- 1Department of Gastroenterology, The First Affiliated Hospital, Jinan University, Guangzhou, China

- 2School of Biomedical Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, Hong Kong

- 3Department of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Infectious Diseases, University Hospital Tübingen, Tübingen, Germany

Imbalance of gut microbiota can induce or aggravate intestinal inflammation. To enhance our understanding of the molecular mechanisms of gut microbiota and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), we studied the role of repulsive guidance molecule b (RGMb) in gut microbiota and colitis in mice. We generated Rgmb knockout mice and inducible Rgmb knockout mice and induced colitis using dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) in these mice. 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) high-throughput sequencing was performed to acquire the gut microbiota composition and abundance. We found that Rgmb deficiency significantly altered the diversity of gut microbiota and also induced dysbiosis. In sharp contrast to the balanced distribution of various bacteria in control mice, Prevotellaceae was almost exhausted in Rgmb-deficient mice under both basal and inflammatory conditions. Correlation analysis indicated that Prevotellaceae was negatively associated with inflammation in Rgmb-deficient mice with colitis. Similar results were obtained at the early inflammatory stage of colitis associated colon cancer (CAC). Taken together, our results reveal that Rgmb deficiency leads to dysbiosis of predominant gut microbiota under basal and inflammatory conditions. Rgmb-deficiency-mediated Prevotellaceae loss may render mice more susceptible to intestinal inflammation. Therefore, RGMb may be a novel potential target for reconstruction of the gut microbiota for the treatment of IBD.

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) including ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD) can be induced by multiple causes (Feuerstein et al., 2020; Torres et al., 2020). In addition to the environmental, genetic, and immune factors, dysbiosis of microbiota has been found to contribute to the initiation and development of IBD (Aschard et al., 2019; Lloyd-Price et al., 2019; Ansari et al., 2020). Accumulating evidence demonstrates that IBD is associated with altered gut microbiome and immune abnormalities (Chen et al., 2014; Imhann et al., 2018; Franzosa et al., 2019). Rebuilding the normal gut microbiota has become a new strategy for the IBD treatment. Specific genetic deficiency weakens the mucosal defense ability and increases the susceptibility to colitis. Although the important role of gut microbiota has been widely accepted, the mechanisms of dysbiosis are not fully understood. Exploring the genetic contributions to gut microbiota contributes to our understanding of the mechanisms underlying IBD development (Aschard et al., 2019).

Intestinal chronic inflammation is an established risk factor for colorectal cancer (CRC) in patients with IBDs. With the colitis progression and the mucosal epithelial barrier injury, the risk of CRC increases (Dupaul-Chicoine et al., 2010). Inflammatory epithelial cells produce reactive oxygen species, which affect carcinogenesis-related genes and proteins via genetic or epigenetic modifications (Chiba et al., 2012; Aviello et al., 2019). The intestinal epithelium is exposed to a huge burden of foreign antigens and various microorganisms, which collectively contribute to the development of intestinal inflammation into carcinoma (Plichta et al., 2019).

Repulsive guidance molecule b (RGMb/Dragon) is a member of RGM family, which consists of RGMa, RGMb, and RGMc. RGMb is a co-receptor for bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) (Xia et al., 2007). Previously, we found that RGMb was highly expressed in macrophages, and RGMb is an important negative regulator of IL-6 expression in immune cells (Xia et al., 2011). RGMb promoted CRC via the Erk1/2-BMP4-Smad1/5/8 pathways and induced oxaliplatin resistance by inhibiting JNK and p38 MAPK activation (Shi et al., 2015, 2016).

RGMb is highly expressed in normal resting lung interstitial macrophages and alveolar epithelial cells, whereas programmed death ligand-2 (PD-L2) is expressed in lung dendritic cells. It has been reported that PD-L2 and BMP-2/4 bind to distinct sites on RGMb (Xiao et al., 2014). Blockade of the interaction between RGMb and PD-L2 markedly interfered with the initial T cell expansion required for respiratory tolerance and impaired the development of respiratory tolerance. PD-1 inhibits antitumor immunity, while RGMb regulates respiratory immunity (Xiao et al., 2014; Ohaegbulam et al., 2015). PD-L2 binds to both PD-1 and RGMb. These observations suggest that RGMb may play an important role in immune and inflammatory disorders. In the present study, we examined the gut microbiota in Rgmb-deficient mice under basal conditions, and after induction of colitis, we found dysbiosis of gut microbiota in those mice. Our results suggest that RGMb plays an important role in controlling microbiota homeostasis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics Statement

All procedures involving experimental animals were performed in accordance with protocols that were approved by the Ethics Committee for Animal Research of Jinan University, Guangzhou, China (No. IACUC-20180316-01) and complied with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH publication No. 86-23, revised in 1985).

Global Rgmb Knockout Mice

Rgmbflox/flox mice on C57BL/6 background have been described (Liu et al., 2018). Stra8-icre mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Stock No: 017490). In the Stra8-icre transgenic line, cre is expressed in pre-meiotic germ cells. To obtain global Rgmb knockout (gKO) mice, Rgmbflox/flox mice were mated with Stra8-icre mice to Rgmbflox/wt; Stra8-icre mice, which then were intercrossed to obtain heterozygous gKO. Heterozygous animals were bred to obtain heterozygous and homozygous Rgmb-null (RgmbgKO) mice. Mice were housed under specific pathogen-free (SPF) conditions with a light/dark cycle of 12/12 h.

Inducible Rgmb Knockout Mice

Inducible knockout mice (igKO) were obtained by crossbreeding of Rgmbflox/flox with ROSA26-CreERT2 mice on the C57BL/6 background. Customized food pellets with Tamoxifen (Sigma–Aldrich, T5648), with a concentration of 500 mg Tamoxifen/1 kg pellets, were provided to induce global deletion of the Rgmb gene.

DSS-Induced Colitis in Mice

The inducible Rgmb knockout and control mice were free to drink fresh 3% (w/v) dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) (31404, Sigma) solution continuously for 7 days to induce colitis. Control mice were free to drink distilled water only. Body weights and disease activity index (DAI) were monitored. Serum and colon tissues were harvested for analysis.

AOM/DSS-Induced Colitis Associated Colon Cancer in Mice

Mice were injected intraperitoneally with AOM at a dose of 12.5 mg/kg body weight. One week after the injection, 3% DSS was administered to mice via their drinking water for 7 days, and they then were switched to normal drinking water for 16 days. The treatments were repeated for three cycles.

Immunohistochemical Staining

Colon tissue samples were formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded, and sectioned. Antigen was retrieved by Citrate Antigen Retrieval solution (Maxim, Fuzhou, China). Sections were treated with peroxidase and blocked with 10% donkey serum. The sections were incubated with the RGMb antibody (AF3630, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, United States) overnight at 4°C. After washes, the sections were incubated with anti-goat secondary antibodies (HAF109, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, United States) and DAB Detection Kit (Maxim, Fuzhou, China) before they were counterstained with hematoxylin.

ELISA

Serum was collected from DSS-induced colitis mice and measured using the IL-10 (EMC005.48), IL-6 (EMC004.48), TNF-α (EMC102a.48), and INF-γ (EMC101g.48) ELISA kits (Neobioscience, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Detection reagents A and B were added following the substrate solution, and the reaction was terminated with the STOP solution. The absorbance at 450 nm was measured using a microplate reader.

Fecal Sample Collection and DNA Extraction

Fresh feces were collected from heterozygous RgmbgKO (Rgmb±) and wildtype (Rgmb+/+) mice at 10 weeks of age, and from RgmbigKO and control mice after the end of Tamoxifen administration. Each fecal sample was pooled from five littermates. DNAs of fecal samples were extracted using QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit (Qiagen, DE). Quality of the extracted DNAs was evaluated by 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis in Tris-Acetate-EDTA buffer. DNA samples were stored at −20°C until library preparation and 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) sequencing.

Library Preparation and 16S rRNA Sequencing

The V4 hypervariable region of the bacterial 16S rRNA was amplified with the forward primer 515F (5′-GTGYCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA-3′) and the reverse primer 806R (5′-GGACTACNVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′) using KAPA HiFi HotStart ReadyMix (KAPA Biosystems, United States). The PCR products were purified using an AxyPrep PCR Cleanup Kit (Axygen, United States) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Paired-end sequencing was performed using Illumina FC-420-1004 MiniSeq Mid Output Kit (Illumina, United States) based on an Illumina MiniSeq System (Illumina, United States).

The raw paired-end reads were assembled and merged by FLASH (Magoc and Salzberg, 2011; Zhang et al., 2019). The PCR primers were subsequently truncated by cutadapt (Martin, 2011). The quality-controlled sequences were further chimerically removed and OUT-clustered by Usearch (Edgar, 2013). In detail, all reads were demultiplexed into one file, clustered at 97% similarity, and then the chimera checking was performed using UCHIME in reference mode. Representative sequences were generated, singletons were removed, and then a final operational taxonomic unit (OTU) table was created. The representative sequences of OTU were aligned on the Silva database for taxonomic classification by RDP Classifier.

Bioinformatics and Statistical Analyses

Alpha-diversity (α-diversity) metrics [ACE, Shannon and Pielou’s evenness index (J)] and beta-diversity (β-diversity) metrics [principal component analysis (PCA)] were all performed by R package vegan (version 2.5-5) (Oksanen et al., 2015). The taxa abundance in different levels was measured and plotted using ggplot2 (Wickham, 2009). LEfSe analysis was performed to identify taxa with differentiating abundance in the different group with LEfSe1.0 (Segata et al., 2011). The differential bacteria taxa in different groups were screened by wilcox.test with the P-value adjustment method FDR. ANOVA tests were either conducted by a one-way test or pairwise t-test with the P-value adjusted to the “BH” method for multiple comparisons or the Bartlett’s test using the equal variance and Duncan’s method (package laercio) to group differences. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was statistically analyzed by IBM SPSS statistics 25.0.

Statistical analysis for non-genomics data was performed using SPSS 21.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). Data between two groups were compared by using Student’s t-test (means ± standard deviation). Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) is used to analyze the correlation between two variables. All of the values are expressed as the mean ± SD of at least three independent experiments performed in triplicate, and P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Graphs were plotted using GraphPad Prism 8 software (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, United States).

Data Availability

The 16S sequencing raw reads of this research are available on the NCBI SRA. The accession number for the 16S rRNA sequencing data reported in this paper is NCBI SRA: PRJNA690936.

Results

Rgmb-Deficiency Exacerbated Colitis in Mice

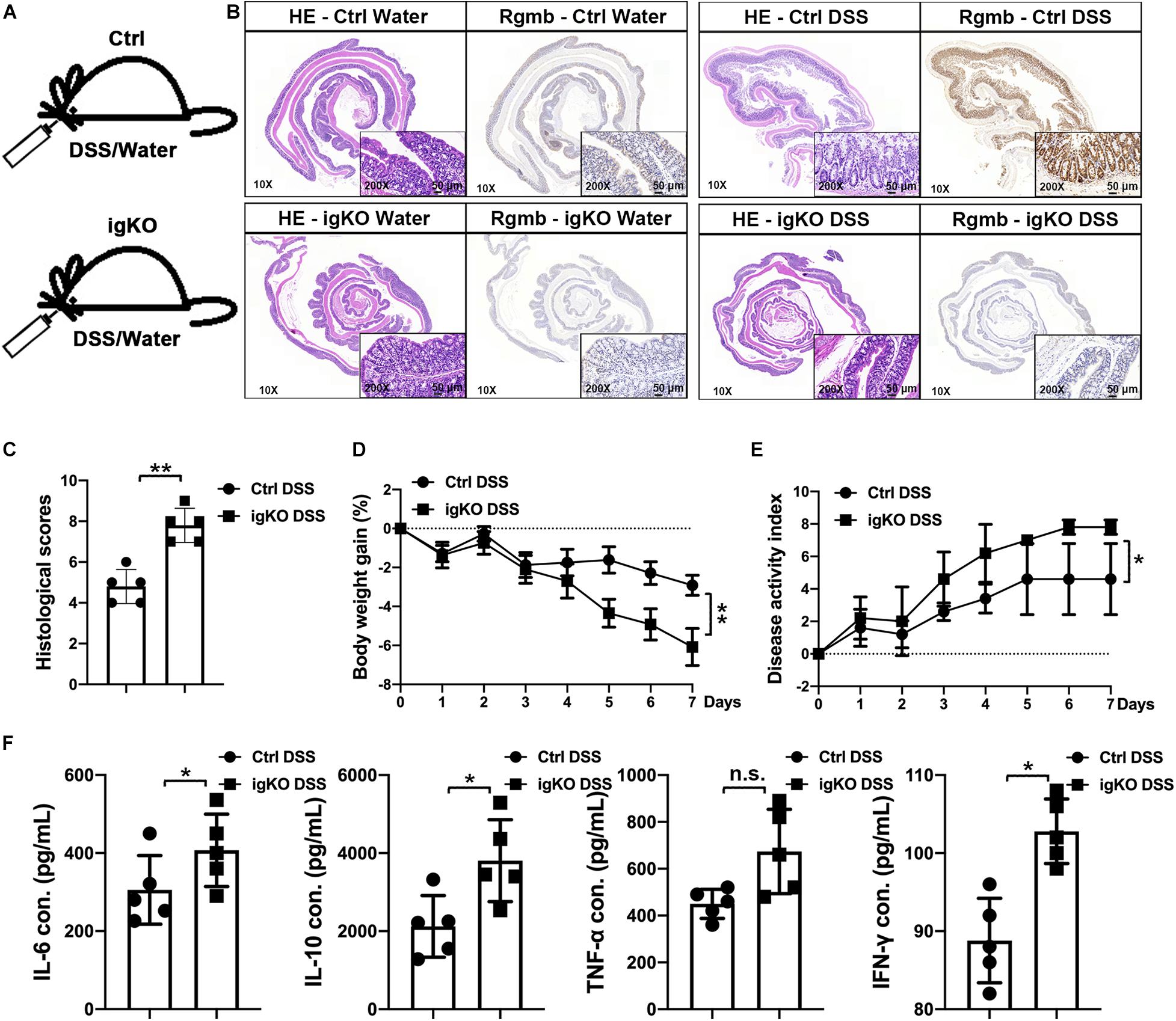

In order to explore the role of Rgmb in colitis, we induced colitis in Rgmb-deficient (RgmbigKO, Supplementary Figure 1a) and control mice using 3% DSS in drinking water for 7 consecutive days (Figure 1A). Immunohistochemistry showed that naive control mice exhibited RGMb expression in both epithelial and parenchymal cells, while this expression was absent in Rgmb-deficient mice. Consistent with our previous observation (Shi et al., 2015), RGMb expression in the colonic epithelial cells was increased after DSS treatment in control mice (Figure 1B). Histological examination demonstrated a loss of crypts, infiltration of inflammatory cells into the mucosa and submucosa, and edema of the submucosa in control mice, and these phenotypes were much more severe in Rgmb-deficient mice. Mucosal injury scores were dramatically increased in Rgmb-deficient mice compared with control mice (Figure 1C). Body weights were much more decreased in Rgmb-deficient mice than in control mice as the colitis progressed (Figure 1D). DAI of Rgmb-deficient mice was dramatically increased compared with control mice (Figure 1E). After 7 days of DSS administration, colitis was observed in both Rgmb-deficient and control mice. Serum concentrations of IL-6, IL-10, TNF-α (P = 0.05), and INF-γ were higher in Rgmb-deficient mice than in control mice (Figure 1F). Thus, deletion of Rgmb exacerbated colitis.

Figure 1. More severe colitis in Rgmb-deficient mice. (A) The schematic diagram showing the protocol for induction of colitis by DSS in Rgmb-deficient (igKO) and control (Ctrl) mice. (B) H&E and IHC staining. H&E staining shows colon tissues of normal or colitis mice with or without DSS treatment. IHC staining indicates that Rgmb was expressed in the colons of control mice, but the signal was lost in Rgmb igKO colons. Brown color represents staining for RGMb protein. Blue represents the nuclei. (C) Histological scores of intestinal tissues of Rgmb-deficient and control mice with colitis. (D) Body weights of colitic Rgmb igKO and control mice. (E) DAI of colitic Rgmb igKO and control mice. (F) Serum concentrations of serum IL-6, IL-10, TNF-α, and INF-γ in colitic Rgmb igKO and control mice. n = 5, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and n.s., not significant.

Rgmb Deficiency Induced Dysbiosis of Gut Microbiota in Mice With Colitis

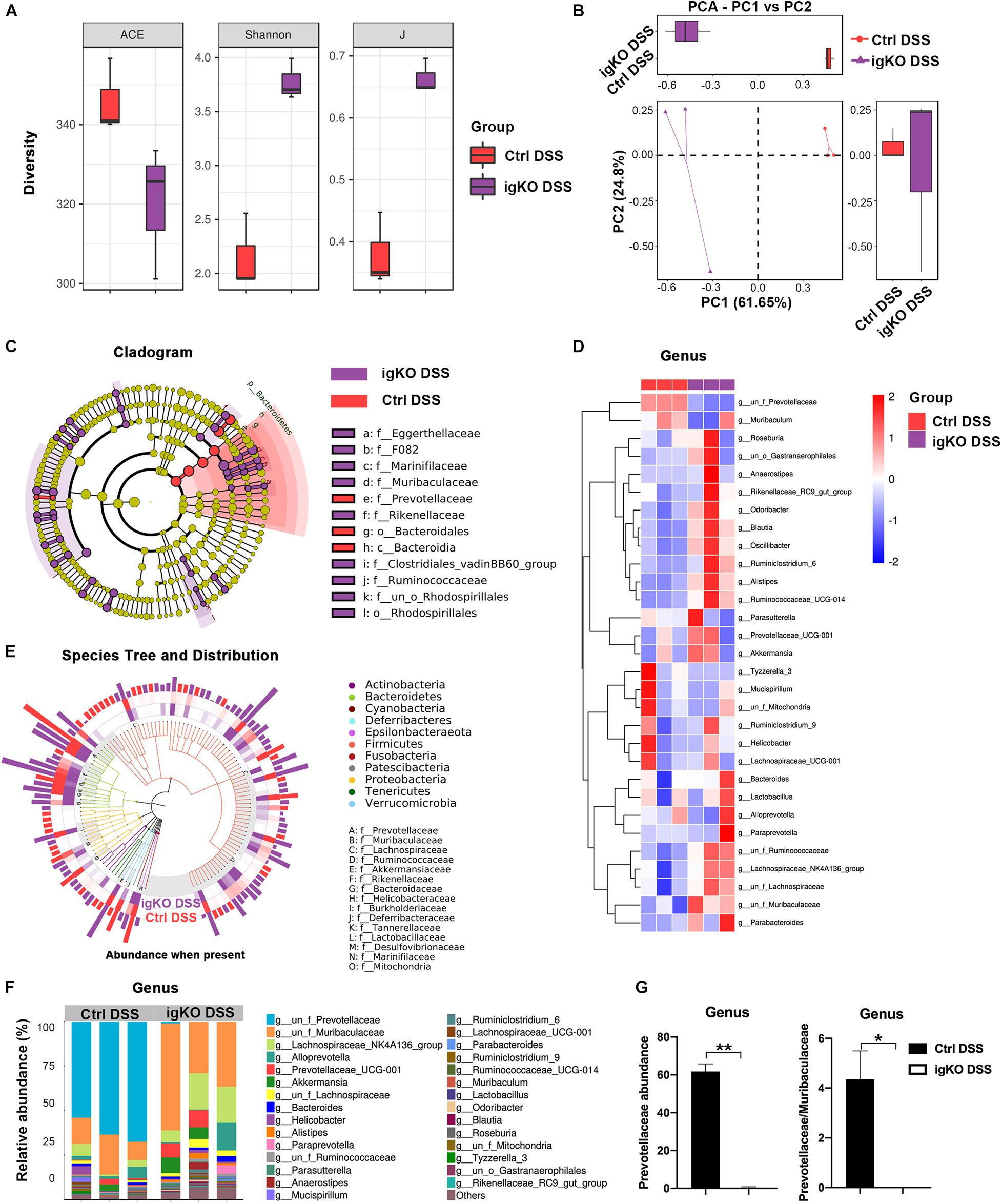

To understand the mechanisms by which Rgmb deficiency promoted colitis, we pooled fresh feces from littermates of Rgmb-deficient and control mice after colitis induction, and performed 16s rRNA gene sequencing for fecal microbiota. As shown by ACE index, reduced species and community richness were observed in Rgmb-deficient mice (Figure 2A). Shannon indexes indicated that more gut microbial diversities were captured with the current sequencing depth in Rgmb-deficient mice than in control mice. J index demonstrated a significant rise in species evenness in Rgmb-deficient mice (Figure 2A). Observed OTUs from weighted Unifrac PCA showed significant compositional discriminations of fecal microbiota between Rgmb-deficient and control mice (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. Dysbiosis of gut microbiota in colitic Rgmb-deficient mice. (A) Rgmb-deficiency altered α-diversity of gut microbiota in mice with colitis. (B) OTUs indicate significant compositional discriminations of fecal microbiota by PCA between Rgmb-deficient and control colitis mice. (C) The cladogram of evolution relationship between gut microbiota from Rgmb-deficient and control mice with colitis. (D) Heatmap represents the relative abundance of gut microbiota from Rgmb-deficient and control mice with colitis at genus level. (E) The species tree and distribution of gut bacterium at species level in Rgmb-deficient and control mice with colitis. (F) The relative abundance of gut microbiota in Rgmb-deficient and control mice with colitis at genus level. (G) The relative abundance of Prevotellaceae (left panel) and the ratio of Prevotellaceae to Muribaculaceae (right panel) in Rgmb-deficient and corresponding control mice with colitis at genus level. n = 3. Each fresh fecal sample was pooled from five littermate mice. ∗P < 0.05 and ∗∗P < 0.01.

Colitis associated bacterial taxa were determined by differential abundance analysis. Several bacterial OTUs were differentially abundant in Rgmb-deficient mice compared with control mice in different taxonomic ranks (Figures 2C,D). Moreover, bacterial richness was correspondingly altered by Rgmb-deficiency in colitic mice. We observed enrichments of Muribaculaceae, Lachnospiraceae, Ruminococcaceae, Akkermansiaceae, Rikenellaceae, Bacteroidaceae, Burkholderiaceae, Tannerellaceae, Lactobacillaceae, and Marinifilaceae, and reduction of Prevotellaceae, Helicobacteraceae, Deferribacteraceae, Desulfovibrionaceae, and Mitochondria in Rgmb-deficient colitis mice as shown by genus taxonomic rank (Figure 2E). Of note, depletion of Prevotellaceae was observed in Rgmb-deficient mice (Figures 2F,G, left panel). We also analyzed other bacteria and found that significant differences were only observed in Ruminococcaceae and Odoribacter (Supplementary Figure 2). Although there was no significant difference in Muribaculaceae, but the ratio of Prevotellaceae to Muribaculaceae was significantly reduced in Rgmb-deficient mice compared with control mice (Figure 2G, right panel). These results indicate that Rgmb deficiency leads to gut microbiota dysbiosis in DSS-induced colitis.

We also collected fresh feces from Rgmb-deficient or control mice under basal conditions for 16s rRNA gene sequencing. OTUs were differentially abundant in Rgmb-deficient mice compared with control mice in different taxonomic ranks, and bacterial richness was correspondingly changed (Supplementary Figures 1b,c). We also found enrichments of Muribaculaceae, Ruminococcaceae, Akkermansiaceae, Bacteroidaceae, Helicobacteraceae, Desulfovibrionaceae, Tannerellaceae, and Marinifilaceae, and reduction of Prevotellaceae, Lachnospiraceae, Burkholderiaceae, Rikenellaceae, Erysipelotrichaceae, Lactobacillaceae, and Mitochondria in Rgmb-deficient mice (Supplementary Figure 1d). Strikingly, depletion of Prevotellaceae and decreased ratio of Prevotellaceae to Muribaculaceae were observed in Rgmb-deficient mice even under basal conditions (Supplementary Figures 1e,f). These results indicate that Rgmb deficiency induces dysbiosis of gut microbiota in both normal and colitic mice.

Prevotellaceae Was Negatively Correlated With Inflammation in Rgmb-Deficient Mice With Colitis

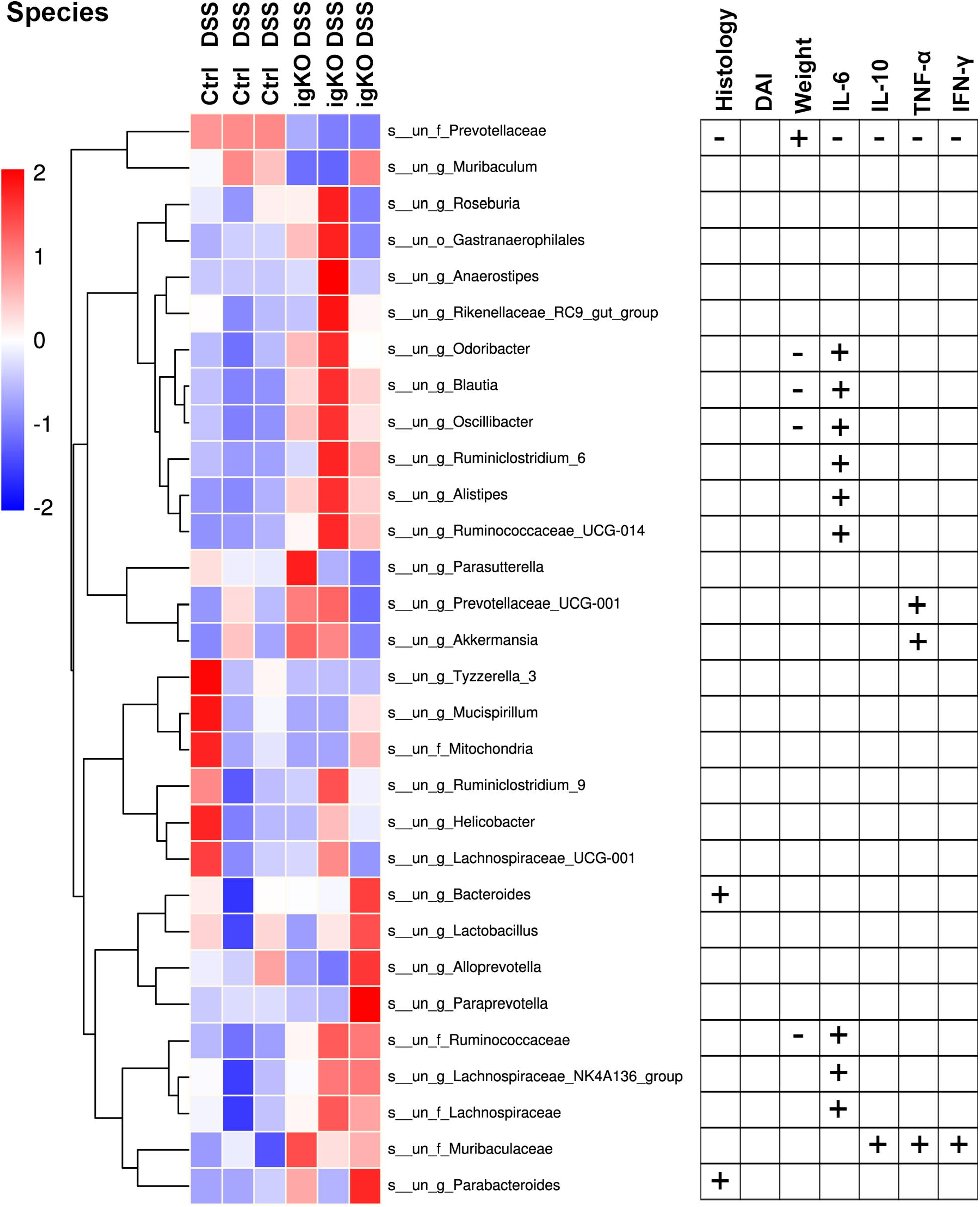

Since Prevotellaceae depletion was observed in Rgmb-deficient mice, we hypothesize that Prevotellaceae plays a role in colitis in Rgmb-deficient mice. We analyzed the correlation of Prevotellaceae abundance with colitis associated characteristics (Figure 3). The abundance of Prevotellaceae was negatively correlated with histological mucosal injury and inflammatory cytokines including IL-6, IL-10, TNF-α, and INF-γ, whereas positively associated with body weights.

Figure 3. Correlation analysis of bacterium abundance and colitis-associated characteristics. The heatmap of the alterations in gut microbiota between Rgmb-deficient and control mice with colitis (left panel). Statistical analyses on the correlations between differential bacteria and inflammation in Rgmb-deficient mice with colitis (right panel). Each fresh fecal sample was pooled from five littermate mice. + Positive correlation with statistical significance. - Negative correlation with statistical significance.

Correlation analyses were also performed between other fecal bacteria and inflammation in Rgmb-deficient mice with colitis (Figure 3 and Supplementary Table 1). We found that other bacteria were corrected with colitis-associated characteristics to various degrees. Muribaculaceae was positively correlated with serum IL-10, TNF-α, and INF-γ. Changes in Bacteroides and Parabacteroides were positively correlated with histological mucosal injury. Changes in Odoribacter, Blautia, Oscillibacter, and Ruminococcaceae were negatively correlated with body weights, whereas positively correlated with serum IL-6. Ruminiclostridium_6, Ruminococcaceae_UCG-014, Alistipes, Lachnospiraceae, and Lachnospiraceae_NK4A136_group were all positively correlated with serum IL-6. Prevotellaceae_UCG-001 and Akkermansia were positively correlated with serum TNF-α. These results further support the involvement of Prevotellaceae in the colitis in Rgmb-deficient mice.

Prevotellaceae Was Depleted at the Early Inflammatory Stage of Colitis Associated Colon Cancer in Rgmb-Deficient Mice

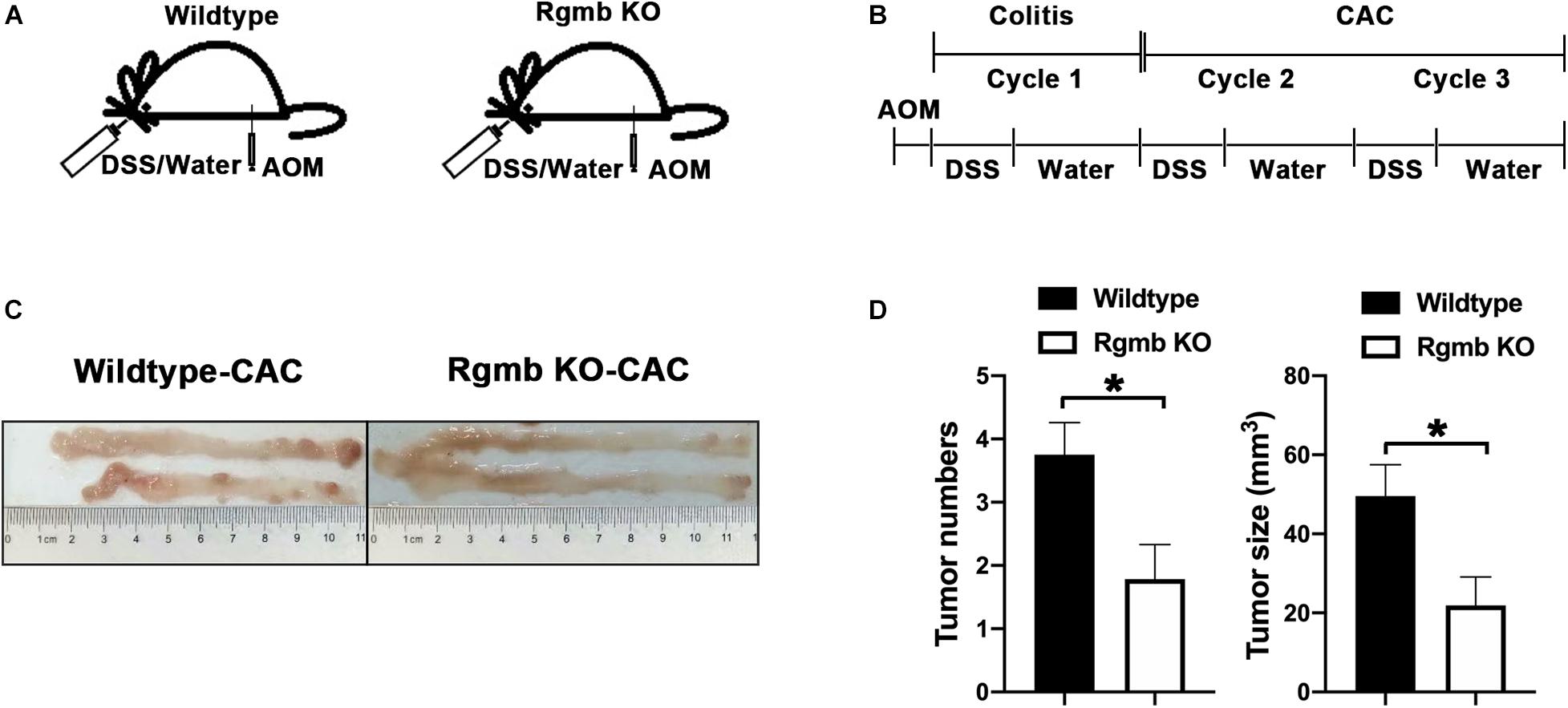

Since IBD is a precancerous condition, and colitis has a close relationship with colon cancer, we, therefore, induced colitis associated CRC (CAC) in Rgmb global knockout (RgmbgKO) and wildtype (Rgmb+/+) mice (Figure 4A and Supplementary Figure 3a). Since homozygous Rgmb knockout mice die within 2–3 weeks after birth (Xia et al., 2011), we used heterozygous Rgmb knockout mice. We analyzed heterozygous Rgmb knockout mice under basal conditions and observed depletion of Prevotellaceae and decreased ratio of Prevotellaceae to Muribaculaceae in heterozygous Rgmb knockout mice compared with wildtype mice (Supplementary Figures S3b,c). Analysis of similarities (ANOSIM) of the bacterial community composition showed that there was no difference in the baseline microbial community composition between global and inducible Rgmb knockout mice (Supplementary Figure 3d; R = −0.035, P = 0.496).

Figure 4. Reduced CAC formation in Rgmb-deficient mice. (A,B) The schematic diagrams showing the protocol for induction of CAC in heterozygous global Rgmb-knockout (Rgmb±) and wildtype (Rgmb+/+) mice. Cycle 1 represents the inflammatory stage before CAC formation. Cycle 2 represents the CAC formation stage following inflammatory conditions. (C) Macroscopic images of the AOM/DSS-induced tumors in Rgmb-knockout mice and wildtype littermates. (D) The histograms of tumor number and size of CAC tissues. n = 9 and *P < 0.05.

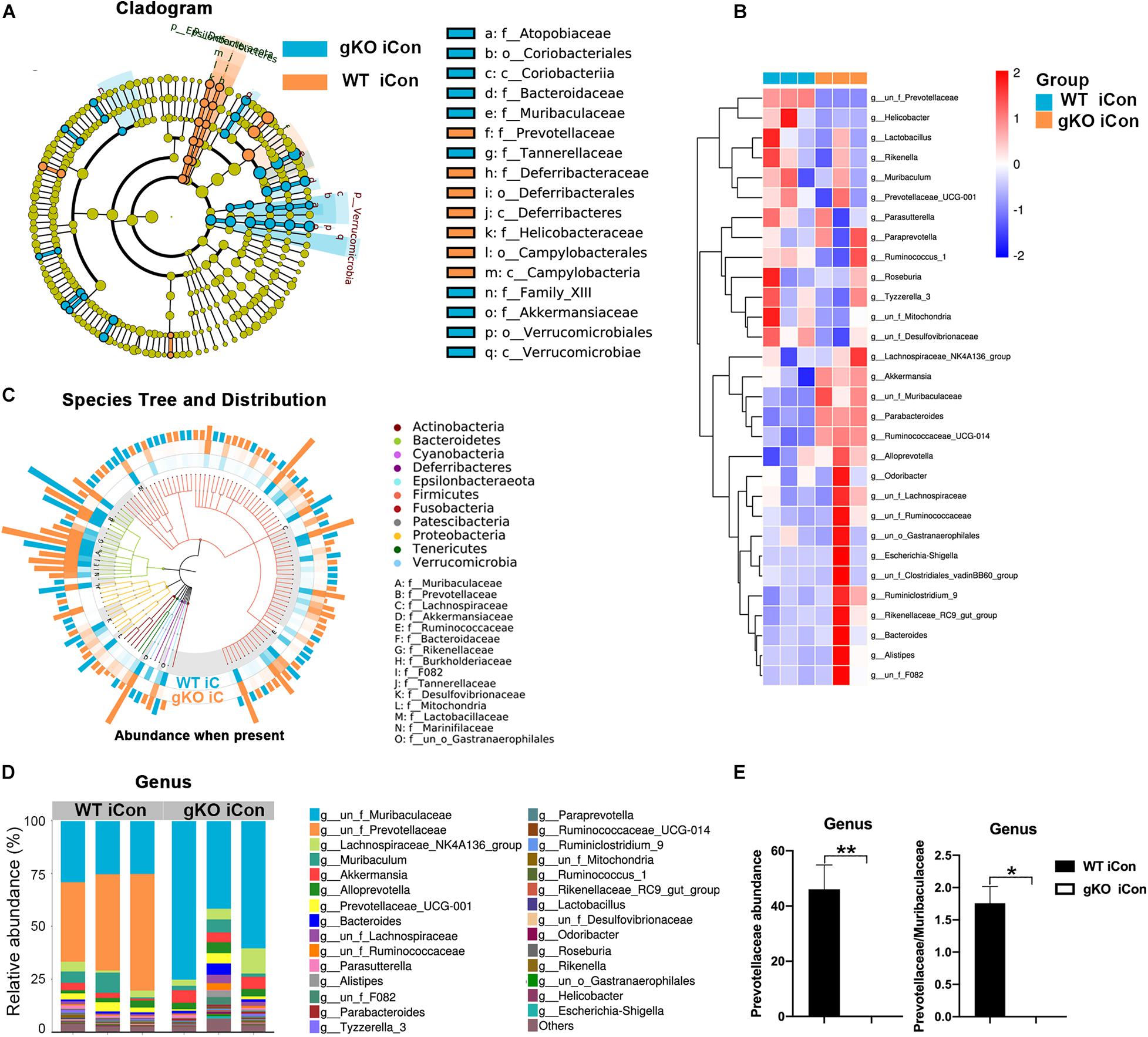

We then induced CAC by three cycles of DSS following intraperitoneal injection of AOM (Figure 4B). Based on the effects of Rgmb deficiency on the gut microbiota in the DSS model, we expected to see increased CAC formation in Rgmb KO mice. To our surprise, Rgmb knockout mice showed decreases in tumor number and size (Figures 4C,D) compared to wildtype mice. We, therefore, asked whether the gut microbiota were differentially regulated by RGMb in the CAC model than in DSS model. To test this notion, we analyzed the gut microbiota at different time points of the CAC induction. We first collected fresh feces for 16S rRNA sequencing after completion of the first cycle of DSS treatment, a stage when the mice were in the inflammatory condition. Observed OTUs indicated significant compositional discriminations of fecal microbiota between Rgmb KO and wildtype colitic mice. Several bacterial OTUs were differentially abundant in Rgmb-deficient mice compared with wildtype ones in different taxonomic ranks (Figures 5A,B). Moreover, bacterial richness was also altered in Rgmb-deficient mice. Enrichments of Muribaculaceae, Akkermansiaceae, Bacteroidaceae, Rikenellaceae, F082, Tannerellaceae, and Marinifilaceae and Gastranaerophilales, and reduction of Prevotellaceae, Lachnospiraceae, Ruminococcaceae, Burkholderiaceae, Desulfovibrionaceae, Mitochondria, and Lactobacillaceae were found in Rgmb-deficient mice (Figure 5C). Importantly, the depletion of Prevotellaceae and the decreased ratio of Prevotellaceae to Muribaculaceae were observed in Rgmb-deficient mice (Figures 5D,E). These results suggest that there are similar alterations in Rgmb-deficient mice between DSS treatment and the early stage of CAC.

Figure 5. Dysbiosis of gut microbiota in global Rgmb knockout mice at the inflammatory stage of CAC. (A) The cladogram of evolution relationship between gut microbiota from heterozygous global Rgmb knockout (Rgmb±) and wildtype (Rgmb+/+) mice at the inflammatory stage of CAC. (B) Heatmap on the relative abundance of gut microbiota from global Rgmb knockout and control mice at the inflammatory stage of CAC. (C) The species tree and distribution of gut bacterium at species level. (D) The relative abundance of gut microbiota at genus level. (E) The relative abundance of Prevotellaceae (left panel) and the ratio of Prevotellaceae to Muribaculaceae (right panel) at genus level. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01.

We then analyzed the gut microbiota after completion of the three cycles of DSS treatments when CAC are at advanced stages. The abundance of Prevotellaceae and the ratio of Prevotellaceae to Muribaculaceae were no longer different between Rgmb knockout and wildtype CAC mice (Supplementary Figures 3e,f). These results suggest that Rgmb-deficiency leads to Prevotellaceae deletion and gut microbiota dysbiosis during the early stage but not at the late stage of CAC.

DISCUSSION

Inflammatory bowel disease including UC and CD manifests as relapsing and remitting mucosal inflammation, which may result in progressive bowel damage. IBD symptoms such as strictures, fistula, and abscesses have substantial impacts on a patient’s quality of life. In the most severe cases, IBD may cause morbidity (Feuerstein et al., 2020; Torres et al., 2020). However, the precise etiology of IBD remains incompletely understood. Accumulating evidence demonstrated that dysbiosis of fecal and mucosa-associated microbiota plays a role in the occurrence and development of IBD (Chen et al., 2014; Franzosa et al., 2019). IBD presents altered gut microbiome and immune abnormalities (Schirmer et al., 2019). Rebuilding the normal gut microbiota has become a new strategy for the IBD treatment (Yilmaz et al., 2019; Sokol et al., 2020).

As a BMP co-receptor, RGMb plays an important role in the intestinal tract. RGMb promoted CRC via Erk1/2-BMP4-Smad1/5/8 pathways and induced oxaliplatin resistance by inhibited JNK and p38 MAPK activation (Shi et al., 2015, 2016). Previous studies showed that RGMb is highly expressed in RAW264.7 and J774 macrophage cell lines to negatively regulate IL-6 expression in a BMP ligand-dependent manner. Furthermore, IL-6 is upregulated in macrophages and dendritic cells derived from whole lung tissue of Rgmb knockout mice compared to respective cells derived from wildtype littermates. These results indicate that RGMb is an important negative regulator of IL-6 expression in immune cells, and that Rgmb-deficient mice may be a useful model for exploring immune and inflammatory disorders in colon (Xia et al., 2011). Our present study showed that RGMb expression in the colon was increased by DSS stimulation. Rgmb deletion aggravated DSS-induced colitis. These results are consistent with our previous findings, and further support that RGMb exerts anti-inflammatory effects.

Programmed death ligand 2 is a ligand of PD-1. It has been reported that PD-L2 and BMP-2/4 bind to distinct sites on RGMb (Xiao et al., 2014). RGMb is highly expressed in normal resting lung interstitial macrophages and alveolar epithelial cells, whereas PD-L2 is expressed in lung dendritic cells (Larsen et al., 2019). Blockade of the interaction between RGMb and PD-L2 markedly interfered with the initial T cell expansion and impaired the development of respiratory tolerance. PD-1 inhibits antitumor immunity of T cells, while RGMb regulates respiratory immunity (Xiao et al., 2014; Ohaegbulam et al., 2015). Therefore, RGMb may be an important player in the PD-1 complexes. It would be very interesting to study whether the interaction of RGMb and PD-L2 plays a role in the altered gut microbiota and colitis.

In the inducible Rgmb KO mice, there were significant alterations in both α-diversity and β-diversity, exhaustion of Prevotellaceae, and dominance of Muribaculaceae in fecal microbiota. Importantly, these phenotypes observed in RgmbigKO were also found in our global Rgmb knockout (RgmbgKO) mice. These results collectively suggest that Rgmb deficiency leads to dysbiosis of gut microbiota under basal conditions.

RgmbigKO showed a considerable variation of species and community richness in colitis induced by DSS. The shifted dominance of bacteria observed under basal conditions persisted in RgmbigKO mice even after induction of colitis, which was associated with more severe colitis in RgmbigKO mice. Prevotellaceae was almost exhausted at species, family, and genus levels in Rgmbigko mice. Three enterotypes (robust clusters) of the human gut microbiome have been identified by the different levels of one of three genera: Bacteroides (Enterotype 1), Prevotella (Enterotype 2), and Ruminococcus (Enterotype 3), which are mostly driven by species composition (Arumugam et al., 2011; Gorvitovskaia et al., 2016; Levy et al., 2020). Here, we demonstrated Rgmb-deficiency shifted the dominance from Prevotellaceae to Muribaculaceae, thus providing a good example of host and microbial communications, which may be useful to manipulate the host-microbial symbiotic states.

Prevotellaceae exhibited a negative correlation with inflammation in Rgmb-deficient mice with colitis. Furthermore, Prevotellaceae dominance even existed in Rgmb-deficient mice under basal conditions. Therefore, Prevotellaceae is very likely to be the cause instead of the consequence of the heightened colitis in Rgmb-deficient mice. Nevertheless, whether the shifted dominance of bacteria plays a role in the elevated colitis in Rgmb knockout mice remains to be further clarified.

Colitis has a close relationship with colon cancer; thus, we studied the effects of Rgmb deletion on CAC development using the AOM/DSS model. Rgmb-deficient mice had dramatic alterations in gut microbiota compared to wildtype mice during the early stage of CAC, and the alterations were similar to those observed in the DSS model. However, after the completion of the three cycles of when CAC are already formed, Prevotellaceae abundance was no longer different between Rgmb KO and wildtype mice. Therefore, RGMb may play a stage-dependent role in the gut microbiota during CAC development. Even more strikingly, the tumor number and size were reduced in Rgmb KO mice compared with wildtype mice. These results are paradoxical but suggest that some yet-to-be-determined autonomous effects of RGMb on colonic epithelial cells may have overridden the effects of RGMb on the gut microbiota. The molecular mechanisms of RGMb’s stimulatory effects on CAC are currently under active investigation in the laboratory.

Taken together, our results showed that Rgmb deletion led to gut microbiota dysbiosis and depletion of Prevotellaceae, and these changes may account for the elevated colitis.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are publicly available. These data can be found here: NCBI SRA and accession PRJNA690936, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA690936.

Ethics Statement

The animal study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee for Animal Research of Jinan University, Guangzhou, China.

Author Contributions

YS, YX, and ST conceived and designed the experiments. YX provided RGMb knockout mice. YS, LZ, and YL harvested mice and performed animal experiments. LZ, YL, and MW collected the fecal samples. YC and SF extracted the DNA. YS, YX, and ST analyzed the sequencing data and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (No. 2018A0303130302), Medical Science and Technology Foundation of Guangdong Province (Nos. A2018011 and A2021306), and Health and Medical Research Fund (HMRF), Hong Kong SAR Government (No. 04153586).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2021.648915/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Figure 1 | Rgmb-deficiency induced dysbiosis of gut microbiota in mice. (a) The schematic diagram represented inducible Rgmb knockout mice model. (b) The cladogram of evolution relationship between gut microbiota from Rgmb-deficient and control mice. (c) Heatmap represented the relative abundance of gut microbiota from Rgmb-deficient and control mice at genus level. (d) The species tree and distribution of gut bacterium at species level in Rgmb-deficient and control mice. (e) The relative abundance of gut microbiota in Rgmb-deficient and control mice at genus level. (f) The relative abundance of Prevotellaceae (left panel) and the ratio of Prevotellaceae to Muribaculaceae (right panel) in Rgmb-deficient and control mice at genus level. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01.

Supplementary Figure 2 | The relative abundance of gut microbiota in Rgmb-deficient and control mice at genus level. ∗P < 0.05, n.s., not significant.

Supplementary Figure 3 | The relative abundance of gut microbiota in Rgmb-deficient and wildtype CAC mice at genus level. (a) The schematic diagram represented Rgmb-knockout (Rgmb+/–) and wildtype (Rgmb+/+) mice model. (b) Heatmap represented the relative abundance of gut microbiota from Rgmb-deficient and wildtype mice at genus level. (c) The relative abundance of Prevotellaceae and the ratio of Prevotellaceae to Muribaculaceae in Rgmb-deficient and control mice at genus level. (d) Analysis of similarities (ANOSIM) between global Rgmb knockout and inducible Rgmb knockout mice. R = −0.035, P = 0.496. (e) Heatmap represented the relative abundance of gut microbiota from Rgmb-deficient and wildtype CAC mice at genus level. (f) The relative abundance of Prevotellaceae and the ratio of Prevotellaceae to Muribaculaceae in Rgmb-deficient and control CAC mice at genus level. ∗∗P < 0.01, n.s. not significant.

Supplementary Table 1 | Correlation statistics between gut microbiota and inflammation of Rgmb-deficient mice with colitis.

References

Ansari, I., Raddatz, G., Gutekunst, J., Ridnik, M., Cohen, D., Abu-Remaileh, M., et al. (2020). The microbiota programs DNA methylation to control intestinal homeostasis and inflammation. Nat. Microbiol. 5, 610–619. doi: 10.1038/s41564-019-0659-3

Arumugam, M., Raes, J., Pelletier, E., Le Paslier, D., Yamada, T., Mende, D. R., et al. (2011). Enterotypes of the human gut microbiome. Nature 473, 174–180.

Aschard, H., Laville, V., Tchetgen, E. T., Knights, D., Imhann, F., Seksik, P., et al. (2019). Genetic effects on the commensal microbiota in inflammatory bowel disease patients. PLoS Genet. 15:e1008018. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1008018

Aviello, G., Singh, A. K., O’neill, S., Conroy, E., Gallagher, W., D’agostino, G., et al. (2019). Colitis susceptibility in mice with reactive oxygen species deficiency is mediated by mucus barrier and immune defense defects. Mucosal. Immunol. 12, 1316–1326. doi: 10.1038/s41385-019-0205-x

Chen, L., Wang, W., Zhou, R., Ng, S. C., Li, J., Huang, M., et al. (2014). Characteristics of fecal and mucosa-associated microbiota in Chinese patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Medicine (Baltimore) 93:e51. doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000000051

Chiba, T., Marusawa, H., and Ushijima, T. (2012). Inflammation-associated cancer development in digestive organs: mechanisms and roles for genetic and epigenetic modulation. Gastroenterology 143, 550–563. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.07.009

Dupaul-Chicoine, J., Yeretssian, G., Doiron, K., Bergstrom, K. S., Mcintire, C. R., Leblanc, P. M., et al. (2010). Control of intestinal homeostasis, colitis, and colitis-associated colorectal cancer by the inflammatory caspases. Immunity 32, 367–378. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.02.012

Edgar, R. C. (2013). UPARSE: highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat. Methods 10, 996–998. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2604

Feuerstein, J. D., Isaacs, K. L., Schneider, Y., Siddique, S. M., Falck-Ytter, Y., Singh, S., et al. (2020). AGA clinical practice guidelines on the management of moderate to severe ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 158, 1450–1461.

Franzosa, E. A., Sirota-Madi, A., Avila-Pacheco, J., Fornelos, N., Haiser, H. J., Reinker, S., et al. (2019). Gut microbiome structure and metabolic activity in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat. Microbiol. 4, 293–305.

Gorvitovskaia, A., Holmes, S. P., and Huse, S. M. (2016). Interpreting prevotella and Bacteroides as biomarkers of diet and lifestyle. Microbiome 4:15.

Imhann, F., Vich Vila, A., Bonder, M. J., Fu, J., Gevers, D., Visschedijk, M. C., et al. (2018). Interplay of host genetics and gut microbiota underlying the onset and clinical presentation of inflammatory bowel disease. Gut 67, 108–119. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-312135

Larsen, T. V., Hussmann, D., and Nielsen, A. L. (2019). PD-L1 and PD-L2 expression correlated genes in non-small-cell lung cancer. Cancer Commun. (Lond) 39:30. doi: 10.1186/s40880-019-0376-6

Levy, R., Magis, A. T., Earls, J. C., Manor, O., Wilmanski, T., Lovejoy, J., et al. (2020). Longitudinal analysis reveals transition barriers between dominant ecological states in the gut microbiome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 117, 13839–13845. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1922498117

Liu, W., Chen, B., Wang, Y., Meng, C., Huang, H., Huang, X. R., et al. (2018). RGMb protects against acute kidney injury by inhibiting tubular cell necroptosis via an MLKL-dependent mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, E1475–E1484.

Lloyd-Price, J., Arze, C., Ananthakrishnan, A. N., Schirmer, M., Avila-Pacheco, J., Poon, T. W., et al. (2019). Multi-omics of the gut microbial ecosystem in inflammatory bowel diseases. Nature 569, 655–662.

Magoc, T., and Salzberg, S. L. (2011). FLASH: fast length adjustment of short reads to improve genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 27, 2957–2963. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr507

Martin, M. (2011). Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet. J. 7,, 10–12.

Ohaegbulam, K. C., Assal, A., Lazar-Molnar, E., Yao, Y., and Zang, X. (2015). Human cancer immunotherapy with antibodies to the PD-1 and PD-L1 pathway. Trends Mol. Med. 21, 24–33.

Oksanen, J., Blanchet, F. G., Kindt, R., Legendre, P., Minchin, P. R., O’hara, R. B., et al. (2015). Vegan: Community Ecology. Package Version: 2.5–7.

Plichta, D. R., Graham, D. B., Subramanian, S., and Xavier, R. J. (2019). Therapeutic opportunities in inflammatory bowel disease: mechanistic dissection of host-microbiome relationships. Cell 178, 1041–1056. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.07.045

Schirmer, M., Garner, A., Vlamakis, H., and Xavier, R. J. (2019). Microbial genes and pathways in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 17, 497–511. doi: 10.1038/s41579-019-0213-6

Segata, N., Izard, J., Waldron, L., Gevers, D., Miropolsky, L., Garrett, W. S., et al. (2011). Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol. 12:R60.

Shi, Y., Chen, G. B., Huang, X. X., Xiao, C. X., Wang, H. H., Li, Y. S., et al. (2015). Dragon (repulsive guidance molecule b, RGMb) is a novel gene that promotes colorectal cancer growth. Oncotarget 6, 20540–20554. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4110

Shi, Y., Huang, X. X., Chen, G. B., Wang, Y., Zhi, Q., Liu, Y. S., et al. (2016). Dragon (RGMb) induces oxaliplatin resistance in colon cancer cells. Oncotarget 7, 48027–48037. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10338

Sokol, H., Brot, L., Stefanescu, C., Auzolle, C., Barnich, N., Buisson, A., et al. (2020). Prominence of ileal mucosa-associated microbiota to predict postoperative endoscopic recurrence in Crohn’s disease. Gut 69, 462–472. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-318719

Torres, J., Bonovas, S., Doherty, G., Kucharzik, T., Gisbert, J. P., Raine, T., et al. (2020). ECCO guidelines on therapeutics in crohn’s disease: medical treatment. J. Crohns Colitis 14, 4–22.

Wickham, H. (2009). ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. Berlin: Springer Science & Business Media.

Xia, Y., Cortez-Retamozo, V., Niederkofler, V., Salie, R., Chen, S., Samad, T. A., et al. (2011). Dragon (repulsive guidance molecule b) inhibits IL-6 expression in macrophages. J. Immunol. 186, 1369–1376. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002047

Xia, Y., Yu, P. B., Sidis, Y., Beppu, H., Bloch, K. D., Schneyer, A. L., et al. (2007). Repulsive guidance molecule RGMa alters utilization of bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) type II receptors by BMP2 and BMP4. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 18129–18140. doi: 10.1074/jbc.m701679200

Xiao, Y., Yu, S., Zhu, B., Bedoret, D., Bu, X., Francisco, L. M., et al. (2014). RGMb is a novel binding partner for PD-L2 and its engagement with PD-L2 promotes respiratory tolerance. J. Exp. Med. 211, 943–959. doi: 10.1084/jem.20130790

Yilmaz, B., Juillerat, P., Oyas, O., Ramon, C., Bravo, F. D., Franc, Y., et al. (2019). Microbial network disturbances in relapsing refractory Crohn’s disease. Nat. Med. 25, 323–336. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0308-z

Keywords: Rgmb deficiency, colitis, gut microbiota, Prevotellaceae, intestinal mucosa

Citation: Shi Y, Zhong L, Li Y, Chen Y, Feng S, Wang M, Xia Y and Tang S (2021) Repulsive Guidance Molecule b Deficiency Induces Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis and Increases the Susceptibility to Intestinal Inflammation in Mice. Front. Microbiol. 12:648915. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.648915

Received: 02 January 2021; Accepted: 25 March 2021;

Published: 28 April 2021.

Edited by:

Spyridon Ntougias, Democritus University of Thrace, GreeceReviewed by:

Caio Tavares Fagundes, Federal University of Minas Gerais, BrazilThomas Secher, Université de Tours, France

Copyright © 2021 Shi, Zhong, Li, Chen, Feng, Wang, Xia and Tang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yin Xia, WGlhLllpbkBjdWhrLmVkdS5oaw==; Shaohui Tang, dGFuZ3NoYW9odWkyMDZAam51LmVkdS5jbg==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Ying Shi

Ying Shi Lu Zhong1†

Lu Zhong1† Yin Xia

Yin Xia Shaohui Tang

Shaohui Tang