using the primers shown in Table 1. The purified amplified fragments were, respectively, cloned into the plasmid pCR2.1-Hyg using the ClonExpress II One Step Cloning Kit (Vazyme, Nanjing, China). Then, the recombinant plasmids were separately transformed into the E. coli DH5α for amplification, and eventually introduced into the colistin-resistant isolates KP1-2 by electroporation. The plasmid pCR2.1-Hyg was also transformed into KP1-2 as blank control. Electro-transformants were selected on Mueller-Hinton agar supplemented with 40 g/mL of hygromycin.

Transcriptional Analysis by Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Expression levels of phoP, phoQ, pmrA, pmrB, pmrC, pmrD, pmrE, pmrK, and mgrB genes were determined by qRT-PCR with the primers listed in Table 1. Total RNA was extracted from the mid-log phase bacterial culture using the PureLinkTM RNA Mini Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States) and treated with RNase-free DNase I (Takara Biotechnology, Dalian, China) to remove genomic DNA contamination. Then, the corresponding cDNAs were generated from 500 ng of RNA using the HiFiScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (CWBio, Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. qRT-PCR was performed using MagicSYBR Mixture (CWBio, Beijing, China) on the Applied BiosystemsTM QuantStudioTM 1 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States). Thermal cycling conditions were as follows: 95°C for 30 s for enzyme activation, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 5 s and annealing at 60°C for 30 s. The relative gene expression levels were determined using the comparative threshold cycle (ΔΔCt) method with rpsL gene normalization. The experiments were performed in triplicate and repeated three times.

Accession Number

The draft genome sequence of K. pneumoniae KP1-1 and KP1-2 were deposited in the NCBI GenBank database under the accession numbers JAERIE000000000 and JAERIF000000000.

Results

Isolate Characterizations

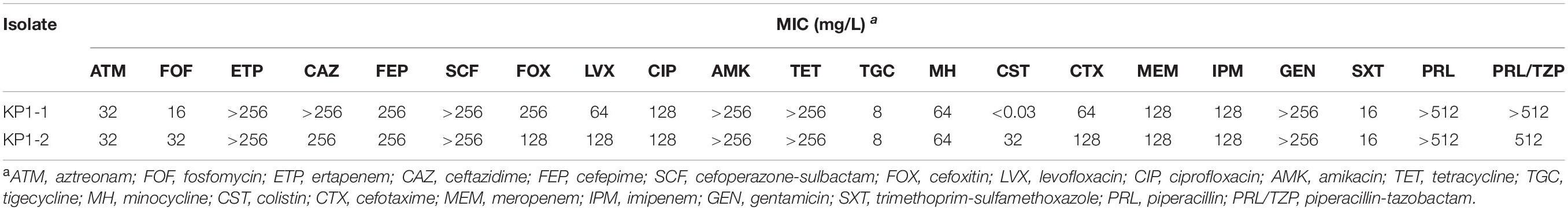

The minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of the two isolates to 21 antibiotics were shown in Table 2. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing showed that the first isolate KP1-1 was extensively drug-resistant, including aztreonam, ertapenem, ceftazidime, cefepime, cefoperazone-sulbactam, cefoxitin, levofloxacin, ciprofloxacin, amikacin, tetracycline, minocycline, tigecycline, cefotaxime, meropenem, imipenem, gentamicin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, piperacillin, and piperacillin-tazobactam. However, it remains susceptible to colistin (MIC < 0.03 mg/L). After the colistin therapy for 9 days, the second isolate KP1-2 was recovered with an increased colistin MIC of 32 mg/L.

Genomic Characteristics

The whole genome sequence data analysis classified isolates KP1-1 and KP1-2 to the same Sequence Type 11 (ST 11). Both KP1-1 and KP1-2 harbored multiple antimicrobial resistance genes, including aminoglycosides (aadA2 and rmtB), β-lactams (blaCTX–M–65, blaKPC–2 and blaTEM–1B), fluoroquinolones (qnrS1), fosfomycin (fosA), phenicols (catA2), sulfonamides (sul2), tetracyclines [tet(A)], and trimethoprim (dfrA14). Moreover, we also identified several virulence genes, including aerobactin (iutA, iucA, iucB, iucC, and iucD), hypermucoviscosity (rmpA and rmpA2), and yersiniabactin (ybtA, ybtE, ybtP, ybtQ, ybtU, ybtT, and ybtX). Phylogenetic analysis indicated that the majority of ST11 K. pneumoniae isolates in NCBI GenBank database were recovered from Sichuan and Hangzhou, and the most closely related strain to K. pneumoniae KP1-1 and KP1-2 is L20, another ST11 strain previously recovered from a human feces sample in Hangzhou in the year 2016, which differed by only 15 cgMLST loci (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Phylogenetic relationship between K. pneumoniae KP1-1, KP1-2 and a total of 631 ST11 K. pneumoniae strains retrieved from NCBI GenBank. The lines connecting the circles indicate the clonal relationship between different isolates. The scale bar represents a pairwise allelic difference of core genome multilocus sequence typing (cgMLST) loci. The number of isolates from each province is given in square brackets. The solid line indicates the pairwise allelic differences of two isolates is less than 50 alleles. Branches longer than 50 allelic differences are proportionally shortened and are represented by dashed lines. The two yellow circles indicate K. pneumoniae KP1-1, KP1-2.

Genetic Variations in Colistin-Susceptible and -Resistant Isolates

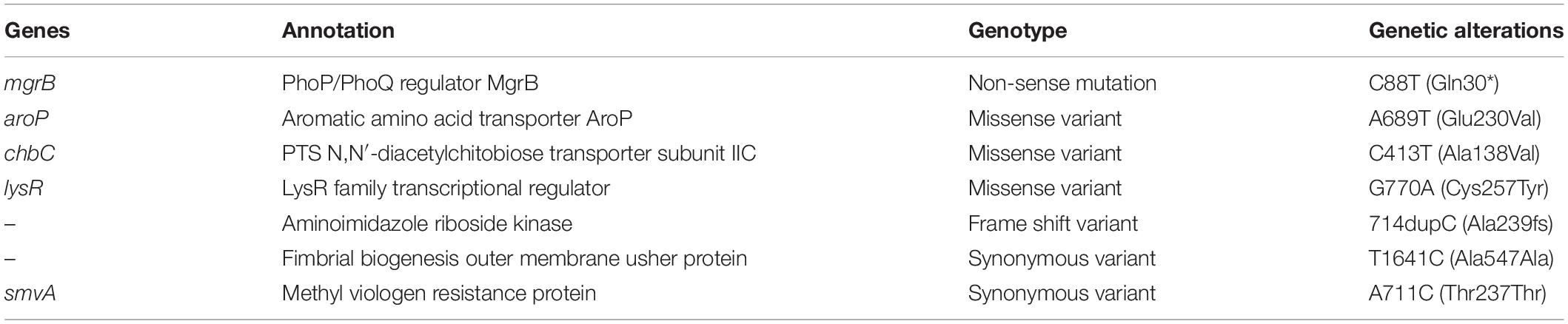

Regarding to the colistin resistance, no plasmid-mediated genes (mcr-1 to mcr-10) were found in isolate KP1-2. To explain the mechanism of colistin resistance, the raw sequence reads of KP1-1 and KP1-2 were mapped and putative variations were identified in seven genes (Table 3). Compared with the colistin-susceptible KP1-1, a premature stop codon was detected in the mgrB gene at the position 88 (C88T) in isolate KP1-2, leading to a non-sense mutation in the amino acid sequence for glutamine to stop at position 30 of the protein (Gln30∗). The full-length MgrB protein, which is 47 amino acids in wild type isolates, was therefore only 29 amino acids long in isolate KP1-2.

Moreover, Missense variants were detected in aromatic amino acid transporter AroP (A689T, Glu230Val), PTS N,N’-diacetylchitobiose transporter subunit ChbC (C413T, Ala138Val), transcriptional activator protein LysR (G770A, Cys257Tyr), and a frameshift variant was detected in aminoimidazole riboside kinase (714dupC, Ala239fs). Synonymous variants were found in fimbrial biogenesis outer membrane usher protein (T1641C) and Methyl viologen resistance protein SmvA (A711>C).

Complementation Experiments

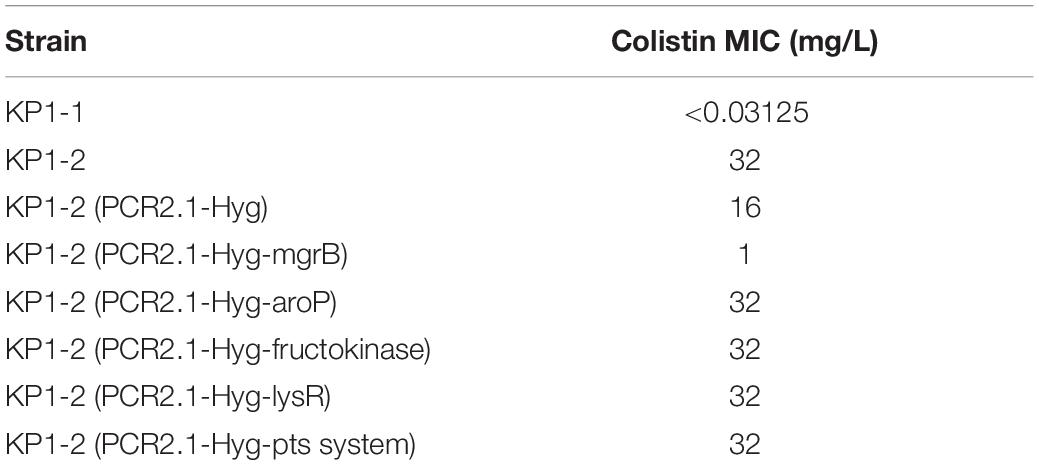

The significance of the non-silent alterations of the five genes detected in colistin-resistant KP1-2 was determined by complementation experiments. The introduction of PCR2.1-Hyg-mgrB, which carries a cloned copy of the KP1-1 mgrB gene along with part of its flanking sequence, in isolate KP1-2 was able to restore susceptibility to colistin, with MIC decreased from 32 to 1 mg/L (Table 4). However, complementation with the rest four functional genes did not alter colistin susceptibility in KP1-2 isolates. This indicates that colistin resistance is not related to these alterations in the other four genes. On the contrary, transformed with the PCR2.1-Hyg, minor change of colistin MIC was found in KP1-2 (MIC decreased to 16 mg/L).

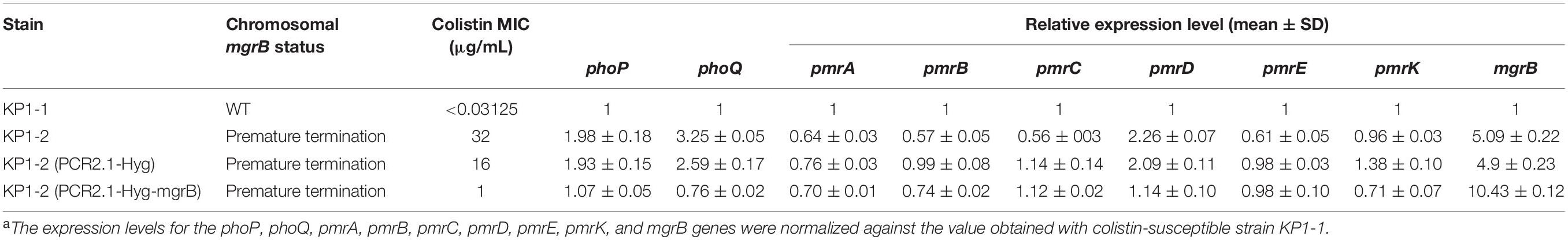

Gln30∗ Substitution in MgrB Associated With phoPQ and pmrD Overexpression

Expression levels of the phoPQ operon and pmr genes were analyzed to assess the impact of the Gln30∗ substitution in MgrB. Analysis of phoP, phoQ, and pmrD transcription by qRT-PCR revealed a two- to three- fold increase in KP1-2 carrying an inactivated mgrB allele in comparison with KP1-1 and with the mgrB mutants complemented with a cloned copy of wild-type mgrB (Table 5). However, there was no upregulation in the expression of pmrA, pmrB, pmrC, pmrE, and pmrK genes. Interestingly, significant upregulation of mgrB was observed for KP1-2 (5-fold) and KP1-2 complemented with wild-type mgrB (10-fold).

Table 5. Colistin MICs and the expression levels of phoP, phoQ, pmrA, pmrB, pmrC, pmrD, pmrE, pmrK, and mgrB genes of K. pneumoniae KP1-1, KP1-2, and of the corresponding transformants carrying either the PCR2.1-Hyg or PCR2.1-Hyg-mgrB plasmidsa.

Discussion

Over the past decade, increased rates of resistance to antibiotics in K. pneumoniae has been reported worldwide (Olaitan et al., 2014a; Giamarellou, 2016; van Duin and Doi, 2017). Colistin has regained a significant part of the therapeutic regimen for treatment of infection caused by carbapenem-resistant bacteria. However, it rapidly developed resistance due to the frequent use in clinical settings, becoming a major public health concern (Olaitan et al., 2014a; Giamarellou, 2016). In the present study, we monitored the evolved colistin resistance in a 66-year-old female inpatient infected with carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae during colistin treatment. Our data provide the direct evidence that genetic evolution in the mgrB gene can lead to a high level of colistin resistance and cause treatment failure.

Colistin resistance is mainly mediated by chromosome or horizontal gene transfer. Chromosomal mutations in two-component systems (PmrA/PmrB and PhoP/PhoQ) and genes regulating these systems can lead to colistin resistance in K. pneumoniae (Olaitan et al., 2014a,b; Poirel et al., 2017). Moreover, plasmid-mediated mcr genes, which encodes a phosphoethanolamine transfer enzyme, have been identified to confer resistance to colistin via horizontal gene transfer (Liu et al., 2016; Caniaux et al., 2017; Ga et al., 2019). None of the plasmid encoded mcr-1 to mcr-10 genes were detected in KP1-2, which demonstrating that the colistin resistance is mediated by chromosomally encoded mechanisms.

By mapping the whole genome sequences of KP1-1 and KP1-2, five genes with non-silent alterations were exhibited in colistin-resistant KP1-2, including inactivated mgrB gene mediated by premature termination. MgrB, a small transmembrane protein with 47 amino acids, mediates potent negative feedback on the PhoQ/PhoP regulatory system, which regulates genes implicated in the LPS modifications and colistin resistance (Lippa and Goulian, 2009; Olaitan et al., 2014b; Poirel et al., 2017). Until now, the insertion of IS elements (especially the IS5-like element), non-sense mutations, and missense mutations have recently been reported in colistin resistance in K. pneumoniae isolates in diverse clinical and non-clinical isolates (Cannatelli et al., 2013, 2014; Olaitan et al., 2014a; Poirel et al., 2015; Aires et al., 2016; Haeili et al., 2017; Hamel et al., 2020). Among the above genetic variations, insertional inactivation of mgrB by IS elements, especially IS5-like elements, seemingly to be the most common mechanism of mgrB variation. Regarding the missense mutations, genetic alterations in MgrB, including Q30stop and C28stop, have been identified to be responsible for colistin resistance in K. pneumoniae isolates (Olaitan et al., 2014a; Aires et al., 2016). We suppose that premature termination within mgrB, found in the present study, result in MgrB inactivation and therefore lead to PhoP/PhoQ activation which in turn activates the PmrA/PmrB response regulator.

Complementation experiments showed that only transformation of wild mgrB gene had the ability to restore colistin susceptibility in KP1-2. This result agrees with that mgrB disruptions and mutations represent a strong association with colistin resistance mechanism in K. pneumoniae (Cannatelli et al., 2013, 2014; Olaitan et al., 2014a; Poirel et al., 2015; Aires et al., 2016; Haeili et al., 2017; Hamel et al., 2020). The Gln30∗ substitution, has been reported in several studies in different countries, found in the KP1-2 reinforced the hypothesis that position C88 in the mgrB (codon 30 in protein) is a critical region, which is prone to mutate upon colistin treatment (Olaitan et al., 2014a; Poirel et al., 2015; Aires et al., 2016; Haeili et al., 2017). Compared with the colistin resistance resulting from the mcr genes and two-component systems, the inactivation of MgrB leads to a higher level of colistin resistance (Olaitan et al., 2014a; Liu et al., 2016; Ga et al., 2019). In the current study, MgrB variation conferring colistin resistance occurred in a successful pandemic clone ST11, which will likely cause global presence of pan-drug-resistant K. pneumoniae and need continuous monitor.

The disruption of mgrB results in the activation of PhoP/PhoQ signaling system, which is known to indirectly activate the PmrA/PmrB via PmrD (Lippa and Goulian, 2009; Olaitan et al., 2014b). The activation of the PmrA/PmrB leads to the upregulation of pmrCAB and pmrHFIJKLM-pmrE operons that transfer of PEtN and L-Ara4N cationic groups to the LPS, which is responsible for the acquisition of colistin resistance in K. pneumoniae (Olaitan et al., 2014b; Poirel et al., 2017). Thus, it is generally accepted that loss of MgrB activates the cross-regulation of PhoPQ-PmrD-PmrAB signal transduction pathway in K. pneumoniae. However, activation of PhoP/PhoQ through mgrB mutation dose not significantly activate the production of PmrA/PmrB and confers colistin resistance. Therefore, PhoP/PhoQ activation alone is able to confer colistin resistance even without any additional effects caused by PmrA/PmrB activation (Cheung et al., 2020). In our study, we observed a signification association between colistin resistance, attributed to Gln30∗ substitution in MgrB, and upregulation of phoPQ operon and pmrD gene despite there being no upregulation of pmrHFIJKLM and pmrCAB operons. This can be explained by the fact that some unexplained mechanisms other than pmrHFIJKLM and pmrCAB might be involved in mediating colistin resistance in K. pneumoniae, which warrants further investigation.

In conclusion, our findings identified that Gln30∗ substitution in MgrB is responsible for the upregulation of PhoP/PhoQ signaling system and of the pmrD gene that confers colistin resistance in K. pneumoniae. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report to provide direct in vivo evidence that the alteration of MgrB confers colistin resistance in a carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae isolate in China.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/supplementary material.

Author Contributions

ZR, JZ, and XX designed the experiments. YK, CL, and HC performed the experiments. ZR, WZ, and QS analyzed the data. YK and ZR wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81871696 and 82072342) and Zhejiang Provincial Medical and Health Science and Technology Plan (2021KY943).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Aires, C. A., Pereira, P. S., Asensi, M. D., and Carvalho-Assef, A. P. (2016). mgrB Mutations Mediating polymyxin B resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from rectal surveillance swabs in Brazil. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 60, 6969–6972. doi: 10.1128/aac.01456-16

Caniaux, I., van Belkum, A., Zambardi, G., Poirel, L., and Gros, M. F. (2017). MCR: modern colistin resistance. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 36, 415–420. doi: 10.1007/s10096-016-2846-y

Cannatelli, A., D’Andrea, M. M., Giani, T., Di Pilato, V., Arena, F., Ambretti, S., et al. (2013). In vivo emergence of colistin resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae producing KPC-type carbapenemases mediated by insertional inactivation of the PhoQ/PhoP mgrB regulator. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57, 5521–5526. doi: 10.1128/aac.01480-13

Cannatelli, A., Giani, T., D’Andrea, M. M., Di Pilato, V., Arena, F., Conte, V., et al. (2014). MgrB inactivation is a common mechanism of colistin resistance in KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae of clinical origin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58, 5696–5703. doi: 10.1128/aac.03110-14

Cheung, C. H. P., Heesom, K. J., and Avison, M. B. (2020). Proteomic investigation of the signal transduction pathways controlling colistin resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 64, e00790–20.

Feng, Y., Zou, S., Chen, H., Yu, Y., and Ruan, Z. (2021). BacWGSTdb 2.0: a one-stop repository for bacterial whole-genome sequence typing and source tracking. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, D644–D650.

Ga, L. M., Guldimann, C., Sullivan, G., Henderson, L. O., and Wiedmann, M. (2019). Identification of novel mobilized colistin resistance gene mcr9 in a multidrug-resistant, colistin-susceptible Salmonella enterica serotype typhimurium isolate. mBio 10, e000853–19.

Giamarellou, H. (2016). Epidemiology of infections caused by polymyxin-resistant pathogens. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 48, 614–621. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2016.09.025

Haeili, M., Javani, A., Moradi, J., Jafari, Z., Feizabadi, M. M., and Babaei, E. (2017). MgrB Alterations mediate colistin resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from Iran. Front. Microbiol. 8:2470.

Hamel, M., Chatzipanagiotou, S., Hadjadj, L., Petinaki, E., Papagianni, S., Charalampaki, N., et al. (2020). Inactivation of mgrB gene regulator and resistance to colistin is becoming endemic in carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in Greece: a nationwide study from 2014 to 2017. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 55, 105930. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105930

Jayol, A., Poirel, L., Brink, A., Villegas, M. V., Yilmaz, M., and Nordmann, P. (2014). Resistance to colistin associated with a single amino acid change in protein PmrB among Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates of worldwide origin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58, 4762–4766. doi: 10.1128/aac.00084-14

Lippa, A. M., and Goulian, M. (2009). Feedback inhibition in the PhoQ/PhoP signaling system by a membrane peptide. PLoS Genet 5:e1000788. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000788

Liu, Y.-Y., Wang, Y., Walsh, T. R., Yi, L.-X., Zhang, R., Spencer, J., et al. (2016). Emergence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mechanism MCR-1 in animals and human beings in China: a microbiological and molecular biological study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 16, 161–168. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(15)00424-7

Olaitan, A. O., Diene, S. M., Kempf, M., Berrazeg, M., Bakour, S., Gupta, S. K., et al. (2014a). Worldwide emergence of colistin resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae from healthy humans and patients in Lao PDR, Thailand, Israel, Nigeria and France owing to inactivation of the PhoP/PhoQ regulator mgrB: an epidemiological and molecular study. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 44, 500–507. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2014.07.020

Olaitan, A. O., Morand, S., and Rolain, J. M. (2014b). Mechanisms of polymyxin resistance: acquired and intrinsic resistance in bacteria. Front. Microbiol. 5:643.

Poirel, L., Jayol, A., Bontron, S., Villegas, M. V., Ozdamar, M., Turkoglu, S., et al. (2015). The mgrB gene as a key target for acquired resistance to colistin in Klebsiella pneumoniae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 70, 75–80. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku323

Poirel, L., Jayol, A., and Nordmann, P. (2017). Polymyxins: antibacterial activity, susceptibility testing, and resistance mechanisms encoded by plasmids or chromosomes. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 30, 557–596. doi: 10.1128/cmr.00064-16

Ruan, Z., and Feng, Y. (2016). BacWGSTdb, a database for genotyping and source tracking bacterial pathogens. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, D682–D687.

Ruan, Z., Yu, Y., and Feng, Y. (2020). The global dissemination of bacterial infections necessitates the study of reverse genomic epidemiology. Brief. Bioinform. 21, 741–750. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbz010

Tatusova, T., DiCuccio, M., Badretdin, A., Chetvernin, V., Nawrocki, E. P., Zaslavsky, L., et al. (2016). NCBI prokaryotic genome annotation pipeline. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, 6614–6624. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw569

Tzouvelekis, L. S., Markogiannakis, A., Psichogiou, M., Tassios, P. T., and Daikos, G. L. (2012). Carbapenemases in Klebsiella pneumoniae and Other Enterobacteriaceae: an evolving crisis of global dimensions. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 25, 682–707. doi: 10.1128/cmr.05035-11

van Duin, D., and Doi, Y. (2017). The global epidemiology of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Virulence 8, 460–469. doi: 10.1080/21505594.2016.1222343

Keywords: Klebsiella pneumoniae, colistin resistance, mgrB, complementation, whole genome sequencing

Citation: Kong Y, Li C, Chen H, Zheng W, Sun Q, Xie X, Zhang J and Ruan Z (2021) In vivo Emergence of Colistin Resistance in Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae Mediated by Premature Termination of the mgrB Gene Regulator. Front. Microbiol. 12:656610. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.656610

Received: 21 January 2021; Accepted: 28 May 2021;

Published: 21 June 2021.

Edited by:

Annamari Heikinheimo, University of Helsinki, FinlandReviewed by:

Qiong Chen, Hangzhou First People’s Hospital, ChinaHaijian Zhou, National Institute for Communicable Disease Control and Prevention (China CDC), China

Copyright © 2021 Kong, Li, Chen, Zheng, Sun, Xie, Zhang and Ruan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zhi Ruan, cl96QHpqdS5lZHUuY24=; Jun Zhang, amFtZXN6aGFuZzIwMDBAemp1LmVkdS5jbg==; Xinyou Xie, c2NvdHR4aWVAemp1LmVkdS5jbg==

Yingying Kong

Yingying Kong Chao Li

Chao Li Xinyou Xie

Xinyou Xie Jun Zhang

Jun Zhang Zhi Ruan

Zhi Ruan