- 1Department of Biological Sciences, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, VA, United States

- 2Department of Biology, Tidewater Community College, Portsmouth, VA, United States

Mycobacteria are unique in many aspects of their biology. The development of genetic tools to identify genes critical for their growth by forward genetic analysis holds great promises to advance our understanding of their cellular, physiological and biochemical processes. Here we report the development of a novel transposon, MycoTetOP2, to aid the identification of such genes by direct transposon mutagenesis. This mariner-based transposon contains nested anhydrotetracycline (ATc)-inducible promoters to drive transcription outward from both of its ends. In addition, it includes the Escherichia coli R6Kγ origin to facilitate the identification of insertion sites. MycoTetOP2 was placed in a shuttle plasmid with a temperature-sensitive DNA replication origin in mycobacteria. This allows propagation of mycobacteria harboring the plasmid at a permissive temperature. The resulting population of cells can then be subjected to a temperature shift to select for transposon mutants. This transposon and its delivery system, once constructed, were tested in the fast-growing model Mycobacterium smegmatis and 13 mutants with ATc-dependent growth were isolated. The identification of the insertion sites in these mutants led to nine unique genetic loci with genes critical for essential processes in both M. smegmatis and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. These results demonstrate that MycoTetOP2 and its delivery vector provide valuable tools for the studies of mycobacteria by forward genetics.

Introduction

The genus Mycobacterium contains Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the causative agent of tuberculosis (TB). As a major human pathogen, M. tuberculosis infects one third of the world population, resulting in 10 million cases of TB and approximately 1.6 million deaths per year (Bloom et al., 2017). Yet, many aspects of the unique biology of mycobacteria remain to be understood. One approach to study mycobacteria is to decipher the functions of core genes essential for their growth, and these genes may prove valuable for the understanding of mycobacterial biology as well as the research and development of antimycobacterial agents (Borsari et al., 2017; Singh and Mizrahi, 2017; Campanico et al., 2018; Evans and Mizrahi, 2018). However, experimental identification and validation of such genes are laborious because their null mutations lead to lethality. Instead, essential genes in mycobacteria are usually inferred statistically from the rarity of their mutants following high density transposon mutagenesis and deep sequencing of mutant pools (Sassetti and Rubin, 2003; Sassetti et al., 2003; Griffin et al., 2011; DeJesus et al., 2013, 2017). This approach has identified numerous genes that are likely essential for the viability of mycobacteria. On the other hand, only limited number of these genes have been studied functionally. The significant road block here is that mutants in these genes are not readily available for follow-up studies. Rather, their investigation requires reverse genetics to construct conditional mutants using regulated promoters to deplete a gene product (Schnappinger and Ehrt, 2014; Leotta et al., 2015; Boldrin et al., 2018, 2019).

A tetracycline regulatable system has been successfully adapted for use in mycobacteria for the construction of conditional mutations (Ehrt et al., 2005; Ehrt and Schnappinger, 2006). This system controls the expression of the tetracycline efflux pump TetA in Escherichia coli and other non-mycobacterial species. It is induced by tetracycline and its analogs such as anhydrotetracycline (ATc) with reduced antimicrobial activity or toxicity (Ehrt and Schnappinger, 2006). The minimum genetic determinants required for this regulation include the TetR repressor and its operator tetO. Ehrt and Schnappinger (2006) modified the promoter of the rpsA gene from Mycobacterium smegmatis (Psmyc) by flanking its −35 sequence with two tetO operators. The resulting promoter, Psmyc1tetO, was demonstrated to be induced by ATc once a tetR gene is introduced and expressed in M. tuberculosis and M. smegmatis (Ehrt and Schnappinger, 2006). Conditional mutants of essential genes were constructed using this promoter for both M. smegmatis and Mycobacterium bovis (Chalut et al., 2006), confirming the utility of this promoter for the regulation of essential genes in mycobacteria.

The use of these regulated promoters in reverse genetics for the studies of essential genes is labor intensive, and there is a need for the development of tools for use in forward genetics. Herein are the results of the construction of a transposon with nested regulatable promoters and its introduction into M. smegmatis to generate conditional mutants by a forward genetic approach. The rationale was to place ATc-inducible and outward-facing promoters at both ends of and within a transposon. When the transposon inserts in either orientation near the 5′ end of an essential gene, the transposon mutant is expected to display inducer-dependent growth (Judson and Mekalanos, 2000). That is, such mutants may show normal or near normal growth with the inducer present while their mutant phenotypes can be analyzed in the absence of the inducer. In principle, this conditional phenotype can be used to screen for mutants to identify essential genes directly in a forward genetic screen. The new transposon, designated as MycoTetOP2 (Figure 1A), and its transposase gene were assembled and cloned into a delivery plasmid with a temperature-sensitive origin of replication in mycobacteria. A second plasmid, which integrates at a mycobacteriophage attachment site, was constructed to express TetR from a constitutive promoter. We tested MycoTetOP2 in a tetR-expressing M. smegmatis strain as a proof of principle. The results here validated the usefulness of MycoTetOP2 in the isolation of conditional mutants for the identification of essential genes in mycobacteria.

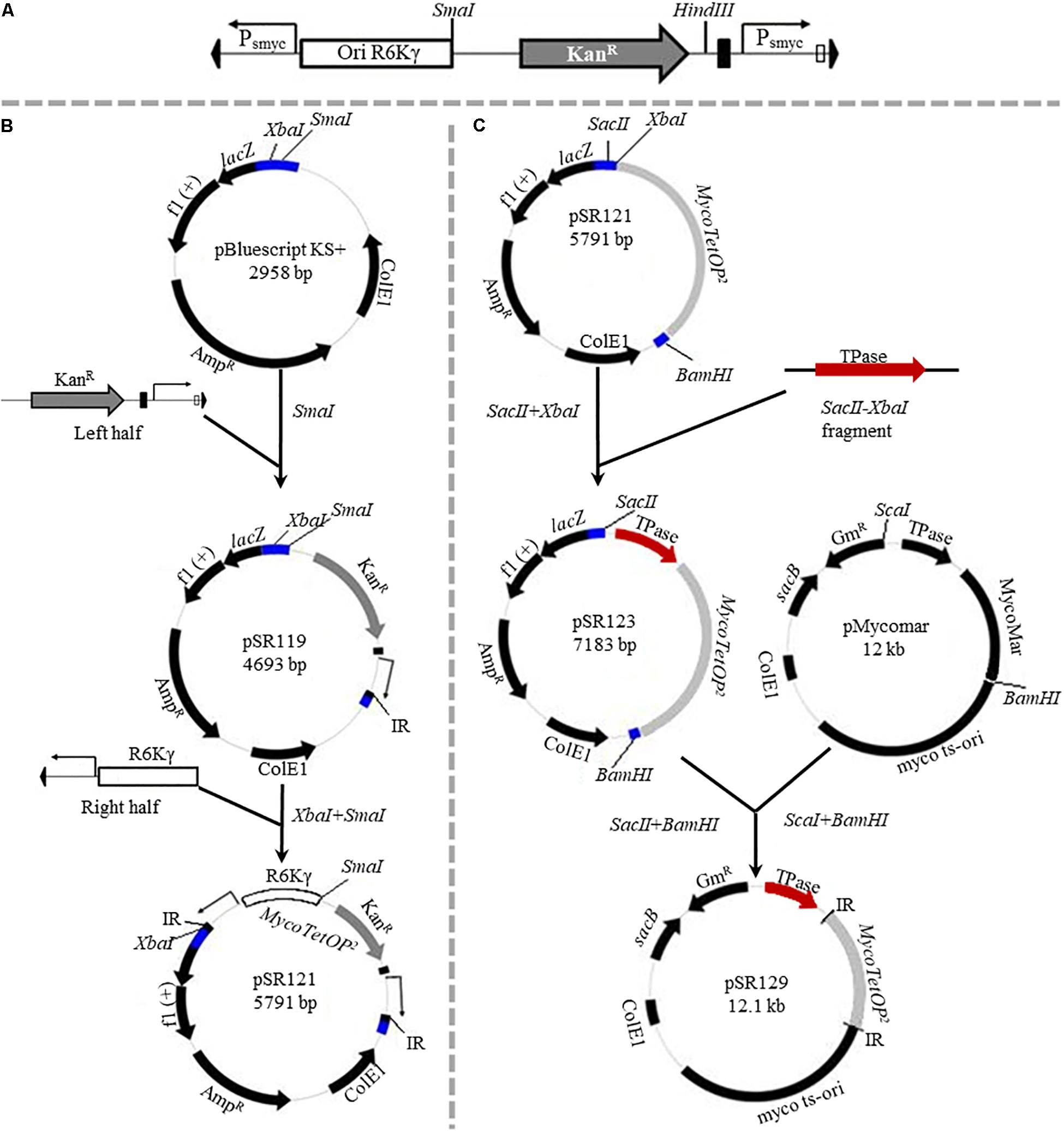

Figure 1. (A) Features of the MycoTetOP2 transposon. Drawn to approximate scale here is the MycoTetOP2 transposon of 2,851 base pairs. By design, it contains at its ends the two mariner IRs (block arrows in black), two Psmyc1tetO promoters (labeled Psmyc), the E. coli R6Kγ origin and the gene for KanR. The direction of transcription from each promoter is indicated by the arrow above. A transcriptional terminator (T4g32T), shown as a solid rectangle in black, is placed downstream of the KanR gene. The Mariner_SP_R3 primer neighbors the right IR as indicated by the open rectangle. The transposon has unique recognition sites for SmaI and HindIII but none for SacII. (B) Construction of MycoTetOP2. pSR119 and pSR120, containing the right and left halves of the transposon, respectively, were constructed as described in the text. The left half in a XbaI-SmaI fragment from pSR120 was cloned into similarly digested pSR119 to construct pSR121 with the complete MycoTetOP2. The region in blue is the multiple cloning site in pBluescript. (C) Construction of the delivery plasmid pSR129. A PCR fragment with the transposase (TPase) gene (in red) and pSR121 were both digested with SacII and XbaI and ligated to generate pSR123. The TPase-MycoTetOP2 cassette in pSR123 was liberated by SacII and BamHI digestion and cloned into pMycoMar digested by SacI and BamHI as described in the text. The sizes of individual plasmids in this figure are indicated but they are not drawn to scale relative to one another.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains and Growth Conditions

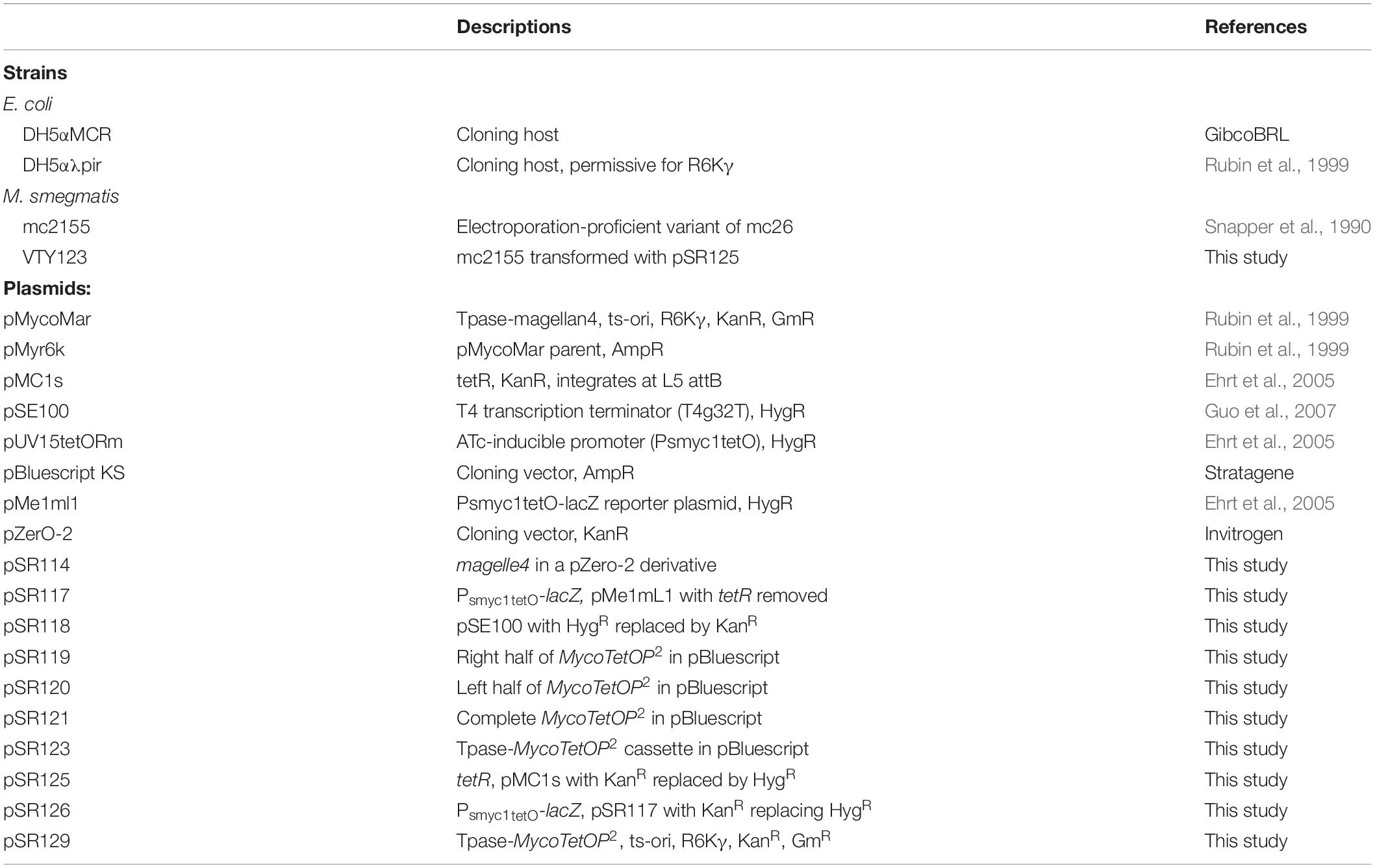

All strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. The Escherichia coli strains DH5αMCR (GibcoBRL) and DH5αλpir were grown and maintained using Luria-Bertani (LB) media at 37°C (Miller, 1972). M. smegmatis strains were grown and maintained in LB liquid media supplemented with 0.05% Tween 80 or on LB agar at 30, 37 or 39°C as specified. All plates contained 1.5% agar and all liquid cultures were grown on a rotary shaker at 250 rpm.

When appropriate, ampicillin (Amp), kanamycin (Kan) and hygromycin (Hyg) at 100 μg/ml were used for selection in E. coli. For selection in M. smegmatis, growth media were supplemented with Kan and Hyg at 50 μg/ml or gentamycin (Gm) at 15 μg/ml. Anhydrotetracycline (ATc) at 50 ng/ml was used for the induction of the TetR-tetO regulated promoters in M. smegmatis as previously reported (Ehrt et al., 2005).

Plasmid Construction

pSR114 was constructed as a PCR template for the amplification of the different elements in the mariner-based transposon megallan4 (Rubin et al., 1999). Its backbone was a pZerO-2 derivative with an intact multiple cloning site (Table 1). An XbaI-SpeI fragment containing megallan4 was obtained from pMyr6K (Rubin et al., 1999) and cloned into the XbaI and SpeI sites of this vector to generate pSR114.

pSR119, which contains the right half of MycoTetOP2 (Figure 1), was constructed as follows. A 1.2 kb fragment with the kanamycin resistance (KanR) gene was PCR amplified (Black et al., 2010) from pZerO-2 with primers pZerO_kanR_F (CCCGGGCCCGGTACCGAGGACACGTAGAAAGCCAGTCC GCA) and pZerO_kanR_R (GCTAAGCTTGGAACAACACTCA ACCCTATCGC). This fragment was digested with HindIII and cloned into EcoRV and HindIII digested pSE100 (Guo et al., 2007) to generate pSR118; this placed T4g32T, a T4 phage transcription terminator, downstream of the KanR gene. Next, the Psmyc1tetO promoter and a mariner IR were PCR amplified with the P_R1 (GGATCGTGCTCATTTCGGGC) and P_F1 (AATATTGGATCGTCGGCACC) primer pair and the M13F (CCCAGTCACGACGTTGTAAAACG) and 3_P_F2 (GCCCGAAATGAGCACGATCCTTCGACGCGTCAATTCGA GG) pair from pUV15tetORm and pSR114, respectively. These two fragments were joined to produce a Psmyc1tetO-mariner IR fragment by overlapping PCR (Black et al., 2010) because of primer complementarity. Lastly, the KanR-T4g32T cassette from pSR118 was PCR amplified using primers pZErO_kanR_F and T4g32_kanRterm_R (GGTGCCGACGATCCAATATTTAGCAATGCCTCCATGCG AT). This fragment was connected to the Psmyc1tetO-IR fragment by overlapping PCR. The resulting PCR product, which contains all four elements for the right half of the designed transposon (Figure 1A), was cloned into SmaI-digested pBluescript KS to construct pSR119 (Figure 1B).

pSR120 contains the left half of MycoTetOP2 (Figure 1A). Three DNA fragments containing a mariner IR, the Psmyc1tetO promoter and the R6Kγ replication origin were PCR amplified as follows. The IR and the R6Kγ fragments were PCR amplified from pSR114 using the M13R (AGCGGATAACAATTTCACACAGG) and 5_P_R1 (GCCCGA AATGAGCACGATCCTAATATGCATTTAATACTAG) primer pair and the P_F2 (GGTGCCGACGATCCAATATTTATATAGT ACCAACCTTCAA) and the P_R2 (TCCTCGGTACCG GGCCCGGGATCCCTTAATTAACCCCGAAAA) primer pair, respectively. The Psmyc1tetO fragment was amplified from pUV15tetORm (Table 1) using primers P_R1 and P_F1. A joint IR-Psmyc1tetO fragment was produced by overlapping PCR thanks to primer complementarity. This fragment was connected to the R6Kγ origin similarly by a second overlapping PCR. The resulting IR-Psmyc1tetO-R6Kγ fragment was digested with XbaI and SmaI and cloned into the same sites of pBluescript KS to generate the plasmid pSR120 (Table 1).

pSR121 contains the fully assembled transposon. For its construction, the left half of MycoTetOP2 in pSR120 was liberated by XbaI and SmaI digestion and cloned into pSR119 digested by the same enzymes. Next, the transposase (Tpase) gene from pMycoMar (Rubin et al., 1999) was PCR amplified with primers TPase_F (TCCCCGCGGCCGTCCAGTCTGGCAG) and TPase_R (GCTCTAGATTATTCAACATAGTTCCCT), digested with SacII and XbaI and cloned into pSR121 similarly digested. This gave rise to pSR123 which has the complete MycoTetOP2 transposon and its TPase gene (Tpase– MycoTetOP2) on a contiguous stretch of DNA in pBluescript with ampicillin resistance (AmpR) and the E. coli ColE1 replication origin (Figure 1C and Table 1).

pSR129 is an E. coli-mycobacterial shuttle plasmid with the TPase-MycoTetOP2 cassette (Figure 1C). For its construction, pSR123 was digested with SacII, blunt-ended with T4 DNA polymerase and followed by digestion with BamHI. The liberated MycoTetOP2-Tpase cassette was ligated with the backbone of pMycoMar (Rubin et al., 1999) obtained by digestion with ScaI, followed by blunt-ending with T4 DNA polymerase and digestion with BamHI. This produced the shuttle plasmid pSR129 with the mycobacterial temperature sensitive replication origin (ts-ori) (Rubin et al., 1999) as well as the E. coli ColE1 origin and gentamycin resistance (GmR).

The integrative plasmid pSR125 with the tetR gene was constructed from pMC1s (Guo et al., 2007) by replacing its KanR with Hyg resistance (HygR). First, the KanR gene in pMC1s was removed by NsiI and BspHI digestion with a T4 DNA polymerase treatment in between to repair the overhand from NsiI digestion. Next, a fragment carrying HygR was obtained by digestion of pSE100 (Guo et al., 2007) with SmaI and BspHI. Ligation of the linearized pMC1s and the above fragment resulted in pSR125 which carries the tetR gene and HygR.

A new reporter plasmid, pSR126, was constructed for the analysis of Psmyc1tetO regulation by TetR when it is expressed from pSR125 in M. smegmatis. tetR was removed from pMe1ml1 (Ehrt et al., 2005), which contains a Psmyc1tetO-lacZ fusion, by NotI digesting and re-ligation to generate pSR117. The HygR gene in pSR117 was removed by SacII digestion and the backbone was treated with T4 DNA polymerase. The KanR region from pZerO-2 was PCR amplified with primers pZerO_kanR_F and pZerO_kanR_R and ligated with the backbone of pSR117 to generate pSR126.

Transposon Mutagenesis of M. smegmatis

Mycobacterium smegmatis mc2155 was transformed by electroporation (Parish and Brown, 2008) with the tetR-expressing plasmid pSR125 to produce the strain VTY123 by HygR selection. Next, the MycoTetOP2 delivery shuttle plasmid pSR129 was transformed into VTY123 by GmR selection. After a 4-hour recovery at 30°C in LB broth, cells were spread on LB plates containing Gm and incubated at 30°C for 4 days. An estimated 88,000 transformants were harvested from the selective medium and suspended at approximately 1.2 × 107 cells per ml (cells/ml) in LB media with Tween 80 by passing through a syringe. This cell suspension was aliquoted and stored at −80°C in 15% glycerol as frozen stocks. To identify transposon mutants, approximately 1.2 × 104 cells from the frozen stocks were spread on an LB agar plate (100 mm × 15 mm) with Kan and ATc. These plates were incubated for 3 days at 39°C, the non-permissive temperature for the ts-ori replication origin (Guilhot et al., 1992; Pelicic et al., 1997). Colonies that formed on these plates were presumed to be transposon mutants without the delivery plasmid.

MycoTetOP2 Mutant Screening

Mutant colonies obtained in the presence of ATc at 39°C above were replica-plated onto medium with and without ATc and allowed to grow for 2 days at 39°C. Colonies that appeared to display ATc-dependent growth were patched in triplicates onto plates with and without ATc to verify the mutant phenotype after 2 days of incubation at 37°C besides testing for GmR for the loss of the plasmid. Mutants demonstrating reproducible ATc-dependent growth on patch plates were cultured in liquid media to exponential growth. These cells were diluted to 1 × 106, 1 × 105, and 1 × 104 cells/ml. 10 μl of each dilution was spotted on LB plates with and without ATc. Growth was examined and documented after 2 days incubation at 37°C.

Identification of Insertions in Transposon Mutants

Genomic DNA of M. smegmatis mutants (Parish and Brown, 2008) was digested with SacII (Figure 1A) and treated with DNA ligase. The ligation mix was transformed into DH5αλpir which allows the functioning of the R6Kγ origin of replication within the transposon. Recovered plasmids from the transformants were sequenced at the Genome Sequencing Center at Virginia Tech using primer Mariner_SP_R3 (TGAAGGGAACTATGTTGAAT) which recognizes the right end of MycoTetOP2 and read outwards from the transposon (Figure 1A). The sequences of the DNA flanking a MycoTetOP2 transposon insertion were analyzed using BLAST search against the genome sequences of M. smegmatis mc2155 at NCBI (Altschul et al., 1990; Mount, 2007) to identify the transposon insertions site. ORFs in the neighborhood of an insertion were searched against the complete genome sequence of M. tuberculosis H37Rv using BLAST tools (Altschul et al., 1990; Mount, 2007) and analyzed additionally using the MycoBrowser Portal (Kapopoulou et al., 2011).

Results

Design and Construction of MycoTetOP2 and Its Delivery Plasmid

MycoTetOP2 (Figure 1A), a mariner-based transposon, was designed for mutagenesis of essential genes in mycobacteria. The mariner element was chosen due to its relaxed site specificity for transposition and functionality in mycobacteria (Rubin et al., 1999). The starting template was magellan4, a mariner derivative that has been used successfully in mycobacteria (Rubin et al., 1999). magellan4 contains the E. coli R6Kγ origin of replication and KanR. One feature of the new transposon was the addition of the strong and inducible mycobacterial promoter Psmyc1tetO nested inside the transposon and immediately adjacent to both IRs. Psmyc1tetO is an engineered mycobacterial promoter that is repressed by TetR-tetO interaction and induced by ATc which binds and inactivates the TetR repressor (Ehrt et al., 2005). The two Psmyc1tetO promoters (for the namesake of TetOP2) are positioned to drive transcription outward from MycoTetOP2 in both directions once it is transposed onto the mycobacterial chromosome. Another feature of MycoTetOP2 was the introduction of the transcription terminator from gene 32 of phage T4 (T4g32T) (Kaps et al., 2001; Guo et al., 2007) downstream of the KanR gene to prevent transcriptional read-through (Figure 1A). In principle, if MycoTetOP2 inserts in either orientation near the 5′ end of an essential gene, the transposon mutant may display ATc-dependent growth.

For the construction of MycoTetOP2, its left and right halves as defined by a SmaI site (Figure 1A) were assembled separately (see section “Materials and Methods”). The left half of MycoTetOP2 with the R6Kγ origin (Figure 1A) was assembled from three PCR fragments by two rounds of overlapping PCR and cloned into the E. coli vector pBluescript to generate pSR120 (Table 1). The right half of MycoTetOP2, assembled through a series of PCR reactions in combination with molecular cloning, was placed into pBluescript to construct pSR119 (Figure 1B). The last step was to join the left with the right at the SmaI site in pSR119 to assemble the full MycoTetOP2 transposon in pSR121 (Figure 1B).

pSR129 (Figure 1C), an E. coli-mycobacteria shuttle plasmid, was constructed for the delivery of MycoTetOP2 into mycobacteria. The mariner transposase (TPase) (Rubin et al., 1999) was first cloned next to the transposon to produce a Tpase-MycoTetOP2 cassette in the E. coli plasmid pSR123 (Figure 1C). Transposon mutagenesis of M. smegmatis with this plasmid by direct transformation was possible but inefficient (unpublished observations), likely because of the dual requirements for transformation AND transposition. The Tpase-MycoTetOP2 cassette was therefore combined with the backbone of pMycoMar which has ts-ori, a temperature sensitive mycobacterial replication origin to construct pSR129 (Guilhot et al., 1992). This shuttle plasmid can be transformed into mycobacteria by GmR. Transformants can be propagated at the permissive temperature of 30°C and transposition can then be selected by KanR at the non-permissive temperature of 39°C.

Identification of M. smegmatis Transposon Mutants With ATc-Dependent Growth

The use of MycoTetOP2 to generate conditional transposon mutants requires a strain that expresses TetR to regulate the Psmyc1tetO promoters. Available was the plasmid pMC1s which can integrate at the phage L5 attachment site in mycobacteria to express TetR constitutively (Guo et al., 2007). However, this plasmid carries the same KanR selection as the MycoTetOP2 transposon. The KanR marker on pMC1s was thus replaced with a HygR gene from pSE100 (Guo et al., 2007). The resulting plasmid, pSR125, was introduced by electroporation into the M. smegmatis strain mc2155 (Snapper et al., 1990) to construct the TetR-expressing strain VTY123. When VTY123 was transformed with the Psmyc1tetO-lacZ reporter plasmid pSR126, the transformants exhibited ATc-inducible expression of β-galactosidase (data not shown) in line with previous observations (Ehrt et al., 2005).

The MycoTetOP2 delivery plasmid pSR129 (Figure 1C) was transformed into the TetR-expressing M. smegmatis strain VTY123 by GmR selection on plates at 30°C. After 4 days of incubation, an estimated 88,000 colonies were harvested. These cells were suspended and aliquoted for storage at −80°C for late use in mutant screening without further growth. This was intended to minimize the over representation of any cell with an early transposition event prior to screens for transposon mutants.

Next, a genetic screen was carried out to isolate M. smegmatis transposon mutants with ATc-dependent growth. Cells from frozen stocks above were plated to select for KanR colonies at 39°C (Guilhot et al., 1992) in the presence of ATc and ∼5,200 KanR colonies were screened by replica plating. 13 mutants, designated VTY201-213, were found to have ATc-dependent growth in primary screens. The conditional growth phenotype of these mutants was confirmed by patching in triplicates on plates with and without ATc. These mutants were all found to be sensitive to gentamycin because its resistance is carried by the delivery plasmid instead of the transposon itself.

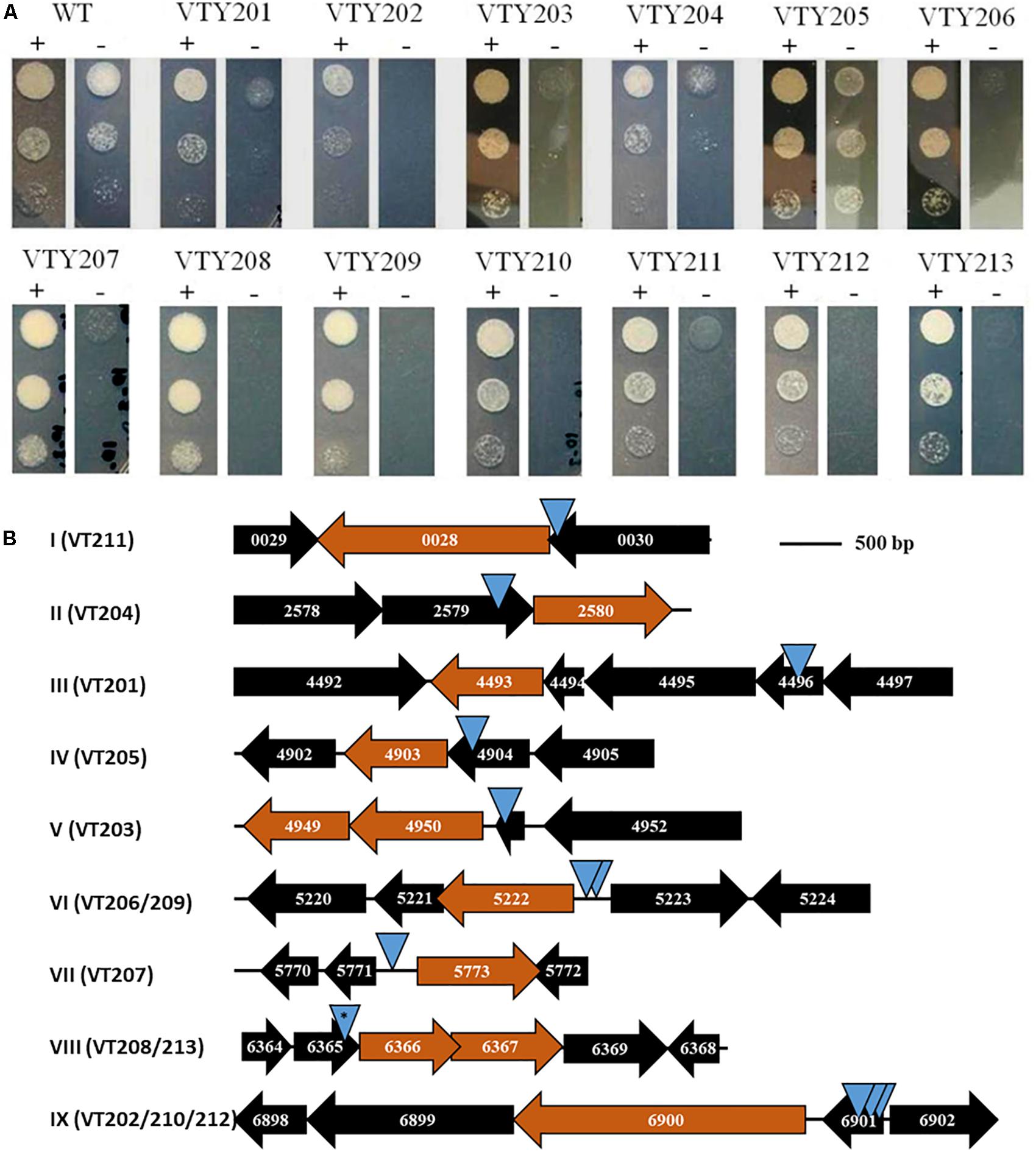

The growth of the 13 mutants was further examined on agar plates with and without ATc by serial dilutions (Figure 2A). As expected, the wild-type parental strain (VTY123) showed no difference in growth with and without ATc. In contrast, the 13 mutants all showed various degrees of ATc-dependent growth. Based on their growth phenotypes in this test, these mutants were divided into three groups. VTY205 displayed only a weak growth deficiency without ATc whereas VTY201 and VTY204 showed a moderate ATc-dependency (Figure 2A). The remaining 10 mutants belong to the last group with the strongest ATc-dependent growth. That is, they showed no or little growth in the absence of ATc but grew similarly as the wild type in the presence of ATc in this assay. These results indicated that the MycoTetOP2 transposon fulfilled its designed purpose for the isolation of conditional mutants of mycobacteria for the identification of possible essential genes by direct transposon mutagenesis.

Figure 2. (A) ATc-dependent growth of mutants. The 13 mutants and their isogenic wild-type (WT) parent VT123 were examined for growth with (+) and without (–) ATc. 10 μl of cell suspension at 1 × 106, 1 × 105, and 1 × 104 cells/ml of an indicated strain were spotted on plates shown here from top to bottom. Growth was examined after 2 days of incubation at 37°C. (B) Loci identified by MycoTetOP2 insertions. Drawn to approximate scale are the ORFs and their MSMEG numbers at the nine genetic loci (I–XI) identified by M. smegmatis conditional mutants. The candidate essential genes at each locus is colored in maroon. Each blue triangle represents a unique transposon insertion. Two identical insertions at locus VIII (∗) were found in two separate mutants (see text for details).

Identification of Essential Genes Near MycoTetOP2 Insertions in Conditional Mutants

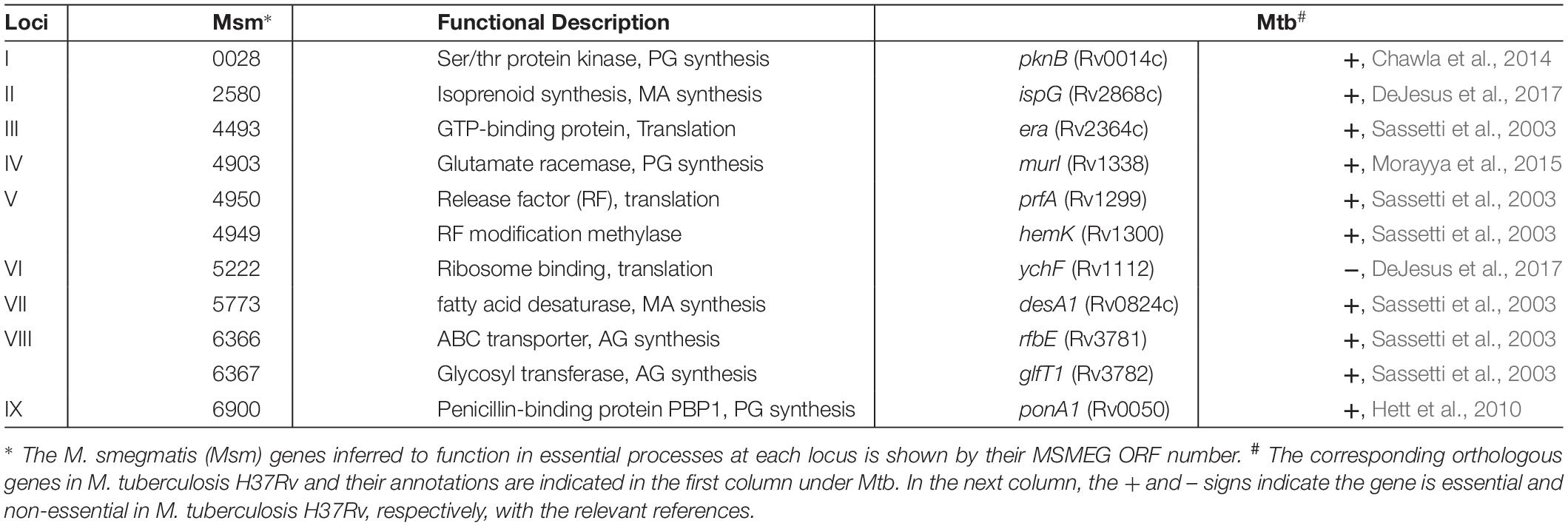

The transposon and its flanking DNA from each mutant were cloned and sequenced to identify the site of MycoTetOP2 insertion. Plasmids from different colonies on the transformation plate for each mutant were isolated and examined by multiple restriction digestions. For each of the 13 mutants, the same digestion pattern was observed for these plasmids (data not shown), indicating that there is likely only one single transposon insertion in each mutant. Sequences of mycobacterial DNA flanking MycoTetOP2 insertions were used in BLAST searches against the genome sequence of M. smegmatis mc2155 to identify the transposon insertion sites. This led to nine distinct genetic loci, designated I through IX, according to their genome coordinates (Figure 2B). The three mutants with moderate (VTY204 and VTY201) and weak (VTY205) ATc-dependent growth led to loci II, III, and IV, respectively. The 10 mutants with strong ATc-dependent growth identified the remaining six loci, I and V-IX. Among these, loci VI and IX were identified by two (VTY206 and VTY209) and three (VTY202, VTY210, and VTY212) independent insertions, respectively. Locus VIII was identified by two identical insertions in VTY208 and VTY213, possibly due to the propagation of the same insertion mutant during the screening process. The other three loci, I, V and VII were identified each by single insertions in VTY211, VTY203 and VTY207, respectively.

The ATc-dependent growth of these mutants suggests that one or more genes adjacent to their transposon insertions are possibly essential for M. smegmatis growth. To identify these putative essential genes, the genomic contexts of the nine genetic loci were analyzed in relations to their respective insertions (Figure 2B). The putative essential genes at these loci may be divided into three groups with three members each based on their known or putative functions (Table 2). Genes at loci II, VII, and VIII form the first group with functions in the biosynthesis of mycolic acids (MAs) or arabinogalactans (AGs) which form the outer layers of mycobacterial cell wall (Jankute et al., 2015; Bhat et al., 2017). MSMEG_2580 at locus II (Figure 2B) encodes GcpE/IspG, an enzyme in the synthesis of isoprenoid, a key precursor for cellular components including those required for cell wall biosynthesis (Brown et al., 2010; Artsatbanov et al., 2012). MSMEG_5773 (locus VII) encodes DesA1, which is essential in M. smegmatis with the proposed function of introducing double bonds in MAs (Singh et al., 2016). MSMEG_6366 and MSMEG_6367 at locus VIII, encoding an RfbE-like ABC transporter and the GlfT1 glycosyl transferase, respectively, are both required for AG biosynthesis (Belanova et al., 2008; Dianiskova et al., 2011). The second group, which include loci I, IV, and IX, identified genes implicated in the biosynthesis of peptidoglycan (PG) which form the inner layer of mycobacterial cell wall. At locus I, MSMEG_0028, which encodes the Ser/Thr protein kinase PknB implicated in PG biosynthesis (Chawla et al., 2014; Turapov et al., 2018), are known to be essential in M. smegmatis and M. tuberculosis (Fernandez et al., 2006; Chawla et al., 2014). At locus IV, MSMEG_4903 encodes the MurI glutamate racemase, an enzyme essential for PG biosynthesis (Li et al., 2014). At locus IX, MSMEG_6900 or ponA encode PBP1, a bifunctional penicillin-binding protein with both transglycosylase and transpeptidase activities essential for PG biosynthesis in M. smegmatis (Hett et al., 2010; Kieser et al., 2015). The last group included loci III, V, and VI and they harbor genes critical for ribosomal functions and translation. MSMEG_4493 (locus III) encodes the rRNA-binding GTPase Era known to be essential for bacterial viability (Ji, 2016). The insertion at locus V occurred in MSMEG_4951, which encodes the ribosomal protein L31. MSMEG_4950 and MSMEG_4949 immediately downstream encodes the protein chain release factor PrfA (Rodnina, 2018) and its modifying enzyme HemK (Yang et al., 2004), respectively. The insertions at locus VI were adjacent to MSMEG_5222, which encodes YchF, a universally conserved GTPase with possible involvement in translation (Becker et al., 2012; Rosler et al., 2015). In summary, the candidate essential genes identified by the 13 M. smegmatis mutants are known or suspected to have function in MA, AG and PG biosynthesis as well as the information flow from mRNA to protein. These results indicate that the MycoTetOP2 transposon and its delivery vehicle constructed here are useful tools for the investigation of mycobacteria by forward genetics.

Discussion

Here we describe the design, construction and use of a novel transposon, MycoTetOP2, for the identification of essential genes in M. smegmatis by transposon mutagenesis for the isolation of conditional mutants. We screened ∼5,200 MycoTetOP2 transposon insertions and identified 13 mutants with ATc-dependent growth phenotypes. These mutants led to nine genetic loci, each with candidate genes with functions in the essential processes of translation and the synthesis of mycobacterial cell wall (Figure 2 and Table 2). In principle, this transposon can be used in other mycobacteria including M. tuberculosis because both the mariner transposon and TetR-tetO regulatory systems have been demonstrated to function in other mycobacterial species (Rubin et al., 1999; Sassetti et al., 2001; Ehrt et al., 2005; Ehrt and Schnappinger, 2006; Guo et al., 2007).

Searches with M. smegmatis candidate genes at the nine loci against the genome sequence of M. tuberculosis indicated that they are all conserved in the TB strain (Table 2). All their M. tuberculosis counterparts, except YchF, are essential for viability of M. tuberculosis (Table 2). Some of these genes are known targets for antimycobacterial and/or antimicrobial agents. PknB, the ser/thr protein kinase critical for PG biosynthesis (Chawla et al., 2014; Turapov et al., 2018), has been explored as a target for antimycobacterial agents (Mori et al., 2019), for example. MurI (locus IV) is a glutamate racemase essential for PG biosynthesis in both M. tuberculosis and M. smegmatis (Li et al., 2014; Morayya et al., 2015) and it is a known target of anti-TB chemotherapeutics (Prosser et al., 2016; Pawar et al., 2019). PonA1 or PBP1 (locus IX) is a bifunctional enzyme with transglycosylase and transpeptidase activities required for PG synthesis and crosslinking (Barreteau et al., 2008; Vollmer and Bertsche, 2008; Hett et al., 2010; Kieser et al., 2015). It binds and is inhibited by β-lactams, the best known and the most important class of antibiotics in human history. There is renewed interest in PG biosynthesis as a target for anti-TB therapies as multidrug resistance becomes a serious threat (Catalao et al., 2019). In addition, GcpE/IspG (locus II) constitutes part of the methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathway which is considered promising targets for the development of antimycobacterial and antiparasitic agents (He et al., 2018; Wang and Dowd, 2018). The findings of these critical genes in this study illustrate the usefulness of our newly constructed transposon in the studies of mycobacteria.

Forti et al. (2011) constructed and applied a marine-based transposon with an outfacing promoter to identify M. tuberculosis conditional mutants. Their efforts produced 14 M. tuberculosis mutants, leading to the identification of 10 genes. The attempts to use their transposons in the fast-growing model mycobacterium M. smegmatis was unsuccessful and not further pursued. The design and construction of MycoTetOP2 occurred independently (Riggs, 2011) from the work by Forti et al. (2011), and there are a few differences in the designs and delivery of our transposon from theirs. First, MycoTetOP2 here uses the TetR-tetO regulated promoters instead of the pip/pptr system in theirs. Second, while their transposon has one outfacing promotor, ours has promoters at both ends which may improve the efficiency for isolation of conditional mutants. Third, our transposon contains the E. coli R6K replication origin which facilitates the cloning and identification of MycoTetOP2 insertions. Forth, we introduced a transcription terminator after the KanR gene to prevent possible read-throughs from its promoter and minimize unintended expression of mycobacterial genes in the absence of induction. Last but least, the delivery systems are different. Forti’s transposons were transduced into mycobacteria (Forti et al., 2011) while MycoTetOP2 here can be delivered by transformation using an E. coli-mycobacterial shuttle plasmid. The key difference here is that the temperature sensitive ts-ori origin in the MycoTetOP2 delivery plasmid separates the selection for transposition from the acquisition of cells with the transposon-Tpase DNA cassette. This may be the main reason why MycoTetOP2 succeeded in M. smegmatis while theirs did not. This is because in our case, cells with the transposon-Tpase DNA cassette can be propagated before the selection for transposition. It is noted that the genes identified by Forti et al. (2011) and those here have no overlaps. We suggest that it is advantageous to have different and new regulatory schemes (Schnappinger and Ehrt, 2014; Leotta et al., 2015; Boldrin et al., 2018, 2019) for the design of transposons for the investigation of mycobacterial biology in the future.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/search/all/?term=NC_008596.

Author Contributions

SR-S and ZY conceived the project. SR-S performed the experiments with technical guidance from JF and ZY. All authors wrote the manuscript.

Funding

SR-S received support from the Department of Biological Sciences at Virginia Tech. ZY received funding from National Institutes of Health grant GM071601 and National Science Foundation grant MCB1919455. We acknowledge Virginia Tech Open Access Subvention Fund for partial defrayment of the cost for the publication of this article.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Prof. Eric Rubin at Harvard University and Profs. Dirk Schnappinger and Sabine Ehrt at Cornell University for generously providing plasmids used in this study. We thank Dr. Wesley Black for his advice and assistance.

References

Altschul, S. F., Gish, W., Miller, W., Myers, E. W., and Lipman, D. J. (1990). Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215, 403–410. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1990.9999

Artsatbanov, V. Y., Vostroknutova, G. N., Shleeva, M. O., Goncharenko, A. V., Zinin, A. I., Ostrovsky, D. N., et al. (2012). Influence of oxidative and nitrosative stress on accumulation of diphosphate intermediates of the non-mevalonate pathway of isoprenoid biosynthesis in corynebacteria and mycobacteria. Biochemistry 77, 362–371. doi: 10.1134/S0006297912040074

Barreteau, H., Kovac, A., Boniface, A., Sova, M., Gobec, S., and Blanot, D. (2008). Cytoplasmic steps of peptidoglycan biosynthesis. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 32, 168–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00104.x

Becker, M., Gzyl, K. E., Altamirano, A. M., Vuong, A., Urban, K., and Wieden, H. J. (2012). The 70S ribosome modulates the ATPase activity of Escherichia coli YchF. RNA Biol. 9, 1288–1301. doi: 10.4161/rna.22131

Belanova, M., Dianiskova, P., Brennan, P. J., Completo, G. C., Rose, N. L., Lowary, T. L., et al. (2008). Galactosyl transferases in mycobacterial cell wall synthesis. J. Bacteriol. 190, 1141–1145. doi: 10.1128/jb.01326-07

Bhat, Z. S., Rather, M. A., Maqbool, M., Lah, H. U., Yousuf, S. K., and Ahmad, Z. (2017). Cell wall: a versatile fountain of drug targets in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 95, 1520–1534. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.09.036

Black, W. P., Julien, B., Rodriguez, E., and Yang, Z. (2010). “Genetic manipulation of myxobacteria,” in Manual of Industrial Microbiology and Biotechnology, eds R. H. Baltz, J. E. Davies, and A. L. Demain, (Washington, DC: ASM Press).

Bloom, B. R., Atun, R., Cohen, T., Dye, C., Fraser, H., Gomez, G. B., et al. (2017). “Tuberculosis,” in Major Infectious Diseases, eds K. K. Holmes, S. Bertozzi, B. R. Bloom, and P. Jha, (Washington, DC: World Bank).

Boldrin, F., Anoosheh, S., Serafini, A., Cioetto Mazzabo, L., Palu, G., Provvedi, R., et al. (2019). Improving the stability of the TetR/Pip-OFF mycobacterial repressible promoter system. Sci. Rep. 9:5783. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-42319-2

Boldrin, F., Degiacomi, G., Serafini, A., Kolly, G. S., Ventura, M., Sala, C., et al. (2018). Promoter mutagenesis for fine-tuning expression of essential genes in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Microb. Biotechnol. 11, 238–247. doi: 10.1111/1751-7915.12875

Borsari, C., Ferrari, S., Venturelli, A., and Costi, M. P. (2017). Target-based approaches for the discovery of new antimycobacterial drugs. Drug Discov. Today 22, 576–584. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2016.11.014

Brown, A. C., Eberl, M., Crick, D. C., Jomaa, H., and Parish, T. (2010). The nonmevalonate pathway of isoprenoid biosynthesis in Mycobacterium tuberculosis is essential and transcriptionally regulated by Dxs. J. Bacteriol. 192, 2424–2433. doi: 10.1128/JB.01402-09

Campanico, A., Moreira, R., and Lopes, F. (2018). Drug discovery in tuberculosis. new drug targets and antimycobacterial agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 150, 525–545. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.03.020

Catalao, M. J., Filipe, S. R., and Pimentel, M. (2019). Revisiting anti-tuberculosis therapeutic strategies that target the peptidoglycan structure and synthesis. Front. Microbiol. 10:190. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00190

Chalut, C., Botella, L., De Sousa-D’auria, C., Houssin, C., and Guilhot, C. (2006). The nonredundant roles of two 4′-phosphopantetheinyl transferases in vital processes of Mycobacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 8511–8516. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511129103

Chawla, Y., Upadhyay, S., Khan, S., Nagarajan, S. N., Forti, F., and Nandicoori, V. K. (2014). Protein kinase B (PknB) of Mycobacterium tuberculosis is essential for growth of the pathogen in vitro as well as for survival within the host. J. Bio. Chem. 289, 13858–13875. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.563536

DeJesus, M. A., Gerrick, E. R., Xu, W., Park, S. W., Long, J. E., Boutte, C. C., et al. (2017). Comprehensive essentiality analysis of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis genome via saturating transposon mutagenesis. mBio 8:e2133-16. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02133-16

DeJesus, M. A., Zhang, Y. J., Sassetti, C. M., Rubin, E. J., Sacchettini, J. C., and Ioerger, T. R. (2013). Bayesian analysis of gene essentiality based on sequencing of transposon insertion libraries. Bioinformatics 29, 695–703. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt043

Dianiskova, P., Kordulakova, J., Skovierova, H., Kaur, D., Jackson, M., Brennan, P. J., et al. (2011). Investigation of ABC transporter from mycobacterial arabinogalactan biosynthetic cluster. Gen. Physiol. Biophys. 30, 239–250. doi: 10.4149/gpb_2011_03_239

Ehrt, S., Guo, X. V., Hickey, C. M., Ryou, M., Monteleone, M., Riley, L. W., et al. (2005). Controlling gene expression in mycobacteria with anhydrotetracycline and Tet repressor. Nucleic Acids Res. 33:e21. doi: 10.1093/nar/gni013

Ehrt, S., and Schnappinger, D. (2006). Controlling gene expression in Mycobacteria. Future Microbiol. 1, 177–184. doi: 10.2217/17460913.1.2.177

Evans, J. C., and Mizrahi, V. (2018). Priming the tuberculosis drug pipeline: new antimycobacterial targets and agents. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 45, 39–46. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2018.02.006

Fernandez, P., Saint-Joanis, B., Barilone, N., Jackson, M., Gicquel, B., Cole, S. T., et al. (2006). The Ser/Thr protein kinase PknB is essential for sustaining mycobacterial growth. J. Bacteriol. 188, 7778–7784. doi: 10.1128/jb.00963-06

Forti, F., Mauri, V., Deho, G., and Ghisotti, D. (2011). Isolation of conditional expression mutants in Mycobacterium tuberculosis by transposon mutagenesis. Tuberculosis 91, 569–578. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2011.07.004

Griffin, J. E., Gawronski, J. D., Dejesus, M. A., Ioerger, T. R., Akerley, B. J., and Sassetti, C. M. (2011). High-resolution phenotypic profiling defines genes essential for mycobacterial growth and cholesterol catabolism. PLoS Pathog. 7:e1002251. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002251

Guilhot, C., Gicquel, B., and Martin, C. (1992). Temperature-sensitive mutants of the Mycobacterium Plasmid Pal5000. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 98, 181–186. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(92)90152-e

Guo, X. V., Monteleone, M., Klotzsche, M., Kamionka, A., Hillen, W., Braunstein, M., et al. (2007). Silencing Mycobacterium smegmatis by using tetracycline repressors. J. Bacteriol. 189, 4614–4623. doi: 10.1128/jb.00216-07

He, L., He, P., Luo, X., Li, M., Yu, L., Guo, J., et al. (2018). The MEP pathway in babesia orientalis apicoplast, a potential target for anti-babesiosis drug development. Parasit. Vectors 11:452. doi: 10.1186/s13071-018-3038-7

Hett, E. C., Chao, M. C., and Rubin, E. J. (2010). Interaction and modulation of two antagonistic cell wall enzymes of mycobacteria. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1001020. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001020

Jankute, M., Cox, J. A., Harrison, J., and Besra, G. S. (2015). Assembly of the mycobacterial cell wall. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 69, 405–423. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-091014-104121

Ji, X. (2016). Structural insights into cell cycle control by essential GTPase Era. Postepy Biochem. 62, 335–342.

Judson, N., and Mekalanos, J. J. (2000). TnAraOut, a transposon-based approach to identify and characterize essential bacterial genes. Nat. Biotechnol. 18, 740–745. doi: 10.1038/77305

Kapopoulou, A., Lew, J. M., and Cole, S. T. (2011). The mycobrowser portal: a comprehensive and manually annotated resource for mycobacterial genomes. Tuberculosis 91, 8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2010.09.006

Kaps, I., Ehrt, S., Seeber, S., Schnappinger, D., Martin, C., Riley, L. W., et al. (2001). Energy transfer between fluorescent proteins using a co-expression system in Mycobacterium smegmatis. Gene 278, 115–124. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(01)00712-0

Kieser, K. J., Boutte, C. C., Kester, J. C., Baer, C. E., Barczak, A. K., Meniche, X., et al. (2015). Phosphorylation of the peptidoglycan synthase PonA1 governs the rate of polar elongation in Mycobacteria. PLoS Pathog. 11:e1005010. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005010

Leotta, L., Spratt, J. M., Kong, C. U., and Triccas, J. A. (2015). An inducible expression system for high-level expression of recombinant proteins in slow growing Mycobacteria. Plasmid 81, 27–31. doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2015.05.002

Li, Y., Mortuza, R., Milligan, D. L., Tran, S. L., Strych, U., Cook, G. M., et al. (2014). Investigation of the essentiality of glutamate racemase in Mycobacterium smegmatis. J. Bacteriol. 196, 4239–4244. doi: 10.1128/JB.02090-14

Miller, J. H. (1972). Experiments in Molecular Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory.

Morayya, S., Awasthy, D., Yadav, R., Ambady, A., and Sharma, U. (2015). Revisiting the essentiality of glutamate racemase in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Gene 555, 269–276. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2014.11.017

Mori, M., Sammartino, J. C., Costantino, L., Gelain, A., Meneghetti, F., Villa, S., et al. (2019). An overview on the potential antimycobacterial agents targeting serine/threonine protein kinases from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 19, 646–661. doi: 10.2174/1568026619666190227182701

Mount, D. W. (2007). Using the basic local alignment search tool (BLAST). CSH Protoc. 2007:dbto17. doi: 10.1101/pdb.top17

Pawar, A., Jha, P., Konwar, C., Chaudhry, U., Chopra, M., and Saluja, D. (2019). Ethambutol targets the glutamate racemase of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, an enzyme involved in peptidoglycan biosynthesis. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 103, 843–851. doi: 10.1007/s00253-018-9518-z

Pelicic, V., Jackson, M., Reyrat, J. M., Jacobs, W. R.Jr., Gicquel, B., and Guilhot, C. (1997). Efficient allelic exchange and transposon mutagenesis in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 10955–10960. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.20.10955

Prosser, G. A., Rodenburg, A., Khoury, H., De Chiara, C., Howell, S., Snijders, A. P., et al. (2016). Glutamate racemase is the primary target of beta-Chloro-D-Alanine in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 60, 6091–6099. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01249-16

Riggs, S. D. (2011). Construction and Use of a Transposon for Identification of Essential Genes in Mycobacteria. Ph.D. thesis, Masters Masters, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, VA.

Rosler, K. S., Mercier, E., Andrews, I. C., and Wieden, H. J. (2015). Histidine 114 Is critical for ATP Hydrolysis by the Universally Conserved ATPase YchF. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 18650–18661. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.598227

Rubin, E. J., Akerley, B. J., Novik, V. N., Lampe, D. J., Husson, R. N., and Mekalanos, J. J. (1999). In vivo transposition of mariner-based elements in enteric bacteria and mycobacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 1645–1650. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.4.1645

Sassetti, C. M., Boyd, D. H., and Rubin, E. J. (2001). Comprehensive identification of conditionally essential genes in mycobacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 12712–12717. doi: 10.1073/pnas.231275498

Sassetti, C. M., Boyd, D. H., and Rubin, E. J. (2003). Genes required for mycobacterial growth defined by high density mutagenesis. Mol. Microbiol. 48, 77–84. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03425.x

Sassetti, C. M., and Rubin, E. J. (2003). Genetic requirements for mycobacterial survival during infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 12989–12994. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2134250100

Schnappinger, D., and Ehrt, S. (2014). Regulated expression systems for Mycobacteria and their applications. Microbiol. Spectr. 2, MGM2–MGM0018. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.MGM2-0018-2013

Singh, A., Varela, C., Bhatt, K., Veerapen, N., Lee, O. Y., Wu, H. H., et al. (2016). Identification of a desaturase involved in mycolic acid biosynthesis in Mycobacterium smegmatis. PLoS One 11:e0164253. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0164253

Singh, V., and Mizrahi, V. (2017). Identification and validation of novel drug targets in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Drug Discov. Today 22, 503–509. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2016.09.010

Snapper, S. B., Melton, R. E., Mustafa, S., Kieser, T., and Jacobs, W. R.Jr. (1990). Isolation and characterization of efficient plasmid transformation mutants of Mycobacterium smegmatis. Mol. Microbiol. 4, 1911–1919. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb02040.x

Turapov, O., Forti, F., Kadhim, B., Ghisotti, D., Sassine, J., Straatman-Iwanowska, A., et al. (2018). Two Faces of CwlM, an Essential PknB substrate, in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Cell Rep. 25:e55. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.09.004

Vollmer, W., and Bertsche, U. (2008). Murein (peptidoglycan) structure, architecture and biosynthesis in Escherichia coli. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1778, 1714–1734. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.06.007

Wang, X., and Dowd, C. S. (2018). The Methylerythritol Phosphate pathway: promising drug targets in the fight against tuberculosis. ACS Infect. Dis. 4, 278–290. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.7b00176

Keywords: transposon, mycobacterium, essential genes, conditional mutants, TetR-tetO

Citation: Riggs-Shute SD, Falkinham JO and Yang Z (2020) Construction and Use of Transposon MycoTetOP2 for Isolation of Conditional Mycobacteria Mutants. Front. Microbiol. 10:3091. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.03091

Received: 18 November 2019; Accepted: 20 December 2019;

Published: 21 January 2020.

Edited by:

Iain Sutcliffe, Northumbria University, United KingdomReviewed by:

Alistair K. Brown, Newcastle University, United KingdomChristophe Guilhot, UMR 5089 Institut de Pharmacologie et de Biologie Structurale (IPBS), France

Copyright © 2020 Riggs-Shute, Falkinham and Yang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zhaomin Yang, em15YW5nQHZ0LmVkdQ==

Sarah D. Riggs-Shute

Sarah D. Riggs-Shute Joseph O. Falkinham

Joseph O. Falkinham Zhaomin Yang

Zhaomin Yang