- 1Department of Environmental Science and Engineering, Xi'an Jiaotong University, Shaanxi, China

- 2Department of Structures and Environmental Engineering, University of Agriculture, Faisalabad, Pakistan

Developments in industrial applications inevitably accelerate the discharge of enormous substances into the environment, whereas multi-component mixtures commonly cause joint toxicity which is distinct from the simple sum of independent effect. Thus, ecotoxicological assessment, by luminescent bioassays has recently brought increasing attention to overcome the environmental risks. Based on the above viewpoint, this review included a brief introduction to the occurrence and characteristics of toxic bioassay based on the luminescent bacteria. In order to assess the environmental risk of mixtures, a series of models for the prediction of the joint effect of multi-component mixtures have been summarized and discussed in-depth. Among them, Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) method which was widely applied in silico has been described in detail. Furthermore, the reported potential mechanisms of joint toxicity on the luminescent bacteria were also overviewed, including the Trojan-horse type mechanism, funnel hypothesis, and fishing hypothesis. The future perspectives toward the development and application of toxicity assessment based on luminescent bacteria were proposed.

Introduction

With the intensive industrial emissions and human activities, natural compounds and anthropogenic pollutants discharged into the environment accumulate in ecosystems, which contributed a lot to the environmental pollution. The toxicity of the pollutants, especially multi-component mixtures in a single sample are of more considerable concern due to their potential negative impact on human and other living organisms, such as modifying the stability of genetic information and inhibition of growth. The multi-component contaminants may have an adverse effect on organism even the concentration of single pollutant is less than No Observable Effect Concentration (NOEC) (Hageman et al., 2019). Furthermore, when two or more component mixtures act on a living organism simultaneously, the joint toxicity may significantly differ from the single-substance toxicity.

The sustained attention on the toxic effects of pollutants in the environment has brought forth the rapid development of sensitive and controllable monitoring techniques. In comparison with the physical and chemical analysis, that could only determine the compositions and concentration of the pollutants in the environmental samples, the biological assay could intuitively reflect the detrimental effects of contaminants toward target organisms which is of great importance and contribute to revealing the mechanisms of the toxic effects (Li et al., 2013a,b). Among various bioassay types, acute toxicity bioassays have been rapidly developing as a preferred tool for environmental risk assessment in recent decades which can detect the adverse effects of a single component or multi-component mixtures in a short period and determine the relationship between dose and effect of toxic substances. Acute toxicity bioassays generally can be conducted with both prokaryote and eukaryote, containing bacteria (Ma et al., 2018; Rao et al., 2019; Feng et al., 2020), algae (Costa et al., 2018; Staveley et al., 2018), invertebrates (Chen et al., 2020; Sackey et al., 2020; Vilela et al., 2020), vertebrates (Clemow and Wilkie, 2015; Thornton et al., 2017; Barron et al., 2018; Ivey et al., 2019), and so on. Inevitably, the application of multicellular organisms exhibits the undesirable limitations of relatively longer operation time and higher cost. Therefore, microbial bioassays, especially with luminescent bacteria increased widely interests in the acute toxicity bioassays due to its operational simplicity, less time and cost consuming, higher sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility (Conforti et al., 2008; Skotti et al., 2014; Yang et al., 2016).

With the growing number of disparate predictions available to perform multi-component mixtures biotoxicity analyses with luminescent bacteria, the choice of methods presents a major challenge to researchers as there is no review of comparative methods currently available. In this review, we summarize the occurrence of bioluminescent assays and the prevalence of determination of joint toxicity of multi-component mixtures and describes the various types of models involved in joint toxicity prediction. The representative methods for the prediction and evaluation of acute joint toxicity are overviewed including graphical method, joint effect indexes, and integrative models. Furthermore, the QSAR method as a hotspot in joint toxicity researches, are also presented in detail.

The Physiological Mechanism and Development of Toxic Bioassay by Luminescent Bacteria

Currently, luminescent bacteria have been applied worldwide in the bioassays of toxicity assessment, including Aliivibrio fisheri (A. fischeri, previously identified as Vibrio fisheri or Photobacterium fisheri), Photobacterium phosphoreum, Vibrio qinghaiensis, Vibrio harveyi and so on (Urbanczyk et al., 2007). Luminescent bacteria that could emit visible bioluminescence under certain physiological conditions were primarily isolated from the ocean environment except for V. cholerea and V. qinghaiensis sp. Nov (Zhu et al., 1994; Ma et al., 2014).

Physiological Mechanism of Bioluminescence From Luminescent Bacteria

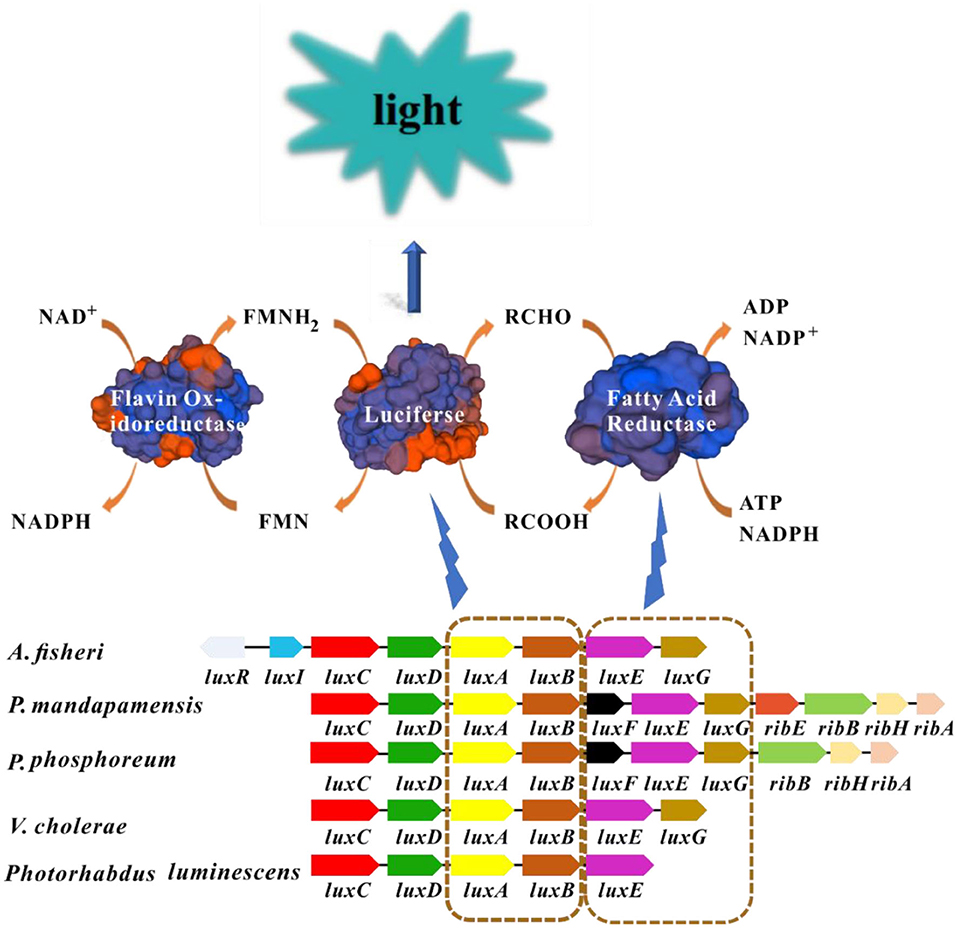

The bioluminescence mechanism of luminescent bacteria has been fully studied and characterized (Inouye, 1994; Moore and James, 1995; Bourgois et al., 2001; Vetrova et al., 2007; Nijvipakul et al., 2010; Bergner et al., 2015; Brodl et al., 2018; Tanet et al., 2019). Generally, luciferase, reduced flavin mononucleotide (FMNH2), oxygen (O2), and long-chain fatty aldehyde (RCHO) are prerequisite for the luminescence emitted by luminescent bacteria in which flavin mononucleotide (FMN) was reduced to FMNH2 by the catalyzation of NAD(P)H: FMN oxidoreductase. Then FMNH2 and molecular oxygen will bind with luciferase which has flavin reductase activity to form the intermediate. Subsequently, the intermediate will decompose in the presence of aldehyde, FMNH2 are oxidized into FMN and H2O by the catalyzation of luciferase enzyme, along with the emitting of continuous blue-green light (490 nm) (Figure 1) (Inouye, 1994).

Figure 1. Luminescence mechanism of luminescent bacteria. Blocks with the same color in different bacteria represent homologous genes. The luxA and luxB encode luciferase, luxC, luxD, and luxE encode the fatty acid reductase complex. The structures of enzymes in this picture are modeled by SWISS-MODEL (https://www.swissmodel.expasy.org/). FMNH2 and long-chain fatty aldehyde are oxidized by luciferase enzyme into FMN and long chain fatty acid, respectively. This process is accompanied by the production of blue-green light.

The enzyme involved in bioluminescence in luminescent bacteria is commonly encoded by lux genes which are usually clustered together as lux operon (luxCDABE) (Matheson and Lee, 1981). Luciferase possesses α and β subunits, that are encoded by luxA and luxB genes, respectively. Moreover, the α subunit which exhibits major catalytic activity is similar to the β subunit in amino acid sequence (around 30%) (Sharifian et al., 2017). In general, the organization of lux genes and the amino acid sequences from different luminescent bacteria are similar which indicates their origin from common ancestor and conservation in evolution. Fatty acid reductase complex is encoded by luxC, luxD, and luxE, which is responsible for the transformation between long-chain fatty acids and fatty aldehydes (Figure 1). In certain luminescent bacteria such as Aliivibrio species, the presence of regulatory genes luxI and luxR are detected which link bioluminescence with quorum sensing (QS) (Miyashiro and Ruby, 2012). The gene luxI encodes the enzyme required for the synthesis of the autoinducer molecule, and LuxR is the autoinducer-dependent transcription factor, the binding of autoinducer-LuxR to the promoter will initiate the transcription of lux operon (Engebrecht and Silverman, 1984; Fuqua et al., 1994). Some additional lux genes including luxG, luxF and luxH have also been found in some luminescent lux operons, but there is no evidence to confirm that these genes were directly related to bioluminescence (O'Grady and Wimpee, 2008; Bergner et al., 2015; Deeva et al., 2019).

Development Application of Toxicity Assessment by Luminescent Bacteria

The toxicity bioassay with luminescent bacteria has been successfully employed in the comprehensive ecotoxicity assessments. In 1978, Beckman Company of the United States first commercialized the toxic bioassay as “Microtox®” with A. fischeri, the sensitivity of which was comparable to the 96 h acute toxicity test of fish (Flokstra et al., 2008). Since then, the toxicity assessment by luminescent bacteria has been developing rapidly toward higher sensitivity, accuracy, reproducibility, anti-interference, and extensive application. As a comprehensive indicator, luminescent bacteria have been successfully applied for monitoring the ecotoxicity of the natural environment, including wastewater, river water, sewage sludge, landfill leachate, and so on (Jarque et al., 2016; Pino-Otín et al., 2019). Zhang et al., examined the toxicity of surface water from the Huangpu River of China by V. qinghaiensis sp.-Q67, and found the seasonal variation of toxicity (Zhang et al., 2015). Likewise, Jarque et al. held the view that V. fishieri luminescence assay to evaluate the toxicity associated with sediments from the Morava River and its tributary Drevnice River followed seasonal patterns (Jarque et al., 2016). Luminescent bacteria toxicity bioassay could also be carried out to evaluate the ecological risk of wastewater before and after diverse treatment processes, including ozonation, Fenton, UV, electrochemical degradation, biological process, and so on (De Schepper et al., 2012; Hamdi El Najjar et al., 2014; Lütke Eversloh et al., 2014; Wei et al., 2015; Nebout et al., 2016; Xu et al., 2018).

No confined to aqueous bodies, luminescent bacteria bioassay are also conducted in another environmental medium. Aammi et al. evaluated the acute toxicity and genotoxicity levels of atmospheric particulate matter (PM) samples from three districts in Istanbul, Turkey. V.fischeri was used to test the biotoxicity of the collected ambient air samples. The study identified significant locational and seasonal differences in the toxicity level of PM2.5−10 extracts. In terms of seasonal differences, more toxic and anthropogenic particle samples present in winter. Most of the toxic PM samples were identified in central urban, it can be attributed mainly to the inner-city and transit traffic emissions (Aammi et al., 2017). Moreover, Microtox® system along with V.fischeri has also been applied to determine the ecotoxicity of PM emitted from three different light-duty vehicles, the results demonstrated that PM from both gasoline and diesel vehicle equipped with the silicon-carbide catalyzed diesel particle filter (CDPF) appeared higher toxicity on a per mass basis than the corresponding vehicle with conventional exhaust, which indicated the decrease of PM emission level was not equated to the reduction of toxicity (Vouitsis et al., 2009). To reveal the influence factors on the formation of environmental persistent free radicals (EPFRs) in soil and the associated biotoxicity, Zhang et al. mimicked the formation of the EPFRs in the catechol-contaminated soil, they concluded that significantly inhibited the bioluminescence of P. phosphoreum when the concentration of EPFRs reached the maximum at pyrolysis temperature of 300. It could be speculated that the production of ·OH or reactive oxygen species (ROS) may be the dominant contributor to its acute toxicity to luminescent bacteria (Zhang et al., 2019b).

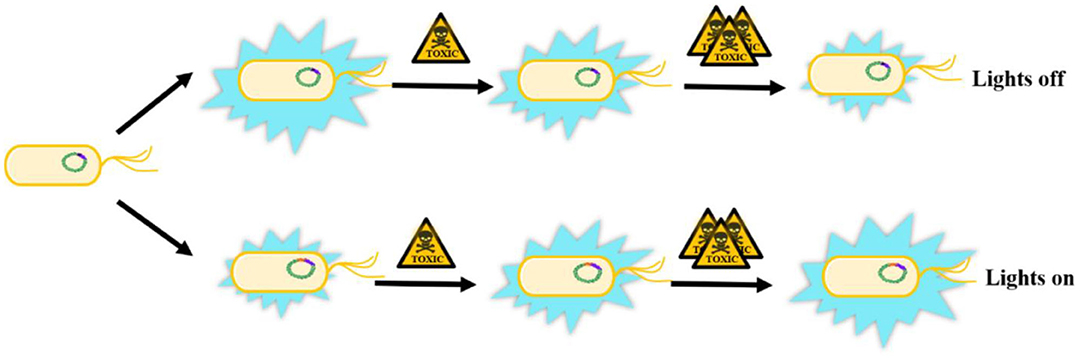

The conventional biotoxicity evaluation methods based on luminescent bacteria suffered from only being able to detect the overall toxicity without selectivity. A great deal of previous research has focused on specific toxins toxicity evaluation of target substances to overcome the drawback. Surveys such as that conducted by Huang et al. (2019a) have shown that dual detection by a combination of luminescent bacteria and aggregation aggregation-induced emission (AIE) probe could detect bioaccumulated Hg2+. The toxic effect of Hg2+ on P. phosphoreum give rise to quenching its bioluminescence inside the bacteria. Moreover, the AIE-active probe 2-AFN-I entered the damaged bacteria and selectively bound to Hg2+, which would turn-on the fluorescence and complete the overall dual detection (Huang et al., 2019a). What's more, microbial biosensors as one of the most significant applications of luminescent bacteria has been developing gradually with the incomparable advantages of selective identification and quantification of specific substances directly in air and water. Microbial biosensors are usually composed of immobilized microorganisms (recognition element) in the transducer to produce a measurable signal such as current, potential, or optical a signal, which can be further amplified and analyzed. Since 1997, Boyd and Mowat confirmed the change of luminescence emitted by living microorganisms in the presence of a target analyte (Boyd et al., 1997), bioluminescence genes (lux) have been recognized as an effective and preferable reporter system of biosensors for toxicity evaluation. The luxCDABE genes have been transferred into specific bioreporter bacteria under the control of a particular promoter to integrate into the recognition element of a biosensor. These recombinant luminescent bacteria can be divided into two categories according to expression pattern (Figure 2). If the lux genes are transferred into the constitutive expression system, the luminescence will be emitted continuously and decrease with the increasing quantity of toxic substances (“lights off”), which is non-specific and suitable for the total toxicity assessment of the mixture. Most natural bioluminescent bacteria belong to this group (Belkin, 2003; Gu et al., 2004). In the other group, lux genes are fused with inducible promoters which can be activated under the exposure of specific chemicals. Therefore, the produced luminescence will increase with the increasing amount of specific toxic chemicals (“lights on”). Most of the microbial biosensors based on luminescent bacteria could be classified as this specific group (Belkin, 2003). Nowadays, biosensors are rapidly developing toward higher sensitivity, specificity, reproducibility, automation and high throughput (Conforti et al., 2008; Skotti et al., 2014; Yang et al., 2016). Furthermore, some specific biosensors with recombinant bioluminescent bacteria have also been designed to detect cell damage, like DNA damage, protein damage, cell membrane damage and stress response (Ahn et al., 2009; Sazykin et al., 2016; Jiang et al., 2017).

Figure 2. The biosensor patterns in toxicity assessment based on recombinant luminescent bacteria. Lights off: the luminescence will be emitted continuously and decrease with the increasing quantity of toxic substances. Lights on: lux genes are fused with inducible promoters which could be transcribed and expressed under the expose of specific chemicals and the luminescence will increase with the increasing quantity of specific toxic chemicals. Chromosome, lux genes and promoters are presented with green, purple and orange color respectively.

Evaluation and Prediction of Joint Toxicity of Mixed Substances

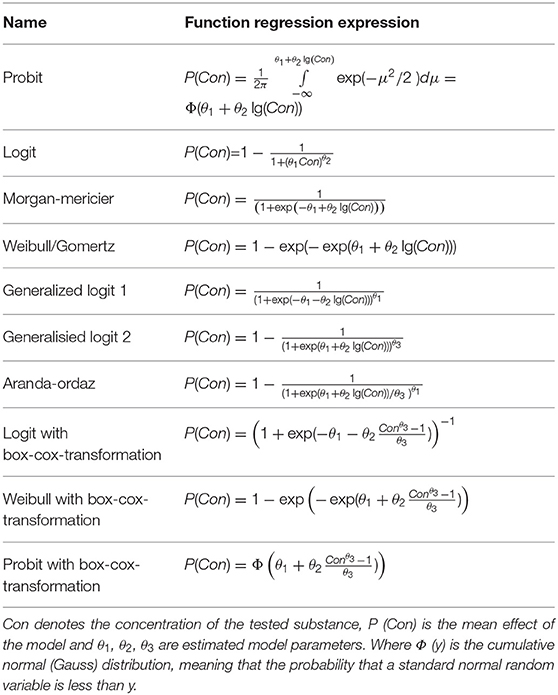

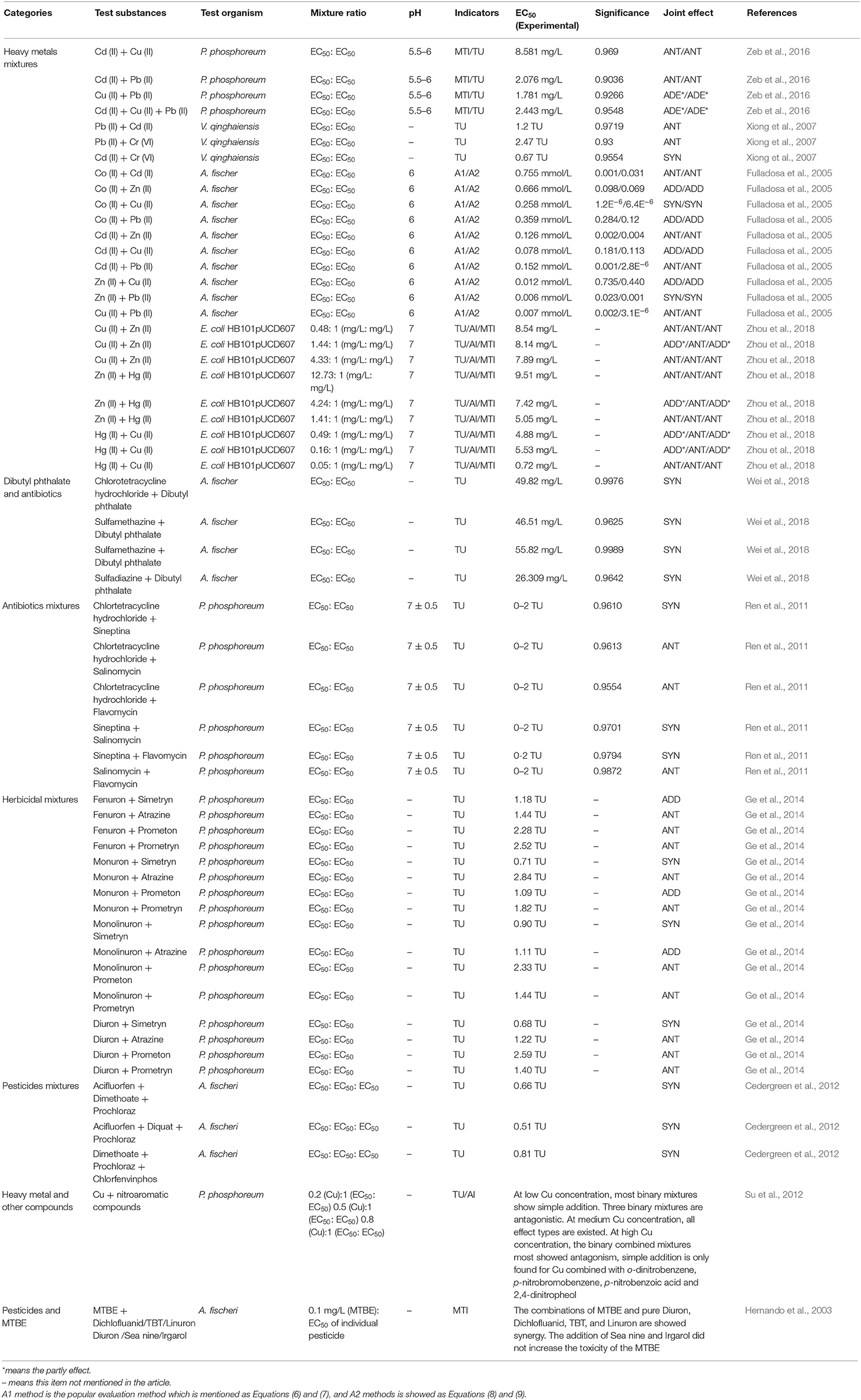

The multi-component mixtures could cause combined toxicity which is distinct from independent effect, due to the apparent differences between the toxic mode of actions (TMOA) and the interactions among constituents. Even if the characteristics of each component are acquainted, the integrative effect of the mixture could not be directly inferred. Therefore, the evaluation and prediction of the joint effect of mixed contaminants have been attracting increasing interests. In the research field of environmental toxicology, the most reported studies on joint toxicity focused on the evaluation of the combined effects of components in the mixed system (Monosson, 2005). According to the different interaction modes of the constituents in a mixture, combined toxicity can be categorized into diverse effects, including antagonism (ANT), additive (ADD), independent (IND), and synergistic (SYN) effects (Plackett and Hewlett, 1952). With the development of toxicology and mathematics, the existing qualitative evaluation methods neither meet the requirements of determining the toxicity contribution of a single component to mixed pollutants nor meet the requirements of predicting the toxicity of a mixture of specific known components. Therefore, more efforts have been made on the quantitative assessments and predictions of joint toxicity of multi-component mixture (Altenburger et al., 2003). Generally, the combined toxicity of the multi-component was determined using a fixed ratio design. Always, the EC50 value of each component within the mixture is constituted a fixed ratio design to evaluate the joint effect. The EC50 value is defined as the concentration that produces a 50% decrease in light emission, obtained from the concentration-response relationship, which could calculate from regression models (Table 1). Next, the joint toxicity of multi-component mixtures would be predicted using disparate models when mastering some knowledge of EC50 of an individual component.

Graphical Methods

Isobologram

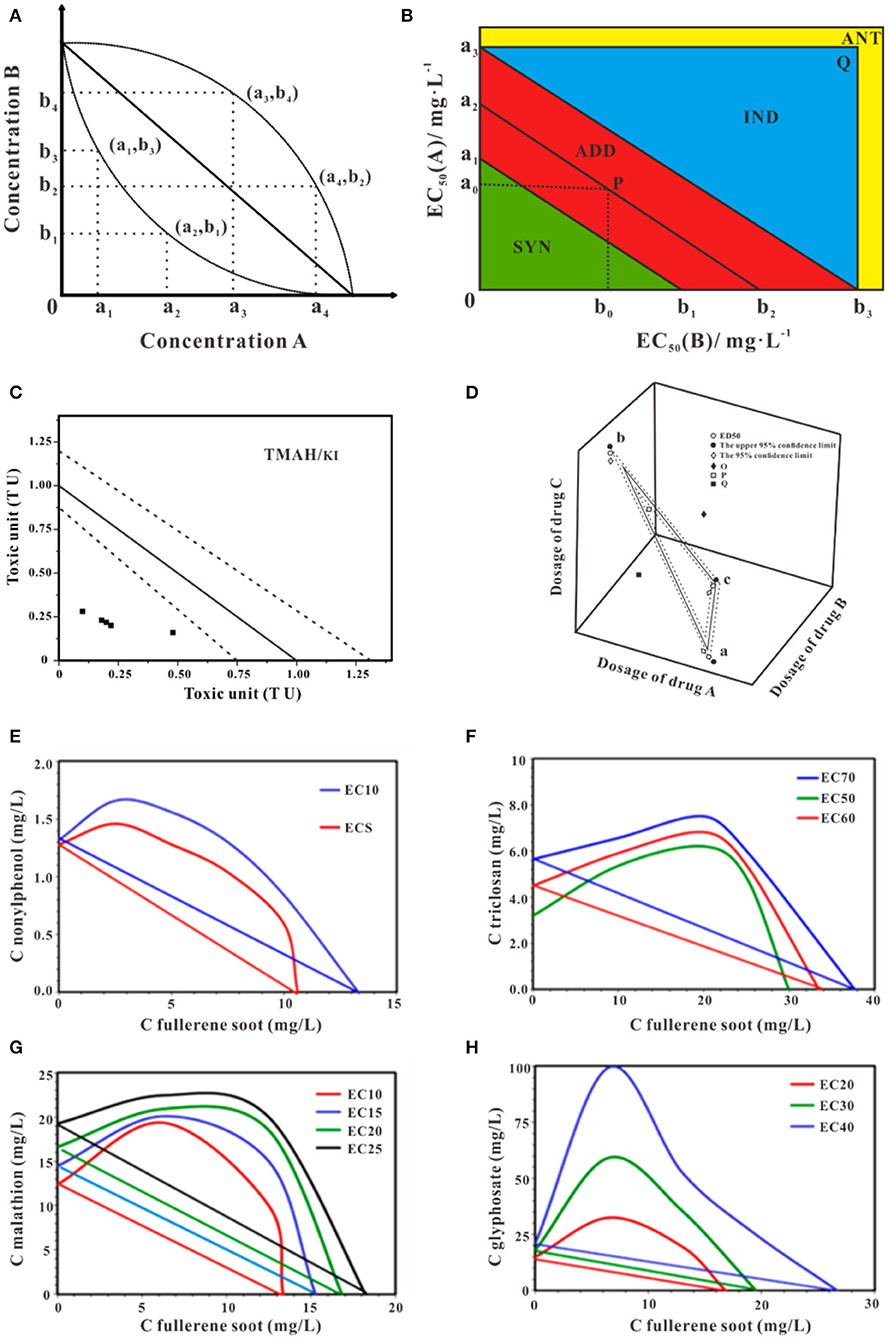

Isobologram was originally developed by Loewe and Muischnek (1926). This method can be used to determine whether the multi-component mixtures behaved in similar modes of action. The straight-line presents the theoretical additive effect of the two components connect two individual effects caused by the fixed concentration. The accuracy of the estimated intercepts of the theoretical isobole with the axis affects the degree of deviation of observed data and experimental data. In many cases, the deviation may result in inadequacy predication. Bernbaumhas put forward interaction index (CI) to directly present the effects on non-interactive multi-compounds mixtures from the dose-effect curve of the individual compound (Berenbaum, 1981). The graphical representation is shown in Figure 3A. In the binary mixture, the equation of the CI is showed in Equation (1). In this equation, a1 and b1 are the dose of components in the mixture, A and B are the dosed of the individual agents giving rise to the same effects as the mixtures. The combination index (CI) determinates the joint effect of the combinations, that shows in Figure 6.

Figure 3. Schematic isobologram for toxicity assessment. (A) The effect of components A+B at random mixture ratio in the Cartesian plane at a given effect level should be theoretically located on the straight line. The upward and downward concave lines act antagonistically and synergistically, respectively. (B) Improvement equivalent effect picture of joint toxicity. With different toxic ratios, the isobologram method may yield distinct joint effects (Ding et al., 2015). (C) Isobologram of TMAH and KI mixture. The solid straight line indicates theoretical additive toxicity. Dot lines indicate 95% confidential interval of the theoretical additive effect (Mori et al., 2015). (D) The theoretical isobologram of the combination of three substances (Huang et al., 2019b). (E) Isobologram for a mixture of fullerene soot and nonylphenol (Sanchis et al., 2016). (F) Isobologram for a mixture of fullerene soot and triclosan (Sanchis et al., 2016). (G) Isobologram for the mixture of fullerene soot and malathion (Sanchis et al., 2016). (H) Isobologram for the mixture of fullerene soot and glyphosate (Sanchis et al., 2016). Adapted and modified with permission from Ding et al. (2015), Mori et al. (2015), Huang et al. (2019b) and Sanchis et al. (2016).

Applied with the 95% confidence interval to simplify the process of the judgment, Ding proposed an improvement approach to characterize the binary toxicities of mixtures and applied this judgment to evaluate the joint toxicity of antibiotics successfully (Figure 3B) (Ding et al., 2015). The EC50 of compounds A and B are presented by a2 and b2, respectively. (a1, a3) is the 95% confidence limit of a2, while (b1, b3) is the 95% confidence limit of b2. The values a0 and b0 represent the equivalent concentration of EC50 for mixture A and B. According to the location of P (a0, b0), the joint toxicity effect of mixture A and B can be judged. If P is located between line a1b1 and a3b3, the joint effect is additive, if P is underline a1b1, the joint toxicity is synergy if P is above line a3b3 and in the triangle a3b3Q, the joint toxicity is independent and if P is located outside the rectangle a3Ob3Q, the joint effect is antagonistic. Much of the available literature on isobologram deals with the question of mixtures toxicity of multi-component. Using the experimental data of poly and perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) based on an amphibian fibroblast cell line, Hoover et al. employed the isobolograms to ascertain the interaction type of the binary mixtures of PFAS, the additive effects were shown in most combination tests (Hoover et al., 2019). Mori et al. in his research conducted isobologram analysis which based on toxic unite (TU) to explore the synergism of the mixture of Tetramethylammonium hydroxide (TMAH) and potassium iodide (KI) to Daphnia magna, using four mixture ratios of TMAH and KI (4:1, 3:2, 1:1, 1:4), as shown in Figure 3C (Mori et al., 2015). Similarly, the bioluminescent inhibition of V. fisheri by exposure to binary mixtures of fullerene soot and nonylphenol (Figure 3E), triclosan (Figure 3F), malathion (Figure 3G), and glyphosate (Figure 3H) using isobologram were discussed, indicating antagonism (Sanchis et al., 2016). Moreover, if three substances are used together, the equivalent surface is shown in Figure 3D. The method of judging the toxicity effect of the three substances is the same as that of a binary substance (Huang et al., 2019b). One should be cautious, isobologram is a graphical method so that variability of date can-not be reflected in this approach and visualization of the effect of mixtures is different, and the graphics draw require large data sets to produce sufficiently reliable results (Berenbaum, 1981; Cassee et al., 1998; Meadows et al., 2002). It is worth mentioning isobologram is unconcerned about chemical structures or modes of action of the individual chemical.

Response Surface

Response or effect surface methodology is based on mathematical relationships, which is obtained by multiple linear regression. The zero interaction responses surface for dose additivity method is depicted in the Equation (2).

where dA, dB represents the dose of components A and B in the mixture. E is the zero interaction combinations effect. The variable α and μ mean the EC50 and slope, respectively.

In the case of significant, the response surface for binary components mixtures can be displayed in three dimensions. The concentration of the two substances is expressed as X-axis and Y-axis, respectively. The combined effect of the two substances is showed as Z-axis. The response surface is displayed by different mathematical model fitting. Neither the synergistic effect nor antagonistic effect of the response surface is flat, because of the two components non-existence of interaction. Ren et al. analyzed the binary effect of copper and lead toward luminescent bacteria based on the response surface, as shown in Figure 4A. They found the transition between different effects with the concentration of metal in the mixtures (Ren et al., 2004). Similarity, Tsai et ai. used an isobologram analysis to test combinations of two drugs etoposide and cisplatin against NCI-H226 cell lines, the results obtained from the preliminary analysis are shown that there was no synergism between etoposide and cisplatin at the 50% level, the sketch modified from Groten et al. (Figure 4B) (Tsai et al., 1989; Groten et al., 2001). It should be noted if predictions for doses extend intended range may result in deviations. Moreover, the approach is related to the relatively large number of parameters that must be determined by non-linear regression techniques, which requires a lot of experiments.

Figure 4. Two examples of response surface modeling. (A) is the response surface for Cu2+- Pb2+ mixture with a metal concentration in coded units (Ren et al., 2004). (B) is a color-coded (Loewe) additivity surface which compared with experimental combination data for the cytotoxic effect of etoposide–cisplatin combinations on NCI-H226 cell lines in ACL-4 medium (Groten et al., 2001). Adapted and modified with permission from Ren et al. (2004) and Groten et al. (2001).

Methods Based on Toxic Unite

Sprague and Ramsay first proposed Toxic Unit (TU) concept to describe the contribution of the individual component to the overall effect (Sprague and Ramsay, 1965). In the luminescent bacteria toxicity assay, the relative luminescence intensity value (RLU) decreased with the toxic substance mass concentration increased. While TU is derived from scaling a measured compound concentration to its inherent EC50 (Fulladosa et al., 2004). The TU concept has been applied to weigh the effect of single chemicals for the assessment of joint toxicity, can be calculated by Equations (3–5):

where ci represents the concentration of component i. When the mixture is at its EC50, TUi is the toxic unit of i, M is the sum of the toxic units, (TUi)max is the maximum toxic unit of the mixture, and M0 is the ratio of M and (TUi)max.

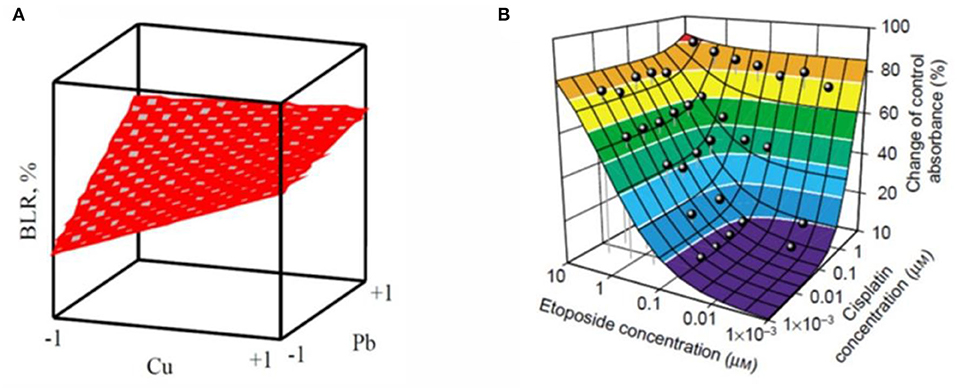

In such a way, M quantified the joint effect that showed in Figure 5 (Chen and Huang, 1996). This approach is relatively simple and can roughly reflect the relationship between the reaction mixtures, the central premise of this concept is that each of these components alone cannot produce any effect.

Figure 5. The joint effect is quantified numerically using different methods. Distinctive colored blocks represent a distinctive joint effect type.

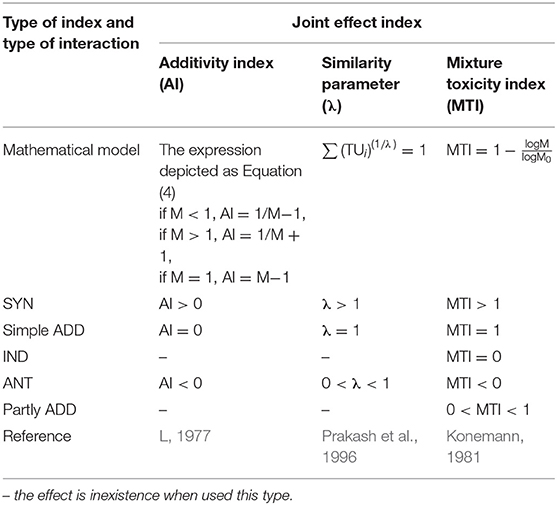

Based on the concept of TU, some other joint effect indexes have been proposed to perfect the evaluation system (Table 2). The evaluation expressions are concise and the model expectations are replaced by a value to quantify the degree of deviation. However, there are still some inevitable limitations: (1) Only EC50 value is provided in the indexes, the evaluation about different levels are unavoidable lost. (2) Similar to the isobologram method, experimental variability also consists of these joint effect indexes method, it is unlikely to meet calculated responses precisely (Altenburger et al., 2003). In some cases, the combination index associated with the isobologram was put forward to address the issue of combination ecotoxicological assessments, effectively (Chou, 2006; Wang et al., 2015d; Godoy et al., 2019).

Apart from the fore-mentioned joint effect indexes, other mathematical models can predict and analyze the joint effect of the binary chemical mixtures. The models always analyze the difference between the calculated value from the model and the observed value from the actual experiments. In this review, two popular evaluation approaches are recommended in detail.

The first approach (referred to statistical approach 1) was proposed by Ribo and Rogers (1990), which assumed that two in a mixture have the same TMOA do not react with each other. The interactive toxicity in that binary mixtures was studied by calculating the difference (EC50,Diff) between the observed toxicities (EC50,Obs) of the binary mixtures with the calculated toxicities (EC50,Calc). The computed mixture toxicities were calculated as Equations (6) and (7).

where CM is the sum of the concentrations of the substances in the binary mixture (Cx and Cy) and the EC50,x, and EC50,y is the effective concentrations representing the observed toxicity of each substance separately. The obtained EC50,Diff value implies the type of interaction between the two substances in the mixture (Figure 5). ADD effect is expressed when the difference is considered statistically non-significant (at a 95% confidence level), the definition of ADD effect is also applied to the following statistical approach 2. With this approach, Fulladosa et al. predicted the toxicity of the possible binary equitoxic mixtures of Co, Cd, Cu, Zn, and Pb to A. fischeri. The research showed the most combined effect of the metals was antagonistic for Co-Cd, Cd-Zn, Cd-Pb and Cu-Pb, while the synergistic effect for Co-Cu and Zn-Pb and merely additive in some cases (Fulladosa et al., 2005).

The second popular approach (referred to statistical approach 2) postulated that there may be interactions between two chemicals that act independently on biological models through different mechanisms. For that reason, the computed mixture toxicities can be expressed as new toxicity units (TU), defined as TU= 100/EC50, the definition is different from the above classical TU. The results can be calculated by Equations (8) and (9).

where TUX and TUY are the toxicity units of X and Y, TUHo (X+Y) is the toxicity units representing the a priori expected toxicity of a mixture of two components X and Y. The interaction effect was indicated by TUDiff value (Figure 5). Fulladosa et al. studied binary As (V) species mixtures based on the statistical analysis of TUObs and TUHo, they noted that As (V) species mixture interaction types were ANT at the pH of 6 and 7 (Fulladosa et al., 2004).

Based on the derivative models associated with TU, several studies have been conducted for ecotoxicity assay of diverse pollutants toward luminescent bacteria, which are categorically reviewed as shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Characterization of the acute toxicity of multi-component mixtures assessments associated with TU by luminescent bacteria.

All of the methods mentioned above are not considered the toxic mode of actions. The isobologram and response surface method are always addressed the binary toxicity of two-components mixtures. The toxic unit and corresponding methods except the statistical approach 2 (referred to TUDiff), assumed that no interaction among the components in the mixture. It is decisive to take advantages and disadvantages into consideration and choose the appropriate method for joint toxicity evaluation.

Methods of Concentration Addition and Independence Action

Concentration Addition Method

As reported by the EPA (EPA, 2000), the additivity is defined as “when the effect of the combination is estimated by the sum of the exposure levels or the effect of the individual chemicals,” In the context of the above definitions, the definitions about “effect” and “sum” draw forth two classical mathematical models. One is Concentration addition (CA, also termed Dose Addition or Loewe additivity), which assumes the constituents in a mixture has the same TMOA, differing in their efficacy. The joint effect of compound mixtures that have the same TMOA can be calculated using the CA model based on the concentration-response relationship of single substances (Loewe and Muischnek, 1926). The mathematical expression of CA by Equation (10):

where ECx,mix is the effective concentration of the mixture eliciting x% effect, ECx,i denotes the concentration of the ith component when exists individually and elicits the same effect (x%) as the mixture, pi is the molar concentration ratio of the ith component in the mixture.

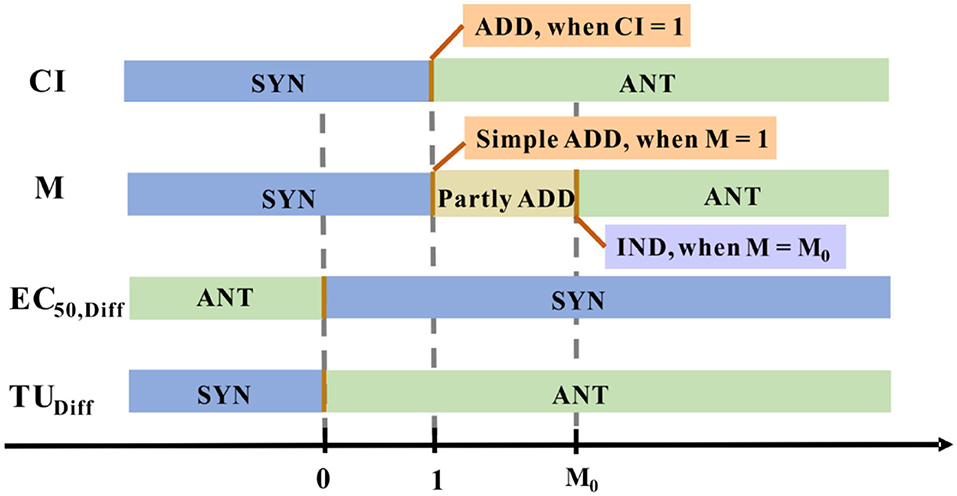

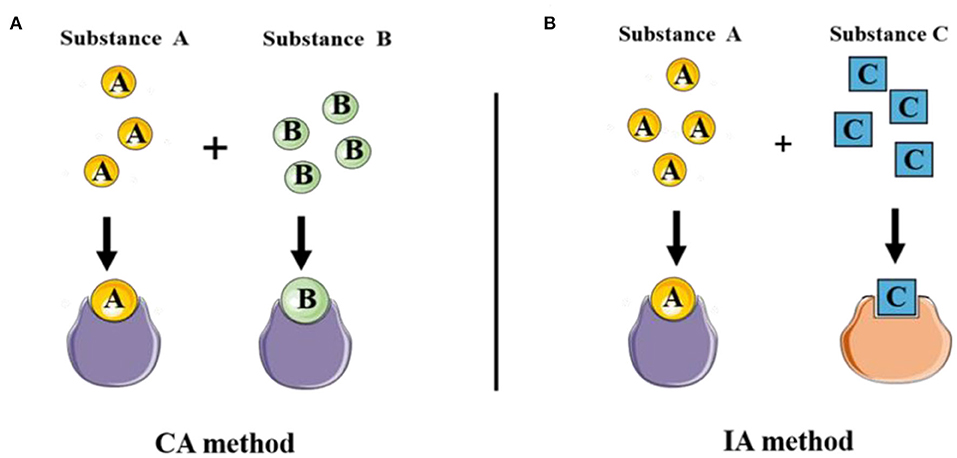

CA implies that two (or more) components act on acceptors with common TMOA indiscriminately. That is to say, components can be substituted for each other in the mixtures (Figure 6A). The concept of CA hypothesized the combined effect may develop in the presence of multi-components. This hypothesis is significant because different categories of organisms in the ecosystem are exposed to a mixture of pollutants.

Figure 6. The diverse toxic mode of actions of classical joint prediction model of Concentration addition and Independent Action. (A) CA method was used to evaluate the joint toxicity of chemical substances with the same mechanism of action. (B) IA method was applied to evaluate the combined toxicity of multi-component with the different mechanisms of action.

Independent Action Method

In another case, the resistance of the organism to one component can not be replaced by another component in the mixture. That is to say, the response of two substances is statistically independent, the action mode of which belongs to different TMOAs (Figure 6B). The model IA model (or response addition) is another approach was hereby proposed to assess the mixture toxicity of components with dissimilar TMOAs, which means multi-component interaction with different target sites (Fraser, 1872; Bliss, 1939). IA model is commonly defined as:

where E(cmix) is the overall effect caused by the total effect of the mixture, cmix is the total concentration of a mixture; E(ci) is the value that denotes the single effect of the ith component corresponds to the concentration of ciin the mixture. The IA model is apt to predict the joint effect of mixtures with definite compositions.

Which of the Two Models, CA or IA, Predict the Date More Precise?

From IA expression, we can conclude that toxicity assessment based on IA relies on the knowledge of the individual effect, which required from the concentration-response curves of all individual component. Moreover, E(ci) is lower than E(cmix) commonly (Junghans et al., 2006; Backhaus and Faust, 2012). That is, the limitation of IA may provoke the accuracy deviation of some predictions. Considering the simplicity ease to utilization, TU based on the CA model has been used in the context of unknown toxic effects of a single component.

There are partly researches were implemented to investigate the feasibility of CA and IA (Zhang et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2009; Zhou et al., 2010; Mo et al., 2014; Villa et al., 2014; Tong et al., 2015). It is not to say, CA (or IA) is only propitious to the similar (dissimilar) toxicology modes of action. The accuracy of CA even for the prediction of the toxicity of multi-component mixture composed with different TMOAs is investigated. Design uniform equivalent-effect concentration experimental method, the combined toxicity prediction of six organophosphorus pesticides (Fenitrothion, Malathion, Dicapthon, Chlormephos, Methyl parathion and Famphur) based on V. qinghaiensis sp.-Q67 can be precisely assessed by CA (Zhang et al., 2008). Others (Junghans et al., 2006; Zhou et al., 2010) also validated that CA may be a reasonable assumption for the toxicity of the multiple-component mixtures of pesticides regardless of the similarity or dissimilarity of their TMOA. Simultaneously, CA and IA are feasible for predicting the toxicological effect of some specific mixtures. Villa et al. tested the toxicity of complex mixtures of chemicals including narcotics, polar narcotics, herbicides, insecticides and fungicides toward A. fisheri. In this experiment, the set of chemicals was attributed to different groups on account of dissimilar toxicology modes of action. The finding demonstrated that CA and IA models are both feasible for predicting the toxicological effect of mixtures, and the difference between the two models was never higher than a factor of four (Villa et al., 2014). However, some researchers believe that the applicability of the two models remains a matter of debate in terms of accuracy in predicting the combined effects of mixtures. The potential risk management options should be studied more carefully (Carbajo et al., 2015; Godoy and Kummrow, 2017; Yang et al., 2017).

Integrative Model of CA and IA

Some toxicants are composed of the components with similar or completely different toxic modes of action in the ecological environment. That is to say, some of which may have the same mode of action, while others may differ. Therefore, both the CA and the IA model may be not suitable for evaluating the combined toxicity of these mixtures. To work this out, the integrative models were developed to predict the toxicity of those complex mixtures (Ra et al., 2006; Qin et al., 2011; Kim et al., 2014; Mo et al., 2017). Among them, the TSP (two-stage prediction) model is one of the most commonly used approaches based on the integrative model concept (Mo et al., 2017). The basic principle of the TSP model is to apply the CA model and IA model that divided in stages to predict the joint toxicity of mixtures as following: In the first stage, the components in the mixture with similar TMOA are assigned into the same group, and joint toxicity of each group was calculated using CA model (Equation 10). In the second stage, the IA model is used to predict the mixture toxicity of all the groups with different TMOAs (Equation 11). In this way, the prediction of the combined toxicity of the mixture with similar and different TMOAs can be predicted.

Mo et al. selected six phenolic compounds (Methyl phenol, 2-Nitrophenol, 4-Nitrophenol, 2.4-Dichlorophenol, Phenol and 2-chlorophenol) and heavy metals (Cr, Cu, Ni, Cd, Ag, and Hg) with different TMOAs to compose the mixtures with V. qinghaiensis sp.-Q67, a series of mixtures were designed with equivalent-effect concentration and fixed concentration ration. By comparing the prediction error of CA, IA and TSP models, the TSP model exhibited better performance on predicting the overall effect of a mixture containing compounds with different TMOAs than CA and IA models (Mo et al., 2017). The predicted combined toxicity of mixtures of imidazolium and pyridinium ionic liquids in the ratios of their EC50, EC10, and NOEC on luciferase also showed that the TSP method preceded the CA and IA methods effectively (Ge et al., 2014).

The above methods are both attributed to traditional experimental methods, with the aid of the individual concentration-effect relationship so as the final judgment of the multi-component mixture can be confirmed. Moreover, experimental toxicology studies usually used experimental animals, tissues, bacteria, cell. It is no doubt these requirements have improved the complexity of the operations. Hence, researchers are devoted to developing alternative methods to conquer these limitations of traditional experimental methods. QSAR (Roy et al., 2015a,b), Read-across (RA) (Jeliazkova et al., 2010), Molecular docking (Yao et al., 2013) and Expert systems (Roy and Kar, 2016), are deemed faster, cheaper and can manifest more information (Mwense et al., 2004). In these developing alternative methods, the QSAR model is one of the most widely used methods in silico.

QSAR Assisted Toxicity Prediction

QSAR, as a calculated method has been widely applied in toxicology. QSAR is an acronym for Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship. The concept was delivered in 1872, and the modern age of QSAR analysis originated from the works of Hansch et al. (1962). By mathematical function, QSAR is a statistical approach which express a relationship between the magnitude of biological effect (BA) and changes in a molecular structure, as Equation (12) showed:

where i denotes a specific chemical of a series, this series may be of homogeneous, or of heterogeneous substances.

In the study of constructing a QSAR model, it is decisive to acquire and screen molecular structure descriptors (also called indicators). At present, more than 3,000 molecular descriptors have been defined and applied to QSAR models to predict group biotoxicity. Choose distinct indicators when adopting the QSAR model that will affect the validity of the predicted results, therefore the preparation of the indicators is the key to the construction (Khan et al., 2020). Among abundant kinds of indicators, the partition coefficient of a chemical between n-octanol and water is supposed to be the most effective indicator (Tichy et al., 2008). However, it is difficult to use Kow to determine the combined toxicity of mixtures, since the available date was obtained by UV spectrophotometry or HPLC is only suitable for determining the Kow of single chemicals. Furthermore, Verhaar extended the C18-EmporeTM disks/water partition coefficient (KMD) to predict the bioconcentration of mixtures, which was found to have a close relationship with logKow (Verhaar et al., 1995). The C18-EmporeTM disks/water partition coefficient (KMD) can be calculated from Equation (13), the unmeasurable problem was successfully solved.

where W is the volume of solution, V is the volume of hydrophobic phase, is the initial amount of chemical i in water, n is the total number of individual chemicals in the mixture, and KSDi is the partition coefficient of individual chemical i. The value of W/V was suggested to be 6.8 × 105.

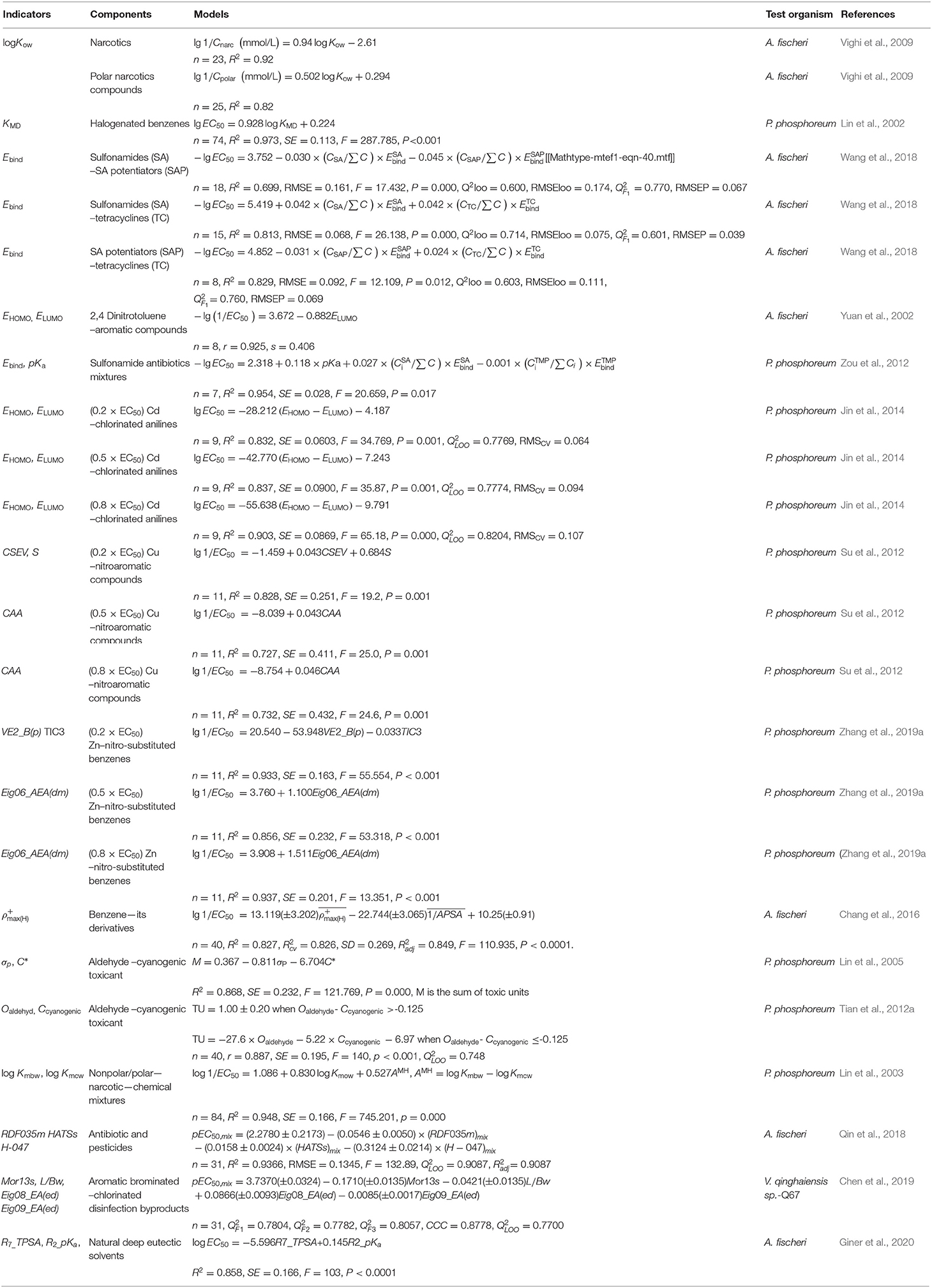

Not limited to the partition coefficient of chemical between n-octanol and water, studies concerned other kind indicators to employ QSAR to assess ecotoxicity evaluations of diverse pollutants toward familiar luminescent bacteria, A. fisheri, P. phosphoreum and V. qinghaiensis sp.-Q67, which are categorically reviewed as shown in Table 4.

Researches about QSAR are still of significant interest in the development of innovative models in environmental toxicity prediction. The emergence of the QSAR models fills the gap in predicting the combined toxicity of organic compounds and heavy metals since the information in this field is still scarce. Jin et al. developed three QSARs to determine the individual EC50 of Cd and nine chlorinated anilines (o-chloroaniline, m-chloroaniline, p-chloroaniline, 2,3-dichloroaniline, 2,4-dichloroaniline, 2,5-dichloroaniline, 2,6-dichloroaniline, 3,4-dichloroaniline, and 2,4,5-trichloroaniline) with P. phosphoreum, setting three different levels of Cd concentrations (low, medium and high levels) to mix with chlorinated anilines and the results showed that the number of chlorinated anilines manifesting synergy with Cd is decreasing as the concentration of Cd increases. The robustness of the models was confirmed by comparing the experimental and predicted values, and all the relative error values remain within 16% (Jin et al., 2014). Likewise, the joint toxicities of Cu (low, medium and high levels) with 11 nitroaromatic compounds (nitrobenzene, o-dinitrobenzene, m-nitrobromobenzene, p-nitrobromobenzene, o-nitroaniline, p-nitroaniline, p-nitrobenzoic acid, o-nitrophenol, m-nitrophenol, p-nitrophenol and 2,4-dinitrophenol) were studied by P. phosphoreum with developed QSAR analysis, there is a good agreement between the predicted values and experimental with R2 = 0.764, P = 0.000, (Su et al., 2012). By drawing on the study of Su's, Zhang's, Su, Zhang, Li, Qin and Zhang (2019a) work on the acute toxic effect of mixtures between metal Zn and above-mentioned 11 nitroaromatic compounds established robust QSAR models to predict the joint interaction when combined with Zn at low, medium, and high concentrations (Zhang et al., 2019a). Not limited to heavy metals and organics, the joint toxicity of mixed organics can also be predicted by QSAR models. Qin et al. developed a generalized QSAR model for predicting the additive and non-additive toxicities of multi-component mixtures, the experiment tested the joint toxicity of 45 multi-component mixtures composed of two antibiotics (Tetracycline hydrochloric and Chloramphenicol) and four pesticides (Metribuzine, Trichlorfon, dichlorvos, Linuron) to A. fisheri. Compared with classical CA and IA models, the result demonstrated that the QSAR model exhibited high predictive capability for predicting joint toxicity (Qin et al., 2018).

The Potential Mechanisms of Joint Toxicity

Though more and more efforts have been devoted to investigating mechanisms with mixture toxicity, joint toxicity mechanisms, especially for specific pollutants, are still too complex to figure out. In recent years, there has been growing evidence regarding the experimental factors including mixture ratio setting and complexity of toxic compounds play a vital role in shaping the joint effect, which in turn impacts the determination of toxicological mechanism. At the same time, considering the environmental factors on the joint effect study, the ecological environmental media should be researched more adequately. Because of the above-mentioned reasons, the studies concentrated on the mechanisms of joint toxicity toward luminescent bacteria are merely few. Analogous to other test organisms, impair mechanisms of the luminescent bacteria are speculated in this section.

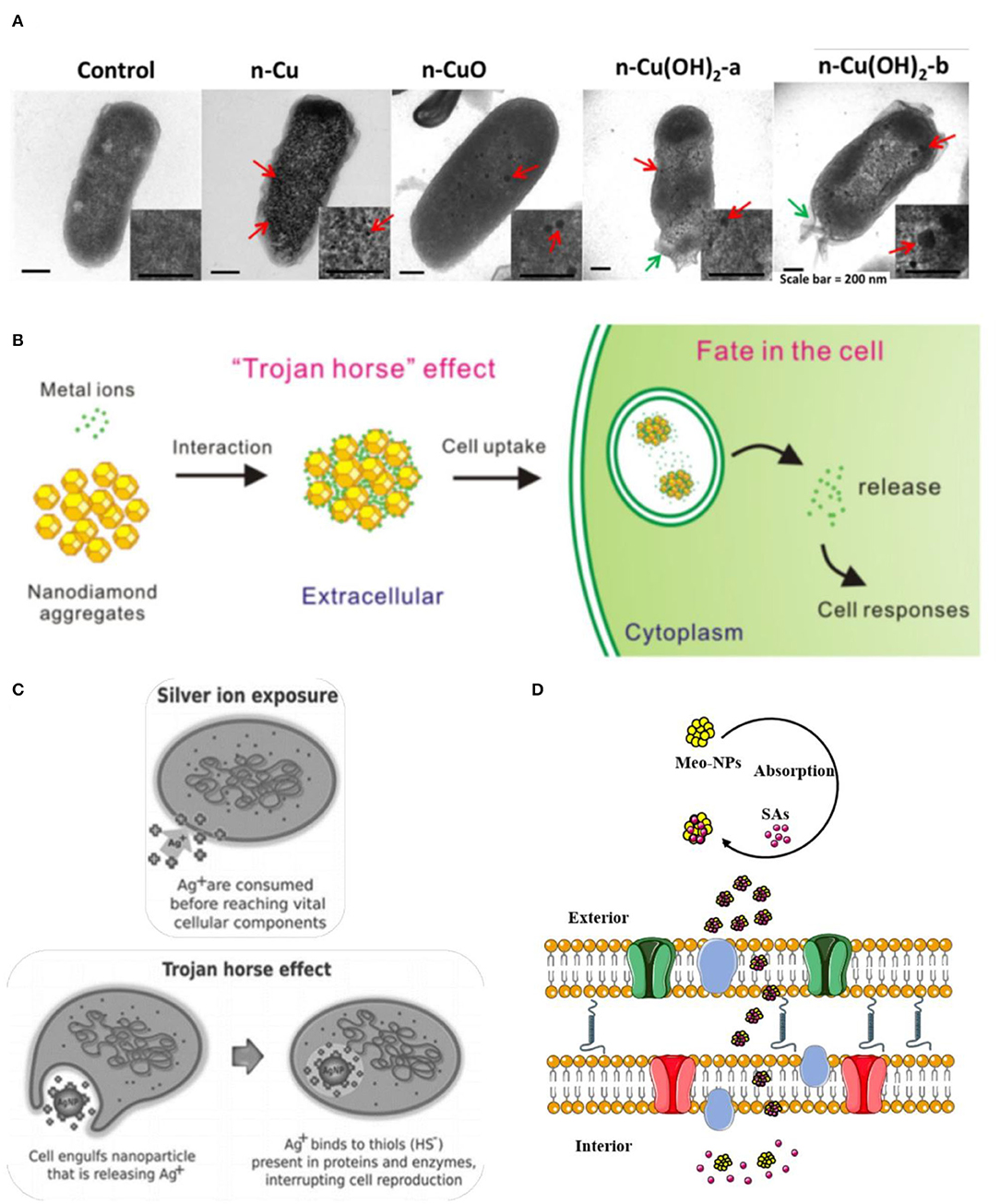

Trojan-Horse Effect and Reverse Trojan-Horse Effect

The cellular membrane acts as a significant site for interactions of chemicals. A wealth of reports showed that physiological activities in the inner of an organism are related to the cellular membranes. The functions of the cell membrane are considered in many aspects, such as transmembrane transport of small molecules, energy exchange, cell recognition, cell-mediated immunity, nerve conduction and metabolism regulation and so on (Oxender and Fox, 1978; Alberts et al., 1989). The impact of NPs on the membrane or wall integrity of algal cells (Angel et al., 2015; Sendra et al., 2017; Sousa et al., 2019) and bacteria cells (Kaweeteerawat et al., 2015; Martín-de-Lucía et al., 2017; Pulido-Reyes et al., 2017) (Figure 7A), has been evaluated extensively. Indications of damaged cell membrane make it interesting to study the potential biotoxicity effect of multi-component mixtures. A principal effect hypothesis concerning the cellular membrane damage which is described as the “Trojan-horse effect” has garnered considerable attention (Limbach et al., 2007). This hypothesis was first proposed and adopted gradually in nanomaterial. Owing to the large surface area, the ability of nanomaterials to act as carriers for a wide range of heavy metals and organic pollutants (Liu et al., 2018). CNTs and C60 are confirmed to carry heavy metals and dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene (p, p'-DDE) entry into the inner cell via damaging cell membranes, respectively. Except for membrane disruptions, the entry process can impair other intracellular structures (receptors, ion channels, transporters, glycoproteins) (De La Torre-Roche et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2015a). The interaction toxicity of the Pb-nanotube also showed a synergistic effect, increasing over five times compared with the toxicity of single Pb (Martinez et al., 2013). Carbon adsorption of pollutants by nanomaterials was common in other organisms, like Japanese medaka (Su et al., 2013), Daphnia magna (Simon et al., 2015), Cyprinus carpio (Zhang et al., 2007). Based on the Trojan-horse effect, the schematic illustration of adsorption of metals ions on nanodiamonds (NDs) and the AgNP (Silver Nanoparticles) exposure, were shown in the Figures 7B,C (Quadros and Marr, 2012; Zhu et al., 2015). That mechanism also applied to luminescent bacteria, which elucidated that the synergistic effect of sulfonamides (SAs) with metal oxide nanoparticles (Meo-NPs) toward A. fischer (Figure 7D; Wang et al., 2016). As absorbent and carrier, metal oxide nanoparticles facilitated the entry of SAs into the inner of membrane completely and finally upon reaching the target site and release the encapsulated SAs molecules by making use of local physiological stimuli present here.

Figure 7. The potential mechanism of Trojan-horse type. (A) High—resolution transmission electron microscopy (TEM) micrographs of E. coli cells treated with nano Cu to CuO and Cu(OH)2. Red arrows indicated Cu particles; green arrows indicate membrane damage (Kaweeteerawat et al., 2015). (B) The scheme of absorption of metal ions on Nanodiamond (NDs) led to cellular toxicity (Zhu et al., 2015). (C) Comparison of silver ion and AgNP exposure, the toxicity of AgNP are more toxic than those of silver ions by themselves because the ions would be largely cvnonsumed in the process of penetration, which chimed in with the Trojan horse effect (Quadros and Marr, 2012). (D) Meo-NPs act like Trojan-horse to deliver SAs into the inner cell membrane (Wang et al., 2016). Adapted and modified with permission from Kaweeteerawat et al. (2015), Zhu et al. (2015), Quadros and Marr (2012), and Wang et al. (2016).

At the opposite extreme from the “Trojan-horse effect,” the term “Reverse Trojan-horse effect” is a relatively new name for referring to describing these phenomenons that antagonism is the predominant effect of multi-component mixtures (Barranger et al., 2019). Using A.fisheri, Sanchiss' study of the combined ecotoxicity of fullerene-soot and co-contaminants as malathion, diuron, triclosan, and nonylphenol indicated the joint effect of antagonism in all of the cases (Sanchis et al., 2016). In their analysis of this result, Sanchis et al. mentioned the special situation of aromatic rings as a tentative substance of allowing the production of micelles and changing the state of aggregation of fullerene aggregates. Therefore, the simple surface sorption process cannot clarify the antagonism between the fullerene-soot and co-contaminants. Interestingly antagonism appeared at low effect levels in wastewater–nanoparticle mixtures using recombinant bioluminescent cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. PCC 7120 strain CPB4337 (Martín-de-Lucía et al., 2017). Furthermore, the other four categories were added by Naasz et al. to discriminate different categories to recommend the joint toxicity upon mixture exposure, the additional mechanisms that are Surface enrichment, Retention, Inertism and Coalism (Naasz et al., 2018).

Competition for the Active Site

In the plasma membrane, some transmembrane proteins serve as receptors to detect and transduce chemical signals in the cell environment. According to the receptor theory, toxic targets are mainly receptors on the cell surface or in the nucleus and cytoplasm (Wu et al., 2016). The receptor theory represented that one pollutant with better absorption may replace those with poor adsorption when pollutants with similar chemical properties compete on the cell surface that will cause the specific biological accumulation and biotoxicity (Elliott et al., 1986; Nirmalakhandan et al., 1994; Posthuma et al., 1997). A study on the mixture toxicity of heavy metals demonstrated that the majority of sites were already immobilized by ions to the extent that new chemicals hardly have a chance to bind, such a strategy may fluctuate the joint effect along with competition for toxic sites among coexisting cations (Zeng et al., 2015).

Other Factors Affect Toxicity Prediction

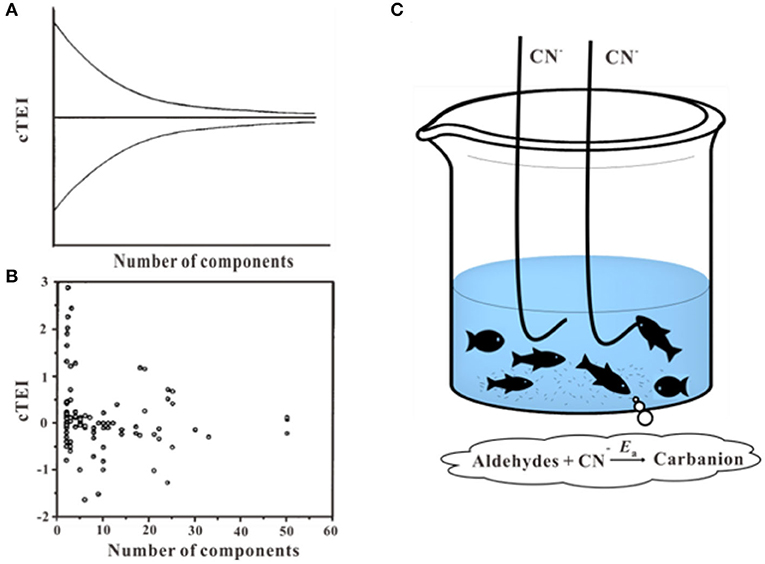

It has been mentioned, the joint effect of chemical mixtures varies due to its type of compounds and toxic ratios (at their equitoxic ratios or non-equitoxic ratios). The multi-chemical mixture may show dissimilar toxicity response with a different ratio of the same chemicals (Kar and Leszczynski, 2019). For narcotic toxicants, funnel hypothesis was put forward to interpret the fact that as the number of components in a mixture increase, the range of deviation from toxic additivity decreases (Rayburn et al., 1991; Warne and Hawker, 1995) (Figures 8A,B). With the number of components increases, the joint effect tends to show additivity effect and toxicity reduction can be regarded as a result of dissolution and dilution (Altenburger et al., 2000; Backhaus et al., 2000; Faust et al., 2001). The equitoxic mixtures of the reactive chemicals also have the same tendency, mixtures effect is close to additive as the increased number of the components (Tian et al., 2012b). It is necessary to note that there are inconsistent with funnel hypothesis as some ternary mixtures effect showed more synergistic or antagonistic than binary mixtures effect (Cedergreen et al., 2012; Chen et al., 2014, 2015; Wang et al., 2015b,c). Besides, the fishing hypothesis was proposed to explain the variation rules of the joint effects of cyanogenic toxicants and aldehydes (Figure 8C; Li et al., 2014). The hypothesis elucidated why the interactions based on the equitoxic ratios of the different chemicals were stronger than the effects at non-equitoxic ratios. In this hypothesis, the CN− acted as fishhooks and aldehydes acted as fish. A hook only caught one fish when fishing. There is a competition among different types of fish for one hook during the process of fishing, while no competitions among different types of fish. However, there is no uniform explanation for the prediction of different types of interactions in the multi-component mixtures, which remain a rough challenge for ecotoxicology.

Figure 8. Funnel hypothesis and fishing hypothesis. (A,B) Toxicity enhancement index values (cTEI) plotted against the number of components in the mixtures (Warne and Hawker, 1995). (C) Schematic of the fishing hypothesis (Li et al., 2014). Adapted and modified with permission from Warne and Hawker (1995) and Li et al. (2014).

Conclusion and Future Perspectives

Compared with other biological assay methods, luminescent bacteria toxicity assay has the advantages of simple operation, short test time and high repeatability. The results of numerous researches have illustrated the joint effect of multi-component mixtures and described the various types of models involved in joint toxicity prediction based on bacteria toxicity assay. Other studies also attempt to evaluate the toxicity of specific toxins by combining luminescent bacteria with other means such as dual detections by a combination of luminescent bacteria and probe. However, the effect of major factors such as the number of mixed components, the dominating components, and the toxic ratio of individual toxicants, on the joint effect of multi-component mixtures should be considered necessary. To address variable co-exposure scenarios, further research is required to decipher more related indicators to construct a fitting model for the assessment of multi-component mixtures. It would contribute to promoting thus further use of effect-based prediction of ecological environmental quality. Furthermore, the current luminescent bacteria toxicity assay is mostly used for acute toxicity testing, the determination of chronic toxicity exposure based on luminescent bacteria should be refined within the larger regulatory network. The differences between chronic and acute toxicity require further elucidation.

Author Contributions

All authors wrote the manuscript jointly. DW, SW, and LB contributed to reviewing the literature and the write up of the manuscript. MN, SL, and WY contributed to the editing of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant number 2019YFB2103003), the National Science Foundation of China (Grant number 31670512), and Natural Science Basic Research Plan in Shaanxi Province of China (Grant number 2018JM3039).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Aammi, S., Karaca, F., and Petek, M. (2017). A toxicological and genotoxicological indexing study of ambient aerosols (PM2.5-10) using in vitro bioassays. Chemosphere 174, 490–498. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.01.141

Ahn, J. M., Hwang, E. T., Youn, C. H., Banu, D. L., Kim, B. C., Niazi, J. H., et al. (2009). Prediction and classification of the modes of genotoxic actions using bacterial biosensors specific for DNA damages. Biosens. Bioelectron. 25, 767–772. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2009.08.025

Alberts, B., Johnson, A., and Lewis, J. (1989). Molecular Biology of the Cell. New York, NY: Garland Science Press.

Altenburger, R., Backhaus, T., Boedeker, W., Faust, M., Scholze, M., and Grimme, L. H. (2000). Predictability of the toxicity of multiple chemical mixtures to Vibrio fischeri: mixtures composed of similarly acting chemicals. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 19, 2341–2347. doi: 10.1002/etc.5620190926

Altenburger, R., Nendza, M., and Schuurmann, G. (2003). Mixture toxicity and its modeling by quantitative structure-activity relationships. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 22, 1900–1915. doi: 10.1897/01-386

Angel, B. M., Vallotton, P., and Apte, S. C. (2015). On the mechanism of nanoparticulate CeO2 toxicity to freshwater algae. Aquat. Toxicol. 168, 90–97. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2015.09.015

Backhaus, T., and Faust, M. (2012). Predictive environmental risk assessment of chemical mixtures: a conceptual framework. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46, 2564–2573. doi: 10.1021/es2034125

Backhaus, T., Scholze, M., and Grimme, L. H. (2000). The single substance and mixture toxicity of quinolones to the bioluminescent bacterium Vibrio fischeri. Aquat. Toxicol. 49, 49–61. doi: 10.1016/S0166-445X(99)00069-7

Barranger, A., Rance, G. A., Aminot, Y., Dallas, L. J., Sforzini, S., Weston, N. J., et al. (2019). An integrated approach to determine interactive genotoxic and global gene expression effects of multiwalled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) and benzo[a]pyrene (BaP) on marine mussels: evidence of reverse ‘Trojan Horse’ effects. Nanotoxicology 13, 1324–1343. doi: 10.1080/17435390.2019.1654003

Barron, M. G., Conmy, R. N., Holder, E. L., Meyer, P., Wilson, G. J., Principe, V. E., et al. (2018). Toxicity of cold lake blend and Western Canadian select dilbits to standard aquatic test species. Chemosphere 191, 1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.10.014

Belkin, S. (2003). Microbial whole-cell sensing systems of environmental pollutants. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 6, 206–212. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5274(03)00059-6

Berenbaum, M. C. (1981). Criteria for analyzing interactions between biologically-active agents. Adv. Cancer Res. 35, 269–335. doi: 10.1016/S0065-230X(08)60912-4

Bergner, T., Tabib, C. R., Winkler, A., Stipsits, S., Kayer, H., Lee, J., et al. (2015). Structural and biochemical properties of LuxF from Photobacterium leiognathi. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1854(10 Pt A), 1466–1475. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2015.07.008

Bliss, C. I. (1939). The toxicity of poisons applied jointly. Ann. Appl. Biol. 26, 585–615. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7348.1939.tb06990.x

Bourgois, J. J., Sluse, F. E., Baguet, F., and Mallefet, J. (2001). Kinetics of Light Emission and Oxygen Consumption by Bioluminescent Bacteria. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 33, 353–363. doi: 10.1023/A:1010615508916

Boyd, E. M., Killham, K., Wright, J., Rumford, S., Hetheridge, M., Cumming, R., et al. (1997). Toxicity assessment of xenobiotic contaminated groundwater using lux modified Pseudomonas fluorescens. Chemosphere 35, 1967–1985. doi: 10.1016/S0045-6535(97)00271-3

Brodl, E., Winkler, A., and Macheroux, P. (2018). Molecular mechanisms of bacterial bioluminescence. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 16, 551–564. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2018.11.003

Carbajo, J. B., Perdigon-Melon, J. A., Petre, A. L., Rosal, R., Leton, P., and Garcia-Calvo, E. (2015). Personal care product preservatives: risk assessment and mixture toxicities with an industrial wastewater. Water Res. 72, 174–185. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2014.12.040

Cassee, F. R., Groten, J. P., van Bladeren, P. J., and Feron, V. J. (1998). Toxicological evaluation and risk assessment of chemical mixtures. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 28, 73–101. doi: 10.1080/10408449891344164

Cedergreen, N., Sørensen, H., and Svendsen, C. (2012). Can the joint effect of ternary mixtures be predicted from binary mixture toxicity results? Sci. Total Environ. 427–428, 229–237. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.03.086

Chang, C. M., Ou, Y. H., Liu, T. C., Lu, S. Y., and Wang, M. K. (2016). A quantitative structure-activity relationship approach for assessing toxicity of mixture of organic compounds. SAR QSAR Environ. Res. 27, 441–453. doi: 10.1080/1062936X.2016.1207204

Chen, C., Wang, Y., Qian, Y., Zhao, X., and Wang, Q. (2015). The synergistic toxicity of the multiple chemical mixtures: implications for risk assessment in the terrestrial environment. Environ. Int. 77, 95–105. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2015.01.014

Chen, C., Wang, Y., Zhao, X., Wang, Q., and Qian, Y. (2014). Comparative and combined acute toxicity of butachlor, imidacloprid and chlorpyrifos on earthworm, Eisenia fetida. Chemosphere 100, 111–115. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.12.023

Chen, C. Y., and Huang, C. F. (1996). Toxicity of organic mixtures containing cyanogenic toxicants. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 15, 1464–1469. doi: 10.1002/etc.5620150906

Chen, Q., Li, Y., and Li, B. (2020). Is color a matter of concern during microplastic exposure to Scenedesmus obliquus and Daphnia magna? J. Hazard. Mater. 383:121224. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2019.121224

Chen, Y. H., Qin, L. T., Mo, L. Y., Zhao, D. N., Zeng, H. H., and Liang, Y. P. (2019). Synergetic effects of novel aromatic brominated and chlorinated disinfection byproducts on Vibrio qinghaiensis sp.-Q67. Environ. Pollut. 250, 375–385. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.04.009

Chou, T. C. (2006). Theoretical basis, experimental design, and computerized simulation of synergism and antagonism in drug combination studies. Pharmacol. Rev. 58, 621–681. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.3.10

Clemow, Y. H., and Wilkie, M. P. (2015). Effects of Pb plus Cd mixtures on toxicity, and internal electrolyte and osmotic balance in the rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Aquat. Toxicol. 161, 176–188. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2015.01.032

Conforti, F., Ioele, G., Statti, G. A., Marrelli, M., Ragno, G., and Menichini, F. (2008). Antiproliferative activity against human tumor cell lines and toxicity test on Mediterranean dietary plants. Food Chem. Toxicol. 46, 3325–3332. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2008.08.004

Costa, M. B., Tavares, F. V., Martinez, C. B., Colares, I. G., and Martins, C. M. G. (2018). Accumulation and effects of copper on aquatic macrophytes Potamogeton pectinatus L.: potential application to environmental monitoring and phytoremediation. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 155, 117–124. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2018.01.062

De La Torre-Roche, R., Hawthorne, J., Deng, Y., Xing, B., Cai, W., Newman, L. A., et al. (2012). Fullerene-enhanced accumulation of p,p '-DDE in agricultural crop species. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46, 9315–9323. doi: 10.1021/es301982w

De Schepper, W., Dries, J., Geuens, L., and Blust, R. (2012). Sequential partial ozonation for the treatment of wastewater concentrate: practical implications from a conventional and (Eco) toxicological perspective. Ozone Sci. Eng. 34, 163–173. doi: 10.1080/01919512.2012.663328

Deeva, A. A., Zykova, E. A., Nemtseva, E. V., and Kratasyuk, V. A. (2019). Functional divergence between evolutionary-related LuxG and Fre oxidoreductases of luminous bacteria. Proteins 87, 723–729. doi: 10.1002/prot.25696

Ding, S., Wu, J., Zhang, M., Lu, H., Mahmood, Q., and Zheng, P. (2015). Acute toxicity assessment of ANAMMOX substrates and antibiotics by luminescent bacteria test. Chemosphere 140, 174–183. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2015.03.057

Elliott, N. G., Swain, R., and Ritz, D. A. (1986). Metal interaction during accumulation by the mussel mytilus-edulis-planulatus. Mar. Biol. 93, 395–399. doi: 10.1007/BF00401107

Engebrecht, J., and Silverman, M. (1984). Identification of genes and gene-products necessary for bacterial bioluminescence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 81, 4154–4158. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.13.4154

EPA (2000). Supplementary Guidance for Conducting Health Risk Assessment of Chemical Mixtures. Washington, DC: US Environmental Protection Agency.

Faust, M., Altenburger, R., Backhaus, T., Blanck, H., Boedeker, W., Gramatica, P., et al. (2001). Predicting the joint algal toxicity of multi-component s-triazine mixtures at low-effect concentrations of individual toxicants. Aquat. Toxicol. 56, 13–32. doi: 10.1016/S0166-445X(01)00187-4

Feng, J. N., Guo, X. P., Chen, Y. R., Lu, D. P., Niu, Z. S., Tou, F. Y., et al. (2020). Time-dependent effects of ZnO nanoparticles on bacteria in an estuarine aquatic environment. Sci. Total Environ. 698:134298. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134298

Flokstra, B. R., Aken, B. V., and Schnoor, J. L. (2008). Microtox® toxicity test: detoxification of TNT and RDX contaminated solutions by poplar tissue cultures. Chemosphere 71, 1970–1976. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2007.12.020

Fraser, T. R. (1872). Lecture on the antagonism between the actions of active substances. Br. Med. J. 2, 485–487. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.618.485

Fulladosa, E., Murat, J. C., Martinez, M., and Villaescusa, I. (2004). Effect of pH on arsenate and arsenite toxicity to luminescent bacteria (Vibrio fischeri). Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 46, 176–182. doi: 10.1007/s00244-003-2291-7

Fulladosa, E., Murat, J. C., and Villaescusa, I. (2005). Study on the toxicity of binary equitoxic mixtures of metals using the luminescent bacteria Vibrio fischeri as a biological target. Chemosphere 58, 551–557. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2004.08.007

Fuqua, W. C., Winans, S. C., and Greenberg, E. P. (1994). Quorum sensing in bacteria - the luxr-luxi family of cell density-responsive transcriptional regulators. J. Bacteriol. 176, 269–275. doi: 10.1128/JB.176.2.269-275.1994

Ge, H., Lin, Z., Yao, Z., Gao, Y., Cong, Y., and Yu, H. (2014). Balance between herbicidal activity and toxicity effect: a case study of the joint effects of triazine and phenylurea herbicides on Selenastrum capricornutum and Photobacterium phosphoreum. Aquat. Toxicol. 150, 165–174. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2014.03.007

Giner, B., Lafuente, C., Lapena, D., Errazquin, D., and Lomba, L. (2020). QSAR study for predicting the ecotoxicity of NADES towards Aliivibrio fischeri. Exploring the use of mixing rules. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 191:110004. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2019.110004

Godoy, A. A., and Kummrow, F. (2017). What do we know about the ecotoxicology of pharmaceutical and personal care product mixtures? A critical review. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47, 1453–1496. doi: 10.1080/10643389.2017.1370991

Godoy, A. A., Oliveira, A. C., Silva, J. G. M., Azevedo, C. C. J., Domingues, I., Nogueira, A. J. A., et al. (2019). Single and mixture toxicity of four pharmaceuticals of environmental concern to aquatic organisms, including a behavioral assessment. Chemosphere 235, 373–382. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.06.200

Groten, J. P., Feron, V. J., and Suhnel, J. (2001). Toxicology of simple and complex mixtures. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 22, 316–322. doi: 10.1016/S0165-6147(00)01720-X

Gu, M. B., Mitchell, R. J., and Kim, B. C. (2004). Whole-cell-based biosensors for environmental biomonitoring and application. Adv. Biochem. Eng. Biotechnol. 87, 269–305. doi: 10.1007/b13533

Hageman, K. J., Aebig, C. H. F., Luong, K. H., Kaserzon, S. L., Wong, C. S., Reeks, T., et al. (2019). Current-use pesticides in New Zealand streams: comparing results from grab samples and three types of passive samplers. Environ. Pollut. 254(Pt A), 112973. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.112973

Hamdi El Najjar, N., Touffet, A., Deborde, M., Journel, R., and Karpel Vel Leitner, N. (2014). Kinetics of paracetamol oxidation by ozone and hydroxyl radicals, formation of transformation products and toxicity. Sep. Purif. Technol. 136, 137–143. doi: 10.1016/j.seppur.2014.09.004

Hansch, C., Maloney, P. P., and Fujita, T. (1962). Correlation of biological activity of phenoxyacetic acids with hammett substituent constants and partition coefficients. Nature 194:178. doi: 10.1038/194178b0

Hernando, M. D., Ejerhoon, M., Fernández-Alba, A. R., and Chisti, Y. (2003). Combined toxicity effects of MTBE and pesticides measured with Vibrio fischeri and Daphnia magna bioassays. Water Res. 37, 4091–4098. doi: 10.1016/S0043-1354(03)00348-8

Hoover, G., Kar, S., Guffey, S., Leszczynski, J., and Sepulveda, M. S. (2019). In vitro and in silico modeling of perfluoroalkyl substances mixture toxicity in an amphibian fibroblast cell line. Chemosphere 233, 25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.05.065

Huang, L., Li, S., Ling, X., Zhang, J., Qin, A., Zhuang, J., et al. (2019a). Dual detection of bioaccumulated Hg(2+) based on luminescent bacteria and aggregation-induced emission. Chem. Commun. 55, 7458–7461. doi: 10.1039/C9CC02782C

Huang, R. Y., Pei, L., Liu, Q., Chen, S., Dou, H., Shu, G., et al. (2019b). Isobologram analysis: a comprehensive review of methodology and current research. Front. Pharmacol. 10:1222. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.01222

Inouye, S. (1994). NAD(P)H-flavin oxidoreductase from the bioluminescent bacteria, Vibrio-fischeri ATCC-7744, is a flavoprotein. FEBS Lett. 347, 163–168. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00528-1

Ivey, C. D., Besser, J. M., Steevens, J. A., Walther, M. J., and Melton, V. D. (2019). Influence of dissolved organic carbon on the acute toxicity of copper and zinc to white sturgeon (Acipenser transmontanus) and a cladoceran (Ceriodaphnia dubia). Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 38, 2682–2687. doi: 10.1002/etc.4592

Jarque, S., Masner, P., Klanova, J., Prokes, R., and Blaha, L. (2016). Bioluminescent vibrio fischeri assays in the assessment of seasonal and spatial patterns in toxicity of contaminated river sediments. Front. Microbiol. 7:1738. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01738

Jeliazkova, N., Jaworska, J., and Worth, A. P. (2010). Open source tools for read-across and category formation. Silico Toxicol. 17, 408–445. doi: 10.1039/9781849732093-00408

Jiang, B., Li, G., Xing, Y., Zhang, D., Jia, J., Cui, Z., et al. (2017). A whole-cell bioreporter assay for quantitative genotoxicity evaluation of environmental samples. Chemosphere 184, 384–392. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.05.159

Jin, H., Wang, C., Shi, J., and Chen, L. (2014). Evaluation on joint toxicity of chlorinated anilines and cadmium to 0Photobacterium phosphoreum and QSAR analysis. J. Hazard. Mater. 279, 156–162. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2014.06.068

Junghans, M., Backhaus, T., Faust, M., Scholze, M., and Grimme, L. (2006). Application and validation of approaches for the predictive hazard assessment of realistic pesticide mixtures. Aquat. Toxicol. 76, 93–110. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2005.10.001

Kar, S., and Leszczynski, J. (2019). Exploration of computational approaches to predict the toxicity of chemical mixtures. Toxics 7:15. doi: 10.3390/toxics7010015

Kaweeteerawat, C., Chang, C. H., Roy, K. R., Liu, R., Li, R., Toso, D., et al. (2015). Cu Nanoparticles have different impacts in escherichia coli and lactobacillus brevis than their microsized and ionic analogues. Acs Nano 9, 7215–7225. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b02021

Khan, P. M., Kar, S., and Roy, K. (2020). “Ecotoxicological QSARs of mixtures,” in Ecotoxicological QSARs, ed K. Roy. (Humana Imprint Press), 437–475. doi: 10.1007/978-1-0716-0150-1_19

Kim, J., Kim, S., and Schaumann, G. E. (2014). Development of a partial least squares-based integrated addition model for predicting mixture toxicity. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess. 20, 174–200. doi: 10.1080/10807039.2012.754312

Konemann, H. (1981). Fish toxicity tests with mixtures of more than 2 chemicals - a proposal for a quantitative approach and experimental resultS. Toxicology 19, 229–238. doi: 10.1016/0300-483X(81)90132-3

Li, S., Anderson, T. A., Maul, J. D., Shrestha, B., Green, M. J., and Canas-Carrell, J. E. (2013a). Comparative studies of multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWNTs) and octadecyl (C18) as sorbents in passive sampling devices for biomimetic uptake of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) from soils. Sci. Total Environ. 461–462, 560–567. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.05.048

Li, S., Irin, F., Atore, F. O., Green, M. J., and Canas-Carrell, J. E. (2013b). Determination of multi-walled carbon nanotube bioaccumulation in earthworms measured by a microwave-based detection technique. Sci. Total Environ. 445–446, 9–13. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.12.037

Li, W., Tian, D., Lin, Z., Wang, D., and Yu, H. (2014). Study on the variation rules of the joint effects for multicomponent mixtures containing cyanogenic toxicants and aldehydes based on the transition state theory. J. Hazard. Mater. 267, 98–108. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2013.12.035

Limbach, L. K., Wick, P., Manser, P., Grass, R. N., Bruinink, A., and Stark, W. J. (2007). Exposure of engineered nanoparticles to human lung epithelial cells: influence of chemical composition and catalytic activity on oxidative stress. Environ. Sci. Technol. 41, 4158–4163. doi: 10.1021/es062629t

Lin, Z. F., Niu, X. J., Wu, C., Yin, K. D., and Cai, Z. P. (2005). Prediction of the toxicological joint effects between cyanogenic toxicants and aldehydes to Photobacterium phosphoreum. QSAR Comb. Sci. 24, 354–363. doi: 10.1002/qsar.200430882

Lin, Z. F., Yu, H. X., Wei, D. B., Wang, G. H., Feng, J. F., and Wang, L. S. (2002). Prediction of mixture toxicity with its total hydrophobicity. Chemosphere 46, 305–310. doi: 10.1016/S0045-6535(01)00083-2

Lin, Z. F., Zhong, P., Yin, K. D., Wang, L. S., and Yu, H. X. (2003). Quantification of joint effect for hydrogen bond and development of QSARs for predicting mixture toxicity. Chemosphere 52, 1199–1208. doi: 10.1016/S0045-6535(03)00329-1

Liu, S. S., Song, X. Q., Liu, H. L., Zhang, Y. H., and Zhang, J. (2009). Combined photobacterium toxicity of herbicide mixtures containing one insecticide. Chemosphere 75, 381–388. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2008.12.026

Liu, Y., Nie, Y., Wang, J., Wang, J., Wang, X., Chen, S., et al. (2018). Mechanisms involved in the impact of engineered nanomaterials on the joint toxicity with environmental pollutants. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 162, 92–102. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2018.06.079

Loewe, S., and Muischnek, H. (1926). Combinated effects I Announcement - Implements to the problem. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Exp. Pathol. Pharmakol. 114, 313–326. doi: 10.1007/BF01952257

Lütke Eversloh, C., Henning, N., Schulz, M., and Ternes, T. A. (2014). Electrochemical treatment of iopromide under conditions of reverse osmosis concentrates – Elucidation of the degradation pathway. Water Res. 48, 237–246. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2013.09.035

Ma, W., Han, Y., Xu, C., Han, H., Zhu, H., Li, K., et al. (2018). Biotoxicity assessment and toxicity mechanism on coal gasification wastewater (CGW): a comparative analysis of effluent from different treatment processes. Sci. Total Environ. 637–638, 1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.04.404

Ma, X. Y., Wang, X. C., Ngo, H. H., Guo, W., Wu, M. N., and Wang, N. (2014). Bioassay based luminescent bacteria: interferences, improvements, and applications. Sci. Total Environ. 468–469, 1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.08.028

Martín-de-Lucía, I., Campos-Mañas, M. C., Agüera, A., Rodea-Palomares, I., Pulido-Reyes, G., Leganés, F., et al. (2017). Reverse Trojan-horse effect decreased wastewater toxicity in the presence of inorganic nanoparticles. Environ. Sci. Nano. 4, 1273–1282. doi: 10.1039/C6EN00708B

Martinez, D. S. T., Alves, O. L., Barbieri, E., Martinez, D. S. T., Alves, O. L., and Barbieri, E. (2013). Carbon nanotubes enhanced the lead toxicity on the freshwater fish. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 429:012043. doi: 10.1088/1742-6596/429/1/012043

Matheson, I. B. C., and Lee, J. (1981). An efficient bacterial bioluminescence with reduced lumichromE. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 100, 532–536. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(81)80209-4

Meadows, S. L., Gennings, C., Carter, W. H., and Bae, D. S. (2002). Experimental designs for mixtures of chemicals along fixed ratio rays. Environ. Health Perspect. 110, 979–983. doi: 10.1289/ehp.02110s6979

Miyashiro, T., and Ruby, E. G. (2012). Shedding light on bioluminescence regulation in Vibrio fischeri. Mol. Microbiol. 84, 795–806. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08065.x

Mo, L. Y., Liu, J., Qin, L. T., Zeng, H.-H., and Liang, Y. P. (2017). Two-stage prediction on effects of mixtures containing phenolic compounds and heavy metals on vibrio qinghaiensis sp Q67. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 99, 17–22. doi: 10.1007/s00128-017-2099-1

Mo, L., Zhu, Z., Zhu, Y., Zeng, H., and Li, Y. (2014). Prediction and evaluation of the mixture toxicity of twelve phenols and ten anilines to the freshwater photobacterium vibrio qinghaiensis sp.-Q67. J. Chem. 9:728254. doi: 10.1155/2014/728254

Monosson, E. (2005). Chemical mixtures: considering the evolution of toxicology and chemical assessment. Environ. Health Perspect. 113, 383–390. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6987

Moore, S. A., and James, M. N. G. (1995). Structural refinement of the Nonfluorescent flavoprotein from photobacterium-leiognathi AT 1.60 angstrom resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 249, 195–214. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0289

Mori, I. C., Arias-Barreiro, C. R., Koutsaftis, A., Ogo, A., Kawano, T., Yoshizuka, K., et al. (2015). Toxicity of tetramethylammonium hydroxide to aquatic organisms and its synergistic action with potassium iodide. Chemosphere 120, 299–304. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.07.011

Mwense, M., Wang, X. Z., Buontempo, F. V., Horan, N., Young, A., and Osborn, D. (2004). Prediction of noninteractive mixture toxicity of organic compounds based on a fuzzy set method. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 44, 1763–1773. doi: 10.1021/ci0499368

Naasz, S., Altenburger, R., and Kuhnel, D. (2018). Environmental mixtures of nanomaterials and chemicals: the Trojan-horse phenomenon and its relevance for ecotoxicity. Sci. Total Environ. 635, 1170–1181. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.04.180

Nebout, P., Cagnon, B., Delpeux, S., Di Giusto, A., and Chedeville, O. (2016). Comparison of the efficiency of adsorption, ozonation, and ozone/activated carbon coupling for the removal of pharmaceuticals from water. J. Environ. Eng. 142:42. doi: 10.1061/(ASCE)EE.1943-7870.0001042

Nijvipakul, S., Ballou, D. P., and Chaiyen, P. (2010). Reduction kinetics of a flavin oxidoreductase LuxG from Photobacterium leiognathi (TH1): half-sites reactivity. Biochemistry 49, 9241–9248. doi: 10.1021/bi1009985

Nirmalakhandan, N., Arulgnanendran, V., Mohsin, M., Sun, B., and Cadena, F. (1994). Toxicity of mixtures of organic-chemicals to microorganisms. Water Res. 28, 543–551. doi: 10.1016/0043-1354(94)90005-1

O'Grady, E., A., and Wimpee, C. F. (2008). Mutations in the lux operon of natural dark mutants in the genus Vibrio. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 61–66. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01199-07

Oxender, D., and Fox, C. F. (1978). Molecular aspects of membrane transport. J. Supramol. Struct. 9, 120–167. doi: 10.1002/jss.400090505

Pino-Otín, M. R., Ballestero, D., Navarro, E., González-Coloma, A., Val, J., and Mainar, A. M. (2019). Ecotoxicity of a novel biopesticide from Artemisia absinthium on non-target aquatic organisms. Chemosphere 216, 131–146. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.09.071

Plackett, R. L., and Hewlett, P. S. (1952). Quantal responses to mixtures of poisons. J. R. Statist. Soc. B, 14, 141–63. doi: 10.2307/2983865