94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Microbiol. , 02 September 2020

Sec. Antimicrobials, Resistance and Chemotherapy

Volume 11 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2020.568510

Background: Bacterial biofilms are known to have high antibiotic tolerance which directly affects clearance of bacterial infections in people with cystic fibrosis (CF). Current antibiotic susceptibility testing methods are either based on planktonic cells or do not reflect the complexity of biofilms in vivo. Consequently, inaccurate diagnostics affect treatment choice, preventing bacterial clearance and potentially selecting for antibiotic resistance. This leads to prolonged, ineffective treatment.

Methods: In this study, we use an ex vivo lung biofilm model to study antibiotic tolerance and virulence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Sections of pig bronchiole were dissected, prepared and infected with clinical isolates of P. aeruginosa and incubated in artificial sputum media to form biofilms, as previously described. Then, lung-associated biofilms were challenged with antibiotics, at therapeutically relevant concentrations, before their bacterial load and virulence were quantified and detected, respectively.

Results: The results demonstrated minimal effect on the bacterial load with therapeutically relevant concentrations of ciprofloxacin and meropenem, with the latter causing an increased production of proteases and pyocyanin. A combination of meropenem and tobramycin did not show any additional decrease in bacterial load but demonstrated a slight decrease in total proteases and pyocyanin production.

Conclusion: In this initial study of six clinical isolates of P. aeruginosa showed high levels of antibiotic tolerance, with minimal effect on bacterial load and increased proteases production, which could negatively affect lung function. Thus, the ex vivo lung model has the potential to be effectively used in larger studies of antibiotic tolerance in in vivo-like biofilms, and show how sub optimal antibiotic treatment of biofilms may potentially contribute to exacerbations and eventual lung failure. We demonstrate a realistic model for understanding antibiotic resistance and tolerance in biofilms clinically and for molecules screening in anti-biofilm drug development.

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a genetic disease in which people have decreased mucociliary clearance in the respiratory tract, due to mutations in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene, which encodes a chloride channel (Davies, 2002; Lyczak et al., 2002). This impairment leads to a reduction in mucus clearance and increased viscosity, resulting in accumulation of microbial cells, increased bacterial adherence and inflammation and the formation of bacterial biofilm (Davies, 2002; Lyczak et al., 2002; Hoiby et al., 2010). Biofilm infections are more difficult to eradicate due to the difference in their nature compared to non-biofilm infections; thus, they are lifelong infections in CF. These biofilm infections are characterized by acquiring distinctive resistance mechanisms compared with non-biofilm infections. There are three main mechanisms. First, there may be low antibiotic penetration into the biofilm due to the production of extracellular matrix. Second, the different bacterial metabolic states in the biofilm lead to increased phenotypic heterogeneity, affecting the success of treatment. Third, adaptive mechanisms controlling differential gene expression of multiple virulence factors, such as efflux pumps and antibiotic-degrading enzymes, lead to antibiotic tolerance (Breidenstein et al., 2011; Taylor et al., 2014). The latter is highly dependent and varies based on the environment surrounding the biofilm (Breidenstein et al., 2011).

In CF and other biofilm-based infections, antibiotic prescription is mainly based on standard minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) methods, despite these being based on planktonic cells (Bjarnsholt et al., 2013). The current antimicrobial susceptibility testing using planktonic-based diagnostics are suitable for detecting intrinsic and acquired stable resistance mechanisms; however, biofilm-based diagnostics will additionally detect environmentally induced and biofilm-associated resistance mechanisms. There is a drastic increase in antibiotic tolerance using biofilm-based diagnostics, such as the Calgary device, in comparison to MIC methods, demonstrating the limitation of using planktonic-based models for biofilm infections (Macia et al., 2014). Some of these in vitro biofilm models are robust for antibiotic susceptibility screening; they fail to recapitulate the complexity of biofilm infections, environment and host-dependent interactions (Bjarnsholt et al., 2013; Musken et al., 2017). All these factors affect the antibiotic susceptibility profile (Musken et al., 2017). Also, these biofilm models have not been developed to demonstrate antibiotic susceptibility profile in multi-species infections. Thus, if diagnostic tests fail to accurately detect in vivo antibiotic resistance, this will result in recurrent and complicated infections (Musken et al., 2017), and may lead to a vicious cycle of increased resistance.

In this study, we employed a previously developed ex vivo pig lung biofilm model (EVPL) (Harrison et al., 2014; Harrison and Diggle, 2016) for antibiotic susceptibility testing of CF P. aeruginosa isolates and compared it with standard MIC and the Calgary device assays. The effect of exposure to antibiotics on the virulence of P. aeruginosa was also assessed to demonstrate the clinical effect. Ciprofloxacin and meropenem were chosen as examples of clinically relevant antibiotic to which our CF isolates were either all classified as resistant (ciprofloxacin) or sensitive (meropenem) by standard planktonic MIC testing. Tobramycin was chosen as it is clinically combined with meropenem. The results demonstrated an increased antibiotic tolerance in the EVPL model at concentrations >25-fold the reported sputum concentrations when tested in Mueller-Hinton broth, which even further increased when tested in artificial sputum media. We also investigated the effect of exposure to antibiotics on bacterial virulence. Exposure to antibiotics showed an increased production of total proteases, which may have a role in lung damage. Normalized proteases/cfu and pyocyanin/cfu demonstrated an increased production of these virulence factors per cell. Current clinical prognosis in CF is alarming and creates an urgent need to develop effective anti-biofilm agents. Thus, we propose a unique approach to predict the true clinical effect of antibiotic treatments on bacterial clearance and associated virulence factors in CF using the EVPL model.

Six clinical CF Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates were used in this study, selected from a set of 44 isolates from a single sputum sample as they showed a range of phenotypes in in vitro assays (Darch et al., 2015). PA14 was used as a control laboratory strain for comparison.

Minimum inhibitory concentrations were performed according to the EUCAST guidelines (EUCAST, 2019). Briefly, bacterial isolates were cultured on Luria-Bertani (LB) agar overnight at 37°C, resuspended in Mueller-Hinton broth (MHB) to OD600 of 0.5 and diluted 1000 times. Meropenem (Sigma-Aldrich) and ciprofloxacin (Thermo Fisher) were two-fold serially diluted in MHB (256–0.0156 μg/mL), to a final volume of 50 μL in a 96-well plate (Corning). 50 μL of the diluted bacterial suspension (5 × 105 cfu/mL final concentration) was added to all wells and incubated for 18 h at 37°C before the minimum inhibitory concentrations were determined.

Minimum biofilm eradication and inhibitory concentrations (MBEC and MBIC, respectively) were performed using Calgary device (peg lids biofilm assay) according to Moskowitz et al. (2004). Briefly, 100 μL of bacterial suspensions at 0.5 McFarland were aliquoted in U shaped 96-well plates (Corning), covered with peg lids (Thermo Electron) and incubated for 20 h at 37°C to form biofilms on the pegs. Peg lids were then washed three times in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), transferred to 96-well antibiotic challenge plates containing 100 μL of 2-fold serially diluted meropenem or ciprofloxacin (128–0.25 μg/mL) and incubated for 18 h at 37°C. Peg lids were washed three times in sterile PBS, transferred to 96-well recovery plates containing 100 μL MHB and sonicated for 5 min. Peg lids were replaced with standard plate lids, measured for absorbance at 600 nm and incubated for 6 h at 37°C before checked for turbidity and OD600.

Dissection and infection of pig lungs were performed as described in Harrison et al. (Harrison and Diggle, 2016). Briefly, pig bronchioles were dissected, UV sterilized (using a Carlton germicidal cabinet with a G8T5-8 watt germicidal tube, generating shortwave ultra-violet radiation of 2537 å) and transferred to 24-well plates with 400 μL of 0.8% agarose/ASM [Artificial Sputum Medium (Palmer et al., 2007)] as a pad. Each bronchiole tissue was infected with the bacterial isolates using a sterile syringe then 500 μL of ASM were added to each well. Uninfected bronchiole tissues were used as negative controls. Plates were then covered with UV sterilized breathable membranes (Sigma-Aldrich) and incubated at 37°C for 7 days. Tissues were then washed in 500 μL of PBS, transferred to sterile bead tubes containing 1 gm of metal beads (2.4 mm, Fisher Scientific) and 1 mL of PBS, and homogenized using a FastPrep-24TM 5G homogenizer (MP Biomedicals) for 40 s at 4.0 m/sec. Biofilm homogenate was transferred to 96-well plates, serially diluted 10-fold and plated on LB agar plates for calculating the bacterial load.

For assessing the effect of different media, replicate infected tissues were treated with antibiotics by transferring the washed infected tissues to 48-well plates containing 300 μL of either MHB or ASM containing ciprofloxacin (Thermo Fisher), meropenem (Sigma), tobramycin (Thermo Fisher) or combination therapy at the specified concentrations and incubated at 37°C for 24 h. Antibiotic-treated tissues were then washed, homogenized and plated as previously described.

Total proteases were quantified according to Harrison et al. (2014). Briefly, 100 μL of tissue homogenate or surrounding ASM were added to 900 μL of azocasein solution (final concentration of 5 mg/mL dissolved in 100 mM Tris–HCl, 1 mM CaCl2) in a 2 mL tube and incubated for 15 min at 37°C with shaking at 170 rpm. Then, 500 μL of 10% trichloroacetic acid were added as a stopping solution, and tubes were centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 1 min at room temperature. 200 μL of the supernatant were transferred into a clean 96-well plate and the absorbance was measured at 400 nm. PBS was used as a negative control and a standard curve using proteinase K (Supplementary Figure S1) was used to estimate the total amount of proteases.

Total pyocyanin was quantified according to Saha et al. (2008) with minor modifications. Briefly, pyocyanin was extracted using chloroform in a ratio of 5:3. The chloroform mixture was vortexed for 2 min, then centrifuged at room temperature at 10,000 rpm for 5 min. The bottom layer was transferred to a new 2 mL tube and an equal volume of 0.2 M HCl was added. Tubes were vortexed for 2 min, centrifuged at room temperature at 10,000 rpm for 5 min and 200 μL of the top phase was transferred to a black 96-well plate and the absorbance was measured at 520 nm (Saha et al., 2008). The concentration of pyocyanin (μg/mL) was calculated by multiplying the OD520 by 17.072 (Essar et al., 1990).

All data were analyzed by ANOVA to test for the main effect and interactions of different lung, strains and antibiotic treatments using RStudio v1.1.463 (2009-2018 RStudio, Inc.). Unpaired t-tests were performed for pairwise statistical analysis using GraphPad Prism (v8.0.1) and the familywise error rate correction for multiple comparisons.

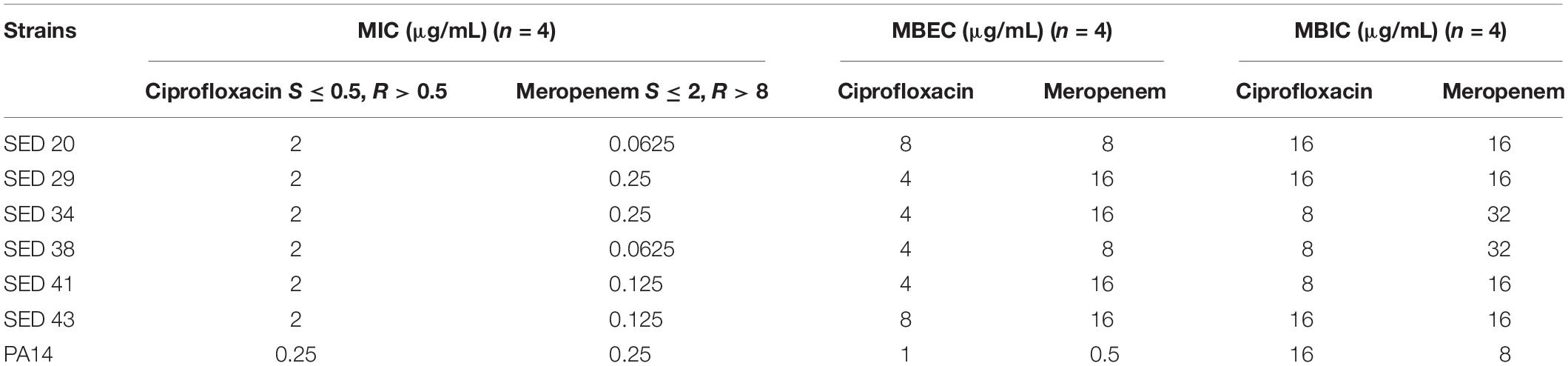

Clinical P. aeruginosa strains were resistant to ciprofloxacin (MIC 2 μg/mL) and sensitive to meropenem (MIC ≤ 0.25 μg/mL) by standard antibiotic susceptibility testing using the broth dilution method; PA14 was sensitive to both antibiotics (Table 1). Determination of MBECs for clinical isolates using the Calgary device demonstrated an increase of 2–4-fold and 64–128-fold MIC for ciprofloxacin and meropenem, respectively (Table 1). Determination of MBICs for clinical isolates demonstrated an increase of 4–8-fold and 64–512-fold MIC for ciprofloxacin and meropenem, respectively (Table 1). Additionally, the MBEC recovery plates showed no visible production of pyocyanin, pyochelin or pyoverdine (Supplementary Figure S2).

Table 1. Determination of MIC, MBEC, and MBIC of P. aeruginosa isolates against ciprofloxacin and meropenem.

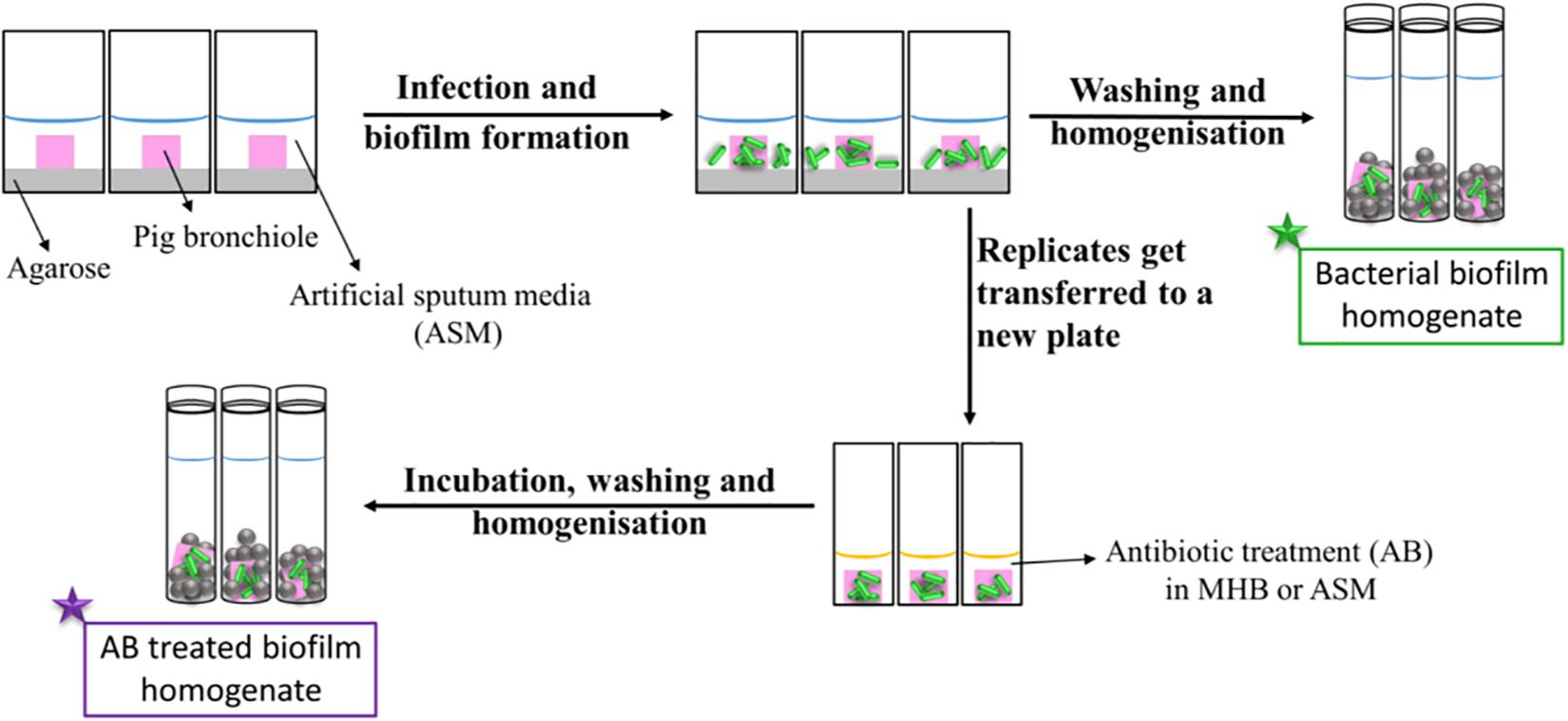

Figure 1 represents a schematic diagram of the work flow as previously described. Supplementary Figures S3, S4 show pieces of tissues infected with P. aeruginosa strains after 7 days of biofilm formation and the mucoid phenotype of the strains in the tissues, respectively, to represent chronic CF infection (Harrington et al., 2020). Our previous work with the EVPL model confirms that P. aeruginosa forms structured biofilms in this model [Alcian blue staining confirms presence of exopolysaccharide matrix, and mutant studies showed formation of structured aggregates on tissue required the gacS/gacA pathway and pel polysaccharide (Harrington et al., 2020)].

Figure 1. Schematic diagram of the work flow for the determination of the antibiotic susceptibility. Pig bronchioles were infected with P. aeruginosa clinical strains, incubated to form biofilms and homogenized for the determination of the biofilm bacterial load. Replicate infected tissues were exposed to antibiotics for 24 h before the decrease in bacterial load was determined.

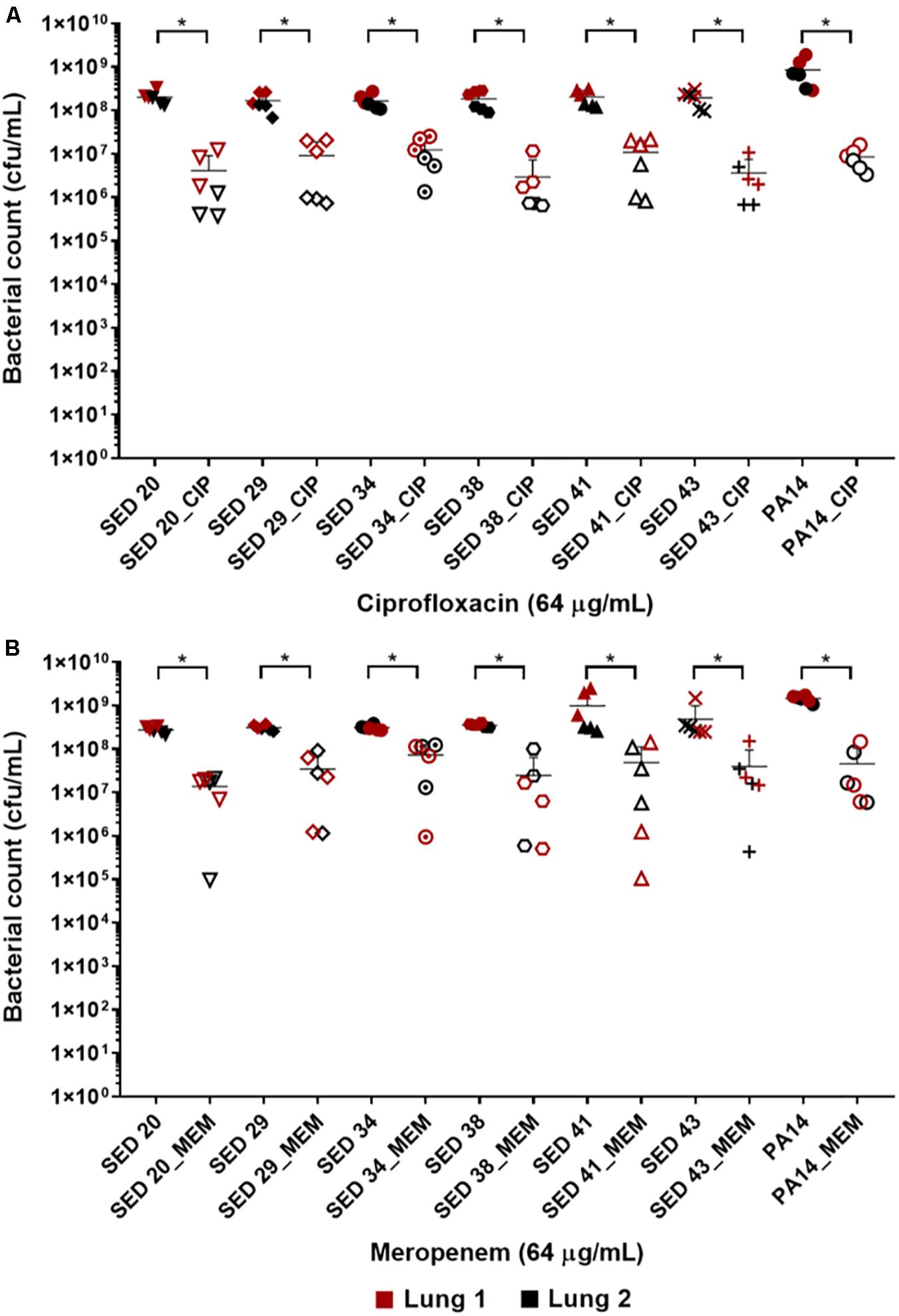

The effect of antibiotics on the bacterial load was first tested by transferring bronchiole sections containing developed biofilms to MHB (standard medium for microdilution assays) containing antibiotics. This allowed to directly compare the inhibitory effect of these antibiotics in EVPL versus in standard diagnostics assays, without the effect of the medium or any physiological differences induced by CF lung mucus. Treatment with ciprofloxacin at 32-fold MIC (8–16-fold MBEC) resulted in a 1–2 log decrease in bacterial load across all tested clinical strains (Figure 2A). However, exposure to meropenem at 256–1024-fold MIC (4–8-fold MBEC) resulted in only about 1 log decrease of the bacterial load across all strains except SED 34, which showed less than a log decrease in the bacterial count (Figure 2B). ANOVA showed a significant effect of ciprofloxacin [F(1,69) = 749.5, p < 0.001] and meropenem treatment [F(1,69) = 115.5, p < 0.001] on bacterial load, the magnitude of which was strain dependent [strain × treatment interaction F(6,69) = 3.1, p < 0.01] for ciprofloxacin but strain independent for meropenem [strain × treatment interaction F(6,69) = 0.71, p = 0.64] despite the differences in MICs and MBECs.

Figure 2. Bacterial load of P. aeruginosa in the EVPL biofilm model with and without exposure to (A) ciprofloxacin (CIP), (B) meropenem (MEM) 64 (μg/mL). The data in red and black represents two independent lungs where closed data points are for untreated bacterial strains and open data points are for antibiotic treated. Error bars are means ± SD, some error bars are too small to be visible on the graph. Unpaired t-tests were performed for the pairwise statistical analysis of treated against untreated bacterial biofilm load for each strain; significant difference (p value < 0.05) are denoted with *.

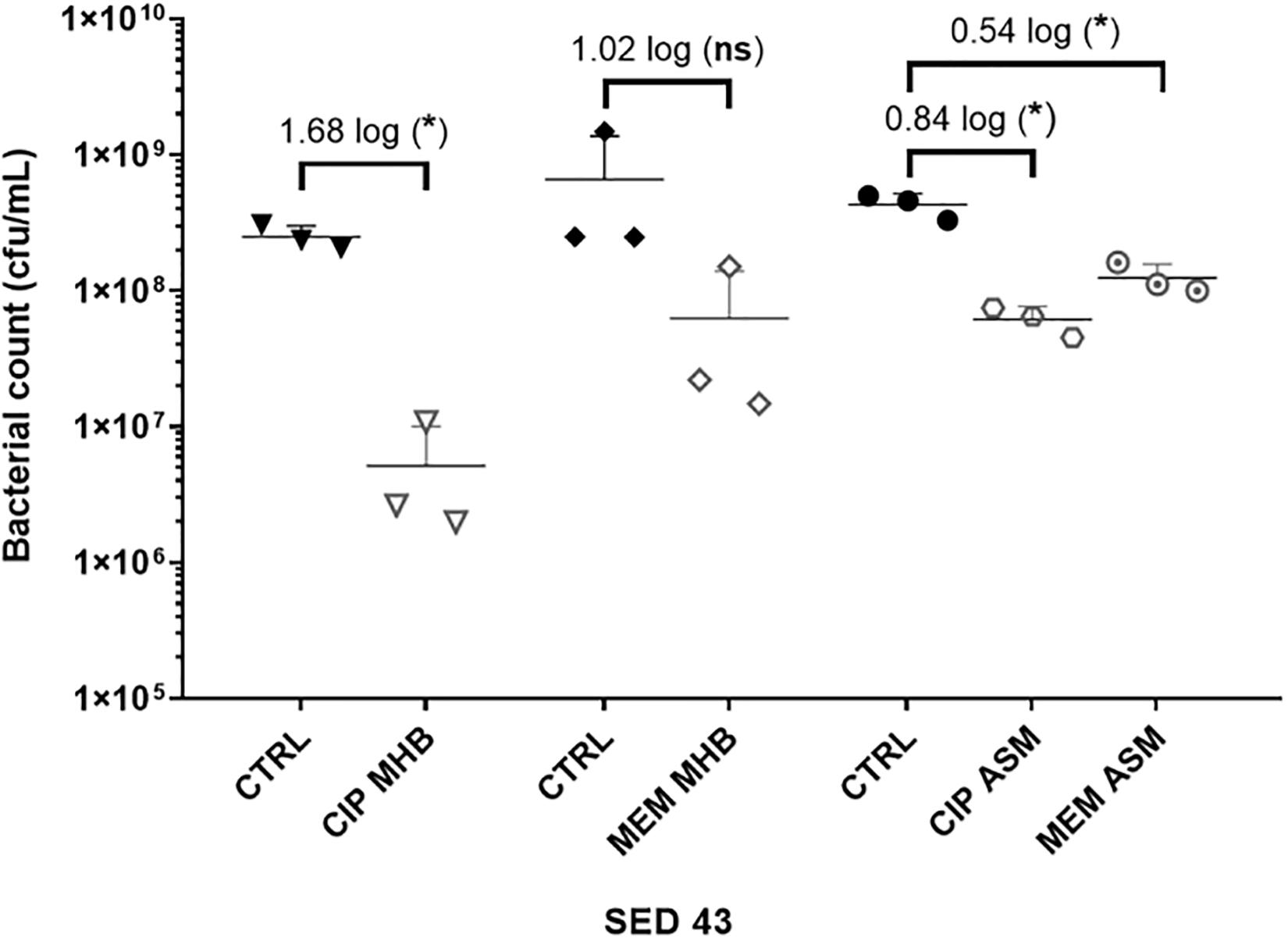

To investigate the effect of the environment on antibiotic tolerance, the bacterial load of the clinical isolate SED 43 was compared with and without ciprofloxacin or meropenem in MHB and ASM: a chemically defined medium which mimics the chemistry of chronically infected CF sputum (Palmer et al., 2007; Figure 3). As shown in Figure 3, there was a statistically significant increase in tolerance to both ciprofloxacin and meropenem treatment in ASM (0.84 and 0.54 log decrease) compared with MHB (1.68 and 1.02 log decrease). ANOVA showed significant effects of changing of medium [F(1,20) = 9.04, p < 0.01], antibiotic treatment [F(1,20) = 44.66, p < 0.001], and a medium × antibiotic interaction F(1,20) = 5.56, p < 0.05.

Figure 3. The effect of medium used (MHB or ASM) on antibiotic susceptibility of the clinical isolate SED 43 after exposure to ciprofloxacin (CIP) or meropenem (MEM) at 64 (μg/mL) in the EVPL biofilm. CTRL are controls of non-treated tissues from the same lung. Error bars are means ± SD, some error bars are too small to be visible on the graph. Unpaired t-tests were performed for the pairwise statistical analysis of treated against untreated bacterial biofilm load; significant difference (p value < 0.05) are denoted with *.

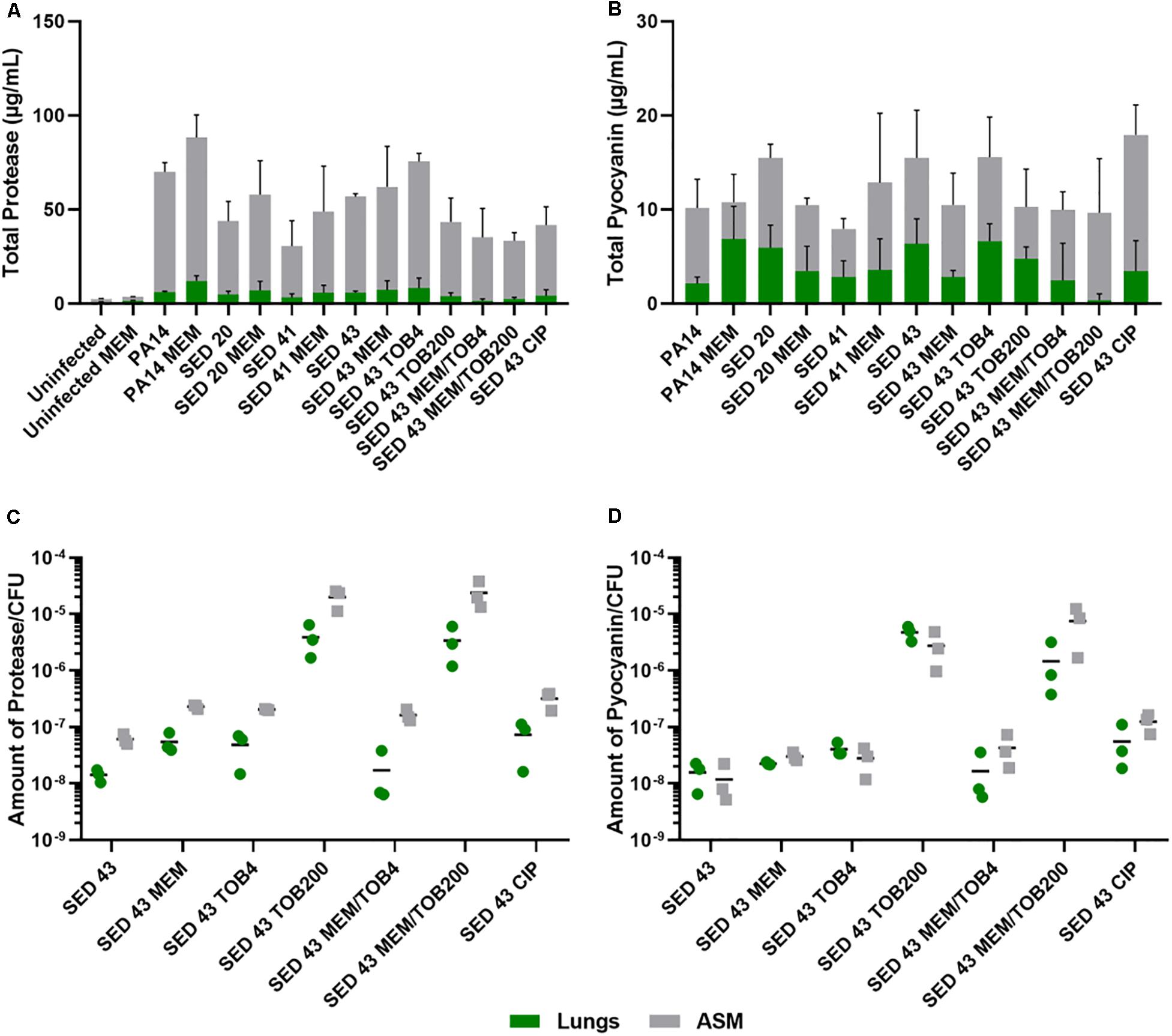

To understand the effect of antibiotics on the virulence of P. aeruginosa strains, PA14 and three clinical isolates (SED 20, SED 41, and SED 43) were assessed for the production of two readily quantifiable and well-studied virulence factors, proteases and pyocyanin in the lung tissues homogenate and surrounding ASM, separately, in the presence and absence of antibiotics. In this work, we compared our results to P. aeruginosa infected untreated tissues and all data were normalized to uninfected untreated tissues to show the effects that are due to antibiotics’ exposure. The ASM surrounding tissue sections at the end of antibiotic exposure remained visibly clear, suggesting that bacterial cells did not detach from the biofilm or grow in the surrounding ASM at appreciable rates. Total proteases and pyocyanin were shown to be mainly released from the biofilm into the ASM, with a similar pattern in the tissues (Figures 4A,B). The control strain, PA14, showed the highest protease production (63.95–76.22 μg/mL in ASM), while clinical isolates SED 20 and SED 41 showed increased total proteases from 38.87 to 50.86 and 27.24 to 43.15 μg/mL, respectively, with meropenem treatment (Figure 4A). Interestingly, pyocyanin production varied between clinical strains with meropenem treatment. SED 20 and SED 43 infected tissues demonstrated decreased production by 68% in comparison to untreated, while SED 41 showed increased pyocyanin secretion by 162% with exposure to meropenem (Figure 4B and Supplementary Tables S1, S2). Surprisingly, ciprofloxacin treatment also showed a significantly higher pyocyanin by 116% (Figure 4B and Supplementary Table S2). Proteases and pyocyanin concentrations in tissue and surrounding ASM, and total fold increases associated with antibiotic treatments are summarized in Supplementary Tables S1, S2, respectively.

Figure 4. Using the EVPL model for understanding bacterial virulence with and without antibiotics in comparison to control lab strains. (A) Total protease, (B) Total pyocyanin, (C) The amount of protease/CFU, (D) The amount of pyocyanin/CFU. CIP (ciprofloxacin), MEM (meropenem) at 64 μg/mL, TOB4 and TOB200 (tobramycin at 4 and 200 μg/mL, respectively). Error bars are means ± SD, some error bars are too small to be visible on the graph.

ANOVA showed a significant effect of strain [F(4,20) = 6.798, p < 0.01] and meropenem treatment [F(1,20) = 6.519, p < 0.05] on proteases production in the tissues, and the effect of meropenem did not differ between strains [strain × treatment interaction F(4,20) = 0.825, p = 0.52]. In the surrounding ASM, similar effects were observed with strain [F(4,20) = 20.92, p < 0.001] and meropenem treatment [F(1,20) = 3.193, p < 0.1]. Total pyocyanin produced in the tissues and ASM was also significantly different between strains [F(4,20) = 5.03, p < 0.01 and F(4,20) = 6.40, p < 0.01, respectively], and the effect of meropenem significantly differed between strains [strain × treatment interaction F(4,20) = 3.31, p < 0.05].

To further assess the potential effects on virulence of different clinically relevant antibiotics, we exposed EVPL biofilms of strain SED 43 to ciprofloxacin, tobramycin and a combination of meropenem and tobramycin, in ASM. Isolates are resistant to tobramycin (Darch et al., 2015). Interestingly, SED 43 showed a greater total production of proteases, in ASM, compared with the other clinical isolates (50.91 μg/mL), and slightly increased total proteases with meropenem (54.85 μg/mL, 109%) and tobramycin at low concentration (67.24 μg/mL, 133%). Both treatments led to comparable decreases in bacterial load (Supplementary Figure S5). The increased bacterial death with ciprofloxacin and tobramycin, at high concentration, (Supplementary Figure S5) correlated with decreased total proteases of 37.55 μg/mL (74%) and 39.7 μg/mL (77%), respectively. Combination treatment of tobramycin at 4 or 200 μg/mL with meropenem (64 μg/mL) showed a total protease of 33.83 (62%) and 31.07 μg/mL (59%) (Figure 4A and Supplementary Table S2), respectively.

As the total concentrations of proteases and pyocyanin discussed above are a function of both altered cellular production levels and altered cell numbers, we then normalized total proteases and pyocyanin concentrations by bacterial counts, to determine how antibiotic exposure affected per-cell production. The amount of proteases/cfu and pyocyanin/cfu measured in the tissues were slightly lower or equal to that of the surrounding ASM, respectively (Figures 4C,D). Exposure to meropenem (64 μg/mL), ciprofloxacin (64 μg/mL), and tobramycin (4 μg/mL) slightly increased the production of proteases and pyocyanin by bacterial cfu, while a significant increase was found with tobramycin (200 μg/mL) and a combination of meropenem/tobramycin (64/200 μg/mL) (Figures 4C,D). The latter treatments have a greater effect on bacterial load (Supplementary Figure S5). The total amount of tissue and ASM proteases/cfu and pyocyanin/cfu is shown in Supplementary Figure S6.

ANOVA analysis showed a significant effect of antibiotic treatment on the amount of protease/cfu [tissue F(6,13) = 11.27, p < 0.001] and [surrounding ASM F(6,13) = 37.09, p < 0.001], and production of pyocyanin [tissue F(6,13) = 25.61, p < 0.001] and [surrounding ASM F(6,13) = 17.88, p < 0.001].

In CF, chronic P. aeruginosa infections are characterized by the mucoid phenotype, which can adversely affect the individuals’ pulmonary function increasing mortality rates. Therefore, oral and nebulized ciprofloxacin and colistin, respectively, are administered at early infection stages to reduce the risk of chronic infection and during chronic infections to eradicate P. aeruginosa (Trust, 2009). Un-cleared infections and moderate to severe exacerbation cases are treated with intravenous anti-pseudomonal antibiotics such as ceftazidime, meropenem and tobramycin in combination with β-lactams (Trust, 2009). Pharmacokinetic characterization of oral ciprofloxacin administration in CF has shown a Cmax of 2.3 μg/mL in sputum (Reed et al., 1988). The administration of a single intravenous dose of meropenem (1 gm) has been shown to achieve a bronchial secretion concentration of 0.53 μg/mL (Bergogne-Berezin et al., 1994). Intravenous tobramycin has been shown to lead to a sputum concentration of 68 μg/mL and to show a bactericidal effect at a sputum concentrations of 25x-MIC (Mendelman et al., 1985).

In this study, we compared the antibiotic susceptibility of selected P. aeruginosa strains using current diagnostic methods and our previously developed EVPL biofilm model. The increase in bacterial resistance profile with the 1 day biofilm Calgary device in comparison to standard MIC had been previously reported (Macia et al., 2014). However, the Calgary device still does not represent in vivo biofilms. Exposure to ciprofloxacin and meropenem at concentrations higher than MBEC values and reported sputum concentrations led to a decrease of bacterial load by only 1–2 logs (Figure 2), which may be attributed to the formation of denser or mature biofilm in the EVPL model (Harrington et al., 2020). The failure to eradicate P. aeruginosa biofilms in the EVPL model, with such high concentrations, may be closer to the in vivo effect of these antibiotic treatments, demonstrating the need to employ CF representative diagnostics to better reflect on the antibiotics’ inhibitory effect.

Antibiotic tolerance was also affected by the use of different media. Besides the difference in planktonic and biofilm based models, Kirchner et al. (2012) demonstrated increased biofilm inhibitory concentrations, for most tested P. aeruginosa strains, when assessed in ASM compared with planktonic-based MIC in LB medium. Davies et al. (2017) also showed the increase in bacterial heterogeneity, population diversity and antibiotic resistance of P. aeruginosa in ASM. Therefore, we believe it is a more accurate model to show the effect of antibiotic treatment in CF is by testing for antibiotic susceptibility in ASM rather than general laboratory medium. This was alarmingly poorer than in MHB (Figure 3). As we have now demonstrated the tractability of performing antibiotic susceptibility testing in the ex vivo lung model using a small set of isolates. Future work can usefully assess the antibiotic sensitivity profiles of biofilms of a much wider range of isolates in this model and develop this model to a high throughput method that can be easily translated into the clinic taking advantage of its low cost.

The work also indicated the potential in vivo effect of exposure to different antibiotics, in ASM, on the virulence of P. aeruginosa to understand the clinical implications of chosen antibiotics. We focused on two main virulence factors of P. aeruginosa: proteases and pyocyanin production. Production of proteases is triggered by the quorum sensing system to degrade vital host proteins and antibodies. In CF lungs, proteases have been shown to cause a severe inflammatory response leading to pulmonary damage (Das and Manos, 2017), and were detected in sputum during exacerbation (Jaffar-Bandjee et al., 1995). Pyocyanin is also regulated by the quorum sensing system. It is a redox molecule that generates reactive oxygen species to induce oxidative stress in host cells, leading to cell damage and lysis. This quorum sensing system is activated by the action of antibiotics as a mechanism to persist and survive and is cell density dependent (Singh et al., 2000; Hassan et al., 2018). P. aeruginosa is protected from these reactive oxygen species by its own catalases (Das and Manos, 2017). Previous studies had estimated the concentration of pyocyanin in sputum of as high as 16.5 μg/mL (Wilson et al., 1988), similar to the detected values in Figure 4B. The antibiotic recovery plates of P. aeruginosa following Calgary biofilm susceptibility testing did not show any production of pyochelin, pyoverdine or pyocyanin (Supplementary Figure S2), but following exposure to antibiotics in the EVPL model, bacterial expression of proteases and pyocyanin was increased (Figure 4). The increase of protease/cfu and pyocyanin/cfu with combination therapy (being normalized for the cell density) was also alarming. This highlights the aggressiveness of P. aeruginosa infection in CF and shows the effect different antibiotic treatments supporting the need for anti-virulence drugs.

Bacteria causing biofilm infections are often assessed for their antibiotic resistance profile using standard planktonic MIC methods or simple biofilm platforms such as the Calgary device. These do not represent the environment bacteria inhabit in vivo, giving misleading results. The current gap in clinical outcomes and standard susceptibility testing results is a very clear evidence. Our results, taken from an ex vivo animal tissue model using host-mimicking growth medium are consistent with increased antibiotic tolerance in in vivo biofilms. It is possible that current antibiotic prescribing could not only fail to eradicate biofilm load, but also worsen lung conditions by increasing expression of virulence factors by surviving bacteria, which requires immediate action to help eradicate biofilm infections. Thus, further work with clinical samples will be required to determine the effect of antibiotic treatment on bacterial load, lung function, and possibly exacerbations. It is also important to assess the role of mucoidy and alginate production with antibiotic treatments.

This manuscript has been released as a pre-print at bioRxiv (Hassan et al., 2020).

Raw data will be made available by corresponding author without undue reservation.

Ethical review and approval was not required for this work because all pig lungs were post-consumer waste from a commercial abattoir.

MH and FH contributed to the concept of the study. MH designed, performed, and analyzed experiments as well as wrote the manuscript. NH helped in designing and performing some of the virulence assay experiments. ES performed pilot work. All authors revised and approved the manuscript.

This work was funded by a Medical Research Council New Investigator Research Grant to FH (MR/R001898/1). NH was funded by a Ph.D. studentship from the BBSRC Midlands Integrative Biosciences Training Partnership (MIBTP).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

We thank Prof. Sophie Darch and Prof. Steve Diggle for CF isolates of P. aeruginosa and Prof. Leo Eberl for P. aeruginosa PA14. We would also like to acknowledge Cerith Harries and Caroline Stewart for the use of the media preparation facilities within the School of Life Sciences, University of Warwick.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2020.568510/full#supplementary-material

Bergogne-Berezin, E., Muller-Serieys, C., Aubier, M., and Dombret, M. C. (1994). Concentration of meropenem in serum and in bronchial secretions in patients undergoing fibreoptic bronchoscopy. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 46, 87–88.

Bjarnsholt, T., Alhede, M., Alhede, M., Eickhardt-Sorensen, S. R., Moser, C., Kuhl, M., et al. (2013). The in vivo biofilm. Trends Microbiol. 21, 466–474.

Breidenstein, E. B. M., De La Fuente-Núñez, C., and Hancock, R. E. W. (2011). Pseudomonas aeruginosa: all roads lead to resistance. Trends Microbiol. 19, 419–426. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2011.04.005

Darch, S. E., Mcnally, A., Harrison, F., Corander, J., Barr, H. L., Paszkiewicz, K., et al. (2015). Recombination is a key driver of genomic and phenotypic diversity in a Pseudomonas aeruginosa population during cystic fibrosis infection. Sci. Rep. 5:7649.

Das, T., and Manos, J. (2017). “Pseudomonas aeruginosa extracellular secreted molecules have a dominant role,” in Biofilm Development and Bacterial Virulence in Cystic Fibrosis Lung Infections, ed. D. Sriramulu (London: IntechOpen), 101.

Davies, E. V., James, C. E., Brockhurst, M. A., and Winstanley, C. (2017). Evolutionary diversification of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in an artificial sputum model. BMC Microbiol. 17:3. doi: 10.1186/s12866-016-0916-z

Davies, J. C. (2002). Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis: pathogenesis and persistence. Paediatr. Respir. Rev. 3, 128–134. doi: 10.1016/s1526-0550(02)00003-3

Essar, D. W., Eberly, L., Hadero, A., and Crawford, I. (1990). Identification and characterization of genes for a second anthranilate synthase in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: interchangeability of the two anthranilate synthases and evolutionary implications. Microbiology 172, 884–900. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.2.884-900.1990

EUCAST (2019). The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Breakpoint Tables for Interpretation of MICs and Zone Diameters. Version 9.0. Available online at: http://www.eucast.org (accessed March 1, 2019).

Harrington, N. E., Sweeney, E., and Harrison, F. (2020). Building a better biofilm - formation of in vivo-like biofilm structures by Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a porcine model of cystic fibrosis lung infection. Biofilm 2:100024. doi: 10.1016/j.bioflm.2020.100024

Harrison, F., and Diggle, S. P. (2016). An ex vivo lung model to study bronchioles infected with Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Microbiology 162, 1755–1760. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.000352

Harrison, F., Muruli, A., Higgins, S., and Diggle, S. P. (2014). Development of an ex vivo porcine lung model for studying growth, virulence, and signaling of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect. Immun. 82, 3312–3323. doi: 10.1128/iai.01554-14

Hassan, M. M., Butler, M. S., Ranzoni, A., and Cooper, M. A. (2018). Detection and quantification of the heterogeneity of S. aureus bacterial populations to identify antibiotic-induced persistence. bioRxiv [Preprint], doi: 10.1101/320093

Hassan, M. M., Harrington, N. E., Sweeney, E., and Harrison, F. (2020). Predicting antibiotic-associated virulence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa using an ex-vivo lung biofilm model. bioRxiv [Preprint], doi: 10.1101/2020.02.24.963173

Hoiby, N., Ciofu, O., and Bjarnsholt, T. (2010). Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms in cystic fibrosis. Future Microbiol. 5, 1663–1674.

Jaffar-Bandjee, M. C., Lazdunski, A., Bally, M., Carrere, J., Chazalette, J. P., and Galabert, C. (1995). Production of elastase, exotoxin A, and alkaline protease in sputa during pulmonary exacerbation of cystic fibrosis in patients chronically infected by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33, 924–929. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.4.924-929.1995

Kirchner, S., Fothergill, J. L., Wright, E. A., James, C. E., Mowat, E., and Winstanley, C. (2012). Use of artificial sputum medium to test antibiotic efficacy against Pseudomonas aeruginosa in conditions more relevant to the cystic fibrosis lung. J. Vis. Exp. 2012:e3857.

Lyczak, J. B., Cannon, C. L., and Pier, G. B. (2002). Lung infections associated with cystic fibrosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 15, 194–222.

Macia, M. D., Rojo-Molinero, E., and Oliver, A. (2014). Antimicrobial susceptibility testing in biofilm-growing bacteria. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 20, 981–990. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12651

Mendelman, P. M., Smith, A. L., Levy, J., Weber, A., Ramsey, B., and Davis, R. L. (1985). Aminoglycoside penetration, inactivation, and efficacy in cystic fibrosis sputum. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 132, 761–765.

Moskowitz, S. M., Foster, J. M., Emerson, J., and Burns, J. L. (2004). Clinically feasible biofilm susceptibility assay for isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa from patients with cystic fibrosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42, 1915–1922. doi: 10.1128/jcm.42.5.1915-1922.2004

Musken, M., Klimmek, K., Sauer-Heilborn, A., Donnert, M., Sedlacek, L., Suerbaum, S., et al. (2017). Towards individualized diagnostics of biofilm-associated infections: a case study. NPJ Biofilms Microb. 3:22.

Palmer, K. L., Aye, L. M., and Whiteley, M. (2007). Nutritional cues control Pseudomonas aeruginosa multicellular behavior in cystic fibrosis sputum. J. Bacteriol. 189, 8079–8087. doi: 10.1128/jb.01138-07

Reed, M. D., Stern, R. C., Myers, C. M., Yamashita, T. S., and Blumer, J. L. (1988). Lack of unique ciprofloxacin pharmacokinetic characteristics in patients with cystic fibrosis. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 28, 691–699. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1988.tb03202.x

Saha, S., Thavasi, R., and Jayalakshmi, S. (2008). Phenazine pigments from Pseudomonas aeruginosa and their application as antibacterial agent and food colourants. Cell 3, 122–128. doi: 10.3923/jm.2008.122.128

Singh, P. K., Schaefer, A. L., Parsek, M. R., Moninger, T. O., Welsh, M. J., and Greenberg, E. P. (2000). Quorum-sensing signals indicate that cystic fibrosis lungs are infected with bacterial biofilms. Nature 407, 762–764. doi: 10.1038/35037627

Taylor, P. K., Yeung, A. T. Y., and Hancock, R. E. W. (2014). Antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms: towards the development of novel anti-biofilm therapies. J. Biotechnol. 191, 121–130. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2014.09.003

Trust, U. C. (2009). Antibiotic Treatment for Cystic Fibrosis, 3rd Edn, London: Cystic Fibrosis Trust Antibiotic Working Group.

Wilson, R., Sykes, D. A., Watson, D., Rutman, A., Taylor, G. W., and Cole, P. J. (1988). Measurement of Pseudomonas aeruginosa phenazine pigments in sputum and assessment of their contribution to sputum sol toxicity for respiratory epithelium. Infect. Immun. 56, 2515–2517. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.9.2515-2517.1988

Keywords: antibiotic susceptibility testing, antimicrobial resistance, bacterial biofilm, cystic fibrosis, antibiotic tolerance

Citation: Hassan MM, Harrington NE, Sweeney E and Harrison F (2020) Predicting Antibiotic-Associated Virulence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Using an ex vivo Lung Biofilm Model. Front. Microbiol. 11:568510. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.568510

Received: 01 June 2020; Accepted: 17 August 2020;

Published: 02 September 2020.

Edited by:

Yuji Morita, Meiji Pharmaceutical University, JapanReviewed by:

Sheyda Azimi, Georgia Institute of Technology, United StatesCopyright © 2020 Hassan, Harrington, Sweeney and Harrison. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Marwa M. Hassan, bS5odXNzYWluYWxpaGFzc2FuQHN1cnJleS5hYy51aw==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.